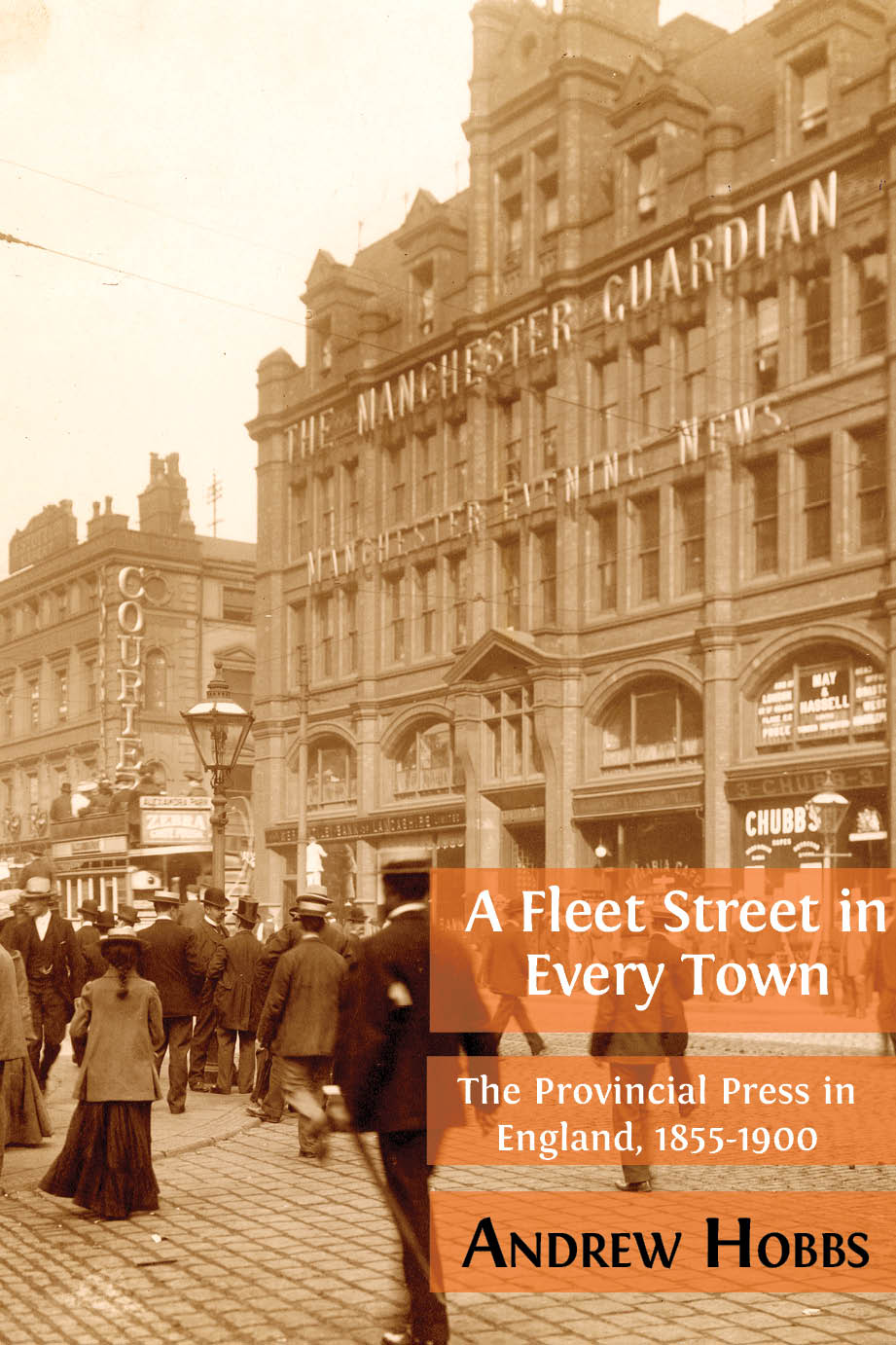

5. What They Read: The Production of the Local Press in the 1880s

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.05

In 1867 Preston newspaper reporter Anthony Hewitson was sacked from his job as chief reporter on the Preston Guardian, possibly because his employer, George Toulmin, wrongly believed that Hewitson was planning a rival paper.1 The following year he bought the Preston Chronicle, running this smaller Liberal newspaper from 1868 to 1890. Another week of diary entries, from 1884, introduces further aspects of the provincial press, and reveals how journalism, including provincial journalism, was changing. Some of those changes require some background first.

Changes, 1865–84

Hewitson’s diary entry for 23 March 1868 reads: ‘Started as proprietor of the Preston Chronicle today. How will matters end? I am anxious.’ However, he made a success of it. His diary describes how he made the paper more profitable, invested in property, rented larger houses, employed more servants and began to enjoy foreign holidays. In 1872 the paper was making £12 profit per week, and by the following year it may have had the highest sale in Preston itself (while its two larger competitors, the Herald and the Guardian, probably sold more in other parts of their wider circulation areas).2 He bought the Chronicle by instalments over five years; the initial capital probably came from his freelance earnings, savings from his salary and possibly an inheritance.3

As an owner-editor, Hewitson made three important decisions, which differentiated him and his paper from his rivals. First, he made the Chronicle more local and Preston-focused; second, he performed local identity in print, making the paper more personal in its writing style and subject matter; and third, he performed local identity in person by taking an active and very visible part in the commercial, cultural and political life of Preston. The concept of performing local identity is used in two ways here: first, in print, the style and content of Hewitson’s writing was more local, and was intended to identify his paper and himself as committed to Preston; second, he made a virtue of his business and his residence in the town centre and his involvement in local life, presenting himself personally as at the heart of local affairs. He greatly increased the amount of local content in the Chronicle as soon as he bought the paper, differentiating himself from the Preston Guardian’s wider geographical coverage. Local advertising increased, and the leader columns — traditionally on national topics, even in the local press — became locally focused. Hewitson sustained this localism throughout the 1870s, but after that the Chronicle’s coverage became less distinctive, although it retained Hewitson’s more personal tone of voice. By 1880 the Chronicle’s Preston coverage had declined to levels below those before he bought it; and the columns of district news from outlying towns and villages, which had been fewer in the first decade under Hewitson, now outnumbered those for Preston.4

Hewitson, born in Blackburn, ten miles from Preston, became the first non-native to own a significant Preston paper. Previously, papers had been handed on to sons or former apprentices, but the economy of the provincial press was changing. Before, the publishers of most of Preston’s newspapers had been local men, closely connected with one another. All but one of Preston’s main titles (with the exception of the Herald) could trace their lineage to one printer, Thomas Walker (d. 1812), who had unusual abilities as a trainer of newspapermen, numbering among his apprentices future proprietors Edward Baines of the Leeds Mercury, Thomas Rogerson of the Liverpool Mercury and Thomas Thompson of the Leicester Chronicle. Other Walker apprentices launched the Preston Journal (which became the Preston Chronicle when it was sold to another of his protégés, Isaac Wilcockson), and the Preston Pilot. Thomas Walker’s son John trained George Toulmin, who later bought the Preston Guardian, the town’s most successful newspaper.5 Most papers were started by printers, with Joseph Livesey, a cheesemonger, the only exception. When papers were sold, they were usually sold to other printers, or to men who had begun their careers as printers — and usually to a purchaser well known to the seller. Most Preston printers associated with newspapers were Liberal, with the Clarkes and their Pilot the exception. Many wrote and published works of local history, and in Preston and elsewhere, some printers showed their local patriotism by giving their technical inventions local names, such as Bond’s ‘Prestonian’ web printing machine, Soulby’s ‘Ulverstonian’ machine and the ‘Wharfedale’ press, invented in that valley in Otley in 1858.6

As well as their connections to each other, many of Preston’s printers were also involved in a wider local print culture, involving news publishing, news retailing, libraries and news rooms. Livesey set up reading rooms, while his successor, George Toulmin, was active in establishing the Reform Union reading room. In neighbouring Blackburn, the town’s first librarian, William Abram, resigned after five years in 1867 to become editor of the Blackburn Times (owned by the Toulmins, publishers of the Preston Guardian). He became a councillor, a member of the library committee and then its chairman.7 Publishers gave copies of newspapers and books to libraries and reading rooms, perhaps partly out of commercial considerations, but also from a belief in the power of the press, and perhaps an emotional attachment to print. Among those who gave books to the free library in Preston town hall between 1879 and 1881 were William Dobson (local historian and former owner of the Preston Chronicle), Hewitson (owner of the Chronicle), Livesey, Toulmin and the librarian himself.8 Liberal newspapermen appeared to give greater support than their Conservative colleagues, although all the local papers were in favour of a free library.9

The year 1870, two years after Hewitson took over the Chronicle, was momentous for British journalism. The nationalisation of the private telegraph companies, ‘the first major government purchase of private enterprise in modern British history’, was structured in a way that favoured provincial newspapers over metropolitan ones.10 It came fifteen years after the abolition of cheap postal distribution, which disproportionately affected the provincial circulation of London papers, and Jonathan Silberstein-Loeb believes that this rigging of the market accounts for the success of the provincial press in the second half of the nineteenth century. However, provincial circulations were growing before 1870, and later chapters will argue that readers’ desire to see their lives validated in print was also part of local papers’ success.

Lobbying by newspaper proprietors about the expense and inefficiency of the private telegraph companies led to their nationalisation, which came into effect in 1870. Cheap telegraphed news benefited the provincial press more than the London press, because they had greater need of the material to supplement the little news gathered by their smaller staffs, and were far from Parliament and other centralised news sources. Provincial publishers, acting through their trade body, the Provincial Newspaper Society, were also more dynamic in seizing the legal and commercial opportunities of nationalisation by creating their own co-operatively owned news agency, the Press Association. PA, as it became known, charged higher prices to London papers, and struck a deal with Reuters for cheap foreign news. It went into operation within days of the nationalisation of the telegraphs.11

By lucky coincidence (from a journalistic point of view), the Franco-Prussian War broke out in July 1870, a few months after PA’s launch. Interest in the war, and fear of invasion, created a huge demand for foreign news, which local papers could supply cheaply thanks to the Reuters deal. A new type of publication, the provincial evening newspaper, came into its own. Now many more provincial evenings were launched, full of the latest telegrams from the continent. Looking back from 1900, one commentator argued:

The Franco-Prussian war may be said to have begotten the evening newspaper in England. Many of the best-established and most flourishing newspapers in England and Scotland at the present day […] had their origin in miserable little productions which were published in order that an impatient public might have the earliest news of the fate of the French and German forces.12

In 1870 nine new evening papers were launched in Lancashire alone — two of them in Preston, one by Hewitson and one by his former employer, George Toulmin. Thus began a brief but rancorous newspaper war between the two Preston Liberal newspaper publishers. On 25 July 1870, a week after war was declared, Hewitson launched the Preston Evening Express and, on the other side of Fishergate, Toulmin launched the Preston Evening News, both priced at a halfpenny. Hewitson had moved first, but Toulmin was ruthless in protecting his market (by 1870 the Toulmins dominated North Lancashire, with the Preston Guardian, Blackburn Times, Accrington Reporter and the Warrington Examiner series, and George Toulmin still managed the Bolton Chronicle). Two weeks later Toulmin increased the pressure by launching a morning paper, the penny Preston Daily Guardian. Two weeks after that, Hewitson admitted defeat and closed his Evening Express. Toulmin’s deeper pockets had ensured victory.13 The threat gone, Toulmin closed his new morning and evening papers soon afterwards.14 Across the country, however, the number of provincial evenings grew from thirteen in 1870 to sixty-eight in 1880.15

Hewitson was both owner and editor of his newspaper. In contrast, the Toulmins employed editors for their papers, an increasingly common approach as more capital, and management ability, was required to buy and run a paper. The number of newspaper chains such as the Toulmins’ grew, as owners sought economies of scale. Table 5.1 below uses the presidents of the Provincial Newspaper Society as a sample of proprietors, and reveals a steep decline in the proportion who edited their own papers.

Table 5.1. Owner-editors as a proportion of Provincial Newspaper Society presidents, 1836–8616

|

Years |

% |

|

1836–39 |

75 |

|

1840–49 |

20 |

|

1850–59 |

60 |

|

1860–69 |

30 |

|

20 |

|

|

1880–86 |

28.6 |

Sales of all types of newspaper grew, but the increase was greater for provincial titles than metropolitan ones. Innovations in London distribution such as slightly earlier ‘newspaper trains’ (see Fig. 5.1) from the capital in the 1870s had little impact. These trains, carrying early editions of morning papers, captured the imagination of metropolitan writers, who saw it as a symbol of the influence of London newspapers:

.jpg)

Fig. 5.1. ‘Notes in an early newspaper train’, The Graphic, 15 May 1875, p. 472, showing the national distribution of London newspapers by special trains. British Library, HS.74/1099. © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

that centrifugal action by which London flings abroad the tidings and thoughts which had reached it since [the reader] last went to bed. The newspaper trains start at five o’clock for their daily sowing of the land with type, handfuls of which are hurled out at stations far and near […]17

However, there is little evidence that these newspaper trains increased sales of London dailies in provincial markets served by locally published dailies.

One of the most successful newspaper formats by the 1880s was the regional news miscellany, which spread around the country, out-selling Sunday newspapers within their regional territories. In 1873 the various editions of the Dundee People’s Journal were selling 125,000 copies per week; the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle sold 45,000 in 1875, and the Manchester Weekly Times sold 60,000 by 1884.18 For comparison, by 1886 the Sunday newspapers Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper sold 612,000 and Reynolds’s sold 300,000, across the whole country. The success of the weekly news miscellanies, and their ‘literary supplements’, full of magazine-style material, influenced traditional local and regional weeklies like the Preston Guardian and Preston Herald, which introduced ‘literary supplements’ in the 1870s, while the main body of the paper continued to provide more sober news from North Lancashire and further afield. Preston’s most popular paper was the Preston Guardian, selling 15,500 in 1870 and 20,000 in 1887.19 Hewitson’s Chronicle probably sold less than half these figures.

Nationally, magazines were growing in popularity, from 480 titles in 1861 to 930 by the end of the 1870s, although they were still a smaller part of the periodicals market than newspapers by the 1880s in numbers of titles available.20 From the 1870s magazines catered more for niche readerships such as men, women, boys, girls and other interest groups.21 The most significant periodical to launch between these two weeks from Hewitson’s diaries was George Newnes’s Tit-Bits, first published in Manchester in 1881; its content — cuttings and ‘tit-bits’ from other publications — was less innovative than its promotional and distribution techniques, and its reader involvement through submission of material and prize competitions.22

Local markets were generally too small, certainly in a town the size of Preston, to attract enough readers to make a local magazine viable; low circulation meant low advertising charges. For those produced by ‘pressure groups’, such as temperance and Roman Catholic publications, this was less important. A rare Preston magazine in this period was Longworth’s Preston Advertiser, Railway Time Table, and Literary Miscellany (1867–82), a free-distribution sideline to David Longworth’s printing business.23 Longworth is the only Preston journalist known to have written in Lancashire dialect, reprinting some of his prose as pamphlets after their publication in the Advertiser.24 None of the six newspapers and two magazines launched in Preston in the 1870s lasted more than a year, most running for a matter of weeks. Of two attempts at satirical magazines, the longest-lasting, the Wasp, ran for thirteen weeks in 1878. In the 1880s there were two short-lived sports titles, the Preston Telegraph (1881) and Preston Football News (1885), of which no copies survive.25 These unsuccessful attempts to meet the growing demand for football news too early, before the market was big enough to make a local sports paper viable, show how the success or failure of any title was always a negotiation between publishers and readers.

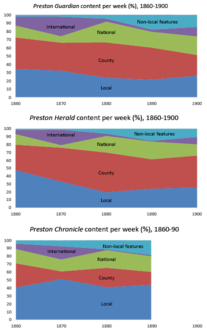

Within Preston’s main newspapers, local and regional content was the single most significant type of subject matter, but there was plenty of non-local material too in ‘local’ papers. Figure 5.2 below shows the trends in different types of geographical coverage. (The increases in international news in 1870 and 1900 are due to the Franco-Prussian War and the Boer War, respectively.) The three main papers have roughly similar proportions of geographical content, and follow similar trends. They can be differentiated, however. The Guardian and the Herald had the most county material, reflecting their wider circulation areas, attempting to be county papers for North Lancashire. The Chronicle was the most local paper, with around forty per cent of its content concerning Preston. The percentages mask the growth in number of pages and columns, so that in fact there was more of everything by the end of the century — more local and Lancashire news, and even more non-local news, from other parts of the British Isles, Parliamentary news and foreign news. But the biggest increase was in non-local features, including serial fiction, women’s columns and general interest articles. The New Journalism was on its way.

Fig. 5.2. Geographical coverage trends in main Preston weekly papers, 1860–1900. Author’s graphs, CC BY 4.0.26

A Week in the Life of a Provincial Newspaper Owner-editor, 1884

Saturday 5 January 1884

Had a fairly easy day as to work. In the evening a blustering, blackguardly fellow — Alderman Walmsley assaulted me in Fishergate — struck at me several times with a folded newspaper on account of some paragraphs in the Chronicle. I did not retaliate and decided to summon him before the magistrates.

Anthony Hewitson was now the owner-editor of the Preston Chronicle, published every Saturday. ‘Work’ on publication day would involve overseeing distribution, selling newspapers from his shop counter on Preston’s main street, Fishergate, and chatting to customers. At five o’clock, Hewitson was in the shop with his wife, gossiping with auctioneer Henry Walton, another man, Henry Nightingale, and the errand boy, when Benjamin Walmsley, a mill owner and senior Conservative on the town council, burst in. He bought a Chronicle, had angry words with Hewitson about a ‘paragraph’ in the paper, refused to leave, and followed Hewitson onto the street, slapping the editor about the face with a folded-up copy of Hewitson’s own paper.27

Hewitson had been mocking Walmsley in print for more than a decade, using a personal writing style later associated with the ‘New Journalism’. He had previously insinuated that Walmsley had not one slate missing but the whole of his roof, and was an ass and a brainless fool. Today’s paper included a twenty-line story, ‘The Reason’, mocking an unnamed alderman (in fact Walmsley) who stayed away from a club for fear of being attacked by another member.28

The incident is a physical manifestation of many aspects of Victorian print culture. Unlike the anonymous editors of London papers and periodicals, Hewitson was physically present to his readers, and performing local identity.29 In contrast, Hewitson’s rival and former employer, George Toulmin, was less approachable, cutting himself off from large sections of Preston society through his teetotalism, while his business was large enough to employ others to sell newspapers at his front counter. Hewitson was at the centre of a physical, local community.30

Further, the editor and the reader — and the editor’s wife and friends — were all part of the same ‘interpretive community’, decoding the paragraph in the way intended by the writer (not Hewitson, incidentally), using their cultural capital to draw shared meaning from the scrap of gossip. Walmsley responded to the text emotionally, as did many newspaper readers. A similar dramatic incident occurred in Leith in 1870, when plumber and gas-fitter John Fulton Maccallum had tried to throw the editor of the Leith Herald, Ebenezer Drummond, into a bath full of water, ‘telling him that he would teach him not to write against him in the papers and say that his singing at the Choral Union Concert last week was “execrable,” and that he had neither “voice feeling, nor training.”’31 However, most readers responded less violently. Hewitson and Walmsley were part of the same geographical community, even part of the same local elite, but community is not necessarily harmonious.32

Hewitson was at the counter, selling copies of his paper, a very direct form of distribution, but there were many other ways in which newspapers reached the hands of readers. We have seen the importance of newsagents, news rooms and pubs in Chapter 2. Postal distribution was used less after 1855, but did continue, especially for papers with large sales territories. In the 1840s ‘a large proportion’ of the Lancaster Guardian’s copies were sent by post; the same printed stamp allowed re-delivery at no extra charge, so that in 1851 the wholesale newsagent W. H. Smith reckoned that ‘every daily paper published in London is read by three or four distinct persons.’33 In evidence to the Newspaper Stamp Committee, Smith gave the example of a clergyman whose Times (cover price 5d) only cost him a penny because he was part of a chain of readers including a Norwich news-room, an individual reader in Norwich and a nearby village, followed by two or three other places.34 Some copies of local papers passed through similar chains of readers, for example those sent to Clitheroe weaver John O’Neil by friends and relatives.35 Second-hand papers were sold by news rooms and newsagents.36

Papers were distributed to homes by newsagents such as Preston’s John Proffitt, who offered free delivery to ‘any address in town or country’.37 Newspaper publishers offered the same service themselves, such as the team of ‘newsmen’ employed by the Warrington Advertiser for that town’s outlying areas in 1863, who had ‘districts assigned to them for regular perambulation’.38 This system dated back to the eighteenth century, and has similarities to the work of chapmen.39 J. Barlow Brooks remembered a young door-to-door newsagent in his home town of Radcliffe near Bolton, who brought weekly papers, most of them local and regional titles, every Saturday afternoon.40 In 1840s Lancaster, however, Mr Milner, the owner of the Lancaster Guardian, preferred to cut out the middle-man, believing that ‘townspeople who wanted a copy of the “Guardian” ought to go to the office for it. No would-be newspaper agent need apply.’ Only the town’s bellman and bill-poster was allowed to vend them away from the office, selling around 200 copies a week, mainly among farmers coming into town on Saturday.41

Inside Saturday’s Chronicle, besides the paragraph of gossip that so incensed Alderman Walmsley, were many ‘feature’-style articles, reflecting the Christmas and New Year period during which the paper was prepared, traditionally a quiet time for news. Consequently, two columns listing the current stations of the army and navy, and a full-column advert listing titles of sheet music available at the Chronicle office, were probably filler, to make up for the lack of news. Cotton workers were still on strike in East Lancashire and the county magistrates had held their quarter sessions, producing two columns of short crime stories. There were reports of Christmas tea parties at local churches, district news from outlying areas, including a horse sale at Cockerham, and two and a half columns of readers’ letters. International news and stories from the rest of the UK took up less than a column. Features included ‘varieties’ culled from books, magazines and newspapers, two columns of agricultural news, one column on the poet Oliver Goldsmith (part of a series by a local writer), reminiscences of Goosnargh, half a column on the coin collection at the town’s museum, poems, an instalment of a serial novel, ‘Some Lasses of Andernesse, an original story by a Lancashire Lass’, and ‘Our Ladies’ Column, by one of themselves’. There were reviews, of the visiting Carl Rosa Opera Company, a local pantomime, and half a column of ‘Literary Notices’, including reviews of two almanacs and a round-up of the January magazines and part-works. Titles reviewed (probably by Hewitson himself), included Longman’s Magazine, English Illustrated Magazine, Science Monthly, Magazine of Art, The Atlantic, Arabian Nights’ Entertainment, Amateur Work, Universal Instructor, History of the World, Magazine of Art, Picturesque Europe, Practical Dictionary of Mechanics, World of Wonders, Royal Shakespere, Popular Educator, The Sea: Its Stirring Story of Adventure, Little Folks, Quiver and Cassell’s Magazine.

The Chronicle of 1884 had increased only slightly in size since Hewitson took it over, adding 1 column per page in 1875 but maintaining 8 pages and 1 issue per week. If he had been slapped in the face with a Saturday Preston Herald or Preston Guardian, it would have stung a little more. The Saturday Herald of 1884 was 12 pages (7 columns in the main part, with a 4-page supplement of 6 columns); it had widened its pages since 1868, and doubled the size of its Wednesday edition from 4 to 8 pages. As Dallas Liddle has remarked, this growth in the material size of newspapers, and therefore in the amount of material they published, is one of the most striking, yet neglected, aspects of nineteenth-century newspaper history.42 Hewitson’s Chronicle was unusual in growing by only 16 per cent between 1868 and 1884; more typical was the Preston Herald’s growth, from publishing around 170,000 words per week to 300,000. Looking back further, the Preston Guardian of 1884 reckoned to publish in a month the same amount of material as a Preston paper of 1829 published in a year.43 And it was more for less, with prices falling by a third in the last 3 decades of the century: in 1868 the Liverpool Lyceum had spent £335 per year on supplying 218 individual copies of newspapers and magazines; by 1900, they bought 236 for £237.44

Sunday 6 January 1884

In bed till nearly noon. In afternoon Mr Standen, a young naturalist from Goosnargh came to my house, had tea and then went with me and my wife to St George’s church. Good music. He afterwards for upwards of an hour was at my house. A very nice intelligent young fellow.

Hewitson’s visitor Robert Standen is an example of the experts, litterateurs and activists who were part of the reading community of each local paper; these individuals were usually part of professional, political and learned networks, whose activities were bolstered by their contributions to, and appearances in, the local press. The networks would probably have existed without the help of the local newspaper, but it could act as a catalyst and amplifier. Standen (1854–1925), an expert on molluscs, went on to work at the zoology department of Owens College, Manchester (forerunner of Manchester University) and at the Manchester Museum. Hewitson reprinted some of Standen’s articles about Lancashire wildlife from the Field Naturalist magazine, an example of the local paper’s role in curating material relevant to its local readership.45

But the local newspaper did more than curate content from elsewhere. It was a major publishing platform for literary and learned material. For certain genres, such as fiction, poetry or history, for example, more material was published in weekly local and regional newspapers than was published in magazines or in books. As Graham Law has established for fiction, this requires us to rethink nineteenth-century publishing history.46 This non-news material, produced mainly by non-journalists and amateurs, was one factor in the failure of journalists to establish themselves as truly professional (anyone could write for the newspapers), and raises doubts about any decline in a public sphere in this period.

Two examples, of poetry and history published in the local press, challenge conventional perceptions that the local newspaper was a minor part of Victorian print culture; that few non-professional writers were published; and that literary culture was situated largely in London. Alongside the work of other amateur contributors, the output of local poets and historians shows that the local newspaper was a porous, culturally democratic and broadly inclusive publishing platform, encouraging popular participation — the local hub of a geographically distributed, truly national print culture.

In the previous day’s paper Hewitson had published three poems, the anonymous ‘New Year’s Eve’, ‘A Hymn for New Year’s Day, 1884’ by the established poet Martin Tupper, and ‘Ghost Stories’ by local poet J. V. Caffrie. All across the nation local papers published similar numbers of poems, so that, during the 1880s, more than 100,000 poems were published in the English local press each year; I estimate that more than 4 million poems were published on this platform during Victoria’s reign in England, meaning that most Victorian poetry was published and — from the 1860s — read in the local newspaper.47 This challenges claims that poetry became marginalised and neglected, particularly among working-class readers.48 Thackeray’s eponymous character Arther Pendennis ‘broke out in the Poets’ Corner of the County Chronicle’, as did the young Thackeray himself, in Exeter’s Western Luminary; Branwell Brontë published his first poem in the Halifax Guardian, but these well-known writers were a minority. Most were like Hewitson’s friend Caffrie, a local doctor, their poetic careers climaxing with an appearance in the local paper. Nonetheless, their verse can be seen as a journalistic form that added an emotional dimension to the news.49 In the previous week’s Chronicle Hewitson had published an anonymous poem, ‘The Ideal’, from the Atlantic magazine, an example of how the local press, as an aggregate, provided a national distribution system for poetry first published in books and periodicals, reprinting verse for readers who never saw it in its original form.

Similarly, the local weekly newspaper was probably the most popular platform for the publishing of history in the nineteenth century, including chronologies, news of archaeological finds, dedicated ‘Notes and Queries’-style columns, folklore, dialect and wholesale scholarly transcription of historical sources.50 While historical topics from across the world were covered, the focus was on local history. This huge mass of history writing was produced mainly by gentleman amateurs, local newspaper editors, and readers, all part of what Alan Kidd describes as a ‘local history community’.51 These individuals also wrote books and articles for transactions of learned societies and for popular magazines. Local history material often moved from the columns of local newspapers into books, usually published from the same newspaper office.

Like many newspaper editors, Hewitson was a keen historian. A member of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, he wrote or edited four history books. He took over the Chronicle from another historian-editor, William Dobson, a member of the scholarly Chetham’s Society and author of nine books on Preston. A study of provincial editors of the 1840s found that, of forty-nine who wrote books, thirty-one wrote histories. It was predominantly ‘local history which was full of intense pride of locality’.52 These journalist-historians were members of local and regional networks of scholars — five of the founding members of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire were newspaper editors.53

In 1871 Hewitson and a local Roman Catholic historian, Joseph Gillow, transcribed and annotated a manuscript diary written from 1712 to 1714 by Thomas Tyldesley, a Roman Catholic officer in the rebel Jacobite army. Hewitson published their edition of the diary, in weekly instalments of 2–3,000-word annotated entries, from 2 December 1871 to 10 August 1872. In 1873, he republished the diary in book form, using the same type, which had been composed, unusually, across two columns in the newspaper, for this very purpose.54 Gillow, his co-editor, was a gentleman amateur (a common type of Victorian local historian), described as ‘the Plutarch of the English Catholics’, who went on to compile the five-volume Biographical and Bibliographical Dictionary of the English Catholics, still in use today. Before republishing the diaries in volume form, Gillow and Hewitson revised their edition, added an introduction and index, and Hewitson circulated the proofs for informal peer review to four other members of his region’s local history community.55

Some very rough calculations suggest that more words of historical writing were published in local newspapers than in book form, or in magazines, at least in the sample year of 1890, when the boom in history publishing via the local press was almost at its peak. Multiplying the number of words in a typical history book of 1890 (224,000) by the number of books published for the year (430, according to the COPAC catalogue), produces a figure of 96 million words of history published in book form during 1890.56 For magazines, extrapolating from two weekly titles publishing a significant amount of history — the Academy, a learned review, and the Girl’s Own Paper, an earnest, improving but well-written magazine for girls — produced a figure of 106 million words of historical writing in 1890. For newspapers, a fairly typical local bi-weekly, the Lancaster Gazette, published around 225,000 words of history in 1890. Multiplying by 1000 (the approximate number of weekly and bi-weekly newspaper titles published that year, excluding morning and evening newspapers) produces a figure of 225 million words of history in local weekly newspapers. Obviously, these figures can be disputed (the figure of 430 history books seems low, and probably omits many local history books published outside London). However, the figures are of a similar order of magnitude, and suggest that at least as much, if not more, history was published in local weekly newspapers than in books or magazines. The high sales of local newspapers across the country means that historical writing, often of a high scholarly standing, reached all levels of society, regardless of class, gender or literacy. The volume of history (and many other genres) disseminated in this way places the weekly local newspaper at the centre of nineteenth-century writing and publishing.

Amateur local poets and historians were part of a hidden army of district correspondents, campaigners, experts, inveterate letter-writers and dialect aficionados, and officers of clubs, societies and local institutions. The uniform columns of print disguise the number and variety of amateur authors, comprising men, women and children from all classes. Their writings and their lives take us beyond the ‘canonical fraction’ of journalism and literature, and reveal a thriving cultural public sphere, a space in which private citizens could join public debate.57 I estimate that between a quarter and a third of editorial texts were produced by such non-journalists. They are sidelined by anachronistic assumptions that journalism is produced by journalists, despite general scholarly agreement that journalism was not and is still not a profession along the lines of medicine or the law. Indeed, one reason that journalists failed to establish themselves as a profession was that they were not able to differentiate themselves from these amateurs, dilettantes and dabblers.58

Monday 7 January 1884

Bothering about the Walmsley job.

Tuesday 8 January 1884

Working. In afternoon took out a summons against the blustering blackguard.

The case went to court, Hewitson won and Walmsley was fined twenty shillings plus costs. More significant is the word, ‘Working’, which opens Hewitson’s diary entry for Tuesday, and provides an opportunity to examine the most common type of Victorian editor, the local newspaper editor.59

Editing a weekly or bi-weekly local paper was not a demanding job: in the 1840s, the editor of the weekly Preston Pilot, a Mr Higgins, was also an actuary at the town’s Savings Bank; in the 1860s Wemyss Reid found that two-and-a-half days a week was enough to edit the bi-weekly Preston Guardian, leaving him ‘ample leisure’ for reading Carlyle, Browning and Thackeray, and long walks in the countryside.60 In 1855 it was said that ‘the life of a country newspaper editor consists in doing a day’s work in three days at the beginning of the week, and three days’ work in one day at the end of the week.’61 This captures the rhythm of Hewitson’s week as an editor. Friday, before press day, was the busiest:

Laid in bed till 8.30 this morning. Looked through letters; sub-edited; then proceeded with writing remainder of description of Newhouse Catholic Chapel, which I began last night. Next proceeded with a leader, on Municipal Corporation, which I wrote in three hours. Subsequently read proofs; and then wrote a column of Stray Notes. Had three glasses of beer during the night. Finished work at 2 o’clock in morning.62

The work involved directing reporters and contributors and sub-editing (copy editing) their work, some of the more prestigious writing, and liaising with compositors and printers. Local newspaper editors were not held in high esteem, at least in 1850, when a writer in Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine claimed that

there is always at hand some unfledged poet, some incomparable, because uncompared, local genius to fan the flame of discontent and in the fullness of his pride, to say nothing of his love of pelf [money], willing to undertake the Sisyphian labour of conducting a new journal.63

Edward Dicey believed that provincial editors were generally journalists who had tried and failed to make a career in London, but this neglects the many reasons why ambitious and able journalist such as Hewitson chose not to live and work in London.64

Editors were not very powerful. Many, particularly on smaller papers, were little more than reporters with a title. In 1857–58 Hewitson, for example, was ‘compositor, reporter and editor’ of two small Midlands papers in succession, staying less than six months at each; he was then twenty-one years old, and had completed his printing apprenticeship only months before. In 1868, Hewitson claimed that he was the only resident editor of a Preston paper, suggesting that on the town’s other papers, the job was done from London.65 However, in earlier decades other Preston newspaper proprietors had also edited their papers, including Wilcockson in the early years of the Chronicle, Joseph Livesey in the early years of the Guardian, and William Dobson throughout his ownership of the Chronicle. But by the 1880s Hewitson’s rivals, George Toulmin & Sons, had a more typical arrangement in which they as owners hired and fired editors, as the Preston Herald had done from its purchase by a limited liability company in 1860.66

Editors who did not own their papers had far less power than Hewitson did in 1884, of course, and it is significant that the best known provincial editors, such as C. P. Scott and Edward Russell, also had a stake in their publications.67 Otherwise, there was the danger of humiliation and interference from the owner, as when the editor of the Lancashire Daily Post was forced to publish a statement in 1900, dissociating his employer, George Toulmin, from the previous day’s leader column, which had attacked Labour leader Keir Hardie, then a Preston Parliamentary candidate.68 Those who were also ‘conductors’ or ‘managers’, even without a share in the ownership, may have held more sway.

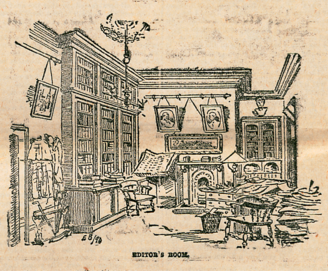

However, it was more common for owners to employ editors. It was a job with a high turnover, as Hewitson’s early experience in the Midlands suggests. Preston’s four bi-weeklies and one evening paper had thirty different editors in forty-five years, the Lancashire Evening Post with at least six between 1890 and 1900 alone.69 Few editors of Preston papers had traditional Lancashire surnames, suggesting that their brief time in Preston was part of an itinerant journalistic career. Former printers were more likely to become editors of smaller papers, whilst graduates and literary men were found on more prestigious papers, such as ‘poet and mystic’ Henry Rose, editor of the Lancashire Evening Post in 1890, the novelist A. W. Marchmont BA, editor of the Preston Guardian and the Evening Post in 1894, and J. B. Frith BA, editor of the Evening Post in 1897. An 1894 picture of the editor’s room at the Preston Guardian and Lancashire Evening Post (Fig. 5.3 below) suggests that, by the 1890s at least, a provincial newspaper editor in a large town was a literary gentleman. It could almost be the study of an academic or an author, with its books, paintings and writing desk, very different from the workspace Hewitson would have occupied as compositor, reporter and editor of the Brierley Hill Advertiser in 1857.

Fig. 5.3. The editor’s room, Preston Guardian and Lancashire Evening Post, 1894. Source: Preston Guardian jubilee supplement, 17 February 1894, p. 2 (British Library MFM.M40487-8). © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

The writer in Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine of 1850 believed that editors of provincial papers could not take ‘high social rank’ because they were usually ex-printers, ‘deficient in education, breeding, and position’, while Edward Dicey, writing in 1868, thought that ‘the very indefiniteness of his social standing tells unfavourably upon him’.70 Hewitson does not fit this stereotype, partly because as a newspaper proprietor he ranked above a mere editor, but also because of his education. His personal qualities, too, probably enabled him to move between the different ranks of society, as evidenced by a request from a coal agent for marital advice in 1872, and an invitation to mediate in a dispute between grocery magnate E. H. Booth and Alderman James Burrows in 1896.71 His best friends, when he lived in town, were a shoemaker and a slightly bohemian photographer. His church-going career ascended the social scale from the Nonconformist Cannon Street chapel to the socially exclusive St George’s Anglican chapel.72 From 1885, he rented two country villas in succession, rearing livestock and socialising with local gentry. During Hewitson’s court case against Walmsley, his solicitor argued that as ‘a gentleman holding the position he did, he could not submit with impunity to such an indignity in a public thoroughfare’.73 Yet his wife managed a stationery shop, and he spent most Saturdays standing at his shop counter, taking tuppences for the newspaper he owned.74

Hewitson’s uncertain social status differentiated him from anonymous London owners and editors. He was a public figure, active in local life — many provincial owner-editors had their names emblazoned above their doors on the main street of their town.75 ‘There is nothing of the anonymous about provincial journalism’, as Dicey noted.76 Hewitson also built a reputation as an author, producing fourteen books, including eight of local interest, four of local history and one of travel. Dicey believed that this lack of anonymity made provincial journalism timid. Those like Hewitson who imitated the bolder style of the London press were at risk of assault with a folded newspaper or worse. Indeed, W. T. Stead’s dislike of journalistic anonymity as ‘impersonal’ and ‘effete’ may have stemmed from his experience as a provincial editor.77 But there were advantages in being known: greater accountability to readers, and a greater understanding of them. For a journalist with Hewitson’s evident social ease, standing at a shop counter Saturday after Saturday, selling papers and gossiping, was time well spent. It would have enabled him to gauge responses to what he published and to develop personal relationships with many of his ‘constant readers’, giving physical reality to an interpretive community. Newspaper proprietors like Hewitson were ‘communications brokers’ marshalling a local public sphere, ‘for whom the imagined community of readers was a real community of friends and business associates.’78

Wednesday 9 January 1884

At work all day. Today Richard Cookson 73 years of age married a woman aged 71 after 50 years courting. He lives at Goosnargh.

Thursday 10 January 1884

Working all day. Wrote my first article about my American tour today.

Hewitson mentions two stories in these two diary entries, both signalling major changes in British journalism that coalesced in the ‘New Journalism’ of the 1880s. The amusing, touching tale of the fifty-year courtship, which made a paragraph in the following Saturday’s paper, was typical of a more popular, light, ‘human interest’ journalism, while Hewitson’s trip to America symbolised the view that most of the changes in British journalism came from the United States. Joel Wiener argues that a more democratic American society produced a more demotic style of journalism, focusing on ‘human interest’ stories such as crime rather than high politics, inventing the newspaper interview, deifying speed in reporting and publishing, and presenting this news in a more visually attractive way, with illustrations and bold headlines. This more populist style reached mainstream newspaper journalism much earlier in the US than in Britain.79 However, in his earlier and more sophisticated work on the New Journalism, Wiener placed more emphasis on British journalistic genres from the radical unstamped press, Sunday newspapers, provincial papers, and magazines, alongside such American innovations as interviewing and investigative journalism.80

‘New Journalism’, a phrase probably coined by W. T. Stead,81 is best seen as a constellation of journalistic techniques, which moved between different types of publication in different places. This alternative explanation is supported by a study of Hewitson and other innovative provincial journalists such as Stead, and builds on Wiener’s original insights. Stead was not unique in bringing innovation from the provinces to the metropolis, and exemplifies a bigger point, that the provincial and London press were part of the same system. British journalism was more networked and less centralised than most accounts suggest.

Table 5.2 below attempts to list the main elements of ‘New Journalism’. Hewitson’s Preston Chronicle of 5 January 1884 includes some of these elements: his characteristically personal style, the item of gossip about the fifty-year courtship, a women’s column, and a serial novel. Similarly, the Preston Herald of the same date had a column of ‘London gossip’, a first-person flaneur’s account of ‘Going to the Races’ ‘(by the “Herald” Wanderer)’, a rather wooden ‘Open Secrets’ gossip column, also written in the first person singular, and ‘The Ladies’ Column’ (‘By a Lady’). Of course, Hewitson had been writing ‘articles and paragraphs of a spicy character’ (as a barrister described his personal, gossipy style, in a libel case against him), since the 1860s.82 In 1872 he had used investigative techniques on a sensational story about a fourteen-year secret marriage between the vicar of Preston, Rev John Owen Parr, then in his seventies, and his thirty-five-year-old housekeeper.

Table 5.2. Some elements of the New Journalism

Few individual elements in the table above were new by the 1880s. As Wiener, Laurel Brake and John Tulloch have pointed out, most had appeared in other types of newspaper or in magazines aimed at women and children, decades earlier.83 What was new was their combination in a critical mass, and their appearance in prestigious London morning and evening newspapers. For example, some of the unstamped radical newspapers of the 1830s were written in a sensational or chatty style, and included illustrations, answers to correspondents, campaigns, and reader-contributed material. The provincial weekly news miscellanies studied by Graham Law — significant ‘carriers’ for these New Journalism elements from the world of magazines into the world of newspapers — contained a slightly different combination of elements, such as gossipy London letters, illustrations, serial fiction, bigger headlines, children’s columns, answers to correspondents, competitions and reader-generated content.

The ‘New Journalism’ was not the result of a linear progression, rather a recombination of journalistic elements. Many of these elements had previously been associated with particular types of publications or audiences, generally of lower status, so what was shocking to commentators in the 1880s was their appearance in the higher status form of the London morning newspaper. Dallas Liddle, in his application of the ideas of Bakhtin to Victorian journalistic genres, explains that ‘genres contain and encode meaning […] working to make the text they contain reflect the genre’s own worldview.’84 Tracing the paths of any of these New Journalism elements, as they jump from one type of publication to another, reveals the complexity and interconnectedness of journalism, by nature derivative or mimetic. Some of these elements could be found, at various times, in American, Scottish, Irish or English provincial newspapers; in disreputable Regency gossip sheets or the society newspapers of the 1870s, in mid-century improving and family magazines. Two brief examples will suffice, but as Liddle argues, a more systematic analysis is overdue.85

To take the example of interviewing, the first known journalistic interview was published in 1836, by expatriate Scottish journalist James Gordon Bennett in the New York Herald. It was another twenty years before an interview was published in a British paper, by Henry Mayhew, in the Illustrated Times in 1856.86 Around the same time, another British journalist, Edmund Yates, ran a series of interviews with ‘Men of Mark’ in his Train magazine.87 Interviewing was considered shockingly bad manners, an invasion of privacy, on both sides of the Atlantic, until about the 1860s in the US, and the early twentieth century in the UK.88 W. T. Stead published some interviews on the Darlington Northern Echo in the 1870s and on the London evening paper the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s; other London evenings also carried interviews. The technique began to appear in London morning papers from the 1880s.

A second example, the ‘London letter’, combining political, literary, artistic and society gossip, developed from London correspondence sent to provincial papers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. A more scurrilous version could be found in disreputable London weekly papers of the 1820s and 1830s such as The Satirist and Town. When large provincial weeklies switched to daily publication in the 1850s they adopted the London letter, which also appeared in the new weekly news miscellanies from the 1860s, and provincial evening papers in the following decades. Some of the same London hacks who gave the impression that they lounged in every club and dined with every earl and actress wrote similar material for the new weekly London ‘society’ papers such as the World and Truth. Meanwhile, London correspondents of provincial papers invented ‘Lobby’ reporting from Parliament, supplementing their London letters with exclusive political gossip not available to metropolitan papers. Eventually, in the 1890s, columns such as ‘London day by day’ appeared in the Daily Telegraph and other London morning papers. The provincial tail had wagged the metropolitan dog, challenging simplistic ideas of the diffusion of innovations from the centre.89 These two examples show that the relationships between metropolitan and provincial press, and American and British journalism, were more complex, and dialogic, than simply one of core and periphery.

These techniques and genres were spread by journalists such as Edward James Whitty, owner-editor of the Liverpool Journal, and agent and correspondent for American papers, reading exchange copies of newspapers and magazines sent within and between countries.90 They were also spread by journalists changing jobs and taking successful techniques with them, and by journalists travelling between Britain and America — American journalists working as London correspondents, British expatriates coming back to visit (such as Hewitson’s friend Ernest King, former editor of the Blackburn Times, now editor of the Middletown Sentinel, Connecticut) or British journalists such as Hewitson visiting the United States for business and pleasure. Many others made the same journey as Hewitson and his daughter: William Haly, in preparation for the launch of the Morning Star in 1856; Hewitson’s former employer, George Toulmin, in 1865; George Rippon of the Oxford Times as a youth in 1868; W. E. Adams of the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle in 1882 (the success of his travelogue, Our American Cousins, may have inspired Hewitson), and William Tillotson of the Bolton Evening News in 1884 (to open an American office of his fiction syndication bureau).91 Other provincial journalists such as W. T. Stead were fascinated by America, and its journalism, long before they ever travelled there.92 English local newspapers, like other parts of their communities, were ‘engaged in a dialogic relationship with other localities and global flows of media and capital.’93

Once we reject the idea of a linear progression towards the New Journalism, it is harder to tell the pessimistic story of decline of the public sphere, or a deterioration from the educational ideal of the press at mid-century to a more consumerist, representative ideal at the end, typically symbolised by a decline in Parliamentary reporting.94 It is true that a more populist, less improving tone of voice took hold in some Conservative provincial miscellanies such as the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph and later the Daily Mail, but the older, more democratic, improving Liberal ideal survived, and even flourished (in newspapers, and notably in the British Broadcasting Company, from 1922).95 Some Liberal newspaper publishers squared their principles with aspects of the New Journalism, notably in Scotland, but also in Ireland and on Gladstonian evening papers such as those at Middlesbrough and Blackburn, and in many of the weekly news miscellanies.96

It was not either/or, but both/and. There was more of everything — more publications, more editions, more pages, more columns, more journalism. The content of Preston’s newspapers changed during the period, but they provide little evidence that ‘serious’ news was being replaced by ‘feather-brained’ features or sensational reporting.97 Instead it was being augmented by new types of content, with an increase in non-local content such as fiction and syndicated women’s columns. There were also political differences, as Law suggests. The Liberal Preston Guardian had more coverage of Parliament, national politics and economics in 1900 than it did in 1860 (two columns for the sampled September weeks in 1900, 1.7 columns in 1860), although the growth in the size of the paper meant that this coverage declined as a proportion of the issue, from 2.5% to 2.3%. The Lancashire Evening Post, also Liberal, had more than 11 columns of Parliamentary and other political and economic news in 1900, a substantial amount, although this was a decline from 17 columns in 1890. The Chronicle (Liberal) had about the same quantity in 1890 as it did in 1860 (a slight decline from 9/10 of a column to 4/5). In contrast the Tory Herald had no Parliamentary coverage in 1900, possibly because of its more populist approach, possibly because Parliamentary news had been squeezed out by 13 columns of foreign news, mostly about the Boer War.

The Liberal educational ideal of the press continued alongside the New Journalism in England and Scotland, often emanating from the same provincial publisher. From the 1850s onwards, they segmented their local markets, offering different types of newspaper to different readerships, as with the Toulmins’ Preston Guardian and Lancashire Evening Post. In Liverpool, Edward James Whitty and his successors published a traditional weekly, the Liverpool Journal (1830–85), then in 1855 Whitty launched the Daily Post, a morning paper aimed at middle-class readers, followed in 1878 by a weekly news miscellany, the Liverpool Weekly Post, for a working-class family readership, and in 1879, the Liverpool Echo, aimed mainly at working-class men. The provincial morning papers continued to imitate the Times, whilst weekly news miscellanies (and the new ‘literary supplements’ of the traditional county journals) and evening papers offered New Journalism. The national picture, incorporating metropolitan and provincial developments, is very different from the narrow London view.

Friday 11 January 1885

Hard at work from 9.30 in morning till 1.45 on Saturday morning.

Hewitson worked a 16-hour day to prepare the paper for printing. It included the first instalment of ‘Westward Ho! America: There and Back Again, Scenes and Sights on Sea and Land, Particulars of a Recent Trip’, by “Atticus” (evidence, apart from anything else, that local newspapers could be profitable businesses, enabling owners to travel the world). The travelogue continued weekly until September, and then — like his serialisation of the Tyldesley diary — reappeared as a 281-page book in April 1885, printed and published at Hewitson’s Chronicle office.

Provincial booksellers and publishers had been the progenitors of provincial newspaper publishing in the eighteenth century. The book trade may have been concentrated in London, but as with newspapers, almost every town and city became a publishing centre. Much work has been done on the connections and contrasts between supposedly ephemeral periodicals and apparently permanent bound volumes (often containing material first published in the paper), revealing a fluidity behind the implicit cultural hierarchies of different publication formats.98 But these scholars have focused on London publishing; a study of book production by local newspaper publishers is needed.

After 1884

Hewitson continued to run the Chronicle until 1890, when he sold it to two local journalists. Three years later it was up for sale again, and this time Hewitson’s rivals, the Toulmins, bought the title and closed it down. No diary survives for 1893, so we can only imagine Hewitson’s feelings. But the economic structure of provincial newspaper publishing was changing, and under-capitalised owner-editors like Hewitson were being squeezed out, especially in local markets like Preston, dominated by much more powerful publishers. The Toulmins showed their might in 1886, when they were goaded into launching a pro-Gladstone halfpenny evening paper, the Lancashire Evening Post, in response to a paper of identical politics set up ten miles away in Blackburn (traditional Toulmin territory), by interlopers from Middlesbrough. Both these new evening newspapers carried plenty of sports news, particularly football news. But Hewitson’s personal dislike of the game, and his press campaign against rates-funded expansion of Preston’s docks, were both out of step with the public mood, and probably cost him sales.

The Conservative Preston Herald continued its competition with the Liberal Preston Guardian, but probably lost money and required continued party subsidy. While the Guardian boasted ‘A Staff of over Twenty Reporters — the largest in the Kingdom’ in 1889 (this may have included Evening Post staff), the Herald had only seven.99 The Tory paper, which had been offered to Hewitson in 1874, changed hands in 1890, valued at £4,357.100 Other Preston publications came and went, but nothing to challenge the Toulmins. Four Roman Catholic titles were launched in the 1880s and 1890s, plus at least one parish magazine, issued by the parish church (1898–99), with some local content. The Catholic News (1889–1934) was the first Preston publication to appeal directly to the town’s large Catholic minority, but struggled until it was incorporated into Charles Diamond’s syndicate of local Catholic papers. The temperance publishing tradition continued after Joseph Livesey’s death in 1884 (an example of membership publications immune to market forces) and there were a number of magazines, both satirical and general local interest.101 Five new periodicals with local content were published in the late 1890s, three of them surviving into the twentieth century. One, the Empire Journal (1896–97) had a short and peculiar career, beginning in December 1896 as a free-distribution magazine for ‘Preston and District’, before attempting to go national and even international, presumably on the model of Tit-Bits and Answers, whose style it followed. It was gone within a year. More dynamic developments were happening in Manchester, where Edward Hulton was building a popular newspaper empire based on sport, before he was eclipsed by Alfred Harmsworth, who successfully transferred magazine-style journalism into a London evening paper and then the hugely successful Daily Mail.

Hewitson’s career began before the repeal of the newspaper taxes; he became the owner of a weekly paper when owner-editors were common. As a reporter and a publisher of newspapers and books, he was part of important national networks. The strategies he pursued to defend his paper’s market share were very successful in the late 1860s and early 1870s, although even then he was only in third place in Preston’s press pecking order, after the commercially powerful Toulmins and the politically subsidised Herald. However, Preston’s print culture changed significantly in the late 1880s; the Toulmins’ capital and investment in distribution and news-gathering enabled them to launch a successful evening paper, meeting a new demand for more up-to-date news, and football coverage. The Lancashire Evening Post took advertising revenue from other newspapers, and Hewitson’s Chronicle, without the political subsidy enjoyed by the Herald, began to struggle. An individual journalist could make an impact until the third quarter of the nineteenth century, but after that, capital became more important.

At mid-century, as populations and reading ability expanded, the local market was able to support more titles, while for newspapers particularly, the average number of pages, physical dimensions, frequency, and copies sold all increased. The local print market continued to expand into the early twentieth century, but consolidation made it harder to enter. By the end of the century there were fewer titles of any consequence in Preston, but they each sold more copies. However, Preston’s local press, for the most part, continued to be produced by local people who were deeply involved in the political, cultural and economic life of their area. The corps of correspondents who fed snippets to each paper were mainly local people; only the reporters and editors were likely to be from elsewhere.

The abolition of the compulsory Newspaper Stamp, and the nationalisation of the telegraphs, both helped the provincial press, but continuities and changes of longer duration were also important. These might include the rapid growth in literacy and expanding populations, which may have had more impact in the provinces, where reading ability caught up with London and where growing populations created newly viable local and regional newspaper markets. There was continuity in the demand for local content, an unmet demand which could only be answered when cover prices fell to a penny or a halfpenny after 1855.

So the provincial press expanded more than the metropolitan after 1855 for many reasons, which combined in complex and often unforeseen ways. All these factors — pricing, distribution methods and costs, news costs, print times, proportion of income from advertising versus copy sales, distance between publishing office and market, size of market, literacy, disposable income and a constant thirst for publications that reflected readers’ local lives — deserve more study.

New types of content were added to the local paper, as literacy continued to spread, prices came down, and newspapers worked to turn communal readers into individual purchasers, using the techniques of New Journalism. The cultural work of the local press continued, as a major, nationally networked publishing outlet for all kinds of literary and journalistic material. The political role of local newspapers and their proprietors has been passed over in these two chapters, largely because it has been dealt with so fully elsewhere.102 However, Hewitson was active in local and constituency politics for the Liberal party, and the political allegiance of each paper was important to their economic success. The local newspaper continued to be self-consciously three things at once – a commercial, cultural and political product. In the next chapter we will discover who read this apparently simple, but deeply complicated, artefact.

1 ‘This forenoon got notice to leave Preston Guardian as reporter. No specific cause could be assigned. I asked the proprietor and he said he could not lay his finger on anything in particular. He also gave me to understand that he had been informed I was going to start a general newspaper reporting agency and that he should be glad to employ me especially in that capacity when necessary’ (Hewitson Diaries, Lancashire Archives DP512/1/3, 30 November 1867).

2 Hewitson Diaries, 15 May 1872. For speculation on the three papers’ circulations, see ‘A fine farce — the two Preston papers “gone to the wall”, Correspondence, Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC) 8 November 1873, p. 6.

3 John Leng was able to save half his £2 weekly salary as chief reporter and sub-editor, amassing ‘a couple of hundreds of pounds’ by 1851: ‘Journalistic Autobiographies. I. Sir John Leng, MP, DL, Etc.’, Bookman, February 1901, p. 157.

4 Andrew Hobbs, ‘Reading the Local Paper: Social and Cultural Functions of the Local Press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855–1900’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Central Lancashire, 2010).

5 Hobbs PhD, Fig. 6: Some newspaper publishing connections, Preston, 1793–1893, p. 75.

6 Frederick G. Kilgour, The Evolution of the Book (Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 117.

7 PC, 23 December 1871. Robert Snape, Leisure and the Rise of the Public Library (London: Library Association, 1995), p. 83; For eighteenth-century newspaper proprietors and reading rooms, see Victoria E. M. Gardner, ‘The Communications Broker and the Public Sphere: John Ware and the Cumberland Pacquet’, Cultural and Social History 10 (2013), 533–57, https://doi.org/10.2752/147800413X13727009732164

8 Free Public Library report and accounts, 1879–1887, Harris Library T251 PRE.

9 See leader column, Preston Guardian (hereafter PG), 5 January 1878, p. 10, for example.

10 Jonathan Silberstein-Loeb, The International Distribution of News: The Associated Press, Press Association, and Reuters, 1848–1947 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 92, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139522489

11 Silberstein-Loeb, pp. 100–01.

12 The Journalist, 24 February 1900.

13 His evening paper had almost certainly lost money — it took another evening paper, the Sunderland Echo, eight years to go into profit: Maurice Milne, ‘Survival of the Fittest? Sunderland Newspapers in the Nineteenth Century’, in The Victorian Periodical Press: Samplings and Soundings, ed. by Joanne Shattock and Michael Wolff (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1982), pp. 193–223 (p. 204).

14 Andrew Hobbs, ‘Preston’s Nineteenth-Century Newspaper Wars’, Bulletin of Local and Family History, 5 (2012), 41–47.

15 Alan J. Lee, The Origins of the Popular Press in England: 1855–1914 (London: Croom Helm, 1976), p. 122.

16 Based on 43 presidents for whom information is available. Source: Henry Whorlow, The Provincial Newspaper Society. 1836–1886. A Jubilee Retrospect (London: Page, Pratt & Co., 1886).

17 Morning Post, 29 March 1875.

18 Graham Law, Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000), p. 42; Owen R. Ashton, W. E. Adams: Chartist, Radical and Journalist (1832–1906): ‘An Honour to the Fourth Estate’ (Whitley Bay : Bewick Press, 1991), p. 128.

19 J. H. Spencer, ‘Preston’s Newspapers: The Preston Guardian (continued)’, Preston Herald (hereafter PH), 18 June 1943; PG, 9 February 1887.

20 Howard Cox and Simon Mowatt, Revolutions from Grub Street: A History of Magazine Publishing in Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 18; Simon Eliot, Some Patterns and Trends in British Publishing, 1800–1919 (London: Bibliographical Society, 1994), p. 83.

21 Jennifer Phegley, ‘Family Magazines’, in The Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, ed. by Andrew King, Alexis Easley, and John Morton (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), pp. 276–92, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613345

22 Cox and Mowatt, p. 23.

23 ‘Death of Mr David Longworth’, PC, 13 October 1877.

24 For example, ‘Owd Bill Piper’ (1873), ‘Doses for the Dumps: A Series of Short Humorous Pieces’ (n.d.).

25 Anthony Hewitson, History of Preston (Wakefield: S. R. Publishers [first published 1883], 1969), pp. 343–44, pp. 343–44; Barrett’s Preston Directory, 1885.

26 The Preston Chronicle ceased publication in 1893; for details of content analysis, see Hobbs PhD, appendices, Tables A4, A7, A9.

27 The subsequent court case is reported in gleeful detail in a rival newspaper: ‘The fracas between an alderman and an editor: Charge of assault’, PH, 19 January 1884, p. 6.

28 PC, 5 January 1884, p. 5.

29 Victoria E. M. Gardner, The Business of News in England, 1760–1820 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2016), p. 163, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137336392

30 ‘The provincial journalists […] were somebodies in the town […] They were members of a community, and scribbled in our midst’: J. B. Priestley, ‘An Outpost’, in The Book of Fleet Street, ed. T. Michael Pope (London: Cassell, 1930), p. 179; see also Matthew Engel, ‘Local Papers: An Obituary’, British Journalism Review, 20 (2009), 55–58, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956474809106672 (p. 56) describing David Armstrong MBE, who edited the Portadown Times for forty years: ‘He knew every second person we passed, no, two in three probably.’

31 London, Provincial, and Colonial Press News, 16 May 1870, p. 25.

32 Kristy Hess and Lisa Waller, Local Journalism in a Digital World (London: Palgrave, 2017), pp. 8, 54, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50478-4

33 The Lancaster Guardian. History of the Paper, And Reminiscences by “Old Hands”, Published in Connection with Its Diamond Jubilee (Lancaster: E. & J. Milner, 1897), pp. 24–25, Lancaster Library.

34 W. H. Smith evidence to House of Commons, ‘Report from the Select Committee on Newspaper Stamps; Together with the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, Appendix, and Index’, 1851 (558) XVII. 1., paras 2830, 2832–33.

35 John O’Neil, The Journals of a Lancashire Weaver: 1856–60, 1860–64, 1872–75, ed. by Mary Brigg (Chester: Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1982), 23 April 1859, 8 July 1861, for example.

36 For example, ‘The Daily Telegraph may be had at half price the morning after publication, at [Lytham] Times office’: advertisement, Preston Pilot, 18 November 1885, p. 4; ‘Newspapers at half-price […] the day after Publication, punctually posted from a News Room,’ Liverpool advertisement listing some of the titles available, PC, 23 December 1865, p. 1.

37 Advertisement for John Proffitt, ‘hairdresser, news agent, &c &c’, PH, 1 September 1860, p. 4.

38 Geoffrey Nulty, Guardian Country 1853–1978: Being the Story of the First 125 Years of Cheshire County Newspapers Limited (Warrington: Cheshire County Newspapers Ltd, 1978), p. 9.

39 C. Y. Ferdinand, Benjamin Collins and the Provincial Newspaper Trade in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), p. 208.

40 Joseph Barlow Brooks, Lancashire Bred: An Autobiography (Oxford: Church Army Press, 1951), pp. 169–70.

41 Lancaster Guardian History, p. 25.

42 Dallas Liddle, ‘The News Machine: Textual Form and Information Function in the London Times, 1785–1885’, Book History 19 (2017), 132–68, https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.2016.0003

43 PG, 4 October 1884, p. 5.

44 Liverpool Lyceum annual reports, Liverpool Archives 027 LYC/17.

45 ‘A visit to a Lancashire heronry’, PC, 22 July 1882; ‘Notes On The Smaller Mammalia Observed Near Goosnargh’, PC, 9 December 1882; Standen obituary, Manchester Guardian, 18 March 1925, p. 11.

46 Law, Serializing.

47 Andrew Hobbs and Claire Januszewski, ‘How Local Newspapers Came to Dominate Victorian Poetry Publishing’, Victorian Poetry, 52 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1353/vp.2014.0008

48 Lee Erickson, ‘The Market’, in A Companion to Victorian Poetry, ed. Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman, and Antony H. Harrison (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2002), pp. 345–60; Sabine Haas, ‘Victorian Poetry Anthologies: Their Role and Success in the Nineteenth Century Book Market’, Publishing History 17 (1985), 51–64, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470693537

49 Natalie M. Houston, ‘Newspaper Poems: Material Texts in the Public Sphere’, Victorian Studies 50 (2008), 233–42, https://doi.org/10.2979/vic.2008.50.2.233

50 Andrew Hobbs, ‘History as Journalistic Discourse in 19th-Century British Local Newspapers’, Academia.edu (blog), 2016, https://www.academia.edu/27138940/History_as_journalistic_discourse_in_19_th_century_British_local_newspapers

51 Alan J. Kidd, ‘Between Antiquary and Academic: Local History in the Nineteenth Century’, Local Historian, 26 (1996), 3–14; Alan J Kidd, ‘“Local History” and the Culture of the Middle Classes in North-West England, c. 1840–1900’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 147 (1998), 115–38.

52 F. David Roberts, ‘Still More Early Victorian Newspaper Editors’, Victorian Periodicals Newsletter, 18 (1972), 12–26 (p. 23).

53 V. I. Tomlinson, ‘The Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society 1883–1983’, Transactions of the Lancashire & Cheshire Antiquarian Society, 83 (1985), 1–39.

54 The Tyldesley Diary: Personal Records of Thomas Tyldesley (Grandson of Sir Thomas Tyldesley, the Royalist) during the Years 1712–13–14, ed. by Joseph Gillow and Anthony Hewitson (Preston: A. Hewitson, 1873), https://archive.org/details/tyldesleydiaryp00attigoog

55 Hewitson Diaries, 22 February 1872.

56 The COPAC catalogue includes the British Library, the national libraries of Scotland and Wales, and the libraries of most UK research universities.

57 Franco Moretti, ‘Conjectures on World Literature’, New Left Review, 1 (2000), 54–68.

58 For another approach to this issue, see Mark Hampton, ‘Journalists and the “Professional Ideal” in Britain: The Institute of Journalists, 1884–1907’, Historical Research, 72 (1999), 183–201, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2281.00080

59 There is no survey for this period equivalent to the excellent Roberts, ‘Still More’, but see Derek Fraser, ‘The Editor as Activist: Editors and Urban Politics in Early Victorian England’, in Innovators and Preachers: The Role of the Editor in Victorian England, ed. by Joel H. Wiener (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1985).

60 ‘History of Chess in Preston’, PC, 21 January 1893; Stuart Johnson Reid, Memoirs of Sir Wemyss Reid, 1842–1885 (London: Cassell, 1905), p. 81; see also William Donaldson, Popular Literature in Victorian Scotland: Language, Fiction, and the Press (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1986), pp. 5–6.

61 Frederic Carrington, ‘Country Newspapers and Their Editors’, New Monthly Magazine, 105 (1855), 142–52 (p. 149).

62 Hewitson Diaries, 5 January 1872.

63 Anon., ‘A Chapter On Provincial Journalism’, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine, July 1850, 424–27.

64 [Edward Dicey], ‘Provincial Journalism’, Saint Pauls Magazine, 3 (1868), 61–73.

65 Handbill announcing Hewitson’s ownership of the Preston Chronicle, Community History Library, Preston.

66 Ivon Asquith, ‘The Structure, Ownership and Control of the Press, 1780–1855’, in Newspaper History from the Seventeenth Century to the Present Day, ed. by David George Boyce, James Curran, and Pauline Wingate (London: Constable, 1978), p. 114.

67 Christopher Kent, ‘The Editor and the Law’, in Innovators and Preachers: The Role of the Editor in Victorian England, ed. by J. H. Wiener (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1985), p. 101; A Conservative Journalist, ‘The Establishment of Newspapers’, National Review, 5 (1885), 818–28.

68 ‘Mr George Toulmin and the Preston Election’, Lancashire Daily Post, 2 October 1900, p. 2.

69 Hobbs PhD, appendices, pp. 15–28.

70 Anon., ‘Chapter’, p. 425; Dicey, p. 66.

71 Hewitson Diaries, 23 April 1872; 9 April 1868; 27 June 1896.

72 His choice of church was partly dictated by commercial considerations (he left the Unitarians in disgust after they gave their printing work to a Methodist, despite Hewitson having published their ‘very heterodox’ sermons in his paper), and perhaps also because Preston’s Nonconformists lacked political clout: Hewitson Diaries, 11 April 1875; 1881 passim; Paul T. Phillips, The Sectarian Spirit: Sectarianism, Society, and Politics in Victorian Cotton Towns (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), p. 46.

73 ‘The fracas between an alderman and an editor: Charge of assault’, PH, 19 January 1884, p. 6.

74 Hewitson Diaries, 10 February 1872; 4 December 1872.

75 Roberts, ‘Still More’, p. 12; Mortimer Collins, ‘Country Newspapers’, Temple Bar, 10 (1863), p. 136; Joseph Hatton, Journalistic London: Being a Series of Sketches of Famous Pens and Papers of the Day (London: Routledge/Thoemmes, 1882), p. 28; Maurice Milne, ‘Periodical Publishing in the Provinces: The Mitchell Family of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne’, Victorian Periodicals Newsletter, 10 (1977), 174–82.

76 Dicey, p. 66.

77 James Mussell, ‘“Characters of Blood and Flame”: Stead and the Tabloid Campaign’, in W. T. Stead, Newspaper Revolutionary, ed. by Laurel Brake and others (London: British Library, 2012).

78 Victoria E. M. Gardner, ‘The Communications Broker and the Public Sphere: John Ware and the Cumberland Pacquet’, Cultural and Social History, 10 (2013), 533–57, https://doi.org/10.2752/147800413X13727009732164

79 Joel H. Wiener, The Americanization of the British Press, 1830s-1914: Speed in the Age of Transatlantic Journalism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 4, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230347953

80 Joel H. Wiener, ‘How New Was the New Journalism?’, in Papers for the Millions: The New Journalism in Britain, 1850s to 1914, ed. Joel H. Wiener (London: Greenwood, 1988), pp. 47–72.

81 Tony Nicholson, ‘The Provincial Stead’, in W. T. Stead: Newspaper Revolutionary, ed. by Roger Luckhurst and others (London: British Library, 2012), pp. 7–21.

82 ‘Alleged libel case’, PC, 14 March 1874, p. 3.

83 Wiener, ‘How New?’; Laurel Brake, ‘The Old Journalism and the New: Forms of Cultural Production in London in the 1880s’, in Papers for the Millions; John Tulloch, ‘The Eternal Recurrence of New Journalism’, in Tabloid Tales: Global Debates over Media Standards, ed. by Colin Sparks and John Tulloch (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), pp. 131–46.

84 Dallas Liddle, The Dynamics of Genre: Journalism and the Practice of Literature in Mid-Victorian Britain (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009), p. 5.

85 Liddle, Dynamics, p. 2.

86 “Our Interview with Dr. Alfred Taylor,” Illustrated Times Supplement, 2 February 1856, p. 91.

87 Wiener, Americanization, p. 149.

88 Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, Vol. 3: 1865–85 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1938), p. 272.

89 Andrew Hobbs, ‘The Provincial Nature of the London Letter’, in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Vol. 2: Expansion and Evolution, 1800–1900, ed. by David Finkelstein (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018).

90 1851 Newspaper Stamp Committee, Q613.