2. Juggling across New Media

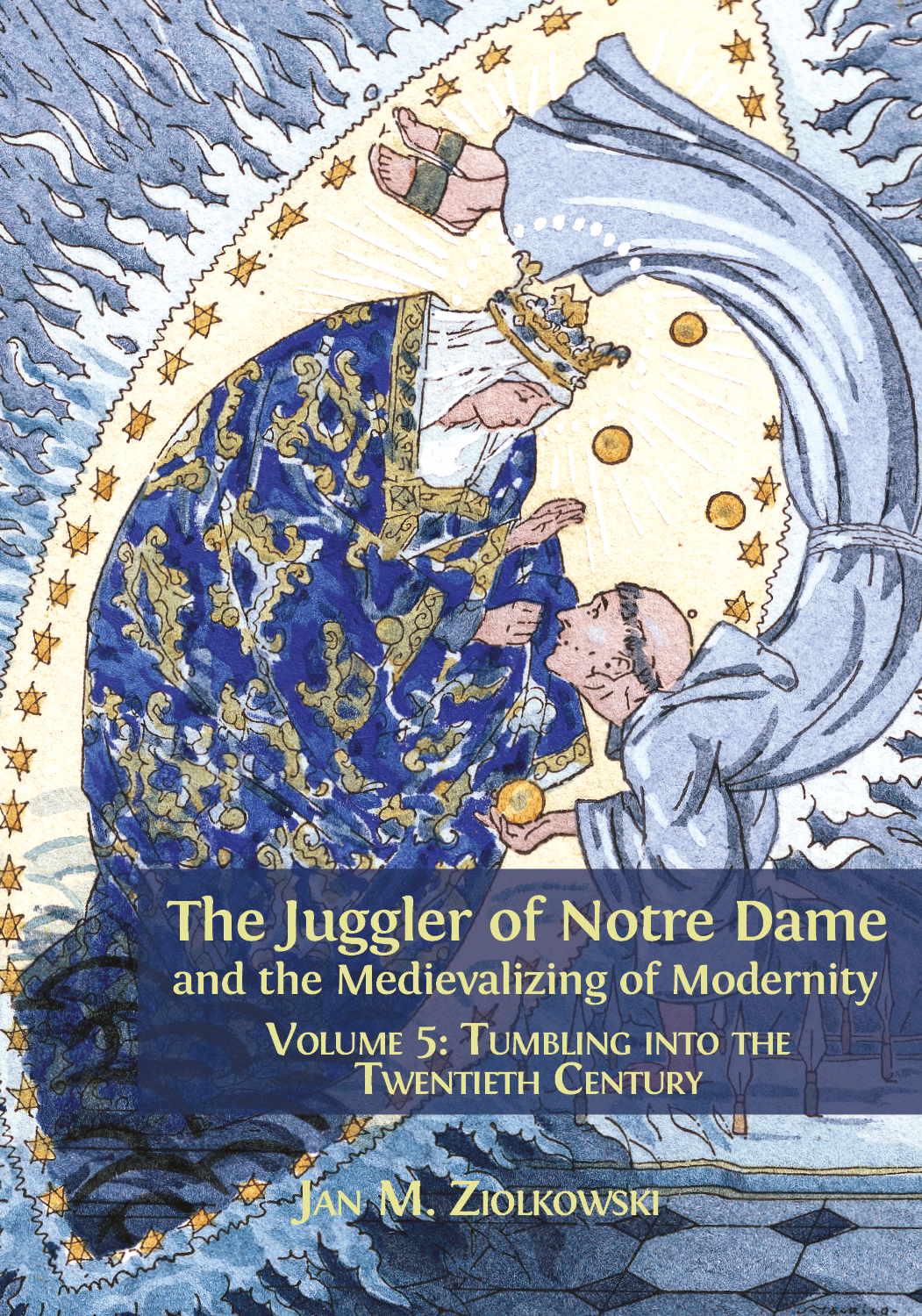

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0148.02

The Middle Ages is regaining its credibility and its seductiveness for our spirits, a Middle Ages released from the notorious darkness that until recently an entire rhetorical and political tradition deepened around its horror.

As media multiplied in the early twentieth century, artistic imperatives and commercial forces coalesced to encourage the repurposing of creation in art from one channel of expression to another. Printed pages morphed into radio plays, while in the opposite direction transmissions through the airwaves transitioned into books and recordings. Opera passed onto high-fidelity cylinders, disks, and tapes. The melodies of Massenet even made their way onto pianolas, player pianos that were equipped to make music automatically by converting into notes on the keyboard perforations in long rolls or folded lengths of stout paper or cardboard. Librettos gained broad circulation in conjunction with radio broadcasts. Then television arrived, marking only the beginning of audiovisual forms that have proliferated at an ever more meteoric rate. In all of these, medieval-themed entertainment has had its place, however unlikely, and the juggler has occupied his own special niche.

Only tangible objects survive, but the breadth and depth of the testimony allow us at least a peep of an intangible cultural heritage, in vanished types of performances—including skits, dances, puppet shows, and artwork. These lost diversions far outnumbered what has been captured in print, preserved on film, pressed on shellac or vinyl, or recorded in other formats. Let us read, see, and hear what enables us to imagine the no longer legible, visible, and audible. In doing so, let us bear in mind that culture is not an unbroken chain of success. It also involves and even requires repeated instances of mediocrity and downright failure. The drearinesses and debacles supply the night soil that sometimes enables better artistry to take root and grow.

Making a Spectacle of Miracle

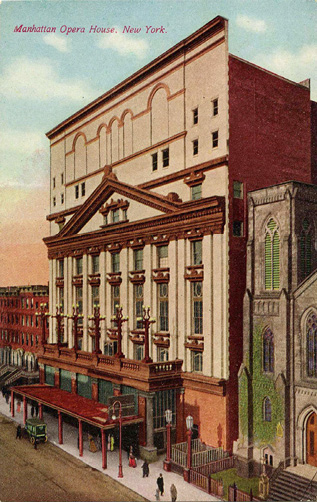

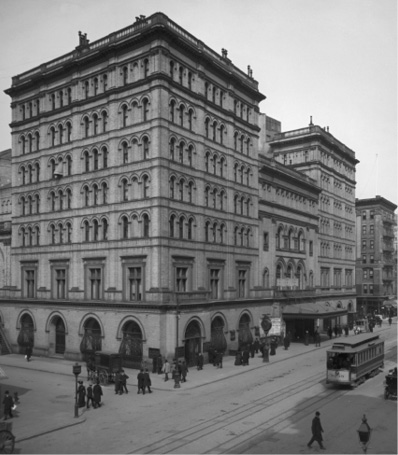

Beyond Mary Garden’s personal talent and blind (but only occasionally blonde) ambition, adept showmanship by Oscar Hammerstein I ensured the triumph of Massenet’s magnum opus in New World productions. From 1906 to 1910, this sharp-elbowed entrepreneur poured resources into his Manhattan Opera Company (see Fig. 2.1). In this context—next door to the Gothic Reform Church—the diva made her début as Jean the jongleur, and here she also created additional roles in sundry other musical dramas for the first time in North America. In a head-to-head, knock-down, fight-to-the-finish competition with the Metropolitan Opera House (see Fig. 2.2), the impresario’s own Manhattan equivalent lunged to the forefront of grand opera in New York City. In 1908, the producer augmented his presence on the Eastern seaboard by building in a second city another theater, the Philadelphia Opera House (see Fig. 2.3).

Fig. 2.1 Postcard of the Manhattan Opera House, New York (early twentieth century).

Fig. 2.2 Metropolitan Opera House, New York. Photograph by Detroit Publishing Co., ca. 1905. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Gift of the State Historical Society of Colorado, 1949.

Fig. 2.3 Postcard of the Metropolitan Opera House, Philadelphia, PA (New York: Union News Company, ca. 1914).

When the curtain fell on the season in the two cities where he had at least wishfully a permanent footprint, the promoter took his troupe on tour to Boston, Pittsburgh, and Chicago. The repertoire of his prima donna for the road trip encompassed Salomé, Pelléas, Thaïs, Louise, and Le jongleur de Notre Dame. The publicist’s expansion of his activities guaranteed that knowledge and appetite for opera exploded outside the elite playhouses of a very few cities in the northeast, while the diva’s shuttling between France and the United States contributed to the process that exalted the art into a truly transatlantic and eventually global form.

During the first decade and a half of the twentieth century Le jongleur de Notre Dame lent itself well to the tastes of theater- and operagoers. Among its assorted advantages, it featured a jongleur as the male lead, and it focused on a miracle—two traits shared by early silent films. At least a couple of these early black-and-white productions give prominence to professional performers. Although Sir Walter Scott had published his Lay of the Last Minstrel in 1805, the final turned out to be only the first, as far as the presence of these itinerants in popular and mass culture is concerned. The earliest specimen in movies without sound would be the French Aloyse and the Minstrel. The story of this 1909 feature centers on the melodrama of relations between the title character, who is a miller’s daughter, and an entertainer. The lovers wed after overcoming the resistance of her parents. Slightly later, the enormously influential 1912 German film Das Mirakel—in English, The Miracle—begins with the seduction of a young nun by Satan in the guise of a bad-boy traveling entertainer.

Examples of lives and passions of Christ and saints are thick on the ground in early motion pictures. Medieval miracles, and among them those of the Virgin, form another large subgroup. Joan of Arc enjoyed an extraordinary vogue, along with Francis of Assisi. Possible explanations are readily forthcoming. The cinemas of the early twentieth century were in one sense modern through and through, while in another these rallying places for collective entertainment called very much to mind the medieval past. In them, the public sat still as images of their idols flickered before their bloodshot eyes, just as churchgoers in the Middle Ages might have gazed at the representations in stained-glass windows when sunshine streamed through the panes, at statues or paintings illumined by the light of sputtering lamps and tapers, or at priests officiating at candlelit altars before laymen.

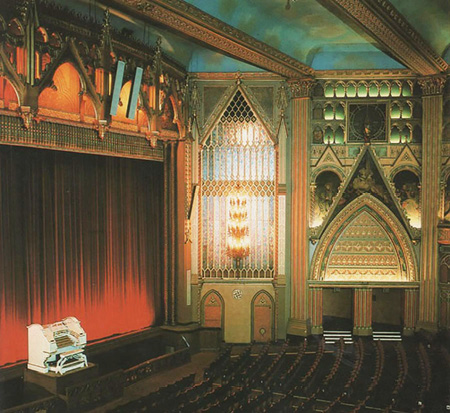

The tally of movie theaters designed and erected in Gothic revival style is not prodigious, but the number constructed suffices to suggest that resemblances between motion pictures and Christian ritual of the Middle Ages did not pass unnoticed. In 1900, not a single purpose-built cinema existed. Within a few decades, communal viewing of films bordered on being a mass religion. At least on occasion, moviegoers referred to their seats as pews, the building manager as a divine functionary, and the stars as gods and goddesses. The experience of moving pictures was delivered in settings that aspired to grandeur almost inconceivable today. The all-embracing objective was avowedly “atmospheric.”

Fig. 2.4 Granada Cinema, Tooting, London. Photograph by John D. Sharp, 1967.

Lavishly appointed playhouses were most often called “movie” or “picture palaces.” They were supersized, to accommodate on average more than two thousand seats. The largest had a capacity of 5,300. In American cities, this form of mass entertainment was a phenomenon of the two decades between 1913 and 1932. A far cry from today’s featureless and indistinctive multiplexes, such palatial constructions were lavishly conceived and constructed as fantasies of Greek and Roman temples and amphitheaters, Italian Renaissance palazzos, Chinese pagodas, Hispano-Moresque palazzos, and Gothic great churches. The film cathedral was a distinct subtype (see Fig. 2.4). Rightly or wrongly, in some quarters of Britain and America the construction of houses of worship in the Middle Ages was seen as an exercise in community-building. The analogy meant that a fantasy church building could accord better with aspirations toward egalitarianism and democracy than anything palatial would have done. Social benefits were felt to derive from the cathedral-like qualities of the most advanced auditorium design. Beyond those advantages, architects planned the interiors to allow for adjusting them to match the content of what was being projected. Accordingly, a religious film could be screened in a theater with lighting features that would transform it into the simulacrum of a basilica or nave. Norman Bel Geddes decorated one building so that it could become a grand Gothic place of prayer. Its aisles served as the footpaths for processions that brought real-life movement into the moving pictures.

Cinemas on both sides of the Atlantic were called “cathedrals of the movies.” The Roxy Theatre in Manhattan went by the name “the cathedral of the motion picture.” Whenever a facility owned by the theater operator Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel opened, the inaugural ceremony followed an elaborate script that enacted a faux liturgy. The event in New York City was no exception, as the proceedings unfolded with a spotlight trained upon a man clad in monastic habit. Reading from a scroll, the pseudobrother intoned a portentous formula, in words that had the old-fashioned and fustian solemnity of liturgical or scriptural English. Think of the King James Bible. The text addressed the edifice itself as the divinity. At the instant when the sham monk enunciated the biblical “Let there be light,” presto! an actual epiphany occurred. Artificial illumination was switched on to accentuate the interior design of the auditorium and the orchestra as it was hoisted out of the pit.

In these early days, many movies qualified as strictly hagiographic narratives with medieval settings. Still more counted as pious legends that related miracles. Not all of them were situated overtly in the Middle Ages, but most of them were steeped in an atmosphere redolent of that era. To an extent, the content of such films matched the medium’s stage of development: the screenplays of motion pictures called for their dramatic action to take place in earlier days because cinema was in its formative phase. Saints’ lives belonged among the prototypical narratives of the Christian West, and it seemed reasonable for the radically new form to seek out stories from the past that marked a similarly fresh departure after the advent of Christianity. Moreover, narrative, and perhaps to an even more conspicuous degree iconography, from those earlier centuries lent itself to the possibilities of celluloid. In these silent black-and-whites, the underlying tales are presented as a succession of scenes or vignettes. One moving picture about holy men and their miracles was described as “implicitly a Golden Legend in animated tableaux.”

In this first wave of movie medievalism, miracles of the Virgin constituted a major subcategory of the options on offer to cinephiles. The stories in these films bobbed loosely in the wake of an 1888 book entitled The Dream. Although not set in the Middle Ages, this novel by Émile Zola plays out under the spell of a great church. The novelist’s reputation might lead us to expect the cool and unexcitable expression of naturalism. Yet the tale represents anything but such clinical detachment and sangfroid. Then again, the writer was filled with paradoxes in his attitudes toward the medieval period.

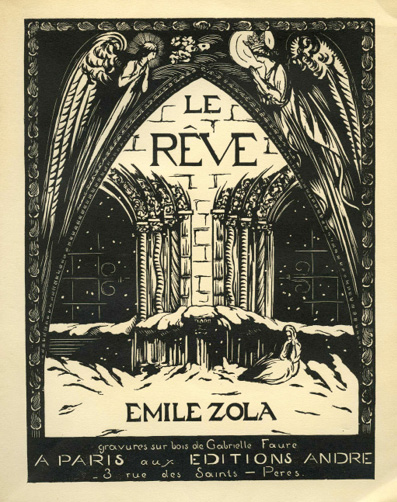

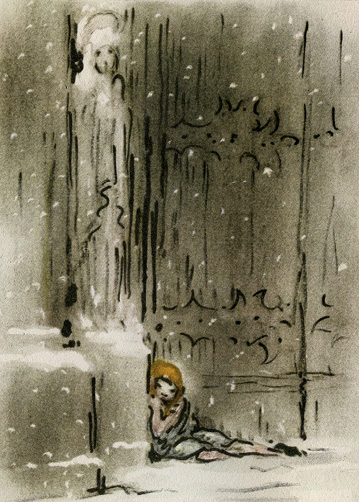

The action happens in an imaginary city. In English, its designation would be “Beautiful Mountain-The Church.” Within this settlement, life pivots on a twelfth-century Romanesque cathedral called the Church of Saint Mary. The story commences on Christmas day at the portal of the towering place of worship. There an orphan, Angélique-Marie Rougon, takes shelter from the driving snow (see Figs. 2.5 and 2.6). The given portion of her full name, identical with that of the leading character in Zola’s novel, could be translated into English literally as “Angelic Mary.” She is taken in as a foundling and adopted by a couple of embroiderers who dwell in a medieval abode connected to the house of prayer. Her adoptive parents produce liturgical paraphernalia for the bishop, using for their craft very much the same toolbox of equipment as their medieval forebears would have done.

Fig. 2.5 Front cover of Émile Zola, Le rêve, illus. Gabrielle Faure (Paris: Éditions André, 1924).

Fig. 2.6 Title page of Émile Zola, Le rêve, illus. Louis Icart (Lausanne, Switzerland: Éditions du Grand-Chêne, 1946).

Angélique divides her days between two activities. Besides her textile handiwork, she learns to read by perusing an edition from 1549 of the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine. Spurred on by the old book, she becomes engrossed in saints’ lives that she finds represented in the gray statuary and colored windows of the cathedral. In a reverie, the young girl discovers that she will marry royalty, but that she will die before achieving happiness. She convinces herself that a figure in a stained glass in the ecclesiastic building depicts her beau-to-be. In turn, she recognizes that the shape in the panes, and therefore her prince charming, is a real-world young man. This debonair Félicien is the son of a priest who joined the Church after losing his wife. Not wishing his offspring to throw caution to the wind and to risk the same kind of loss, the diocesan prevails upon the youth to shun the temptation of wedding and instead enter the priesthood. In her grief at this turn of events, Angélique falls deathly ill. At Félicien’s request, the prelate saves her by kissing her on the brow and uttering a healing prayer. Although she is restored to health and accepts her beloved’s offer of marriage, a “happily ever after” is not to be. As she steps into the place of worship for her nuptials, she hears heavenly voices. This wonder presages her dropping dead on her big day as a bride.

French cinema overflowed with legend. In the filmic flood, The Dream of the Lacemaker, The Legend of the Argentan Lace, and The Legend of the Old Bell-Ringer all received cinematic treatment in black and white as silent films. The first of two about the making of fine fabric is The Dream of the Lacemaker from 1910, which explores a miracle in the life of a maiden who lives alone with the artisan in question, her grandmother. The old woman is prevented by advanced age from embroidering the lace she must supply. The young girl saves both her aging relative and herself through her faith in the Virgin. When granddaughter and her granny together fall asleep, Mary materializes to complete their piecework for them: a stitch in time. The lass takes the finished product to a Gothic castle, which houses a medieval-style court, and where the castellan rewards her richly for her lacy labor. The second movie, The Legend of the Argentan Lace from 1907, was based on an opera printed a year earlier. In this tale, a lace worker crumples from exhaustion after praying in desperation to a Madonna, since the noble lady Anne of Argentan has insisted on collecting overdue lacework she has ordered. The statue becomes animate and tops off the task. Surprise and delight ensue at the court when the craftworker hand-delivers the lace (see Fig. 2.7).

Fig. 2.7 Gaston La Touche, La légende du point d’Argentan, 1884. Oil on canvas, 130 × 162 cm. long. Alençon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et de la Dentelle d’Alençon, France.

The third of the three films was The Legend of the Old Bell-Ringer from 1911. This production revolves around a miraculous intervention, not by the Virgin but instead by an angel who takes the form of a homeless girl. The aged ringer, Gilles, is devoted to his instruments. One day he finds himself unable to wrest a single tone from the carillon. The bailiff tips him off that if he cannot sound his instruments at the devotion known as the Angelus, he will be burned as a heretic. After this word to the wise, the musician saves himself by signing unwittingly on the dotted line of a satanic pact. Fortunately, the waif whom he helped in the morning turns out to be a heaven-sent agent of God who was expedited to test him. Now that he has passed with flying colors, the angelic messenger overmasters the devil and spares the ringer from execution and doom.

Films of legends could unspool the narrative action in a sequence of languid, almost petrified dioramas. Alternatively, another approach could center on movement. These same decades saw the rise of automobiles and airplanes, as well as the growth of other new media such as radio and phonograph. Thus, the period compelled people to acclimate to dynamism, in pictures as in other aspects of life. What killed silent movies was, it goes without saying, not mobility or the lack thereof. After all, they were intrinsically moving. On the contrary, the fatal new development was sound, since silent films by their very nature had none prerecorded within them. The era of such motion pictures ran from the early 1890s until they came into competition with “talkies” in 1929, and subsequently suffered speedy extinction. Their muteness trailed off into everlasting silence.

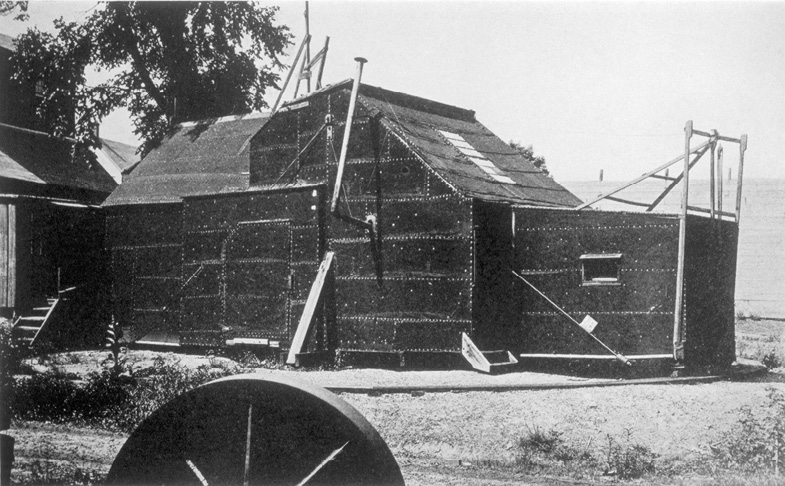

Fig. 2.8 Thomas Edison’s “Black Maria” studio, West Orange, NJ. Photograph, 1894. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Glasshouse Images. All rights reserved.

Early movies had a glancing connection with the Virgin through the designation of the first production studio. Constructed by Thomas Edison in West Orange, New Jersey, in 1893, this cramped place covered in tar paper could be wheeled on a circular turntable. Black and boxlike, it resembled a police van of the kind then nicknamed the Black Maria (see Fig. 2.8). (Why the wagons acquired this designation has provoked much speculation, still up in the air.) The swiveling facility does bear a loose resemblance to a cathedral, with a nave, central tower, and apse—but Edison was no cathedralomaniac. More significant than the fortuitousness of a studio’s name, though, is the repeated adoption of feats performed by the Virgin that we have seen in early film. The ubiquity of Marian miracles both reflected the vitality of more established media, such as short stories and opera, and helped to support it.

Sister Beatrice

To look at one Marian tale that was extraordinarily robust and active in the early years of the century, let us turn to Maurice Maeterlinck (see Fig. 2.9), the Belgian symbolist author writing in French who won the 1911 Nobel Prize in Literature. A decade earlier, he had composed a one-act drama, Sister Beatrice. For its plot, he drew on a miracle recorded most influentially in its early circulation by Caesarius of Heisterbach, in two different versions. The narrative has at its center a wayward nun, a reasonably common type of character in the miracle collections from the Middle Ages. It relates how the Virgin saves this woman from her exceedingly unvirginal deal with the devil.

Fig. 2.9 Maurice Maeterlinck. Photograph by Charles Gerschel, before 1923. New York, New York Public Library Archives.

The earlier of two tellings by the Cistercian monk is a concise one that appears in his Dialogue on Miracles. In it, a sister who serves as doorkeeper or sacristan for her convent runs off with a cleric. Before decamping, she deposits at the feet of the Madonna the keys that have been entrusted to her. After being seduced, the former nun is left in the lurch by the tempter who cost her her chastity, and skids into subsisting as a woman of easy virtue. After ten years in this debased condition, she chances to meander into the vicinity of her former nunnery, and is amazed to hear tell that the nun called Beatrice—and of course that would be herself!—still remains alive. After praying before the effigy in the church, she enters the land of Nod and experiences there a vision. In it, Mary enjoins her to take up once again her responsibilities in the cloister, which the Mother of God herself has fulfilled for her in the intervening decade. Not too long after the rendering in the Dialogue on Miracles, Caesarius expatiated on the story a second time in his Eight Books of Miracles. In this encore, the seducer is a young man and just that, without being specified as a cleric, and Beatrice returns to her onetime community not merely by happenstance but explicitly out of regret. Through investigation of her own, she ascertains that the Virgin has been standing in for her. The story is a harlequin romance in the way the Middle Ages preferred: a lady has a torrid affair, with many ups and downs, that ends happily. Since the setting is medieval, it does not need to be transposed to an earlier historical one to make the grade as a bodice-ripper. The wrinkle is that the earthly love falls by the wayside and the Virgin insinuates herself to ensure spiritual salvation.

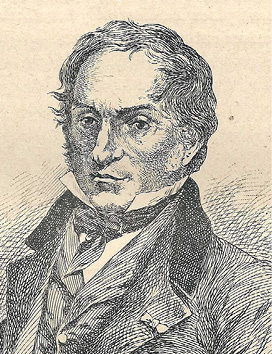

After Caesarius, our evidence proliferates hither and yon. The tale was enormously popular, showing up in texts not only in the half-dead language of Latin but also in many other spoken tongues of Western Europe. In medieval French, the legend of the female sacristan surfaces first in the oldest extant compendium of vernacular miracles, by a twelfth-century Anglo-Norman monk named Adgar. Thereafter, it recurs in both the French Life of the Fathers and Gautier de Coinci’s Miracles of Our Lady. The story undergoes constant alterations, most glaringly in Spanish versions of the early seventeenth century. Afterward, it drops largely out of sight until the early nineteenth century, when its comeback begins. Already in 1837, the same account of the nun Beatrice was adapted and published to considerable acclaim as a short piece of fiction by Charles Nodier, a writer (and philologist, of sorts) who served as a librarian of the Arsenal library from 1824 until his death in 1844. This French author’s medievalizing contributed to that of his close comrade Victor Hugo, especially since Nodier helped to make his place of employment a gathering point for bibliophiles (see Fig. 2.10).

Fig. 2.10 Charles Nodier. Engraving by Abel Jamas, before 1911. Image from Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Nodier-dessin-01.jpg

The English poet Adelaide Anne Procter produced a seemingly sentimentalized account of the traditional story in verse. In 1872, Gottfried Keller brought out in German Seven Legends, scoring the first notable success of his career. The volume agglomerates no fewer than four Marian miracles, in which the Swiss writer struck a realistic and worldly tone that anticipates, loosely, Anatole France’s treatment of Our Lady’s Tumbler. In fact, this German-language author’s secularizing focus on the theme of temptation, especially through sexual attraction, in early Christianity resembles closely some of the later French writer’s interests. Indeed, the episode entitled “The Virgin and the Nun” exhibits analogues to Le jongleur de Notre Dame. Keller tells of a sister named Beatrice (Beatrix in German). After falling in love at first sight, she leaves the convent to marry, and in due course bears an octet of sons to her spouse. Upon returning years afterward to her nunnery, she is open-mouthed to find herself treated as if she had never absented herself. Soon she realizes that in the long interim the image of Mary to whom she had entrusted her keys as sexton had assumed her appearance and fulfilled her duties. Once, all the members of the religious community prepare the finest gifts in their power to present to the Mother of God. Just when the gift-giving is to take place, coincidence has it that Beatrice’s husband and boys chance by the convent. Their arrival leads the religious to reveal the miracle and to give the Virgin eight wreaths of oak leaves that come from her eight children. The acorn doesn’t fall far from the tree.

In Maeterlinck’s hands, the naughty nun in the story is named Megildis. After being appointed as sacristan, she is inveigled by the devil into abandoning her abbey. Her initial seduction takes place through music and dancing youths. She goes so far as to run away with a nice-looking knight—the prototype of the heavy-metal rockstar, except that his weight owes to his armor. Despite these grave gaffes, she is saved by Mary. A Madonna comes to life to assume the habit the once-cloistered woman has discarded and to stand in for her in her absence. In the world, the former sister endures many misadventures involving men, even including conceiving and carrying to term an infant that dies. These misfortunes notwithstanding, she eventually reenters her cloister (see Figs. 2.11 and 2.12). There the Virgin reverts to her original statuesque form, and in the process the dead child is transformed into the sculpted baby Jesus that the sculptural Mother of God cradles in her arms.

Fig. 2.11 Beatrice in the nunnery. Postcard of Maurice Maeterlinck, Sœur Béatrice, produced by Jules Delacre, at the Théâtre du Marais. Photograph by Benjamin Couprie, 1922. Brussels, Archives et Musée de la Littérature. Image courtesy of Archives et Musée de la Littérature. All rights reserved.

Fig. 2.12 Sister Beatrice kneeling in prayer. Postcard of Maurice Maeterlinck, Sœur Béatrice, produced by Jules Delacre, at the Théâtre du Marais. Photograph, 1922. Photographer unknown. Brussels, Archives et Musée de la Littérature. Image courtesy of Archives et Musée de la Littérature. All rights reserved.

In this miracle a jongleur figure plays a harmful role, by sounding music on a pipe that causes Megildis to dance. Gaston Paris had recounted this same wonder, and Anatole France in his review of the professor’s book had recapitulated it in a few words, but Maeterlinck shaped it into something very much his own. Although the narrative antedated the Belgian and in fact had exercised a reenergized impact for nearly half a century, it never garnered as much staying power as it did during the belle époque. Thanks to the rampant triumph of Maeterlinck’s retelling, the tale wandered over a large area across both space and media.

Karl Vollmoeller fleshed out the account into a three-act stage pantomime that became entitled The Miracle. The German playwright and screenwriter was prodded by a sighting of the Virgin that he had while at death’s door during an illness as an eighteen-year-old in 1896. In the element of the Madonna, he was stimulated or even overstimulated by numberless actual images of Mary that he viewed in museums in Italy, France, Germany, and Spain. In addition, he submerged himself in the literary history of the tale and genre. It goes without saying that his conception of the legend was affected by Maeterlinck’s play. Less obviously, Vollmoeller was influenced by medieval versions, in both Latin and vernacular languages. In his handling of the story, the gist remains very much the same. A nun forsakes her convent to heed the calls of the world and of sex, even nymphomania. After a life aquiver with what are presented as being the shameful pleasures of prostitution, she returns as a penitent to redeem herself. At this turning point, she discovers that throughout her long absence the Mother of God has assumed her identity and fulfilled her responsibilities.

Convinced to his very kernel that the legend encapsulated a spiritual message for people of all faiths and incomes, Vollmoeller sought to produce it as a pantomime, and so make it accessible to the broadest possible audiences. Although now and again the staging took place at Easter, the potential for a Noel nexus was self-evident from the date of the first performance. Yuletide remained an attractive season for putting on the show even a decade and a half after its opening. In London, the original enactment premiered formally in the countdown to Christmas of 1911, and from England the spectacle fanned out triumphantly throughout Europe. Long afterward it roved belatedly across the Atlantic to the United States. Plans for a New York iteration to have its initial enactment on December 9, 1914, had to be jettisoned when war broke out in Europe.

A decade later, Norman Bel Geddes erected a sham cathedral half a block long as the set for putting on the pageant in New York City. This make-do church had “forty-two multi-lancet windows, the largest thirty-seven feet high, and a rose window triple the diameter of the ones at Notre-Dame de Paris.” The cultural competition of the United States with the old countries of Europe stood then at its height. In Americanizing the Middle Ages—encompassing of course Gothic, great churches, Marian legends, and much else—the people of the United States, perhaps none more than New Yorkers, operated under the banner of “the bigger, the better.” The San Francisco leg of the traveling show opened on Christmas Eve of 1926. Even fifteen years after the debut, the yuletide connection still held strong.

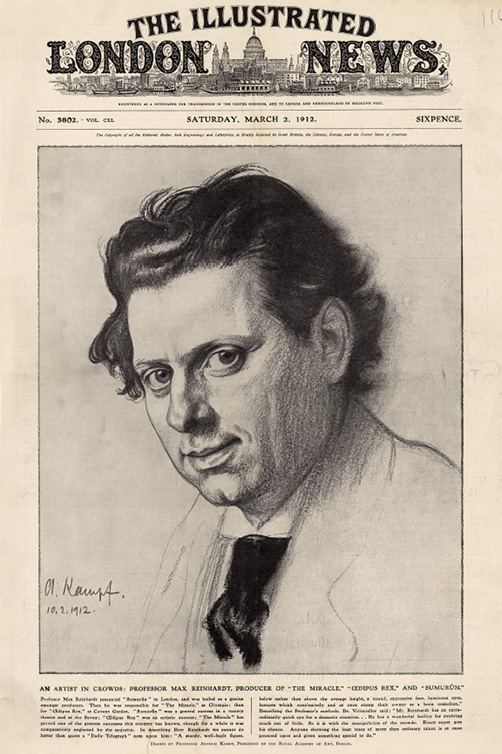

The inaugural London production was directed by Max Reinhardt, who was at this point on a steep ascent in his international trajectory. A city newspaper, highlighting the Austrian-born actor and director on its cover, proclaimed him “an artist in crowds.” Not shying from the pitfalls of hyperbole, the article labeled The Miracle “one of the greatest successes this country has known” (see Fig. 2.13). The presentations organized by Reinhardt were the equivalent of today’s big-budget blockbusters, Brobdingnagian in both their casts and their audiences, with no fewer than 30,000 spectators and participants attending each day. The logistical challenges were commensurately colossal.

Fig. 2.13 Drawing “Professor Max Reinhardt,” by Arthur Kampf, on the front cover of The Illustrated London News 140, no. 3802 (March 2, 1912).

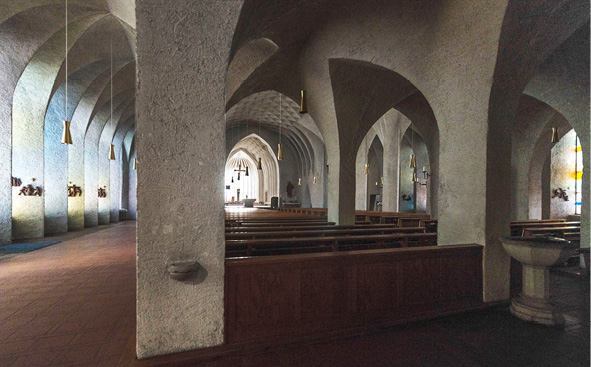

The stagings were also radically innovative, among other things in their deployment of chiaroscuro and other lighting effects in the mise en scène. Such contrasts between gleaming white and jet black typify expressionism as it manifested itself in German architecture, such as the church of Saint John the Baptist in Neu-Ulm. Built between 1922 and 1926, the place of worship was conceived as a memorial to the soldiers who fell in World War I (see Fig. 2.14). Whether his spectacle is classified as expressionist or not, Reinhardt resorted extensively to artificial illumination. For example, he had the light alternate between extremes: on one cue, it would simulate the multihued appearance of sunbeams through stained-glass windows in a Gothic cathedral, while on the next it would take the form of a single stream of brightness trained upon a figure such as the Madonna.

Fig. 2.14 View toward altar in St. John the Baptist Church, Neu-Ulm, Germany. Hans Peter Schaefer (www.reserv-art.de), 2015, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neu-ulm-st_johann_baptist-260815_01.jpg

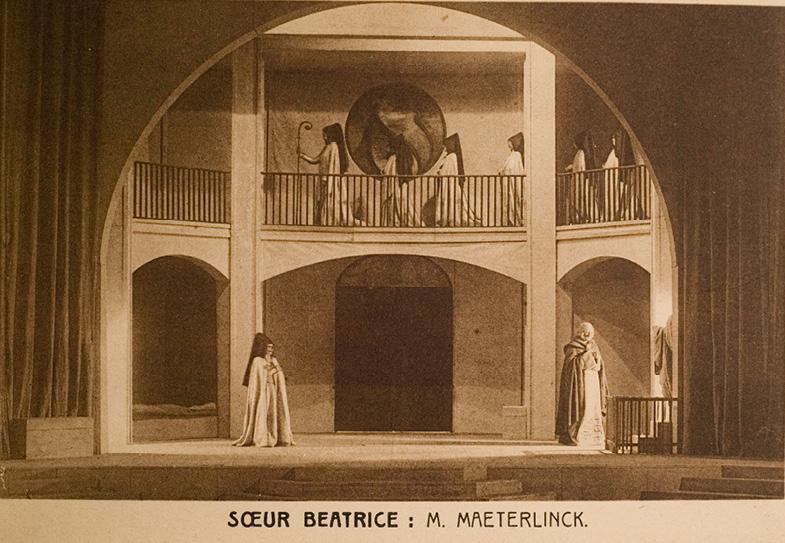

Albeit on a simpler scale, the illumination of the white-clad Cistercian nun appears already to have been a true highlight in a production of Maeterlinck’s Sister Beatrice in prerevolutionary Russia (see Fig. 2.15). A fusion of Wagner and symbolism, this iteration by Vsevolod Meyerhold took advantage of highly innovative techniques in acting and staging. For instance, presumably especially in the portrayal of the Madonna, the director milked for all it was worth the potential of “silhouette,” a technique in which actors remained strictly motionless. He also projected onto the backdrop in Roman and not Cyrillic letters the initials BVM, to signify “Blessed Virgin Mary.”

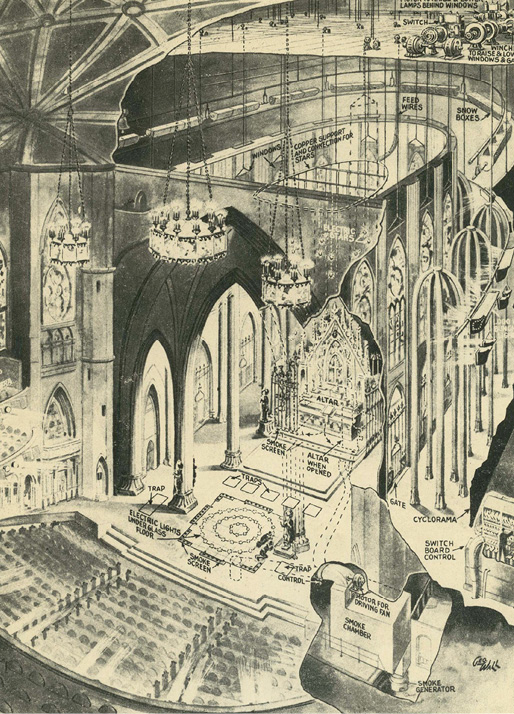

Elsewhere, the elaborate apparatus to support performance of the pantomime can be seen in a plan for the stage engineering that was originally published in the monthly Scientific American. The entire configuration of devices included motors, winches, smokescreens, and a cyclorama. Lighting of course also came into play, with electric illumination under a glass floor and a thousand-watt bunch light (see Fig. 2.16). The results could have borne a remarkable resemblance to what can be surmised about the staging of Le jongleur de Notre Dame. The similarities were breathtakingly strong in one scene of The Miracle, in which Megildis hurled herself atop her dead newborn on the pavers of the cathedral before the likeness of Mary (see Fig. 2.17). In the strobing light that followed, the image came to life, gently smiling, with the Child in her arms. The heart of these episodes remained the key characters of the nun and the Madonna (see Fig. 2.18).

Fig. 2.15 Postcard of Sister Beatrice in a Russian adaptation of Maeterlinck’s Soeur Beatrice (early twentieth century).

Fig. 2.16 Schematics of the Century Theatre’s stage design for The Miracle. Drawing by George Wall, 1924. Published in Scientific American 130 (April 1924), 229.

Fig. 2.17 Set design for the Century Theatre’s production of The Miracle. Drawing by Carl Link, 1924.

Fig. 2.18 Rosamund Botsford as the Nun and Asta Fleming as the Madonna in a production of The Miracle. Photograph, 1914. Photographer unknown.

Before the end of 1912, the spectacle had twice been made into films. Disentangling the two can be gnarly, since they shared variations of the same title, both the German and the English for The Miracle. At the time of release, the existence of two competing variants occasioned a major legal squabble over copyright, and subsequently the continental form circulated under varying titles. In full color, one was intended to be shown within a play that comprehended the projection of the motion picture, the accompaniment of a symphony orchestra and chorus with additional instruments and sound effects, and live actors. The colored cinematic version was screened to thunderous applause in Covent Garden in London a year after the live performance premiered on Christmas Eve of 1911.

Although only one of the silent films is extant, the score by Humperdinck and the stage directions for the pantomime by Vollmoeller and as expanded and adapted by Reinhardt have survived. Since these early cinematic forms would have been projected with the complement of piano playing and choruses, they would have cranked open the sluices for such miracles to migrate into a broader world in conjunction with music. The silver screen did not put an end to live enactments of the spectacle, although enactments did not take place again on the scale of the earliest extravaganzas.

The synchronous medievalism and modernity is evident in a sepia-toned print for the German production of The Miracle (see Fig. 2.19). The design is by Ludwig Hohlwein, who belonged to a movement that means in English “advertising art.” His poster was issued in 1914 for the film version of the play that had been initiated by Max Reinhardt in Olympia Hall, London, but could not be posted owing to the outbreak of the War. Despite these inauspicious circumstances, the picture enjoyed an esteemed afterlife on purely aesthetic grounds for its inherent quality as an artwork.

Fig. 2.19 Advertisement for a German production of The Miracle. Poster by Ludwig Hohlwein, 1914.

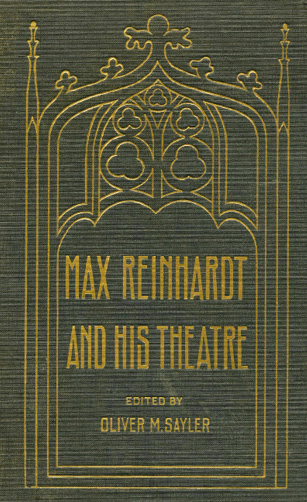

In 1927, the tradition reached its erudite apogee in a substantial tome of scholarship that sets forth systematically all the medieval evidence and each and every supposedly modern attestation for the underlying tale, from the Renaissance and beyond, down to the then-present day. At the same time, such a definitive and learned autopsy in some ways (or do I have it backward?) sounded the death knell for stories about the sacristan. Only a few years earlier, The Miracle had received exhaustive description in a 1924 study. The very cover of this book in English monumentalized the association of Reinhardt’s whole oeuvre with Gothic (see Fig. 2.20).

Fig. 2.20 Front cover of Oliver M. Sayler, ed., Max Reinhardt and His Theatre, trans. Mariele S. Gudernatsch et al. (New York: Brentano’s Publishers, 1924).

Where dance and music are concerned, the pantomime verges on being an anti-jongleur de Notre Dame. Whereas in the tale of the tumbler the balletic is redemptive, in The Miracle both music and dance qualify as damnable forms of expression. Thus the young religious is lured into the secular world especially by professional musicians and dancing children. A villain of the first order through the play is the German equivalent of a minstrel, whose sinister piping animates the nun to caper wildly whenever she hears it. The ripple effects are anything but fun and games. What is more, the dramatic entertainment incorporates motifs familiar from other Marian miracles. Thus, when the central character reverts to her former status, a shower of roses rains down upon her and those of her sisters in attendance.

Maeterlinck’s Sister Beatrice was acted widely by Sarah Bernhardt. Decades later, the singer Yvette Guilbert wrote an operatic version that she had no luck in bringing into production. The Scottish poet and playwright John Davidson put the same story into meter under the title “A Ballad of a Nun.” His piece opens on a note of seemingly impeccable piety. In clunky verse, it describes the protracted solicitude of the nun (see Fig. 2.21). Alas, after a decade of unimpeachable conduct, she slips from the regular devotion of the nunnery into a most irregular life of secular sin. The composition rises to a crescendo in the recognition scene, as the Virgin coaxes the fallen woman into realizing that Mary has assumed her semblance and duties during the whole of her absence (see Fig. 2.22).

Fig. 2.21 Beatrice as a nun. Illustration by Paul Henry, 1905. Published in John Davidson, The Ballad of a Nun (London: John Lane, 1905), 11.

Fig. 2.22 Beatrice kneels before the Virgin. Illustration by Paul Henry, 1905. Published in John Davidson, The Ballad of a Nun (London: John Lane, 1905), 35.

Davidson’s piece of poetry was published in his Ballads and Songs, which in the United States came into print thanks to Copeland & Day, the same Boston-based firm that had brought out Our Lady’s Tumbler in 1898. As this publication may suggest, the Scot’s take on the story was conditioned by the fin-de-siècle attitudes and values of The Yellow Book. It handles the Mother of God with correspondingly less reverence than other versions might lead us to expect.

Later Sister Beatrice became a lyric legend in four acts, which was performed in the opera house of Monte Carlo in March, 1914. The mother of one of the librettists was Léontine Lippmann, who had been the lover and muse of none other than Anatole France. Furthermore, the composer of the music for this musical drama had conducted the world premiere of Massenet’s medieval and medievalesque Grisélidis. The intertwining of relationships between the writers and musicians involved in different expressions of Sister Beatrice, on the one hand, and those who contributed to the tradition of Our Lady’s Tumbler, on the other, was no accident. Rather, it resulted inevitably from the passion for Marian miracles that so many shared during this period.

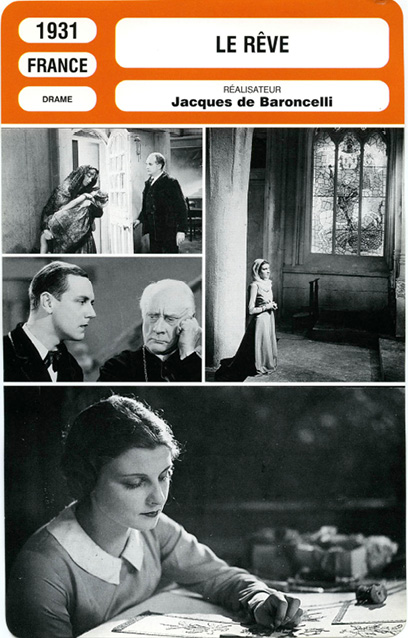

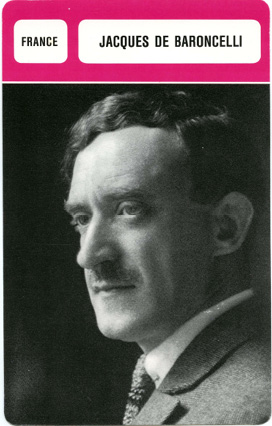

Helped by Charles Nodier’s 1837 story and “a miracle of the thirteenth century,” Maeterlinck himself drafted a script for a 1923 Franco-Belgian motion picture The Legend of Sister Beatrice (see Fig. 2.23). The movie was directed by Jacques de Baroncelli, a Frenchman long resident in Belgium (see Fig. 2.24). Baroncelli’s reputation rested mainly on silent films, although he also ventured a little later into talkies. In an exclusive conducted shortly before the cinematic release, the director displays his grounding in both the preceding literary history and contemporary cultural context of the tale. His ready familiarity with the development of the narrative from the Middle Ages to his own day bears witness to the strength of the axis that still ran between artists and scholars in the early twentieth century.

As Baroncelli deciphers his desire to translate a medieval miracle of the Virgin into images on the modern screen, he trots out an impressive erudition. For example, he adverts casually to similar episodes recounted in vernacular prose, such as those reaped by Adgar. Continuing to display a formidable range, the filmmaker also mentions in passing the thirteenth-century Everard of Gateley, a monk of Bury St. Edmunds who recast three of Adgar’s legends in his own Miracles of the Virgin. The French moviemaker alludes too to a version of the story of Beatrice in Hugh Farsit’s Latin prose from some time after 1143. Beyond Everard and Hugh, Baroncelli touches as well upon another account of the tale about the wayward nun in Old French verse by Gautier de Coinci. Among other texts, he gives special notice to Our Lady’s Tumbler and its reworkings by Anatole France and Jules Massenet. Additionally, he manifests awareness of miniatures found in manuscripts held in the National Library of France. Finally, he was also well apprised of the success that Max Reinhardt had achieved in 1913.

Fig. 2.23 Collector’s movie card for the film adaption of Le rêve, dir. Jacques de Baroncelli (1931).

Fig. 2.24 Collector’s movie card for Jacques de Baroncelli. Photograph, 1920s. Photographer unknown.

Despite the fanfare of book learning, in the end we have a fair right to question how deeply Baroncelli had delved in his readings. While he identifies the French and Latin authors, he limits his comments to their names and no more. In his remarks about both “The Legend of Sister Beatrice” and Our Lady’s Tumbler, he exposes himself as utterly dependent on the short and sweet sketches that he quotes from a literary history by Gustave Lanson. From this work the director would have derived views of the content that were thoroughly typical of the day. Thus Lanson brackets his résumés between two general observations: the first draws attention to the stories’ naïveté, and the concluding one sounds gently ironic and condescending. None of this is the stuff of great erudition.

About “The Legend of Sister Beatrice” Baroncelli digressed revealingly about attitudes, his own and his era’s, toward such material:

In the end, perhaps without wanting to do so, I have yielded to a vogue. The Middle Ages is regaining its credibility and its seductiveness for our spirits, a Middle Ages released from the notorious darkness that until recently an entire rhetorical and political tradition deepened around its horror. I think less of Robin Hood than of our present-day literature. What our scholars sorted out, brought to light already for a long time, our young writers finally have discovered and are carried away by the thrill of showing to the public. In reality, they reinvigorate juicy old legends of France which after having lulled from one era into another “evenings of thatched cottages and castles,” still charm the evenings of refined people with their fiction and their old, learnedly naïve and gilded language.

He continues:

So that [the legend] may recover in the eyes of our contemporaries all its innate, deep value, I have believed myself obliged to make play, in the light of windows and the shadow of worship, reflections of the brilliant and brutal life of the Middle Ages.

What he craves from medieval culture turns out to be a unity that by implication is wanting in his own day. Henry Adams had reacted similarly.

Like many contemporaries on both coasts of the Atlantic, Baroncelli applauded an organic integrity and holism in the Middle Ages that technological, social, and religious transformations had banished from modernity—or at least many moderns and modernists professed to believe so. Ironically, he delivered himself of this opinion just as the revival of medieval legends and miracles wilted in the face of modernism and other forces. One reviewer rewarded him by describing him not merely as a medieval artisan, as a painter of stained glass and a manuscript illuminator, but even as a mystic who ventured into a cosmos that surpassed the ordinary senses. Little did either the filmmaker or the critic realize that these long-ago centuries would soon enough incur the risk of being a lost world, for not everyone wanted or appreciated the transcendence it offered.

Sister Angelica

Provocatively similar to the tale of Beatrice is Sister Angelica by the Italian composer Giacomo Puccini, which premiered in New York City in 1918 (see Fig. 2.25). Set in a convent near Siena in the latter part of the seventeenth century, the opera culminates in the suicide of a cloistered woman within the nunnery’s precincts, and it concludes with the miracle of a heavenly vision that the conventual apprehends as she gives up the ghost. In the apparition Mary appears, along with Angelica’s illegitimate son, who the nun realized only a little earlier had died of a fever. To join this child in death, she has perpetrated the mortal sin of swilling a draft of poisonous herbs she has concocted. Despite the infractions that have brought her to this dire pass, the Mother of God grants the compromised contemplative pardon.

Fig. 2.25 Front cover of Giacomo Puccini, Suor Angelica (Milan, Italy: G. Ricordi, 1918).

By a kind of thematic symmetry, Puccini’s musical drama also resembles, and is indebted to, Massenet’s Le jongleur de Notre Dame. The difference between the two compositions may be reduced to the particulars of transgressions. Marian miracles have at their heart, in two senses, missteps that the Virgin rectifies so that sinners may be redeemed. Whereas the lead characters in the other stories we have discussed establish their sinfulness through their (mis)deeds or dispositions, the medieval performer in this one seems to have committed violations mainly through his choice of employment. Whereas the entertainer saves himself by applying for the Madonna the same skills that apparently put him in need of salvation in the first place, the disobedient brides of Christ cannot do the same on behalf of Mary.

Puccini weighed the possibility of composing music for a gaggle of dramatic works set in the Middle Ages or early Renaissance. Among his inspirations and options, one would have been the text by Maeterlinck for the 1909 lyric drama or opera Monna Vanna by the French musician Henry Février. The Belgian playwright situated this piece at the end of the fifteenth century. Another candidate would have been the libretto for Puccini’s own Margherita da Cortona, composed between 1904 and 1906. The title character under consideration was a thirteenth-century Italian religious in the Franciscan order, the Third Order of Saint Francis. At this stage, the musician was also so marinated in Victor Hugo that he contemplated creating his own Notre-Dame de Paris. He may have been forestalled from doing so when Massenet’s opera premiered, with its confusingly similar title.

Just as the story of the jongleur is set in a monastery with an all-male cast, so too that of Sister Angelica takes place in a convent with only women. The cloistral atmosphere in both operas challenges their composers and librettists to achieve drama within strict confines. Both the nun and the minstrel enter religious institutions at least partly as a means of performing penance and achieving redemption. In the end they receive celestial absolution for their past misdemeanors.

The climactic scene of Puccini’s Sister Angelica has seen radical inconsistency in its staging. Directors of opera companies have been racked by doubts about who does what in the final throes. With machine-gun-like anaphora, the female principal calls upon the Madonna a full half dozen times in the distraught speech that precedes the sounds of angelic intercession for her with the Blessed Virgin. At the very end Puccini’s stage directions call for veritable pyrotechnics of lighting. The chapel, swollen with light, evolves into a mystical blast of illumination, highlighting not Mary’s image but the Mother of God herself, all in white with a fair-haired child before her. As audience members, we are presumably bedazzled visually, while experiencing aurally the Marian hymn that the chorus of angels intones.

Audio Recording

The medium is the message.

Both within and even outside the Anglophone and Francophone worlds, the tale of Our Lady’s Tumbler soaked down the ridges of literature into the grooves of other media through which it might reach a broader public. The modes in which it and other narratives could be presented and preserved mushroomed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Books with the medieval narrative and Anatole France’s short story multiplied, not just in French but in other languages too. Playbills, together with other less ephemeral materials for the opera such as printed scores and librettos, helped to disseminate the jongleur in ever more expansive circles. Above all, performances of Massenet’s musical drama helped to spread the word, along with the images and sounds that it delivered.

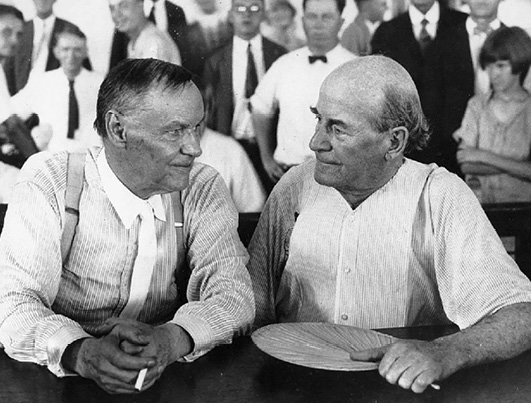

The degree to which the story suffused US culture can be extracted from, of all things, an obituary—and one that could not differ more radically from the gentle niceness of the medieval poem. The death notice marked the passing on July 26, 1925, of William Jennings Bryan, a long-prominent American politician who had served as Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson, and had run three unavailing campaigns as the Democratic candidate for US President. More to the point than the breath he wasted on the hustings, as an attorney for the anti-Darwinist camp he had dished out ugly talk, bursting with ignorance and intolerance, in the famous “monkey trial” of John T. Scopes which had taken place earlier in 1925 (see Fig. 2.26).

Fig. 2.26 Clarence Darrow (left) and William Jennings Bryan (right) at the Scopes Monkey Trial, Dayton, TN. Photograph, 1925. Photographer unknown.

Longstanding custom bids that we “speak no ill of the dead,” a principle accorded even more gravitas in the Latin formulation de mortuis nil nisi bonum. In out-and-out contravention of this sacrosanct injunction, a journalist published on the day following Bryan’s demise an acidic “In Memoriam: W. J. B.” The relevant passage reads:

The best verdict the most romantic editorial writer could dredge up, save in the humorless South, was to the general effect that his imbecilities were excused by his earnestness—that under his clowning, as under that of the juggler of Notre Dame, there was the zeal of a steadfast soul. But this was apology, not praise…

This savage indictment of the antievolutionist came from the sharp-tipped pen of none other than H. L. Mencken. Often known as the “Sage of Baltimore,” this writer clambered to the pinnacle of his career as a newspaperman when he covered the Scopes case (see Fig. 2.27). In the curmudgeonly passage quoted, he compared the newly deceased Bryan caustically to the juggler, claiming that the sole virtue ascribed to his dead antagonist was psychic sincerity—and yet he argued that under interrogation, the seeming genuineness turns out not to merit that name.

Fig. 2.27 H. L. Mencken. Photograph by Ben Pinchot, before 1928. Image from Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:H-L-Mencken-1928.jpg

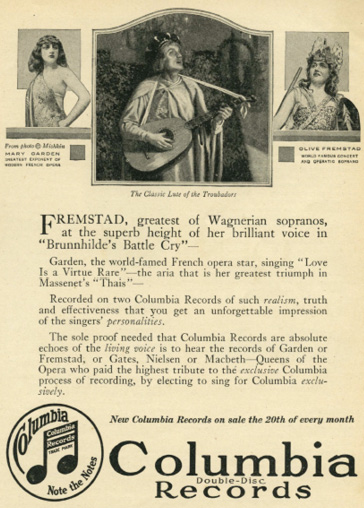

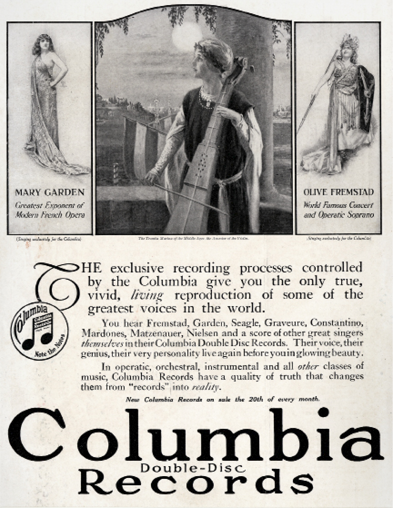

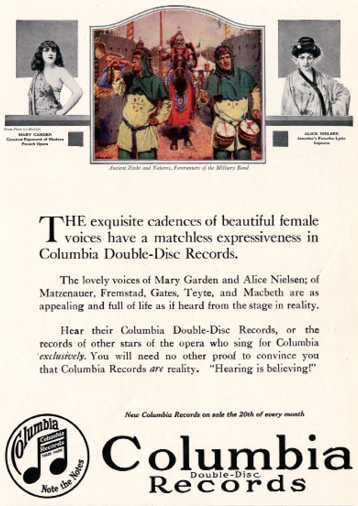

The story of the story from World War I and later can be sliced into stages determined by themes with which the juggler became associated. Thus he can be interpreted profitably as a character connected with Christianity and Christmas, an underdog to inspire children or the politically downtrodden, and an avatar of the artist or poet. At the same time, the narrative also tells a tale of new vehicles, for instance as opera first gains ground and then yields it to such forms as audio recording, radio, television, cartoon, animated short, and feature-length film. Recordings were made even before the musical drama opened in Paris, though after it premiered in Monte Carlo. The cylinders and disks on which the voices of singers attained preservation for posterity belonged integrally to the selling of the late antique and medieval periods to mass markets, as the medium was ballyhooed for the verisimilitude that allowed access to not just the voices but even the personalities of divas such as Mary Garden. The full centrality of the Middle Ages within this marketing effort can be seen in a promotional campaign for Columbia Records. The dog-and-pony show used to pitch this approach can be easily imagined. In printed advertisements, medieval performers of diverse sorts are flanked by two stars of the operatic stage. To the right, Olive Fremstad is posed as Wagner’s Brünnhilde. To the left, Mary Garden stands costumed as Massenet’s Thaïs, in her guise as “greatest exponent of modern French opera.” They are juxtaposed in one case to a troubadour who strums a lute in hand (see Fig. 2.28), in another to a maiden bowing an “ancestor of the violin” (see Fig. 2.29). In another, Mary Garden appears in the same position, but with Alice Nielsen to the right. Between them parade forerunners of a military band (see Fig. 2.30). Purely by luck of the draw, the role chosen to spotlight the prima donna in this publicity was not that of the consummately French Jean the Jongleur. By co-opting a man’s role, she positioned herself to peddle the Middle Ages—or at least the operatic fantasy of that era.

Fig. 2.28 Advertisement for Columbia Records featuring Mary Garden and Olive Fremstad, 1916. Published in Outing 69, no. 1 (October 1916): 123.

Fig. 2.29 Advertisement for Columbia Records featuring Mary Garden and Olive Fremstad, 1916. Published in Hearst’s (June 1916): 1.

Fig. 2.30 Advertisement for Columbia Records featuring Mary Garden and Olive Fremstad, 1916. Published in Country Life in America (October 1916): 79.

Silent Film

Like the cathedral, the motion picture gave people what was missing from their daily lives: religion, solace, art, and most importantly, a feeling of importance.

In 1917, the story of the tumbler may have made the passage into cinema, as a silent film in Germany. At this point, the national movie industry was prospering there, since the war brought to a screeching halt the importation of most foreign cinema that could have competed with domestic production. Yet our ability to appreciate the burgeoning activity is hamstrung by the paucity of surviving evidence: nine tenths of German movies filmed before soundtracks are estimated to have perished. Against the backdrop of such heavy losses, nothing sinister is to be deduced from the frustrating fact that apparently no canister containing Our Lady’s Tumbler or Le jongleur de Notre Dame performed in any language has survived.

What can we infer about the lost black-and-white? The evidence of the 1921 play by Franz Johannes Weinrich might bias us to suspect a kinship between the motion picture and the expressionist German text. Yet an account in a paper intimates that the movie may have been less complexly religious. In the first place, the very name of the cinematic outfit is a word to the wise that it was devoted literally to hagiography: it was called Legend Film Company. To be more specific, a newspaper squib confirms that the film, with a title that could be translated as The Jongleur of Our Dear Lady, was shown as the second in a double feature with The Life of Saint Elizabeth. In Munich, the picture about the entertainer was screened at the invitation of the archbishop, and the producers enjoyed the backing of church authorities. In any case, the evidence may be too paltry ever to determine for certain whether the reel recounted the tale of Le jongleur de Notre Dame, or whether instead it dealt with a version of the Saint Kümmernis miracle, in which a statue rewards a fiddler with a golden shoe or coin.

Explicating the reasons why a given motif in literature, music, or art was devised, and teasing apart the fragile tissues of meanings in its varied expressions, can be infinitely effortful tasks by themselves. Figuring out why artworks on the same theme never managed to be created would be mission impossible: the variables are too many. Why did the fleet-footed juggler apparently never make the jog to the studios of France, Britain, or Tinseltown? The salience of the Madonna may have been too Catholic for Protestants, but that leaves us with the mystery of the jongleur’s failure to fit within French motion-picture mystique. If the story was not long enough, why did it meet the threshold in Germany, or why were other brief fictions made into movies in all these lands? In one case, we have, if only secondhand, a filmmaker’s rationale for not pursuing the topic. His identity and prominence may come as a surprise.

Charlie Chaplin: Tramp Meets Tumbler

If attacked by a mob of clowns, go for the juggler.

Perhaps the most startling revelation to demonstrate how thoroughly the gist of the medieval French poem had permeated broader culture involves Charlie Chaplin. In 1933 or thereabouts, Alistair Cooke, the British-American journalist and broadcaster, was on very chummy terms with the star of comedy. According to Cooke, the world-famous English actor and director was on the prowl for a topic that would lend itself to being made into a short to be screened before the main feature—one of his own films (see Fig. 2.31). After a friend told him about the medieval legend, the comedian poured himself for one evening into roughing out (and acting out) the script for a mime play based on it.

Fig. 2.31 Charlie Chaplin, Paulette Goddard, Alistair Cooke, and Ruth Emerson Cooke (left to right). Photograph, 1934. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Getty Images. All rights reserved.

From memory, Cooke gave two descriptions of the sketch, nearly forty years apart. In the earlier, he related in 1939 that the sketch told

of a mediaeval tumbler who, on his way to the next village, rests in the shadows of a nunnery. He is awed by the sight of a nun counting her beads. The Mother Superior catches him and he is thrown into a cell. At night he escapes into the chapel and in gratitude falls on his knee before the Virgin’s image. He is ashamed to offer his ignorant prayers. So he decides to present, for the Virgin, the best show of his talent. He throws himself over and over. Wet and panting from going through all of his tricks, he finally attempts the best and hardest tumble known to his time. He breaks his back and dies. And the Virgin comes down and blesses him in his death trance.

The journalist comments on the entertainer’s special aptitude—a gift from heaven?—for portraying the acrobat. Before becoming a silent film star, Chaplin had performed as a clown, acrobat, aerialist, and skater. Cooke sums up:

He mimed a whole scene of wonder at the ritual serenity not of this world, the half-comic realization that he was ignorant, the slow self-questioning, then the quick flicker of ambition to show the only skill he knew. He was, for positively one evening only, every shape and name of humility.

In the report he printed in 1977, Cooke includes specification of “the stumbling prayers, the shamed interval, the half-comic realisation that his acrobatics could be enough of a tribute.”

No way exists to discern who should take the blame for the distortions of the story as it is related in the later account, Charlie Chaplin himself or Alistair Cooke. Amendments appear right and left in the narrative that the memoirist unfolds more than four decades after the fact. The tumbler of the medieval poem metamorphoses into the starveling of Anatole France’s version, the monastery morphs into a nunnery, and the athlete’s collapse from exhaustion mutates into death by a broken back. Having a few lines to describe the project is tantalizing, but better than nothing; and nothing else remains, since lamentably for us, the comedian dropped the undertaking. He never recorded his version of the story.

Later, when Cooke inquired about the superstar’s reasons for passing up the opportunity to film the short, the actor referred to his public of admirers. He replied, “They don’t pay their shillings and quarters to see Charles Chaplin doing artistic experiments. They come to see him.” This tart rejoinder might suggest that, despite the obvious reasons for which the pathos of Our Lady’s Tumbler would have lent itself well to this particular celebrity’s knockabout comedy and mimetic skills, the heart of the legend would not have resonated personally with him: the virtue it extolled lay far from his own character. But the real thrust of the retort comes in the monosyllabic pronoun, him. His fans, he insists, plunk down their coins to enter movie theaters because of their attachment to the deadpan persona he adopted in many of his most popular hits, the phlegmatic tramp.

Charlie Chaplin in character was not a monastic juggler who strips down from his cowl to his underclothing. Rather, the pasty-faced tramp was a clown-like vagabond sporting a derby hat over his distinctive tousled black hair, knotted suspenders, droopy and baggy pants, and cracked boots. How are we to react to the jongleur, melancholic but blank-faced as he is? Are we to roister in stitches at his antics, as at those of the hobo played by Chaplin? Are we to imitate him? And are laughter and emulation compatible, slapstick and sanctity, as they were with Saint Francis? A commonality between the two, the tumbler and the tramp, lies in the defining characteristics of the sad-faced clown. One stereotypical manifestation of this role is the figure known as woebegone Pierrot in commedia dell’arte, where his origins are usually traced. Naïve and unworldly, he fails in all his struggles, perhaps particularly in seeking to win the woman he adores. The exact chemistry between humor and hopelessness, or for that matter homelessness, can be elusive. The down-and-out character who shambles about in the silent films, like the long-faced and heart-rending buffoon, is disconsolate. Yet from his low emotional state he wrings comedy, at least in the eyes of his beholders. Furthermore, his personal heavyheartedness speaks to a much larger social and economic sag that engulfed millions upon millions of others from 1929 on: his one-man depression is a tiny cog within the gargantuan machinery of the Great Depression, when going-out-of-business signs gave way to mass unemployment and starvation.

In the Middle Ages, comedy was often defined not as a matter of cackling but instead as a rise from low to high estate, whereas tragedy limned an equal and opposite arc from high to low. From one vantage point, the ending of Our Lady’s Tumbler could be construed as tragic: the protagonist passes his expiration date. Neither the first collapse before the Madonna nor the definitive one later qualifies as a comedic pratfall. The acrobat is not a fool on stage in a comic theater. From another perspective, true closure to the dramatic events comes in a development that is truly uplifting, in that the dead man’s soul is borne aloft to heaven after the Virgin intercedes to deny Satan the power to hustle him off to hell.

Chaplin’s attraction to the tumbler, along with the tale’s progression into various new channels, testifies to the public and commercial interest that was being shown in Our Lady’s Tumbler as well as in its adaptations by Anatole France and Jules Massenet. In one sense, the story’s diffusion across media helped to position it not just for survival but even for success. At the same time, our tale may have begun to look to some too familiar and flavorless, washed out and characterless, even uncreative and trite. Two antithetical processes had been set in motion, and decades more may have to whiz by before we may conclude convincingly which of them has gained the upper hand conclusively.