Part Eight Emotional Cartography: Tracing the Personal

36. The Ones Who Leave… the Ones Who Are Left: Guyanese Migration Story

© 2019 Grace Aneiza Ali, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0153.36

There are two spectrums of the migration arc: the ones who leave and the ones who are left. The act of migration is an act of reciprocity — to leave a place we recognise that we must leave others behind. Too often though, those who are leaving eclipse the narratives of the ones who are left behind. I find myself often caught in this liminal space between those who leave and those who (must) remain because for many years this was my story, and for many years before that, it was my mother’s story.

In 1995, my family migrated from Guyana to the United States. We became part of what seemed like a mythical diaspora. Over one million Guyanese citizens now live in global metropolises like New York City (where they are the fifth largest immigrant group),1 London, and Toronto, while the country itself has a population of around 760,000. In other words, my homeland is one where more people live outside its borders than within it. In 2015, Guyana celebrated its 50th anniversary of independence from the British. The last five decades, however, have been defined by an extraordinary exodus of its citizens. In fact, this small country has one of the world’s highest out-migration rates.2

Making the journey with us when we left were a handful of photographs chronicling our life. Owning photographs was an act of privilege; they stood among our most valuable possessions. There were no negatives, no jpegs, no double copies, just the originals. Decades later, these photographs serve as a tangible connection to a homeland left behind. Many of them are taken at Guyana’s airport during the 1980s and 1990s when we often bade farewell to yet another family member leaving. Movement and transition were the constants in our lives. Airports became sites for family reunions. Before I nervously boarded my first plane at fourteen years old, a one-way flight bound for New York’s JFK airport, I had long resented planes as the violent machines that fragmented families. Before my mother boarded that same flight at thirty-nine years old with her three children in tow, she had in the years prior, witnessed her brothers and sisters all leave Guyana one by one. By nineteen years old, a cycle of poverty and the final straw, the loss of both of her parents within a few short years of each other, ushered in a series of constant departures. Beginning in the 1970s, her six siblings joined the mass exodus of Guyanese leaving Guyana. They first left for neighboring Caribbean islands, then later Canada and the United States, through student visas, work visas, marriage visas — whatever it took. During the three decades that my mother spent waiting for our family’s visas and papers to be vetted by two governments, Guyana and the United States, she watched the ones she loved the most leave her country and leave her, multiple times over.

Fig. 36.1 My mother Ingrid (third row, center) poses with her siblings and extended family at Timehri International Airport, Guyana in the mid-1970s, as she bade farewell to a sister who was leaving for Barbados. © Ali-Persaud family collection. Courtesy of Grace Aneiza Ali, CC BY 4.0.

Migration is the defining movement of our time — for both the ones who leave and the ones who are left. Few of us remain untouched by its sweeping narrative. Guyanese people have long known this as it has been the single most important narrative of our country. A perfect storm of post-colonial crises — entrenched poverty, political corruption, repressive government regimes, racial violence, lack of education, unemployment, economic depression, and worse of them all, a withering away of hope for our country — are among the reasons why we leave Guyana.

The BBC Radio series ‘Neither Here Nor There’ dedicated one of its episodes to the presence of the Guyanese community in the United States, examining how their American experience has impacted their identities.3 Sharing that more Guyanese now live in the Tri-State Area (New York City, New Jersey, and Connecticut) than in Guyana itself, host David Dabydeen, the Guyanese-born writer who also left his homeland, remarked that Guyana ‘is a disappearing nation’ that has ‘to an unrivalled degree, exported its people’ over the last five decades. Dominque Hunter, an emerging artist living in and working in Guyana, echoes a similar sentiment, sharing with me that from a very young age the Guyanese citizen is indoctrinated with an urgent call for departure. ‘Our greatest aspiration should be to leave,’ she says, ‘There is an expectation once you have reached a certain age: pack what you can and leave’.4 What a spectacular thing for any citizen of any place to grapple with — to be, from birth, dispossessed of one’s own land.

Perhaps if there is a bright side to this culture of departure is the centrality of women. The red thread woven throughout Guyana’s migration stories is the driving force of Guyanese women. Prior to the 1960s, it was traditionally men from the Anglophone Caribbean who were the first in their families to migrate. In 1960, that dominance began to shift as the United States, United Kingdom and Canada looked to the Caribbean as a source for blue collar, healthcare and domestic workers. Since that time, it has been Caribbean women who have led the movement from their homeland to new lands. In her essay, ‘Of Islands and Other Mothers,’ examining the emergence of Guyanese as the fifth largest immigrant group in New York City, Guyanese-American writer Gaiutra Bahadur centers women:

Caribbean women participate in the labor force at higher rates than women from other [immigrant] groups. On average, they earn less than their countrymen and they may be less visible, because they work inside homes, as nannies or housekeepers or health care aides. For many [Caribbean] countries, the migration out was led by women, who then sponsored family members, including husbands and sons, to come to America.5

This dominance is certainly the case in New York where Guyanese women outnumber men — the male/female ratio is 79 per 100 among Guyanese immigrants.6 Caribbean women’s migration also opened up a new kind of agency for women that had been previously held by men. Beginning in the 1960s, Caribbean women were increasingly regarded as ‘principal aliens’ — granting them the ability to begin the application process to sponsor their family members. In tandem, Guyanese women, after becoming legal residents or naturalized citizens, aggressively took on the charge of sponsoring their family members to join them in their new countries.7

The photographic medium has historically played a critical, and often problematic, role in how as a society we see and do not see the Black and brown bodies that cross international borders. That precious 1970s photograph of my young mother flanked by her family at Guyana’s airport became an important catalyst for my curatorial practice as I have focused on the relationship and responsibility that photography bears in representing our migration narratives. Each day, more women than ever from all over this world get on planes and boats and ships and makeshift rafts, while many simply walk, to cross borders.8 Are they merely fleeing? Or are they embarking on an incredibly brave and heroic journey to be in charge of their own destiny, to believe in the notion that they are free to move about the world? That 1970s photograph is a reminder for me of the grit it took for my mother to enact her own agency.

My investment in the multiple and complicated stories embedded in that one image has led me to the brilliant work of the following four women of Guyanese heritage with whom I have had the privilege to collaborate in the exhibitions I have curated — Keisha Scarville, Christie Neptune, Erika DeFreitas, and Khadija Benn. Their work has moved me in deeply personal ways for its intimate and thoughtful use of photography as a medium to tell Guyanese women’s stories. These four artists utilize portraiture in their artistic practices as medium, object, archival language and documentary reporting, to explore the nuanced migration experiences of Guyanese women. To further deepen this relationship between photography and migration, these four artists embed in their practices innovative use of archival images, mine their family albums, and explicate private letters from their personal archives. The journeys of these treasured objects across the Atlantic Ocean leads us to meditate on what shifts occur in the migration narrative when photographs and family archives transcend geographic borders. Through their engagement with these images, the artists unpack global realities of migration, tease out symbols of decay and loss, and avoid trappings of nostalgia by envisioning avenues out of displacement and dislocation. And equally compellingly, their work speaks to who and what gets left, what survives and what is mourned, both the tangible and intangible things, in acts of migration.

Scarville, DeFreitas, Neptune and Benn are part of a younger generation of women of Guyanese heritage who reflect the contemporary reality of the Guyanese citizen — women living in Guyana, as well as those living in the country’s largest diasporic nodes, New York City and Toronto. Some of them return to Guyana often, and some rarely. Yet, being the daughters of Guyanese mothers remains at the core of their identities. In an essay on the literature of Caribbean women writers Paule Marshall and Jamaica Kincaid, literary scholar Kattian Barnwell threads the connection between the phrases ‘motherlands’ and ‘other-lands’. She writes:

Motherland may be variously defined as place of birth, ‘land’ or home of the mother, the site of the self. Conversely, other-land refers to the site where each character experiences alienation and ‘othering,’ the place of exile.9

Scarville, DeFreitas, and Neptune directly invoke the relationship between mothers and daughters in their work. They engage the tensions between the place of birth and the space of othering through the voyages undertaken by their mothers who were born in Guyana, and themselves as daughters, who were born in the United States and Canada. Benn, who is based in Guyana, occupies the opposite end of the migration arc, documenting the Amerindian mothers and grandmothers living in Guyana, who after witnessing their families fractured by migration, bear the burden to keep those fragile bonds connected. What these four artists have in common is that in turning to portraiture to tell the narratives of Guyanese women’s migration, they each explore the issue I am deeply concerned with — the toll migration enacts on our families.

Keisha Scarville

Fig. 36.2 Keisha Scarville, ‘Untitled #1’, from the series ‘Mama’s Clothes’, 2015. © Keisha Scarville, CC BY 4.0.

Born in New York to a Guyanese father and mother, the artist Keisha Scarville spent her childhood raised in a Brooklyn community where her parents migrated and settled. In the 1960s, during a notorious politically volatile decade that saw Guyana gain its independence from the British, Scarville’s mother found her way to New York where she took on new roles: an immigrant in the United States, a young Black woman witnessing America’s civil rights era, a wife and mother. Essentially, she left one volatile country for another. In those early years, she returned to Guyana often, taking a young Scarville back with her. However, as time passed, those visits became less frequent and Guyana lived mostly as a mythical motherland for the artist. Scarville writes about the dissonance her Guyanese-born mother experienced as she tried to reconcile life as an immigrant in the United States:

Though my mother chose to migrate to the United States, she maintained a connection to the land of her birth, firmly planting one foot under a tamarind tree in Buxton and the other, rooted on the rooftop of an apartment building in Flatbush, Brooklyn. In recounting her experiences when she arrived in the United States, she often discussed the first sensation of real cold, the strange taste of American chicken, and overcoming the embedded alienation of this place.10

In 2015, the artist’s mother passed away. Scarville became a daughter who had not only lost a mother, but also her deepest and most tangible connection to her mother’s homeland and her ancestral home. While grappling with this loss, the artist began to work on ‘Mama’s Clothes’ (2015), a collection of self-portraits photographed in her mother’s place of birth, Buxton (Guyana) and her neighborhood in Flatbush, Brooklyn (Guyana). Scarville says:

The death of my mother left me with a sense of displacement and an internal fracturing. I started to realize that an element I regarded as home — my mother’s body — was now missing. In her place were all that she accumulated as an American. My mother’s closets overflowed with bright colors, strong prints, and long flowing fabrics. When I was a little girl, I would often play dress up in my mother’s clothes and imagine the day I would fill her dresses and assert my body as a woman.11

Fig. 36.3 Keisha Scarville, ‘Untitled #5’, from the series ‘Mama’s Clothes’, 2016. © Keisha Scarville, CC BY 4.0.

Scarville drapes and layers her body in her mother’s clothing, as well as fashioning masks and veils out of them to cover her face and head. It is a face often obscured. In submerging her body within her mother’s clothes, Scarville marries both time and space — two generations, two homelands, and the complexities in between.

The insertion of her body in the photograph simultaneously speaks to Scarville’s role as both subject and performer. Dressed in her ‘mama’s clothes’ her body roams between the lush, organic landscapes of Buxton and Brooklyn, symbolically performing the act of migration her mother once embarked on. In ‘Mama’s Clothes’, migration and death are inextricably linked. Scarville notes: ‘I wanted to ease the anxiety of separation by conjuring her presence within the photographic realm. I allowed the assemblage of clothes to drip off my body as though it were a residual, surrogate skin’.12

Erika DeFreitas

Fig. 36.4 Erika DeFreitas’s grandmother Angela DeFreitas pictured in British Guiana with a wedding cake she made and decorated, ca. late 1960s. © DeFreitas Family Collection, Courtesy of Erika Defreitas, CC BY 4.0.

While Scarville mines the relationship with her mother, the artist Erika DeFreitas weaves together the relationships between her grandmother to her mother to herself. The practice of the Toronto-based artist is steeped in process, gesture, performance, and documentation. DeFreitas’s grandmother sold cakes out of a humble home in Newton, British Guiana in the late 1950s. She also taught classes in cake décor to neighborhood women, reflecting the craft as one of building community. DeFreitas’s grandmother never left Guyana, but her creative practice as a baker transcended its borders. She passed down the practice to DeFreitas’s mother who migrated to Canada in 1970, and in turn, taught the Canadian-born artist the intricacies of icing cakes. It is this sacred act of passing on a closely held family craft through three generations of DeFreitas women, and across two continents, which forms DeFreitas’s portraiture series titled ‘The Impossible Speech Act’ (2007).

Fig. 36.5 Erika DeFreitas, ‘The Impossible Speech Act’, 2007. © Erika DeFreitas, CC BY 4.0.

In this work (Fig. 5), rooted in maternal histories, DeFreitas’s mother is both subject and collaborator (the artist’s mother is pictured on the left, the artist is on the right). To produce ‘The Impossible Speech Act’, DeFreitas generously mined her family archives — albums and letters written between Guyana and Canada — and drew on the oral teachings of her grandmother. Together, mother and daughter took turns in a series of documented performative actions, both poetic and playful, to hand-fashion face masks out of green, yellow, and purple icing. From start to finish, the photographic series slowly unveils the meticulous detail, labor, time, and artistry embedded in the process of masking a bare face with these sculptural objects of flowers and leaves. The diptych featured here is the final portrait in the process.

The artist’s use of icing as material and process is symbolic. She notes, ‘historically icing was created with two purposes: to be decorative and to preserve’.13 However, DeFreitas’s chosen symbol of preservation becomes one of irony. Like the masks made of her mother’s clothing in Scarville’s ‘Mama’s Clothes’, the icing masks in DeFreitas’s work inevitably lead to an absence of the faces, their complete erasure. And, as the fragile material that it is, the icing itself disappears. ‘The masks did not become a substitute object in each of our image,’ says DeFreitas, ‘they melted from the heat emitted from our bodies, the flowers and leaves eroding, sliding slowly down our faces […] a reminder of the persistence of impermanence.’14 The work leaves us to ponder the question: Even when we commit to preserving a homeland’s memories, rites and traditions, how do we navigate the inevitable loss that pervades? DeFreitas’s ‘The Impossible Speech Act’ and Scarville’s ‘Mama’s Clothes’ are poignant examples of how, as daughters of Guyana, we constantly reach to our mothers and grandmothers as collaborators in our art — as we do in our lives.

Christie Neptune

Fig. 36.6 Christie Neptune, Memories from Yonder (2015). © Christie Neptune, CC BY 4.0.

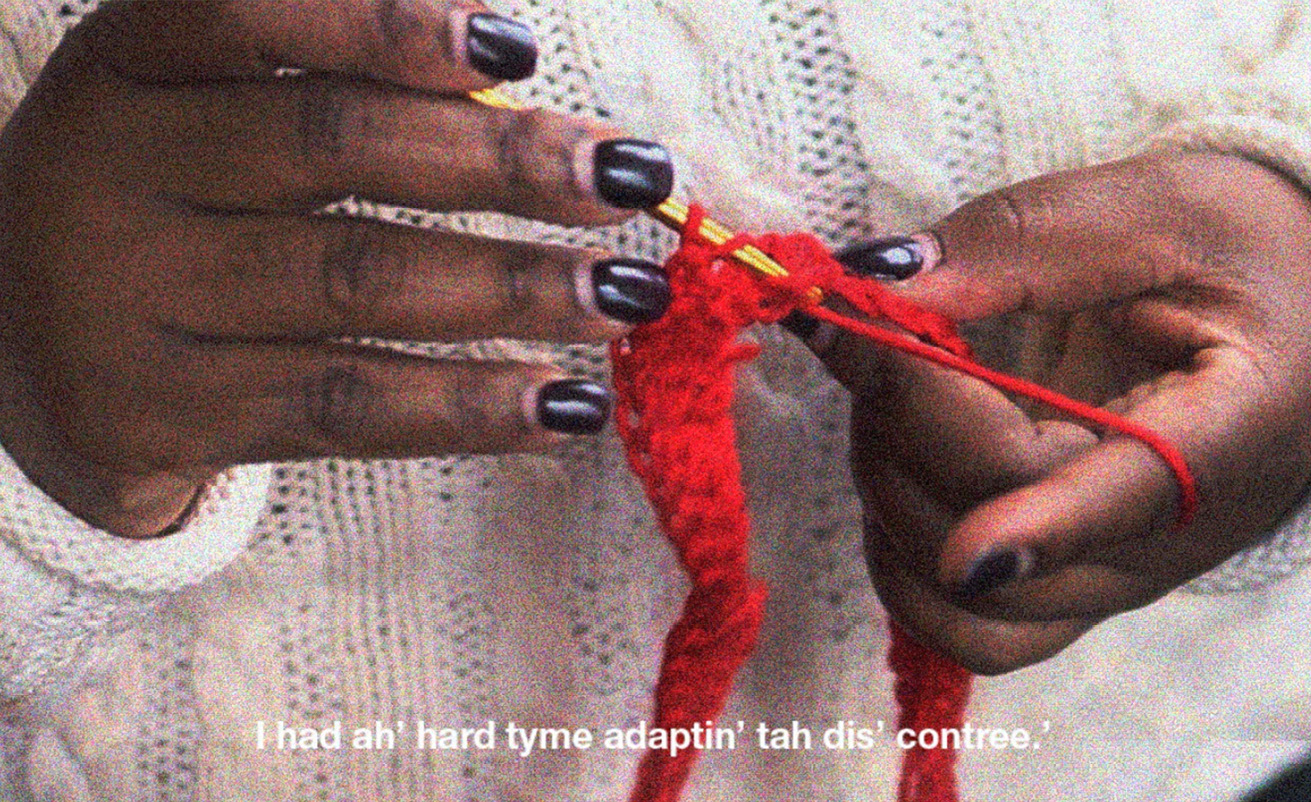

In this deeply personal and autobiographical work, American-born artist Christie Neptune mines childhood memories of her mother, a Guyanese immigrant in New York, and her love of crocheting — a craft popular among Guyanese women and passed down through generations. Like DeFreitas’s sacred act of passing on a closely held family craft between generations of Guyanese women, so too does Neptune. She notes the cultural importance of the craft:

The art of crocheting is a popular recreational activity amongst Guyanese women. The act serves as a prophetic mode of maintaining home and family. On the eve of new life, the women crochet blankets for the burgeoning mother; pillows and table runners for wives to be; and hats, scarves and socks for the winter. For most, crocheting is a way of life; an intergenerational activity woven into a myriad of traditions. My great grandmother taught the art of crocheting to her daughters; and my grandmother taught it to my mother.15

For Neptune, the art of crocheting becomes a metaphor for the necessary acts of unfurling a life in a past land to construct a new life in a new land. Invoking her own subjectivity as a first-generation Guyanese-American, Neptune presents visual and textual narratives from a conversation with Ebora Calder (b. 1925, Georgetown, Guyana), a Guyanese immigrant and elder, who like the artist’s mother, migrated to New York in the late 1950s. Calder represents a generation of Guyanese women who in the past sixty years have been part of the mass migration from Guyana to New York City. In the 1950s and into the early 1970s, Guyanese began migrating to America in greater numbers than ever before. At the same time the United States was in the midst of a nursing shortage. This need for nurses and other roles in the health care industry, one traditionally dominated by women, propelled more Guyanese women to migrate to the United States to take on those jobs. Underpaid or often paid under the table, Guyanese women were also often steeped in an invisible workforce as private household workers — nannies, housekeepers, and home care aides.16 This is Ebora Calder’s story, a woman who upon arriving in New York, worked as a home care aide until her retirement.

Fig. 36.7 Christie Neptune, video stills from Memories from Yonder (2015). © Christie Neptune, CC BY 4.0.

In the diptych and video still pictured in Figures 6 and 7 respectively, Neptune relies on two portrait photographs of Calder, taken in the Brooklyn Gardens Senior Center, where she now lives. The images have been rendered distorted, obscured, and mirrored with text captioning Calder’s words transcribed in both American English and Guyanese Patois. In both photograph and video, Calder is depicted in the slow, methodical, rhythmic act of crocheting a red bundle of yarn. The amorphous object she is making is unknown. ‘The gesture serves as a symbolic weaving of the two cultural spheres,’ states Neptune, ‘to reconcile the surmounting pressures of maintaining tradition whilst immersed in an Americanized culture’.17

Khadija Benn

Fig. 36.8 Anastacia Winters (b. 1947), lives in Lethem, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo (Region Nine), Guyana. Khadija Benn, Anastacia Winters from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017. © Khadija Benn, CC BY 4.0.

Based in Guyana, Khadija Benn’s training as a cartographer and her work as a geospatial analyst producing maps for the country’s remote Amazon regions, informs much of her photography practice and leads her across the country to places where most Guyanese rarely have access to or ever see in their lifetimes. Guyana’s first peoples, the Amerindians, have called these regions home since the eighteenth century. In tandem, Benn’s photography practice confronts the underlying histories that have created these complex spaces and aims to counter the contemporary framing of them as exotic. Relying on her intimate knowledge of these regions and the relationships she’s nurtured over the years with the families who live there, Benn’s documentary portraiture series, ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’ (2017) features stunning black and white portraits of elder Amerindian women who have called these communities home since the 1930s. These are the faces of Amerindian women the world rarely sees. Benn notes:

The narratives of those who choose not to migrate are seldom explored. This rings especially true for Guyana’s indigenous peoples. Many have witnessed their loved ones, particularly their children and grandchildren, leave for neighboring Venezuela and Brazil, or the Caribbean islands, the United States and Canada. Yet, they often remain.18

Fig. 36.9 Mickilina Simon (b. 1938), Tabatinga, Lethem, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo (Region Nine), Guyana. Khadija Benn, Mickilina Simon from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017. © Khadija Benn, CC BY 4.0.

However, as Benn’s lens reveal, these are not portraits of invisibility. These elder women have witnessed Guyana evolve from a colonized British territory, to an independent state, to a nation struggling to carve out its identity on the world stage, to a country now drained by its citizens departing. They have also been the ones most impacted by serious economic downturns over the past decades where the decline of bauxite mining coupled with little access to education beyond primary school and lack of employment have left these communities with few or no choices to thrive. And so, many do the only thing they can do — they leave. Benn writes:

As I spoke with these women, they affectionately recalled family members long gone abroad. Our conversations revealed their unique perceptions of time and space — the length of time gone by since their loved ones migrated was immaterial. Many also did not perceive relatives living in the neighboring countries, such as Brazil and Venezuela, as having settled ‘abroad.’ Amerindians have traditionally considered these international borders as fluid.19

While migration swirls around them, while their children go back and forth between Guyana and their newfound lands, many of these women have never left Guyana, some have never left the villages they were born in, and some have no desire to leave.

For the millions of us who have left one country for another fueled by choice or trauma, sustaining those fragile threads to a homeland is a process at once fraught, disruptive, and ever evolving. We also know that when we have left others behind in places that are beautiful, yet materially impoverished like my Guyana, we have a tremendous responsibility to the ones who are left. These four artists remind us how critical it is that we hear their stories.

Bibliography

‘A Disappearing Nation’, Neither There Nor Here, BBC Radio 4, 28 February 2017, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08gmtx1

Bahadur, Gaiutra, ‘Of Islands and Other Mothers’, in Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Shapiro (eds.), Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), pp. 77–85.

Barnwell, Kattian, ‘Motherlands and Other Lands: Home and Exile in Jamaica Kincaid’s “Lucy” and Paule Marshall’s “Praisesong for the Widow”’, Caribbean Studies, 27 (1994), 451–54.

Benn, Khadija, ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’ (2017).

DeFreitas, Erika, ‘The Impossible Speech Act’ (2007), exhibited in ‘Un |Fixed Homeland’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali, at Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art, Newark, New Jersey (17 July–23 September 2016).

Hunter, Dominque, We Meet Here, I to XII (2017), exhibited at ‘Liminal Space’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali, at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI), New York (17 June–30 November 2017).

Koser, Khalid, ‘10 Migration Trends to Look out for in 2016’, World Economic Forum, 18 December 2015, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/12/10-migration-trends-to-look-out-for-in-2016/

Lobo, Arun Peter and Joseph J. Salvo, The Newest New Yorker, 2013 Edition: Characteristics of the City’s Foreign-Born Population (New York: New York City Department of City Planning, 2013).

Neptune, Christie, Memories from Yonder (2015) featured in the group exhibition ‘Liminal Space’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali.

Scarville, Keisha, ‘Mama’s Clothes’ (2015), exhibited in ‘Liminal Space’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali.

The CIA World Factbook 2017 (Cia.gov, 2017), https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gy.html

Wang, Vivian, ‘In Little Guyana, Proposed Cuts to Family Immigration Weigh Heavily’, New York Times, 11 August 2017.

1 Arun Peter Lobo and Joseph J. Salvo, The Newest New Yorker, 2013 Edition: Characteristics of the City’s Foreign-Born Population (New York: New York City Department of City Planning, 2013), p. 20.

2 Guyana’s emigration rate is among the highest in the world; more than 55% of its citizens reside abroad.

Central Intelligence Agency, The CIA World Factbook 2017 (Cia.gov, 2017), https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gy.html

3 ‘A Disappearing Nation’, Neither There Nor Here, BBC Radio 4, 28 February 2017, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08gmtx1

4 Artist statement submitted by Dominque Hunter for her digital collage work, We Meet Here, I to XII (2017) featured in the group exhibition ‘Liminal Space’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali, at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI), New York, on view 17 June 2017 to 30 November 2017.

5 Gaiutra Bahadur, ‘Of Islands and Other Mothers’, in Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Shapiro (eds.), Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), pp. 77–85 (p. 81).

6 Arun Peter Lobo and Joseph J. Salvo, The Newest New Yorker, 2013 Edition, p. 20.

7 In New York City, in particular, it is the Guyanese community, more than any other immigrant group, that utilizes family sponsorship visas to bring to the United States other members of their family. However, a 2017 New York Times article reported that they ‘could lose the most from a new federal effort to cut legal immigration in half’. See Vivian Wang, ‘In Little Guyana, Proposed Cuts to Family Immigration Weigh Heavily’, New York Times, 11 August 2017.

8 The World Economic Forum reported that by 2016, ‘Women will comprise more than half the world’s 232 million migrants for the first time. A growing proportion of these women will migrate independently and as breadwinners for their families’, See Khalid Koser, ‘10 Migration Trends to Look out for in 2016’, World Economic Forum, 18 December 2015, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/12/10-migration-trends-to-look-out-for-in-2016/

9 Kattian Barnwell, ‘Motherlands and Other Lands: Home and Exile in Jamaica Kincaid’s “Lucy” and Paule Marshall’s “Praisesong for the Widow”’, Caribbean Studies, 27 (1994), 451–54 (p. 452).

10 Artist statement submitted by Keisha Scarville for her portraiture series ‘Mama’s Clothes’ (2015) featured in the group exhibition ‘Liminal Space’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali, at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI), New York, on view 17 June 2017 to 30 November 2017.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Artist statement submitted by Erika DeFreitas for her portraiture series ‘The Impossible Speech Act’ (2007) featured in the group exhibition ‘Un |Fixed Homeland’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali, at Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art, Newark, New Jersey, on view 17 July 2016 to 23 September 2016.

14 Ibid.

15 Artist statement submitted by Christie Neptune for her mixed-media installation, Memories from Yonder (2015) featured in the group exhibition ‘Liminal Space’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali, at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI), New York, on view 17 June 2017 to 30 November 2017.

16 Bahadur, ‘Of Islands and Other Mothers’, p. 81.

17 Artist statement submitted by Christie Neptune for her mixed-media installation, Memories from Yonder (2015) featured in the group exhibition ‘Liminal Space’ curated by Grace Aneiza Ali, at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI), New York, on view 17 June 2017 to 30 November 2017.

18 Artist statement submitted by Khadija Benn for the portraiture series, ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’ (2017). Unpublished statement: received in correspondence with the artist.

19 Ibid.