28. Supershero Amrita Simla, Partitioned Once, Migrated Twice

© 2019 Sarah K. Khan, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0153.28

Introduction

I created an avatar, supershero, and alter-ego named Amrita Simla. Via my immigrant supershero, I retaliate against labels of exotic, submissive, or compliant women, stereotypes we encounter as South Asian Americans. As a Muslim, I combat the clichéd labels of abused and oppressed, and challenge one-dimensional readings of women and Islam. I authored the shape of Simla as a multifaceted global Pakistani-American, a super-fly woman. She embodies layered narratives derived from many cultural traditions and encounters. Seriously playful and playfully serious, she flies the world, bears witness, and makes the invisible visible, with camera and cleavage, a pair of glasses perched on her head, and wisps of grey. She is neither overly sexualized, nor completely covered. She represents most women, at neither end of the polemical spectrum. Instead, she is in the middle. And extraordinary in her ordinariness.

Amrita Simla Shero — Origin and Evolution

Fig. 27.1 Sarah K. Khan, ‘Amrita Simla B&W’, 2015. © Sarah K. Khan.

The presence of a brown supershero for public consumption is a form of resistance and strength. I created Amrita Simla to appeal to my community, as opposed to the fantasies or expectations of a white and/or male gaze. Troubled with the urgency of Black Lives Matter, indebted to the civil rights movement for my presence in this country, I needed to introduce another supershero, with fist raised, to the mix of Black, brown, LGBTQ s/heroes. On my terms, she appears first in my short film as a narrator, Bowing to No One — a non-poverty film about an indigenous Central Indian woman farmer, forager, and healer.1 Simla is a required addition to the ever-expanding US and South Asian visual culture. More Black and brown super-sheroes flying the sky equip young and old with a vision of how they have power to soar. I push for the space to imagine, and demand belonging. I insert myself and my creations, without apology.

The Shero Simla character emerged fully when I spent a year (2014–15) as a Fulbright Senior Research Scholar in India. I co-created her imagery with Sutanu Panigrahi, a graphic artist, painter, and designer based in Delhi. Amrita Simla’s story derives from narratives that are not Euro- or America-centric but pull from my own curated ancestral South Asian/Muslim cultural heritages. She soars to the songs of her protective Punjabi Jugni2 (female fireflies) whose social justice lights help her bear witness. The curled and flowing clouds she glides among are Persianized, like the miniature Mughal-Persian-inspired graphics she inhabits, and her nose is Half Mughal, Half Mowgli, à la Riz MC of the Swet Shop Boys.

Fig. 27.2 Sarah K. Khan, ‘Amrita Simla at Peace, Overlooking Her World’, 2015. © Sarah K. Khan.

My virtual version of Amrita is entitled ‘Amrita Partitioned Once, Migrated Twice’. It includes graphics based on my photography, archival family photographs, curated maps, and drawings. The layers shown represent one story, but Simla and her creator embody limitless strata and infinite terrains. The origin of her name, Amrita Simla, first: my father, born in Simla in 1928, grew up both in Simla and Amritsar (now located in modern-day India), with a brief stint in Old Delhi, before partition in 1947. In South Asia today, as in most parts of the world, a name signifies kinship, gender, religion, caste, class, status, geography, and much more. To stress my limitless strata and conceal other aspects, I chose a name that reveals location only; Amrita Simla is a northern South Asian shero. The name ‘Amrita,’ also invokes a healing nectar, amrit (in Sanskrit it means immortality, it is understood also as soma, the drink that confers immortality). Amrita is the healer and healed. Sometimes referred to as Sim Sim, her nickname means ‘sesame’ in Arabic. And in fact, the incantation that allows Ali Baba of the Arabian Nights3 to access the thieves’ treasure begins with ‘Open Sesame!’ iftah yā simsim (Arabic: مسمس اي حتفا). Shero Sim Sim not only suggests her connection to her Muslim sensibilities but also places herself in the exotic Arabian Nights. In this case, however, Sim Sim is the magical sesame. The way-opener, she is both the lock and the key. She controls who enters, remains, and leaves her world.

Fig. 27.2a Sarah K. Khan, ‘Arab Map of the World’, 2015, © Sarah K. Khan.

An Arab map of the world anchors Amrita’s creation story with histories from South Asia, the Muslim world, and its surrounding cultures.4 At the foundation lies a map of the world by Al-Sharif al-Idris (c. 1100–1165), a Muslim from Al-Andalus who worked for the Norman King Roger II. Islamic map-makers excelled at mapping the world, and his world map moors Amrita’s world. That I build this virtual collage on the foundations laid by an Arab-Muslim map-maker is not lost on me. I deliberately excluded one newer British colonial empire for an older hegemonic power, the Muslims of the past. A contradiction, and yet a different hook on which to hang some of Amrita’s history.

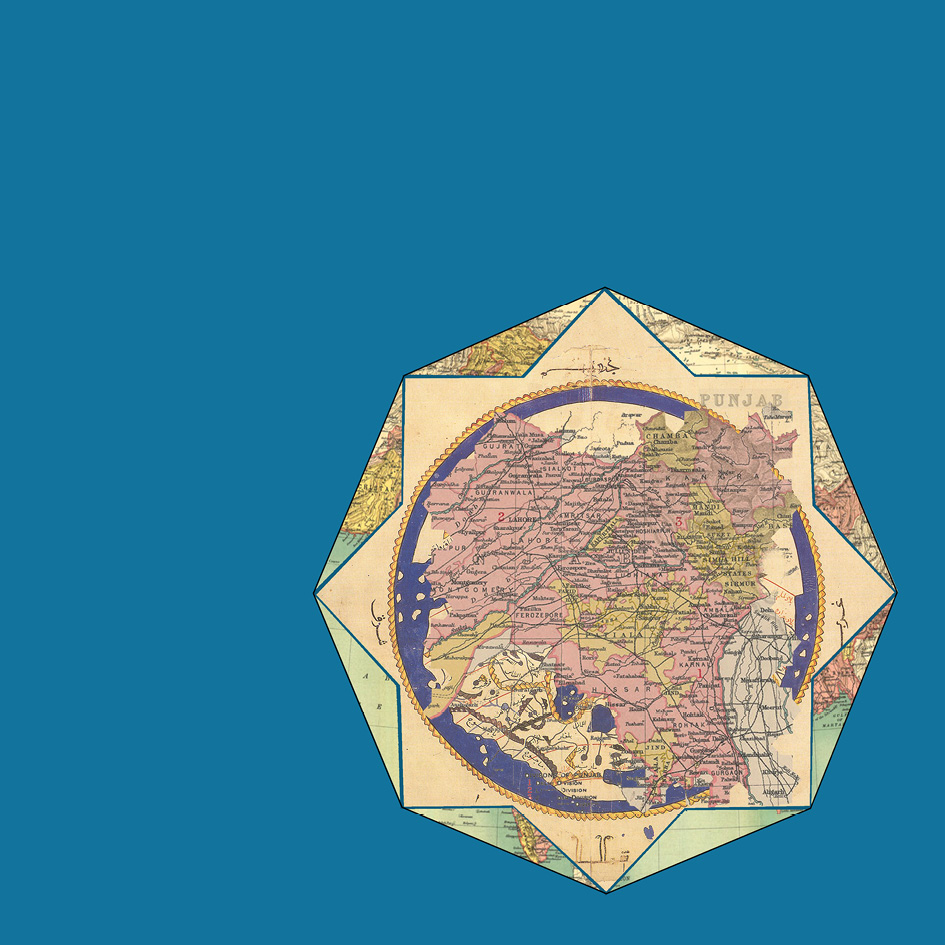

Fig. 27.2b Sarah K. Khan, ‘British Gazetteer Map of India Pre-Partition’, 2015. © Sarah K. Khan.

On the next stratum I placed a British Gazetteer map of northern South Asia from the early 1940s, before partition.5 The map reveals the territory that existed before imperial powers imposed borders in a colonialist frenzy that led to the deaths of millions in addition to the displacement and migration of more than six million people.6 7 By adding this layer, maybe I could elicit longer, deeper stories from my family, especially my mother and father, who lived through partition. A medical student (his own father was a Hakim (healer), on the side) in Amritsar at the time, my father went with his medical school professor and his fellow Sikh, Hindu, and Muslim peers to see the trains recently arrived from Lahore filled with the dead bodies of massacred Hindus in August 1947. Similar trains filled with Muslim bodies arrived in Lahore. ‘You will never know what it means to live under Hindu-dominated rule,’ he raises his voice towards those who suggest that maybe there never should have been a partition. The placement of the pre-partition map helps me conjure healing. If the map is not partitioned, reframed and torn, then places are still whole. If the map does not contain borders, then my and my father’s mind may wander a border-free universe. I will it to be that way by placing the map as another layer, another mooring in the collage. As the strata collect, a virtual collage unfolds. The patchwork layers are amuletic, known to me, and charged with import and prayer. They are hidden and revealed in pieces.

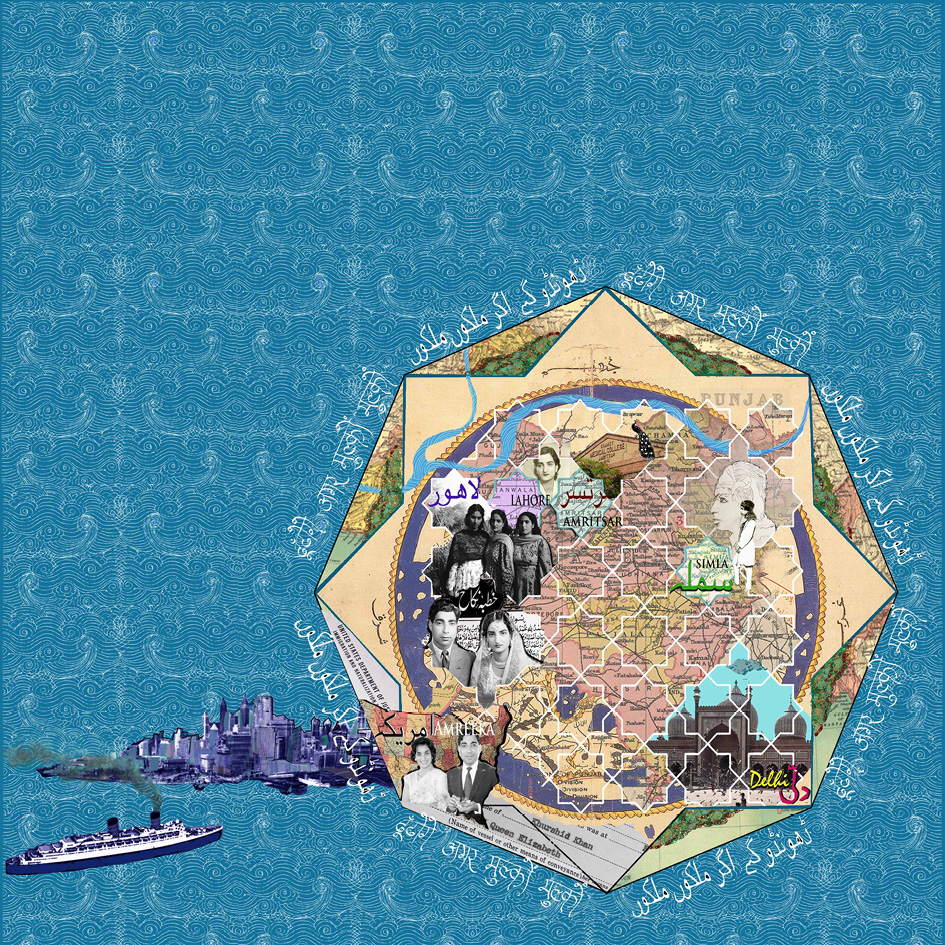

Fig. 27.2c Sarah K. Khan, ‘Amrita Simla with Archival Family Photos’, 2015. © Sarah K. Khan.

I added several more layers to ‘Amrita Partitioned Once, Migrated Twice’. The virtual collage expresses tangible places: my father dressed in costume for a school play in Simla as a boy; the view of the Jama’a Masjid in Old Delhi, close to where his family lived; and a photo of his medical school before partition in Amritsar. Bilqis, my mother, the Queen of Sheba, strikes her filmy Bollywood pose with her sisters in Lahore. And a Nikah Nama seals their Muslim marriage, followed by a journey to Amreeka on the Queen Mary. A final photo in the sequence is the young couple at a party, my father with the requisite 1950s drink in his hand, and my mother with her hair fashionably coiffed. They beamed black and white, bright.

Before Amrita enters the stage, her world is now encircled with Urdu and Devanagari scripts that repeats a couplet sung by Abida Parveen, a Pakistani singer, based on the poem by Shaad Azeemabadi (1846–1927). The refrain loosely translates to ‘If you find your nation, your nation… it is rare to find.’8 I interpret the song to mean, ‘If you find your place, your nation, your country, your peace, your love or lover… it is rare to find.’ Her song bathes me in longing, and her words convey what many migrants feel, a yearning. One is in a constant state of searching for one’s place in the physical and spirit worlds. A tugging at yourself, a continuous reminder exists that you are from somewhere else, belong nowhere, and yet belong everywhere. But you only kind of, sort of, belong.

The creation story nears completion. Airborne birds roam free without partitions and borders. Our family has no special ties to Ellis Island, where an earlier wave of immigrants arrived on Amreeka’s shores. We arrived after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was enacted in 1966. The sacrifices of the civil rights activists permitted the partitioned and migrated a second chance. And slowly, North American culture seeped into our souls. Just as much as Abida Parveen and her Sufi soul evoked a yearning, the Jackson 5 lit a fire in this five-year-old South-Asian-American girl. They helped me learn my ABCs and 123s on the Soul Train.

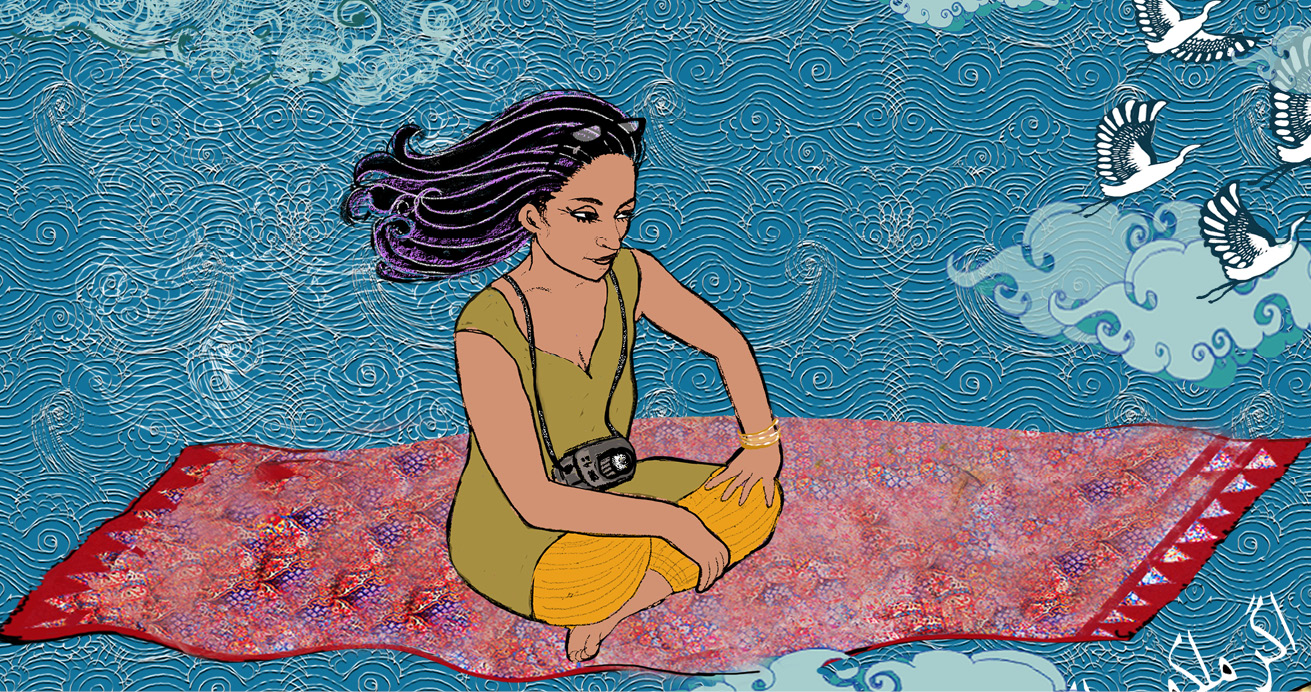

Fig. 27.2d ‘Amrita on Her Carpet’, 2015. © Sarah K. Khan.

Amrita appears on her intricately woven red magic flying carpet. She no longer considers herself half, as an immigrant’s kid, but double and overflowing with fullness. She hovers, looking down at a story of her created self, composed and unruffled. Dressed simply, neither draped with excess clothing nor scantily clad. She floats. Always with camera and cleavage. Her glasses balanced. Her strands of grey are her strength, knowledge and power. She documents. She films with permission. Though older, she is attractive to herself in her comfort, first and foremost. And she has jugni (female fireflies) that infuse her hair and light her way. Punjabi jugni singer-protectors recall those who originally sang songs to protest British colonization and exploitation at the turn of the nineteenth century around the time of the Queen’s Jubilee. In the twenty-first century they reappear to protect and propel their Shero Simla, always forward towards the light. (For a complete playlist that accompanies the un-layering of Amrita, and subsequent multimedia projects, see the footnote.9)

Developing Amrita Simla: Animated, Comic, Graphic

Upon completing my Fulbright in India, I returned to the USA. I read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ ‘The Case for Reparations’ in The Atlantic10 and Between the World and Me.11 And I learned about the Marvel Comics, Black Panther series he was authoring.12 As a child I read Archie’s, Richie Rich, The Peanut Gallery, and Dennis the Menace. I grew older, I stopped reading them. They did not include me. They did not reflect me. I turned away. This turning-away became a series of turnings-away from the multiple white eurocentric canons and epistemologies in traditional academic disciplines. I cobbled together my own education, filled with histories and stories and literatures that included me, or people closer to me. This included African-American culture, Arab history, South Asian, China, Brazil, and Nuyorican salsa culture.

The 2009 US inauguration, though freezing cold, signified a shift in my sense of place; a hopeful warmth enveloped me. Fast forward to Obama’s final years in office. For the first time, I viscerally felt that I too belonged in North America. Despite my differing political views on many issues with the administration, the presence of a Black man and a Black family in the White House gave me hope that I not only belonged here, but was also going to fight for that right through my art practice and social justice engagements.

At the same time the US elections loomed. I was disturbed by mass incarceration, an assault on immigrants, and the post-9/11 hunt for Muslims and Arabs in New York.13 I was researching my short film for the Migrant Kitchen Series, Surviving Surveillance, Catering to America, about the life of a Pakistani woman whose son was surveilled and entrapped by the NYPD. Shahina Parveen survived by catering.14 A more sophisticated version of COINTELPRO15 now targeted Muslims and Arabs, in addition to Black and brown bodies. Shahina and her family were caught in our post 9/11 quagmire. Amid these events, I learned of G. Willow Wilson’s Marvel Comic Star Kamala Khan,16 a Muslim Pakistani-American supershero. And I wanted more nuanced Black and brown s/heroes, in all their gradations, differences, and layers of complexity. I sought to tip the publishing and media worlds towards the possibility of complex representations. With the recent — at least on TED — acknowledgment of the need for more diverse chronicles,17 Wilson and Coates’ contributions of brown and Black narratives at Marvel Comics propelled me to introduce Amrita to broader audiences.18 Amrita Simla now needed to emerge more fully in multiple forms — animation, comic and graphic representations (which are currently in progress), in addition to being the narrator of the Indian women farmers’ short films.

Other Works

The ethos of Amrita inspires my other bodies of popular and public work. The additional works deal, directly or indirectly, with women and migration, and farming and cooking as knowledge-based practices. Past and on-going projects include: Farmers of Color in Southern USA; Indian Women Farmers short film series, narrated by Shero Simla;19 The Migrant Kitchens Series in Queens NY and Fez Morocco;20 and The In/Visible Photography Series.21 These works are transdisciplinary, involving film, audio, photography, graphic art, maps, charts, and texts.22 Most are available in popular media outlets, and engage the themes of women, agency, migration and social justice.

Envoi

I aim to defy erasure, to stitch permanently my presence along with other marginalized people into the fabric of local and global cultures. In a world that dismantles its free edges, erects borders and walls, guts its core values, and strips away basic human rights, I resist omission through popular media and socially engaged art. I offer a human and humane glimpse of singular, often female, voices. By the creative transdisciplinary documentation of women and the marginalized, I challenge exclusion. The fight against deletion, past, present, and future, anchors my multimedia production. And it propels me further to reimagine new and revive lost narratives: local and global s/heroes who dreamed, created, conquered, loved, played, and lived forever in the shadows and on the sidelines, dismissed to the margins. No more.

Bibliography

Adichie, Chimananda, ‘The Danger of a Single Story’, TED, https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story/transcript?language=en

Alexander, Michelle, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010).

al-Idris, Al-Sharif, Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq, the ‘book of pleasant journeys into faraway lands’, or ‘Book of Roger’, Tabula Rogeriana, by permission of The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, http://bodley30.bodley.ox.ac.uk:8180/luna/servlet/detail/ODLodl~23~23~126595~142784:WorldMap?qvq=w4s:/what/MS.%20Pococke%20375;lc:ODLodl~29~29,ODLodl~7~7,ODLodl~6~6,ODLodl~14~14,ODLodl~8~8,ODLodl~23~23,ODLodl~1~1,ODLodl~24~24&mi=0&trs=70

Apuzzo, Matt and Adam Goldman, Enemies Within: Inside the NYPD’s Secret Spying Unit and Bin Laden’s Final Plot Against America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013).

Bartholomew, J. G., The Indian Empire. Imperial Gazetteer of India. New Edition, Published Under the Authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907–1909).

Butalia, Urvashi, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000).

Coates, Ta Nehisi, Black Panther, Marvel Comics, https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/ta-nehisi-coates-new-comic-black-hell

Coates, Ta-Nehisi, ‘The Case for Reparations’, The Atlantic, June 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

Coates, Ta-Nehisi, Between the World and Me (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2015).

Irwin, Robert (ed.), The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1,001 Nights, vols. 1–3 (London: Penguin UK, 2010).

Khan, Sarah K., ‘Collateral Damage’, OpenCityMag, 25 April 2017, http://opencitymag.aaww.org/collateral-damage/

Khan, Sarah K., ‘Bowing to No One, Trailer,’ Vimeo Video, 4 January 2016, https://vimeo.com/150720245

Mishra, Pankaj, ‘Exit Wounds: The Legacy of Indian Partition’, New Yorker, 16 August 2007, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/08/13/exit-wounds

New York University, ‘“In/Visible: Portraits of Farmers and Spice Porters, India” Photography Exhibition by Sarah K. Khan to Debut at NYU’s Kimmel Windows Galleries, June 7–September 7, 2018’, https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2018/may/-in-visible--portraits-of-farmers-and-spice-porters--india--phot.html

Parveen, Abida, ‘Dhoondo Ge Agar Mulkon’, posted as ‘Dhoondo Ge Agar Mulkon | Abida Parveen Songs | Abida Parveen Meri Pasand Vol – 2’ by EMI Pakistan, YouTube, 21 September 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48c7H-1BenM

Pennington, Latonya, ’15 Muslim Characters in Comics You Should Know’, CBR.com, 3 February 2017, http://www.cbr.com/muslim-comic-book-characters-you-should-know/

Rankine, Claudia, Citizen: An American Lyric (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2014).

Sabarwal, Umang, ‘Jugni Songs and the Traveling Sparks of Freedom,’ Agents of Ishq, 15 August 2017, http://agentsofishq.com/jugni/

Salian, Priti, ‘The Exhibition Highlighting the Power of Migrant Cooks’, The National, 6 December 2018, https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/food/the-exhibition-highlighting-the-power-of-migrant-cooks-1.799516

Stevenson, Bryan, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2014).

Tolentino, Jia, ‘The Writer Behind a Muslim Marvel Superhero on Her Faith in Comics’, New Yorker, 29 April 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/g-willow-wilsons-american-heroes

Weldon, Glen, ‘Beyond the Pale (Male): Marvel, Diversity and a Changing Comics Readership’, Weekend Edition Saturday, 8 April 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/04/08/523044892/beyond-the-pale-male-marvel-diversity-and-a-changing-comics-readership

1 ‘Bowing to No One, Trailer,’ Vimeo Video. ‘Bowing to No One’, the first film in the series, is about Satyavati, an indigenous woman farmer from Central India, who recounts her struggles to live sustainably on her land and forests. Posted by Sarah K. Khan, 4 January 2016, https://vimeo.com/150720245

2 Umang Sabarwal, ‘Jugni Songs and the Traveling Sparks of Freedom,’ Agents of Ishq, 15 August 2017, http://agentsofishq.com/jugni/

3 Robert Irwin (ed.), The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1,001 Nights, vols. 1–3 (London: Penguin UK, 2010).

4 Al-Sharif al-Idris (c. 1100–1165), Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq. The ‘book of pleasant journeys into faraway lands’, or ‘Book of Roger’, Tabula Rogeriana. A sixteenth-century (1553 AD) manuscript of al-Idrisi’s description of the world composed in 1152, this manuscript contains the complete text of al-Idrisi’s medieval Arabic geography, describing the known world from the equator to the latitude of the Baltic Sea, and from the Atlantic to Siberia. By permission of The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, http://bodley30.bodley.ox.ac.uk:8180/luna/servlet/detail/ODLodl~23~23~126595~142784:WorldMap?qvq=w4s:/what/MS.%20Pococke%20375;lc:ODLodl~29~29,ODLodl~7~7,ODLodl~6~6,ODLodl~14~14,ODLodl~8~8,ODLodl~23~23,ODLodl~1~1,ODLodl~24~24&mi=0&trs=70

5 J. G. Bartholomew, The Indian Empire. Imperial Gazetteer of India. New Edition, Published Under the Authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907–1909): a map of Northern South Asia, before partition, British Gazetteer, http://dsal.uchicago.edu/maps/gazetteer/images/gazetteer_frontcover.jpg

6 Urvashi Butalia, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000).

7 Pankaj Mishra, ‘Exit Wounds: The Legacy of Indian Partition’, The New Yorker, 16 August 2007, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/08/13/exit-wounds

8 Abida Parveen, ‘Dhoondo Ge Agar Mulkon’, posted as ‘Dhoondo Ge Agar Mulkon | Abida Parveen Songs | Abida Parveen Meri Pasand Vol – 2’ by EMI Pakistan, YouTube, 21 September 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48c7H-1BenM. Translation: http://gurmeet.net/poetry/dhoondoge-agar-mulkon-mulkon/

9 Essay Playlist:

- Abida Parveen sings ‘Dhoondon Ge agar mulkon mulkon…’ Live performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UKGB-Rhkzho

- Jackson 5, ABC, Jackson5 ABC Album, 1970.

- Riz MC of The Swet Shop Boys, Half Moghul, Half Mowgli, Cashmere Album, 2015.

- Jugni: http://agentsofishq.com/jugni/

- Vijay Iyer, Human Nature, Solo Album, 2010

- John Santos, Abuela, La Mar Album, 2002

- Hakam Khan, Rajasthani Folk Song about the agricultural cycle, SKKhan’s audio/video field recordings 2014

- Audio field recordings of spice porters working in Khari Baoli, Asia’s largest spice market, Old Delhi 2014–15

- Audio recording Shabnam Virmani, singing about Sassi Puunun, a Sindhi Folk legend about separation from the beloved. New Delhi 2015.

10 Ta-Nehisi Coates, ‘The Case for Reparations’, The Atlantic, June 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

11 Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2015).

12 Ta Nehisi Coates, Black Panther, Marvel Comics, https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/ta-nehisi-coates-new-comic-black-hell

13 See Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010); Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2014); Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2014); Matt Apuzzo and Adam Goldman, Enemies Within: Inside the NYPD’s Secret Spying Unit and Bin Laden’s Final Plot Against America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013).

14 The short film has been an official selection at the Korean American Film Festival of New York 2017; TASVEER South Asian Film Festival Seattle, Washington, 2018; and screened at Museum of the Moving Image and Queens Museum in 2017.

15 COINTELPRO, https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro

16 Kamala Khan, Marvel Comics; Jia Tolentino, ‘The Writer Behind a Muslim Marvel Superhero on Her Faith in Comics’, New Yorker, 29 April 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/g-willow-wilsons-american-heroes; Latonya Pennington, ’15 Muslim Characters in Comics You Should Know’, CBR.com, 3 February 2017, http://www.cbr.com/muslim-comic-book-characters-you-should-know/

17 Chimananda Adichie, ‘The Danger of a Single Story’, TED, https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story/transcript?language=en

18 Glen Weldon, ‘Beyond the Pale (Male): Marvel, Diversity and a Changing Comics Readership’, Weekend Edition Saturday, 8 April 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/04/08/523044892/beyond-the-pale-male-marvel-diversity-and-a-changing-comics-readership

19 ‘Bowing to No One, Trailer,’ https://vimeo.com/150720245.

20 Migrant Kitchens Series including articles, photography, detailed data-driven maps: Queens Migrant Kitchen Project Culinary Backstreets: https://culinarybackstreets.com/category/projects-category/queens-project-category/ and Asian American Writers’ Workshop: Sarah K. Khan, ‘Collateral Damage’, OpenCityMag, 25 April 2017, http://opencitymag.aaww.org/collateral-damage/

21 New York University, ‘“In/Visible: Portraits of Farmers and Spice Porters, India” Photography Exhibition by Sarah K. Khan to Debut at NYU’s Kimmel Windows Galleries, June 7–September 7, 2018’, https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2018/may/-in-visible--portraits-of-farmers-and-spice-porters--india--phot.html

22 Priti Salian, ‘The Exhibition Highlighting the Power of Migrant Cooks’, The National, 6 December 2018, https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/food/the-exhibition-highlighting-the-power-of-migrant-cooks-1.799516