5. Children’s Juggler and Child Juggler

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0148.05

Suitable for Children

I kid you not: the question has been posed recently, by a person aware of only a few versions of our narrative, whether Le jongleur de Notre Dame can be adapted or not to be fit for a child. The adult answer must be a resounding and unqualified yes. Anatole France’s tale is not intended for a pre-pubescent readership, but it is predicated on an assumption that medieval people such as the juggler were childlike and simple. The limpidity of its style made it accessible, even if not transparent, to young or at least youngish consumers of fiction. Furthermore, its author did write children’s literature, as well as literature stocked with reminiscences of his own childhood. The story’s appropriateness for budding adults has been verified time and again for a century or so, as a text to be acted out in schools, a point of departure for reading aloud from a textbook or children’s book, an opportunity for storytelling from no written script at all, an animated cartoon or claymation animation, a text to be metabolized by youths reading on their own, and on and on. Let me count the ways.

Already in 1928, the leader of a famous private school in the United States folded the tale into a “play book” of productions by the schoolchildren. In preliminary remarks, the editors touched swiftly upon all three main expressions of the narrative, to the advantage of the thirteenth-century poem. In the view of these elitists, Anatole France’s story and Massenet’s opera had coarsened Our Lady’s Tumbler by making it “all too widely known.” In the process, they “falsified the spirit of the legend.” By this reckoning, the model of the account in the original was far above average.

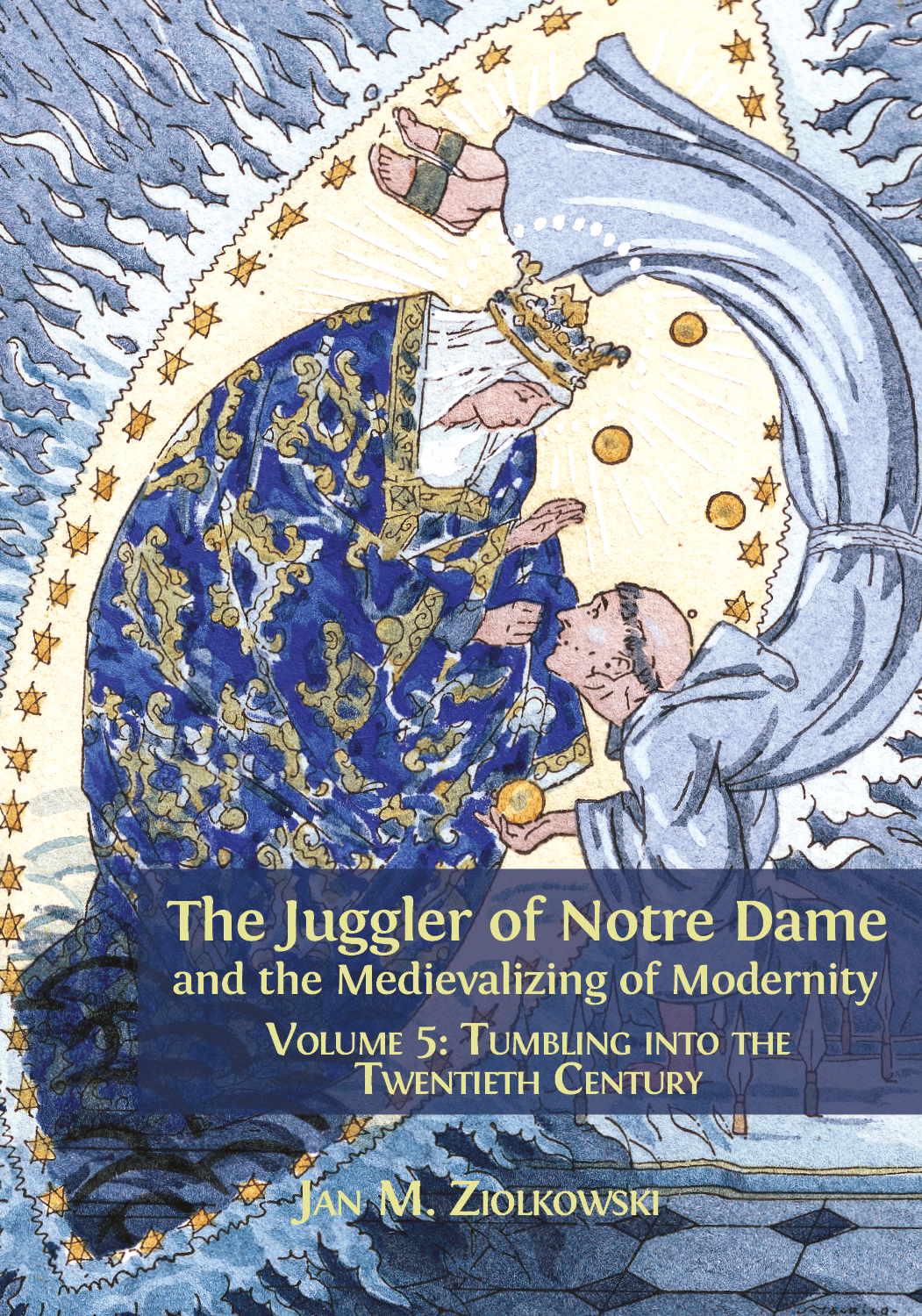

In the introduction, the playwrights offered detailed instructions on a stage set that accentuated Romanesque architecture. Even so, the first illustration in the English script was all pointed arches, with uncongenially and unpromisingly dark alcoves for school-age scribes that give the setting a decidedly scholastic aura (see Fig. 5.1).

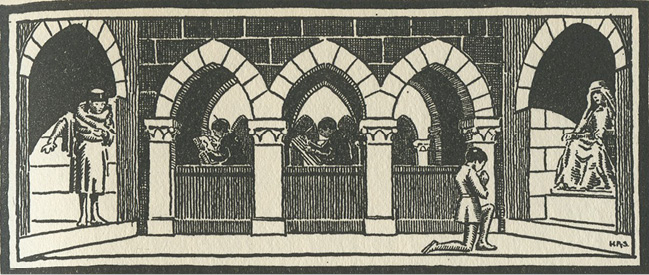

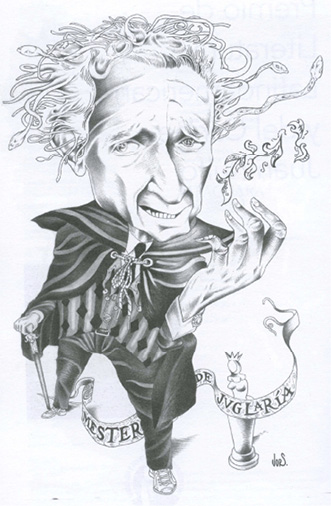

Gothic, with its evocations of beauty, spirituality, and agedness, has long been purveyed to the young in Europe and America. Viollet-le-Duc devoted much of his lifetime to safeguarding France’s heritage in this architectural style, by heading government-funded commissions. Yet he made the effort to compose a heavily illustrated novelized history, published in 1878, of a cathedral in the unreal town of Clusy (see Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.1 The young juggler kneels with bowed head and hands clasped to pray before the Madonna. Illustration by Harold R. Shurtleff, 1928. Published in Katherine Taylor and Henry Copley Greene, The Shady Hill Play Book (New York: MacMillan, 1928), 99.

Fig. 5.2 Front cover of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Histoire d’un hôtel de ville et d’une cathédrale (Paris: J. Hetzel, 1878).

He realized that reaching a grand publique that encompassed the next generation, especially teenagers, would be the surest step for preservation—and for furtherance of his reactionary politics, since in this particular publication he framed the ruination of monuments from the Middle Ages in Paris as owing to the Revolution and Commune. Far more recently and less politically, David Macaulay reprised his great French predecessor nearly a century later by publishing in 1973 as his first book Cathedral: The Story of Its Construction, on the imaginary great church in the equally made-up place of Chutreaux.

The text proper of the piece of theater from the Shady Hill School is adapted from the medieval miracle as transposed into English by Alice Kemp-Welch, by converting indirect into direct discourse. The translation is also put into modernized French, likewise for performance by the pupils. Both versions were to have musical accompaniment, in simple Latin plainsong. The objective of the volume is much less to guide simple schoolwork and even less rote work than to attain synchronism of education, edification, and entertainment.

Nowadays, children in many parts of America and Europe may encounter the Middle Ages most often through white knights, damsels in distress, witches and warlocks in long mantles, and other stock characters from romance as refracted through the peculiar prism of the “once upon a time” in Walt Disney products. King Arthur rules the day. In this lingering context, Camelot, not the monastery, holds sway. This is to say nothing of the sometimes medievalesque universes that J. R. R. Tolkien or J. K. Rowling have opened up. Still, much of the medieval world as it was once constituted has been jettisoned. In secularized nation-states and regions where Christianity generally, and Catholicism particularly, occupy less of the foreground in daily life than they did a century or more ago, many fewer early readers meet the saints, monks, and hermits who were familiar, through the Golden Legend, even to the extent of being jejune in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. All the same, the juggler has held his own in far more than a toned-down way. Although neither the thirteenth-century verses of the tumbler nor Anatole France’s story of the jongleur was designed to be children’s literature, in practice either of them could be digested by a mature young person. The French author’s could be perused by an even more precocious reader, and moreover lends itself more easily to a high density of illustration, because it relates a similar narrative in a much shorter compass. Accordingly, Le jongleur de Notre Dame has repeatedly become an illustrated book for both adults and children. Our Lady’s Tumbler has been embellished, but not as thoroughgoingly. Both have been reshaped often to serve as picture storybooks.

France’s iteration of the tale is altogether plausibly incorporated into a much-favored group of Spanish prose selections that Juan José Arreola compiled for reading aloud. With a gusto for verbiage and fantasy alike, this major author of the literary scene in Mexico came to be esteemed himself as a juggler of language who merged play and skill in his use of words. A thumbnail biography of this writer even has by way of exordium a caricature subtitled “master of minstrelsy,” by the Mexican artist and cartoonist Jorge Salazar (see Fig. 5.3). Arreola first brought out his collection in 1968, following a trouble-free principle of selection by marshaling the stories he had loved as a child. The anthology embraces works by many literary figures, down for example to such fin-de-siècle greats as Oscar Wilde and Marcel Schwob, whom we have met already. The inclusion of the juggler narrative in Arreola’s compendium simultaneously testified to the lingering vitality of Anatole France’s pièce de résistance in his Mexico and contributed to its continued well-being in Spanish and Latin American mass culture. In the same year of 1968, a Spanish novelist and author of children’s literature, at the time a long-term resident in Mexico, compiled a treasury of tales for audiences of tender age. He pegged The Juggler of Our Lady at number 15 among his top 100.

Fig. 5.3 “Mester de Juglaría.” Caricature of Juan José Arreola by Jorge Salazar, 1988–1989.

With tinkering, both Our Lady’s Tumbler and Le jongleur de Notre Dame could be, and have been, turned into bedtime stories. A cut above a lullaby, their heroes are simple, their narrative lines are clean, and simplicity reigns supreme. Equally important, the jongleur’s simpleheartedness is equated almost instinctively with that of juvenile readers. Accordingly, his devotion was seen to be childlike. Well before any author acted on the capacity of the tale to become the stuff of children’s literature, the publishers who engaged with Our Lady’s Tumbler homed in on charm, simplicity, and diminutiveness as its distinguishing qualities. Its petite size made the match with childhood all the smoother. From small chef d’oeuvre to masterpiece for the small was not a long step … it was only a small one.

In 1931, Countess Anna de Noailles (see Fig. 5.4) was asked by Sacha Guitry, an actor and director of both the French stage and motion-picture industry (see Fig. 5.5), to copy out four lines of her poetry for him. The noblewoman, a Francophone writer from Romania, replied by claiming to have forgotten which verses he wanted. Instead, she sent a photograph of herself as a little girl, with the explanation, “Like the Tumbler of our Lady, I want to give you something. I am sending you that which in us is most simple and persistent—childhood.” For both the aristocrat and the filmmaker, it made perfect sense to inscribe the performer in allusive shorthand. After all, the two of them had attended the salon hosted by Madame Arman de Caillavet, mistress of Anatole France, and would have been well versed in his literary corpus, including of course his jongleur.

Fig. 5.4 Anna de Noailles. Photograph, 1921. Photographer unknown.

Fig. 5.5 Sacha Guitry. Photograph, 1930s. Photographer unknown.

Long before World War II, the story wriggled down the road from high society and snaked very naturally in many other directions. For instance, it slithered into anthologies of Christmas fiction for children. Thus it took its place among the narrative inventory in a small and slight, cheerlessly bound booklet of such fare for Sunday school that was published in 1934 and reprinted in England even once hostilities ended. An article that appeared a year after the initial publication stresses the tale’s utility and appeal to both girls and boys—although varyingly along gender lines—in kindergarten and elementary school.

Despite the evidence that the narrative was adopted in curricula for public, private, and Sunday schools, no one should be misled into inferring that it was kept alive mainly in formal education, or that it oozed into this milieu only in the 1930s. In fact, the account of the jongleur’s miracle had been absorbed into books for youngsters already during World War I. The first efforts at recasting the exemplum as a work of juvenile literature may well be two products from 1917 by the American book illustrator and cartoon strip creator, Violet Moore Higgins. One volume with charming pictures by her was priced higher, whereas the other cheaper one had simpler artwork by another artist. The more elaborate in the pair of items containing the juggler narrative presents itself as a plain old children’s book. The only two giveaways to its application are first the legend “Story-Time Tales” affixed discreetly at the bottom of the front cover, and then the depiction of two youngsters ascending stairs with a candlestick, presumably on their way to tucking themselves docilely into bed after a rousing reading aloud. Yet the third and final story, “The Noel Candle,” ends on a note that infuses the volume with Christmas as an unquestionable occasion—and prospective market. The lower-budget book is equally fixated on yuletide.

Fig. 5.6 “To Give Is the Spirit of Christmas.” Illustration by Helen Chamberlin, 1917. Violet Moore Higgins, French Fairy Tales: The Little Juggler, The Wooden Shoe, and The Noel Candle (Racine, WI: Whitman, 1917), 6.

Higgins betrays evidence of having been conditioned by the poetic reshaping of France’s tale that we owe to Edwin Markham. The action of his poem, entitled “The Juggler of Touraine,” takes place in the French province that has Tours as its capital. In contrast, the later story by the illustrator is set in the similarly named but nonexistent “Tourlaine, a quaint old French village.” Yet her narrative amalgamates far more than merely one previous form of the text. In keeping with her evident ambition to inch the entertainer closer to fairy tale, she opens with the unchallenged marker of that genre in English, the phrase “Once upon a time.” In fact, one of the two 1917 versions of her book flagged “The Little Juggler” as belonging explicitly within that category of literature. Greater future repercussions came from the author’s decision to crank down the age of the hero, “not more than twelve.” Making the protagonist more youthful enabled young readers to identify more easily with him. Other versions had sometimes tugged the performer in the opposite direction, aging him into an old juggler, past the prime of his talents and his worklife.

Higgins makes her hero, named Rene, both a juggler and a dancer. While dancing, the boy wrenches his ankle badly and ends up convalescing in a monastery. The remainder of the story unfolds there, where he is bidden to remain and acquire an education (see Fig. 5.7). Eventually, the inevitable transpires: he dances and juggles before the Madonna (see Fig. 5.8). When he is spotted and spied upon, the statue springs to life, pats the boy on his pate, and with her scarlet mantle rubs the sweat from her small devotee’s glistening brow.

Fig. 5.7 “You May Stay Here and Learn.” Illustration by Helen Chamberlin, 1917. Violet Moore Higgins, French Fairy Tales: The Little Juggler, The Wooden Shoe, and The Noel Candle (Racine, WI: Whitman, 1917), 21.

Fig. 5.8 “Not a Ball Fell to the Floor.” Illustration by Helen Chamberlin, 1917. Violet Moore Higgins, French Fairy Tales: The Little Juggler, The Wooden Shoe, and The Noel Candle (Racine, WI: Whitman, 1917), 27.

Downsizing the Juggler

Did you ever hear of a little juggler who lived in the neighborhood of Paris many, many years ago and who won such favor in the eyes of the Holy Virgin that she performed a special miracle to show her appreciation of his adoration?

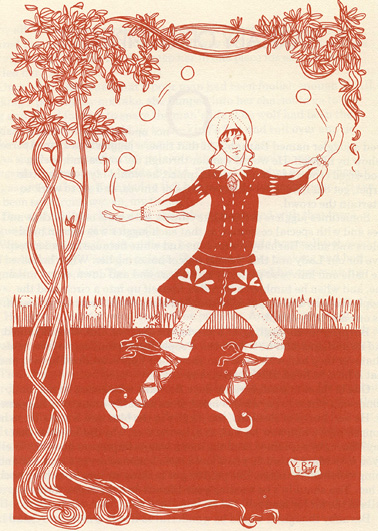

The littleness and youngness of the leading character are incorporated into the diminutive for “juggler” in the tale’s Spanish title, translatable as The Little Juggler of the Virgin, that was used in a large-format children’s book published in Chile in 1942. The writer made the star a young man, “twelve years old, more or less” (see Figs. 5.9 and 5.10). A short prelude furnishes almost all the context we can knit together:

In this tale is told an old story, full of naïveté and enchantment, passed down by tradition from the days of the Middle Ages. Its theme has served as an inspiration to various creative talents, in different periods. Now we offer the delightful medieval story, written in simple verses, to Spanish-speaking children.

For better or for worse, this publication is not quite as piquant a piece of evidence for the tale’s dissemination and taking root outside Europe and the United States as might appear at first blush. If readers sidle up to these pages in the hope of engaging with an indigenous Chilean storyteller and illustrator, they will have the rug pulled out from under them. The author was not a native of the New World. Rather, he was a temporary exile, or at least expatriate, from Spain. Over the course of his life, José María Souvirón was a writer, first a poet and then a novelist, as well as a critic and professor. He published profusely in Chile even before becoming a long-term transplant, and by 1941 he had settled there. His children’s book found its way into print early in his stint there. By 1953 the exile had gone back permanently to his homeland. A few years after his return, a scaled-down form of his volume was reprinted in a Madrid newspaper.

Fig. 5.9 The juggler in the town square. Illustration by Roser Bru, 1942. Published in José María Souviron, El juglarcillo de la Virgen (Santiago, Chile: Difusión Chilena, 1942), 3.

Fig. 5.10 The juggler before the image of the Virgin. Illustration by Roser Bru, 1942. Published in José María Souviron, El juglarcillo de la Virgen (Santiago, Chile: Difusión Chilena, 1942), 14.

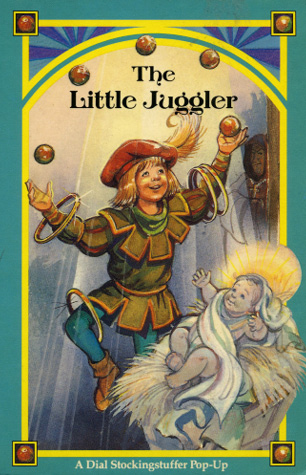

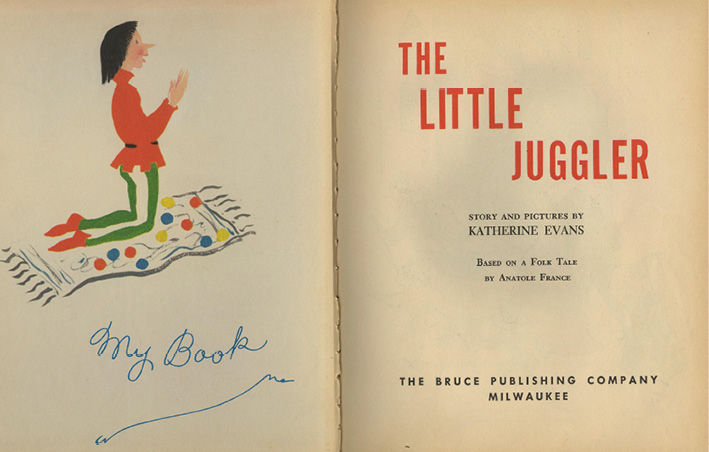

Other children’s versions often flaunt the adjective “little” in their titles, making the protagonist the little juggler, little tumbler, and little jester. So we have, for instance, “The Little Juggler” as the title for a retelling of an alleged folktale of the juggler in 2004 (see Fig. 5.11). The same title appears on a pop-up book from 1991 (see Fig. 5.12). A related shrinkage comes in tactile guise when the physical size of the printed form in which the story is presented is cut back. The most adroit mode of such reduction is the one known affectionately as “littles.” Those who collect such bijou books go by the name of microbibliophiles. These products do not contain miniatures, in the sense used for the paintings in medieval manuscripts. Instead, they are actual hardbacks produced in diminutive dimensions. By definition, they are normally supposed to be no more than three inches in height.

Fig. 5.11 The juggler performs before the statue of the Virgin and Child. Illustration by Christina Balit, 2004. Published in Lois Rock, Saintly Tales and Legends (Boston, MA: Pauline Books & Media, 2004), 33. Image courtesy of Christina Balit. All rights reserved.

Our story has been presented in this Lilliputian format for lovers of such “littles” as retold and illustrated by Maryline Poole Adams. Her output was immense, if that adjective may be applied non-oxymoronically to miniatures. In the world of bibliophiles, dealers, and librarians of rare books, this American bookmaker’s reputation rests securely on the creative and aesthetic gamut of such rarefied objects she crafted at a regular clip from her private press between 1979 and 2011 (see Fig. 5.13).

Fig. 5.12 Front cover of The Little Juggler (New York: Dial Press, 1991).

Fig. 5.13 Front cover of Maryline Poole Adams, Le Jongleur de Notre Dame / The Juggler of Notre Dame (Berkeley, CA: Poole Press, 2003).

Most of her oeuvre has Christmas themes. The inaugural volume, from 1979, is entitled Good King Wenceslas: A Celebration of the Carol by Rev. J. M. Neale, 1853, with Illustrations. The marbled paper of the cover gestures toward the nineteenth century. The first three woodblocks that illustrate the carol have as defining features the pointed arches that shout out “Gothic” and hence “medieval.” Another trait of her low-volume volumes was that they often call out to be operated. Rather than being static, they move like stagesets. Opening Matryoshka: Russian Nesting Dolls requires finding inset after inset, each smaller than the last. The total of five is a bookish equivalent to the dolls after which this item is named—and each component in the publication has one of them pictured on its cover. Her Song of the Wandering Aengus by William Butler Yeats has as a slipcase a miniature replica of a fisherman’s creel or tacklebox.

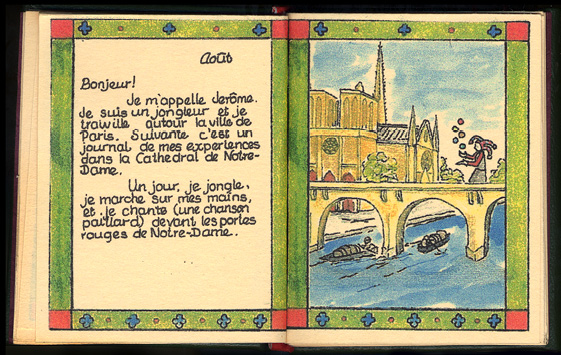

For the year of 2003 she crafted by hand her version of our story. Not to make too big a thing of it, but this “little” is very imaginative in both physical composition and literary content. As an object, the book has the distinctive structure known from the French as dos-à-dos. The “back to back” quality resides in the binding. Two parts, each of which has its own spine, share a back. Like Poole’s first volume, the covers of this lovely object are marbleized, looking like the front and back endpapers to nineteenth-century hardcovers. The illustrations are hand-colored.

In this case, both portions in the Siamese twin-like arrangement employ the same artwork. Half of this “little” is in English as The Juggler of Notre Dame: An Old French Legend Retold and Illustrated, recounting the legend through the third eye of an omniscient narrator. When the tiny tome is flipped over, the other portion is in French that can be translated as “The jongleur of Notre-Dame: An imagined journal on the topic of the old legend.” In the French-language section, the episode is presented in the first person as the diary of a boy juggler named Jérôme (see Fig. 5.14). This text includes occasional childish mistakes of spelling and grammar, for which the diarist apologizes at the end: whoops!

Fig. 5.14 Maryline Poole Adams, Le Jongleur de Notre Dame / The Juggler of Notre Dame (Berkeley, CA: Poole Press, 2003), 1–2. Image courtesy of Maryline Poole Adams. All rights reserved.

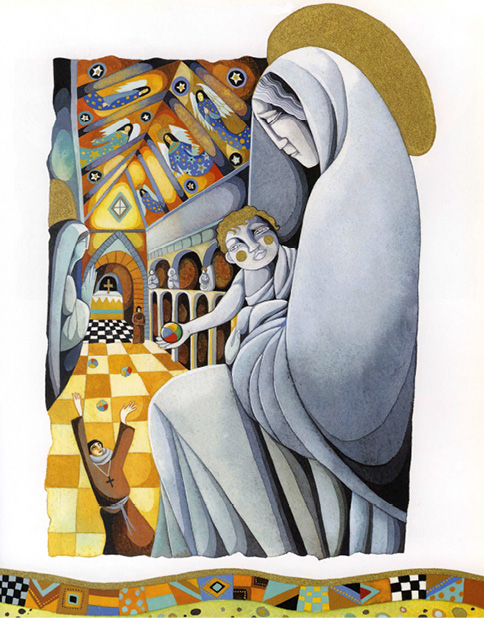

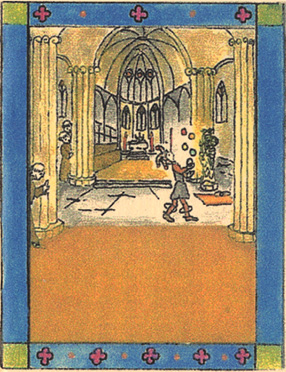

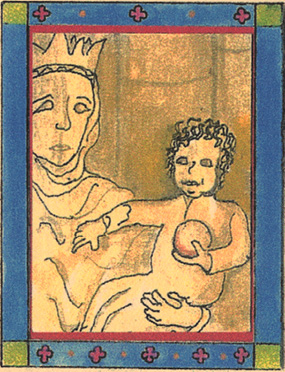

The story plays out in the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris. After a candlelit procession up the nave on Christmas eve, the events hit a crescendo. As the youth accomplishes feats of acrobatics and juggling before a beloved Madonna, monks spy on him. In their rush to judgment, they swoop in to stop him (see Fig. 5.15). Miraculously, his red ball takes flight and turns into a marble orb, held by the infant Jesus, who is supported by the Mary in the sculpture (see Fig. 5.16). Although the Virgin has her place in the story, the edifice named after her surpasses her in importance, and her son steals the limelight from her at the climax. From its initial production this publication was a collector’s item, as far from mass retail as could be conceived. To quote a well-turned phrase, a little can be a lot. No one who handles one of these books feels short-changed, despite their physical minimalism. Not all downsizing is nearly as artful.

Figs. 5.15 and 5.16 Two monks and the abbot spy on the juggler’s performance and Virgin and Child. Illustration by Maryline Poole Adams, 2003. Published in Maryline Poole Adams, Le Jongleur de Notre Dame / The Juggler of Notre Dame (Berkeley, CA: Poole Press, 2003). Image courtesy of Maryline Poole Adams. All rights reserved.

American Children’s Literature

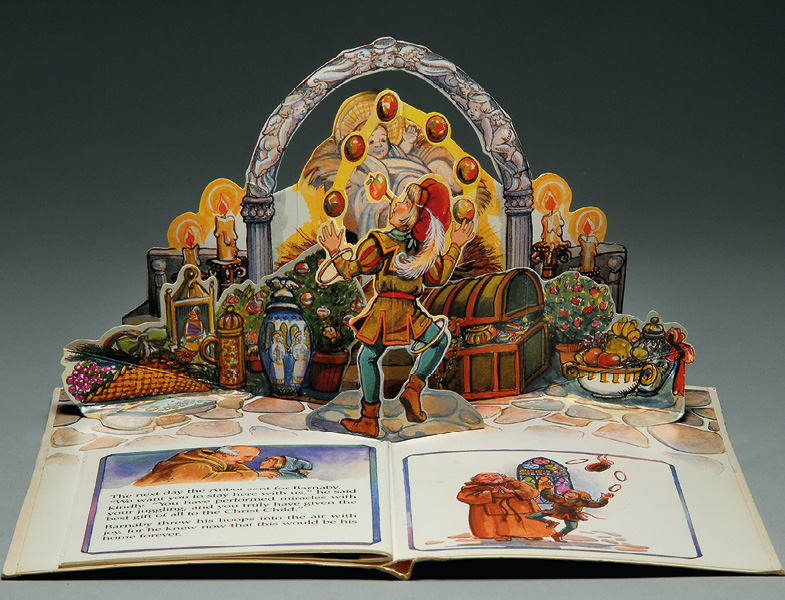

Some versions of the story for beginning readers have banalized it. Massive retrenchment is inevitable when the legend is scaled down to a booklet attached to a single pop-up (see Fig. 5.17). Such a conversion cannot help but make little of a narrative. But many recraftings of the tale as a children’s book have reflected pains on the part of their authors and illustrators to scrutinize the sources. After sifting through earlier versions, they have created new narrations and presentations consonant with the meanings they have found encoded in their predecessors. Such refashioning has functioned well within the confines of illustrated literature for the youth market.

Fig. 5.17 Pop-up of The Little Juggler (New York: Dial, 1991), opened to display climactic scene, with story pages in front.

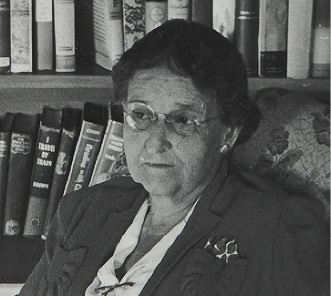

A retelling that hewed closely to the older tradition appeared in 1954, the work of Mary Fidelis Todd (see Fig. 5.18). A graphic designer, she specialized in writing and illustrating children’s books. She acknowledged that many forms had been written. Beyond the staples by Anatole France and Jules Massenet, she was aware of dramatizations for radio and television. She also singled out for special credit and commendation the version by Ruth Sawyer in her Way of the Storyteller. The tale’s association with oral storytelling, legend, and folktale—even when the orality has been substantially bogus—has helped secure for the juggler a niche in children’s literature akin to that of fairy tale and myth.

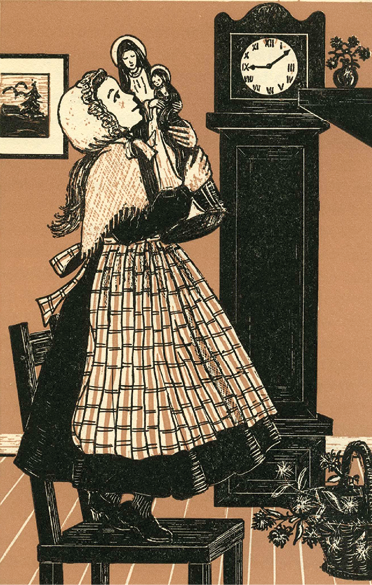

If one dimension of Todd’s attraction to the narrative lay in storytelling tradition, another was the draw of recounting a miracle of the Virgin that hinged on an image. A few years later she returned to similar terrain in writing of Saint Catherine Labouré. This Frenchwoman was born in 1806. When nine years old, she suffered the death of her mother. Shortly after the funeral and burial, the girl reputedly adjourned to her parents’ bedroom, clambered up on a chair, took down a statue of Mary that stood on a shelf, embraced it, and declared “Blessed Mother, you must be my Mother now.”

Fig. 5.18 The juggler before the Virgin. Illustration by Mary Fidelis Todd, 1954. Published in Mary Fidelis Todd, The Juggler of Notre Dame: An Old French Tale (New York: Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill, 1954), 35. Image courtesy of McGraw Hill. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.19 Zoé embraces the Madonna and Child. Illustration by Mary Fidelis Todd, 1956. Published in Mary Fidelis Todd, Song of the Dove: The Story of Saint Catherine Labouré and the Miraculous Medal (New York: P. J. Kenedy & Sons, 1956), 29.

Many years later, Labouré joined a Society of Apostolic Life (not an order of nuns) known as the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul. In 1830, she witnessed two episodes in which the Mother of God made herself felt, seen, and audible to her. Despite having had no formal schooling, the young woman rendered punctilious accounts of what she saw and heard in these experiences. She was forthcoming with much detail about Mary’s attire and coiffure. She was also unrelenting on the blaze of white light that preceded the Virgin, and the beams of jewel-colored luminosity that emanated from her hands.

Labouré received direction to have medallions struck after a design that was revealed to her in a vision (see Fig. 5.20). The visionary was assured that those who draped these tokens around their necks would be granted exceeding grace. The first specimens were minted in June of 1832. At most two years later, the badge came to be called simply the Miraculous Medal, in recognition of the miracles that were subsequently attributed to it by its wearers. The timing was propitious (or in another sense singularly unpropitious), since the recurrence of a cholera epidemic in Paris soon instigated a blind panic. In 1834, 150,000 of the pendants were distributed; in the following year, ten times that number. In the first decade in which the item existed, more than 100 million circulated both in France and abroad.

Fig. 5.20 Catherine Labouré’s Miraculous Medal of the Immaculate Conception, ca. 1832. Photograph from Wikimedia, 2007, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Miraculous_medal.jpg

Fig. 5.21 Postcard of the tomb of Catherine Labouré, Paris (early twentieth century).

The saint-to-be died on December 31, 1876, in the momentous 1870s. The end-of-days elements in the apparitions she perceived in 1830 were widely credited with foretelling the turmoil that befell France forty years later, during and after the Franco-Prussian War. When disinterred, Catherine Labouré’s body was discovered to be incorrupt. Since then, the corpse has been displayed in Paris in a glass casket at one of the places where Mary appeared to her (see Fig. 5.21). The visionary was beatified in 1933, a year in which many sightings of the Virgin took place in Belgium, and canonized in 1947. The apparitions Labouré experienced resemble those of the tumbler from the Middle Ages in a way that sets them apart from the other six officially certified ones that ensued in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Both the medieval lay brother and the nineteenth-century saint witness their visions within the confines of a cloistered religious community, and both are exempted from the public investigation outside that environment that became routine later. They resemble each other further in their anonymity. The tumbler is left unnamed in the two medieval accounts, while Catherine Labouré’s name and the nature of her exposure to the unearthly were suppressed until long afterward.

The tale of the juggler is easily encapsulated in a summary of just a few words. To approach the evidence from the Middle Ages, the late thirteenth-century Latin exemplum could have been a distillation, whether direct or indirect, of the account related in the French poem from a few decades earlier. Alternately, the précis in the learned language could itself have been the takeoff for the poetic work in the demotic. To leap forward more than a half millennium, Anatole France could have elaborated his famous short story from a single evocative sentence in Gaston Paris. Then again, he may have received additional inspiration from hearing Raymond de Borelli recite his poetastery on the same theme.

In 1954, the legend of the juggler saw its inaugural printing in a textbook for fledgling Latinists. The abridged translation, under the title “Our Lady’s Juggler,” appears not in a children’s book for entertainment but in a schoolbook for pedagogic purposes that can be imagined pocked with notes and battered in a knapsack. Amusingly, the version in this primer reconstitutes the story into Latin, nearly seven hundred years after its medieval precedent, but without awareness of it. In the short text, the protagonist is a juggler called Iohannes, corresponding to the French Jean. The choice of name and other features point straight toward Massenet. In the dead of a cold spell, the impoverished performer is taken in by Cistercians of Clairvaux. For two days, he has languished in a ditch. The white monks find him nearly starved to death. The brethren allow him to overwinter among them. A long while later, the Latin John droops in dejection over his inability to offer praise to the Virgin as the other denizens of the abbey do. Eventually, he finds a means of expressing himself in her honor. In the Marian month of May, he recounts one of his old stories and turns a cartwheel. The crisis in the tale is touched off when the brothers find out about the entertainer’s seemingly sacrilegious behavior: their analphabetic lay associate has failed to mind his monastic p’s and q’s. The abbot, just as he is poised to cast the juggler out of the chapel, is intercepted when the Madonna comes to life, smiles, and blesses the juggler.

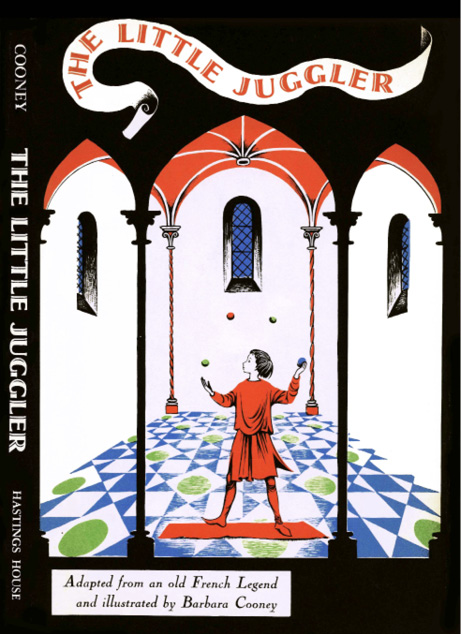

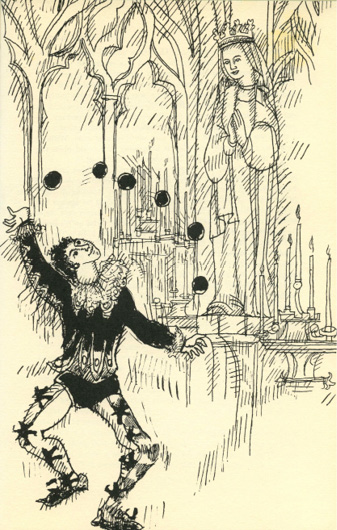

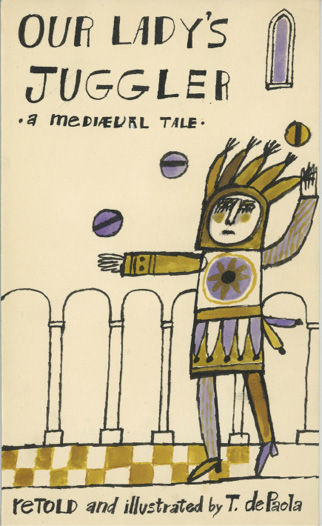

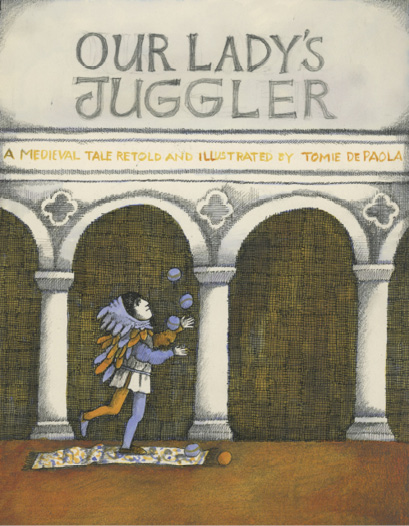

In 1959, the prolific children’s book illustrator Barbara Cooney won the first of her two Caldecott Medals, for an adaptation of Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale,”one of the Canterbury Tales. A reviewer praised her for her successful medievalism, with illustrations that “spread brilliantly over the pages, the country scenes filled with medieval details gleaned from study of old manuscripts.” In 1961, the author, doubtless heartened by her earlier triumph, tried her hand in her second picture book at another tale from the Middle Ages—ours (see Fig. 5.22). She professed to have had a lifelong infatuation with the legend that confirmed her ambition to be a children’s book illustrator. She had had her first brush with the jongleur of Notre Dame one Christmas some fifteen years earlier (in 1945 or thereabouts), when she heard a radio enactment. This exposure stimulated her to instill her version with a holiday theme, by relating how a little juggler searched for a gift especially suited for Christ and his mother. Her leading character is a penniless orphan who triumphs over penury when he realizes that he may make a gift of his skills as a performer.

Fig. 5.22 Front cover of Barbara Cooney, The Little Juggler (New York: Hastings House, 1961). Image courtesy of the Barbara Cooney Porter Royalty Trust. All rights reserved.

When The Little Juggler was reissued some two decades after its first appearance, Cooney called the reprinting her contribution to the yuletide season. Her foreword to the reprint from 1982 gives a succinct and well-read summation of the modern reception. When readying herself for the inaugural edition, she took in earnest her responsibilities as an illustrator by going on a preparatory expedition to France to familiarize herself with Tours and Normandy—and she infiltrated into her creation scenes based on what she saw. She gave serious attention in general to the Middle Ages, as an object for historicizing representation, and in particular to the early thirteenth-century tale of the jongleur. On the French research trip, she even obtained photographs of the only manuscript of the original verse that contained an illumination. In her text, she slips in here and there specimens of archaizing vocabulary and morphology: “methinks” and “naught” set the scene for the explicit “Here endeth the story of the little juggler of Our Lady.” Of a different order, she drops casually a simile lifted from the medieval French poem that describes a bull calf leaping and bounding before its mother. Additionally, she chanced to acquire a copy of the story in a Spanish-language children’s book: this must have been the remodeling of the tale that a Spanish author had published in 1942 in Chile. Although she knew full well the literary background to the narrative, she presents it at the outset as oral: a “tale I now will tell you even as it was told to me.”

The style she chose for her artwork resembles the spareness of some theatrical and operatic stage scenery, a quality that recurs later in Tomie dePaola’s illustrations of his version for children. This tendency for the visual settings of picture books to resemble the painted backgrounds in theater sets is widespread. The most moving testimony to Barbara Cooney’s love for the story is that she resolved to name her son, even before his conception, after its hero. In the reprint, she dedicated the book to that child, the present-day Barnaby Porter, whose first name indicates that his mother fused, as many tellers both before and after her have done, elements of both the medieval tale itself and Anatole France’s adaptation. In turn, her adaptation exercised appreciable influence on later authors of children’s literature.

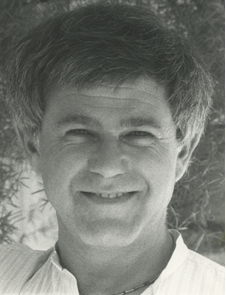

Between the first printing and the reprinting of the narrative by Cooney, Louis Untermeyer composed a retelling of it in 1968 (see Fig. 5.23). In one distinctive feature of the reworking by this prolific former US Poet Laureate, the juggler learns from a dream that he should express his devotion to the Virgin by doing his routine for her. The character is described as “little” only once in the story. The rest of the time, the emphasis rests mainly upon his destitution. He is emphatically a poor little entertainer. By being impoverished in the real world, and lacking stature within the powerful institution of the monastery, he bore a resemblance to the author himself. In the preceding decade, Untermeyer had been blacklisted during the days of the House Un-American Activities Committee. He may not have been a practicing communist, as he was accused of being, but by the time when he wrote his later précis of the tale about the medieval performer, he had not lost the concern for the powerless and needy that his early Marxism had inculcated in him. In addition, the mishap gave him to understand (better than ever before) the plight of lacking resources, having trouble securing gainful employment, and suffering from espionage by hostile colleagues. Untermeyer had more than enough reason to identify with the medieval protagonist.

Fig. 5.23 The juggler performs before the Madonna. Illustration by Mae Gerhard, 1968. Published in Louis Untermeyer, The Fire Bringer, and Other Great Stories (New York: M. Evans, 1968), 209. Image courtesy of Rowman & Littlefield. All rights reserved.

In a 1991 account by Joe Hayes, the story bears one of its conventional titles, “The Juggler of Notre Dame.” The piece appears in a booklet that assembles seven holiday tales. The storyteller recasts children’s versions along the lines of The Little Juggler, in which the hero is represented as a ragamuffin, by fusing it with other forms, in which the poor fellow is portrayed as being in his dotage: the narrator leaps from the juggler’s boyhood to his twilight years. He sets the story on Christmas Eve and makes the miracle that the ailing old artist, far from being the mere whelp he once was, can measure up as well as he ever did in his youth, and thereby brings a smile to the previously dour faces on a beautiful carving of the Virgin Mary holding the child Jesus in her arms. The aged man passes away from a burst heart just after heaving aloft a bright red ball, which the image of the child holds at the end of the narrative.

In 1999, a team of two brothers, the author Mark Shannon and the illustrator David Shannon, revamped the tale radically in The Acrobat & the Angel. Their reconsideration accentuates the outsized strength and spirit that are discernible even in undersized children. In their collaborative retelling, the standout is a boy called Péquelé—a tipoff that the author had been exposed to the version of our story by Henri Pourrat. The future leaper is introduced when still a baby. Soon he loses his mother and father to the plague, bringing a characteristically medieval touch to the narrative. Now an orphan, the youth has no memory or souvenir of his progenitors, besides a homegrown angel that his mother had fashioned for him from sprays of dried flowers. The penniless, orphaned unfortunate goes to live with his grandmother. A born acrobat, he can alleviate their abject poverty only by the pittance he earns from his busking. After his elderly caregiver too dies, he falls on still harder days. Ultimately, he collapses by a roadside cross. The waif awakes to find himself in a friary, where he has been taken in by an open-hearted monk.

Initially, the head of the monastery expostulates with Péquelé, who has been doing handsprings and back flips before a statue of an angel, and makes him promise to give up his acrobatics (see Fig. 5.24). Then, a woman arrives with an infant suffering from the pathogen. The stealthy performer breaks his earlier word and cheers up the dying babe by turning somersaults. The abbot is incensed at this disorderly conduct and ejects the restive boy-athlete from the brotherhood. Even so, Péquelé reenters to entertain the angelic effigy one final time. At this juncture, the image becomes animate and the messenger of God carries him aloft to heaven. Thereafter a statue of the acrobat himself is erected to replace the one that has flown the coop, the tot is healed (see Fig. 5.25), the pestilence subsides, and all ends happily. Rather than being punished, the boy is rewarded for putting on a show.

Fig. 5.24 The boy acrobat soars. Illustration by David Shannon, 1999. Published in Mark Shannon, The Acrobat and the Angel (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1999), 22–23. Image courtesy of David Shannon. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.25 The mother and her plague-ridden infant, now healed. Illustration by David Shannon, 1999. Published in Mark Shannon, The Acrobat and the Angel (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1999), 28. Image courtesy of David Shannon. All rights reserved.

In the picture book by the Shannons, the generous heroism of the good-as-gold gymnast is brought home by the protectiveness he shows toward a person still smaller and more vulnerable than himself. Among other changes worth contemplating is the replacement of the Madonna by a carving of an angel. This modification makes the story a shade more ecumenical, while simultaneously maintaining a kind of gender balance among the main actors. Visually, the role of Mary and the baby Jesus is filled through the mother with the plague-infected little one. In the acrylic illustrations, the characters are framed within stone archways adorned with flowers and gargoyles.

The success of The Acrobat & the Angel may have spurred the Shannons to return five years later to another medieval topic, in Gawain and the Green Knight. The Middle Ages can be habit-forming. In due course, the siblings’ volume on the boy wonder was featured in a manual geared to middle-school teachers who wished to incorporate picture books and novels into their curricula. A section on miracles discusses the illustrated retelling by the two brothers, and the suggested study questions demand that pupils define a miracle and devise modern equivalents. As for the nature of the Middle Ages, the slant is unambiguous: “The plague and many other hardships were a part of medieval life. Why do you think miracles were an important part of these people’s beliefs?” The spirit is materialized, the miraculous rationalized. Welcome to the twenty-first century. For all the claims of moral superiority over the past that some of its inhabitants may make, our era is, like all its predecessors, not without its favoritisms and prejudices about earlier times, peoples, and individuals. The juggler can help, by making manifest that humility is in order.

European Children’s Literature

The tale of Le jongleur de Notre Dame insinuated itself early first into children’s newspapers and magazines, and then into comic book-like publications in France. Young adults were exposed to the narrative. The story was sometimes presented to these readers as having been composed by Anatole France but often as having emerged anonymously. Both perspectives have a modicum of truth to them. In any case, the information conveyed to youngsters corroborated the status of Our Lady’s Tumbler as a universal tale, folktale, or saint’s life. The narrative’s circulation in comics assisted in promulgating it in other guises for youthful audiences, such as popular fiction and cinema. Many other media purvey images of jongleurs that are colorfully indistinct and historically inaccurate.

A children’s movie made in France in 1965, with animated puppet-like figures, deserves more than passing mention. In it the fiction, in a modified form of Anatole France’s version, is treated respectfully but also not without gentle humor. The French author himself, with his refined irony, would have approved. The events take place in the Middle Ages. A juggler named Barnabas has success by summer, but war, winter, and famine drive him to a sorry pass of grinding poverty, teeth-chattering cold, and aching hunger. A monk in transit finds him freezing and frostbitten, and brings him to his monastery. In the abbey, the entertainer tries and fails at various vocations. From these vicissitudes, he realizes that he is unsuited to any monastic function. Despondent, he darts into the church one night and displays his craft to the Virgin. The other brothers have been stumped and frustrated by their odd guest. Awakened by the racket, they arrive in the nick of time to see Barnabas keel over, as if dead, to the ground.

The brethren’s astonishment increases when they see a rose drop miraculously from Mary’s hand upon the juggler as he lies before her. The motif of the flower at the end of the tale is familiar from other medieval miracles of the Virgin. The rose and lily are both associated with sanctity, although the red more often with martyrs and the white with virgins—and therefore the Virgin with a capital V. Since the gesture takes place unbeknownst to the performer and sometimes even after his death, the floral touch could be related to the secrecy that since the sixteenth century has been associated with the rosaceae family. Who could forget the expression “sub rosa,” describing something done behind closed doors?

The prominence of armed conflict in the animation may well reflect the tensions of the Cold War. Worry about nuclear armageddon was so widespread that we should not feel obliged to seek out a proximate source. Alternatively, the blossom and the bellicosity could be an implicit nod toward R. O. Blechman’s storybook and animated cartoon from the 1950s, both of which radiated a like concern with the perils of warfare. Although the French translation of his protographic novel came into print only early in the third millennium, Blechman may well have been a known quantity in France long before then among cognoscenti.

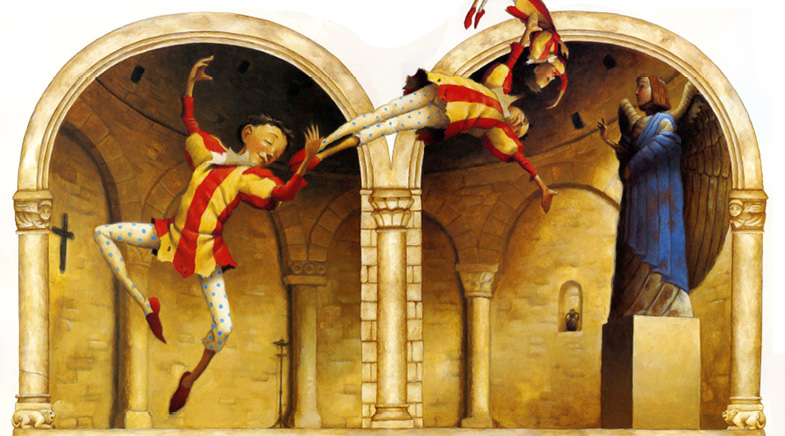

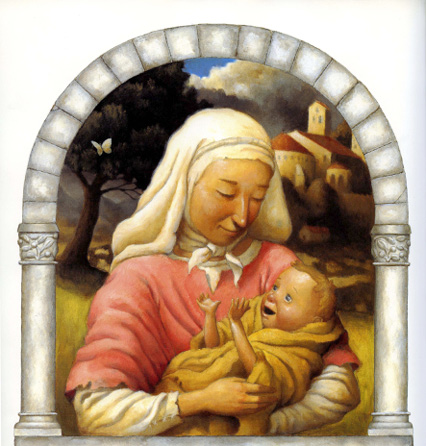

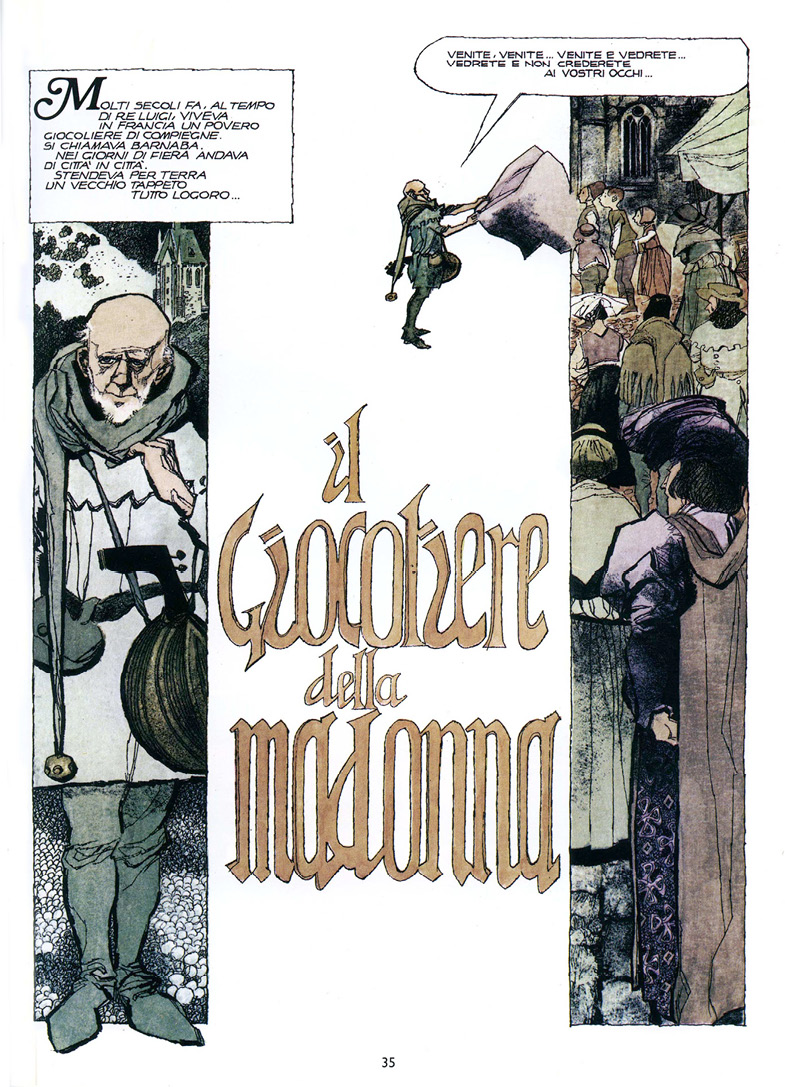

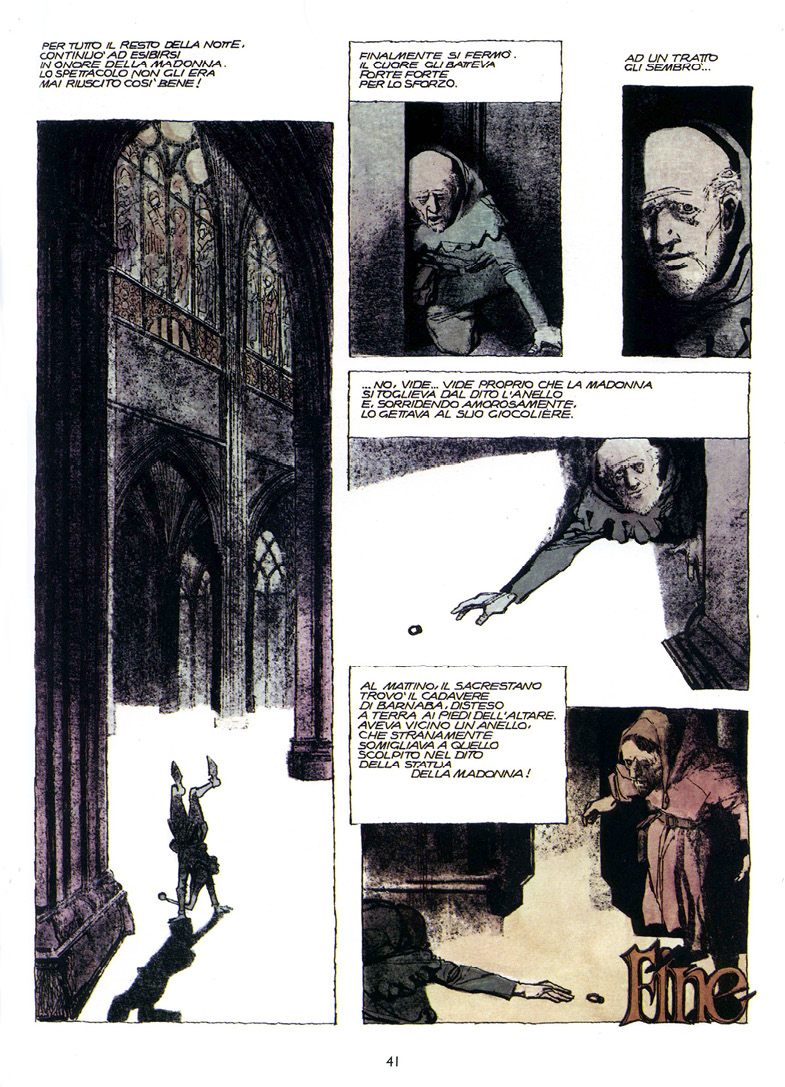

In 1976, the husband-and-wife team of Dino and Laura Battaglia created a short graphic novella, or long graphic short story, with a title that can be put into English as “The Madonna’s Juggler” (see Fig. 5.26). The Italian artist had earlier made a specialty of illustrating fairy tales, children’s books, classic novels and short stories, and episodes from the Bible. At the outset, this comic book-like reimagining of the jongleur tale cleaves closely to Anatole France’s treatment, even down to the names of King Louis, Compiègne, and Barnaby. Yet the collaborators show and tell the main events more darkly than in the French Nobel prizewinner’s reconception. On the final three sides of this graphic novelization (or novella-ization), Barnaby withdraws from the monastery, enters the cathedral in a small city, and performs before a statue of the Madonna—without child. The miraculous occurs when, in an age-old motif influenced by accounts in which young men become engaged to statues, the Madonna lobs him the ring from her finger. At this pinnacle, the entertainer expires (see Fig. 5.27).

Fig. 5.26 First page of “Il giocoliere della Madonna” (1976), in Dino Battaglia, Leggende, 2nd ed. (Grumo Nevano, Italy: Grifo Edizioni, 2004), 35. Image courtesy of Grifo. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.27 Final page of “Il giocoliere della Madonna” (1976), in Dino Battaglia, Leggende, 2nd ed. (Grumo Nevano, Italy: Grifo, 2004), 41. Image courtesy of Grifo. All rights reserved.

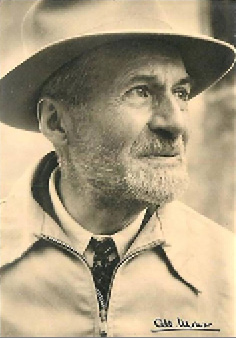

A writer who engaged intensively with the juggler story and close analogues to it was Max Bolliger (see Fig. 5.28), a productive and highly regarded Swiss author of more than fifty books for children and young adults. A significant proportion of his tales relate to the Bible or Christian legend. For example, he published a kind of hagiographic yearbook, in which he made sure that each month had at least a few saintly women and men with feast days in it. The first of these holy people is Simeon the Stylite, who took his epithet from having constrained himself to the ascetic isolation and containment of dwelling atop a freestanding column (stûlos in Greek). This pillar saint inspired the young Anatole France. The collection of saints’ lives also encompasses holy fools as well as all manner of other colorful legends.

Fig. 5.28 Max Bolliger. Photograph, before 2013. Photographer unknown.

Much of Bolliger’s oeuvre, moreover, is set at Noel. In 1999, he came out with what is called in English The Way to the Stable: A Christmas Story. The tale tells of a shepherd who could get around only with crutches and who lived alone in the hills until angelic voices led his peers to Bethlehem. After demurring from following them, the hesitant herder, halt and lame, finally hobbles his way to the stalls where the animals are kept. Despite failing to locate the holy family, he finds that miraculously he is no longer crippled. Analogies to Amahl are strong.

The closest to Our Lady’s Tumbler among Bolliger’s robust output—beyond his explicit retelling of the tale—may be the narrative of the Christmas fool. The lead character is designated in the Italian translation by the term that denotes, and derives from, jongleur. An imbecile who resides in the East happens, like the three Magi, to catch sight of the astronomical prodigy of the star at Christ’s birth. Bringing with him his only three possessions, he sets out to pay his respects, but on the way he gives away what he has brought. First, he offers his fool’s cap to a paralytic; then, his bells to a blind boy; and finally, his flower to a deaf one. When at length he comes on scene, Mary would like someone to hold the Child. The three wise kings have their hands full with gold, frankincense, and myrrh, while Joseph is occupied with the animals in the stall. Consequently, the Virgin deposits the infant Jesus in the arms of the empty-handed and -headed Noel nincompoop. The moral of the story is that by giving away all that he possesses, the dolt acquires the prudence he craved at the outset. The theology is left unsaid, but Jacob becomes himself a throne of wisdom by supporting the member of the Trinity who embodies that quality.

In 1991, Bolliger published a beautifully illustrated Swiss children’s storybook, under a title that could be rendered as Jacob the Juggler: Newly Told, after a French Legend of the Thirteenth Century. His German employs unfussy language and style well suited to the chief character and central topic. He relates how the jongleur rambles from place to place, tickling people’s fancy with his dances and leaps. Eventually he endeavors to satisfy his craving for peace and quiet by joining monks in the seclusion of a monastery, but he soon realizes that he is an outsider among them. Through a miracle, the Virgin Mary brings the abbot and the other monks to the insight that God can take pleasure in the service even of a lowly jongleur. The tale as recounted by Bolliger warrants the qualification “newly told” that figures in the title. For a start, the protagonist is given the fresh name of Jacob. The opening words of the text proper are the German equivalent of “once upon a time.” Straightaway after the gambit of this stereotype, the juggler-tumbler is introduced. From other versions of the narrative, we have learned how readily it can shade into the fairy tale genre.

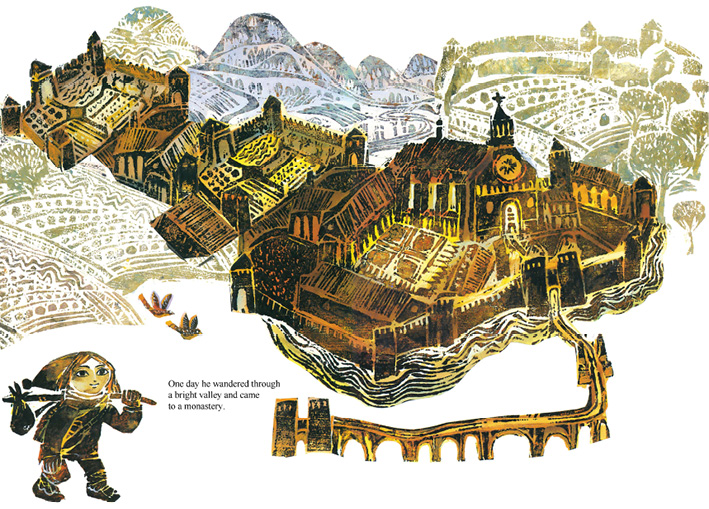

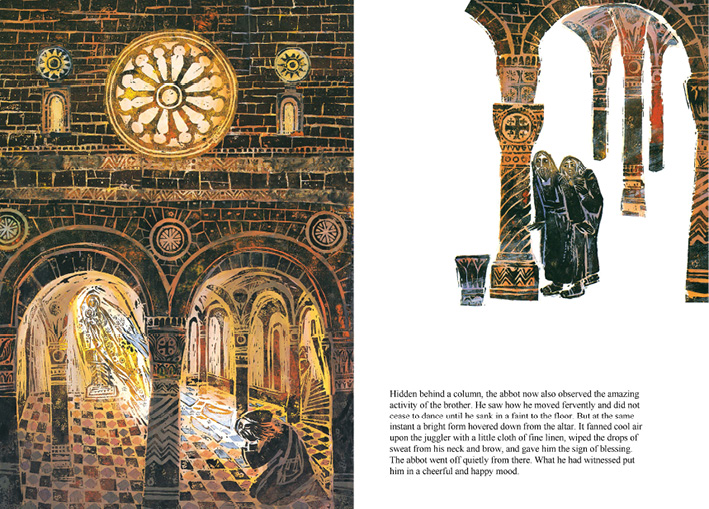

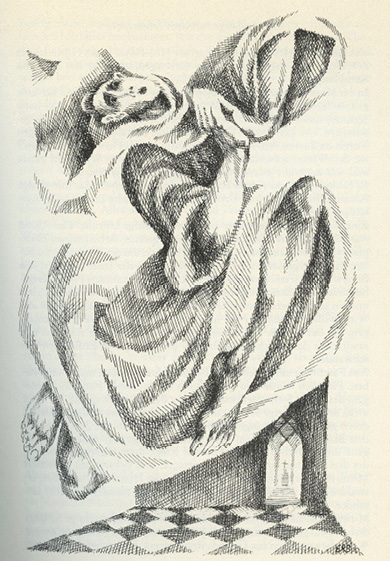

Although the essential contours of the story conform to the medieval poem, minor deviations from the account as recounted in the French verse from the Middle Ages begin almost at once. The title character is presented as “young,” and depicted as being small. He forsakes the wayfaring life mainly because he dislikes the hubbub associated with performance. At the same time, Bolliger indicates subtly on the second page that he knows the original text and has grappled with it. Though he leaves nameless the monastery in which the juggler seeks refuge from the world, he tells how Jacob “wandered through a bright valley” to reach it (see Fig. 5.29), alluding subtly to the onomastic meaning of the French Clairvaux, “bright valley.” Bolliger’s retelling glints with other distinctive features. For example, the unbookish and Latinless juggler pitches himself into gardening as a means of contributing to monastic work. He discovers underground a forsaken chapel, where he runs through his routine, but only after Mary speaks to him, through the intermediary of a statue of the Virgin and Child. The make-or-break miracle involves the Madonna. Amid a blaze of light, she fans the juggler with a linen cloth, pats down the sweat from his neck and forehead, and blesses him (see Fig. 5.30).

Fig. 5.29 The juggler wanders through a valley. Illustration by Štěpán Zavřel, 1991. Published in Max Bolliger, Jakob der Gaukler (Zurich: Bohem, 1991), as now trans. Jan M. Ziolkowski, Jacob the Juggler (Trieste, Italy: Bohem, 2018), 8–9. © Heirs of Štěpán Zavřel. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.30 The miracle of the Virgin. Illustration by Štěpán Zavřel, 2018. Published in Max Bolliger, Jacob the Juggler (Trieste, Italy: Bohem, 2018), 24–25. © Heirs of Štěpán Zavřel. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.31 Štěpán Zavřel. Photograph, 1992. Photographer unknown. Photograph Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stepan_Zavrel_a_1992-12-26_2.JPG

The artwork came from Štěpán Zavřel (see Fig. 5.31), a Czech-born artist with a strong profile in children’s book illustration. His contributions for Jacob the Juggler reflect the architecture prevalent in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy where he lived. Most germanely, he intensified the local flavor of a strictly Lombard Romanesque architecture, with thick walls and rounded ornamental arches. Zavřel’s art here calls to mind the style of woodblocks. Since at least the expressionists of the early twentieth century, above all in Germanic countries, woodcuts have been regarded as lending themselves especially well to material of medieval origins.

In 1996, another version for a youthful audience was produced elsewhere in Switzerland, in this case in Italian. Elena Wullschleger Daldini produced her first major children’s book by teaming up with the artist Fiorenza Casanova. No sources are identified, but the title may be translated into English as Barnaby the Jongleur: A Medieval Legend. Despite the subtitle, this reinvention embroiders upon the tale as told by Anatole France and not upon the poem from the thirteenth century. The events are set in the kingdom of France in the reign of King Louis, and the main actor is a poor jongleur who bears the name that goes back to the late nineteenth-century short fiction.

More recently still, the medieval story’s potential to be embellished in a medievalesque style has been exploited again in an engaging work of children’s literature. In 2000, Helena Olofsson published The Little Jester in Swedish. Although the setting remains a French abbey in the Middle Ages, and the cynosure is again as sometimes in the past a boy, his profession has modulated to what is implied by the English title. Within the book, the author and illustrator of juvenile fiction placed intense emphasis upon the visual arts, focusing not only on the lovely pictures that illuminators from centuries ago painted in manuscripts, but also upon a depiction of a lachrymose Madonna located above the altar. The portrait of the boohooing Mary, the most beautiful in the monastery, is the object of Mariolatry. The monks execute their offices specifically in honor of the image, which “wept over all the bad things happening in the world” (see Fig. 5.32). The depiction of the weeping Virgin calls to mind miracles in which images, particularly statues, exude tears of water, blood, oil, or other liquids. In this case, the wonder happens when the representation of the Mother of God ceases to sniffle and instead smiles (see Fig. 5.33).

Fig. 5.32 The juggler performs. Illustration by Helena Olofsson, 2000. Published in Helena Olofsson, The Little Jester, trans. Kjersti Board (Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren Bokförlag, 2002), 15. Image courtesy of Helena Olofsson. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.33 The Madonna smiles. Illustration by Helena Olofsson, 2000. Published in Helena Olofsson, The Little Jester, trans. Kjersti Board (Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren Bokförlag, 2002), 21. Image courtesy of Helena Olofsson. All rights reserved.

Olofsson’s narrative appears in a children’s hardcover, not a historical treatise. At the same time, she puts her finger inadvertently on a pattern that reaches back centuries. In 1657, Wilhelm Gumppenberg published in Latin the first impression of a sprawling handbook that could be called in English Marian Atlas, or, On Miraculous Images of the Mother of God, throughout the Christian World. By the definitive edition of 1672, the German Jesuit had expanded the initial assemblage of 100 entries to a grand total of 1200. Among a myriad of other occurrences, he recounted in the later expansion experiences that took place in Prato over two and a half years from July 6, 1484. During this period, individuals and throngs saw a Madonna painted on the wall of the prison house that seemed to them to become animate: its eyeballs rolled as if deep-set in their sockets, and its demeanor looked now heavy-hearted, now beaming. Eventually, a basilica was built on the site in commemoration. The church is called Santa Maria delle Carceri, which equates in English to Saint Mary of the Prison.

In Olofsson’s telling, the unidentified boy jester, after being permitted to enter the abbey, accomplishes spine-tingling feats of balancing, prestidigitation, instrumentalism, dancing, and juggling. His gags ravish the monks, antagonize the prior, and cause a miraculous outcome, when the teary-eyed Madonna cracks a smile. The book has pseudomedieval embellishments on six pages. These one half dozen sides are made to resemble rectos and versos of folios in codices from the Middle Ages, with meticulous illustrations and elaborate marginalia. Whatever the immediate sources of inspiration, the visual and textual handling of the tale by the Swedish children’s author and adorner aims at fidelity to medieval culture, even if it alters the narrative by substituting the motif of the weepy painting for the statue. In a way, its contrast of repentance with laughing captures a salient aspect of Our Lady’s Tumbler. The dust jacket sums up the hardback as being “about the transformative power of laughter and creativity.” In its own way, the modern narrative holds very true to much of the spirit of the thirteenth-century French original. At the same time it imparts a sharply different spin. A young entertainer relieves the Virgin, rather than vice versa. Its happy ending has the jester retire from the monastery for a successful career.

Olofsson came across the legend while delving into the history of the circus. One book on the big top offered a short wrap-up of the medieval story. Upon reading these few sentences, she was stirred to put aside her work on companies of traveling entertainers who perform in tents. Instead, she embarked upon the new project that would become The Little Jester. The situation resembles what we have seen at the latest since Anatole France: through scholarship, a writer is exposed to a précis of the narrative that she fleshes out into a telling of her own making.

As an art therapist (and practicing artist), Olofsson made out at the heart of the miracle a very zestful message about the power of art. In her psychological interpretation, the monastery represents a rigid personality that is ruled by a harsh superego, personified by the abbot. This leader keeps the abbey closed to the rest of the world and organizes life strictly. The order and and stability come at the cost of joy. Depression follows, embodied in the weeping Madonna. The jester and child who is the hero of the story embodies artistry. He introduces creativity that revolutionizes the status quo within the abbey. The institution throws open its doors, both literally and figuratively. The monks gain charity, joy, and empathy with the destitute and vulnerable. As an index of the change for the better, the Madonna no longer mourns but smiles.

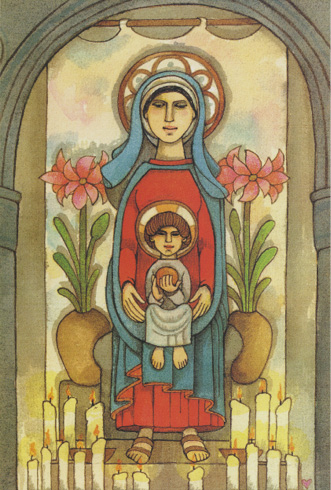

Worthy of additional note is an adaptation into German by Tatiana von Metternich, published in 1999. This Russian-born princess, an émigrée to Germany, shaped a version of the tale in her adoptive language and in rhymed couplets, beautified with her watercolors. She situates the story in a small village, and stages events on August 15, the feast day of the Assumption of the Virgin into Heaven. The juggler, manipulating six golden balls, expects a payout from the festival attendees, but instead goes unregarded. He slips into the church, where he intermittently snoozes and prays admiringly to the Madonna, a richly bejeweled, pearl-studded, and veiled statue (see Fig. 5.34). Whereas the other worshipers arrive bearing more substantial offerings, his only contribution is to toss his half dozen spheres. Unfortunately, the parishioners, when they step on scene, disapprove with more than mere pursed lips or pouts; they strong-arm him to his knees and trample his juggling equipment underfoot. As they do so, the image comes to life, bends down, and gently lays her pearly veil upon the juggler’s tear-smudged face (see Fig. 5.35). The churchgoers now understand that heartfelt humility alone can win blessing. Metternich presented her book as a religious offering, to bring home the acceptability of gifts, whether offertory candles, alms, or humble artwork (presumably such as her own publication), as a kind of prayer.

Fig. 5.34 Tatiana von Metternich, Der Gaukler der Jungfrau Maria (Wiesbaden, Germany: Modul, 1999), 16.

Fig. 5.35 Tatiana von Metternich, Der Gaukler der Jungfrau Maria (Wiesbaden, Germany: Modul, 1999), 24.

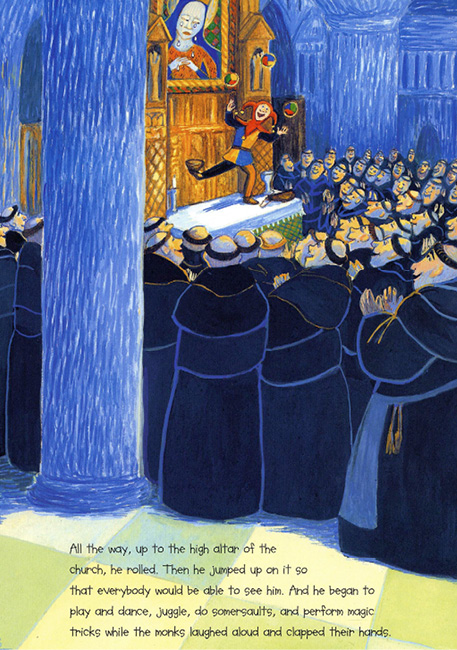

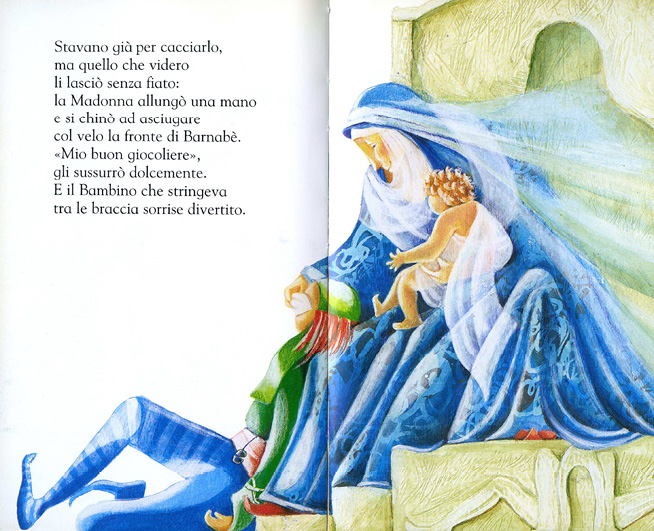

A relative Johnny-come-lately is a specimen of children’s literature from Italy called, to put the title into English, Maria’s Juggler (see Fig. 5.36). This slim paperback, dated 2005, purveys a retelling very much along the lines of Anatole France’s tale. This version is printed by a religious publishing house, in a series—as stated on the cover—of “exquisite stories, legends, and tales from the Bible and the Christian tradition.” This product aims to bring home two themes. One is that everyone has something to give. The other is that the devotion of the little juggler and acrobat, because of its sincerity, gratifies the Virgin more than the supposed piety of the other brothers. Here the performer is called Barnabè, the Italian equivalent of the name first attached to the protagonist by Anatole France. Despite his inability to write or to intone liturgical song, this character has tricks and stunts that please one and all. In the climactic episode, the monks see him as he runs through his routine, but they troop away in silence after Mary strokes his forehead with her veil (see Fig. 5.37).

Fig. 5.36 Front cover of Alberto Benevelli, Il giocoliere di Maria, illus. Manuela Marchesan (Milan, Italy: San Paolo, 2005).

Fig. 5.37 Alberto Benevelli, Il giocoliere di Maria, illus. Manuela Marchesan (Milan, Italy: San Paolo, 2005), 25–26.

The tale was implanted for a long while in the canon of French scholastic literature in almost the opposite spirit. This canonization can be traced in treasuries of stories for both primary and secondary school. For instance, the narrative was enshrined among a section of fabliaux in a high school textbook that became a standard from 1960. It was assigned a four-word heading that means “The Notre Dame Tumbler,” but for all its brevity it served notice in two ways that the reader is about to be transported into olden times. First, in modern French, the noun for “tumbler” evoked problematic associations of “lady’s man.” To eschew those connotations carried by tombeur, the substantive had to be construed in an obsolete sense. Second, the preposition was omitted that nowadays ordinarily signals “of.” Thus, both vocabulary and syntax made perfectly clear that the short title was not to be taken at face value.

The introductory remarks point to Christian virtues of humility and penance. A reference to the twelfth-century cult of Mary leads in turn to mention of the Marian poet Gautier de Coinci. The most famous of fabliaux about miracles of the Virgin is purportedly Our Lady’s Tumbler. The anthology makes no bones that this edifying narrative inspired first Anatole France and then Jules Massenet. In broad strokes, adolescent readers were afforded insights into French culture of the Middle Ages as the elite of around 1960 still wished, not without appreciable justification, to envisage it: Christian values, veneration of the Virgin, a major author, and two significant genres, fabliau and miracle. Equally important, the equivalent of high-school students in France received a reassuring suggestion that their national culture stretched stably and continuously from seven or eight centuries earlier up to what was then the present day: Frenchness was a bridge, Gothic and cutting-edge like its Brooklyn peer, grounded sturdily at one end in the medieval period and at the other in modernity.

After selected passages paraphrased in present-day French, the textbook poses a battery of to-the-point queries. Some relate straightforwardly to the actions and motivations of the principal character, such as why the jongleur decided to pray as he did, what feelings motivated him, and how the author depicted his physical movements. Others trend to the more sophisticated. For example, the young reader is quizzed on how the poet conjured up an atmosphere befitting what could be put clumsily into English as the “Christian marvelous.” This term refers to a range of phenomena, from dragons and demons through ghosts and resurrections. The rapid-fire questions asked of the text build up to the most mystifying puzzle of all, namely, what lesson is to be drawn from this edifying tale?

A later collection, pitched at elementary-school readers eight to twelve years of age, spotlights a fiction by a writer who has made a specialty of historical novels set in the medieval era. Although the book is not packaged explicitly as dealing with France, the cover is awash in Gallic heroism, cleverness, and gravitas. To be specific, it depicts the climactic scene in the Song of Roland in which the dying hero sounds the horn Oliphant. In smaller circles to the left it shows Reynard the Fox and Charlemagne. The blurb on the back cover concludes “Ten tales, legends, and fables for journeying into the terrible or comic world of our Middle Ages”: no doubt can exist that the first-person possessive plural in this case is a stand-in for French.

The miscellany is entitled, to translate into English, Tales and Legends of the Middle Ages. In its table of contents, our narrative is classed among “moral or edifying tales,” as a subdivision of fabliaux. To all appearances, the jongleur owes his place among such comic stories to nothing more substantial than its brevity. The piece is paired, somewhat bizarrely, with the fabliau known as “The Divided Horse Blanket.” At the same time, it would be unfair not to acknowledge that the compiler demonstrates close knowledge of either the thirteenth-century French prototype or a trustworthy modern translation of it.

A third volume of medieval stories for children was printed in 2004. It is devoted to a fairy-tale world ruled by a harsh dualism. This compilation has notes and detailed queries about culture and Christianity in the Middle Ages. In this compendium, the medieval entertainer takes a place amid such mixed company as the biblical Samson and Delilah (to whom fleeting reference is also made in Anatole France’s short story), the Odyssean Ulysses and Polyphemus, the Greek mythological Apollo and Daphne, and the more recent fairy-tale characters Cinderella and the clever little tailor. Our Lady’s Tumbler is subsumed within a larger class of fictions, “marvelous tales.” This subgenre would correspond to the technical term “wonder tales” or to the less precise “fairy tales.” The narrative from the thirteenth century is labeled specifically as belonging to “Christian marvelous,” to all intents and purposes a domain parallel to the officially approved “miraculous.” This world seems to be well on the way to the fantastic, and hence the science fiction with which in due course the American sci-fi writer Robert Heinlein associated the story.

The three French anthologies are too disparate to permit confident inferences and generalizations about the evolution of what is being made of Our Lady’s Tumbler. We might speculate that even in a present-day culture with a majority Christian population, it remains conceivable to focus on situating the tale in the religious framework of the early thirteenth century. Yet what is emphasized about that setting may have passed over a watershed, in response to increasing secularization and changing demographics within the society of France. If the narrative can be merchandised mainly for its virtues as a literary fantasy, it may stand a better chance of not being ousted from the curriculum than by stressing the particularities of its relation to medieval Marianism.

Will it be feasible much longer to expect students in secondary school to be aware of an overarching French culture that joins Gautier de Coinci and fabliaux from the Middle Ages on the one side to Anatole France and Jules Massenet on the other? With much help from the results of sustained excavation into the past of six or seven hundred years earlier, philologists, men of letters, composers, and others in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries constructed a nationalizing high culture for France that held strong for more than a century. Now it needs reevaluation, which will culminate at least in modification, or at the most extreme in abandonment.

Global Children’s Entertainment

José Maria Sánchez-Silva is the only author from Spain who has ever been awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Award for children’s literature. In his early reportage and other writings he was tied closely to both the Spanish Fascist Party (also known as Falangism) and the Catholic Church. Partly on the strength of his own tumultuous childhood experiences in an orphanage-like facility, this writer published in 1952 a compact novel with a title that means literally in English Marcelino Bread and Wine. This work has been interpreted as responding to the ideological needs of the Nationalist Catholicism of the Franco regime in Spain at the time. The fiction achieved broad fame in 1954, when it was made into a Spanish-language film, under its original title Marcelino pan y vino (Marcelino bread and wine) and with a screenplay by the novelist. Since then it has lived on in various media.

The novella, along with sequels concerned with the same title character, tells of an orphan in the early twentieth century who as a newborn was forsaken at a Franciscan friary. Grown into a rambunctious rascal, this Marcelino comes into conflict with the friars. Among other things, they warn him not to set foot in the garret, where they claim that a bogeyman lives. True to form, the rapscallion disobeys. In the space above, his blood curdles: it scares the living daylights out of him to see what he takes to be the spook. Because of this and other perceived misconduct, the child is shunned with silence by the monks. During this phase, he returns to the attic and discovers there an image of Jesus on the Cross. When the young rogue delivers the offertory—the bread and wine offered at the Eucharist—Christ comes to life, descends from the crucifix, nibbles and sips the offerings, and begins to catechize Marcelino. Through a chink in the door, the brothers spy on the boy, and witness a miracle. The statue cradles the scamp in its arms and, by allowing him to die, grants the youth his wish to see first his own mother and then Christ. The brethren burst into the top-floor room to see the child shrouded in a heavenly glow. Subsequently Marcelino is buried beneath the monastery chapel and becomes the object of veneration.

Fig. 5.38 Film poster for Marcelino pan y vino, dir. Ladislao Vajda (Filmayer, 1954).

The parallels between Sánchez-Silva’s piece and the juggler story are striking. In both, the setting is an abbey. The hero is a newcomer and nonmember, whose role is to be seen and not heard. He goes apart to a separate realm and altitude within the institution, where he finds a representation. The carving becomes animate. The religious see it come to life. The outsider dies and receives divine favor connected with Mary. The fundamental motif of the novella is an offering made to an image of Christ and the Virgin, here specifically a crust brought by a boy. Sánchez-Silva gives away a scintilla of anxiety as to his originality in the composition, since he professes to have heard its kernel from his mother. The chief motif is attested widely in medieval Latin texts, from the early twelfth century on, and later in vernacular languages. Designated by folklorists as “Food for the Crucifix,” the narrative can be condensed at its most rudimentary to a two-sentence summary: “A pious (or simple) boy offers bread to a statue (or crucifix or image of Christ or the Virgin Mary). As his reward, he is entertained in heaven.”

As in the tales of the little percussionist, littlest angel, and little juggler, the little boy in Sánchez-Silva’s account is at once adorable, in the loose extension of the word, and an adorer in the technical sense. Tellingly, the main difference is that the Marcelino story has as its crux (forgive me) love interrupted and resumed. The yearning for a mother who has passed away is completed and fulfilled through a worship of Christ that leads to the Virgin Mother. The only father figure is the abbot, who is a bystander in comparison with the Madonna.

The narrative of Marcelino Bread and Wine has thrived across the globe, not only among Spanish speakers in both the Old and New Worlds but also in the Philippines and Japan. Thus it has fared well in many cultures in which the juggler has prospered in recent decades in children’s literature—but that is another story. The success of the one does not come at the cost of the other: Marcelino, the little drummer boy, the littlest angel, and the juggler are not pitted against one another in cage fighting with fisticuffs and worse, forced to compete in a narrative “survival of the fittest.”

Folktale or Faketale?

When speaking metaphorically of bread crumbs, we allude—whether knowingly or not—to the second trail that the brother lays down to save his sister and himself in the fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel. The first such line of markers worked: the siblings could follow white pebbles to return safely home from the forest. This other one fails, because birds eat them: the track disappears. In literary scholarship, surviving books and manuscripts are the bright little stones. Bread crumbs are oral versions that may or may not have existed.

From the early days of the tale’s modern reception, the thinking of many writers about its origins has been foggy. Some, for the sake of a good story, have consciously distorted what they knew. Initially, people were led most often into the misapprehension that the medieval French poem was composed by Gautier de Coinci. The extensive verse Miracles of Our Lady by the Benedictine monk and poet has been presented far more than once, incorrectly, as the direct inspiration for Our Lady’s Tumbler. Later, other interpreters took as a given that the audience-friendly narrative must have issued from oral culture. Since the 1940s at the latest, those who write and tell children’s literature have played an old game, sometimes out of deliberate disingenuousness, at other times out of insouciance or ignorance. In any case, they have claimed that the modern traditions of Our Lady’s Tumbler and even of Le jongleur de Notre Dame originated in folktales told and not read. Now and again, authors and readers have advanced such claims despite being well acquainted with centuries of written sources for these accounts. Perhaps they should not be criticized too harshly. Since being recorded in texts, the tales have bobbed back and forth constantly between recorded and unrecorded media and performances. We do not know if Our Lady’s Tumbler gave rise to orality, was born of it, or both. Even the beginnings of Le jongleur de Notre Dame are cloaked in uncertainty: we cannot make definitive pronouncements about what Anatole France perused, heard, and imagined. In the end, the question of the relative weight to assign to written and oral transmission is an unanswerable “the chicken or the egg?”

The liner notes to a recording of John Nesbitt’s “A Christmas Gift: The Story of Our Lady” make boldly optimistic claims about the nature and origins of the narrative, its relative popularity at the time when the radio personality dramatized it, and the kind of fame that it subsequently commanded. For starters, the text hypothesizes that the “old legend” arose in the mid-fifteenth century, ignoring that since the account was transmitted by word of mouth, not much can be stated definitively about its ultimate beginnings. For all that, with a confidence that would have resonated with Gaston Paris, it declares, “It comes from the simple people.” Fast-forward to the mid-twentieth century. Now the folktale has allegedly been forgotten, but Nesbitt digs out of his father’s trunk a supposedly original translation that he adapts. His version is soon followed by the 1942 short film and dozens of renderings in print. Conclusion? “Because thousands of children and grown-ups request it every Christmas season, it will some day be as familiar to our children as The Christmas Carol, or Puss in Boots, or The Little Match Girl.” The assertion may not be a radical misrepresentation. The story seems to have a will to be told. For every great adaptation that threatens to become canonical, scores of other retellings or restagings of one kind or another remain largely unpreserved. Where oral traditions are concerned, the absence of evidence is not necessarily, as the saying goes, evidence of absence. Yet our culture, worrying constantly at the relative priority of speech and writing, requires recording to keep even the unrecorded alive. For most of human history, records have been written.

The cornerstone for transmuting the tale into a folktale was put in place in the early twentieth century, if not earlier. To take one intriguing example, in late 1908, the American modernist poet Wallace Stevens was working and living in New York City. In a letter to his intended during the first month of their engagement, he made no mention of Massenet’s musical drama, which was very much in the air at that moment. Thanks to Oscar Hammerstein, it had just premiered with the much-touted New World innovation of having Mary Garden sing the lead en travesti. Though he made no mention of the opera, Stevens would surely have had reports of it in mind as he recapitulated the story:

Once upon a time there was a beggar who scraped together a living by juggling; and that was all he could do. One day he thought it would be easier for him to become a monk, so he entered a monastery. Being a man of low degree, he knew of no way to worship Our Lady except to juggle before her image. And so, when no one was looking, he did his few tricks and turned a somersault; and thereupon, Our Lady, being much pleased by his simplicity, smiled upon him, as she had never smiled on any monk before.—Now, suppose that, instead of doing his best, he had grieved about his short-comings, and offered only his grief. Would the image have smiled?—And a jig—and a jiggety-jigetty-jig. There is my juggling, my dear—and my somersault. I inscribe a record of it in the last chapter of The Book of Doubts and Fears.

Stevens’s précis reduces the jongleur to a poverty-stricken panhandler, touches equally upon the character’s juggling and tumbling (very much in keeping with the broad range of activities associated with medieval entertainers), emphasizes the man’s simplicity, and suggests an identity between the performer and himself as poet, as well as perhaps between Our Lady and his wife-to-be.

Most arrestingly, the restatement places the story unambiguously within the galaxy of fairy tales. Stevens even opens his text with the words “Once upon a time.” We have seen this same gambit repeatedly in other later versions from throughout Europe and North America. A 1977 American presentation of the narrative in English appears in a collection entitled Once-upon-a-Time Saints: Faith-Tales for Children, which commences unsurprisingly with the formula “once upon a time” every single one of the saints’ lives it contains (see Fig. 5.39), thus localizing the account explicitly in a space between hagiography and fairy tale that it has long occupied implicitly, perhaps even since it was initially recorded in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century.

Fig. 5.39 The juggler. Illustration by Victoria Brzustowicz, 1977. Published in Ethel Marbach, Once-upon-A-Time Saints: Faith-Tales for Children (Cincinnati, OH: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 1977), 60. © Victoria Brzustowicz. All rights reserved.