14. Reinventing the Spaces Within: The Early Images of Artist Lalla Essaydi1

© 2019 Isolde Brielmaier, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0153.14

I am writing. I am writing on me, I am writing on her. The story began to be written the moment the present began. I am asking, how can I be simultaneously inside and outside? I didn’t even know this world existed, I thought it existed only in my head, in my dreams.

— Lalla Essaydi, excerpt from autobiographical text written on a photograph

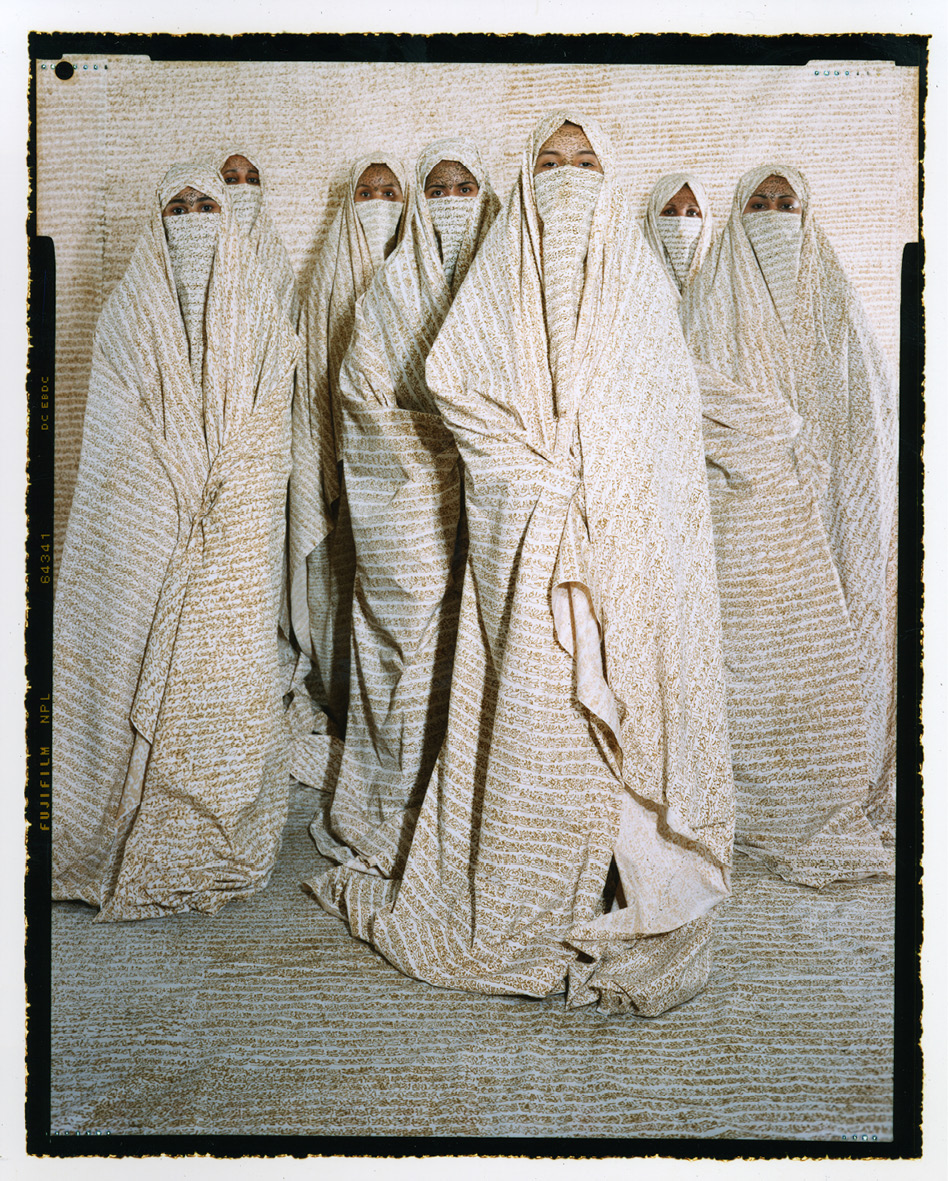

Fig. 14.1 Lalla Essaydi, ‘Converging Territories #26’ (2000–01). © Lalla Essaydi, New York. Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

At the beginning of the year 2000, Lalla Essaydi began working on a body of photographs that are set in Morocco, in a large, unoccupied house belonging to her family. She had spent some time thinking about this particular interior because it was here that she was sent, as a young girl, when she disobeyed or stepped outside the permissible spaces of her culture. She was accompanied by servants but spoken to by no one, ultimately spending up to an entire month in this house alone at various times. Often, she would sit and do nothing. At other moments she imagined the world outside, bringing it inside by the force of her imagination. Years later, that house — with its cool, stone walls and the enclosed spaces of its dark rooms — is, for Essaydi, both a literal and psychological space delineated by her experiences there, marked by the memories that she articulates in her photographs.

Essaydi’s earliest work began as a continual exploration of this tenuous relationship between memory and experience. It enabled her to revisit her early memories, to encounter her past in order to cast it visually and publicly in the light of the present. She explains that ‘after having visited this house many times in making some of my earliest photographs, and thinking about my own complex relation as artist to this space of childhood, I have become aware of another, less tangible, more ambiguous space […] the space of imagination, of self-creation.’2 Today, as a woman and artist, Essaydi’s view of her childhood is richly informed by and filtered through the sum of her reflections, experiences, and ever-broadening perspective. She has used her art to expand the cultural pictures of Islam, Arab women, the role of a photographer, and the power of the image, in all their complexity. Her introspection and clear intention are evident in many of her photographs: we see Essaydi turning ‘space’ into something more than just the delimited enclosures of that house of her childhood.

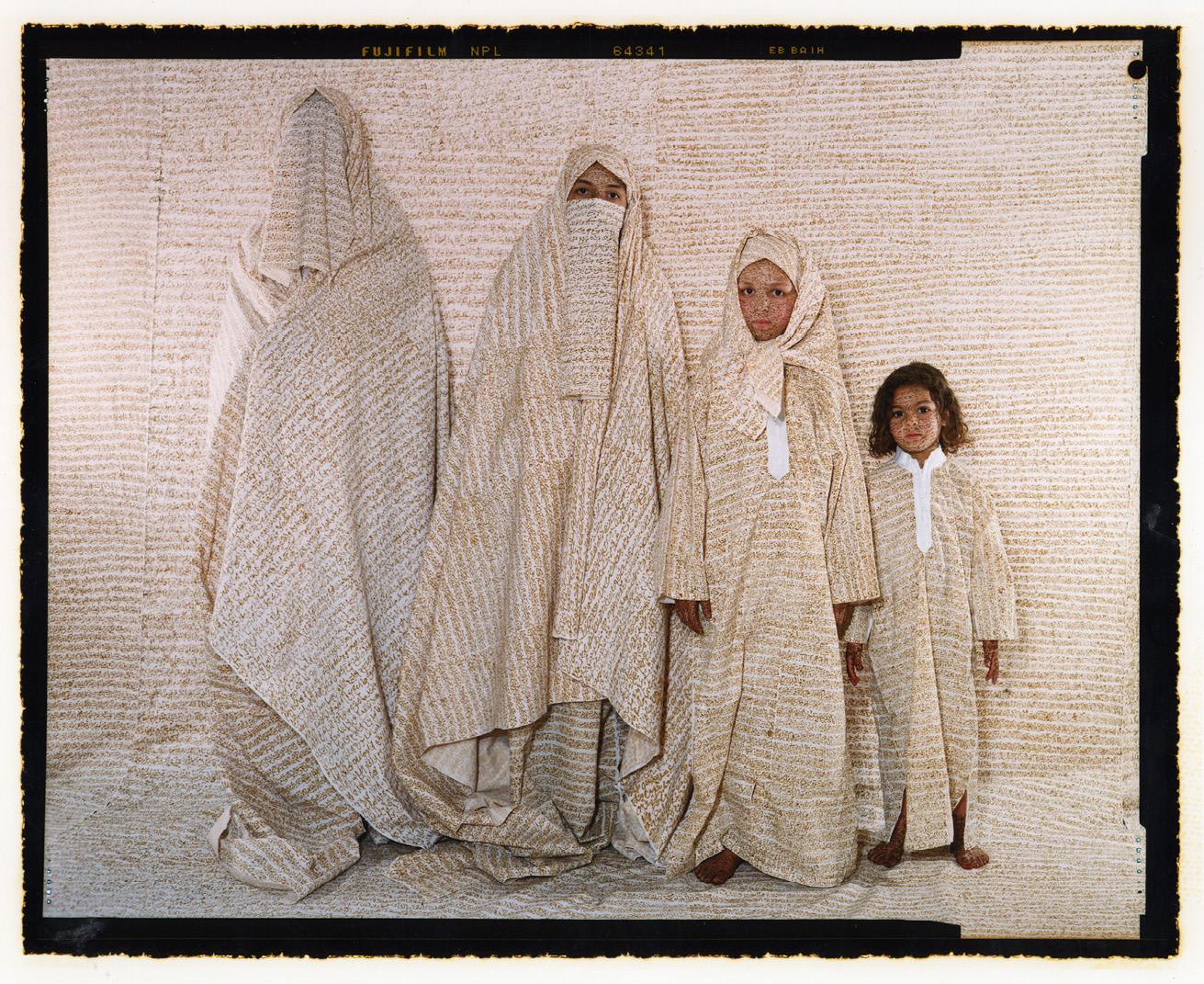

Fig. 14.2 Lalla Essaydi, ‘Converging Territories #30’ (2000–01). © Lalla Essaydi, New York. Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

Traversing boundaries and expanding ideas of physical and social space are not new challenges for Essaydi. She has lived in many locations, and in many fundamentally divergent cultures. She grew up in Morocco and lived for many years in Saudi Arabia. She attended classes at L’École des Beaux Arts in Paris, and then moved to Massachusetts, where she received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Tufts, and later completed her Master of Fine Arts at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Currently, she works and resides in the United States. From her earliest efforts as both a painter and a photographer, Essaydi has been concerned with the status, perception, and self-perception of Arab women, with the diversity within Muslim culture, and above all with the malleable nature of identity itself. She makes no claim to serve as a spokesperson for all Arab women. Instead, Essaydi has focused on presenting to Arab, European and American audiences the multifariousness of Arab female identities. She seeks to convey these ideas and intersectional experiences through a personal perspective that brings together her reflections and interpretations of her own life. ‘In my art,’ Essaydi says, ‘I wish to present myself through multiple lenses — as an artist, as Moroccan, as traditionalist, as liberal, as Muslim. In short, I want to invite the viewer to resist stereotypes and rigid categorizations; to think and see in new ways.’3

In her earliest series, ‘Converging Territories,’ Essaydi highlights and then expands upon the concept of space by positioning her female subjects within an enclosed area — she staggers their bodies, ‘pushing’ them up against a flat wall to create the sense of an overflowing, crowded field (see Fig. 14.1). The women blend with the walls and tiles of the seemingly narrow spaces within the photographs’ frames. They appear confined as well as decorative — referencing European fantasies and presumptions about Arab culture and Islam. The images very clearly echo common tropes of Orientalist painting — the odalisque, the mystery of concealment, the veil, the harem. Yet Essaydi, in urging for a critical reconsideration, is pushing for something else as well.

Conceptually, the notion of ‘space’ in Essaydi’s work extends beyond the physical realm. In her photographs the artist interrogates psychological and social spaces through the use of poses, clothing, and the activities of the women depicted. She uses these visual details to resist the more familiar images of Arab women, where the viewer is given a sort of voyeuristic entrée into a foreign, ‘forbidden’ and often, static culture. Instead, the women’s poses, their gestures and actions as well as their clothing are in many ways self-referential, defying the age-old binary notion of a margin-to-center relationship. For as Françoise Lionnet has asserted, this more traditional approach relies ultimately upon transnational minorities remaining in a reactive state, focused on the idea of a dominant majority rather than being actively engaged in the relationship with and significance of one another.4 Accordingly, the women in Essaydi’s image draw the viewer’s attention to the built environment in which their bodies are situated and to the ways in which this environment exists in a culturally specific mode — one that references ‘the Far East’ and ‘Arab’ cultures — within the mind. As we scan the image as viewers we map our own visions and ideas onto this space, often drawing on Orientalist tropes. Yet the artist underscores that how we see the image is actually resisted by the women pictured — in their poses, actions and gazes — and she thereby allows the women themselves to create it.

There is no doubt that her images are constructed. In the field of photography, where ‘authenticity’ and ‘truth’ are so often the goals, Essaydi’s work is plainly performative; it is purposefully artificial. The models are family acquaintances who are fully aware of her project and of their involvement within it. And although the softly lit interiors often appear smaller than they actually are, crowded with the physical forms of women, the viewer is also made aware of the expansive female power inherent in the women’s collective presence. In this way, the women pictured also dictate the definition of the space, blurring any perceived notion of a major and minor relationship.

In the image from ‘Converging Territories’ that opens this piece, seven women fill the frame of the photograph entirely. Although concealed in willowy, white cotton haiks, they nonetheless engage the viewer directly with their full-frontal poses. Essaydi also creates calligraphic writing in henna, marking the subjects’ bodies with this sacred Islamic art that is usually inaccessible to women. By subversively combining calligraphy, a ‘male-only’ art form, with henna, a traditionally ‘female’ adornment, Essaydi and her subjects have turned a confined area into their own private space of creative transgression.

As Essaydi puts it: ‘The ‘veil’ of decoration and concealment has not been rejected but instead has been integrated with the expressive intention of calligraphy.’ Her photographs thus convey agency through a sort of cultural self-appropriation. Visually, they break with traditional codes of conduct and dress in order to relay cultural memory, experience, status, and history. And the women pictured somehow appear to subsume their own cultural markers, powerfully transforming them into something else; something that is both ‘other’ and yet still their own.

At a time when many of the images in circulation continue to portray Arab people in increasingly negative and insidious ways, Essaydi reclaims and reconsiders ideas of what it means to be Arab and female on her own terms. She says: ‘My photographs are about the women subjects’ participation in contributing to the greater emancipation of Arab women, while at the same time conveying to an outside audience a very rich tradition of practice, relationships, and ideas that are so often misunderstood and misrepresented in the West.’5 She rejects a simplistic reading of Islamic culture. Islam, as depicted in her work, is multi-layered. It is both confining and liberating, fluid and rigid. It is, in essence, indefinable. And in this context, Essaydi challenges not only our perceptions of Muslim societies, but also our expectations of a photographer in this world. What are we expecting to see when we look at a picture of veiled Muslim women? What is Essaydi revealing to us? What is she concealing? What ‘truths’ do photographs really hold, and whose stories do they tell?

1 This essay has been expanded by the author based upon her Spring 2005 article in Aperture magazine, ‘Re-Inventing the Spaces Within: The Images of Lalla Essaydi’, Aperture, 178 (2005), 20–25, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24478815

2 Conversation with the artist, New York City, Winter 2005.

3 Ibid.

4 Françoise Lionnet, ‘Transcolonial Translations: Shakespeare in Mauritius,’ in Françoise Lionnet and Shu-mei-Shih (eds.), Minor Transnationalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), pp. 201–22 (p. 207).

5 Conversation with the artist, New York City, Winter 2005.