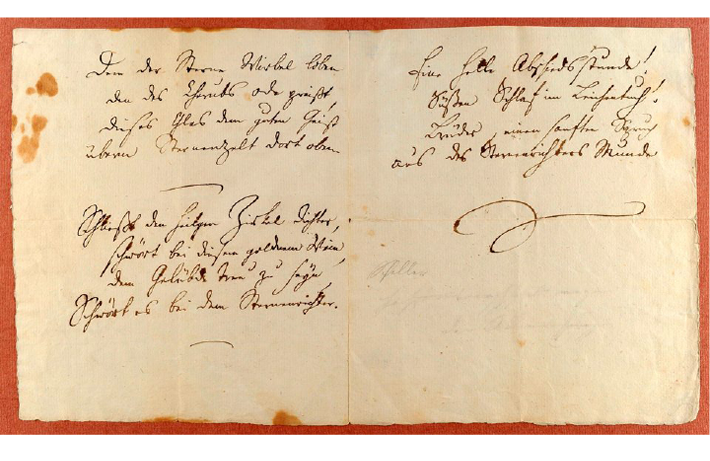

Autograph of Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’ (1785). Photograph by Historiograf (2011), Wikimedia, Public Domain, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2d/Schiller_an_die_freude_manuskript_2.jpg

10. Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’: A Reappraisal1

© 2021 Hugh Barr Nisbet, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0180.10

|

Freude, schöner Götterfunken21 |

||

|

Tochter aus Elysium, |

||

|

Wir betreten feuertrunken |

||

|

Himmlische, dein Heiligtum. |

||

|

Deine Zauber binden wieder, |

||

|

Was der Mode Schwert geteilt; |

||

|

Bettler werden Fürstenbrüder, |

||

|

Wo dein sanfter Flügel weilt. |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Seid umschlungen, Millionen! |

||

|

|

Diesen Kuß der ganzen Welt! |

|

|

Brüder—überm Sternenzelt |

||

|

|

Muß ein lieber Vater wohnen. |

|

|

Wem der große Wurf gelungen, |

||

|

Eines Freundes Freund zu sein; |

||

|

Wer ein holdes Weib errungen, |

||

|

Mische seinen Jubel ein! |

||

|

Ja—wer auch nur eine Seele |

||

|

Sein nennt auf dem Erdenrund! |

||

|

Und wer’s nie gekonnt, der stehle |

||

|

Weinend sich aus diesem Bund! |

||

|

|

Chor |

|

|

Was den großen Ring bewohnet, |

||

|

Huldige der Sympathie! |

||

|

Zu den Sternen leitet sie, |

||

|

Wo der Unbekannte thronet. |

||

|

Freude trinken alle Wesen |

||

|

An den Brüsten der Natur, |

||

|

Alle Guten, alle Bösen |

||

|

Folgen ihrer Rosenspur. |

||

|

Küsse gab sie uns und Reben, |

||

|

Einen Freund, geprüft im Tod. |

||

|

Wollust ward dem Wurm gegeben, |

||

|

Und der Cherub steht vor Gott. |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Ihr stürzt nieder, Millionen? |

||

|

Ahndest du den Schöpfer, Welt? |

||

|

Such ihn überm Sternenzelt, |

||

|

Über Sternen muß er wohnen. |

||

|

Freude heißt die starke Feder |

||

|

In der ewigen Natur. |

||

|

Freude, Freude treibt die Räder |

||

|

In der großen Weltenuhr. |

||

|

Blumen lockt sie aus den Keimen, |

||

|

Sonnen aus dem Firmament, |

||

|

Sphären rollt sie in den Raümen, |

||

|

Die des Sehers Rohr nicht kennt. |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Froh, wie seine Sonnen fliegen, |

||

|

Durch des Himmels prächtgen Plan, |

||

|

Laufet, Brüder, eure Bahn, |

||

|

Freudig wie ein Held zum Siegen. |

||

|

Aus der Wahrheit Feuerspiegel |

||

|

Lächelt sie den Forscher an. |

||

|

Zu der Tugend steilem Hügel |

||

|

Leitet sie des Dulders Bahn. |

||

|

Auf des Glaubens Sonnenberge |

||

|

Sieht man ihre Fahnen wehn, |

||

|

Durch den Riß gesprengter Särge |

||

|

Sie im Chor der Engel stehn. |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Duldet mutig, Millionen! |

||

|

Duldet für die beßre Welt! |

||

|

Droben überm Sternenzelt |

||

|

Wird ein großer Gott belohnen. |

||

|

Göttern kann man nicht vergelten, |

||

|

Schön ists, ihnen gleich zu sein. |

||

|

Gram und Armut soll sich melden, |

||

|

Mit den Frohen sich erfreun. |

||

|

Groll und Rache sei vergessen, |

||

|

Unserm Todfeind sei verziehn, |

||

|

Keine Träne soll ihn pressen, |

||

|

Keine Reue nage ihn. |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Unser Schuldbuch sei vernichtet! |

||

|

Ausgesöhnt die ganze Welt! |

||

|

Brüder—überm Sternenzelt |

||

|

Richtet Gott, wie wir gerichtet. |

||

|

Freude sprudelt in Pokalen, |

||

|

In der Traube goldnem Blut |

||

|

Trinken Sanftmut Kannibalen, |

||

|

Die Verzweiflung Heldenmut – |

||

|

Brüder, fliegt von euren Sitzen, |

||

|

Wenn der volle Römer kreist, |

||

|

Laßt den Schaum zum Himmel sprützen: |

||

|

Dieses Glas dem guten Geist. |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Den der Sterne Wirbel loben, |

||

|

Den des Seraphs Hymne preist, |

||

|

Dieses Glas dem guten Geist |

||

|

Überm Sternenzelt dort oben! |

||

|

Festen Mut in schwerem Leiden, |

||

|

Hülfe, wo die Unschuld weint, |

||

|

Ewigkeit geschwornen Eiden, |

||

|

Wahrheit gegen Freund und Feind, |

||

|

Männerstolz vor Königsthronen – |

||

|

Brüder, gält es Gut und Blut, – |

||

|

Dem Verdienste seine Kronen, |

||

|

Untergang der Lügenbrut! |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Schließt den heilgen Zirkel dichter, |

||

|

Schwört bei diesem goldnen Wein: |

||

|

Dem Gelübde treu zu sein, |

||

|

Schwört es bei dem Sternenrichter! |

||

|

Rettung vor Tyrannenketten, |

||

|

Großmut auch dem Bösewicht, |

||

|

Hoffnung auf den Sterbebetten, |

||

|

Gnade auf dem Hochgericht! |

||

|

Auch die Toten sollen leben! |

||

|

Brüder trinkt und stimmet ein, |

||

|

Allen Sündern soll vergeben, |

||

|

Und die Hölle nicht mehr sein. |

||

|

Chor |

||

|

Eine heitre Abschiedsstunde! |

||

|

Süßen Schlaf im Leichentuch! |

||

|

Brüder—einen sanften Spruch |

||

|

Aus des Totenrichters Munde! |

||

English translation:

|

Joy, thou lovely spark immortal, |

||

|

Daughter from Elysium, |

||

|

Drunk with fire we dare to enter |

||

|

Heavenly one, thy holy shrine. |

||

|

Your magic spells have reunited, |

||

|

What the sword of custom cleft; |

||

|

Beggars become princes’ brothers, |

||

|

Where your gentle wings alight. |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

We embrace you, all ye millions! |

||

|

Let all the world receive this kiss! |

||

|

Brothers—above the starry heavens |

||

|

There must dwell a loving father. |

||

|

Whoever met the weighty challenge, |

||

|

Whoever won a lovely woman, |

||

|

Let him mix his joy with ours! |

||

|

And even him who on this earth |

||

|

Has just one soul to call his own! |

||

|

But let who never passed this test |

||

|

Steal weeping from this league of ours! |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

May all who dwell in this great ring |

||

|

Pay homage now to sympathy! |

||

|

To the stars it leads the way, |

||

|

To the unknown being’s throne. |

||

|

Joy is drunk by every creature |

||

|

Drunk by all at nature’s breasts, |

||

|

All the good, and all the evil |

||

|

Follow down her rosy path. |

||

|

She gave us both vines and kisses, |

||

|

And a friend, loyal unto death. |

||

|

Even the worm is rapture given, |

||

|

The cherub stands in face of God. |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

You fall before him all ye millions! |

||

|

Do you the world’s creator sense? |

||

|

Seek him beyond the starry vault, |

||

|

Above the stars he has his dwelling. |

||

|

Joy is yet the mighty mainspring |

||

|

In eternal nature’s realm. |

||

|

For by joy the wheels are driven |

||

|

In the universal clock. |

||

|

From the buds she draws the flowers, |

||

|

Suns out of the firmament, |

||

|

Spheres she rolls within the spaces |

||

|

That no seer’s lens can scan. |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

Happy, as his suns are flying, |

||

|

On the heavens’ splendid plane, |

||

|

Run, ye brothers, on your courses, |

||

|

Joyful, like a conquering hero. |

||

|

Out of truth’s refulgent mirror |

||

|

The researcher sees her smile. |

||

|

To the steep hillside of virtue |

||

|

The endurer’s path she guides. |

||

|

Up on faith’s high sunlit mountain |

||

|

One can see her banners fly, |

||

|

Through the crack of bursting coffins |

||

|

See her in the angels’ choir. |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

Suffer bravely, all ye millions! |

||

|

Suffer for a better world! |

||

|

Up above the starry vault |

||

|

You’ll find a great God’s recompense. |

||

|

Gods can never be requited; |

||

|

To be like them is beautiful. |

||

|

Let grief and poverty come hither, |

||

|

And with the happy ones rejoice. |

||

|

Let rage and vengeance be forgotten, |

||

|

Forgiven be our mortal foe, |

||

|

Not one teardrop shall oppress him, |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

Let our book of debts be cancelled! |

||

|

Let all the world be reconciled! |

||

|

Brothers—above the starry vault |

||

|

God will judge as we have judged. |

||

|

Joy will sparkle in the goblets, |

||

|

In the golden blood of grapes |

||

|

Cannibals may drink sweet temper |

||

|

And desperation courage take— |

||

|

Brothers, leap from where you’re sitting, |

||

|

When the brimming glass goes round, |

||

|

Let the foam spray up to heaven: |

||

|

To the good spirit drink this toast. |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

Whom the constellations honour, |

||

|

Whom the seraph’s hymn applauds, |

||

|

Drink this glass to the good spirit |

||

|

Beyond the starry vault above! |

||

|

Courage firm in sore affliction, |

||

|

Succour where the innocent weep, |

||

|

Eternity to words of honour, |

||

|

Truth to friend and foe alike, |

||

|

Manly pride in royal presence – |

||

|

Brothers, if goods and blood it cost, – |

||

|

Crowns to those who best deserve them, |

||

|

Downfall to the lying brood! |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

Close the sacred circle tighter, |

||

|

Swear upon this golden wine: |

||

|

To be faithful to the vow, |

||

|

Swear it by the judge above! |

||

|

Rescue from the chains of tyrants, |

||

|

Kindness towards the villain too, |

||

|

Hope for those who lie on deathbeds, |

||

|

Pardon those condemned to death! |

||

|

The dead shall also join the living! |

||

|

Brothers, drink and join the song, |

||

|

Every sin shall be forgiven, |

||

|

Hell itself shall cease to be. |

||

|

Chorus |

||

|

A serene hour of departure! |

||

|

Peaceful sleep beneath the shroud! |

||

|

Brothers—and a gentle verdict |

||

|

On the dead the judge may utter! |

||

When Schiller’s poem ‘An die Freude’ (‘Ode to Joy’) first appeared in 1786, it was an immediate popular success. It soon became, as Schiller later acknowledged, ‘to some extent a folksong’.3 It was set to music over a hundred times,4 and its fame received an extra boost when Beethoven incorporated it—or more precisely, less than half of it—in the fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony. Along with ‘The Song of the Bell’, it remained Schiller’s best known poem throughout the nineteenth century; and well into the twentieth century, its popular appeal—by now inseparable from that of Beethoven’s symphony—remained undiminished. In the second half of the century, however, a reaction set in. The poem came to be regarded, especially in Germany, as at best of historical interest5 and at worst as an embarrassment: significantly, a popular edition of Schiller’s poetry, still in print,6 which includes over 150 items, omits it altogether. ‘An die Freude’ now survives, in Beethoven’s abbreviated version—and in the English-speaking world mainly in archaic or incompetent translations7—as the text of the choral section of the Ninth Symphony, whose music still manages to bring some of the poem’s emotional charge back to life. But the words, images, and concepts which first transmitted that charge to the composer are no longer an equal partner in the symphony’s overall effect—they are simply part of its archaeology. The fact that Beethoven’s famous melody is now often performed on its own, without Schiller’s text,8 is a sure sign that this text is now widely considered superfluous.

My aim in this essay is to examine the poem’s origins, ancestry, and reception, with a view to discovering why it enjoyed such immense popularity when it first appeared, what Beethoven found so attractive about it, and what kept it alive until relatively recent times. And finally, I shall ask what, if anything, it still has to offer us today.

The ’Ode to Joy’ was composed in the late summer or autumn of 1785, when Schiller, living a hand-to-mouth existence as a fugitive from his native Württemberg, at last found security and happiness in a circle of friends around Christian Gottfried Körner.9 Along with others of Schiller’s works, it was published in February 1786 as the opening item of the second issue of his periodical Thalia, with a musical setting by Körner, himself an amateur musician.10 But although the poem’s theme and mood plainly reflect Schiller’s personal experience, it is in no sense an autobiographical statement in the manner of Goethe, or even of Klopstock.11 On the contrary, its poetic currency is largely conventional. In fact, five or more poems by various authors entitled ‘Die Freude’ or ‘An die Freude’ had appeared over the previous half century, most of them personifying joy as a goddess or divine being and equating it with that feeling of elation or happiness which accompanies a life of modest virtue and cheerful conviviality among a small circle of friends.12 Schiller’s poem is full of echoes of these earlier works, from the opening line of Hagedorn’s poem (‘Freude, Göttin edler Herzen’)13 to that of Uz’s equivalent work (‘Freude, Königinn der Weisen’).14 Schiller’s metrical scheme is in fact identical with that of Uz, apart from his addition of a chorus after each verse. Several of the earlier poems belong to the Anacreontic phase of mid-eighteenth-century German poetry, which, in a light-hearted spirit, celebrated the trinity of wine, love, and friendship; the third verse of Schiller’s poem, with its references to roses and kisses, grapes and friendship, faithfully reproduces this older idiom. But the ‘Ode to Joy’ is equally indebted to another traditional class of lyric, namely the Masonic song, as performed by Freemasons at festive gatherings in celebration of their brotherhood and its beliefs; for example, Schiller’s references to the creator above the stars echo such lines as ‘Up above the starry host/Our Master rules on high’ in the Masonic songbooks of the day.15 His astronomical references likewise recall the poetry of Brockes and Haller early in the century, with its praise of the Newtonian universe and its creator. In short, precedents can be found in the lyric of the German Enlightenment for most of the motifs and images in the ‘Ode to Joy’. The poem’s originality consequently lies not so much in its detail but, as I shall try to show, in two other, more general qualities—firstly, in the rhetorical power with which the familiar material is put across, and secondly, in the remarkable concentration of eighteenth-century themes and allusions which Schiller achieves in so short a work.

But before I examine these qualities, I shall give a brief outline of the poem’s structure and development, relating it to the modes and genres of poetry current in Schiller’s time. In its original form as reproduced here, the poem consists of nine verses, each followed by a chorus; Schiller himself shortened it, in the second version published in 1805, by deleting the final verse and chorus, at the same time making minor alterations to the first verse.16 The first verse addresses joy directly as a divine being and unifying force promoting human brotherhood, and then the chorus at once expands the frame of reference to the universe at large and its benevolent creator. The second verse celebrates human friendship, with a concluding reprimand for unsociable individuals who have failed to establish a bond of friendship with others. The second chorus, like all the subsequent choruses, again enlarges the perspective to the astronomical universe and its architect, who is given different names from one chorus to the next, from ‘God’ and ‘the unknown being’ to ‘the good spirit’ and ‘the judge of the dead’. The third verse refers to joy in the third person, as the animating force in all created beings from the worm to the cherub, and as the inspiration imparted by love, wine, and friendship. (The references here to grapes and drinking prepare the way for the drinking ritual of the last three verses.) Verse four again invokes joy as a cosmic power, this time as the driving force of the physical and biological universe. The fifth verse adopts an older didactic idiom, that of allegorised abstraction, and returns to the world of human experience: joy is now coupled with personified values such as truth, virtue and faith, while the last two lines, with their reference to bursting coffins, contain a somewhat incongruous reminiscence of sepulchral poetry and the Gothic novel. The sixth verse includes a further series of abstract concepts, this time calling on those oppressed by deprivation or destructive passions to rise above their affliction in a spirit of joyful forgiveness; these hopeful and conciliatory sentiments, addressed to mankind at large, are echoed in the choruses to verses five and six. Verses seven to nine form a relatively self-contained unit: this is the climax of the poem, in which all the positive sentiments of the preceding verses become the object of joyful celebration in a fraternal company bound together by an oath of loyalty. This company rises to its feet to drink a series of toasts, first to the creator—now described as ‘the good spirit’—and then to a series of human virtues and worthy causes such as courage in adversity, succour for the innocent, freedom from tyranny, etc. The last two verses consist entirely of such toasts, culminating in a series of eschatological references to death and the Last Judgement; the formula ‘The dead shall also join the living’ ingeniously combines the traditional ‘vivat!’ formula of the salutation or toast with the idea of resurrection from the dead. This final section of the poem contains further incongruities: secular jollification combines with religious solemnity, Christian with pagan allusions, a series of moral, political, and religious values are invoked, and—with a touch of Sturm und Drang extravagance and an allusion to the voyages of discovery—we are even invited in verse seven to imagine the spectacle of wine-bibbing cannibals.

The poem was clearly intended from the start for choral performance, for its choruses are specifically labelled as such, and there are several internal references to song and music. Its moral content, its praise of the creator and his works, and its eschatological conclusion lend it affinities to the Christian hymn: it indeed refers explicitly to the seraph’s hymn and to the choir of angels. But its Anacreontic associations, its toasts, and the fraternal company addressed in the concluding verses link it no less strongly with the drinking songs of the student fraternities (‘Brothers, drink and join the song’) and—as already mentioned—with the Masonic song, in which secular conviviality and deistic religiosity traditionally come together. But for all its religious references, the sentiments and values in Schiller’s poem are basically secular: it is in fact a kind of secular hymn.

Apart from its external structure, with its regular metre, rhyme, verses, and choruses, the poem also has an internal structure in the way in which its ideas, images, and sentiments are organised. This internal organisation is largely responsible for its rhetorical power, which is one of its two most memorable features. As in many of his later poems, Schiller’s imagination follows an architectonic, spatial model:17 the unifying power of joy embraces not only present friends, but expands horizontally outwards to embrace the whole of humanity in an immense ring or circle, as in the lines ‘We embrace you, all ye millions!’ and ‘all who dwell in this great ring’. At the same time, joy extends upwards through a vertical hierarchy from the lowest forms of life to the supreme being beyond the stars. This vertical axis of height and depth, which is invoked in every chorus, and the interaction of extremes which it entails, is, of course, the stuff of Schiller’s dramatic as well as his lyrical imagination: the aesthetic modality here is that of sublimity, and both of the two varieties of sublimity later distinguished by Kant are present: on the one hand, we have what Kant calls the ‘mathematical’ sublimity of number and size, both in the ‘Millionen’ of all humanity and in the vastness of the stellar universe which transcends the limits of the imagination and fills us with awe; and on the other, we have Kant’s ‘dynamic’ sublimity of overwhelming power as the millions fall prostrate before the might of the creator (third chorus).18 Similarly, the poem includes those two sublime objects to which Kant famously refers at the end of his second Critique of 1788, namely ‘the starry heaven above me and the moral law within me’;19 for Schiller repeatedly invokes the starry heavens in his choruses, and the moral law is a constant presence in the second half of the poem. This association between joy and sublimity remained a real one for Schiller for the rest of his life; it appears once more in the concluding line of The Maid of Orleans, in which the heroine triumphs over human weakness to declare ‘Short is the pain, and eternal is the joy.’

This contrast of extremes inherent in the experience of sublimity is matched by other kinds of opposition and conflict both within this poem and between it and other early poems by Schiller. In the same issue of his Thalia which opened with the ‘Ode to Joy’, he included two poems of diametrically opposite character, namely ‘Freethinking of Passion’ and ‘Resignation’, whose mood is respectively one of nihilistic defiance and black despair. The agonistic tensions which run throughout Schiller’s work20 are also present in the ‘Ode to Joy’ itself, although in this case, they are invoked only to be decisively overcome. The all-conquering power of joy transcends or vanquishes Grief, Poverty, Rage, Vengeance, Repentance, Debts, Desperation, Affliction, Death, and even Hell itself—if only in the poetic imagination and in moments of high euphoria. It is nevertheless the extreme contrasts in which this poem abounds21—and their triumphant resolution in joyful solidarity—which lend the ‘Ode to Joy’ an exuberance and rhetorical power rarely equalled in any of the lyrical traditions which influenced it.

So much for the poem’s rhetorical power. Before I look at its other most original feature, namely its unusual concentration of eighteenth-century themes and allusions, I should like to call to mind its immediate historical context. It was written in the second half of 1785, around the mid-point of the final decade of the ancien régime. This was on the whole a propitious time in the history of European culture. There had been no major wars in continental Europe for the last twenty years; Mozart and Haydn, Reynolds and Gainsborough were at the height of their powers; Beaumarchais’ Marriage of Figaro had just caused a sensation at the Comédie Française; and Part II of Herder’s Ideas on the Philosophy of History, with its celebration of all the world’s peoples, had just been published. There was an atmosphere of expectancy in Europe: the Enlightenment felt that it had come of age, and it was time for its promises to be delivered. Only a year before, Kant had delivered an optimistic answer to the question ‘What is Enlightenment?’, predicting a further enlargement of those human liberties which enlightened rulers like Frederick the Great had inaugurated. There were, it is true, some clouds on the horizon: the affair of the necklace was about to cause serious disquiet in France; and in Germany, the Bavarian government had already begun to suppress the secret society of Illuminati, which represented the radical wing of the Aufklärung. But enlightened rulers still sat on the thrones of Prussia, Austria, and Russia, and no one could yet foresee the chaos that would engulf the continent a few years later. Schiller, who shared the prevailing mood of optimism, was already at work on Don Carlos, with its stirring appeal for political freedom. This same mood of hope and self-confidence pervades the ‘Ode to Joy’, which embodies a set of metaphysical and ethical principles derived from the popular philosophy of the time—principles which Schiller expounds more fully in his Philosophical Letters, a work which he published only a few months after the poem.

The metaphysics of both works is essentially that of Leibniz, as expounded in his Théodicée and other related writings.22 The continuous chain of being extends, as Schiller puts it, from the worm to the cherub. Evil and suffering do exist, but they are only a subordinate part of the best of possible worlds, and with time and human effort, they can be further reduced, if not wholly eliminated. Although Leibniz himself did not presume to do so, some proponents of his optimism in the later eighteenth century, such as the Berlin theologian Johann August Eberhard, had proceeded to reject the doctrine of eternal punishment, and hence the eternity of hell itself.23 Schiller appears to endorse Eberhard’s position in the last verse of his poem with the lines ‘Every sin shall be forgiven,/Hell itself shall cease to be.’ It was this same metaphysical optimism which made it impossible for Goethe’s Faust, like Lessing’s Faust before him,24 to end his career in eternal damnation.

When we try, however, to discover why Schiller came to regard joy not simply as a human emotion but as a metaphysical principle of cosmic significance, no easy answer presents itself. In his Philosophical Letters, it is love (Liebe) rather than joy (Freude) which links all beings together—a sentiment which is not uncommon in pre-critical German philosophy.25 It goes back to the Neo-Platonic doctrine of cosmic sympathy, which received a new lease of life in the eighteenth century when the success of Newton’s theory of gravity as a unitary explanation of the physical universe encouraged philosophers to look for a parallel principle in the moral world. We know that Schiller encountered such ideas in Adam Ferguson’s Institutes of Moral Philosophy, which he read in Christian Garve’s translation.26 But even in the Philosophical Letters, he endows not just love but also joy with a metaphysical significance, declaring that insight into the harmony and perfection of the natural universe fills us with joy by making us aware of our affinity with the creative spirit which produced it.27 As such, ‘Freude’ appears as an emotionally heightened, ecstatic form of love, which is itself described as a joyful emotion in others of Schiller’s early works.28

The older literature on Schiller often maintains, however, that the concept of ‘Freude’ as encountered in the many poems on joy from Hagedorn to Schiller is derived from, and a virtual synonym for, Shaftesbury’s concept of ‘enthusiasm’ as defined in his Letter Concerning Enthusiasm of 1708.29 It is true that Shaftesbury’s work was well received in Germany from an early date,30 and that the term ‘Enthusiasmus’ is often used in the Sturm und Drang period in that positive sense of creative enthusiasm associated with Shaftesbury.31 But it is hard to believe that the term ‘Freude’ had the same semantic content as ‘Enthusiasmus’ for Schiller and the other poets who sang its praises, not least because the word ‘Enthusiasmus’ continues to be used as a separate term alongside ‘Freude’32 and hardly ever appears in poetry itself. Schiller’s debt to the popular philosophy of his age is still underexplored,33 and I do not propose to explore it further here. But it does strike me as significant that, as one critic has pointed out,34 there is no evidence that Schiller encountered any of Shaftesbury’s works before his move to Weimar in 1787. Besides, the term ‘Freude’ had already acquired philosophical and even metaphysical significance before anyone had heard of Shaftesbury in Germany—not least in the writings of Leibniz, who uses it in one of the few works he wrote in German to denote that sentiment which arises out of insight into the divine wisdom of creation, and which itself promotes increased perfection, in this world and the next, among those who experience it.35 I am not suggesting here that Schiller knew this work by Leibniz, which in fact remained unpublished until after Schiller’s death.36 I am merely arguing that, by the beginning of the eighteenth century, the term ‘Freude’ already carried sufficient philosophical weight to account for its subsequent prominence in reflective poetry from Hagedorn onwards.

The apex of Schiller’s metaphysical universe is, of course, the divine being above the stars. It is not difficult to identify this being with the God of Christianity, for the poem is full of Biblical references, from the cherub who stands before God to the choir of angels, the seraph, and above all the ‘judge above’ or the judge at the end of the poem who passes judgement on the dead or resurrected. On the other hand, the poem begins with an address to joy as a goddess or ‘spark immortal’ and a daughter of Elysium, the pagan equivalent of heaven. This mingling of Christian and pagan mythology is not uncommon in post-Renaissance poetry, but by Schiller’s time, it is often a sign that all the references in question are merely symbolic expressions of basically secular beliefs and values. For in the first place, the god of the ‘Ode to Joy’ is the god of the astronomers, of natural religion, the supreme being of the deists and Freemasons. Secondly, the references to resurrection and judgement are there merely to furnish a traditional underpinning for that belief in human immortality and the rectification of injustice in the afterlife to which most of the Aufklärer, including Kant, still clung—if only as a sheet anchor for morality, as a ‘hope for those who lie on deathbeds’, as Schiller puts it, and a bulwark against despair: ‘Up above the starry vault/You’ll find a great God’s recompense.’37 And the third, and most important article of natural religion is also present: the freedom of the human will to choose between good and evil. In short, this poem is a small part of that great endeavour in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Germany to translate the human and moral substance of Christianity into a new and secular idiom which was to become that of German idealism, simultaneously conserving that substance, raising it up, and superseding it in all three senses which Hegel packs into the German verb aufheben.

But the most important part of Schiller’s natural religion, in common with that of Kant, is its ethical content. The drinking ritual at the end of the poem is not, as some critics have argued,38 an incongruous intrusion. It is a secular ceremony, akin to a Masonic gathering, in celebration above all of ethical values, which are an essential part of the young Schiller’s philosophy of universal love, and the toasts in the last two verses are all in honour of moral virtues. This coupling of joy with moral virtue is, of course, nothing new; it is to be found in all the German poems on joy from Hagedorn onwards, but in Schiller’s case, it is derived from the moral philosophy which he absorbed at the Carlsschule from his teacher Abel and from Ferguson’s treatise on ethics. The moral philosophy in question goes back to Hutcheson and Shaftesbury, both of whom saw virtue as the product of natural human benevolence;39 and the pursuit of virtue leads in turn to moral perfection and personal happiness. These ideas, once again derived from the Neo-Platonic tradition, likewise underlie Adam Ferguson’s doctrine of ‘sympathy’, to which Schiller explicitly alludes in the second chorus. In all of these eudaemonistic doctrines, virtue and happiness—which in Schiller’s poem is elevated to its fullest expression in the emotion of joy—are regarded as inseparable:40 in the happy man (or woman), the purpose of existence, indeed of the whole universe, is fully realised,41 and in moments of joy, those who experience it feel at one with the whole of creation. As Schiller puts it in his Philosophical Letters (with numerous verbal parallels to his poem): ‘There are moments in life when we are inclined to press to our bosom every flower and every distant star, every worm and every higher spirit whose existence we sense—an embrace of all of nature as our beloved.’42

Predominant among the moral virtues which the poem celebrates is that of friendship. In the mid-eighteenth century, effusive demonstrations of friendship between males, either in a small group or between individuals, is a central feature of the literature of sensibility. The young Schiller’s letters and lyric poetry—as in his poem ‘Die Freundschaft’ of 178243—perpetuate this tradition. In the latter part of the century, however, such friendship is more often expressed in larger groups or formally constituted societies such as the literary ‘Hainbund’ founded in 1773 in Göttingen.44 The Freemasons in particular became associated with the ideal of friendship, as in Lessing’s Masonic dialogues Ernst and Falk,45 and it was no doubt partly for this reason that Schiller’s poem was warmly welcomed in Masonic circles.46 The liberal and charitable aims of the Freemasons, as well as the deistic framework within which these aims were pursued, accord very well with Schiller’s poem, and especially with the drinking ritual of the last three verses. In a kind of secular equivalent of the Eucharist, the circle of friends pledges its faith in humanity and its potential for constructive moral action. And significantly, the wine they drink is drunk not for anything it represents, but for its physical effects: the young Schiller’s morality has no hint of Kantian rigorism about it, for human benevolence springs spontaneously from the psycho-physical harmony of well-adjusted human nature—and alcohol and convivial company can only enhance this process. The ideal of personal friendship is accordingly enlarged, in this poem, to encompass the entire human race47 in the cosmopolitan spirit of the Enlightenment and of German literary Humanität.

It is this wider ethical relevance which gave this poem its popular appeal from the 1780s to recent times. For it celebrates not just individual moral values such as courage, charity, and honesty, but also the political values of liberty, equality, and fraternity—although Schiller does not group these together as a trinity as happened soon afterwards in France. Liberty, as a liberal rather than a revolutionary ideal,48 is invoked in the lines ‘Manly pride in royal presence’ (verse eight) and especially ‘Rescue from the chains of tyrants’ (verse nine). In the nineteenth century, Schiller was regularly hailed as a champion of freedom, whether of the nation (as in Wilhelm Tell) or of the self-determining individual (as in the tragedies and later philosophical writings). This even gave rise, in the case of the ‘Ode to Joy’, to the myth that his original title for the poem was ‘An die Freiheit’ (‘Ode to Freedom’), later changed by the censor to ‘An die Freude’.49 In the euphoria of 1989 in Berlin, Leonard Bernstein actually conducted a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in which the word ‘Freiheit’ replaced ‘Freude’ throughout the choral section.50 This inspired one misguided Germanist51 to revive the myth of the censor’s intervention, an absurd claim which ignores not only the long tradition of earlier poems on the theme of ‘Freude’ but also the fact that Schiller himself explicitly gives the poem its present title in the covering letter with which he sent it to his publisher in 1785.52 Nevertheless, political liberty does appear in the list of ethical ideals celebrated in the poem, especially in the final verse, which Schiller deleted after events in France had invested it with unintended revolutionary overtones.53

Social and political equality are likewise commended in the poem. In the second half of the first verse, Schiller praises the power of joy to efface those distinctions which the divisive force of class conventions (‘the sword of custom’)54 imposes: ‘Beggars become princes’ brothers,/Where your gentle wings alight’. Here again, he took fright after the French Revolution, and the second version of the poem removes both the hint of violence in ‘the sword of custom’ and the suggestion of social and political upheaval implicit in the reference to beggars by recasting the lines in question as follows:

Your magic spells have reunited,

What strict custom split apart;

Every man becomes a brother,

Where your gentle wings alight.

But it is the last, and most neglected,55 of the three aspirations of the revolutionary era—namely fraternity—which is by far the most prominent in Schiller’s poem in both its versions. The word ‘brother’ occurs no fewer than eight times, both in the sense of personal friendship as pledged in the German ceremony of ‘drinking brotherhood’ and in that of universal brotherhood as the supreme ideal of the Enlightenment. In the first of these senses, Schiller’s references to brotherhood reflect that ideal of personal friendship which runs through the literature of sensibility in Germany; such friendship defines itself in those years as a middle-class virtue, as the opposite of aristocratic insincerity and courtly intrigue,56 an opposition which is hinted at in verse eight of the poem (‘Manly pride in royal presence/ [...] Downfall to the lying brood!’). In its second, universal sense, the ideal of fraternity as human brotherhood pervades the entire poem, and the principal function of God as ‘a loving father’ is to provide a head for the fraternal family of mankind (and, in a cosmic sense, of all created beings).57 Although this family exists as yet only as an ideal, it may one day be realised in practice (‘Suffer bravely, all ye millions!/Suffer for a better world!’). In short, the poem embodies the basic political as well as moral ideals of the Enlightenment; but they are formulated in such general terms that no specific political programme can be abstracted from them.

The critical reception of the poem has not been helped by the fact that Schiller himself, in 1800, condemned it in no uncertain terms. As he wrote to Körner:58

[The Ode to] Joy [...] is also thoroughly faulty, according to my present taste, and even if it does recommend itself by a certain emotional fire, it is nevertheless a bad poem and signifies a stage of education which I certainly had to leave behind me in order to accomplish anything worthwhile. But because it appealed to the defective taste of its time, it received the honour of becoming something of a folksong. Your liking for this poem may be based on the period of its origin; but this also lends it the only value it has, and it has it only for us, and not for the world or for the art of poetry.

In other words, its only value is personal and particular, as a reminder of a moment of happiness shared by Schiller, Körner, and their circle. Schiller had several reasons for dismissing the poem in this way. I have already mentioned his unease over certain lines which, after 1789, might be construed in a revolutionary sense. It is also possible that the references to hell, resurrection, etc. in the final verse which he deleted in the second edition sounded too exclusively Christian for his liking in later years. And the eudaemonistic ethics of cosmic sympathy alluded to throughout the poem must have struck him as naive and old-fashioned after his studies of Kant’s moral philosophy in the early 1790s.59 But above all, he rejected the poem for aesthetic reasons. Its popular tone and direct appeal to the emotions reminded him of the popular ballads and Masonic songs which he now openly despised;60 and in describing the work as a Volkslied, he was implicitly putting it in the same class as the poems of Gottfried August Bürger, with their down-to-earth echoes of the folksong, which he condemned in his scathing review of the latter’s works in 179161—a review whose harshness owes as much to his disapproval of his own early poetry as to his distaste for that of Bürger. His classical aesthetics of the 1790s demanded reflective distance, refinement, and emotional restraint in poetry, and the ‘Ode to Joy’ now appeared far too immediate, homespun, and effusive for his liking.

The faults which Schiller found in it—its popular idiom, lack of refinement, and autobiographical origins—are not necessarily faults by today’s standards. But even today, it is difficult not to find deficiencies in the poem. It lacks that combination of simplicity and originality which we admire in Goethe’s lyric, and it has none of the complexity and multiplicity of meaning we associate with Hölderlin or Rilke. Its idealistic optimism and rhetorical enthusiasm are alien to our age, and for historical reasons, they are viewed with particular suspicion in Germany. As already mentioned, it also draws heavily on earlier poems, both in theme and in expression: many of its pronouncements are commonplaces, or even clichés.62 It is full of incongruous images and allusions, and has been described by one critic as a confused ‘jumble of pietist emotion, Sturm und Drang ranting and Aufklärung lore’.63 Yet it does have a dynamic coherence, as I have tried to show: but its organising principle is not so much logical as cumulative and climactic, as its joyful exuberance expands outwards and upwards to embrace an ever wider range of experience, and as its tempo accelerates with a concluding series of one-line acclamations. This cumulative character, this richness of reference, inevitably generates incongruities, but it is at the same time one of the poem’s greatest strengths—even by Schiller’s own classical standards. For in that same review in which he condemns Bürger’s poems, he defines the task of poetry as follows: ‘It ought to collect together the manners, character, and entire wisdom of its age in its mirror, and create, with its idealising art, a model, refined and ennobled, for its century from the century itself.’64

The ‘Ode to Joy’ fulfils the spirit of this requirement more completely than any other German lyric poem of the half-century from 1740 to 1790 that I know. It is a microcosm and summation of the culture and aspirations of the German Enlightenment, from sensibility and Anacreontic frivolity to the Sturm und Drang and Gothic revival, from Leibnizian metaphysics to Hutchesonian moral sense, from Aufklärung didacticism and Newtonian astronomy to Klopstockian fervour and pietistic devotion, from the literature of travel to the cosmopolitan secret societies and the declarations of the rights of man. Its incongruities are those of the age and culture which produced it. But when Schiller defined the task of poetry in 1791, he was aware that the age which he now called on poetry to represent was no longer the age he had known in 1785: the political revolution in France and the intellectual revolution of the critical philosophy had generated new problems and new attitudes which called for a new poetic currency, even if popular poetry continued to employ the old one.

I therefore conclude that the historical importance of Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’ is greater than its critics, from Schiller himself onwards, have generally acknowledged. As for its relevance today, such life as it still possesses it owes almost entirely to Beethoven’s setting of 1824. Beethoven knew and loved the poem from his years in Bonn onwards, and he planned to set it to music as early as 1793.65 Several attempts remained fragments or no longer survive, and when he finally composed his choral symphony, the text he had before him was Schiller’s second version, which ends rather lamely in the middle of the drinking ritual at the end of the eighth chorus. The poem was, of course, still too long for Beethoven’s purposes, and he retained only those parts—namely the first three verses and the choruses to verses one, three, and four—which he considered most important. He also changed their order by grouping the verses together as a separate body, followed by the choruses as a second group including two repeats of the first verse.66 The effect of this change was to accentuate Schiller’s polarity between the earthly hierarchy, united in joy, and the mighty creator of the universe before whom the millions prostrate themselves—in short, to accentuate that contrast of height and depth, power and powerlessness, which is inherent in the aesthetic experience of sublimity. Beethoven, who can rarely resist the heroic mode, also brings in the chorus of verse four with its lines ‘Run, ye brothers, on your courses/ Joyful, as a conquering hero’ as a link between his two main sections, accompanying it with a triumphant march (marked alla marcia) as humanity proceeds towards its goal of joyful brotherhood.67 The concluding repeat of the first verse and its chorus rounds off Beethoven’s text as a more tightly unified entity than Schiller’s longer, enumerative poem, and the penultimate line of the first verse in its revised form, ‘Every man becomes a brother’, re-emphasises the ideal of human brotherhood. It is this central ideal of the Enlightenment, and its sublime representation in Schiller’s poem, that inspired the last movement of Beethoven’s symphony.

To do justice to Beethoven’s setting would require more space and greater competence than I can lay claim to. I shall simply conclude with a few comments on the reception of Schiller’s text in Beethoven’s setting and its residual significance today. In the years immediately before and after the revolution of 1848, the choral symphony was acclaimed by various liberal and radical voices, from Bruno Bauer to the young Richard Wagner.68 Surprisingly, it already possessed that strong association with the cause of liberty which it has never entirely lost,69 despite the fact that Schiller’s overt allusions to liberty occur only in those verses of the poem which Beethoven left out. The symphony was adopted by socialist groups in the early decades of the twentieth century as an anthem of proletarian solidarity, and was regularly performed by workers’ choirs in the 1920s.70 In more recent times, its theme of fraternity has usually—and with more justification—been interpreted in terms of international rather than proletarian co-operation (‘Let all the world receive this kiss’); and Beethoven’s melody, with—and increasingly often without—Schiller’s text, has been adopted at various times as an anthem by the Council of Europe, by NATO, by the Olympic team of the two Germanies in the 1950s and 60s, and as the preferred choice of a sizeable minority of Germans in 1990 for a new national anthem.71 Some of these associations are distinctly odd: universal brotherhood is not the most obvious aspiration of a military alliance, and the ‘Ode to Joy’ is not perhaps the most suitable anthem for the European Union, at least at the present moment—hence, no doubt, the current preference for instrumental renderings of Beethoven’s melody. But at a more fundamental level, this preference is probably motivated by a distrust of words and concepts which have become hackneyed by overuse and tainted by misuse. More disquietingly, indifference towards them can easily be bred once the ideals they represent—freedom from oppression, equality before the law, and international co-operation—have become realities, at least for the fortunate majority in the western world, or when they are enforced by the deadening discipline of political correctness, which devalues common sense and inhibits spontaneity. These ideals soon recover their life and emotional content, of course, when they are seriously challenged, or when they are rescued from grave danger, as happened at the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the liberation of Kosovo in 1999. But fortunately, there is another alternative: we can at any time re-experience something of their original power by enjoying the major works of art which they inspired, such as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—and also perhaps, with a little more effort of the historical imagination, the poem which inspired Beethoven to write it.

1 An earlier version of this chapter was originally published as ‘Friedrich Schiller. “An die Freude”. A Reappraisal’, in Peter Hutchinson (ed.), Landmarks in German Poetry (Oxford, Berne, Berlin, etc.: Peter Lang, 2000), pp. 73–96.

2 The text is that of the original version published in 1786, as reproduced (with spelling and punctuation largely modernised), in Friedrich Schiller, Sämtliche Werke (henceforth SW), ed. by Gerhard Fricke and Herbert G. Göpfert, 5 vols, 7th edn (Munich: Hanser, 1984), I, 133–36.

3 Schiller to Körner, 21 October 1800, in Schillers Werke, Nationalausgabe (henceforth NA), ed. by Julius Petersen and Gerhard Fricke (Weimar: Böhlau,1943-), XXX, 206f.).

4 See the editors’ commentary in Friedrich Schiller, Werke und Briefe, Frankfurt edition (henceforth FA), ed. by Otto Dann and other hands, 12 vols (Frankfurt a. M.: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, 1988–2004), I, 1038; Schiller-Handbuch, ed. by Helmut Koopmann (Stuttgart: Kröner, 1998), p. 311; Julius Blaschke, ‘Schillers Gedichte in der Musik’, Neue Zeitschrift in der Musik (1905), 397–401.

5 See Schiller-Handbuch, p. 889.

6 Friedrich Schiller, Gedichte, ed. by Norbert Oellers (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2009).

7 The best known version is still the nineteenth-century rendering by Lady Natalia Macfarren, reproduced in C. P. Magill, ‘Schiller’s “An die Freude”’, in Essays in German Language, Culture and Society, ed. by Siegbert S. Prawer, R. Hinton Thomas and Leonard Forster (London: Institute for Germanic Studies, 1969) pp. 36–45 (pp. 37f.). Typically marred by errors and infelicities is that in Nicholas Cook, Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 109.

8 See Andreas Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie. Die Geschichte ihrer Aufführung und Rezeption (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1993), pp. 296ff.

9 See FA I, 1036; also Schiller-Handbuch, p. 13.

10 See Schiller-Handbuch, p. 750; also Schiller to Georg Joachim Göschen, 29 November 1785 and 23 February 1786 in NA XXIV, 28f. and 35f.

11 Cf. Hans Mayer, ‘Schillers Gedichte und die Tradition deutscher Lyrik’, in Jahrbuch der Deutschen Schiller-Gesellschaft, 4 (1960), 72–89 (p. 87).

12 See FA I, 1037 and Franz Schulz, ‘Die Göttin Freude. Zur Geistes- und Stilgeschichte des 18. Jahrhunderts’, Jahrbuch des Freien Deutschen Hochstifts (1926), 3–38 (pp. 5–27).

13 Text in Schulz, ‘Die Göttin Freude’, pp. 5f.

14 Text in ibid., pp. 19f.

15 See Hans Vaihinger, ‘Zwei Quellenfunde zu Schillers philosophischer Entwicklung’, Kant-Studien, 10 (1905), 373–89 (p. 388); also Gotthold Deile, Freimaurerlieder als Quellen zu Schillers Lied ‘An die Freude’ (Leipzig: Verlag Adolf Weigel, 1907), pp. 88–112.

17 Cf. his use of an imaginary landscape of varying heights and depths in his poem ‘Der Spaziergang’ (‘The Walk’) in SW I, 228–34 and his comments on the poetic function of landscape in his review of Matthisson’s poems in SW V, 997f. See also Martin Dyck, Die Gedichte Schillers (Berne: Francke, 1967), pp. 60 and 73.

18 See Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft §§ 25–29, in Kant, Gesammelte Schriften, Akademie-Ausgabe (henceforth AA), (Berlin: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1900–), V, pp. 248–78; cf. also Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie, p. 226.

19 Kant, AA V, 161.; cf. Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie, p. 233.

20 See Günter Schulz, ‘Furcht, Freude, Enthusiasmus. Zwei unbekannte philosophische Entwürfe Schillers’, Jahrbuch der Deutschen Schillergesellschaft, 1 (1957), 103 and 113–19.

21 Cf. Hans H. Schulte, ‘Werke der Begeisterung’. Friedrich Schiller—Idee und Eigenart seines Schaffens (Bonn: Bouvier, 1980), p. 271.

22 Cf. SW V, 357 and editors’ commentary in ibid., pp. 1094 and 1098.

23 In his Neue Apologie des Sokrates oder Untersuchung der Lehre von der Seligkeit der Heiden, 2 vols (Berlin: Nicolai, 1772–78); cf. Lessing’s riposte to this work in his essay ‘Leibniz von den ewigen Strafen’, in Lessing, Sämtliche Schriften (henceforth LM), ed. by Karl Lachmann and Franz Muncker, 23 vols (Stuttgart: Göschen, 1886–1924), XI, 461–87.

24 Cf. Lessing, LM III, 384–90.

25 For further details, see Wolfgang Riedel, Die Anthropologie des jungen Schiller (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1985), pp. 182–98.

26 See David Pugh, Dialectic of Love. Platonism in Schiller’s Aesthetics (Montreal, QC: Queen’s-McGill University Press, 1996), pp. 173–76.

27 SW V, 344f.

28 See, for example, the poem ‘Die Freundschaft’ (1782), in SW I, 91ff., with its reference to the ‘ewgen Jubelbund der Liebe’ and its ‘freudemutig’ enthusiasm.

29 See, for example, Schulz, ‘Die Göttin Freude’, pp. 7 and 31f.; also Ernst Cassirer, ‘Schiller und Shaftesbury’, Publications of the English Goethe Society, 11 (1935), 35–59 (p. 52).

30 See, for example, Leibniz’s favourable reception of Shaftesbury in Leibniz, Philosophische Schriften, ed. by C. I. Gerhardt, 7 vols (Berlin: Weidmann:, 1875–90), III, 424f.

31 Cf. Schulte, ‘Werke der Begeisterung’, passim and ibid., ‘Zur Geschichte des Enthusiasmus’, Publications of the English Goethe Society, 39 (1969), 85–122.

32 See, for example, SW V, 344 and 350.

33 Cf. Wolfgang Riedel’s comments in Schiller-Handbuch, pp. 155f.

34 Ibid., p. 164.

35 Leibniz, ‘Von der Glückseligkeit’, in Philosophische Schriften, ed. by Hans-Heinz Holz and other hands, 4 vols in 6 (Frankfurt a. M.: Insel: 1965–92), I, 391–401 (p. 396).’it follows from this that, the more one understands the beauty and order of God’s works, the more one enjoys delight and joy, and of such a kind that one becomes oneself more enlightened and perfect and, by means of the present joy, secures the joy of the future too.’

36 See the editor’s comments in Leibniz, Philosophische Schriften, I, 389f.

37 Cf. Pugh, Dialectic of Love, pp. 178f.

38 See, for example, Magill, ‘Schiller’s “An die Freude”’, p. 42.

39 Cf. Riedel, Die Anthropologie des jungen Schiller, pp. 125 and 131.

40 Cf., Schiller’s Carlsschule address ‘Virtue Considered in its Consequences’ in SW V, 280–87 (p. 282).

41 Goethe expresses this same belief in his essay ‘Winckelmann’ of 1805, in Goethes Werke, Hamburg Edition, ed. by Erich Trunz (Hamburg: Wegner, 1948—64), XII, 96–129 (p. 98).

42 SW V, 350.

43 SW I, 91ff.

44 Cf. Schulte, ‘Zur Geschichte des Enthusiasmus’, p. 104; see also the article ‘Freundschaft’ in the Lexikon der Aufklärung, ed. by Werner Schneiders (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1995), pp. 139–41.

45 On the significance of friendship in this work, see Peter Michelsen, ‘Die “wahren Taten” der Freimaurer. Lessings Ernst und Falk’, in Michelsen, Der unruhige Bürger. Studien zu Lessing und zur Literatur des 18. Jahrhunderts (Würzburg: Konigshausen & Neumann, 1990), pp. 137–59 (pp. 157ff.).

46 Cf. Zerboni di Sposetti to Schiller, 14 December 1792, in Schiller, NA XXXIV/, 208. Despite numerous approaches by Freemasons, Schiller resolutely refused to join the order himself; see Deile, Freimaurerlieder, pp. 20–30 and Hans-Jürgen Schings, Die Brüder des Marquis Posa. Schiller und der Geheimbund der Illuminati (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1996), pp. 108f.

47 Cf. T. J. Reed in the Schiller-Handbuch, p. 13.

48 Cf. Rudolf Dau, ‘Friedrich Schillers Hymne “An die Freude”. Zu einigen Problemen ihrer Interpretation und aktuellen Rezeption’, Weimarer Beiträge, 24 (1978), Heft 10, 38–60 (pp. 43 and 50).

49 See Gottfried Martin, ‘Freude Freiheit Götterfunken. Über Schillers Schwierigkeiten beim Schreiben von Freiheit’, Cahiers d’Études Germaniques, 18 (1990), 9–18 (9f.); cf. Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie, pp. 320f.

50 Schiller-Handbuch, p. 181; also Martin, ‘Freude Freiheit Götterfunken’, p. 9.

51 Martin, ibid..

52 Schiller to Göschen, 29 November 1785, in Schiller, NA XXIV, 29.

53 Cf. Schiller’s circumstantial condemnation of the French Revolution in his conversation of 1793–94 with Friedrich Wilhelm von Hoven, in Schiller, NA XLII, 179.

54 On the political significance of the term ‘Mode’ (custom), see Hans Mayer, ‘Neunte Symphonie and Song of Joy’, in Mayer, Ein Denkmal fur Johannes Brahms. Versuche über Musik und Literatur (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1983), pp. 28–39 (pp. 28ff.).

55 See the article ‘Fraternity’ in The Blackwell Companion to the Enlightenment, ed. by John W. Yolton and other hands (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), pp. 173f.

56 See the article ‘Freundschaft’ in the Lexikon der Aufklärung, ed. Schneiders, p. 140; also the article ‘Friendship’ in the Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment, ed. by Alan Charles Kors, 4 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), II, 91–96.

57 Cf. Schiller’s remarks on the family of mankind in his address ‘Virtue Considered in its Consequences’ (1780), in SW V 283; also Riedel, Die Anthropologie des jungen Schiller, p. 177.

58 See note 3 above; cf. also Körner’s reply defending the poem, in Schiller, NA XXXVIII/1, 393.

59 Cf. the editor’s comments in Schiller, FA I, 1039.

60 See, for example, Schiller’s letters to Goethe, 24 May 1803, to Körner, 10 June 1803, and to Wilhelm von Humboldt, 18 August 1803, in NA XXXII, 42, 45, and 63.

61 SW V, 970–85.

62 Cf. Dyck, Die Gedichte Schillers, p. 10; also ibid., ‘Klischee und Originalität in Schillers Gedichtsprache’, in Tradition und Ursprünglichkeit. Akten des III. Internationalen Germanisten-Kongresses 1965 in Amsterdam, ed. by Werner Kohlschmidt and Herman Meyer (Berne and Munich: Francke, 1966), pp. 178f.

63 Magill, ‘Schiller’s “An die Freude”’, p. 42.

64 SW V, 971.

65 See the Schiller-Handbuch, p. 179; Magill, ‘Schiller’s “An die Freude”’, p. 39; and Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie, p. 225.

66 For a detailed account, see Eichhorn, pp. 230–35.

67 Ibid., p. 271.

68 Ibid., pp. 307–12.

69 Cf. Martin’s flawed attempt to renew this connection (note 48 above).

70 Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie, pp, 296 and 320–26.

71 See Schiller-Handbuch, p. 181 and Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie, pp. 296f.