Part Two Mobility and Migration

5. Carrying Memory

© 2019 Marianne Hirsch, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0153.05

In an era dominated by institutions of memory, and practices that monumentalize the past in the interests of present nationalist and ethnocentric imaginaries, a critical counter-aesthetic emerges in the work of women artists from different parts of the globe.1 I shall explore the resonances between three distinctly twenty-first-century projects by women artists responding to mobility and migration: En Camino by Argentinian artist Mirta Kupferminc, The End of Carrying All by Kenyan/US artist Wangechi Mutu, and ‘Portable Cities’ by Chinese artist Yin Xiuzhen. All three works turn to ordinary archives to explore the vicissitudes of diasporic lives. They create contingent and vulnerable memory practices that can help us recognize how women carry the burden of a painful past in a way that attempts to look to the future, both theirs and our own. But what are the implications of connecting works that emerge from such disparate contexts? What kind of analysis might enable us, in making these connections, to remain attentive to particular cultural contexts while also perceiving common strategies? It is my hope that my connective reading can define a productive feminist practice of solidarity and co-resistance across lines of difference.2

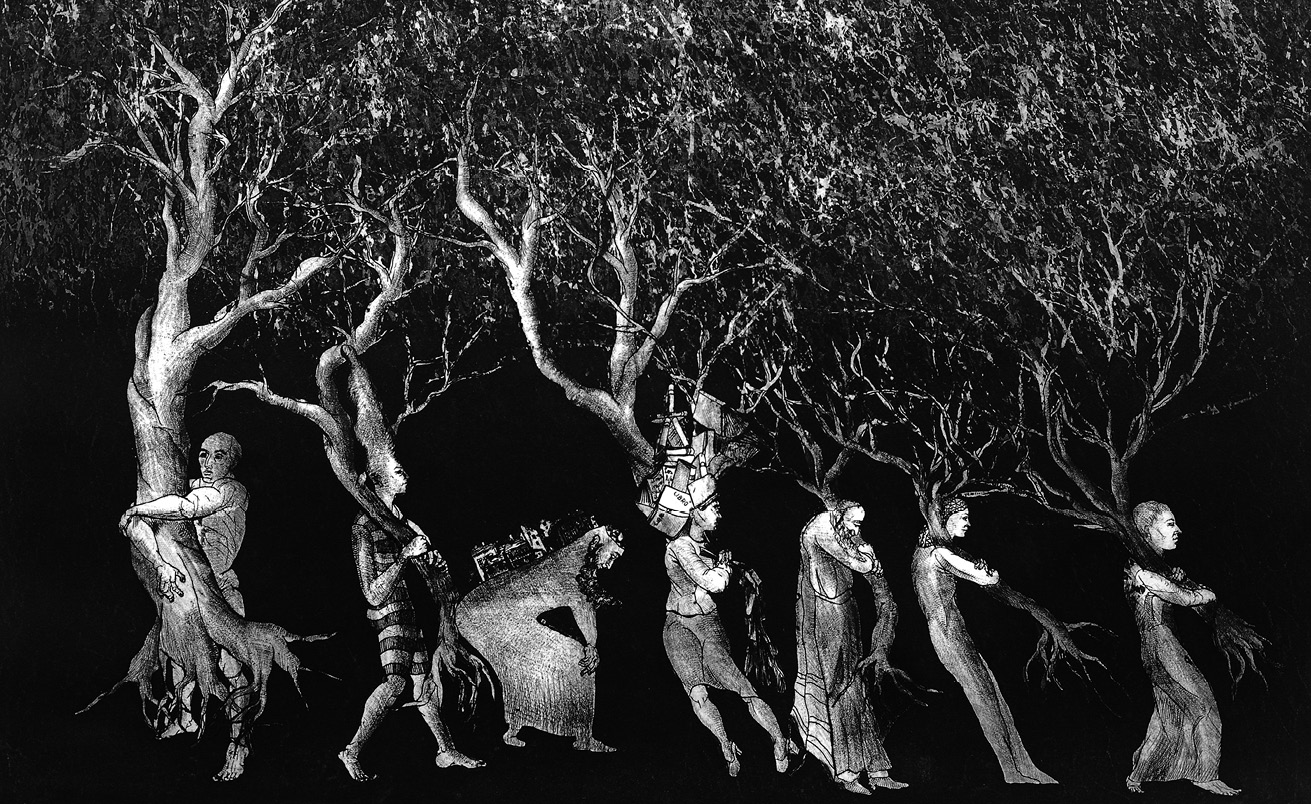

Fig. 5.1 Mirta Kupferminc, En Camino, 2001. Image provided by the artist. All rights reserved.

Mirta Kupferminc’s 2001 black and white etching En Camino [On the Way] portrays the difficult conditions of mobility in the aftermath of persecution and expulsion, exhibiting both the dangers and the potentialities inherent in diasporic memory acts. Seven figures led by a resolute woman in front attempt to move from left to right, but they are immobilized, pulled backward, hunched over under the weight of the objects they carry — not just uprooted trees, but houses, household objects, windmills, entire villages. This is even more dramatic in the vertical triptych version, in which the trees cover the top two panels, dwarfing the human figures under their shadow. What is more, these figures seem to float on different planes; there is no solid ground under their feet. Though their momentum points forward, they are slowed by the weight of memory and the past, a burden they cannot seem to shed. They lack the material support that might safely enable a freely chosen mobility.3 These are victims of expulsion, refugees, like those we see on the news every day, and they are slowed by the burdens they carry — legacies of the past.

Mirta Kupferminc is the daughter of Holocaust survivors from Hungary and Czechoslovakia; she was born and raised in their refuge in Argentina.4 Her work as a printmaker, photographer, video and installation artist is entirely devoted to, though not entirely weighted down by, this family history and its vicissitudes. In Kupferminc’s iconography of exile, uprooted trees signify removal from home and a violent break in continuity, genealogy and generation. Absorbing nourishment from the soil, trees contain knowledge of the past and carry it into the future but, if uprooted for too long, they will die, obliterating generations of history and memory. In the etching, and especially in a 2005 nine-minute animated version of En Camino, humans blend into the trees, themselves becoming embodied archives of past knowledge that they attempt, with difficulty, to carry forward.

Fig. 5.2 Still from Mirta Kupferminc and Mariana Sosnowski, En Camino, 2005. Image provided by the artist. All rights reserved.

But the animation elicits a very different affective response than the etching. It enables the motion of these characters without diminishing the weighty burden of memory that they continue to shoulder. Carrying suitcases, bags, trees, and other objects, these figures walk, run and climb, and they float and are blown around on multiple non-intersecting planes: forward, backward, sideways. They morph into hybrid mythic creatures, metamorphose into Hebrew letters; they float into and out of books and pages, walk up and down a ruler, emerge from a coat pocket. Hebrew letters multiply, torahs walk forwards and back. A king sits in a boat hovering precariously on top of the tower of Babel. Female figures, especially, carry heavy suitcases, moving slowly, laboriously, across the screen without looking up. Others, liberated, pirouette across our vision.

Fig. 5.3 Still from Mirta Kupferminc and Mariana Sosnowski, En Camino, 2005. Image provided by the artist. All rights reserved.

These characters seem trapped in the pages and within the repeated gestures of an ancient Jewish scenario of expulsion and exile, a story that is written both in support of and against the refugees themselves. The cyclical movement of the video implies its perpetual repetition, granting it the status of legend or myth. And yet, while the etching evokes memory as an overwhelming and paralyzing burden, the video is animated by surreal humor and incongruity — a playfulness that lightens without diminishing the yoke of the past and its own mythic dimensions. As letters float around on the screen, looking like the playful doodles of a child, we are also invited to imagine different scenarios with different beginnings and endings. The artist offers her characters the shapes of letters that can be arranged and rearranged, thus mobilizing multiple potential histories on the threshold of more open-ended futures. These recursive trajectories complicate a genealogical temporality of loss and attempted recovery. This is an evocative aesthetics of small gestures, in miniature. Its circuits of mythic memory bypass homogeneous national traditions and heteronormative genealogies in favor of diasporic networks that could be reimagined and reconfigured. But even in this movement, they remain anchored in a specifically Jewish story of disaster and loss that continues to slow and haunt them.

Kupferminc’s images address both recent and ancient Jewish history and philosophy. She is a student of Kabbalah, a reader of Jorge Luis Borges and Hannah Arendt, and an artist who experiments with different innovative media. Some of her work draws specifically on women’s artisanal practices, such as sewing, fabric, and embroidery, and she uses these to inscribe memory on the surface of the skin.

Fig. 5.4 Mirta Kupferminc, Bordado en la piel de la memoria, 2009. Image provided by the artist. All rights reserved.

In Bordado en la piel de la memoria [Embroidered on the Skin of Memory], for example, Kupferminc embroiders flowers and leaves seemingly into the lines of her palm. As she does so, she marks her body not so much with memorial representations but with traditional practices like embroidery that live on in the very skin of her hand. But the needle and thread left hanging on the top right fold of the left palm pierce the viewer, provoking a visceral shudder or squirm. As Roberta Culbertson wrote in a classic essay on trauma, a break in the skin most powerfully evokes the wounding that is trauma.5 The recuperation and transmission of artistic practice, the texture of the thread that sutures and connects cannot offset the piercing wound of the needle. Carrying these different forms of knowledge along from place to place, the body, and especially the hand, become the very site of memory and its transmission. And yet, the simple design of pretty flowers stitched in patterns that many of us learned as young girls is incongruous in relation to that disturbing wound. I would like to venture that the disjunction between the practice and the design leaves open a visceral space for a more open-ended response and perhaps also for alternate meanings we might glean from the stitches.

Kupferminc’s ‘migratory aesthetics’ do not envision recuperation or return.6 On the contrary, the wounds of expulsion and exile are carried on the body and skin. And yet, although Kupferminc’s work performs the unforgiving visceral transfer of a painful past to future generations, it allows us to glimpse the possibility of different futures — futures we, as viewers, can participate in imagining.

Reading Kupferminc’s work through a feminist critical lens, I argue it contributes to the formation of an aesthetic that activates small, unofficial, non-hegemonic collections and archives that mobilize feminist circuits of connectivity. It relates to aesthetic practices that have emerged from other diasporic communities — practices that mobilize personal and cultural loss in the service of alternative, non-linear, historical trajectories that bypass desires for recuperation and return.

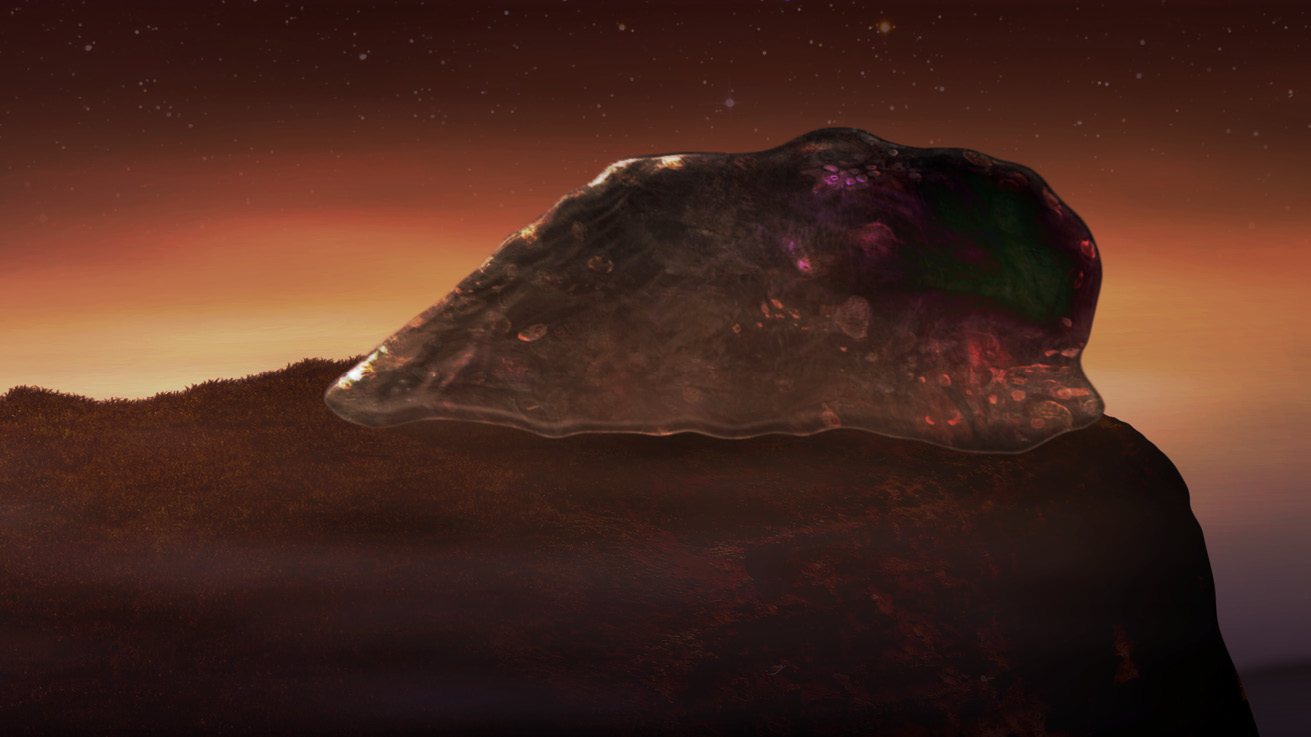

Fig. 5.5 Still from Wangechi Mutu, The End of Carrying All, 2015. Image courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, Victoria Miro, London, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. All rights reserved.

Wangechi Mutu’s The End of Carrying All, first exhibited at the 2015 Venice Biennale, also portrays, even while re-envisioning, the past as a burden to be carried. It shares the mythic yet anti-monumental quality of En Camino, as well as its attention to small household details that constitute both personal and communal lives. However, while the title En Camino signals the perpetual present of diasporic movement, The End of Carrying All expresses either a personal desire for closure or an apocalyptic ending to inexorable Sisyphean repetition. Both of these works could be seen as feminist re-visions of the Sisyphus myth, read not as an abstract human condition, but as historically and politically marked and gendered. Mutu doesn’t just refer to Sisyphus, however: the earth mother in her work is a kind of Cassandra who cyclically predicts, even while enacting, impending human and environmental catastrophe.

Born in Kenya and working in both Nairobi and New York, Wangechi Mutu is well-known for work in multiple media that explores the operation of gender and power as well as colonialism and globalization.7 Mutu’s three-channel video The End of Carrying All shows an African woman (Mutu herself) slowly swaying forward while balancing a large basket on her head. As she progresses, with ever greater difficulty, the basket gets filled with an increasing number of objects: bicycle wheels, electronic and household goods she collects along the way, causing her to bend more and more under their weight. The landscape evokes an African savannah, rich in color, though progressively getting darker and more threatening. On the soundtrack we hear the strong wind of the plains and the swarms of birds that ominously fill the unnaturally red skies.

Fig. 5.6 Still from Wangechi Mutu, The End of Carrying All, 2015. Image courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, Victoria Miro, London, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. All rights reserved.

As she walks, the woman approaches and then passes a tree that becomes more barren as its appearance recedes. When the weight of the basket becomes impossible to bear, the earth erupts and swallows the woman and her many belongings. At this point in the video we reach ‘the end of carrying all’. And then, of course, the journey begins again in an endless loop, linking the violence of the past to new disasters to come. Mutu compares this planetary apocalypse to a bodily wound: ‘the wound on the skin behaves similarly; eventually it bursts open and all that festering stuff comes out, and then it’s back to normal. But, you know, when things go, when the earth decides to clean up, it’s not going to go, oh you’re the good ones, you’re alright, you stay and they go.’8 This attention to the female body and its role in ‘carrying all’ of the past and the future marks Mutu’s work as feminist.

In both of these works, mobility is slowed by the weight of the past and also by a cyclicality that leaves little room for hope and change. And yet, the protagonist of Mutu’s video is both vulnerable and powerful. We could argue that her vulnerability, in fact, becomes a vehicle of resistance.9 But could we also say that by drawing on the knowledge of the past, she might re-envision the future and truly ‘start again’? If we are open to such a reading, the connection to Kupferminc’s En Camino is at its most powerful, opening Mutu’s work to less apocalyptic interpretations.

Fig. 5.7 Still from Wangechi Mutu, The End of Carrying All, 2015. Image courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, Victoria Miro, London, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. All rights reserved.

Responding to the theme of the 2015 Biennale, ‘All the World’s Futures’, the work was described as a critique of capitalism and environmental disaster, of the violence done to indigenous landscapes by the consumption and waste resulting from colonization. These are recognizable themes in Mutu’s sculptures and collages and in the feminist mythologies she invokes and (re)creates. In her sculpture and collage work, she recycles the materials of global capitalism, such as junk mail and magazine pictures. Hers is thus a work of critique that all the while also practices salvage and attempted healing.

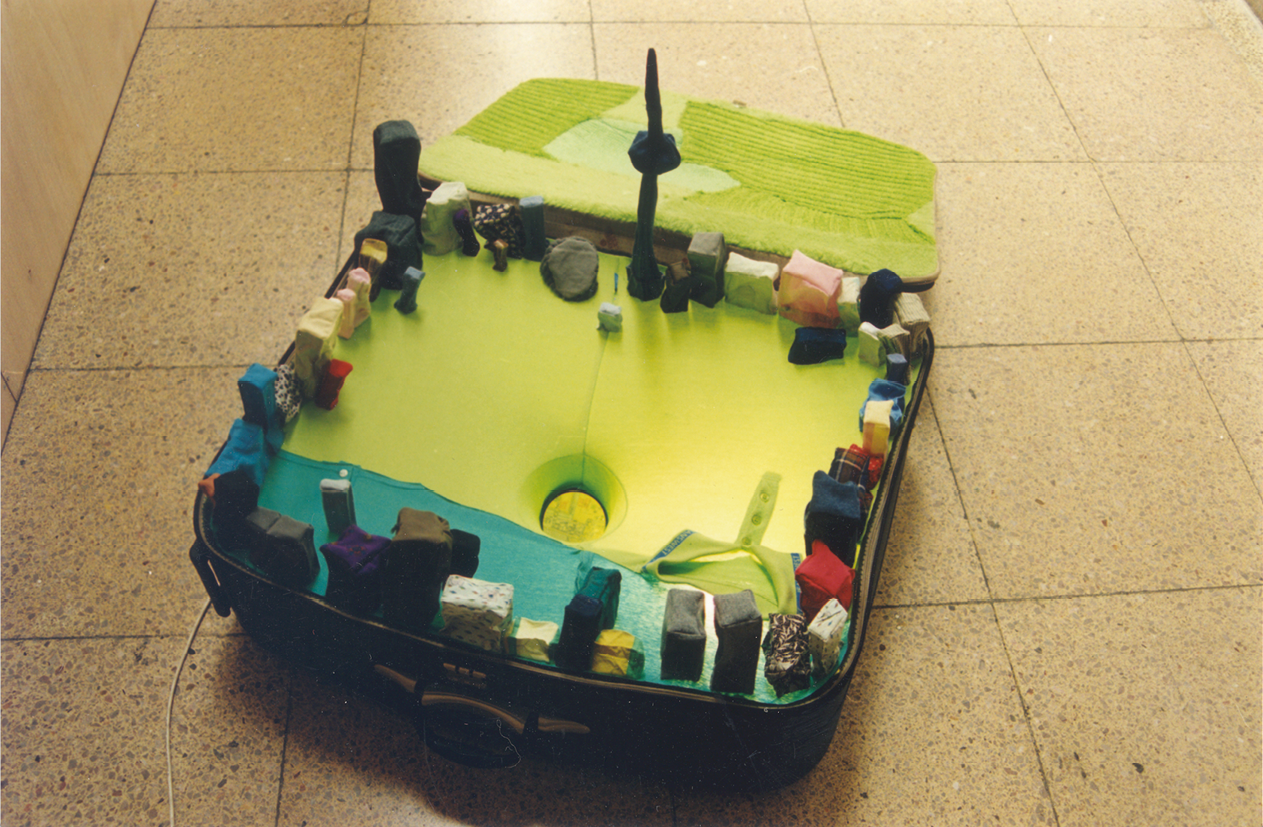

Fig. 5.8 Yin Xiuzhen, Portable Cities: Beijing, 2001. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery. All rights reserved.

‘Portable Cities’ by the Chinese artist Yin Xiuzhen, begun in 2001 and ongoing, is another distinctly anti-monumental memory project. Although it does not respond to a specific history of trauma and destruction, it offers counterpoints and parallels to Kupferminc and Mutu that further illustrate the promises of memory’s mobility as well as the difficulties of mobilizing memory for change.

Living and working in Beijing, Yin Xiuzhen is a sculptor and installation artist who incorporates numerous materials from everyday life into her work.10 She has been building cityscapes in open suitcases. Toy-like miniature buildings are made out of fabrics, buttons and other objects collected from people living in the communities where the work is created and displayed — cities like New York, Beijing, Melbourne, Tokyo and Düsseldorf. To supplement the viewer’s visual and tactile engagement with the work, each suitcase also contains a soundscape recorded in that city’s public spaces. And each suitcase has a small hole that invites us to look through a magnifying glass at a map of the city displayed on the level below.

Fig. 5.9 Yin Xiuzhen, Portable Cities: Groningen, 2012. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery. All rights reserved.

‘The earliest inspiration for my suitcase work came from the baggage lines at the airport,’ the artist writes.11 As she traveled for her exhibits and watched the suitcases roll by, she ‘thought each one was like a tiny shrunken home.’ A witty response to the travails of globalization and the resulting homogenization of urban landscapes that ‘shrinks difference’ and reduces urban spaces to recognizable landmarks, the ‘Portable Cities’ nevertheless ‘carry’ the artist’s personal feelings about each site. At the same time, they are also sites of collective memory, transporting the bodily imprints of the people who wore and touched the clothes and objects Yin uses to make the suitcase cities. ‘I believe that clothing is people’s second skin,’ the artist said in an interview.12 As she sews the experiences of people together by means of their old clothes, transforming these into miniature buildings, bridges, parks and squares, Yin magically creates what she thinks of as a ‘collective unconscious.’

Philippe Vergne writes that in Yin’s work ‘memory becomes a critical tool.’13 The ‘Portable Cities’ and her other work using recycled materials counters the destruction of traditional ways of life and the constant renewal, traffic and exchange that characterizes the era of globalization. Airports and public restrooms are the spaces she uses as sites of intervention as she reconfigures the hard technologies of globalization, imbuing weapons, television towers, airplanes, engines, cars and buses with the softness of cotton, wool and silk. This is a practice of small-scale resistance and memorialization, reshaping objects from the past and endowing them with new life and new meanings, enabling them to carry multiple unprocessed memories towards a future that obliviously races ahead.

In the space of the gallery, the cities Yin has rebuilt in miniature form are connected by blue threads on a large map mounted on a wall, forming a network of contact and interconnection — a network that is in constant flux as new nodal points appear along its routes. Though portable, the cities are nevertheless fixed unto a large map: even in their mobility they remain pinned to the wall.

Fig. 5.10 Yin Xiuzhen, Portable Cities: San Francisco, 2003. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery. All rights reserved.

Rather than locating memory on site, the ‘Portable Cities’ allow sites and monuments of memory to travel, sparking recall wherever they go and thus activating networks of transnational and global connectivity as well. Yin’s is an aesthetics of vulnerability that miniaturizes the details of everyday life to enable us to gain some ironic and playful distance from their eventfulness and monumentality, from the losses and transformations that shape them.

Cities are spaces of transformation and renewal par excellence, and they are also sites of memory and commemoration. In Yin’s work, even mega-cities become small, manageable and portable. Contrast the suitcase cities to the burdensome suitcases in Mirta Kupferminc’s ‘En Camino’ or the basket in Mutu’s video. Sitting on the floor of the gallery or museum, housing miniature buildings and sites, Yin’s seem light and compact. Bodily traces survive in the small stitches that construct the miniature structures and in the containers of other people’s possessions, transported across borders, along routes of displacement and renewal. But they do not weigh us down; they merely serve to slow natural and manufactured processes of oblivion in a globalized world where consumption dominates. As their contents can be repurposed, recycled and discarded, these memories lack the heaviness of traumatic expulsion. And yet, the import of individual and local histories still cling to every stitch, demanding contextualization. Mobility seems to be performed here lightly, inconsequentially, for its own sake. The suitcase cities galvanize a movement forward that recalls individual and collective hopes and disappointments, without being unduly encumbered by them. Thus, they serve as ironic foils to monumentality, inspiring other acts and objects of small-scale resistance.

The small gestures of intervention performed by these three women artists — their miniaturization; their embrace of incongruity and contradiction; their use of animation; their humor, fantasy and play — are counterbalanced by their careful attention to particular and located bodies and traditions. Even as they insist on this particularity, however, they also invite connections across histories and geographies. They resist the monumentality that memory has acquired in our eventful present, a monumentality that has been holding us back. And they inspire us to think further about how memory might be mobilized for a progressive future.

Bibliography

Bal, Mieke, ‘Migratory Aesthetics: Double Movement’, Exit, 32 (2008), 150–61.

Barber, Tiffany E. and Angela Naimou, ‘Between Disgust and Regeneration: An Interview with Wangechi Mutu’, ASAP/Journal (September 2016), 337–63, https://doi.org/10.1353/asa.2016.0026

Butler, Judith, ‘Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance’, in Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay, eds. Vulnerability in Resistance (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), pp. 12–27.

Culbertson, Roberta, ‘Embodied Memory, Transcendence and Telling: Recounting Trauma, Re-establishing the Self’, New Literary History, 26.1 (1995), 169–95.

Hirsch, Marianne, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

Wu, Hung, Hou Hanru, and Stephanie Rosenthal, Yin Xiuzhen (London: Phaidon Press, Contemporary Artists Series, 2015).

1 This essay is inspired by the privilege of working within several transnational feminist networks of scholars, artists and activists — the ‘Women and Migration’ group based at New York University, and the ‘Women Mobilizing Memory’ working group based at the Center for the Study of Social Difference, Columbia University.

2 On connective memory practices, see Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

3 Judith Butler has made this claim in her essay ‘Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance’, in Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay, eds. Vulnerability in Resistance (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), pp. 12–27.

4 Mirta Kupferminc, www.mirtakupferminc.net

5 Roberta Culbertson, ‘Embodied Memory, Transcendence and Telling: Recounting Trauma, Re-establishing the Self’, New Literary History, 26.1 (1995), 169–95 (p. 170).

6 For the notion of ‘migratory aesthetics’, see Mieke Bal, ‘Migratory Aesthetics: Double Movement’, Exit, 32 (2008), 150–61.

8 Tiffany E. Barber and Angela Naimou, ‘Between Disgust and Regeneration: An Interview with Wangechi Mutu’, ASAP/Journal (September 2016), 337–63 (p. 352).

9 The connections between vulnerability and resistance are explored by the contributors to Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay (eds.), Vulnerability in Resistance (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

11 Hung Wu, Hou Hanru, and Stephanie Rosenthal, Yin Xiuzhen (London: Phaidon Press, Contemporary Artists Series, 2015), p. 102.

12 Ibid., p. 189.

13 Ibid., p. 150.