16. Kinship, the Middle Passage, and the Origins of Racial Slavery

© 2019 Jennifer L. Morgan, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0153.16

As the transatlantic slave trade developed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, African women and the appropriation of their bodies were at the heart of the development of racial slavery. Slave traders and slaveowners both violently appropriated their bodies and attached meaning to their reproductive potential in ways that powerfully echo in the aftermath of slavery. The very idea of race depends on a notion of heredity that is impossible to think about without controlling the ‘issue’ of women’s wombs. The women who were the first forced migrants of the African diaspora comprise a foundation on which the edifice of racial slavery rests — but that foundation is not merely symbolic, it is material, and it reverberates not just for the European men who demanded their compliance, but for the African women who refused it. The story of the Black diaspora is rooted in African women’s wombs.

From the very first written descriptions of European involvement in the slave trade, even before large numbers of captives were being transported across the Atlantic, traders understood enslavement and reproduction to be interwoven. Before 1700 it was quite common for slave ships to transport equal numbers of women and men to slavery in Europe and the Americas, and at times ships were packed with significantly more female captives than male. Indeed, among all migrants to the Americas, both voluntary and involuntary, African women outnumbered European women by four to one until 1800.1 African women, then, were there at the very beginning, and it was through their bodies that European slave traders and slave owners developed the notion of race on which Atlantic slavery depended. These women were among the first Africans enslaved by Europeans. Their reproductive capacity was embedded in the very fact of their enslavement, a core part of the way they learned to understand the new terms of their vastly altered reality.

On a single cold day in February 1663, for example, an English settler purchased twelve women and eight men, the female majority bound for his sugar fields but also, perhaps, purchased with the musings of his contemporary Richard Ligon in mind. Ligon wrote of the men and women purchased in Barbados that:

We buy them so as the sexes may be equal; for, if they have more Men than Women, the men who are unmarried will come to their masters, and complain, that they cannot live without Wives […] and he tells them, that the next ship that comes, he will buy them Wives, which satisfies them for the present.2

There is a lot to say about the way that this Englishman described the concession to African men’s desires, but for now, I want to read it only from the perspective of those twelve women. Arriving to a plantation, these women were summarily assigned either to a man with whom they had survived the crossing or to one on whom they had never laid eyes. They would then be subjected to a quick and clear education as to the outlines of their future and the presumptions on which that future rested. For these women, there was a clear connection between the terms of their labor in the cane fields, their sexual availability, and their reproductive future.

Although I want to attend primarily to what that meant for these women, it is important to reckon with another fact. The labor system, which so clearly subjected both women and men to a speculative violence based on their reproductive futures, took place in broad daylight. The twelve women and eight men sold at the Bridgetown port had experienced the shock of being marketed as part of the daily life of the colonial town. It was not until decades later that auction houses and slave markets became designated as permanently demarcated structures. Sales of enslaved men and women were part and parcel of the messy colonial society that greeted them when they disembarked after months of stultifying, disorienting travel. On corners, in the back of shops, in the post-office or the public house, on wharfs, on piers, on board ships, after long marches through towns and into the countryside, from the backs of wagons, inside urban living rooms, with a stranger, with a child, with a spouse, alone or in full view of those whose sale would come next. Sold by men, sold by women, sold by strangers, sold by those who had known them long enough to call them by a name.3 Sold, in other words, in hundreds and thousands of small transactions, in which their reproductive capacities and identities as women and men were simultaneously accounted for and dismissed as transactional rather than a matter of feeling or family. This is a manifestation of quotidian violence that we have simply not calculated. These are moments in which the potential for pity, compassion or connection were irrevocably set aside in favor of a moral economy where skin color enabled enslavement, and childbirth was relegated to the balance sheet.

This would have been brutally clear, even for women whose child-bearing capacity entered the equation of their capture and transport prior to the point of sale. In the 1440s, a Portuguese chronicler wrote of coming across a woman who his men tried to subdue and take on board ship along with her children. Her strength in resisting her assailants was surprising, and it was not until the three men who’d failed to force her into the boat realized that they could simply ‘take her son from her and carry him to the boat; and love of the child compelled the mother to follow after it,’ did they capture her.4 It was her identity as a mother that enabled her capture. If she survived her contact with the Portuguese, she would have spent the remainder of her life in the knowledge that her capture was inextricably linked to her love for her son.

Mothers and children, fathers and siblings, were always part of the Middle Passage and of the sales that ensued once ships landed in Europe and the Americas. The archive doesn’t always point clearly to them, but records of slave ships testify to the presence of childless women and mothers alike. Their stories come buried in some very brutal calculus. In 1683, according to agents of the Royal African Company stationed in Barbados, the ship Bright arrived with a third of the captives being ‘very small most of them noe better then sucking children nay many of them did suck theire Mothers that were on boarde.’ The captain responded to this complaint with an indifference towards the infants that would be shocking if not for one crucial detail: it had enabled the slave trade to begin in the first place. He argued that bringing them ‘cost not much and the ship had as good bring them as nothing.’5 His reasoning was logical, though the rational calculus covered far more complicated equations than he was capable of considering — equations that would be obvious to those nursing mothers and carers for motherless children, who would understand that their economic value would become tethered to their reproductive capacity in the Americas.

For some captured women, the linkage between their enslavement and their motherhood was even more entangled. We know from a variety of sources that children were born on slave ships. Perhaps the most famous is the first person account written by Ignatius Sancho who was himself born on a slave ship in 1729, and became a prominent writer and composer in eighteenth-century England. Sancho’s mother would have experienced the onset of her labor amidst the roiling rhythms of a fetid ship, and likely would have greeted her son’s birth with profoundly mixed emotions. Whatever the nature of those feelings, arrival to the Spanish colony of New Granada (Columbia) soon put an end to them: she died shortly thereafter of fever.6 Sancho’s mother was seemingly resigned to namelessness and obscurity, which was only interrupted by her son’s rise to literacy and public prominence. She gave birth to a child in an act that immediately and violently showed her that the future she had imagined was no longer in her grasp. Further, Sancho’s appropriation as the property of the Englishman who bought his mother embodied the reproductive logic of a system of slavery based on racial identity: the harsh fact of his mother going into labour on board the slave ship exemplified this logic in microcosm.

Her experience was not unusual. On board the ship James in 1675, one woman died days before the ship left the African coast where its crew had been loading men and women for months. It is very difficult to apprehend her misery. She ‘miscarreyed, and the child dead within her and Rotten, [she] dyed two days after delivery.’ The agony of the experience seeps through the disciplinary columns of the ship captain’s Account of the Mortality Aboard the James. The connections between her and another woman lost during the passage may not have been obvious to the crew. Yet, they seem intimately linked: a little over two months later, another mother on board the ship succumbed after what the captain saw as maternal madness. ‘Being very fond of her Child, Carrying her up and downe, wore her to nothing by which means fell into a feavour and dyed.’7

There were, of course, many women who survived the Middle Passage without being or becoming pregnant and without children to care for, or at least without children whom the captains felt compelled to record. But even then, their reproductive capacity was part of their earliest understanding of what was happening to them. The very first description of the end point of the Middle Passage was written in 1444 by a Portuguese chronicler, who described the sale of more than 250 men, women, and children at the Lisbon port:

[…] though we could not understand the words of their language, the sound of it right well accorded with the measure of their sadness. But to increase their sufferings still more, there now arrived those who had charge of the division of the captives, and who began to separate one from another, in order to make an equal partition […]and then was it needful to part fathers from sons, husbands from wives, brothers from brothers […] the mothers clasped their other children in their arms, and threw themselves flat on the ground with them, receiving blows with little pity for their own flesh, if only they might not be torn from them.8

The lesson learned on board this ship, by those both with and without family ties, would reverberate in an endless echo of dissonance and dependence, kinship and enslavement. Such a lesson would be equally excruciating for those who lost kin at the moment of sale, and for those who left kin far behind at the starting point of their capture.

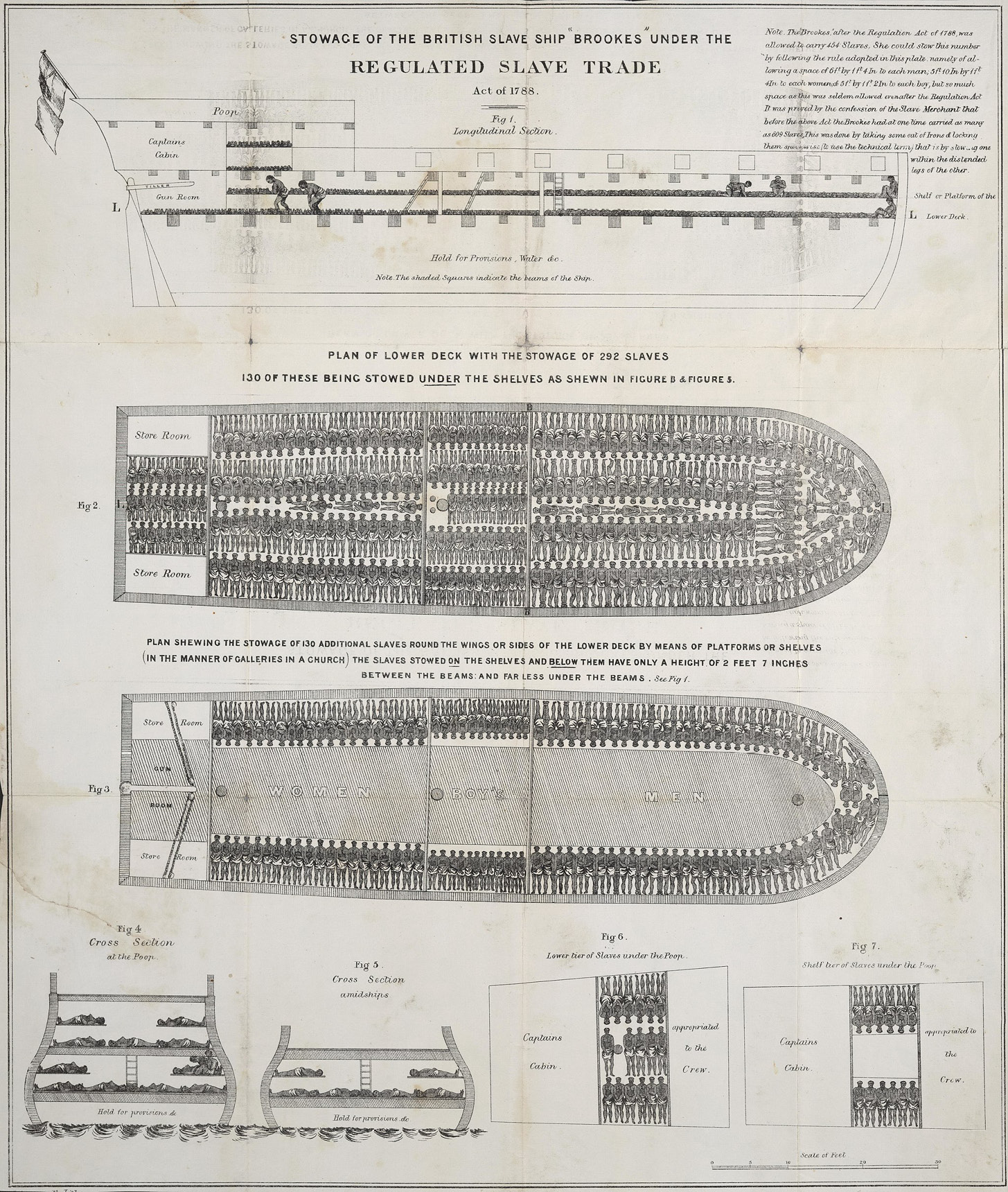

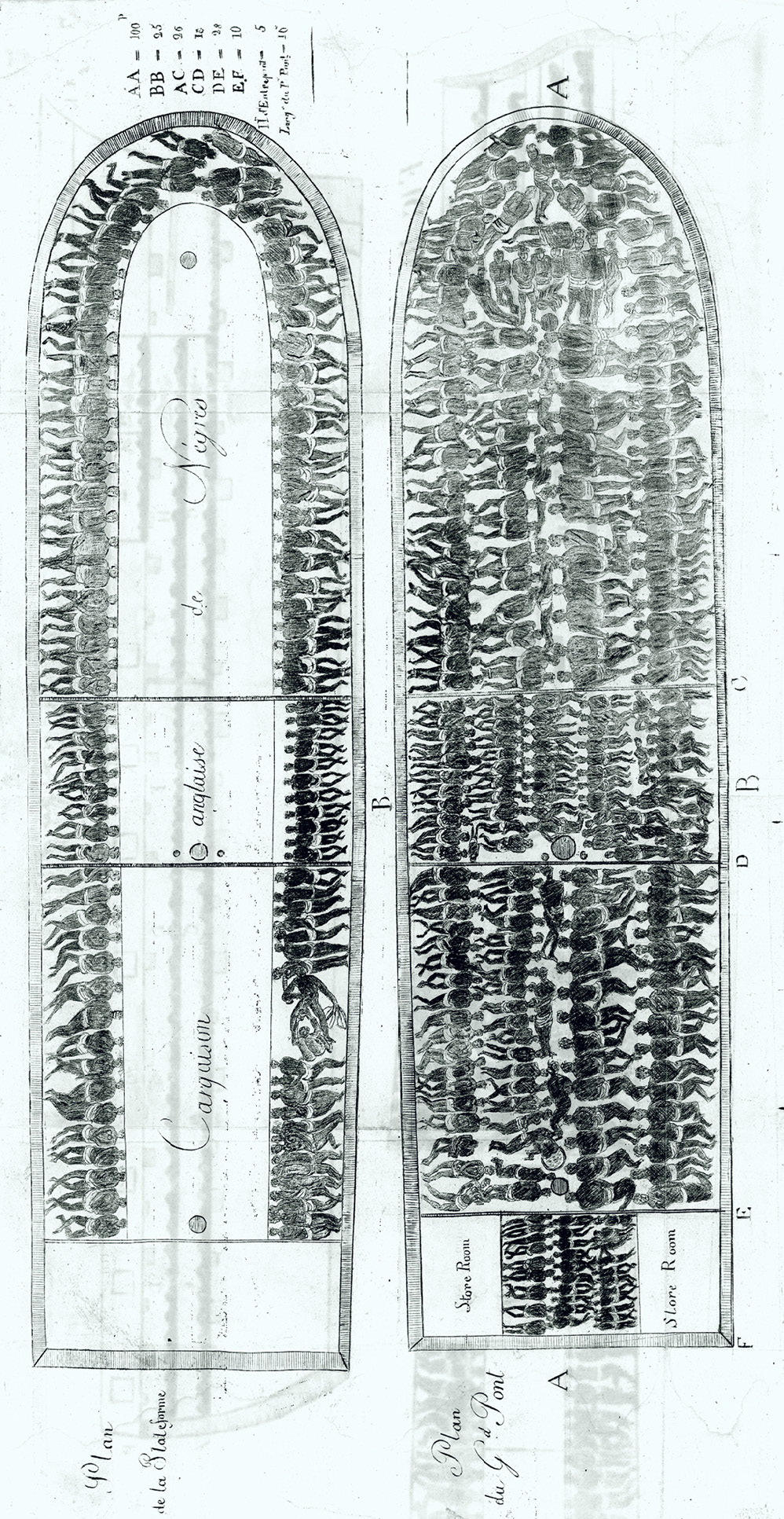

It appears, then, that women were there from the very first moment that Europeans contemplated the economic benefit of transporting captive laborers across the Atlantic ocean. If we know this beyond a shadow of a doubt, how does that change the way we visualize and understand the Middle Passage? Is the brutality of the slave ship perhaps best captured by the horrifying image of a woman giving birth on board? As we struggle to visualize the agony of forced migration and enslavement, the classic image of a slave ship is often the most powerful one to come to mind.9 Looking at Fig. 16.2 below, which circulated among abolitionist circles in the early nineteenth century, one can only assume that the illustrator inserted the image of the woman giving birth as a way to shock his viewers into action. Seen alongside the more ubiquitous image of the Brookes (Fig. 16.1), one can almost be forgiven for not immediately noticing her, and then being stunned at the moment of recognition. But the ability to include such a moment on board a slave ship depended on generations of evidence, of stories circulating, and experiences retold. The birth on board that ship was no more a surprise to the nineteenth-century viewer than the news that sugar on English tables and tobacco in their pipes depended upon hundreds of bodies crammed into those ships. The shock comes only from the inability to turn away, to close our minds to the truism that these floating portents of death and kinlessness were also spaces of birth. The reality was that the entire economy of the colonies depended upon African women giving birth to slaves, not to children — not to daughters, not to sons, not to kin. In order to fully face that reality, we must restore enslaved women to our understanding of what the Middle Passage entailed. Moreover, we must reflect on how their lives were embedded in the unfolding structures of the slave trade from its earliest iterations.

Succumbing to the shock of the nineteenth-century illustration will not suffice. Rather, we need to consider the ubiquity of such women’s presence in the slave trade in general. This means asking two crucial questions. First, how did that birth reinforce the reality of what slave trading meant? Second, how would being on board the slave ship have utterly and unimaginably transformed the experience of pregnancy, as well as the expectations attached to it? Such a mother would likely have been captured during the early stages of her pregnancy. In turn, the dawning reality of her condition would have probably coincided with the various phases of her capture — forced overland marches, confinement in a slave fort, a long wait on board a ship anchored close to land, and then the realization that the view of the coast and all it held was slipping permanently away. Her pregnancy marked her journey into a future that she could not have predicted, her desire to protect or parent her child growing increasingly impossible.

Fig. 16.1 ‘Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes Under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788.’ Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Slaveshipposter.jpg

Fig. 16.2 ‘Diagram of the Decks of a Slave Ship, 1814’, from Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, CC BY-NC 4.0, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/200410

Motherhood on board a slave ship was rarely a source of anything but increased vulnerability. Indeed, for some, it may have even occasioned further violation. This was the case for a woman known only by the number 83, which was assigned to her in the captain’s record of slaves. She was raped ‘brutelike in view of the whole quarter deck’ on a mid-eighteenth-century voyage to Jamaica. The captain promised that ‘if anything happens to the woman I shall impute it to him [that raped her], for she was big with child.’ Of course, something quite profound had already ‘happened to the woman’. She would join the other mothers on board that ship as they grappled with a perverted future foretold by their pregnant and captive bodies.11

Women were captured through their maternity, gave birth on ships, and watched other women succumb to maternal madness. They disembarked with children they’d grown attached to, or with groups of men whom they were expected to reproduce with. They were sold and moved and marched and led onto fields and into barracks, whether with or without a swollen belly and infants at the breast. In those hundreds and thousands of small transactions, women were learning something profound about the claims that were being made through their bodies, something that planted seeds and suggested origins. Focusing on the experience of the slave trade’s first female victims leads me to suggest that the Black Radical tradition is rooted there with them. It springs from that moment of transport and sale, when the relationship between capitalism and kinship was laid absolutely bare.

I use that phrase ‘the Black Radical tradition’ in homage to the late Cedric Robinson, who argued under the Black Marxist tradition that one could locate one’s origins in the Maroon camps of the seventeenth-century Caribbean and Latin America. Here we find an articulation of political sovereignty routed through ethnic cohesion, a retention of the African past, military engagement, and the claim-making of territoriality.12 But political sovereignty is not the only route to radical thinking. Perhaps maternity is as well.

I am not making an argument about motherly love, or the redemptive power of parenting under the agonizing conditions of enslavement. To create kinship during and after the Middle Passage is not a matter of ‘agency’ or an assertion of ‘humanity.’ I reject these framings as they seem facile in the face of the complexity of human violation. Slavery scholars have used ‘agency’ as a way to argue that Black people had humanity — this argument has long struck me as complicit with white supremacy, as it suggest that white slaveowners treated Black people so poorly because of an error or misrecognition. It suggests that they had fully realized the shared humanity of the enslaved, and therefore perpetrated unspeakable violence. The point, then, is not to assert that the enslaved were human. Instead, it is to grapple with the ways in which their humanity was used against them, and if, how, and when they pitted their lives and loves and joys and anguish against the terms used by their kidnappers to rationalize their dispossession.13

Creating kinship in these conditions is to refuse the structures of commodification that undergird not just racial slavery and human hierarchy, but indeed the edifice of colonial extraction that fueled early modern capitalism. Did every woman whose labor pains brought her to her knees, whether on board a slave ship or in a holding pen awaiting sale, see her birthing as an act of such profound disruption? No. Of course not. But did the birth of a child — either lost to sale or retained in defiance — steep those women in a space of love, loss, and anguish that categorically rejected the terms that slaveowners endeavored to render normative, rational, and humane? Did they claim connection in the face of commodification? Did they then produce a counter-narrative, rooted in affective claims to kinship from the very onset of transatlantic slavery? I think so. And I think that such a corporeal rejection constitutes an origin story for the Black Radical tradition. In these terms, the Black Radical tradition both builds upon and expands Robinson’s. It is one in which sovereignty is impossible to envision without kinship, and in which kinship is understood as antithetical to the marketplace’s assertion that Black people were fundamentally and successfully commercialized. This is a kinship that is rooted in the body, irrevocably formed in the crucible of a forced migration. It is a kinship that resulted in children left behind, empty arms filled with other women’s babies, families formed in adulthood. Cousins were chosen and sibling bonds crafted, at times so strong that they would preclude marriage with someone with whom the passage had been endured: survival turned them into kin so real that incest prohibitions took hold.14 It is a kinship infused with new meaning and rendered visible to slavery scholars who hold women’s experience of forced migration and enslavement at the center of their work.

Bibliography

Azurara, Gomes Eannes de, ‘The Discovery and Conquest of Guinea (1453),’ in Elizabeth Donnan (ed.), Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America, 1441–1700, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution, 1930), pp. 18–40, https://archive.org/stream/documentsillustr00donn/documentsillustr00donn_djvu.txt

Azurara, Gomes Eannes de, ‘Crónica dos Feitos da Guiné’, in Robert Edgar Conrad (trans. and ed.), Children of God’s Fire: A Documentary History of Black Slavery in Brazil (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994), pp. 5–11.

Bennett, Herman L., Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness, 1570–1640 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003).

Carretta, Vincent (ed.), Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the Eighteenth Century (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1996).

Desrochers Jr., Robert E., ‘Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704–1781’, The William and Mary Quarterly, 59 (2002), 623–64.

Eltis, David, The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Finley, Cheryl, ‘Schematics of Memory,’ Small Axe, 15 (2011), 96–99.

Galenson, David W., Traders, Planters, and Slaves: Market Behavior in Early English America (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Johnson, Walter, ‘To Remake the World: Slavery, Racial Capitalism, and Justice,’ Boston Review, 19 October 2016, https://bostonreview.net/race/walter-johnson-slavery-human-rights-racial-capitalism

Ligon, Richard, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (London: Humphrey Moseley, 1657), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A48447.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

Morgan, Jennifer L., ‘Accounting for “The Most Excruciating Torment”: Gender, Slavery, and Trans-Atlantic Passages’, History of the Present, 6 (2016), 184–207.

Newton, John, The Journal of a Slave Trader, 1750–1754 (London: Epworth Press, 1964).

Robinson, Cedric J., Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, www.slaveryimages.org

1 David Eltis, The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000); Jennifer L. Morgan, ‘Accounting for “The Most Excruciating Torment”: Gender, Slavery, and Trans-Atlantic Passages’, History of the Present, 6 (2016), 184–207.

2 Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (London: Humphrey Moseley, 1657), pp. 46–47, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A48447.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

3 Robert E. Desrochers Jr., ‘Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704–1781’, The William and Mary Quarterly, 59 (2002), 623–64.

4 Gomes Eannes de Azurara, ‘The Discovery and Conquest of Guinea (1453),’ in Elizabeth Donnan (ed.), Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America, 1441–1700, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution, 1930), pp. 18–40 (p.40), https://archive.org/stream/documentsillustr00donn/documentsillustr00donn_djvu.txt

5 PRO T70/16 f49, Steede and Gasciogne, Barbados, April 1683 cited in David W. Galenson, Traders, Planters, and Slaves: Market Behavior in Early English America (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 110–11; Voyage 15076, Delight (1683), www.slavevoyages.org

6 Sancho’s father — whether a man with whom she shared a life prior to capture or one with whom she forged a connection along the slave route — could not bear the conditions under which he found himself and committed suicide, leaving the baby to a slaveowner who risked the toddler’s life on another Atlantic crossing before delivering him to enslavement in England. ‘Ignatius Sancho,’ in Vincent Carretta (ed.), Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the Eighteenth Century (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1996), pp. 77–109 (p. 100).

7 Voyage of the James, 1675–76, in Donnan (ed.), Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade, vol. 1, pp. 206–09.

8 Gomes Eannes de Azurara, Crónica dos Feitos da Guiné, in Robert Edgar Conrad (trans. and ed.), Children of God’s Fire: A Documentary History of Black Slavery in Brazil (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994), pp. 5–11 (p. 10).

9 Cheryl Finley, ‘Schematics of Memory,’ Small Axe, 15 (2011), 96–99.

10 Image Reference JCB_01138-1. Slavery Images is compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library. Original source: Résumé du témoignage donné devant un comité de la chambre des communes de la Grande Bretagne et de l’Irelande, touchant la traite des negres (Geneva, 1814), fold-out plate, following title page in 4th pamphlet of vol. 15 of a collection with binder title ‘Melanges sur l’Amerique’ (Copy in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University).

11 Entry 31 January 1753 in John Newton, The Journal of a Slave Trader, 1750–1754 (London: Epworth Press, 1964).

12 Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), pp. 130–40.

13 Walter Johnson, ‘To Remake the World: Slavery, Racial Capitalism, and Justice,’ Boston Review, 19 October 2016, https://bostonreview.net/race/walter-johnson-slavery-human-rights-racial-capitalism

14 Herman L. Bennett, Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness, 1570–1640 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003).