Preface

© 2019 Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0176.01

It is as Bolsheviks that the Jews of South Russia have been massacred by the armies of [the Ukrainian leader Simon] Petliura, though the armies of Sokolov have massacred them as partisans of Petliura, the armies of Makhno as bourgeois capitalists, the armies of Gregoriev as Communists, and the armies of Denikin at once as Bolsheviks, capitalists, and Ukrainian nationalists. It is Aesop’s old fable.

Israel Zangwill, Jewish Chronicle, 23 January 1920

The pogroms in Ukraine between 1917 and 1921 represent the largest and bloodiest anti-Jewish massacres prior to the Holocaust. The estimated number of Jews murdered in Ukraine in the aftermaths of World War I ranges from 50,000 to 200,000,1 with many more Jews suffering violence, rape,2 and loss of property. Altogether 1.6 million Jews were affected by these violent events. Although it is impossible to determine the exact number of victims of these pogroms, there is no doubt that this was the largest outbreak of anti-Jewish violence before the Shoah, the genocide during World War II in which 6 million European Jews, around two-thirds of the Jewish population of the continent, were systematically murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators.

Being overshadowed by the Holocaust, the pogroms in Ukraine are still not widely known. This unfortunate state of affairs is due to a number of factors. Firstly, the complex nature of the anti-Semitic violence perpetrated in 1917–1921 Ukraine. As hinted in Zangwill’s quote above, the Jews were attacked by a number of different groups of perpetrators including Anton Denikin’s Russian White Army, Simon Petliura’s Army of the Ukrainian Republic, various peasant units, hoodlums, anarchists, and the Bolshevik Red Army.

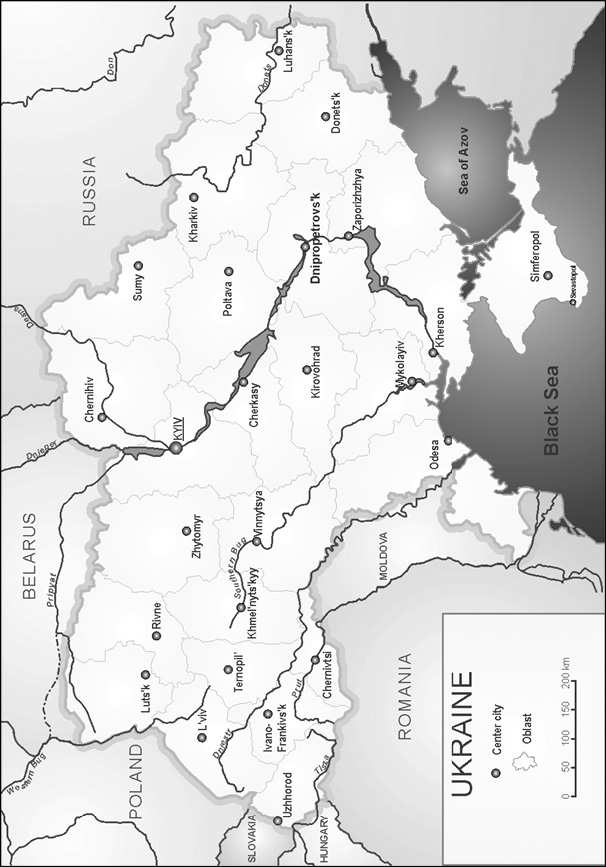

These attacks stemmed from a number of grievances: accusations of supporting the enemy side, the chaos following the collapse of the old order, the aftermath of World War I and of the Russian Revolution, and a widespread anti-Semitism, after the dissolution of the Russian and Habsburg Empire. Furthermore, the perpetrators could easily locate their victims, as the areas affected were situated within the old Pale of Settlement, a region designated for Jews within today’s Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, and Moldova.3

The relative lack of research on these events provides a further explanation of why the Ukrainian pogroms are much less known than the persecution the Jews suffered at the hand of the Nazis and other perpetrators during the Shoah. If, over the last 70 years, research on the Holocaust has resulted in several thousand publications, which can be housed only in the library of a large institute such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the publications relating to the pogroms of 1917−1921 would fill no more than two or three shelves. It is however hoped that the anti-Semitic campaigns taking place in early-twentieth-century Ukraine will in the future be recognized as an important chapter in the history of genocide studies.

Among the many perpetrators of the pogroms, it was Petliura who became the symbol of these massacres. Scholars have long debated whether Petliura was an anti-Semite who deliberately targeted the Jews, or a weak leader who could not stop their aggressors. Some answers to this complex question were put forward two decades ago by Henry Abramson, and more recently by Antony Polonsky and Christopher Gilley.4 These scholars maintained that although Petliura’s soldiers were responsible for the death of about forty percent of the victims, their commander’s own behavior during the pogroms was ambivalent. On the one hand, Petliura seems not to have held anti-Semitic views and he did not personally issue orders to kill the Jews. On the other, he did very little to stop the massacres, particularly between January and April 1919, the period of the most brutal persecutions, even though the Ministry of Jewish Affairs urged him to do so. As Christopher Gilley writes, ‘Petliura lacked the responsibility of agency for the pogroms, but as head of the army [he] must be held accountable for them.’5

Nevertheless, Petliura began to be seen as the main perpetrator of the pogroms only after his assassination on 25 May 1926 in Paris by Sholom Shwartzbard, a Russian-born French Yiddish poet of Jewish descent who had been in Ukraine during the massacres. The French court acquitted Schwartzbard, recognizing that he avenged the victims of Petliura’s troops. This verdict enraged the Ukrainian nationalists who from now on claimed that Schwartzbard was a Bolshevik (or a Russian agent) who killed Petliura because he fought for an independent Ukraine. Interestingly Ukrainian nationalists had initially disliked Petliura due to his alliance with Józef Piłsudski in 1920. However, this view changed after his assassination, which, in their eyes, transformed Petliura into a hero who fought and died for an independent Ukraine. As Dmytro Dontsov, one of the leading radical Ukrainian nationalists, wrote after the trial:

This murder is an act of revenge by an agent of Russian imperialism against a person who became a symbol of the national struggle against Russian oppression. It does not matter that in this case a Jew became an agent of Russian imperialism. […] We have to and we will fight against the aspiration of Jewry to play the inappropriate role of lords in Ukraine. […] No other government took as many Jews into its service as did the Bolsheviks, and one might expect that like Pilate the Russians will wash their hands and say to the oppressed nations, ‘The Jew is guilty of everything’.6

Petliura continued to be glorified by nationalists well after his death. During the pogroms perpetrated by the Nazis and the Ukrainian nationalists in Lviv, the capital of western Ukraine, in the summer of 1941, the perpetrators staged the ‘Petliura days’ in his honor. After the main wave of pogroms in late June and early July 1941 came to an end, on 25 July 1941 the local nationalists organized with the Germans additional three days of pogroms to ‘avenge’ Petliura’s assassination.7 During the Cold War the Ukrainian diaspora celebrated him next to other national ‘heroes’ such as Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych.

Moreover Ukrainian nationalist historians such as Taras Hunczak portrayed Petliura as a Judeophile who actively opposed the pogromists. Notwithstanding Petliura’s responsibility for the pogroms, this revisionist approach is alive to this day — the one-time commander of the Army of the Ukrainian Republic is still hailed as a symbol of anti-Semitism and a ‘national hero’. A monument to Petliura was unveiled in Vinnytsia in 2017.8

In contrast to Petliura, Anton Denikin did not become the symbol of the pogroms, although the massacres committed by his army were generally known. One important reason why he has not been associated with the anti-Semitic violence in Ukraine is his unspectacular life after the end of the Russian Civil War. When the Red Army defeated the White Army, he escaped with the rest of his soldiers to Crimea. In April 1920, he left to Constantinople and then to London. From 1926, he lived in France but he did not engage in politics, focusing on writing. The crimes committed by his army have not been forgotten but they were neither investigated as thoroughly as the massacres done by the Petliura army nor did they arouse any major controversies, because none tried to systematically or deliberately deny them as the Ukrainian nationalists did in the case of Petliura’s soldiers.

In order to understand the nature of the anti-Jewish violence between 1918 and 1921 in Ukraine, we need critical and nuanced studies instead of monuments and cults. A key source for further research into these massacres are the survivor accounts and early publications written by the survivors soon after the events. Nokhem Shtif’s The Pogroms in Ukraine: The Period of the Volunteer Army is one such study. Shtif’s book can be compared to the works published by the members of the Jewish Historical Commission, which was created in 1944 by survivors of the Shoah in liberated Poland. This group of young Jews collected several thousand survivor testimonies and published important early studies on the Holocaust.9

Shtif, a linguist, writer and journalist, was the editor-in-chief of the Editorial Committee for the Collection and Publication of Documents on the Ukrainian Pogroms, which was founded in Kiev in May 1919. He collected the material during the pogroms and published his book in Berlin in 1923. His study stands alongside Nokhem Gergel’s The Pogroms in Ukraine in the Years 1918–1921 and Elias Tcherikover’s Antisemitism and the Pogroms in Ukraine: The Period of the Central Rada and the Hetman, 1917–1918, one of the most important early publications on the topic.10 Unlike other authors, Shtif did not focus on Petliura and his troops but on Denikin’s White Army. A particularly perceptive study of the violence inflicted on the Ukrainian Jews and its perpetrators, The Pogroms in Ukraine, 1918–19: Prelude to the Holocaust fills the gaps in our understanding of the largest massacres before the Holocaust. This translation from the Yiddish published in Open Access finally makes this important study accessible to scholars, students and the wider readership.

Political map of Ukraine by Sven Teschke. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Ukraine_political_enwiki.png

1 The early pogrom researcher Nokhem Gergel estimated 50,000 to 60,000 victims. See Nokhem Gergel, “The Pogroms in the Ukraine in 1918–21,” Yivo Annual of Jewish Science 6 (1951), 237–52 (p. 249).

2 On this topic see Irina Astashkevich, Gendered Violence: Jewish Women in the Pogroms of 1917 to 1921 (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2018), http://www.oapen.org/download?type=document&docid=1001750

3 The Pale of Settlement was originally formed in 1791 by Russia’s Catherine II. For political, economic, and religious reasons, very few Jews were allowed to live elsewhere. At the end of the nineteenth century, close to 95 percent of the 5.3 million Jews in the Russian Empire lived in the Pale of Settlement. In early 1917, the Pale of Settlement was abolished, permitting Jews to live where they wished in the former Russian Empire. This region continued to be a center of Jewish communal life until World War II. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/image/pale-settlement

4 Henry Abramson, A Prayer for the Government: Ukrainians and Jews in Revolutionary Times, 1917–1920 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Ukrainian Research Institute and Center for Jewish Studies, 1999); Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia, 1914‒2008 (Oxford: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2010), III, 32–43; Christopher Gilley, ‘Beyond Petliura: The Ukrainian National Movement and the 1919 Pogroms’, East European Jewish Affairs 47.1 (2017), 45–61.

5 Gilley, ‘Beyond Petliura’, p. 47. See also Serhii Iekelchyk, ‘Trahichna storinka Ukrains’koi revoliutsii: Symon Petliura ta Ievreis’ki pogrom v Ukraini (1917–1920)’, in Vasyl Mykhal’chuk (ed.), Symon Petliura ta ukrains’ka natsional’na revoliutsiia (Kyiv: Rada, 1995), pp. 165–217.

6 Dmytro Dontsov, ‘Symon Petliura’, Literaturno Naukoyi Vistnyk 7–8:5 (1926), 326–28.

7 Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist: Fascism, Genocide, and Cult (Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2014). On the pogroms in Ukraine in general, see Kai Struve, Deutsche Herrschaft, ukrainischer Nationalismus, antijüdische Gewalt: Der Sommer 1941 in der Westukraine (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2015).

8 Taras Hunczak, ‘A Reappraisal of Symon Petliura and Ukrainian–Jewish Relations, 1917–1921’, Jewish Social Studies 31:3 (1969), 163–83.

9 Laura Jockusch, Collect and Record!: Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

10 Nokhem Gergel, ‘The Pogroms in Ukraine in the Years 1918–1921’, in Shriftn far ekonomik un statistic, I, 1928, English translation in YIVO Annual of Jewish Social Science (New York: Yivo Institute for Jewish Research, 1951), pp. 237–52; Elias Tcherikower, Antisemitizm un pogromen in Ukraine, 1917–1918: tsu der geshikhte fun Uḳrainish-Yidishe batsihungen (Berlin: Mizreh-Yidishn hisṭorishn arkhiṿ, 1923).