11. Visualizing Displacement Above The Fold

© 2019 Lorie Novak, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0153.11

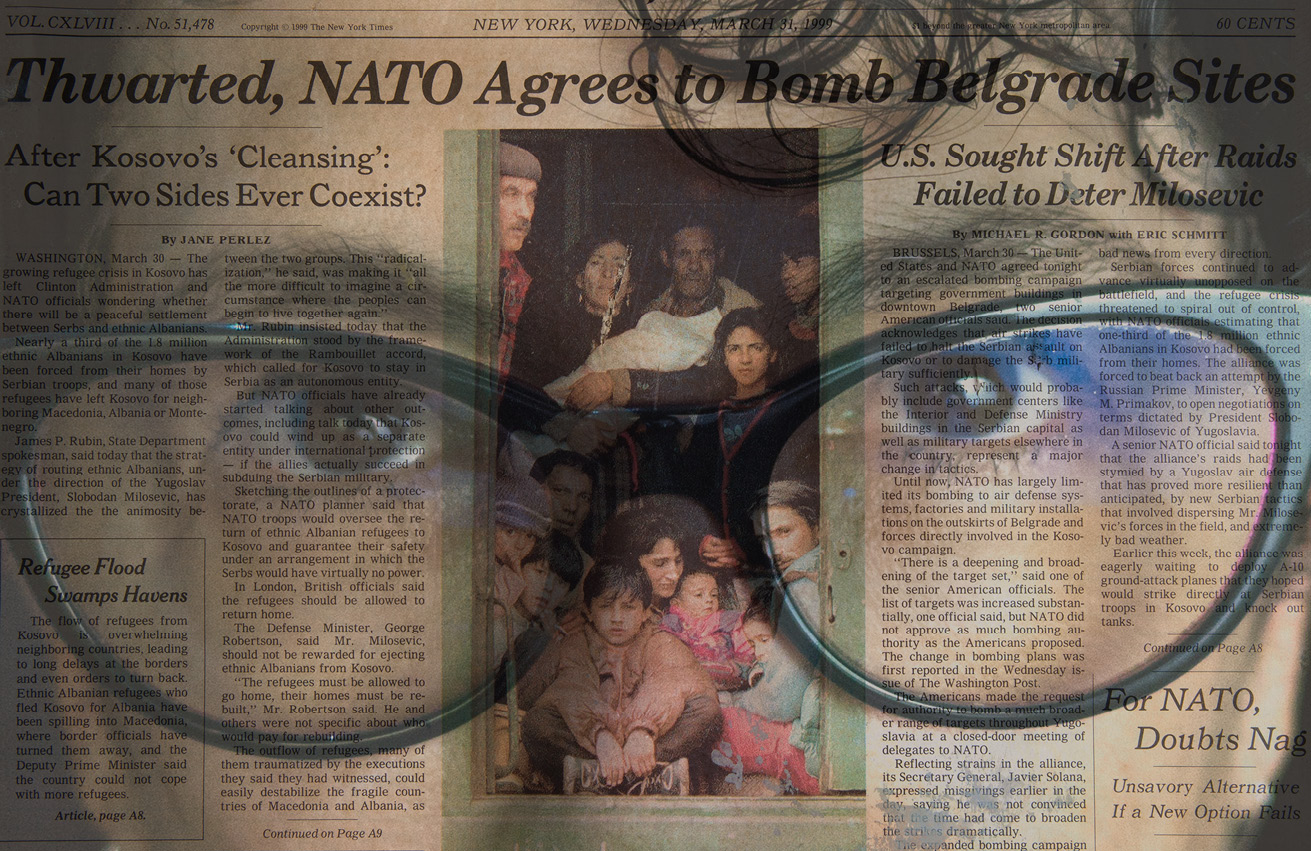

Fig. 11.1 Lorie Novak, ‘Reading the News’, 1999, CC BY-NC-ND.

In early 1999, photos of displaced families in the former Yugoslavia were appearing on the front page and throughout The New York Times. I was deep into my Collected Visions project in which I was collecting photographs from over 300 people to understand how family snapshots shape our memory (see http://collectedvisions.net). I was clipping more photographs from newspapers than usual. The war in Kosovo had been going on since 1996, but now more photos were appearing to draw our attention to the conflict. As it became clear in March 1999 that NATO was going to bomb Serbia in response to the attacks against Albanians in Kosovo, I made the decision to start saving the entire front section of The New York Times once the bombing started. My idea was to have a stack of newspapers that signified a war.

On 24 March 1999, NATO began air strikes with the bombing of Serbian military positions in the province of Kosovo and I began saving the front pages. When the air strikes ended on 10 June 1999, and ethnic Albanians began returning to their homes, it did not seem that a true resolution had been reached, so I kept collecting. The World Trade Center was attacked, and I kept collecting. I have not stopped.

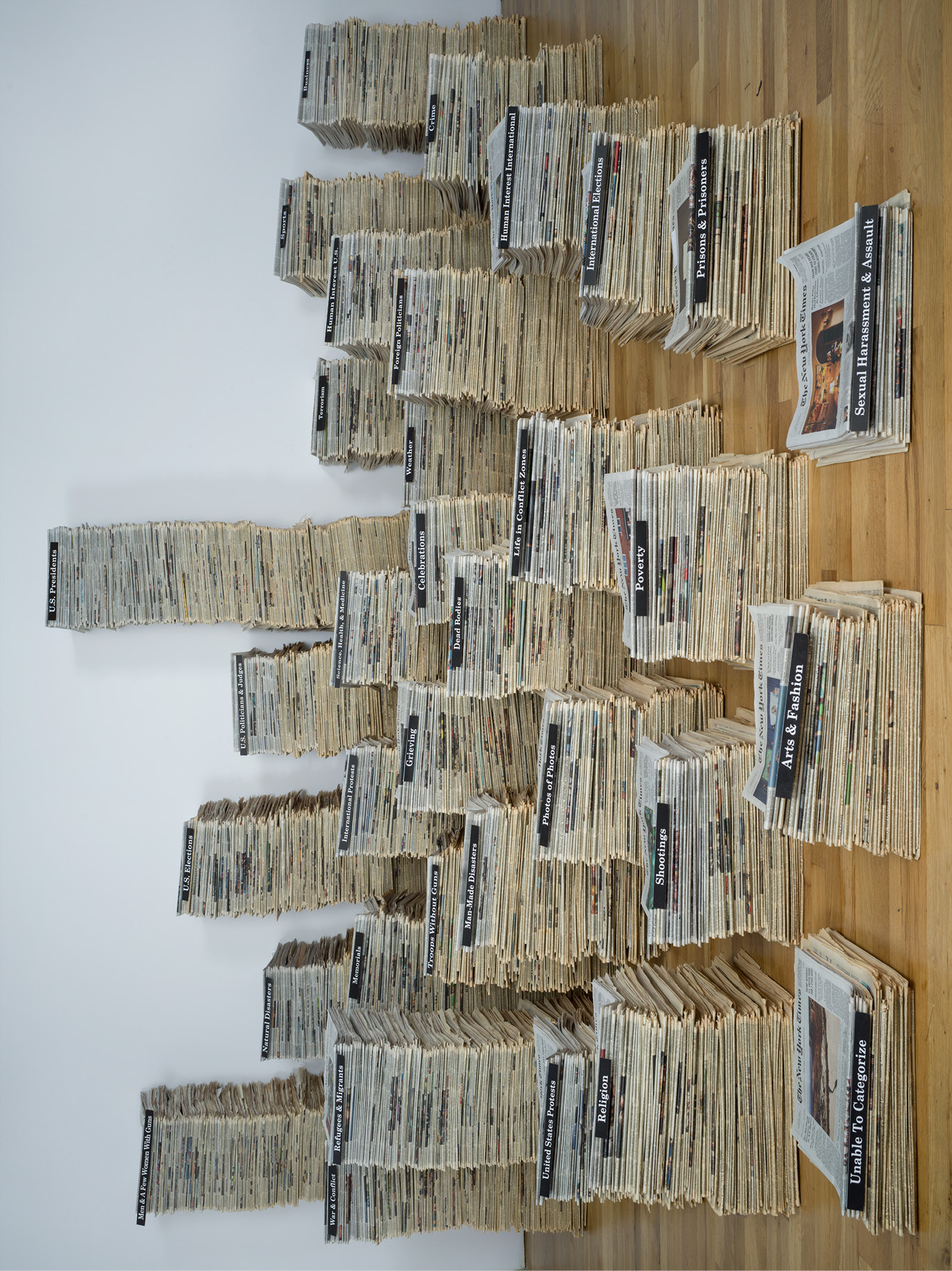

Fig. 11.2 Lorie Novak, ‘Above The Fold’, in my studio, July 2018, CC BY-NC-ND.

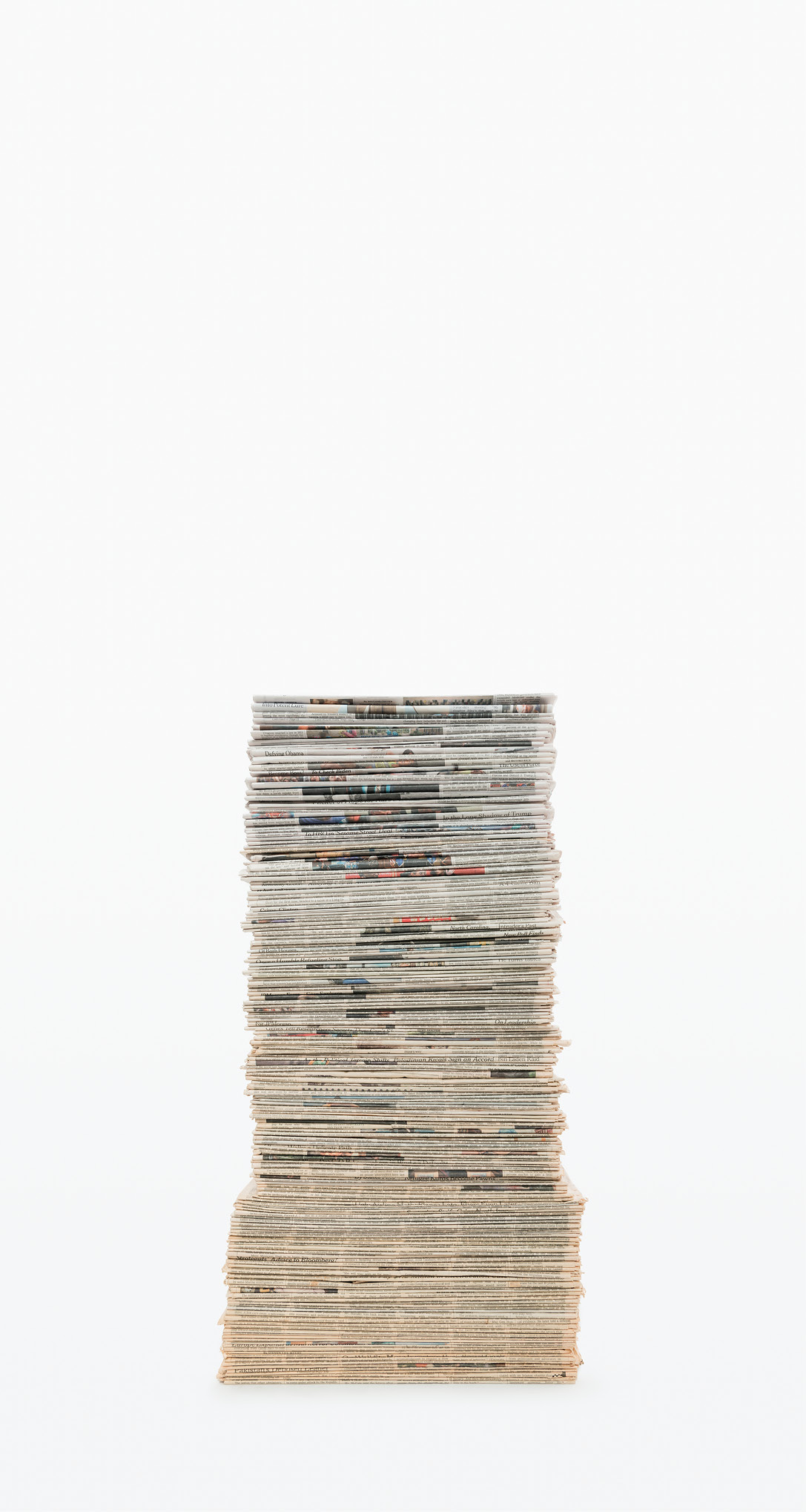

Counting Speaks Volumes

Jumping ahead to the present, there are over 7,000 New York Times front-page sections in my studio sorted into 33 categories suggested by the photographs that appear above the fold. I approach my analysis as an artist. To determine how to sort the newspapers, I let the front-page photos talk to me. Subject matter that appears over and over includes men with guns, dead bodies, people grieving, people holding photos, memorials, protest, bombings, shootings, refugees, migrants, natural disasters, daily weather, sports, US presidents, and politicians campaigning.

Determining categories was often a challenge. For example, I struggled over how to define war and terrorism. I settled upon the category War & Conflict to include images of state sponsored violence, and Terrorism to include images where violence was perpetuated to harm as many innocent people as possible because of their ethnicity, religion, gender, etc. Over the years, the relative sizes of the categories changed as photographic trends and political attitudes emerged and evolved. More dead bodies appeared, the number of photographs of refugees grew, and politicians campaigning appear more frequently. In late 2017, the attention given to cases of sexual harassment and assault on the front page allowed me to form a new category. Nonetheless, as of July 2018, there are only thirteen papers in this category (the first one appears in 2006), replacing Arts & Fashion as the smallest pile.

Images can often be classified in multiple categories, and I had to establish a sorting structure. In determining the hierarchy of image content, I let go of the neutrality I had sought for image classification.

Fig. 11.3 Lorie Novak, ‘Men & A Few Women With Guns’, 60’ x 32’, inkjet photograph, 2017, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 11.4 Lorie Novak, ‘Dead Bodies’, 60’ x 32’, inkjet photograph, 2017, CC BY-NC-ND.

Men With Guns, Dead Bodies, Grieving, Protest

As I began categorizing the photographs, what first stood out to me was the prevalence of guns. To show how the image of a man with a gun is glorified, I gave those photographs top priority. (Women holding guns appear fewer than 10 times.) Not surprisingly, Men & A Few Women With Guns is the second tallest pile after US Presidents. Dead Bodies, Grieving, and Memorials are the next 3 categories in my hierarchy and a window into how trauma and violence are visualized and given importance. The most heart-wrenching photos can be found in Grieving.

Protests as a whole comprise a sizeable portion of the collection, yet foreign protests are given far more prominence than protests in the United States. For instance, in the three years from 2011 to 2013, there were forty-two images of protests in Egypt alone, while there has been a total of ninety-five photos of the protests in the US spread over the entire nineteen years from the start of my collection through 2017. It is rather startling that only four photographs of anti-Iraq-War protests made it above the fold.

Images of protest of the Trump Administration’s immigration policies have appeared six times since his inauguration on 20 January 2017 until 27 July 2018, the court-determined deadline for reuniting migrant families separated at the southwest border. In these eighteen months, other images of US protest include women’s marches: twice; anti-abortion protest: once; gun reform marches: six times; anti-racism protests: twice. That is a total of seventeen front-page photos as compared to eighteen of international protests.

Refugees and Migrants

Images of refugees were the impetus for this project. When I am lost in my archive, I think about the visualization of refugees and migrants in the mainstream US media and our current crisis caused by Trump with his travel ban, anti-immigrant rhetoric and violence, as well as more blatant racism and misogyny. I have conducted a close read of the images of refugees and migrants that have appeared above the fold of The New York Times from the beginning of the War in Kosovo in March 1999 to 27 July 2018.

Date |

Category |

Total |

|

March–December 1999 |

1 Chechnya |

17 |

|

2000 |

1 Hong Kong |

8 |

|

2001 |

2 Afghanistan 2 Macedonia |

7 |

|

2002 |

2 Afghanistan |

5 |

|

2003 |

1 Zimbabwe |

3 |

|

2004 |

1 Hong Kong |

4 |

|

2005 |

7 |

|

|

2006 |

1 Colombia 1 Guatemala |

12 |

|

2007 |

1 Laos |

12 |

|

2008 |

1 Guatemala 1 Zimbabwe |

7 |

|

2009 |

1 Afghanistan 1 Colombia, 1 Ecuador |

11 |

|

2010 |

1 Botswana, 2 Kyrgyzstan |

9 |

|

2011 |

1 Botswana 1 Tunisia |

7 |

|

2012 |

1 Afghanistan 1 Colombia |

12 |

|

2013 |

1 Afghanistan |

10 |

|

2014 |

1 Myanmar |

19 |

|

2015 |

4 Myanmar 1 Yemen |

32 |

|

2016 |

1 Cameron 1 Niger |

20 |

|

2017 |

1 Afghanistan 1 Guatemala 1 Ecuador 4 Rohingya from Myanmar |

19 |

|

1 January–28 July 2018 |

1 Guatemala 1 Niger |

15 |

The horrors of the war in Kosovo in 1999 were depicted by displacement of families, as evidenced by fifteen front pages with photos of refugees from Kosovo. The plight of the refugee family continued into 2000, but with a shift in locale and a shift in tone to family melodrama. Seven of the eight refugee/migrant photos above the fold that year depicted the battle over the custody of five-year-old Elián González, who was found floating alone on an inner tube near Miami after leaving Castro’s Cuba with his mother, who drowned on the journey.

As our century has progressed the visualization of the refugee/migrant has become more complicated. More countries are represented and the displaced family is no longer the dominant trope. Three photos in the Dead Bodies category are of migrants. Five front pages in US Protests are about refugees and migrants during the sixteen years of the Presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama. Photos depicting protest against the Trump administration’s travel ban and executive orders on immigration have appeared six times during his first eighteen months in office.

Advances in digital photography and cell phone cameras have had a huge impact on the range of images. We are much more aware of the perilous journeys migrants undertake, in part because of social media and the images circulated by refugees themselves and by the NGOs and volunteers helping them. With thirty-two images, 2015 has the most photos in one year in this category. The fact that 2016 has a third fewer photos despite the continued crisis of refugees and migrants worldwide may be a result of the seventy-six front page photos covering the 2016 presidential campaign and its aftermath. In 2017, nineteen images appeared depicting the number of Central American and Mexican migrants increasing. In the first seven months of 2018, focus has shifted in US media to the crisis at the US southern border and the cruel treatment of Mexican and Central American migrants seeking asylum.

Statistics can speak for themselves, with absence often speaking as loud as presence.

Fig. 11.5 Lorie Novak, ‘Refugees & Migrants’, 60’ x 32’, archival inkjet photograph, 2017, CC BY-NC-ND.

When I started this project in 1999, newspapers were primarily a print medium, and thus all New York Times readers saw the same front-page photo. But now, online reading is dominant. I, and many like me, go to nytimes.com several times a day, and each time I am greeted by a different photo that is often overshadowed by a large advertisement looming above. Usually that image on the screen is part of a slideshow or is not a photo but a video. If you return to the site later, that image may no longer appear and it is often hard or impossible to find again. The single image on the printed front page (or even the scanned version of ‘Today’s Paper’ online) with no competing advertisement is a static and often powerful counterpart to the 24/7, always changing, up-to-the-minute online news cycle.

I look forward to opening my door each morning to pick up The New York Times to see what one photograph has been chosen to represent the news of the day. There is still power in the act of holding an image. My hope is that the image above the fold will give more attention to the ongoing worldwide refugee crises, anti-immigrant, racist, and misogynist sentiments and acts of resistance growing worldwide. I am often disappointed.

Fig. 11.6 Lorie Novak, ‘Reading the News’, 2018, CC BY-NC-ND.