8. Class, Dialect and the Local Press: How ‘They’ Joined ‘Us’

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.08

Moses Cocker, the vice-chairman of Blackburn Board of Guardians, delivered himself in the barbarious [sic] dialect of the district, which was rendered literally by Mr Brooks, the then editor and reporter for the Blackburn Mercury1 […] Mr Lumley [a Poor Law inspector] came down from Somerset House when Moses was upholding the law at the Board of Guardians.2 When Mr Lumley entered the Board-room he was sainted by Moses holding up and shaking his giant hand and saying to him, “Pousy jackanapes, if I hev ever to set thi limbs o’ll mek um crack.” To Mr Lumley this threat was just so much Latin. An applicant for relief next presented herself, when Moses said, “Tha coms fro Tockholes, o’ll gether thee some brass — thart a daysent lass, and so is thi mother.” These words were addressed to Isabel Holden, a “lass” that was 76 years of age, and the “lass” alluded to as her mother was 93 […] To listen to Moses Cocker giving evidence, amounted to the pursuit of knowledge under great difficulties, for every sentence had to be transposed into English by the advocate employed, who had to turn interpreter […] One day Moses met Mr Brooks and asked him if there was anything he could “tice” him with. His family felt very keenly that he (Mr B) made him into a public laughing stock by not writing his speeches “gradely.” He would give him anything to be thick with him. Mr Brooks replied that it was the province of the press to show up the shortcomings of public men, and he then turned on his heel.3

This passage from an anonymous memoir, serialised in the Preston Chronicle, describes an editorial decision taken in the 1840s, to render the speech of a Blackburn public figure, Moses Holden, as Lancashire dialect. In later years, local and regional dialects became an established provincial newspaper technique for profiting from local patriotism and playing down class differences. But before then, dialect was used more divisively, as in the passage above, to emphasise social and moral difference. The deployment of dialect, as with other techniques for promoting and profiting from local identities, was self-conscious, considered and highly constructed.

This chapter shows how local papers in Lancashire went from using dialect largely as a class marker, to embracing its potential to hide class differences and emphasise the common ground of local identity. This was part of newspapers’ adaptation to an expanding working-class readership. These readers had previously been positioned as eavesdroppers on middle-class newspaper conversations, but in the last decades of the nineteenth century, they moved from reading and listening, to purchasing and therefore influencing local newspapers and their content. Place trumped class in the changing discourse of local newspapers, as a theoretically neutral technique — dialect — was used to include rather than exclude. This was part of complex changes in the relationship between spoken and written language, and the crossover between literary and journalistic techniques. In all of this, the differentiated local markets of the provincial press, and their position at the heart of distinctive local cultures, gave them a commercial advantage over London newspapers.

Moses Cocker, the subject of the reminiscence that opens this chapter, was a tenant farmer (a middle-class occupation) who practised the ancient art of bone-setting (continued today by chiropractors and osteopaths), on the fringes of orthodox medicine, and seen as a craft rather than a profession. He was the vice-chairman of a local government body responsible for Poor Law administration, but he did not receive the respect usually accorded to men of his position and class. Other Poor Law Guardians treated him differently, addressing him as ‘Moses’ rather than ‘Mr Cocker’.4 He was a local character, generous with ratepayers’ money when demanding food and drink for himself at the workhouse, but also generous with his own money and time. He was happy to accept hospitality from tradesmen bidding for workhouse contracts, and resisted attempts by liberal Guardians to admit the press to meetings of the Guardians. All of this may have led the radical Blackburn Mercury (and its Tory rival, the Blackburn Standard) to render Cocker’s dialect literally in their reports. This was an established journalistic technique, of embarrassing a speaker by refusing to perform the usual editorial tidying-up of speech ready for print. In 1870 a writer in the Printers’ Register recalled how

we once heard a very ungrammatical councilman gravely bring it before the town council as a grievance that a certain reporter had, with malice aforethought, put into the newspaper a verbatim report of one of his speeches.5

It was not unusual for nineteenth-century middle-class Lancashire professionals to speak in dialect; what is noteworthy here is that it was ‘rendered literally’ by the newspaper, suggesting that the orthography was a matter of editorial choice, and that it was usual for newspapers to ‘translate’ the dialect of middle-class speakers into the higher-status variety of Standard English.6 This editorial policy irked Mr Cocker and his family, making him a ‘public laughing stock’, not because he spoke in dialect, but because this oral form was maintained in print, usually a marker of the speaker’s working-class status. The editorial policy was adopted to highlight Mr Cocker’s ‘shortcomings’ as a Poor Law Guardian. However the speech of other Guardians associated with the same corrupt practices was not rendered in dialect. Perhaps Moses Cocker was monolingual, unable to use any kind of English other than Lancashire dialect, whereas men of his position were expected to have the cultural capital that went with bilingualism or, in the terminology of linguistics, style-shifting.7 ‘Use of dialect was designed to produce a comic effect and also create distance between the object of humour and the reader (who possessed, by implied contrast, a command of flawless, standard English).’8

Mr Cocker’s monolingualism contrasts with the ability of the advocate in court, who was able to ‘transpose into English’ the evidence given in dialect by Mr Cocker, in cases of personal injury. There are two further clues to the strategy adopted by the newspaper: first, the incomprehension of the London Poor Law official at Mr Cocker’s dialect greeting, illustrating how ‘language is an instrument of both communication and excommunication’, a method of inclusion and exclusion, in this case a marker of status;9 second, the graphic, vivid, robustly affectionate register of much Lancashire dialect, exemplified in the promise of Mr Cocker, a local functionary of the central state, to ‘gether thee some brass’. From a literary perspective, it is clear why journalists seized on such snatches of dialect, because of their communicative and emotional power. Reporters used dialect speech as a literary technique, in the same ways as novelists such as Elizabeth Gaskell, and aimed for similar effects.

A Typology of Dialect in Lancashire Newspapers

This discussion of Lancashire dialect follows the definitions used by Dave Russell, taken from current mainstream thinking in linguistics:

“Dialect” is defined here simply as a regional variant of a language that also has a standardised and thus more prestigious form […] dialects are not debased or incorrect versions of “Standard English” but valid linguistic systems derived from Old English, Norse and Norman roots and possessing their own distinctive accent, vocabulary and grammar. Standard English is itself a dialect but one which, through association with the nation’s geographical and social power bases, has come to dominate, first of all in print from the late fifteenth century, and increasingly in spoken form from the late eighteenth.10

Accent is only part of dialect, and it is possible to deliver the syntax and vocabulary of Standard English with a pronounced accent, as did Friedrich Engels and three-times Prime Minister Lord Derby, for example.11

The use of dialect has been examined systematically in those Lancashire newspapers digitised in the British Newspaper Archive database.12 Dialect passages were identified by searching for three common words, ‘skrike’ (to shriek or scream), ‘anenst’ (opposite or against) and ‘gradely’ (meaning good, proper, right); this elicited 277 articles containing at least 1 of these words between 1830 and 1899. Each article was examined, and the use of dialect grouped and classified. The growth over time in the number and physical size of newspapers included in the BNA, and this database’s patchy coverage, was controlled for by dividing instances of dialect by the number of pages digitised in each decade. A rough estimate of the number of pages was gained by searching for a common word, ‘Mr’, which appeared approximately 4.25 times per page.

The layering of newspapers as texts is revealed in the processes leading to the appearance of dialect in print. The writing of dialect prose or fiction, for publication, was less mediated than most forms (although of course it emerged from a tradition and set of genres already familiar to local readers and writers). However, when a witness gave evidence in court, using dialect, and this was reported verbatim, there were two stages, the speaking and the writing. It was also fairly common to see a three-stage process, when an individual spoke in dialect, perhaps at the scene of a crime; these words were then described in court by a witness, also in dialect, before again being reported verbatim by a newspaper reporter. As we will see, considerations of class came into play more in the second and third instances than in the first.

Analysis of the 277 instances of Lancashire dialect reveals 3 main types: first, dialect in reported speech; second, dialect words and phrases used alongside Standard English in writing such as letters and travelogues written for publication and the editorial voice of the newspaper; and third, the established genre of dialect writing, encompassing poetry, prose and non-fiction. This typology can be subdivided into 8 distinct usages, a wider range of dialect genres than previously acknowledged (see Table 8.1 below).

Table 8.1. A typology of Lancashire dialect usage in local newspapers, 1830–99.

|

1. |

Reported speech |

|

1a |

Reported speech, court case defendant or witness |

|

1b |

Reported speech in news/feature article |

|

1c |

Reported speech in reader’s letter |

|

1d |

|

|

2. |

Writer’s own words |

|

3. |

|

|

3a |

|

|

3b |

|

|

3c |

In the first genre of dialect in the local press, reported speech, the original speaker has no control over the literal, cultural and social meanings of their speech once it has been noted by a reporter and published in a newspaper. Dialect used in this way had a low status, and was associated with working-class speakers and ‘country bumpkins’, regardless of the fact that it was also spoken by people of all classes, in both urban and rural areas.

The most common use of dialect in reported speech was in court reports, or ‘Police Intelligence,’ as the columns of Police Court cases were headed. The word ‘skrike’ often appeared in evidence in court, for obvious reasons:

He married my sister, and on Sunday last, I heard her skriking out, un I went in un I knocked im deawn […]13

He was so smothered that he could neither see nor speak, and “skriked out murder”.14

Less often, the more positive word ‘gradely’ also appeared in court reports, as when a wife was reported by a witness as having encouraged her husband to hit a schoolmaster, urging her spouse to ‘give it him gradely […]’15 In another case, Thomas Kershaw, ‘charged with being drunk and riotous, in extenuation pleaded that he was not “gradely” drunk.’16 As with Moses Cocker’s colourful turn of phrase, the decision to include the dialect word may have been taken to enliven a court report; but it was also a decision to emphasise the class of the speaker. For other people in the same courtroom, a different decision was made, to translate their dialect into Standard English.

Dialect in reported speech was sometimes used to demarcate another distinction, that between the town and the less sophisticated countryside. In 1835 ‘a simple looking countryman’ told a Liverpool court: ‘I skriked out “Murder”, but that lass there told me if I did not hold my din she would cut my bloody throat’.17 In 1845, under the heading ‘Fiddling, otherwise diddling a country bumpkin’, the court report rendered all the evidence of the complainant — a rural fiddle-player cheated out of two violins — in dialect, interspersed with ‘(loud laughter)’, ‘(renewed laughter)’ and ‘(roars of laughter)’.18 The heading invites the reader to join in the merriment by laughing at simple country folk. Dialect speech was often used for comic effect in court reporting, as with many working-class characters in Dickens, giving a clear invitation for the reader to look down on the speaker.19

When dialect in speech was reported outside court, the social range of the speakers was wider, as were the social meanings of dialect use. In the passage below, headed ‘AN ORATOR OF THE WORKING CLASS,’ a report of a public meeting in Bury in 1841, published in the Preston Chronicle and reprinted from the Bolton Free Press, features the ‘extraordinary speech of an Anti-Corn Law Tim Bobbin’.

[…] Henry Rostron, a working man, from Radcliffe-bridge, came forward to address the meeting. His speech, which was full of wit and humour, set the whole assembly laughing like to split their sides. “Ye mun kno,” said he, “yesthurday wur th’ day for choosin’ kunstables i’ eawr place, un th’ rate-payurs han chosn me ogen. Neaw, wen aw went ofore th’ paason o’ Ratcliffe, who’s no gud will to th’ Repeelers, he sed as he oped to see me at th’ church ofthur nur aw ad bin latly. Aw towd im awd mey noan sitch promisus o’ that swort, but awd goo a deeol aufthur if he’d preytch i’ favur ov’ a gud ballyful o’ beef for th’ workin’ mon. (Cheers and laughter.) Thoose ut ud pinch th’ ballies o’ th’ poor wud n’t do mitch gud to their sowls. (Renewed laughter.) Th’ clergy tell’n me ut aw mun hev o kreawn o’ glory wen awm deeod, iv awl behaive gradely; boh aw oalus say ut awd loik to ha summut to be gooin on wi meon whioile. (Roars of laughter and cheers.) […] Aw wur tellin yo abeawt choosin t’kunstables yesthurday. Well, afthur it war o’er, we’d o rare gud dinnr. Thir wur plenty o’ beef, un plenty o’ summat ut they koed church puddin. (Laughter.) Yo mey leawf, but its o foine thing is that church puddin; un, moor nur that, its mey opinion, un aw towd th’ paason, if teyd o sitch a dinnur us that, wi church puddin, it ud kill o’ th’ Chartists i’ th’ kunthry. (Great cheering and laughter.) […]’20

In contrast to the court reports, there is clear admiration for the wit and style of the speaker, and the reference to the revered eighteenth-century dialect writer ‘Tim Bobbin’ (pen-name of John Collier, 1708–86) enhances the speaker’s status. This report is a complex text: a skilled dialect speaker, reported by a skilled dialect writer; the Anti-Corn Law line of the speech is in tune with the Bolton Free Press but goes against the editorial policy of the Preston Chronicle which reprinted it; the speaker is working-class, but is not stigmatised for this (perhaps because his respectability was guaranteed by his position as constable, and his rejection of Chartism); the inclusive, cross-class register of Lancashire dialect is here turned into a class weapon, or more precisely, as a weapon of the virtuous poor against the idle and immoral rich.21 As a rhetorical device, spoken or written, dialect was well suited to mocking pomposity and challenging social status. However, as Vernon notes, the dialect speech of middle-class speakers was more likely to be transcribed into ‘Queen’s English’, apart from the heckles of the working-class crowd. Vernon sees this as a sign of the closer association between Standard English and power, and the growing power of print over oral media.22

Occasionally, upper- and middle-class speakers from outside Lancashire would use dialect to say, ‘I’m the same as you’ to a working-class Lancashire audience, like US President John F. Kennedy telling a Berlin crowd, ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’. In 1885, Lord Harris, an Eton-educated baron, told the annual soiree of the Oldham Conservative Working Men’s League that ‘he knew that the Lancashire “gate” [crowd] was always of the “gradely” character, and that it would give him a fair hearing. (Laughter and applause.)’23 A year before, a newly arrived clergyman used dialect in the same way, to play down class differences and pay homage to local patriotism. Rev Mr Gordon, vicar of Goosnargh, speaking at the 1884 anniversary celebrations of a friendly society, said that

[he] had not been long in Lancashire, and had not got their lingo off, but he fancied they were something like “jannock.” (Laughter.) He could only say in conclusion that he had been enjoying himself “gradely.” (Loud laughter and applause.)24

Bourdieu’s phrase ‘strategy of condescension’ seems appropriate here.25 Why did the audience laugh? Was the incomer’s use of their language merely a pleasant surprise? Or was it mocking laughter, at a blatant attempt to patronise them? Russell believes that such ‘unifying narratives’ of regional identity, expressed here through the middle-class outsider’s use of the language of his working-class audience, were used ‘consciously or otherwise, to maintain social advantage.’ Such ‘modes of northernness’ were used ‘by the northern middle and upper classes in their attempts to manage the field of class relationships.’26

However, it appears that dialect was part of the native tongue, to varying degrees, of many middle-class people, and was occasionally used in formal situations, for effect.27 A report of an 1865 meeting of the Bedford Local Board, Leigh, Lancashire, records how discussion turned to paying for new sewers:

Mr Birchall: I wonder if you would allow it if you [had a financial interest in the affected properties]. — Mr Horrocks: He would “skrike” hard enough. (Laughter.) — Mr Birchall: There is not a man in this Board-room that would “skrike” harder.28

The speaker, John Horrocks, could be classified as lower middle class — a farmer’s son, a baker and provision dealer, a ‘staunch Conservative and Churchman’ who had been a special constable during the time of local Chartist riots, and had kept his truncheon as a souvenir. His obituary claimed that ‘he was highly respected in the town’.29 The laughter suggests that dialect was not usually spoken in public, formal settings such as a local government meeting, by respectable people such as Horrocks. There is also an overtone of mockery, suggesting the word may have associations with schooldays, childhood or play, which would diminish the person associated with the word. A famous example from the 1980s was British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s mocking taunt that political opponent Denis Healey was ‘frit’ (frightened).30 In 1893, another lower-middle-class figure, a court clerk, insisted that a man prosecuting two women for stealing £20 from him should use the correct dialect term. Samuel Fielden, a draper, told the court that one of the women started screaming when he accused her of theft:

The Clerk: What kind of screaming was it? Was it crying or skriking out? Prosecutor: Skriking out. The Clerk: Why don’t you use the correct term?

Sympathetic middle-class characters adopting dialect are sometimes found in nineteenth-century fiction, such as Hiram Yorke in Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley (1849) and Margaret Hale in Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1854–55). Towards the end of the century, Stephen Caunce believes that in Northern England, ‘the middle class muted their speech […] increasingly not fully part of their local culture yet not able to live out their class ideal in a satisfactory way. Northernness was thus becoming […] a spoiled version of a generally accepted unitary national ideal.’31

Further evidence comes from the contrasting treatment of Preston town councillors in news reports of council meetings and the light-hearted sketches of Preston Chronicle reporter and subsequent editor, Anthony Hewitson. While the middle-class professionals and tradesmen who sat on the council spoke Standard English in the news reports, in Hewitson’s 1868 sketch, ‘Preston Roundabout’, on ‘Our Town Council and its Members’, the same people, in the same meetings, are portrayed as speaking in dialect. Hewitson, writing under his pen-name Atticus, describes the reporters struggling with the councillors’ ‘bad grammar’, and suggests that

it is probable that one of [the councillors] at least, if asked on the way whether he has been at the meeting, will sapiently reply “I were”; and if he has said anything at it he will, on the following Saturday, quiz the newspaper report, examine his utterance, and genially whisper to himself the old tale of expressiveness, “Them’s my sentiments.”32

Hewitson’s irreverence was part of his pioneering adoption of New Journalism techniques in Preston, but he was careful to avoid naming the perpetrators of ‘bad grammar’, thereby reducing the damage to any individual’s middle-class status. Of course, many readers would have heard the councillors speak, and would know full well that they used dialect.

The next usage of dialect, as reported speech in readers’ letters, appeared occasionally towards the end of the period surveyed. Here, dialect was used in the same way as in light-hearted news articles, to add vivacity and verisimilitude, and the dialect speaker quoted was almost always working-class. The journalistic technique of using quotes to reveal individuals’ emotions was used, as in the letter below, reprinted in the Preston Chronicle from the London monthly The Quiver, describing the pleasure of textile workers in a village near Blackburn at the sight of a waggon full of raw cotton, at the end of the Cotton Famine in 1864:

Round this ungainly lurry a crowd of hundreds was gathered. Men laid their hands on the huge, and to us unsightly, parcels with a loving touch, and as though greeting an unlooked-for friend who had long been given up for lost. Others gave the bags a hearty slap, and added, “Hey, owd chaps, but I’m fain to see yo agen.”33

In other instances, the dialect speaker was implicitly commended by the correspondent for making a sound, commonsense point, the dialect once again emphasising down-to-earth practicality.

The fourth setting for reported dialect speech, in non-dialect fiction or poetry, has already been discussed briefly, with reference to middle-class characters in Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell (Mrs Gaskell’s husband published two lectures on the history of Lancashire dialect).34 This was a breach of novelistic practice, which had previously decreed that ‘narrators and other middle-class characters used only “good” or “standard” English’.35 This usage more commonly tended to denote working-class, uneducated or rural characters, but not always unsympathetically.

These speakers, whose words were reported by someone else, had far less control over how their words were used (often against them) than writers, who interspersed dialect words or phrases with Standard English. This usage also tended to appeal to the common-sense associations of dialect, as in a letter from W. Streight in 1872, using a local hero’s exclusion from a civic function to make a dig at the poor creditworthiness of some Preston dignitaries:

[…] Well, all I have to say is this, that if he cannot get invited to the Mayor’s garden party he can do this, at all events, namely, keep agate paying his debts, and that is more than some of the heavy swells can do who were present.36

Another letter, supporting Russia against Turkey in 1877, uses the inclusive undertones of the word ‘gradely’ to add emotional power to the writer’s argument:

[…] “Do unto others as thou wouldst have others do unto thee” was never intended to guide our dealings with such people as the Mahommedans. Not a bit of it. They are not “gradely” people you know […]37

As with other techniques for promoting and profiting from local identities, dialect appeared in local newspaper advertisements. A Liverpool bakery selling a foreign delicacy, ‘Yorkshire parkin’, used Yorkshire dialect to establish the authenticity of its cake. The advert included a testimonial ‘signed by a Live Yorkshireman […] given verbatim et literatim’ confirming that the parkin was the genuine article.38 Throughout 1865 Ralph Holden, a Burnley tailor, used dialect in doggerel advertising his goods on the front page of the Burnley Advertiser, while the tea sold by Preston’s Consumer Tea Company in 1875 was advertised as ‘gradely’, of course.39 In 1895 a small ad in a Blackburn paper offered ‘gradely lodgings for two gradely lads’ (Fig. 8.1).

Fig. 8.1. Dialect word in classified advertisement, Blackburn Weekly Standard & Express, 12 October 1895, p. 4. Author’s transcription, CC BY 4.0.

In later years this interspersing of Standard English and dialect was also used occasionally by the editorial voice of local newspapers, for its commonsense associations and to establish the publication as local. The Burnley Express columnist ‘Sportsman’, commenting on the new committee of Burnley Football Club, wrote in 1895: ‘I hope the management will act in unity, and, as the old saying goes, “shape gradely.”’40

The most prestigious use of dialect went beyond journalistic writing to claim the status of literature, whether poetry, fiction or non-fiction. When used in literary genres, or as part of a bilingual written vocabulary clearly showing the writer’s mastery of Standard English, the status of dialect was almost equal to Standard English.41 The standing of dialect literature can be seen in the Papers of the Manchester Literary Club for 1893, in which a highly complimentary paper on Edwin Waugh’s dialect poetry is sandwiched between papers on Shelley’s lyrics and Macbeth. Here, status or social class was not an issue.42

Most local newspapers carried some dialect writing, making them central players in this literary market, alongside other middle-class patrons of the genre. This was part of their broader role as a major publishing platform for poetry and many other genres.43 Newspaper editors and journalists were involved in local literary cultures, nurturing, publishing and critiquing the poetry and prose of local writers, when they were not writing it themselves. F. B. Peacock of the Manchester Examiner & Times was the first to publish Lancashire’s most famous dialect poem, ‘Come Whoam to thi childer an’ me’, by Edwin Waugh; John Harland, a reporter and partner in the Manchester Guardian, published articles on dialect poetry in 1839 and wrote extensively on Lancashire’s culture, later compiling The Ballads and Songs of Lancashire and Lancashire Lyrics. In Blackburn, William Abram of the Blackburn Times was a great enabler of that town’s working-class literary culture, much of it written in dialect.44

Lancashire and Yorkshire produced more dialect literature than any other part of England, published in broadsides and ballad form, pamphlets, newspapers, books and almanacs, and read, or performed, in public and at home.45 Below is an example of dialect poetry published by the Preston Chronicle, reprinted from the Manchester Guardian, and signed ‘”J. D.”, Preston.’ The poem was published during the Cotton Famine, when many Lancashire mills closed due to a trade glut and the disruption of the American Civil War. The crisis was seen at the time as a cross-class disaster for Lancashire, although mismanagement by mill owners played a large part in it.

A’ARE FACTORY’S GOOIN’ TO BEGIN.

We’est manidge, owd lass, to poo throo,

If we’ll nobbut howd eawt a bit lunger;

Tho’ it hez bin’ a terrable doo,

We’an hed wi’ starvation un hunger.

Baw gum! when aw luk i’ thi face,

Un see thi so haggert un thin,

Mi hart welly brasts, aw confess,

Un th’ wayter will rise to mi e’en.

[…]46

It is typical of the dialect literature published in local newspapers, in its domestic focus, its sentimentality and its stoic acceptance of the status quo. Salveson believes that writers selected their more non-political pieces for submission to local papers.47 There is a similar lack of political questioning, alongside a belief in the shared interests of capital and labour, in the poor-quality piece of prose below, from 1878, at the end of a pay dispute in which workers had been locked out of most Preston mills.

EAUR FOLKS WUR LOCKED OUT, BUT THEY’N GETTEN TO THEIR WARK AGAIN.

(By a Weaver’s Wife.)

[…]

Whatever should we ha’ done but for those good, kind ladies an’ gentlemen, who so nobly come forrad wi’ a helpin’ hond — awm not th’ only one who says “God bless ‘em, and may they never know what it is to want what they connot get till they go to their reward i’ heaven.” Awst taich my childher to pray for ‘em aw th’ days o’ their lives […] Thoose waistrils ‘at went about riotin’ wanted eaur Josh to jine ‘em, but he said he’d rather clem fust. He towd ‘em plainly they wur nowt but a pack o’ foos to goo about desthroyin’ what wur like their own property — it wur like chopping their own legs off, so as they couldn’t walk. They said if th’ mesthers wouldn’t oppen th’ mills they’d brun ‘em down. Eaur Josh towd ‘em ‘at him, an’ a few moor, meant to keep a sherp watch on their facthry an’ it shouldn’t be set on fire beaut somebody knowin’.48

It is quite possible that the author of the piece above was indeed ‘a Weaver’s Wife’, but it is equally possible that it was written by a reporter or other member of the Chronicle staff, as it chimes with the paper’s editorial attitude to the dispute. In this passage, the employers’ point of view has been put clearly, but clothed in the accent and dialect conventionally assigned to workers. It uses local patriotism to appeal for consensus. Dialect writing was often harnessed in this way, appealing to cross-class interests by exploiting its down-to-earth, common-sense register.49 Peter Lucas has shown that much dialect writing in the newspapers of Furness, in the far north of Lancashire, was produced by employees of the publications, in one case, three individuals sharing a pseudonym.50 But some dialect literature appears to come from readers.

Certain papers published in south and east Lancashire, the heartland of Lancashire dialect, solicited readers’ contributions to the genre. In Blackburn, the rival Radical Times and Conservative Standard both supported the town’s thriving working-class literary culture.51 In the 1870s the Standard had a reader competition (as did the Burnley Advertiser), while the Blackburn Times often published half a page of dialect literature per issue, featuring the town’s roster of poets plus Lancashire’s most famous nineteenth-century dialect writer, Edwin Waugh.52 Waugh’s most famous poem, ‘Come Whoam to thi childer an’ me’, was the subject of a reader’s prize essay in the Blackburn Standard of 1895; the paper also ran a weekly competition for the ‘best anecdote or short Lancashire sketch’ in the same year.53

Dialect was less often used as a mocking marker of class in newspapers where there were vibrant working-class literary cultures, such as Blackburn or Burnley. Table 8.2 below provides a rough comparison of how dialect was used in two different towns (each represented by two newspapers in the BNA database). Blackburn, with its exceptional literary culture, treated dialect mainly as a literary form, allowing working-class writers to speak for themselves. In contrast, in the Preston papers, working-class users of dialect were more likely to be objects of derision than subjects with agency.

Table 8.2. Usage of Lancashire dialect in Blackburn and Preston, 1840s–90s.

|

31 |

10 |

|

|

12 |

25 |

|

|

In news/feature articles |

4 |

14 |

|

In court reports |

8 |

10 |

|

Writer’s own words |

2 |

1 |

Change Over Time

The use of dialect in local papers also changed over time, with a move away from using it as a class marker, towards using it in cross-class ways. Table 8.3 below confirms a boom in dialect literature from the 1840s onwards, with fiction first, followed by poetry and non-fiction (typically comic correspondence on local and national issues) later.54 The use of dialect in the reported speech of defendants and witnesses peaked in the 1840s and declined steeply thereafter. Donaldson believes that Isaac Pitman’s breakthrough in rendering the sound of language rather than its spelling in his shorthand inspired dialect writers to experiment with orthography from the late 1830s onwards.55 The use of reported dialect speech in other news reports and feature articles peaked in the 1850s and ‘60s, and it is tempting to see the influence of Gaskell, Charlotte and Emily Brontë and other novelists in the greater use of this literary trope. Journalists were likely to pick up literary trends before most of their readers, which could explain the later use of reported dialect speech in readers’ letters, in the 1870s, after the use of the device had become established first in fiction and poetry, and then in newspaper reporting.56 This could also explain the peak in the 1870s of the use of dialect by letter-writers and journalists using the editorial voice, showing a peak of confidence in local dialect.

Table 8.3: Usage of dialect in selected Lancashire newspapers, 1830s–‘90s (instances per 100,000 pages).

|

1830-1839 |

1840-1849 |

1850-1859 |

1860-1869 |

1880-1889 |

1890-1899 |

||

|

Reported speech, court case defendant or witness |

20 |

123 |

42 |

41 |

26 |

9 |

4 |

|

Reported speech in news/feature article |

0 |

36 |

81 |

67 |

19 |

47 |

33 |

|

Reported speech in reader’s letter |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

81 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

31 |

32 |

53 |

55 |

|

|

Writer’s own words |

0 |

2 |

22 |

1 |

65 |

16 |

25 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

65 |

19 |

33 |

|

|

64 |

72 |

24 |

30 |

20 |

35 |

25 |

|

|

64 |

39 |

20 |

1 |

32 |

0 |

84 |

Many literary tropes were shared by journalistic and more ‘literary’ writing, which is less surprising when we consider that journalists, like novelists, were in the business of telling stories. As Dallas Liddle and Matthew Rubery have demonstrated, a focus on content (for example Lancashire dialect, or particular news stories), rather than forms of publication (books or newspapers) can help us see how techniques and attitudes were passed between and within genres such as literature and journalism which are anachronistically viewed as separate spheres.57 The case of dialect reminds us that an interplay was also taking place between print and oral culture, further challenging simplistic ideas of print replacing oral traditions.58

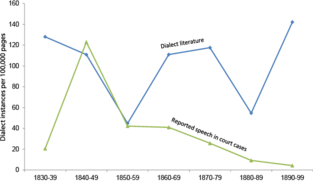

The increasingly cross-class use of dialect can be seen more clearly in Fig. 8.2 below. Working-class witnesses and defendants were marked out for their use of dialect in court cases less and less, while dialect literature, written by members of all classes, increased in popularity. Most dialect writing in newspapers was anonymous, and it has not been possible to ascertain most authors’ identities and hence their class. However, Joyce, Lucas, Russell and Salveson suggest that many nineteenth-century writers of dialect prose and poetry were middle-class, with Russell’s analysis of Yorkshire dialect writers up to 1945 finding that the class distribution was about even.59 Some were not even native speakers, but had the technical facility to convincingly reproduce dialect speech, aided by the growing volume of glossaries and other dialect literature; these writers included M. R. Lahee, an Irish woman celebrated as one of Rochdale’s finest dialect poets;60 the Middlesbrough-born journalist Joseph Richardson and the Nottingham-born surgeon-turned-vicar Dr Barber, who both published literature in the dialect of Lancashire ‘north of the sands’.61 Frederic W. Moorman, Devon-born Professor of English Language at the University of Leeds at the turn of the twentieth century, wrote and edited Yorkshire dialect poetry and prose.62

Fig. 8.2. Dialect literature and dialect in court reporting, 1830–99, selected Lancashire newspapers, per 100,000 pages. Author’s graph, CC BY 4.0.

There appear to be two separate processes at work: the rise in popularity of dialect literature from the late 1850s to the early 1870s, and a greater sensitivity to the growing numbers of working-class local newspaper readers. The peak of reported dialect speech in the 1840s could be related to the renewed popularity of dialect literature, and its subsequent decline could be caused by the growing editorial realisation that the paper’s new working-class readers might be offended by the supercilious way in which their class was portrayed through the comic use of dialect quotes. By the time of the second Reform Act (1867), newspapers were beginning to claim a working-class readership.63 As Gareth Stedman Jones has noted, ‘Changes in the use of language can often indicate important turning points in social history’.64 It may also be that, as the literature boom raised the status of dialect, so its usefulness as a class marker declined.

As dialect increased in legitimacy as a written form, it became one literary device among many, to be used in a growing range of contexts. For example, Cross Fleury’s Journal, a Preston monthly magazine, comfortably mixed Standard English, French, Latin and Lancashire dialect in a report of an 1897 royal jubilee celebration, while the Preston Argus, a weekly paper, introduced itself to readers thus:

As this is our first appearance under the new name, we take off our hat and give you kindly greeting, if only for the purpose of proving to you that we have “larn’t manners.”65

The dialect may have been in inverted commas, but it was now found in sections of these publications where previously only Standard English had appeared.

While there may have been renewed respect for written dialect, at least in some quarters, dialect speech was probably in decline. The debate among teachers around the 1862 Revised Code for teaching in schools showed that many valued dialect speech, and respected the language spoken by children at home.66 But after the 1870 Education Act, and compulsory education from 1880, there was a push for standardised English, and policies were introduced into Lancashire schools to ‘eradicate’ dialect speech.67 In 1890 the debate was revived in Rochdale, when the local inspector of schools called for dialect writer ‘Tim Bobbin’ to be studied alongside Shakespeare (in an equally dry manner); the Rochdale Observer opposed the inspector and declared in an editorial that ‘dialect is dying through schooling and the newspapers’.68

Readers seemed to like the use of dialect in local newspapers, judging from their many responses to competitions encouraging them to send contributions. Dialect writing (like many other genres published in the local press, week by week) was often republished in book form, by the same newspaper publishers. For example, Giles’s Trip to London: A Farm Labourer’s First Peep at the World, by James Spilling, first appeared in the Eastern Daily Press and Ipswich and Colchester Times. Reprinted in book form by the Eastern Daily Press, it had gone through 58 editions (239,000 copies) by 1903. For the most part, we can only guess at readers’ responses. As Maidment and Hollingworth have noted of dialect poetry, it evoked a sense of belonging and community, of inclusion.69 Conversely, it may have excluded those who did not read, speak or understand the particular dialect. Translation was sometimes necessary, if dialect was part of a sensational court case that received national coverage, as in a widely reported murderer’s confession which included the word ‘skrike’. In Lancashire newspapers the word was given without explanation, but in other parts of the country the translation ‘(scream)’ was added.70

Conclusions

Dialect in print, far from being a sub-genre of low-quality comic or sentimental folk literature, or a simple marker of working-class status — a sociolect — had a variety of uses in local newspapers, revealing the linguistic and literary sophistication of these texts. The very fact of who was represented as using it sent a simple message of social distinction; more subtly, it could be used as a rhetorical device to strengthen supposedly ‘commonsense’ arguments, and more subtly still, the untranslatable nuances of dialect words and phrases could add depth to any piece of writing. In these ways, publishers and writers in areas with a lively dialect tradition had literary advantages over less linguistically diverse areas, being able to call on an extra set of meanings.71 Comparisons with other ‘bilingual’ publishing situations, such as English-language newspapers in Wales, would be instructive.

However, some dialect speakers may have felt excluded. The orthography used to render dialect in print was one of the subtle ways in which certain readers could be excluded because of their educational level. Dialect in print was harder to read than Standard English, perhaps particularly for dialect speakers, who naturally read Standard English in a Lancashire accent, and so may have been confused by many of the phonetic spellings. A reader who does not speak in Received Pronunciation receives a clear message, ‘this text was not written for you’.72

Power relations are central to any understanding of language, and the ‘value-laden’ nature of dialect shows this clearly.73 Working-class writers increasingly had the power to represent themselves in print, in local newspapers, to be subjects rather than objects. The changing uses of dialect in local papers reveal editors deciding who is represented as ‘them’, who as ‘us’. Increasingly, working-class readers went from the former category to the latter. Some papers in some towns made more efforts in this regard than others.

Dialect in print highlights two competing discourses, of place (region or locality) and class. Local newspapers’ use of dialect to capitalise on their readers’ sense of place was inclusive, in the main, with surprisingly little reference to an ‘other’, perhaps because of their very localised markets. But they also used dialect as a strategy of exclusion, by class rather than geography, particularly at the start of the period under discussion, when readers were mainly middle-class. In contrast, working-class listeners to such a paper being read aloud may have felt like eavesdroppers, being talked about rather than included in the conversation. The use of dialect in reported speech emphasised class differences, while dialect literature played them down. Newspapers colluded in the fiction that middle-class people did not speak in dialect in formal settings, by putting Standard English words into their mouths — even though this was no more than a convention, and most of their readers knew it was a fiction. Moses Cocker was penalised by the Blackburn Mercury not because he was monolingual, but because he was not respectable. The phonetic rendering of his dialect was a punishment, an example of policing the borders of social distinction by the press. However, the middle-class institution of the local paper occasionally allowed glimpses of working-class dialect speakers using this language variety to mock and defy other institutions of authority, a sign of the complexity of dialect, and of local newspapers, which were not monolithic, mono-glossal bourgeois institutions, but poly-glossal, multi-authored texts. Over time, as more working-class newspaper readers became newspaper purchasers, dialect was used less to exclude, and more to include. The use of dialect in reported speech declined; conversely, the use of dialect in a wider range of literary contexts grew, as it became more established as a legitimate writerly device. New working-class readers influenced the language of newspapers, which were eager to cater to their tastes and sensibilities. The cross-class nature of much dialect literature made it a safe selling point to these new readers, who were thus welcomed into an expanded ‘imagined community’ of other readers for mainly commercial reasons.74

Local newspapers’ use of dialect reveals the dynamic and contested nature of local identities. In a newspaper, ‘what is arrayed before the reader is not pure information but a portrayal of the contending forces in the world.’75 These contending forces were present in the multiple local identities fought over within and between each publication, class identities amongst them. There was more than one imagined community. Many historians have noted a lessening of conflict in the pages of late nineteenth century local newspapers (see Table 8.4). Murphy believes that the ‘ideology of impartiality’ was a result of newspapers’ move from the political arena into the marketplace: ‘the new commercial papers of the late nineteenth century identified themselves with a sort of parish-pump patriotism, a supra-factional, local, public interest […]’76 Factors beyond the press may also have been involved in the reduction of class and religious conflict, such as a calmer political atmosphere after the Second and Third Reform Acts, higher real wages and shorter working hours, and more tolerance of Catholics. However, the evidence from this study of dialect suggests another commercial reason, an attempt to welcome new working-class readers into a classless conception of the locality. They downplayed conflict and ‘encouraged positive identification with the local community, its local traditions and its middle-class leadership.’77 This was certainly true when Preston’s football club nearly collapsed in 1893, the subject of the next chapter.

1 I have found no trace of a Mr Brooks connected to the Blackburn Mercury (1843–46); the paper’s last editor was Robert Wilson Smiles, brother of the author Samuel Smiles, who went on to work for the Lancashire Public Schools Association and became chief librarian of Manchester Free Library in 1858: ‘Demise of the Blackburn Mercury’, Blackburn Standard, 29 July 1846, 7 October 1846.

2 William Golden Lumley, a barrister, was Assistant Secretary to the Poor Law Commission from c. 1841 to 1847: Correspondence between Lumley and Charles Mott, The National Archives ref: MH 12/6040-43. I am grateful to Peter Park for this reference.

3 ‘Recollections of Blackburn and its Neighbourhood’, ‘by an old East Lancashire man’, Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC), 22 December 1877.

4 Blackburn Standard, 15 April 1846.

5 ‘Reporters and reporting’, February 7, 1870, p. 27.

6 James Vernon, Politics and the People: A Study in English Political Culture, c. 1815–1867 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 147.

7 Style-shifting, or code-switching, is when ‘speakers routinely draw on different varieties of English […] to communicative effect’: Joan Swann, ‘Style Shifting, Code Switching’, in English: History, Diversity and Change, ed. by David Graddol, Dick Leith, and Joan Swann (London: Routledge, 1996), pp. 301–37 (p. 301).

8 Christine Pawley, Reading on the Middle Border: The Culture of Print in Late-Nineteenth-Century Osage, Iowa (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), p. 175.

9 P. J. Waller, ‘Democracy and Dialect, Speech and Class’, in Politics and Social Change in Britain: Essays Presented to A. F. Thompson, ed. by P. J. Waller (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1987), pp. 1–33 (p. 2).

10 Dave Russell, Looking North: Northern England and the National Imagination (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), pp. 111–12.

11 A. N. Wilson, The Victorians (London: Arrow, 2003), p. 114; Augustine Birrell, ‘Sir Robert Peel’, The Collected Essays & Addresses of the Rt. Hon. Augustine Birrell, 1880–1920 (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1922), p. 331, http://archive.org/details/collectedessaysa01birr

12 www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. The search was limited to material added to the database before 16 January 2018. The twenty-three Lancashire titles available between 1830–99 comprised the Blackburn Standard, Blackburn Times, Bolton Chronicle, Bolton Evening News, Burnley Advertiser, Burnley Gazette, Burnley Express, Bury Times, Lancashire Evening Post (Preston), Lancaster Gazette, Leigh Chronicle, Liverpool Mercury, Liverpool Mail, Liverpool Daily Post, Manchester Courier, Manchester Times, Preston Chronicle, Preston Herald, Rochdale Observer, Todmorden Advertiser, Todmorden News, Warrington Guardian and Wigan Observer. Every instance of ‘skrike/skriking’ and ‘anenst’ was included, but the more common word ‘gradely’ was only searched for in the fifth year of each decade, to make the exercise more manageable. For a spreadsheet of the full results, see supplementary online material.

13 Manchester Times, 8 June 1833, p. 3

14 Bolton Chronicle, 25 February 1843, p. 2.

15 Bolton Chronicle, 16 August 1845.

16 Rochdale Observer, 9 December 1865.

17 Liverpool Mercury, 2 October 1835, p. 6.

18 Bolton Chronicle, 13 December 1845.

19 For example, the Cockney characters of Sam Weller in The Pickwick Papers or Sarah Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit. ‘English writers have seldom felt able to take the risk of depicting a hero or heroine as a dialect speaker […] Of course, if the intention was to portray a character as ignorant and comical, the use of dialect would serve very well’: William Robert O’Donnell and Loreto Todd, Variety in Contemporary English (London: Routledge, 1992), p. 133.

20 PC, 8 May 1841.

21 Patrick Joyce, Visions of the People: Industrial England and the Question of Class, 1848–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 245, 249.

22 Vernon, p. 147.

23 ‘Conservatism at Oldham: Lord Harris on the land question’, Manchester Courier, 28 September, 1885.

24 PC, June 14, 1884.

25 John Brookshire Thompson, ‘Editor’s Introduction’, in Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, ed. by John Brookshire Thompson (Cambridge: Polity, 1991), p. 19.

26 Russell, p. 278.

27 Katie Wales, Northern English: A Cultural and Social History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 128, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511487071

28 Leigh Chronicle, 11 March 1865.

29 Leigh Chronicle 30 October 1896, p. 8.

30 Fiona McPherson, ‘The Iron Lady: Margaret Thatcher’s Linguistic Legacy’, OxfordWords Blog, 2013, https://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2013/04/10/margaretthatcher/

31 Stephen Caunce, ‘British, English or What? A Northern English Perspective on Britishness as a New Millennium Starts’, Unpublished Conference Paper Delivered at “Relocating Britain” Conference, University of Central Lancashire’, 2000, n. p.

32 PC, 4 April 1868.

33 PC, 3 September 1864.

34 William Gaskell, Two Lectures on the Lancashire Dialect (London, 1854).

35 Patricia Ingham, ‘Introduction’, in North and South, by Elizabeth Gaskell, ed. by Patricia Ingham (London: Penguin, 1995).

36 PC, 24 August 1872.

37 PC, 10 February 1877.

38 Liverpool Daily Post, 15 June 1855, p. 1.

39 Preston Herald, 23 January 1875.

40 Burnley Express, 6 April 1895, p. 6.

41 Martha Vicinus, The Industrial Muse: A Study of Nineteenth Century British Working-Class Literature (London: Croom Helm, 1974); Brian Hollingworth, Songs of the People: Lancashire Dialect Poetry of the Industrial Revolution (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1977); Joyce, chap. 6; Paul Salveson, ‘Region, Class, Culture: Lancashire Dialect Literature, 1746–1935’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Salford, 1993); Russell, chap. 4.

42 Table of contents, Papers of the Manchester Literary Club, vol 19, 1893, in Sutton, Charles W, and William Credland, eds. Manchester Literary Club: Index to Publications, Catalogue of the Library and List of Members 1862–1903 (Manchester: Sherratt & Hughes, 1903), http://archive.org/details/indexpapers00mancuoft, p. 15.

43 Andrew Hobbs and Claire Januszewski, ‘How Local Newspapers Came to Dominate Victorian Poetry Publishing’, Victorian Poetry, 52 (2014), p. 83, https://doi.org/10.1353/vp.2014.0008

44 Thanks to Professor Brian Hollingworth for these points.

45 Graham Shorrocks, ‘Non-Standard Dialect Literature and Popular Culture’, in Speech Past and Present: Studies in English Dialectology in Memory of Ossi Ihalainen, ed. by Juhani Klemola, Merja Kyto, and Matt Rissanen (Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1996), pp. 390–91.

46 PC, April 16, 1864.

We must manage, old girl, to pull through,

If we can hold out a bit longer

Though it’s been a terrible do

We’ve had with starvation and hunger.

By gum! When I look in your face

And see you so haggard and thin,

My heart well nigh bursts, I confess

And the water will rise to my eyes.

47 Salveson, p. 133.

48 PC, 29 June 1878.

49 Salveson, PhD, summary [n.p.].

50 Peter J. Lucas, ‘The First Furness Newspapers: The History of the Furness Press from 1846 to c.1880’ (unpublished M.Litt, University of Lancaster, 1971), p. 16; Peter J. Lucas, ‘The Dialect Boom in Victorian Furness’, Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, 5 (2005), 199–216 (p. 205).

51 George Hull, The Poets and Poetry of Blackburn (Blackburn: G. & J. Toulmin, 1902).

52 For example, ‘Tales i’ the Nook by Edwin Waugh: It’s Noan o Mine!’, 16 November 1878.

53 Blackburn Standard, 24 August, 10 August 1895.

54 Hollingworth, Songs of the People, p. 2. Hollingworth dates the boom to 1856–70.

55 William Donaldson, Popular Literature in Victorian Scotland: Language, Fiction, and the Press (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1986), pp. 53–54.

56 In Manchester many journalists worked through the Manchester Literary Club to compile a Glossary of Lancashire Dialect: Margaret Beetham, ‘Healthy Reading’, in City, Class and Culture: Studies of Social Policy and Cultural Production in Victorian Manchester, ed. by Alan J. Kidd and Kenneth W Roberts (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985), pp. 173–74.

57 Dallas Liddle, The Dynamics of Genre: Journalism and the Practice of Literature in Mid-Victorian Britain (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009); Matthew Rubery, The Novelty of Newspapers: Victorian Fiction After the Invention of the News (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

58 For a discussion of these themes exemplified in another publishing genre, the local magazine, see Margaret Beetham, ‘Ben Brierley’s Journal’, Manchester Region History Review, 17 (2006), 73–83, particularly pp. 81–82.

59 Salveson, p. 4; Joyce, p. 258; Lucas, ‘Dialect Boom’, p. 205; Russell, pp. 120–21.

60 Taryn Hakala, ‘M. R. Lahee and the Lancashire Lads: Gender and Class in Victorian Lancashire Dialect Writing’, Philological Quarterly, 92 (2013), 271–88.

61 Lucas, M.Litt, p. 16; Lucas, ‘Dialect Boom’, p. 205.

62 William Marshall, ‘An Eisteddfod for Yorkshire? Professor Moorman and the Uses of Dialect’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 83 (2011), 199–217, https://doi.org/10.1179/008442711X13033963454633

63 Lucy Brown, Victorian News and Newspapers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), pp. 73–74.

64 Gareth Stedman Jones, Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship between Classes in Victorian Society (Penguin Books, 1984), preface, p. v.

65 ‘Sparks from the Anvil’, Cross Fleury’s Journal, July 1897, 10; Preston Argus, 17 September 1897, p. 1.

66 Brian Hollingworth, ‘Education and the Vernacular’, in Dialect and Education: Some European Perspectives, ed. by Jenny Cheshire (Multilingual Matters, 1989), pp. 293–302.

67 Brian Hollingworth, ‘Dialect in Schools —an Historical Note’, Durham and Newcastle Research Review, 39 (1977), 15–20 (p. 16).

68 Rochdale Observer, 22 March 1890, cited in Hollingworth, ‘Dialect in Schools’, p. 19. The newspaper’s view is consistent with James Vernon’s argument that the local press harmed local oral cultures: Vernon, p. 147.

69 Brian Hollingworth, ‘From Voice to Print: Lancashire Dialect Verse, 1800–70’, Philological Quarterly, 92 (2013), 289–308 (p. 297).

70 PC, 29 November 1890.

71 Hollingworth, ‘From Voice to Print’, p. 294.

72 In the same way, twenty-first-century London newspapers’ attempts to render the northern accent phonetically (for example, spelling a well-known swear-word as ‘fook’) automatically exclude readers with that accent. Oral historians in Scotland found that transcripts of interviews which were written phonetically were almost incomprehensible to the interviewees: Stephen Caunce, Oral History and the Local Historian (London: Longman, 1994); Graham Shorrocks, ‘A Phonemic and Phonetic Key to the Orthography of the Lancashire Dialect Writer, Teddy Ashton’, Journal of the Lancashire Dialect Society, 27 (1978), 45–59 (p. 59); Wales, p. 138.

73 Nikolas Coupland, Dialect in Use: Sociolinguistic Variation in Cardiff English (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1988), p. 95.

74 James Curran, ‘The Press as an Agency of Social Control’, in Newspaper History from the Seventeenth Century to the Present Day, ed. by David George Boyce, James Curran, and Pauline Wingate (London: Constable, 1978), pp. 51–75 (p. 71); Russell, p. 127; Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006).

75 James Carey, Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society (London: Routledge, 1989), p. 20, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203928912

76 David Murphy, The Silent Watchdog: The Press in Local Politics (London: Constable, 1976), p. 28.

77 Curran, p. 71.