1. The Readers of the Local Press

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.01

If we want to read periodicals because they were what the Victorians read, the work that must be done to bring them to life suggests they are not quite what they were.1

As Mussell’s epigram suggests, we see Victorian local newspapers very differently to how their original readers saw them, and we must work hard to recreate that original reading experience. Reading the local paper in the second half of the nineteenth century was different in almost every way from our experience today. These early chapters aim to ‘defamiliarize what is an all too familiar practice’, and show how the circumstances of reading shaped the content of the local press, which in turn shaped the way that people read it.2

Literacy

Who read the local paper in the second half of the nineteenth century? The short answer is, all kinds of people — young and old, from labourers to lords, literate and illiterate. But literacy is a spectrum of abilities, rather than a binary division between the literate and the illiterate, and the local paper was particularly attractive to those who could barely read and perhaps could not write. Two readers in Charles Dickens’s novel Our Mutual Friend — the impoverished childminder Betty Higden and the simple, honest Sloppy — show that literacy is not a simple idea. Mrs Higden reveals some of the complexities to a visitor:

‘Mrs. Milvey had the kindness to write to me, ma’am, and I got Sloppy to read it […] For I aint, you must know,’ said Betty, ‘much of a hand at reading writing-hand, though I can read my Bible and most print. And I do love a newspaper. You mightn’t think it, but Sloppy is a beautiful reader of a newspaper. He do the Police in different voices.’3

Mrs Higden suggests that Raymond Williams’s distinction between the reading public and the read-to public is too simplistic — she could read the Bible ‘and most print’, struggled to read handwriting and preferred to have newspapers read to her.4 She makes no reference to writing, which was taught separately from reading, or sometimes not at all, particularly for girls. Meanwhile Sloppy’s dramatic reading skills can bring to life the characters of a newspaper court report.

Beyond the pages of a Dickens novel, flesh-and-blood Victorians also complicate our ideas of literacy. In the 1850s the Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil could read and write, but would sometimes receive news in the same way as his less literate workmates, by word of mouth.5 At the turn of the century (before radio), a working-class Middlesbrough household was described as ‘not a reading family, but like to hear the news.’6 Literacy was a shared communal asset, enabling individuals who could not read or write to enjoy the newspaper. This sociable, communal aspect of local newspaper reading was still present in the early twentieth century, as in Preston, where an oral history interviewee identified as Mr T2P, born in 1903, remembered the eagerness of his grandmother’s neighbours to hear the news:

I used to go down the road for the newspaper and when I came up with it all the old people in Rigby Street used to follow me up because my grandmother was the only one that could read.7

Readers like Betty Higden, who could be described crudely as semi-literate, were particularly attracted to the local newspaper, because it was about familiar people and places, and was woven into their relationships. Westminster Review editor and social reformer William Edward Hickson, giving evidence to the 1851 Select Committee on Newspaper Stamps, argued that poorly educated agricultural labourers in his native Kent would prefer a newspaper

that related to local events which they really understood […] a paper that gave a good account of some trial at Maidstone assizes […] a paper that gave a good account of some farmer’s stackyard having been burnt down, and what steps were taken in consequence […] a paper that gave an account of what became of a ship that sailed with some families from their neighbourhood with which they might be connected.8

Some semi-literate readers could struggle through the local paper themselves. Tom Stephenson, born in Chorley, Lancashire, in 1893, remembered as a child reading the local paper with his grandmother:

She had had no schooling but had somehow learned to read in middle age. We would tackle the Chorley Guardian together, stumbling over the long words and improvising the pronunciation.9

The appeal to the semi-literate continued. In early-twentieth-century Preston, the Lancashire Daily Post, an evening paper, was the sole reading matter of the semi-literate parents of two women interviewed by oral historian Elizabeth Roberts. ‘Mrs W4P’, born in 1900, described her mother in terms Betty Higden would have recognised:

[My mother] would read the Post. She could read and she could write but she wouldn’t sit and read a long book because she was never used to it.10

‘Mrs B2P’, born in 1916, gave a similar answer in response to the interviewer’s question, ‘When your mother and father were at home, did any of you ever do any reading?’ ‘No,’ she replied, ‘they just used to like the Lancashire Daily Post. They didn’t read books or anything.’11

This attitude, that newspaper-reading is not real reading, was shared by the social investigator Lady Florence Bell, the wife of Sir Hugh Bell, owner of a Middlesbrough ironworks. In 1905 Lady Bell interviewed 200 households to discover the reading habits of her husband’s employees, reporting that ‘about a quarter of the men do not read at all: that is to say, if there is anything coming off in the way of sport that they are interested in, they buy a paper to see the result. That hardly comes under the head of reading.’12 She found that three-quarters of the iron workers only read newspapers, ‘the favourite being a local halfpenny evening paper, which seems to be in the hands of every man and woman, and almost every child.’13

The idea of ‘functional literacy’ helps to explain this preference for the local paper among semi-literate men and women. This approach recognises that literacy is not an abstract set of skills; it comprises a range of activities that are specific and meaningful in particular times and places, for particular purposes.14 Dramatic reading ability like Sloppy’s was more important in a time when communal reading aloud was necessary; local references in news articles, advertising, historical features or dialect writing are meaningful in the paper’s circulation area, less so in the next town ten miles away. Readers used local newspapers for many purposes that could not be supplied by other reading matter, harnessing them to create local public spheres, to share gossip, or to feel connected to their home area when far away. Many of these purposes are about feeling connected, to family, friends and neighbours, making the local newspaper a resource for relationships.15

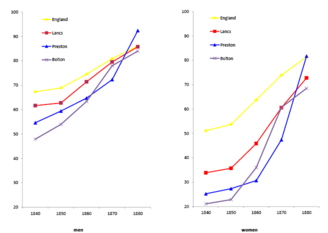

The ability to read, in all its complexity, became more widespread in the second half of the nineteenth century, in the case study town of Preston as elsewhere. The change from hearing to reading the news influenced the newspapers, in their form and content, and affected the reading environment. These changes can be tracked in a crude way by measuring the ability to sign the marriage register. There has been much debate about how this ability relates to other aspects of literacy, but the current consensus is that women and men who could sign their own names rather than marking an ‘X’ could also read at a basic level (but could not necessarily write anything more than their name). While marriage register evidence ignores the subtle gradations described by Betty Higden, they are unique as a standardised form of evidence across time and place, and for every level of society, thereby allowing objective comparisons.16

The marriage registers suggest that basic reading ability had spread to more than ninety-five per cent of the population by the end of the century, but at mid-century literacy in Lancashire was significantly below the English average, with figures for Preston even lower. Across England, two thirds (sixty-seven per cent) of men of marriageable age could sign their names in 1840 but the average for Lancashire was sixty-two per cent, and in Preston barely more than half of bridegrooms (fifty-five per cent) could write their names. By 1880 (local figures are not available beyond 1884), Lancashire men had caught up with the rest of the country, while in Preston they had overtaken the national average, with ninety-two per cent able to sign their name, compared with eighty-six per cent nationally. The trends were broadly similar for women, but from a much lower starting point, with only a quarter of Preston women able to write their name in 1840, compared to a national average of fifty-one per cent. By 1880, Preston women’s literacy was the same as the national average, at eighty-one per cent — still significantly below that of men. Note that literacy was already relatively high, before the introduction of universal elementary education in 1870.

Fig. 1.1. Men (left) and women (right) signing marriage register (%) 1840–1880, selected areas. Source: Registrar General annual reports.

Diagram by the author, CC-BY 4.0.

The low figures at the start of the period can be explained by the lack of demand for literacy in the cotton industry, and the inability of voluntary and informal working-class schools to cope with the influx of population into towns in the early decades of the century (assuming that literacy rates at marrying age reflect schooling from ten to fifteen years previously). Indeed, literacy actually declined in most industrialising Lancashire towns between the 1750s and the 1830s.17 Beyond that, we come up against the limits of these numbers. There are too many contradictory strands to unpick here — on the one hand, Preston’s legal and administrative status required more literacy, it attracted immigrants from more literate rural areas, and was part of Lancashire’s dynamic print culture; on the other, Preston had a poor educational reputation and was the largest town in the country without a school board, from their creation in 1870 to their abolition in 1902, leaving educational administration to the churches. By 1862, Preston had enough school places for every child between three and thirteen years of age, but one commentator claimed that it had ‘a larger proportion of totally ignorant children than any other town of equal size […] the majority of children of the infant stage in Preston are constantly found in the streets.’18 Elementary schooling became compulsory in 1876, but local byelaws in Preston and other textile towns allowed older children to attend school half-time, spending the other half of the week working in the mills, so that, on any one day, roughly a quarter of Preston school-age children were not in school. Related factors may have been the influence of the Catholic church (generally less interested in education than the other denominations), lower Sunday School attendance and lower incomes (in comparison to most Lancashire cotton towns) leaving less to spend on reading matter.19 Crucially, there may have been many people who could read a newspaper but could not write their own name, since writing was often taught after reading, or not at all for some children, particularly girls. However, we can be confident that literacy increased in Preston, as elsewhere, becoming less a collective, more an individual resource, thus requiring less reading aloud for the benefit of those who could not read themselves.

Reading Has a History

The marriage register figures show that literacy varied according to when and where it was measured. This means that reading has a history (and a geography, addressed in the next chapter). The history of reading is a relatively new field of scholarship, overlapping with the history of the book and of print culture, and combines historical and literary strands.20 This dynamic and fruitful new discipline has much to offer a study of reading the local newspaper. The founding text for the history of reading is Richard Altick’s 1957 The English Common Reader, which used a huge array of sources to reconstruct the reading world of ordinary people across the centuries. Although Altick dealt with the reading of newspapers (mainly metropolitan rather than provincial publications), his focus was on books. This bias can be justified when studying periods before the nineteenth century, but from then on, books became a minority of the reading material available, although the scholarship does not reflect this.21 The bias to books in the history of reading is partly explained by the discipline’s literary roots and by its implicit hierarchy of print, in which newspapers rank far below books, as seen in the comments of Lady Bell and the oral history interviewees. Altick’s approach has most recently been developed by Jonathan Rose, focusing on the reading habits revealed by working-class autobiographies. Rose also prioritises book-reading, perhaps because of his explicit aim of showing that the proletariat read Proust.22

Books also dominate the most exciting development in the recent historiography of reading, the Reading Experience Database, which collects and classifies historical evidence of reading from 1450 to 1945. With more than 30,000 records as of February 2018, it now enables scholars to make less tentative generalisations about reading behaviour. However, the literary origins of the project have led to a focus on book-reading, creating a misleading picture of nineteenth-century reading habits. In February 2018 the database held 524 records of newspaper reading between 1850 and 1899, mostly of London papers, compared with 4,224 records of book reading.23 Simon Eliot, a founder of the database, acknowledges that

the book was not the predominant form of text and, more than likely, was not therefore the thing most commonly or widely read […] The most common reading experience, by the mid-nineteenth century at latest, would most likely be the advertising poster, all the tickets, handbills and forms generated by an industrial society, and the daily or weekly paper. Most of this reading was, of course, never recorded or commented upon for it was too much a part of the fabric of everyday life to be noticed.24

Eliot’s point is that starting from the reader rather than the text allows a new picture of nineteenth-century reading to emerge, in which books are less important than newspapers and magazines.

Implying a Reader

The reading habits of real-life historical readers are only surprising because literary scholars have traditionally worked backwards, deducing an imaginary ‘implied reader’ from the text.25 But such readers, conjured solely from a single book or newspaper, are strange creatures, as in this 1853 reconstruction of a reader from the advertisements of the mythical Brocksop, Garringham and Washby Standard, in Dickens’s magazine Household Words:

a native of those parts in luxuriant whiskers, riding forth after a light breakfast of Wind Pills, on a steed watered with British Remedy, or well rubbed down with Synovitic Lotion. He would be going out to buy a windmill, or to engage a governess who did not want remuneration, and he would meet by the road, perhaps, a neighbour with magnificent legs who would talk over with him the news supplied by their gratuitous paper, and speculate upon the chance of the odd hundred pounds that might be paid them for the job of reading it.26

Less absurdly, when we eavesdrop on a telephone conversation, the unseen, unheard person on the other end of the call is like an implied reader. We can make some reliable guesses about them, from the half of the conversation audible to us, but such evidence has its limits. As a case study in reconstructing the reader from the text, take Preston’s most popular paper at the start of the period, the bi-weekly Preston Guardian of 1 September 1860. We can draw some conclusions about the readers from the newspaper’s name, its price and its content: they lived in and around Preston, and were apparently teetotal Nonconformists, with politics allied to the Free-Trader Radical middle-class ‘Manchester School’ of Cobden and Bright, and they were not Irish. Beyond those generalisations, it gets complicated — there were readers from all social classes, mainly men but some women, some Roman Catholics, interested in world affairs, and at least some were highly cultured. We can make these assumptions from the inclusion of Preston in the title of the paper and the amount of local editorial and advertising content; the paper advertised and reported temperance events, and its church coverage mainly concerned Baptist, Congregational and Methodist chapels, with occasional digs at disreputable vicars and the greed of the Church of England. Its editorial line supported advanced Liberalism and condemned the Tories, and it reprinted anti-Irish jokes from Punch. While most of its job adverts were for servants and apprentices, of interest only to working-class readers, it made fun of working-class defendants and witnesses in its court reporting, and it advertised fresh oysters, fee-paying schools and auctions of farms and estates, presumably to wealthy middle-class readers, some of them living in country areas. Some adverts and reports were about Roman Catholic activities, while a fashion article and adverts for dancing and deportment classes and for the supposedly abortion-inducing Widow Welch’s Female Pills (for ‘removing obstructions, and relieving all other inconveniences to which the female frame is liable’) seem to be aimed at women readers.27 Large amounts of foreign news and details of last posting times for overseas mails suggest a cosmopolitan readership, or at least readers with friends and family overseas, while the literary extracts and a feature on the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts suggest an interest in what Matthew Arnold would call culture.

The implied readers of the rival Preston Herald, on the other hand, were Anglican Tory beer-drinkers, of a more female persuasion. In other respects, they were similar to Guardian readers, local people from all classes (although with less advertising aimed at middle-class readers), and some of them Catholic (although the Herald carried more anti-Catholic material than the Guardian).

The implied reader is not as ridiculous as the Household Words article suggests. Changes in the text do reveal changes in readership. Forty years later, at the end of the century, the two papers had dropped their price to a penny, to cater for poorer readers. In 1884 the Preston Guardian had cut the price of its Saturday edition from 2d to 1½d, to bring ‘an accession of readers of the industrial class […] to whom the former price of our Saturday’s publication might operate in some measure as a deterrent […]’28 In 1893 the price fell again, to a penny. A year later, the book review column, entitled ‘Books I Have Read, By a Provincial’, made assumptions about the limited spending power of the typical Preston Guardian reader: ‘Now if one wrote of 31s. 6d. books, how many in Preston would have a chance of seeing them? Very few.’29 The two papers still catered for readers of opposing political and religious views, and the Guardian now had more trade-unionists and children among their readers, apparently. Otherwise, both papers’ clientele had changed in similar ways — they had more time for hobbies such as cycling, gardening, angling and keeping chickens, and more money to spend on these interests; there were also more women readers — and rural readers, judging from the pages of detailed advice and news about agriculture. Despite their price cut, both papers appealed across the classes, from country gentry and urban factory owners to servants in need of a situation. Surprisingly, the readers appeared to have little interest in sport.

However, the evidence of the newspapers themselves may be telling us more about the fiscal and economic environment and the people who produced them, than about those who read them. George and James Toulmin, owners of the Preston Guardian in 1860, were teetotal Methodists, part of a national network of advanced Liberals, while the Herald had just been bought by the local Conservative association. Were there no adverts for pubs in the Guardian because advertisers knew that all the readers were teetotal, or because the publishers refused such ads on principle? In later chapters we will see that publishers sometimes refused to give readers what they wanted (football news, for instance) and that many people read papers without endorsing their editorial line. The texts themselves are not consistent, with the generally anti-Catholic Herald occasionally reporting and even praising the activities of Roman Catholics.

The texts tell us nothing about the aspiring reader, the curious, interested general reader nor the person reading on another’s behalf. The Cycling Notes, the Angling Notes, the Gardening Notes, the Poultry Notes and the Allotment Notes probably were read by cyclists, anglers, gardeners, poultry-keepers and allotment-holders. But they were also probably read by armchair cyclists, anglers and so on, in the same way that we watch a cookery programme whilst eating a takeaway today. As for the general reader, Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil notes in his diary in 1856 that ‘a person was telling me that he has seen the paper last night and wheat had fallen 6/- per quarter at Mark Lane on Monday.’30 His informant is more likely to have been a weaver like himself than a corn merchant — both of them probably general readers, interested in the state of the economy and its impact on Clitheroe. The Preston Guardian in 1860 reprinted its ‘Fashions for September’ article from the leading French fashion magazine Le Follet, and between them these Preston papers carried adverts for women’s fashions, abortion pills, prams, dancing and deportment lessons and job adverts for female occupations. However, men may have bought clothes for women, and men may have helped women obtain abortions.

The lack of sport is explained only if we move beyond the study of one or two publications to the whole of the print ecology available to readers in Preston. From the 1860s onwards, halfpenny evening papers began to be published, aimed chiefly (but not exclusively) at working-class readers. In 1886 two halfpenny evening newspapers were launched within weeks of each other, the Lancashire Evening Post (later renamed the Lancashire Daily Post) in Preston and the Northern Daily Telegraph in Blackburn (with a publishing and editorial office in Preston), designed to be read by the ‘mill hands’ as well as the ‘middle classes’.31 The Post, a sister title to the Preston Guardian, soon cornered the Preston newspaper market in sports journalism. By 1900, on the first Saturday of September, as the end of the cricket season overlapped with the start of the football season, four out of six pages of the Post were devoted to sport, mainly football. Its low price and its content — more ‘working-class’ ads, for a Co-op concert, a gipsy fortune-teller, and situations vacant for apprentices, gardeners and insurance agents — confirm that it was aimed mainly at working-class readers, but readers’ letters and memoirs tell us that doctors and landed gentry also read this paper.

Inferences about readers are safer when based on the most successful publications, those that survived for decades without subsidy, such as the Preston Guardian and the Lancashire Daily Post, their large circulations requiring some editorial understanding of the readers, creating an alignment between what readers wanted and what publishers offered. The repetition over a long period of certain types of content suggests the presence of readers interested in that content — but the opposite does not follow. The absence of other types of content, for example news of Preston’s Catholic churches and societies, does not signify the absence of readers interested in such content. De Certeau captures this distance between the producers and readers of texts, describing readers as ‘travellers; they move across lands belonging to someone else, like nomads poaching their way across fields they did not write […]’32

Readers as poachers, and ‘oppositional’ and unrepresented readers are hard to discern from one newspaper alone. We need to ask, ‘what else were they reading?’33 An ‘oppositional’ reader, to use Stuart Hall’s terminology, actively resisted the intended meaning of the newspaper text. In Preston, a Tory oppositional reader might write a letter to the Tory Preston Herald, expressing his anger and rejection of what he read in the Liberal Preston Chronicle.34 Alton Locke, Charles Kingsley’s fictional Chartist poet, highlights how differently the same text can be read as he describes his oppositional reading of an attack on working-class radicals like himself in a ‘respectable’ newspaper: ‘We see those insults, and feel them bitterly enough; and do not forget them, alas! soon enough, while they pass unheeded by your delicate eyes as trivial truisms.’35 As one of de Certeau’s ‘poaching’ readers, Alton Locke was an eavesdropper who hears nothing good about himself. Eavesdropping readers cannot be implied from the text, yet at a time of communal newspaper reading, they made up a large proportion of readers. As late as 1893, one commentator described how:

In all directions one sees Unionists [Conservatives] reading papers the politics of which are diametrically opposed to their own, because in those papers they get what they want, and even enjoy the clever, if sometimes coarse, attacks on their own Party.36

Unrepresented readers are also not apparent from the text, such as Preston’s Roman Catholic population, who until 1889, ‘had not Catholic journals to fairly represent their cause’, in the words of Fr Bond of St Ignatius’s church, welcoming the newly launched Catholic News from the pulpit.37

Finding Historical Readers

Historical readers are much more interesting, and complex, than implied readers, but they can be hard to find. Reading the local paper was ‘so commonplace and unremarkable and therefore so commonly unremarked upon in the historical record’, yet there is a surprising amount and variety of evidence.38 In the United States, David Paul Nord has skilfully interpreted unpublished letters to the editor, letters published at times of civic crisis, and nineteenth-century government household expenditure surveys, among other sources; the Zborays have used family papers, diaries and correspondence, while Garvey has used scrapbooks to reveal those who did their reading — and writing — with scissors in hand.39 For England and Wales, Jones has revealed readers’ responses to the press through records of debating societies, libraries, correspondence, articles in trade journals and literary reviews.40 I have used two types of evidence, individual and collective. At the individual level there were people who bothered to mention reading the local paper, in their diaries, correspondence and autobiographies; oral history material and published readers’ letters are also valuable. The diaries of Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil allow a detailed study of an individual reader, akin to those of Colclough on the Sheffield apprentice Joseph Hunter and Secord on the Halifax apprentice surveyor Thomas Hirst.41 At the collective level, annual reports of libraries and other reading places list periodicals and newspapers taken, including numbers of multiple copies, and social investigators such as Lady Bell conducted contemporary surveys of reading habits.

Oral history material comes from the Elizabeth Roberts archive at Lancaster University. Roberts interviewed approximately sixty men and women from Preston, fifty-four from Barrow and forty-six from Lancaster, and was ‘confident that they are a representative sample of the working class in all three areas.’42 However, John Walton believes that the number of interviews is too small for quantitative conclusions, while the lack of information about recruitment and selection of interviewees means that we do not know how socially representative they are. Nonetheless, the indexed transcripts have been used here because their testimony is consistent with other evidence. Fortunately, Roberts included a question about newspaper-reading, although the transcripts reveal her assumption that newspaper-reading was a domestic rather than public activity, an assumption that probably coloured the responses. Interviewees were born between 1884 and 1927, so that memories of their childhood homes date from the 1880s to the 1930s.43 These oral history interviews, and other evidence, enable us to move beyond the default, male, middle-class implied reader, and to recognise other readers, differentiated by age, gender and social class, and by their enthusiasm for newspaper-reading.

Age

Children were a small part of the readership of the local paper. However, the rapid expansion of literacy meant that, for a generation or two, it was not unusual for children to be more literate than their parents, and therefore it was quite likely that they would be asked to read the newspaper to their elders. The slightly stagey photograph (Fig. 1.1) below is confirmed by oral history interviewees such as Mrs S4L (b. 1896), who remembered only one paper, the Lancaster Observer, and ‘my mother always used to have that. Do you know I used to have to read that to her, word for word.’ Between 1862 and 1882, older children who stayed on at school would have encountered a newspaper (not necessarily local) as the pinnacle of reading material, as the Revised Code stipulated that pupils must be able to read ‘a short ordinary paragraph in a newspaper, or other modern narrative’, to reach Standard VI, the highest (one headmaster, not from Preston, described using the London evening paper, the Echo, for this purpose).44 However, only two per cent of pupils reached this Standard VI, even fewer in Preston, according to a commentator in 1874 who claimed that ‘Preston, with her possible school population of nearly 20,000 can never in any year present so many as one hundred in Standard VI.’45 Unfortunately, a ‘payment by results’ inspection regime encouraged reading without understanding. The educationalist William Ballantyne Hodgson wrote in 1867 of a boy taught to read from the Bible ‘who, having been asked by his mother to read a passage in a newspaper, was suddenly roused from his monotonous chaunt by a box on the ear, accompanied by these words — “How dare ye, ye scoundrel, read the newspaper with the Bible twang?”’46

Fig. 1.2. Photographic study of child reading to old man, 1907, ‘A Good Friend’ by CF Inston FRPS, Northern Photographic Exhibition, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1907, programme, opp. p. 16, used by permission of Liverpool Archives.

Those who learnt to read as children did not necessarily have an unbroken reading career, as literacy skills often declined when education ended. The attractions of ‘trashy’ reading or the familiarity of the local paper may have kept those skills alive for many of Wilkie Collins’s ‘unknown public’.47 Westminster Review editor and social reformer William Edward Hickson told the 1851 Newspaper Stamp Committee that ‘the only effectual thing to induce them to keep up or create the habit of reading was some local newspaper. If you began in that way, by asking them to read an account of somebody’s rick that was burnt down, you would find that you would succeed.’48 In later years some children were forbidden to read the local paper, such as the oral history interviewees Mr R1P (b. 1897) and Mrs B5P (b. 1898). ‘We weren’t allowed to look at the [Lancashire Daily] Post, you know!’49 Yet children read or heard the news, and sometimes incorporated it into their games, as with the 500 Preston boys, aged 8 and upwards, who had followed the battles of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). They were ‘assembled under commanders who impersonated the Crown Prince of Prussia, Prince Frederick Charles, Steinmetz, Marshals Bassine, M’Mahon and other leaders’ in the Lark Hill district of the town. They were ‘drawn up in line of battle on the opposite sides of the street […] with drums beating and colours (in the shape of dirty handkerchiefs) waving’, receiving final orders, when a policeman chanced upon the battlefield.50 This information must have reached these boys via a newspaper, directly or indirectly.

The Preston Guardian was probably the most popular paper among children in Preston and North Lancashire, because of its column, ‘Our Children’s Corner’, launched in 1884. It was similar in content to the children’s magazines that had flourished from the early nineteenth century onwards, part of the ‘magazinization’ of newspapers that became known as New Journalism in the 1880s and 1890s. The most influential children’s column was the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle’s ‘Corner for Children’, launched in 1876 and hosted by ‘Uncle Toby’, the pseudonym of the editor, W. E. Adams. Imitations of this successful format sprang up across the country, exclusively in the provincial press and particularly in Liberal weeklies like the Preston Guardian.51 This was something new, as the Aberdeen Weekly Journal explained in 1881:

Hitherto Newspapers […] have contained little of real interest and pleasure for Girls and Boys, who, although called upon to read the paper for the benefit of others, seldom find anything in it to suit their own tastes and feelings.52

A distinctive aspect of many such children’s columns was their associated nature conservation clubs, whose members had to promise not to harm any creature. These clubs were hugely popular — the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle’s ‘Dicky Bird Society’ had 50,000 members within five years of its founding in 1876. The columns printed contributions from young readers, such as the staggering 20,183 letters, essays and drawings sent to the West Cumberland Times in just 12 months during 1904–05. The Preston Guardian too had its own ‘Animal’s Friend Society’, which boasted 10,000 members within four years of its launch. Any boy or girl could join by taking this pledge:

I hereby promise never to tease or torture any living thing, or to destroy a bird’s nest, but to promote as much as possible the comfort and happiness of all the creatures over which God has given man dominion.53

Fig. 1.3. Membership badge for provincial newspaper animal welfare club: Preston Guardian Animals’ Friend Society membership badge, twentieth century. Photograph by the author, CC BY 4.0.

An oral history interviewee born in 1895 recalled his class entering their drawings in a Preston Guardian competition.54

Gender

Men were more likely to read newspapers and magazines than women, at least in the memories of oral history interviewees, and this is consistent with women’s lower literacy in the marriage registers seen above. The oral history material suggests that men were twice as likely to read newspapers and periodicals as women: twenty-nine men to thirteen women in Preston, twenty-seven to fourteen in Barrow, but — intriguingly — a more even fifteen to twelve in Lancaster. Eight boys read comics, but only one girl, across all three towns. Girls and women had less time than men for reading, because of their domestic workload, on top of paid work for many women in areas like the textile districts of Lancashire. Bell’s door-to-door survey of reading habits in Middlesbrough in the early years of the twentieth century includes many instances where ‘wife no time for reading’.55

Fig. 1.4. A woman reading a newspaper was an unusual sight. ‘At the Bar’ by Marcus Stone, wood engraving by Dalziel, illustration of pub landlady Abbey Potterson, for original monthly serial of Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend, 1864, Chapter 6, ‘Cut Adrift’, facing p. 54. Scanned by Philip V. Allingham, Victorian Web, CC BY 4.0, http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/mstone/14.html

A woman reading a newspaper by herself in a public place was probably unusual at any time in the nineteenth century, so Dickens’s description of such behaviour by pub landlady Miss Abbey Potterson suggests a rather ‘masculine’ character by the standards of the 1860s. Even by 1889, men outnumbered women in the segregated news rooms of Barrow’s public library by a factor of fifteen to one, ‘a fair average of the number of persons who enter the rooms daily, for the purpose of reading the Newspapers and Periodicals’.56 Women were more likely to read a newspaper at home, even at the end of the century: ‘A lady who has much time on her hands’ would read and re-read the morning paper throughout the day, according to an article in The Journalist and Newspaper Proprietor of 1900. Alternatively, according to the same article, ‘husbands […] in some cases […] mark the daily paper as they read it, to indicate to their wives on their return home in the evening with what portion of the day’s news they should make themselves acquainted.’57 Men could also control women’s newspaper consumption by reading aloud, such as the Preston husband who read extracts from John Bull (a London weekly news miscellany) to his illiterate wife.58 It was more noteworthy for women to read to their husbands.59

The newspaper was by default male reading matter, although most local newspapers described themselves as suitable for family reading, meaning women as well as men. In the text of the newspaper itself, women are misleadingly invisible, with the exception of fashion columns, advertisements for items usually bought by women, price lists for bread, eggs and other household staples at local markets, poetry, and women’s columns and serial fiction in later decades. They are glaringly absent from the correspondence columns of the local press, if we take the male names and pseudonyms at face value. This did not change even when women began to take a more active part in the public life of Preston, with single women gaining the municipal franchise in 1869, the right to stand for the Board of Guardians from 1875, and the right to vote for and serve on parish, urban and rural district councils in 1894.60 Only 12 out of some 900 letters sampled from the Preston papers between 1855 and 1900 purported to be from women, and only 9 in the newspapers of the Furness area of North Lancashire between 1846 and 1880.61 This may have been censorship by editors — the Ulverston Advertiser reported ‘a deluge of letters from Miss A or Miss B requesting a few words’ in support of women’s suffrage in 1872, but refused to publish any of them — and self-censorship by female correspondents, who knew they would be mocked for daring to take part in public debate (something familiar to female Twitter users today). When housemaids dared to respond to a critical article about them in the London Daily Telegraph, a leader in the Huddersfield Daily Chronicle dismissed the ‘interesting house girls’ whose letters were published by the Telegraph, attributing their ‘intense masculine style’ to the help they must have received from the butler or the groom.62 The working-class Carlisle school teacher Mary Smith often used initials or male pseudonyms to write to her local papers, and this was probably a common tactic: ‘In writing on politics, which I often did, I used some other initial, “Z” very often, or other signature. I considered that if men knew who the writer was, they would say, “What does a woman know about politics?”’63

Smith is just one example of the many women who, we know, did read newspapers, both local and metropolitan. She recalled how, in the year of revolutions, 1848, ‘we shared all the excitement of the great world in that small northern village [Scotby, near Carlisle], rejoicing with the best when unkingly kings were uncrowned […] We kept our best sympathies, as well as our intelligence, up to the stroke of the great world, and shared the cares of its life struggles.’64 Besides the fictional examples of Betty Higden and Abbey Potterson, there were the three women newspaper readers described in memoir and oral history interviews at the beginning of this chapter.

Class

Traditional local weekly newspapers tried to be all things to all men (with women as an afterthought). By the second half of the century, they aimed to appeal to working-class as much as middle-class readers, and their popularity in working-class reading rooms attests to their success. Radical newspapers had targeted this audience in the 1830s, when illegal, untaxed papers flourished, and in the 1840s, when the Chartist movement produced a vibrant provincial press, led by the Leeds-based Northern Star — but this competition to the politically mainstream local press had waned by the 1850s. From this decade on, as the newspaper taxes were abolished, penny and halfpenny weekly and evening papers began to appear, aimed squarely at working-class readers. The weekly news-miscellanies such as the Bolton Journal, the Manchester Weekly Times or the Liverpool Weekly Post, now extinct, were hugely popular, and had an overwhelmingly working-class readership.65 One of the first, Birmingham’s Saturday Evening Post, was

specially intended to meet the wants of the great body of the working classes, whose necessities, it is evident, are not to any great extent supplied by the existing papers […] the local news, which the London newspapers, of course, cannot give, and which is of the first importance to the working men of the town and district, will be fully reported… it is hoped that the working man after his week’s labour will carry a copy home with him to his fireside […].66

Working-class readers were increasingly targeted by another new publishing genre, the provincial evening paper, usually selling at a halfpenny. By the early twentieth century, in Middlesbrough, Bell found that the favourite reading matter of foundry workers’ families was the local halfpenny evening paper, the North Eastern Daily Gazette. In one home, ‘The husband does not care to read more than the evening paper. Wife cannot read or write, but she gets her husband to read to her all that is going on in the world.’67 Near St Helens, John Garrett Leigh found them equally popular, and in the oral history material, the local evening paper was the most popular type of newspaper in Preston and Barrow (Lancaster did not have its own evening title).68

In Preston’s traditional weeklies, however, working-class readers were rarely allowed to speak for themselves. There are occasional letters, such as one from the village of Chipping near Preston, claiming to represent ‘We, the poor […]’69 but only a tiny minority of the pseudonyms used by correspondents were avowedly working-class, and these tended to appear at particular times when workers were in the news, as when a textile strike loomed in 1880, and ‘A Cotton Operative’ or ‘A Factory Lad’ had their letters published. In Furness, less than ten per cent of letters to local papers could be identified as coming from working-class writers.70 Like women correspondents, it seems that working-class letter-writers were discouraged from taking part in the public sphere of the correspondence column, unless in disguise.71

And yet, like women readers, working-class readers were more numerous than might appear from the texts of the newspapers. There are many references to poor people reading, and being read to, in pubs in the 1830s (see Chapter 2). During the 1853–54 Preston lockout (when sales of penny dreadfuls were unaffected and fewer books were left in pawn), Reverend John Clay, prison chaplain and campaigner, observed that ‘reading is becoming necessary to the working-man’.72 In 1864 a Preston Chronicle reporter found ‘tidy, good, honest-looking men, with labour-hardened hands, and brave intelligent faces’ reading the papers in the town’s Central Working Men’s Club, and a list of Preston Herald stockists in 1870 included shops in some of the poorest parts of Preston.73 In the 1860s, the inmates of the workhouse read local newspapers and in the 1890s, when Preston’s Harris free library opened, a reporter wrote of how he had ‘often seen men with clogs on pattering away over the beautiful marble hall’, while a photograph of the Harris reading room and news room (Fig. 1.5 below) shows some men without collars, in rumpled jackets and wearing flat caps.74 Librarians and other observers believed that those who read newspapers in the news rooms of free libraries were more proletarian than those who borrowed books (although many commentators in other towns thought that libraries in general were little used by working men).75

Fig. 1.5. Men from different social classes together in the reading room and news room (at rear), Harris Free Library, Preston, 1895. By permission of the Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, all rights reserved.

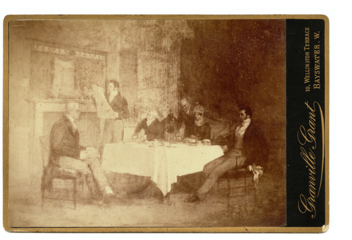

The newspapers reflected the interests of the local middle classes, despite the rhetoric of a unifying local identity that claimed to override class. These were the unspoken default readers of most local papers. In Preston, this implied readership harked back to the town’s pre-industrial identity as a middle-class leisure town and legal/administrative headquarters. This era is captured in the 1822 painting of one of Preston’s richest families, the Addisons, at breakfast (Fig. 1.6 below), in which John Addison Jr., aged 31, is reading the town’s only newspaper at the time, the Preston Chronicle.76 Middle-class readers, as the default, were not studied anthropologically like working-class readers, so there are fewer descriptions of them as a group. But we can pick up hints about some individual newspaper readers, such as two friends, Preston surgeon-dentist John Worsley and the vicar of Heskin near Chorley, Rev John Thomas Wilson. Worsley lived on Fishergate, Preston’s main street, only yards away from the offices of all the local papers, and so it was easy for him to buy newspapers — local, regional and metropolitan — to send on to his friend in the country. Postcards sent by Wilson have survived, in which he often thanks his friend in town for gifts of newspapers.77

Some of Preston’s wealthiest men read their newspapers at their gentlemen’s club, the Winckley club. They had access to scores of publications in their news room in the elegant Georgian Winckley Square, and some of them bid successfully in the club’s annual auctions of back copies, presumably to read at home or to leave in their waiting rooms (many were doctors or solicitors). Members of the club were mockingly described as

members of the learned professions — men in cotton, with not less than twenty thousand spindles or four hundred looms — men with land or railway shares — men with cheek, and who are well dressed — men who have not kept a public house within four years, or in whose family there is not a mangle […] young men in situations with prospects, or who having no ancestors, wish to get into society.78

Fig. 1.6. Most local papers were aimed at middle-class readers in the first half of the century: ‘The Addison Family at Breakfast’, monochrome cabinet card reproduction of painting by Alexander Masses, Liverpool, 1822. By permission of Harris Museum, Preston, all rights reserved.

Biographical scraps for seventeen of the keenest Winckley Club readers give an impression of who they were: around half of them, eight, were local councillors, mostly Conservative, seven were magistrates, four were lawyers, three doctors, two dentists, four mill owners. Many were directors of local companies. Three of the seventeen were Roman Catholic. Two past and present owners of local papers were club members: Miles Myres, Preston coroner and solicitor, a Conservative councillor who served as mayor, a magistrate and a director of the joint stock company behind the Preston Herald, and Isaac Wilcockson, a retired printer and former owner of the Liberal Preston Chronicle, and a councillor and director of the town’s gas and water companies. Other members were Rev T. Barton Spencer, vicar of St James’s Anglican church and chaplain to the workhouse, and Colonel W. Martin, governor of Preston prison, a former soldier and policeman. Some of the club’s younger members were described as ‘cads’ by one local magazine, which condemned the treatment they gave to journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley when he was invited to the club after giving a lecture in 1878. ‘Some of the more juvenile members of the club […] poked their guest about the ribs, called him by his surname, without a prefix, requested him to “stick to his point,” and were altogether so free and easy that the discoverer of Livingstone declared he had never in his travels among the uncivilized come across such a jovial crew.’79 The club’s complaints book, and records of the second-hand newspaper auctions, show that this jovial crew, and their elders, were promiscuous in their newspaper reading, ranging across political, religious and geographical boundaries. They were much more complex than the implied readers suggested by each individual title they read.

Intensity

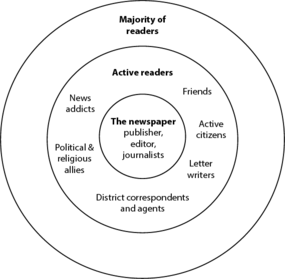

The readers of local newspapers at the Winckley Club, like readers elsewhere, differed in how they felt about each newspaper, and in how they used the local press. For some, newspaper-reading was a particularly important part of their lives, creating a more intense, invested reading experience. We can contrast these ‘active readers’, members of what Stanley Fish called an ‘interpretive community’, with the majority of readers discussed above, who were more emotionally distant from the newspaper, and more socially distant from those who produced the newspaper.80 If we imagine a series of concentric circles (Fig. 1.7 below), with the newspaper, its publisher, editor and staff at the centre, the majority of readers were in the ‘outer circle’. In the middle circle, forming an interpretive community around each newspaper, were active readers; they include members of the same social circles as local newspaper proprietors, editors and journalists; each paper also had scores, sometimes hundreds, of part-time correspondents and contributors, who sent in news items from outlying towns and villages, or wrote expertly on particular topics such as agriculture or local history, or had their poetry published in the paper regularly. There were news addicts, or ‘quidnuncs’ (Latin for ‘what now?’ or ‘what’s the news?’); habitual letter-writers, whose published correspondence reveals a close relationship with ‘their’ paper; public citizens who held office and liked to read about themselves, and readers active in local politics or church and chapel, and who saw particular local papers as supporters and allies of their causes.

Fig. 1.7. Readers and the closeness of their relationship with a local newspaper. Diagram by the author, CC BY 4.0.

News addicts were typically male and working-class, for example the young James Ogden in Rochdale, whose thirst for reading was indulged by a local newsagent in the 1850s. He described himself as ‘a studious and, in literature a ravenous lad’ who was allowed to read the papers after the shop had closed.81 Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil (b. 1810) revealed his news addiction in his diaries; the longest entry each week was usually a summary of what he had read in the newspaper each Saturday evening, taking precedence over the topics of family, friends or work. He had been a hand loom weaver in his native Carlisle, was probably self-educated, and had been active in two working-class reading rooms and in local reform politics. He left Carlisle in search of work in 1854, settling in Low Moor, a factory village of about 1200 people, near Clitheroe in Lancashire, two years later. Here he worked as a power loom weaver at Garnett & Horsfall’s factory. He was a widower with one daughter, renting a factory cottage and working sixty hours a week. He was able and popular, becoming president of his village reading room, and president of the Clitheroe Power Loom Weavers’ Union. In the 1860s he was active in local Liberal politics as a member of Clitheroe Working Men’s Reform Club and later the town’s Liberal Club. He read local, regional and metropolitan newspapers in reading rooms, in pubs and at home, and discussed what he read with workmates and other users of public reading places. J. Barlow Brooks (b. 1874) worked as a half-timer in a cotton mill in Radcliffe near Bolton from the ages of ten to thirteen, before becoming a pupil teacher, and eventually a Methodist minister. He and his brother and mother bought local, regional and socialist newspapers every week, plus many other weeklies second-hand from the Co-operative reading room. They bought so many papers and magazines that the material filled a back bedroom and began to encroach on the stairs.82

Inveterate letter-writers, often signing themselves ‘A Constant Reader’, had a similarly intense relationship with particular titles, but were more active in responding to the content of the paper with a stream of correspondence. These readers are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6. They are similar to the minority of ‘fans’ of the Chicago community press identified by Janowitz in the mid-twentieth century, individuals who were emotionally involved with their weekly local paper.83 These and other active readers who used a local newspaper in a public way, leaving historical traces, probably had more in common with the publishers and journalists than with the readership as a whole. With some exceptions, they tended to be middle-class and male, as confirmed by those who signed letters in their own names, or gave an occupation.

While these news addicts and letter-writers read mainly for pleasure and interest, others who could be described as active citizens — business people, councillors, magistrates, trade union officials — liked to read about themselves and their public activities in the local press. One Preston editor claimed that ‘nobody except Town Councillors and their wives or relatives will read through’ a detailed report of a council meeting.84 Another group, political activists, used rather than read the local paper, developing relationships with sympathetic newspaper owners who were politically active themselves, and writing letters and other articles in support of their causes. They read the paper for news of support or opposition to their party or campaign. Mary Smith, the Carlisle teacher, became friendly with radical editors of local papers, including Washington Wilks of the Carlisle Journal and then the Carlisle Examiner (and later the London Morning Star), a Mr Lonsdale, editor of the Carlisle Observer, and an unnamed editor of the Carlisle Express. These contacts enabled her to publish poems, articles and letters against capital punishment and in support of women’s suffrage, or backing a radical election candidate, among other campaigns.85 In Preston, Edward Ambler, a printer and prominent Liberal, Congregationalist and Oddfellow, read and wrote for Preston’s Liberal papers in support of his party, his friendly society, his skirmishes as a Poor Law Guardian and his work for a free library.86 Smith and Ambler were at the centre of the interpretive communities of readers built around their favoured local papers.

Conclusions

Studying the text of the local newspaper gives us some information about the type of readers being targeted. But the implied reader, usually a middle-class man, is only part of the picture. Other evidence reveals that the illiterate and semi-literate in particular were drawn to the local paper, that women and children were readers, and that working-class readers eavesdropped and ‘poached’ across newspapers created for middle-class purchasers. Literacy was a communal asset, particularly at mid-century, available to those who could read and those who could not; similarly, reading the local paper was usually a communal activity. Local newspapers were one part of the social revolution stimulated by the swift spread of literacy, in which children became the experts, better able to use the technology of print than their parents. The spread of literacy was even swifter in Preston, going from below the national average to above it in less than two generations. This demonstrates how reading is geographically and historically specific. However, even within one town, readers differed in their relationship to the local newspapers, some untouched by them, some on the fringes of their influence (such as the boys re-enacting the battles of the Franco-Prussian War), and some at the heart of interpretive communities clustered around each title. The latter group in particular left their mark on Preston, even creating or commandeering entire buildings in which to read newspapers, particularly local newspapers. These places are the subject of the next chapter.

1 James Mussell, ‘Repetition: Or, “In Our Last”’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 48 (2015), 343–58 (p. 344).

2 Miles Ogborn and Charles W. J. Withers, ‘Introduction: Book Geography, Book History’, in Geographies of the Book (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), p. 20, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315584454

3 Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend (London: Chapman and Hall, 1865), p. 162.

4 Raymond Williams, The Long Revolution (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965), p. 184.

5 John O’Neil, The Journals of a Lancashire Weaver: 1856–60, 1860–64, 1872–75, ed. by Mary Brigg (Chester: Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1982), 5 February 1856.

6 Florence Eveleen Eleanore Olliffe Bell, At the Works: A Study of a Manufacturing Town (London: E. Arnold, 1907; repr. Middlesbrough: University of Teesside, 1997), p. 107. Her reading survey was originally published in the Independent Review 7 (1905), 426–40.

7 ‘Social and family life in Preston, 1890–1940’, transcripts of recorded interviews, Elizabeth Roberts archive, Lancaster University Library (hereafter ER; the letters P, B or L at the end of the interviewee’s identifier denotes whether the interviewee was from Preston, Barrow or Lancaster): Mr T2P (b. 1903). The transcripts are being digitised, with some available at www.regional-heritage-centre.org

8 House of Commons, ‘Report from the Select Committee on Newspaper Stamps; Together with the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, Appendix, and Index’1851 (558) XVII. 1 (questions 3175, 3198).

9 Tom Stephenson, Forbidden Land: The Struggle for Access to Mountain and Moorland (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989), p. 15.

10 Mrs W4P (b. 1900), ER.

11 Mrs B2P (b. 1916), ER.

12 Bell, p. 145.

13 Ibid., p. 144.

14 David Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture: England 1750–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 15–16, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511560880; David Barton and Mary Hamilton, Local Literacies: Reading and Writing in One Community (London: Routledge, 1998), p. 7.

15 Barton and Hamilton, p. 7.

16 Vincent, pp. 17–18, 23; Carl F. Kaestle, ‘Studying the History of Literacy’, in Literacy in the United States: Readers and Reading since 1880, ed. by Carl F. Kaestle and others (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), pp. 1–32 (pp. 4, 11–12). For a critique of marriage registers as a source, see Richard Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), p. 170.

17 For detailed discussion of literacy rates, see Vincent, pp. 24, 97; William B. Stephens, Education, Literacy and Society, 1830–1870: The Geography of Diversity in Provincial England (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), pp. 5–7, 10–11, 19, 96, 327.

18 Letter from Mr T. Paynter Allen, National Education League Monthly Paper, May 1872, reprinted in ‘Education in Preston and Blackburn’, Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC) May 16, 1872; for Preston’s lack of school board, see House of Commons Debate on Voluntary Schools Bill, 16 February 1897 vol 46 col. 544, in Historic Hansard, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1897/feb/16/voluntary-schools-bill

19 Michael Savage, The Dynamics of Working-Class Politics: The Labour Movement in Preston 1880–1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), pp. 69–70, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511898280

20 Christine Pawley, ‘Retrieving Readers: Library Experiences’, Library Quarterly, 76 (2006), 379–87 (p. 380), https://doi.org/10.1086/511761; Stephen Colclough, Consuming Texts: Readers and Reading Communities, 1695–1870 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), Chapter 1, ‘Reading has a history’, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230590540

21 The director of the Waterloo Directory of Victorian Periodicals project, John North, estimates there were more than one hundred times as many individual editions of periodicals and newspapers published in the nineteenth century as books: ‘Compared to books,’ Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals: 1800–1900, online edition, www.victorianperiodicals.com/series2/TourOverview.asp

22 Jonathan Rose, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (London: Yale University Press, 2001), pp. 4–5.

23 Reading Experience Database, www.open.ac.uk/Arts/RED

24 Simon Eliot, The Reading Experience Database; or, What Are We to Do About the History of Reading?, http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/RED/redback.htm. On the reading of non-literary texts, see Mike Esbester, ‘Nineteenth-Century Timetables and the History of Reading,’ Book History 12 (2009), 156–85, https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.0.0018; Sadiah Qureshi, Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (University of Chicago Press, 2011), ch. 2, ‘Artful promotion’, https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226700984.001.0001

25 For a defence of this technique, see Susan J. Douglas, ‘Does Textual Analysis Tell Us Anything about Past Audiences?,’ in Explorations in Communication and History, ed. Barbie Zelizer (London: Routledge, 2008), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203888605

26 Anon., ‘Country News’, Household Words, 2 July 1853, pp. 426–30 (p. 427), found in Dickens Journals Online, http://www.djo.org.uk/household-words/volume-vii/page-426.html

27 P. S. Brown, ‘Female Pills and the Reputation of Iron as an Abortifacient’, Medical History, 21 (1977), 291–304, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025727300038278

28 Preston Guardian (hereafter PG), 4 October 1884, p. 5.

29 PG, 26 May 1894, p. 9.

30 O’Neil diaries, 6 March 1856.

31 The Journalist, 3 December 1886, pp. 114–15.

32 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), p. 174. Here is a perfect example of poaching readers from 1928: ‘In Norwich any three or four householders may ask the free library committee to buy for the library a book they need. Mr Charles Row, in his Practical Guide to the Game Laws (Longmans) […] says some poachers requisitioned the first edition of this book in this way and when he conducted prosecutions used to pull him up with such remarks as, ‘No, no, Charlie, you’re wrong there; your book in the free library doesn’t say that’: Anon., ‘Country Books of the Quarter’, Countryman, April 1928, p. 90.

33 Rose, p. 93.

34 For example, ‘Borough registration’, letter contradicting the Preston Chronicle’s account of voter registration, Preston Herald (hereafter PH), 13 October 1860, p. 6.

35 Charles Kingsley, Alton Locke: Tailor and Poet (Cassell, 1969), p. 48; Stuart Hall, ‘Encoding/Decoding’, in Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, ed. by Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas Kellner (Malden: Blackwell, 2006).

36 FitzRoy Gardner, ‘The Tory Press and the Tory Party, I. — a Complaint’, National Review, 21 (1893), p. 358.

37 Catholic News, 16 February 1889, p. 3.

38 David Paul Nord, ‘Reading the Newspaper: Strategies and Politics of Reader Response, Chicago, 1912–1917’, in Communities of Journalism: A History of American Newspapers and Their Readers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), pp. 246–77 (p. 269).

39 Nord, Communities of Journalism; Ronald J. Zboray and Mary Saracino Zboray, ‘Political News and Female Readership in Antebellum Boston and Its Region’, Journalism History, 22 (1996), 2–14; Ronald J. Zboray and Mary Saracino Zboray, ‘“Have You Read…?”: Real Readers and Their Responses in Antebellum Boston and Its Region’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, 52 (1997), 139–70, https://doi.org/10.2307/2933905; Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195390346.001.0001

40 Aled Gruffydd Jones, Powers of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth-Century England (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996), p. 181; for other types of newspaper reading evidence, see Peter J. Lucas, ‘The First Furness Newspapers: The History of the Furness Press from 1846 to c.1880’ (unpublished M.Litt, University of Lancaster, 1971) and Marie-Louise Legg, Newspapers and Nationalism: The Irish Provincial Press, 1850–1892 (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1999).

41 Stephen Colclough, ‘Procuring Books and Consuming Texts: The Reading Experience of a Sheffield Apprentice, 1798’, Book History 3 (2000), https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.2000.0004; James A. Secord, Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), chap. 10.

42 Elizabeth Roberts, A Woman’s Place: An Oral History of Working-Class Women 1890–1940 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1985), p. 6; John K. Walton, Lancashire: A Social History, 1558–1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), pp. 293–94.

43 For a summary of references to reading and writing in the Roberts material, see Barton and Hamilton, Local Literacies, pp. 28–31 and David Barton, ‘Exploring the Historical Basis of Contemporary Literacy’, The Quarterly Newsletter of the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition, 10 (1988), 70–76.

44 Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Working of the Elementary Education Acts in England and Wales (P.P. 1887, C. 5158, Third Report, Evidence), p. 356.

45 Altick, p. 158; Vincent, p. 43. The Preston figures may have been exaggerated, as the writer was using them to argue for the establishment of a School Board in the town: Letter from Mr T. Paynter Allen.

46 Harvey J. Graff and W. B. Hodgson, ‘Exaggerated Estimates of Reading and Writing as Means of Education (1867), by W. B. Hodgson’, History of Education Quarterly, 26 (1986), 377–93 (p. 389), https://doi.org/10.2307/368244

47 [Wilkie Collins], ‘The Unknown Public’, Household Words, 18 (1858), 217–22.

48 Evidence of William Hickson, 1851 Newspaper Stamps Committee, Q3240.

49 Quote from Mrs B5P, ER.

50 ‘French and Prussians on a small scale’, PH supplement w/e 3 September 1870, p. 4.

51 PG, 17 February 1894, p. 16.

52 Aberdeen Weekly Journal, 2 August 1881, cited in Frederick Milton, ‘Uncle Toby’s Legacy: Children’s Columns in the Provincial Newspaper Press, 1873–1914’, International Journal of Regional and Local Studies, 5 (2009), 104–20 (p. 104).

53 PG, 22 December 1888, p. 4; PG, 17 February 1894, p. 16. For more on animal welfare organisations associated with the provincial press, see Milton.

54 Mr G4P (b. 1895), ER.

55 Bell, passim.

56 Barrow Library annual reports, 1887–89, Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre, Barrow, p. 220.

57 ‘Getting Through the Morning Newspaper’, The Journalist and Newspaper Proprietor, 20 October 1900, p. 329.

58 See also Mrs M6L (b.1885), ER. For the expectation that fathers should read aloud to the family, see Thomas Wright [The ’Journeyman Engineer’], ‘Readers and Reading’, Good Words, 17 (1876), 315–20 (p. 316).

59 See for example ‘Daring Attempt To Rob A House — Beware Of General Dealers’, London Standard, 22 April 1858, p. 7; ‘Quips and Cranks’, North-Eastern Daily Gazette, 27 November 1890, British Newspaper Archive.

60 Brian Keith-Lucas, The English Local Government Franchise: A Short History (Oxford: Blackwell, 1952), pp. 55, 59, 69; Patricia Hollis, Ladies Elect: Women in English Local Government 1865–1914 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), pp. 207, 357, 392.

Women gained the right to serve on borough councils such as Preston’s in 1907.

61 Peter J. Lucas, ‘The Regional Roots of Feminism: A Victorian Woman Newspaper Owner’, Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, Series 3, 2 (2002), 277–300 (p. 293); Lucas, ‘First Furness Newspapers’, p. 73.

62 Huddersfield Daily Chronicle, 13 March 1876, p. 2, British Newspaper Archive.

63 Mary Smith, The Autobiography of Mary Smith, Schoolmistress and Nonconformist, a Fragment of a Life (Volume 1); With Letters from Jane Welsh Carlyle and Thomas Carlyle (Carlisle: Wordsworth Press, 1892), p. 259. I am grateful to Dr Helen Rogers for this reference.

64 Smith, p. 149.

65 Graham Law, Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000), p. 142.

66 Announcement in Birmingham Journal, 21 November 1857, cited in Harold Richard Grant Whates, The Birmingham Post, 1857–1957. A Centenary Retrospect (Birmingham: Birmingham Post & Mail, 1957), pp. 47–48.

67 Bell, pp. 44, 190.

68 John Garrett Leigh, ‘What Do the Masses Read?’ Economic Review, 4 (1904), 166–77 (p. 176).

69 PH, 25 September 1880, p. 6.

70 Lucas, ‘First Furness Newspapers’, p. 61.

71 See also Leah Price, How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2012), p. 261, https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691114170.001.0001. Price follows the paper as object to reveal social differences hidden by the words printed on those pieces of paper.

72 Walter Lowe Clay, The Prison Chaplain: A Memoir of the Rev. John Clay, B. D., with Selections from His Reports and Correspondence, and a Sketch of Prison Discipline in England (Cambridge: Macmillan, 1861), pp. 545–47.

73 PC, 20 February 1864; ‘Agents for the Sale of the “Herald’, PH, 3 September 1870, p. 5.

74 PG, 30 January 1869, p. 2.

75 William Bramwell, Reminiscences of a Public Librarian, a Retrospective View (Preston: Ambler, 1916), p. 18; Martin Hewitt, ‘Confronting the Modern City: The Manchester Free Public Library, 1850–80’, Urban History, 27 (2000), 62–88 (p. 73), https://doi.org/10.1017/s0963926800000146; Leigh, p. 169; Bell, p. 163.

76 The original painting, now lost, is described from earlier sources in Brian Lewis, The Middlemost and the Milltowns: Bourgeois Culture and Politics in Early Industrial England (Stanford University Press, 2002), pp. 104, 461.

77 Anne R. Bradford, Drawn by Friendship: The Art and Wit of the Revd. John Thomas Wilson (New Barnet: Anne R. Bradford, 1997).

78 ‘A Description of Preston and its People’, reprinted from a ‘north country magazine’ in PC, 10 December 1870.

79 ‘Gossip Abroad’, The Wasp, 7 December 1878, p. 7, Community History Library, Harris Library, Preston.

80 Stanley Eugene Fish, ‘Interpreting the Variorum’, Critical Inquiry, 2 (1976), 465–85, https://doi.org/10.1086/447852

81 James Ogden, ‘The Birth of the “Observer”’, Rochdale Observer, 17 February 1906.

82 Joseph Barlow Brooks, Lancashire Bred: An Autobiography (Oxford: Church Army Press, 1951), pp. 169, 177.

83 ‘Fans’ accounted for eleven per cent of survey respondents: M. Janowitz, The Community Press in an Urban Setting (Glencoe: Free Press, 1952), pp. 106–7.

84 ‘Preston and Roundabout. Notions and Sketches [By “Atticus.”]: Our Town Council and its Members’, PC, 4 April 1868.

85 Smith, pp. 198, 204, 255, 260.

86 For example, letters from Ambler to George Melly, 23 and 30 March 1864, Liverpool Archives, George Melly Collection, 920 MEL 13 Vol. IX, 1990 and 1991; ‘Death of a Preston printer’, PC, 29 October 1887; H. A. Taylor, ‘Politics in Famine Stricken Preston: An Examination of Liberal Party Management, 1861–65’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, 107 (1956), 121–39.