6. Who Read What

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.06

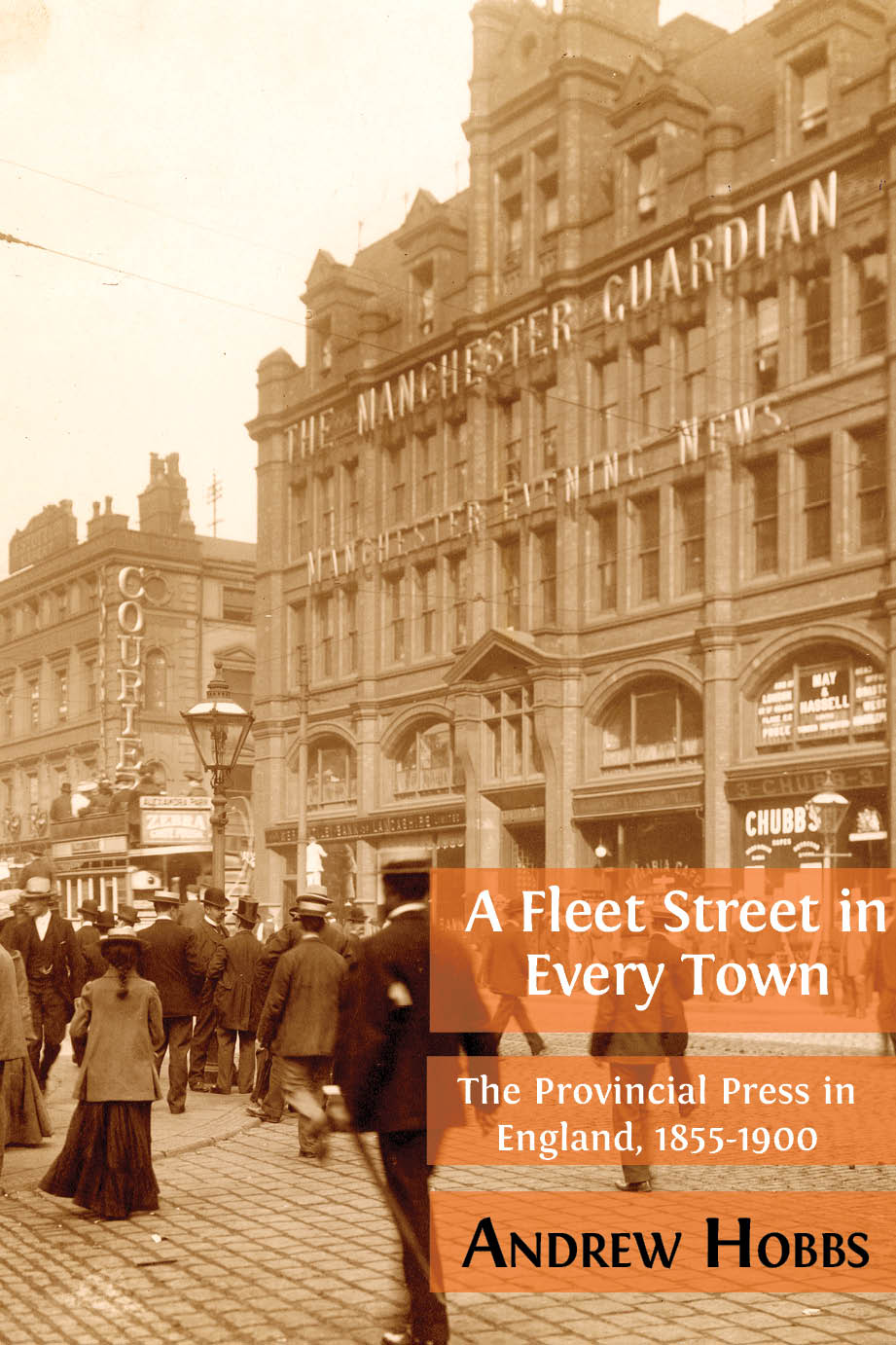

Fig. 6.1. Advertisement for Cowper’s Penny News & Reading Room, Preston (Preston Chronicle, 30 September 1854, p. 1, from 19th-Century British Library Newspapers database). © The British Library Board.

In 1854, the local newspaper was too expensive for most people in Preston. The three local papers each cost 4½d. But people could still read them — or listen to them being read — without buying them, in pubs, commercial news rooms like Cowper’s in Preston (Fig. 6.1 above) and mutual improvement society reading rooms. This chapter brings together the evidence used in previous chapters to argue that, cheap family magazines aside, local and regional newspapers were more widely read and purchased than those produced in London, with the local weekly the most popular type of Victorian newspaper. It also investigates the influence of social class and gender on preference for local papers. Discovering what the majority of Victorians read helps us to discover who they were.1

The local newspaper was popular, but national magazines were more popular. Half of the population of Britain read penny weekly magazines like the London Journal, Family Herald, Reynolds’s Miscellany or Cassell’s Illustrated Family Newspaper in the first half of the 1850s.2 In Preston, these penny magazines topped the list of reading matter for ‘factory hands’ in two bookshops in 1854, investigated by the Rev John Clay, the Preston prison chaplain and social reformer lampooned by Charles Dickens in Hard Times.3 The numbers of magazines and ‘penny dreadfuls’ sold from these two shops alone were greater than the combined circulation of two Preston papers put together (one shop was a wholesaler, but its territory was unlikely to have been as wide as that of the local papers). This balance between magazines and newspapers changed rapidly as the end of newspaper taxation brought down their prices.

The nature of public reading places like Cowper’s penny reading room exposed readers to a large number of publications, and to a wide range of political and religious viewpoints. As Thomas Wright, the ‘Journeyman Engineer’, wrote in 1876:

At present a working man with a taste for reading will in the course of a week glance through a score of papers — not to speak of periodicals — lying on the tables of the “Institution” to which he belongs […] [Previously] he would probably have had to be content with a single weekly paper, for which he would have to pay treble the amount of his weekly subscription to a modern institution.4

Cowper’s penny news room listed 24 titles in the advert above (Fig. 6.1) in 1854, while the ‘free’ (public) library in Barrow-in-Furness provided a staggering 195 titles in 1888.5 Preston’s free library stocked 48 publications plus ‘local papers’ in 1879, rising to 81 titles the following year and 171 by 1900. In virtually all public reading rooms and news rooms, the number of publications increased, a sign of growing demand, growing literacy, and growing supply. More working-class rooms carried more local titles, such as Newcastle Mechanics’ Institute, which offered 13 regional or local newspapers and eight London papers. By contrast, in 1869 the more middle-class Preston mechanic’s institute, known as the Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge, offered 49 magazines, 11 London papers, 10 regional or local papers and 9 trade or technical titles. Church reading rooms offered only a small selection of papers and magazines, such as ‘the London and Manchester daily and weekly papers, the local papers, Household Words, the Leisure Hour, Family Economist, &c &c.’ intended for a reading room at St Paul’s CE school, Preston in 1856.6 Public libraries such as Preston’s had the greatest number and variety of titles, from the Anti-Vivesectionist to the Westminster Review, the academic philosophy journal Mind to the women’s magazine Madame.

The readers who created and used each news room decided (directly or indirectly) the titles taken there. Cowper’s advert in Fig. 6.1 suggests a Nonconformist and Radical clientele; some pubs probably had particular political, cultural or religious affiliations, which might dictate the newspapers available. The reading matter was usually chosen by the members, although publications in rooms with clear religious or political agendas may have been selected by clergymen and ward committees rather than the readers, and local authority library committees controlled public libraries. In 1853 James Hole claimed that working-class news rooms’ selection of papers did not give both sides of the argument, unlike middle-class mechanics’ institutes.7 A speaker at the opening of a reading room established by the Preston Branch of the National Reform Union (Liberal party) in 1867 hoped that the Liberal Times and the Tory Standard would both be available, ‘as he was always desirous of seeing both sides of the question.’8 Nevertheless, in most public rooms, readers would be confronted by newspapers and magazines of opposing viewpoints. Birmingham librarian J. D. Mullins, writing in 1869, believed that the range of opinions available in free library news rooms was educational, and that ‘the opinion of a man of one newspaper —who gets all his information from one side — is not worth much.’9 A significant proportion of readers’ letters to local papers were responding to other newspapers, usually of opposing politics, suggesting that many readers were exposed to a range of opinion (see Chapter 10). However, for many, papers with disagreeable politics may have been read only reluctantly. For example, a letter to the Preston Chronicle in 1869 complained that there were thirteen Liberal newspapers and only one Conservative title in the Exchange and Newsroom. Worse, ‘most of the Radical journals are in duplicate, so that if one enters the room tired, and desirous of reading a paper while seated, nothing but a red-hot Radical effusion is get-at-able’ (an exaggeration but in 1868 there were indeed twice as many Liberal as Tory titles available there).10

It is not easy to answer the question, ‘who read what?’ particularly at the level of the individual. The lack of evidence means that most of this chapter makes generalisations about broad groups of people, but occasionally there are glimpses of individual readers. John O’Neil (b. 1810), the Clitheroe weaver, recorded in his diary the news he read in the papers, but, without thought for twenty-first-century newspaper historians, he rarely mentioned the name of the paper.11 From 1856 to 1861 he walked a mile into Clitheroe every Saturday evening to read the newspaper(s) at the Castle Inn. From occasional references to local news, these were probably weekly papers from Blackburn, Burnley and Preston, the nearest publishing centres (Clitheroe’s first newspaper only launched in 1884). Occasionally he saw a daily paper, such as the Manchester Times and Examiner of 14 June 1856, with news of that morning’s execution of William Palmer, the Rugeley poisoner. He sometimes received local papers from his home town of Carlisle, sent by his brother. He never mentions London newspapers. In 1861 his reading habits changed: ‘I have joined the Low Moor Mechanics’ Institute and Reading-room. It is a penny per week, so I will see a daily paper regular’ (2 December 1861). Unfortunately he does not give the names of any papers taken at the Mechanics’ Institute, and no records survive, although by 1866 the reading room took four daily and three weekly papers, ‘besides other periodicals’, according to the Preston Herald.12 Naturally, O’Neil began to read newspapers more often, and when a Liberal club and news room opened in Clitheroe in 1872, he was soon walking there almost every other day to read newspapers. He occasionally read at home — either a paper sent to him from Carlisle or a Lancashire one he bought himself — but did most of his reading in pubs and reading rooms. O’Neil’s reading matter was mainly local and regional — we can reasonably surmise that in the 1850s he read local weeklies, and from the 1860s onwards he saw regional dailies more often.

The Rev John Thomas Wilson (1837?–1910), vicar of Wrightington near Wigan, was less avid in his newspaper reading, and less radical in his politics. Between 1876 and 1883 his friend John Worsley of Fishergate, Preston, a surgeon-dentist, sent him newspapers, sometimes every day. These included the Manchester Evening News (Liberal) and Manchester Evening Mail (Conservative), the Tory London Standard, the Graphic illustrated weekly paper and the Liverpool Mercury (Liberal), all of which the vicar appreciated, particularly for their news of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78).13 Wilson also bought papers himself, at least when they reported his parish activities, including the Chorley Guardian, an unnamed Wigan paper and other local papers.14 He asked his dentist friend to send a copy of the Manchester Courier when it mentioned his parish. Wilson was not local — he was born at Windermere in the Lake District (where his father had been a friend of Wordsworth), and studied at Durham University, although he must have had some attachment to his rural Lancashire parish, staying there for forty-three years.15 However, this non-native professional middle-class graduate read local and regional newspapers.

Joseph Barlow Brooks (1874–1952) was another working-class reader with radical views. He began work as a half-time weaver in Radcliffe near Bolton, Lancashire, at ten, advancing to cashier in the same mill before entering the Methodist ministry at twenty-one. His autobiography describes a house full of newspapers and magazines in his teenage years and early twenties, during the 1880s and 1890s, when he, his brother and mother bought the Radcliffe Times and the Bury Times (two local papers); the Manchester Weekly Times (a regional news miscellany), the Cotton Factory Times (also a news miscellany, known for its dialect writing, aimed at cotton workers), and the Clarion (Robert Blatchford’s populist socialist weekly, ‘crammed full of fearless, vivacious and well-written articles on books, men and things’) — all three published in the Manchester area (the Clarion moved to London in 1895). In answer to his mother’s grumbles about the amount of reading, his brother would say:

“But mother, th’ Clarion gives yo’ some good stuff. Blatchford’s writin’s literature, an’ Bloggs an’ Bounder an’ th’ others are fine. An’ yo’ wouldn’t miss th’ Cotton Facthery Times for anythin’, especially Professor Spoopendike an’ ‘is Club!” Sam would argue. It was Professor Spoopendike’s request that brother So-and-so should remove his feet from off the stove and allow the heat to circulate round the room that served as a stock joke in the family for several years.16

There was also the Liberal, Nonconformist, middle-brow British Weekly. All were delivered to their house every Saturday. Brooks bought second-hand copies of the Review of Reviews (which ‘gave us something of a world outlook’) and other weeklies from the Co-op reading room, delivered every quarter for ‘a shilling or so’.17 Local and regional newspapers are highlighted in the memoir of this working-class man, some with a Liberal or socialist slant.

Before we examine the readership of each type of newspaper, a word on sources and methods. Evidence of individual readers such as the three men above is rare, but valuable in helping us to tie together the partial evidence of reading on the one hand, and buying on the other. Total sales of any publication tell us little about sales or readership in one place. Sales or availability of particular titles in one shop tell us nothing about sales in another shop, serving a different part of town, or run by a newsagent with opposing politics, nor about postal subscriptions nor distribution through membership organisations such as the co-operative movement or churches; the titles available in public reading places are strongly influenced by the particular locale, clientele and policies of those who control that reading space.

This chapter uses lists of publications available in news rooms and reading rooms (from annual reports and committee minutes), sales figures gathered by investigators during the period, the record of one retail newsagent, oral history interviews with people born in the 1880s and later (conducted in the 1970s and 1980s), marketing claims by newspaper publishers, contemporary comment by writers and journalists, newspaper reports of discussions of newspapers, and other less circular evidence. All are partial and problematic in their own ways, but most tell the same story, of the wide readership of the local paper. Lists of titles in news rooms have been tabulated and classified according to type of publication. I started from the categories of Alvar Ellegard in his ground-breaking 1957 study of mid-Victorian newspaper and periodical readership, but split some of his categories, for example London general weekly newspapers and London Sunday papers, and combined others, such as ‘fortnightly/quarterly reviews’ and ‘weekly reviews/newspapers of review type’; ‘religious quarterly reviews’ and ‘religious periodicals’, and monthly and weekly magazines. I created new categories of trade/business/technical/scientific magazines, local weekly newspapers, local evening newspapers, regional weekly newspapers and regional morning newspapers.18 The disputed borderlands between newspaper, magazine and periodical have been left unmapped in this project of examining the geographical origins of what was read.19

The surviving lists are sporadic, and not always recorded in the same way. Some publications were given to public library news rooms by publishers, particularly those promoting minority political and religious views; local publications were also sometimes ‘presented’ in this way, rather than purchased, but numbers of titles and copies of local papers remained the same regardless of whether they were bought by the news room or presented by the publisher, suggesting that this practice has not distorted the evidence.20 However, the wide variation between the titles available in different news rooms at different times shows how distinctive reading communities could be, in different places and times — with location more significant than era.

Provincial Preference

A handful of London newspaper titles had always sold more than the hundreds of provincial titles put together, but this situation was reversed in less than a decade after the Newspaper Stamp became an optional postage charge (rather than a compulsory tax) in 1855. In 1854 roughly twice as many London papers were sold as all the English provincial papers put together, according to the government’s Stamp Duty returns, with 64.7 million stamps issued to London papers and 25.4 million issued to provincial papers.21 But by 1864, papers published outside London were outselling London papers, according to figures gathered by Edward Baines, MP and publisher of the Leeds Mercury (Table 6.1 below). Baines’s rhetorical purpose was to argue that these readers deserved the vote, rather than any comparison between provincial and metropolitan newspaper sales; this, and his information sources, make the figures fairly reliable.

Table 6.1. Metropolitan versus provincial newspaper sales, 1864, United Kingdom and Ireland.22

|

2,263,200 per week |

|

|

3,907,500 per week |

|

|

248,000 per day |

|

|

439,000 per day |

Ten years later in Manchester, sales of Manchester newspapers outstripped London titles, according to wholesale newsagent Abel Heywood and author John Nodal. Their figures suggest that the city’s own publications (both newspapers and magazines) sold thirty-nine million copies per year in the city and its environs. While no directly comparable figure is given for non-Manchester publications, they sold substantially less, with a total of seventeen million copies per year for cheap weekly papers, higher-class magazines, family magazines, penny miscellanies, shilling magazines, Chambers’s Journal, All The Year Round, children’s magazines and penny dreadfuls.23 No figures are given for London daily papers, but Heywood believed that, despite their increased sales, if the numbers of London papers sold in Manchester in 1851 were doubled or trebled, ‘they will not approach the numbers of the London dailies now circulated here, and are a mere nothing compared with the present circulation of the Manchester papers’.24

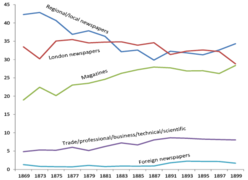

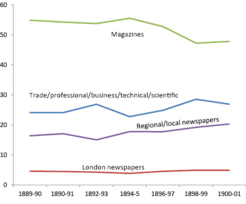

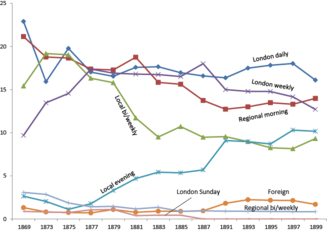

Newspaper sales are one thing, numbers of readers another, yet both types of evidence agree after 1855. Lists of newspapers taken in news rooms and reading rooms around the country also find a preference for local and regional newspapers rather than London newspapers — even before 1855, suggesting that provincial papers may have had more readers per copy than London papers. Table 6.2 opposite shows the proportions of different types of publication in different news rooms. In every news room, more regional or local papers are available than London papers, suggesting they were more popular. Even in middle-class mercantile rooms like the Liverpool Lyceum, regional and local newspapers were more popular than London papers for most of the last three decades of the century (apart from some years in the 1880s). Fig. 6.2 below summarises the lists of newspapers and magazines from annual reports. These subscription or membership news rooms could only survive financially if they were in tune with members’ preferences. The Lincoln Co-op room is the only exception, but even in Co-op reading rooms, it is likely that ideology or an ‘improving’ mission had to compromise with reader preference. In the Halifax Working Men’s Club and two mechanics’ institutes (Bury Athenaeum and Preston Institute) magazines outnumbered newspapers, but everywhere else, newspapers were more popular. The growing popularity of magazines can be seen in the two 1898 lists and in the records of the Liverpool Lyceum (Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 6.2. Type of publication as percentage of copies available at Liverpool Lyceum, 1869–99.25

Table 6.2. Type of publication in selected news rooms as percentage of titles available, 1854–98.26

|

Trade / professional / business / technical / scientific |

||||

|

43 |

21 |

36 |

||

|

55 |

25 |

16 |

4 |

|

|

19 |

14 |

52 |

14 |

|

|

33 |

18 |

30 |

18 |

|

|

14 |

12 |

61 |

12 |

|

|

53 |

27 |

13 |

7 |

|

|

39 |

28 |

22 |

11 |

|

|

62 |

33 |

5 |

||

|

18 |

12 |

55 |

15 |

|

|

28 |

25 |

37 |

11 |

|

|

Total |

364 |

215 |

327 |

92 |

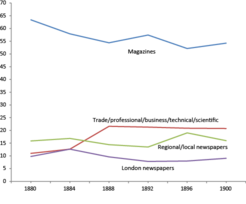

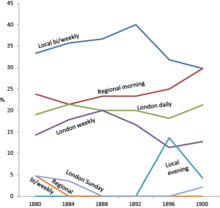

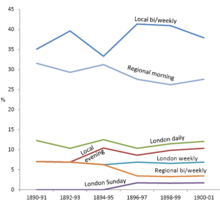

Almost all Preston reading rooms preferred provincial papers to London papers. Magazines were more popular than newspapers in the Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge (a largely middle-class mechanics’ institute which admitted women and men) in the 1850s and 1860s, but local and regional newspapers outnumbered London papers by sixty-two to fifty-one titles. The businessmen of Preston’s Exchange Newsroom preferred newspapers to magazines (Table 6.2) and provincial papers to London papers in the late 1860s and early 1870s (one member reported that the uncut pages of the Athenaeum showed that it was ‘not appreciated’ and it was no longer taken in 1874.27 But the more working-class and mixed-sex readership at the town’s free (public) library preferred magazines to newspapers, both general leisure magazines and specialist trade, professional, business, technical and scientific titles (Fig. 6.3). Here again, local and regional newspapers were more popular than London papers. In the Barrow-in-Furness public library reading room in north Lancashire, leisure magazines featuring fiction were also the most popular type of reading material, but again provincial papers were far more popular than London papers (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.3. Type of publication in Preston Free Library reading room as percentage of publications available, 1880–1900.

Fig. 6.4. Type of publication in Barrow Free Library reading room as percentage of titles available, 1889/90–1900/01.

Magazines and newspapers took precedence over books in the nineteenth-century public library. Free news rooms were specifically mentioned in the 1850 Public Libraries Act, revealing their importance to the free library ethos, and in Manchester, ‘the newsroom was generally more popular than the book rooms by a ratio of two or even three to one’.28 Newspapers were still central to public libraries in 1902, when Fulham librarian Arnold G. Burt wrote that ‘the popularity of a Public Library depends to a very large extent upon its news-room’.29 News rooms were given separate billing in the title of the standard work Free Libraries and Newsrooms: Their Formation and Management, first published in 1869. Its author, John Davies Mullins, head of Birmingham’s public library, suggested how to arrange a single-floor library, giving half of the public area to newspapers, the same space as for books and periodicals combined. While newspapers take up more table space, this still shows their importance to public library users.30 The newspapers, magazines and reference books were public attractions, while the lending library sent its users back to domestic spaces, according to Thomas Wright, the ‘Journeyman Engineer’:

The reading of the current newspapers and periodicals is of necessity carried on in the reading-rooms of institutions; but the reading of books, the more standard reading, is for the most part home-work — a labour of love in which each man indulges by his ain fireside.31

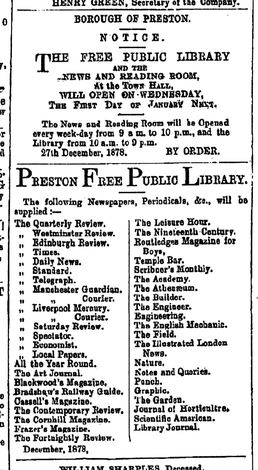

Three years after Wright’s comment, in 1879, Preston’s first public library opened in a room in the town hall. The advertisement in Fig. 6.5 does not mention books, suggesting that newspapers and periodicals were the main attraction. In 1892 a visit to some of London’s local public libraries still found news rooms well used, and more popular than other parts of the libraries. One small library was operating from ‘three or four rooms in an ordinary house, and affording an adequate supply of newspapers and periodicals, but with only a limited store of books.’ Newspapers were also foregrounded in Kensington library, and in Hammersmith, where a ‘handsome room, pleasantly overlooking lawns and flower-beds, is devoted to newspapers, and is well filled with readers at whatever hour it may be visited.’32

The 1879 edition of Mullins’s guide to running a public library listed the newspapers that every library news room should offer, beginning with the London dailies: ‘Times, Pall Mall Gazette, Daily News, Standard, Daily Telegraph; and the Local Papers of course […]’ Those two words ‘of course’ (which often appear in oral history interviews) tell us that the local paper was ubiquitous, almost necessary.33 And among local papers, the most popular type was the weekly.

Fig. 6.5. Advertisement announcing opening of Preston Free Public Library, 1879 (PC, 28 December, 1878, from 19th-Century British Library Newspapers database). © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

Local weeklies

‘It has been a great mistake […] to suppose that the daily papers are the papers most interesting to those who are permanently resident in distant local districts,’ Westminster Review editor and social reformer William Edward Hickson told the 1851 Newspaper Stamp Committee. ‘I find even with myself coming to London occasionally only as I do now, that I really take more interest in the “Maidstone Gazette” than I do in the “Times” paper, though I read both.’34 Hickson was a partial witness who opposed newspaper taxes, but the defence of the local press was not part of his agenda. His point, that working-class readers tended to read local weeklies like the Maidstone Gazette more than London dailies like the Times, is borne out by other evidence, before and after the abolition of the newspaper taxes. Hickson’s comment was made when weeklies and bi-weeklies were the only type of provincial newspaper, but even after the creation of regional dailies and, later in the century, local evening papers, the weekly paper remained popular.

Table 6.3: Type of newspaper in selected news rooms as percentage of newspapers available, 1854–98.

|

Local bi / weekly |

Regional morning |

Regional bi / weekly |

Local evening |

||||

|

22 |

67 |

11 |

|||||

|

22 |

57 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

29 |

29 |

29 |

14 |

||||

|

25 |

25 |

36 |

14 |

||||

|

25 |

20 |

25 |

5 |

25 |

|||

|

25 |

33 |

33 |

8 |

||||

|

31 |

17 |

43 |

9 |

||||

|

35 |

10 |

40 |

15 |

||||

|

26 |

18 |

18 |

15 |

15 |

9 |

||

|

24 |

15 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

12 |

6 |

Like the provincial merchants of earlier times, the users of these business-oriented news rooms may have subscribed to one or two local papers at home, but this news room supplied the latest commercial information from scores of different sources — information that was not available in such detail via London papers. This information was found in lists, tables, commentaries, analysis and news reports, but also in advertisements, for property, auctions, sales of cargo, arrivals and departures of ships, and tenders for goods and services.35 Local weeklies were also the most popular type of newspaper for working-class readers in the public libraries of Preston and Barrow throughout the 1880s and 1890s (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6), and in Lincoln’s Co-op reading room in 1898. Lincoln contrasts with Bury’s more middle-class Athenaeum reading room, where London dailies were the most popular type of paper. In the working-class Halifax news room in 1864, local weeklies vied with morning newspapers from London and provincial cities, while in the

commercial news room at Darlington in 1870, local weeklies were equal in popularity to provincial morning papers, probably for the same business reasons as in Liverpool in 1856.

Fig. 6.6. Types of newspaper available in Preston Free Library reading room, 1880–1900, as percentage of all newspapers available in each year.

Fig. 6.7. Types of newspaper available in Barrow Free Library, 1888/89–1900/01, as percentage of all newspapers available in each year.

A rare glimpse of a newsagent’s weekly newspaper sales in the East Lancashire town of Bacup in 1860 confirms that the local weekly was the most popular type of paper, particularly for working-class readers. No newspaper was published in Bacup in 1860 (1861 Census population 24,000), so residents relied on the ‘district news’ columns of papers produced in nearby towns. The Bury Times, published twelve miles away, provided the best Bacup news service, even though other papers were published in nearer towns, such as Todmorden, Rochdale and Burnley. The Bury Times published a list of the weekly newspapers sold the previous Saturday by a Bacup news agent, purportedly in response to a reader’s query (Table 6.4 below).36 This is very partial evidence; its main purpose is to persuade readers that this paper, the Bury Times, out-sells its rival, the Bury Guardian. This was almost certainly true, but whether the difference in sales (286 copies versus 8 copies in this particular shop) was so extreme is uncertain. The list is partial in other ways, excluding magazines and daily newspapers, and covering only one day. Some weekly papers may have sold more copies on other days of the week, or have been sent by post. However, the titles and quantities sold probably have some basis in fact.37 The list claims that almost half of all weekly newspaper sales are accounted for by one title, the Bury Times, as in the twenty-first century, when the local paper is usually sold from a pile on the counter, whilst less popular papers are displayed on shelves, in smaller numbers. Three quarters of the weekly newspapers sold in this shop are local or regional titles (Table 6.5 below). The list has a Liberal, even Radical flavour, with the only two Conservative titles, the Bury Guardian and the Manchester Courier, selling in small quantities. It was probably the shop of either Thomas Brown or Thomas Leach, booksellers and newsagents, both of whom were active in Parliamentary reform, and later became publishers in succession of the Bacup Times.38 There were four or five booksellers and ‘news-agents’ in Bacup in 1860, and others may have sold more Conservative papers.39 However, Bacup was a radical town, with a history of Luddism and Chartism, and this is reflected in the list of papers — most notably in the National Reformer, a newly launched republican, atheist journal of the National Secular Society, edited by Charles Bradlaugh.

Table 6.4. Weekly newspapers sold by a Bacup newsagent, Saturday 17 November, 1860.

|

Newspapers |

Copies sold |

|

1 |

|

|

Illustrated News of the World |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

Lloyd’s Newspaper |

2 |

|

Builder |

3 |

|

Illustrated Times |

4 |

|

Weekly Times |

6 |

|

Bell’s Life |

6 |

|

6 |

|

|

Todmorden Post |

6 |

|

Weekly Dial |

7 |

|

8 |

|

|

12 |

|

|

Alliance Weekly News |

13 |

|

14 |

|

|

16 |

|

|

19 |

|

|

Penny Newsman |

19 |

|

24 |

|

|

National Reformer |

24 |

|

28 |

|

|

34 |

|

|

45 |

|

|

286 |

When we classify these newspapers geographically (Table 6.5 below), we can see the dominance of the local weekly even more clearly. The top five titles, apart from the National Reformer, were all Radical papers which reported favourably on respectable working-class political and cultural activities, and therefore appealed to readers of that bent. The Bury Times and the Rochdale Observer both cost a penny, while the other three were twopence. The high sales of the second most popular weekly, the Preston Guardian, published twenty-eight miles away, confirm its status as a regional newspaper for the whole of North Lancashire. The Manchester Weekly Times was more populist and less radical than the Preston paper by 1860. The Rochdale Observer was a penny Radical local paper, like the Bury Times, but carried less Bacup news even though it was three miles closer. The Halifax Courier, published eighteen miles away in Yorkshire, may have been popular with Yorkshire ‘immigrants’ who had moved to Bacup, and for its news of the woollen trade.

Table 6.5. Type of weekly newspaper sold in Bacup newsagent, 1860.

|

Copies sold |

|

|

Local |

352 |

|

Regional |

111 |

|

81 |

|

|

38 |

|

|

Trade / professional / business / technical / scientific |

3 |

|

585 |

Multiple copies of the same title, presumably to meet demand, confirm that the local weekly was important to middle-class business readers. Table 6.6 below shows the titles requiring multiple copies in Preston’s Exchange Newsroom in 1868 and 1874. The three main Preston papers (Guardian, Herald and Chronicle) were the most popular when the news room opened in October 1868, with three copies each. However, only two copies each of the Preston titles were required in 1874, whilst the number of copies of papers from elsewhere was largely unchanged. This may be because of falling membership. The businessmen who used this room could afford to take one or two papers at home, but to keep abreast of prices, markets, tenders, auctions and other commercial news, they needed to see a wide range of papers. The three Preston weeklies were probably in particular demand on Saturday mornings, as soon as they were published.

Table 6.6. Publications with multiple copies, Exchange Newsroom, Preston, 1868 and 1874.40

|

Publications |

1868 |

1874 |

|

3 |

2 |

|

|

3 |

2 |

|

|

3 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

1 |

3 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

Standard |

2 |

2 |

|

Times |

2 |

2 |

Magazines were the most popular genre, but at the level of the individual publication, it was the local paper. Some economic theory can assist here. In the relatively small Preston periodical market, the choice of local papers was limited by the number of possible purchasers; the local paper as a product had a limited geographical market, and could not easily be traded across markets.41 The small number of local papers in any one market made each one an ‘independent good’, which could not be substituted by a similar product. For a national magazine, on the other hand, Preston was just one small part of a much bigger national market, with millions more possible purchasers. The larger market supported more competitor titles, creating more consumer choice; this made a national magazine a ‘substitute good’. In a Preston reading room, Reader A may want to read the Family Herald but Reader B already has it; however, Reader A will probably make do with a substitute title such as the London Journal, Reynolds’s Miscellany, the Leisure Hour or Household Words (although there is no substitute for the next episode of a serial novel!). But if Reader A wants a local Tory perspective on the local and wider world, there is probably only one substitute title, if that. Multiple copies are perhaps a clue to intensity or quality of demand, rather than quantity of demand. Of course multiple copies in a public reading place tell us nothing about private and family reading behaviour in the home, nor about purchasing behaviour. Paying money for one’s favourite newspaper or magazine, for which there is no substitute, is very different from reading in a public place, where one cannot expect to immediately lay hands on a favourite publication.

Local weeklies were the most popular individual titles in the free libraries of Preston and Barrow in the 1880s and 1890s, using numbers of multiple copies as a guide. Preston free library, opened in 1879, had in the order of ten times as many users as other news rooms in the town, and the widest social range of readers, so we can give more weight to this evidence of the reading tastes of the town as a whole. Here, whilst local papers were insignificant as a genre, accounting for around six per cent of serial publications available, they were the most popular individual titles, requiring up to six copies to meet reader demand (Table 6.7 below; single copies of the Preston Guardian were presented to the library free 1880–84, and single copies of the Preston Herald were given 1882–84, but this does not alter the ranking). In Barrow’s free library, the Barrow weeklies and evening paper also required the greatest number of multiple copies (Table 6.8).

Table 6.7. Publications with multiple copies, Preston Free Library, 1880–1900.42

|

Publications |

1880 |

1884 |

1888 |

1892 |

1896 |

1900 |

|

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

5 |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

|

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|||

|

4 |

1 |

|||||

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

||

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

1 |

|||||

|

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Graphic |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Queen |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Lady’s Pictorial |

2 |

2 |

Table 6.8. Publications with multiple copies, Barrow Free Library, 1889/90–1900/01.43

|

Publications |

1889–1890 |

1890–1891 |

1892–1893 |

1894–1895 |

1896–1897 |

1898–1899 |

1900–1901 |

|

3 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

||||||

|

North Western Daily Mail |

3 |

3 |

|||||

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

|||||

|

Fun |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Graphic |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Judy |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Co-operative News |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||

|

All The World |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Awake |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||

|

Young Soldier |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

War Cry |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

3 |

3 |

||||||

|

Son of Temperance |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Many readers had an emotional attachment to the local weekly, more than for other types of paper. A discussion, ‘The Blackburn Weeklies: Which is the best general newspaper?’ took place over three weeks at the Regent Hotel in Blackburn in August 1888; by comparison, a similar debate, on the local evening papers, lasted only a week. It was standing-room only and ‘the debate on the weeklies […] was declared one of the most popular and interesting subjects ever discussed at the Regent debates.’44 A Mr Stout argued that ‘the public to-day read the evening papers, got all the political news they wanted each night, and as a little interesting refreshment wanted the weekly papers to be journals of literature — social articles and local tales.’45 Other speakers agreed that this local non-news content marked out their favourite weekly, with a Mr Walton arguing in support of the Blackburn Weekly Express that ‘its original matter was unequalled in the district’.46 Similarly, Mr Moorfield said: ‘I have always found Lancashire people to be particularly jealous of their folklore and everything creditable to the [county] palatine, ranging from Pendle Hill to Tim Bobbin, and from Edwin Waugh’s poems to the ancient milk stone, situate at the boundary of the borough of Rochdale […] surely the “Local History” to be found in the Weekly Express must be most interesting and instructive to the majority of its readers.’47 In 1950, looking back at the success of the series of south-east Lancashire weeklies published from Bolton from the 1870s onwards, a company history made the same distinction between evening and weekly papers: ‘The Tillotson newspapers first secured entrance to the homes of the people by being a complete mirror of local life and events — industrial, religious, political, civic, social, sporting — in a way and to a degree which no evening paper could attempt.’48

The local weekly was still the most popular type of newspaper in towns without well-established evening papers, even at the end of the century, although the halfpenny local evening paper was spreading rapidly at this time. We know this from oral history interviews with people born in Barrow, Lancaster and Preston in the 1880s and later, all of whom were asked about reading matter in their childhood homes (Table 6.9 below).49 Local newspapers were the single most popular reading matter, as a genre and as individual titles, with two-fifths of Preston interviewees (twenty-four out of sixty) recalling a local paper being read at home, a third of Barrow interviewees (twenty-two of sixty-seven) and a quarter of Lancaster interviewees (fourteen of fifty-six). In the early twentieth century, Lancaster was the only one of the three towns not to have its own evening paper (although the Preston-based Lancashire Evening Post published a Lancaster edition). Consequently, almost equal numbers of Lancaster interviewees recalled a weekly or an evening paper (seven and six mentions respectively). We can only rely on broader trends in this oral history, rather than detail. The titles of publications mentioned in interviews reveal the chronological vagueness of oral history evidence. Although the tenor of the questioning was about childhood, some interviewees mentioned titles only published in their adulthood (although they may be using later titles to refer to earlier incarnations of papers whose names changed through amalgamations). These responses have been omitted from the analysis, but they show the complexity of what is happening during an oral history interview, and the consequent dangers of mining such material for factual information without ‘triangulation’ against other sources. It is likely that titles that survived were mentioned more often than those that were no longer published at the time of the interviews. Equally, the questioning reflects twentieth-century assumptions about newspaper reading — that it took place in the home rather than in public reading rooms — and limited knowledge of newspaper genres, for example the now-extinct regional news miscellany. The interview schedule included a question specifically about newspaper-reading, but there was no equivalent question about magazine-reading, which probably explains their under-representation.

Table 6.9. Working-class periodical reading material in Preston, Barrow and Lancaster, 1880s to 1920s.50

|

Category |

||||

|

Local evening |

19 |

13 |

6 |

|

|

Local weekly |

2 |

8 |

7 |

|

|

Local other |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Regional weekly |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

|

1 |

5 |

3 |

||

|

4 |

3 |

6 |

||

|

6 |

4 |

2 |

||

|

Sunday, unknown |

1 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

All Sundays |

32 |

|||

|

1 |

4 |

|||

|

4 |

8 |

3 |

||

|

5 |

6 |

4 |

||

|

Comic/children’s publication |

9 |

3 |

6 |

|

|

Religious |

3 |

4 |

2 |

Evening Newspapers

The huge growth in readership of the local evening newspaper, with its football scores and betting tips, was an unintended result of the high-minded abolition of newspaper taxes, the nationalisation of the telegraphs in favour of the provincial press, and free, compulsory education.51 By the end of the century, many halfpenny local evenings sold more copies in their town or city alone than the Times did across the whole nation. Bourgeois commentators deplored their popularity, but when working-class voices can be heard through the noise of middle-class judgments, they show a strong preference for this type of newspaper — cheap, local and (by the end of the century) in tune with popular working-class culture.

The first provincial halfpenny evening newspaper was probably Liverpool’s The Events (1855–57), closely followed by the South Shields Gazette (although the latter was merely a telegraphic sheet from 1855 until 1864).52 Other early titles, which survive to this day, included the Bolton Evening News (1867–), Manchester Evening News (1868–) and the Middlesbrough Daily Gazette (1869–). In London, Cassell & Co., keen watchers of the provincial newspaper market, launched the first London halfpenny evening paper, The Echo, in 1868. The first editions of these ‘evening’ papers appeared as early as 11am, with updated editions until early evening (Barrow public library provided three separate editions of the town’s evening paper, the North Western Daily Mail). They were usually four pages, of smaller dimensions than a morning paper. Before the 1880s, they contained telegraphed national and international news, items reprinted from other provincial papers, local news and adverts, some business news and occasional paragraphs of racing news. Some evening papers of the 1870s and early 1880s, such as the Aberdeen Evening Express or the Norwich Eastern Evening News, sometimes contained no sport at all. Instead, they were read for the latest news, especially during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78). The Rev Wilson, vicar of Wrightington, thanks his friend for copies of the Manchester Evening News and Manchester Evening Mail during the Russo-Turkish War and mentions the war news in particular.53

In Lancashire, most evening papers were launched in the 1870s, but this newspaper genre came into its own in the 1880s (Table 6.10). Many did not survive, despite the availability of cheap telegraphed news via the Central Press news agency from 1868 and the Press Association from 1870 onwards, and demand for war news. In 1876 Abel Heywood estimated that Manchester’s 2 evening newspapers sold a combined 45–50,000 copies each day.54 This figure probably rose sharply in the 1880s, when developments in sport stimulated — and benefited from — higher sales: more regular racing meetings, and the creation of the Football League, leading to frequent, scheduled sporting events which could be previewed beforehand and reported afterwards.55 In Blackburn, an early football centre, the Northern Daily Telegraph doubled its circulation from 20,000 to 40,000 between 1887 and 1888, with football news a big attraction.56 In Preston, perhaps less football-mad than Blackburn, the Lancashire Daily Post sold less — 38,000 copies per day by 1900.57

Table 6.10. Evening newspaper launches in Lancashire, by decade, 1855–98.

|

1850–59 |

2 |

|

1860–69 |

5 |

|

15 |

|

|

1880–89 |

7 |

|

1890–99 |

4 |

A halfpenny newspaper covering sport appealed mainly to working-class readers, perhaps particularly to working-class Conservatives.58 The favourite newspaper among Middlesbrough steel workers in 1905 was the ‘local halfpenny evening paper [the Evening Gazette], which seems to be in the hands of every man and woman, and almost every child,’ according to the social investigator Lady Bell, who interviewed workers employed by her husband.59 Bell was unlikely to exaggerate the ubiquity of the Liberal Evening Gazette, as it had defeated her husband’s attempted rival Conservative paper, the Middlesbrough & Stockton Sporting Telegraph five years earlier.60 The evening paper was the only reading matter for many families, Bell believed. Preston’s Lancashire Daily Post is mentioned more than any other single title in the oral history interviews in Preston, Lancaster and Barrow (nineteen mentions, compared to three for the next most popular title, the News of the World), while the most popular genre was the evening paper (thirty-eight mentions, see Table 6, additional online material). The story was the same in the St Helens area in 1904, where ‘evening papers are bought largely […] and it is to be feared that it is in respect to sport that they are most attractive’,61 and in 1880s London, where two evening papers, the Echo and the Evening News, ‘exclusively appeal to and are almost exclusively bought by the man who earns his livelihood by manual toil’.62 Evening papers begin to appear in the records of reading rooms from the 1870s onwards (Table 6.3 above), particularly in working-class rooms such as Lincoln and Newcastle. Their popularity can be seen in the multiple copies required in the Preston and Barrow public libraries (Tables 6.7 and 6.8). However, while the majority of evening newspaper readers were working-class, these papers also appealed to other readers — they grew as a proportion of the newspapers taken at the middle-class Liverpool Lyceum from two per cent in 1869 to ten per cent in 1899 (Fig. 6.8 below). Liverpool evening papers were in greater demand at the Lyceum than the Times by the late 1890s (twelve copies each in 1897 and 1899, compared to ten of the Times).

Regional News Miscellanies

The two most popular types of regional newspaper were weekly news miscellanies such as the Manchester Weekly Times or the Liverpool Weekly Mercury, aimed at working-class readers, and morning newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian and the Liverpool Daily Post, aimed at middle-class readers.

Graham Law’s superb work has established that the weekly news miscellany was one of the most popular types of newspaper from the 1860s until the First World War.63 It has received little scholarly attention, apart from Law, probably because it was provincial, is now extinct, and was a newspaper-magazine hybrid rather than a ‘serious’ political newspaper. This type of paper, described by Leigh in 1904 as ‘the weekly edition of daily papers published in large provincial cities’, was the most popular in the small town near St Helens (probably Sutton or Thatto Heath) that he surveyed:

One house in two takes at least one of these weeklies, and a strangely considerable number take two, owing to the curious fact that the man and wife, or the man and his eldest son, are not altogether in accord as to the preferable journal […] in spite of the existence of Sunday newspapers which add sport of all kinds to their contents, these Saturday weeklies continue to hold their own. Asked to state in a word what is the widest influence on the lives of artisan Lancashire, I should at once reply, “The weekly newspaper.”64

The Bacup newsagent’s list from forty-four years earlier, in 1860, confirms this preference for the Saturday news miscellanies over Sunday papers. The Manchester Weekly Times was the third most popular title sold in the Bacup shop, far ahead of London Sundays (early editions available on a Saturday in Lancashire) such as Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, Reynold’s News and the News of the World. As with evening papers, only low numbers of regional news miscellanies appear in the reading room records (one, the Liverpool Weekly Mercury, was auctioned at Barrow Working Men’s Club in 1870; only one Sunday paper, the News of the World, was auctioned that year); it may be that these cheap working-class titles were so ubiquitous in the home that there was little demand for them in public reading rooms, particularly by the end of the century. In the oral history memories from Preston, Barrow and Lancaster, mainly from the early twentieth century, Sunday papers were mentioned more often than regional Saturday miscellanies (five mentions for the miscellanies, thirty-one for Sunday papers, Table 6.9 above). Even here, regional preference was apparent, with Manchester titles such as the Sunday Chronicle recalled more often than London Sundays (thirteen to eleven). A Preston man’s brief memoir recalls his father ‘reading his favourite newspaper, the Sunday Chronicle. He loved to read aloud the most telling and eloquent passages of articles by a popular journalist of the period, Robert Blatchford.’65 The regional miscellanies’ rare mentions in the oral history interviews may be because interviewees had forgotten this extinct genre (one man, ‘S1P’, born in 1900, required two prompts before recalling an example, the Liverpool Weekly Post), while a copy of the local evening newspaper, the most common type of publication mentioned, was probably in the room during some of the interviews in the 1970s and 1980s. All the evidence suggests that the regional news miscellany was read mainly by working-class men and women, and was often their only paper. An 1871 appeal to advertisers for the Liverpool Weekly Mercury described it as ‘the best medium […] for Advertisers wishing to reach a vast number of readers who rarely see a daily newspaper, and who therefore peruse a weekly one all the more thoroughly.’66

Morning Newspapers

The regional morning newspaper was invented shortly before the abolition of compulsory newspaper stamp duty in 1855. Some, such as the Manchester War Telegraph and the de facto daily publication of the Manchester Examiner and Times in 1854, began in response to demand for Crimean War news. Others, such as the Liverpool Daily Post, launched as soon as the compulsory stamp duty was abolished in July 1855, making a penny daily an economic possibility. The Manchester Guardian went from bi-weekly to daily publication in 1855, the Liverpool Mercury in 1858 and the Leeds Mercury in 1861. These Liberal papers were followed by Conservative dailies such as the Liverpool Daily Courier (1863) and the Manchester Courier (1864).

Regional dailies quickly became more popular than London dailies. In 1864 Baines claimed that provincial dailies sold almost twice as many copies as London dailies. In Bradford in 1868, records from a W. H. Smith bookstall show that, as soon as two dailies were launched in the city, sales of provincial dailies (including those from Leeds and Manchester) overtook those of London dailies (Table 6.11 below). The Bradford Daily Telegraph launched on 16 July, probably causing the rise in provincial sales by September, and the Bradford Observer switched from weekly to daily publication on 5 October, leading to the further increase in provincial daily sales in December.

Table 6.11. Average monthly sales of London versus provincial newspapers, W. H. Smith bookstall, Bradford 1868.67

|

March |

June |

September |

December |

|

|

218 |

254 |

218 |

225 |

|

|

213 |

208 |

277 |

345 |

These papers were more popular than London papers because they contained more regional and local news, they reached the provincial breakfast table four or five hours earlier (until train times improved towards the end of the period), and their news was more recent, thanks to later press times made possible by their shorter distribution journeys. In 1872, an anonymous writer in the Quarterly Review explained that

[r]eaders who can get the Manchester Guardian, Leeds Mercury, or Birmingham Post at eight o’clock in the morning, with all the local news, in addition to everything of interest in the way of general intelligence, are not likely to care much for the Times or Telegraph at one o’clock in the afternoon.68

Most reading rooms provided provincial dailies from their own region only, with occasional exceptions (such as the Manchester Examiner taken in the Newcastle Mechanics’ Institute), suggesting that they provided something — unique material, perhaps, or a unique regional selection of material — unavailable in other papers.

As more regional dailies launched, their readership increased, largely among the middle classes, as seen in Preston’s public reading places. The Liverpool Daily Post and the Manchester Examiner, two of the first penny provincial morning papers, were staples of the Preston news rooms, alongside the Manchester Guardian, the Liverpool Mercury and the Leeds Mercury. Regional dailies were the most popular type of paper in all but the most exclusive reading places: at the mechanics’ institute (the Institution for the Diffusion of Knowledge) they were the most common type of newspaper, more popular than London or even local papers (but less popular than literary and technical magazines). At the Preston businessmen’s Exchange and Newsroom, provincial dailies were the most popular type of publication (seven titles in 1868, rising to nine in 1874), and two copies each of three Liverpool dailies (the Courier, Daily Post and Mercury) and two Manchester dailies (the Courier and the Examiner) were needed to meet demand. By 1874, the Manchester Guardian required three copies (one of them the second edition). At the free library, the number of provincial dailies rose from five in 1880 to thirteen in 1900, most of them from Manchester and Liverpool, and always outnumbering the London dailies. Regional dailies were equal in popularity to London dailies in the Halifax Working Men’s Club in 1864, and were the most popular type of newspaper in the Darlington Telegraphic Newsroom in 1870 and the Newcastle Mechanics’ Institute in the late 1870s.

Working-class people may have read regional morning papers in news rooms, but few bought them. O’Neil’s diary mentions reading a daily paper (almost certainly from Manchester) only occasionally in the 1850s, but by the 1870s he read one almost every day, in the Clitheroe Liberal club — but he did not buy a copy. In 1892 the Newcastle Daily Chronicle recalled its support for the region’s coal miners in the past, when they had ‘no spokesman but ourselves outside of their own class’, an admission that the newspaper was not a working-class paper. Even by the early twentieth century, Leigh found that near St Helens, ‘not one in a hundred of this vast community read a morning paper, even a halfpenny morning.’69

At the most exclusive news rooms, the Liverpool Lyceum and Preston’s Winckley Club, regional morning papers were less popular for most of the period. At the Lyceum, Liverpool dailies were at their most popular in the 1870s, when they required more multiple copies than London dailies — the Mercury, Courier and Daily Post all needed a dozen copies each, but the numbers of multiple copies fell by a half by the 1890s. Generally, they were less popular than magazines, London dailies or London weeklies, and declined as a proportion of all publications available at the Lyceum from seventeen per cent in 1869 to ten per cent in 1899. At Preston’s Winckley Club, the most significant change in the list of titles auctioned each year was the growth in the number of big-city provincial newspapers, from none in 1851 to five in 1856, after which the number stayed roughly constant. However, these penny provincial dailies supplemented but did not supplant the London dailies at the club.

Gentlemen preferred London dailies to regional dailies. At the Liverpool Lyceum, they accounted for fifteen to twenty per cent of all publications available, more than regional morning papers, which declined from twenty-one per cent of publications in 1869 to less than fourteen per cent in 1899 (Fig. 6.8 below). At Preston’s Winckley Club, ‘that mystic department of eau de cologne and exclusiveness’,70 they were the single most popular type of publications, increasing from eight to twelve copies in the second half of the century. An upper middle-class preference for London papers can also be seen in the correspondence of the Vicar of Wrightington, who mentions metropolitan titles nine times, compared to four mentions each for regional dailies and local weeklies.71 By the 1890s, London dailies were preferred in some less exclusive reading places, including the Bury Athenaeum and the Lincoln Co-op reading rooms (Table 6.3 above). In the same decade, London dailies, including the Daily Mail and the illustrated Daily Graphic, became more popular at the Liverpool Lyceum (Fig. 6.8), possibly because provincial papers such as the Liverpool Daily Post and Manchester Guardian were slower to adopt the ‘New Journalism’, preferring to follow the traditional Times model.

Fig. 6.8. Type of newspaper as proportion of all titles available,

Liverpool Lyceum, 1869–99.72

Old-fashioned or not, the Times was the most popular London paper in all reading places except pubs. In smaller rooms such as Colne Mechanic’s Institute (1854) and the Darlington Telegraphic Newsroom (1870), only two London titles were taken, the Times and the Radical Daily News. In medium-sized rooms such as the Preston Exchange (1860s–70s) and Newcastle Mechanics’ Institute (1870s) these two titles were supplemented by the Daily Telegraph and the Standard (a morning edition was launched in 1857), and the Daily Mail and Daily Graphic at the end of the century. Larger, more select news rooms such as the Winckley Club also took the higher-priced, smaller-circulation Morning Chronicle and Morning Herald (until their closure in 1865 and 1869 respectively), the Morning Post and the Morning Advertiser. In the Liverpool Lyceum, eighteen copies of the Times were needed to meet demand in 1869, falling to ten copies by the 1890s. One might expect members of a club like the Lyceum to have their own copy of the Times at home, which raises unanswerable questions about whether members would read the same paper at home and at their club, and the relative importance of the sociable atmosphere of the club and the reading matter. Many news room records remind us of the decentred Victorian newspaper map, on which London papers were not the default — even in the Winckley Club, the ‘London Times’ and the ‘London Daily Mail’ required a place name when recorded in the minutes in 1900, to avoid confusion with provincial papers with similar titles.73

The Times was less prominent in cross-class reading places such as the public library and the public house. Mullins, in his library management guide, recommended that free libraries should take the Times, Daily News, Standard, Daily Telegraph and Pall Mall Gazette (the latter, a London evening paper, was available in many news rooms, along with the Globe and the Echo).74 Mullins believed that these papers were read by ‘tradesmen and persons of small [private] income’75 in his Birmingham library, probably a similar readership to the Preston and Barrow public libraries. In Preston’s public library, London titles were always a minority of the daily papers available, even though they increased from four to ten between 1880 and 1900. No multiple copies of London dailies were required in Preston, nor in Barrow, in contrast to the multiple copies of three Manchester dailies, local weekly papers, evening papers from Barrow, Preston and Liverpool, and London magazines such as the Illustrated London News, Punch, Judy and Fun. Preston’s church and working-class news rooms always took ‘the London papers’ or included them among the ‘leading’ and ‘best’ papers. In the pub, it was the norm for at least one newspaper to be provided by the landlord even in smaller establishments, perhaps the Morning Advertiser, organ of the Licensed Victuallers Association (‘intensely respectable […] one of the few newspapers ever seen across the “bar”’), or a sporting paper such as Bell’s Life in London, while larger commercial hotels advertised the number of titles available.76 In the working-class home, London dailies hardly featured at all in the memories of oral history interviewees — they are mentioned four times by Preston interviewees, compared to twenty-one mentions of local papers.

Magazines and Specialist Publications

As with newspapers, the number of magazines, specialist publications and reviews taken in public reading places grew enormously. At Preston’s Winckley Club, magazines and reviews grew steadily from nine auctioned in 1851 to thirty-one in 1900, with growth particularly in comic, sporting and fiction-related titles. At Preston’s free library, magazines and reviews made up around eighty per cent of the serial reading matter between 1880 and 1900. As a genre, London magazines were mentioned nineteen times by Preston oral history interviewees, almost as often as local papers (twenty-one instances), but no title was mentioned more than once. Children’s comics and magazines were over-represented, revealing another limitation of these interviews, with their focus on childhood memories. When the Barrow and Lancaster interviews are included, only two individual magazine titles were remembered more than twice — John Bull, a conservative general-interest news miscellany, and the Catholic Fireside, a religious and general-interest magazine aimed at women and children, including serial fiction, and originally published in Liverpool.

The most popular non-news publications in all public reading rooms were the Illustrated London News and Punch, with the Punch imitators Judy and Fun close runners-up. In some places, such as the Darlington Telegraphic Newsroom, these were the only titles that were not newspapers (although where there were both news rooms and reading rooms, for newspapers and magazines respectively, records of only one of the two rooms can mislead). These titles were found across the social scale, from Barrow Working Men’s Club to Preston’s high-class Winckley Club; however, the single copy of the Illustrated London News sold in the Bacup newsagent’s in 1860 (Table 6.4 above) might suggest that, although such titles were widely read, they were actually purchased only by the middle classes. Working-class readers preferred the ILN’s cheaper illustrated rivals, the Illustrated Times (four copies sold at the Bacup shop) or the the Illustrated Police News (launched in 1864, so not recorded in the Bacup list). Richard Jefferies, writing in 1877, reported that this sensational paper, ‘with its cuts of savage murder, or awful explosions, finds its way largely even into the most outlying hamlets.’77 By the early twentieth century, newspapers with prize competitions and ‘periodicals filled with “snips and snaps”’ (probably the Daily Mail, Answers and Tit-Bits) were very popular in working-class areas of Manchester.78

The popularity of particular magazine genres and titles depended on the social class, occupations and gender of the reading room clientele. Public libraries, catering to everyone, supplied everything (so their records are therefore less revealing of individual reading behaviour). Shilling monthly magazines containing fiction, particularly Macmillan’s Magazine, Cornhill and Temple Bar, were available at mixed-gender middle-class institutions such as mechanics’ institutes, public libraries (mixed gender and mixed social class) and at exclusive gentlemen’s clubs. Dickens’s light and improving magazines and similar publications were popular with working-class readers such as the members of Preston’s Central Working Men’s Club, where Once a Week ‘and other good and healthy periodicals’ were available in 1864.79 In 1892 All The Year Round reported that ‘those who have been at work all day wade patiently through the monthly magazines and illustrated papers’ at an unnamed London public library.80 Chambers’s Journal and Cassell’s Magazine were the most popular penny weeklies containing fiction; Chambers’s had wide appeal, from male and mixed working-class rooms to the superior, men-only Liverpool Lyceum; Cassell’s appealed to working-class men and middle-class men and women, but not to the upper middle-class men of the Liverpool Lyceum and Preston’s Winckley Club (the Winckley Club had no penny weeklies at all). Temperance magazines and newspapers were widely available (in the public libraries of Preston and Barrow, in Barrow Working Men’s Club and in Halifax and Preston mechanics’ institutes), although some were supplied free.81 The most popular were the Alliance News and the beautifully illustrated British Workman. Even in the more sophisticated Liverpool Lyceum, one temperance title, the Alliance News, was available in the 1870s (not a single temperance publication was available in the rakish Winckley Club). Literary reviews were available in all but the working-class rooms, although some working men read them at the public library; about a dozen were observed taking ‘a hurried glance at the monthly reviews’ in a branch library near St Helens, their only use of the library.82

Public libraries supplied more women’s titles, and more specialist and technical publications, than other public reading places (in fact, more of everything). In 1880 Preston library stocked one women’s magazine, by 1900 there were twelve. The most popular titles aimed exclusively at women were the Lady’s Pictorial (taken in the working-class Lincoln Co-op and middle-class Bury Athenaeum, as well as the Barrow and Preston public libraries), Gentlewoman (Bury Athenaeum and the two public libraries) and Queen (Bury Athenaeum, Lincoln Co-op and Preston library). Two feminist titles, the Woman’s Signal and the Women’s Suffrage Journal, were available in Preston and Barrow public libraries. Exclusive news rooms offered some professional, scientific and technical titles, as did working-class news rooms (with fewer professional publications), but the widest selection was available in the public libraries, differentiated to suit local trades and industries. In Preston library, business titles grew from one to eight and scientific and technical publications from five to twenty.

Sporting newspapers were most popular in upper-class news rooms, less so in working-class rooms and hardly at all in improving middle-class rooms such as mechanic’s institutes. One of the oldest established sporting papers, Bell’s Life in London, was available from the 1860s at the upper-class Liverpool Lyceum and Preston’s Winckley Club; in 1870 Sporting Life was available at Barrow Working Men’s Club. Other sporting titles at the two exclusive clubs were the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, The Field, Land and Water, Country Life, Fishing Gazette and the Sportsman (the latter was the only sports title in a mechanic’s institute, Newcastle, in the late 1870s). Organised sport and the sporting press grew in tandem from the 1870s onwards, so that by 1898 the middle-class Bury Athenaeum took the daily Sporting Chronicle and the weekly Athletic News (the leading football paper, and both published by Hulton in Manchester), the Wheeler, the Cyclist and Sports. In contrast, Lincoln’s working-class Co-op reading room supplied no sports papers at all in 1898. This must have been a policy decision because readership surveys at the turn of the twentieth century bemoaned the popularity of sporting papers (but without naming the titles, annoyingly). In Middlesbrough, Bell estimated that about a quarter of the foundry workers read nothing but a sporting paper (‘that hardly comes under the head of reading’), but in the St Helens area Leigh reported that ‘Easily first comes the sporting paper […] On one evening weekly football claims attention, but day by day throughout the year [horse] racing is dominant […] The only daily paper which is at all widely read is the sporting daily.’83 He could be referring to the Sporting Chronicle, the Sporting Life or the Sportsman, or the racing ‘tissues’, flimsy sheets of results and tips. Racing papers were popular in Salford and working-class areas of Manchester, according to Haslam in 1906.84

Who Read Which Section?

The question ‘who read what?’ can be asked at the level of publication genre and individual titles, but also within each publication — ‘marriages for the maids, christenings for married ladies, deaths for undertakers, accidents for doctors, trials for lawyers, cutting-up for butchers, and amusements for every body’, as one wag put it in 1829.85 But there is some truth in this — the mother of Preston oral history interviewee Mr G2P (b. 1903) would ‘occasionally […] go through the deaths’, the mother of Mrs C2B (b. 1887) ‘had [the North Western Evening Mail] to see who was dead and born’ and in the interwar years of the twentieth century the husband of Mrs W1P (b. 1899) ‘used to have the [Lancashire Evening] Post and he would give me my column, the Deaths column.’ Clitheroe weaver and news addict John O’Neil liked to read about foreign diplomatic news, wars and battles; he was interested in Parliamentary news if it concerned working people, in market prices, and news of emigration prospects, such as accounts of the Australian goldfields.86

Sensational news was popular with all classes. In 1877 Richard Jefferies (a Tory) claimed that the farm labourer enjoyed three types of article in particular: ‘First, the most sensational topics of the week, as murders, fires, startling discoveries in California. Secondly, local intelligence, village gossip from places he knows. Thirdly, leaders, or articles of a somewhat violent character attacking the powers that be […]’87 At the other end of the social scale, the leading article was less popular; a doctor at a fictional gentlemen’s club in 1829 offers to read the paper aloud to other members warning that ‘I never read anything but accidents and offences; one good accident is worth twenty leading articles.’ Betting men (and some betting women) turned to the racing columns. In public libraries at the end of the century this became controversial, and some libraries blacked out those parts of the paper.88 William Bramwell, Preston’s chief librarian from 1879 to 1916, was against such censorship. In a newspaper interview, he described how betting men

used to crowd round the [newspaper] stands to the exclusion of other people. Then they got to talking as well. The way to meet that thing was not to black out the sporting items, which I think is a most abominable, a most un-English thing to do. Well, when it reaches the point I have just indicated they have either to cease altogether or go out. They choose the former, and there I consider my jurisdiction ended.89

Adverts, especially small ads, were probably as popular as editorial, with different types of reader interested in different types of ad. The All The Year Round writer noted that some of the first newspaper readers of the day at a London branch library in 1892 were youths, young men and young women, looking at the ‘situations vacant’ columns.90 Some adverts, however, were read less willingly. The fictional doctor at the club begins to read aloud from the accidents column:

”During the dreadful storm, last Thursday, a lamplighter, lighting one of the gas lamps on Holborn-hill, was blown off his ladder and carried to the amazing distance of Hatton-garden. He fell at the door of No. 60, where Macassar Oil continues to be sold.” — Throwing down the paper in a passion. “Pshaw! A puff — a vile puff — of all things I hate a puff — I was never taken in so before, and never, never, will again.”91

Class and Gender

Each reader and listener had their own preferences for genre, title and type of content. But it is still possible to generalise about preferred newspapers and magazines, according to the demographic variables of class and gender. Working-class readers preferred publications specifically targeted at them, such as halfpenny evening newspapers and regional news miscellanies. Local weeklies varied in their appeal to working-class readers — the Ulverston Advertiser of the 1860s prided itself on appealing to ‘the nobility and landed gentry, the professional gentlemen, the yeomen, the tradesmen, and the farmers’, in contrast to the greater working-class appeal of the rival Ulverston Mirror.92 In the next town, Barrow, the Barrow Pilot probably had a more working-class readership, as it had the most advertisements for domestic service of the town’s three weeklies; in contrast, the Barrow Times had most of the ads for foremen and managerial jobs.93 Class differences in readership were partly related to the topics covered in the paper, the editorial attitude to working-class readers and its related political stance. However, the political views of readers were related to, but not entirely determined by, their social class. While the titles available in news rooms differed according to the class of the clientele, individual readers had their own preferences. One former paper boy from Whitehaven recalled

that at one house of call where the master was a Conservative, he was ordered to leave ‘The Pacquet’. Invariably, his wife asked to see THE WHITEHAVEN NEWS [Liberal] and, to keep the waiting boy quiet while she enjoyed herself for twenty minutes or more, she gave him what he describes as two thick rounds of home-made bread with a generous amount of treacle.94

In 1896, comfortably-off retired newspaper editor William Livesey was a Unionist, while his nephew, a Mr Lee, the owner of a Wakefield worsted mill, of a similar social class, was a Radical. Livesey chose different newspapers to bond with his friend Hewitson and his nephew across political divides. When Livesey arrived at Hewitson’s Conservative Wakefield Herald office ‘he carried in his hand the Liverpool Courier (Conservative) and when he went out to his Radical nephew’s he put down this paper and took the Leeds Mercury (Radical) in his hand.’95