7. Exploiting a Sense of Place

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.07

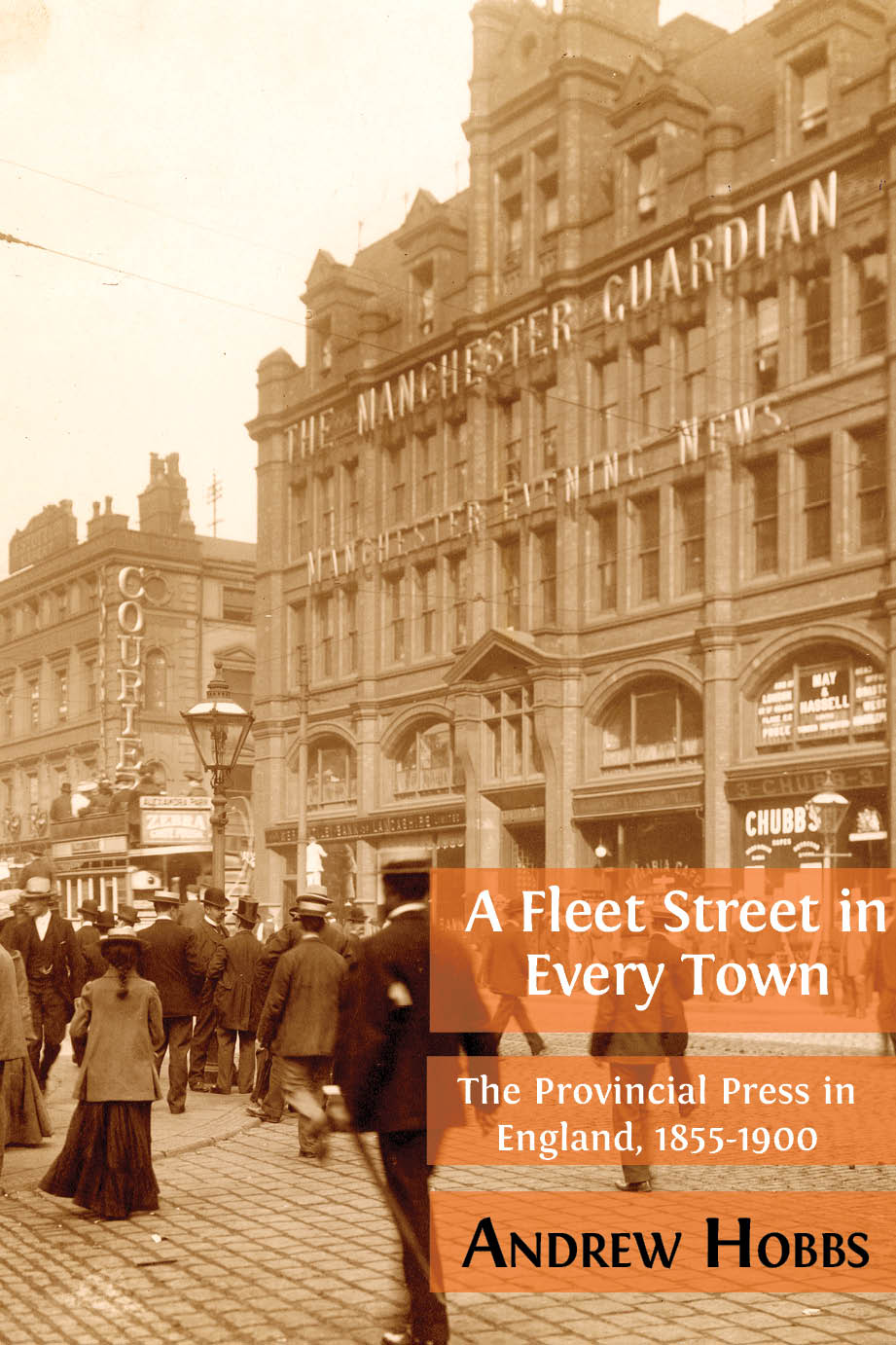

Local newspapers, like the brewers Bass (Fig. 7.1 overleaf), used local identity or sense of place to sell their product. Beer was central to the local identity of Burton, which at one time brewed a quarter of all beer sold in Britain. Bass also thought that the local press was an important carrier of local identity, and therefore put a copy of the Burton Daily Mail (est. 1898) behind their beer, to proclaim its ‘Burton-ness’. Similarly, the painter Walter Langley sometimes used particular local newspapers as props in his realist paintings of life in Cornish fishing villages, to proclaim the specificity of his subject. In ‘When the boats are away’ (Fig. 7.2), the old fisherman is reading aloud from The Cornishman (est. 1878), whose front page in 1903 consisted mainly of classified advertisements.

Fig. 7.1. The Burton Daily Mail is used to express local identity in a Bass advertising card, 1909. Author’s copy, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 7.2. The title of The Cornishman adds realism and specificity to Walter Langley’s painting ‘When the Boats are Away’ (1903). Image courtesy of the Art Renewal Center, www.artrenewal.org, all rights reserved.

This chapter examines the techniques used to exploit such attachments to place, what Appadurai calls ‘the production of locality as a structure of feeling’.1 More broadly, it describes how the local press was woven into the fabric of cultural life in a provincial town, as a mirror, magnifier and maker of local culture. Although this has been acknowledged by many historians, the processes and techniques employed have not been studied in detail, especially in one location.2 Newspapers did more than report their localities, they became part of the loop of making and re-making culture, giving them the status of a local institution — as in the postcard — part of the events and processes they reported, both arena and actor.3 They selectively promoted or ‘framed’ certain aspects while ignoring others, and occasionally intervened directly and self-consciously in local culture, initiating events and movements.4

It is argued here that local identity guided the selection, interpretation and presentation of much of the content of the local press, including non-local content. First, the concept of local identity is shown to be both complex and dynamic. We have seen that Preston news and advertising, and news from other parts of Lancashire, dominated the content of Preston’s newspapers (Fig. 6.7). This chapter analyses the nature of some of that local content and the techniques used by the local press to promote and sustain local identity. Finally, the contested nature of local identity is acknowledged, and the theory that ‘othering’ is central to identity formation is questioned, in relation to the local press.

The idea that local newspapers influenced local identity was the starting point for this research. It is propounded by journalists and accepted by historians. Manchester Guardian editor C. P. Scott wrote: ‘A newspaper […] is much more than a business; it is an institution; it reflects and it influences the life of a whole community.’5 Broadcaster Andrew Marr, a former newspaper journalist, claimed: ‘Anyone who has lived without a local paper quickly comes to realise how important they are; a community which has no printed mirror of itself begins to disintegrate.’6 Historian Jeff Hill is equally eloquent:

The press is not simply a passive reflector of local life and thought but an active source in the creation of local feeling. And in reading press accounts of themselves and their community the people who buy the newspapers become accomplices in the perpetuation of these legends. To paraphrase a famous observation by Clifford Geertz, the local press is one of the principal agencies for “telling ourselves stories about ourselves”.7

Peter Fritzsche, in his study of Berlin’s local press at the beginning of the twentieth century, argues that ‘the city as place and the city as text defined each other in mutually constitutive ways.’8 But by what techniques and processes would a newspaper change the way that readers thought about themselves and their place? And what historical evidence could be adduced to test this idea?

The Construction of Local Identities

Patrick Joyce argues that class was not the dominant form of identity in Victorian England; instead, people defined themselves by neighbourhood, workplace, town, region, religion and nation.9 But few historians have followed his lead, so that the obvious hierarchy of geographical identities still corresponds to a hierarchy of their status within academic history, from national and international, through regional and county to local, despite evidence that local identities were the most powerful on a day-to-day basis.10 Some of the identities in such a notional hierarchy seem to ‘nest’ neatly inside each other, but the relationships between these nested territories are complex, and in constant flux.11 Neither are local identities simply scaled-down versions of national identities. Further, local identities can of course co-exist with local versions or building blocks of national identity, as in the German idea of Heimat or Russell’s ‘national-provincial’ structure of feeling;12 Jones argues that Welsh local papers contributed to the strengthening of Welsh national identity in the nineteenth century.13 However, locality has not been problematised in the same way as the concepts of nation and national identity, despite the fact that most of us live our lives at a local level.

Local identity is a vague yet powerful notion.14 It overlaps and combines ideas such as sense of community, genius loci (spirit of place), sense of place, civic pride, local patriotism, parochial loyalties, local attachments and local belonging (phrases used in nineteenth-century journalism and in more recent history, geography and sociology).15 This loose collection of ideas, feelings and habits was important to people in the past, sometimes a matter of life or death. To paraphrase Royle, the local is assumed to exist, and the historian must therefore seek out its meaning and identity, ‘unstable, fluctuating and ambiguous though these meanings and identities are […]’16 Here, Russell’s definition of local identity is adopted: ‘an intense identification with a city, town or village where an individual has been born or has long residence or connection.’17

Table 7.1 below brings together some likely factors in the creation and development of local identity. It does not pretend to be an exhaustive list, and it would be difficult to decide which ones were necessary or sufficient. Not all the factors are of the same type or of the same importance. For instance, those grouped under the title ‘Self-conscious differentiation and expression of local identity’ (the ‘collective self-conscious’, perhaps) can each subsume almost any of the other factors. The purpose of the table is to show how complex local identity is, how layered and interconnected.18 It also makes clear that local newspapers are only one factor among many. Local identities were being formed and developed long before newspapers were invented.

Table 7.1. Some factors in the formation of local identities.

There is of course disagreement among members of the same community about the unwritten lists of qualities held in common by local people that differentiate them from outsiders, and this is examined in the last section of this chapter. At its simplest, this contestation might be between elite and popular mentalities. Many historians have been suspicious of local, regional and national identities, seeing them as hegemonic attempts to downplay conflicting class interests; this may be true, but there is more to these identities than that. There is also tension between internal and external characterisations of a place, with internal ones generally more positive.19 Internal representations, in particular those generated or mediated locally by the local press, are the focus of this chapter. Another aspect of local identity formation — inclusion and exclusion, differentiation or ‘othering’ — is often taken as central to any identity, individual or collective, but little evidence has been found for this idea in Preston’s newspapers.20

The process of creating, sustaining and sometimes destroying local identities happens when some or all of the elements in Table 7.1 (plus others no doubt omitted) combine in a particular contingent sequence over time. The chronological order in which factors come into play is significant — Gilbert describes the importance of the mining unions in creating community structures in the South Wales village of Ynysbwl, in contrast to Hucknall in Nottinghamshire, where the co-operative movement had already filled the role outside the workplace played by the union in Wales. Following Royle, local identity, ‘as a historical concept […] must be made time-specific if it is to have any useful meaning in historical analysis.’21

Here complexity theory, and the idea of emergent phenomena, help to describe the sequencing, overlaps, and complex interactions between so many variables. The concept of emergence describes how complex systems and patterns in nature and in society emerge from a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions, for example an eddy in a stream, which is more than the sum of its parts, is a pattern or arrangement rather than a thing in its own right, and yet is real — it can be seen and it affects other things.22 This approach uses probability to say that some things are very likely to proceed in a certain way at a general level of description, but at a more detailed level of description, a particular case cannot be predicted.23 The contingency and dynamism of the process is seen when two seemingly similar places (the Victorian new towns of Barrow-in-Furness and Middlesbrough, for example) develop very different local identities, and these identities change over time.

Just as the local press was only one among many cultural institutions capable of developing local identities in similar ways, it was only one among many institutions using the same techniques and ideas of what characterised a locality. The content of a local paper had strong similarities to the contents of a public library or the lecture programme of a literary and philosophical society, for example.24 Local newspapers recognised the power of local patriotism and traded on it consciously, often explicitly.25 Some historians have recognised this, but few have examined the phenomenon in detail.26 Joyce believes that newspaper ‘framing’ helped to define a place:

The local press was extraordinarily important in […] presenting the town as a universe of voluntary and religious associations in all the range of their many local activities. These it reported on as elements in the life of a single entity.27

As a cultural product, the local press is particularly well suited to sustain and amplify local identities.28 Its very existence helps to put a locality on the map. Its ability to tell and to enshrine familiar local stories, over and over again, is crucial, in common with most of the other cultural products and institutions listed under the heading ‘Self-conscious differentiation and expression of local identity’ in Table 7.1, above. News reporting (‘facts’) is one aspect of this storytelling function, which Nord distinguishes from a second function of the local press, ‘forum’, the explicit encouragement of community-building.29 As he point out, this does not require unity or even respect, but the local press can enable readers to meet in print and dispute the nature of local reality. There is no evidence that this ‘forum’ function declined towards the end of the century. While contemporary commentators noticed the growth of avowedly ‘objective’ reporting, and a recasting of readers from participants to consumers, other traits of that disputed concept, New Journalism, such as greater reader involvement, could still build communities. Children’s nature clubs and competitions in which readers voted for favourite local individuals and institutions are two examples. Three other features of the press are significant here: its constant, gradual, repetitive nature, its miscellaneity and its ability to amplify. Scott-James put the first point well in 1913:

If the Press is powerful it is as an aggregate, as a multitude of writings, each of small importance when taken by itself. It is in its vast bulk, its incessant repetitions, its routine utterance of truth and falsehood, its ubiquity, its permeation of the whole fabric of modern life, that the Press, however blatant, rather conceals than reveals its insidious power of suggestion.30

This argument applies equally to the provincial press, ‘powerful as an aggregate’. The second point, the miscellaneity of the press, is made by Joyce above, that the local press is powerful through its function as a container, a box with ‘local’ emblazoned on its side, so that whatever is put in the box automatically becomes local, or at least locally mediated. The press is able to roll together many of the factors involved in local identity formation, and it seems likely that the more factors that can be combined, the more powerful is the effect (although emergence theory suggests that the process is not one of simple addition or multiplication). The third feature, amplification or publicity, is central to mass media products. Sport can be a particularly powerful expression of local identity, especially when rival teams play the role of ‘other’, and the growth of professional football during the high point of the Victorian local press was a symbiotic process. Sports reporting amplified the impact.31 ‘Amplification’ rightly suggests that the press reflected and reinforced aspects of local identity much more than it originated or determined them.

Newspaper Techniques for Producing Locality

By mid-century, local newspapers not only mediated news from elsewhere for their local audience, they also published news from their own locality. To the mystification of many Victorian metropolitan journalists and some present-day academics, the minutiae of local life mattered to most of the population.

Nothing interests a man more than the news of his own neighbourhood […] We shall therefore continue our endeavours to cram our sheet full of facts — facts possessing as much local interest as possible […] Our chief object is to make this paper a faithful record of everything of public importance that may transpire in the neighbourhood […]32

Local newspapers are skilled in emphasising those identity-forming factors that bring people together and give them and their activities a common label. Take for instance a leader in the Preston Chronicle, celebrating the opening of the new town hall in 1867, in which the frequent use of ‘we’ and related pronouns is designed to create a sense of inclusion (my emphasis):

What suited our grandfathers does not suit us. With the increase of our population, the extension of our streets, and the spread of education among us, has come the desire to meet the needs of our town by the erection of a municipal palace […]. In setting our hands to such a work, we have felt that we had duties to discharge, not only towards the present, but towards the future. We inhabit a town, which, for situation, is unrivalled among the districts of the cotton manufacture […].33

These first-person plural pronouns were also used in the same way by other newspapers, particularly ‘our’ and ‘us’ in a rhetoric of local identity shared by the speaker and addressee (see below).34

Publishers and journalists believed that local patriotism made people more likely to buy a local paper. In 1888 the Preston Guardian looked forward to the imminent transfer of powers from county magistrates to county boroughs such as Preston because, ‘by promoting and concentrating local patriotism to the full, [this change] should not be without many important direct and indirect effects on the interests of the newspaper press.’35 They also saw the promotion of local identity as part of their job, and could call on a wide vocabulary of techniques. Just by including the name of the town in its title, the Barrow Herald (Fig. 7.3) sent out a powerful message — ‘this is about you, your town and your life in this place’.36

Fig. 7.3. Barrow Herald masthead, 10 January 1863, including the place name in the title. Image used by permission of Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre, Barrow, CC BY NC ND 4.0.

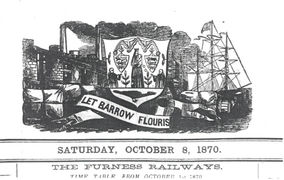

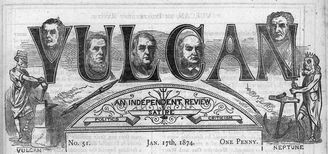

Many local newspapers portrayed their town or wider circulation area in symbols and emblems, such as that seen between the words ‘Barrow’ and ‘Herald’ in Figure 7.4 below. The first paper in this rapidly developing new town was eager to establish an identity for what had been marshland and fields a few decades before. The emblem combines modern images of the railway that created the town, foundry chimneys and a ship in the port, surrounding symbols of the ancient Furness abbey. Another Barrow masthead, that of Joseph Richardson’s satirical magazine Vulcan (Fig. 7.5 below), personifies the town through portraits of his targets, the small group of leading industrialists and aristocrats with whom he had clashed. Such imagery would have been pointless in most towns, Preston included, where power was shared more widely.

Fig. 7.4. Close-up of Barrow Herald masthead, showing local imagery. Image used by permission of Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre, Barrow,

CC BY NC ND 4.0.

Fig. 7.5. Masthead of the Barrow satirical magazine Vulcan, 1874, featuring faces of the town’s governing clique. Image used by permission of Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre, Barrow, CC BY NC ND 4.0.

Equally, in the old, well established town of Preston, where civic identity was not in doubt, the two leading papers, the Guardian and the Herald, had no masthead images at all (the Herald had carried an image of Britannia in its early years), and those that did tended to choose the town’s coat of arms, as a simple assertion of an identity already well known — although allied to symbols of political identity. While the Liberal Preston Chronicle gave equal space to the crown and the Magna Carta either side of the town crest (Fig. 7.6 below), the Tory Preston Pilot omitted any symbols of rights or liberty, and made the crown more dominant (Fig. 7.7). Both emblems combine national and local imagery. The Preston Herald, like most local papers, mapped territorial space simply by its labelling of different news columns — with ‘local news’ as core and ‘district news’ as periphery.37 This extra dimension of place reduces the miscellaneous nature of the information on a newspaper page, in a way not available to non-local publications.38

Fig. 7.6. Preston Chronicle masthead emblem, 5 April 1862, featuring Magna Carta. Note also use of Lancashire dialect word ‘nowt’ in advert below date. Image used by permission of E. Michael Atherton, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 7.7. Preston Pilot emblem, 13 September 1851, with a more prominent royal crown and no Magna Carta. Author’s copy, CC BY 4.0.

Local papers often gave away prints depicting local places or personalities, such as a handsome engraving of the proposed market hall ‘presented to the purchasers of the Bolton Chronicle’ in c. 1852, depicting a building obviously designed to increase the town’s status.39 While British local newspapers were not as active as their US counterparts in promoting lithographed views of towns and cities, they were significant publishers of local images and maps.40 A town map was given with the Preston Guardian in 1865, while views of the town’s most elegant buildings were often part of sheet almanacs given away before Christmas, such as the Preston Chronicle’s last almanac, for 1894, featuring a photograph of the handsome neo-Gothic Gilbert Scott town hall.41 Maps and views of Preston had been available long before the town had a newspaper, but in a new town such as Barrow, the press was probably more significant as a disseminator of local images. The Barrow Herald, for example, occasionally published lithographed colour maps of Barrow’s latest developments, and the Barrow Times, linked to the Furness Railway, published a map of the company’s network on the front page of every issue for many years.42

‘All maps are rhetorical. That is, all maps organise information according to systems of priority and thus, in effect, operate as arguments, presenting only partial views, which construct rather than simply describe an object of knowledge […]’43 Local papers could use maps and views to convey their particular construction of local reality. In the 1890s the Preston Guardian published nostalgic views of the town by local artist Edwin Beattie, at a time of much redevelopment. Besides views and maps, local papers also published portraits of local individuals. In 1893 the Preston Herald ran an illustrated series on Preston’s temperance pioneers, included portraits of the mayors of each borough in its circulation area on its sheet almanac, and engravings of Lord Salisbury, the town’s MPs and Conservative officials with a picture of the new Conservative Working Men’s Club as a souvenir of its opening.44 Sadly, further work on local newspaper iconography is hampered by the fact that few illustrated supplements, almanacs and souvenirs have been preserved.

Local newspapers were major publishers of fiction and poetry with local themes. Their wider literary role, which also included original reviews of books and periodicals, has been ignored by literary historians who have mistakenly generalised from the lack of literary content in London newspapers.45 Around a third of the 4,000 poems published in the 81-year existence of the Preston Chronicle alone were written by local or Lancashire writers, from a sample of the first Chronicle in each month for 1855 and 1885 (24 issues). Seven of the 12 poems sampled in 1855 were written by local or Lancashire writers, compared with 4 of 17 poems published in the 12 issues sampled in 1885. Although there were no poems with local themes in the 1855 and 1885 Preston Chronicle samples, they did appear sporadically, such as ‘Stanzas on the Leyland Show, &c’ in 1860 and ‘Right and Left’, a comment on a lock-out, in 1878.46 Some, such as the long dialect poem ‘Traits o’ Accrington’ published in the Accrington Gazette in 1882, addressed local identity head-on.47 Local newspapers, the main forum for publishing local poets, ‘constituted at once a nursery and a shop window for new literary talent’.48 The majority who failed to progress to publishing in book form served an important ‘bardic’ function, however, as a ‘slightly more articulate neighbour’. They ‘remained in a bardic community with their readers, and were able to represent their views’.49

Local and localised novels in serial form, short stories and sketches (the last two in both dialect and Standard English) were also staples of the local press. The ability of fiction to add significance and signification to a place is well expressed by the Buchan Clown, a Scottish magazine published in Peterhead: ‘Shall Cock Lane have its ghost, Cato St its conspiracy, and shall the Longate of Peterhead sink into oblivion unheeded and unchronicled?’50 In 1864 the Preston Chronicle serialised the historical novel ‘The Knoll at Over-Wyresdale’ (a rural area twelve miles north of Preston) by ‘J. H.’ and in 1887 the Preston Guardian began the serialisation of ‘The Black Dog of Preston’.51 The author, James Borlase, was not local, but specialised in writing local fiction for newspapers across the Midlands and the North of England.52 The first episode described him as the author of The Rose of Rochdale, The Luddites of Leeds, The Lily of Leicester, The White Witch of Worcester, The Nevilles of Nottingham, Leaguered Launceston, ‘&c.’ The cynical formula behind this alliterative appeal to local patriotism did not necessarily negate the stories’ power to endow place with meaning. Attractions of the Preston Guardian’s expanded Saturday supplement in 1888 included “Locked Out”, ‘a Lancashire Christmas Tale in the Dialect’, by George Hull, ‘numerous SHORT STORIES, generally local, and ORIGINAL LANCASHIRE SKETCHES’.53 Appeals to local, county and regional identities were a selling point.54 The ‘street philosophy’ type of sketch, invented in Paris in the 1780s and transferred to London in the 1840s, appeared in the Preston Chronicle from the 1860s onwards.55 In an example from the Preston Herald of 1890, an anonymous flaneur described ‘Fishergate — most elegant and fashionable of Preston thoroughfares’ as part of a series on Preston’s main streets:

It was growing dark as I took up my position in a quiet and unpretentious corner […] standing, so to speak, in the shadows of the Town Hall clock. It was Saturday night […]56

There are many more examples, particularly from the Hewitson era Preston Chronicle. The local press brought together this local literary material, which previously would have appeared as street literature, pamphlets or not at all.57

A local press technique for presenting foreign news demonstrates the extra dimension of place available to these publications, connecting readers more closely to far-away events. As Hess & Waller note, ‘local journalism’s view extends beyond the parish boundaries to interpret the world through a local lens that makes meaning for audiences’.58 Individuals who found themselves in foreign lands often asked relatives back home to forward their letters to the local press, such as the young man who joined the Pontifical Zouaves, the volunteer force formed to assist Pope Pius IX in defending the Papal States against the Italian Risorgimento in 1868. The letter describes his daily routine, his companions, a ‘first-class cricket match’, and likens Rome’s ‘Corse’ to Preston’s main street, Fishergate.59 Here, the reader is invited to identify with another Prestonian, and to see foreign places and events through Prestonian eyes, a process of localising the global.60 Another English volunteer in the same conflict, but on the opposite side, described his journey from Birmingham to Italy, noting that in the Bay of Biscay ‘the water was as smooth as Soho Lake or Kerby’s Pool’, two well-known Birmingham boating lakes.61 John Macklin Eyre from Newcastle emphasised his local identity by dropping a dialect word, ‘canny’, into his ‘Letter from Capua’, during the battle of Volturnus, comparing the terrain to a Newcastle beauty spot:

I will give you a slight sketch — plain and impartial — of my career since leaving canny Newcastle […] Caserta […] is a place of no small order, being surrounded by the Volturno, excepting the south side, where there is a flat plain, something like our Leazes.62

A journalist used the same technique when describing a suburb of Istanbul to Sheffield readers, during the 1877 Constantinople peace conference:

Many of the people of Pera speak of life […] in Stamboul proper […] as Attercliffe is viewed by the sons of certain good men who made their fortunes in that busy if not beautiful neighbourhood […] throughout a large portion of its extent the “Grand Rue” of Pera is about one-third the width of High-street, Sheffield, and almost as rugged under foot as the slopes of the Mam Tor [a hill in the Peak District near Sheffield].63

Advertisements for local businesses and events unwittingly made each district’s newspapers distinctive, reflecting the local economy and local concerns, ‘part of the process whereby newspapers were cemented in to the life of their communities.’64 This function gave local papers a competitive edge over London papers.65 This local distinctiveness made some places more profitable for advertising than others, for example Milne and Jones believe that the heavy extractive industries of the North East and Wales had little need to advertise in the local press.66 Such statements are difficult to test without advertising revenue figures for the period, although proxy figures are available for some earlier years, using government returns of advertising duty collected from each newspaper. Table 7.2 below, using figures for 1838 (information for later years has not been traced) gives qualified support to the views of Milne and Jones, with Merthyr Tydfil in the South Wales coalfield producing the least advertising duty, but Newcastle upon Tyne, a port serving a coal, iron and shipbuilding area, producing the most. Port cities probably produced more advertising because of their associated commerce and the needs of middle-class merchants. However Preston, with its commercial and administrative functions, produced a similar amount of duty to Bolton, which lacked such functions and had fewer markets. The relationship between local economies, newspapers and their advertising is clearly complex.67

Table 7.2: Advertising duty per head of population, 1838.68

|

Population (1841) |

No. of newspapers (1838) |

Duty per head of population (pence, 1838) |

||||

|

69,430 |

5 |

1,915 |

8 |

0 |

6.6 |

|

|

282,656 |

12 |

5,807 |

2 |

6 |

4.9 |

|

|

240,367 |

6 |

3,561 |

14 |

9 |

3.6 |

|

|

52,818 |

3 |

425 |

6 |

6 |

1.9 |

|

|

50,332 |

3 |

365 |

2 |

0 |

1.7 |

|

|

Swansea |

32,649 |

2 |

222 |

6 |

0 |

1.6 |

|

50,163 |

2 |

316 |

1 |

0 |

1.5 |

|

|

42,917 |

3 |

137 |

0 |

0 |

0.8 |

|

Some individual advertisements were used more explicitly to capitalise on local patriotism, such as that for Preston butcher Richard Myerscough and his North of England Steam Pork Factory, making a play on the letters ‘PP’ in Preston’s coat of arms. Headed ‘PP — Proud Preston — Prize Pigs. Prime Pork’, it begins:

In hist’ry we’re told

Was famous for Tories and Whigs;

Time changes; we see,

At present PP

Is noted for Pork and for Pigs.69

The ‘hist’ry’ of ‘Proud Preston’ was another popular local press genre, perhaps because, by its nature, local history writing demands ‘expression of a definable identity’, as Vickery notes of this genre in book form. Indeed awareness of continuity, or memory, is central to the classical philosophical understanding of personal identity.70 Volumes of local history were popular, and ‘a staple of modest family libraries’, but history was probably more widely read in newspaper form, because of the newspaper’s frequent appearance and wide readership.71 One writer saw the work of the weekly newspaper publisher as, first, to provide local news, but second, to give ‘attention to local history and antiquities’.72 As Janowitz notes of the mid-twentieth-century local press in Chicago, the linking of local history and local identity goes beyond overtly addressing local historical topics, ‘through a style of writing which proudly refers to the age of individuals or to the number of years an organisation has been in local existence. Even routine announcements try to emphasise the stability and persistence of organisations and institutions […]’73

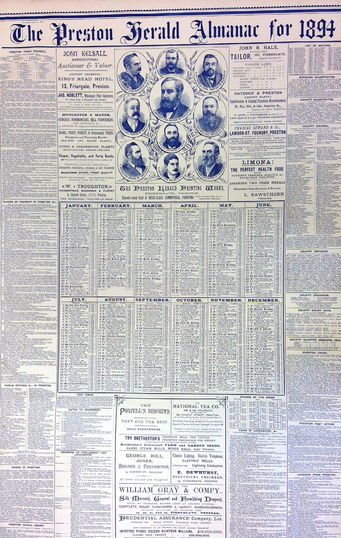

There was a boom in local history in the local press from the 1870s onwards. Biographies of local figures such as the Preston Herald’s series on temperance pioneers in 1893 and obituaries attempted to personify Preston’s history.74 Almanacs such as that given by the Preston Herald in December 1893 (Fig. 7.8), intended to hang on walls for the following year, listed, for each day of the year, the deaths of local worthies, dates of lock-outs and riots, the opening of the town hall, notorious local murders and the purchase of the town’s first steam fire engine, among anniversaries of national and international events. Local history in Preston showed ‘no hint of pastoral regret or nostalgia’. Instead it was written to praise the present, with an understanding that ‘identity is always, and always has been, in process of formation’, hence the recurring mockery of Garstang as a ‘finished town’ that neither progressed nor changed.75

Fig. 7.8. Preston Herald sheet almanac for 1894, measuring 87cm x 55cm, including a chronology of local historical events (centre). Author’s copy, CC BY 4.0.

Many genres and formats of historical writing are found in local newspapers, including biography, memoir/reminiscences, chronology (sometimes as separate articles, sometimes in almanacs), historical background to news stories, extracts of historical documents, topography, archaeology (finds during demolition and construction, for example), architecture, folklore, legends, customs and superstitions. Typical formats are ‘notes and queries’ columns, dedicated history columns and series, reports or summaries of lectures and talks, touristic guides, dialect writing, drawings, maps, photographs and diagrams, poetry and fiction.

Newspapers explicitly linked history to local identity. A poem in memory of local historian T. T. Wilkinson of Burnley, a frequent contributor to local papers, praises him for connecting ordinary local places to ancient legends and famous events, adding glamour to familiar, much-loved landmarks:

For he that is dead set my heart aflame,

While as yet with my schoolmates surrounded,

With the legends that lurked in each dear old name

And the myths on the hills that abounded.

He called forth the heroes of story and song

Great Thor, greater Woden and Balder,

And linked them for aye to the homesteads along

The banks of the Brun and the Calder.76

The introduction to a new local history column, ‘Burnleyana, Notes new and old on Burnley and its neighbourhood’, in the Burnley Advertiser of 1880 reveals the connection between memory and local identity:

our first wish will be to afford pleasure and recreation to Burnley men and women to whom all that appertains to the smoky busy place is very dear for the sake of hallowed memories.77

Newspaper editors were aware of this deep connection to place among many of their readers. Alfred Gregory, editor of the Tiverton Gazette for more than fifty years, recalled how one reader once said of Tiverton, ‘I love every stone in the place.’78 Some editors shared this love; most of them exploited it. Local history writing traded on the power of local identities, but in a circular way it also helped to create shared public memory and the continuity that is central to local identities. It had the power to make ordinary places sacred, to confer meaning on locations far from the centres of cultural power.

Boosterism, more a tone of voice than a type of content, was a happy duty for most local publications. Souvenir histories of provincial newspapers stress how their fortunes were tied to those of the area they served, and how the papers helped to promote and develop those areas.79 Local paper boosterism addressed a wider audience than the locality, as when the Barrow Times countered criticism of Barrow in the Liverpool press in 1871, or when the Barrow Herald compared local steel production favourably with that of Belgium in 1878. ‘Three days later the Herald reported that the story had created a stir among the Belgians, “as we have received orders for papers containing the paragraph, besides instructions to forward the Herald regularly”.’80 Boosterism was particularly prevalent in a new town such as Barrow, especially in the pages of the Barrow Herald (motto: ‘Let Barrow flourish’) and the Barrow Times, associated with the town’s leading industrialists.81 In 1871 the Barrow Times published a 2,000-word article on a ‘near perfect’ new steam corn mill, and when James Ramsden, the town’s most powerful figure, was honoured in 1872, the same paper dedicated four pages to the unveiling of his statue, including a 7,000-word history of the town.82

While the Barrow Times could be dismissed as the mouthpiece of the town’s ruling clique, the rival Barrow Herald, not part of the inter-connected companies that had built Barrow, was equally patriotic. The frequency of words such as ‘progress’, ‘rapid’, ‘unique’ and ‘increasing’ in leader articles in the Barrow Times, Barrow Herald and Vulcan in the early 1870s gives a flavour of the promotional nature of the writing. However, the much lower level of boosterism in the more Radical Barrow Pilot shows that it was not an inevitable aspect of new-town Victorian newspapers, and even in the Barrow Times this discourse declined during the depression of the late 1870s, although the paper still presented an encouraging picture.

In the papers of Preston, a town with a more stable economic position, boosterism was more muted, particularly in the last decades of the century. However, it can be seen in the ‘Opening Address’ of the Preston Herald in 1855: ‘Natives of the town ourselves, we have at heart the good of our neighbours, and shall always be ready to render zealous support to every measure that promises improvement to our locality.’83 An 1860 Preston Guardian leader extolled ‘the extraordinary progress and present prosperity of the town […] No other nearer than Glasgow, can expect to attain the dimensions and influence of a large city, as Preston is certain of doing.’ Similarly, in 1867 a Preston Chronicle leader described Preston as ‘a town, which is historically famous, as well as commercially important […]’84 Impressionistic comparisons of some civic high and low points in Preston during the period were made, to examine whether the town’s identity was discussed more explicitly at these times. This exercise revealed that high points such as the opening of a new town hall and park in 1867, and Preston North End Football Club winning the ‘double’ in 1888 did produce more characterisations of the town, but low points such as a strike and lock-out in 1878, and the near collapse of Preston North End in 1893 were not linked to local identity, showing the selectiveness of Preston’s press.

However, more systematic analysis of explicit characterisations of Preston in the Preston Herald found a propensity to criticise the town almost as much as to praise it, as in an 1890 leader arguing that ‘Preston enjoys advantages that Oldham does not and cannot command, but the town has been out-distanced in the race through lack of modern mills, and machinery brought up to date’.85 Yet the editorial voice was more likely to boost Preston than were readers and the local individuals whose comments were reported. Explicit representations of the town were noted in seventy-nine issues of the Preston Herald between 1860 and 1900, and grouped into categories. The representations were differentiated by their source, whether from readers’ letters, reported speech or the editorial voice of the paper (Table 7.3 below). In its leader columns and other forms of direct editorial address, the Herald showed a slight preference for the positive, with twenty-five positive comments about Preston and eighteen negative ones — a close ratio of four to three in favour of the positive. However, in reported speech, negative outweighed positive by two to one, and in readers’ letters even more so, by four to one. Typical examples are a municipal election speech by J. Whittle, the Progressive candidate, referring to Preston’s high infant mortality rate, claiming that ‘There were at least a thousand people every year murdered in Preston […] The death-rate of Preston was simply appalling’, or a letter from ‘Ventilator’, saying that ‘the town appears to be in a disreputable condition so far as regards sanitary matters […]’86 Boosterism was only one viewpoint among many in the contest for local identity, and many people claimed the right to criticise their town as an expression of local identity.

Table 7.3. Representations of Preston in the Preston Herald, 1860–1900.

|

Type of representation |

Positive or negative |

Source of representation |

||

|

Reported speech |

Editorial voice |

|||

|

High death rates |

- |

2 |

13 |

3 |

|

Needs improving |

- |

10 |

2 |

2 |

|

Backward in comparison to other towns |

- |

2 |

4 |

7 |

|

Dirty town |

- |

11 |

0 |

1 |

|

Town in decline |

- |

0 |

5 |

2 |

|

Corrupt politics |

- |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Uncultured |

- |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

Immoral town |

- |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Stronghold of Toryism |

+ |

2 |

6 |

7 |

|

Patriotic town |

+ |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

Garrison town |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Pro-Stanley |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Progressive |

+ |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Anti-Stanley town |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

||

|

Sporting prowess |

+ |

1 |

0 |

7 |

|

Cultured/educated |

+ |

1 |

4 |

|

|

Musical |

1 |

|||

|

Pleasant, attractive town |

+ |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

Large and growing town |

+ |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

Market town/agricultural centre |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Generous, compassionate |

+ |

2 |

||

|

1 |

0 |

3 |

||

|

Birthplace of teetotalism |

0 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Total positive |

7 |

16 |

25 |

|

|

Total negative |

29 |

31 |

18 |

|

Sometimes the local press moved beyond its publishing role in its interventions in local culture, initiating social, charitable and educational activities. The most visible, constant way in which local papers claimed a place in local culture beyond their pages was their physical presence as prominent businesses, usually on the main square or commercial street of the town. This visibility was heightened when publishers commissioned purpose-built premises, as the Toulmins did for the Preston Guardian in 1872, making their offices ‘unique in Preston — or for that matter in the whole of the northern and eastern divisions of the county’, as the paper proudly stated in a two-column celebration. The ‘great carved and marbled halls of newspaper offices in the largest cities mimicked the libraries and town halls being raised at the same time.’87 The status of newspapers as local institutions was confirmed by their inclusion in trade directories alongside banks, theatres and gas companies. Newspapers also brought readers together, through initiatives such as the Preston Guardian Animals’ Friend Society, or the charity entertainment at Preston’s Public Hall in 1895, featuring 150 young performers, organised by the Lancashire Catholic magazine.88 Local papers often set up, or acted as collecting points for, local charitable appeals such as the smallpox relief fund organised by the Lancashire Evening Post in 1888.89 The Preston Guardian claimed that its campaign against steaming in weaving sheds led to the 1889 Cotton Cloth Factories Act, and that its programme of agricultural instruction and related farmers’ associations had

enormous consequences […] affecting the whole country. The movement started from Preston, and The Guardian was the initiating force […] it is only two years since that a farmer declared in the […] Public Hall that he would not sell for £200 the knowledge gained by the instruction thus inaugurated.90

Competitions, introduced in the 1880s, encouraged readers to respond to local (and other) publications, and to see their writing, ideas, names and addresses in print. Virtually the only local content in the Preston Monthly Circular (1895–1915) was a prize competition, launched in 1896, in which readers had to guess what other readers had voted for, in a series of popularity contests including the ten most popular men in Preston, the twelve finest buildings, most popular clergymen, finest streets, most popular doctors, ‘12 most attractive pictures in the Art Gallery of the Harris free library’ and the twelve finest hotels in Preston. Local newspapers went beyond merely reflecting local culture, to shape it, and to mobilise readers.

‘Us’ and ‘Them’ and Contested Identities

‘Othering’, or the definition of self through differentiation from an other, is seen by many modern writers as central to identity.91 This technique may fit nineteenth-century Western views of the Orient, for example, but it is less common in nineteenth-century local papers than one might expect, even in football coverage. The idea of ‘us’ can do its work without its binary opposite, ‘them’, if ‘we’ are confident and unthreatened in ‘our’ identity, as in the ancient, established town of Preston.92 By contrast, in Wales, where nation status had to be asserted self-consciously, the newspapers differentiated the Welsh from the English ‘other’, and in the new town of Barrow-in-Furness, local papers differentiated Barrow from its sleepy neighbour Ulverston, its new-town rival Middlesbrough, and from other ports and iron and steel areas.93

But in Preston, for the most part, othering was absent. Only occasionally did Preston newspapers define the town in opposition to an ‘other’.94 This could be London (‘We ought to have nothing in Preston approaching in loathsomeness the purlieus of Drury Lane and Baldwin’s Gardens and the New Cut’) or a generalised south (‘Southern agricultural societies might be described as medieval in character […] in Lancashire and the North we smile at such evidences of rural eccentricity’).95 More often, however the ‘other’ was the next town. The Victorians kept a close eye on what rival towns were doing, whether it was building a grander library than them, or ensuring more of their children survived to adulthood, and ‘very few wanted their own town to be publicly denounced as worse than their neighbours’.96 A leader column from the Chronicle during a strike and lock-out in 1878 categorises Blackburn’s cotton workers very clearly as ‘them’:

[…] the operative classes of Preston are much more peaceably disposed than those of Blackburn. There is a rough, turbulent, vehemence — a defiant, quarrelsome bull-neckedness about the Blackburnian body […] this, luckily, is not the spirit of Preston operatives — they are more docile, enduring, and order-loving […]97

But this was the exception rather than the rule in Preston’s papers.98 ‘Othering’ was less common than the other techniques of exploiting local patriotism. Only when there was a threatening level of competition for resources or status (as in the Lancashire-wide strike above), did the town’s newspapers define Preston against the other. Even then, ‘othering’ was not inevitable; there was no scapegoating when Preston North End nearly collapsed in 1893 (see next chapter). A subtler way of defining Preston’s identity than invoking the ‘other’ was through editing out undesirable aspects of the town, a different process of inclusion and exclusion. Internal conflict, however, was a different matter, at least at the start of the period.

Community does not necessarily imply harmony.99 The quiet confidence of Preston’s identity did not preclude internal conflicts over the nature of that identity, although the amount of conflict declined after mid-century (see Table 7.4 below).100 Explicit conflict (defined as two opposing viewpoints in the same article) was identified in all sampled issues of the Preston Herald (all those published during September and October every ten years from 1860 to 1900). In the Herald, explicit conflict appeared predominantly in readers’ letters (thirty-one of forty-nine instances of conflict over Preston identity, see Table 7.5 below), but also in reports of public meetings and the deliberations of councillors and Poor Law Guardians, and occasionally in leader columns. Conflicting characterisations of the town included Preston’s relationship to the Stanley family (powerful, politically active landowners), the tension between tradition and modernity, whether the town centre should be industrial or exclusively retail and residential, Preston as a Conservative or a Radical town, a Protestant town or a more diverse, tolerant place, and a progressive town with high local taxation or a retrenching, business-led place. Some of these conflicts concerned power and inequalities, but some did not. Less explicit but more frequent differences in how the town was characterised would also be apparent to those who read more than one local paper. As we saw in Chapter 2, the many reading rooms and news rooms provided plenty of opportunity for such comparisons.

Table 7.4. Conflict in the Preston Herald, 1860–1900.

|

1860 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

||

|

Articles displaying conflict |

29 |

51 |

66 |

23 |

23 |

|

12 |

9 |

14 |

8 |

7 |

|

|

No. of columns of type published weekly |

48 |

84 |

128 |

132 |

148 |

Table 7.5: Where conflicts about Preston appeared, Preston Herald, 1860–1900.

|

Type of item |

No. of items featuring explicit conflict |

|

31 |

|

|

Report of public meeting |

6 |

|

Leader columns |

5 |

|

Other news report |

4 |

|

Report of public body |

3 |

There was constant conflict between rival newspapers. Irish disestablishment and a long general election campaign in 1868 produced much vituperation, particularly between the Herald and the two Liberal papers, the Chronicle and the Guardian. At less turbulent times, each paper would present their political viewpoint as the norm, by weaving together local and political identities and retelling old stories that characterised Preston either as Tory or Radical. In October 1893 former Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury visited Preston, to open new purpose-built premises for the Conservative Working Men’s Club. The Herald published a special supplement including ‘a finely executed engraving’ of the new club, with portraits of Lord Salisbury and leading local Conservatives. Extra copies were printed due to the ‘unprecedented sale’ of the paper, and Lord Salisbury’s admiration of Preston’s Conservative history drew a ‘jealous’ response from a Blackburn Tory paper. The Herald retorted with a brief history lesson on Conservative organisation in the town, and added a lament for the ‘sport of the old-fashioned sort’ in the days when the Stanley family led Preston’s social and political life.101 In fact the Stanleys who had sponsored racing and cock-fighting in Preston at the start of the century had actually been Whigs, but the Tory Herald assimilated them into a ‘fantasy’ place representation (to use David Harvey’s term) of Preston as a loyally Tory town, fond of traditional pleasures now defended by Conservatives against Liberal killjoys.102

Table 7.6: Use of ‘they’/’their’/’them’ (five most frequent meanings, %), in leading articles about Preston and in ‘Atticus’ columns.

|

% |

|

|

17 |

|

|

Revivalists |

11 |

|

9 |

|

|

Magistrates |

6 |

|

Parsons |

6 |

|

‘Atticus’ columns, April 1868 |

|

|

Parsons |

25 |

|

24 |

|

|

15 |

|

|

Tradesmen |

6 |

|

Reporters |

5 |

|

26 |

|

|

18 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

Commissioners |

7 |

|

32 |

|

|

Parsons |

10 |

|

10 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

8 |

When the three-fold increase in the amount of material published weekly by the Preston Herald is taken into account, the fourth column of Table 7.4 above suggests that the proportion of conflict, in this paper at least, greatly reduced during the period. But each newspaper was different: in Furness, the editor of the Ulverston Advertiser believed that ‘local dissensions are, in all cases, greatly to be deprecated’ while his opposite number on the Ulverston Mirror relished conflict as part of his anti-authority stance.103 One might expect even less conflict in a situation of local monopoly, as became the norm in the twentieth century, and further research on this point would be helpful.

For Preston’s papers, the most significant ‘other’ was the enemy within, showing the fractured nature of local identity, or rather identities. As sociolinguistic studies would predict, the pronouns ‘they’, ‘their’ and ‘them’ were used to distinguish in-groups from outsiders, ‘us’ from ‘them’’ in the endless conflict over Preston’s true identity (Table 7.6 below).104 These third-person plural pronouns denoted the political, moral and religious opponents — overwhelmingly local — of each paper. Such differentiation in order to create ‘an ingroup identity’, may be central to all mass media language.105 For Preston’s two Liberal, Nonconformist papers, the Chronicle and the Guardian, the ‘others’ were Preston’s parsons, Churchmen, Orangemen and Tory politicians. Table 7.6 shows the five most common uses of these pronouns in leader columns before and after Anthony Hewitson bought the Preston Chronicle, in his opinionated ‘Atticus’ columns, and in the leader columns of the rival Preston Guardian. Third-person plural pronouns were used more in Atticus columns than in the leader columns (18.1 occurrences per 1000 words for Atticus columns, 12.1–13.7 per 1000 words in leader columns). In Hewitson’s ‘Atticus’ columns, his leaders and those of the rival Preston Guardian, ‘they’, ‘their’ and ‘them’ have a negative meaning, occasionally neutral. ‘Atticus’ uses them heavily in his descriptions of Poor Law Guardians and parsons, less so for councillors, and very little in his sketch of Fishergate, which is peopled by ‘us’ — shopkeepers (Hewitson among them), shoppers, workers and market-goers. Describing some of the Guardians, he writes that ‘they prate and preach, and rant to poor people’ and of some young clergymen he says: ‘They have graduated at some fifty-fifth collegiate establishment’. But the tradition that leading articles are against rather than for something does not explain why ‘them’ is used negatively more in Hewitson’s opinion columns than his leaders, nor why there is little antagonism nor ‘othering’ in pre-Hewitson Chronicle leaders.106 In these articles, the ancient Romans and modern Prestonians are ‘them’, but a positive ‘them’. The writer has chosen subjects he can praise rather than condemn, and is more conciliatory and less opinionated, even on controversial topics such as the debate over whether to improve Preston’s port at ratepayers’ expense. This suggests that the technique of ‘othering’ was, in part, the editor’s personal choice.

Conclusions

Local identity is highly complex, constructed as it is from many different elements, layered and interconnected in different ways in each place. While local newspapers were only one among many factors involved in the development and promotion of local identity, they were involved in an explicit project of promoting and exploiting local patriotism. This may explain why local newspapers are used so heavily by historians in studies of local identity; when the rhetoric is taken at face value, the dangers are obvious. This chapter has built on the insights of Hill, Jones and Joyce to offer a detailed analysis of some techniques used by nineteenth-century local newspapers. Many of the techniques are so banal that they are rarely noticed, such as including the name of the town in the paper’s title. Others are more sophisticated, such as the ‘rhetorical web’107 woven by careful use of ‘we’, ‘our’ and ‘us’, for example. Newspapers also published visual images of the locality, labelled news items in a way that divided the world’s events into local, district, general or foreign news; published local and localised fiction and poetry, advertisements and history. The newspaper as a cultural form is well suited to the promotion of place identities, thanks to its iterative, repetitive nature, its ability to roll together many disparate elements of local identity, thereby increasing their power, and its ability to present highly constructed, artificial notions as normal and implicit, seen in its division of the world into ‘us’ and ‘them’. Defining local identity through differentiating from an external ‘other’ was present, but weakly expressed and not central to the Preston papers’ methods; the local press focused on ‘us’ far more than ‘them’. Othering may have been important in places with less established, or more embattled, identities, such as Barrow or Wales. In such places, the role of the local press in conjuring up Benedict Anderson’s imagined communities may have been more significant, too, than in more confident, established places such as Preston, where the official signs of geographical status were more visible and therefore less imagination was required.

The local press was a mirror and a magnifier of local events, but it also helped to shape local culture, becoming an institution in its own right, with its premises at the heart of the provincial town, collecting together the miscellaneous advertising previously published in other formats, and sponsoring sporting, musical and charitable endeavours. Provincial culture had managed without the press in previous ages, but it is hard to imagine late Victorian society functioning without the infrastructure it provided.108 Lee was unduly pessimistic when he claimed that, by the early twentieth century, ‘the press had become a business, not only first, but increasingly a business almost entirely, and a political, civil and social institution hardly at all.’109 Lee also underplayed the cultural function of the local press. The next chapter focuses in detail on one part of local culture, the use of dialect, and on how local papers used it to include and exclude, whilst combining their commercial and cultural roles.

1 Arjun Appadurai, Modernity At Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), p. 181.

2 Jeffrey Hill, ‘Rite of Spring: Cup Finals and Community in the North of England’, in Sport and Identity in the North of England, ed. by Jeffrey Hill and Jack Williams (Keele: Keele University Press, 1996), pp. 85–111 (p. 86); William Donaldson, Popular Literature in Victorian Scotland: Language, Fiction, and the Press (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1986), p. ix; J. Barry, ‘The Press and the Politics of Culture in Bristol 1660–1775’, in Culture, Politics, and Society in Britain, 1660–1800, ed. by Jeremy Black and Jeremy Gregory (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991), p. 49.

3 Jostein Gripsrud, Understanding Media Culture (London: Arnold, 2002), p. 232, https://doi.org/10.24926/8668.2601

4 Robert M. Entman, ‘Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm’, Journal of Communication, 43 (1993), 51–58 (p. 52), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

5 C. P. Scott, ‘A Hundred Years’, Manchester Guardian, 5 May 1921.

6 Andrew Marr, My Trade: A Short History of British Journalism (London: Macmillan, 2004), pp. 44–45; see also William Harvey Cox and David R. Morgan, City Politics and the Press: Journalists and the Governing of Merseyside (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), p. 1; Daniel J. Monti, The American City: A Social and Cultural History (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999), p. 5; F. K. Gardiner, ‘Provincial Morning Newspapers’, in The Kemsley Manual of Journalism (London: Cassell, 1952), pp. 204–5.

7 Hill, p. 86; see also Clifford Geertz, Available Light: Anthropological Reflections on Philosophical Topics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 193, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400823406; Aled Gruffydd Jones, ‘The 19th Century Media and Welsh Identity’, in Nineteenth-Century Media and the Construction of Identities, ed. by Laurel Brake, Bill Bell, and David Finkelstein (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000), pp. 322–23; John Duncan Marshall, ‘Review Article: Northern Identities’, Journal of Regional and Local Studies, 21 (2000), 40–48 (p. 41); Brad Beaven, ‘The Provincial Press, Civic Ceremony and the Citizen-Soldier During the Boer War, 1899–1902: A Study of Local Patriotism’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 37 (2009), 207–28 (p. 212), https://doi.org/10.1080/03086530903010350; Michael Bromley and Nick Hayes, ‘Campaigner, Watchdog or Municipal Lackey? Reflections on the Inter-War Provincial Press, Local Identity and Civic Welfarism’, Media History, 8 (2002), 197–212, https://doi.org/10.1080/1368880022000030559

8 Peter Fritzsche, Reading Berlin 1900 (London: Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 1; David McKitterick, ‘Introduction’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume 6, 1830–1914, ed. by David McKitterick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 12, https://doi.org/10.1017/chol9780521866248.002; Peter Clark, ‘Introduction’, in The Transformation of English Provincial Towns, 1600–1800, ed. by Peter Clark (London: Hutchinson, 1984), p. 45; David Eastwood, Government and Community in the English Provinces, 1700–1870 (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997), p. 73; Donald Read, The English Provinces, 1760–1960: A Study in Influence (London: Edward Arnold, 1964), p. 250; Michael Wolff and Celina Fox, ‘Pictures from the Magazines’, in The Victorian City: Images and Reality, Vol. 2, ed. by H. J. Dyos and Michael Wolff (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973), p. 559; Margaret Beetham, ‘Ben Brierley’s Journal’, Manchester Region History Review, 17 (2006), 73–83 (p. 75).

9 Patrick Joyce, Visions of the People: Industrial England and the Question of Class, 1848–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); see also John Duncan Marshall, The Tyranny of the Discrete: A Discussion of the Problems of Local History in England (Aldershot: Routledge, 1997), pp. 98–101.

10 Marshall, Tyranny, p. 105.

11 Dave Russell, Looking North: Northern England and the National Imagination (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), p. 274; Neil Evans, ‘Regional Dynamics: North Wales, 1750–1914’, in Issues of Regional Identity: In Honour of John Marshall, ed. by Edward Royle (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), p. 202.

12 Dave Russell, ‘The Heaton Review, 1927–1934: Culture, Class and a Sense of Place in Inter-War Yorkshire’, Twentieth Century British History, 17 (2006), 323–49 (p. 346), https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwl018; for the same point for early American magazines, see Robb K. Haberman, ‘Provincial Nationalism: Civic Rivalry in Postrevolutionary American Magazines’, Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 10 (2012), 162–93, https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2012.0001

13 Jones, ‘The 19th Century Media and Welsh Identity’.

14 Shmuel Shamai and Zinaida Ilatov, ‘Measuring Sense of Place: Methodological Aspects’, Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 96 (2005), 467–76, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00479.x

15 Christopher Ali, Media Localism: The Policies of Place (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017), p. 46, https://doi.org/10.5406/illinois/9780252040726.001.0001

16 Edward Royle, ‘Introduction: Regions and Identities’, in Issues of Regional Identity, pp. 2, 4.

17 Russell, Looking North, p. 246.

18 For a case study of one such mosaic, see Melanie Tebbutt, ‘Centres and Peripheries: Reflections on Place Identity and Sense of Belonging in a North Derbyshire Cotton Town’, Manchester Region History Review, 13 (1999), 3–20.

19 David Smith, ‘Tonypandy 1910: Definitions of Community’, Past and Present, 87 (1980), 158–84, https://doi.org/10.1093/past/87.1.158; compare, for example, the two lists of statement from Hull residents and outsiders in D. C. D. Pocock and Raymond Hudson, Images of the Urban Environment (London: Macmillan, 1978), p. 111. Equally, unpleasant events of national significance, such as the capture of Rohm and other ‘Brownshirt’ leaders by Hitler at Tegernsee in the Bavarian Alps, can be forgotten in the places where they happened, whilst remembered elsewhere: Geert Mak, In Europe: Travels through the Twentieth Century (London: Vintage, 2008), p. 269.

20 See also Pat Jess and Doreen B. Massey, ‘The Conceptualization of Place’, in A Place in the World? Places, Cultures and Globalization, ed. by Doreen B. Massey and P. M. Jess (Oxford: Oxford University Press/Open University, 1995).

21 David Gilbert, ‘Community and Municipalism: Collective Identity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Mining Towns’, Journal of Historical Geography, 17 (1991), 257–70 (p. 266), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-7488(05)80002-7; Royle, p. 5.

22 Jeffrey Goldstein, ‘Emergence as a Construct: History and Issues’, Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 1 (1999), https://journal.emergentpublications.com/article/vol1-iss1-1-3-ac/

23 Stephen Caunce, ‘Complexity, Community Structure and Competitive Advantage within the Yorkshire Woollen Industry, c. 1700–1850’, Business History, 39 (1997), 26–43, https://doi.org/10.1080/00076799700000144

24 When the Victorian Church of England was reorganised geographically, diocesan officials set out to build a sense of loyalty to the new dioceses by publishing calendars and almanacs among other methods. The contents of these publications were remarkably similar to the contents of local and regional papers of the same period: Arthur Burns, The Diocesan Revival in the Church of England, c. 1800–1870 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 111–14.

25 For the difficulty in untangling commercial and other motives, see Simon Potter, ‘Webs, Networks, and Systems: Globalization and the Mass Media in the Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century British Empire’, Journal of British Studies, 46 (2007), 621–46 (pp. 644–45), https://doi.org/10.1086/515446

26 Dave Russell, ‘Culture and the Formation of Northern English Identities from c.1850’, in An Agenda for Regional History, ed. by Bill Lancaster, Diana Newton, and Natasha Vall (Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University Press, 2007), p. 280. See, however, Marshall, ‘Review Article: Northern Identities’, p. 41; Jones, pp. 322–23. For the conceptual problems created by leaving local and regional identities undefined, and the reader perspective ignored, see David Berry, ‘The South Wales Argus and Cultural Representations of Gwent’, Journalism Studies, 9 (2008), 105–16.

27 Patrick Joyce, The Rule of Freedom: Liberalism and the Modern City (London: Verso, 2003), p. 125; Aled Gruffydd Jones, Press, Politics and Society: A History of Journalism in Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1993), p. 240.

28 Newspapers are strangely absent from an account of writing and place in Mike Crang, Cultural Geography (London: Routledge, 2004), pp. 44–45.

29 David Paul Nord, ‘Introduction: Communication and Community’, in Communities of Journalism: A History of American Newspapers and Their Readers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), pp. 1–27.

30 Rolfe Arnold Scott-James, The Influence of the Press (London: S. W. Partridge & Co., 1913), p. 27.

31 N. A. Phelps, ‘Professional Football and Local Identity in the “Golden Age”: Portsmouth in the Mid-Twentieth Century’, Urban History, 32 (2005), 459–80, https://doi.org/10.1017/s096392680500324x; Alan Metcalfe, ‘Sport and Community: A Case Study of the Mining Villages of East Northumberland, 1800–1914’, in Sport and Identity, pp. 13–40.

32 ‘To Our Readers’, Barrow Herald, 24 October 1863, p. 4; see also Frederic Carrington, ‘Country Newspapers and Their Editors’, New Monthly Magazine, 105 (1855), 142–52 (p. 147).

33 Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC), 5 October 1867, p. 4.

34 These geographical uses of first-person plural pronouns in newspaper discourse are not universal. In the twenty-first century, while they still mean British citizens and/or members of the local community when used in British national and regional newspapers, in Italy they generally include ‘the writer and the readers as human beings, rather than specifically as Italian citizens’: Gabrina Pounds, ‘Democratic Participation and Letters to the Editor in Britain and Italy’, Discourse and Society, 17 (2006), 29–64, https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926506058064; see also Rudolf De Cillia, Martin Reisigl, and Ruth Wodak, ‘The Discursive Construction of National Identities’, Discourse and Society, 10 (1999), 149–74 (pp. 160–64), https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926599010002002

35 Preston Guardian (hereafter PG), 22 December 1888, p. 4.

36 ‘Naming is showing, creating, bringing into existence’: Pierre Bourdieu, On Television and Journalism (London: Pluto Press, 1998), p. 31, cited in A. Paasi, ‘Region and Place: Regional Identity in Question’, Progress in Human Geography, 27 (2003), 475–85 (p. 480), https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph439pr; see also Tim Cresswell, Place: An Introduction, 2nd edition (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014), p. 15.

37 See also Jones, ‘The 19th Century Media and Welsh Identity’, pp. 315, 318–19.

38 This crucial point is missed in Henkin’s otherwise profound exploration of one city’s print culture: David M. Henkin, City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), p. 102.

39 Debbie Hodson, ‘Civic Identity, Custom and Commerce: Victorian Market Halls in the Manchester Region’, Manchester Region History Review, 12 (1998), 34–43 (p. 38).

40 John W. Reps, Views and Viewmakers of Urban America: Lithographs of Towns and Cities in the United States and Canada, Notes on the Artists and Publishers, and a Union Catalog of Their Work, 1825–1925 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1984), pp. 59–60.

41 Almanac given with PC, 2 December 1893.

42 Peter J. Lucas, ‘The First Furness Newspapers: The History of the Furness Press from 1846 to c.1880’ (unpublished M.Litt dissertation, University of Lancaster, 1971), p. 106.

43 Pamela K. Gilbert, Mapping the Victorian Social Body (Albany, NY.: State University of New York Press, 2004), p. 16.

44 Preston Herald (hereafter PH), 14 October 1893, p. 4.

45 Laurel Brake, ‘“The Trepidation of the Spheres”: The Serial and the Book in the 19th Century’, in Serials and Their Readers, 1620–1914, ed. by Robin Myers and Michael Harris (Winchester: Oak Knoll Press, 1993), p. 98.

46 PH, 29 September 1860, p. 3; PC, 1 June 1878, p. 2.

47 Published in instalments in the Accrington Gazette, January and February 1882, quoted in Ronald Y. Digby, J. C. Goddard, and Alice Miller, An Accrington Miscellany. Prose and Verse by Local Writers (Burnley: Lancashire County Council Library, Museum and Arts Committee, 1988), pp. 92–96.

48 David Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture: England 1750–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 214, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511560880

49 Brian E. Maidment, ‘Class and Cultural Production in the Industrial City: Poetry in Victorian Manchester’, in City, Class and Culture: Studies of Cultural Production and Social Policy in Victorian Manchester, ed. by Alan J. Kidd and Kenneth Roberts (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985), pp. 148–66 (pp. 158–59); Andrew Hobbs and Claire Januszewski, ‘How Local Newspapers Came to Dominate Victorian Poetry Publishing’, Victorian Poetry, 52 (2014), pp. 80–83, https://doi.org/10.1353/vp.2014.0008; Kirstie Blair, ‘The Newspaper Press and the Victorian Working Class Poet’, in A History of British Working Class Literature, ed. by John Goodridge and Bridget Keegan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

50 Buchan Clown 1 August 1838, p. 47, cited in Donaldson, p. 73.

51 The serials began in PC, 22 October 1864; in PG, 17 December 1887, p. 10.

52 Graham Law, ‘Imagined Local Communities: Three Victorian Newspaper Novelists’, in Printing Places: Locations of Book Production & Distribution since 1500, ed. by John Hinks and Catherine Armstrong (London: British Library, 2005).

53 PG, 22 December 1888, p. 4. Hull also wrote the ‘The “Guardian” Jubilee Song’, sung to the tune of ‘The Old Ash Grove’, in celebration of the newspaper’s 50th anniversary: Jubilee supplement, PG, 17 February 1894, p. 16; LEP, 29 December 1888.

54 Graham Law, Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000), p. 190.

55 Catherine Waters, ‘“Much of Sala, and but Little of Russia’’: “A Journey Due North,” Household Words, and the Birth of a Special Correspondent’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 42 (2009), 305–23 (p. 310), https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0090; for an example by Anthony Hewitson, see ‘Atticus’ [Hewitson], ‘Our principal street on the principal day,’ PC, 25 April 1868.

56 PH, 8 October 1890, p. 7.

57 An Accrington Miscellany was first published in 1970 ‘to witness to [Accrington’s] life and culture’ at a moment of civic crisis, the imminent abolition of Accrington Municipal Borough Council. Commissioned by the Libraries and Art Gallery Committee, its material comes chiefly from Accrington’s local press, thereby acknowledging these publications, in the words of Jones, as ‘an essential component of a community’s identity, its remembrancer’: foreword and acknowledgements, Digby et al; Jones, Press, Politics and Society, p. 8.

58 Kristy Hess and Lisa Waller, Local Journalism in a Digital World: Theory and Practice in the Digital Age (London: Palgrave, 2017), p. 110.

59 PC, 4 April 1868, p. 2; see also ‘The War — Letter from a Prestonian in Belgium’, PC, 24 September 1870, p. 5.

60 See also ‘Letters from Prestonians in America’, PC, 11 September 1875, p. 2. This local press technique was a significant genre of war reporting during the First World War: Mike Finn, ‘The Realities of War’, History Today, 52 (2002), 26–31.

61 R. L., ‘The English excursion to South Italy’, Birmingham Daily Post, 19 October 1860.

62 John Macklin Eyre, ‘Letter from Capua’, Newcastle Courant, 23 November 1860.

63 ‘Sketches from Stamboul’, by ‘One of Our Staff’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 23 January 1877, p. 2.

64 Lucy Brown, Victorian News and Newspapers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), p. 20.

65 Scott-James, p. 121.

66 Maurice Milne, ‘Survival of the Fittest? Sunderland Newspapers in the Nineteenth Century’, in The Victorian Periodical Press: Samplings and Soundings, ed. by Joanne Shattock and Michael Wolff (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1982), pp. 193–223 (p. 195); Maurice Milne, The Newspapers of Northumberland and Durham: A Study of Their Progress during the ‘Golden Age’ of the Provincial Press (Newcastle upon Tyne: Graham, 1971), p. 133; Jones, Press, Politics and Society, p. 69.

67 The 1838 returns also show that Chartist newspapers had significant amounts of advertising, challenging the view of Curran and others that they operated outside the commercial market: James Curran, ‘The Industrialization of the Press’, in Power Without Responsibility: The Press and Broadcasting in Britain, ed. by James Curran and Jean Seaton (London: Routledge, 1991), pp. 32–48 (p. 39).

68 1839 (548) Return of Number of Stamps issued to Newspapers and Amount of Advertisement Duty, 1836–38; Enumeration abstract, 1841 Census, p. 465.

69 Catholic News, 4 January 1890, p. 8; see also Alison Toplis, ‘Ready-Made Clothing Advertisements in Two Provincial Newspapers, 1800–1850’, International Journal of Regional and Local Studies, 5 (2009), 85–103 (p. 99), https://doi.org/10.1179/jrl.2009.5.1.85; for local identity in advertising poetry, see Kirstie Blair, ‘Advertising Poetry, the Working-Class Poet and the Victorian Newspaper Press’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 23 (2018), 103–18.

70 Brian Garrett, ‘Personal Identity’, in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Taylor & Francis), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780415249126-V024-1

71 Amanda Vickery, ‘Town Histories and Victorian Plaudits: Some Examples from Preston’, Urban History Yearbook, 15 (1988), 58–64 (pp. 58, 63), https://doi.org/10.1017/s0963926800013924; see also Pocock and Hudson, p. 82.

72 Alexander Paterson, ‘Provincial Newspapers’, in Progress of British Newspapers in the Nineteenth Century (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., 1901), pp. 79–80.

73 M. Janowitz, The Community Press in an Urban Setting (Glencoe: Free Press, 1952), p. 71.

74 For more on obituaries, see Bridget Fowler, ‘Collective Memory and Forgetting: Components for a Study of Obituaries’, Theory, Culture & Society, 22 (2005), 53–72, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276405059414

75 Vickery, pp. 59–60; Doreen B. Massey, ‘Places and Their Pasts’, History Workshop Journal, 39 (1995), 182–92 (p. 186), https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/39.1.182; leader column, PH, 15 September 1860, p. 4; see also PC, 9 October 1853, p. 4, 7 June 1879, p. 6. There was similar mockery of Ulverston’s lack of development in the Barrow press.

76 ‘The Burnley Antiquary’, Burnley Advertiser, 17 January 1880.

77 Burnley Advertiser, 17 January 1880.

78 Alfred Thomas Gregory, Recollections of a Country Editor (Tiverton Gazette, 1932), p. 15.

79 Anon., A Century of Progress 1844–1944, Southport Visiter (Southport: Southport Visiter, 1944), p. 1; Rendezvous with the Past: One Hundred Years’ History of North Staffordshire and the Surrounding Area, as Reflected in the Columns of the Sentinel, Which Was Founded on January 7th, 1854 (Stoke-on-Trent: Staffordshire Sentinel Newspapers, 1954), p. 8. Both these newspapers claimed to be instrumental in achieving the incorporation of their towns.

80 This account of local paper boosterism in Barrow is taken from Lucas, ‘First Furness Newspapers’, pp. 99, 105, 113, 119.

81 Lucas, ‘First Furness Newspapers’, pp. 100–1, 109. Likewise, the Barrow Advertiser & District Reporter’s motto was ‘Prosperity to Barrow’. For the more extreme version of boosterism seen in frontier America, see David Fridtjof Halaas, Boom Town Newspapers: Journalism on the Rocky Mountain Mining Frontier, 1859–1881 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1981).

82 Lucas, ‘First Furness Newspapers’, pp. 100–1.

83 PH, 7 July 1855.

84 PH, 1 September 1860; PG, 22 September 1860; PC, 5 October 1867.

85 PH, 3 September 1890.

86 PH, 17 October 1900, 23 October 1880.