4. What They Read: The Production of the Local Press in the 1860s

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.04

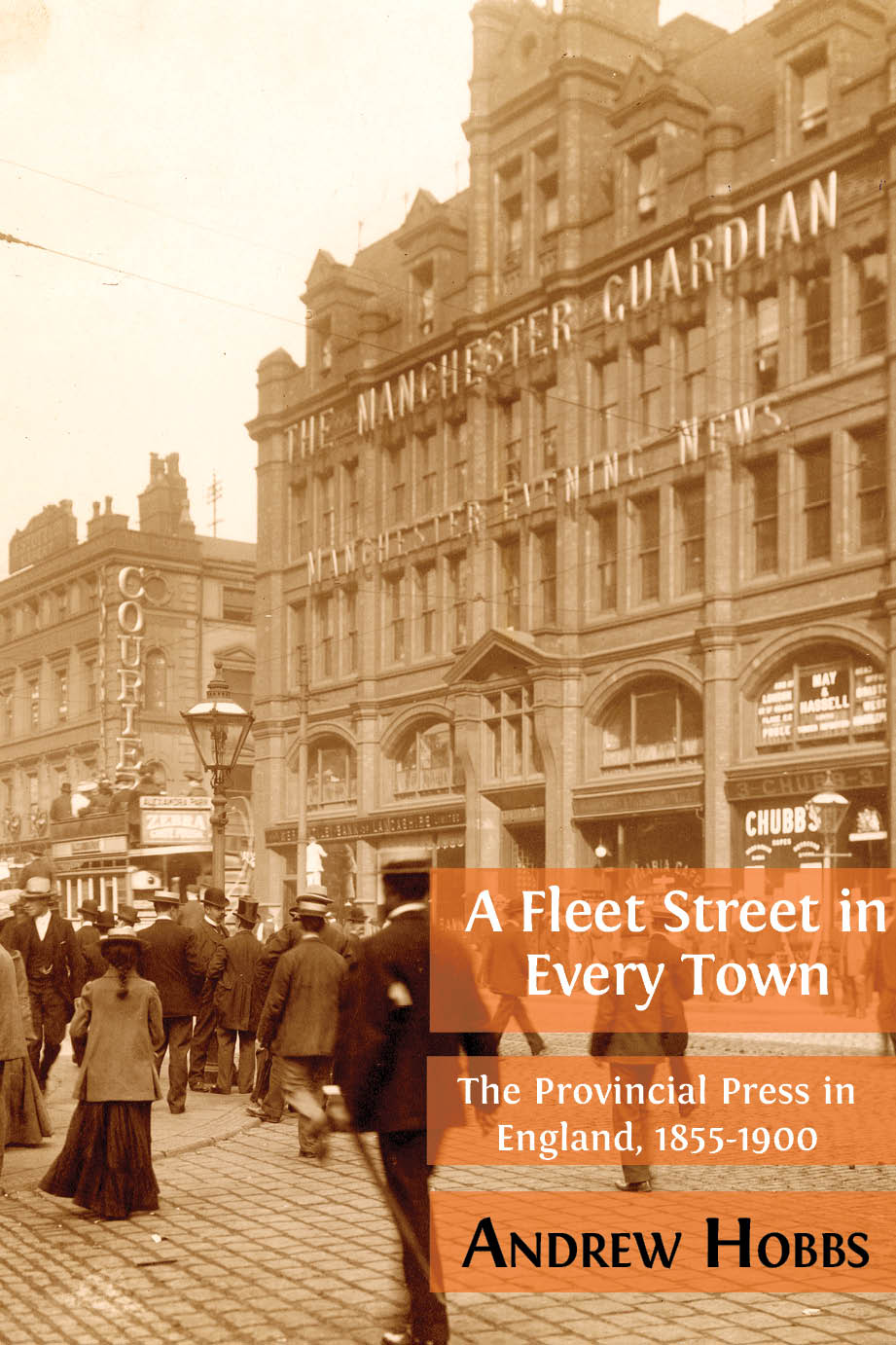

We know who the readers of local newspapers were, we know where they read them, and when. But what exactly were they reading? This chapter explores the content of the mid-Victorian newspaper, how it was written, assembled and distributed, and by whom. We will follow a typical Victorian journalist, Anthony Hewitson, working in the provinces (Preston), on the most popular type of paper, a weekly, during one week in the 1860s (the following chapter moves forward to the 1880s). Structuring these two chapters around two weeks in Hewitson’s working life brings alive the working methods and organisation of local newspapers and the distinctive routines, networks and attitudes of their personnel. This is a complex world of distinctive but connected local print cultures, peopled by a surprising variety of newspaper contributors, producing content that was significantly different from that of the smaller market of London dailies like the Times and the local newspapers of the twenty-first century. After a short biographical sketch of the journalist, Anthony Hewitson, he is placed within the national and local ecologies of periodicals at that time, before we follow him through a typical working week.

Anthony Hewitson (1836–1912), a printer who became a journalist and newspaper proprietor, frames this chapter. His diaries, covering nineteen of the forty-eight years between 1865, when he was a reporter on the Preston Guardian, and his death in 1912, are the only known diaries of a provincial Victorian journalist. ‘The transition from the composing room to the reporters’ office, and thence to the editor’s chair, has been frequently achieved’, so Hewitson’s career was not unusual, moving from a printing apprenticeship to ten years of reporting, twenty-two years as owner-editor of the Preston Chronicle and fifteen as owner of the Wakefield Herald.1 Hewitson was born in Blackburn, Lancashire, on 13 August 1836, the eldest son of a stonecutter. He attended the village school at Ingleton in Yorkshire, and in 1850 began a printing apprenticeship on the Lancaster Gazette. While an apprentice he continued to educate himself, learning shorthand and attending essay classes, where he mixed with political and theological radicals, including the poet Goodwyn Barmby, then minister of the Free Mormon Church in Lancaster (where he held the title of Revolutionary Pontifarch of the Communist Church).2 Hewitson’s reporting week is a good introduction to the people and processes involved in the production of the provincial press in the second half of the nineteenth century, and supports the idea that producers and readers of the local press were often members of the same interpretive communities.

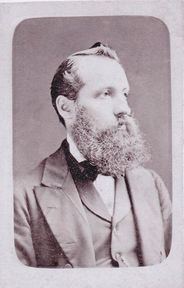

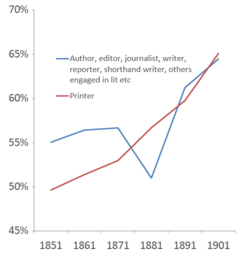

Like most mid-Victorian journalists, Anthony Hewitson lived and worked outside London (Fig. 4.2). In September 1865 he was chief reporter of the Preston Guardian, a major bi-weekly newspaper covering North and East Lancashire, an area larger than most English counties. Compulsory Newspaper Stamp Duty had been repealed in 1855, two years before Hewitson finished his apprenticeship, greatly increasing the opportunities for an able and hard-working young man. His printing and composing (typesetting) background was not unusual for a mid-nineteenth-century reporter, nor his rapid job moves: in the year after July 1857, when he finished his apprenticeship, he worked in Kendal, Brierley Hill in Staffordshire, Wolverhampton and Preston.3 He settled in Preston, on the Radical Preston Guardian initially, as compositor and reporter, then on the Whig Preston Chronicle as reporter, at 28/- a week. By September 1861, if not before, he was earning a comfortable £2 6s a week on the Conservative Preston Herald, where he became ‘manager’. He may have returned to the Chronicle before rejoining the Preston Guardian as a reporter in December 1864, and by June 1865 was chief reporter. By now he had mastered news reporting, descriptive writing and some leader-writing, and adopted the pen-name of ‘Atticus’, for a series of irreverent sketches of local officials and institutions, in which he developed a distinctive style that made him Preston’s best-known writer for the rest of the century.4

Fig. 4.1. Anthony Hewitson, Preston reporter, editor and newspaper proprietor. Carte de visite, photo by C Sanderson, Commercial Buildings, 130A Castle St., Preston, used with permission of Hewitson’s great-grandson

Martin Duesbury, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 4.2. Print personnel in England and Wales, 1851–1901, showing the proportion outside London.5 Author’s graph, CC BY 4.0.

National Periodicals Ecology

Hewitson was chief reporter of the Preston Guardian. This bi-weekly paper, published every Saturday and Wednesday, was part of an ecology of London and provincial papers worth sketching briefly here. London morning newspapers such as the Times and the Daily Telegraph are the most well-known type of Victorian paper. These two titles have survived, but other London dailies such as the Daily News (1846–1960), Morning Chronicle (1770–1865), Morning Advertiser (1793–1965) and Morning Post (1772–1937) were also current. These broadsheets, full of classified advertisements (on some days more than half of the Times was advertising), high politics, diplomacy and commercial news focused their coverage on national institutions and events in south-east England, where they sold most copies.6 London evening papers included the Standard (est. 1827), the Pall Mall Gazette (1865–1923) and the Globe (1803–1923); from 1868 the more downmarket halfpenny Echo became popular. Traditionally, London evenings took most of their news from the morning papers, supplemented by original articles of commentary and analysis, and reviews. Small numbers of these London papers (with the possible exception of the Echo, which had higher sales) could be found in reading rooms and middle-class homes in the provinces. The abolition of the compulsory penny stamp in 1855 ended cheap postal distribution of London papers, leading to a significant decline in their provincial circulation.7

The popular London Sunday papers were less reliant on postal distribution and were aimed at a different readership, the lower middle classes. The News of the World (1843–2011) sold nearly 110,000 in 1855, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (1842–1931) some 2–3,000 fewer and Reynolds’s Newspaper (1851–1967) nearly 50,000 by 1855, the latter particularly popular in the old Chartist strongholds of Lancashire and the West Riding.8 These Sunday newspapers featured sensational, titillating crime reports, literary/humorous tit-bits, gossip and practical advice via ‘Notices to Correspondents’, alongside political and foreign news; they introduced fiction from the 1880s, led by the News of the World, and more sport.9 Other popular London weeklies included the Illustrated London News (1842–2003), the Illustrated Police News (1864–1938) and specialist sporting and religious papers. The weeklies had more varied, magazine-like content than the London dailies.

Regional morning newspapers were creations of the post-Stamp Duty era, and had a status second only to the London dailies, on which they were modelled.10 In their circulation areas, they probably outsold all London dailies (see Table 7.11). Many Victorian commentators acknowledged that the provincial dailies, when treated as a body rather than as individual titles, were as significant as the London press:

The provincial morning newspapers […] have, as a whole, a greater weight in the conduct of the affairs of the Empire than the morning papers of London […] the district served by the London press […] does not contain more than six or seven million persons, and to the remaining thirty millions the London press, with the exception of a few of the more widely circulating dailies, is little more than a name.11

The Manchester Guardian (1821–) and the Leeds Mercury (1718–1939) were particularly close in style to the Times. These two papers were already well-established as weekly and bi-weekly papers, while other successful provincial dailies were new titles, such as Liverpool’s Daily Post (1855–) and Sheffield’s Daily Telegraph (1855–). Most sold at a penny by the mid-1860s, with advertising providing most of the income. They were expensive to run, requiring costly telegraphic news and ‘original matter’, and overtime payments for printers working at night.12 Some of these titles set up weekly companion news miscellanies, which became more popular — and profitable — than their daily stablemates, although the genre had largely died out by the 1930s. Early titles included the Glasgow Times (1855–69) and the Manchester Weekly Times (1855–1922), with the Dundee-based People’s Journal (1858–1990) selling more than 100,000 by the late 1860s. They were published on Saturday, and aimed mainly at working-class readers, priced at a penny or twopence. They featured a summary of the week’s regional, national and international news, slanted towards the more sensational stories, plus middle-brow magazine-style material aimed at a family audience, including serial fiction.13 In the 1870s and 1880s they became the main publishing platform for new novels (Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles, for example, was commissioned by the publisher of the Bolton Journal).14 As Graham Law has noted, they published many journalistic genres later identified with the ‘New Journalism’ of the 1880s and 1890s.

While the provincial morning and weekly papers covered whole regions, most (but not all) of the traditional weeklies and bi-weeklies tended to be more local in their coverage and circulation. They were the oldest type of provincial newspaper, dating back to the early eighteenth century, with the Norwich Post (1701–13) and the Bristol Post-Boy (1702–15) some of the first. The local newspaper market expanded in the 1830s after advertising duty and paper duty were halved, and stamp duty was reduced from 4d to 1d, between 1833 and 1836. (Stamp duty was both a tax — bad for newspapers — and a postage fee — good value for those titles needing postal distribution, particularly London papers.) The highest-circulation papers went from weekly to bi-weekly, and new titles entered the market. The content tended towards a newspaper-magazine hybrid, mixing news and features. Weeklies with good circulations and plenty of advertising could be very profitable — by the 1840s the Hampshire Advertiser made £2,000 a year and the Birmingham Journal £5,000.15 In rural areas, weeklies were typically published from the market town and circulated in all the areas oriented to that market, whilst in more urban areas such as Manchester or Liverpool, they sold across a smaller but much more densely populated territory. There were also some county papers, such as the Westmorland Gazette, published from the county town of Kendal, with an editorial remit to cover the whole shire.

The abolition of the three main newspaper taxes between 1853 and 1861 profoundly altered the economics of newspaper publishing, enabling publishers to reduce their cover prices to as little as a halfpenny, increase their circulations and therefore charge more for advertising, their main source of income (as it had been since the eighteenth century; accurate figures are scarce, but by 1849 the Buckinghamshire Herald received three or four times as much income from advertising as from sales, for example).16 The number of local weekly papers roughly doubled, from 363 in 1856 to 698 in 1866, according to Mitchell’s Newspaper Press Directory (Introduction, Table 0.1). Weeklies were at the centre of this golden age of the local press.17

However, the late 1850s and the first half of the 1860s were a volatile time for local newspapers, as many new entrants joined — and left — the market and experimented with new formats and publishing models. Throughout the nineteenth century, but particularly at this time, the most common business model for a newspaper was to launch with too little capital, lose a great deal of money and then fold in a matter of weeks.18

Magazines accounted for only thirty per cent of the periodicals market in the 1860s, newspapers around seventy per cent.19 In contrast to newspapers, most magazines were published in London, with the most popular featuring serial fiction, alongside ‘humour, fiction, poetry, gossip […] general interest articles and answers to correspondents’. These included Cassell’s Illustrated Family Paper (1853–1932), Chambers’s Journal (1832–1956), the Family Herald (1842–1940), London Journal (1845–1928) and All The Year Round (1859–95).20 One of the only provincial magazine genres to be successful was the satirical and comic periodical of the late 1860s to the mid-1890s, often named after small but annoying creatures. Notable examples included Liverpool’s Porcupine (1860–1915) and Manchester’s City Jackdaw (1874–84).21

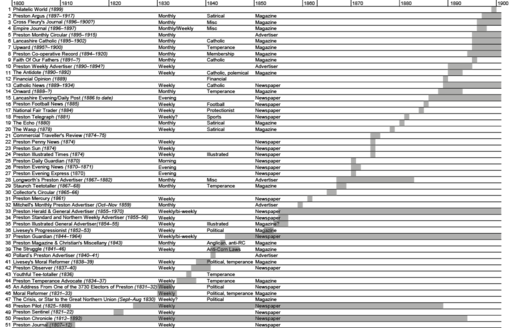

Table 4.1. Newspapers and periodicals published in Preston, Lancashire

1800–1900.22 Author’s diagram, CC BY 4.0.

Local Periodical Ecology:

Preston

The case study of Preston, one node in the national network constituted by the local press, reveals the number, local distinctiveness, diversity, dynamism, even instability, of local newspapers and magazines. ‘The transformation of Victorian Britain and Ireland brought into being unprecedented, self-authenticating local cultures that operated under different aesthetic laws and created their own traditions,’ according to Brian Maidment, and this included local print cultures.23 Preston’s distinctive print ecology was influenced by its geographical position, economy and culture. Its newspapers had a wider circulation than titles in most towns, reflecting its status as a market and administrative centre, and possibly its sub-regional importance as a rail hub. But Preston was not unusual in the number and variety of its papers and periodicals, many of which are not listed in the British Library catalogue, and have left no surviving copies. The main titles each had their distinct histories, moulded by their founders and subsequent owners, the periods in which they were published, and by their competitors, local and non-local.

Preston’s newspaper history began in the 1740s, with the first of three short-lived titles published in the eighteenth century, and from 1807 onwards was served continuously by one or more paper of at least weekly frequency, sometimes by as many as eight rival publications. At least fifty-one titles were published during the nineteenth century (Table 4.1 above). Three of Preston’s four longest-running weekly and bi-weekly papers were established in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Preston Journal (1807–12) became the Preston Chronicle (1812–93) when it changed hands in 1812, and was a Liberal paper for all but the last three years of its existence. After the Guardian launched in 1844, the Chronicle’s sub-regional circulation area shrank to Preston and a dozen miles around. Its style was more literary and magazine-like than other Preston papers. In 1854, the last year in which government Stamp Duty figures provide reliable circulation figures, the Chronicle sold 1,769 copies per week.24 A second long-running weekly, the Conservative Preston Pilot (1825–88), was launched in 1825, although by the 1860s it had transmogrified into a Lytham paper, despite its name. As in Charles Dickens’s fictional town of Eatanswill in The Pickwick Papers, Preston’s newspapers often traded insults. In 1847 the Chronicle described the Pilot as ‘a pilot […] whose dead-weight and unskillfulness would blunder a cork boat to the bottom and contrive to wreck a buoy of India-rubber […] our dear old doting grandmamma […] we shall be obliged to give our ancient relative a cold bath in the [river] Ribble, for the benefit of her delirious fever […]25 The Pilot was of poor journalistic quality, patrician Tory in tone, and increasingly out of step with local Conservatives and in fact any readers at all. In 1854 it sold a mere 933 copies per week.

The staid world of Preston’s newspapers was disrupted in 1844, with the launch of the Preston Guardian (1844–1964), the town’s most successful paper, in terms of circulation, profits and reputation. It was set up by teetotaller and anti-corn-law campaigner Joseph Livesey, a wealthy, self-made cheesemonger who had already published half-a-dozen polemical weeklies, and was involved in most of Preston’s progressive causes.26 The Guardian was a sub-regional paper from its inception; its strength was its comprehensive, relatively balanced news reporting and its accessible style under Livesey and his sons. The Guardian was better in form and content than its two Preston rivals, achieving a circulation in its first year higher than their combined sales. Hewitson claimed it was subsidised by a national pressure group, the Anti-Corn Law League, at its launch, and Livesey admitted that it did not make a profit until its fourth year.27 By 1854 it was the tenth best-selling provincial paper in the country (7,288 copies per week, less than the Manchester Guardian‘s 9,677, but more than the Sunday Times’s 7,154). The repeal of compulsory Stamp Duty in 1855 encouraged the Guardian to go from weekly to bi-weekly, and in 1859 Livesey sold the booming paper to his protégé, George Toulmin, for £6,600, the equivalent of around £1 million today, suggesting high profitability. Toulmin, a Radical, had trained as a printer in Preston, before working on a Conservative newspaper, the Bolton Chronicle (which he continued to manage until 1882). Such ‘switching sides’ was not unusual among printers and journalists. Toulmin brought a sterner, less populist tone to the Guardian, but nevertheless made a great success of it. By 1866 the Preston Guardian was selling 13,600 copies a week.28 The local market for weeklies was mature even before mid-century in Preston, and the Guardian had probably only succeeded in breaking into it because of Livesey’s exceptional journalistic ability, good business sense and the help of an Anti-Corn-Law League subsidy, against two unremarkable competitors.

The Preston Guardian was unusual among the town’s papers in being enmeshed in a national political network of middle-class radical Nonconformist individuals and organisations, as shown by some of its editors and staff. John Hamilton was a Preston Guardian reporter who went on to edit the radical London daily the Morning Star; he was due to become editor of the Preston Guardian in 1860 but became fatally ill.29 John Baxter Langley (editor, 1861–63), also associated with the Morning Star, was a Chartist and radical campaigner and lecturer in support of free libraries, mechanics’ institutes and co-operation.30 Washington Wilks, co-editor of the Morning Star and proprietor of the Carlisle Examiner, wrote leaders for the Preston Guardian, and Thomas Wemyss Reid (editor 1864–66) went on to edit the Leeds Mercury and was friendly with the Liberal leadership at national level. The Guardian even had a future Fenian on its staff, John Boyle O’Reilly (1844–90), an Irish schoolmaster’s son who joined the paper as a printer in 1859 before moving into reporting, so would have been a contemporary of Hewitson. He joined the local militia, the 11th Lancashire Rifle Volunteers and became an NCO, able to afford the five-guinea yearly subscription for officers. He left the Guardian in 1863 to return to Ireland, where he was active in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (the ‘Fenians’) by 1865. In 1866 he was arrested and sentenced to death, commuted to life imprisonment; he eventually escaped to the US, where he became a leader of the Irish-American community, editing the Boston Pilot.31

The Conservative Preston Herald (1855–1971) became the only serious competitor to the Preston Guardian, which described it as ‘a subsidised Tory organ […] a journal in which so many outrages upon decency have been tolerated, in the supposed interest of a political party […] vulgar diatribes […] putrescent slime […] gross stupidity or determined mendacity […]’.32 It was launched in 1855 by printer Henry Barton, using partly printed sheets (pre-printed pages produced in London, to be supplemented by local advertising and editorial, a common publication method for smaller newspapers).33 The Herald struggled until it was indeed subsidised by the Tories, on its purchase by the local Conservative association in 1860.34 Its editor in 1860–61, Sidney Laman Blanchard, was probably the most cosmopolitan journalist to pass through Preston. The eldest son of Samuel Laman Blanchard (author, Liberal Party journalist and friend of Dickens), he began his career as Disraeli’s private secretary.35 He studied in Paris in the early 1850s, and edited the Bengali Hurkaru in India in the mid-1850s, resigning in 1857 after his attacks on Lord Canning led to the paper’s suspension.36 On the Herald’s Conservative takeover, it strove to imitate the Radical Guardian in its sub-regional reach and comprehensive news service (with some success, although at a financial loss), but was more populist in content. In the early twentieth century it was subsidised by the Earl of Derby’s family (such political subsidy was not unusual, particularly for Conservative papers).37 By the 1860s the only other nineteenth-century Preston titles that had survived for more than a year were Joseph Livesey’s anti-Corn-Law and temperance publications, and the Preston Observer (1837–40), one of seven short-lived weekly newspapers.38

The births, long lives, failures to thrive, forced marriages and deaths of Preston’s publications largely confirm other studies of the provincial press and the complex set of factors necessary (but rarely sufficient) for success in this dynamic, unstable period of newspaper history.39 This is the world in which Anthony Hewitson went about his business as a reporter in Preston in 1865.

A Week in the Life of a Provincial Newspaper Reporter, 1865

Friday 22 September 186540

Got up at six; had a shower bath; wrote till eight; went to office at nine; more writing; got two columns about Exhibition into The Times; went to a dinner at Theatre in evening given by Lieutenant Colonel Birchall and Major Wilson to members & friends of Artillery Corps of Preston. Got home after two in morning.

This extract from Anthony Hewitson’s diary begins on a Friday, the busiest day of the week, when the main edition of the paper went to press for Saturday publication. He worked at home before breakfast, arriving at the office on Fishergate, the main street, at nine. For most of the previous week he had been reporting the opening of the Preston Exhibition of Art and Industry (Fig. 4.3) for the Guardian. Hewitson was also a local correspondent for other newspapers, including the Times, for whom he wrote a two-column report of the exhibition.41 He was part of a national network of local correspondents, some of them ‘moonlighting’ staff journalists, others freelance, who supplied news to regional dailies in other places, and to metropolitan papers such as the Times.

In the evening Hewitson attended a dinner for the local artillery volunteers, taking a shorthand note and writing an article of almost 2,000 words, which was published early the following morning, while the speakers were still asleep. Hewitson’s shorthand enabled him to capture the atmosphere and bon mots of the speakers — the invention of shorthand added new descriptive power to journalism from the 1830s onwards, and was almost as significant as the leap from silent film to ‘talkies’ a century later.42 The dinner, attended by mill owners, solicitors, doctors and the volunteers themselves, was typical of the type of event covered by a local newspaper, which was far better at reporting the lives of its middle-class readers than those further down the social scale. ‘Newspapers were, in a sense, free publicity for a town’s ruling classes’.43 Twenty hours after he woke up, Hewitson went to bed in the early hours of Saturday morning, not unusual on press day. As Hewitson slept, the printers worked through the night, to ensure that the first edition of the Saturday Preston Guardian came out before breakfast, ready for delivery by train and horse-drawn cart across its wide circulation area.

Fig. 4.3. Opening ceremony of the Preston Exhibition of Art and Industry in the Corn Exchange, 21 September 1865. Hewitson is probably at the reporters’ table, below the chairman’s table in front of the stage. Copyright Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library, Preston, England, all rights reserved.

Saturday 23 September 1865

Went to a most ridiculous meeting about Cattle Plague in afternoon at Bull Hotel. R C Richards of Kirkham wanted to be the propounder of some fine theory involving the raising of a fund of £5000. He failed & meeting ended in nothing.

Saturday was publishing day for the Preston Guardian’s main edition. That day’s paper, an 8-page broadsheet with 7 columns per page, sold for 2d. At 2,000 words a column, it contained approximately 112,000 words, about two-thirds the length of an average Victorian novel. Advertisements made up a quarter of the paper (14½ columns), Preston news almost a half (23 columns, although the proportion of local news was unusually high, including 17 columns about the town’s exhibition of art and industry). Hewitson probably wrote most of the exhibition report, more than 30,000 words, or more than a third of the paper’s editorial content.

Local and regional content was the single most significant type of material in papers like the Guardian. ‘Trumpery as it may seem to those uninterested in the district, the local news is the bone and muscle of a country paper’, claimed Frederick George Carrington, editor of the Gloucestershire Chronicle.44 A later commentator, T. Artemus Jones, agreed on the priority of local news: ‘The most piquant of parliamentary proceedings and the most gruesome of murders are condensed to find room for local matters’.45 And not just news: local advertisers worked hard to make their adverts attractive, such as J. S. Walker, the tailor, capitalising on interest in the exhibition with his strapline, ‘Preston exhibition of fashionable clothing’. Local Preston editorial and advertising accounted for between a third and a half of the paper in the 1860s, but there was plenty of national and international news and non-local, non-news material — the ‘localness’ of the local press was not a simple matter.

The remaining editorial matter consisted of six and a half columns of news from other parts of Lancashire, about five columns of UK and Irish news (including arrests of Fenians, crime, accidents, a ladies’ swimming race at Llandudno and ‘Mr Ruskin on servants’), two columns of foreign news, one and a quarter of business news and three columns of features. This non-news content, seen more often in provincial weeklies than London dailies, included history, births, marriages and deaths, train times and a column of ‘Varieties’. Here were jokes from Punch, facts about Baden-Baden extracted from Sir Lascelles Wraxall’s new book, Scraps and Sketches Gathered Together, and an anonymous poem, ‘September’, from Harper’s, an American magazine (in fact written by George Arnold [1834–65], an American poet). The same poem appeared in the Preston Herald a week later. As Bob Nicholson has established, American print culture, in the form of poetry, jokes and other material grew increasingly popular in Victorian Britain, half a century before Hollywood.46 The book extract and poem are also examples of a significant function of the local press, printing and reprinting literary material.47 The sheer number of local papers probably makes this the leading publishing platform for such material, ahead of books and magazines.48

Hewitson was not working towards a typical issue this week, instead focusing largely on the exhibition and the cattle plague, but then no newspaper issue is typical, because the balance of newspaper content reflects the news agenda of the time. The paper usually carried reviews of books and magazines, and literary extracts. There was no sport in this issue, but the following Wednesday’s paper devoted two thirds of a column to a cricket match between the gentlemen and players of Lancashire County Cricket Club, and the next Saturday edition (30 September) had three quarters of a column about a Blackpool race meeting. The Guardian’s main rival, the Tory Preston Herald, printed much of the same news, but there were differences: while one of the Guardian’s leading articles discusses a local topic, the exhibition, the Herald comments only on national and international politics — John Bright, and the French press’s attitude to Fenianism. The Herald had more church news, mainly Anglican, and a list of where army regiments were stationed, reflecting its support of both the established church and a strong army. There were other political differences, too — the following Saturday’s Preston Guardian devoted one column to the marriage of Lady Louisa Cavendish, daughter of a prominent Liberal family; this story received less coverage in the Tory Herald. In the same edition, both papers covered the revision of Preston voters’ lists and both made direct appeals to voters of their favoured party, to ensure their registration.

While Saturday’s paper was still on sale, Hewitson began reporting stories for the Wednesday edition. He attended a meeting about the cattle plague, which is reported soberly, objectively and verbatim across one and a half columns in Wednesday’s paper, but dismissed as ‘ridiculous’ in his diary. The Preston Guardian’s owner, George Toulmin, prided himself on such objectivity, particularly in party politics. Toulmin was an active Gladstonian Liberal, but was part-owner of a profitable Tory paper, the Bolton Chronicle, where he had learnt the commercial value of political balance in the 1850s. He later recalled how

previously […] the reports inserted were generally written out with a view to influence the political situation in the borough, especially as respects the length at which they were published, those meetings of the same politics as the paper being given at great length, while those held by the opposite party were rarely represented by more than a short travesty. The reforms which I effected in this department, combined with attention to all matters of local interest […] largely increased the circulation and influence of the paper, so that […] it became a valuable property.49

Toulmin applied this technique to the Preston Guardian, making the paper attractive even to readers who disagreed with its politics.50 Those politics were made clear in its leader and comment columns, less so in the selection and slant of its news. This openly commercial basis for objectivity contrasts with the rhetorical smokescreen of professionalism and balance seen in early-twentieth-century American journalism. Toulmin (like many other provincial publishers) had promoted objectivity on an avowedly political paper, funded by the Bolton Conservatives, before the liberalisation of the market, contradicting Jean Chalaby’s simple dichotomy of pre-1855 repeal ‘publicists’ and post-1855 journalists.51 Such balance is more important in smaller local markets than in metropolitan or later ‘national’ markets; the latter are large enough to be segmented profitably along political lines.

Sunday 24 September 1865

Sorted apples in forenoon; in afternoon went to Cemetery to see graves of my two dear children. At night read Watson’s evidences of Christianity.

In 1865 Hewitson was renting 48 Fishergate Hill, a modest terraced house ten minutes’ walk from the Preston Guardian office. He was probably earning more than the substantial £2 6s per week he was on in his previous job as ‘manager’ of the Preston Herald, and the following year he bought his house, making him one of only ten per cent of the population to own their own home.52 Hewitson was leaving behind his skilled working-class origins as a compositor (typesetter) and moving into the middle class.53 He probably earned more than most provincial reporters, and his relative wealth and respectability would have differentiated him from other less respectable reporters.

His daughters Madge and Ethelind had died, both aged three, in 1863 and in March 1865 respectively (Ethelind had died six months before this diary entry). Preston was the birthplace of all his children; three of their graves were in this town (another daughter, Ada, died in 1873 and was buried in the same grave); he was rooted here. He lived and worked in or near Preston, on and off, until his death, and he wrote about it as an insider. Charles Dickens may have been a better writer, but he wrote about Preston as an outsider.54 Hewitson’s emotional geography was centred on Preston, in contrast to the places he had passed through on his way up the professional ladder as a young compositor and reporter.

On Sundays Hewitson tended to read, and note in his diary, devotional books; this one was probably Richard Watson’s Theological Institutes: Or, A View of the Evidences, Doctrines, Morals, and Institutions of Christianity.55 There is some self-conscious parading of cultural capital here (there are hints in other entries that Hewitson hoped his diaries would be read, if not published), but he read many other books of theology, a legacy of his childhood schooling and theologically liberal mutual improvement classes in Lancaster. He had the confidence, and learning, to talk theology with priests and bishops, and his liberalism could be seen in his writing, particularly when he began to edit his own newspaper, the Preston Chronicle. In 1868 he was attacked for his defence of Roman Catholics, and he reported ‘heterodox’ Unitarian sermons.56 At this time, in 1865, he attended a Congregational chapel.57

Monday 25 September 1865

Went to Leyland with sister-in-law (Sarah Rodgett) & my child. Ran over our dog & got bitten when starting. Better luck further on. Attended a cattle plague meeting at Leyland; then had dinner; then went on in conveyance to Tarleton where there was a similar meeting. Very pleasant ‘out’ & hardly anything to do. Farmers are very obtuse & don’t talk much worth reporting. Got home about 8 o’cl[ock]& found dog mending. It had got part of its tail cut off and a bit of its leg foot or toe.

Hewitson mixed business and pleasure, presumably using the Preston Guardian’s horse and cart for his ‘out’ to the countryside south and west of Preston. He reported two meetings about the rinderpest outbreak that was devastating the whole country, with the reports appearing in Wednesday’s paper; his stories included verbatim quotes, while a report of another cattle plague meeting at Bretherton, a village in the same area, is only a summary without verbatim quotes, and probably supplied by a part-time local correspondent who had no shorthand.

‘Every village, however remote, has its newspaper representative in the person of the village schoolmaster, bookseller, shopkeeper, or barber.’58 These district correspondents collected news and advertising, in towns and villages on the periphery of their circulation area, while events at the core, where the newspaper was based, were covered by staff reporters.59 At mid-century the Manchester Guardian spent more on its district correspondents (Hewitson was one) than on its reporting staff, revealing their number and importance, and their value in gathering ‘original’ local news, for which readers were prepared to pay.60 In 1889 the Preston Guardian boasted that ‘the appointment of local correspondents in nearly every Town and Hamlet, keep the Guardian in the vanguard of Lancashire Newspapers […]’61 Half-way between readers and full-time reporters, these people were significant creators of newspaper content across the UK. Hewitson’s former teacher in Ingleton, Robert Danson, was one such node in the reporting network, acting as a debt collector and Ingleton district correspondent for the Lancaster Gazette. He was also the village postmaster, an ideal occupation for a district correspondent in search of local news and gossip. It may be that Danson inspired Hewitson to become a journalist, and facilitated his apprenticeship on the paper for which Danson was correspondent. In the 1830s and ‘40s Edwin Butterworth had been Oldham’s registrar for births and deaths whilst also serving as the town’s correspondent for Manchester newspapers, while Hartley Aspden entered a full-time journalism career after sending Clitheroe news to the Preston Guardian whilst working as a solicitor’s clerk.62 John Wilson, the Ambleside correspondent for the Kendal Mercury, earned around five shillings per column of ‘correspondence and literary matter’ in the 1880s and 1890s.63 Some part-time correspondents, particularly those from working-class backgrounds, went on to full-time journalistic careers, but most continued in other jobs. They were core members of the interpretive communities around each newspaper, although they might perform the same service for rival publications.64 Together they formed a local news network which connected with the national network of newspaper titles. Their snippets of news and gossip were pieced together by a sub-editor at the newspaper office to create a mosaic of detailed, intensely local news. Some traditional newspapers still retain district correspondents today.

Tuesday 26 September 1865

Paragraphing. Nothing extra. Weather warm. News slack.

By ‘paragraphing’, Hewitson means actively seeking out and recording original anecdote and gossip, ideally in witty and well turned phrases. The following Saturday’s paper includes one such ‘paragraph’ which could have been written by Hewitson, entitled ‘A FENIAN IN TROUBLE’. It tells of ‘a tradesman, a true type of John Bull’ discussing the Fenians in ‘a noted hostelry’ in Preston, when ‘one of the Emerald Isle’ spoke in support of the Fenians. The Irishman was knocked to the floor and left shortly afterwards.65 Paragraphing was a recognised journalistic skill, included in job adverts such as one in the Leeds Mercury of 28 January 1860:

TO REPORTERS — WANTED, on an Established Weekly Journal, a REPORTER qualified to take a verbatim note. He must also be a good paragraphist.

This ad from The Journalist of 30 March 1888 makes clear the gossipy element:

Gossip. — Experienced Journalist wishes to contribute a column or so of racy paragraphs to Provincial Papers […]

By the 1880s, ‘how-to’ books on journalism were devoting whole chapters to the art of paragraphing.66 Elsewhere in Hewitson’s diaries he describes paragraphing as ‘rambling about’ and ‘“boring” stupid people for news’.67 This active news-gathering contradicts Lucy Brown’s assertion that Victorian reporters were little more than stenographers, and crosses the professional boundaries of London journalism, which distinguished between journalists and mere reporters. A writer in the St James’s Magazine explained:

it is the leader-writer’s business to comment upon facts, the reporter’s to collect them; the one puts his own thoughts into type, the other simply takes down the thoughts of others.68

But the same article acknowledges that things are different ‘in the country’, where journalists were often required to do both.69 Paragraphs could also be supplied by non-journalists, or district correspondents such as Will Durham, a Blackburn Poor Law Guardian and innkeeper:

“Will.” Durham was not a regular staff reporter. He had no training for such duties. He was retained by the Preston Guardian as a paragraphist, correspondent, and contributor of original notes, in the Blackburn district, and this sort of work he could do in a readable style. He had the advantage of an accurate inkling of everything that was transpiring or about to happen.70

Wednesday 27 September 1865

Today went to Great Eccleston agricultural show in a conveyance. Had to pass Lea Road railway station where there had been a railway collision between an excursion train & a goods train. Twenty injured — some seriously. Just got to place in time to obtain particulars which I sent off to 14 newspapers. Afterwards went on to Eccleston Show — dull affair. Had dinner & paid for my own beer. Returned in evening & telegraphed half a column about accident to The Times.

Hewitson reported the train crash in great detail, obtaining the names of most of the injured, their place of origin and their injuries. Presumably he carried stationery with him, enabling him to make copies of his report and post them to the fourteen newspapers. The higher fees paid by the Times made it worthwhile to telegraph his report to them; it appeared on page nine as ‘Disastrous Railway Collision’ the following morning, and made half a column in Saturday’s Preston Guardian. Hewitson was North Lancashire correspondent for the Times, a district correspondent on the same model of core and periphery as district correspondents for local papers.

Using the digital British Newspaper Archive (BNA), we can track the train crash story as it spread around the country. Almost identical story structure and wording suggests that all the stories originated from Hewitson — he had an ‘exclusive’. Only a minority of newspapers are digitally available via the BNA, but we can still gain an impression of how news spread at this time. By Wednesday evening Hewitson’s posted reports should have reached their fourteen destinations (probably the provincial dailies mentioned elsewhere in his diaries for whom he acted as correspondent); this would explain the full reports in Thursday morning’s editions of the Manchester Guardian, Leeds Mercury, Liverpool Daily Post, Sheffield Daily Telegraph and Dundee Advertiser (the last two labelled as ‘From Our Correspondent’ and ‘From Our Preston Correspondent’ respectively). The reports in Thursday’s London morning papers, such as the Daily News and the Morning Post, and evening papers such as the Evening Standard and the Globe, were probably taken from the Times. The story was now public property and Hewitson would have earned no more money from it.

London-based freelance reporters may have summarised the Times story and telegraphed it to provincial papers on Thursday morning, and at least one London publisher of partly printed sheets or stereotyped pages (metal printing plates sent by train) included it in one of their pages; this page then appeared in smaller local newspapers (on Friday in the South Buckinghamshire Free Press ‘London supplement’, on Saturday in the Bury Free Press and the Kentish Independent, for example, Fig. 4.4). The Central Press news agency (established in 1863) probably took the story from Thursday’s Times and sent it to its client newspapers, including the Western Morning News (which carried the story in full on Friday). By Thursday afternoon the Times would have reached all parts of Britain and Ireland, enabling more remote papers to take the Times version, ready for Friday’s papers; some may have taken the story from their nearest provincial daily. The story appears in eight dailies and seven weeklies in the BNA on the Friday, and in more than forty BNA weeklies on Saturday, either in full, as a long summary including all names, or an abbreviated summary of twelve lines or so. It was carried in full in Sunday papers such as Reynolds’s Newspaper and Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, and was still appearing in some weeklies up to seven days after it happened, depending on their day of publication.

Fig. 4.4. Identical pages (either from partly printed sheets or page stereotypes) carrying Hewitson’s train crash story half-way down the second column, in three weekly newspapers, Kentish Independent (British Library NEWS2740), Bury Free Press (British Library NEWS4711) and South Bucks Free Press (MFM.M22733), Saturday 30 September 1865. © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

Provincial and metropolitan papers were part of the same systems and networks, originating, publishing and republishing news from around the UK and from overseas. In the mid-1860s news came from the staff of each paper, from London newspapers, but also from provincial newspapers and reporters around the UK, and — before international telegraph cables were laid beneath the oceans — from UK ports. News from America usually came via American newspapers carried on boats to Liverpool, from France and the Continent via ships docking at Dover and Portsmouth, and so on. Hewitson’s train crash story spread as an individual item, but stories were also collated and transmitted together: in newspapers themselves, which became sources of news for other papers; from the ‘intelligence departments’ (news departments) of the private telegraph companies, in partly printed sheets or stereotyped pages and columns, usually produced in London; and from news agencies such as Reuters (established in 1851) and Central Press.71

Paul Fyfe argues that Hewitson’s sale of the train crash story was no accident — in fact, he says, accidents were a popular type of news, because they symbolised the ‘paradoxes of urban modernity’ and appealed to a mid-Victorian sense that towns and cities were changing, no longer controllable or designable, before more modern ideas of probability and emergent systems. ‘Accident news brings into focus how the Victorian newspaper fashioned itself into a periodical encounter with uncertainty’, he believes.72 While Fyfe’s larger argument has merit, Hewitson’s story-mongering does not support it. He, and other provincial ‘stringers’ (retained freelance correspondents) for metropolitan papers, sold all types of stories, not just accidents — besides the staple of crime, political speeches were particularly lucrative, whilst five days earlier, Hewitson had sold a two-column report of the Preston Exhibition of Works of Art and Industry to the Times.73 As Fyfe acknowledges, uncertainty, chance and the unexpected had always been the stock in trade of the newspaper.74

Hewitson’s use of the telegraph to send his story to the Times demonstrates how this recent technology was used to move news from where it originated to a central processing point (newspapers or news agencies). From that centre, it was broadcast out again to newspapers like the Preston Guardian (which published telegraphic news from Reuters and the British and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company), and directly to news rooms and reading rooms, such as the Exchange news room in Preston, where a telegraph machine was installed for members.75

Before Hewitson left the office that morning, he would already have skimmed through Wednesday’s Preston Guardian. The mid-week edition was only four pages in 1865, half the size of the Saturday edition. That day’s paper included general news from around the UK, with two-and-a-half columns on the arrest of Fenians in Liverpool, news of the cattle plague, and foreign news (mainly from America, where the civil war had ended four months earlier, in May 1865), as well as suicides, elopements, and murders, much of this news taken from other papers. Local news focused on Preston’s exhibition of art and industry, the cattle plague, accidents, court cases, speeches given at dinners, and a report of a meeting of the Board of Guardians (administrators of the Poor Law and the workhouse), a cricket match report and cricket results. There were short sections of news from surrounding towns and villages such as Blackburn, Clitheroe, Burnley, Ulverston and the Lakes; market and trade reports; and letters from readers. Besides news from provincial and London papers, this edition reprinted gardening notes from the Gardener’s Chronicle, a review of the corn trade from the Mark Lane Express (a farming newspaper named after the address of London’s corn exchange) and what would now be called a news backgrounder on anti-colonial resistance in New Zealand, ‘How the Maories were supplied with ammunition’ from the Hawkes Bay Times, New Zealand. Advertising accounted for one third of the paper.

As usual, the paper’s ‘Manchester Trade Report’ on the prices of cotton and other commodities was labelled ‘From our own Correspondent’. This is an example of another type of non-journalistic contributor, the specialist or expert. The Lancaster Guardian, for example, could call on Mr Housman of Skerton who was ‘a leading authority’ on shorthorn cattle, or two brothers, Dr James and Mr Christopher Johnson, the former an expert on ‘the suitability of various manures for particular soils’ the latter a specialist ‘on scientific and professional subjects’.76 It was not unusual for leader columns to be written by individuals other than the editor and, although Hewitson probably wrote most of the Chronicle’s, on at least one occasion he used two by William Livesey on the game laws and Plimsoll’s ship safety recommendations, and some leaders in the Conservative Preston Herald were probably written by the vicar of Preston in the late 1860s.77 The Congregational ministers Rev W. Hope Davison and Rev John Mills wrote leaders for the Bolton Evening News and the Staffordshire Sentinel respectively, and the sermons of the Bishop of Liverpool, Alexander Goss (after he had proof-read and augmented them) occasionally served as leaders in the Catholic Times.78

Hewitson’s one-and-a-half-column report of the Great Eccleston agricultural show and dinner in the following Saturday’s paper would enable scores of participants to read about what they already knew, that they had won a prize or been highly commended in one competition class or another. The whole report includes more than sixty names, all of whom would be proud to read of their successes. Small achievements were celebrated, lives were recorded, and distinctive local identities were evoked by the list of competition categories, revealing local farming practices, climatic conditions, customs, crafts such as the creation of ’ropes’ of onions, and food cultures such as oatcakes.

Thursday 28 September 1865

To Town Council meeting at 11 o’cl[ock]. Nothing transpired of any moment. In afternoon gave an order for 2600 envelopes to be printed — for newspapers, also a circular head. Aft[erwar]ds got particulars of 16 cows being seized in cattle plague. Wrote it out for 20 papers. In evening went to distribution of prizes at Preston School of Science.

The council meeting made one-fifth of a column in the following Saturday’s paper, the prize-giving one column, again full of names — the commodity that local papers sold back to the bearers of the names, immortalised in Times 8pt type.

Hewitson’s stationery order was probably for his sideline as a ‘moonlighting’ correspondent for other newspapers, prompted by the success of his train crash story the day before. From the publisher’s point of view, ‘stringers’ such as Hewitson were expensive, so they were always looking for other ways to gather and publish news as cheaply and as profitably as possible. Partly printed sheets and telegraphic news agencies are two examples, but there were others. William Saunders, owner of the Central Press news agency, also owned daily newspapers around the UK, and used some of the same material — including leading articles — in all his papers.79 Some regional publishers set up series of local titles, such as Alexander Mackie’s Warrington Guardian series of seven papers, established in the 1850s or W. E. Baxter’s Sussex Agricultural Express series (twenty-four titles by 1870). Titles usually shared some content between them, and produced their own unique local news in addition. In Preston, the Toulmins developed a minor empire of Lancashire newspapers, and the rival Preston Herald was linked to the Blackburn Standard, sharing material and personnel. These non-local connections were usually played down, because localism was a selling point.

More ambitious publishers experimented with national publishing structures, raising intriguing questions over whether they were producing national or local media, or more likely a hybrid, as with local newspapers using partly printed sheets. Publishers of Anglican parish magazines used the same model, selling national insets, which were supplemented by local parishes to create ‘local’ publications.80 In the early 1880s, the Carnegie-Storey syndicate of American millionaire Andrew Carnegie and Radical Sunderland MP Samuel Storey was a loose, decentralised group of radical halfpenny papers aimed at working-class readers, sharing some material, but also producing their own unique local content.81 Charles Diamond used similar methods, with his Catholic Herald series, launched in 1888. It was headquartered in London, and shared some content with dozens of local editions (forty-two separate titles across England and Scotland by his death in 1934), each with some unique local material — ‘a national publishing structure based on local variation’.82 The most successful experiment was Alfred Harmsworth’s simultaneous publication of the Daily Mail in London and (from 1900) Manchester. But was the northern edition of the Mail a national or regional newspaper? Perhaps it was a combination of the two, as suggested by this boast from 1912, describing how the paper publishes

from its offices in London and Manchester no fewer than eight separate and distinct local editions, each of which contains the complete London edition with two pages of additional local news — eight separate local newspapers, in fact, which are supplied to our readers in the various districts for the price charged for the London Daily Mail.83

The publishers of the Mail clearly believed that the paper became more national by becoming more local. Complex publishing structures lay behind the misleadingly simple idea of a ‘local newspaper’.

This week in the life of a provincial reporter of the 1860s reveals many aspects of the Victorian newspaper press. Every local paper was part of national networks (decentred, distributed) and national systems (usually but not always centred on London), through their changing personnel, the personal, business and political networks of their proprietors, and the methods by which they gathered and distributed editorial and advertising material. London and provincial newspapers were part of the same systems and networks. The occupation of reporter was becoming increasingly important, but a significant proportion of editorial content was produced by non-journalists, such as part-time district correspondents and local experts. They, and many other local newspaper personnel, had a stake in their locality and produced material that celebrated the deeply meaningful banality of local life. There were hundreds of local papers, churning out thousands of pages, full of tens of thousands of editorial items, every day. How these many different journalistic and literary genres, such as the paragraph or the market report, were created, and how they moved about the country — and the world — reveals the complexity of this borderland between the creative and the industrial. This eco-system, comprising many species of papers and magazines, was constantly evolving. The next chapter, based on another week from Hewitson’s diaries, in 1884, shows how quickly this occurred.

1 ‘Reporting and Reporters’, Printers’ Register, 6 April 1870, p. 80.

2 Anthony Hewitson, ‘Recollections of earlier life’, Lancashire Archives DP512/2; brief family history and autobiography at end of 1873 diary, DP512/1/6. These are referred to as the Hewitson Diaries hereafter.

3 Compositor and reporter, Kendal Mercury, July-August 1857 (Hewitson, ‘Recollections’; Hewitson Diaries 1873); compositor, reporter and editor, Brierley Hill Advertiser, September?–November? 1857; compositor, reporter and editor, Wolverhampton Spirit of the Times, December 1857?–May 1858 (Hewitson Diaries 1873, back pages); compositor and reporter, Preston Guardian May? 1858-late 1858. A contemporary, Harry Findlater Bussey, worked on sixteen papers in twelve towns between 1844 and 1858, from Carlisle to Plymouth: H. F. Bussey, Sixty Years of Journalism: Anecdotes and Reminiscences (Bristol: J. W. Arrowsmith, 1906).

4 Atticus was a celebrated Roman editor, banker and patron of literature, and the best friend of the orator and philosopher Cicero.

5 The 1881 figures have been checked, and are probably an error in the original. Sources: 1851 Census (1852–53, 1691 [parts 1 & 2]); 1861 Census (1863, 3221); 1871 Census (1873, C.872); 1881 Census (1883, C.3722); 1891 Census (1893–94, C.7058); 1901 Census (1904, Cd. 2174).

6 For a more detailed comparison of the Times and other newspapers, see Andrew Hobbs, ‘The Deleterious Dominance of The Times in Nineteenth-Century Scholarship’, Journal of Victorian Culture 18 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1080/13555502.2013.854519

7 Anon., ‘The Modern Newspaper’, British Quarterly Review, 110 (1872), 348–80 (p. 371).

8 H. R. Fox Bourne, English Newspapers: Chapters in the History of Journalism, Vol. II (London: Routledge/Thoemmes Press, 1887); Virginia Berridge, ‘Popular Sunday Newspapers and Mid-Victorian Society’, in Newspaper History from the Seventeenth Century to the Present Day, ed. David George Boyce et al. (London: Constable, 1978), pp. 247–64.

9 Berridge; Laurel Brake and Mark W. Turner, ‘Rebranding the News of the World: 1856–90’, in The News of the World and the British Press, 1843–2011, ed. Laurel Brake, Chandrika Kaul, and Mark W. Turner (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 27–42, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137392053_3

10 Maurice Milne, The Newspapers of Northumberland and Durham: A Study of Their Progress during the ‘Golden Age’ of the Provincial Press (Newcastle upon Tyne: Graham, 1971), p. 19.

11 Arnot Reid, ‘How a Provincial Paper Is Managed’, Nineteenth Century 20 (1886), p. 391.

12 Printers’ Register supplement, 6 August 1870, p. 169.

13 Graham Law, ‘Weekly News Miscellany’, in Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism (DNCJ), ed. Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor, online, C19: The Nineteenth Century Index (ProQuest).

14 Commissioned by Tillotsons, the manuscript was rejected on grounds of taste.

15 F. David Roberts, ‘Still More Early Victorian Newspaper Editors’, Victorian Periodicals Newsletter, 18 (1972), 12–26.

16 Martin Hewitt, The Dawn of the Cheap Press in Victorian Britain: The End of the ‘Taxes on Knowledge’, 1849–1869 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), p. 23.

17 For more details see Andrew Hobbs, ‘Provincial Periodicals’, in The Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, ed. by Andrew King, Alexis Easley, and John Morton (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), pp. 221–33, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613345; Hobbs, ‘Deleterious Dominance’.

18 Hewitt, p. 14.

19 Simon Eliot, Some Patterns and Trends in British Publishing, 1800–1919 (London: Bibliographical Society, 1994), p. 83.

20 Laurel Brake, ‘Markets, Genres, Iterations’, in Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, pp. 237–48 (p. 242).

21 Simon Gunn, The Public Culture of the Victorian Middle Class: Ritual and Authority in the English Industrial City, 1840–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000); Patrick Joyce, The Rule of Freedom: Liberalism and the Modern City (London: Verso, 2003).

22 Sources: British Library catalogue, John S. North, ed., The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals, 1800–1900 (North Waterloo Academic Press); Anthony Hewitson, History of Preston (Wakefield: S. R. Publishers [first published 1883], 1969), pp. 341–44.

23 Fiona J. Stafford, Local Attachments: The Province of Poetry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 295–96.

24 1854–55 (83) ‘Return of Number of Stamps issued at One Penny to Newspapers’. These government newspaper taxation statistics have been used to characterise Preston’s press at the start of the period despite their limitations, noted in H. Whorlow, The Provincial Newspaper Society. 1836–1886. A Jubilee Retrospect (London: Page, Pratt & Co., 1886), p. 12; Aled Gruffydd Jones, Press, Politics and Society: A History of Journalism in Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1993), p. 90; Alfred Powell Wadsworth, ‘Newspaper Circulations, 1800–1954’, Transactions of the Manchester Statistical Society, 9 (1955), 1–40 (p. 33). They can provide a rough guide to aggregate copies printed (not sold), and comparative circulations of different papers. For a more sceptical view, see Marie-Louise Legg, Newspapers and Nationalism: The Irish Provincial Press, 1850–1892 (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1999), p. 30.

25 ‘Grandmamma’s Arithmetic’, Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC), 27 November 1847. Note the local reference to the River Ribble.

26 Ian Levitt, ed., Joseph Livesey of Preston: Business, Temperance and Moral Reform (Preston: University of Central Lancashire, 1996); Andrew Hobbs, ‘Preston Guardian’, in DNCJ online.

27 Letter from Anthony Hewitson, Preston Guardian (hereafter PG), 8 June 1912, pasted into back of Hewitson Diary 1912; PG, 14 December 1872, p. 6.

28 Jubilee supplement, PG, 17 February 1894.

29 PG, 20 October 1860.

30 For Langley, PC, 4 August 1861; 31 January 1863; for Reid, Stuart Johnson Reid, Memoirs of Sir Wemyss Reid, 1842–1885 (London: Cassell, 1905).

31 I am grateful to Ian Kenneally for this information. See Ian Kenneally, From the Earth, A Cry: The Story of John Boyle O’Reilly (Cork: Collins Press, 2011).

32 Leading article, PG, 24 October 1868; obituary of Preston Herald company chairman Miles Myres, PG, 17 December 1873.

33 Charles Hardwick, History of the Borough of Preston and Its Environs, in the County of Lancaster (Preston: Worthington, 1857), p. 456; Andrew Hobbs, ‘Partly Printed Sheets’, in DNCJ online. Larger provincial publishers also produced partly printed sheets, such as the Toulmins, publishers of the Preston Guardian. From 1871 to 1876 they sold 1,000 partly printed copies per week of their Blackburn Times, with pages 3 and 4 printed and pages 1 and 2 blank, to a Colne printer, E. J. Taylor. Taylor filled the blank pages with Colne news and advertisements, and sold it as the Colne and Nelson Guardian (‘County Court’, Blackburn Standard, 18 August 1877).

34 Obituary of Miles Myres, Preston Herald (hereafter PH), 17 December 1873, p. 3.

35 Benjamin Disraeli, Benjamin Disraeli Letters 1848–51, ed. J. B. Conacher and M. G. Wiebe, vol. V (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), p. 357, letter 2046, note 1.

36 Mitchell’s Newspaper Press Directory, 1861; Jitendra Nath Basu, Romance of Indian Journalism (Calcutta: Calcutta University, 1979), p. 155. Basu says that Laman Blanchard returned to England in 1864, three years after Mitchell’s directory names him as Preston Herald editor. He became a barrister in 1866 and returned to Indian journalism from 1873 to 1880. A frequent contributor to London periodicals, he was credited with the quip ‘Let us start a comic Punch’: Times, 7 June 1866; Dyke Rhode, ‘Round the London Press, XI. Turveydrop and Weller in Type’, New Century Review, January 1899.

37 Colin Buckley, ‘The Search for “a Really Smart Sheet”: The Conservative Evening Newspaper Project in Edwardian Manchester’, Manchester Region History Review, 8 (1994), 21–28.

38 For more detailed histories of Preston’s newspapers and magazines, see Andrew Hobbs, ‘Reading the Local Paper: Social and Cultural Functions of the Local Press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855–1900’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Central Lancashire, 2010); for temperance periodicals, see Annemarie McAllister, ‘Temperance Periodicals’, in Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, pp. 342–54.

39 M. Milne, ‘Survival of the Fittest? Sunderland Newspapers in the Nineteenth Century’, in The Victorian Periodical Press: Samplings and Soundings, ed. J. Shattock and M. Wolff (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1982), 214–17.

40 Hewitson Diary 1865, Lancashire Archives DP512/1/1.

41 ‘Preston Art And Industrial Exhibition’, Times 22 September 1865, p. 10; an image can be seen in the Illustrated London News, 14 October 1865, p. 365.

42 Nancy P. Lopatin, ‘Refining the Limits of Political Reporting: The Provincial Press, Political Unions, and The Great Reform Act’, Victorian Periodicals Newsletter, 31 (1998), 337–55 (p. 340); Donald Read, ‘John Harland, Father of Provincial Reporting’, Manchester Review, 8 (1958), 205–12 (p. 211).

43 Peter Brett, ‘Early Nineteenth-Century Reform Newspapers in the Provinces: The Newcastle Chronicle and Bristol Mercury’, in Studies in Newspaper and Periodical History: 1995 Annual, ed. by Tom O’Malley and Michael Harris (London: Greenwood, 1997), p. 51.

44 Frederic Carrington, ‘Country Newspapers and Their Editors’, New Monthly Magazine 105 (1855), 147.

45 Artemus T. Jones, ‘Our Network of News: The Press Association and Reuter’, Windsor Magazine, July 1896, p. 521, British Periodicals.

46 Bob Nicholson, ‘Looming Large: America and the Late-Victorian Press, 1865–1902’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, Manchester University, 2012).

47 Such extracts, from fiction and non-fiction, were sometimes made by publishers themselves, such as Cassell and Longman, and inserted into their own partly-printed newspapers, for provincial publication. Publishers and authors saw extracting as free advertising, raising doubts over Mary Hammond’s metaphors of piracy and abducted orphans for such material: Mary Hammond, ‘Wayward Orphans and Lonesome Places: The Regional Reception of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton and North and South’, Victorian Studies, 60 (2018), 390–411.

48 Andrew Hobbs and Claire Januszewski, ‘How Local Newspapers Came to Dominate Victorian Poetry Publishing’, Victorian Poetry, 52 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1353/vp.2014.0008

49 ‘Seventieth birthday of Councillor Toulmin JP — presentation’, PG, 5 January 1884, p. 11.

50 Printers’ Register, 6 February 1873, p. 474. For the view that Liberal papers were more balanced, see Aled Gruffydd Jones, Powers of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth-Century England (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996), p. 146; Buckley, p. 22.

51 Michael Schudson, ‘The Objectivity Norm in American Journalism’, Journalism 2 (2001), 149–70, https://doi.org/10.1177/146488490100200201. For a differing view on the history of objectivity, see Jean Chalaby, The Invention of Journalism (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998), p. 13; Stuart Allan, ‘News and the Public Sphere: Towards a History of Objectivity and Impartiality’, in A Journalism Reader, ed. by Michael Bromley and Tom O’Malley (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. 296–329.

52 Stephen Merrett and Fred Gray, Owner Occupation in Britain (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982), p. 1.

53 However, the craft of compositor was seen as a literary job, part of a ‘labour aristocracy’, and apprenticeships required parents to pay a substantial bond to the employer: Patrick Duffy, The Skilled Compositor, 1850–1914: An Aristocrat Among Working Men (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), pp. 121, 53, 54.

54 Charles Dickens, ‘On strike’, Household Words, 11 February 1854, pp. 553–59. Hard Times was inspired by the lock-out (not a strike), but Coketown is not Preston.

55 An eighth edition was published by Mason in 1864.

56 Hewitson diary, 11 April 1875.

57 For the links between provincial newspapers and Nonconformity, see Simon Goldsworthy, ‘English Nonconconformity and the Pioneering of the Modern Newspaper Campaign’, Journalism Studies 7 (2006), 387–402, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700600680690

58 Alfred Arthur Reade, Literary Success: Being a Guide to Practical Journalism, 2d ed. (London: Wyman & Sons, 1855), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100571156

59 The most detailed analysis of this neglected journalistic figure is Michael Winstanley, ‘News from Oldham: Edwin Butterworth and the Manchester Press, 1829–1848’, Manchester Region History Review 4 (1990), 3–10.

60 In the first half of 1856 ‘District & Provincial reporting’ cost £514 1s, while reporters’ salaries totalled £422 8s 2d (‘Summary of expenses for the year ending 30 June’, 1856, TS in box of miscellaneous notes on history of Manchester Guardian, ref: 324/5A, Manchester Guardian archive, Manchester University.

61 Advertisement, Sell’s Dictionary of the Press 1889, p. 1206.

62 Winstanley, ‘News from Oldham’; Hartley Aspden, Fifty Years a Journalist. Reflections and Recollections of an Old Clitheronian (Clitheroe: Advertiser & Times, 1930), pp. 7, 8.

63 Lancaster Observer, 3 March 1893, p. 6.

64 The village correspondent for Audlem in Cheshire acted for five weeklies in the late twentieth century: Geoffrey Nulty, Guardian Country 1853–1978: Being the Story of the First 125 Years of Cheshire County Newspapers Limited (Warrington: Cheshire County Newspapers Ltd, 1978), p. 56.

65 PG, 30 September 1865, p. 5.

66 Reade, Literary Success, ch. IV, ‘On Paragraph-Writing’; John Dawson, Practical Journalism, How to Enter Thereon and Succeed. A Manual for Beginners and Amateurs (London: Upton Gill, 1885), ch. 2, ‘Paragraph-writing and reporting’. I am grateful to Dr Steve Tate for information on paragraphing.

67 Hewitson Diaries, 9 August 1865; 29 November 1866, for example. See also Bussey, pp. 73, 179–80; Carrington, p. 148.

68 Lucy Brown, Victorian News and Newspapers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), p. 103; Hewitson also reported many sermons, contra Brown, pp. 99–100; ‘Gentlemen of the Press. IV. The Reporter’, St. James’s Magazine, February 1882, 173–79, British Periodicals.

69 ‘Gentlemen of the Press. IV. The Reporter’, 174.

70 William Alexander Abram, Blackburn Characters of a Past Generation (Blackburn: Toulmin, 1894), p. 322.

71 For the Central Press, see Andrew Hobbs, ‘William Saunders and the Industrial Supply of News in the Late Nineteenth Century’, in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, vol. 2: Expansion and Evolution, 1800–1900, ed. by David Finkelstein (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

72 Paul Fyfe, By Accident or Design: Writing the Victorian Metropolis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 33, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198732334.001.0001

73 For the trade in reports of speeches, see H. C. G. Matthew, ‘Gladstone, Rhetoric and Politics’, in Gladstone, ed. Peter John Jagger (London: Hambledon, 1998); Hewitson diaries, 22 September 1865.

74 Fyfe’s discussion of the ‘Accidents and Offences’ column (p. 44) is based on the small minority of weekly London newspapers, ignoring London dailies and the majority of the press published in the provinces. A quick search of the rare instances of such columns in provincial papers between 1830 and 1870 finds that they were dominated by distinctly unmodern stories, often from rural areas, of drownings, suicides, domestic fires, and people falling off horses and horse-drawn vehicles; only three of the thirty-one stories were rail accidents.

75 The use of telegraphs for sending news to newspapers was an afterthought by the private telegraph companies, who had hoped to make money from transmitting news directly to ‘telegraphic news rooms’ — so much for technological determinism: Roger Neil Barton, ‘New Media: The Birth of Telegraphic News in Britain 1847–1868’, Media History 16 (2010), 379–406, https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2010.507475

76 The Lancaster Guardian. History of the Paper, And Reminiscences by ‘Old Hands’, Published in Connection with Its Diamond Jubilee (Lancaster: E & J Milner, 1897), Lancaster Library, pp. 27–28.

77 Hewitson Diaries, 7 and 8 March 1873; Frank Singleton, Tillotsons, 1850–1950: Centenary of a Family Business (Bolton: Tillotson, 1950), p. 9; Rendezvous with the Past: One Hundred Years’ History of North Staffordshire and the Surrounding Area, as Reflected in the Columns of the Sentinel, Which Was Founded on January 7th, 1854 (Stoke-on-Trent: Staffordshire Sentinel Newspapers, 1954), pp. 14–15; John Denvir, The Life Story of an Old Rebel (Shannon: Irish University Press, 1972), pp. 157–58.

78 ‘The Irish Church’, letter from ‘A Looker-On’, PC, 23 May 1868.

79 Hobbs, ‘William Saunders’.

80 Jane Platt, Subscribing to Faith? The Anglican Parish Magazine 1859–1929 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137362445

81 Andrew Hobbs, ‘Carnegie-Storey Syndicate’, in DNCJ online.

82 A. Hilliard Atteridge, ‘Catholic Periodical Literature’, Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 11 (New York: Robert Appleton, 1911); Joan Allen, ‘Diamond, Charles’, in DNCJ online.

83 Daily Mail promotional article, 13 May 1912, cited in Robert Waterhouse, The Other Fleet Street: How Manchester Made Newspapers National (Altrincham: First Edition, 2004), pp. 27–28.