9. Win-win: The Local Press and Association Football

© 2018 Andrew Hobbs, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0152.09

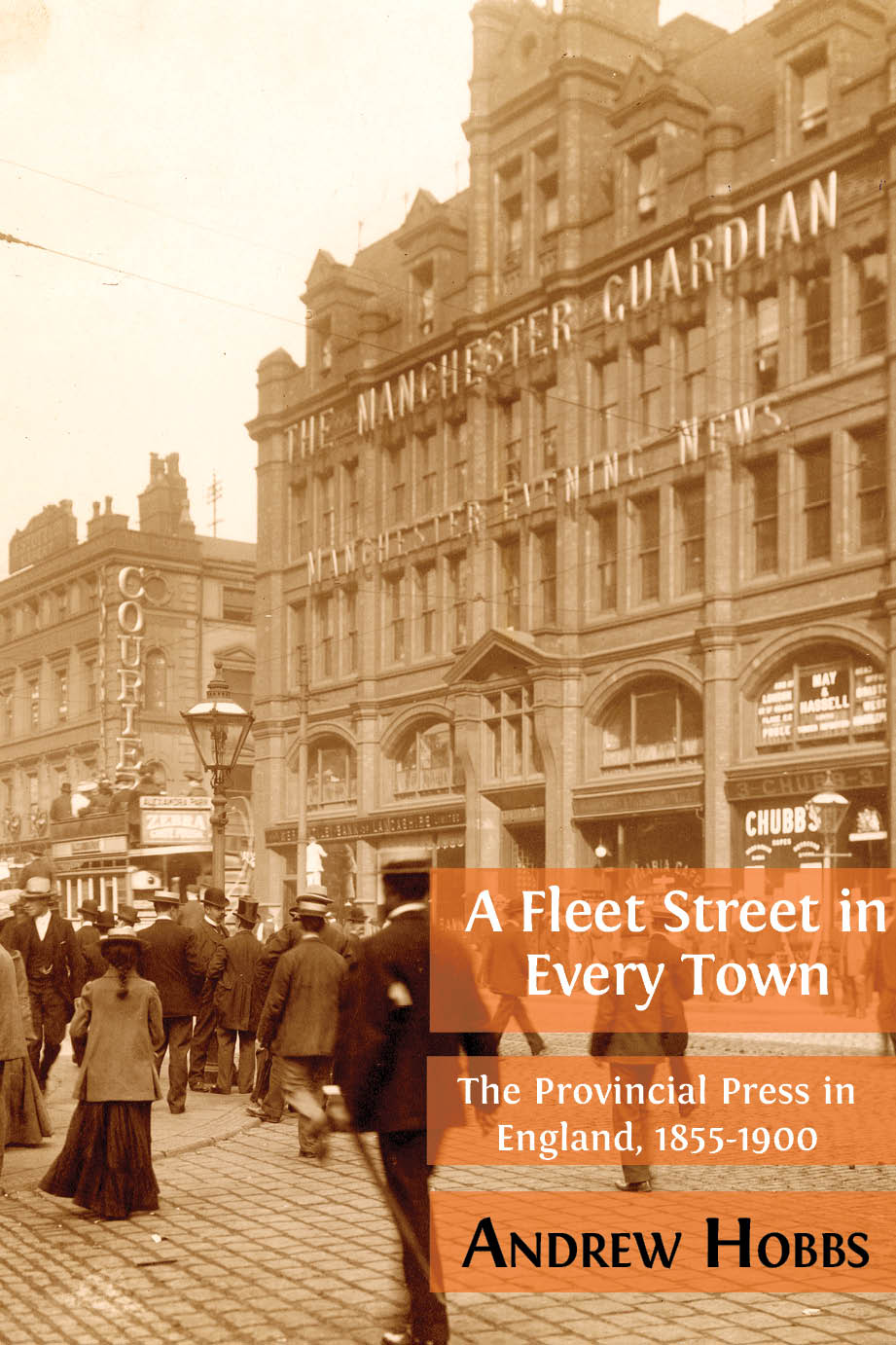

Football made the local evening newspaper, and the local evening newspaper made football. From the 1880s onwards, the huge popularity of organised professional association football fed, and fed off, the local press. Both were part of national structures, both relied on local patriotism for their success. It was a win-win situation. Sports coverage was a significant part of the changes in British journalism that coalesced in the 1880s as the ‘New Journalism’, bringing in new readers and purchasers, particularly among the working classes. The coverage of professional football in Preston’s newspapers represented a conscious broadening of appeal, in the same way that most Lancashire newspapers had changed their use of dialect in an attempt to attract working-class readers (Chapter 8). The symbiotic relationship between football and the local press, and the techniques used by the press to incorporate the game into its conventions of local patriotism, are illustrated by coverage of a high point and a low point in the fortunes of Preston North End Football Club. In 1889 PNE reached the pinnacle of their career, becoming champions of the new Football League in its first season without losing a match, and winning the FA Cup without conceding a goal. But four years later, in the summer of 1893, the club nearly collapsed under heavy debts, was suspended by the sport’s governing body, the Football Association, and only just scraped together enough money to relaunch as a limited company.

Sports history has produced some perceptive writing on the nature of local — and regional — identities. It seems that sport, and football in particular, is the quintessential creator and sustainer of local identity. Like the local press, it has the capacity to incorporate almost any other aspect of local identity, thereby combining and magnifying elements into a more powerful whole — but with the added ingredient of emotional involvement.1 Jeff Hill’s classic study of the ritual of the Cup Final demonstrates powerfully the number of elements at play, magnified and mythologised by the local press, which ‘often stepped into the realm of myth-making. By offering comment and opinion on the events, or simply by selecting certain aspects for attention, newspaper editors and reporters played upon notions of identity which drew on and at the same time reinforced a sense of local distinctiveness.’2 As this chapter demonstrates, Preston newspapers, like many others, incorporated into their sports coverage many of the techniques discussed previously, such as local history, boosterism and ‘othering’, in an appeal to local patriotism.

Working-class interest in football developed in Lancashire before many other parts of the country, with association football (as distinct from rugby football) reaching Preston from East Lancashire, where it had been popular since the late 1870s.3 Preston North End (PNE), originally a cricket club, switched from rugby to the ‘dribbling game’ fully in 1882.4 They quickly adapted to the new code, and began to import Scottish players and the Scottish passing style of play. While other clubs were still concocting ad hoc teams for each fixture, PNE concentrated on building a stable, consistent team, better able to play in an ‘organised scientific style’. From August 1885 to April 1886 the club had an undefeated run, although success in the Lancashire and FA cup competitions eluded them. By 1886 the club had ‘assumed the prerogative of using the ancient town crest’, thereby claiming to represent the whole of Preston.5 In 1888 they reached the finals of the FA Cup and the Lancashire Cup, but refused to compete for the latter trophy against Accrington, in Blackburn, because of the hostility of Blackburn supporters (demonstrating the fierce inter-town rivalries expressed through football).6

Football and the Local Press

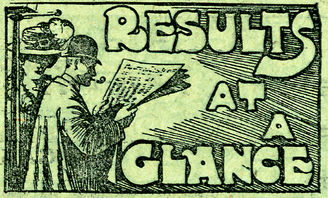

The rise of association football assisted, and was assisted by, the rise of the local press. Contemporary reading surveys found that many men, particularly among the working classes, read sporting papers and halfpenny local evening papers, featuring a great deal of sport (see Chapter 6). These publications developed around the same time as professional football, and Mason is one of many sports historians to have identified an ‘important symbiotic relationship between the expansion of the game, both amateur and professional, and both the growth of a specialised press and the spread of football coverage in the general newspapers.’7 The local and regional sporting press grew enormously in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, with evening papers (and some weeklies) adding special late football editions to their Saturday papers, including the Blackburn Times (1883), owned by the Toulmins, publishers of the Preston Guardian and Lancashire Evening Post..8 These football and sports specials, such as Sheffield’s Green ‘Un (Fig. 9.1 below) were ‘arguably the most important consumer product produced for supporters’.9 Mason claims that ‘sports coverage in local papers helped shape local identities and boost partisanship.’10 This is certainly what the local press set out to do, but whether they were successful is harder to prove.

Fig. 9.1. A speedy results service was as important as local patriotism for newspaper readers, as seen in this illustrated column header in the Football and Sports Special of the Yorkshire Telegraph and Star, known colloquially as The Green ‘Un because of the distinctive colour of its newsprint, 31 October 1908 (British Library NEWS979). © The British Library Board, all rights reserved.

Local evening papers, and Saturday sports specials in particular, had two distinct selling points: first, their local flavour, and, second, the speed with which they delivered results, reports and comment (Fig. 9.1), on football but also on non-local sports, notably horse racing. Lee claims that ‘London evening papers sold a quarter to a third more copies during the racing season’.11 Evidence that the local and localised content was a large part of the appeal of sports news comes, paradoxically, from the ‘national’ press, in which sports reporting was the most localised content. The Daily Mail, for example, utilised the ability to publish variant regional editions, thanks to its publishing operation in Manchester, in which sports content was the most differentiated type of content. Content analysis of two Monday editions of the Mail in 1900, after the launch of its Northern edition, and in 1908, found that the sports news accounted for fifty-five of the eighty-seven column inches that were different in the two sampled issues, and the same First Division football matches were reported differently in each edition, with reports in the northern edition written from the perspective of northern fans, and those in the London edition written from the perspective of southern fans.12 The local and regional nature of interest in professional football was well understood and catered for.

Sports coverage grew rapidly in Preston’s papers in the last two decades of the century, but there was fierce competition and careful differentiation between titles within the same stable. A comparison of the main Preston papers shows that sports coverage was minimal in 1880, with the one weekly and two bi-weekly papers devoting between one and three columns to it per week, the bi-weekly Herald and Guardian giving slightly more space than the weekly Chronicle (Table 9.1 below). James Catton, an apprentice reporter on the Herald at the time, later wrote of PNE captain Harry Cartmel, ‘how desperately he used to try and secure the support of the local press, which just tolerated football in an off-hand kind of way at that date.’13 By 1890, sport (mainly football) was now a significant part of the contents of the Herald, with more than fourteen columns per week devoted to it, or 11.1 per cent of its total space, while twenty-five columns of sport in the new Lancashire Evening Post accounted for more than twenty per cent of its space. Sometimes there was even more, as in the Saturday 2 September 1893 Evening Post, in which sport accounted for more than two-thirds of editorial content. The Herald’s focus was narrower, concentrating more on Preston and Lancashire sport, while the Evening Post featured more regional and national sport. Generally, football coverage was more focused on Preston than was cycling or cricket coverage. By 1890 the Guardian had decreased its coverage, probably to avoid competition with its sister evening paper, while the ailing Chronicle, now in new hands, had only slightly more sport than under Hewitson’s ownership. By 1900 the Evening Post was clearly dominant in its sports coverage, devoting a third of its space to it, more than seventeen columns. The Herald had ceded to this dominance, reducing sport from around fourteen to about four columns per week, or less than three per cent of its space.

Table 9.1. Sports coverage, selected Preston newspapers, 1880–1900 (number of columns published per week).14

|

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

|

3.4 |

5 |

||

|

0.8 |

0.6 |

||

|

0.3 |

0.3 |

0 |

|

|

0.7 |

4.6 |

1.5 |

|

|

8.8 |

25.5 |

||

|

0.2 |

0.6 |

||

|

1.6 |

0.3 |

0 |

|

|

1 |

5.5 |

0.3 |

|

|

Total sport |

|||

|

25.1 |

57.3 |

||

|

1 |

1.5 |

||

|

2.9 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

|

|

1.7 |

14.7 |

4.3 |

In 1888 the four-page Evening Post concentrated most of its football coverage in its two Saturday late editions, the 7pm ‘football edition’ and the 8pm ‘extra special edition’.15 All Saturday editions carried previews of the day’s matches around Lancashire. Another column, ‘We Hear and See’, comprised snippets of news, gossip and comment, plus excerpts from other papers, metropolitan and provincial, about Lancashire clubs and football in general. The two late editions also carried match reports of league and cup matches and the final scores of other matches, professional and amateur. Monday’s late editions featured a round-up of significant Lancashire games and how they affected the league and cup standings, plus commentary and descriptions of the main matches. While the evening paper could report Saturday’s matches within hours of the final whistle, with additional comment two days later, the bi-weekly Herald had to wait until the following Wednesday. Both papers professed to circulate in and report on the whole of North Lancashire, home to some of the most successful clubs of the era, but both gave precedence to Preston North End, in order of priority and amount of editorial space; this suggests that Preston was the core of their sales area. However, the Herald often hedged its bets when reporting a Preston game against another North Lancashire side, for example in the 24 October 1888 issue, when Preston played Accrington in the League. One paragraph of notes and analysis of the game from Preston’s perspective is followed by a paragraph beginning, ‘The Accrington view of the game was as follows […]’16 This technique is still used in the northern and southern editions of twenty-first-century national newspapers, but one version replaces the other, rather than sitting together in the same edition, as in the Herald. Did this accentuate local patriotism, whilst allowing each team’s fans to learn how others saw their club — or was it merely confusing? The Preston Guardian Wednesday edition carried three or four columns of sports news in 1888, but most of this material was identical to that published in its sister paper, the Evening Post, and so has been excluded from this account.

In contrast, the Preston Chronicle covered cricket, bowls and rifle volunteer shooting matches, but under Hewitson’s editorship, no football. His diary explains why. He saw his first football match in 1884: ‘I don’t care for the game and I believe it would not by any means be so very popular as it is if it were not for the betting & gambling mixed up with it.’17 When a North End player broke a leg a month later, Hewitson commented, ‘I wish lots would do same. I’m disgusted with it & the gambling associated with it.’18 What annoyed him most were the large crowds outside rival newspaper offices in Fishergate during matches, gathered to read, hear and discuss telegraphed reports of the games. At the start of the 1886 season the only mention of football in the Chronicle was a paragraph in the ‘Local Chit-Chat’ column calling on the Watch Committee or police authorities to ‘stop the insane crowding of Fishergate, especially on Saturday evenings, by persons waiting for football returns’ as it affected trade.19 The Chronicle was the only paper to publish letters critical of football, such as one headed ‘Is footballing a game, or what?’ from ‘Old Prestonian’ in 1887.’20 Hewitson’s diary entry for 5 March 1887 reads:

Preston North End footballers beaten to day by West Bromwichers at Nottingham. A big, idle, godless, hands-in-breeches-pockets, smirking, spitting crowd in Fishergate waited a considerable time for the result […] Could like to see a hose pipe opened or turned full on them.

Besides snobbery and a personal dislike of the game, no doubt there was envy at the popularity of football coverage in the Herald and the Evening Post. In contrast, one of the purchasers of the Chronicle when Hewitson sold up in 1890 was Francis Coupe, who went on to become one of twelve directors when PNE became a limited company in 1893.21 Strangely, Coupe’s name disappeared from the imprint of the paper in the same week that he was elected to the committee overseeing the conversion of the football club into a company. The influence of the Chronicle’s new owners was apparent from their first issue, when football coverage increased from nothing to almost two columns.22 By 1893, the Chronicle typically published a single column of sports news, either cricket or football depending on the season, comprising very brief match reports, league tables and a county round-up. Hewitson’s decision to ignore football shows the influence of an individual publisher, and the business costs of missing a significant journalistic trend.

The crowds outside newspaper offices were a symbol of the mutual benefits derived by football clubs and local papers. A description of the crowd during an FA Cup tie at Aston Villa in 1888 shows how the supporters shared the limelight with the players in football reportage, how newspapers revelled in their new role, and how hard it is to imagine professional football becoming so successful without the infrastructure provided by the local press.

By half-past two there would be at least a couple of hundred people in front of the office of the Lancashire Evening Post, and half an hour later there was a […] busy bustling crowd which reminded one of the exciting days of electoral conflict. The excitement became intense, and groups of people were discussing the probabilities with great animation […] By four o’clock the gathering had assumed very large proportions, the crowd extending almost to the Town Hall in one direction and to Guild Hall street in the other. The notes on the progress of the game, periodically posted, were read with the most absorbing interest […] round after round of cheering went up at the splendid win. The news was speedily carried to all parts of the district […] The final result was first announced from the door of the Evening Post Offices, by Mr John Toulmin […] Coloured lights were ignited on the balcony of the Conservative Club, in Church-street, and fireworks were discharged in other parts of the town.23

While pubs, sports outfitters and tobacconists also posted telegraphic football news, many supporters preferred to stand outside a newspaper office. The reference to Preston’s lively electoral history gives a flavour of the heightened atmosphere, and the fact that a proprietor of the paper gave the final score shows the importance attached to this duty. However, the carrying of the news ‘to all parts of the district’, the Conservative working men’s club lights and the fireworks, show that football fever was more than a press-inspired fad.

That said, the local press was ‘absolutely indispensable’ to the organisation and popularity of the game, especially the local amateur game.24 The ‘Brief Results’ column of the Evening Post in 1888, for example, listed the scores of some fifty amateur Preston teams, from information supplied by ‘secretaries of clubs desirous of making the exploits of their organisations known’.25 Newspapers met the demand for facts and figures through their ‘Notices to Correspondents’ sections and ‘offered prizes, management, commitment, even judges and referees. Newspapers helped to form those sporting sub-cultures that grew up around particular sports and particular competitions.’26

In football as in other spheres, Preston’s most potent ‘other’ was Blackburn. ‘There are signs that the Blackburn crowd is slowly learning to appreciate really good football’, the Preston Herald condescended in 1889.27 In 1893, when Blackburn defeated Preston at Deepdale, ‘The enemy came over from Blackburn, and literally took possession of the Proud town on Saturday. Fishergate was captured, and Prestonians were generally walked over […]’28 A gentler ‘othering’ is seen in the mockery of a traumatised Wolverhampton Wanderers fan at the end of the Cup Final, whose Midlands accent is rendered phonetically, as he protests at the sight of the cup denied to his team: ‘Toike it away! Toike it away! Ow yes, send it to Preston!’29 We can see the many techniques for producing locality in the coverage of two contrasting seasons in the early career of Preston North End FC.

Winning the Double, 1888–89

The underlying tone of this season’s coverage was that Preston were the best team in the country and deserved to win the League and the Cup. Preston played well, and it was hard to find an article about the team that neglected to praise their current or past performance, so that no other section of each newspaper published the name of the town so frequently, or so positively.30 In the Herald, localised pseudonymous bylines added to the effect, including ‘Red Rose’ (the emblem of Lancashire) and ‘North Ender’ in 1890, and a column, ‘Notes by “Prestonian”’ by 1893. If the team lost a friendly match (which did not affect their standings in the League or Cup), or played poorly, the papers always offered a defence: a defeat in Glasgow was excused by a tiring journey, and after a lacklustre performance at Christmas, ‘no one can justly blame a team who can win three League matches in what may be called a week, besides travelling the best part of two nights’.31 Statistics were used to show that a weak game was merely an aberration, as when North End drew with Blackburn Rovers in January 1889 and the Herald reminded readers that ‘the Prestonians are […] the winner of the thirteen out of the last sixteen matches played between the clubs’, above a table listing all Preston-Blackburn results since February 1884.32 Repetition, which came naturally to serial publications, was also apparent in the league tables published every week, always with Preston at the head. The serial nature of League and Cup football can only have added power to sport’s ability to promote local identities.33

Although North End had been playing association football for less than a decade, the press, the club and its supporters already had a strong sense of history. At the start of the season, in September 1888, many fans and commentators believed that the club, widely accepted as England’s top team, had already seen its best years. Reporting carried a ‘golden-age’ undertone, which gradually disappeared as the team won match after match. But the historical perspective remained. In January the Herald reminded readers of North End’s ‘brilliant record’ and both papers seized on a collection of match statistics given at the club’s annual general meeting in early February, including forty-four consecutive wins in the previous season, the Post proclaiming that ’no other club in the annals of football has ever come near achieving such a magnificent performance.’34 The Post repeated the figures in its Saturday edition for good measure.35 Statistics were used in the same way in both papers’ preview coverage of the semi-finals and final, while Preston’s record of no appeals for the replay of any match they had lost, was invoked in coverage of West Bromwich’s appeal after a pitch invasion during the semi-final.36

‘Association football thrived on the pitting of one local identity against another local identity in a national framework,’ according to Jeffrey Hill.37 This suited the local press perfectly, which was structured, as we have seen, as a national network of local ‘nodes’. Alexander Jackson has highlighted how local sports commentators ensured ‘that the local was linked to regional and national competitions and topics’, never more so than when this national network of writers entered into debates with each other, reproducing and responding to press comment from elsewhere. Simultaneously, this technique promoted local and national identities.38 Praise from outsiders carried extra prestige, and amplified local achievements already known to supporters, as when the Herald quoted a ‘Scotch paper’ at the end of the season as saying that ‘Preston’s play was simply perfection’.39 Criticism in other papers was often answered point by point.40 In February, when North End became the first champions of the new Football League, completing all their fixtures without defeat, the Herald and LEP both devoted half a column to press extracts praising PNE, from the Birmingham Daily Gazette, Birmingham Daily Times and Birmingham Daily Post, the Wolverhampton Evening Express & Star, the national football paper Athletic News and London’s Daily News.41 The LEP’s subsequent remarks on this laudatory ‘criticism’ reveal the circuit of press comment, pub conversation and official club discussion in which local newspapers created, supported and magnified a local footballing public sphere, and connected it to a national one:42

this criticism was taken into a certain bar-parlour on Tuesday last, and read aloud; […] subsequently a great authority who lately complained about the croakings of a section of the local press held this up as a sample of how he wished the team to be treated; […] if this is the kind of matter the North End want reeling off every week, the general opinion is they desire to have their powers and abilities over-estimated.43

One aspect of local identity formation was problematic for North End, and for the local papers that supported the team: the fact that few of the players were local (only three out of eleven in the 1888/89 season).44 A Birmingham club, Mitchell’s St George’s, the LEP noted, were proud that all the team were born within six miles of the brewery that sponsored them, and a comment on Wolverhampton Wanderers — ‘they all hail from one town, I believe’ — by FA president Major Marindin, in his Cup Final speech, was probably a dig at Preston’s imported team.45 However, North End’s pragmatic approach to the business of football was applauded by the Evening Post, who commented that ‘nobody desires to see more Scotchmen introduced and yet the local talent is not of a sufficiently high order.’46 Winning came first. Nonetheless, the Preston newspapers made the best of what they had, with the Herald emphasising the local origins of the three Preston-born players, such as left full-back Robert Holmes, ‘a Preston lad, born and bred’. In the same Cup Final preview supplement, the Herald stressed the local links of the club’s committee, led by William Sudell, the chairman, whose ancestors included a seventeenth-century Guild Mayor, the very epitome of Preston-ness.47 After the final, the Evening Post described ‘the best football team in the world’ as ‘Proud Prestonians’, bestowing honorary citizenship on the predominantly Scottish players.48

Wider identities beyond the local were also emphasised in the coverage. The LEP’s preview of the semi-final games appealed to Lancastrian identity, noting how well the county’s teams had done in the cup in recent years.49 In the same paper’s preview of the final a headline, ‘Lancashire champions’, introduced an article explaining that North End ‘seek to regain for Lancashire the possession of the “blue riband” of the Association code.’ A potted history of the competition told how ‘the North has advanced by leaps and bounds while the Metropolitan district has remained to all intents and purposes stationary[…]’50 Earlier in the season, regional identity was combined with class consciousness in a comment on North End’s victory over the leading amateur side, ex-public schoolboys the Corinthians. North-south rivalry, overlain with the class-inflected conflict between amateurism and professionalism, and pride in the fact that football was then largely a game of the North and the Midlands, is encapsulated in a remark about the Corinthians tour, said to have made a £1000 profit. ‘Of this, about £400 has been paid to “Pa” Jackson and his boys; and information as to how they have disposed of it would be gladly received by Northerners.’51 The implicit reference to North End’s previous victories in the battles over payment of players would be apparent to many readers.52

The local press techniques for creating attractive, profitable coverage of local football teams outlined above are all adaptations of established methods. But the most distinctive aspect of football coverage — the treatment of football consumers as subjects of reportage in their own right — has few antecedents, unless we look to reporting of rowdy local elections in the era before the secret ballot. This motif may have been established in the early years of association football, when the size of crowds for this new sport was newsworthy;53 it may have been an acknowledgement that, in a commercial business, the number of paying customers was crucial; perhaps, where few players were native, the local nature of the supporters could be fixed on;54 perhaps the sayings and doings of the fans were so colourful that they deserved coverage;55 or it may have been a controlled way of allowing predominantly working-class men access to the columns of a middle-class medium, a public sphere by proxy.56 Northern crowds in this period had a reputation for partisanship, and it would be interesting to compare the treatment of southern football supporters by their local papers with that of northern papers such as Preston’s.57

Whatever the reason, the crowd was written into professional football reportage at every opportunity. Large crowds (‘gates’) were a source of pride, as when Preston’s attendance of 6,000 was second only to Everton’s 10,000, or linked to almost any evaluation of North End’s performance, good or bad — ‘not only the team, but every Prestonian who takes an interest in the club, will be justly proud’ or ‘the spectators were evidently tired of the exhibition being made by [Preston], and repeatedly shouted at them to “play up” […]’58 Quips were reported, such as one about the recent departure of star defender Nick Ross to Everton: ‘the question was asked, “Where has North End’s defence gone to?” and the reply came readily, “Everton”.’59 The manner in which supporters celebrated was described, for example after Preston completed their last League fixture, before their Cup run:

the pride of their supporters has been raised considerably by their newly gained honour, and last Saturday night it required a considerable number of refreshers to quench the enthusiasm of some of the players and their admirers […] there is yet hope for them bringing that “blessed pot” to the banks of the Ribble.60

The crowd was also part of the match reports and analyses, for example in a report of an away match against Blackburn:

when play started it was quickly evident that there was a strong contingent of Prestonians present, for there was a huge cheer when Graham neatly grassed Jack Southworth […] The failure of Thomson to lead through was received with a groan. A loud cheer at the end of 23 minutes announced that Thomson had scored for the visitors.61

All of the other techniques described above could be given extra local value when voiced and amplified by supporters, such as the appeal to North End’s proud history when a victory over West Bromwich Albion ‘brought back to the memories of thousands the grand battle fought by the North End when making their name, and after the match the exploits of the men in their famous games were recounted with gusto.’62

Fan culture was supported and reported in other ways. The Evening Post published a 180-word review of the PNE fixture card in October 1888, noting that ‘Mr J Miller, lithographer, Preston, has surpassed all his previous efforts on behalf of the club. The style is less pretentious than in past years, but is much neater and more artistic.’63 Adverts next to or within the sports columns promoted ‘football houses’, pubs devoted to the game, including the Lamb, on Church Street, run by North End goalkeeper Jim Trainer, whose name appeared prominently in the advert.

The reporting of northern teams playing in London FA Cup Finals followed a formula in the early twentieth century, according to Hill: the spectators’ journey to London, enjoyment of the match in the stadium and at home, and the welcoming home of the team.64 In 1889 the Preston Herald and the Lancashire Evening Post followed only part of this formula, with heavy preview coverage, barely a mention of travelling fans, fairly ‘straight’ reporting of the match itself, but detailed coverage of the victorious homecoming. The Herald’s four-and-a-half columns of match-day preview coverage was twice the length of the Post’s, perhaps because it was unable to publish a match report that evening.65 But both were similar in content: an engraving of the FA Cup, a history of northern club appearances in the competition, a history of PNE, recent statistics, including favourable comparisons with opponents Wolves, and biographies of players (and of club officials, both with portraits, in the Herald). The Post’s preview merged into its reporting of the day itself, with a piece headed ‘Reception of the News at Preston’ describing the crowd outside its office on Fishergate.66 A week later the Post had a short item on the experiences of supporters in London, of Lancastrians bumping into ‘brother Northerners’ and out-cheering the ‘Cockneys’ at the Oval.67

The team’s return to Preston followed the ritual already established for these occasions. Beneath a headline, ‘Return of the North End team. Brilliant ovation from twenty-seven thousand people’, the Herald reported that the Public Hall ‘was packed as it has never been packed before by an audience representative of all classes of the community’, emphasising the unifying nature of the occasion. The platform party included the town’s great and good, with councillors and aldermen, doctors, solicitors and businessmen. A message was read from the mayor (absent through illness), linking the success of the ‘Invincibles’ to the prestige of the town and to imperial themes: ‘Outdoor sports have been important factors in forming and maintaining the manly robust, invincible character of the British race, and it is most gratifying to know that one’s town can take the foremost place in them.’ In the absence of the town’s MPs and other political leaders (away in London, steering a Bill through Parliament), solicitor T. M. Shuttleworth, Esq, took the chair. He declared the occasion ‘unique in the history of the good old town — (hear, hear)’ and admitted that he

was not an habitué of the football field, but he was one of those who had followed with keen interest every move of the celebrated North Enders — (hear, hear and cheers) — and nobody rejoiced more than he did on Saturday, when he elbowed his way through the crowd to look at the window of the Herald-office, and saw to his delight the result […] He asked them to give the North End team a right royal Lancashire welcome, for they were the finest football team in the world.68

As with any speeches on such an occasion, the oratory aimed to crystallise and celebrate North End’s achievement, and link it to civic and wider themes.69 The next speaker, Alderman Walmsley, described himself as ‘one of the spectators of the matches at Deepdale’. The following speaker also linked North End’s qualities to imperial triumphs, and evoked inter-town rivalry when he ‘ventured to express a hope that the club would be able to outrival even the achievements of the Blackburn Rovers in the Cup competition’ (Blackburn had won it three times). The coverage of the Evening Post and even the usually disdainful Chronicle was similar to the Herald’s, with the Post measuring the crowds favourably against Preston’s highest benchmark, the audience for the huge textile trades procession of the Guild civic festival.70 The press reported these speeches and resolutions, confirming the audience’s experience and informing those not present. By committing the occasion to print, the papers lent it status and permanence.

All this must have come as a surprise to readers of the Chronicle. Hewitson’s paper had studiously ignored North End’s greatest season, not even giving final scores, nor mentioning their League champion status, until the Saturday following the cup final. Then, a news report, headed ‘The Champion Exponents of Association Football’ grudgingly admitted that, ‘In the eyes of the Press, local and otherwise, they constitute the finest Association all-round football team that has ever graced the Oval.’ The Chronicle followed the same model of reportage as the other papers for the homecoming, describing the same events in the same way (indeed the account may have been taken from the other papers). While Hill’s general point is accepted, that the local press used such occasions to create and sustain myths, it is hard to imagine any other way of describing the home-coming.71 Even the cynical Chronicle had no other vocabulary, in its news reporting at least.

Hewitson’s commentary was a different matter. On the same page as the news report, in his ‘Local Chit-Chat’ column, he found

the massing of so many thousands of Preston people in the streets, &c […] to see eleven vanquishers in the domain of ball-kicking […] quite inexplicable, and absurd on account of its excess […] The town has a right to feel proud of its football champions; but the town need not go silly […]

North End Close to Collapse, 1893

The coverage was very different when crisis hit the club four years later. By 1893, Preston had won the league again, been runners-up three times and reached the FA Cup semi-finals once. Between late July and early September of that year, an alarming story unfolded, of debt, FA suspension, a plan to save the club by converting it into a limited company, the suspense of a slow take-up of shares, and — finally — resolution, after the bare minimum of shares had been sold, debts were paid and the club reinstated by the FA. The Herald, Evening Post and Chronicle (the latter now under new ownership, and featuring more sport, particularly football) all reported the story in a similar way, demonstrating how the presence of a successful football club was seen as essential both for the prestige of the town and for the commercial well-being of its press.72

Optimism was the dominant tone throughout, beginning with stories in the Herald and the Chronicle in advance of the much-delayed annual general meeting in late July, when the club’s financial problems were exposed.73 Optimism continued throughout the summer, whether it was warranted or not.74 The boosterism took on almost desperate tones in mid-August, after Preston’s suspension from the FA (for an unpaid debt to Everton FC), but ‘the new committee […] may be relied upon to set matters right,’ predicted the Chronicle. Against all the evidence, it added that ‘the shares in the new company […] are being quickly taken up, and there is every promise of a prosperous future for North End’, a formula repeated the following week almost word for word.75 As time ran out for the share issue in late August, day after day the Post reported that, whilst yesterday’s sales had been disappointing, today’s were picking up.76 The Chronicle’s confidence was confirmed by support from the spirit world. A séance at the Public Hall included a question to the medium ‘as to whether North End would head the League during the coming season. The lady had no hesitation about her answer. It was a decided affirmative […].’ The medium’s husband, Professor Baldwin, confirmed this evidence by offering to make ‘a reasonable wager’.77

The corollary of such optimism was a willingness to play down the bad news. The Post was the most even-handed, for example reporting the AGM without comment but nonetheless describing irregularities in the accounts, the disquiet of some members, and the defensiveness of the chairman, William Sudell, who had run the club successfully for more than a decade as a benevolent dictator. The Herald gave a fuller account, diluting the bad news slightly, while the Chronicle (now co-owned by a future club director) omitted those parts reflecting poorly on Sudell. When Preston were suspended by the FA, the Post devoted only four lines to it, the Herald and Chronicle two. The language was generally defensive. The Post claimed there were ‘no grounds for alarm’ over whether the players would sign with Preston again for the coming season, and ‘no fear’ that one player, Cowan, wanted to leave; words and phrases such as ‘satisfaction’, ‘satisfactory’ and ‘no fear of difficulty’ jarred with the grim news they accompanied.78

Readers were exhorted to unite behind the new regime and to buy shares. ‘Whatever little difference there may have been should now be forgotten,’ the Chronicle pleaded. ‘All well wishers of the winter pastime will best consult the interests of the club by forwarding their deposits at once’, the Post urged.79 These exhortations were made chiefly on two grounds: an appeal to civic pride, and to the club’s proud history and reputation. Unlike four years previously, football was now considered a fit subject for a leading article in the Post, which urged members to unite in promoting ‘the interests of the great club, the fortunes of which, in a way, may raise or lower the reputation of the town.’ The Herald urged ‘the lovers of football in Preston [to] combine together in support of the winter sport and those who so well maintain the credit of the town in its practice’.80 There were many appeals in the name of North End’s distinguished history, such as the Post’s reminder that ‘in the past, as everyone knows, the team has been in the front rank of Association elevens, and with the support of the townspeople it will retain its old and proud position’.81 The arguments put forward, and the vocabulary employed, were almost identical in all three papers, suggesting that reporters were receiving the same briefings from the club, perhaps simultaneously, or that there was only one way for the local press to report the story, within the conventions of late nineteenth-century local journalism.

When the crisis ended, days before the start of the new season, it became apparent that another side to the story had been suppressed. As it became clear that enough shares had been sold to pay the club’s debts, the papers began to refer to earlier widespread fears among fans, now past, that the club might collapse. The papers had closed ranks, underplaying the depth of the crisis and adopting a boosting role, which left no room for the untidy, uncertain and fickle voices of the fans. Unlike the coverage at North End’s high point in 1888–89, the fans were noticeably absent from the reporting of the 1893 crisis. Only in mid-September did the Herald acknowledge ‘the, more or less, twaddle talked by some individuals during the heated period when the new company was being floated’.82 The slow take-up of shares suggests that many North End fans did not share the papers’ confidence in the viability of the club nor the ability of its managers.

Conclusions

Close reading and comparison of rival publications has revealed how Preston’s main newspapers reacted to another cultural movement, professional football. The symbiotic relationship of the local press and professional football benefited both parties, and the press took full advantage of the regional and local nature of the new phenomenon, adapting established techniques and adopting new ones to capitalise on local identity in its coverage. Whilst rivalry was intrinsic to football coverage, there was surprisingly little ‘othering’ of rival teams, beyond the bounds of sportsmanlike fair play. The emphasis was on ‘us’ rather than ‘them’.83 Sports coverage, particularly of football, enabled newspapers to package together many other elements of local identity into one topic, making local patriotism more intense and emotional. Football reporting provides a particularly good example of local newspaper boosterism — although there is little evidence that this boosting had any direct impact — and was well suited to combining identities at local, county, regional and national level. The habit of quoting and debating comment on local teams from other newspapers around the country strengthened and made use of the national network that was the local press.

Preston’s papers, regardless of their political stance, followed the same template when reporting the new phenomenon of professional football. It is hard to imagine how else they could have reported PNE’s triumphal homecoming after winning the FA Cup, an event that drew a quarter of the town’s population onto its main street. The exception was Hewitson’s Chronicle, perhaps confirming that by the late 1880s, he was out of step with contemporary journalism, despite his stylistic innovations in the 1860s and 1870s. The Preston press’s football coverage was usually more passive than Hill suggests, creating myths through selective repetition and through reporting, such as that around the FA Cup in 1889, in which the speech-makers at the Public Hall rather than the newspapers did the work of connecting North End’s victory to civic identity. But when PNE was nearly destroyed by a financial crisis in 1893, the Preston papers offered more active, partial constructions of reality, playing down bad news, wishing good news into existence and adopting a tone of exhortation, urging readers to buy shares and save the ailing club, for the sake of the town. The only other time such direct appeals to the reader were seen was during election campaigns. This is a case study of how the local press applied established techniques to the new phenomenon of organised, professional association football, to the mutual benefit of the press and the football club. The next chapter argues that such selection and framing of stories did have an impact on some readers.

1 For a superb account from an earlier period of local identity and sport (in this case cricket), see Mary Russell Mitford, ‘A Country Cricket-Match’, in The Works of Mary Russell Mitford, Prose and Verse (Philadelphia: Crissy & Markley, 1846), pp. 41–45.

2 Jeffrey Hill, ‘Rite of Spring: Cup Finals and Community in the North of England’, in Sport and Identity in the North of England, ed. by Jeffrey Hill and Jack Williams (Keele: Keele University Press, 1996), pp. 85–111 (pp. 102, passim).

3 Dave Russell, Looking North: Northern England and the National Imagination (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), pp. 13, 19.

4 David Hunt, The History of Preston North End Football Club: The Power, the Politics and the People (Preston: PNE Publications, 2000), p. 44.

5 Hunt, p. 54.

6 Hunt, pp. 17, 42, 76.

7 Anthony Mason, Association Football and English Society, 1863–1915 (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1980), p. 187; Thomas Preston, ‘The Origins and Development of Association Football in the Liverpool District, c.1879 until c.1915’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Central Lancashire, 2007), pp. 309, 311.

8 Mason, p. 193; Bob Clarke, From Grub Street to Fleet Street: An Illustrated History of the English Newspaper to 1899 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), p. 129.

9 Alexander Jackson, ‘Reading the Green ’Un: The Saturday Football and Sports Special as a Consumer Product and Historical Source’, 2007, unpublished manuscript, p. 12.

10 Tony Mason, ‘All the Winners and the Half-Times’, The Sports Historian, 13 (1993), 3–13 (p. 12), https://doi.org/10.1080/17460269309446373

11 Alan J. Lee, The Origins of the Popular Press in England: 1855–1914 (London: Croom Helm, 1976), p. 127.

12 Both editions of Monday 5 February 1900 carried results from Divisions 1 and 2, but where the northern edition had results from the Lancashire League, the Lancashire Combination, the Lancashire Alliance and other Manchester and Lancashire leagues, the southern edition had instead results from the Southern League, the Midland League and the Kent League. For 5 February and 3 December 1900, there was an average of sixty-four column inches of sports coverage from north of Watford in the northern edition, compared with an average of twenty-three inches in the southern edition. Quantitative analysis of the 1908 editions does not capture the differences as well: the same FA Cup matches were given equal space in each edition in February 1908, but were written from northern or southern perspectives.

13 J. A. H. Catton, The Rise of the Leaguers: A History of the Clubs Comprising the First Division of the Football League : Reprinted from the Sporting Chronicle (Manchester: Sporting Chronicle, 1897), p. 95, cited in Steve Tate, ‘The Professionalisation of Sports Journalism, c.1850 to 1939, with Particular Reference to the Career of James Catton’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Central Lancashire, 2007), p. 219.

14 ‘Total sport’ includes sport from outside Lancashire and international fixtures.

15 Multiple editions were viewed on microfilm at the Lancashire Evening Post (LEP) office, Preston.

16 See also Preston Herald (hereafter PH), 19 December 1888, 16 January and 20 February 1889.

17 Diary of Anthony Hewitson, Lancashire Archives DP512 (Hewitson Diaries hereafter), 15 November 1884.

18 Hewitson Diaries, 13 December 1884.

19 Preston Chronicle (hereafter PC), 22 September 1886, p. 5.

20 PC, 26 March 1887. This letter received an appreciative response from another reader the following week.

21 Hunt, pp. 92–93. I am grateful to Dr Steve Tate for information on Coupe; see also Tate, pp. 125–26.

22 PC, 6 September 1890.

23 LEP, 7 January 1888, p. 3.

24 Preston PhD, pp. 302–3, 306–7.

25 LEP, 20 October 1888; PH, 10 September 1890, p. 2.

26 Mason, ‘All the Winners’, p. 3; Mason suggests that this tradition was created by the pioneering sporting paper Bell’s Life in London, which promoted and sponsored sport, and whose editors often acted as stakeholders in wagers: Tony Mason, ‘Sporting News, 1860–1914’, in The Press in English Society from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries, ed. by Michael Harris and Alan J. Lee (London: Associated University Presses, 1986), p. 172.

27 PH, 16 January 1889.

28 PH, 1 November 1893.

29 LEP, 1 April 1889.

30 Russell, Looking North: Northern England and the National Imagination, p. 241.

31 LEP, 15 September 1888; PH, 2 January 1889.

32 PH, 16 January 1889.

33 John Bale, ‘The Place of “Place” in Cultural Studies of Sports’, Progress in Human Geography, 12 (1988), 507–24 (p. 514).

34 PH, 2 January 1889; LEP, 5 February 1889; PH, 6 February 1889.

35 LEP, 9 February 1889.

36 PH, 27 March 1889.

37 Jeffrey Hill, ‘Anecdotal Evidence: Sport, the Newspaper Press and History’, in Deconstructing Sport History: A Postmodern Analysis, ed. by Murray G. Phillips (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006), pp. 117–29 (p. 122).

38 Jackson, ‘Reading the Green ’Un’, p. 5; Alexander Jackson, ‘Football Coverage In The Papers Of The Sheffield Telegraph, c.1890–1915’, International Journal of Regional and Local Studies, 5 (2009), 63–84 (pp. 80, 63), https://doi.org/10.1179/jrl.2009.5.1.63

39 PH, 5 September 1888.

40 PH, 16 January 1889.

41 PH, 13 February 1889.

42 Martin Johnes, Soccer and Society: South Wales, 1900–39 (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2002), p. 10.

43 LEP, 16 February 1889.

44 This was not unusual: Dave Russell, Football and the English: A Social History of Association Football in England, 1863–1995 (Preston: Carnegie, 1997), p. 65.

45 LEP, 2 March 1889, 1 April 1889.

46 LEP, 17 November 1888.

47 PH, 30 March 1889.

48 LEP, 3 April 1889.

49 LEP, 16 March 1889.

50 LEP, 30 March 1889. At other times, Lancashire dialect was used, as in ‘those who were not present may lay the flattering unction to their soul that, to use a Lancashire term, “they missed nowt”’: ‘Notes by Prestonian,’ PH, 6 September 1893, p. 6.

51 LEP, 12 January 1889. For more north-south rivalry concerning the Corinthians, see LEP, 2 February 1889; Jackson, ‘Football coverage’, p. 64. ‘In the South there is not the enthusiasm shown in the sport as in other parts, and the lethargic Southern amateur will wait for the cool breezes of October before he ventures on his exertions’: LEP, 26 August 1893. For more on sport and northern identity, see Jeff Hill and Jack Williams, ‘Introduction’, in Sport and Identity in the North of England, ed. by Jeffrey Hill and Jack Williams (Keele: Keele University Press, 1996), pp. 1–12; in the same book, Richard Holt, ‘Heroes of the North: Sport and the Shaping of Regional Identity’, pp. 137–64 and Tony Mason, ‘Football, Sport of the North?’, pp. 41–52.

52 Hunt, pp. 17, 59.

53 Stacy Lorenz believes that high numbers of supporters were evidence that the host city ‘had successfully demonstrated its energy and vitality’: Stacy L. Lorenz, ‘“In the Field of Sport at Home and Abroad”: Sports Coverage in Canadian Daily Newspapers, 1850–1914’, Sport History Review, 34 (2003), 133–67 (p. 149), cited in Preston, p. 289, https://doi.org/10.1123/shr.34.2.133

54 Bale, p. 516.

55 The Preston papers occasionally contrasted the behaviour of football and cricket crowds, without making judgments (PH, 20 March 1889); cricket spectators were not incorporated into the reportage in the same way, perhaps because cricket was a participatory rather than a spectator sport.

56 Russell, Looking North, p. 56. For the view that the late nineteenth-century press saw itself as ‘representative’, see Mark Hampton, Visions of the Press in Britain, 1850–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004).

57 Alexander Jackson, ‘The Chelsea Chronicle, 1905 to 1913’, Soccer & Society, 11 (2010), 506–21 (pp. 515–19), https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2010.497341; the Sheffield publication Football and Cricket World exemplified this northern attitude. ‘We do not believe in the wishy-washy talk about no partisanship being felt. We want to see Sheffield football triumphant’: Football and Cricket World, 9 September 1895, cited in Jackson, ‘Football Coverage’, p. 69.

58 LEP, 15 September 1888, 11 February 1889; PH, 12 December 1888.

59 LEP, 13 October 1888. The Liverpool Echo ‘Saturday Night Football Edition’ included imagined dialogues between fans: Preston, p. 287.

60 LEP, 12 January 1889.

61 LEP, 12 January 1889.

62 LEP, 20 October 1888.

63 LEP, 13 October 1888, p. 4.

64 Hill, ‘Rite of Spring’, p. 94.

65 PH, 30 March 1889. Without access to all editions of the Herald, it is impossible to know for sure that no post-match edition appeared.

66 PH, LEP, 30 March 1889.

67 LEP, 6 April 1889.

68 PH, 3 April 1889, p. 5. Even at this early date, the occasion was less a ‘spontaneous celebration of club’ and more a ‘semi-official glorification of town’, challenging Hill’s chronology: Hill, ‘Rite of Spring’, p. 100.

69 Mike Huggins, ‘Oop for t’ Coop: Sporting Identity in Britain’, History Today, 55 (2005), 55–61.

70 PH, LEP, 3 April 1889; PC, 6 April 1889, p. 5.

71 Hill, ‘Rite of Spring’, p. 102.

72 Hill, ‘Anecdotal Evidence’, p. 121; Bale, p. 516.

73 PC, 15 July 1893; PH, 19 July 1893.

74 PH, 22 July 1893; LEP, 11 August 1893. Surprisingly, none of the papers set an example by publicly buying shares themselves, although the Toulmins later ‘became large shareholders in the club’: Hunt, p. 12; the owners of the Eastern Daily Press bought twenty-five shares in Norwich City FC in the early twentieth century: Tony Clarke, Pilgrims of the Press: A History of Eastern Counties Newspapers Group 1850–2000 (Norwich: Eastern Counties Newspapers, 2000), p. 22.

75 PC, 12 August 1893.

76 LEP, 22, 23, 24 August 1893.

77 PC, 29 July 1893.

78 LEP, 10, 12 August 1893.

79 PC, 5 August 1893; LEP, 22 August 1893.

80 LEP, 21 July 1893; PH, 23 August 1893.

81 PC, 22 July 1893; LEP, 19 August 1893.

82 PH, 13 September 1893.

83 In Mary Mitford’s words, ‘to be authorised to say we’: Mitford, p. 43.