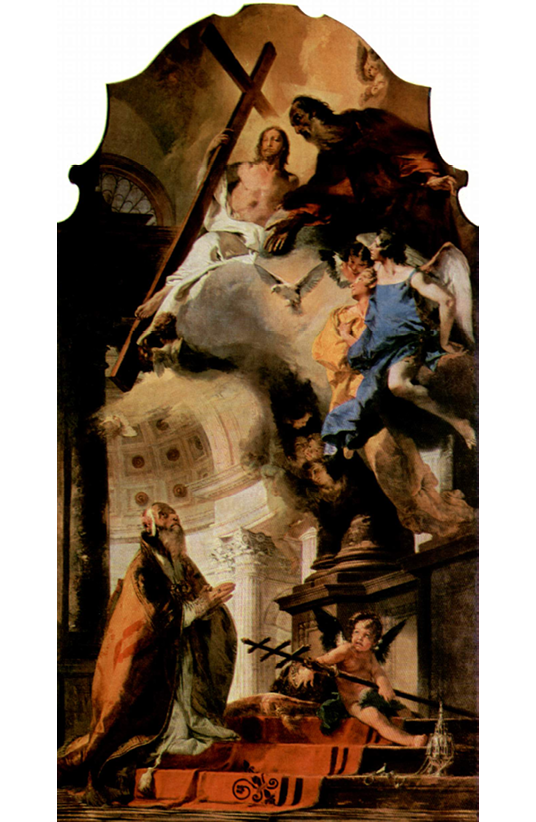

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Pope St Clement Adoring the Trinity (1737–1738), oil on canvas, Alte Pinakothek, Munich. Photograph by Bot (Eloquence) (2005), Wikimedia, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giovanni_Battista_Tiepolo_016.jpg

4. The Rationalisation of the Holy Trinity from Lessing to Hegel1

© 2021 Hugh Barr Nisbet, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0180.04

The subject of this essay is the rationalisation of religious mysteries, especially that of the Holy Trinity, in German thought between the early Enlightenment and the later stages of philosophical Idealism.2 The wider context of this development is, of course, the perennial debate on the nature of the Trinity which runs throughout the Christian era. But its more immediate context is that transitional period in early modern thought during which philosophers as well as theologians made considerable efforts to construct speculative, rational explications of the central doctrines of the Christian religion.

Rational (or natural) theology has, of course, played a significant part in Christian thinking since Patristic times. The attempts of the Church Fathers to explicate the nature of the divine being drew freely on secular philosophy, especially that of Plato and Neo-Platonism. But all such attempts—unless they were prepared to incur the risk of heresy—stopped short of trying to demonstrate the truth of such mysteries as the Trinity or the Atonement by rational means. There was, on the other hand, never any problem with such basic truths of natural religion as the existence of God and the immortality of the human soul; the Aristotelian theology of the Middle Ages, for example, was always ready to supply rational demonstrations of these. But for orthodox believers, Church authority and Scriptural revelation, rather than rational explanation, remained the principal guarantors of the truth of the central mysteries. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, as secular criteria of truth asserted their claims ever more vigorously and cosmological proofs of God’s existence in the Aristotelian tradition came under increasing attack,3 rational theology in the Platonic (or ontological) mode underwent one of its periodic revivals; it was redeveloped by various thinkers from the Cambridge Platonists to the German Idealists in order to place the central Christian doctrines on a sounder philosophical basis and to defend them against secular attitudes which were perceived as implicitly or explicitly hostile to Christianity.4 Such initiatives invariably involved some degree of accommodation or compromise with secular thought, and the risk of relapsing into time-honoured heresies such as pantheism was never far away. In these developments, as this essay will argue, Lessing’s reflections on the Holy Trinity mark a crucial stage. They point ahead to the natural theology of German Idealism and to the philosophy of history of Hegel.

Since its official adoption by the Council of Nicaea in AD 325, the doctrine of the Holy Trinity (tres Personae in una Substantia) has repeatedly been a focus of controversy.5 This is hardly surprising. Not only does it deal with such fundamental theological issues as the essential nature of God and his relationship with the world; it also presents itself as a mystery, but at the same time, by employing concepts associated with familiar areas of experience and regularly encountered in rational discourse (person, father, son, spirit, and the related term logos), it has seemed from the beginning to invite philosophical analysis. The Trinitarian controversies which form the immediate background to Lessing’s interest in this topic occurred during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and involved the Socinian, Arian, and Unitarian heresies.6 These controversies became acute in Germany during Lessing’s lifetime as both critics and apologists of religion applied the methods and concepts of philosophical rationalism to traditional Lutheran theology. Since the relationship between philosophy and theology was one of Lessing’s chief preoccupations throughout his life, he followed the relevant debates with interest and formulated his own views on the Trinity on several occasions. The first stage of this enquiry will be to examine his main observations on the subject, with brief comments on their specific context in the history of German thought.

Lessing’s earliest surviving reference to the Trinity is an oblique one, in the fragment Thoughts on the Moravian Brethren of 1750. He declares: ‘I consider Christ [here] merely as a teacher illuminated by God. But I reject all the dreadful consequences which maliciousness might deduce from this statement.’7 As his disclaimer indicates, he is fully aware that the view he expresses is unorthodox; with its implicit denial of Christ’s equality of substance with the Father, it in fact embodies the Arian (or Unitarian) heresy, and implicitly calls the Trinity itself into question.

But Lessing—himself the son of a clergyman—took theology much too seriously to stop at this point. For not long afterwards, he made a systematic attempt to demonstrate the doctrine of the Trinity with the help of Wolffian and Leibnizian metaphysics. His conclusions are embodied in the posthumously published fragment The Christianity of Reason, which was probably written in 1753.8 It has been suggested that this fragment was influenced, among other things, by his reading of Johann Thomas Haupt’s work on the Holy Trinity, a substantial volume which, from a position of Lutheran orthodoxy, enumerates and seeks to refute all rational explanations of the Trinity from the Scholastic period to the present.9 This little-known work, which is an important source on philosophical debates of the Trinity in mid-eighteenth-century Germany, was favourably reviewed in the Berlinische Privilegierte Zeitung of 28 December 1751, and the review, which has traditionally been attributed to Lessing, appears in all major editions of his works. But as Karl S. Guthke has shown, there is no evidence whatsoever that this review—like most other reviews of the early 1750s included in editions of Lessing’s works—was in fact written by him; and even if he did write it, there is no indication that he read more than the first few pages of the book, for the review consists almost entirely of near-verbatim extracts from the author’s preface.10

Be that as it may, the young Lessing was undoubtedly familiar with the attempts of at least some writers to rationalise the Trinity. Leibniz, in his Théodicée—which Lessing appears to have studied by 1754 at the latest11—refers to two of these, while himself defending the orthodox Lutheran view that the central mysteries of Christianity are above, but not contrary to, reason. That is, they can be shown to be free from internal contradiction, even if their truth cannot be conclusively demonstrated. The passage in question runs as follows:12

he who proves something a priori explains it by the efficient cause; and he who can furnish such reasons in an exact and sufficient manner is also in a position to comprehend the thing in question. That is why the scholastic theologians blamed Raymond Lull for undertaking to demonstrate the Holy Trinity by means of philosophy. [...] and when Bartholomew Keckermann, a well-known reformed author, made a very similar attempt on the same mystery, he was no less blamed by some modern theologians. Thus those who seek to explain this mystery and render it comprehensible will be blamed, whereas praise will attach to those who attempt to defend it against the objections of its adversaries.

The rationalisations of Lull and Keckermann to which Leibniz refers follow a pattern which was first established in the De Trinitate of St Augustine. Augustine insists that the nature of the Trinity is ultimately incomprehensible, but (not unlike Leibniz) he also maintains that it is both possible and necessary to defend it against unbelievers or detractors.13 He therefore tries, with the help of images and analogies based on the operations of the human mind, to render it at least to some extent intelligible, and formulates his conclusions with the help of Aristotelian logic and concepts drawn from Neo-Platonic philosophy. For example, the mind consists of the separate faculties of memory, understanding, and will; yet all three—like the Trinity—are one.14 Or as he puts it on another occasion, ‘there is a certain image of the Trinity: the mind itself, its knowledge, which is its offspring, and love as a third; these three are one and one substance. The offspring is not less, while the mind knows itself as much as it is; nor is the love less, while the mind loves itself as much as it knows and as much as it is.’15 A few theologians (including those mentioned by Leibniz)16 are more ambitious, and attempt—at the risk of being condemned as heretics—to develop Augustine’s formulas into a full deductive demonstration of the Trinity. The basic outline of such deductions, which change little (except in frequency) from the Scholastic period to the eighteenth century, is as follows. God’s understanding being necessarily perfect, must have a perfect object; and since God is infinitely good, he must also will the objective existence of his own perfection, which he ‘eternally begets’ in the form of the Son. The Holy Spirit—regularly described since Patristic times as the vinculum or bond of love between Father and Son17—is then defined in terms of the necessary relation between these two Persons as the subjective and objective manifestations of God.

In Lessing’s early years, a deduction of this kind had been tentatively suggested by the leading Wolffian among Lutheran theologians, Siegmund Jacob Baumgarten (the elder brother of the aesthetician Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten). Like most rationalist philosophers of the time, Baumgarten took it for granted that God’s existence as a necessary and perfect being can be deduced by reason. But he then further argued that the cognitive and conative aspects of God’s self-consciousness, namely ‘God’s most perfect conception of himself’ and ‘God’s most perfect inclination towards himself’ acquire objective existence as the Son and the Holy Spirit respectively:18

For if the complete inclination or determination of the divine will gives reality or existence to the objects conceived of, while God necessarily has a conception of himself and is also necessarily wholly inclined towards himself, it follows that this conception and inclination of God will appear to exist in its own right, because it would otherwise, without the reality of both these objects, not be the most perfect possible.

Baumgarten was nevertheless careful not to offend Lutheran orthodoxy; for he pointed out that, although he did claim demonstrative certainty for his deduction of God’s necessary existence, he made no such claim for his deduction of the Trinity, which he regarded as purely speculative and in no way as a substitute for revelation.19 It is highly probable that the young Lessing was familiar with these ideas, not only in view of his intensive studies of Wolffian philosophy during his early years,20 but also because his friend Christian Nicolaus Naumann explicitly refers to Baumgarten in the letter of 1753 in which he summarises the content of Lessing’s fragment The Christianity of Reason.21

The main elements of Lessing’s deduction of the Trinity are contained in the following extract from that work (Lessing’s paragraph numbers are omitted for the sake of readability):22

To represent, to will, and to create are one and the same for God. One can therefore say that everything which God represents to himself, he also creates.

God can think of himself in only two ways; either he thinks of all his perfections at once […] or he thinks of his perfections discretely [...]

God thought of himself from eternity in all his perfection; that is, God created from eternity a being which lacked no perfection that he himself possessed.

This being is called by Scripture the Son of God, or what would be better still, the Son God [...]

The more two things have in common with one another, the greater is the harmony between them [...]

Two such things are God and the Son God, or the identical image of God; and the harmony which is between them is called by Scripture the spirit which proceeds from the Father and Son. [...]23

God thought of his perfections discretely; that is, he created beings each of which has something of his perfections [...]

All these beings together are called the world.

The most novel feature of Lessing’s argument—apart from his substitution of the Leibnizian concept of ‘harmony’ for the traditional vinculum of love, with its more affective associations, between Father and Son—is that he deduces not only the generation of the Son, but also the creation of the universe, from his initial premise that thought and creation are identical for God. One of the implications of this premise is that God’s actions are governed by some kind of metaphysical necessity; and this, of course, is difficult to reconcile with the orthodox doctrine of the absolute freedom of the divine will (especially in the act of creation). Leibniz was aware of this difficulty, and he duly distinguished between the moral necessity underlying God’s choice of the best of possible worlds and the metaphysical necessity inherent in deterministic systems like that of Spinoza, from which, in keeping with his frequent professions of orthodoxy, he always took care to distance himself. But determinism is never far away from his, or Wolff’s, metaphysical optimism; and Lessing, who was himself to draw deterministic conclusions from it in his later years,24 already brings out some of these implications in The Christianity of Reason.25 This can be seen not only from the frequency with which the verbs müssen (‘must’), and können (‘can’) with a negative, appear in the fragment.26 It is even more evident from the fact that Lessing attributes the same kind of necessity to the (temporal) creation of the universe as he does to the (eternal) generation of the Son. This near-equation of the two processes, as will become apparent later, is a step of major significance for philosophical interpretations of the Trinity after Lessing’s death.

All of these developments are the inevitable result of the attempt to demonstrate the doctrine of the Trinity by rational means. For logical necessity, when applied to physical or metaphysical realities, becomes indistinguishable from physical or metaphysical necessity; and if the same mode of necessity applies to both transcendental and immanent realities, the distinction between transcendence and immanence—itself essential to that distinction between the divine and human aspects of Christ with which Lessing had struggled as early as 1750—becomes increasingly difficult to sustain.

We do not know for certain why Lessing failed to complete The Christianity of Reason. It is, however, probable that Moses Mendelssohn, whom he first met in 1754, dissuaded him from doing so (as Lessing indicates in a letter to his old friend twenty years later).27 It may well be that Mendelssohn, as a Jew, defended his own Unitarian conception of God with enough eloquence to persuade Lessing to abandon his own Trinitarian deduction—at least for the time being.28 Lessing does, however, return to his idea of a necessary relation—or even identity—between God’s thoughts and their object in the fragment On the Reality of Things outside God, probably composed in Breslau in 1763 in the course of his studies of Spinoza. From this necessary relation, he draws the following inference (which clearly has some affinity with Spinoza): ‘if, in the concept which God has of the reality of a thing, everything is present that is to be found in its reality outside him, then the two realities are one, and everything which is supposed to exist outside God exists in God.’29 It is true that there is no mention on this occasion of the Holy Trinity. But the fragment of 1763 plainly reinforces that tendency which was already present in The Christianity of Reason to regard the created universe as no less necessary a consequence of the divine nature than the latter’s internal divisions.

Lessing’s views on the Trinity during the twenty years between The Christianity of Reason and Andreas Wissowatius’s Objections to the Trinity of 1773 (in which he gives a favourable assessment of Leibniz’s defence of the Trinity against the Socinian heresy) are difficult to determine, because the evidence is extremely scant. It is safe to say, however, that they are unlikely to have been any more orthodox than before. It is common knowledge, however, that his views on Lutheran orthodoxy, and on the doctrine of the Trinity in particular, underwent a major change in 1771—probably as a result of his studies of Leibniz soon after his move to Wolfenbüttel.30 (He may also have been anxious, of course, to establish his credentials as a sincere Christian in advance of his publication of the notorious ‘Fragments’ of Reimarus.) Consequently, when he edited and republished Leibniz’s orthodox defence of the Trinity against the Socinian Wissowatius in 1773, he expressed wholehearted admiration for it.31 He admired it, moreover, not just for its philosophical acumen, but also, as he now declared, because he had come to believe that the orthodox defence of the Trinity as a mystery not fully accessible to reason, yet free from internal contradiction, is a more defensible philosophical position than the half-baked Socinian doctrine that Christ, though merely human and not consubstantial with God, nevertheless deserves to be worshipped. His respect for orthodoxy—especially as defended by Leibniz—was undoubtedly increased around that time by his polemical engagement with the so-called Neologists or rational theologians such as Eberhard, Teller, and Töllner;32 these theologians, while still claiming to be Christians, either played down the doctrine of the Trinity or rejected it altogether as incapable of rational proof. Lessing had much less respect for theologians of this complexion than for the Unitarian Adam Neuser, whose conversion from Christianity to Islam he defended in 1774.33 In all of these cases, his regard for intellectual honesty and philosophical rigour seems a more important factor in his assessment of Trinitarian thinking than any personal commitment to orthodox Lutheranism—despite the fact that he continues to treat the latter with respect throughout the rest of his life.

Lessing’s views on the Trinity during his last years, like his views on religion in general, are marked by ambiguity, scepticism, and experiment. It is nevertheless likely that, when he describes the doctrine of the Trinity as ‘complete nonsense’ in a letter to Mendelssohn in 1774,34 this extreme formulation is at least in part a concession to the anti-Trinitarian views of his Jewish friend; for he was soon to try once again, in The Education of the Human Race, to rationalise the Trinity in a manner similar to his early attempt in The Christianity of Reason. The main cause of his uncertainty, of course, is not so much the doctrine of the Trinity as such; it is the difficulty he had always had, since his earliest statement on the subject in 1750, in relating it to the historical personage of Jesus Christ and the latter’s claim to consubstantiality with the deity.35 All of his remarks on the Trinity in the later 1770s—with the notable exception of The Education of the Human Race—relate to this difficulty, which underlay his intensive studies of the origins of the gospels in 1777–78. His main work on the subject, the posthumous New Hypothesis on the Evangelists Considered as Purely Human Historians, concludes that the earliest versions of the gospels, and the testimony they contained of those who knew Christ personally, presented him merely as a human being (albeit a very remarkable one): ‘Indeed, even if they [i.e. those who knew Christ personally] regarded him as the true promised Messiah, and called him, as the Messiah, the Son of God: it still cannot be denied that they did not mean by this a Son of God who was of the same essence as God’.36 Only the theological interpretation placed on Christ’s activities at a later date by the last of the evangelists, namely St John, could justify the claims which were subsequently made for his divine significance;37 and Lessing’s scepticism concerning this gospel is made abundantly clear in The Testament of St John of 1777.38 His final verdict on Christ’s divine status, as expressed in his First Supplement […] to the Necessary Answer of 1778, is accordingly that there is no reliable evidence whatsoever for it in the Scriptures, and that the Church Fathers relied rather on oral tradition than on the Bible when they formulated the doctrine of the Trinity during the fourth century: ‘Anyone who does not bring the divinity of Christ into the New Testament, but seeks to derive it solely from the New Testament, can soon be refuted [...]. They [the Church Fathers] did not claim that their doctrine was a truth clearly and distinctly contained in Scripture, but rather a truth derived directly from Christ and faithfully passed down to them from father to son.’39 But like the evidence of the Bible, that of oral tradition is no more than historical; and this, of course, gives rise to the famous crux in On the Proof of the Spirit and of Power (1777) concerning ‘the broad and ugly ditch’ which separates historical evidence from demonstrable rational truth:40

if I have no historical objection to the fact that Christ raised someone from the dead, must I therefore regard it as true that God has a Son who is of the same essence as himself? What connection is there between my inability to raise any substantial objection to the evidence for the former, and my obligation to believe something which my reason refuses to accept?

It is essential to note once again that it is not the doctrine of the Trinity itself which Lessing here finds incompatible with reason, but only the identification of the historical Christ with the second person of the Trinity. This doubt still besets him in what is perhaps his last pronouncement on the subject, the short reflection The Religion of Christ, probably of 1780, in which ‘the Christian religion’, defined as that religion which treats Christ himself as divine, is described as ‘so uncertain and ambiguous that there is scarcely a single passage which any two individuals, throughout the history of the world, have thought of in the same way’.41

The scepticism of these late writings is not, of course, Lessing’s only response to religious ideas in his final years. It goes along with that growing interest in intellectual experiment, in rational speculation, which finds its fullest expression in Ernst and Falk and The Education of the Human Race.42 In contrast to his defence, in 1773, of Leibniz’s orthodox assertion that the central mysteries of Christianity cannot be resolved by reason, he now returns, in The Education of the Human Race, to a position close to that of The Christianity of Reason, and expressly defends his right to unchecked speculation:43

Let it not be objected that such speculations on the mysteries of religion are forbidden. [...] the development of revealed truths into truths of reason is absolutely necessary if they are to be of any help to the human race. [...]

It is not true that speculations on these things have ever done damage and been disadvantageous to civil society […]

On the contrary, such speculations—whatever individual results they may lead to—are unquestionably the most fitting exercises of all for the human understanding […]

In his renewed attempt in this late work to explore the rational potential of the Christian mysteries—especially that of the Trinity—Lessing introduces an important new factor which had not, so far as I am aware, played any significant part in Trinitarian thought during the Enlightenment, or indeed since the Reformation, namely history. In doing so, he follows a twofold strategy. On the one hand, he looks to historical reality for a rational sense akin to that revealed in the mysteries; and on the other, he tries once more to deduce from the mysteries a rational meaning which might help to make further sense of historical reality. The aim of this dual approach is to demonstrate not only that reason and revelation coincide, but also that both have an objective correlate in human history. Lessing’s aim, in short, is to overcome ‘the broad and ugly ditch’ which separated historical from rational truth, no longer by direct inference from the former to the latter (for he had concluded, with Leibniz, that this was impossible), but by a novel attempt to detect parallel patterns in both. It will shortly be argued that this attempt was to have far-reaching significance for later German thought; but something must first be said about the Trinitarian content of Lessing’s philosophical treatise. His relevant observations are as follows:44

Must God not at least have the most complete representation of himself, i.e. a representation which contains everything which is present within him? But would it include everything within him if it contained only a representation, only a possibility of his necessary reality, as well as of his other qualities? [...] Consequently, God can either have no complete representation of himself, or this complete representation is just as necessarily real as he himself is, etc. […] and this much at least remains indisputable, that those who wished to popularise the idea could scarcely have expressed themselves more comprehensibly and fittingly than by describing it as a Son whom God begets from eternity. [...] What if everything should finally compel us to assume that God […] chose rather to give [man] moral laws and to forgive him all transgressions in consideration of his Son—i.e. in consideration of the independently existing sum of his own perfections, in comparison with which and in which every imperfection of the individual disappears—than not to give him them and thereby to exclude him from all moral happiness, which is inconceivable without moral laws?

The affinity between Lessing’s reflections on the Trinity in The Education of the Human Race and those in The Christianity of Reason is obvious and has frequently been noted. Just how close the link between the two works is becomes even clearer when we realise that a particular topic which, according to Naumann’s letter of 1753, was to have been dealt with in the final, unwritten section of The Christianity of Reason—namely ‘the origin of evil’45 —is in fact taken up in The Education of the Human Race.46 But despite such affinities, there are significant differences in the treatment of the Trinity in the two works. For in the first place, Lessing now claims—with an oblique acknowledgement of a similar, but more mystical scheme in the work of Joachim of Fiore and other medieval writers—that history itself displays a tripartite progression of increasing rationality, the third phase of which is yet to come:47 that is, the structure of the ultimate model of rationality, namely the Trinity, is reflected in the objective creation of the three-personed creator. And secondly, Lessing’s rational deduction of the Trinity itself no longer distinguishes between the eternal generation (‘from eternity’) of the Son and the temporal, but equally necessary, creation of the universe.48 On the contrary, while the ‘necessary reality’ of God’s conception of himself (corresponding to the necessary identity of thought and creation for God in The Christianity of Reason) refers on this occasion only to the Son and not to the universe as well, this Son is himself defined in terms much more suggestive of the created universe than of the Son of Scripture and of the Athanasian Creed; and just as in the early fragment, no attempt whatsoever is made to identify this Son with the historical Christ. Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi was certainly in no doubt that the first two persons of Lessing’s Trinity were simply coded expressions for the creator and creation as understood in Spinoza’s metaphysics. For in response to Lessing’s suggestion in Paragraph 73 of The Education of the Human Race ‘that his [i.e. God’s] unity must also be a transcendental unity which does not exclude a kind of plurality’, Jacobi commented: ‘But considered solely in this transcendental unity, the deity must be absolutely devoid of that reality which can only be expressed in particular individual things. This, the reality, with its concept, is therefore based on Natura naturata (the Son from eternity); just as the former, the possibility, the essence, the substantiality of the infinite, with its concept, is based on Natura naturanti (the Father).’49 And when, in Paragraph 75, Lessing describes the Son as ‘the independently existing sum of his own [i.e. God’s] perfections, in comparison with which and in which every imperfection of the individual disappears’, his words are undoubtedly suggestive of the created universe—though not so much that of Spinoza as that of Leibniz, in which the apparent imperfection of individual elements is as nothing when compared with the perfection of the whole.50 It is also significant that, in the last few references to God after the deduction of the Trinity in The Education of the Human Race, only one (on the God of Joachim and his medieval contemporaries) directly employs the word ‘God’ (Paragraph 88), which is replaced by ‘nature’ on two other occasions (Paragraphs 84 and 90). And as for the traditional distinction between the supra-temporal existence of the Trinity (including the Son) ‘from eternity’, and the finite and temporal existence of creation, Lessing seems to be at pains to efface it: in his vision of the future course of history and of the transmigration of souls within the present world, he presents this process not as finite but as eternal, as the concluding sentence of the entire work emphasises: ‘Is not the whole of eternity mine?’.51 Finally, it is a curious fact that the Holy Spirit, which had featured in the deduction of the Trinity in the Christianity of Reason, does not appear at all in the parallel deduction in the Education of the Human Race. This serves to reinforce that parallel between history and revelation (or reason) which Lessing tries to establish with the help of Joachim of Fiore’s chiliastic interpretation of history: just as the third age (of the Spirit) has still to come, so too does the self-realisation of reason (or the rational deduction of dimly perceived truths by the human intellect) remain at present unfinished.

It must be emphasised that the assimilation of the Trinity to the temporal universe and to human history in The Education of the Human Race is by no means complete. In keeping with the experimental, allusive strategy of his late works, Lessing offers no systematic theology of history: the precise status of the Son remains ambiguous, and no rational deduction of the Holy Spirit is supplied. It is true that, in Christian theology, there had always been some kind of link between the second person of the Trinity and the temporal universe—at least since Origen formulated his doctrine of eternal generation; and while orthodoxy has always insisted that Father and Son are co-eternal, it has long been acceptable to believe that ‘the Father represents the Eternal Source of created Time, the Transcendent Origin, and the Son represents the Eternal Agent, immanent in the Time-process’.52 But as soon as creation itself is deduced as a necessary consequence of God’s being, pantheistic implications are difficult to avoid; for as one authority puts it: ‘The heart of pantheism is to be found in the abolition of particularity because the world and everything in it becomes reduced to a logical implication of the being of God.’53 In this very general sense—and without seeking to re-open the time-honoured debate concerning Lessing’s supposed Spinozism—we may certainly detect pantheistic overtones in Lessing’s Trinitarian deductions. But in his case, the balance is already shifting away from all three persons of God to the created world: his rational deduction of the Trinity is complemented by an inductive review of history within a Trinitarian framework. In fact, the assimilation of the universe to God in the pantheism of the early modern period is merely a prelude to the assimilation of God to the universe, and Lessing’s doctrine of the Trinity marks a crucial stage in this progression. He is the first, so far as I can determine, to relate the Trinity simultaneously to the self-realisation of reason as a divine or ideal principle and to the created universe (and more specifically to human history). The consequences of this development for subsequent German thought will be discussed in the remainder of this essay.

Lessing’s (at least partial) assimilation of God to the created universe and to human history did not pass unnoticed among his contemporaries. It is one of the central themes in the so-called Spinozastreit (‘Spinoza Quarrel’) of the 1780s, and probably helped to shape the theology of Herder’s dialogues God of 1787.54 But the full implications of Lessing’s Trinitarian speculations were to be realised not in the works of Herder, but in the writings of the next generation.

From an early stage in his career, the philosopher Schelling was familiar with Lessing’s speculative construction of the Trinity in The Education of the Human Race. He refers explicitly to it in his Lectures on the Method of Academic Study of 1802, saying of the doctrine of the Trinity:55

Reconciliation, through God’s own birth into finitude, of the finite realm which has fallen away from him is the first thought of Christianity and the completion of its whole view of the universe and its history in the idea of the Trinity, which for that very reason is absolutely necessary to it. It is well known that Lessing, in his work The Education of the Human Race, attempted to reveal the philosophical significance of this doctrine, and what he said about it is perhaps the most speculative element in all his writings. But his view still lacks the connection of this idea with the history of the world, which consists in the fact that the eternal Son of God, born from the being of the Father of all things, is the finite realm itself as it is in the eternal contemplation [Anschauung] of God, and which appears as a suffering God subordinated to the vicissitudes of time and, in the culmination of its appearance, in Christ, closes the world of finitude and opens that of infinity, or the domain of spirit.

Perhaps in order to magnify the originality of his own Trinitarian speculations, Schelling is unfair to Lessing on two counts here. For despite Schelling’s denial, Lessing had indeed established close links between the Trinity and human history in The Education of the Human Race (as described in detail above); and he had also implied that a strong affinity, or even identity, exists between the Son of the Trinity and the finite world as a whole (Schelling’s ‘finite realm itself as it is in the eternal contemplation of God’). The only significant difference between the two thinkers here is that, while Lessing offers allusive hints rather than dogmatic propositions, and detects a structural parallel between human history and the Holy Trinity without explicitly assimilating the former to the latter, Schelling presents a systematic deduction of a kind that Hegel was later to develop more fully, in which human history and its phases appear as necessary consequences of the self-realisation of the divinity. Schelling gives no indication, however, whether he was familiar with Lessing’s earlier reflections on the Trinity in The Christianity of Reason. He does continue, in his later works (see p. 103 below), to speculate further on the Trinity; but these later thoughts are neither as fully developed nor as closely related to those of Lessing as are those of his friend Hegel, whose Trinitarian thought and its relationship to that of Lessing will now be examined.

Hegel’s debt to and affinities with Lessing have never been adequately investigated, and only a few scholars have noted specific influences. These include Henry E. Allison, who suggests that the central thesis of the young Hegel’s fragmentary essay The Positivity of the Christian Religion (1795–96) echoes Lessing’s distinction, in his posthumous fragment The Religion of Christ, between the religion of Christ as a purely ethical faith, and the Christian religion with all its positive doctrines.56 Wulf Köpke also notices a close familiarity with Nathan the Wise in Hegel’s early writings,57 and Johannes von Lüpke detects ‘the determining influence of Lessing’ in the writings of Hegel’s Berne and Frankfurt periods.58 Other Lessing scholars not infrequently point to similarities between The Education of the Human Race and Hegel’s philosophy of history; but they tend simply to note that both thinkers present history as a teleological process governed by an immanent providence,59 or to describe Lessing’s essay as the first of a series of increasingly secular philosophies of history continued by Hegel, Marx, and others.60

Hegel scholars, on the other hand, have long been aware that the young Hegel was profoundly influenced by Lessing, and that he even looked up to him as something of a hero.61 Schelling, after all, addressed him in 1795 as ‘Lessing’s intimate’;62 and although Hegel’s early excerpts from Lessing’s works have not survived,63 various scholars have noted that he was closely familiar with, and indebted to, several of Lessing’s works, including Nathan the Wise,64 The Education of the Human Race65 and Ernst and Falk.66 In addition to these works, he was almost certainly familiar—as already mentioned—with the posthumous fragment The Religion of Christ, which Lessing’s brother Karl published in 1784 in the volume G. E. Lessing’s Posthumous Theological Papers and again in 1793 in Volume 17 of Lessing’s Complete Works. But if this is the case, then it is equally likely that the young Hegel also knew Lessing’s early fragment The Christianity of Reason, which appeared posthumously in the same two volumes, and which—together with Paragraphs 73 and 75 of The Education of the Human Race—constitutes Lessing’s main attempt to rationalise the mystery of the Holy Trinity. Whether or not Hegel studied and ruminated on the writings in question—and there is a strong probability that he did—the remainder of this essay will argue that there is a striking continuity between his own Trinitarian reflections and those of his early hero Lessing: the logic of the earlier thinker’s ideas is amplified and completed in the work of his more systematically-minded successor.

It has rightly been said that Christianity ‘is the most direct route to the heart of Hegel’s philosophy’.67 And the one aspect of Christianity which is absolutely central to his thinking is the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, which he sees as the archetypal model of spirit (Geist) in general. All spirit or thought, for Hegel, is a dynamic process, and the structure of the Trinity is in his view essentially dynamic. It is for him the supreme example of spirit’s self-comprehension and self-realisation, and hence of universal reason as it progressively actualises itself throughout creation, and in particular in human thought and history. As he puts it in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History:68

Spirit, therefore, is the product of itself. The most sublime example is to be found in the nature of God himself [...]. the older religions also referred to God as a spirit; [...] Christianity, however, contains a revelation of God’s spiritual nature. In the first place, he is the Father, a power which is abstract and universal but as yet enclosed within itself. Secondly, he is his own object, another version of himself, dividing himself into two so as to produce the Son. But this other version is just as immediate an expression of him as he is himself; he knows himself and contemplates himself in it—and it is this self-knowledge and self-contemplation which constitutes the third element, the Spirit as such. [...] It is this doctrine of the Trinity which raises Christianity above the other religions. [...] The Trinity is the speculative part of Christianity, and it is through it that philosophy can discover the Idea of reason in the Christian religion too.

Hegel’s Trinitarian reflections are, of course, much more central to his thought, and much more fully developed, than Lessing’s.69 But as the above quotation shows, they plainly have much in common with them. In particular, both thinkers regard the Trinity as a model for the process of human history, which displays a pattern parallel to the internal dynamics of reason itself: just as the divine nature is progressively realised in rational creation, so also does human reason progressively develop to ever higher degrees of insight (which Lessing associates primarily with the development of morality, and Hegel primarily with that of freedom). Hegel, of course, goes far beyond Lessing’s simple tripartite model of the three ages of man, and provides a long and circumstantial account of the whole of world history, including its geographical basis and the rise and fall of all major cultures of the past as known in his time. Nevertheless, his basic premise that history is itself a rational process, and that the archetypal model of this process is the Trinity, reveals a fundamental affinity between his Lectures on the Philosophy of History and Lessing’s Education of the Human Race.70

If we now turn to the theological significance of Lessing’s and Hegel’s thoughts on the Trinity, the continuity between the two is again conspicuous. Hegel attempts, for example (again in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History), to deduce both the Son and the created world from the nature of God as spirit or universal reason, much as Lessing had done in The Christianity of Reason; he does so by distinguishing between two discrete aspects of the spirit’s self-expression, namely as pure Idea (the Son) and as finite particularity (the world) respectively. As in Lessing’s two modes of divine self-conception (‘at once’ and ‘discretely’), these two aspects are parallel and equally necessary expressions of God:71

the spirit sets itself in opposition to itself as its other […] The other, conceived as pure idea, is the Son of God, but this other in its particularity is the world, nature, and finite spirit: the finite spirit is thereby itself posited as a moment of God. Thus man is himself contained in the concept of God, and this containment can be expressed as signifying that the unity of man and God is posited in the Christian religion.

But his Trinitarian deduction is at the same time more comprehensive than Lessing’s, in that Hegel also finds a place in it for the Incarnation of the Son—i.e. the coming of the historical Christ, whom Lessing had found it impossible to accommodate in his rational deduction of the Trinity: ‘“When the fullness of the time was come, God sent forth his Son”, says the Bible.72 This simply means that self-consciousness had raised itself to those moments which belong to the concept of spirit, and to the need to grasp these moments in an absolute manner.’73 What we have here is in fact the full and systematic exposition of ideas which were adumbrated in Lessing’s writings in fragmentary and experimental form, and briefly enlarged upon by the young Schelling.

But apart from the fact that they are more fully and systematically developed than Lessing’s, Hegel’s Trinitarian deductions would appear at first sight to differ from Lessing’s in a more fundamental respect, in that he consistently seems more anxious—not unlike Leibniz and Wolff—to show that his interpretations of Christian mystery are entirely compatible with orthodox Christian doctrine. This is obvious, for example, in the care he takes to give separate rational explanations of the Son as part of the Trinity and the historical Christ as the embodiment of the Son in time, i.e. in history. The same concern is evident when he explicitly warns, in his Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion, against any direct identification—such as Lessing had seemed to hint at in The Education of the Human Race—of ‘the eternal Son’ with the created universe.74

Why Hegel should be more concerned than Lessing often was to accommodate his religious ideas to orthodox doctrines is an interesting question. His apparent respect for orthodoxy has, I believe, much more to do with philosophical, indeed secular considerations than with any profound theological conformity, or with any desire to preserve the Christian mysteries from full rational explication—for he is no less committed than Lessing was to doing precisely that. The apparent difference between Hegel and Lessing in the matter of Christian orthodoxy is due above all to the systematic character of Hegel’s thought, as opposed to Lessing’s love of experiment and his insouciance over any real or apparent philosophical contradictions he might find himself in. For Hegel’s fundamental philosophical endeavour is to defend the unity and mutual compatibility of all expressions of the human mind, and of the various elements of his own system in particular. That is, in its fully developed form, religion, as well as art, must ultimately embody the same truths as philosophy. The truths which art and religion embody can therefore in principle be fully expressed in philosophical terms, and in practice, Hegel claims to have so expressed them in his own system. In short, there is no ultimate mystery about existence which philosophy—or reason—cannot resolve.75

Hegel accordingly says of Lutheran Protestantism, which is for him the supreme and most developed form of Christianity: ‘Protestantism requires us to believe only what we know’.76 And it is here that his position as an heir to the Enlightenment, and his close affinity with Lessing, becomes most obvious (although he also exhibits an esprit de système which has more in common with early eighteenth-century rationalism than with the later phases of the Enlightenment). In his early years, Lessing had set out, very much in the spirit of Wolffian rationalism, to construct a ‘Christianity of Reason’, but soon abandoned it in a half-finished state. When he resumed it in The Education of the Human Race, his conclusions are even more tentative and fragmentary—but this time by design, as the older Lessing is more interested in destabilising existing systems than in creating new ones. [On this feature of the older Lessing’s thought, see Chapter 3, pp. 77–78 above]. But Hegel began where Lessing left off, and completed the project of a ‘Christianity of Reason’ more comprehensively—if I am not mistaken—than any other thinker before or since. His logical analysis of the Spirit and its Trinitarian structure is a much more circumstantial development of Lessing’s rational deduction; his rationalisation of the Son achieves what Lessing had vainly aspired to, and comprehensively embraces the second person of the Godhead, the historical Christ, and the created universe; his philosophy of history—as already mentioned—is a more detailed and impressive rational account of the historical process as the realisation of spirit (again with strong Trinitarian implications) than Lessing’s simple Joachite scheme; and his presentation of revealed religion and its mysteries as an embodiment of truth at a less developed level than that of rational philosophy is an impressive fulfilment of Lessing’s demand for ‘the development of revealed truths into truths of reason’. This is not for a moment to suggest that Lessing’s writings on the Trinity were the direct source or inspiration of Hegel’s philosophical system, whose origins are far more complex than that. All that I wish to argue is that Lessing’s reflections on the Trinity represent a critical stage in the application of philosophy to Christian theology, and open up possibilities which various others, and Hegel in particular (probably in conscious awareness of Lessing’s earlier efforts) were later to exploit.

In conclusion, a few words may be said on later developments in Trinitarian thought, and on the significance of Lessing’s and Hegel’s contributions to it as viewed in historical retrospect. Speculative constructions of the Trinity reappear in the works of various writers after Hegel, and many of them are plainly indebted to him. The late Schelling, for example, in his ‘philosophy of revelation’ of the 1840s and 1850s, renews the Joachite model of the three ages of history,77 and cites Leibniz and Lessing as major philosophical interpreters of the Trinity in the modern period.78 Clearly indebted to Hegel, Schelling repeats the latter’s denial that the Son can be identified with the created world, but nevertheless proceeds to interpret the Persons of the Trinity as ‘cosmic, demiurgical powers’ which progressively realise themselves in temporal reality.79 Related ideas, again obviously influenced by Hegel, can be found in the works of such nineteenth-century philosophers and theologians as Anton Günther (1783–1863),80 Christian Hermann Weisse (1801–66),81 and Aloys Emanuel Biedermann (1819–85).82

It is possible, however, that Hegel’s philosophical analysis of the Trinity took this particular line of enquiry as far as it could go, for few philosophers have attempted to take it any further. His legacy is to be found not so much among philosophers as among theologians, especially the exponents of that so-called ‘process theology’ which presents God as developing in time and influenced by temporal events.83 In orthodox quarters, the reception of this aspect of his thought in recent times has, of course, remained predominantly critical. It was already apparent to Leibniz that philosophical deductions of the Trinity are fraught with difficulty, and he and other defenders of orthodoxy in the eighteenth century were not convinced by them. Johann Thomas Haupt pointed out in 1752 (following Porphyry’s critique of Christianity in the third century) that attempts to deduce the second person of the Trinity from the first readily lead to an infinite regress: for even if we conclude that God’s ‘representation of himself’ necessarily has an independent objective existence as the Son, equal and parallel to that of the Father, the Son’s ‘representation of himself’ must in turn have an independent objective existence, and so on ad infinitum: in short, there is no rational ground for limiting the number of persons in the Trinity to three.84

This difficulty is removed, of course, as soon as the Son is identified with the created universe, which can be represented not as a mirror-image of the Father but as a gradual unfolding of the Father’s perfections in the temporal process. But this construction is no less fraught with difficulties than the previous one. Even Hegel’s formulation—although it is far more sophisticated than its eighteenth-century predecessors—attributes a metaphysical necessity of an impersonal kind to the expression of the Absolute in the world of appearances, a necessity which is incompatible with the action of a consciously intelligent, free, and omnipotent creator of the universe of space and time; for unlike Christian orthodoxy, it implies that the created universe (including human history) is a necessary ‘moment’ of the divine nature, essential to the being of God as the vehicle of his developing consciousness, rather than the free product of his will.85 As one theological critic of German Idealism puts it:86

The Father ‘eternally begets and loves the Son through the Spirit’. But this activity of God is not the same as the Time process. The eternal begetting of the Son is not the same as the creation of the world, through which God comes to self-consciousness. This is to make us necessary to God, and in fact to make us the Second Person of the Trinity.

But the main weakness of Hegel’s construction of the Trinity, like Lessing’s and every other speculative deduction before and since, is that it is ultimately incommensurable with the empirical nature of the revelation which it purports to explain. In the last resort, Lessing’s ‘broad and ugly ditch’ remains as unbridgeable as ever. No rational deduction can demonstrate that the self-revelation of God necessarily took place specifically in Jesus of Nazareth as distinct from any other individual,87 nor can it prove the identity of the latter with that Son whom the Nicene Creed describes as ‘begotten of his Father before all worlds’, and of whom St Paul declares ‘he is before all things, and by him all things consist’.88

Lessing was conscious of these difficulties. But he did not abandon his efforts to rationalise the Trinity and other Christian mysteries, because he was convinced of their heuristic potential—even if whatever rational sense they might yield bore little relation to the historical basis of Christianity. As he puts it in Paragraph 77 of The Education of the Human Race: ‘And why should we not nevertheless be guided by a religion whose historical truth, one may think, looks so dubious, to better and more precise conceptions of the divine being, of our own nature, and of our relations with God, which human reason would never have arrived at on its own?’89

What Lessing suggests here is, I think, absolutely right—more right (or at least potentially more productive) than what he says in Paragraph 4 of the same work, which notoriously appears to contradict the later statement just quoted from Paragraph 77: ‘revelation [...] gives the human race nothing which human reason, left to itself, would not also arrive at; it merely gave it, and gives it, the most important of these things sooner.’90 This latter passage reflects his own earlier endeavours, as in The Christianity of Reason, to provide a conclusive rational demonstration of one of the main Christian mysteries. Paragraph 77, however, represents his later, more fruitful insight that the source of an idea (and this is as true in philosophy as it is in science) is in itself unimportant. It is its potential to generate further thought that counts. I have tried to show how some of that potential was realised, not just in theology but also in the philosophy of history; for in conjunction with Herder’s cultural relativism, Hegel’s assimilation of the Trinity, as universal, self-realising reason, to history supplied the basis for the most influential philosophical account in modern times of the historical process and its internal dynamics.

1 An earlier version of this chapter was originally published as ‘The Rationalisation of the Holy Trinity from Lessing to Hegel’, in Lessing Yearbook, 31 (1999), 115–35.

2 I am grateful to Professor Douglas Hedley for advice on some of the theological issues discussed in this essay, and to Professor Laurence Dickey for new insights into Hegel’s philosophy of religion.

3 On the distinction between ‘cosmological’ and ‘ontological’ approaches to natural theology see Paul Tillich, ‘Zwei Wege der Religionsphilosophie’, in Tillich, Gesammelte Werke, ed. by Renate Albrecht, 14 vols (Stuttgart: Evangelisches Verlagswerk, 1959–75), V, 122–37).

4 On the types of argument involved and their role in the natural theology of German Idealism see Werner Beierwaltes, Platonismus und Idealismus (Frankfurt a. M.: Klostermann, 1972).

5 On the doctrine of the Trinity in general, see Leonard Hodgson, The Doctrine of the Trinity (London: Nisbet, 1943); Essays on the Trinity and the Incarnation, ed. by A. E. J. Rawlinson (London: Longmans, 1928); article ‘Trinität’ in Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3rd edn, 7 vols (Tübingen: Mohr, 1957–65), VI, 1025; Emerich Coreth, Trinitätsdenken in neuzeitlicher Philosophie, Salzburger Universitätsreden, 77 (Salzburg: A. Pustet, 1986); Jürgen Moltmann, History and the Triune God. Contributions to Trinitarian Theology (London: SCM, 1991). On the early controversies, see especially Hodgson, The Doctrine of the Trinity, pp. 99 et seq.

6 On these controversies, see Hodgson, pp. 219–24 and J. Hay Colligan, The Arian Movement in England (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1913).

7 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Sämtliche Schriften, ed. by Karl Lachmann and Franz Muncker, 23 vols (Stuttgart, Leipzig and Berlin: Göschen, 1886–1924), XIV, 158; subsequent references to this edition are identified by the abbreviation LM.

8 The evidence for this date is contained in a letter of 1 December 1753 from Lessing’s friend Christian Nicolaus Naumann to Theodor Arnold Müller, in which the content of the fragment is accurately summarised. The letter is reproduced in Richard Daunicht, Lessing im Gespräch (Munich: Fink, 1971), pp. 58f.

9 See Alexander von der Goltz, ‘Lessings Fragment Das Christentum der Vernunft. Eine Arbeit seiner Jugend’, Theologische Studien und Kritiken, 30 (1857), 56–84 (esp. pp. 74–80). The work in question is Johann Thomas Haupt, Gründe der Vernunft zur Erläuterung und zum Beweise des Geheimnisses der Heiligen Dreieinigkeit (Rostock and Wismar: J. A. Berger and J. Boedner, 1752).

10 Karl S. Guthke, ‘Lessings Rezensionen. Besuch in einem Kartenhaus’, Jahrbuch des Freien Deutschen Hochstifts (1993), 1–59 (esp. pp. 38–40). For the review itself, see LM IV, 382f. The fact that Lessing makes no reference, in The Christianity of Reason, to various rationalisations of the Trinity described by Haupt which are not unlike his own, and that he presented his conclusions to his friend Naumann as ‘a new system’, might well suggest that he knew little or nothing of Haupt’s work.

11 See the various references to this work in Lessing’s and Mendelssohn’s treatise Pope a Metaphysician!, written in 1754 (LM VI, 411–45).

12 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Philosophische Schriften, ed. by Hans Heinz Holz and other hands, 4 vols in 6 (Darmstadt: Insel Verlag, 1965–92), II/1, p. 158.

13 St. Augustine, The Trinity, translated by Stephen McKenna, The Fathers of the Church, 45 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1970), pp. 175f., 467ff., 513, 521, etc.

14 Ibid., p. 311.

15 Ibid., p. 289; on the philosophical affinities of Augustine’s doctrine, see the article ‘Augustine’, in The New Catholic Encyclopedia (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1967), I, 1053.

16 On the Trinitarian deductions of Lull and Keckermann see the article ‘Raymundus Lullus’, in the Realencyclopädie für protestantische Theologie und Kirche, 3rd edn (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1896–1913), XI, 712–14 and the article ‘Bartholomäus Keckermann’, in ibid., X, 196; cf. also Haupt, Gründe der Vernunft, pp. 291ff.

17 Cf. Hodgson, The Doctrine of the Trinity, p. 68.

18 Siegmund Jacob Baumgarten, Theologische Lehrsätze von den Grundwahrheiten der christlichen Lehre (Halle: Gebauer, 1747), p. 82; cf. ibid., Evangelische Glaubenslehre, 3 vols, ed. by Johann Salomo Semler (Halle: Gebauer, 1759–60), I, 570. On Baumgarten’s views on the Trinity, see also Haupt, Gründe der Vernunft, pp. 184f. and Reinhard Schwarz, ‘Lessings Spinozismus’, Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche, 65 (1968), 271–90 (esp. pp. 275–83).

19 Baumgarten, Theologische Lehrsätze, p. 81; cf. Evangelische Glaubenslehre, I, 565.

20 Cf. H. B. Nisbet, ‘Lessings Ethics’, Lessing Yearbook, 25 (1993), 1–40 (pp. 3, 5, and 13).

22 LM V, 175–78; for a complete English translation of the work, see Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, translated by H. B. Nisbet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 25–29.

23 John XV.26 and XVI. 27.

24 See, for example, LM XII, 298; also Nisbet, ‘Lessing’s Ethics’, pp. 21–24.

25 On the possible influence of Spinoza on Lessing’s early thought see Karl S. Guthke ‘Lessing und das Judentum’, Wolfenbütteler Studien zur Aufklärung, 4 (1977), 229–71 (pp. 252ff.); cf. also Benedict de Spinoza, Ethics, Part I, Propositions 17 and 33. As a Jew, Spinoza , of course, has no place for Christian theology in his system.

26 Namely in Paragraphs 1, 2, 4, 9, 12, 17, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, and 27.

27 Lessing to Mendelssohn, 1 May 1774, in LM XVIII, 110.

28 Cf. Mendelssohn’s humorous critique of the doctrine of the Trinity in his letter of 1 February 1774 to Lessing (LM XXI, 6).

29 LM XIV, 292 (for a complete translation of this work, see Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, pp. 30–31); cf. Spinoza, Ethics, Part I, Propositions 15 and 35.

30 On some of these developments see Henry E. Allison, Lessing and the Enlightenment (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1966), pp. 121–61.

31 See LM XII, 90 and 93–99; also Lessing to Mendelssohn, 1 May 1774, in LM XVIII, 110 and Georges Pons, G. E. Lessing et le Christianisme (Paris: Didier, 1964), p. 267.

32 See LM XVI, 251–53 (against Töllner and Teller); also Schwarz, ‘Lessings Spinozismus’, pp. 283f.

33 LM XII, 203–54.

34 LM XVIII, 110

35 Cf. Pons, Lessing et le Christianisme, p. 397.

36 LM XVI, 389; English translation of this work in Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, pp. 148–71.

37 LM XVI, 390.

38 LM XIII, 9–17; English translation of this work in Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, pp. 89–94.

39 LM XIII, 373 and 376.

40 LM XIII, 6; English translation of this work in Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, pp. 83–88.

41 LM XVI, 519; English translation of this work in Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, pp. 178f.

42 See my discussion of these features in Chapter 3 above.

43 LM XIII, 431f.; English translation of this work in Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, pp. 217–40.

44 LM XIII, 430f.

46 In Paragraph 74 of that work: LM XIII, 431.

47 Paragraphs 86–88, LM XIII, 433f.; on Joachim’s doctrines, see Herbert Grundmann, Studien über Joachim von Floris (Leipzig: Teubner, 1927) and Moltmann, History and the Triune God, pp. 91–109. It is, however, important to note that Joachim does not assimilate the Trinity itself to the historical process, as was to happen in varying degrees in the so-called ‘process theology’ of more recent times.

48 LM XIII, 430f.

49 Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, Werke, 6 vols (Leipzig: G. Fleischer, 1812–25), IV/1, pp. 87f. Panajotis Kondylis, Die Aufklärung im Rahmen des neuzeitlichen Rationalismus (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1981), p. 612, similarly concludes that Lessing identifies the Son with the created world in this passage.

50 LM XIII, 431; the use of ‘in which’ in addition to ‘with which’ is significant: it suggests that the imperfections are to be found within the Son, which would scarcely make sense if the Son were distinct from the created world.

51 LM XIII, 436.

52 F. H. Brabant, ‘God and Time’, in Rawlinson (ed.), Essays on the Trinity, pp. 354f.

53 Colin E. Gunton, The One, the Three and the Many (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 56.

54 See Marion Heinz, ‘Existenz und Individualität. Untersuchungen zu Herders Gott’, in Kategorien der Existenz. Festschrift für Wolfgang Janke, ed. by Klaus Held and Jochem Hennigfeld (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1993), pp. 160–78 (p. 173).

55 F. W. J. von Schelling, Sämtliche Werke, ed. by K. F. A. Schelling, 14 vols (Stuttgart: Cotta, 1856–61), I. Abteilung, V, 294.

56 Allison, Lessing and the Enlightenment, pp. 193f.; see also Hegel, Werke, ed. by Eva Moldenhauer and Karl Markus Michel, 20 vols (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1970), I, 104–229: Hegel cites Lessing on several occasions in this essay.

57 Wulf Köpke, ‘Der späte Lessing und die junge Generation’, in Humanität und Dialog. Lessing und Mendelssohn in neuer Sicht, ed. by Ehrhardt Bahr and other hands (Detroit, MI and Munich: Wayne State University Press and edition text+kritik, 1982), pp. 211–22 (pp. 211 and 215f.).

58 Johannes von Lüpke, Wege der Weisheit. Studien zu Lessings Theologiekritik (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, 1989), p. 28.

59 See, for example, Wilm Pelters, Lessings Standort. Sinndeutung der Geschichte als Kern seines Denkens (Heidelberg: L. Stiehm, 1972), pp. 97–100.

60 See, for example, Arno Schilson, Geschichte im Horizont der Vorsehung. G. E. Lessings Beitrag zu einer Theologie der Geschichte (Mainz: Matthias Grünewald Verlag, 1974), pp. 291 and 293.

61 For detailed evidence, see the references to Lessing in the index to H. S. Harris, Hegel’s Development. Toward the Sunlight 1770–1801 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), especially those on pp. 43, 99, 101–03, 140f., 174n., and 189.

62 Schelling to Hegel, 4 February 1795, in Briefe von und an Hegel, ed. by Johannes Hoffmeister, 5 vols (Hamburg: Meiner, 1952–54), I, 21.

63 See Harris, Hegel’s Development, p. 48.

64 Ibid., pp. 37, 141, 174, 329, etc.

65 Ibid., pp. 99 and 213n; also Laurence Dickey, Hegel. Religion, Economics, and the Politics of Spirit 1770–1807 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), pp. 160 and 284.

66 Jacques d’Hondt, Hegel Secret. Recherches sur les sources cachées de la pensée de Hegel (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1968), pp. 267–80; also Harris, Hegel’s Development, p. 105.

67 Duncan Forbes, Introduction to Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of World History. Introduction: Reason in History, translated by H. B. Nisbet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), p. ix.

68 Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of World History (as in note 67 above), p. 99.

69 Hegel’s fullest discussion of the Trinity appears in his Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion: see Hegel, Werke, XVII, 221–40. For a general account of his Trinitarian thought and its development see Jörg Splett, Die Trinitätslehre G. W. F. Hegels (Freiburg and Munich: Alber, 1965); also Dale M. Schlitt, Hegel’s Trinitarian Claim. A Critical Reflection (Leiden: Brill, 1984).

70 I accordingly cannot agree with Schilson, Geschichte im Horizont der Vorsehung, p. 274, who says that neither Lessing’s early nor late discussions of the Trinity in any way anticipate Hegel’s Trinitarian construction of the philosophy of history.

71 Hegel, Werke, XII, 392.

72 Galatians IV.4.

73 Hegel, Werke, XII, 386f.

74 Ibid., XVII, 245.

75 It is precisely the claim to have rationalised all mystery out of Christianity that rendered Hegel’s system unacceptable to various philosophically inclined Christians such as Coleridge: see Douglas Hedley, ‘Coleridge’s Intellectual Intuition, the Vision of God, and the Walled Garden of “Kubla Khan”’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 54 (1998), 115–34 (p. 134).

76 Hegel, Werke, ed. by Phillip Marheineke and other hands, 18 vols (Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 1832–45), XII/1, p. 246.

77 Schelling, Werke, ed. by Manfred Schröter, 6 vols (Munich: Beck, 1965; reprint of 1927 edition), V. 463f.

78 Ibid., VI, p. 314.

79 Ibid., VI, 314 and 339f.

80 See Bernhard Osswald, Anton Günther. Theologisches Denken im Kontext einer Philosophie der Subjektivität (Paderborn and Munich: Schoningh, 1990, esp. pp. 179–229.

81 See the article on Weisse in Allgemeine deutsche Biographie XLI, 590–94 (p. 591).

82 See the article on Biedermann in Allgemeine deutsche Biographie, XLVI, 540–43 (p. 541).

83 Cf. Schlitt, Hegel’s Trinitarian Claim, p. 1.

84 Cf. Haupt, Gründe der Vernunft (see note 9 above), pp. 170, 185, 198f., and 294.

85 Cf. Hodgson, Doctrine of the Trinity, pp. 130–33 and 190.

86 F. H. Brabant in Rawlinson (ed.), Essays on the Trinity, p. 349.

87 Cf. Moltmann, History and the Triune God, p. 82.

88 Colossians I.17.

89 LM XIII, 482.

90 LM XIII, 416. See, however, Karl Eibl, ‘”kommen würde” gegen “nimmermehr gekommen wäre”. Aufklärung des “Widerspruchs” von § 4 und § 77 in Lessings Erziehung des Menschengeschlechts’, Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift, 65 (1984), pp. 461–64, who makes an interesting case for the view that the two paragraphs are not in fact in contradiction.