5. Positively Medieval: The Once and Future Juggler

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0149.05

It is a sad old age that loses all its memories. If it were true, as some have said, that St. Thomas was a child and Descartes a man, we, for our part, must be very near decrepitude. Let us rather hope that truth in its eternal youth shall keep our minds always young and fresh, full of hope for the future and of force to enter there.

The Juggler’s Prospects

It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.

This biography of a once-touted story has turned out to be, no typo and pardon the groaner, a jugglernaut. Yet despite the length and girth of this study, much more remains for future sleuths and bloodhounds-to-be to scrutinize. Loose threads could be sewn up—or, to put it more cheerfully, allow for pioneering new beginnings. More whys and wherefores could be analyzed and slotted into the great crossword and across-tale puzzle. Thanks to the ongoing digitization of archives and ever more detailed metadata for items being sold on the web, additional particulars come online daily. With further investigations by others, the chronicle that outlines the reception of the medieval tale might be dragged out unendingly.

What lies in store for Our Lady’s Tumbler in years ahead? The relative unfamiliarity of this exemplum from the Middle Ages today makes its earlier successes in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries even more impressive and surprising. Authors die in time, but literature is not subject to the bylaws of mortality and impermanence. Rather than being unique artifacts that can be destroyed at one fell swoop, tales retain a life force. They have a potential longevity beyond that of any human teller or writer. None other than F. Scott Fitzgerald averred that there are no second acts in American lives—but this ground rule may not pertain to narratives. Old ones die hard. To kill off a story requires total annihilation. For one to be declared dead by the coroners of literary history, all documentation relating to it must be extirpated. To go further, all memories of it must be expunged from the minds of living readers, listeners, and viewers—and making people unread, unhear, and unsee a tale is not easy. When it comes to fiction, character assassination does not happen at the snap of a finger.

When a tale possesses the richness of implications that this one has, the universe of wormholes into its meanings knows no limits. This account may be small change, a low-denomination coin in the transfer of cultural capital from one time and place to another around the globe. Yet in its best iterations, this miracle achieves exactly what the most sublime of human creations are supposed to do: it quickens emotions and prompts thoughts of the transcendent. Behind it, the humanities sweep in, to inspire and inform readings of those immediate reactions. The coexistence of many possible interpretations is a fact of life and language. Likewise, this heterogeneity constitutes a reality and part of the charm of literature and art. The infinitude of texts in verse and prose, unmoving and moving images, read aloud or acted out, explains why we might speak of our species as homo interpretans.

With its truly storied past and its propensity for provoking many significations, will the account in Our Lady’s Tumbler and The Juggler of Notre Dame live on in broader culture? Will either or both versions be encountered in general reading, popular entertainment, school assignments, church sermons, or all the above? Notwithstanding a feebly elegiac note in the epigraph that put this conclusion in motion, I remain sanguine that the narrative will not merely scrape by but even thrive. Good guys come last, but the romance of stories often turns out otherwise. The medieval poem and its multifarious heirs may have appeared moribund, but they have always been, in their humble ways, revivified. As the world turns, the worm will turn.

The important thing is for enough of the past to be kept living. To take up, reject, adapt, or do all three at once, the here and now must comprehend a minimum of what has prefaced it. Bygone languages, lore, and art together form the taproot that nourishes the present. Bad luck will befall us if we chop or uproot it without getting to the bottom of what we do. For their mutual well-being, the past and present must converse constantly, and their dialogue contributes immeasurably to the differences between bestsellers—whether stacked in brick-and-mortar bookstores, stocked in libraries, or retailed digitally—and classics. The back-and-forth enables literary traditions to burgeon, in which authors and texts infuse each other.

More expansively than the tale, the Middle Ages themselves do more than merely subsist. Indirectly, they often stay very much alive in residues from the Arthurian legend. More directly, they survive in such twentieth-century authors, now canonical and even hoary, as C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Umberto Eco; and in fantasy role-playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons, action-adventure video games such as Assassin’s Creed, and series for cable and television such as Game of Thrones. Such entertainments have accustomed us to hybrids of the medieval and postmodern: without blenching, we accept unthinkingly and unblinkingly the hyperbolically in-your-face anachronism of the self-contradictory phrase “medieval video game.”

In many settings, the architecture of the imagined Middle Ages surrounds us. The Gothic revival that was in the good old days so central in European, American, and British Commonwealth countries tailed off to an end a century ago. Yet before passing from sight, it insinuated itself into many cityscapes. Consequently, to this day neo-Gothic belongs to the palette of architecture and decorative arts to which everyone is exposed sooner or later on both sides of the Atlantic. The style rings the horizons of the flaneur who prowls urban streets, promenades by old buildings, patronizes art museums, or even just samples literature widely. In Europe, the original or revival cathedral, closely followed by the town hall of the same type, signals that a city is a city and in fact that it is European. In the United States, the same building style is especially salient in universities and churches. We have seen that the manner is by no means limited to these two kinds of construction, but dailies will plant pointed arches in the background of an illustration to inform their readers that the topic of an article is college or religion.

For all the times we lay eyes upon Gothic, do most of us ever stop to sniff out what stands before our noses? How often do we smell the roses—or in this case, the windows shaped like the flowers? Even less do we ponder the pros and cons, aesthetic or symbolic, of either the authentic medieval form or its multitudinous modern revivals. In a 1957 essay, Roland Barthes drew a parallel between the automobiles of his day and the Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages. Ten years later, he juxtaposed the modern and the medieval even more famously in “The Death of the Author.” In French, the title of the disquisition just mentioned plays upon that of a fifteenth-century English text. Le Morte d’Arthur, written by Sir Thomas Malory, means “The Death of Arthur.” Imagine that: the literary theorist and professional problematizer rolled in medieval literature to be his heavy artillery—catapults and trebuchets—as an opening gambit to terminate authors and replace them with texts, while doing away with literature and bringing in discourse.

Let us dawdle to soak up the intellectual intoxication of the City of Light in the mid-twentieth century. In the meanwhile, we can about-face from textuality to technology. In comparing motor vehicles with ecclesiastic architecture, Barthes referred to the Citroën DS. This model was manufactured from 1955 to 1975. Reversing our expectations, the French theoretician construes the medieval cathedral as a consumer object and the late twentieth-century car as effectively a magical carpet. His hypothesis that the auto is enchantment rests (and capitalizes) on its witty name. In French, the letters DS are enunciated the same as the word for “goddess” (déesse): the two are homophones. The essayist explains the pun in the second paragraph, and he brings it home again in the final sentence of the short essay.

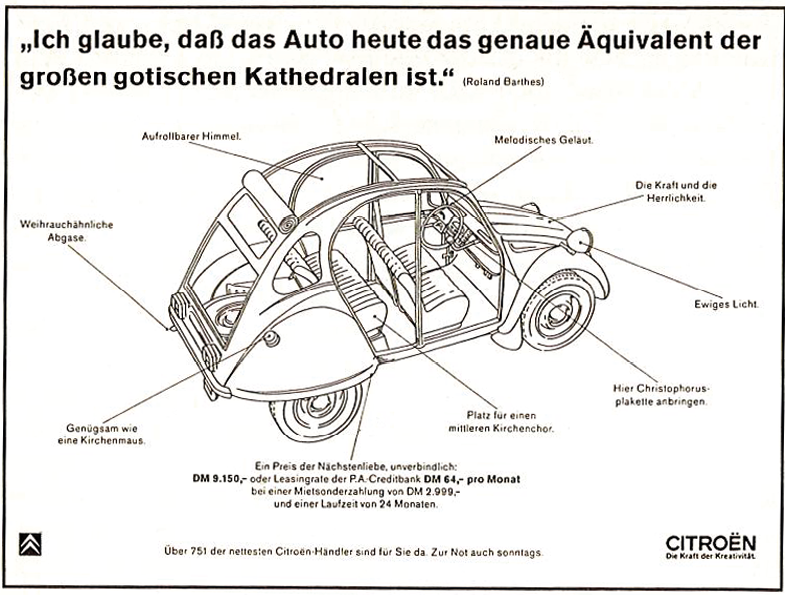

In 1988, a tongue-in-cheek spoof of an automotive advertisement in a major German newspaper quoted the first statement in Barthes’s observation as its caption (see Fig. 5.1). Below stood a cutaway drawing of a Citroën DS, with lines to identify features and potentials. “Eternal light” radiates from the headlights. (The make of car is wrong, but we have here a clear case of Fiat lux.) The dashboard enjoins the reader to “put up a Saint Christopher medal here.” The back seat offers ample “seating for a middle-sized church choir.” The fuel tank, by metonymy for gas consumption, is “modest as a churchmouse.” “Incense-like exhaust” spews from the tail pipe. The ad finds affinities between automobiles and great churches that medievalize technology, but for parody rather than, as had been the case only a little more than a half century earlier, comfort.

Fig. 5.1 Advertisement from 1988 for the Citroën DS, featuring a quotation from Roland Barthes that compares automobiles and cathedrals.

Closely related commonplaces from eight hundred years earlier have been solidified in two phrases, “transfer of empire” and “transfer of learning.” In a widespread view, medieval people inherited from antiquity both a scepter of dominion (political and military) and a lamp of culture (philosophical and artistic) that had resided first among Greeks of Athens and later among Romans of the Eternal City. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Americans achieved a commensurate transference or appropriation of their own, by arrogating the European Middle Ages to themselves.

Individuals of incomparable wealth in the United States siphoned the material culture of ye olde days from Europe by buying up and bringing home art objects and architectural elements. These one-in-a-million millionaires also raised a trail-blazing Middle Ages of their own making in three dimensions, by taking in an altogether fresh direction the sham ruins that had been constituents of medievalism in the romantic era. In consecutive Gothic revivals, they built imagined medieval structures throughout not only Europe but even more the New World and beyond. These buildings were anything but ruins. Rather than shyly sham, they presented themselves as self-confidently medievalesque. Yet they stopped short of claiming to be authentically medieval. The architecture came arm in arm or arch in arch with literature, as the readers and writers of this much later period translated the earlier epoch to suit their own cultural environments. This is the nature of historicism.

To take the example that has propelled this multivolume book, they made modern versions of medieval literary texts. The process was moving, both literally and figuratively. Among many other consequences, the transference across time and space redounded to the legacy of closeness between Europe and the United States that had persevered for a few hundred years. Does it make sense for America to disinherit itself and recoil now from appreciation of either of these pasts, the Middle Ages or the nineteenth and twentieth century? Does opening up to new stimuli presuppose swiveling away from previous ones? Are the arts and history a pie that never grows larger?

Medievalism has been construed as a colossal, cathedral- or college-sized failure. It has been critiqued as a gremlin that instigated a breakdown or stasis in culture, a phantasm that turned out to be ill-founded, or at best that evaporated into nothingness. The Gothic revival itself has been presented in this same light, as a backward-looking flight from modernity into a fanciful past that was not suited to meet the ultimatums of the present—and even less those of the future. But is that reverse teleology not a caricature and mischaracterization? In 1831, John Stuart Mill described, not specifically Gothic revivalists, but more generally “those men who carry their eyes in the back of their heads and can see no other portion of the destined track of humanity but that which it has already traveled.” Was the revival retro in so hideously Dantesque a physiognomic fashion? Did it in fact fall apocalyptically flat? Is the only brand of traditionalism stodgily and even asphyxiatingly self-justifying? Is a penchant for studying and savoring aspects of the bygone inherently reactionary? If you have done no more than skim even one of these six volumes this far, you can guess my retorts. Label me a pugilistic Pugin, call me a Cram redux (or prolix). Flip open my billfold and find a thin oblong wafer of granite: the contents of the wallet prove me to be a card-carrying Gothophile, out to redevelop a story and revive a revival—but that does not mean being out to make Gothic great again, or to make a vain and ugly effort to reinstate culture, society, and demographics as they were constituted a century or a millennium ago.

Reaching a negative verdict on the architecture at least is not entirely fair. Few structures are erected today in strict classical style, as was frequent in the nineteenth century, but the absence of Corinthian columns from present-day buildings is not taken as a rejection or failure of classicism. Old Gothic edifices remain around us on all sides. In many American cities, apartment buildings in the manner survive aplenty uptown. Skyscrapers with all the appurtenances of the style can still be spotted in major municipalities, even if overtopped by sleeker, more modernist successors. The architectural topography of the United States is stippled with collegiate Gothic, both towers and otherwise. We fare all the better for the variety. Why should contemporary cultural diversity be good, but not its chronological equivalent—past cultures?

How many who grind away inside colleges in Britain with Gothic architecture, or in North America with collegiate towers of similar sort, treasure their years of undergraduate education as being distinct, and in positive ways, from the rest of their lives? If students in growing older nurture such fondness, it happens in part because the spaces they inhabited while in residence are marked apart as being quaintly separate. Is that detachment a prime cause for regret? Should it be? It would be foolhardy to root like a cheerleader at a pep rally for a return to any recreation of the Middle Ages, any more than to plead for the no-win effort of dialing back the clock to any slice of the medieval period itself. That endeavor would be especially hard once we arrived at the portion of the era when such timepieces did not exist. Yet I hope to have advocated at least implicitly for the pleasure and even the utility of looking back across the centuries to the best of what was expressed in far earlier literature and art. Many watches should not be rewound, but human machines need to unwind or wind down, and one way of decelerating is to travel back hundreds of years.

Sure, rumination on days of yore may be melancholic or even burdensome. By the same token, it may also be a source of buoyancy. Those bygone times may be both explicated and enjoyed. Gestures may be made to precedents, and honors may be accorded to them, without being unfaithful to the present. The title of Tom Wolfe’s novel, mined and refined posthumously from an unpublished manuscript for publication in 1940, proclaims You Can’t Go Home Again. While many memories are not as enriching as the experiences when lived, it holds equally true that others oxidate to become even better: changing coloration need not be chastised as discoloration. Likewise, there is indeed no going back—but we can fumble forward to a new back. In fact, I see no meaningful progress for human culture that does not come with cognizance of the past. Relegating to the dustbin of history everything that transpired before us is not an option. Old-fashioned need not be outmoded and should not be considered a pejorative, but an alternative. It is something that we can hold, after we have understood it. That is often more than we can say about the new-fangled. (How many of us have even the most indistinct inkling of what “fangled” means?) Like many other reactions and pleasures, nostalgia may be used occasionally or abused habitually. In some religions, it may be classed as a virtue or a vice.

Gothic revivals fell out of vogue in the Me generation, but now we are deep into the meme generation of millennials. Time and tide wait for no man (or woman, or any other human gender category now existent). The pendulum of tastes swings without respite, both inside and outside the timeless but time-filled cases of grandfather clocks. Could a refreshed and revitalized revival go viral? It would not need to be as a style that could or should predominate as it did for much of the nineteenth century. Yet at least it could have a resurgence as one among various choices on the stylistic palette at the disposition of artists to recombine and for others simply to revel in. The medieval, Gothic, and the juggler will all return, though we cannot reckon on the specifics. They are all deathless. Nothing will fail to live except the conceit that any of them will die: perish the thought!

Could or should we re-Gothicize, by reclaiming the style from the mascaraed Goths in fishnet stockings? Can Gothic go from shibboleth to a buzzword once again? Can medieval be something good, rather than the almost exclusive negative that it seems to have become? Or are architecture and literature in this vein doomed to decompose in forgottenness? Are they extraneous to global audiences that know and show no need for the fine points of European history or the parsing of past Western literature? My comeback would be that we are all entitled to self-select, and that one choice is to relish the old differently from the new. The expressions “old favorites” and “golden oldies” hold continued traction for good reason. We have the prerogative of constructing our memory palaces in whatever modality we choose, and a cathedral may serve very well, thank you. Quarried stone may be 24-karat gold.

For obvious reasons, culture must be culture-bound—but being bound need not be the same as enchainment or enslavement. Historicist revivals, such as Gothic ones, by their very nature relate to renewal and recreation. They are spells of cultural energy that eventuate in reprises of literature and architecture, of stories and buildings, among many other things. The duplicates succeed all the better when they do not exactly replicate their models. The recreated forms belong to the constant pulsation between the poles of tradition and innovation, or conservatism and progressivism, that is essential to the common weal of societies, cultures, and civilizations. In the beginning, Gothic carried bad associations, but those were converted at least some of the time into positives. People hungered for order and innocence. Far worse appetites have existed. If at a given point individuals stopped wanting or putting credence in such principles and qualities, the blame is not to be pinned on the Middle Ages. Medievalism did not miscarry. To risk being anachronistic (and when is any movement by this name ever not so, at least to a degree?), it was too big to go wrong and fail. But nonetheless it has been tagged a failure.

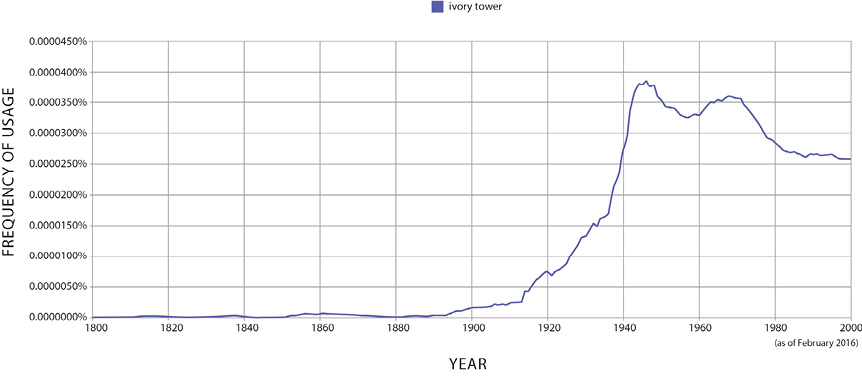

Like a pointillist painting on a continent-wide canvas, the United States remains dotted here and there with pretty neo-Gothic buildings. A surprising number of places even preserve bits and pieces of authentic architectural elements in the original manner. In the Northeast and mid-Atlantic, we can point to the collegiate Gothic of universities such as Yale, Princeton, and Duke, and Gothic revival churches such as Saint John the Divine and Washington National Cathedral. However easy it may be to grumble about such phenomena, the design style of that phase, flanked by Edenic landscapes laid out by designers such as Beatrix Farrand, is unchangeably associated with campuses throughout the United States. It ties them to the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge. Much of the fabric has become threadbare and frayed in both architecture and landscape architecture, although not so much as in broader culture. As institutions of higher learning have sought to shoehorn buildings where they were not meant to be wedged, they have flouted the presiding notions that formerly governed the delicate interdependencies among buildings, lawns, gardens, groves, orchards, paths, roads, and other spaces. Others can make up their minds whether universities have also renounced the spirit and separateness that the architecture of the buildings and land were intended, or at least pretended, to achieve. For the time being, the not-undisputed dream of the ivory tower has fallen flat, if it was not conceded to be an illusion from the get-go. Right now, the image has become to many a pejorative—an object of aspersion for its pie-in-the-sky elitism. Yet not everything in the conception of universities in the early twentieth century deserves to be jettisoned irrevocably. In fact, the elusive reverie of an aerie atop a turret has often gone hand in hand with the American dream, if such a wraith can be imagined as having a body and walking. For this reason, if not for many others, the precipitous decline in stature of the ivory tower should prompt reflection (see Fig. 5.2). The steeplechase has undergone a miserable cutback: we suffer collectively from turret syndrome.

Fig. 5.2 Google Ngram data for “ivory tower.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

The ivory tower in its Gothic iteration is schizophrenic. It is shut off, if nothing else because it often forms part of a quadrangle, like a cloister. At the same moment, it lies open and exposed. It draws the viewer into a movement that is inherently elevating and can be transcendently illuminating. Because of its style, the tower instantiates contact with a heritage of intellectual camaraderie and exploration that stretches deep back into an earlier millennium. It offers centuries of soulfulness as an antiserum to the dispiriting toxins of the present.

And the juggler? Sure, he has suffered habitat loss. The environmental damage has come not in a shortfall of Gothic buildings but in a spiritual change in surrounding society. Like an ivory tower, our entertainer has his feet planted firmly on the ground but his head in the clouds. His spiritualism could play today, unless his religiosity disqualifies him from the running. In days of victim-chic, the tumbler of the original story shows potential. He arises from an underclass of physical laborers—peons. If he belongs to a caste, it comprises untouchables. In his sexuality, he defies quick classification. We have no information by which to subsume him as heterosexual, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, or asexual. Yet to judge by his later fate, especially once the opera by Massenet took off, he could be and has been filed under most of those headings—so long as that spirit of his does not go missing in the process, since it defines him. At least sometimes, the unexamined pieties of the past have been repudiated and replaced by the identity politics of today. In due course, our own perspectives and preoccupations may be recognized also to have been flawed and fragmentary: in the fullness of time, we too will prove to be dated. The juggler’s way urges us to boost within ourselves humility and humor. Such habits will make us as acutely aware of our own failings as we are censorious of our predecessors’ or contemporaries’. Others may decide for themselves if knowledge is power; whatever conclusion they draw, self-knowledge is good.

Gropius vs. the Gothic Ivory Tower

Neither medievalism nor colonialism can express the life of the twentieth-century man.

Modernist vivisections of the ivory tower bear scrutiny. One of the most incessant assailants was Walter Gropius. Especially in his guise as director of the School of Architecture at Harvard University, this mouthpiece of the “New Bauhaus school” when transported to the United States sought the opportunity to shape “young people before they have surrendered to the conformity of the industrial community or withdrawn into ivory towers.” He constructed a bridge between the delicatessen European avant-garde and homegrown American architecture. In an address in Chicago, he expressed his wish for the artist, including the architect, to be reintroduced into the collectivity: “From his ivory tower he will move closer to the latest laboratory and to the factory; he will become a legitimate brother of the scientist, the engineer, and the business man.” Gropius saw the university as facing three choices: to partake in the real world by applying art to achieve socially progressive goals, to yield to the compliance required by industry, or to retreat into the ivory tower world. Without hesitating, he opted for the first. Even in the late 1960s the same professor stood ready to declare: “The ivory tower man is out. The artist needs to swing.”

The German-born architect had not always made a straw man of the ivory tower man. In the beginning, he did not buck at the ideal of reviving or transforming Gothic. On the contrary, in a 1919 speech he espoused his commitment to making his contemporary reality the “best time of Gothic.” In that very year the painter Lyonel Feininger carved a woodcut of a great church to adorn the manifesto for Bauhaus—and to solemnize Gropius’s conception of the “future cathedral” as an avatar of modernity (see Fig. 5.3). Later, the architect reacted differently to the structure and spirit of the style as it was appropriated for collegiate settings in North America. He became anti-historicist and even anti-history.

Fig. 5.3 Lyonel Feininger, Die Kathedrale, cover design for the Bauhaus manifesto, 1919. Woodcut, 30.5 × 19 cm.

Among acolytes, the German architect went by the affectionate nickname “Grope.” When modernist constructions fell under siege by traditionalist Harvard graduates, these faithful followers picked up his language and metaphor to defend the embattled new buildings against those who villainized them. Parroting their past master, they too made the ivory tower a whipping boy. One wrote:

Must we take the word of our older alumni that an ivory tower is the only true architecture? An ivory tower, to be sure, is a beautiful thing—ivory costs even more than marble. And a tower certainly is functional—it protects us from the sight of all the grubby creatures below. But Harvard, as she has on recent occasions reminded the world, prides herself, not on her ivory tower, but rather on her “free marketplace of ideas.”

Sad to say, such reduction of thoughts to commodities paved the way toward the corporatized university of today, in which the onetime ivory tower sometimes melts away to the most ill-defined of memories. Is it so very inexedient for a society to have some members who, helped by the thrust of steeples, have their heads in the clouds? Doesn’t the world need dreamers alongside pragmatists, pure scientists along engineers? It takes all kinds to make a world.

Universities are entrepôts for the refinement, assembly, quality-testing, storage, and transshipment of knowledge, culture, and values from one generation and one society to another. The Olympian detachment and independence required for many stages of the process have fallen out of vogue. Instead, institutions of higher learning now aim to incubate among undergraduates the kind of innovation that happens in the corporate workshops of software designers. At the same time, universities seek to commoditize learning and to profit from retailing the results. Finally, they have taken upon themselves responsibility for solving the teething problems of the world. Giving back in outreach and exhibitions is one thing, but how good a job are academic institutions doing as self-appointed saviors in areas where government and philanthropy have been the traditional actors? Is the world in better shape? Are they more appreciated for their efforts? Can they pick up the slack without losing their essence?

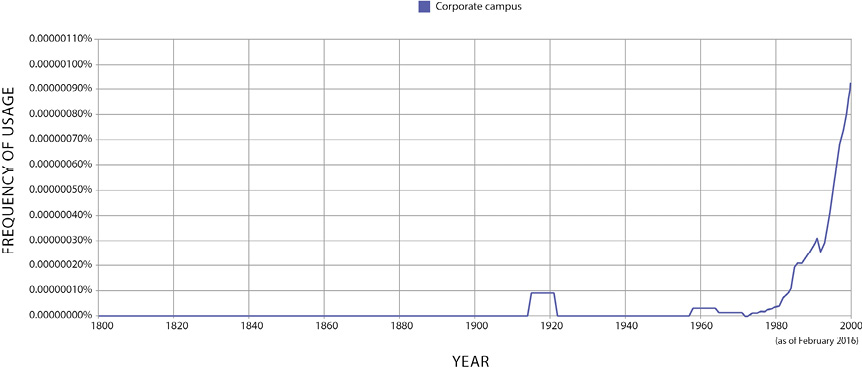

In the meantime, corporations have requisitioned for their own purposes the term campus, which until comparatively recently belonged without question to educational institutions. The noun first cropped up at Princeton, when it was still the College of New Jersey, in the eighteenth century. Others must determine whether it was meant to denote cultivated plots in an agrarian sense, the countryside, military training grounds, or a combination of the three. In soldierly use, think Campus Martius and remember that the campus of the private university has a cannon holstered muzzle-downward in it—a mode of open carry that makes no one feel endangered.

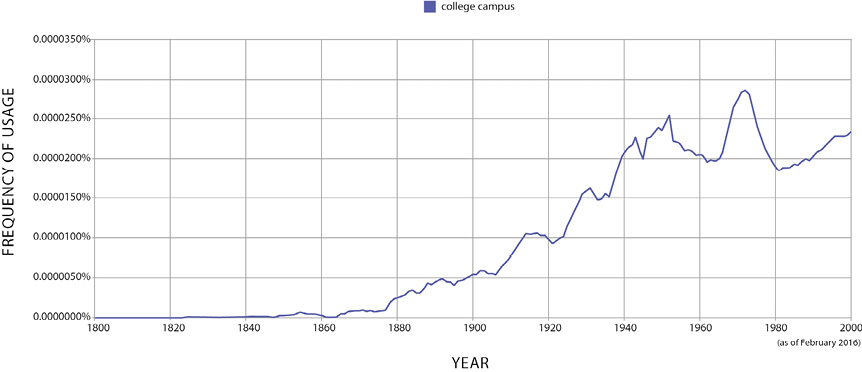

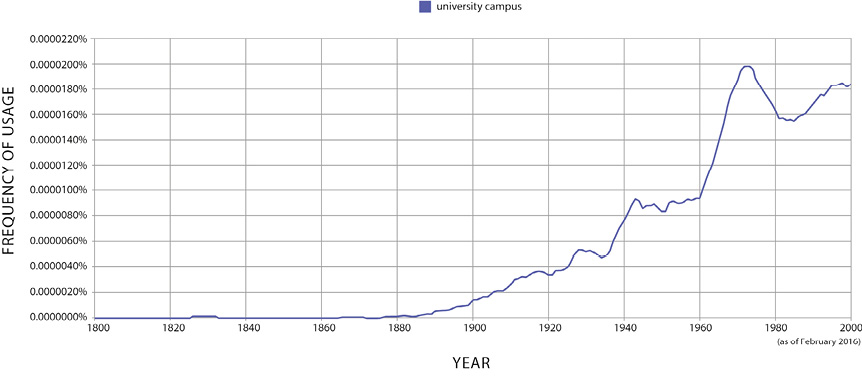

If phrases were stocks that could be traded on Wall Street, the up-and-coming blue chip to buy these days would be “corporate campus” (see Fig. 5.4). By comparison, the future growth of “college campus” (see Fig. 5.5) and “university campus” (see Fig. 5.6) does not promise to be robust. Put in the sell order—but, come to think of it, the vending has been under way for a long time already. Indeed, the fact that academic campuses must be explicitly marked as such is by itself a sign that the corporate ones have tugged campus away from the exclusive purview of institutions of higher learning.

Fig. 5.4 Google Ngram data for “corporate campus.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.5 Google Ngram data for “college campus.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.6 Google Ngram data for “university campus.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

The fiery oratory of Gropius’s groupies did a disservice. They knew full well that no tower was ever built one hundred percent of ivory, but they pounced upon the image with all the might they could muster. What has abided in some design schools is the legacy of their master’s argumentative ahistoricism, which led him initially to oppose even highly successful courses on the history of architecture. He made a concerted effort to delegitimize historicism. Why not live and let live?

To transition from theory to practice, the edifices Gropius himself dreamed up (since even modern men who swing have their daydreams) have not all stood up well to time. The inhabitants and users of what he and his adherents erected could best compute the success of the so-called Gropius complex, on behalf of which its chief proponent polemicized explicitly against collegiate Gothic. The erstwhile Harkness Commons and the Graduate Center at Harvard have their deserved nostalgists, as most any style could and should (even brutalism has its aficionados), but where are the postcards? If the buildings suffered destruction, would they be rebuilt painstakingly at immense expense out of nostalgia decades later, as the Gothic revival tower of Memorial Hall was reconstructed in 1999 after having burnt down in 1956? A search in collectibles that focuses on Harkness Commons nets thin results in comparison with the other construction. To all appearances, not too many people have wanted to revive or share the sight of the first, whereas multitudes have been sweet on the second.

In the United States, the Gothic revival does not really merit the prefix re-. Precious few monuments in the original style existed, and those that did were such belated manifestations of the architecture as to stretch the limits of the word “original.” The advent was effectively an arrival. The manner, particularly in the collegiate vein, was an innovation that brought with it resonances of many virtues, such as faith, peace, strength, order, placidity, learning, creativity, devotion, munificence, and more. Paradoxically, in America universities as institutions have become wedded to conglomerates and government far more closely than they were when the pelf of robber barons poured into their cashboxes, and when a head of higher learning was not disqualified de facto from becoming commander in chief of the nation.

Just as individual artists do, so periods create their own antecedents, changing both themselves and those very models in the process. In the mid-twentieth century, the whole medieval era could have seemed paradigmatic. Take by way of illustration an issue of Life magazine from 1947, where a photographic essay on “The Middle Ages” presented as one of eight headings “The Cult of Mary,” adding “the virgin mother was a symbol of love, and heroine of legends like ‘The Juggler.’” In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, whether rightly or wrongly, these long-ago centuries were regarded yearnfully. Through sheer strength of conviction, the period held out a stability to be regained by a world that had fallen apart. Remember Le Corbusier’s reflection in When the Cathedrals Were White: “Middle Ages? That is where we are today: the world to be put in order, to be put in order on piles of debris, as was done once before on the debris of antiquity, when the cathedrals were white.” The interpretative corollary to this perspective remained current into the 1960s, when an anthologist presenting Anatole France’s adaptation saw the earliest attestation of the jongleur story as a testimony to “the intense and simple faith of the Middle Ages.”

The medieval tale of the juggler or its close modern French relatives commanded canonical status for at least a half century, particularly in France, England, and the United States. In one revelatory development in America, the miracle was included in a 1956 volume that eventually evolved into the long-lived and big-selling Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces. Yet the selection was not to retain its privileged niche forever. By the turn of the century, it had been expelled from the compendium. Could the sunniness and simplicity of the story have made it a foreign body that had to be dislodged?

The heavy commercialization of Our Lady’s Tumbler and its descendants in the mid-twentieth century seems to have rendered the narrative too well known. In fact, its ubiquitousness in the 1950s may have contributed to its first causing disaffection, or at best a reaction of “ho-hum” or “same old, same old.” Later it became virtually quarantined in children’s publications and religious literature. Nowadays, unlike fifty years or more ago, few adults appear to have encountered either the account from the thirteenth century or any of its reformulations since the late nineteenth century. Those who do know the story have become familiar with it through books for young readers, the titles of which often camouflage the juggler or jongleur and even more frequently the Virgin Mary.

The Tumbler’s Tumble

Individuals matter. In the trajectory of the tumbler, a few specific ones stand out for their contributions. The unknown medieval poet should be lauded as the first. Next we have Gaston Paris, charismatic communicator. Third in line would be Anatole France, urbane ironist. After him, Jules Massenet, glossy music maker, made an intense but short-lived mark. Mary Garden deserves as much credit as any modern for product development and marketing. Yet for even great women and men to work their magic, the surrounding context has to be sympathetic and receptive. Blechman’s and Auden’s minor masterworks have been sand castles in the face of a storm surge that has eroded the former salience of the Middle Ages and such tales as this one. Why the washout?

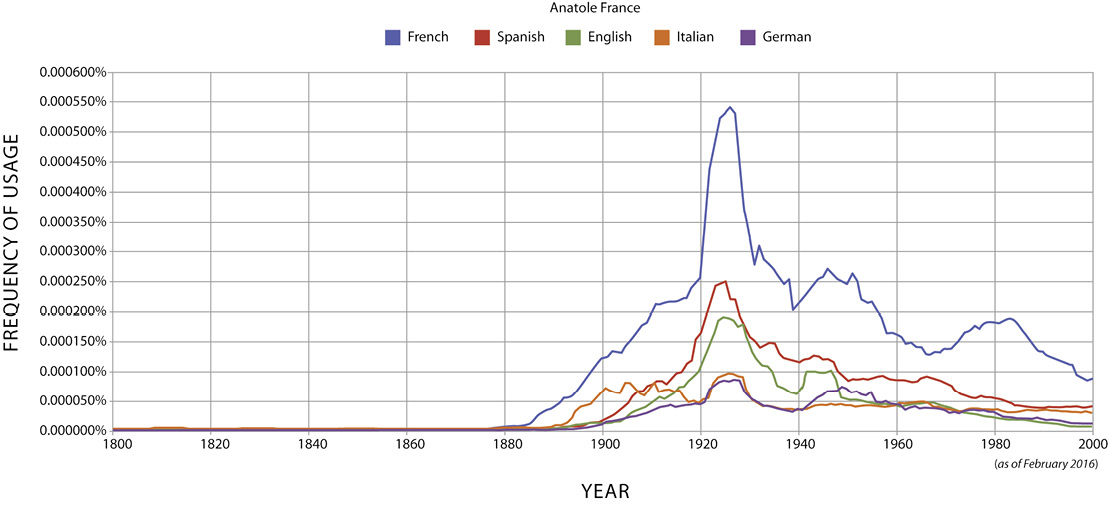

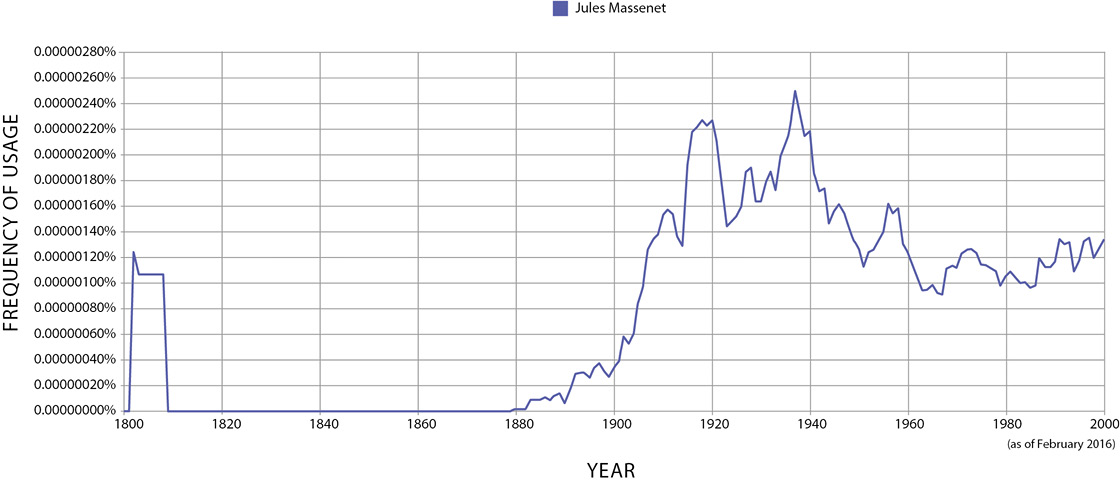

Not all Nobel prize winners withstand the onrush of time. That said, Anatole France lost ground or altitude with dizzying rapidity. His name recognition has dropped precipitously and perpendicularly (see Fig. 5.7). Among the musically inclined, Jules Massenet’s reputation has suffered a devaluation as vertiginous as Anatole France’s (see Fig. 5.8). Outside the inner circle of opera aficionados, the three-act “miracle” from 1902 rates as little more than a men-only oddity. Le jongleur de Notre Dame retained just enough cultural traction late into the twentieth century that in 1981 the avant-gardist Laurie Anderson would not only dedicate her song “O Superman” to Massenet, but even slip into it lyrics that parody an aria from the opera. When the musical drama of the early twentieth-century composer has been revived, it has been greeted with good-humored favor by connoisseurs, but for all that, each revival has the look of an atypical and temporary occurrence.

Fig. 5.7 Google Ngram data for “Anatole France” in five languages. Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.8 Google Ngram data for “Jules Massenet” in English. Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

In American culture, Henry Adams remains a name to conjure with, but far more as a figure of biographical interest, and to a slighter extent as a US historian, than as a medievalist. Tellingly, the chapter of his Mont Saint Michel and Chartres that leads the reader learnedly from Gautier de Coinci, and what Gaston Paris made of him, all the way to Our Lady’s Tumbler was spotlighted as a case study in Paul Haines’s Problems in Prose. From 1938 through 1963, this volume delivered yeoman’s service to students taking college courses in English composition. By its final printing, the tale had suffered a pratfall in its ranking and lost its charm. In a fit of housecleaning, the editor went so far as to excise this extract with no comment beyond the perfunctory “several of the less rewarding essays have been dropped.” Speak no ill of the dead.

For fifty years or so in the mid-twentieth century, both Adams’s Education and his Mont Saint Michel and Chartres were treated, perhaps bizarrely, as literature. Now their time in the public eye clicked past its expiration date. At the same instant, Our Lady’s Tumbler fell from grace. The thumbnail exemplum boasts a theme that could enthuse equally the religious and the hedonistic: joy. Yet this version has never made much headway in achieving recognition. In contrast, the French poem from a few decades earlier in the thirteenth century has a pronounced penitential element—not a strong selling point in a world unsold on penance. Whatever the reasons, the tale’s glory years had deteriorated into an early development of grunge by the 1960s. Yet from its fame of over a century, echoes from the medieval story and its adaptation by Anatole France reverberate that are still perceivable even today. The narrative entitled “Anonymous, ‘The Tumbler of Our Lady’” is incorporated in a 2008 compendium on The Joy of Reading.

The only genre to which narratives of short length lend themselves easily is the children’s book. A familiar pattern takes shape: literature for young audiences, along with religious instruction, is the venue where the medieval miracle is likeliest to thrive right now. The tale has sometimes been shaped for youths with the lesson that even if a person’s size and skills are average at best, what counts is to put forth one’s best effort in the proper spirit. The story of the tumbler has been expounded as emphasizing above all the signal that under the right circumstances, individuals with uneventful lives and without incredible talents can outdo those who possess “special professional or social status.” God, or at least not mere mortals and human beings, decrees which devotees have a right to recognition. The account gives people courage, even or particularly those who perceive themselves as having middling ability or less. Take Julie Harris (see Fig. 5.9). The American stage personality first acted the juggler when she was fourteen, in her school’s Christmas play in the late 1930s. Eventually highly successful on screen, she loved the fiction and found that it perked her up first when she most doubted her own abilities.

Fig. 5.9 Julie Harris. Photograph by ABC Television, 1973, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Julie_Harris_1973.JPG

What was the original floor show like, as described in Our Lady’s Tumbler? To be forthright, we do not know ourselves how properly or poorly the jongleur executed it. The compassion of the Virgin may have been prompted by his stamina and sincerity rather than by his virtuosity. Furthermore, her gesture of ventilation may well have been meant as much to telegraph a communiqué to his fault-finding fellow Cistercians as to provide calmative care to the jongleur himself. Now and again artists who have conceded that their talents have severe limits and their performances serious flaws have taken solace in the story and have pledged themselves to it. The tale has given hope to the mediocre.

Then again, the responsibility for the neglect of Our Lady’s Tumbler and The Juggler of Notre-Dame may lie with its potential audience. Already in 1951, a Hungarian-American comparatist subsumed the narrative among other gems of poetry and prose that belonged to what he called “world literature.” At the time, that final term pertained first and foremost to texts that were regarded then as chefs-d’oeuvre of the European canon. Dashes of Russian and American could be injected for extra tang. So the mid-twentieth-century professor ranked Our Lady’s Tumbler alongside Dante’s Divine Comedy, Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, François Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Molière’s Tartuffe, Goethe’s Faust, Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, and Melville’s Moby Dick. If these masterpieces were deemed worthy of being appreciated all over the earth, anyplace outside the Western world qualified as extraterrestrial. Despite the high standing this champion of global literature accorded to the story of the tumbler, he saw arts and letters in his day as having been at least partially commercialized, and some of its potential readers as succumbing to “the reluctance or incapacity of searching for a deeper meaning in the printed word.” He is lucky not to be measuring the quality of reading today. Furthermore, he presented the jongleur in our miracle as distinct from the other heroes in his must-read list. Despite weighing in unwafflingly about Dante, Don Quixote, and Hamlet, he discoursed with more distance about “a medieval conte dévot such as The Tumbler of Our Lady.” In the process, he made the tale seem special, while concomitantly generic.

The English translations in the second half of the twentieth century contributed nothing to making the medieval story accessible to a broader readership. On the contrary, they helped to corroborate the impression that it was rarefied—that its rightful place was to be stowed in the icy-cold vaults of scholarship rather than nestled in the fond hands of general readers. In none of these forms could the versions be expected to reach a wide audience. The greatest hope for the narrative’s propagation across social classes and throughout the world lies in the spate of retellings that has gushed forth in poetry, prose, drama, musicals, music, opera, and other genres. Thanks to the infiniteness of human imagination, not even the shortest among all the rewritings I have encountered has not added an unheard of wrinkle or two to the corrugations already there, often without any apparent intent to innovate.

The authors of children’s picture books and religious manuals have demonstrated an affection for reworking the tale. Such adaptations have carried the narrative, like a Gospel on a humble scale, to all four points of the compass and all five continents. In Russia, the juggler’s story was recounted in a short verse narrative by the poet Galina Gordeeva in 2006. The title can be translated as “The Juggler of the Mother of God,” the words by which both the short story and the opera have been known in the Russian language. No doubt other twentieth-century versions also exist in the Slavic world. The medieval poem from the thirteenth century may have had resonance among Slavs because of interest in “fools of God.” During the Soviet era, the tumbler’s lay status and the “moral of the story” that showed him prevailing over the church hierarchy could have been appealing. Additionally, Anatole France was a revered author, whose writings carried special weight because he had been a bulwark for the Bolshevik cause in the early years of the Soviet Union. Among communist literati, he may have been the foremost French author. His Little Box of Mother-of-Pearl was put into Russian repeatedly, with spikes in the first decade of the 1920s, and in the 1950s: “Rarely is a work of prose translated into a foreign language so many times and under such different circumstances.” Of the fictions contained in this jewel box of narratives, the tale of the juggler was one of the two most well-liked: it was rendered at least sixteen times into Russian.

The movement of the story may not have been universal, but it was transglobal. Owing to the prestige of French in Japanese culture in the early 1900s, Anatole France became well known there already during his heyday, and all his novels were put into the language at that time. But his version of the jongleur attracted no special notice. Through children’s and religious literature, the miracle has permeated East and Southeast Asia. In the Philippines Catholicism dotes on the Virgin Mary, and local dance traditions may involve saints. Korea too has a sizable Christian population, around half of which is Catholic. The children’s books that have lugged the lead character to such eastern countries have been mostly illustrated ones in translation that originated in European countries or the United States.

In the Southern Hemisphere the account has so far put down nothing but a footprint upon beach sand. In Chile, a transient Spanish exile pieced together the text for a children’s book, while a native of his land who has remained Chilean for the balance of her life embellished it. Two decades later, a composer born in the same South American country flew home for performances of a ballet that he composed in the United States. In Brazilian fiction, an author recapitulated the account en passant in a fiction. In cultures interlaced with the original Gothic and its revivals in Britain through the Empire, many more examples are likely to be discoverable. In South Africa, a ballet was danced long before the dissolution of apartheid. Australia, home to much Gothic, has literary and musical treatments of the tale in various genres.

Michel Zink Reminds France

The age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever.

—Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

Edmund Burke, stalwart proponent of the beautiful and the sublime and latter-day exponent of knightly nobility and the Middle Ages, commented thus as he reflected upon the sequelae of the French Revolution. Has history repeated itself? By extension, should we arrange the exequies for the juggler and pronounce a funeral oration over this charismatic character, who took France by storm not even a hundred years after the Irish statesman scratched his quill across paper, but who may now be cascading (or tumbling) from his one-time popularity? An optimistic diagnosis would be that the miracle, in spite of and because of its brevity, has an elasticity that may stop it from ever completely expiring, however moribund the humdrumness of most versions retailed in the mid-twentieth-century cultural market may have left it. Chivalric days may be long gone, but the lay brother has not breathed his last.

The elementarity of the story is one of its captivating qualities. The narrative can be readapted effortlessly from the tiniest concentration of words that a person has read. It resembles a bouillon cube that can be reconstituted into broth. Such regeneration was the plan for the exemplum in the Middle Ages: that was the whole idea behind the genre. The same sort of reconstruction recurred centuries later, when Anatole France composed his short story after happening upon a fleeting recapitulation by Gaston Paris. Exceedingly few elements are required to regrow, in ever-shifting ways, the quintessential contours of the tale—and mutations, deliberate or accidental, are not inevitably for the worse. The haziest remembrance of hearing or seeing a performance in the past may lead to a new and even better presentation.

For much of its history in the twentieth and now twenty-first centuries, the story has evinced a knack for being constantly recreated by scholars and artists. Many recreators have set great store by the unmerited fantasy that they have been doing something epoch-making by reshaping the tale, and they have found creative satisfaction in their creation (which has been unwitting recreation). In effect, the narrative has derived authority from its seeming venerability. Along the way, it has afforded the illusion of being a once-in-a-lifetime discovery to many who have bumped into it and chosen to retell or illustrate it.

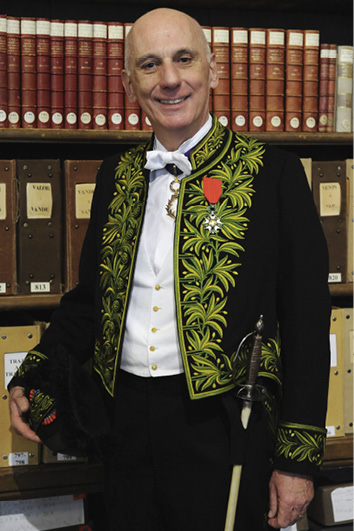

Early in the twenty-first century, the legend may enjoy its healthiest reception in two places. One is France. Contrary to the proverbial wisdom that a prophet is not appreciated in his own country, the jongleur has held his own in his native land. If so, his obstinate continuance there owes to Michel Zink. As both a highly respected scholar of medieval French literature and a well-known writer of modern French fiction, this dual-threat man of letters (see Fig. 5.10) has perpetuated the best of what Romance philology incarnated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Gaston Paris would be very contented. As it happens, the nineteenth- and twentieth-century Frenchmen share major credentials. Like his predecessor of more than a century ago, Zink holds the seat for the literatures of medieval France at the Collège de France; co-owns responsibility for the journal of Romance philology, Romania; and has demonstrated a can-do keenness to traverse not only the lofty byways of erudition but so too the more busily traveled highways of pop culture.

Fig. 5.10 Michel Zink, secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, an immortel of the Académie française. Photographer: Brigitte Eymann. Copyright Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Paris. All rights reserved.

The littérateur has touched upon the French original from the Middle Ages in several of his own monographs. Outside his scholarship, in 1999 (see Fig. 5.11), he gave broad currency to thirty-five medieval pious tales that contend with preoccupations of Christian faith, by overhauling them in soignée but accessible French prose. As the eighth among these hagiographic naratives and miracles of the Virgin, he presented “Le jongleur de Notre Dame.” He commenced the four printed sides of text with the well-worn fairy-tale exordium: “Once upon a time.” The phrase features as the stock opening for all the fictions in the collection. The children’s story author Violet Moore Higgins employed this same rhetorical technique in the corresponding English in her 1917 book.

Fig. 5.11 Front cover of Michel Zink, Le jongleur de Notre Dame: Contes chrétiens du Moyen Âge (Paris: Seuil, 1999). Image courtesy of Seuil. All rights reserved.

The present-day French belletrist stringently simplifies the story. In his portrayal, the jongleur takes the shortcut of dancing just one time, not repeatedly. He does his act for the infant Jesus, not for the Virgin. The narrative reaches its meridian when the statue of Mary leans down and uses her veil, with motherly love, to wipe the sweat-sodden brow of the dancer when he has sat down out of exhaustion. The narrative thrift finds its stylistic match. The author himself describes the style as being simple, in imitation of medieval tales themselves, to give “an impression of unaffected limpidity and of unreserved adherence to the tale and its lesson.” Of course, the person who wrote the story has at least some license to give it window dressing, here through a tumbler-like humility. He also declares: “The Jongleur of Notre Dame is not the best of my tales. It is strongly didactic.” Others might beg to differ.

The professional philologist and the public popularizer meet when Zink intercalates into his retelling, in modern French translation, a long quotation from Saint Bernard. The invocation of the doctor mellifluus has its scholarly backdrop in Zink’s broad view of the relationship between poetry and conversion in the Middle Ages. One chapter of his book-length study on the topic, in 2003, dealt with the conception of the “jongleur of God,” which he traced from the biblical David down to Saint Bernard. He explored the seemingly irreconcilable range of reputations attached to the figure of the jongleur during the medieval period. In discussing Our Lady’s Tumbler, he coordinates it with the tale “Fool” in the Life of the Fathers. In both narratives, the onlookers fail to recognize or appreciate the wisdom of a seemingly silly person, and instead are misled by his ostensible folly into disapproving his performance.

In recapitulating the account of the jongleur, Zink owed an unmistakable debt to Anatole France, to whom he has resorted on many other occasions, without making a secret of his dependence. Beyond the Nobel laureate, the reteller placed himself squarely in a French academic tradition—a sidebranch of philology—that Joseph Bédier (see Fig. 5.12) had plotted out and laid down in modernizations of Old French romances published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At Bédier’s behest the Tharauds had gathered Marian miracles—narratives in which the Virgin interposes herself in human affairs. The connection between the philologist and the brothers went beyond the mere casual, since Jérôme Tharaud when elected to the French Academy in 1938 assumed the chair that had belonged to Bédier. His brother Jean also became an Academician, as a member of the academy is called, in 1946.

Fig. 5.12 Joseph Bédier. Photographer unknown, 1920s, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joseph_Bedier.jpg

Zink’s endeavor to perpetuate Le jongleur de Notre Dame before a larger audience by highlighting it as the title story met with mixed success. In 2002, fourteen of the thirty-five tales in his 1999 collection were reprinted under the reduced and de-Christianized name Tales of the Middle Ages. This time the narratives were brought out, with illustrations, in a series destined for readers (or listeners?) six years and older, whereas earlier as far as one can judge they had been pitched at adults. Unaccountably, the miracle of the jongleur was omitted. Outside France, the transmission of this volume may owe something to caprice. The book has been translated into Spanish, Czech, and Italian, though not yet into English or German.

2002 was a banner year for Le jongleur de Notre Dame in French. Fifty years after its first appearance, R. O. Blechman’s Juggler of Our Lady was released in France for a young readership under the imprint Gallimard Jeunesse. Was it, like Zink’s tale, being implicitly made infantile or at least juvenilized? Contradictorily, this edition of the critics’ favorite from 1952 purveys by way of appendix a “bio-graphic” dossier to convey the spectrum of its author’s work—a gallery that would be appreciated much more by adults than juveniles.

We All Need the Middle Ages

I would not like to live in a world without cathedrals. I need the luster of their windows, their cool stillness, their imperious silence. I need the deluge of the organ and the sacred devotion of praying people. I need the holiness of words, the grandeur of great poetry.

—Pascal Mercier, Night Train to Lisbon

Whether we like it or not, there is no “pure” medieval; there is only medievalism.

If commercialism must be dueled in the market, the juggler may be overdue a new advertising campaign to publicize his aptitudes and appeals. Massenet may have done the right thing by puffing the liqueur Bénédictine. By taking on that promotion, he helped to keep before the public not only himself but also his Jean. Furthermore, the jongleur himself bears no small resemblance to such an after-dinner restorative, since he proffers a pleasure that everyone should experience at least once but not necessarily indulge incessantly.

A taxing trick for authors, and not just of literature but of scholarship too, will be to keep the story in the foreground of the here and now while also not violating the medievalness that belongs to its inmost fiber. It may afford a degree of consolation and even a fount of inspiration to recognize the long view. The present sort of study helps to make evident that mediating between the medieval past and the modern present has for many scores of years been complex and difficult but rewarding. This tunneling should also remind us that the texts of yore require a brain trust, such as philologists, literary historians, critics, and historians, who can discover, reconstitute, and interpret them. Those gurus, mostly in the groves of academe, rely for their education and employment upon the support of the societies and cultures that encircle them. In return, they have an obligation to repay the favor by bringing forth whatever in history and story can enlighten, entertain, and electrify all the audiences they can reach. To be relevant, nonfiction and fiction do not have to be determinative. They contribute more than enough by merely increasing the stock of wisdom and beauty upon which we may draw. We require all the reenchantment we can get.

From the millennium or so that constitutes the Middle Ages derives a large part, even the lion’s share, of what civilization remains even today in Europe and North America. Consequently, we will fail to fathom ourselves as we are if we shy away from looking back at our earlier selves. Not to take part in cultural retrospection (and it need not all be rosy) is nearsightedness that coincides with narrow-mindedness. For a culture not to know the past out of which it has grown is chrono-narcissicism. Like all manifestations of exaggerated self-love, it lays down a minefield that is dangerous not only for the narcissist but also for the innocent bystanders.

When change occurs at a rapid clip, the past can serve not only as a distraction or a safe haven, but also as an orientation point. More than just the Middle Ages, we should take stock of later images of the period, which we often encounter even before we brush against its own realities. To have the measure of that long-ago era, we have to tackle not only those centuries themselves, but also the recent ones that have most informed our own presuppositions about it. We must come to terms with the revivals and reenactments we tag as medievalisms, as well as with the medieval itself.

This book has not taken us on a clandestine or quixotic quest to reimpose a pastel-painted past. First, such a retrograde endeavor would be unprofitable: there is no going back. An adage counsels “Go with the times, or with time you will go.” In a larger sense, reinstituting the Middle Ages would be unwarranted, since they never disappeared. A surprise is how much that was felt to be (and sometimes was indeed) European and medieval took deep root across the Atlantic from Europe itself. The remains of these implantings—what I have christened the American Middle Ages—should prompt us at least now and again to reflect on the medieval period itself in all its exuberant and extravagant heterogeneity. The thousand years of this epoch remain so well bedded that its survivals are anything but deadwood. They live on. In doing so, they evolve. We should reflect also on how the last few centuries have pruned those original times to suit their needs, desires, and prejudices, and how the histories, presents, and futures of old and new worlds have been grafted together.

For a decade, I have luxuriated intermittently in immersing myself in the origins and reception of this story. The glee has made me perceive how I fell in love long ago not just, and not just directly, with the Middle Ages. Rather, I became enamored also through, and with, layers of medievalism that have laminated the medieval period. As when watching a statue mature through exposure to oxygen, we behold these coatings not as defacements but as enhancements. Our liking for the immutable radiance of gold, and our distaste for the darkening disfigurement of tarnish on silver, should not impede us from esteeming the process by which the natural red of copper patinates into verdigris.

In the last words of Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, Henry Adams left his readers with cold comfort. He maintained that the early twentieth century had forgone unity for multiplicity, faith in the Virgin for the technology of dynamos. The onetime historian arrived at his disaffection fair and square. For all his endless talents and achievements, he never latched onto a calling that would measure up to the presidential past of his storied family. A New England patrician, he forsook his native region and birthright for Washington. An intellectual of the first order, he turned his back on a professorship at the most highly rated American university of his day, biding his time for a form of recognition that would and could never come, a summons to become the sage laureate of the nation, éminence grise of chief executives in the US, or doyen of an as-yet uninvented profession––official public intellectual. He craved success by penning novels that he kept steadfastly anonymous, and he sought romance with an unattainable, or at least in his case unattained, younger married woman.

In 1919 Cram, the architect and Goth par excellence, had Adams’s book reprinted for distribution to a much larger readership than it had reached in two infinitesimal private releases. He retailed collegiate Gothic architecture as a palliative for modernity, and he raised stout stone monasteries to house the future elite of America’s military at West Point, and the crème de la crème of its leading families at other educational institutions throughout the country. None of this construction could hold off the Depression, ward off a Second World War, or keep tranquil any of the hornet’s nests that lay ahead to be stirred. The Middle Ages could not repair all the drawbacks that Adams and Cram detected in their world and in themselves. More than one iteration of the Gothic revival took as its founding principle the urgency of contesting mind-numbing and heart-chilling technology. Out of the same necessity, we might consider administering ourselves a dram of Gothicism—but new and improved.

The Simplicity of Atonement

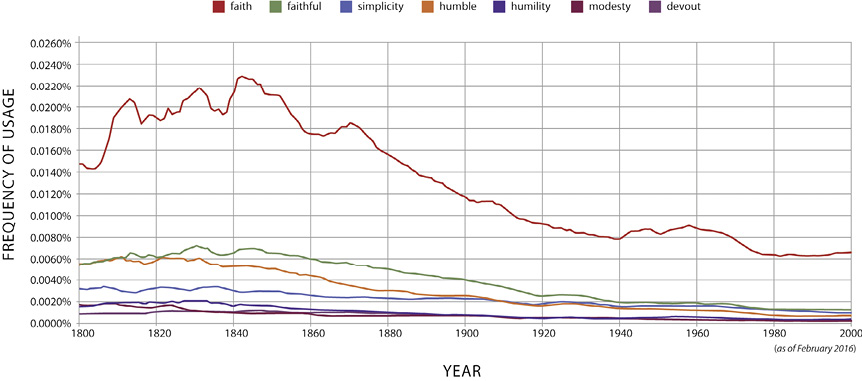

The fate of the story about the jongleur changes from year too year, from place to place, and from artist to artist. The tale acts as a litmus test that affords insight into the state of the cultures in which it has been received. The analytic holds valid less for the nature and degree of nostalgia in any given time and place than for cultural openness to a humble hero. An earlier chapter of this book contained a graph to present the drop in the relative frequency of the words devout, faith, faithful, humble, humility, modesty, and simplicity (see Fig. 5.13). All of these adjectives and nouns belong to the word cloud that cloaks the juggler, like a Greco-Roman god.

Fig. 5.13 Google Ngram data for qualities once thought to be characteristic of medieval people, showing a steady decline in frequency since 1850. Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

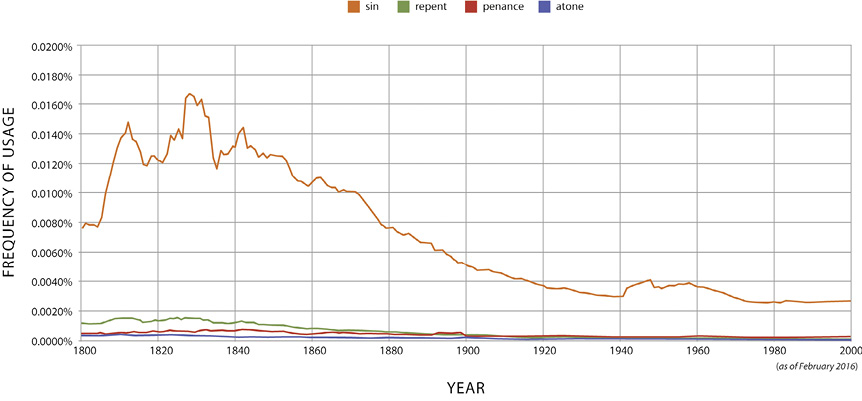

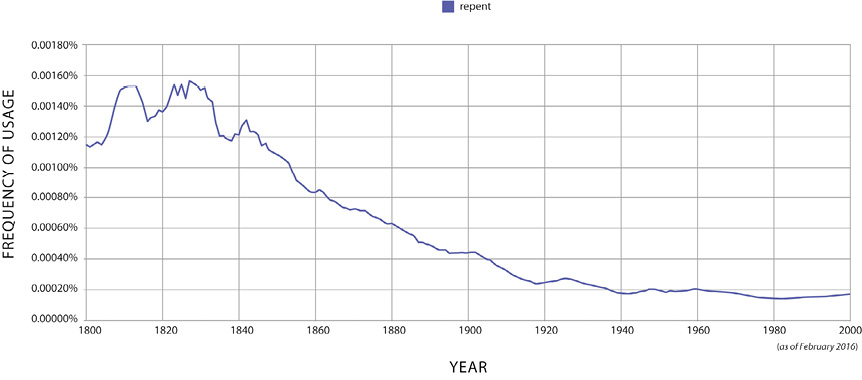

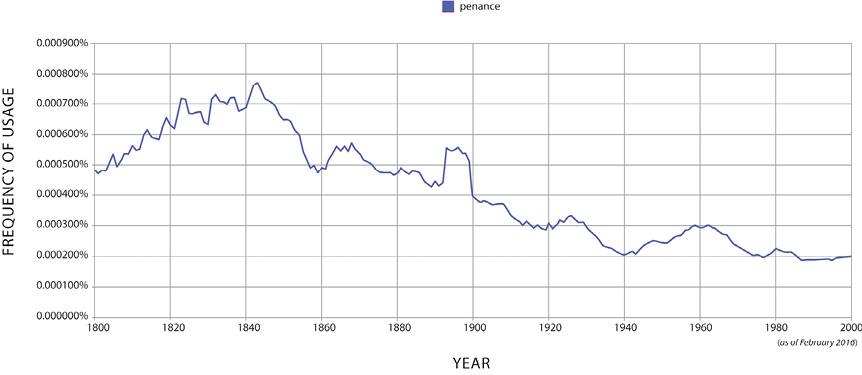

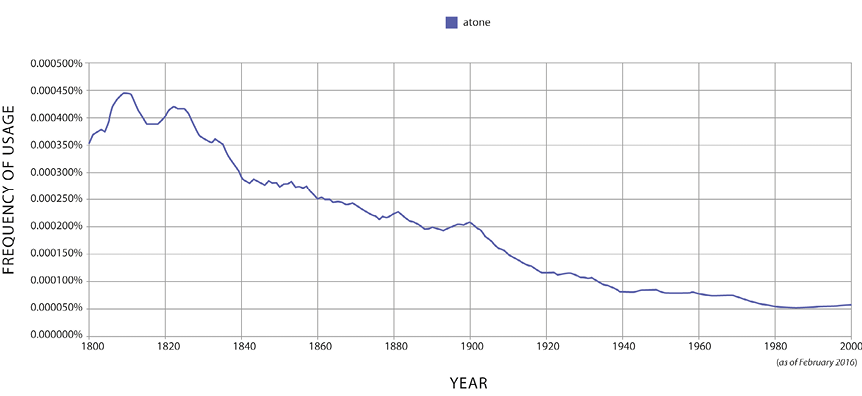

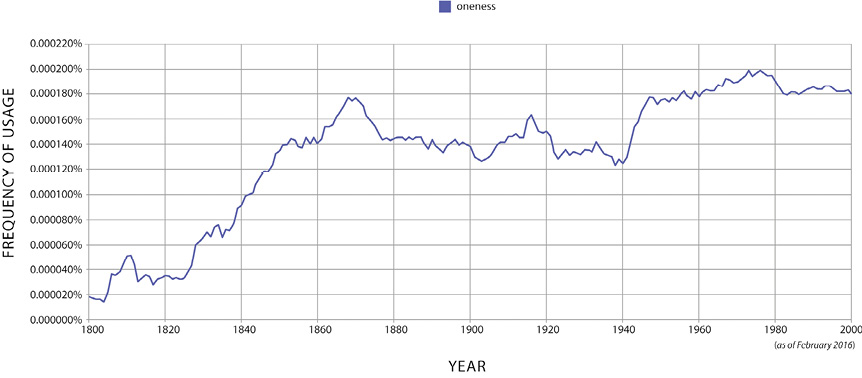

The simplicity of the performer relates inextricably to the real or perceived sins for which he repents. This simple quality implies singleness, just as the etymology of monk gets at the idea of oneness. By the same token, penance is tied to atonement. Such reparation has encoded within it the notion of being at one with God. “At-one-ment” is a bona fide etymology, not a bon mot. All the key words and concepts italicized have seen relative declines in their usage (see Figs. 5.14–5.17).

Fig. 5.14 Google Ngram data for “atone,” “penance,” “repent,” and “sin.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.15 Google Ngram data for “repent.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.16 Google Ngram data for “penance.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.17 Google Ngram data for “atone.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

For whatever reasons, we have ceased to operate within a substructure of sinfulness: we have become unrepentant or at least uninterested in repenting and atoning. The outlier, unsurprisingly, is the unitalicized oneness (see Fig. 5.18), which brings us back appropriately to the square one of simplicity.

Fig. 5.18 Google Ngram data for “oneness.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

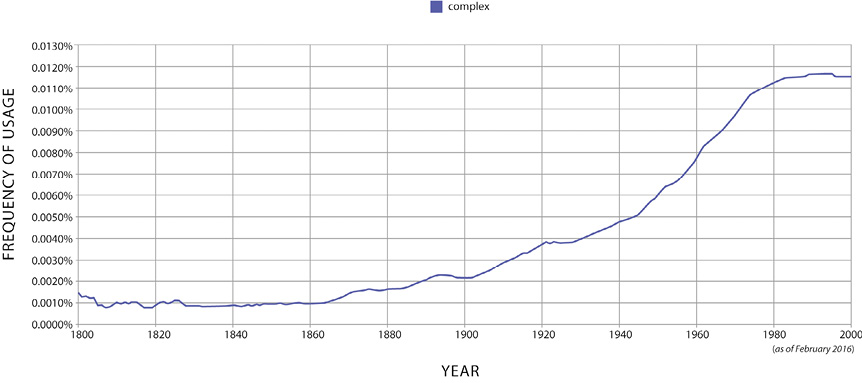

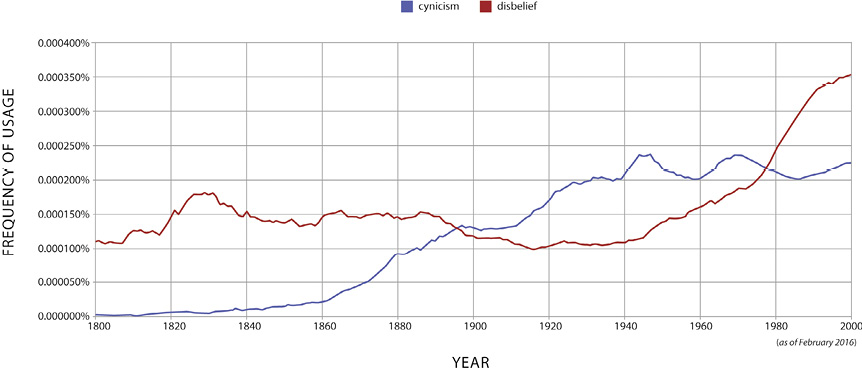

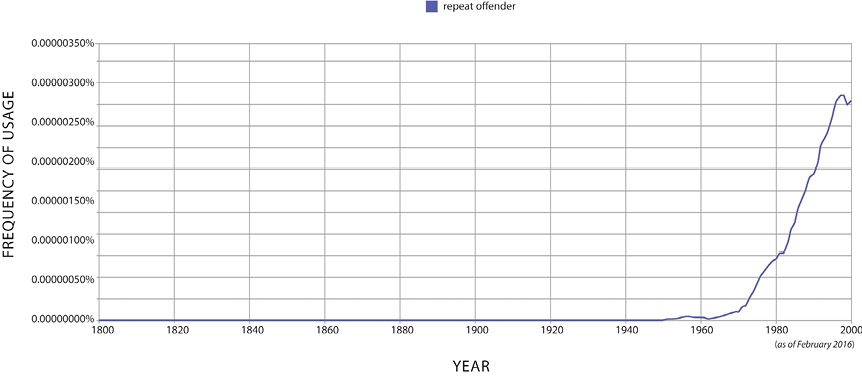

We have become more caught up in efforts to represent and analyze experience through algorithms in facts and figures—as confirmed by my readiness to regale you, dear reader, with graphs. But as the stock phrase runs, statistics can be made to prove anything. Figures, even human ones, can be manipulated, massaged, and twisted to all sorts of ends. We could frame overly simple or even simplistic arguments about the simplicity of yore in contrast to the complexity (or at least the supposed complexity) of today (see Fig. 5.19), or about the full-hearted faith of the past against the eye-rolling disbelief and hard-boiled cynicism of nowadays (see Fig. 5.20). O ye of little faith. The penitent could be argued to have lost ground to his opposite, the repeat offender or recidivist (see Fig. 5.21). Epiphanies emerge through sifting such numerical data, but future philologists (a band first envisaged by Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff and Friedrich Nietzsche) must tread warily before allowing themselves to make fast-talking generalizations on the grounds of the computational hardware and software that have become widely available.

Fig. 5.19 Google Ngram data for “complex.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.20 Google Ngram data for “cynicism” and “disbelief.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.21 Google Ngram data for “repeat offender.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

A decade ago I began bandying emails back and forth with Barnaby Porter. His mother Barbara Cooney, illustrator and author of children’s books, had decided even before his conception to name her firstborn male child after the protagonist in Anatole France’s Le jongleur de Notre Dame, since she had fallen in love with the story. Her son, no longer a boy on the outside (but he sounded young on the inside), asked me at the end of our heart-to-heart what the narrative truly meant, and we swapped letters again on the topic much more recently too. All these pages are my rejoinder, at least for now. But let me explain my drift less coyly.

Through this book I aspire (a great verb for its serendipitous connection with Gothic steeples), as any person committed wholeheartedly to the humanities would do, to have contributed to the unending process of interpretation and recreation. My hope is that many more people will feel encouraged to come to grips with the significance of the tale and uncover verities that have eluded me, even if those truths have not escaped some of the more masterly minds than mine that have chosen to dance, juggle, sing, or play with the jongleur.

Individuals have made a stunning variety of this not-so-simply simple narrative. The multifariousness stands as a testament to the infinite inventiveness of the human mind. The medieval poem, Anatole France’s story, Jules Massenet’s opera, Mary Garden’s co-option of the lead, R. O. Blechman’s cartoon, and W. H. Auden’s ballad, all in their supremely idiosyncratic manners, will energize readers to retell and recompose the tale afresh. Furthermore, each of these resourceful souls has demonstrated to the empirically minded that whenever the novelty of the tale palled, an individual talent could rescue it. They have done their job so well that the reception of Our Lady’s Tumbler could be construed as an oddly underappreciated narrative feast or famine.

In odd and obstinate ways, the miracle resembles at its core the itinerant entertainer who plays its protagonist. It wanders through time and space, stopping in this or that culture until its performance becomes too routine and its audience jaded, passing on to the next, sometimes receding from view, only eventually to reemerge. The humble hero of this pious account has won the hearts of Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and agnostics, and nothing presupposes that his appeal must be restricted to those faiths. In an interview about her poetry and thought, the contemporary American poet Mary Rose O’Reilley adduced the juggler in a context that merits more than a fleeting look. Her spiritual background was eclectic, to say the least, since she was raised Catholic, became a practicing Quaker, developed a long passion for yoga, and grew curious ultimately about Buddhism and much more. In an interview in 2007, she first observed that “women of my generation were trained in indirection and self-effacement,” then posited the expedience of differentiating between humility and the pose of being humble, and finally presented her view that by nature poetry constitutes “a device of indirection and self-erasure,” which she set in a framework of Jungian psychology by invoking his concept of the anima. This is the Jung who knew our story well and used it self-defensively, to keep at bay the obligation to interpret unsought and unwanted amateur artworks. At this point O’Reilley’s thoughts turned to our story. Her observations make of the juggler a patron saint, or a role model, who lends himself well to use by women and poets. In the reception of the poem and its adaptations, females have played no small part, but in recent decades they may not have gotten their fair share of attention among those who have reworked the story. Now may be a good time for them too to rethink and remake it.

The exemplum of the minstrel speaks to the potential for goodness in almost all human beings. Henry Adams waxed melancholic about the utility of the Middle Ages to modern man. First he demonstrated that the faith-based anthropocentrism of the medieval period had one uppermost meaning, embodied in Mary. Then he proved that the faith had lost its underpinning and had decayed. Yet the story of the tumbler outlasted Adams, surviving beyond the second half of the twentieth century. So too did his elegiac book. For the better part of a hundred years, it stood the test of time well, at least for an American readership. Its author was wrong to despair about the precariousness of everything medieval, at least where architecture enters the picture.

Gothic churches, college buildings, and skyscrapers manifest themselves across the North American continent with unostentatious omnipresence. Whatever our creeds may be, both the Old and New Worlds owe it to themselves not to be tone-deaf to their native-born cathedral cultures. Neither European countries nor the United States can afford the cost of forgetting their Middle Ages—original or revival. And when remembering, we should not allow antipathetic preconceptions about the period to crowd out memories of purer positives.

After the Second World War, the literary history of the Romance philologists Ernst Robert Curtius and (even more) Erich Auerbach absorbed the Middle Ages with redoubtable resignation and fathomless humanity. By projecting the period in all its incandescence and gloom, they handed on the torch to C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Umberto Eco, and others. Today more than ever we need the cathedrals. Those great churches stretch from the tip-top of the finials of the pinnacles down by way of the gargoyles to the abyss of the subjacent crypts. To sum up the matter with an allusion to Victor Hugo’s novel, we must think of Notre Dame as much as of the hunchback.

It is a woebegone culture that can engage with gusto in the gloating over another’s misfortune that is known in German as Schadenfreude, meaning literally “harm-joy.” Even sadder is if the same society has not even the most unexceptional niche for what we might call by the neologism Freudenfreude, translatable as “joy-joy.” Ours is a time that defaults into disenchantment. A revealing tagline runs: “Happy endings are just stories that haven’t finished yet.” Other ways exist of facing life and literature than with such comedic negativism. With unique charm and beauty, the story of the juggler holds out the hope of redemption to those who may feel rough around the edges or unskilled in offering themselves. It tells of a life that its liver considers wasted, of an at first unfruitful foray and fray to make amends, and of a moment of grace that precipitates redemption at the very end. Even more than promising deliverance, the tale invites us to take joy in our talents, such as they may be. An ode to ordinariness, the narrative speaks to individuals who to others may not seem special, but who have the competence all by themselves to deliver and to attain spiritual satisfaction from the practice of whatever skills they have. Recollect that already in the thirteenth century the medieval exemplum was classified under the heading “Joy.” If lessons can be extracted from the “example,” they are universal. Unless sin disappears, self-questioning about talent vanishes, and the enrapturement of artistic self-expression loses its luster, the juggler will perdure in finding audiences and emulators.

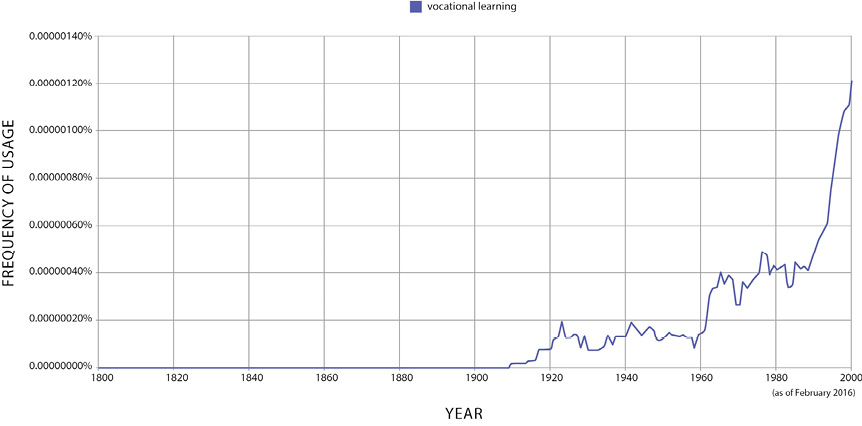

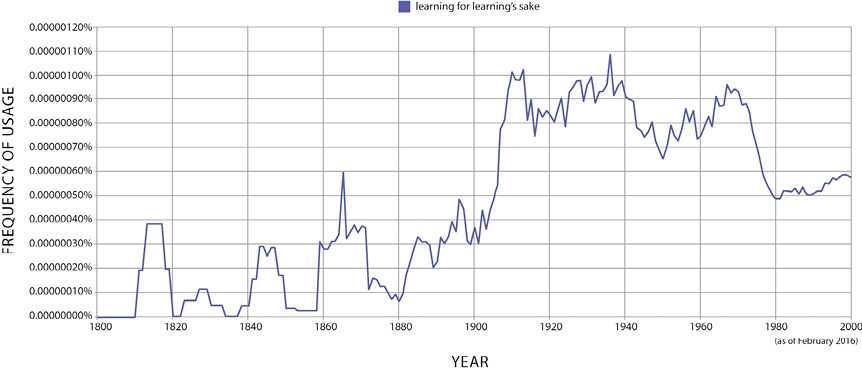

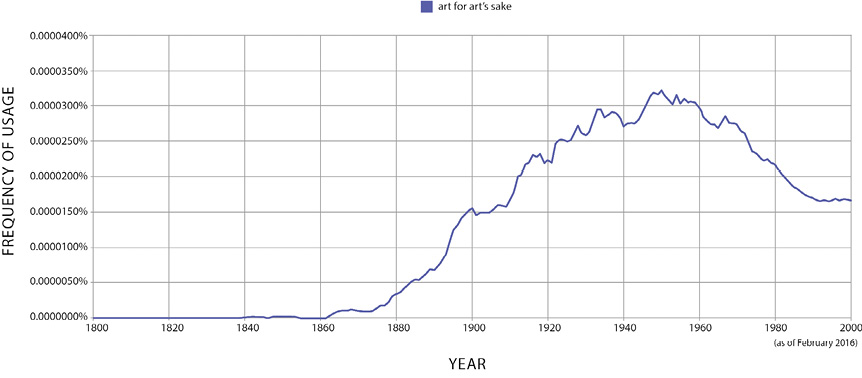

At this moment, many guiding forces in our society emphasize nuts and bolts. In education, the hardnosed considerations take the form of a vocationalism that reposes upon science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, known as STEM for short. The added emphases contribute to a pattern that may limit our attractiveness and competitiveness as a culture and civilization. The soaring stress on vocational learning need not entail automatically an abysmal abandonment of esteem for learning for learning’s sake and art for art’s sake … but the synchronicity of the two patterns is at the least suggestive (see Fig. 5.22–5.24). If we have only STEM, we will have lost STEAM: the arts must be part of our calculation. So too must be the humanities, so let us give the acronym a Yiddish twist: SHTEAM. The resources of these other creative and interpretative endeavors extend to the entire, boundless inventory of positive passions and (yes) products that make cultures distinctive, balance work with pleasure, and on the whole suffuse life with significance. One proclamation in a sociology book that I have read and reread, perhaps still without comprehending it fully, seems to make a related suggestion, as a counterweight to an overemphasis on practicality: “There is the old legend of the ‘jongleur de Notre Dame’ who made acrobatics an instrument of Worship. All teachers of ‘practical arts’ ought to keep this in mind.”

Fig. 5.22 Google Ngram data for “vocational learning.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.23 Google Ngram data for “learning for learning’s sake.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.24 Google Ngram data for “art for art’s sake.” Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

The last several decades, and especially the one of engagement with this narrative, have been for me positively medieval: end of story. A couple of decades ago it was posited that thanks to the advent of literary theory and a subsequent methodological eclecticism, medieval studies had undergone a renaissance. In my view, the rebirth will have taken place when we can say with a straight face that the field has undergone a Middle Ages, by which we will mean an affirmative transition rather than at best a neutral hiatus between two phases of cultural achievement that are held to be far greater. Above all, let us have faith: the juggler will not rest on his laurels for long. In the words of T. S. Eliot,

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

***

Welcome to your destination, ladies and gentlemen. The safest part of your journey has come to an end.

—Announcement to passengers reputedly made by pilots at the end of commercial air flights