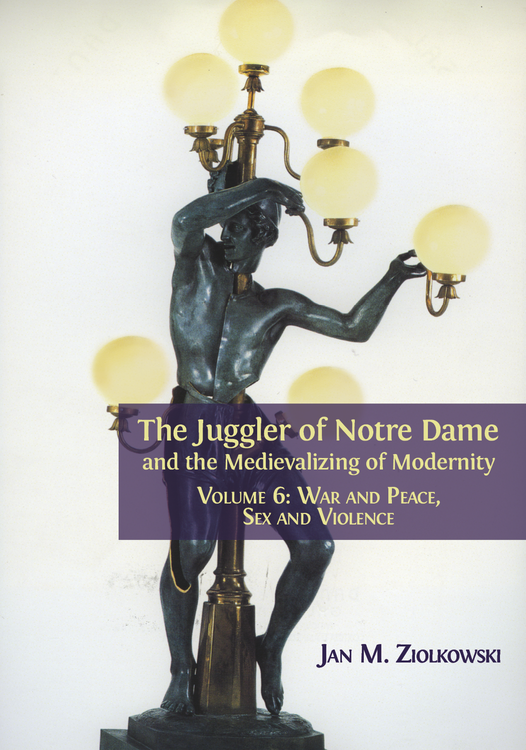

2. The Juggler by Jingoism: Nazis and Their Neighbors

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0149.02

The world becomes more amusing every year. I am always in greater hopes of living to see it break its damn neck, which I calculate must happen by 1932.

Virginal Visions

A not very incisive principle could be formulated: from the early Middle Ages on, in phases of high anxiety Christians have often sought to strengthen their engagement with the Virgin. When sailors batten down the hatches, the faithful fall on their knees before Madonnas. When the political ambience and military events swoop toward apocalypse, Marianism soars to new heights. One tangible token of these tendencies can be wrested from numismatics. Until the Vatican adopted the euro in 2002, it had its own system of coinage which was linked closely to the Italian lira. From 1929 through 1941, the reverse of the one-lira denomination depicted Mary. The design showed the Mother of God with her head encircled by a star-ringed nimbus and her calves framed by the horns of a crescent moon, with the globe beneath her feet as she tramples a serpent (see Fig. 2.1). In 1933, to mark the jubilee commemorating the death of Jesus, the area for signifying the date was enlarged. The years around this one proved to be uniquely important in far more than coins alone.

Fig. 2.1 Virgin Mary on crescent and globe, trampling serpent. One-lira Vatican commemorative coin (reverse), engraved by Aurelio Mistruzzi (1933).

The broad backdrop of Marian devotion and the uneasy atmosphere in the run-up to war all but guaranteed that apparitions would occur, and that they would attract ever more attention from the public. A first symptom of a craving for the immediacy of a sighting, and for the associated promise of mediation, took the form of Mariophanies in the spring of 1931. At Ezquioga, two children and others affirmed that they had caught sight of the Virgin (see Fig. 2.2). The faithful rallied behind the appearances of Mary by flocking on pilgrimage to this hamlet in the Spanish Pyrenees. Overzealous believers even wagered that the microscopic municipality in the mountains might manage to become a new Lourdes (see Fig. 2.3).

Fig. 2.2 “These four Ezquiogans saw the Virgin.” Photograph by Charles Trampus, 1931. Published in Le Miroir du monde 2.78, August 29, 1931, 244.

Fig. 2.3 “Ezquioga sera-t-il un nouveau Lourdes?” Le Miroir du monde 2.78, August 29, 1931, 243.

These visions happened one month after the sacking of a hundred convents and places of worship in Spain. Anticlericalism surged once Cardinal Segura denounced the recently declared Spanish Second Republic. By decrying the regime, this Roman Catholic dignitary drew a line between the left-wing Republicans and the Church. He was sent packing into exile in France.

The flurry of virginal visions in the Pyrenees notwithstanding, the heaviest Marian activity came to pass in multiethnic Belgium. In the early 1930s, Belgian society wobbled and crumpled from the instabilities of its many internal rifts. As one of the most brutally contested killing fields in the First World War, the nation had been badly bludgeoned. During the combat, frictions between French-speaking Walloons and Dutch-speaking Flemings had pressed to the fore over language and culture as well as over might and money. In the interim, such spats had hardly been resolved and dissipated. If anything, they had intensified. The latent became blatant. Like the rest of Europe and the world, this factious land had endured the Great Depression. The economic hardship which dragged out year after year had furthered the political advance of socialists. In a 1931 encyclical, Pope Pius XI took a stand in condemning statist socialism. The stage was set for all sorts of dramatic brushfires: the country was on edge. A turn to the supernatural for reassurance made sense.

Circumstances were no more irenic in the hulking neighbor that loomed to the east of Belgium. Germany was mired in its own not-so-healthful muck of financial and political problems. In 1933, a mustachioed psychopath tightened his tentacles and centralized power in himself. On January 30 of that year, he was appointed chancellor. On August 19 of the next, he was confirmed as sole Führer or “leader” of the nation by a referendum. In the near term, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France would begin receiving displaced persons from the Nazis. Furthermore, Hitler’s favor for Lebensraum, or “living space,” to accommodate a loosely conceived pan-Germanic realm only fanned the flames of rivalries between French and Dutch speakers in Belgium. Under his rule, the German had a strong self-interest in fomenting Flemish nationalism and separatism. For all these reasons and more, many Belgians devoted themselves to the Mother of God, and contracted what verged on an epidemic of Marian visions.

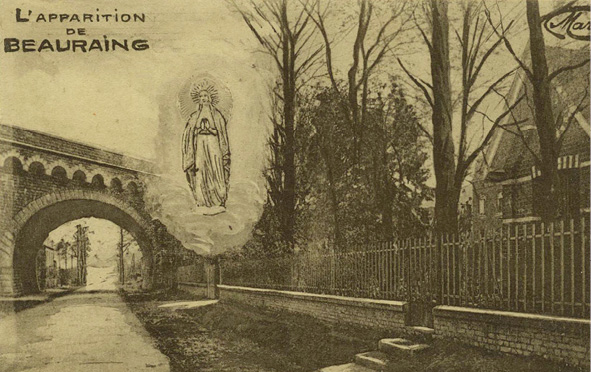

The first of the actual or alleged Belgian epiphanies of Mary transpired in Beauraing, a small Francophone town in the borderland diocese of Namur, just a few miles from the frontier with France. Between late November, 1932, and early January, 1933, five children from two working-class families experienced apparitions of Our Lady. All the visions occurred close to a drab, scaled-down replica of the Lourdes grotto, with a modest-sized plaster statue of the Virgin (see Fig. 2.4). The simulacrum stood near a railroad embankment just beyond the garden of the convent school the youngsters attended. Another landmark in the sightings was a hawthorn tree.

At the outset, the young people spotted a luminous woman in snowy clothing. With her feet shod in puffy little cumulus clouds, she moved aloft above the railway bridge that stood at the top of a gradient not far from the children: she was truly walking on air (see Fig. 2.5). Subsequently they saw her, wearing a white gown and emanating a blue light. More than thirty times, the five espied the Mother of God, communed with her, and received in return a beatific smile and a few instructive words. Mary’s main memoranda to them were pithy and uncomplicated imperatives, such as “Pray always” and “Always be good.” Initially no one put any stock in what the schoolchildren related, but eventually the report of the sightings drew the great unwashed of faithful (see Fig. 2.6). On August 5 of 1933 alone, 150,000 pilgrims or thereabouts descended upon the location. During the first ten months of the shrine’s existence, the total number of visitors to it was tallied at 1,700,000. The wall-to-wall throngs included believers who themselves asserted that they had prospered from miracles, with visions and healings. One of them was the fifty-eight-year-old Tilman Côme (see Fig. 2.7).

Fig. 2.4 Postcard of the replica of the Lourdes grotto in Beauraing, Belgium (Brussels: Ernest Thill, 1930s).

Fig. 2.5 Postcard recreating the apparition in Beauraing, Belgium (Brussels: Marco Marcovici, 1930s).

Fig. 2.6 Postcard of crowd at the hawthorn tree and bridge, locations of the apparition in Beauraing, Belgium (Brussels: Ernest Thill, 1930s).

Fig. 2.7 “The crowd hearing the revelations of Côme Tilman, Beauraing.” A bit left of the middle, bareheaded and facing the camera, the farmworker who experienced a miracle. Photograph, 1930s. Photographer unknown.

A chain reaction took place, in which glimpses of Mary in one place led to subsequent recurrences in another. (Given the involvement of the Mother of God, the cumulative response could be better called a domina than a domino effect.) In the village of Banneux (see Fig. 2.8), between mid-January and early March of 1933, an eleven-year-old girl witnessed eight materializations of the Virgin. In this instance she showed herself clad all in white except for a blue sash, and radiant with light. In this guise she became recognized as the Virgin of the Poor, a title by which she identified herself in one of the showings. News of the visions drew immense concourses. At first, the seer was suspected of having been conditioned in her conception of Mary by having seen a statue of her at Lourdes. For obvious reasons, the young lady was thought to have been affected by the brouhaha at Beauraing. Additional visionaries, or alleged ones, caused some aftershocks, but the validity of their claims was challenged even at the time. As a result, these individuals are scarcely remembered today. A case in point leads us to events that played out in Onkerzele, another small settlement in Belgium. The episode began with Leonie Van den Dyck (see Fig. 2.9). Between August 9 and October 31 of 1933, she purported to catch sight of Our Lady of the Poor thirty-three times. The grim-faced housewife and mother came forth with many predictions. Eventually the Church rejected any supernatural legitimacy in the visions that she was supposed to have had.

Fig. 2.8 Postcard of the site of the apparition in Banneux, Belgium (Brussels: A. Dohmen, ca. 1934).

Fig. 2.9 Postcard of Leonie Van den Dyck, the visionary of Onkerzele, Belgium, outside her home, ca. 1933.

What conclusions may we draw? In 1933, Marian apparitions metastasized throughout Belgium, among both Flemish and Walloons. The epidemiology of their dispersal furnishes ample confirmation that in the stressful atmosphere, believers ached to apprehend the Virgin as a material presence. They hankered to witness the direct intervention of heaven on earth, through the person of the most approachable figure Catholicism could deliver. Although the rash of seeings would not recur, Mary would reappear in an even darker moment. Authors in the Low Countries found faith, solace, or even just parallels in the miracle of the medieval jongleur. Not by coincidence, like their countrymen who experienced Mariophanies, these writers are extraordinary in number and range.

Belgium

—Anonymous saying

The devil is in the detail.

—Anonymous saying

In Belgium and the Netherlands, the tale of Our Lady’s Tumbler was put into Dutch at least three times during the occupation. The pen is said to be mightier than the sword. Whatever truth we assign to the truism, writing can offer a means of striking back against hostile forces. For all that, our story was not invariably a pièce de résistance in the Low Countries. The authors of these three versions inscribe a triangle, to which we may append the translator who was responsible for the only rendering into the language that had been made prior to the war. No one could have dreamed up a paradigm that would better communicate the starkly varying circumstances imposed and choices made under the Germans in these countries from 1940 to 1945.

The sundry translations and adaptations speak to the creativity that can be unleashed amid upheaval. All these Belgian and Dutch writers lived during the years leading up to the Second World War. The societies around them were beset by severe political and economic crises that called into question self-definition, church-state relations, and many other factors. Seen in the rearview mirror, the 1930s have been regarded as a heartwrenching crisis in Flemish and Dutch literature. Conditions in Belgium favored a turn to Mary and to the narrative of Our Lady’s Tumbler. No wonder that people were receptive to manifestations of the Virgin, or that accounts of solace offered by her to individual penitents of humble backgrounds would strike a chord with artists and audiences alike.

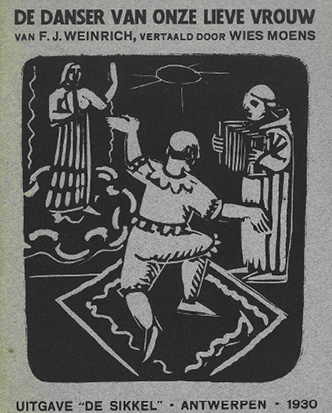

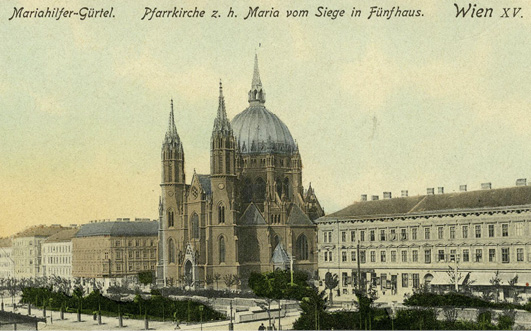

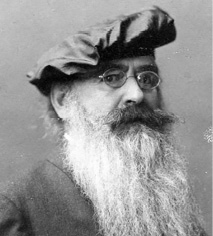

In 1930, Franz Johannes Weinrich’s German expressionist play of 1921 was brought out in Antwerp under the Dutch title meaning Our Lady’s Dancer: A Little Miracle Play (see Fig. 2.10). The translator, Wies Moens, was a Fleming who wrote prolifically in his natal tongue. Already as a young boy, this future poet and journalist was exposed to two of the chief preoccupations that would intertwine erratically in his adulthood. One was Catholicism, thanks to which he evinced an unwavering belief in God and placed a special accent upon the Virgin. The other was Flemish nationalism. Both considerations held the foreground when he attended the College of the Holy Virgin (see Fig. 2.11) in a Belgian city in East Flanders and came into contact there with the Flemish Union. This institution, built in a gritty medievalizing architectural style, puts on show in an alcove over its principal portal a statue of its protectress, Mary.

Fig. 2.10 Front cover of Franz Johannes Weinrich, De danser van Onze Lieve Vrouw: Een klein mirakelspel, trans. Wies Moens, woodcut by Prosper De Troyer (Antwerp, Belgium: De Sikkel, 1930).

Fig. 2.11 Postcard of Het Heilige Maagdcollege, Dendermonde, Belgium (Brussels: Ernest Thill, 1930s).

Ghent remained the central locus of Moens’s activities until the end of the Second World War. During the First World War, he studied Germanic philology in the university there. The city, one of the oldest in Belgium, was rent by social tensions. In it, the young writer had a hand in the Flemish nationalist movement. After the armistice, his activism landed him in detention twice, for much of 1918 to 1921. In the second stint, he spent twenty-two months in a prison cell, until spring of 1921. As a Dutch-speaking Fleming, he belonged to a population linguistically and culturally estranged from the French-speaking Walloons. His faction saw the so-called Flemish question as “a conflict of two civilizations, based on two different languages.” In consequence, the group sought for the German occupiers to resolve the issue so that the Flemish could gain the upper hand by establishing a discrete Great Netherlands. This nation of Dutch speakers, known as Dietsland, would ingest not only the Netherlands and Flanders but also the Afrikaans-speaking portion of South Africa.

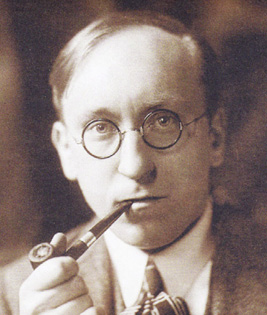

Politics is just part of the picture. Ghent, birthplace of the Belgian Nobelist Maurice Maeterlinck, saw vibrant intellectual and artistic experimentation. How much that extends to writing in Dutch remains indeterminate. During the two decades between World Wars, Moens (see Fig. 2.12) stands among his Flemish peers as an isolated and halfhearted advocate for modernism. More specifically, he could be considered a disciple of avant-gardism. In fact, he has a claim to literary-historical significance chiefly in this role. While imprisoned, he composed a booklet of expressionist poetry. The Fleming’s absorption in this style of verse led him naturally to Weinrich’s play, and he translated it faithfully into his native tongue not even ten years after its first edition. The German’s drama innovates on earlier forms of Our Lady’s Tumbler by having the dancer execute a progression of steps as he wrestles with his doubts over his calling to take monastic vows. The first is fleshly dance; the second, a mystical ascent to Mary; and the third, an outpouring of spiritual exultation that proves to be the monk-dancer’s supreme effort before his death, after which he strings out perpetually his balletic career in the firmament as a star right next to Mary. In the later translation, the play pealed a note that resonated with the tastes of the times. The expressionism allows for actors and dancers to convey emotion through their acting, including their movements, far beyond the restraints of the uncomplicated words. The piece was soon appropriated for production by school and amateur groups in Belgium.

Fig. 2.12 Wies Moens. Photograph taken before 1926, photographer unknown.

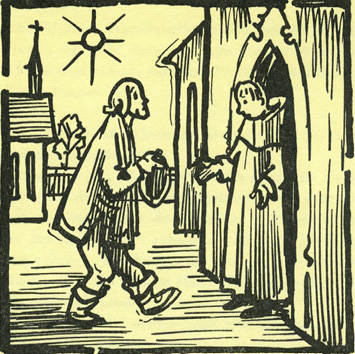

Prosper De Troyer (see Fig. 2.13), the Fleming who engraved the woodblock that embellishes the book jacket to Moens’s translation of the play, is also a certified expressionist. The writer and he crossed paths in other collaborative projects during the early twenties. Like Moens, the artist for a spell synthesized expressionism with his Catholicism, and he has a reputation for religious themes. Graphic art in the new style constituted such a broad and well-balanced movement that generalization about it can be perilous. In many places, it was conditioned by the putative primitivism and primal vitality of African and Oceanic art, complemented by the work of Gauguin and Van Gogh, as well as by medieval woodcuts. Such medievalesque influence can be detected here in De Troyer’s cover. The carving has an anguished blackness that is even harshened by the underlying grayness of the cardboard. The composition brings angular lines into stark juxtaposition, with the dancer’s square mat set sideward to the oblong frame of the whole artwork. We make out only the back of the man doing his steps, with his tonsure and his medieval entertainer’s garb. Up to the left, the apparition of the Virgin hovers. To the right, a monk in his habit carries between his hands what could be a stack of books or an accordion.

Fig. 2.13 Prosper De Troyer, self-portrait, 1929. From Frans Mertens, Prosper De Troyer (Antwerp, Belgium: Standaard, 1943), front cover.

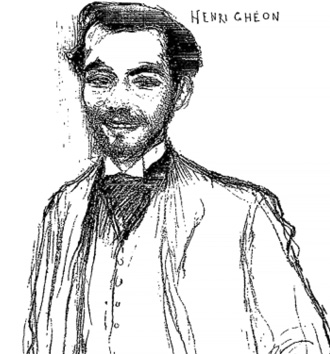

Fig. 2.14 Henri Ghéon. Drawing by Jean Veber, 1898, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henri_Ghéon_by_Jean_Veber.jpg

Moens viewed his generation as nurturing an entirely new and more positive outlook on medieval culture than had been endemic in the nineteenth century. He also pointed to the agency of expressionism. In conclusion, he singled out for special attention Henri Ghéon (see Fig. 2.14) and his Play of Saint Bernard. This French-language playwright was a lifelong devotee of the Virgin. He founded for young folks the “Companions of Our Lady,” an amateur theater group for which he composed more than sixty plays. For content, he usually drew upon the Gospels and saints’ lives, while for style he relied upon medieval mystery and miracle plays. His prolific corpus includes such titles, to give them in English, as Mary, Mother of God and The Madonna in Art. It also assimilates works on other holy men and women who were themselves pledged to the Virgin, such as The Marvelous History of St. Bernard, The Secret of Saint John Bosco, and The Truth about Thérèse.

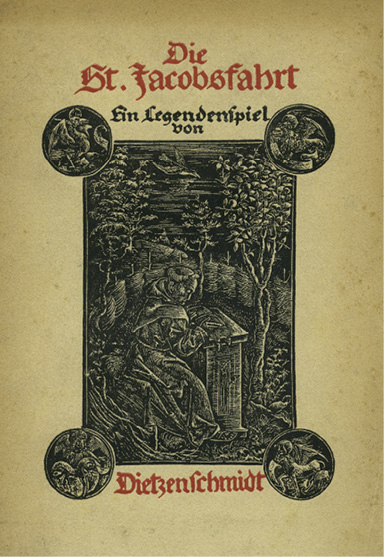

Moens’s attraction to medieval legends propelled him in 1923 to fashion the authorized Dutch rendering of a three-act German “legend play” on the pilgrimage to Compostela. The original-language edition from 1920 could not have placed less emphasis on the movement of pilgrims. Its cover art incorporated a 1520 woodcut that displayed a monk seated at a writing desk (see Fig. 2.15).

Fig. 2.15 Front cover of Dietzenschmidt [Anton Franz Schmid], Die Sanct Jacobsfahrt: Eyn Legendenspiel in drey Aufzügen (Berlin: Oesterheld, 1920). Woodcut by Johannes Othmar, 1920.

Additional impetus to translate Our Lady’s Dancer could have come through G. K. Chesterton’s St. Francis, which dealt in passing with the story of the tumbler, and which Moens put into his own first language in 1924. In the same year in which his translation of the German play appeared, the author published his Dutch version of an English volume on Saint Francis. At the same moment, he became a driving force behind the establishment of the Flemish Popular Theater by a cohort of Catholic theater producers and other movers and shakers. A further factor that may have lent gravitas to the notion of translating the German Our Lady’s Dancer into his native tongue is the relationship between the tumbler and the Church. Until the end of the War, Moens propounded the view that the Flemish people could avert crisis by heeding the direction of its intellectual elite. Accordingly, the performer’s ultimate obedience to the hierarchy embodied in the abbot may have resonated well with his thinking.

Our Lady’s Tumbler has embedded within it a folkishness that could have coaxed attention from an essayist who belonged to a cadre known as Volks-Dietsers. “Folk-Dutchers” would be an indelicately literal way of putting this untranslatable word into English. Moens’s own credibility as a folk-oriented writer is faultless. Indeed, his verse has been characterized as “folk-connected” (volksverbonden). A few years later he would even write a study entitled Dutch Literature Viewed from a Folk Perspective. The purportedly Picardian provenance of the medieval poem would have fortified the tale’s relevance to the modern Flemish author. Even though the original was in a French dialect and not his mother tongue, the story still qualified as at least loosely regional. Finally, his reactions would have been colored by grappling closely with the narrative in a German-language form, in the play by Weinrich.

Moens’s writerly activities are only one tranche of the context that screams out for scrutiny. The year after publishing his Dutch Our Lady’s Dancer, he cofounded the National Socialist party of Belgium, the first full-fledged redirection of nationalism in Flanders toward fascism. With the involvement of the Nazis, the Flemish Question intersected eventually with the Jewish one. Although the author drifted from the Belgian movement not too long afterward, his efforts on behalf of extremists sympathetic to Nazism did not go unremarked and uncompensated later by the invaders—or unpunished when in turn the Germans were beaten down.

After the appropriation of Belgium by Germany, from 1941 to 1943 Moens directed the Flemish radio broadcasting operation instituted by Hitler’s regime. During this same period, he published The Flemish War Poem, in an edition with the Dutch original and a German translation on facing pages. After the deathmatch between the Allies and the Axis drew to an end, he fell into a disfavor that went beyond being persona non grata: in 1947, he was condemned in absentia to execution for having consorted with the enemy. At that juncture, he took flight to the Netherlands. Instead of being extradited to Belgium, he found safe harbor there for three and a half decades as a teacher and administrator at a Carmelite college in Limburg. He died in 1982.

Whether the sentence was condign or not remains an open question. So too does the degree to which Moens deserves responsibility for the atrocities of Nazism in Belgium. Seventy-five years have flown by. Whatever verdict we reach on his connivance and culpability, the outcome he desired from his political activities was not the one exemplified in the German anthem “Germany above all.” Rather, his ambition could be expressed in unwieldy English as “Dutchland above all.” He espoused an ethnic nationalism that aspired to consolidate Flanders, the Netherlands, and other Dutch-speaking pockets, so that a greater Dutchland or Greater Netherlands might arise. This mirage of an emergent nation became befouled by collaboration with the Nazis. In both the First and Second World Wars, the Germans exploited the Flemish Movement to inflate their own supremacy. This writer’s fate serves as another useful caution about the care to be shown in choosing causes and even more in picking allies. Regarding the enemies of enemies as friends requires being steeled to accept or at least tolerate their guiding principles—and standing ready to face the fallout for treason.

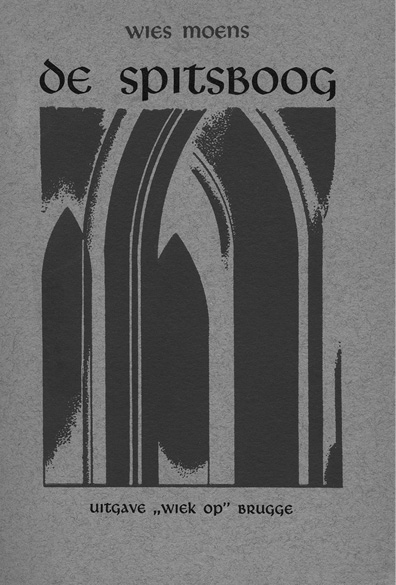

Was Moens’s turn to the Middle Ages in the 1920s related somehow to his eventual descent into philo-Nazi Flemish nationalism and national socialism? The cover of his 1943 book The Pointed Arch offers a stylized view of lancets (see Fig. 2.16). The one in the foreground has a robustness that could be termed “muscular Gothic,” on the model of “muscular Christianity.” The dark-shadowed interiors of the invisible arches behind it obtrude joylessly, like the tips of bombs, torpedoes, or missiles. In one sense, the look marks an outgrowth of expressionism. Set in the context of the last few years of the war, it has a scowling air, with a potency reminiscent of the all too vigorous people and buildings familiar from the propagandizing of Nazism, Fascism, and Soviet Communism. Think socialist realism.

Fig. 2.16 Front cover of Wies Moens, De spitsboog (Bruges, Belgium: Wiek op, 1943).

The popularity, and even special status, of Our Lady’s Tumbler in Belgium was not restricted to Flanders and especially nationalist fanatics there. For example, Arthur Masson (see Fig. 2.17) was a Walloon author recognized for a cycle of five novels in French known affectionately as the “Toinade,” a neologism constructed to honor the likable personality of their protagonist, Toine Culot. In reminiscences, Masson recalled having been introduced to the story of the entertainer in the context of literature from more than a half millennium earlier, specifically fabliaux. He concluded the same piece by characterizing himself as “troubadour of the good days, bard of the humble beauties of my country, jongleur of the Walloon region.”

Fig. 2.17 Arthur Masson in his student quarters in Louvain. Photograph, 1919. Photographer unknown.

Interestingly, the medieval French tale achieved its greatest success in Belgium, but not in the modern reflex of its original tongue. Instead, it spread riotously in Dutch—or Flemish, as the strain of that language spoken in the northern part of Belgium is often called. In November, 1933, a censor of the Roman Catholic Church in Bruges officially approved publication of Wintze, or Our Lady’s Tumbler: Legendary Account (see Fig. 2.18). The name assigned to the leading character is unusual, with a suffix uncommon in Dutch personal names. In fanciful onomastics, the author puns on its elements with the phrase “Wintze wint Ze”: Wintze wins you over—and not just by default.

The writer was E. H. Blondeel, a Fleming who resided in Mont-Saint-Guibert. This community, in Walloon Brabant, is located not far from both Beauraing and Banneux, and thus in the lands where Mariophanies were nearly as common as Madonnas for a few years in the early 1930s. This author published nothing else of substance. His tale makes no mention of the apparitions that occurred nearby as his book was being written and printed. Hence, we are not positioned to infer whether in composing his narrative he was inspired by them, or whether he was moved merely by the same anxious context. Two of our only major certainties are that he was a practicing Catholic and a teacher at a religious school. A third is that in 1929, the writer directed dramatic performances of Our Lady’s Tumbler that the charitable St. Vincent Society in Ypres organized to raise funds for Flemings who went homeless. He is identified as having been a chaplain for Flemish workers in France. Apparently, Blondeel had already staged the play in various other towns in Flanders before then. The staging took place beneath the speechless smile of “the mother in white and blue, Our Dear Lady of Mercy.”

Fig. 2.18 Front cover of E. H. Blondeel, Wintze, of De Tuimelaar van O. L. Vrouw: Legendeverhaal (Torhout, Belgium: Becelaere, 1933).

The Netherlands

Also in 1933, August Defresne (see Fig. 2.19) published a remake of the story, under the Dutch title that corresponds to the English The Pious Minstrel. A playwright, director, leader of theatrical companies, and fiction writer, he showed an interest early in the literature of the Middle Ages. For example, he wrote a 1920 study on the psychology of the Dutch narrative cycle about Reynard the Fox. His engrossment in the human mind accorded loosely with his attraction to expressionism. In 1925, he published a study on the movement in modern German drama. Either in the original or in Moens’s translation, this other Dutch man of letters would surely have encountered the play by Weinrich on Our Lady’s Tumbler. Still, the standard biography of this dramatist’s theatrical activities makes no mention of any other Dutch-language author who wrote a narrative or stage form of the story. From 1923 through 1956, Defresne was affiliated continuously with one or another theatrical company. The sole exception came during the wartime years. During that stretch, he refused to join a Chamber of Culture instituted by the Germans. Consequently, he had a gun held to his head (all but literally) to go into hiding.

Defresne’s version of Our Lady’s Tumbler is not a theatrical script. All the same, the photographic image that once graced the outer cover shows a woman in stylized monastic habit, almost like a glorified gown of the sort worn at American graduation ceremonies (see Fig. 2.20). Her eyes gaze upward, heavenward. Her hands are upraised and pressed against a bare gray background. Blackness billows from stage right, and shadows shoot out from her silhouette. The vignette bottles expressionism in its purest distillation, and it may even afford us insight into the lost German silent films of the story. In a decidedly different direction, the decision to cast the jongleur as a female here is due to the convention that welled up from the dissonant traditions connected with Mary Garden. On the back of the title page the author stipulated that no one but Charlotte Köhler might recite his version of the medieval account. This is the actor he married in 1920.

Fig. 2.19 August Defresne. Photograph by Hanna Elkan, 1940.

Fig. 2.20 Charlotte Köhler as jongleur, in monastic habit. Photograph by Godfried de Groot, ca. 1933. Published on the front cover of August Defresne, De vrome speelman (Amsterdam: “De Gulden Ster,” 1933).

In his introduction, Defresne reviews the constitutive facts about Our Lady’s Tumbler and its reception through Massenet. He observes “this medieval tale is as famed in French literature as Sister Beatrice is in Dutch.” With great chronological precision, he situates the action in 1215. His reworking of the story departs from the original, especially because he “fantasizes” about what happened after the episode recounted in the miracle from the Middle Ages ended. In expanding the narrative, he sought inspiration in the mysticism of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

In 1934, yet another version was reprinted in Dutch. Under the pseudonym of Anthonie Donker, N. A. Donkersloot, at that point in his early thirties, published a collection of poetry entitled Broken Light. The fourteen-line poem bears the title that calls to mind Anatole France and Jules Massenet from decades earlier, rather than visions of Mary in Belgium of his own day. In fact, Donker had published the poem already in 1928.

Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame

Before the Mother of God with the Child, in the grey niche,

he entered, quick as a church thief,

without saying a Hail Mary, without making the sign of the cross,

but juggling with glittering balls,

maneuvering in limber somersaults,

and then clasped his legs, as quick as lightning,

around his neck (the Chinese bridge),

humbly performed his most difficult stunts,

and finally went all out,

and immobile, without trembling for a moment

in his painful, taut wrists,

stood minutes long on his hands,

a prayer stretched motionlessly.

The first version of the tumbler’s tale in Dutch during actual wartime preserved a story at variance with that of Moens, in several ways. It was a translation not of a twentieth-century German text but of the medieval French poem itself. Furthermore, the prose in the modern language issued from the pen of not a Fleming but a Dutch man of letters—and a Jew.

In his early twenties Victor Emanuel van Vriesland (see Fig. 2.21) had already come up against the contrast between the fun-loving tomfoolery of peacetime and the black-hearted soberness of wartime. As a student at the University of Dijon he had joined his classmates in donning a costume as a Pierrot, a sad clown (see Fig. 2.22). With the outbreak of the First World War, he soon had to curtail his studies to come back home. Owing to the hostilities, the frivolity of college life ended prematurely for him.

Fig. 2.21 Victor Emanuel van Vriesland, age 70. Photograph by Jacob de Nijs, 1962, CC BY-SA 3.0. The Hague, Nationaal Archief, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Victor_van_Vriesland_(1962).jpg

Fig. 2.22 Victor Emanuel van Vriesland as a sad clown (top left), age 22. Photograph, 1914. Photographer unknown.

The Dutch Jew was well acquainted with the writings of Defresne. In fact, he even supplied the introduction to the latter’s 1931 novella The Restaurant. During the occupation, Defresne lent a hand in in the Resistance. The story of the tumbler had drawn notice for mixed reasons in both Flemish Belgium and the Netherlands in the early 1930s. Partly it attracted note as a late avatar of expressionism in Germany. Equally, it responded to the Marianism connected with the apparitions of Beauraing and Banneux in Belgium. After the German invasion the tale gathered in renewed attention for different motives again, but from individuals who had been exposed to its earlier popularity.

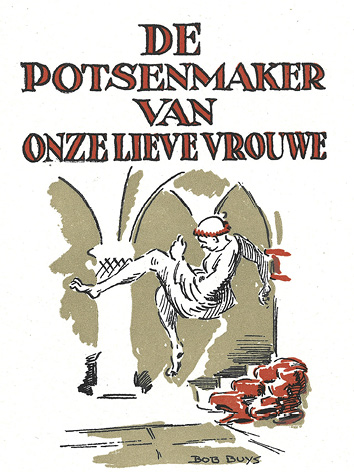

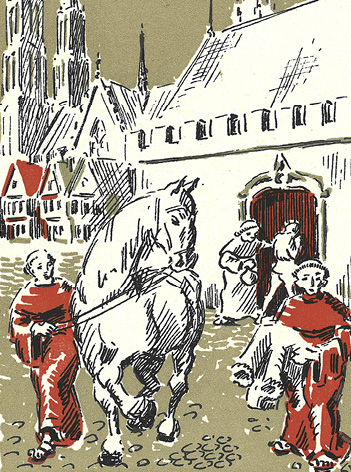

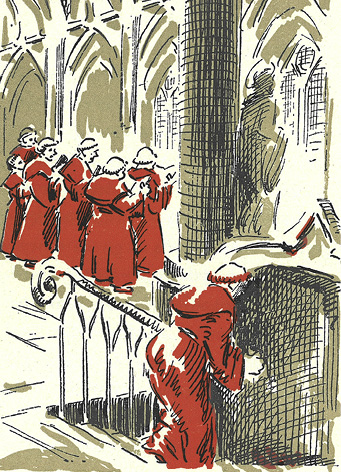

Vriesland’s version was printed in 1941. The illustration on the title page underlines the joyous self-expression of the dancer, to the exclusion even of the Virgin (see Fig. 2.23). Another vignette brings home the humility of the scantily clad tumbler, whom we see only from the rear as he enters the monastery (see Fig. 2.24). The scene focuses close-in on the worldly accoutrements he has relinquished. His horse is led away, alongside a monk who totes the sumptuous garments the minstrel has renounced. A third figure shows the performer, now a lay brother, again from behind. This time he looks identical in habit and tonsure to the choir brothers as they muster with their psalters, except that he is ducking down to skulk into the crypt (see Fig. 2.25).

Fig. 2.23 Title page of Victor Emanuel van Vriesland, trans., De potsenmaker van Onze Lieve Vrouwe, illus. Bob Buys, De Uilenreeks, vol. 44 (Amsterdam: Bigot en Van Rossum, 1941).

Fig. 2.24 The juggler enters the monastery. Illustration by Bob Buys, 1941. Published in Victor Emanuel van Vriesland, trans., De potsenmaker van Onze Lieve Vrouwe, illus. Bob Buys, De Uilenreeks, vol. 44 (Amsterdam: Bigot en Van Rossum, 1941), 6.

Fig. 2.25 The juggler slips down into the crypt during prayer. Illustration by Bob Buys, 1941. Published in Victor Emanuel van Vriesland, trans., De potsenmaker van Onze Lieve Vrouwe, illus. Bob Buys, De Uilenreeks, vol. 44 (Amsterdam: Bigot en Van Rossum, 1941), 42.

The book wraps up with a note that offers scholarly orientation, since the author sticks closely to the medieval original. The world seemed tremendously parlous when Vriesland plied his pen across paper. In keeping with this fragility, the closing passage in the two pages emphasizes the tenuous transmission of the French text from the Middle Ages. Thanks to unwitting overstatement, we are apprised of a single, badly damaged manuscript. At least fourteen folios and most of its miniatures have gone missing during the past few centuries. After the war, the story writer stressed how artists had played a role in the Resistance. He could well have regarded both the jongleur and himself in this light at the instant when the poem first began to ensnare him.

The translator, illustrator, and printer are identified only in a colophon at the very end of the volume. This arrangement may give voice to an unpretentiousness that sits well with the thirteenth-century miracle, which is anonymous: whether by coincidence or design, the story is allowed to speak for itself. Alternatively, the minimizing of identities could have been self-protective discretion. Vriesland had ample incentive not to advertise his biodata. Although he had never made an issue of his background, he was indeed a Jew. Had the German authorities become aware of his ancestry, he would have faced all the travails that being Jewish entailed in the Netherlands under Nazi occupation. To make matters worse, he had been at one time a self-declared Zionist. Neither item in his dossier, Jewishness or Zionism, would have eluded detection by the Nazis. When the Jewry of the Netherlands began to be rounded up for deportation and mass execution, the man of letters had to go to ground. He spent the war years shuttling from one address to another with the help of bosom buddies and the Resistance. Although he evaded capture, his safety and survival were not at all assured. The goon squads of Germans and Dutch Nazis managed to track down between a third and half of the Jews in the country who went into hiding. Those they apprehended, they dispatched to camps and death. Socially isolated from hiding and psychologically pressured from worrying, Vriesland sunk into despondency.

The fugitive could have teased out parallels between the tumbler and himself. The medieval entertainer forsook his belongings and clothing, retired from the world to live a cloistered existence, and took on a powerful institution that seemed unsympathetic and uncaring to both him and his craft. The dancer of the Middle Ages, long before the concept of nonviolent resistance had been created, cordoned off a space and function of his own without confronting his institution directly. Similarly, the juggler of the Anatole France story goes unwittingly against the government of his organization. He resists by practicing his art. Even while wheeling physically or verbally, the two protagonists balk at being mere cogs in the social machinery they inhabit. A harried Jewish artist consigned to a living death in a country occupied by the Third Reich had good cause to identify with a protagonist who could express himself only surreptitiously.

Going farther out on a limb, we should consider the claustrophobia of a confined existence as compounded by the sequestered aloneness of the out-of-place lay brother. The gymnast spends most of his waking hours trying to breathe unbreathable air as he is cooped up in a stuffy space far from the light of day. Being in a crypt differed comparatively little from being walled off from society and secret police, as were most famously in Amsterdam Anne Frank and her Jewish family. Some hiding places of Jews who went underground to become involuntary shut-ins were in fact truly subterranean, oubliettes entered and exited through trapdoors. In addition, the Dutch word for going into hiding (onderduiken) means literally “to submerge”—to go under water. To speculate further, the term in the same language for the Shoah (ondergang), if broken down into its two constituents, corresponds to the English “going under.”

The medieval poem portrays an artist cut off and excluded, from both the outside world he quits and the inside clique he joins. He is a loner in the pursuit of his art, and he dies partly through the practice of it. Yet the message and spirit of Our Lady’s Tumbler are not defeatist. Without being triumphalist, the poem is nonetheless triumphant. Without knowingly trying, the gymnast or dancer vindicates himself against both the macrocosm of secularism and the microcosm of monasticism. He attains salvation through his commitment to his craft, even though he must rehearse it in windowless, lightless, and airless isolation. Vriesland may have been lured by the counterintuitively victorious spirit, which is uplifting in a very real sense. First the performer is assuaged when he is down, and then post mortem he is hoisted aloft to heaven by angels who levitate themselves and him at Mary’s behest.

A final thought is that the Dutch Jew may have felt a rapport with the story out of appreciation for Christians who succored him in his time of need. More generally, Vriesland may have been fascinated by it as an expression of ecumenism. In this regard he can be compared with the German-language author Franz Werfel, who was Austrian-Bohemian by birth, but Jewish in ancestry. Werfel was exposed to Czech Catholicism through his governess and through the schools in which he was educated. After the 1938 annexation of Austria by the German Nazis, he fled his homeland. His flight took him to France. In the closing days of June, 1940, after the German invasion, Werfel and his wife found themselves among millions of evacuees in southern France. The couple was advised by one family to seek shelter in the major town of Lourdes, in the foothills of the French Pyrenees. The two received sanctuary in this so-called City of Miracles. After visiting the heralded holy place, the writer vowed to give an accounting of the spiritual serenity, and the kindness from the Catholic keepers of the shrine, that he experienced there.

Once Werfel gained asylum in America, he delivered on his pledge. In 1941 he published in German the historical novel The Song of Bernadette, which deals with the vision of the Virgin seen at Lourdes by the young woman from the Soubirous family. The “personal preface” to the book concludes with a paragraph in which the author explains movingly why despite religious difference he was impelled to set pen to paper by one goal:

… that I would evermore and everywhere in all I wrote magnify the divine mystery and the holiness of man—careless of a period which has turned away with scorn and rage and indifference from these ultimate values of our mortal lot.

The émigré wrote about Saint Bernadette, not about the jongleur—but his ultimate faith in the sanctity of man resembles the spirit that has moved many, or even most, of those writers and artists who have engaged over the centuries with the story of the medieval devotee of Mary.

After World War II, Vriesland ascended to preeminence in the literary firmament of the Netherlands. Simultaneously, he maintained his commitment to the belletristic culture of France. He translated from French, especially poems and essays of Paul Valéry, and left a bumper crop of verse in the same language. The Dutch writer is likely to have been drawn to the medieval French piece of poetry about the tumbler by way of Anatole France, with whose writings he was au courant. There even survives from his hand an autographed copy of a speech that Anatole France declaimed at the burial of the French naturalist writer Émile Zola at Montmartre in 1902, as well as abundant correspondence with the Anatole France Society.

However noteworthy his French retelling may be, Vriesland was even more prolific and varied in Dutch. Although he may have left his deepest mark by compiling a three-volume poetic anthology in his native language, he also wrote a novel, short stories, plays, poems, literary essays, and other journalism. Yet even amid this heterogeneous and eclectic outpouring, his prose of the tumbler’s tale looks curiously out of place, making it all the more probable that his pick of material was dictated by the special strains of the German occupation.

Later came a bit of writing by another verse-maker, so freely rendered from the medieval narrative that its hero is accorded the name Reinoud, not until then assigned to him in any foregoing version. By Gabriël Wijnand Smit (see Fig. 2.26), the composition was printed by itself in an undated publication, perhaps also from 1941.

Fig. 2.26 Gabriël Smit, age 42. Photograph, 1952. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Katholiek Documentatie Centrum, Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen, Netherlands. All rights reserved.

This poet, journalist, and essayist fraternized at first with a group of Protestant writers, but in 1933 he enrolled in the Roman Catholic community. His translation may have been welcomed with open arms, since it was reprinted four years later to cap a collection of seven miracles of the Virgin. In a closing note to the later volume, Smit points out that the first six of the legends had Dutch origins. In contrast, he describes the story of the tumbler as a repurposing of what he calls “a very Old French legend.” In the same text he also underscores that in his rendering he has not sought to cling to the original verbatim, but rather to enable the quintessence of this priceless narrative to spring to life for a present-day reader. The later book was embellished by Cuno van den Steene (see Fig. 2.27), an artist and illustrator in the Netherlands. The volume was designed by a printer with whom Smit had coedited a magazine put out by the printing house in 1939 and 1940. The title of the periodical, In the Light, would presumably have referred both generally to the beacon of faith and more particularly to the light at the end of the tunnel of war.

Fig. 2.27 A monk discovers the juggler’s performance. Illustration by Cuno van den Steene, 1945. Published in Gabriël Smit, Zeven Marialegenden (Utrecht, Netherlands: Spectrum, 1944), 80.

Smit’s circumstances differed sharply from Vriesland’s. Most notably, the Catholic writer found common ground now and again with claques under the sway of the Nazi occupation. In 1942, he was a featured speaker in cultural radio programs run by Netherlands Broadcasting, which was controlled heavily by the Germans and used by them in their efforts to Germanize and Nazify the occupied nation. Thereafter he participated actively in the Netherlands Chamber of Culture. As with Defresne, this agency required all writers, musicians, and other artists to be approved and to register, or else risk penalty. Smit has been vilified for the opportunism of taking both sides during the war. For all that, it is hard to size up how fully he, as opposed for example to Moens, embraced the policies of the occupiers. Was Smit a turncoat or not?

Throughout his writings, Smit gave utterance to a visceral yearning for the unmediated presence of God. Even before the war he addressed himself to religious topics (see Fig. 2.28). Nor did he scrap such subjects once peace had been rehabilitated and fences mended, as is confirmed by a compilation entitled Psalms. His faith may have given him strength, yet the hostilities weighed heavily on the poet all the same. His soul suffered from living under the Germans. His preoccupation may be gauged from a postbellum compendium of his, entitled In Wartime. During the occupation, he turned specifically to the Virgin for solace and support. His special reliance on her is borne out by the title of his 1939 verse miscellany, Praise of Mary and Other Poems.

Fig. 2.28 Caricatures of Gabriël Smit, with note indicating that originally he belonged to the Old Catholic Church. Drawings by M. J. H. M. Wertenbroek, 1936. Image courtesy of Katholiek Documentatie Centrum, Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen, Netherlands. All rights reserved.

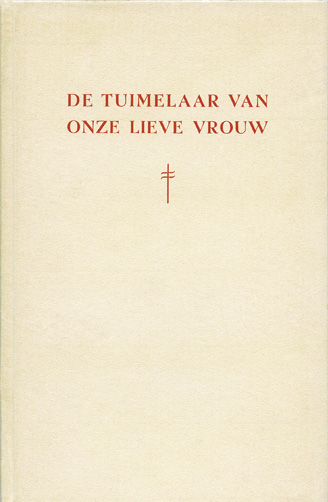

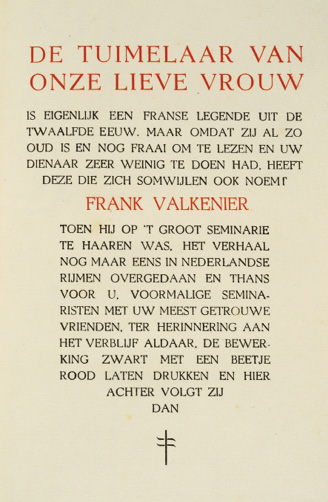

Frans van der Ven published his poetry under the pen name of Frank Valkenier. In 1944, he brought out under this pseudonym a private edition of The Tumbler … A French Legend from the Twelfth Century. The minuscule book was printed in Tilburg. It belongs to the high tide of clandestine literature that rolled over the Netherlands under the Nazis—far more for the size of the country than in any other occupied nation. This version puts the medieval French poem into Dutch rhyming verse. The cover (see Fig. 2.29) signals the poet’s politics, since it bears the Cross of Lorraine. As in France, this mark symbolizes the Resistance.

The title page (see Fig. 2.30), deliberately creaky in its construction, rubricates the name of the work and the author’s nom de plume. Beyond such basic facts, it provides much additional information in conventional black ink:

The Tumbler of Our Lady is strictly speaking a French legend from the twelfth century. But because it is so old and still attractive to read, and your servant had very little to do, the one who sometimes also calls himself Frank Valkenier translated the tale one more time into Dutch rhymes when he was at the Major Seminary at Haaren and has had the revision (black with a little bit of red) printed now for you former seminarians with your trustiest friends, as a remembrance of the stay there, and it [the tale] then follows after this.

Fig. 2.29 Front cover of Frank Valkenier [Frans van der Ven], De tuimelaar van Onze Lieve Vrouw (Tilburg, Netherlands: Private printing, 1944).

Fig. 2.30 Title page of Frank Valkenier [Frans van der Ven], De tuimelaar van Onze Lieve Vrouw (Tilburg, Netherlands: Private printing, 1944).

Fig. 2.31 Grootseminarie Haaren. Photograph, ca. 1942–1955. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum. All rights reserved.

The outlook beyond this opening seems nothing if not sunny, until we become conscious of the fact that the place under discussion was officially Camp Haaren, a German-run prison and interrogation unit overseen by the dreaded Nazi paramilitary organization known as the SS. Peeking at the towering, Romanesque revival edifice in a photograph from the period (see Fig. 2.31), one can perceive easily why prisoners confined in the commandeered theological institution would have identified with a lay brother. Wish-fulfillment would have come into play in picturing how he slipped away from compulsory group activities to voice his heartfelt beliefs and desires. The fellow seminarians would be those who were detained along with him, most of them in the Resistance. Could the “black with a little bit of red” refer not only to the lightly rubricated printing but also to the results of beatings that left victims bloodied as well as black and blue—or does this amount to overinterpretation in the first degree?

Van der Ven’s first poem was printed in 1936. In that same year, he released satiric verse against Anton Mussert, a founder of the National Socialist movement in the Netherlands. This boldfaced derision, ill-judged in retrospect, led to the poet’s internment by the Nazi occupiers five years later, when the power of the ideologue he had mocked had attained its acme under the Germans. After another five years passed, Mussert himself faced the muzzles of a firing squad in the wake of the Allied victory. The satire is not par for the course in Van der Ven’s oeuvre during this period. Some of his poetry, reflecting his Catholicism, is religious, while a share is devoted to his home district of North Brabant. In 1935, he cofounded Brabantia Nostra, Latin for “Our Brabant.” He brought out his verse for the first time in this journal, came soon to be held in the highest estimation as a poet of the cultural and political reawakening in the territory, and eventually became the big fish in a small pond by being dubbed “the herald of Brabant.”

The Brabantine periodical was produced by a corps of conservative young men between twenty-five and thirty years old. They were inspired by Toward a Catholic Order, a tract published in 1934 by the devoutly faithful Étienne Gilson, a French philosopher who throughout his distinguished career worked extensively on topics pertaining to medieval philosophy and religion. By and large the two causes of religion and regionalism are interrelated: Catholicism and Brabantism commingle. Van der Ven wished to shelter the local color of his native region from the threat of industrialization encroaching from Holland. The cultural distinctiveness encompassed the zone’s characteristic adherence to the Church—and its Gothic architecture. Thus the movement that pinnacled in the journal is related to the devotion evident in the Brabant student guild of Our Dear Lady. Both commitments, to traditional preindustrialism and to the Roman Catholic faith, would have fostered nostalgia for the Middle Ages as a golden age for the territory. This pattern has been familiar since romanticism.

Brabantia Nostra championed the idea that the province was “becoming once again visibly the core of the Netherlands.” Such renewal carried within it an implicit reference to the sector’s medieval heyday. The boosters of Brabantine pride undertook to dig out old traditions. If unable to rediscover them, they stood ready to invent them. The faction comprised elements congenial to the philosophy of the Greater Netherlands. It envisioned Belgium and what English-speakers call Holland as being two moieties of a nation that had been sundered only by an accident of history. In effect the pair was not separate countries, but merely slightly different latitudes of the same entity: North and South Netherlands.

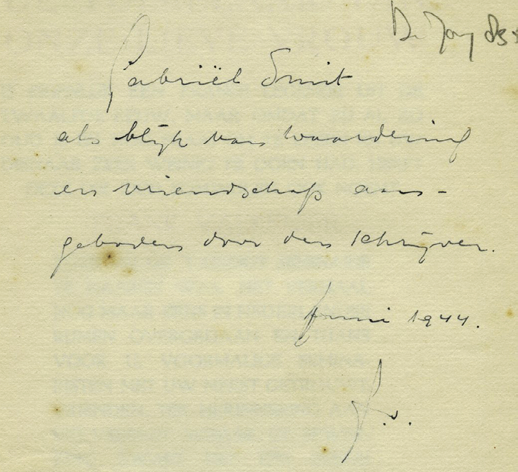

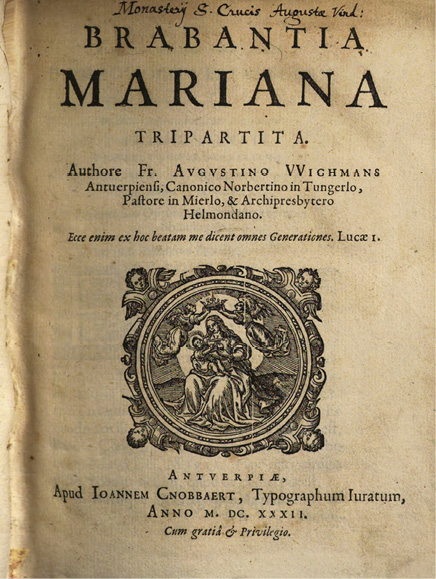

Catholicism may have formed the great common bond between Van der Ven and Gabriël Smit. The first dedicated a copy of his tumbler translation to the second (see Fig. 2.32), with the inscription “As a token of appreciation offered by the writer in friendship.” The momentous position that the Virgin has filled in Catholic religion helps to explain why both authors were captivated by the medieval miracle story that involved her. The journal Brabantia Nostra had a noteworthy religious component, and a singular devotion to Madonnas runs back many centuries in Brabant. Brabantia Mariana (see Fig. 2.33), or “Marian Brabant,” a 1632 behemoth of around 1000 pages, is a repository of tales about miraculous images, many of which come to life, in shrines throughout the province. Mary has been dubbed “the Duchess of Brabant.” The attachment to the Mother of God remained compelling on the verge of World War II, when a little Marian chapel was hammered together near Moerdijk Bridge. Because of subsequent road construction, the house of prayer was later demolished, but the image of “the Lady of Moerdijk” has been retained. The locality at issue straddles a political and cultural borderland, the boundary between the Netherlands and Belgium.

Fig. 2.32 Dedication of Frank Valkenier [Frans van der Ven], De tuimelaar van Onze Lieve Vrouw (Tilburg, Netherlands: Private printing, 1944).

Fig. 2.33 Title page of Augustinus Wichmans, Brabantia Mariana (Antwerp, Belgium: Joannes Cnobbaert, 1632). Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

Did mere happenstance ordain that three Dutch-language writers should follow—not that all of them were of necessity cognizant of doing so—a Belgian predecessor by translating Our Lady’s Tumbler during the German occupation? Though in literary as in cultural history two points do not always determine a line, the coincidence of efforts by Vriesland, Smit, and Van der Ven carries all the greater force when one realizes that the story has been reworked in Dutch only rarely since then. Did the wartime literature exercise a later influence? The only clear evidence emerged a half century later, in a highly abridged and very free prose adaptation of Smit’s poem. A mere three and a half pages, this rewriting is one of twenty medieval Marian legends retold by a university teacher of medieval literature. The narrative is hardly a household name among Dutch-speakers, but it has pulled through in some later variants. In 1958, Felix Rutten published a prose version of the tale. He wrote it in the dialect of Sittard, the town in the Limburg region of the Netherlands where he was born. This long-lived minor Dutch author turned to the tongue of his native town late in life, from his seventies on. The leading character in his telling is Brother Balderik.

The most significant subsequent treatment of the miracle in Dutch, more for its authorship than for its impact upon being published, may be a short prose printed first in 1972. Its composer was Gerard Reve. Along with Willem Frederik Hermans and Harry Mulisch, he has been regarded as one of the “big three” of Dutch literature after World War II. In Reve’s reworking, the tale takes place in 799, the jongleur bears the name Henri de Maine, and the setting is Vosges. The performer, trekking by foot from Besançon to Poitiers, takes cover in a convent of nuns. He is allowed only to roll out his mat in the chapel. There he embarks upon an elaborate routine before an image of Mary. (Reve, who considered himself a convert to Catholicism, professed a particular devotion to the Mother of God.) As three nuns spy, the representation becomes animate, takes the showman into her arms, and mounts with him to heaven, as the organ thunders by itself and dozens of voices burst into song without any singers being visible. The narrative ends: “It was Christmas.”

The clustering of various forms in Dutch before and during the German occupation leaves us to contemplate the curiously discrepant destinies of their four creators. Think of Moens, the Flemish expressionist, nationalist, and Nazi; Vriesland, the Dutchman who was a thoroughly assimilated Jew but at least for a spell a Zionist; Smit, the Dutch Catholic; and Van der Ven, the Dutch Brabantophile. The most salient overlaps among the foursome would appear to be their life spans; their love of Dutch and other literature, especially poetry; and their shared devotion to this one story. In its infinitely complex simplicity the miracle hypnotized all of them. But even with the basic goodness etched into its very essence, it could not save all its readers and writers from the darkness of the times, and in some cases of their own souls. Narrative can be redemptive, but literature or no literature, the best capacities of humanity have endured unending strife against the worst. Good does not always triumph over evil.

Germany

The performer’s qualities of frailty, noncompliance with institutional norms, and perseverance in the face of chronic illness resonated with those writers in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands who suffered the occupation, but the same traits had failed to enthrall Germans in the late interwar and war years, from the 1930s through the mid-1940s. Although they made many turns to the Middle Ages out of discomfort with modernity, not all forms of antimodernism are equal. The Nazis spelled trouble for the early thirteenth-century tale and its later adaptations, and the climate that became conducive to Nazism proved to be uncivil to our little legend. During the cliffhanging of the Weimar Republic and the churlishness of the National Socialist period, the medieval entertainer all but retreated from Germany.

Why did the tumbler of the medieval French poem and the jongleur of Anatole France’s story disappear from German culture for more than two decades? Among the multiple reasons for his temporary suppression, one is that French literature and art came to be branded as dissident and decadent. In his Frenchness, the character had little to recommend him. During this period, the government made Völkischkeit or (to approximate in English) pure Germanness at least a notional goal in language, literature, and all the rest of culture. Hitler, quarrelsome and inflammatory as usual, slurred the French as an enfeebled and effete people. Their vernacular had been a major concentration within higher education during the Weimar Republic, but the Führer decreed that the speech and culture of France should no longer hold such special prestige. This condemnation held especially true for authors who exacerbated their Frenchness by being Jews or having a same-sex sexual orientation. The public and publishers alike spurned imports from foreign arts and humanities that they regarded as debased and debauched, and spun around instead to supposedly genuine German fairy tales. Fiction felt to be more authentically Germanic in origin held larger appeal. In such an atmosphere, Wagner and his spawn were more spellbinding than Massenet; Old Norse sagas, than Old French narratives.

Other complicating circumstances existed, too. When groupthink and group action were the order of the day, the jongleur or juggler could be called a nonconformist. A peace-loving loner, he could have been parodied as a milquetoast. In the style of his shows, he resembled more the foreign and Jewish artists who were alleged to be degenerate than the autochthonous ideologues who elicited superlatives from the Nazis. In his intense and independent-minded religiosity, he stood miles apart from the state co-option of Christianity that Hitler prescribed. Lastly, the progressive political views that made Anatole France appetizing to Stalinists were anathema to the authoritarian Germany of the time. His famous dictum “it is a noble thing for a soldier to disobey a criminal order” comported poorly with National Socialism.

In the half century from 1873 to 1924, German-speaking Romance philologists displayed limitless zeal in cranking out editions, textual criticism, interpretations, and adaptations of Our Lady’s Tumbler. During the second part of this period, the story’s vogue peaked around 1920 among writers, theater producers, composers, and others, even possibly filmmakers. Likewise, the 1950s and later saw a steady succession of German-language revampings of the tale by nonscholars across various genres. Illustrators too chipped in their talents. In between, from the late 1920s through the mid 1940s, such scholarly and literary efforts to bridge the cultural divides between France and Germany were no longer appreciated. Whatever rapprochement took place among intellectuals soon after the First World War became a thing of the past. Our lovely work, in all its manifestations, was effectively ostracized and suppressed, embargoed or eradicated. Attention to the French text from the Middle Ages slackened, new printings of Anatole France’s story dropped off, Massenet’s opera ceased to be staged, paintings and illustrations were not produced, and new versions cannot be documented.

In Germany, the last major fresh involvement of either a high-brow or a creative sort with the French tumbler for nearly thirty years was a philologically and poetically meticulous translation of the original octosyllables into four-footed iambic verse made in 1924 from the recent research edition of the medieval original. As we have already noted, the German form was printed as an appendix to a book by the art historian Wilhelm Fraenger. The man who put the poem into the modern language, Curt Sigmar Gutkind, made a conscious effort to outstrip his predecessors. In an afterword, he dismissed as failures the German versions of Wilhelm Hertz and Severin Rüttger, the first for being over-facile and the second for awkward and unidiomatic archaizing. If a comparison is to be drawn between this volume and any other scholarship written in the immediate aftermath of World War I, it would be with Romanesque representations, especially sculptural, of jongleurs as studied by Henri Focillon. This investigator was a French museum director, art historian, and professor, first in Lyons and later in Paris. The world had changed immeasurably in the quarter century since the 1898 Religious Art in France, the Thirteenth Century by his predecessor, Émile Mâle. The name of Focillon’s study can be translated as “Romanesque Sculpture: Apostles and Jongleurs (Studies of Movement).” The pairing of high and low offices in the subtitle may bespeak a desire on its author’s part to acknowledge or to intuit a social egalitarianism in the Middle Ages, not altogether unlike the leveling of class structure throughout Europe after the First World War. Previous research may have sought out and overemphasized the degrees of separation between the revered beings of sacrosanct evangelists and the immoral bodies of lowly minstrels. But Focillon’s essay, like the world around it, departed from the traditionalism and unbudgeably anchored hierarchicality of the preceding generation.

Curt Sigmar Gutkind

Until now the demeanor of the jongleur had been nothing but bouncy, bubbly, and bright, but an evolution was under way. The fate that overtook Curt Sigmar Gutkind as a result of his Jewish derivation throws light on what befell the tumbler and juggler in the Germanosphere over the ensuing decades. Born in Mannheim in 1896, this German citizen returned wounded from the First World War. He rounded out his studies with a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Heidelberg in 1922. In the 1920s and 1930s, he displayed breathtaking sweep as he cranked out foreign-language anthologies and translations as well as scholarship of his own. His researches bore fruit, to say nothing of many essays, in books on wine and food history, the seventeenth-century French playwright Molière, and travel in Italy. The translating and anthologizing encompass a selection of Italian poetry and a sheaf of Italian short stories, alongside research on French philosophy and Italian novels.

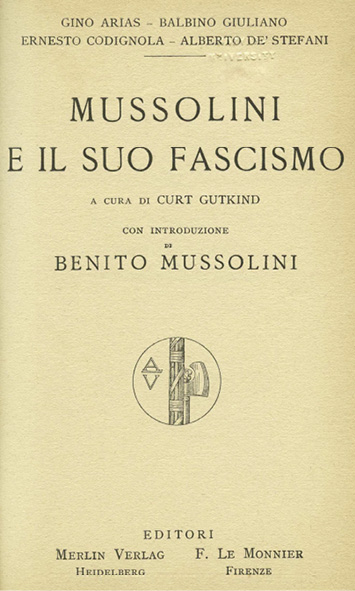

Amid the outpouring of humanistic scholarship that flowed from his pen between 1927 and 1929, the name of one hardback looks peculiarly mismatched. The English would be Mussolini and His Fascism. The title page (see Fig. 2.34) conveys much quietly. For instance, it announces an introduction by no less than Benito Mussolini himself, who at the time had been absolute ruler already for four years. Below that text, a circle circumscribes a representation of the ancient Roman fasces. This bundle of wooden rods, bound around an axe, denoted the authority held by one class of Roman magistrates. In Mussolini’s Italy, the symbol gave fascism its name, or at least the auctoritas of an association with the grandeur of Rome. Gutkind was not himself a full-fledged fascist, but he sympathized with the movement because of its stand on labor and union issues. Months before his book was published, he was handed the manuscript of Il Duce’s introductory remarks at a personal audience with him. The German had no inkling of what lay in store for him and other Jews in the fatherland a half dozen years later, courtesy of the equivalents there of Mussolini’s minions, namely Hitler’s Nazis. After 1929, a long gap ensues in the publications of this otherwise steadily productive scholar.

Fig. 2.34 Title page of Curt Sigmar Gutkind, Mussolini e il suo fascismo (Heidelberg, Germany: Merlinverlag, 1927), with introduction by Benito Mussolini.

Behind the banality of this hiatus in his curriculum vitae lies the grim reality of life for European Jewry under National Socialism. A Romance philologist who specialized in Italian, Gutkind first held a lecturership in Florence from 1923 to 1928. This initial position he owed to his dissertation director, Leonardo Olschki, an Italian Romance philologist also of German Jewish background. From 1929, his former student worked as a professor in his hometown of Mannheim, at a translation institute set up there in that year. He married the daughter of Theodor Kutzer, a Catholic who had been the elected head of Mannheim from 1914 to 1928. She went by the name Laura Maria Gutkind-Kutzer. Her husband directed the translation institute from 1930 to 1933, and in 1934 he was employed briefly on the staff of the business school in Mannheim.

Now neither Gutkind’s status as a wounded veteran, marriage to the daughter of a notable mayor, nor proximity (even if only passing) to Mussolini could stave off what befell him thanks to the Nazis. After the racial laws cost him his position, in April, 1933 he joined the exodus of his coreligionists on the run from Germany. Within this larger displacement, he belonged to a skillful but ill-starred elite of Romance philologists bracketed as Jews. He made a quick exit to Italy, but despite having obtained Italian citizenship and developed amicable relations with the country’s strongman, he could not secure a post there. The legend “Two Peoples and One Struggle” on a 1941 German postage stamp (see Fig. 2.35) proclaimed the alliance between the iron-fisted leaders of fascism and Nazism as well as between their nations. These relationships trumped any special consideration to which the German refugee may have hoped to be entitled by virtue (if that is the appropriate word) of his cordiality with the Italian autocrat.

Fig. 2.35 “Two Peoples and One Struggle.” German postage stamp (12, with a supplement of 38). 1941.

In 1934, Gutkind went first to France, to unsalaried teaching at the Sorbonne in Paris, and then on a fool’s errand to get into the clear south of the Alps. In 1935, he ended up in England, at Magdalen College in Oxford. In 1939, he obtained positions as an instructor at Bedford College and a reader in Italian at University College, both in the University of London. These arrangements turned out not to last long, because they (and his Jewish ethnicity) did not cushion him from suspicion owing to his national background and previous political affiliations. In Britain, the twofold setback of his Germanness and erstwhile sympathy for fascism counted to his discredit more than the reasons for which he had failed to gain a haven anywhere on the Continent argued in his favor.

In 1940, hot on the heels of the German rout of France, the British authorities feared an invasion of Britain itself. Against that backcloth, they grew alarmed over the possible existence of a “fifth column” among Italians and Germans resident in the United Kingdom. Consequently, they resolved to defuse the danger of domestic treachery and trouble by deporting the individuals of concern to them. The forty-three-year-old Gutkind, registered as an Italian citizen, was arrested as a hostile alien, evacuated to Liverpool, and shipped to Saint John’s, Newfoundland, to be interned in Canada.

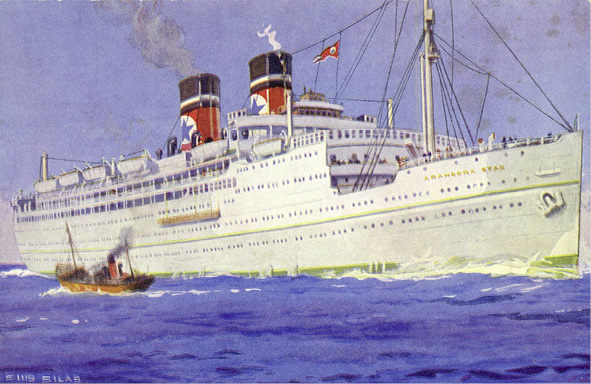

The unfortunates in the same predicament as Gutkind boarded a steamship that until recently had been a luxury liner. Yet what lay ahead for the passengers and crew was anything but a vacation cruise. The Arandora Star (see Fig. 2.36) foundered off the coast of Ireland on July 2, 1940, after being torpedoed. The steamer came to grief when a German submarine, as it concluded a patrol, fired its one unspent missile. Later, the officers of the U-boat professed to have acted on the mistaken assumption that the weathered and faded old paint on the vessel was military colors. Concurrently (and contradictorily), they also maintained their belief that the weapon they shot was defective. In any case, several hundred people from the shipload of German and Italian detainees lost their lives amid the frigid waves of the squally Irish Sea, or in the bowels of the ship when it sank. A smattering of other Jews who had been rounded up with Gutkind, such as the Italian literary critic Uberto Limentani, survived the cataclysm, but the translator from Mannheim was among the unlucky majority who drowned in the Atlantic.

Fig. 2.36 Postcard of the Arandora Star (before 1940).

The First World War had badly battered the vitality and prospects of the European cultures that had first breathed life into the tale of the tumbler after his discovery or rediscovery in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War. In the late 1920s, 30s, and 40s, a miracle that had been a minor monument to the optimism and prosperity of the belle époque may have seemed frivolously irrelevant, when political anxieties were whetted to stiletto-sharpness, as many readers and artists struggled beneath the overfreight of political problems and worse. It could even have appeared contemptible, as nationalism took hold in more than one country and drove a boorish repugnance of foreigners or supposed outsiders. Yet whatever crises Europe had had to face before the Second World War paled into insignificance beside those it ran up against now, for the scale of suffering and death outpaced anything humanity had seen before.

Hans Hömberg

The biography of Gutkind tells one side of the story about the years of National Socialism in Germany. Another would be Hans Hömberg, who lived much of his adult life in Austria. Early in the Second World War, this German-born writer composed what may have been his most famous piece of theater, the 1940 Cherries for Rome. The play deals with Lucullus, a Roman general, politician, and plutocrat of unparalleled success. The text is touted sometimes for its pacifist traits.

In his drama, Hömberg may have made slantwise efforts to keep himself at arm’s length from the National Socialists, but those attempts did not offset the closely contemporaneous book that he produced under the pseudonym J. R. George. The volume novelizes the notorious 1940 German motion picture Jew Süss. The cinematic costume drama, filmed at the bidding of no less a Nazi potentate than Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 1945, succeeded in packing movie houses and earning strong box office receipts. It presents a historical pageant that follows, with many distortions, the legendary career of Joseph Süss Oppenheimer, who had served as financial adviser and tax collector under Duke Karl Alexander of Württemberg from 1733 to 1737. While purveying intense anti-Semitism, it couched the propagandizing as entertainment. Goebbels commissioned the film after the conquest of Poland, with its large Jewish population. By demonizing the Jews as hook-nosed, conspiratorial predators, he intended it to build a supportive environment on the home front for the Final Solution.

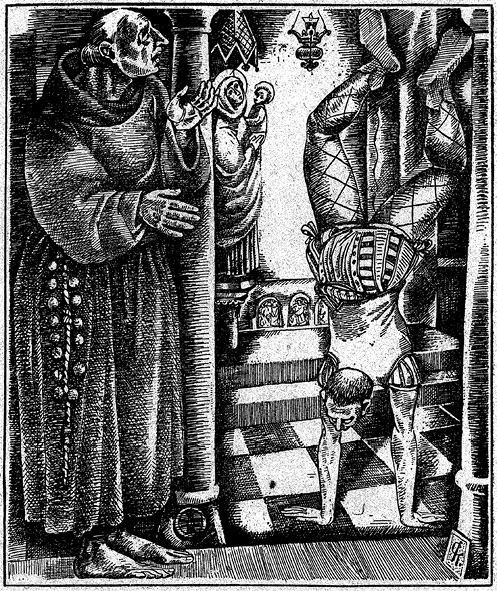

The novel, close to two hundred pages, is not a whit better than the cinema in its demonization of Jews. Like the movie, it depicts the protagonist as he enlarges his pelf and power through dealings with the nobility, especially the duke. Here we can see Süss showing off the jewels and crown in his wall safe (see Fig. 2.37). Ignoring well-meant monitory words from his elderly rabbi (see Fig. 2.38), he keeps on increasing his riches by hiking taxes, tolls, and prices, and in helping his fellow Jews take over more and more of Württemberg. The project reflects the author’s lifelong passion for moving pictures, which at this stage evidenced itself in the reviews he wrote as a cinema critic for the Nazi newspaper Popular Observer: Militant Newspaper of the National Socialist Movement of Greater Germany.

Fig. 2.37 Süß shows off his wealth. Photograph, 1940. Photographer unknown. Published in J. R. George [Hans Hömberg], Jud Süß: Roman (Berlin: Ufa-Buchverlag, 1941), facing p. 32.

Fig. 2.38 Süß’s elderly rabbi. Photograph, 1940. Photographer unknown. Published in J. R. George [Hans Hömberg], Jud Süß: Roman (Berlin: Ufa-Buchverlag, 1941), facing p. 97.

After the hostilities, Hömberg worked energetically on the airwaves, as a writer of scripts and as a broadcaster. In 1961, he published (to put the name into English) The Juggler of Our Lady. The small book in fact subsumes three tales, of which the title story is only the first and not even the longest. In a compact afterword, the author set forth his conviction that the Middle Ages were more permissive than his own era in the treatment of certain themes touching upon religion and clerics. Furthermore, he observed that twentieth-century readers had trouble digesting miracles and deeds of saints as written in their original form, whereas they reacted with oohs and aahs of pleasure and wonderment when he read them aloud. This realization had prompted him to accept an invitation from a press and to go down “the shaft of the past.” In additional remarks, Hömberg demonstrated his familiarity with the 1920 edition by Lommatzsch of the thirteenth-century original, the French poetastery by Borrelli, the French prose short story by Anatole France, the 1894 German retread by Robert Waldmüller of the medieval French, and the English radio (and recorded) version by John Booth Nesbitt. Hömberg’s professional involvement in broadcasting would have heightened his interest in the American radio play.

In restructuring Our Lady’s Tumbler, Hömberg fuses elements of the centuries-old legend with aspects of Anatole France’s and other modern adaptations. He attaches to the leading character the name of Jean Vapeur, with the cognomen being the French for “steam” or “fume.” This entertainer possesses the dancing skills familiar from Our Lady’s Tumbler, alongside his juggling talents from the 1921 Nobelist. The story is set in France, to all appearances in Paris. Hömberg is noncommittal about the chronology, perhaps medieval but at the same time not closed to such modern-day features as the Café Apollinaire. The tale concludes with what is alleged to be a Latin inscription on a marble tablet in the crypt of the main church of Our Lady, where the protagonist is buried: “Here lies Mary’s jongleur, a pure artisan, Jean Vapeur.” Nothing cryptic here, save the location.

The narrative is enlivened by a couple of illustrations, one of which doubles as the cover art. The first (see Fig. 2.39) shows the jongleur, hat in hand, as he nerves himself to step through a portal with a pointed arch and set foot in the monastery. The second (see Fig. 2.40) depicts the Madonna poised on a sickle-shaped moon. She beams from ear to ear, as the child she cradles reaches out his arms toward the jongleur, costumed as a clown, who kneels before her and juggles nine balls. Both woodcuts are far more guiltless than the illustrator himself. The Austrian artist Ernst von Dombrowski had mixed himself up early in the National Socialist movement. During the war, he continued to fabricate inordinate quantities of Nazi propaganda, including anti-Semitic writings. His pieces harvested approving comment from Hitler himself, and were exhibited in collections of German art. After two years of postwar internment by the Americans, he resettled in Bavaria. He collaborated on projects with many ex-Nazis, belonged to extreme rightist organizations, and received a 1976 award from an association that was dissolved in 1998 because of its Nazi associations.

Fig. 2.39 The juggler arrives at the monastery. Illustration by Ernst von Dombrowski, 1961. Published in Hans Hömberg, Der Gaukler unserer lieben Frau (Vienna: Eduard Wancura, 1961), 13.

Fig. 2.40 The juggler performs before a smiling Madonna and Child. Illustration by Ernst von Dombrowski, 1961. Published in Hans Hömberg, Der Gaukler unserer lieben Frau (Vienna: Eduard Wancura, 1961), 25.

Hömberg’s version of the story would appear to have attracted little notice even when first published. Along with the rest of his works, it languishes in oblivion today. Assiduous readers may seek it out, to determine for themselves whether the two collaborators’ National Socialist background had any consequence on the choice or framing of the tale. Did the narrative offer a touch of redemption through worship and art to erstwhile Nazis who turned to it; were they unrepentant of their past and yet still capable of wallowing in religious emotionalism; did they do their best to shrug off their earlier misdeeds and go on with life; or did the coming together of their motivations and reactions to the account differ from any of these possible explications?

After the War

In the years of peacetime rebuilding, Germans, both erstwhile Nazis and not, turned to Our Lady’s Tumbler and its later adaptations as much as did the writers and artists of any nation except the United States. The economic miracle of postwar Germany had the side effect of creating a yen for Marian miracles. To be entirely serious, the medieval setting may have had the appeal of seeming remoteness and innocence from recent events, while also being deliciously free of the Wagnerian stigma of Germanic myths and sagas from the Middle Ages. If any strain of medievalism fell as a casualty of the Second World War, it was of the Germanic and not the Picard sort. In fact, the French backdrop may have enabled Germans to pick up the strands of the détente with their neighbor that had been taken off the table during Hitler’s rule. Moreover, the fact that the story stood then at a high point in US mass culture thanks to radio and television may have further burnished it.