Foreword

Even for those of us who are one step removed from nature in our present-day lives, looking back on places we called home as children can reveal disturbing truths. This is certainly true for me. I grew up in a small mining town in Zimbabwe called Kadoma, and as soon as school was out, my parents would bundle me off to Mhondoro, a rural area to the east.

I loved it there and happily spent hours herding cattle across the quintessential untamed African savannah. I have many fond memories of swimming and catching fish in Mhondoro too. I recall how the surrounding forests were lush, teeming with wildlife; rivers were bountiful, full of fish and fowl in the pristine fresh water. City folk went home with their hands full of gifts from nature and agricultural fields.

Today, when I return to my village in Mhondoro, my heart breaks. The lush forests and wildlife are gone, replaced with barren fields and a whimpering stream where the river once ran. I now bring my own food and bottled water when I visit. And worst of all, the people of Mhondoro who I had always associated with nature’s abundance are today poor and disenfranchised and have few if any options for bettering their lives.

Tragically, the story of my village is shared by thousands of villages across Africa that are suffering the worst impacts of climate change, population growth and harmful development choices. Faced with the challenge of feeding their families and generating cash incomes, farmers, like those of Mhondoro, end up expanding their crops increasingly deeper into wild lands and forests. These encroachments not only bring their families into dangerous conflict with wildlife, they simultaneously endanger and destroy the forests and fertile soils that would otherwise support their agricultural bounty.

But this outcome is not inevitable.

Africa suffers the greatest burden of global heating and deteriorating nature. As such, there is recognition that a “new deal for nature” is needed if we are to avert the worst climate and nature crisis. A new deal that transforms the way we produce our food and choose what to consume, the way we develop infrastructure, including our cities, roads, housing and dams, produce our energy and the way we value nature in our economic systems. The search is on for solutions.

But Africa risks being left behind or having to acquiesce to solutions that are not fit nor ideal for the continent. If Africa is to meaningfully define solutions for a new deal for nature, we must support research capacity and skills building within its populations, including investments in faculty and research leaders, facilities and infrastructure, and expanding career opportunities for budding researchers to apply their findings in real world settings.

Fortunately, there is now widespread acknowledgement that African researchers are best placed to ask questions and find solutions to the challenges facing Africa. Hence, we are witnessing a slow move away from the notion that researchers from high income countries must be parachuted in to identify and address the continent’s problems.

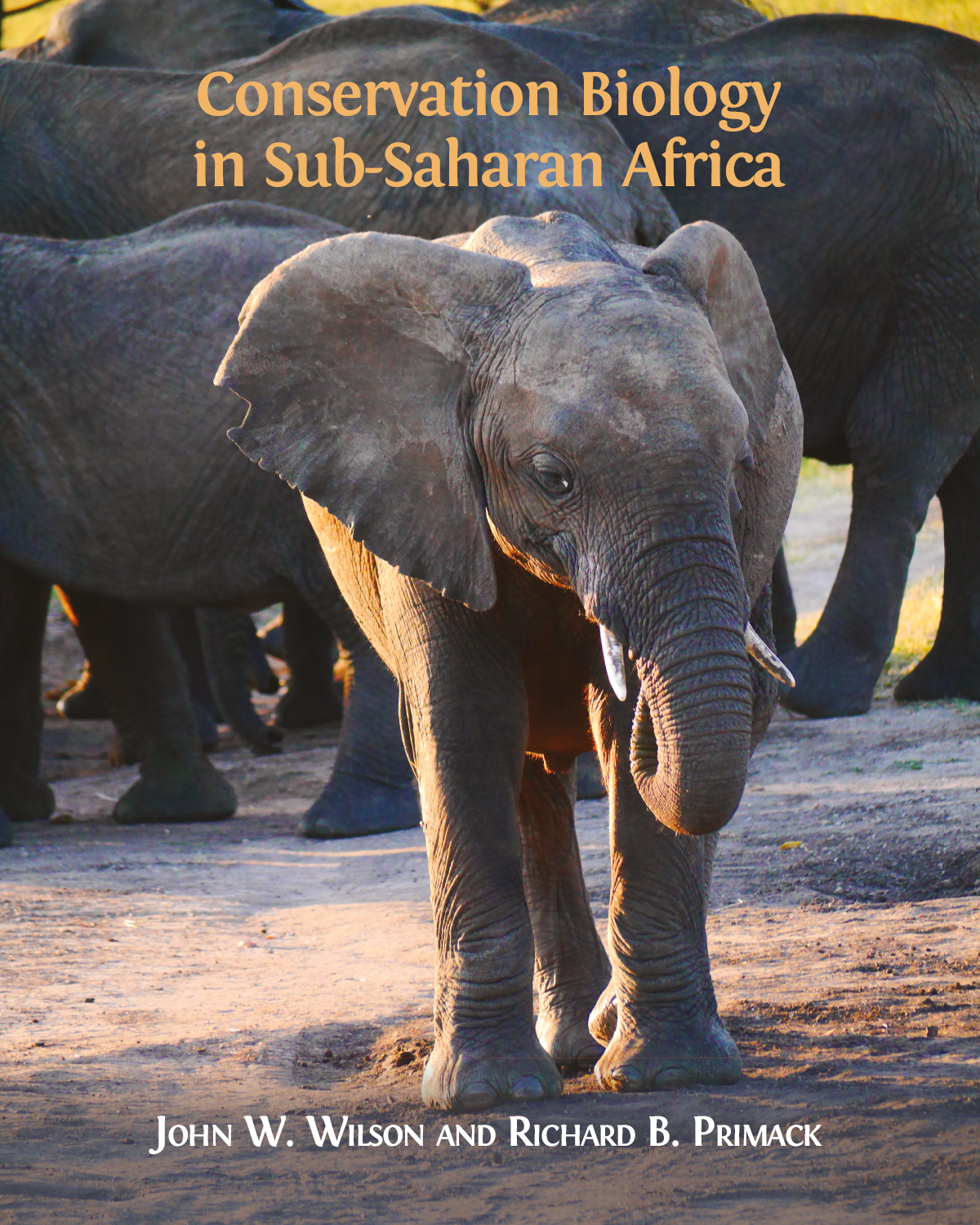

This textbook, Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa, is a critical first step as it goes a long way towards focusing attention to the urgent need to define the nature of the problem and develop practical, context specific solutions to Africa’s many environmental challenges. It discusses how our lives are inextricably linked to a healthy environment, explores how inclusive conservation can provide greater benefits to all, and illustrates how grassroots action can ensure that nature’s many beneficial contributions will remain available for generations to come.

By being distributed for free, this textbook ensures that its readership can include those who stand to benefit the greatest, including African researchers and practitioners. Open access textbooks like it are critical to expanding access to African research and improving intra-African research collaboration and capacity.

If we are to “leave no one behind,” as agreed by global leaders in 2015 and encapsulated in Sustainable Development Goals, farmers like those from Mhondoro will also need access to the best available information, science and solutions. That is a deal that we owe them—and the many people who call Africa their home. This book makes an important contribution to the challenge. I hope that, thanks to the efforts of the experts featured in this textbook and others, one day when I return to Mhondoro, it will more closely resemble its prior self that I loved as a child.

Maxwell Gomera

Director: Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Branch