7. Rethinking the Role of the State in Technology Development: DARPA and the Case for Embedded Network Governance1

© Erica R. H. Fuchs, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0184.07

1. Introduction

Debates on the appropriate role for government in technology policy often fall into two camps—proponents of free markets; and proponents of government choosing technology winners. Among those who favor a strong role for government, most view the state’s role as limited to facilitating technology investment through tax policy, subsidies, and funding for basic research. A few argue for coordination of technology investment across the many arms of government. In search of this coordination, these few often turn to top-down bureaucracy. What is missing from these debates, however, is an alternative government role that has existed for the past fifty years in the U.S.: the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA.

Staffed at any moment with little more than one hundred people and $3 billion with which to stimulate U.S. innovation, this small arm of government charged with “preventing technological surprises” has met with fame and controversy beyond what its size would suggest. Historians have attributed to DARPA creation of everything from the Internet,2 and the personal computer,3 to the laser4 and Microsoft Windows.5 DARPA has appeared on the pages of Playboy Magazine,6 and the screen of the popular television show, The West Wing.7 Most pertinently, among those who study national innovation systems, DARPA has come to be seen as the pioneer of the methods now used broadly in what is called the U.S. Developmental Network State.8 As a consequence, today, agencies ranging from the intelligence community (ARDA—1998, IARPA—2006),9 to the Department of Homeland Security (HSARPA—2002), to the Department of Energy (ARPA-E—2007), all seem to want their own “ARPA”.

Despite such past success, between 2001 and 2008 DARPA underwent tremendous change. This change, initiated by director Tony Tether, brought on an outcry from the computing community—one of the primary benefactors and success stories of DARPA.10 This criticism suggested that DARPA was no longer “the old DARPA”. An in-depth look at history, however, shows that such change, and subsequent criticism, as occurred under Tether were not new. Rather, over the past decades, DARPA has gone through repeated shifts in its focus and its internal governance structures. This dynamic presents a puzzle—with so much change, what then is the DARPA model that its imitators should be copying?

To answer this question, at least in part, this paper focuses on the period immediately before and after the most recent changes within DARPA. Drawing on over fifty interviews, the paper uses grounded theory-building methods11 to uncover the processes used by DARPA program managers to influence technology trajectories in the U.S., and how those processes may have changed during Tether’s directorship. The paper focuses on the involvement of DARPA’s Microsystems Technology Office (MTO) in the development of four semiconductor materials technologies critical to the converging telecom and computing industry and to meeting the performance targets set by Moore’s Law.

The telecom and computing industries provide a useful example of industrial sectors traditionally supported by government funding and in particular by DARPA.12 In addition, the telecom and computing industries are a classic example of sectors that have undergone a recent decline in corporate R&D labs and a shift to a vertically fragmented industry structure, a phenomenon experienced more broadly in the U.S. innovation eco-system.13 Notably, despite the dramatic differences between DARPA from 1992 to 2001 versus from 2001 to 2008, during both time periods, the telecom and computing industries had already undergone vertical disintegration.

The results of this research suggest that past studies have, by focusing on DARPA’s culture and structure, overlooked a set of lasting, informal institutions among DARPA program managers. In the case of DARPA’s Microsystems Technology Office, what changed under Tether was not the processes used by the program managers, but rather the situations in which program managers apply these processes. Prior to 2001, DARPA’s processes for seeding and encouraging new technology trajectories involved (1) bringing star scientists largely from academia together to brain-storm new technology directions, (2) seed funding research themes common across disconnected star researchers, (3) encouraging early knowledge-sharing between these star researchers through required workshops, and (4) providing third-party validation for new technology directions to external funding agencies and industry. These processes support the sources of, knowledge flows around, and development of social networks necessary for initiating new technology directions in the research community. In contrast, since 2001, the DARPA program manager’s processes for coordinating technology directions involve (1) orchestrating the involvement of established vendors with academics and startups, (2) supporting knowledge-sharing between industry competitors through invite-only workshops, (3) providing third-party validation of new technology directions, and (4) supporting technology platform leadership at the system level. These new processes support the coordination of technology development within industry across a vertically fragmented industrial ecosystem such that the technology develops in line with longer term commercial and military goals.

These results suggest that, rather than being forced to choose between the extremes of free-markets or the heavy-hand of bureaucratic government, there is a third alternative for government support of cutting-edge technology development. In this third alternative, embedded government agents—who gain knowledge centrality and social capital in their role as DARPA program managers—are able to re-architect social networks14 among researchers so as to influence new technology directions. In doing so, these embedded agents are in constant contact with the research community, understanding emerging themes, matching these emerging themes to military needs, betting on the right people, bringing together disconnected researchers, standing up competing technologies against each other, and maintaining the systems-level perspective critical to orchestrate these disparate research activities spread throughout our national innovation ecosystem.

2. The Developmental Network State

Debates on the appropriate role for the state in science and technology development have continued for over two hundred years.15 In the U.S., even when a role for the state is acknowledged, the appropriate government function is often viewed as influencing the volume, not the direction of investment.16 Under Keynesian thought, “economic policy meant manipulating spending and taxation, money and credit”, not coordination of technology development.17 And yet, a host of literature documents alternative roles for the State in technology development beyond manipulation of spending and regulation.

One categorization of this literature is to split it into two types of theories—those that depict a Weberian-style hierarchy or “developmental bureaucratic state”; and those that argue for “experimental federalism”, “flexible developmental state”, “developmental network state”, or “networked polity”.18 Whereas the “Bureaucratic State” evokes descriptions of “centralized command-and-control” and “top-down policies” leveraging “government-based research and firm subsidies to develop local expertise in targeted industries;” the “networked” alternative is often described as “decentralized and distributed” with “mutual adjustment” and a focus on facilitating “building trust” and “coordination and cooperation among relevant parties”.19 In both governance forms, writers argue that to be successful, public officials must have “embedded autonomy”—i.e. be “embedded in a concrete set of social ties that binds the state to society and provides institutionalized channels for the continued negotiation and renegotiation of goals and policies”.20

In describing the networked polity, Chris Ansell proposes “that the state can operate as a liaison or broker in creating networks and empowering nonstate actors, especially when state actors occupy a central position in these networks”.21 The existing network literature helps us understand the emergence and consequences of being a broker. According to Ronald Burt,22 a broker is an individual who forms the only link between otherwise disconnected actors. Lee Fleming and David Waguespack add to this definition, distinguishing between brokers and boundary spanners.23 Here, Fleming and Waguespack’s boundary spanners are individuals who span different theoretical or organizational areas, but need not be the only individual playing that role. Thus, while all brokers are boundary spanners, not all boundary spanners broker.24 Notably, neither Burt nor Fleming gives agency to the broker or boundary spanner. While Burt focuses on how the structure of the network puts the broker in a position of power, Fleming and Waguespack focus on how existing human and social capital lead to individuals emerging as leaders in a community.25 In her qualitative field study, Natalia Levina brings in this agency.26 Specifically, she suggests that to create a new field, boundary-spanners must produce and use objects that become locally useful to both fields and acquire a common identity.27 However, while Levina provides practical insights into the boundary-spanning role, her boundary-spanner remains an inside member of the focus community.

In contrast to this earlier work, recent research has begun to explore network plasticity—or the ability of managers to change social networks to achieve organizational objectives.28 In contrast to structural theories, which focus on how network structures create constraints and opportunities for organizational actors, or naturalistic theories, which focus on how spontaneous forces shape network dynamics, these new agency theories focus on network change agents who sit outside and act upon the community or network of focus.29 For example, in their study of Levi’s jeans, Lester and Piore suggest that in the early, open ended stages of innovation, R&D managers must act as “cocktail hostesses”, bringing together the correct parties to the table, and helping facilitate the flow of conversation in order to be successful in their goal of promoting innovative new ideas.30 Likewise, in his longitudinal study of eight technology collaborations, Jason P. Davis found that managers of successful collaborations prune networks of existing ties that are information bottlenecks in the emerging network collaboration and, rather than rely on social processes, remake these networks with competency pairing, which forms ties between actors with complementary knowledge across organizational boundaries.31 This new research, in which managers have agency to change the shape of the existing network to achieve organizational objectives, suggests that a different, and more fundamental role may exist for the state in influencing technology development. Describing the role of the state in regional development in Western Europe, Ansell writes, “the state does not simply act as a mediator or coordinator, but also actively tries to create relationships between third-party actors”.32

While the existing network polity literature hints of such activities by the state, the empirical examples of the networked state contained therein are surprisingly similar. The majority of the examples are of the government playing a role in industrial or technology development in industrializing nations in the process of catch-up.33 In the few examples from developed countries, the role of the state is to connect firms to enable incremental innovation, support collaborative learning among firms, and help smaller firms catch-up, primarily in the context of regional economic development or upgrading in manufacturing.34 In nearly all examples, the state acts either by linking firms to facilitate increased economic transactions, dissemination of knowledge, and collaborative learning,35 or by linking individuals to build communities.36 Throughout these examples the state lacks an active role in identifying and influencing technology directions. Instead, the state, as a central node in the network, helps create network linkages, disseminate knowledge, or act as the breeding ground for communities without influencing the direction or content of discussions. To find an example of the state influencing technology directions one must turn to Japan—a country often characterized as a “bureaucratic” development state that chooses technology winners. And yet, Japan’s facilitation of research cooperation between competing firms echoes many of the themes written in the literature on the networked polity.37 Indeed, the literature on the Japanese government goes farther than what can be found in the networked polity literature on Europe, the U.S., and industrializing nations.

Daniel Okimoto describes the importance of the Japanese government’s focus on working with companies on consensus building,38 and on articulating long-term vision in the development of new technologies.39 Relatedly, Martin Fransman describes the Japanese government’s self-identified role in helping firms overcome the downfalls of “bounded vision” 40—i.e. the idea that different kinds of organizations (a) receive different kinds of information as the results of their primary activities, and (b) are limited in what they search for and “see” by the overall objectives of the organization. Here, according to Fransman, Japan believes that the limitations in the vision of for-profit firms and the vision of the government can be overcome by bringing the two together.41 Both of these themes are echoed in the case study presented here on DARPA.

Of course, organizational forms other than the state can also facilitate the connecting of disconnected agents and architect networks. As suggested by Dan Breznitz’s example of military training in Israel,42 education and training—such as being in common graduate programs—can build scientific communities and long-lasting networks. Conferences can act as venues for existing communities to contest and form agreement around the viability of competing technology directions.43 Firms, such as Intel, can orchestrate the co-development of technologically interdependent platforms across firms, universities, and government labs as is necessary to continue to advance their specific business model.44 None of the above pieces, however, are by themselves sufficient to seed and develop new technology directions that meet needs beyond the short-term market demands that drive firms. While communities developed through education and training may have common backgrounds, they do not, in and of themselves, have direction. While conferences can act as direction deciders, for a conference to play this role, the community must already exist. Finally, while firms may be able to play many of these roles as platform leaders, they will not have the same incentives as government (having a goal of profits rather than national security, economic growth, and social welfare), and their “vision”45 will be more short-term.

In this chapter, I leverage extensive empirical data to unpack an active, network-changing role of the state that goes beyond the previous literature on the place and application of a networked polity. First, I focus on cutting-edge, new technology development. In particular, I describe how in the development of new technologies, the state need not stop at merely bringing the appropriate actors together, nor must it go so far as choosing “focus industries” or “technology winners”, but rather it can leverage its knowledge centrality and ability to connect disconnected actors to identify and influence new technology directions that achieve its organizational goals.

Further, I describe a state that, in the development of a single new technology, leverages all of the earlier-described roles of network governance—from building new communities to community consensus-making on directions, to platform leadership outside of the constraints of firm incentives—to achieve its goals. Finally, I show that to find such a networked polity influencing technology development we need not look to Japan or to the late industrializing nations, but rather that this networked polity already exists in the U.S. To unpack existing practices, I turn to the pioneer of the U.S. Developmental Network State, DARPA.46

3. The Changing Faces of DARPA

Long-time defense analyst Richard Van Atta writes, “There is not and should not be a singular answer on ‘what is DARPA’—and if someone tells you that [there is], they don’t understand DARPA”.47 And yet, with so much success, it has been hard for analysts not to try to pin down the “DARPA model”. Van Atta himself summarizes the DARPA organizational environment into three key characteristics: (1) it is independent from service R&D organizations, (2) it is a lean, agile organization with a risk-taking culture, and (3) it is idea-driven and outcome-oriented.48

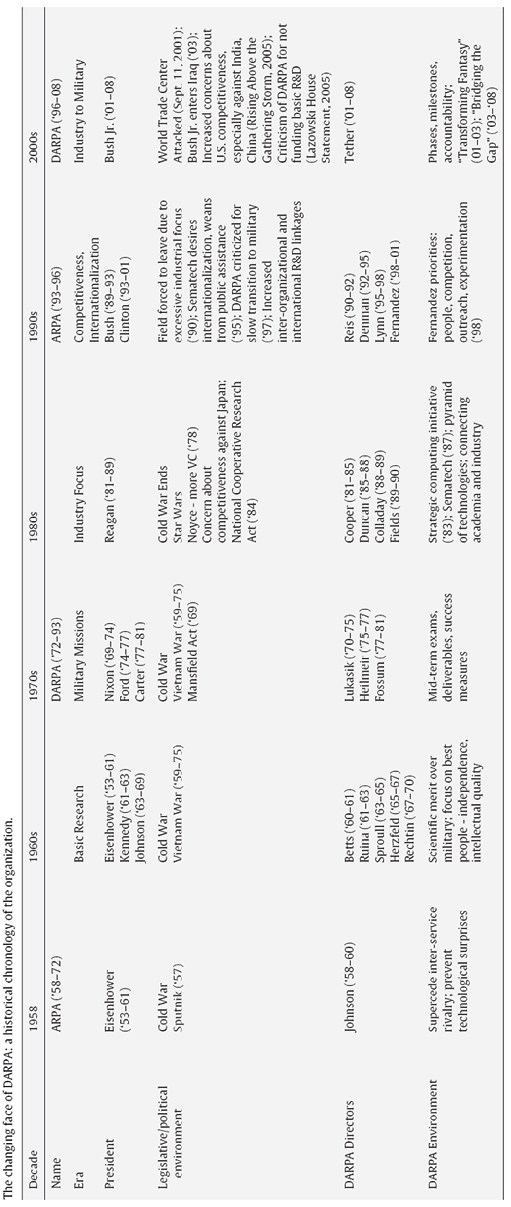

These themes are echoed in DARPA’s self-described twelve organizing elements, along with two additional themes—a focus on hiring quality people (“an eclectic, world-class technical staff”), and the importance of DARPA’s role in connecting collaborators.49 Others have suggested that DARPA’s “single customer” (the military) and “clear mission” (enhancing U.S. military capabilities) is a critical aspect of the DARPA model.50 And yet, as shown in the history that follows, the emergence, interpretation and actualization of these organizational features has evolved dramatically over the decades since DARPA’s creation in 1958. In many ways, these changes can be grouped into decade-based shifts, as shown in Table 7-1. In this paper, I focus on the shift initiated in 2001 by Tony Tether. To understand this shift, however, it is necessary to look back at the other shifts within DARPA across the previous decades.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) was founded under President Eisenhower in February 1958 by Public Law 85–325 and Department of Defense Directive 5105.41, as a direct consequence of the Soviet launching of Sputnik in 1957.51 Initially, ARPA was charged with preventing technological surprises such as Sputnik.52 Many blamed the advent of Sputnik on the rivalry at the time between the military services, and ARPA was set up to cut through that rivalry. After its founding, ARPA’s first priority was to oversee space activities until NASA was up and running and to screen new technological possibilities, shutting down those without merit.53 By 1960, all of ARPA’s civilian programs were transferred to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and all of its military space programs were transferred to individual Services. At this point, ARPA was forced to face the question of its longer-term role. President Eisenhower had always insisted that the Cold War was fundamentally a contest between two economic systems, and that it would be won or lost economically, not militarily.54 This perspective, in which the distinction between military and civilian technology was blurred, would stay with ARPA throughout the 1960s.

With space activity oversight behind it, ARPA focused its energies on ballistic missile defense, nuclear test detection, propellants, and materials.55 It was at this time that ARPA took on the role of bringing along military ideas that other segments of the nation would not or could not develop, and carrying them to proof-of-concept.56 ARPA’s goal was then to transition the technology out of the laboratory and into the hands of users or producers who would bring it to full adoption and exploitation.57

Table 7-1 The changing face of DARPA: a historical chronology of the organization. (Table prepared by the author.)

ARPA’s independent status not only insulated it from established service interests, but also tended to foster radical ideas and keep the agency tuned to basic research questions.58 When the agency-supported work became too much like systems development, it ran the risk of treading on the territory of a specific service.59 ARPA also established in the 1960s its critical organizational infrastructure and management style: a small, high-quality, managerial staff, supported by scientists and engineers on rotation from industry and academia, successfully employing existing DOD laboratories and contractors (rather that creating its own research facilities), to build solid programs in new, complex fields.60 Finally, ARPA emerged as an agency extremely sensitive to the personality and vision of its director.61

Following Army Brigadier General Austin Betts,62 Jack Ruina became DARPA’s third director in 1961 at the same time as President Kennedy took office. As director, Ruina cemented the agency’s reputation as an elite, scientifically respected institution devoted to basic, long-term research projects. Ruina believed that independence and intellectual quality were critical to attracting the best people, both to ARPA as an organization and to ARPA-sponsored projects.63 A Professor of Electrical Engineering on leave from the University of Illinois, Ruina valued scientific and technical merit above immediate relevance to the military.64 During his tenure, Ruina decentralized management at ARPA, and began the tradition of relying heavily on independent office directors and program managers to run research programs. To meet his goals for the agency, Ruina encouraged creative use of existing Department of Defense managerial mechanisms including “no-year money”, unsolicited proposals, sole-source procurement, and multi-year forward funding.65 Through the mid-1960s, DARPA remained committed to supporting basic research with long-term importance, even if there was no immediate military application.66

By the 1970s, however, the war in Vietnam had become the driving force at DARPA, tending to redirect research towards military purposes and raising concerns about the effect of defense funding on university research. Under President Richard Nixon, Congress forbade military funding for any research that did not have a “direct or apparent relationship to a specific military function or operations”.67 The legislation, which was enacted into law as the Mansfield Amendment to the Defense Authorization Act of 1970 (Public Law 19–121), was short-lived, but had the longer-term impact of shortening the time horizons for government research support, and in particular defense research.68 In keeping with the political times, ARPA’s name was officially changed to DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) in 1972. Then, in 1975, George Heilmeier became director of DARPA.69 Under Heilmeier’s directorship, all proposals needed to address six questions: (1) what are the limitations of current practice, (2) what is the current state of technology, (3) what is new about these ideas, (4) what would be the measure of success, (5) what are the milestones and the “mid-term exams,” and (6) how will I know you are making progress. In contrast to Ruina, Heilmeier led with a heavy hand, giving all DARPA orders a “wire brushing” to ensure that they had concrete “deliverables” and “milestones”.70 In short, Heilmeier viewed DARPA as a mission agency, whose goal was to fund research that directly supported the mission of the DOD.71

In the 1980s, with the Vietnam War over, defense concerns gave way to industrial competitiveness as the primary driver of research policy. The U.S. increasingly feared that the microelectronics and computer industries would go the way of the auto industry—to Japan. These fears were not unfounded. By the end of the 1980s Japanese semiconductor manufacturing equipment suppliers were gaining market share at a rate of 3.1 percent a year, and U.S. semiconductor manufacturers planned to purchase the majority of their equipment from Japanese suppliers.72 Given the heavy-handed role of Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), later renamed the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI), helping companies cooperate on new markets and technologies, there were increasing cries in the U.S. for government action.73

In 1984, the National Cooperative Research Act exempted research consortia from some antitrust laws and further facilitated collaborations. Then, in 1987, fourteen U.S. semiconductor companies joined a not-for-profit venture, SEMATECH, to improve domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The next year, the federal government appropriated $100 million annually for the next five years to match the industrial funding. DARPA had since the late 1970s been supporting the development of “silicon foundry” capabilities to allow cost-effective fabrication of new types of integrated electronic devices by designers lacking easy access to costly production facilities.74 With semiconductor manufacturing seen as vital to defense technology, the SEMATECH money was channeled through DARPA.75

This paper begins its story in the 1990s. During this period, the U.S.’s focus on international competitiveness grew, further distancing DARPA from its role with the military. In 1992, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney announced “a new, post-Cold War DOD strategy of spending less on procurement of new military systems, while maintaining funding for R&D to develop new technologies for building future systems and for upgrading existing systems”.76 The next year, the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) wrote, “Early stages of R&D, in which ARPA is most heavily involved (basic research through technology demonstration), will probably be least affected by reductions in defense spending” (following the cold war). The OTA continued, “Furthermore, based on military interests alone, ARPA will probably become more involved in the development of dual-use technologies. Despite the apparent divergence of military and commercial systems, many component technologies from which these systems are constructed continue to converge”.77 During the period from 1992 to 2001 DARPA was led by three directors—Gary Denman (1992–1995), Larry Lynn (1995–1998), and Frank Fernandez (1998–2001). During Gary Denman’s tenure, DARPA briefly dropped its “D” and returned to its original name of ARPA. Both Lynn and Fernandez continued Denman’s focus on basic research. Lynn was part of DARPA’s first inclusion of basic biology research into DARPA’s budget.78 Fernandez focused on quality and independence in a manner reminiscent of ARPA’s second director, Ruina.79

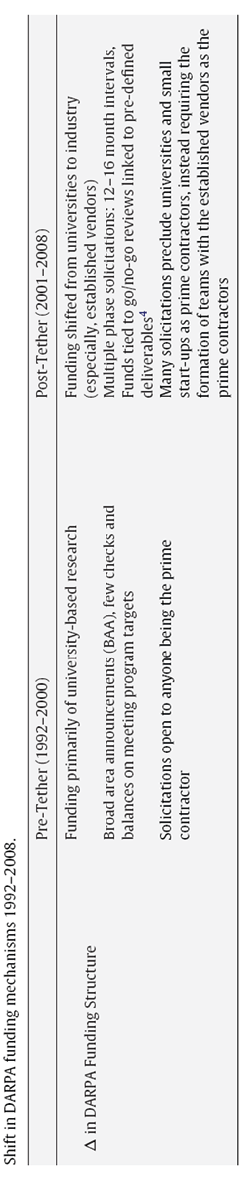

Table 7-2 Shift in DARPA funding mechanisms 1992–2008. (Table prepared by the author.)

On 20 January 2001, however, George W. Bush took office as the 43rd President of the United States, and DARPA’s focus on dual-use technologies came to an end. On 18 June 2001, Tony Tether was appointed as the new Director to head DARPA. Prior to becoming the director of DARPA, Tether had steadily risen in his career through a variety of military and industrial positions. Having served for four years as the director of the DOD’s National Intelligence Office (1978–1982), he came to the position of DARPA director under a directive from Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld that the new director must make DARPA “an entrepreneurial hotbed that will give the U.S. military the tools it will need to maintain the nation’s access to space and to protect satellites in orbit from attack”.80 Less than three months after Tether was appointed, the U.S.’s post-cold-war peace time landscape began to change. On September 11, 2001, two hijacked planes were flown into the World Trade Center in New York City, a third hijacked plane was flown into the Pentagon, and a fourth hijacked plane attempted an attack on Washington, D.C. In response, on 7 October 2001 the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, and on 21 March 2003, the U.S. began its invasion of Iraq. In his statement to the House of Representatives on 27 March 2003, Tether highlighted DARPA’s role in “bridging the gap” between fundamental discoveries and military use.81 This slogan, “Bridging the Gap”, was subsequently added to the official logo for DARPA.

During his time at DARPA, Tether made significant changes to the agency’s policies, shown above in Table 7-2, which brought on an outcry from the academic community, especially the computing community.82 Although overall DARPA funding remained constant, the proportion going to university researchers dropped by nearly half.83 In contrast to the flexibility and discretion given to researchers in the 1990s, funds under Tether were tied to “go/no-go” reviews linked to pre-defined deliverables—i.e. technical achievements defined either in the solicitation itself or by the researchers as part of responding to the solicitation—that must be achieved within a pre-specified time period (typically six to nine months).84 This focus on milestones and go/no-go reviews is reminiscent of DARPA policies under Heilmeier. In addition, DARPA raised the classification of research programs and increased restrictions on the participation of non-U.S. citizens.85 Most significantly, many solicitations precluded universities and small startups from submission as prime contractors, instead requiring the formation of teams and forcing startups and universities to team with large established vendors.86

Looking back over the decades since DARPA was founded, it is not immediately clear that the concerns expressed in the 2000s by the academic community with regards to DARPA being “dead” were warranted. Under Tether, DARPA did indeed shift its funding away from academia and, at the same time, shifted its funding model. However, change in DARPA’s immediate goals and the director-level rules on how to meet those goals, is common, if not the rule, over the DARPA’s history.87 With so much change, the puzzle is what is the DARPA model, and is there something fundamental about DARPA, across the decades, that its imitators should be copying? Past research has focused on DARPA’s organizational culture, structure, and goals as the critical and lasting features of the “DARPA-model”. In this paper, I argue that beyond these organizational features, there are informal processes used by the program managers to influence technology directions, which have been overlooked in past literature, and have been institutionalized so as to last through changes in directorship and organizational focus.

4. Methods

This paper uses grounded theory-building methods88 to unpack the processes by which DARPA influences technology development. I conduct a case study89 of four materials technologies critical to the advancement of Moore’s Law. Two of these technologies—SiGe and strained Si—received DARPA funding in the mid-nineties and were subsequently introduced into microprocessor designs and mainstream Si-CMOS production lines. The remaining two materials advances—3D packaging technology and integrated photonics—were funded under Tether and are identified by the ITRS Roadmap and in academic publications as potentially critical to meeting the targets set by Moore’s Law in the upcoming decade. All four of these technologies were supported by program managers within DARPA’s Microsystems Technology Office (MTO), which, until April 1999, went by the name of the Electronics Technology Office (ETO).90

In conducting my research, I triangulated participant observation, qualitative interview data, archival data, and bibliometric data to provide a holistic view of the forces driving technological change.91 My results draw primarily from fifty semi-structured interviews with DARPA office directors and program managers, industry representatives, and university professors who were involved in the development of SiGe, strained silicon, integrated photonics, and optical interconnects between 1992 and 2008. I identify key scientists and technologists in the “invisible college”92 in this technical area through a snowball effect based on names mentioned in early interviews and in news documents.93 I subsequently cross-checked this list using DARPA’s online archives for the period and identified additional DARPA program managers involved in funding these technologies. I executed the interviews so as to ensure that they included (1) DARPA MTO office directors and program managers from both before and after Tony Tether took the directorship, and (2) a representative cross-section of scientists and technologists from within academic institutions, startups, and the five established microprocessor vendors—Intel Corporation, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), International Business Machines (IBM), Hewlett Packard (HP), and Sun Microsystems (Sun). I also asked each respondent to provide an up-to-date biography and curriculum vita (CV), including a list of all of their publications and patents to-date in their career. I used these individual CVs to better understand the bibliometric records of each interviewee, as well as their co-patenting and co-publishing records with other scientists. I completed all interviews between September 2006 and October 2008.

I conducted several participant observations throughout the course of the study to gain insights into both the optoelectronics and microelectronics industries and DARPA’s role in technology development. Early on, I was able to conduct a three-hour participant observation of a DARPA-funded team in the process of developing its technology so as to acquire Phase II funding. I was also able to attend multiple industry conferences through-out the course of the study, due to my own prior technical activity in the area, through additional connections from my interviews, and through my ongoing professional activities studying the converging telecom and computing industry. These industry conferences included three of the Bi-annual Microphotonics Industry Consortium conferences (Fall 2007, Spring 2007, Fall 2008), Phontics North 2007, the 2007 IEEE Computer Elements Vail Workshop, the Optoelectronics Industry Development Association (OIDA) 2008 Annual Forum, and the OIDA Manufacturing and Innovation in the 20th Century Workshop in Spring 2008.

Finally, I have been able to draw on extensive archival data available through the Carnegie Mellon University libraries, online, and saved within the personal collections of David Hounshell. DARPA provides a wealth of archival data online, as well as through their technical archives. In addition, a host of information about both DARPA and company initiatives can be found in the popular press, congressional hearings, and in industry trade journals. Together, I use these online DARPA archives and available news sources to document DARPA solicitations, workshops, conferences, and press releases as related to the four materials technologies.

5. Results and Discussion

I present my results in three sections. In the first section, I unpack five distinct steps by which DARPA program managers seed and encourage new technology trajectories. This section draws exclusively on archival data and interviews with academics, industry members, and program managers before Tony Tether’s period as director, specifically between 1992 and 2001. The second section of the results then explores the changes within DARPA under Tony Tether. Here, I again draw on archival data and interviews with academics, industry members, and program managers but instead from 2001 to 2008. This section again proposes five methods by which DARPA seeded and encouraged new technology trajectories, and compares these methods, and the recipients of their efforts, to those found in the previous period. In the final section, I discuss overarching themes that emerge across the two periods and describe the role of the program manager.

5.1. DARPA in the 1990s (1992–2001)

Based on archives and interviews from academics, industry members, and DARPA program managers active during this period from 1992 to 2001, I identify five processes by which DARPA program managers during this period tap into existing social networks to seed and encourage new technology trajectories. These five processes are (1) identifying directions, (2) seeding common themes, building community, (4) validating new directions and (5) not sustaining the technology. I describe each of these processes in detail, and their significance below.

1) Identifying directions: To influence the direction of technology development so as to meet mission goals, a DARPA program manager must first identify the direction in which to go. To do this, DARPA program managers engage in three complementary activities: talking with mission directors to understand the needs of the military, bringing together elite scientists to brainstorm research directions that meet the needs of the military, and talking with existing researchers to understand emerging technology directions within the research community. The first activity DARPA program managers cannot escape. There are military liaisons in the DARPA building, who are senior officers, and have the role of connecting program managers with the needs of the military. In addition, DARPA program managers visit military installations around the country throughout the year to better understand military needs. The second and third activities, however, require greater agency on the part of the DARPA program manager. Below, I discuss the second activity—bringing together elite scientists to brainstorm research directions—and, in the next section, I discuss the third activity—talking with existing researchers to understand emerging directions.

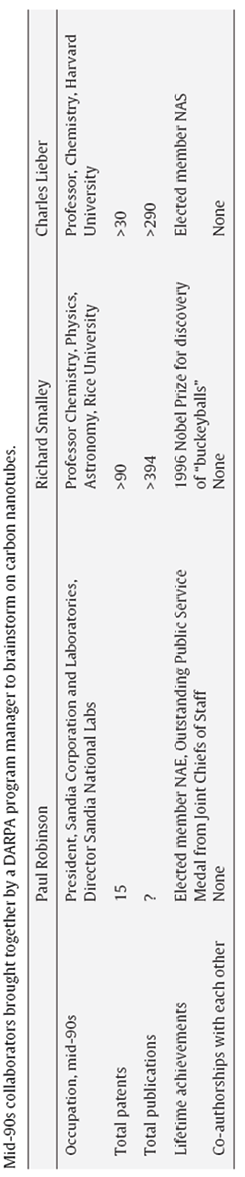

Table 7-3 Mid-nineties collaborators brought together by a DARPA program manager to brainstorm on carbon nanotubes. (Table prepared by the author.)

Over the years, DARPA has developed several formal institutions that enable DARPA program managers to bring together elite scientists to brainstorm research directions that meet the needs of military missions.

Among its formal institutions, most notable is the DARPA-Defense Sciences Research Council. The DARPA-Defense Sciences Research Council holds an annual summer conference that brings together “a group of the country’s leading scientists and engineers for an extended period, to permit them to apply their combined talents in studying and reviewing future research areas in defense sciences”.94 At this summer conference, top scientific and technical researchers in the country are exposed to major problems facing the U.S. military, and asked to identify technological directions to solve these challenges.

In addition to the Council’s annual summer conference, DARPA leverages several smaller task forces and technology groups. Each year following the Council’s summer meeting, smaller groups of Council members meet for Council workshops and program reviews, whose reports are made directly to DARPA.95 Other formal advisory activities include Department of Defense’s Defense Science Board (DSB) task forces, and Information Sciences and Technology Study Groups (ISAT).96 Like the Council’s workshops and program reviews, DSB97 and ISAT task forces can be called to address specific topics or challenges.

DARPA is not limited to holding these brainstorming sessions to identify directions within formal committees. Brainstorming sessions can also be called together by individual DARPA program managers, and can be much more informal. One DARPA program manager describes his role in bringing scientific leaders together around a common theme.

We were talking with Paul Robinson about the notion of building very high volume carbon nanotubes that were functionally matched… And I said, gee, Rick’s always been working in that area, let’s just call him in. Rick’s a Nobel Prize chemist. So we called him. He was there in two days. And so Lieber came over from Harvard. We sat around. And it was a great discussion.

The above-described interaction occurred in the mid-90s. Here, in supporting innovation DARPA program managers are the cocktail hosts described by Lester and Piore as necessary for the early-stage brainstorming of new ideas.98 The DARPA program managers select the members of the party, and help start the conversation necessary to brainstorm and identify the necessary new directions.

It is important, however, to look closer at the above quotation. As shown in Table 7-3, all of the people at the above-mentioned gathering, with the exception of the DARPA program manager, could be characterized as Lynne Zucker’s and Michale Darby’s “star scientists”.99 None of them, however, have bibliometric or other paper trails of intellectual ties with each other. These results are in striking contrast with the majority of social networks research, which focuses on documenting collaborations through patent co-authorships. These early-stage, informal, roundtable technical conversations are the type of conversations that cannot be found in bibliometric studies. Further, it is in precisely these formative conversations where the state’s involvement in bringing together the right parties may be particularly influential in determining future directions.

2) Seeding common research themes: DARPA program managers do not stop at a series of brainstorming session with elite scientists. In addition, DARPA program managers are continually returning to the field to find emerging projects and capabilities within the research community. In this role, they not only identify additional research directions, but also encourage research in those directions by funding researchers working on common themes that have the potential to contribute to military needs. Further, in contrast to the brainstorming sessions, in this field-based activity of identifying emerging directions and encouraging research in those directions, the DARPA program manager need not necessarily, or at least immediately, bring everyone into the same geographic space.

One DARPA program manager explains,

So I’ll tell you the SiGe story… So, the first guy to show me this, actually two guys,… was the guy who founded Amberwave. He showed me this is possible. And then Jason Woo and UCLA,… he showed me a plot of bandgap as a function of percent Ge. And he had two plots. He came to DARPA. And he said, look, there is a dependency, here it is, it follows band gap theory… And I said, “Jason, two dots don’t make a program… I need a third dot”. And he faxed me a chart the next day… So I sent him a small seeding.

At the same time I called Bernie (a fellow at IBM), and I said, “Bernie, have you ever seen this bandgap dependency in SiGe? You know, do you think it’s something we can exploit?” He said, “Funny you should ask. We’ve been looking at the same thing, and we’ve got some ideas as well”. So I funded him $2 million or whatever it was.

In this function, the DARPA program manager is neither acting as a broker—connecting otherwise disparate actors; nor as a boundary-spanner—identifying, translating, and relaying information across firm, cultural, or technical boundaries; in the traditional sense.100 Instead, the DARPA program manager is using his connections with researchers to identify emerging directions and capabilities within the research community, and seed-fund common themes across these disparate researchers. While the program manager is perhaps relaying some knowledge about the one researcher to the other or about general activities in the technical community, at first, he may be the only connection between them.

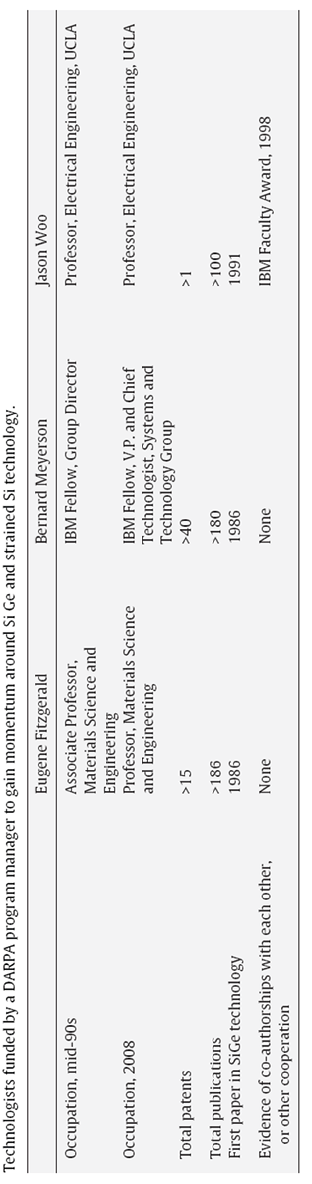

Table 7-4 Technologists funded by a DARPA program manager to gain momentum around Si Ge and strained Si technology. (Table prepared by the author.)

Upon closer scrutiny of the above quote, these results also have a second significance. Specifically, similar to the results in section (1), background research on the technologists referenced by the DARPA program manager in the above quote, show both Eugene Fitzgerald (“the guy who founded of Amberwave”) and Bernard Meyerson (“Bernie”) again to be what Zucker and Darby would classify as star scientists101 (see Table 7-4). Thus, this DARPA program manager is describing his contact with three star scientists, working in the same area. These results are significant given Zucker and Darby’s findings that star scientists are very protective of their techniques, ideas, and discoveries in their early years, tending to collaborate most within their own institution, which slows diffusion to other scientists.102 Assuming Zucker and Darby’s findings are correct, here, the sole connecting person, who is aware of all three of the star scientists’ activities, may be the DARPA program manager (Table 7-4).

Finally, it is worth noting that in playing out this role of seeding common research themes across disparate researchers, the DARPA program manager does not always fund the same technologies. At times, DARPA program managers fund competing technologies aimed at solving the same problem. The same program manager explains such an example in a different funding situation,

Take the case of thin-film technologies. In that case I funded two parallel programs. I funded IBM, because they were convinced that the parallel junction for thin-film SOI wasn’t going to go on forever, and they wanted more thick-film SOIs for the company manufacturing purposes. And then I funded Lincoln Labs to do thin-film SOI… I pitted Lincoln against IBM… So, they both succeeded, and IBM is still manufacturing thick-film SOI today.

3) Building community: increasing information flows, growing the base: DARPA’s role in seeding disparate researchers working on common research themes (whether the same or competing technologies) has a second significance. In receiving funding from DARPA, researchers are required to present to each other in workshops, thus further increasing the flow of knowledge between star scientists during early-stage research. Fitting with their classification as star scientists, neither Fitzgerald nor Meyerson—who are at different institutions—have ever co-patented or co-published. Yet, through DARPA, Fitzgerald and Meyerson were brought together in workshops to present to each other their research. What would otherwise have been knowledge kept within their organization was forced at some level (with the exception of some company-proprietary details which are presented solely to the program managers) to flow between the two. In funding disparate researchers, DARPA program managers promote the sharing of knowledge between star scientists, who left to their own devices would, according to the literature, tend to be very protective of their knowledge. In some cases, these workshops may even lead to new collaborations. Jason Woo, for example, started in the field somewhat later than Fitzgerald or Meyerson (1991), and, as the 1998 IBM Faculty Award he received suggests, may have even developed a relationship with IBM through his funding from DARPA.

4) Providing third-party validation of new technology directions: in addition to DARPA program managers’ roles in bringing researchers together to brainstorm new technology directions, seeding disparate researchers to gain momentum around those directions, and bringing those researchers together to share their results, DARPA program managers play a fourth role in technology development. Specifically, DARPA program managers’ funding actions act to provide external validation for new directions. One program manager explains, “So the DARPA piece, while large, was the validation for IBM to spend their own money”. He continues, “The same way for the Intel piece. You know, Intel certainly looked at that project, and then Intel ended up funding it internally, but the fact that DARPA went back to them three and four times and said, this is an important thing, this is an important thing, you know, it got to the board of directors, and it got high enough that they set up a division to do this”. A university professor makes the same point with respect to DARPA’s role with other funding agencies, in this case NSF. The professor explains, “See, once you’ve gotten funding from DARPA, you have an issue resolved, and so on, then you go right ahead and submit an NSF proposal. By which time your ideas are known out there, people know you, you’ve published a paper or two. And then guys at NSF say, yeah, yeah, this is a good thing”. He continues, distinguishing DARPA’s place within the broader U.S. government system, “NSF funding usually comes in a second wave. DARPA provides initial funding”. As a consequence, he concludes, “DARPA plays a huge role in selecting key ideas” (from among the broader set of ideas present in the research community).

5) Avoiding reliance on the state: Finally, despite DARPA’s role in validating new technology directions both to other funding agencies and in industry, DARPA program managers from the 1992–2001 period take note to point out that DARPA is not the “sustaining piece” in commercializing a new technology. As one DARPA program manager explains, “So we ran all of these design- of-experiment concepts, and you know,… we were doing great stuff, really good science. But the tipping point,… is the fact that IBM saw the value in this to the point that they started investing in it”.

This emphasis on the state not sustaining technology is an important final piece. Past research has warned of the tendencies for companies to become reliant on support from the state.103 History suggests that DARPA has had many successes transitioning subsequent development and production of its early-stage technologies to commercial (e.g. laser,104 the Internet,105 and the personal computer)106 and military (e.g. F-117A, Predator, Global Hawk)107 organizations. Future research should explore DARPA program manager’s mechanisms for transitioning technology development, and how they handle technologies that do not transition.

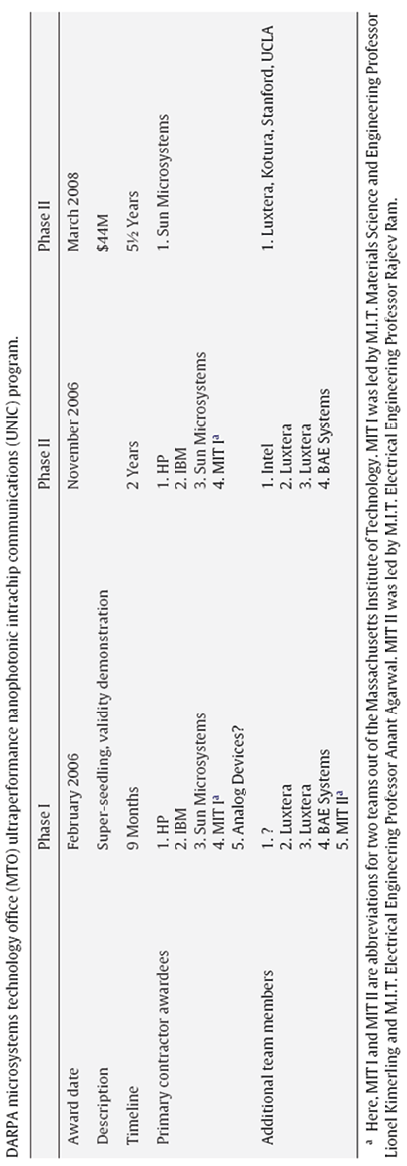

Table 7-5 DARPA Microsystems Technology Office (MTO) Ultraperformance Nanophotonic Intrachip Communications (UNIC) program. (Table prepared by the author.)

a Here, MIT I and MIT II are abbreviations for two teams out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MIT I was led by M.I.T. Materials Science and Engineering Professor Lionel Kimerling and M.I.T. Electrical Engineering Professor Anant Agarwal. MIT II was led by M.I.T. Electrical Engineering Professor Rajeev Ram.

5.2. DARPA under Tony Tether (2001-present)

Tony Tether was appointed director of DARPA on 18 June 2001. As discussed above, Tether made many changes within DARPA, which were poorly received from the academic, and particularly the computing, community. These changes included shifting funding from universities to industry (especially, established vendors); changing funding solicitations from broad agency announcements with few checks and balances to announcements with go/no-go reviews linked to pre-defined deliverables; and precluding universities and startups as prime contractors on many solicitations, instead requiring the formation of teams with established vendors as the prime contractors.

These changes in the framework of funding at DARPA can best be understood by looking at a program during this period.108 One such program, DARPA’s Ultraperformance Nanophotonic Intrachip Communications (UNIC) program,109 is outlined in Table 7-5 above. As shown in the table, the UNIC program consisted of three phases. The first phase lasted nine months. To pass this phase the program required the “development, fabrication, and demonstration, of silicon nanophotonic devices”. The second phase was two years. This phase was focused on designing and validating photonic networks between the devices developed in phase I, and “established the credibility of the technology within the microprocessor community”. Program submissions were required to establish “interim milestones every six months”, associated with “demonstrable, quantitative measures of performance”. As shown in Table 7-5, with the exception of one team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT I), established companies, like HP, IBM, and Sun Microsystems, were placed in the position of prime contractors, while universities (MIT II, Stanford, UCLA) and startups (Luxtera, Kotura) were members of the contractor-led team.

And yet, despite these dramatic changes under Tether in the framework of funding at DARPA, as shown in the upcoming section, the five processes by which DARPA program managers influence technology directions have remarkably remained the same. The recipients of these processes, however, and as a consequence, the implications, have changed significantly (Table 7-5).

1) Identifying directions: As in the 1992–2001 period, to identify new technology directions that meet military needs, DARPA program managers in the 2001–2008 period engaged in three complementary activities: talking with mission directors to understand the needs of the military, bringing together elite scientists to brainstorm research directions that meet military needs, and talking with existing researchers to understand emerging technology directions within the research community. As there are no changes in their activities talking with mission directors, I skip that discussion here. I discuss the program managers’ activities bringing together elite scientists to brainstorm research directions that meet military needs briefly below. I discuss program managers’ activities talking with existing researchers to understand emerging technology directions within the research community in the next section.

Based on the empirical data to which I had access, nothing changed within the formal institutions used by DARPA program managers for bringing together elite technology leaders to brainstorm new technology directions. The same institutions as were used during the 1992–2008 period, existed and were used throughout the 2001–2008 period. For example, a February 2005 DSB task force focused on High Performance Microchip Supply, a topic of great interest to DARPA, and around which the Microsystems Technology Office had several solicitations. What I could not tell from my empirical data, was whether the composition of these brainstorming sessions may have changed after Tether took on the directorship. In particular, while I was able to access nearly half of the DARPA-Defense Sciences Research Council summaries for the pre-Tether period (1992, 1993, 1996, and, 1997), I was not able to gain access to any of these summaries from the period after Tether took office. While this lack of public access to these reports could be representative of increased classification of research programs during this period, it also could be that the 2001–2008 period is more recent, and these summaries have simply not yet been released.

2) Seeding common themes: orchestrating the involvement of established vendors with academics and startup companies: As from 1992 to 2001, DARPA program managers during 2001–2008 did not stop at a series of brainstorming sessions with elite scientists. Instead, program managers continually return to the field to find out emerging directions and capabilities within the research community. As described in Section 5.1. of this chapter (“DARPA in the 1990s (1992–2001)”), the DARPA program managers need “vision”, but not necessarily the original ideas.

One program manager explains, “This is an opportunity that people will actually tell me their best ideas and we can see what we can do with those. It’s really amazing in that sense”. Another program manager clarifies, “I was not working in a vacuum, right?” He continues, “[I would ask people], ‘Can you provide this functionality? Can you provide that functionality?”’ This probing and testing of the research community to explore what is possible in a given technology—here silicon photonics, mimics the same probing being done by the program managers in the 1992–2001 period, in the case quoted, in SiGe.

As discussed in Section 5.1., at times DARPA program managers fund disparate researchers doing similar research for achieving a particular end-goal, and at other times, DARPA program managers fund competing technologies for achieving a particular end goal. One DARPA program manager suggests, “I think our best [programs] are the ones where there’s multiple solutions to a common problem”. He explains that in one program, “I have six performers and the reason I have six is because I was able to convince the Director that this is an extremely high-risk effort. I don’t know which technology or which architecture is going to win, if any… [But], if you give me four and they all fail, maybe you left the wrong two out”. This theme is echoed in the first program manager’s comments, “I wanted to have three or four ideas that I could say, ‘Look… here are paths we could go along. I don’t know which if any of them will be successful.’… if I didn’t have those, then I cannot go and sell the program”.

In their continual connection with the field, DARPA program managers not only identify additional research directions, but also encourage research in those directions by funding researchers working on common themes that have the potential to address military needs. In seeding disparate researchers around common themes, the DARPA program manager is neither a broker nor a boundary-spanner. Rather, he takes in ideas from the existing research community, identifies directions, and then funds disparate researchers working on common themes that hold potential in contributing to achieving an end-goal. He synthesizes emerging ideas into common themes. He integrates common themes into directions to meet military goals. Finally, he directs researchers along these directions through carefully crafted funding solicitations.

The disparate researchers in the 2001–2008 time period are, however, very different than those funded in the period from 1992 to 2001. Where in the first time period the disparate researchers were star scientists, in the latter period, the disparate researchers are teams of startups, universities, and prime contractors. A startup company founder described his interactions with DARPA’s program managers, and the role the program managers played in encouraging research in the academic and industrial communities around their ideas: “So DARPA has program managers, and we were talking to them, and they got excited about this project, and they said, let’s try to get a program out. So we worked with… the DARPA program manager, and they got interested in the field, and they got a program out of this. They got a bunch of other people involved in the program”. Here, the “other people” are the companies and universities for the UNIC program shown in Table 7-5.

Unlike in 1992–2001, when startup companies would have been funded directly, in 2001–2008, startup companies were frequently not able to be the primary contractor on a proposal. In the case of the above startup company, the company needed to team up with an established vendor to receive funding for the project. Describing this process, the program manager clarifies, “I have never… said, ‘I want you to work with these two.’” He clarifies, “You have to structure the solicitation in such a way that… they would do that on their own”. The program manager goes on to describe this system-level goal, “There was one… condition imposed on [the teams], and that was that these things must be developed in a… foundry compatible process”. He explains, “I don’t want people to go out and do something in the basement, and say that, ‘Ah, I produced the best results in the world,’ in a process that is totally incompatible with anything else that the industry does. Because the whole idea here was to leverage the industry’s path down the road of smaller and smaller devices”. While at first glance, this requirement for established vendors to be the primary contractors may seem limiting, it may also have an important purpose. In particular, recent research has shown that with the decline of corporate R&D labs and the vertical fragmentation of industries, firms today face new challenges coordinating across firms when advancing technology platforms,110 aligning incentive structures across these interdependent firms,111 and supporting long-term research within such ecosystems.112 By leveraging his birds-eye view of research in the community, the DARPA program manager can help ensure that technical activities being engaged by disparate entities, such as startups, in the vertically disintegrated framework fit in the broader industry picture.113

3) Building community: supporting knowledge flows between competitors and enabling technology platform leadership at the systems level: As seen in Section 5.1 of this chapter, DARPA’s role in seeding disparate researchers working on common themes has a second significance. In receiving funding from DARPA, researchers are required to present to each other in workshops, thus further increasing the flow of knowledge between researchers working on common themes. Under Tether, DARPA funding recipients are required to attend and present to each other in workshops at the end of each go/no-go program phase. However, in contrast to the 1992–2001 period, where institutionally isolated start scientists were brought together, in the 2001–2008 period, these researchers are established vendors and their teams of startups and university professors. In response to a presentation of an early proposal for this work, which I gave at an industry conference, one university professor angrily responded, “I can tell you what you’ll find. I was there (at the DARPA workshop), and they’re (the companies) all presenting to each other what they’re going to do. They’re all talking to each other. And they’re all doing the same thing”. And yet, in the case of established vendors, DARPA workshops may provide them with a critical opportunity to share new ideas and agree (implicitly or explicitly) on technology directions. One industry respondent explained the importance of such an opportunity to coordinate in today’s industry environment, “You just can’t make anything happen in industry (today) on your own, because it’s completely impossible. You have to find a partner, you have to convince your competition this is the right thing to do”. He continued, “You’re guiding people [your competitors]… and they ask, ‘Why are you helping me with this?’ and the fact is you give them information so the suppliers are in the right place to help you”.

DARPA is not only supporting the coordination of technology directions across competitors. By encouraging teams of startups, universities, and prime contractors, DARPA may also be helping coordinate technology directions in a vertically fragmented industry in a second way. One established vendor emphasizes both the importance of DARPA’s systems perspective and of DARPA giving the established vendors power by making them the primary contractors. He explains, “Here, the technology is being driven by the systems companies. Very few companies have the resources to do system-level exploration without DARPA funding. DARPA funding is enabling the system players to determine the direction of this technology. If you don’t get the system guys involved, you end up getting widgets that don’t work in the bigger picture”.

This system-level goal is already hinted at in Section 2 (“The Developmental Network”) by both the startup company—which notes that DARPA “got a bunch of other people involved”, and by the DARPA program manager—who emphasizes the importance of developing new technologies compatible with the established industry platform. Finally, another established vendor emphasized the importance of DARPA’s longer-term vision in supporting technology trajectories across the vertically disintegrated industry, saying, “You need someone with a longer-term horizon. Ten years from now, we want a teraflop of computing. But we don’t have more than a six-month time horizon”.

With the decline of corporate R&D labs and the vertical fragmentation of industries, firms today face new challenges in establishing appropriate sources of new inventions and in coordinating subsequent technology development across the myriad of affected firms. Recent research has documented challenges in the coordination across firms in advancing technology platforms,114 in aligning incentive structures across interdependent firms,115 and, in particular, in supporting long-term research within such ecosystems.

Within DARPA between 1992 and 2001, the mandate to present early-stage research in DARPA workshops encouraged star scientists to divulge information that they might otherwise have kept confidential within their institution, and thereby helped align them on similar trajectories. In contrast, in the case of DARPA under Tether, the teams DARPA forms between universities, startups, and established vendors, and its subsequent mandatory workshops are supporting the coordination of technology trajectories across a vertically fragmented industry and the alignment of long-term technology trajectories.

4) Providing third party validation for new technology directions: As during 1992–2001, DARPA also played a fourth role in technology development from 2001 to 2008. Specifically, it provided external validation for new directions. Under Tether, instead of DARPA’s funding providing validation to industry and NSF for latter-stage funding and commercialization, it instead validates technology directions within the vertically fragmented industrial ecosystem. This validation of a new technology can be particularly helpful for startups. The CEO and founder of one startup described the challenge of breaking into the broader industry knowledge network, saying, “[In contrast to a large company or M.I.T.],… as a small company, you have to develop a contact. Headhunters… [can] also bring information to you. We are starting to discuss with (large systems vendor)… They’re trying to keep us developing pieces of technology they need”. Another startup founder emphasizes the importance of DARPA’s validation. He explains, “[Venture capital] investors are highly motivated to see the company succeed. As a consequence, they will lie through their teeth about what the company can do. DARPA funding and ATP funding [funding from the Commerce Department’s former Advanced Technology Program] have the added benefit of communicating to a third party a validation of the technology”.

5) Breeding reliance on the state? Finally, like the DARPA program managers from 1992 to 2001, DARPA program managers from 2001 to 2008 were concerned to not become the sustaining force for any technology. Under Tether, DARPA program managers were particularly encouraged to focus on the last step of transitioning the technology to the military and (or) to industry. As one program manager explained, “The third phase is a very important phase usually… it’s the last phase… [It] defines how you will transition the technology in this office, say, to somewhere else”. He continues, “Dr. Tether pays extra attention to your plan for Phase III”.

And yet, some members of the industrial community whose positions involved shorter term time horizons and the pressing realities of commercialization expressed caution about participating in DARPA-based activities. One established computing vendor explained, “So, <my company> as a whole has just shied away from government funding… <Our company> labs, or whatever, they’ll get a little DARPA funding, but most of that is, has never, produced anything of value, from a… commercial perspective. That wasn’t saying it wasn’t of value within the industry, but just trying to delineate”. A startup company CEO and founder expressed similar concerns, “Sometimes I’m very nervous about getting too much focus on defense money. I don’t want to lose track of the fact that I’m developing products, not technology”. He continues, “DARPA is funding the industry so far ahead. If you’re developing for 10 years from now, DARPA is great. But how do you manage not to lose revenue unless the market is starting in now… Some of the technology developed for the next generation—I don’t know if it is applicable that well to (now). I’m not sure DARPA’s direction is the direction to go”. He concludes, “I think… <my company> is ideally placed for (today’s technology). But, admittedly, not necessarily for the long term”.

These results do not conflict with the supportive comments made by established computing vendors in Section 3. (“The Changing Faces of DARPA”) above. Rather, they help underscore DARPA’s role in coordinating longer term technology trajectories, while not being accepted by industry for coordinating technologies required in the shorter term. Notably, while the interviewee was not participating in any DARPA-funded projects, the labs at the same established computing vendor were participating in DARPA contracts from the Microsystems Technology Office at the time of the interview.

Further, the concerns expressed by the above established vendor and startup founder may not be unwarranted. A recent study on awards from the Small Business Innovation Research Program (SBIR) by the National Academy of Sciences shows that while small businesses receiving government funding are good at achieving mission goals, they are frequently not successful at surviving in the long-term or at technology commercialization.116 Since the time of the interview, the above-described startup has joined an established vendor’s team, and acquired DARPA funding for developing the longer-term technology. Most recently, as part of the UNIC program described in Table 7-5, Sun Microsystems received a $44 million contract for the next five years to continue to develop the photonic system-on-a-chip technology. Whether or not some startups and established vendors who were involved in DARPA funding during the Tether period end up developing a reliance on the State, will remain to be seen.

6. Discussion: the DARPA Program Manager—Embedded Network Agent

Key to understanding DARPA’s role in influencing technology directions is understanding the role of the program manager, not as someone who “opens windows” to which researchers can bring funding ideas,117 nor merely as a “boundary spanner” (and possibly a “broker”) who connects different communities,118 but rather in a more active role. The nature of this role makes it difficult to describe, as it comes through in the seemingly conflicting descriptions of the DARPA program manager role by members of the research community. One former office director explains, “It really comes down to the program manager. A program manager that has a passion for an idea, that understands the technical elements of an idea, and has some vision for where it might go”. On the other hand, industry and academic researchers consistently describe themselves as the people with the ideas, and DARPA program managers as the people who funded them, provided legitimacy, and helped provide the funding and community support to bring the vision to fruition. In the words of one university professor, a DARPA program manager would “touch” on “people like [professor’s name] and others he knew well, and [say] ‘hey, help me, give me the ideas.’”

This seeming inconsistency, however, can be resolved through the DARPA program managers’ own description of their role. As a former member of the research community who suddenly rises in status and holds the promise of money, the DARPA program manager becomes a central node to which information from the larger research community flows. In this role, the DARPA program managers are in constant contact with the research community, bringing people together to brainstorm new directions, understanding emerging research themes, matching these emerging themes to military needs, “betting on the right people”, connecting disconnected communities, standing-up competing technology solutions against each other, and maintaining the system-integrating view. In executing these tasks, they must, indeed, have “vision”, but this vision does not necessarily involve themselves having the ideas. In the words of one program manager, “There were people around who I could go [to] and talk to [and] see what their ideas were… What they could do”. Program managers from both periods, 1992–2001 and 2001–2008, describe this same idea-seeking behavior.

Most importantly, DARPA program managers conduct all of these activities, without explicitly choosing the technology winners. At times they seed disconnected researchers working on common themes—whether with the same or with competing technologies—that hold potential to meet military needs. As the DARPA program manager from the preceding paragraph explains, “So obviously… I would not propose a program if there were no ideas [among researchers] that would address the challenges that we [at DARPA] had to address. I just didn’t know what… particular idea would work”. He continues, “But I wanted to have three or four ideas that I could say, ‘Look,… here are paths we could go along. I don’t know which, if any of them, will be successful.’… if I didn’t have those, then I cannot go and sell the program”. In other cases, they bring together disconnected researchers, whether to brainstorm directions, to work together (on teams), or to learn from each other (in workshops). As described by a program manager from the 1992–2001 period, “You get communities together that don’t naturally talk and you give them some latitude and some life, and you push them forward and see what comes out of it”. In this situation, “Conversations were often… one-upmanship… You know, sort of realizing what other people were doing and you’d reset your goals, and you’d kinda all move. And the role of the program manager was kind of to keep the band marching down the street”. Finally, throughout these activities, whether bringing together members of research communities that may not normally talk, or funding an entire suite of technologies necessary to meet an integrated outcome, DARPA program managers contribute a system-level perspective to organizing national R&D. As one program manager from the 1992–2001 period explained, “… we were able to broaden it out, do the VLSI, do the hardware, acceleration, do all the stuff [necessary to advance Moore’s Law] and sure enough we stayed on that ops curve and we were pulling the industry along”. The same systems-level view is seen in the 2001–2008 period.

Thus, while the DARPA program manager is, indeed, sometimes a broker—acting as the only connection between disconnected researchers or communities—and sometimes a boundary spanner—connecting communities to support the development of a new field—his role is much more active than that prescribed to these positions in previous literature. The DARPA program manager is not only a connector, but also a conductor and a systems integrator. He comes to his position through his prior social capital and position in the network. Once in this position, he holds and leverages particular powers. Yet, what is most significant, is the deliberate role the DARPA program manager plays in changing the shape of the network once in this position, so as to identify and influence new directions for technology development.

7. Conclusions

Several years after Tony Tether took office, popular press articles began suggesting that the U.S.’s great engine of technology change—DARPA—was “dead”.119 Drawing on a case study of DARPA’s Microsystem’s Technology Office from 1992 to 2008, I argue that this perceived death is because past analyses have, by focusing on the organization’s culture and structure, overlooked a set of lasting, informal institutions among DARPA program managers. In the case of DARPA’s Microsystems technology office before and during the directorship of Tony Tether, what changed is not the processes used by the program managers, but rather the situations to which program managers apply these processes. Prior to 2001, DARPA’s processes for seeding and encouraging new technology trajectories involved (1) bringing star scientists largely from academia together to brainstorm new ideas, (2) seeding disparate researchers around common themes, (3) encourage early knowledge-sharing between these star researchers through workshops, and (4) providing third-party validation for new technology directions to external funding agencies and industry. By identifying ideas across, bringing together, and seed funding star scientists (who may otherwise institutionally isolate their knowledge) around common themes, DARPA was able to support the sources of, knowledge flows around, and development of social networks necessary for initiating new technology directions in early-stage research. In contrast, since 2001, the DARPA program manager’s processes for gaining momentum around new ideas involve (1) orchestrating the involvement of established vendors with academics and startups, (2) supporting knowledge-sharing between industry competitors through invite-only workshops, (3) providing third-party validation of new technology directions to a vertically fragmented industry, and (4) supporting technology platform leadership at the system level. Here, DARPA is supporting the coordination of technology development across a vertically fragmented industry in whose direction the military has interest and in which long-term coordination of technology platforms is particularly challenging.

These results suggest a new form of technology policy, in which embedded government agents re-architect social networks among researchers so as to identify and influence new technology directions in the U.S. to achieve an organizational goal. In this role, these agents do not give way to the invisible hand of markets, nor do they step in with top-down bureaucracy to “pick technology winners”. Instead, they are in constant contact with the research community, understanding emerging themes, matching these emerging themes to military needs, betting on the right people, connecting disconnected communities, standing up competing technologies against each other, and maintaining that birds-eye perspective critical to integrating disparate activities across our national innovation ecosystem.

Acknowledgements