2. Reading Places

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.02

We need to know where the local newspaper was read to understand how it was read, because the same texts take on different meanings in different places.1 The same report of a Preston football victory over Blackburn has opposite meanings, of success or failure, in each town. To a reader far from home, missing familiar faces and places, a copy of their local paper takes on extra significance, as a physical reminder of who they are and where they are from. Equally, listening to a newspaper being read and interpreted by an ardent Chartist in a crowded pub becomes an intense and emotional act of political solidarity, a very different experience to reading the same paper in silence in a Church of England news room, under the eyes of the curate, or at home with one’s family. We can see how newspaper buying, borrowing and reading was everywhere, by taking an imaginary stroll around Preston. The places of newspaper-reading, where ‘media rituals’ were enacted, are concrete evidence of the importance of newspapers, including local newspapers, in people’s lives; they were willing to rent, repurpose and even erect purpose-built structures where newspapers could be produced, bought, read and discussed. Let us pretend that we are Victorian flaneurs, and visit the places, largely ‘reading institutions’, where newspapers were read. It is also a chance to get to know our case study town of Preston. An hour’s leisurely walk, in 1855 and again in 1875 and 1900 will be enough to see the variety of such places, and how they changed over 45 years.

1855

We will begin in the market square behind the town hall. On a Saturday evening in September 1855, an old, lame man, ‘Uncle Ned’, sings one of the broadside ballads he is selling.2 One of the busiest shops lining the square is Dobson’s at 17 Market Place, where a steady stream of people has been going in and out of this bookshop, printer’s and newspaper publisher’s, to pay 3½d for today’s issue of the town’s oldest surviving newspaper, the weekly Preston Chronicle (est. 1807). Men stand around outside the shop in groups, listening to others read aloud from the paper and commenting on what they hear, eager to learn the latest from the siege of Sebastopol, or any other news of the Crimean War. One man is reading the Times, which arrived in Preston in the early afternoon. We cross the square, past Henry Thomson’s newsagent’s shop and the general news room above 6 Friargate. Round the corner on the main street, Fishergate, there are more reading places — the Guild Hall news room inside the squat, boxy Georgian town hall, and, opposite, the Commercial News Room on Town Hall Corner, offering newspapers and telegrams. These rooms can become crowded if an exciting story breaks, with non-members bending the rules to keep abreast of the news. One member of the Commercial News Room complained that, during the American Civil War

it is very annoying, these stirring times, to be unable to get near the telegrams, on account of some inveterate newsmonger, who does not subscribe, or be prevented reading the Times, through its being monopolised by one whose name does not figure in the list of subscribers.3

Across the road to the left, between the thatched Grey Horse Inn and the imposing four-storey Georgian Bull and Royal Hotel, is the Preston Pilot office (Fig. 2.1), with its own knots of readers and listeners standing outside. On either side, if we were to peep through the doors of the modest inn or the grander hotel, we would see men and the occasional woman reading newspapers provided by the house.

Fig. 2.1. Office of Preston Pilot, Church Street, Preston. Detail from ‘The Grey Horse’, J. Ferguson, 1853. By permission of Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library, Preston, England, all rights reserved.

But we turn in the opposite direction, across Fishergate, past the groups of newspaper-readers outside the Preston Guardian office (busier than the other two newspaper offices), to Cannon Street, a steep, narrow sidestreet descending from Fishergate. On one corner is the Exchange Commercial News Room, opened in May. Like the others we have passed, this is a select establishment, charging one guinea per year, more than a week’s wages for most cotton workers. Near the bottom of the street, on the left, is the old mechanics’ institute, its rooms still used for education by various ‘classical schools’. Until a few weeks ago, one room was let as Cowper’s Penny News & Reading Room, for a poorer clientele than the other news rooms; in the tradition of previous working-class Preston news rooms, it was occasionally used for political lectures and discussions. Cowper’s closed a few weeks before Stamp Duty became an optional postal charge rather than a compulsory tax in July 1855, leading to a reduction in newspaper prices, enabling more people to buy their own copy. A mill worker on a typical wage of fifteen shillings a week could earn a penny in twenty minutes, taking just over an hour to earn 3½d, the price of a local paper or a quart of beer (two pints). On the other side of the street is the first of three bookshops, Charles Ambler’s, Isaac Bland’s, and Evan Buller’s, the latter selling newspapers alongside books and all manner of crucifixes and Roman Catholic paraphernalia.

We turn left onto Cross Street, Syke Street then Avenham Lane. Further east are some of the poorest streets in Preston; there are no bookshops, newsagents or reading rooms in that district, only two schools, one of which, Grimshaw Street Independent Sunday School, boasts a circulating library. If we dared to go further we might find a newspaper or two in the many pubs and beerhouses, on sale in one or two corner grocer’s shops, or in a rare home that can somehow obtain a newspaper and the light by which to read it. But instead, by the National School, with its Sunday School reading room, we cross the cobbled, winding lane, lined by terraced houses and shops, and walk up past Richard Alston’s bookshop and newsagent’s. Every pub we pass is also a reading place, of course.

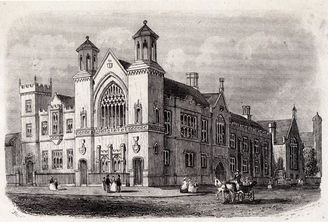

On either side, in the streets off Avenham Lane, are at least eight small schools, mostly for girls, run from private houses — the local newspaper is probably among the reading material used at some of them. At the top of the hill, we are at the edge of Preston’s wealthiest area — where each house can probably afford its own copy of a local paper and a London paper, and the gaslight to read them by. At the head of a tree-lined avenue is a solid, new neo-classical building fronted by steps and curling balustrades, the Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge (Fig. 2.2 opposite), also known as the mechanics’ institute, with its news room and reading room. The news room opened in 1850, and by last year had seventy-five members — although membership has fallen this year after the Stamp Duty became optional (within three years it will be ‘well sustained by numerous subscribers’ once again).4 Round the corner is the wide Georgian splendour of Winckley Square, the epicentre of the town’s wealth, these elegant villas home to the mill owners, merchants, lawyers and doctors who run Preston.

Fig. 2.2. The Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge (mechanics’ institute), Avenham, Preston, had a news room and a reading room. Engraving from Charles Hardwick, History of the Borough of Preston and its Environs, in the County of Lancaster (Preston: Worthington, 1857). Scan from Preston Digital Archive, CC BY 4.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/rpsmithbarney/5753101486/

On the east side of the square, we come to the Literary and Philosophical Institute, an imposing building in the style of an Oxbridge college chapel, with its news room, reading room and circulating library, in front of the Grammar School. The institute’s well-off members seceded from the mechanics’ institute after a ‘slight misunderstanding’ in 1840. The next building, behind the same railings, sports similar academic architecture, with its square tower and oriel window. This is the Winckley Club, used as an HQ only a year ago by the town’s most powerful factory owners, as they co-ordinated their lock-out of almost every cotton mill in Preston. The club opened in 1846, initiated by members of the Gentlemen’s News Room at the town hall. Besides a billiards room and dining room, the Winckley Club boasts a ‘large and handsome news room on the ground floor, artistically decorated and fitted’, where ‘the leading gentlemen of the town resort to read newspapers and chat over the events of the day’.5 For this, members paid between £1 6s 6d and £2 12s 6d per year.

The news room is the largest room in the club, with long tables, on which thirty to forty newspapers and magazines are scattered, and some higher tables with stands, for reading large broadsheet newspapers whilst standing. There are benches and comfortable chairs, writing desks, bookshelves full of reference books and bound copies of the most important papers (including some local titles), maps and pictures on the walls, a large fireplace, gas lamps, and a bell rope to summon the servants. This is not a quiet room generally, especially in the evening, with the sound of conversation, laughter, people reading an article aloud to their friends, the occasional argument, the clink of glasses, the sound of doors slamming elsewhere in the building, and the shouts of billiard and card players.

Fig. 2.3. Literary and Philosophical Institute (centre) and Winckley Club (left), Winckley Square, Preston. Author’s own copy, CC BY 4.0.

We continue up the square and back onto Fishergate, the busy high street. Almost opposite, down Fox Street, is the Catholic Institution with its reading room, but we turn back towards the town hall, past 97 Fishergate, Henry Barton’s bookshop and printing office, from where he publishes his Preston Illustrated General Advertiser and the newly launched penny Preston Herald (2½d cheaper than Preston’s three other papers). Further along is Ann Thomson’s Catholic bookshop; next door but one is another bookseller, Edward Wilcock. Across the street is William Bailey’s bookshop and printing office. Past the Shelley’s Arms, a popular place to read the paper, like every other pub and beerhouse along this street, on past Henry Oakey’s shop selling books and stationery, with its printing office at the back, on the corner of Guildhall Street. Mr Oakey also runs a circulating library, mainly of novels. We walk past the newly opened news room of the Young Men’s Club on our right, frequented by clerks, book-keepers and the like, and back to the market square.

Our little walk has taken us past scores of places where newspaper-reading is an important activity — the street, the pub, bookshops and ‘newsvendors’, reading rooms and news rooms, printers’ offices and newspaper publishers. Each of them offers different reading experiences, but in the 1850s most newspaper-reading was still communal, as papers were expensive and scarce. In the same way, twentieth-century film audiences gathered together in cinemas, and early TV viewers went to the one house in the street that had a set.

The street was an important reading place, full of signs and advertisements, shop windows, and walls plastered with posters and placards. People gathered outside newspaper offices to read the paper, but also in other public places, and under street lamps or shop lamps at night. Reading in the street was a communal activity, with one person reading aloud (adverts as well as editorial), interspersed with comment and discussion. It would have been unusual to see anyone reading a paper by themselves, and regardless of reading ability, anyone interested in the news could have picked up the main points by listening to the paper being read, or by asking someone in possession of a newspaper or leaving a news room. Reading places were sociable places.

Certain places were news hubs — the newspaper offices, larger reading rooms and, after the telegraph came to Preston in 1854, the telegraph company offices — the Magnetic Telegraph Company on Fishergate and the Electric and International Telegraph Company in the station at the far end of the street.6 In 1857 the Magnetic Telegraph Company opened a subscription news room above its office. Before the telegraph, people probably waited at the station for news to arrive by train, as they did in Clitheroe in 1857, when O’Neil recorded in his diary:

I went up to Clitheroe in the evening and there was a great many waiting for the train from Blackburn with the elections news as there is no telegraph in Clitheroe. The first news I heard after the train came in was that Cobden, Gibson and Bright were thrown out by large majorities […]7

When Prince Albert died in 1861, the news was received by the telegraph office at Preston station early on a Sunday morning, and copies of the bulletin were posted at the town’s main news hubs before the town awoke — on the shutters of the four newspaper offices, at the Winckley Club and outside the mechanics’ institute.8 Preston was one of the first constituencies in the country to vote by secret ballot after its introduction in 1872, but before then, voters and non-voters alike would crowd around the windows of the town’s newspaper offices to see the current state of the poll, updated every hour.9 Such excitement could last for weeks during lengthy polls. James Vernon argues that the earnest and private rationality of newspapers killed the inclusive drama of public politics, but newspaper-reading actually increased the number of places where public politics was performed.10

There were more than 400 pubs and beerhouses in Preston in the 1850s, and most of them probably provided at least one newspaper for their customers.11 The Victorian sign in the Liverpool pub in Fig. 2.4 shows that pubs saw newspapers as an attraction worth advertising in their windows, even setting aside valuable space for their reading, as with the ‘reading room’ of the Boar’s Head Inn in Friargate, Preston or the ‘news room’ of Blackburn’s Alexandra Hotel (Fig. 2.5 below), whose landlord even advertised the titles of the papers available (most of them regional or local). Pubs were attractive, cheap and accessible reading places for working-class people — warm, well-lit, with reading material sympathetic to their interests, unpoliced by middle-class reformers or evangelists, allowing free discussion, in a convivial atmosphere fuelled by alcohol.12 In Clitheroe, O’Neil could obtain a newspaper to read at home, but he preferred to walk a mile into town to read the news in the Castle Inn every Saturday night.13 However, it was impossible to read the paper if the pub was too busy or noisy, as during Clitheroe’s fair, when the town was ‘throng’ with people. O’Neil wrote: ‘I had a few glasses of ale but Public Houses was so throng and so noisy I could not read the newspaper […]’14 Neither could he read if he drank too much, as on New Year’s Day 1859: ‘I went up to Clitheroe and got my Christmas glass. It was the best whiskey I ever got in my life, it nearly made me drunk. It made me so that I could not read the newspaper, so I had to come home without any news.’

Fig. 2.4. News room sign in window of the Lion Tavern, Moorfields, Liverpool, built c.1841. Author’s photo, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 2.5. Advertisement for Alexandra Hotel, Blackburn, listing newspapers available in its news room, Preston Herald, 10 November 1866.

Transcription by the author, CC BY 4.0.

‘Ask the landlord why he takes the newspaper. He’ll tell you that it attracts people to his house, and in many cases its attractions are much stronger than those of the liquor there to be drunk’, William Cobbett claimed in 1807.15 In Preston, reading the paper aloud and discussing its contents had been a formalised event during the excitement of the 1830 election, at which the radical Henry Hunt defeated Lord Stanley:

They flocked to the public-house on a Sunday evening as regularly as if it had been a place of worship, not for the set purpose of getting drunk, but to hear the newspaper read. The success of the landlord depended, not on the strength of his beer altogether, but on having a good reader for his paper […] it was not the general custom to drink during the reading of the paper. Every one was expected to drink during the discussion of any topic, or pay before leaving for the good of the house.16

Like Sloppy ‘who do the Police in different voices’, these skilled public readers brought the newspaper alive in crowded pubs.

One Liverpool pub landlord, John McArdle, performed the paper himself, creating a very different experience from reading silently and alone. Irish nationalists came to his pub in Crosbie Street every Sunday night to hear him read the Nation (which cost sixpence in the 1840s).

McArdle was a big, imposing looking man, with a voice to match, who gave the speeches of O’Connell and the other orators of Conciliation Hall with such effect that the applause was always given exactly in the right places, and with as much heartiness as if greeting the original speakers.17

The comments and interpretations of such ‘local prophets’ expounding upon the ‘secular texts’ of the newspaper, were considered dangerous by some commentators, who preferred the rule of silent reading found in many mechanics’ institutes and free libraries.18 There is evidence of reading the paper aloud in the pub as late as 1874, in Sheffield at least, and it seems likely that pubs continued to be significant places for reading and performing the newspaper well into the twentieth century.19

On our walk we passed many news rooms and reading rooms — places, spaces, businesses and institutions set aside specifically for the reading of newspapers and magazines. Members and customers preferred to read newspapers in these rooms than at home because it was cheaper to gain temporary access to many different titles than to have permanent ownership of a single copy at home; the penny admission to Cowper’s Commercial News Room or the penny a week subscription for a church news room also paid for heat and light, scarce resources for many readers. These places also made newspaper-reading a sociable, convivial activity. There was no clear distinction between news rooms, reading rooms and libraries.20 In the Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge, these three functions occupied three separate spaces, in others, the library (a cupboard or a few shelves) may have been in the corner of a news room. Whatever their names, places devoted to the reading of newspapers were much more common than those dedicated to the reading of books, including novels.

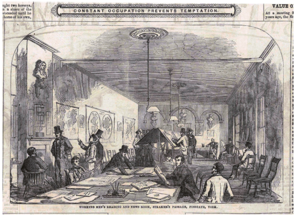

O’Neil’s news room career reveals the purposes and development of these institutions. In his native Carlisle he had been a member of that city’s first working-class news room, opened in John Street, in the poor district of Botchergate, in 1847. Mechanics’ institutes had been established around the country for more than two decades by then, but were largely shunned by working-class men and women because they were controlled by middle-class philanthropists, like the York news room in Fig. 2.6 opposite. Working-class readers preferred to set up their own news rooms (as O’Neil explained in a letter to the Carlisle Journal in 1849), because they were cheaper, could be paid for weekly rather than in a hefty lump sum every quarter or every year, they had newspapers (many mechanics’ institutes banned newspapers until the 1850s for fear of political discussions), and they were controlled by their users.21 Despite occasional problems, as in one unnamed Lancashire news room of the 1840s where discussion ‘led to confusion and bickering’ and the room had to be closed,22 conversation was integral to public newspaper-reading at mid-century, mixing oral and print cultures. Many news rooms were open on Sundays, working men’s only day of rest. In 1851, O’Neil and his fellow newspaper-readers attracted national attention when they opened a new, purpose-built news room in Carlisle’s Lord Street, of which O’Neil was secretary (Fig. 2.7).23 By 1861, Carlisle had six working-class reading rooms, with a total membership of 800–1,000, twice as many as the mechanics’ institute.24 These rooms represented a huge amount of time, money and effort that working men were prepared to invest in creating their own places devoted primarily to reading and discussing the news.

Fig. 2.6. Working men’s reading and news room, York, set up by middle-class benefactors. British Workman 20, 1856, p. 78. Used with permission of the Nineteenth-Century Business, Labour, Temperance & Trade Periodicals project, www.blt19.co.uk, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 2.7. Lord Street working men’s news room, Carlisle, from Illustrated London News, 20 December 1851, p. 732. Used with permission of University of Central Lancashire Special Collections, CC BY 4.0.

In Preston there was a handful of small trades union and commercial news rooms at mid-century, but most were provided by middle-class religious or social reformers, like the York room in Fig. 2.6. Church-sponsored reading rooms aimed at working-class adults flourished in the 1850s and 1860s. In the 1850s, rooms in at least five Church of England parishes opened in connection with mutual improvement societies (it is not known whether the opening of five in five years was due to inter-parish competition or a diocesan or national initiative). The 250 members of St Peter’s Young Men’s Club paid 1d per week in 1861 for

a reading room supplied with the leading papers; a library, containing 400 volumes; educational classes, three nights a week; a conversation room, where bagatelle, chess, draughts &c. are allowed; and an excellent refreshment room […] The club […] affords to the working man opportunities for spending his time rationally and instructively, without resort to the pot-house, where his money is wasted, and himself ultimately reduced to beggary.25

There were larger rooms such as the mechanics’ institute (60 news room members in 1852, rising to 75 in 1854), the Winckley Club (150 members in 1861), and the Literary and Philosophical Institute. Paternalistic mill owners such as John Goodair provided workplace libraries.26 As we saw on our walk, there was a mixed economy of news rooms in Preston at the start of the period.

News rooms were not only spaces in which to read, they also operated as sellers of second-hand newspapers and magazines. They recouped some of the cost of the publications by auctioning them to their members and the general public, in quarterly or yearly sales that functioned as a futures market in second-hand papers. Members bid for the right to take away daily papers the following day, weekly papers a few days after publication, and monthly and quarterly periodicals as soon as the next issue arrived.27 Typically, a local auctioneer would ensure that these sales were entertaining and dramatic events, teasing successful bidders about their reading preferences, and poking fun at the relative popularity of each local paper, particularly if a publisher or editor was present. A newspaper might give a complete list of auction prices for each title if they could be made to show the paper’s value to be higher than its competitors.28

The proceeds provided a substantial proportion of news rooms’ income, at least in the early part of the period. The Winckley Club spent £99 2s 5d on newspapers and periodicals in the year to April 1851 (the largest single item of expenditure), but recouped £24 7s 4½d from selling the back copies to members.29 Members of Mudie’s circulating library, the largest in the UK, could buy second-hand reviews and magazines by post.30 The enduring value of used newspapers is shown by an appeal for reading material from the curate of St Paul’s church, for a parish reading room: ‘We would promise to send for the papers, keep them clean, and return them at any time that might be wished.’31 Private ownership of newspapers and periodicals was thus available at reduced rates, through a recirculation system that challenges ideas of the newspaper as ephemeral.32

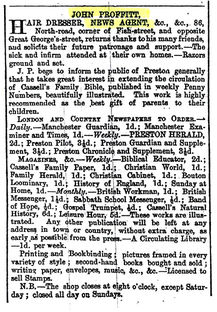

There were more news rooms than newsagents in Preston in the 1850s, if by newsagent we mean a shop mainly selling newspapers and periodicals. Buyers were more likely to get their paper from a bookshop, such as that of James Renshaw Cooper in Bridge Street, Manchester, where ‘the doorway of the shop was garnished […] with placards announcing the contents of the different local newspapers of the day’.33 In Preston, Mr John Proffitt ran one of nine businesses described as newsagents around 1860. An advertisement (Fig. 2.8) for his shop on the main north-south route through Preston tells us a great deal about newsagents at the start of the period. Although most of the text is devoted to newspapers and periodicals, he describes himself as a ‘hair dresser’ first, ‘news agent’ second. This was a time when newsagents, more commonly known as news-vendors (also spelled ‘venders’) or newsmen, were starting to distinguish themselves from booksellers and grocers, but a shop devoted mainly to papers and magazines was still a rarity. As well as cutting hair and sharpening razors, Proffitt also offered printing, bookbinding, picture-framing, stationery, second-hand books and a circulating library. At this time it was the norm for a purchaser to buy their paper in a grocer’s or corner general store, a bookshop, stationer’s, or tobacconist’s, even fruit-shops, oyster-shops or lollypop-shops, as Wilkie Collins found in his survey of sellers of ‘penny-novel Journals.’34 Newspaper-selling was still only a part of other types of business, but the huge expansion in local papers (and national magazines) was about to change the shopping ecology of Preston and every other town in the country.

Fig. 2.8. Advertisement for John Proffitt, ‘Hairdresser, news agent, &c &c’. Preston Herald, 1 September 1860, p. 4, British Library microfilm, MFM.M88490 [1860]. © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

Ten miles away in Blackburn, the main agent for papers from Preston in 1849 was bookseller Edgar Riley

whose shop […] was the only news shop in the town that afforded elbow room, and elbow room was needed where many hundreds of large newspaper sheets had to be folded within an hour or so, before they could be sold singly to customers […] Into his shop, about eight o’clock a.m. on Saturdays, were hauled three parcels of papers from Preston. The biggest was the parcel of Guardians. The Chronicles and Pilots likewise made good sized parcels. With deftness, Mr Riley, at the back of the shop, stood whipping the papers into their proper folds as fast as he was able, whilst the people poured in and out in a stream to buy their copies.35

Newsagents’ shops could also serve as informal reading rooms, where reading and discussion was combined. In Clitheroe, Mr Fielding’s shop became the ‘rendezvous of professional men and others on their way to business, each of whom bought a paper to see how the world was wagging […] Fielding’s shop was the forum for the discussion of local and imperial politics […]’.36 In Rochdale in 1856, Joseph Lawton, shopkeeper and founder of the Rochdale Observer, allowed the young James Ogden to read without buying:

to have the run of a newsagent’s shop at that time, before reading rooms for young people and free libraries existed, was, to a studious and, in literature a ravenous lad, a perfect Godsend […] when seated at his counter, I was immersed in the news of the day, the purchase of which was beyond my slender resources […]37

Just as news rooms acted as newsagents, so newsagents’ shops became news rooms.

At mid-century, newspaper-readers were physically separated according to class and gender, at least in public. On our walk we passed different reading places for different classes. Even outside newspaper offices, middle-class men probably read the paper in their own groups, while working-class men who clubbed together to buy a shared copy would stand separately. If it was difficult for working-class men to gain access to a newspaper, it was even more so for working-class women, who were less likely to use pubs, while many public reading rooms (including some church-sponsored ones) appear to have been male spaces. Women with a news addict such as O’Neil in their family may have seen or heard the paper at home if their menfolk paid a penny for one of the cheap weekly papers that launched in the late 1850s, or managed to get hold of a second-hand paper. Servants in middle-class houses probably had access to the newspapers and magazines bought by their employers, but in general, working-class readers had fewer opportunities to read or hear a newspaper.

1875

If we were to repeat our short tour past some of Preston’s reading places a generation later, in 1875, we would find a changed town, unmistakably Victorian in its Gothic public buildings and its terraced streets laid out in grids, where newspapers are bought and read in different places, and in different ways. The population has increased by almost half in two decades, from around 70,000 to more than 100,000. The traditional lull of a Saturday afternoon has gone, as most of Preston’s workers have been granted a Saturday half-day holiday in the last few years. Pubs such as the Cross Keys in the far corner of the market square still supply newspapers for customers. On the right of the Cross Keys is a passageway, Gin Bow Entry. Through the passageway and up the stairs is the Liberal Working Men’s Club with its news room full of newspapers, read and argued over by reform-minded men.38

Back out on the square, Uncle Ned the ballad-seller looks older and frailer. He

wore a battered shabby tall hat and a frock coat which was very shiny and decidedly the worse for wear. He held a long pole across the top of which was fixed a shorter pole at right angles in the form of the letter T. Over this was drawn through a corded loop a big bundle of long printed sheets illustrated with a crude picture at the top swung to and fro with the wind and the motion of the man’s body. He sung the doggerel verse to some popular tune of the day […]39

Some of the ballads are traditional songs, but others celebrate more recent news. If we walked a few hundred yards down Church Street, we could visit the shop where his wares are printed by John Harkness, one of Lancashire’s most prolific ballad publishers.

But instead we walk up the canopied steps of the town hall, into its cool marble corridors, to the Exchange Commercial News Room, which has been housed here since the new town hall opened in 1867, for the convenience of the town’s businessmen. It is closed on a Saturday, but if we peep in we can see tidy piles of newspapers and magazines on the polished oak tables; there are some inkstands and a letter box, newspaper stands on other tables, chairs, two long benches with back-rails, a blackboard, a towel rail, a table with toilet materials, two umbrella stands, and dotted about the room, six spittoons. If it was a weekday we would hear the printing telegraph machine sporadically chattering out its market prices and news from the Press Association onto a narrow ribbon of paper.40 Sometimes, when the window is open, members can hear the centuries-old songs of the ballad seller at the same time as the electro-mechanical chuntering of the telegraph machine. The list of rules on the wall stipulates no smoking and no dogs, and requests ‘that no person detain a newspaper longer than fifteen minutes after its being asked for; and that no preference be shown by the exchange of papers.’41 When the room is open, groups of friends and like-minded acquaintances cluster together to read and discuss the news, forming little ‘interpretive communities’:

Occasionally on a very cold day there was only one fire the consequence being that all political creeds and set classes of theologians were pitched into one corner […] when there was no doubt but that they desired being seated with their own fellows […]42

Membership has recently been reduced to £1 per year, since the news room is struggling for members.

Back outside, and onto Fishergate, the Magnetic Telegraph Company office with its own subscription news room has gone, closed when the telegraph companies were nationalised in 1870. The Liberal Working Men’s Club had their own news room there for a while, but they too have moved. We pass Glover’s Court, glimpsing David Longworth’s printshop, where he produces his monthly Preston Advertiser, and walk down the busy main street and into Cannon Street, past two bookshops, James Robinson’s and Isaac Bland’s. The former mechanics’ institute has recently been vacated by the printing department of the Preston Guardian and is now the printing office of the Preston Chronicle. On our way to Avenham Lane we can glimpse John Farnworth’s newsagent’s shop.

We are braver this time, and continue walking east, into some of the poorest parts of Preston. Twenty years on, there are more newspaper-reading and, in particular, newspaper-vending places to see. There is Bell’s little shop, selling newspapers among its other necessities, up Oxford Street; on Hudson Street, two newsagents, Phillipson’s and Pilkington’s, past Syke Hill on our left, and Hannah Odlam’s newsagent’s. These paper shops are similar to those found in London and elsewhere:

established for the sale of cheap periodicals and newspapers, bottles of ink, pencils, bill-files, account books, skeins of twine, little boxes of hard water colours, cards with very sharp steel pens and a holder sown to them, Pickwick cigars, peg-tops, and ginger-beer. Cheap literature is the staple commodity; and it is a question whether any printed sheet costing more than a penny ever passes through the hands of the owner of one of these temples of literature. One of the leading features in these second-rate newsvenders’ windows […] is always a great broadsheet of huge coarsely executed woodcuts [probably the front page of the Illustrated Police News].43

Now we turn off the busy, respectable Avenham Lane and into the shabbier Vauxhall Road. Straight ahead is St Augustine’s Catholic church and its Men’s Institute, with its reading room and library. Along Silver Street, past Wareing’s grocer’s shop, with its pile of Preston papers on the counter, into Duke Street, past Thomas Blezard’s newsagent’s shop, up Brewery Street past Wareing’s little shop, which handles local papers along with everything else, and back along Queen Street.

We pause at a crossroads. On our left is the Weaver’s Arms, whose meeting room is now the Conservative Reading Room, and facing the pub, across Queen Street, is St Saviour’s new Anglican church. Beyond the church, one of the schoolrooms is used by the church’s Mutual Improvement Society, for their reading room and library. We head back to the relative safety of Avenham Lane, up the hill past George Holland’s newsagent’s, and into a different world. The news room of the elegant Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge is still busy, and now offers members the use of Mudie’s circulating library, in addition to its own stock.

In Winckley Square, the Literary & Philosophical Institution (another branch of Mudie’s) is quiet. Membership has fallen in recent years, and in 1867 they were forced to sell their huge building to the corporation. The more convivial Winckley Club next door, founded on less intellectual principles, is still thriving on billiards, newspapers and claret. Back on Fishergate we pass the shop of Chas Bond, bookseller, printer and fancy stationer, and Robinson’s new and second-hand bookshop. Across the road is James Akeroyd’s bookshop. Here are Cuff Bros’ bookshop, Clarke’s Preston Pilot office on the corner of Winckley Street, which also sells books and newspapers, then next door another printer and bookseller, Henry Oakey, whose shop is also a depot for the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK). Opposite is the YMCA, with its reading room ‘well supplied with Papers and Periodicals’, and a few doors along, the new post office, now doubling as a telegraph office, where crowds often gather to hear important news. There is Evan Buller’s Catholic bookshop, also selling newspapers and magazines. A hundred yards further is a bookshop and newsagents’ run by the Chronicle’s former owner, William Dobson, and almost opposite is the new home of the Central Working Men’s Club, with its ‘commodious newsroom, fronting Fishergate’, available for a 1/6 quarterly membership fee. In one of the club’s previous homes, in Lord Street, its news room presented a cosy picture, far preferable to the cramped, noisy and badly lit homes of its members:

The fire was blazing cheerfully, the paper and pictures upon the walls were as beautiful as any artist could desire, and the general effect was decidedly one of comfort and quiet enjoyment. The library or reading room, as the adjoining apartments were designated, was furnished in a similar manner, only books took the place of newspapers.44

In Barrow, some members of the Working Men’s Club wanted somewhere more private than the reading room, but this was discouraged by the Reading Committee, who resolved in 1883 ‘that parties in habit of taking periodicals with them whilst in the water closet be requested by the steward to discontinue such practice’.45

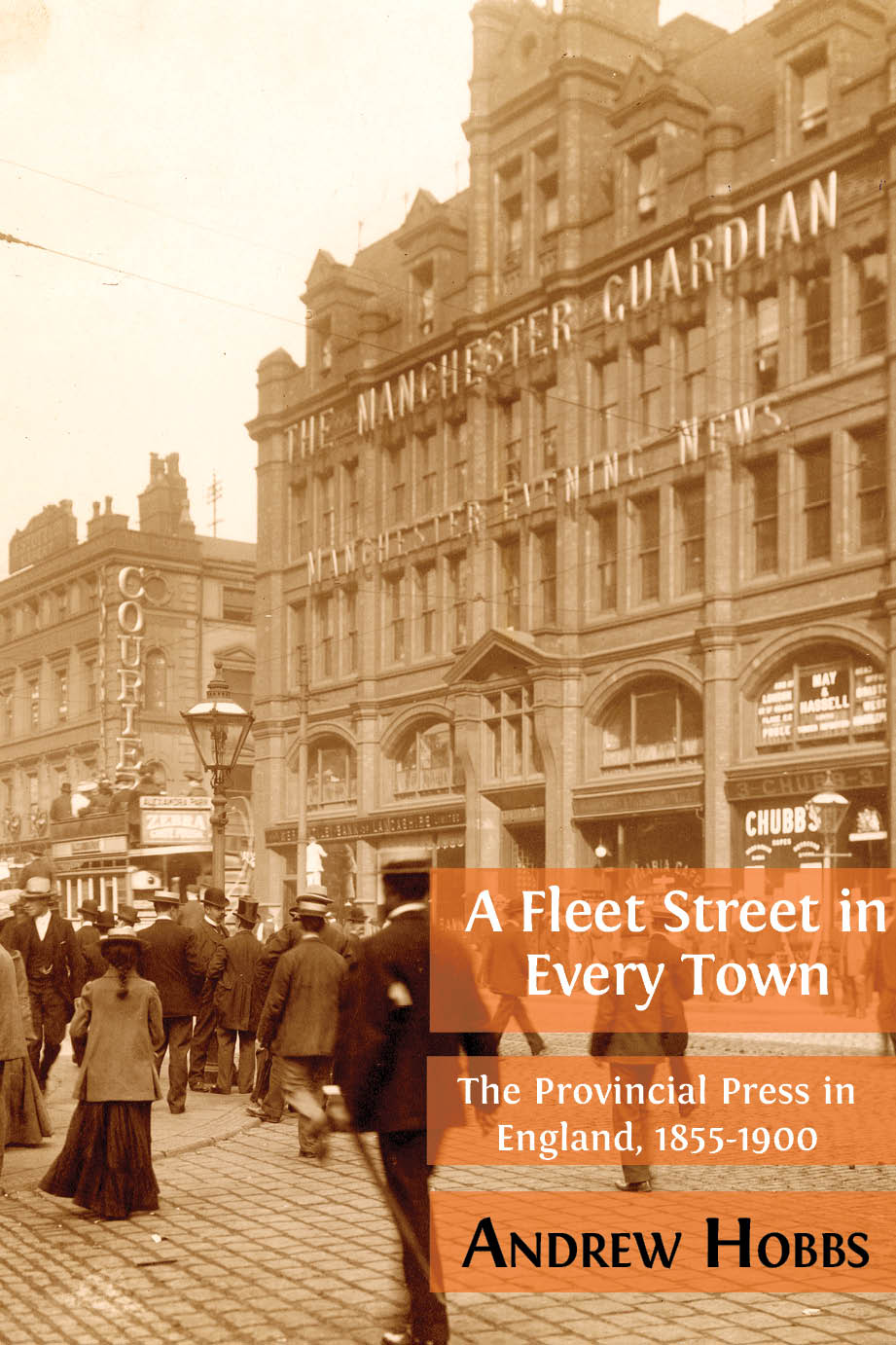

Back in Preston, on the same side of the street the town’s three main newspapers are clustered together; all three sell other newspapers, as well as their own. The Herald, next door to the working men’s club, comes first, then the Chronicle five doors down. Next door but one, a bust of William Caxton perches atop the rather grand three-storey stone-fronted home of the Preston Guardian (Fig. 2.9, next page), the town’s most successful paper, and the only one to have a purpose-built office. The local paper was changing the fabric of Preston’s main street, as it was up and down the country.

There were significant shifts in the places of newspaper-reading between the 1850s and the 1870s — many more shops sold newspapers (and magazines), which means that many more people were buying their own copies to read at home. More schools had been built, in which more children were reading newspapers, and there were fewer news rooms, with those that survived tending to be run by political parties, clubs and societies, as a membership benefit. The number of newsagents increased steeply, from less than a dozen in the mid-1850s to more than fifty in the mid-1870s; one local trade directory, Mannex’s, recorded a rise from thirty-four to fifty between 1874 and 1877. This is no doubt partly due to more shops being reclassified under the emergent category of newsagents rather than by the other goods they sold, but the trend is consistent across all trade directories, and also in the Census.

Fig. 2.9. Preston Guardian offices, Fishergate, the town’s first purpose-built newspaper premises (Preston Guardian, 17 February 1894). British Library MFM.M40487-8. © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

Other small shops seem to have sold newspapers as a sideline, and so were not classified as newsagents. For example, in 1870 there were sixty-six places in Preston selling the Preston Herald (and other newspapers too, probably), but only half of them were classified as newsagents in the trade directories of the time.46 The other stockists were confectioners, a beershop, two beerhouses, grocers, a pork dealer, a pawnbroker, two ‘furniture brokers’, two chemists, and four milliners and hosiers. These examples convey the variety of shops and offices where one might encounter reading matter for sale, and the types of businesses that developed into newsagents.47 Further, there were no clear demarcations between new or second-hand bookshops, booksellers or newsagents, shops or libraries. W. H. Smith was not unusual in selling newspapers, new and second-hand books and periodicals, and operating a circulating library, which included ‘the Quarterly Reviews and first-class Magazines’ as well as books, like its rival, Mudie’s.48

Newspapers of similar political persuasions sold each other’s papers from their offices, such as the Conservative Preston Pilot and the Herald, even though they were commercial rivals. Political rivals, on the other hand, did not co-operate — the two Liberal papers did not sell the Tory Herald, nor did Clitheroe’s Liberal, Quaker newsagent Mr Fielding, putting principle before profit.49 Reading places, as well as reading matter, were differentiated by politics, and the distribution of news was influenced by principles as well as profit.

Supply and demand fed this growing army of newsagents. On the supply side, there were more newspaper and magazine titles, selling more copies, at lower prices. On the demand side, literacy was rising steeply, so that many people who had previously listened to a newspaper were now reading one themselves; wages had increased while working hours had fallen, creating more money and leisure time for reading — the Saturday half-holiday had become widespread in textile towns such as Preston by the early 1870s, for men as well as women and children.50 Between 1853 and 1873 newsagents spread to districts outside the town centre in particular, which were populated by textile worker households whose relatively high disposable incomes drove the growth of music hall, the seaside tourism industry and professional football. Did the reading habits of this culturally dynamic group shape the publishing industry in equally distinctive ways?51

More newspapers bought in shops meant more newspapers read at home. This was more convenient, but required heat and light, as O’Neil’s diary entries emphasise: ‘I have been sitting at a good fire reading the Carlisle paper’ (received from his brother by post the day before), he noted in 1856.52 In winter, reading at home became more difficult and expensive: in January 1860 he wrote that ‘it was so dark I could not read unless I was standing at the window or door’, and in December 1872 he noted that ‘it has rained nearly all day and was so dark that I could not see to read very much.’53 Practical and financial considerations such as these, and the desire for company and the comfort of a drink or two, led O’Neil to continue to do most of his reading in the Castle Inn or the Liberal Club news room in Clitheroe after it opened in 1872. In Preston, an advert for a town-centre pub, capitalising on interest in the Franco-Prussian War, was headed: ‘The Latest News From The Seat of The War Can Be Read at Barry’s Hoop and Crown, Friargate’, showing the continued popularity of the pub as reading place.54

Increasingly, news rooms were provided by membership organisations, rather than operating as free-standing businesses or voluntary efforts. There was a burst of new reading rooms opened by political parties from the late 1860s, particularly around the time of the 1867 Reform Bill, which extended the franchise to working-class men in urban constituencies such as Preston. The local branch of the National Reform Union opened a reading room in March 1867, and in November 1869, within a week of each other, Preston’s General Liberal Committee opened a reading room in Fishergate and the Central Conservative Club opened in Lord Street. By 1875 there were four Conservative and two Liberal news rooms in Preston. Trades union rooms multiplied in the 1860s, and all kinds of clubs and associations offered reading rooms as a benefit for their members, such as the 11th Lancashire Rifle Volunteers, the Preston Operative Powerloom Weavers’ Association and the Spinners’ and Minders’ Institute in Church Street.55 The national movement for working men’s clubs (WMCs), launched by Rev Henry Solly in Lancaster, had some impact in Preston, with at least two set up in the town, the Central WMC in Fishergate and St Peter’s Church of England WMC on Fylde Road. The creation of reading rooms above some branches of Co-operative grocery stores introduced a significant new player into Preston’s public reading ecology. Preston Industrial Co-operative Society set up an educational department in 1875, and opened news rooms above its Ashton Street and Geoffrey Street shops the same year; in 1876 they opened two more, in Brackenbury Street and in Walton-le-Dale, two miles outside the town.56 Co-op news rooms were more widespread in other towns — in 1879 the Rochdale Pioneers Co-operative Society had eighteen news rooms, Bury’s had twelve, Oldham’s seventeen.57 These organisations all believed that offering a place to read and discuss the news would attract members.

More reading places meant more reading. O’Neil would typically read a paper once a week at the start of our period (for example in January 1861), but after the Mechanics’ Institute and Reading Room re-opened in his village of Low Moor in 1861, he mentioned reading a paper fifteen times in January 1862, or every other day, and after the Liberal Club reading room opened in 1872 he sometimes mentioned reading papers there three times a week, in addition to his reading elsewhere.58 Reading places must be factored into any calculation of how supply and demand affected developments in literacy, reading and publishing.

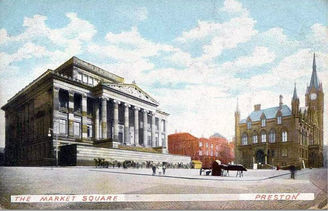

Fig. 2.10. Tinted postcard c. 1900, showing Harris Free Library (left) and town hall (right). Preston Digital Archive, CC BY 4.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/rpsmithbarney/5753101486/

1900

If we were to repeat our walk around Preston in 1900, one change would be highly visible, another hidden. A public library now dominates the town square, just as its news room dominates the town’s ecology of public reading places. Less visibly, families are now reading their own copies of a halfpenny evening paper at home.

The market square has been transformed by the enormous neo-classical bulk of the Harris free library, taking up most of the eastern side of the square (Fig. 2.10). Before it opened in 1893, a council-funded ‘free’ library had operated since 1879 in the town hall on the south side of the square, in the room previously occupied by the declining Exchange and News Room (membership had fallen from 304 in 1869 to 97 when it closed in 1878).59 The new purpose-built library features a news room and two reading rooms, one for ladies, one for men, with space for 276 people, and is more popular than the lending or reference departments.60 In the photograph below, men sit reading magazines in the reading room in the foreground, while the newspaper readers in the news room at the back have a less comfortable experience, having to stand at the high, sloping reading desks (many libraries had standing accommodation only).61 Light streams in from the large windows, bound file copies for reference are available on the windowsills in the middle, and a policeman keeps order to the right (visible in Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 2.11. Men standing to read newspapers in the news room of the Harris Free Library, Preston, 1895. Used by permission of the Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, England, all rights reserved.

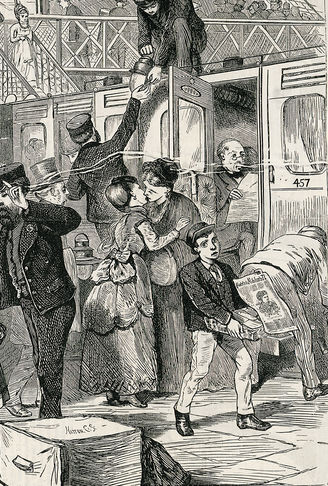

Elsewhere in the town centre, new reading rooms have opened, attached to party-political clubs — the purpose-built Conservative Working Men’s Club on Church Street, the rather grander Central Conservative Club in Guildhall Street and the Reform Club in Chapel Street off Winckley Square. If we followed the same route into St Saviour’s parish as in 1875 we would notice even more newsagents than before, each one offering a wider range of publications. Fishergate and the whole of the town is now plagued by a new sight and sound, hordes of newsboys, some of them as young as seven, noisily selling evening papers from Preston, Blackburn, Manchester and Liverpool, weekly papers and even magazines — boys from the St Vincent de Paul orphanage in Fulwood are selling the Preston-based Lancashire Catholic magazine.62 As in previous times, there are a handful of older disabled men selling papers.63 Most are shouting the headlines from the Lancashire Daily Post, as more arrive with the late special football editions; they have bought three copies for a penny, to sell at a halfpenny each.64 In 1887 Hewitson described the techniques of these news boys:

Every afternoon, one of the streets contiguous to our leading thoroughfare is monopolised by a lad, who appears to have a special faculty for picking out and bawling out the grim, the astounding, and the dreadful in the papers he has for sale. His vociferations invariably refer to the serious, the alarming, or the awful — to fires, or murders, or embezzlements, or suicides, or executions, or disasters on land or sea. The other evening, by way of catching coin, a lad of this kind resorted to the bogus localising game. He walked along the main street, now and then went into shops, and shouted out, with much nerve, “Execution in Preston.” [But] the execution related to the hanging of the Coventry murderer at Warwick!65

Fig. 2.12. Paper boy on New Street station, Birmingham, detail from ‘New Street Station Going North’, Illustrated Midland News 13 August 1870, p. 105, British Library, EWS4150. © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

If we were to go to the station at the end of Fishergate, on the platforms we would see other boys running alongside the trains as they come in, selling papers through the windows while they wait at the platform, and then running again to finish their business as the trains pull away. Figure 2.12 shows a similar scene at Birmingham New Street station. W. H. Smith’s station bookstall is busy. The growth of cheaper, smoother public transport has created new reading times and places, and national and local newsagents fed this new market.

The mechanics’ institute has amalgamated its news room and reading room (membership fell after the free library opened). The news room at the Winckley Club still flourishes, despite membership fees of four guineas for ‘town’ subscribers (three guineas for shareholders, two for ‘country’ subscribers).66

On Fishergate, the crowds outside the Lancashire Daily Post offices (shared with its mother paper, the Preston Guardian) are larger and more frequent than in the 1870s, now that this evening paper publishes a new edition almost every hour from 10am onwards, each containing new sporting results. Since the rise of professional football in the early 1880s, Preston North End supporters almost block the street every Saturday of the football season, from September to May, to wait for news of the next goal from the newspaper office. In 1900, there is the additional excitement of the Boer War. Smaller crowds gather outside newsagents for football news.67 Football has made some pubs more important as news hubs if they promote themselves as ‘football houses’ where fans and their teams gather. In Burnley, for example, the Cross Keys advertised itself as ‘THE FOOTBALL HOUSE’, where ‘RESULTS OF ALL IMPORTANT MATCHES will be exhibited in the Smoke Room EVERY SATURDAY EVENING. Telegrams Regularly Received.’68 The street is still a reading place, as seen in the 1906 postcard (Fig. 2.14) showing a wealthy-looking man in top hat and frock coat reading a newspaper as he walks down Fishergate. In Salford, groups of working-class men and boys read racing pages and comics on street corners into the early twentieth century.69 Public transport such as the passing tram also became a popular reading place, the newspaper providing a barrier against the unwelcome looks of strangers, among other uses.

Fig. 2.13. Man reading newspaper in Fishergate (to left of tram), Preston, 1906, postcard. Used by permission of Preston Digital Archive, CC BY 4.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/rpsmithbarney/3082785495/

If we knocked on doors in any part of Preston at the turn of the century, we would find newspapers being read at home, particularly the local evening paper. It is the paper mentioned most often by Elizabeth Roberts’s working-class interviewees in Preston, where two-thirds of them recalled parents reading a newspaper at home, usually the Post. A photograph of Mrs Annie Stephenson, mother of countryside access campaigner Tom Stephenson (not reproduced here) illustrates the difficulties of reading at home, and explains why many still used more public, sociable reading places. Although probably taken in the early twentieth century, the scene would have been similar in the second half of the nineteenth century. She has tilted the newspaper flat to catch the light from the kitchen range, the only source of illumination.70 Similarly, a candle can be seen on the mantelpiece of the man pausing from reading in Fig. 2.14. The spread of gas lighting made a huge difference, replacing the cost and danger of candles and rush lights and making reading at night easier and cheaper.71

Fig. 2.14 Man by fireside rests from reading The Cornishman. Reproduction of water colour painting by Walter Langley, ‘One Man One Vote’, Cornish Magazine 1 (1898), opp. p. 161. Author’s copy, CC BY 4.0.

Many working-class people read newspapers sitting on their doorstep, a literally liminal space between the public and the domestic, as in the St Helens area, where ‘in the summer the men sit akimbo on their door-steps, clad mostly in their shirt-sleeves, and they read their favourite organs with a thoroughness which puts to shame many of us who have fuller opportunities.’72 Even if home was the workhouse, reading matter was still provided, with inmates having access to newspapers and magazines provided by well-wishers such as Mrs Cummings of the Old Dog Inn, presumably sending publications that had been read in her pub (most workhouses provided books, magazines and newspapers for inmates, according to surveys conducted by readers of the Review of Reviews in 1890).73

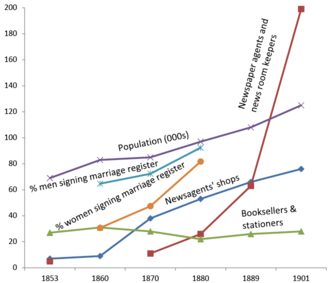

By 1901, home reading was supplied by seventy-odd newsagents in Preston, half as many again as in the mid-1870s (see Figs. 2.15 and 2.16), with similar growth in working-class districts of Blackburn.74 The emergence of the newsagent as a distinct trade can be seen in the ‘sedimented’ signs of Fig. 2.16. ‘Newsagent’ has gone from secondary title in the older sign over the window (‘stationer, newsagent, toy dealer, tobacconist, &c’), to primary title in the newer sign over the door (‘newsagent & stationer &c’). Small grocers’ shops that would not describe themselves as newsagents also continued to sell newspapers.75 The population of Preston increased by roughly fifty per cent during the period, and the proportion of people able to read probably doubled, yet the number of paper shops increased tenfold, and the number of people working in such shops by even more (see graph below; the steeper rise in the number of ‘newspaper agents’ and ‘news room keepers’ recorded in the Census is probably explained by the growing staff of each shop). The development of newsagents, from a sideline of bookselling and grocery to a distinct type of shop, can be seen in the fact that all seven ‘news-venders’ identified in 1853 were also classified as booksellers.76 But by 1901, only twelve newsagents out of seventy-six were also booksellers. They were serving not so much new audiences as new purchasers, helping to create a hugely expanding print market and becoming part of the physical and cultural landscape of urban areas.

Fig. 2.15. J. Smith, ‘newsagent and stationer’, Fylde Street, Preston, c.1909. A newsagent of this name on this street first appears in trade directories in 1869. Reproduced by permission of Mr William Smith, Preston, son of William Willson Smith (left) and grandson of shop owner Jane Smith, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 2.16. Three rival Bristol newspapers are advertised outside the shop of newsagent Sarah A. Spiller in St Georges Road, Bristol, 1906. Postcard, Bristol Archives, 43207/35/1/50, CC BY 4.0, http://archives.bristol.gov.uk/GetImage.ashx?db=Catalog&type=default&fname=43207-35-1-050.700x700.jpg

Fig. 2.17. Preston booksellers and newsagents, with indices of readership, 1853–1901, author’s graph, CC BY 4.0.77

Preston’s public library changed the town’s news-reading ecology. On the one hand it took away readers from small associative news rooms and made the reading experience less social and sociable; on the other, it provided easy access to a huge amount of serial print for all social classes. It opened in 1879, after the peak of Preston’s news room provision in the 1850s and 1860s (Table 2.1 below), but this apparent decline may be misleading. The news rooms of the last three decades of the century were larger — pre-eminently the free library, the two Conservative clubs and the Liberal club — so the actual numbers of readers using public reading institutions may not have declined. Exceptions to this trend towards fewer, larger news rooms were the six smaller reading rooms of the Co-op, the single biggest provider of reading rooms in the town from the 1880s to the early twentieth century. There was a decline in middle-class institutions and free-standing news rooms not connected to a club or organisation, but an increase in working-class ones, perhaps reflecting a middle-class shift from reading in public to reading in private.

Table 2.1. Approximate numbers of news rooms, reading rooms and libraries, Preston, 1850–1900.78

|

Pre-1850 |

1850s |

1860s |

1880s |

1890s |

|

|

5 |

27 |

27 |

24 |

16 |

16 |

However, many people still preferred to read or hear newspapers and periodicals in pubs and less formal news rooms, where they could also discuss the news with like-minded people, whilst drinking and smoking. Like curates ‘who meet and converse, and write letters and postcards after consulting the clerical journals’ at a London public library in the 1890s, the wealthy members of the Winckley Club were at odds with more ‘respectable’ middle-class readers who were migrating away from public reading places.79 They still valued the convivial atmosphere of a club room, in which oral and print cultures were combined, even though they could afford to buy their own newspapers and magazines, and read them in their comfortable homes. Modern-day book groups and online ‘social reading’ behaviour are signs of a continuing desire to talk to other people about what we read, and a reminder of the corporeal and geographical realities of reading communities and interpretive communities.

There is some truth in the idea that news rooms and reading rooms, including public libraries, were intended by middle-class reformers to control working-class reading — particularly the mechanics’ institute and the reading rooms set up by the churches in the 1850s and 1860s. The aim of keeping men away from the pub, to prevent drunkenness and poverty (and perhaps to limit political discussion) was behind reading rooms such as the Temperance Hall in the 1850s and 1860s, the Alexandra coffee tavern, opened in 1878, and reading and recreation rooms opened for dock workmen in 1886.80 A similar impetus drove the campaign for a free library.

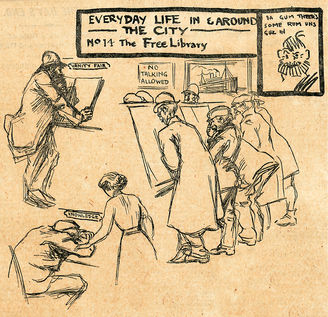

The public library quickly came to dominate reading room provision, especially for the less well-off. By 1884, an average of 1,492 visitors used the free library reading room every day.81 When a member of Preston Co-op’s Educational Committee suggested opening ‘a grand central reading room equal to any political room in the town’ in 1891, a voice from the floor of the meeting shouted ‘The Free Library will do’.82 Its arrival led to another fall in membership of the news room of the mechanics’ institute, especially among less wealthy subscribers. The free library brought a significant proportion of public reading experiences under state control, however benevolent, as symbolised by the policeman in the photograph (Fig. 1.5), and its rule of silence influenced the style of reading, and began to break the old association between reading and discussing the news (note the ‘No talking allowed’ sign in the Sheffield news room of 1912, Fig. 2.18 opposite).83 A writer in All The Year Round in 1892 noted ‘the somewhat oppressive silence that pervades the free library in general’:

Everywhere you see posted up, ‘Silence!’ ‘Silence is requested,’ and so faithfully is the injunction carried out by the public, that after a round of free libraries one has an impression of belonging to a race that has lost its powers of speech. The silence really becomes oppressive, and one longs to hear a laugh or a whistle, or even a catcall, to break the solemn stillness of the scene.84

Fig. 2.18. Silence ruled in Sheffield public library’s news room. Detail from ‘Everyday life in & around the city, no.14, The Free Library’, Yorkshire Telegraph and Star Saturday evening ‘Green ‘Un’, 13 April 1912, p. 4, British Library, NEWS5890. © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

Within a year of opening, the free library had become Preston’s best stocked and best used reading room. Hewitt’s analysis of a similar change in Manchester’s reading ecology leads him to conclude that the public library weakened the link between oral and print culture, and undermined the disputational newspaper-reading of associational news rooms. Its ‘stress on the individual, private experience of print’ damaged Manchester’s public sphere (see Figs. 2.19 and 2.20 below).85

Fig. 2.19. Rochdale Road branch library reading room, Manchester, c.1899. Allocated spaces for two copies of the Manchester Evening Chronicle are visible at right, and spaces for the Pall Mall Gazette, Illustrated London News and Graphic on the left. Flat caps and bowler hats are visible, worn by working-class and middle-class men respectively, but no top hats, as in the Preston photograph. Photograph by Robert Banks, from William Robert Credland, The Manchester Public Free Libraries; a History and Description, and Guide to Their Contents and Use (Manchester: Public Free Libraries Committee, 1899), p. 48. Author’s copy, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 2.20. Ancoats branch library reading room, Manchester, c.1899. Photograph by Robert Banks, from Credland, p. 96. Author’s copy, CC BY 4.0.

However, the picture is more complex. The chronology of Preston’s reading places shows that the free library did not kill off a rich ecology of associative reading places, as Hewitt describes in Manchester; most of Preston’s free-standing news rooms, unattached to any organisation, devoted solely to the reading of newspapers, had already closed before the public library opened, and a major strand of associative reading places, sponsored by the Co-op, continued into the twentieth century.86 Further, many working-class campaigners were involved in the movement for a public library, and any attempt to control reading material and behaviour had to be negotiated with the readers. In practice, Preston’s chief librarian allowed a wide range of reading matter, and refused to censor betting news on principle. Some libraries attempted to retain the atmosphere of more relaxed reading places, as in Chorley with its smoking room, where readers could sit, smoke and read the papers, opened in 1899 as an alternative to the pub.87 And, while limited social mixing had always taken place in inns and public houses, the free library was Preston’s first reading institution not to discriminate by class, gender, politics or religion, a neglected aspect of these institutions.

O’Neil’s reading habits remind us of the agency of the individual reader, who chose to read newspapers in many different places. O’Neil read at home, in a mechanics’ institution, in the pub and in a Liberal club reading room, both public and private places with a range of rules and a tolerance of discussion. As the All The Year Round writer acknowledged, people had a choice, and many working-class people chose to stay away from the public library: ‘The silence and good order are a little too much for them; they miss the freedom, the chaff, the jokes of out-of-doors and the full-flavoured hilarity of the public house.’88 The proliferation of newsagents created a free trade in print, outside the control of any one group, so that purchasers were able to buy salacious Sunday newspapers, penny dreadfuls or radical and atheist magazines, according to taste, although most working-class readers were more conservative. Besides the pub and the street, the capitalist publishing market had given working-class people the freedom to create their own reading worlds — a democratisation of print.

The news room and reading rooms were the largest departments of Preston’s public library, suggesting that newspapers and magazines were still seen as educational at the end of the century. An older perception of newspapers, as containing dangerous political information, to be kept out of the hands of working-class readers, had died out before the 1850s.89 By 1869 the Vicar of Preston could defend the right of workhouse inmates to read the local newspapers, even on a Sunday.90 At this time churches, middle-class reformers, some factory owners and both political parties in Preston were encouraging working-class news reading by opening news rooms. Previously, only Radicals had encouraged such behaviour. ‘What was outspoken, radical and proscribed […] became something close to the cultural and political orthodoxy.’91 In the 1890s there was debate in Preston’s co-operative movement over the value of their news rooms, but attempts to close them failed, with one supporter arguing that educational activities attracted new members, with news rooms a major factor.92 There is little evidence here for the thesis that, from the 1880s, newspapers were no longer seen as educational or morally uplifting.93

Conclusions

The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed an exponential growth in the number of places where news was read and bought. On our tours of Preston at the beginning, middle and end of the period we saw news rooms appear around the town, for public reading and discussion of newspapers, followed by a new type of shop, the newsagent, meeting an exponentially growing demand for cheap newspapers and magazines; we saw the buyers of these publications take them to their homes, for individual and family reading. We saw new buildings erected and adapted by the local press, which attracted crowds of news-seekers who became a weekly fixture outside their offices. A public library was opened, and then a bigger one took its place at the centre of the town. This micro-geography of newspaper-reading has highlighted a trend from sharing newspapers in public places, associated with discussion and conversation, to reading them silently or buying them for private consumption.94 However, there was also continuity in newspaper-reading in the pub and on the street.

The greatest change was the growing number of places where working-class men, women and children could buy or read the local newspaper: until the opening of the free library and the Co-op reading rooms, poorer readers’ access to reading material was limited, segregating them from middle-class readers.95 By the end of the century, thanks to the Co-op, they had more of their own news rooms than ever before, they had access to a publicly funded central library news room, and newsagents’ shops had spread to even the poorest parts of the town. Rapid changes in the content of newspapers, such as sport and serialised fiction (previously found mainly in magazines) reflected the growing power of working-class readers. Meanwhile, middle-class news rooms such as the Exchange, the Literary and Philosophical Institute and the mechanics’ institute declined more than working-class ones, and there is no evidence that working-class readers stopped reading the news in pubs. The shift from public reading to domestic reading, akin to Raymond Williams’s concept of ‘mobile privatisation’, was probably greater among the middle classes, whose use of public reading places declined.96 Their homes were also more conducive to reading. The trend appears to be more complex among working-class readers: by the end of the century they could also afford to buy cheap reading matter from newsagents and read it at home, but many continued to read in pubs, in the free library and in their own public reading places, such as political clubs and Co-op reading rooms. Even at the end of the century, reading a newspaper alone, in silence, was not a preferred, ‘natural’ default.

Most of these reading places, whether news rooms or libraries, newsagents or bookshops, were devoted to newspapers and magazines rather than books, confirming the centrality of periodical print to Victorian culture. Magazines and newspapers, particularly local papers (see Chapter 6), were central to the reading world of a provincial town in the second half of the nineteenth century. They physically changed the town. In the next chapter we will see how they changed the rhythms of readers’ lives.

1 Robert Darnton, ‘First Steps Towards a History of Reading’, in The Kiss of Lamourette: Reflections in Cultural History, ed. by Robert Darnton (London: Faber & Faber, 1990), p. 167; see also James A. Secord, Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 338.

2 Preston Guardian (hereafter PG), 6 October 1860.

3 Letter from ‘One Who Pays His Subscription’, Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC), 6 July 1864.

4 Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge, annual reports for 1855, p. 5; for 1858, p. 6, University of Central Lancashire, Livesey Collection, uncatalogued; PC, 30 June 1855.

5 William Pollard, A Hand Book and Guide to Preston (Preston: H. Oakey, 1882), p. 142. Letter from ‘A Working Man’, PC, 14 February 1857.

6 Malcolm T. Mynott, The Postal History of Preston, Garstang and the Fylde of Lancashire from the Civil War to 1902 (Preston: Preston & District Philatelic Society, 1987), p. 131.

7 John O’Neil, The Journals of a Lancashire Weaver: 1856–60, 1860–64, 1872–75, ed. by Mary Brigg (Chester: Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1982), 28 March 1857.

8 PC, 18 December 1861.

9 Tom Smith, ‘Religion or Party? Attitudes of Catholic Electors in Mid-Victorian Preston’, North West Catholic History, 33 (2006), 19–35 (p. 31).

10 James Vernon, Politics and the People: A Study in English Political Culture, c. 1815–1867 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 142–43. Vernon is also mistaken in his assertion that ’provincial communities relied entirely on the national press for their news of important national events’ before the 1860s (p. 143).

11 ‘Preston Annual Licensing Session Applications for more spirit licences. Opposition meeting in the temperance hall’, PC, 18 August 1860.

12 Richard Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), pp. 200–201; Arthur Aspinall, Politics and the Press, c.1780–1850 (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1973), pp. 9, 29; Lionel Robinson, Boston’s Newspapers (Boston: Richard Kay Publications, for the History of Boston Project, 1974), p. 8.

13 For example, ‘I could not get up to Clitheroe it was so wet but I got a newspaper and read it’ (Saturday 27 September 1856).

14 O’Neil diaries, Saturday 24 October 1857.

15 Cobbett’s Political Register, 26 September 1807, cited in Aspinall, p. 11.

16 William Pilkington, The Makers of Wesleyan Methodism in Preston, and the Relation of Methodism to the Temperance and Teetotal Movements (Preston: Published for the author, 1890), p. 183.

17 John Denvir, The Life Story of an Old Rebel (Shannon: Irish University Press, 1972), pp. 15–16.

18 Richard Jefferies, ‘The Future of Country Society’, New Quarterly Magazine, 8 (1877), 379–409 (p. 399).

19 Lucy Brown, Victorian News and Newspapers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985).

20 O’Neil used the terms ‘club room’, ‘news room’ and ‘reading room’ interchangeably, to describe Clitheroe Liberal Club’s reading facilities.

21 Mary Brigg, introduction to O’Neil diaries, pp. ix-xii.

22 The Spectator, quoted in ‘Prosperous Lancashire’, PC, 24 October 1891.

23 Henry Morley, ‘The Labourer’s Reading Room’, Household Words, 3 (1851), 581–85 (p. 583 ff.). The image of the Carlisle room (Fig. 2.7) appears to be of the opening ceremony, with the mayor in the centre of the gallery, some men singing around an organ to the right, and women present, in their shawls and bonnets. The illustration tells us little about how the room was used, in contrast to the image of the York room (Fig. 2.6), which shows newspaper stands at the rear, maps on the wall to interpret the foreign news, and at least two conversations, on the left.

24 Robert Elliott, ‘On Working Men’s Reading Rooms, as Established since 1848 at Carlisle’, Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, 1861, 676–79. The author, a doctor, was a friend of O’Neil’s (Brigg, introduction to O’Neil diaries).

25 PC, 31 October 1861. See similar descriptions of St Luke’s Conservative Association, Preston Herald (hereafter PH) supplement, week ending 17 September 1870, p. 3, and Preston Temperance Society annual report for 1862, p. 7, University of Central Lancashire, Livesey Collection, LC M [Pre]).

26 [John Goodair], ‘A Preston Manufacturer’, Strikes Prevented (Manchester: Whittaker, 1854), cited in H. I. Dutton and John Edward King, ’Ten per Cent and No Surrender’: The Preston Strike, 1853–1854 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 85.

27 For example, ‘Public sale of newspapers, Ripon’, Leeds Mercury, 5 January 1839.

28 For example, PC, 6 January, 1872.

29 Winckley Club minute book, Lancashire Archives LRO DDX 1895/1.

30 See an 1890 list reprinted in Laurel Brake, ‘“The Trepidation of the Spheres”: The Serial and the Book in the 19th Century’, in Serials and Their Readers, 1620–1914, ed. by Robin Myers and Michael Harris (Winchester: Oak Knoll Press, 1993), p. 82.

31 PC, 6 September 1856.

32 See also Laurel Brake, ‘The Longevity of “Ephemera”’, Media History, 18 (2012), 7–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2011.632192. For the long lives of eighteenth-century newspapers, see Uriel Heyd, Reading Newspapers: Press and Public in Eighteenth-Century Britain and America (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2012).

33 Bolton Chronicle, 30 June 1855.

34 [Wilkie Collins], ‘The Unknown Public’, Household Words, 21 August (1858), 217–22.

35 Recollections of William Abram, editor of the Blackburn Times and Preston Guardian, PG jubilee supplement, 17 February 1894, p. 12.

36 Hartley Aspden, Fifty Years a Journalist. Reflections and Recollections of an Old Clitheronian (Clitheroe: Advertiser & Times, 1930), p. 9.

37 James Ogden, ‘The Birth of the “Observer”, Rochdale Observer, 17 February 1906.

38 PC, 20 October 1877.

39 This recollection, from 1889, is by J. H. Spencer, whose collection of broadside ballads is held at Preston’s community history library: J. H. Spencer, ’A Preston Chap Book and its Printer,’ PH, 21 January 1948.

40 Thanks to Roger Neil Barton for background information on news room telegraph services.

41 Minutes of Preston Exchange & News Room committee, 24 June 1867, Lancashire Archives LRO CBP 53/4.

42 ‘Annual meeting of the subscribers to the Exchange Newsroom’, PC, 19 November 1870.

43 ‘Nothing Like Example’, All the Year Round, 30 (1868), 583–87 (p. 583).

44 ‘Travels in Search of Recreation II, Central Working Men’s Club’, PC, 20 February 1864.

45 Barrow Working Men’s Club Reading Committee minute book 1881–91, meeting of 27 July 1883, Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre, Barrow. One oral history interviewee remembered reading the News of the World in the outside toilet in the early twentieth century.

46 PH, 3 September, 1870, p. 5; the Mannex directories for Preston in 1873 and 1874 list thirty-four ‘newsagents and stationers’.

47 This was a national phenomenon: Charles Mackeson, ‘Curiosities of the Census. V.’, The Leisure Hour, 20 June 1874, 390–92 (p. 390).

48 Stephen Colclough, ‘“A Larger Outlay than Any Return”: The Library of W. H. Smith & Son, 1860–1873’, Publishing History, 54 (2003), 67–93; Guinevere L. Griest, Mudie’s Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1970), pp. 18, 39. See list of ‘second hand reviews and magazines’ from Mudie’s 1890 catalogue in Brake, ‘Trepidation’, p. 82.

49 Aspden, p. 9.

50 Gary Cross, A Quest for Time: The Reduction of Work in Britain and France, 1840–1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), p. 84; Mark Hampton, Visions of the Press in Britain, 1850–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), p. 28.

51 John K. Walton, Lancashire: A Social History, 1558–1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), p. 190; Robert Poole, Popular Leisure and the Music Hall in Nineteenth-Century Bolton (Lancaster: Centre for North-West Regional Studies, University of Lancaster, 1982); Dave Russell, Football and the English: A Social History of Association Football in England, 1863–1995 (Preston: Carnegie, 1997); John K. Walton, The English Seaside Resort: A Social History, 1750–1914 (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1983). For an explicit linking of these workers and new publishing genres, see Margaret Beetham, ‘“Oh! I Do like to Be beside the Seaside!”: Lancashire Seaside Publications’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 42 (2009), 24–36, https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0060

52 O’Neil diaries, 11 November 1856.

53 O’Neil diaries, 15 January 1860, 15 December 1872.

54 PC, 3 September 1870, p. 1.

55 PC, 22 December 1861, 5 September 1863, 1 July 1871.

56 Anthony Hewitson, Hewitson’s Guild Guide and Visitors’ Handbook: An Up-to-Date History of Preston, Its Guild, Public Buildings, Principal Objects of Interest (Hewitson, 1902), p. 36.

57 Christopher M. Baggs, ‘The Libraries of the Co-Operative Movement: A Forgotten Episode’, Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 23 (1991), 87–96 (pp. 90, 92).

58 O’Neil diaries, 28 September 1873.

59 PG, 3 August 1878, p. 10; PG, 2 January 1878, p. 6.

60 John Convey, The Harris Free Public Library and Museum, Preston 1893–1993 (Preston: Lancashire County Books, 1993), p. 20; William Bramwell, Reminiscences of a Public Librarian, a Retrospective View (Preston: Ambler, 1916).

61 Robert Snape, Leisure and the Rise of the Public Library (London: Library Association, 1995).

62 ‘Social and family life in Preston, 1890–1940’, transcripts of recorded interviews, Elizabeth Roberts archive, Lancaster University Library (hereafter ER; the letters P, B or L at the end of the interviewee’s identifier denotes whether the interviewee was from Preston, Barrow or Lancaster): Mr H6P (b. 1896). The transcripts are being digitised, with some available at www.regional-heritage-centre.org; Lancashire Catholic, August 1895, p. 163; Cross Fleury’s Journal, November 1898, p. 2.