3. Reading Times

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.03

Time is part of the very name of ‘newspaper’, with its promise of something new, and of ‘periodical’, suggesting something published at regular intervals. Time is also part of their nature, their formal qualities, with their prominent dates and numbered series, demonstrating continuity and open-endedness.1 Many theorists have sought meaning in the regularity of publication and a perceived acceleration in publishing frequency during the nineteenth century, linking these features to wider cultural changes in Victorian attitudes to time. Mark Turner boldly suggests that ‘the media […] provides the rhythm of modernity.’2 Victor Goldgel-Carballo takes the same view, quoting nineteenth-century Argentine commentators on the popularity of magazines: ’Faster times […] require faster media; and precisely because they were faster, and therefore seemed to mediate better, periodicals were considered more modern, that is, more appropriate to present times than previous media.’3

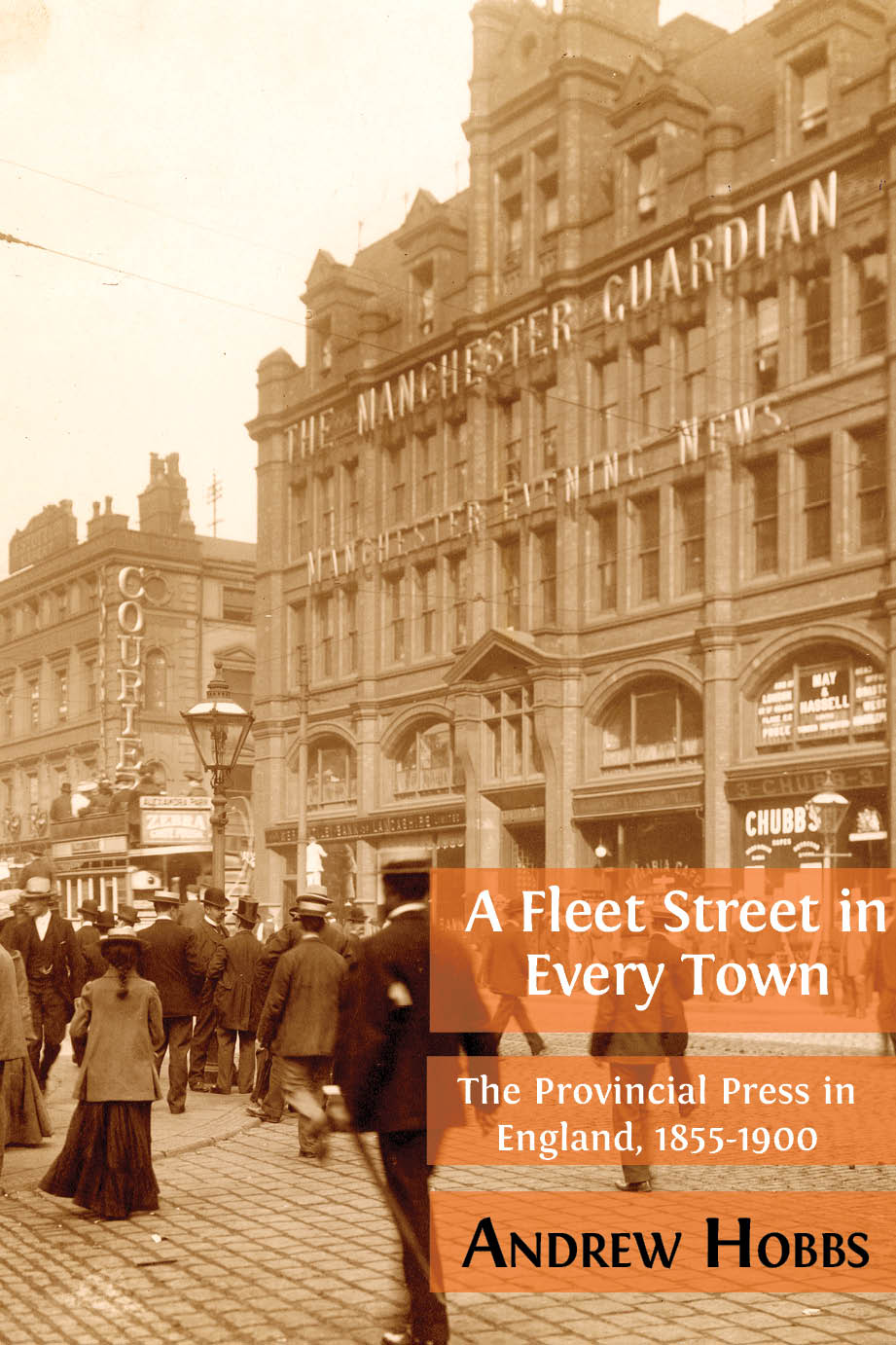

Time, like place, is socially constructed rather than ‘natural’, and so one might expect ideas of time to be influenced by cultural change.4 But the prosaic evidence of local newspaper readers through the day, the week, the month and the year challenges many of these theories, based as they are on an ahistorical, implied reader. And while the implied reader is singular, ‘historical’ readers are untidily plural, with differing attitudes and experiences of time, confirming that ‘it makes sense to speak not of a culture’s “time” but only of its several “times”, precisely distinguished and carefully related, in their conflicts, their alignments, their convergences’.5 While some readers did measure out their days and weeks in newspapers, the rhythms of their reading were often out of sync with the rhythms of publishing. And while the ‘progress and pause’ of Hughes and Lund’s serials may fit a publishing schedule, reading schedules were often irregular: newspapers and magazines remained on the reading room tables to be read until the next issue arrived, up to a month later; and exhausted mill workers are unlikely to have experienced the sixty-hour working week between serial instalments as a ‘pause’.6 Weekly publishing schedules (the most common frequency) were not new, they were simply overlaid onto older rhythms of local market days and religious observance. Beyond pleasing symbolism, there may (or may not) be a correlation between change brought by industrial time-keeping and railway time on the one hand, and periodical time on the other. But correlation does not imply causation. Indeed, what would even count as evidence for one influencing the other? As Margaret Beetham notes, ‘it is impossible to separate out the periodical from other structures in advanced industrial societies by which work and leisure have come to be regulated in time.’7

There is a disconnect between the linear, historical time of newspaper content, with its claims of advance, progression and change, and the cyclical, repetitive habits of historical newspaper readers, as they fitted these publications into their routines and rituals, domestic and public. This was a negotiation between the rigid times of publication and the more complex, messy times of access, leisure and sociability which enabled reading for the vast majority.

If time is socially constructed, periodical time is even more artificial, almost fictional. Publishers planned in advance a constructed ‘now’, a present, that lasted until the next issue, while the date at the top of the newspaper, ‘the single most important emblem on it’ according to Benedict Anderson, was rarely the date on which it was published.8 Morning newspapers were printed the night before, as were most weekly papers. Most editions of newspapers with ‘evening’ in their titles were published in the morning or afternoon. Bauman argues that time and space became separated in the modern era, but newspaper and periodical publishers united them in their fictional cover dates, which disguised the series of deadlines for multiple editions and the varying distances that these physical objects travelled from the printshop to the reader.9

James Mussell gives the example of the Northern Star, which carried Saturday’s date on its front page, but some editions — those that had to travel the furthest from its place of publication, Leeds — were printed on a Thursday. Many readers across the country may have read copies of the paper, all labelled with the same day and date, simultaneously on a Saturday morning, but they were reading a variety of editions, each differing slightly in its content. And these were only the first readers of each copy. The majority of Northern Star readers probably read their copy on other days, as each copy was passed along a chain of readers. Equally, the morning papers of Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Birmingham and London reached readers at different times. So, while Anderson’s idea of print creating imagined communities is useful, the element of synchronicity or simultaneity is also imagined.

Nineteenth-century publishers were more open about the conventions of publishing, reminding contributors of press times in their ‘Notices to Correspondents’ sections, or explaining that they were reprinting material omitted in some editions of the previous issue, but included in others.10 Readers were aware of this — Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil noted in his diary that 4 June 1856 was ‘the day that Palmer was hanged. I have seen the fourth edition of the Manchester Times and Examiner which gives a full account of his execution at 8 o’clock this morning […]’ Readers were also aware of the distance between place of publication and place of reading, if this was not in the same town or city. This was the distance between core and periphery, a measure of the reader’s distance from the centre of cultural power.11 For the majority of magazines and a minority of newspapers, that centre was London, and one can only imagine the feelings of a reader in Preston waiting until lunchtime for a copy of the Times to arrive at the reading room, only to find that its contents reflected little about the reader’s life in Preston. The local press challenged these relations of core and periphery, creating a network of widely distributed small centres of local cultural power, thereby subverting London’s status as a centre, and positioning the capital as peripheral to life in the provinces.

This chapter is neatly divided into days, weeks, months and so on, but publishers sometimes stretched or blurred these categories. The bi-weekly Preston Herald pointed out that, on its two publishing days, it provided more up-to-date news than daily papers. But it was readers who were most likely to ignore the publishing calendar and clock. They fitted newspaper reading into their lives less tidily, regardless of the date on the front page or the frequency of publication. They read Saturday papers on Sundays, and weekly papers every day, such as readers of the Preston Guardian in the 1840s ‘who were ready to pay 4½d or 3½d for their weekly journal, and who, bent on getting their money’s worth out of it, read it in leisure minutes through the ensuing week.’12 Equally, some readers’ weekly reading was a daily, such as the Manchester Guardian, whose biggest sale in the 1850s and 1860s was on Saturday.13 These practices were probably dictated by lack of leisure time, or lack of money. Reading rhythms were influenced, but not determined, by publishing rhythms. The next sections explore these reading rhythms, in Preston and other places, working from days through to the seasons of the year, and less regular rhythms dictated by unexpected events.

The Day

Reading did not occur uniformly around the clock in Preston, as elsewhere. There were clear reading rhythms to the day, starting at dawn with the arrival at the railway station of the morning papers from Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham and Leeds (creations of the 1855 Stamp Duty changes), and the first editions of Preston’s papers on Saturdays and Wednesdays, all soon to be read at middle-class breakfast tables. The commercial and middle-class reading rooms opened between 8am and 9am ‘so that persons on their way to business can see the morning papers.’14 Other reading places such as the YMCA in Fishergate (8am-10.30pm), Cowper’s Penny News and Reading Room in Cannon Street (9am-10pm) and from 1879 the free library (9am-10pm) opened at similar times. The London and Scottish papers arrived before lunch, and on Wednesdays and Saturdays the last editions of the Preston papers came off the presses around midday.15 In some workplaces, including those mills which provided libraries, lunchtime would be a chance to read.

By the end of the 1860s, late afternoon would see the arrival of evening papers from London such as the Standard and the Echo, and from Manchester, Liverpool, Bolton and other Lancashire towns.16 Preston had its own evening paper during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and continuously from 1886, with many copies sold outside factory gates as the hooters sounded at the end of the working day. They were probably scanned on the way home, and local autobiographies and oral history interviews record how in working-class and middle-class homes the man of the house (less often the woman) would relax in the evening by reading the paper. The local evening paper was part of a routine of leisure, particularly for men, but also for women:

Bert’s slippers were warming by the fire. And by his chair were his packet of Woodbines, matches and the Evening Gazette […] After his tea he would make himself comfortable in his own reserved chair and read the newspaper while puffing on his Woodbine.17

My grandmother […] had a double-jointed gas pipe near so that she could pull the gas flame near to her Lancashire Daily Post in an evening.18

The same ritual was enacted in middle-class Preston homes, too, as described in this recollection of Dr Arthur Ernest Rayner from the early twentieth century, by his daughter:

[…] in front of the fire he would light his beloved cigar — Ramon Allone Corona — unfold the Lancashire Daily Post, and undo a waistcoat button. At last he was relaxed and we could breathe.19

‘I should say nearly every home took the [Lancashire Evening] Post’, one interviewee said of Preston in the early decades of the twentieth century.20 Whether they did or not, this reader imagined that they did — confirming Benedict Anderson’s theory that an integral part of the private ritual of reading the local paper is the belief that thousands of others are performing the same act or ‘ceremony’ — thereby connecting them, in their imagination, to other readers.21 However, contrary to Anderson and Hegel before him, simultaneity is not essential; indeed, the sense of simultaneity is often a fiction, evoked by the ‘nowness’, the sense of the present, in the selection and tone of address of the publication.22 Others may read the paper at a different time of day, or even a different day of the week, but a sense of community comes from the belief that others are reading the same newspaper, issue by issue, for similar purposes, in other parts of the paper’s sphere of influence, its circulation area. As we shall see, readers are also subjects of the local paper, actors in the continuous, continuing story of one place through time. Hegel and Anderson liken newspaper-reading to a religious ritual; here also, communities created by shared religious rituals do not require simultaneity, only similar practices for similar purposes.

As the working day ended, reading rooms for working men in church and school premises began to open in the early evening, and those that opened all day were at their busiest, while newsagents’ shops were closing by 8pm, although reading matter could still be obtained at later hours in the smaller grocers’ shops in the back streets. Between 9pm and 10pm the reading rooms in the town centre and on the outskirts of Preston closed their doors (except the Winckley Club, which stayed open until 11pm, possibly later), and the only remaining reading places would be homes and pubs.

The Week

The week was probably the most important newspaper-reading rhythm for most of the Victorian period, as weeklies outnumbered dailies significantly, even at the end of the century (see Introduction, Table 0.1). The local press in particular was part of the furniture of private and domestic life.23 Reading the local paper was a ritual, woven into weekly routines, as seen in this effusive (and suspiciously well-written) letter in a Preston paper of 1852:

I am an old man; and having, for […] thirty years, been a devoted reader of the Preston Chronicle, that newspaper has become, as it were, a part and parcel of my very existence. I could as soon think of leaving Preston on the market-day minus my favourite old mare […] as to leave the town without taking home with me a Chronicle […] When the toils of the day are completed, and our substantial evening meal has been partaken of, it would gladden your heart to see how anxiously my family assemble, with eager ears, to listen to the events recorded in your columns.24

Whether this letter is genuine or not, such an attitude would have been credible to readers, as such habits are recorded in more reliable sources. Similar self-awareness by a purported reader about their ritual use of newspapers is seen in the ‘old servant who has called “faar the news” at the market town once a week these fifty years, and the old master who has taken it in all his life, [who] speak of their constancy with a sort of pride.’25

The reading week had its rhythms, with long working hours limiting leisure time, including reading time, to the weekend for many people: textile workers gained the Saturday half-holiday from the 1860s onwards, so weaver John O’Neil read on Saturday afternoons, but mainly on Sundays.26 For workers like O’Neil, reading was the chosen way to mark a pause in the work week.27 Most of Preston’s weekly and bi-weekly papers published on a Saturday, the main market day, with mid-week editions appearing on the second market day, Wednesday. This integration into the ancient routines of the local economy highlights the newspaper’s economic role. The increasingly popular regional weekend news miscellanies such as the Liverpool Weekly Post and the Manchester Weekly Times, appearing from the late 1850s onwards, published on Fridays and Saturdays, ready for weekend reading.28 Nationally, popular London Sunday newspapers had the highest circulations of any individual title throughout the period, yet they are rarely mentioned in the Preston sources until the end of the century, suggesting that their circulation may have been regionally concentrated, selling less in the North West; instead, local and regional weeklies are mentioned more frequently. In the early twentieth century, a Preston man made a Manchester Sunday paper part of his weekend routine while his children were at Sunday School:

The absence of the children on Sunday afternoons gave an opportunity to father to have his weekly fireside bath and afterwards to relax in an armchair contentedly reading his favourite newspaper, the Sunday Chronicle [1885–1955].29

Such Sunday leisure was enjoyed less often by women, particularly those Preston wives and mothers who worked in the cotton mills, who had to cram much of the housework into the weekend. In St Helens, too, ‘Saturday is not the women’s reading day, and Sunday is their chiefest day of toil’.30 In contrast, in Barrow, where fewer women worked, one mother set aside Sunday afternoons for reading:

The only time my mother used to read was Sunday afternoon. She was always working, looking after the family, but Sundays, no work on Sundays, nothing had to be done. After Sunday dinner mother used to get those little books like Home Chat [1895–1959] and she’d read those and St Mark’s church magazine.31

Men generally had more time, as well as more places, to read; in Middlesbrough, Bell’s survey of working-class households notes many instances where ’wife no time for reading’:32 Few women would have been able to devote as much time to reading the paper as the Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil, a widower living with his daughter, who would sometimes spend the whole of Sunday reading a newspaper from his home town of Carlisle.

The publication day of a favourite magazine was a special event for some readers and listeners:

My father used to read to [my mother], the newspaper, and he would read bits out of the newspaper and he used to read her the John Bull [1906–60] every Thursday, that was her highlight.33

Thus the different reading times of the Barrow woman on a Sunday afternoon, and the Preston woman listening to John Bull on a Thursday, were dictated by the publication days of their favourite periodicals, but also by the availability of leisure time.

Sunday newspaper reading was even found in the Preston workhouse, as reported by one of the Poor Law Guardians, William Howitt, a surgeon, who disapproved of this replacement of an older spiritual routine by a newer secular one:

on Sunday morning last […] instead of finding service being conducted there, as he expected, he found the men sitting reading the papers, spitting about the floor, and indulging in ribald and indecent talk. The women were also engaged in reading the papers.34

The papers in question were the Preston ones. ‘Many persons believe it to be wrong to read newspapers and secular books on Sundays,’ as one correspondent to the Preston Chronicle wrote in 1857.35 The letter, from ‘A Member of a Mechanics’ Institute’, supported the Sunday closure of Preston’s institute; many of the town’s other public reading places were also closed on Sundays, the chief exceptions being the pubs and the Winckley Club (of which Mr Howitt was a member), demonstrating how middle class readers had a greater choice of reading times than working-class readers; perhaps Mr Howitt believed that the middle classes were more resistant to possible harm from Sunday newspaper reading than the working classes. Clergymen such as Francis Orpen Morris, rector of Nunburnholme in Yorkshire, also complained that the weekend papers kept people away from church: ‘the second-rate country penny press […] many of them being published on a Saturday […] furnish an attraction to the labouring men to keep them at home on a Sunday.’36

Oddly, monthly reading rhythms rarely appear in the Preston evidence. ‘Magazine day’ — variously dated to the last day of the month for publishers, the first day of the month for readers — was important to London periodical publishers and wholesalers, and to readers in Preston.37 Monthlies were the most popular type of publication available in the reading rooms of the public library in 1880 (47 per cent of the 94 titles taken), but by 1900 they had been overtaken by weeklies (43 per cent of the 190 titles taken). The month was a metropolitan but not a local publishing rhythm, perhaps because of smaller local markets, most of them unable to sustain monthlies.

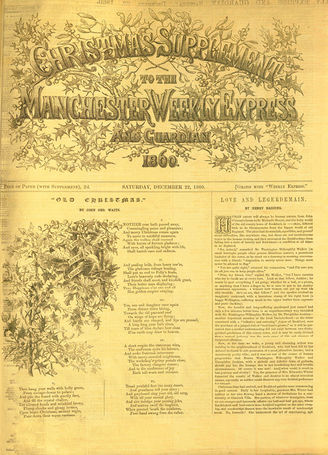

Fig. 3.1. Front page of Christmas supplement, Manchester Weekly Express,

22 December 1860. Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council, all rights reserved.

The Season and the Year

Reading had its seasons. Christmas annuals and supplements of monthly and weekly magazines (and magazine-newspapers such as the Manchester Weekly Express, Fig. 3.1, previous page) ‘bulging with verse, stories and pictures’, were popular then as now, such as Owd Wisdom’s Lankishire Awmenack for th’ yer 1860, bein leop yer, a dialect almanac published from Bolton but apparently printed and/or sold in many other Lancashire towns, including Preston.38 Newspapers and magazines co-opted the ancient and popular time-focused print medium of the almanac, with the local press supplementing the circular time of prophecy and fulfilment, agricultural seasons, fairs and tides, with anniversaries of local notables and events, to create a linear continuity between past, present and future in one place.39

For other readers, seasonal holidays were an opportunity for more leisure, including reading. On Christmas Day 1877 the Winckley Club in Preston was open for business as usual, and in 1909–10 the Barrow public library was open on Christmas Day, Good Friday and Easter Monday.40 Generally, newspaper sales fell in the summer, one reason given for the closure of the Preston Evening News in June 1871: ‘Summer is upon us, when the proper out-door recreations of the season greatly modify the appetite for newspaper reading.’41 Thirty-five years later James Haslam found the same seasonal decline in Manchester, noting how, ‘in summer, the reading of newspapers and periodicals falls off. People go in for other things; they spend their money on holidays, on picnics and out-door life. The finer the weather, the less reading.’ He quotes a Harpurhey newsagent explaining the best type of weather for newspaper sales: ‘I like […] a wet Set’dy afternoon an’ neet. There’s a big rush for pappers then; I allus sell up!’42 Conversely, some publications were designed specifically for summer reading, such as Bright’s Intelligencer, the Southport Visiter, the Morecambe Visitor and other visitors’ lists (directories of holidaymakers combined with local news and advertising, many of which became year-round local papers). They increased their publishing frequency during summer, appearing weekly during the tourist season and monthly the rest of the year.43 Similarly, seaside and holiday annuals with a distinctive Lancashire flavour such as Ben Brierley’s Seaside Annual (extant 1878) were popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.44 This seasonally adapted reading matter was waiting for the reader when they arrived at their holiday destination. These changes in place and frequency of publication are an example of the negotiation between demand and supply, publisher and reader.

These rhythms of reading — daily, weekly, monthly and seasonal — are examples of what Kristeva calls ‘circular time’.45 As we will see in Chapter 10, this is the dominant experience of time connected with reading the local paper, with its associations of ritual and reassurance. J. F. Nisbet noted this repetition in 1896:

The great fault of the daily paper, however, is not so much its quantity of news as the essential sameness of its news from day to day. This, most people notice with regard to political speeches and leading articles on “the situation”; but is it not also true in relation to murders, divorces, breach of promise cases, suicides, swindles, robberies?46

But there is another type of reading time, a linear pattern, in which the uniqueness of now is foregrounded, a present that is different from the past behind the reader and the future before them.47 As Beetham notes, newspapers and magazines are read in both types of time; genres — of crime, spendthrift councillors or football results — are cyclical and repetitive, while their specific instances, issue by issue, are new and unique, part of linear time.48 The experience of reading time differs according to the purpose of reading, so a reader looking for confirmation of their world-view experiences time in a ritual, repetitive way, while a businessman needing to know today’s cotton prices in Manchester seeks new information in a linear way. In the next section, we see how readers experienced unexpected, exciting and frightening news, which disturbed cosy rituals and highlighted the uniqueness of the present and the uncertainty of the future.

Leisure for reading was sometimes unexpected and unwelcome, during trade slumps, strikes and lock-outs. During the Preston lock-out of 1853–54, enforced leisure increased reading, of books at least. Preston prison chaplain and social investigator Rev John Clay noted how

the sale of the penny publications has scarcely diminished, though the demand for higher priced works has. The pawnbrokers, also, tell me of a fact, which points to the inference, that reading is becoming necessary to the working-man — viz., that the number of books in pawn is now very much less than it was during the time of full employment.49

In Barrow, the public library was busier during trade depressions; after one such slump ended, the librarian’s annual report for 1889–90 records that

the daily average number of books lent out from the Library is less than during the period covered by the last Report. This may be attributed, and the reason is a very satisfactory one, to the great improvement that has taken place in the trade of the town during the last year, thus affording less leisure for reading.50

In Preston, too, there was an ebb and flow of ephemeral public reading places, organised by trade unions, churches and middle-class benefactors in response to similar crises. In 1862, during the 1861–65 Cotton Famine, the Preston Chronicle reported that ‘The READING ROOM, established a few weeks ago in the Temperance hall, North-road, is well frequented. A good fire is constantly kept, and all unemployed operatives are welcomed.’ A year later the Mechanics’ and Engineers’ Society of Preston started a reading room and school for unemployed members.51

Newsy Times

Wars, elections and other newsworthy events created less regular or predictable times when reading, particularly reading of news, became more important. Preston’s Central Working Men’s Club found its news room ‘frequently crowded, especially during the meeting of Parliament, and when other questions of national interest are pending’ while Preston Chronicle editor Anthony Hewitson noted in 1872 ‘a great run on London papers; yesterday being National Thanksgiving Day for recovery of Prince of Wales.’52 Such stories, along with election or sporting results, attracted crowds to the newspaper offices, to read the telegrams and posters stuck on the windows or shutters, and to buy ad hoc supplements with verbatim reports of election speeches or special editions, the Victorian version of ‘rolling news’.53 Publishers also changed the frequency of papers to meet demand at happier times, such as the 1882 Preston Guild, the town’s once-in-twenty-years civic festival, when for example the usually bi-weekly Preston Herald switched to daily publication during the Guild fortnight, with press times linked to train times in order to speed distribution. We have already seen how newspaper readers met in the pub on Sunday nights during the exciting 1830 Preston election. Publishers were good at adapting, at fitting messy, unpredictable events into the industrial processes and rhythms of printing and distribution. We can distinguish between reading and publishing rhythms, but at these newsy times they were particularly closely related through supply and demand (as during seasonal changes).

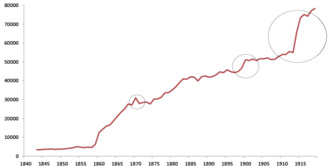

War has always been good for the news trade. Wars prompted the creation of reading institutions, such as the Lord Street Working Men’s Reading Room in Carlisle, which began when fifty men, ‘anxious to read about the European revolutions of 1848, clubbed together to buy newspapers’. A few years later the Crimean War motivated Hebden Bridge men to join a society in order to read the papers.54 The Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil counted the days until he could hear more news of the Indian Mutiny in 1857, writing of how he ‘heard today that Delhi has been taken but I could learn no particulars, so I must wait until Saturday when I will see the newspaper.’55 He was gripped by reports of the battle that ended the second War of Italian Independence in 1859; on 2 July he ‘got a newspaper and read the full account of the great battle of Solferino, fought on the 24th of June.’ The next day, he wrote ‘[…] I have never been out of the house. I have been reading nearly all day different accounts of the great battle of Solferino.’56 Publishers large and small responded to this intense, avid reading of war news, such as the unemployed London compositor, who compiled telegrams of the Ethiopian revolt and sold 10,000 copies of his ‘Abyssinian Gazette Extraordinary, at a profit to him, personally, of not less than £12’.57 The circulation graph of the Glasgow Herald (Fig. 3.2) shows ‘curious little spurts’ in 1870, 1900 and 1914: ‘There seems to be nothing like a war to improve the circulation position of the more expensive papers’, as a later Herald editor noted.58

Fig. 3.2. Glasgow Herald sales, 1843–1919, showing rises during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), the Boer War (1899–1902) and the First World War (1914–18). Author’s graph, CC BY 4.0.

There is a very small peak in 1855 during the Crimean War, but the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 was the first ‘European war on a grand scale since the recent development of the cheap press and telegraphy,’ as the Printers’ Register noted, stimulating accelerated demand for war news among the mainly middle-class buyers of morning newspapers:

Families which would a few years back expend a shilling in the course of a week will now spend three; and men who were content with their favourite morning paper formerly, must now indulge themselves with an evening paper as well, and occasionally with a second or third edition.59

A week later another trade paper reported that ‘the war has been the means of increasing the sale of newspapers immensely, both London and Provincial.’60 In Preston, too, the demand for news had an impact. The Preston Guardian boasted how ‘a large crowd gathered on our special edition being published’ to report the surrender of Emperor Napoleon III, causing ‘great excitement in Preston’.61 In 1870–71, the Winckley Club spent forty per cent more on newspapers, periodicals and stationery (from £53 8s 1½d to £74 4s 6d) than the year before. The minutes offer no explanation, but it is likely that the increase was due to the purchase of more titles and more editions to meet demand for war news. Even second-hand newspapers were in greater demand in 1870 — at the club’s annual auction of second-hand papers and magazines that year, the resale value of newspapers such as the Preston Chronicle, Liverpool Mercury and Manchester Guardian rose, while those for magazines fell. Similarly, readers’ scrapbooks show traces of a more intense connection to newspapers in wartime; Ellen Gruber Garvey argues that while some people kept up scrapbooks throughout their lives, others returned to them ‘on occasions — such as war — that heightened their relationship to the newspaper’.62

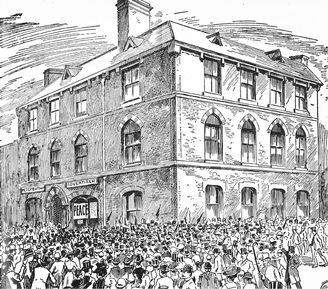

War led to ad hoc changes in publishing and reading, which often had long-term effects. Formal outdoor newspaper reading was sometimes arranged at such times. In Hanley in north Staffordshire, during the Crimean War, the editor of the Staffordshire Sentinel and commercial traveller Samuel Taylor would read war reports from the Times in the market square, ‘people flocking to the square in great numbers on the evenings when the readings took place.’63 Demand for war news prompted the launch of three short-lived daily papers in Preston, and in 1871 the Conservative weekly the Preston Herald claimed that its circulation had ‘more than trebled during the past twelve months’, no doubt due to interest in war news. Pubs used war news to attract customers; an 1870 advert in the Preston Chronicle informed readers that ‘the latest news from the seat of the war can be read at Barry’s Hoop and Crown, Friargate’, while the Cheetham’s Arms, London Road, used the heading ‘War News’ to trick readers into looking at their advert in the same issue.64 During the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), newspapers (from Manchester and London) were mentioned more frequently in the postcard correspondence of the Vicar of Wrightington, Rev John Thomas Wilson.65 The Boer War had the same effect (Fig. 3.3), boosting circulations of the Lancashire Evening Post and other provincial and London papers, particularly when news came through of events such as the Jameson raid (1895–96) or the relief of Mafeking (1900).66 Just as the Crimean War created a demand for news among Carlisle working men, so the Franco-Prussian War and Boer War did the same in Preston and elsewhere, causing long-lasting changes in reading habits and therefore in publishing habits. The first two of these three wars helped to popularise new genres such as the provincial morning and evening paper (see Chapter 6 for details).

Fig. 3.3. Crowds gather outside the Peterborough Advertiser office at the end of the Boer War (the Second South African War), 1902. Courtesy of

Peterborough Telegraph, CC BY.

If we imagine a continuum of reading times with circular/ritual at one end and linear/information-receiving at the other, then unexpected news events such as wars suspend normal rituals and move people’s reading behaviour along the continuum towards a demand for new information, an orientation to linear time. A feeling of suspense is created, as readers wait for new developments. ‘News stands on the cusp between past and future; it arouses recollection, anticipation, expectation, or apprehension.’67

Some editors recognised, and manipulated, the attractions of suspense and anticipation borrowed from serial fiction. As early as the 1830s, James Gordon Bennett eked out the details of a murder case day by day, greatly increasing the sales of his New York Herald.68 On Wednesday 19 November 1856 O’Neil wrote of the suspense of waiting for the resolution of a running story: ‘I can hear no news from the United States yet concerning the Presidential election.’ He had to wait three days to hear that President Buchanan had been elected. Preston solicitor William Gilbertson was anxious to see the London papers as soon as they arrived before lunch at the Winckley Club, complaining three times in the suggestion and complaint book about their late arrival in 1877.69 O’Neil often looked forward to further news of a continuing story, even predicting the days on which news would arrive by mail boat. On Saturday 12 September 1857 he summarised in his diary the latest news from India, adding ‘the next mail will not be here before Monday, so next week we will be having some news.’ Three months later, he noted that ‘the newspaper […] is full of the dispatches from India confirming all that had come by telegraph […]’.70 This knowledgeable newspaper-reader could differentiate between fast but brief telegraphed news and slower, more detailed reports arriving by mail boat, the first creating suspense in this case, the second closure and resolution of the story. Anticipation, of course, was also part of the ritual use of the local newspaper. In Wigton, Cumberland, an eight-year-old J. W. Robertson Scott would stay at home after school every Friday, waiting for his local paper to be delivered.71

Short, Medium- and Long-Term Newspaper Lives

News, a report of what’s new, is by definition ephemeral. Yet the long lives of some yellowing, crumbly papers complicate our ideas of news as here today, gone tomorrow. Three objects demonstrate this complexity: the pieces of torn newspaper hanging on a nail in an outside toilet; a bound volume of newspapers; and the rolled up copy of a newspaper in a time capsule buried beneath the foundation stones of a Victorian gas company office. These objects symbolise Uriel Heyd’s three types of newspaper-reading time, short-, medium- and long-term.72 News is indeed ephemeral, and during wartime or other newsy periods, only the freshest news had any value. In 1860, Manchester barber and part-time racing writer Richard Wright Procter described how ‘news grows old in a few hours. Editions chase each other through the day like Indian runners, each one bearing a telegram. Consequently, many persons have become so finical in their purchases, that when the sixth edition is offered to them they decline to take it; it has been stale, they say, several minutes; they must have the impression just issued, or none.’73 For most readers, a newspaper or magazine ‘becomes obsolete as soon as the next one comes out’.74 Of course, what is presented as news is not always new.

The torn pages of a newspaper used as toilet paper symbolise the worthlessness of old news and represent the majority of the copies printed. The material qualities of the paper become more valuable than what’s printed on it.75 However, some copies survived in the medium term — sold second-hand or bound into volumes for reference. These bound copies were kept, and heavily used, in reading rooms, news rooms, libraries and newspaper offices.76 Publishers encouraged this, and happily bound back copies into volumes. In the 1750s, Boddely’s Bath Journal was numbered by volumes, and its bound volumes had ornate title pages printed in red, featuring the Bath city coat of arms.77 At the Liverpool Lyceum, a third of the newspapers taken in the 1850s (thirty-two of ninety-three) were filed for reference (eleven Liverpool papers, eleven other provincial papers and ten London papers).78 As late as 1920, a library management manual recommended keeping ‘Permanent files of at least The Times, and all local newspapers; and temporary files of other newspapers most in demand.’79 This demand for filed back copies of local papers needed to be emphasised in newspaper reports, to explain their absence from auctions in news rooms, in case anyone should think that the title in question was either not supplied there, or failed to sell in the auction.80

While publishers could make a few shillings from binding back copies, ephemerality — the appearance of built-in obsolescence — was more profitable in persuading readers to buy the next issue. Like the date on the cover, it is another fiction, something constructed to sell papers. As Michael Thompson argues in Rubbish Theory, ephemerality or transience is rarely ‘natural’, instead it is socially constructed in the interests of those with economic power.81 When readers refuse to treat newspapers as ephemeral, saving them, collecting them and re-reading them, their timescales diverge from publishers’ industrial timescales.

David and Deirdre Stam have explored a fascinating example of this medium-term reading time of newspapers and periodicals, by polar explorers such as W. Parker Snow, clerk on the Prince Albert, who went in search of Franklin’s party in 1851 and wrote of how ‘I have often, myself, when at sea, felt the greatest delight from perusing a journal, however old it might be’. Here, the freshness of the news is not important. Or French explorer Jean Charcot, on the Pourquoi Pas? from 1908 to 1910, putting out copies of Le Matin and Le Figaro each day, exactly two years after their cover date: ’I await the next day’s issue with impatience’, he wrote, although he had read them on the day they first came out. Freshness is in the eye of the beholder, according to Roald Amundsen, another explorer, who met a ship in 1908 carrying old newspapers: ‘Old! Yes to you! To us, they were absolutely fresh!’82 The age of the news was equally irrelevant to John O’Neil when he received copies of the local paper from his home town of Carlisle.

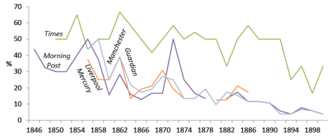

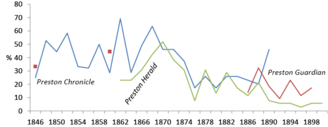

The continuing but changeable value of old news can be seen in the practice of auctioning second-hand newspapers and magazines to members of news rooms (and to the general public). However, the relative values of different newspaper and magazine genres are impossible to interpret without knowing why each individual bought each individual title. The peaks and troughs of the graphs in Figs. 3.4 to 3.6, summarising auction prices at Preston’s Winckley Club, reflect a title’s value on a particular day among a particular group of men, and as with any auction, two keen bidders can distort the price; overall trends are more reliable.83 At a more general level, there were big differences in the second-hand value of different genres and individual titles. The most valuable were Punch and the Illustrated London News, then the Times, the Quarterly Review, Temple Bar, then local weekly and bi-weekly newspapers, then at the bottom, morning daily newspapers (apart from the Times), with similar values for London and provincial big-city papers.

Second-hand, Punch was worth around seventy per cent of its cover price from the 1860s onwards, the Illustrated London News (ILN) slightly less at around sixty per cent. The Times sold for around fifty per cent of its cover price until the 1890s, significantly higher than the second-hand values of other dailies, London or provincial. Next in value were the serious literary and political Quarterly Review (around forty per cent until the 1880s, when there was a steep decline, after which it was no longer bought by the club), and Temple Bar, a shilling fiction monthly, also selling for around forty per cent of its cover price. Then the Preston papers, selling at between thirty and fifty per cent of cover price from the 1840s to the 1870s, followed by a steep decline. The Preston Guardian, the biggest-selling Preston paper, was often missing from the auctions, because it was bound and filed for reference, along with the Times and the Manchester Guardian, as a paper of record. The least valuable titles were the morning papers; the Morning Post fell in value from the 1860s onwards, and was worth only ten per cent of its original value in the 1880s and 1890s. Similarly, the Manchester Guardian and Liverpool Mercury, which both sold across the whole of North West England, declined steadily from forty to fifty per cent of cover price to less than ten per cent. The declining values mirror the growth of the periodical and newspaper market, as seen in the rise of the newsagent.

Fig. 3.4. Second-hand values (% of cover price) at Winckley Club, Preston 1846–1900: Morning newspapers. Author’s graph, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 3.5. Second-hand values (% of cover price) at Winckley Club, Preston, 1846–1900: Local weekly/bi-weekly newspapers. Author’s graph, CC BY 4.0.84

Fig. 3.6. Second-hand values (% of cover price) at Winckley Club, Preston, 1846–1900: Punch, Illustrated London News. Author’s graph, CC BY 4.0.

There are likely to be many factors influencing the second-hand value of a publication, such as its ‘re-readability’ and its availability elsewhere in Preston.85 The Times, for example, sold far fewer copies in Preston than regional or local papers. From other sources we know that circulation figures for newspapers rose throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, so it seems likely that the increased affordability of papers depressed their second-hand value, as more people could afford to buy them new.86 A fall in the cover price of a publication generally led to a depreciation in second-hand value, as with most newspapers between 1851 and 1856. While the trends in these auction records are suggestive, the bare names, titles and figures allow too many interpretations, divorced from the commentary and banter that no doubt was part of the annual sale. Crucially, while figures are safer at aggregate level, for any particular title there are at least two opposing explanations for a low resale value — either that it was so popular that most people preferred to buy it new, or that it was so unpopular that it was unwanted both new and second-hand.

Heyd’s third category of newspaper-reading time, the long term, is symbolised by the copy of the local paper in a time capsule, intended to survive and fulfil its function a century or more after it was buried. For example, copies of Preston’s three weekly papers, plus the latest edition of the Times, were placed in a bottle with some coins, inside the foundation stone of the new gas offices in Fishergate, Preston in 1872.87 Members of St Jude’s Anglican church followed the same custom when they laid the foundation stone of their church extension in 1890. Under the stone, in a bottle, they buried ‘the Preston papers’ and the parish magazine, among other commemorative items.88 In Kendal, copies of the town’s two papers, the Kendal Mercury and the Westmorland Gazette, were placed in a bottle, along with some coins and a commemorative document, in the hollow of a foundation stone below a new market hall in 1855 (Fig. 3.7 opposite).89 These buried newspapers were simultaneously ephemeral and permanent, valuable because they were of their time, yet intended to survive far beyond that time. In Thompson’s terms, most copies of a newspaper went from low-value to no value, treated as rubbish within a few days of being printed. However, those that survived eventually increased in value with time, as a look at the prices of Victorian newspapers on eBay can confirm.90 Putting them in a bottle and ceremonially burying them guaranteed that they would go from low value to high value, without passing through the ‘rubbish’ phase.

Individual elements of the newspaper sometimes had long lives, for example when pasted into a scrapbook, even if the rest of the issue was discarded. Garvey has established the depth of scrapbooks as sources for the history of reading. So many people defied the supposed ephemerality of newspapers that stationers mass-produced scrapbooks for just this purpose (Fig. 3.7). Among other insights, Garvey uses scrapbooks to reveal how certain items were read:

Saving clippings overcame the daily press’s ephemerality and disposability with a claim that newspaper items might be worth the kind of intensive reading associated with the Bible. The iconic, intensively read newspaper item is the single clipping of advice or poetry treasured in a wallet; its worn and tattered state inspires readers to beg editors to reprint the item.91

Fig. 3.7. A Victorian time capsule containing Kendal local newspapers, buried in 1855 under the ‘new market house’ and rediscovered in 1909 during the demolition of what had become the ‘old Market Hall’, now in Kendal Museum. Author’s photo, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 3.8. Cover of Victorian scrapbook. Author’s copy, CC BY 4.0.

Newspaper items were preserved in other ways, besides being cut out and glued into scrapbooks. Local newspaper poetry, seen as throwaway, was sometimes collected and immortalised in group anthologies, such as Newcastle’s Songs of the Bards of the Tyne (1849) or Manchester’s The Festive Wreath (1842). Poems were sometimes collected and republished in volume form by the newspapers themselves, as with The Poetry and Varieties of Berrow’s Worcester Journal for the Year 1828. However, such anthologies were less common in Britain than in the United States. These volumes challenge the alleged ephemerality of newspaper poetry, and exemplify how newspapers were part of the ecology of publishing; many Victorian volumes of prose also first appeared as newspaper series.

Changing Times

Enlarging our focus to cover the whole period, the times of newspaper-reading changed significantly. In larger towns and cities, daily local news became available from 1855 onwards thanks to new regional daily papers; in outlying towns such as Preston, these papers brought regional news from Manchester, Liverpool and Bolton. Daily local news appeared briefly in Preston in 1870–71, and continuously from 1886, when the Lancashire Evening Post was launched. Wiener argues that accelerating speed was the defining characteristic of the nineteenth-century newspaper press, and this ‘discourse of speed’ may have been ‘the main measure of competitive success in the news industry’, but this applies only to sudden, unexpected events, which make up the minority of content in any newspaper, particularly a local paper.92 In peacetime at least, readers seemed prepared to wait for news. Even O’Neil the news addict was usually content to wait a few days, as on May 28 1856, when he wrote, ‘[…] we got word this morning that Palmer was found guilty for the murder of John Parsons Cooke, but I will have all the news on Saturday.’

This Preston case study foregrounds other changes more significant than speed, such as the move from public to domestic reading, from listening to reading, and (for the working-class majority) from the sense of eavesdropping on middle-class news to being addressed directly by more populist publications. As this last point suggests, change happened at different speeds in different reading places frequented by different classes. The value of second-hand reading matter fell by a half between the 1850s and 1900 at the upper-class Winckley Club, suggesting that new copies of the publications, for reading at home, were now more affordable or desirable for these gentlemen. However in a different reading community, at Preston’s Central Working Men’s Club, newspapers maintained their second-hand value of around a quarter of their face value for longer, presumably because members were less able to afford to buy new.93

Times of reading shifted and expanded. For most working people, newspapers were read or heard mainly on Sundays at the start of the period, but the Saturday half-day offered more reading time earlier in the weekend.94 Morning and evening newspapers were fitted into new public and (increasingly) domestic rituals. Reading times became more plentiful and as each family began to buy their own paper, reading became more relaxed and less pressured by the demands of other readers. When one news room closed, among the items for auction was a ten-minute time glass (used to prevent readers hogging popular titles), now redundant — although some pubs still had notices requesting patrons not to monopolise the latest edition of the paper for more than five minutes.95 There were also continuities. Even when ‘national’ London papers such as the Daily Mail became more affordable and available, the places where they were read affected how they were read and interpreted.

Periodical Time

Many readers were fine-tuned to the periodical-ness of newspapers and magazines, waiting for the next instalment of a novel or the detailed dispatches from a faraway battle to supplement the telegraphed headlines. John O’Neil used the latest issue of the local paper in the same way as polar explorers used two-year-old newspapers, to mark time and create rituals. He also had a sophisticated understanding of the temporal nature of news-gathering and publishing practices. The processes of publishing a paper or magazine developed so as to require regularity, yet neither the world that newspapers claimed to report, nor the world of readers in particular places at particular times, were regular. Publishing schedules turned the chaotic flow of events into a regular pulse, a new issue or edition. This untamability was seen in the ‘unpredictable ebb and flow of news’ at the different telegraph offices throughout the country, creating a staffing nightmare for the telegraph companies in the days before zero-hours contracts.96 Publishers imposed a fiction of order and regularity on this flow of chaos, and readers recognised its constructedness, as seen in the old jest that there is always just enough news to fill a paper every day.97 Sommerville has argued that ‘Periodicity is about economics. There can be news without its being daily, but if it were not daily a news industry could never develop’ because of the need to fully utilise expensive printing machinery.98 However, the rhythms of newspaper publication often left machines idle. More broadly, even in the twenty-first century, with rolling news and live Tweeting, news periodicity continues: electronic news publishers have adapted to modern consumers’ habits, releasing their best material during commuting times, lunchtime and evenings.99

Conclusions

Newspaper-reading happened at particular times, negotiated between publishers and readers. Readers understood that publishing conventions such as the date on the title page, or the claim of novelty, were fictions and constructions. In a regional market centre like Preston, most newspapers began by publishing on Saturday, the main market day, and the three papers that published bi-weekly all chose the second most important market day, Wednesday, for their mid-week edition. Regional and metropolitan papers also worked around readers’ routines, publishing at weekends when there was more leisure time for reading. News-reading declined in the summer, and increased in the autumn and winter when Parliament was in session and, in later years, when the football season was running and outdoor pursuits reduced. The move from weekly to bi-weekly and eventually to daily publishing rhythms enabled a significant change in reading habits for people in Preston (but changes happened more slowly for working-class readers, particularly women). The halfpenny evening paper, for example, allowed many to read news at home in the evening for the first time, and was probably more significant than the provincial morning paper for most readers. Times of news-reading were also dictated by less predictable events, such as the death of a statesman, a famous boxing match, strikes or wars. Telegrams posted in windows, special editions and new wartime publications catered for readers’ demands in these situations. Readers became accustomed to receiving the latest news, and publishers were happy to respond to this growing demand.

The next two chapters interrupt this case study of newspaper-reading in one town, to introduce the local press as a national phenomenon. We then return to the readers, most of whom preferred the local newspaper.

1 Margaret Beetham, ‘Open and Closed: The Periodical as a Publishing Genre’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 22 (1989), 96–100 (p. 96).

2 Mark W. Turner, ‘Periodical Time in the Nineteenth Century’, Media History, 8 (2002), 183–96 (p. 185), https://doi.org/10.1080/1368880022000030540. See also D. Woolf, ‘News, History and the Contraction of the Present in Early Modern England’, in The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe, ed. by Brendan Maurice Dooley and Sabrina A. Baron (London: Routledge, 2011), pp. 80–118.

3 Víctor Goldgel-Carballo, ‘“High-Speed Enlightenment”’, Media History, 18 (2012), 129–41 (p. 133), https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2012.663865

4 Stuart Sherman, Telling Time: Clocks, Diaries, And English Diurnal Form, 1660–1785 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), pp. ix-x.

5 Sherman, p. x. See also Linda K. Hughes and Michael Lund, The Victorian Serial (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991), pp. 60–61 on competing views of time in the Victorian era.

6 Hughes and Lund, p. 63.

7 Beetham, ‘Open and Closed: The Periodical as a Publishing Genre’, p. 96.

8 James Mussell, Science, Time and Space in the Late Nineteenth-Century Periodical Press: Movable Types (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), p. 94; Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006), p. 33., paraphrased in Sherman, p. 112.

9 Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000); Mussell, pp. 15, 92 takes an opposite point of view.

10 ‘About half-past 1 o’clock on Saturday morning, as mentioned in a late edition of last week’s Courier […]’ Manchester Courier, 28 September 1850 p. 9; ‘To readers and writers. Cricket. We beg our Cricket contributors to send us their communications as early as possible in the week.’ Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 12 June 1880, p. 7.

11 Margaret Beetham, ‘Time: Periodicals and the Time of the Now’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 48 (2015), 323–42 (p. 330), https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2015.0041

12 John Garrett Leigh, ‘What Do the Masses Read?’, Economic Review, 4 (1904), 166–77 (p. 175); Preston Guardian (hereafter PG) Jubilee supplement, 7 February 1894, p. 13.

13 David Ayerst, Guardian: Biography of a Newspaper (London: Collins, 1971), p. 129.

14 Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge, annual report, 1872, p. 2, Livesey Collection, University of Central Lancashire. ‘Early frequenters of the News Room’ at the Winckley Club, Preston, were anxious to see the Liverpool papers at 8.30am: Winckley Club suggestion book, 18 January 1879, LRO DDX 1895, Lancashire Archives.

15 ‘Earlier arrival at Preston (11.35 noon) of the Glasgow Herald’, advertisement, Preston Herald (hereafter PH), 27 September 1873, p. 7.

16 For arrival times of Manchester evening papers, see Winckley Club suggestion and complaints book, 6 December 1872, 20 February 1885; for London morning papers, 15 December 1875, all LRO DDX 1895, Lancashire Archives.

17 Jean M. Shansky, Yesterday’s World (Preston: Smiths, 2000), p. 21, describing the early 1900s.

18 ‘Social and family life in Preston, 1890–1940’, transcripts of recorded interviews, Elizabeth Roberts archive, Lancaster University Library (hereafter ER; the letters P, B or L at the end of the interviewee’s identifier denotes whether the interviewee was from Preston, Barrow or Lancaster): Mr Mr M2P (b. 1901), p. 3. The transcripts are being digitised, with some available at www.regional-heritage-centre.org

19 Phoebe Hesketh, What Can the Matter Be? (Penzance: United Writers, 1985), p. 111; see also ‘[My mother] always read the [Evening] Post at night, from beginning to end’: Mrs J1P (b. 1911), ER.

20 Mr G1P (b. 1907), ER.

21 Anderson, pp. 35–36.

22 Brendan Maurice Dooley, ‘Introduction’, in The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe, ed. by Brendan Maurice Dooley and Sabrina A. Baron (London: Routledge, 2011), p. 10; Mussell, p. 94, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203991855

23 Lucy Brown, Victorian News and Newspapers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), p. 273.

24 ‘Rural Footpaths’, letter from ‘An Old Man’, Correspondence, Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC), 11 September 1852, p. 6.

25 Anon., ‘A Chapter On Provincial Journalism’, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine, July 1850, 424–27 (p. 424).

26 For half-holidays see Dave Russell, Football and the English: A Social History of Association Football in England, 1863–1995 (Preston: Carnegie, 1997), p. 13.

27 Beetham, ‘Open and Closed: The Periodical as a Publishing Genre’, p. 96.

28 Richard Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), pp. 86–87; Graham Law, Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000).

29 Mr B10P, written account of life in Edwardian Preston, ER.

30 Leigh, p. 176.

31 Mr B1B (b. 1897), ER.

32 Florence Eveleen Eleanore Olliffe Bell, At the Works: A Study of a Manufacturing Town (Middlesbrough: University of Teesside, 1907/1997), pp. 146–62.

33 Mrs B1P (b. 1900), ER.

34 ‘A Library for the New Workhouse,’ PG, 30 January 1869, p. 2.

35 PC, 7 February 1857.

36 ‘The pros and cons of church-going,’ letter from F. O. Morris, The Globe, 3 December 1870, pp. 1–2.

37 Laurel Brake, ‘Magazine Day’, in Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism in Great Britain and Ireland (DNCJ), ed. by Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor (Ghent; London: Academia Press; British Library, 2009); Hughes and Lund, p. 10.

38 The almanac was edited and published by James T. Staton, ‘editor oth “Bowton Loominary”’, and the imprint includes J. Harkness of Church Street and J. Foster of Maudland-Bank in Preston, among others.

39 Brian E. Maidment, ‘Beyond Usefulness and Ephemerality: The Discursive Almanac 1828–1860’, in British Literature and Print Culture, ed. by Sandro Jung (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2013), pp. 158–94; Brian E. Maidment, ‘Almanac’, in DNCJ online edition.

40 ‘No London papers at the Club on Christmas Day. It has not occurred before in my recollection’, Winckley Club complaints book, 25 December 1877, Lancashire Archives, LRO DDX 1895; C. Baggs, ‘More gleanings from public library annual reports’, LIBHIST email discussion message, 6 January 2003, https://www.jiscmail.ac.uk/cgi-bin/webadmin?A0=lis-libhist

41 Preston Evening News, 7 June 1871, p. 2. The same seasonal dip in sales still holds true in the twenty-first-century, according to one Preston wholesale newsagent.

42 J. Haslam, ‘What Harpurhey Reads’, Manchester City News, 7 July 1906.

43 For Bright’s Intelligencer, see Andrew J. H. Jackson, ‘Provincial Newspapers and the Development of Local Communities: The Creation of a Seaside Resort Newspaper for Ilfracombe, Devon, 1860–1’, Family & Community History, 13 (2010), 101–13 (p. 102), https://doi.org/10.1179/146311810X12851639314110; John K. Walton, ‘Visitors’ Lists’, in DNCJ online.

44 Margaret Beetham, ‘“Oh! I Do like to Be beside the Seaside!”: Lancashire Seaside Publications’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 42.1 (2009), 24–36, https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0060

45 Julia Kristeva, ‘Women’s Time’, in The Kristeva Reader, ed. by Toril Moi (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991), pp. 187–213.

46 J. F. Nisbet, ‘The World, the Flesh and the Devil’, The Idler, November 1896, p. 548.

47 Paddy Scannell, Radio, Television, and Modern Life: A Phenomenological Approach (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), p. 149.

48 Beetham, ‘Time’, pp. 332–34.

49 Letter from John Clay to Lord Stanley, 25 January 1854, in Walter Lowe Clay, The Prison Chaplain: A Memoir of the Rev. John Clay, B. D. with Selections from His Reports and Correspondence, and a Sketch of Prison Discipline in England (Cambridge: Macmillan, 1861).

50 See also 1896–97 annual report, Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre, Barrow.

51 For trade union facilities, see Alison Andrew, ‘The Working Class and Education in Preston 1830–1870: A Study of Social Relations’ (doctoral thesis, University of Leicester, 1987), p. 114; PC, 15 November 1862, 28 November 1863.

52 PC, 24 January 1874; Diaries of Anthony Hewitson, Lancashire Archives DP512/1/5, 28 February 1872.

53 For election supplements in the Warrington Examiner, see Hartley Aspden, Fifty Years a Journalist. Reflections and Recollections of an Old Clitheronian (Clitheroe: Advertiser & Times, 1930), p. 21. For ‘rolling news’, see Tom Smith, ‘Religion or Party? Attitudes of Catholic Electors in Mid-Victorian Preston’, North West Catholic History, 33 (2006), 19–35 (p. 5); PG, 3 September 1870, p. 5; Mr B7P (b. 1904), ER.

54 Jonathan Rose, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (London: Yale University Press, 2001), pp. 65–66.

55 John O’Neil, The Journals of a Lancashire Weaver: 1856–60, 1860–64, 1872–75, ed. by Mary Brigg (Chester: Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1982), Thursday 6 August 1857.

56 O’Neil diaries, 3 July 1859.

57 Printers’ Register, 6 July 1868, p. 171.

58 Letter including circulation figures from Glasgow Herald editor William Robinson to Manchester Guardian editor A. P. Wadsworth, 27 October 1954 (Manchester Guardian Archives 324/5A, John Rylands Library).

59 ‘The war and the newspapers’, Supplement to Printers’ Register, 6 August 1870, p. 186.

60 ‘Miscellaneous,’ London, Provincial, and Colonial Press News, 15 August 1870, p. 18.

61 PG, 3 September 1870, p. 5.

62 Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 9, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195390346.001.0001

63 Rendezvous with the Past: One Hundred Years’ History of North Staffordshire and the Surrounding Area, as Reflected in the Columns of the Sentinel, Which Was Founded on January 7th, 1854 (Stoke-on-Trent: Staffordshire Sentinel Newspapers, 1954), p. 155.

64 PC, 3 September 1870, pp. 1, 4.

65 A. R. Bradford, Drawn by Friendship: the Art and Wit of the Revd. John Thomas Wilson (New Barnet: Anne R. Bradford, 1997).

66 J. B. Paterson, ‘Western Evening Herald’, Quadrat, a Periodical Bulletin of Research in Progress on the British Book Trade, 12, 2001.

67 Woolf, p. 81.

68 Joel H. Wiener, The Americanization of the British Press, 1830s–1914: Speed in the Age of Transatlantic Journalism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 38, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230347953; see also Hughes and Lund, pp. 10–11; Scannell, p. 155.

69 Winckley Club Suggestion and Complaint Book, 1870–88, entries for 6 November, 25 December and 26 December 1877, Lancashire Archives DDX 1895 acc 6992, box 5.

70 O’Neil diaries, Saturday 5 December 1857.

71 John William Robertson Scott, The Day Before Yesterday: Memories of an Uneducated Man (London: Methuen, 1951), p. 86.

72 Uriel Heyd, Reading Newspapers: Press and Public in Eighteenth-Century Britain and America (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2012), p. 3.

73 Richard Wright Procter, Literary Reminiscences and Gleanings (Manchester: Thomas Dinham, 1860), p. 33.

74 Beetham, ‘Open and Closed’, p. 96; Mark W. Turner, ‘Time, Periodicals, and Literary Studies’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 39 (2006), 309–16 (p. 311), https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2007.0014

75 Leah Price, How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2012), Chapter 7, ‘The book as waste’, https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691114170.001.0001

76 For a detailed analysis of the bound volume, see Laurel Brake, ‘The Longevity of “Ephemera”’, Media History, 18 (2012), 7–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2011.632192

77 Bryan Little, ‘Two Chronicles in a Fight to the Death’. Bath Evening Chronicle. June 1877, Centenary supplement marking one hundred years of daily publication.

78 John B. Hood, ‘The Origin and Development of the Newsroom and Reading Room from 1650 to Date, with Some Consideration of Their Role in the Social History of the Period’ (unpublished FLA dissertation, Library Association, 1978), pp. 355–57.

79 James Duff Brown and W. C. Berwick Sayers, Manual of Library Economy, 3rd edn (Grafton & Co., 1920), p. 385.

80 ’Sale of newspapers at Avenham Institution’, PC, 31 December 1881.

81 Michael Thompson, Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 7, 9, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1rfsn94

82 David H. Stam and Deirdre C. Stam, ‘Bending Time: The Function of Periodicals in Nineteenth-Century Polar Naval Expeditions’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 41 (2008), 301–22 (pp. 304, 309, 312), https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0054

83 Figures from Winckley Club minute books, Lancashire Archives DDX 1895.

84 The sharp rise in the value of the Preston Guardian in 1900 was caused by a member of the newspaper owner’s family, Mr J. Toulmin, paying more than the original cover price; this could be an error in the minutes book, a joke or a blatant attempt to inflate its value for publicity purposes.

85 Lee Erickson, The Economy of Literary Form: English Literature and the Industrialization of Publishing, 1800–1850 (London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), p. 9.

86 Arthur Aspinall, ‘The Circulation of Newspapers in the Early Nineteenth Century’, The Review of English Studies, 22 (1946), 29–43; Brown, pp. 52–53; Alan J. Lee, The Origins of the Popular Press in England: 1855–1914 (London: Croom Helm, 1976) Tables 1–6, pp. 274–79.

87 PC, 19 October 1872.

88 PH, 29 October 1890, p. 5. For similar uses of local papers, see O’Neil diaries, 15 June 1861; Rendezvous with the Past, p. 15.

89 Kendal Mercury, 28 July 1855, p. 5.

90 Thompson, p. 7.

91 Garvey, p. 36.

92 Wiener; Mark Hampton, Visions of the Press in Britain, 1850–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), pp. 89–92.

93 The Central Working Men’s Club spent £33 11s 10d on ‘newspapers, &c’ in 1873 and recouped £8 8s 5d from their sale: PC, 24 January 1874.

94 On Sunday reading in the pub, see William Cooke Taylor, Notes of a Tour in the Manufacturing Districts of Lancashire: In a Series of Letters to His Grace the Archbishop of Dublin (London: Duncan and Malcolm, 1842), p. 136.

95 [J. F. Wilson], A Few Personal Recollections, by an Old Printer (London: Printed for private circulation, 1896), p. 11; Lionel Robinson, Boston’s Newspapers (Boston: Richard Kay Publications, for the History of Boston Project, 1974), p. 3.

96 Jonathan Silberstein-Loeb, ‘The Structure of the News Market in Britain, 1870–1914’, Business History Review, 83 (2009), 759–88 (p. 781).

97 Versions of this joke are found in seventeenth-century critiques of the emergent newspaper, in Henry Fielding’s novel Tom Jones (1749) and, for example, in the Ladies’ Repository 18, 1858 (‘New York Literary Correspondence’, p. 505): ‘The rustic wondered how it happened that there was always just enough news to fill up the village weekly sheet’.

98 Charles John Sommerville, The News Revolution in England: Cultural Dynamics of Daily Information (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 4.

99 Deborah Robinson and Andrew Hobbs, ‘How the Audience Saved UK Broadcast Journalism’, in The Future of Quality News Journalism: A Cross-Continental Analysis, ed. by Peter J. Anderson, George Ogola, and Michael Williams (New York: Routledge, 2014), pp. 162–83 (p. 165), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203382707