2. Learning a Dead Birdsong: Hopes’ echoEscape.1 in ‘The Place Where You Go to Listen’

© Julianne Lutz Warren, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0186.02

Prelude

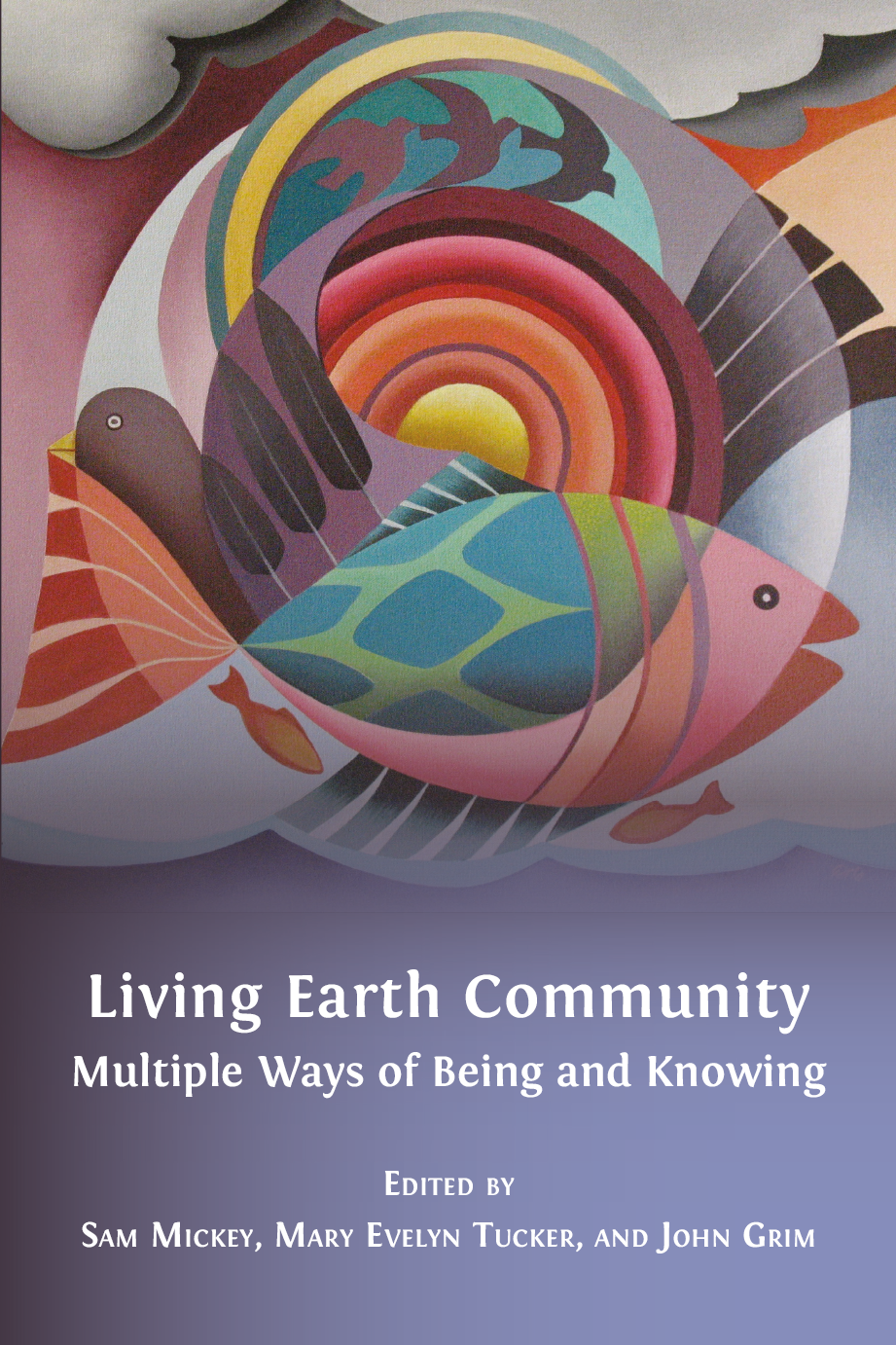

It was spring of 2011. I was searching for something else in Cornell University’s archive of sounds when I first came across a sixty-three-year-old recording of a Māori man whistling his memory of songs of Huia.1 These tones both cut and enchanted me. In 1948, these birds were already believed to be extinct. Huia — whose distress notes speak in their onomatopoeic given name2 — were endemic to Aotearoa New Zealand. The elder Huia mimic — Henare Hamana (aka Henare ‘Harry’ Salmon 1880–1973) of the Ngati Awa hapu of Warahoe — had been invited into a Wellington recording studio by a Pākehā,3 a neighbor called R. A. L. (Tony) Batley (1923–2004) (see Figure 3.1). Batley, who also narrated the recording, was a regional historian from Moawhango settlement. He was interested in preserving this remnant of remembered avian language. The birds were, as Batley puts it in the recording, ‘of unusual interest’. For instance, all Huia had ivory-colored bills, but they were curiously dimorphic in shape. The bills belonging to males were generally shorter and more like ‘pick-axes’ than females’ bills, which were long and curving. Both sexes were crow-size, with black-green bodies and a dozen stiff tail feathers edged, again, in ivory. Against the darkness of dense native trees and ferns filtering sunlight, the bright trim on each bird leaping between low limb and earth must have arced like coupled meteorites through a night sky.

Fig. 3.1 Transcription of R. A. L. (Tony) Batley’s recording, by Dr. Martin Fellows Hatch, Emeritus Professor, Musicology, and Dr. Christopher J. Miller, Senior Lecturer/Performer, Cornell University (2015).

Huia became extinct due to complex human causes that were local, but globally common due to expanding colonization. Huia range likely contracted, then stabilized, after the arrival of Māori ancestors around a millennium ago. A couple of hundred years of European settlement escalated stresses on the birds. Ecological communities of old-growth forests co-evolved with Huia were widely cut-down and disrupted by newcomers’ with industrial and capitalist assumptions. These underpinned an overpowering system of cropping and livestock-grazing alongside an influx of unfamiliar avian predators and parasites.4 These wide-scale harms in turn alienated Māori from customary relationships as Tangata Whenua5 (People of the Land), a worldview basis of cultural identity and Indigenous authority entwined with language and the health of the land, Huia included. Generations of Māori had learned to attract Huia, who were tapu6 or sacred, by imitating the birds’ voices. Māori had ritually snared Huia for tail feathers — which were sometimes given as gifts — and other ceremonial or ornamental parts. Huia may have sometimes been eaten. These birds emerged in ancient cosmology and conveyed messages in living dreams. With the privileging of British economic valuations, mounted Huia skins and tail feathers became commodified and sold internationally, which increased the rate at which they were killed by both Māori and Pākehā hunters. By the end of the nineteenth century it had become evident to observers across cultures that Huia had been brought to the brink of extinction. Some Māori, particularly Ngāti Huia, placed their own protections on Huia range, protecting the birds. In response to the hapu’s appeal, in 1892, the Crown government also extended its Wild Bird Protection Act to Huia.7 One idea set forth by this government officials was to capture Huia pairs in their North Island home range and move them to offshore island sanctuaries: Hauturu Little Barrier Island and Kapiti Island were possible destinations.8

Fig. 3.2 NGA HURUHURU RANGATIRA, sculpture by Robert Jahnke (2016), Palmerston North, New Zealand. Photograph by Julianne Lutz Warren (2016).

By the time expeditions were arranged with this intent of rescuing Huia, it was apparently too late. Both Batley and Hamana had been engaged in one or more Huia searches led by Dominion Museum officials (now Te Papa Tongarewa). Hamana was known for his bush skills, including imitating the birds. In 1909, he joined one of those Crown-official parties tramping into the still-dense forest in the Mt. Aorangi-Mangatera Stream area some miles from Taihape.9 Reports of this expedition vary. Someone might have seen or heard Huia call on this outing. No living Huia pair was obtained by Museum staff, however, during any of the trips. Claims of encountering Huia lingering here and in other hard-to-reach strongholds throughout the North Island continued even past mid-century, several convincing.10

Around the same time that I first heard the bird-man recording, I also encountered ‘Learning a Dead Language’, a poem of five stanzas by poet W. S. Merwin.11 Via the ambiguity it conveyed I felt released from too-simple, clear-cut norms eroding so many hopes of flourishing lives. This poem ushered me into a tangled bank fertile with alternative narratives of trust and desire.

In its first stanza, ‘Learning a Dead Language’ suggests,

There is nothing for you to say. You must

Learn first to listen. Because it is dead

It will not come to you of itself, nor would you

Of yourself master it. You must therefore

Learn to be still when it is imparted,

And, though you may not yet understand, to remember.

At the beginning, I imagine now, Ancestors meeting Unborn. Learning stillness, the listener feels how cold she is somewhere in-between.

What you remember is saved. To understand

The least thing fully you would have to perceive

The whole grammar in all its accidence

And all its system, in the perfect singleness

Of intention it has because it is dead.

You can learn only a part at a time.

What may come of this double-bind in which a listener ‘can learn only a part at a time,’ yet, disconnected from its ‘whole grammar,’ ‘The least thing’ cannot be ‘understood… fully’?’

Perhaps, I sense — as humility postures — understanding, like becoming a forest, is group work.

What you are given to remember

Has been saved before you from death’s dullness by

Remembering. The unique intention

Of a language whose speech has died is order,

Incomplete only where someone has forgotten.

You will find that order helps you to remember.

Who else is remembering? I can hear generations of learners — stolen children — convened and puzzling out their relations as kin. Each listener contributes saved pieces of a torn up composition, filling in gaps for one another. There are voids that remain.

What you remember becomes yourself.

Learning will be to cultivate the awareness

Of that governing order, now pure of the passions

It composed; till, seeking it in itself,

You may find at last the passion that composed it,

Hear it both in its speech and in yourself.

From whispered mutters each learner hears their own voice welcoming and welcomed by each other’s, communication re/emerges, an indisputable chorus.

What you remember saves you. To remember

Is not to rehearse, but to hear what never

Has fallen silent. So your learning is,

From the dead, order, and what sense of yourself

Is memorable, what passion may be heard

When there is nothing for you to say.

At the end, as it was in the beginning, ‘…there is nothing for you to say.’ Yet, the listener is warmer now — while still — in another round of learning, and, another, of deepening cycles of communion with fluent pasts and futures joining into an ever-speechless, but not as lonely, present.

It seemed to me that this poet limned my sense of strengthening, yet obscure loneliness at the same time brightening dimmed expectations for companionship. I was numb with knowledge of the very many kinds of life — and languages — that had recently been rapidly extinguished, as well as the scientific projections of further destruction of life. This numbness bothered me. On the one hand, a lack of feeling made it easier to pretend otherwise. And, on the other hand, such detachment made it easier to weaponize suppressed anger. I wondered whether this difficulty with engagement, which I sensed was widespread, might not be leading otherwise compassionate people not only to abandon hope, but to slander it.12 This possibility scared me. Part of the problem, I guessed, was the abstract nature of ‘extinction’ and of ‘kind’ in contrast with the loss of a particular known face or voice. Another part of the problem was self-preservation — who could really bear such a massive intensity of death? For some of us, awakening to challenge harmful assumptions of our own white supremacy, this intensity would be compounded by our complicity. Another part of the problem, I believed, was my dominating culture’s systemic alienation (also taking forms of forced assimilation) of other humankinds and of other-than-human community members and divisions of past from future and emotion from reason. These forms of violence must certainly translate into mortal wounds in truth-telling. And, without that, how can anybody express love skillfully?

So, these encounters seemed like something to pay attention to — this poem, this dead bird language, parts of which had been remembered by others who ‘saved before you’, in Merwin’s words. Those others, many Māori, themselves had Te Reo, the language of the Tangata Whenua, ‘bashed out of’13 their own or their parents’ mouths in English-only Crown schools. Indeed, at an even higher at-risk proportion than Earth’s birdkinds, most languages of humankinds, a majority of Indigenous ones, are at risk of dying with their few remaining speakers.14 How then, might I properly respond to these saved song remnants as a far-away learning listener? The multiplex voice of the recording, marking absence, haunted my life, becoming, through intimacy, a relied-on presence.15 I kept revisiting the old recording and re-reading this poem. Eventually, I edited out the English-language narration, recognizing that the imprint of Batley’s speech would nonetheless shape Hamana’s whistled phrases. Now, however, I could play this compressed conversation between male and female extinct birds recalled by human ancestors — of colonizer and colonized — disclosed through machines repeating in a loop. And, I would be less distracted by the recall of my own dominating lexicon. I started hearing this edited sound-cycle as ‘Huia Echoes’.

Under the influence also of R. Murray Schafer’s The Soundscape, I then wondered whether other parts of ‘dead’ bird and human and other languages might be imparted if I was ‘still’ while listening to this circling of songs interact within different milieus.16 The strangeness of this thought captivated me. So, I carried Huia Echoes around in my handheld digital device. I also carried a small, inexpensive recorder, which I used to re-store Huia Echoes, but now in replay with various other noises. For example, I sampled Huia Echoes joined with the sounds of a New York City cathedral, of the edge of the Arctic Ocean, of Munich, of Germany and of Changsha, China. An unfolding series of ‘echoEscapes’ — i.e., mixed soundtracks of contemporary spaces fused with the historic Huia Echoes — are aural skeins of intergenerational time as well as of Indigenous and transported, non-Native human and other-than-human languages and voices. These, in turn, can be listened to, repeatedly, in yet other dimensions. It is one of these echoEscapes, composed in Fairbanks, Alaska, that I will be inviting you to share in momentarily.

But, before I do, I want to highlight another aspect vital to this storytelling. Helped along by sources including Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s book Decolonizing Methodologies, learning a dead birdsong urges learners away from a culture of self-taking credit into a mindset of acknowledgement.17 I understand this as an intention not only to remember what is imparted, but, when possible, to answer through whom, with particular attentiveness to holding space for and amplifying those voices who have historically been stifled. Cultivating this consciousness can help in forming reciprocal alliances — new relational networks — characterizing co-creative, re/generative communities, as I continue my decolonization, anti-racist, and other ‘learning to listen’ homeworks.18

In other words, learning to listen also seems to be learning how to participate in healthy community-making, as this continuous project has been from the start. ‘Officially’ there were no restrictions on use of the Huia imitation recording. To be sure, I checked in with and obtained permission from Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library for permission to work with the soundtrack in above ways. Their staff, particularly Matt Young, have been generous in many ways. In 2016, I took the Lab’s field recording course, another help in ear-tuning as well as practice with technologies.

As I continued listening and responsively composing new ‘echoEscapes’, I became uncomfortable about backgrounding the men on the recording. The fact is, I was far distant from their experiences and relationships and the deep legacies contained in this relict. None of it belonged to me. Moreover, the sacredness of this speaking gift demanded honor. What did that mean? I shared these disquiets with another respected colleague, Princess Daazhraii Johnson, who is Neets’aii Gwich’in, where I lived in interior Alaska.19 She asked me questions I need to keep asking: how will I keep my engagement with the recording from becoming another act of colonial appropriation? What of consent? What about not only the birds, but the people involved? Reflecting on these led to other callings. While my interest in extinct birds had led me to the soundtrack, listening now opened my ears to human beings I had never heard. Though both men who took part were also deceased, what responsibilities might my encounters with this historic recording involve to others’ ancestors and to their living kin? What might I learn of and from them, were we to find each other, and, if they were willing to share anything, and how? This oriented me within still-multiplying (un)learning paths.

Thanks to initiatives of my colleagues — Drs. Mike Roche, Susan Abasa, and Margaret Forster, experts in historical geography, museum studies, and Māori knowledge and development, respectively — I received an International Visitor Research funding from Massey University. I was granted a month’s stay in the former Huia range of the North Island. It was straightforward to find Batley’s archives in museums. However, it was difficult to find information concerning Hamana, this itself an expression of settler-colonial legacy. Journalists Kate Evans and Sarah Johnston of Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision kindly introduced me to members of both Batley and Hamana (Salmon) families. I am grateful, sometimes overwhelmingly so, to these families for their generosity in making relations with me in and beyond mutual engagements with the Haman-Huia recording, Huia Echoes.20

Before ever meeting Toby Salmon, a great nephew of Henare Hamana’s, he had understood that my quest was more than academic. It was also deeply personal, in words he offered — ‘a spiritual journey.’ During my 2017 visit, Toby brought me and other whānau (extended family) to the gravesite of the late Huia whistler, where he lay next to his wife, Hari. From the small cemetery on a hill, through a grassy-green fog, we overlooked this pair’s former home, which had recently collapsed. After ceremonial prayers, we went on a tramp into the same bush into which Toby’s uncle had guided in that 1909 search expedition. Under arching canopies of trees and ferns, we listened together.

Finally, before opening into echoEscape.1: ‘The Place Where You Go To Listen,’ I want to share another integral poem, this one brought to my attention by Dr. Lesley Wheeler, a literary scholar in the United States. The words of ‘Huia, 1950s’ by Hinemoana Baker written in 2004, speak to the experience of a dead language learner:21

the huia-trapper

whistles the song

I try to resist

I want to tug

something out of him

the radio voice says

Yes, I also feel this need to ‘tug’, a longing, as I listen to these aural traces. Maybe you will, too.

More questions combine with the others I’ve mentioned. What is it I want to tug out and why try to resist? Might this impulse have something to do with the shapeless loneliness I mentioned above? With anguished hope? With how to love skillfully?

At the same time, what does the complex voice want to tug out of me — that perhaps I should give in to?

Fig. 3.3 ‘The Place’, Museum of the North, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska. Photograph by Julianne Lutz Warren (2015).

Backgrounder for ‘echoEscape.1’

Sonic sphere: Naalagiagvik (Inupiaq) ‘The Place Where You Go to Listen’, a 2006 sound installation by composer John Luther Adams22

Location: Unceded Traditional Territories of the lower Tanana Dene Peoples in the Museum of the North, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska

Geographical Coordinates: Latitude: 64-50’06’’ N; Longitude: 147-39’11’’ W

Elevation: 446 feet

Listening date/time: 13 August 2015/9:30am–10:30am

Approximate Nautical Miles from Manawatu Gorge, North Island, Aotearoa, New Zealand, Traditional Region of Rangitāne: 6500

I acknowledge and honor the ancestral and present land stewardship and place-based knowledge of the Indigenous Peoples of Alaska and Aotearoa New Zealand, geographies featured in this echoEscape.

echoEscape.1: ‘The Place Where You Go to Listen’23

The Approach

I welcome you into echoEscape.1. Please, will you come along into this listening event to practice learning a dead birdsong with me?

This August day, the clouds are heavy and low — swells of grey down.

The sky has just rained, darkening the pavement. Water is dripping from green boughs of spruce and birch branches. An easy wind smells like wet grass.

Downhill, in a nearby grain-field turned gold, Sandhill Cranes are chiming — ‘deldal’ in Benhti Kanaga, a local Dene language, ‘a crane is calling’24 — in the few days left before migration.

The moon will be new tomorrow. The tiniest sliver of today’s waning crescent, though invisible, arcs slowly above the horizon.

The morning sun’s light, filtered through the blanket overhead, is muted. A listener might want to wear a sweater.

Once inside the museum, a listener hears kids’ laughter ringing off slick floors and glass doors. Heels click past the gift shop, then climb a staircase to the second floor with a bay of windows on the right. To the left, there is a gallery with an alcove.

A sign on a door in the alcove says, ‘enter quietly’.

A listener may want to pause before doing so. Turn around to look, again, through the wide span of glass. Generations of Dene have come to Troth Yeddha’, or, ‘the ridge of the wild potatoes’, to harvest these legumes. With such a sweeping vantage, this hill has long been an attractive meeting site. Outside, beyond today’s rain veil, are mountains far older even than this Land’s First Peoples. The immensity of that rock, though over a hundred-miles distant, feels demanding. On a clear day, the ‘Three Sisters’ are eye-magnets — their snowy tops gleam gold-pink. And, more to the right, to the southwest, would be Denali — the tallest North American peak.

Unless, perhaps, this summit has fallen during the night. It can’t be known for sure, unless the clouds withdraw, whether or not the mountain remains standing at all, can it?

An introductory plaque on the alcove door describes ‘The Place Where You Go to Listen’. It tells how an Iñupiaq legend was in the memory of a composer, John Luther Adams, who imagined and, with the help of others, built this sound art installation. A woman, so the legend says, sat quietly in a place called ‘Naalagiagvik’ on Alaska’s Arctic Coast. In that place, she — her name has not been given — heard things.

In contrast to the open Arctic plain spreading into a vast, salt-smelling sea, the room a listener is about to enter is a close space — about ten by twenty feet, with no windows. There is one long wooden bench in the center. Floors, ceiling and walls are white, except for one wall that glows with the only source of light. This light slowly, barely perceptibly, changes color — in summer, of yellows and green-blues — seasonal, circadian hues tune with the unceasing flow of noise vibrating from a surround of speakers. The noise in the speakers emanates from machines that translate sources of real time physical conditions outside into sounds — filtered, tuned and tempered — merged into a continuous electronic stream. This resonating stream, fluid with emergent tones and rhythms, is a polyphony of irregular seismic groans at foot-shuddering level, at ear-height, the reliable voice of moon — from the perspective of Earth’s horizon — waxing and waning, rising and setting with the chorusing sun sung through sound-damping prisms of palls and mists of air. From ceiling speakers, when aurora are active, fluxing bells tinkle down voicing them.

Before Entering

Be warned: Upon first opening the door, a listener sometimes feels repelled by the room’s chaotic acoustic atmosphere, even afraid. In past visits, I have hesitated on this threshold, my heart pounding. From inside I have watched many would-be listeners crack open the door, then, retreat. But, please, won’t you enter, with me, together?

One of the most important things about this place is that a listener may go. Anyone who enters this room can exit the same way.

But, why not stay for awhile, perhaps, learning ‘to be still?’ Although neither you nor I may yet understand what we carry inside — Huia Echoes — is a performance of remembering.

Crossing the Threshold, Entering

This place, says Adams, ‘is not complete until you are present and listening’.

First, a listener must resist leaving. Second, a listener will do well not to resist giving in before, at some point, departing.

A listener clicks the open the door. On one side of the threshold, reverberating footsteps, adult talk and pealing laughter. On the other side, the continually streaming noise of The Place.

The door clicks shut behind us. Now, hear only the noise, streaming

into a listener’s gut, the rocking Earth rumbles. Shhhhh — recall, the new moon, present, yet silent. Tone-rays of sun lap a listener’s cheeks. When clouds thin outside, an aural prism releases daylight’s chorus. Billows thickening sounds a shaded indoor quiet. Tides of tinkling auroral bells wash in and out over a listener’s head.

Ears, set loose, float away, drifting birds in unceasing, ever-changing currents of sound.

If this is a dream of voices dreaming. Who is the dreamer? The whole Earth? The human composer? A present listener? Past and future ears? Some other source? Is it possible for all to dream the same dream, and differences?

A listener doesn’t know.

A Māori chant shared in the nineteenth century by Te Kohuora of Rongoroa, speaks, Na te — that is, from the — primary source, rising-thought-memory-mind/heart-desire…25

when the mind/heart remembers the source and desires what emerges, isn’t that supreme hope? Who can solve hope?

Te Kohuora’s chant continues, Te kore te rawea — or, say, unbound nothingness — stirring hau — breath of life and growth — moving through darkness, the world, the sky, moon, sun, light — day! — earth (female) — and — sky (male) — and ocean, the children of earth and sky, food plants, forests, lakes and rivers, ancestors of fish, lizards, birds…life and death and life…

In Te Reo Māori, change happens across the pae — liminal spaces of potential emergence — between life and death, light and dark, silence and noise, absence and presence, inhabitants and visitors, one kind of being and another.26

In The Place, in this room, imagine many pae — the sound is never-ending and never the same, unfolding in time. There are low tones and high, consonances and dissonances begin and end, the inaudible outside is audible inside mingled with dim ambience and subtly changing colored light. The door that opened will close. The listener who entered — inhales exhales will eventually leave.

Replaying Huia Echoes27

Now a listener presses a button on a play-back machine releasing the legacy of interrelations voiced by Huia Echoes, foreign to this place, into the many other exchanges already happening: Two men — now both dead — the colonized one sharing a taonga — a treasured thing — with the colonizer, a colonizer, working to de-colonize, passing it on, asking — who am I? Who are you? Listening. The taonga is the imitation of two birds reciprocating want, dead voices sound animate. What is breathless, and unchanging, sings, full of breath, if not changing, bringing changes (or, were the multiple voices always ever asleep, now waking?)

The room’s noise never stops. It courses in eddies and flushes downstream.

While, Huia Echoes tracks a round channel.

As the noise of this inside world is ever-changing as is the outside one, Huia Echoes is a recording with a chorus of voices on repeat — beginning-middle-end — the same, over and over again.

Or are they?

What happens across the pae between this room of noise and the machine-saved echoes of lost man-and-bird?

Huia Echoes sounds mingled and disruptive, tender and insistent. Echoes echo. Their voices are buoyed by waves sink, and soar. The bird-man chorus varies with the outside weather heard inside the world of The Place. While, auroral bells curtain the recording’s higher pitches, making them hard to distinguish. When the clouds disperse, beyond the walls, the octaves of the sun’s choir widen and brighten. The sun brightening, paradoxically, shades Huia Echoes’ tones. The clouds, darkening, unexpectedly, expose the re-playing voices. Aurora, quieted, release the higher notes of extinct bird-man songs. Catching a sonic wave — and, sometimes don’t you hear your own speech — voices, caught, sway up and down — male and female oscillate:

Here I am.

Here I am.

Over here.

Here am I.

Who are you? Who I am? Am I you? You, me? Are we ‘we’?

In the stream of sounds, the calls of Huia Echoes alter. Or, is it Huia Echoes — as leaves do the wind — re-directing the room’s flow of sounds? Are the ears of a listener transformed? Who is the changer, and, who being changed, in this dream of dreamers dreaming? Who or what has will? What is trust? What desire?

Huia Echoes Stopped

After listening awhile, a listener turns off the machine replaying the bird-man recording. Feel the relief in the silence of their cluttering tones within this room full already overflowing with sounds. Is that relief a germ of forgetting?

Yet, having grown familiar with the added presence of Huia Echoes, the room now also sounds wrong. Feel the absence of the composite voice — with a pang — as a plangent void. Is that pang a seed of remembering?

But, what if Huia Echoes, rather than remain a captive of the machine, found a sonic wormhole and escaped?

Though the recording is off, catch those phrases of the bird-man voice repeating

— a ghost of tones —

Is that audible phantom, my desire or Echoes’?

A Listener Plays

Still captivated by the ever-rolling sounds of the room, a listener stays on, hearing, but not still, puzzling, a contribution.

A listener’s voice turns on. Wells up, though it does not want to shout nor need to cry out, but, somehow, at the same time to dissolve yet stand out.

A childhood’s nursery rhymes labor as breath is tugged out of a listener’s mouth while another listener can bear other words by their tongues who play wordplay words Three blind mice repeats, mantra-like syllables hamper and scamper, unpredictably see how

they run?

How much wood can a woodchuck chuck? much wood could the woodchuck chuck an adverb leaps into the drink.

PeterPiperpickedapeckofpickledpeppers tumbles out next and cannot outrun time not even backward pepperspickledofpeckpickedPeterPiper as voiceless plosives resist flowing

Humpty Dumpty’s manifest consonants spill out — and all the king’s men couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty together again as miscarried skipping stones,

plunking into this ocean of sound Whereas,

Mary had a little lamb catches a current resonates and clashes randomly in the swirls until the lamb was sure to goOOOOOOooooooo blends with sun’s hum tuned in a human listener’s capacity to a fundamental frequency of the daily spin of Earth — twenty-four point two seven hertz is a tempered G – eoooooooo the tiny vowel – ooooooooo pools into a quiet layer of sound an octave between the organ of solar light and shimmering auroral bells harmonizing with the whole planet

A listener becomes a self-conscious composer

A coda happens

three blind mice three blind mice three blind mice see how they run? bends the old rhyme into a question

hum goOOOOOOooooooo…… Wait…

Run, where? Blinded, how? Why see? Why listen? Why sing?

Crossing the Threshold, Exiting

A listener gets ready to leave ‘The Place’, where it has been safe both to give in and to resist, be distinct. One of the most important things about this room is that the listener may find a way out.

A listener clicks open the door. On one side, the continually streaming noise of The Place. On the other side, reverberating footsteps, reverberating talk and peals of laughter.

The door clicks shut behind a listener. Heels click along the shiny tile floor, past the bay of windows, to the left. A listener pauses, again, to look out.

The moon is still new, invisible as the sun — audibly chorusing back inside — still hidden behind silver billows, as are the distant mountains. A listener has kept faith in them.

A listener’s footsteps now ring down the stairs, past the gift shop, through the glass doors.

Outside

A listener does not hear deldal once back outside — that is, the cranes are no longer chiming. Beyond the still-billowing clouds, a fingering menace is closing around Earth. The menace twists Earthlings into an undying sameness, a dry, pae-less monotone that repeats, ‘believed to be extinct.’

But, still, listen — there is a courage of breath that can say yes! and also no! And, I don’t know! And, in between, spaces of potential emergence from which many voices might echo. A dead birdsong learner, too, may join in, also unlearning what has never been good.

And, what if Huia Echoes did pass through a wormhole back there in the chaos of sounds? What if they did refuse the machine, and anyone’s will to turn them off or on?

In the lingering ear-tuning of The Place, it’s not only that a listener hears music in the whir of a fan, or mistakes a distant chainsaw cutting firewood as Dene languages more-than-surviving, there also is something going on with the birds.

The Birds

It is early spring, Huia Echoes wakes me from sleep. They are singing in the forest beyond an open window. I leap out of bed fumble, bleary-eyed, lean out, ears tune in and hear

those Swainson’s thrushes

as I suddenly recognize them.28

They had picked up the lost bird-man voice.

What if these boreal flesh-and-feather throats echoing the echoes of extinct birds from a world away?

A listener cherishes that dream all the more as a/wake a persistent, ringing void keeping shalak naii (all our relations)29

in the world-alive

in play.30

Bibliography

Abram, David, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology (New York, NY: Vintage, 2011).

Adams, John Luther, The Place Where You Go to Listen: In Search of an Ecology of Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2009).

Anderson, Atholl, ‘A Fragile Plenty: Pre-European Māori and the New Zealand Environment’, in Environmental Histories of New Zealand, ed. by Eric Pawson and Tom Brooking (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 35–51.

Baker, Hinemoana, ‘Huia, 1950s’, in Matuhi/Needle, Hinemoana Baker (Wellington: Perceval Press/Victoria University Press, 2004), p. 38.

Batley, R. A. L. Archives, Box 2011.117.1 MS 177, Whanganui Regional Museum, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/16209

Buller, Walter L., A History of the Birds of New Zealand, Vol 1 (London: self-published, 1888).

Cain, Trudie, Ella Kahu, and Richard Shaw, eds, Turangawaewae: Identity and Belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand (Auckland: Massey University Press, 2017).

Campbell, E. E., Central District Times, Letter to the Editor, 3 December 1974 in RAL Batley, Archives Box 16, 2011.117.1, Whanganui Museum, NZ.

Cardiff, Janet, and George Bures Miller, ‘The Murder of Crows’, Armory, 2012, http://www.armoryonpark.org/programs_events/detail/janet_cardiff_george_miller_murder_of_crows

Forster, Margaret E., ‘Recognising Indigenous Environmental Interests: Lessons form Aotearoa New Zealand,’ Presented at International Political Science Association, Research Committee 14: Politics and Ethnicity. The Politics of Indigenous Identity: National and International Perspectives. Dunmore Lang College, Macquarie University, Sydney (July, 2013).

Jensen, Derrick, ‘Beyond Hope’, Orion Magazine, 2 May 2006, https://orionmagazine.org/article/beyond-hope

Kirkegaard, Jacob, ‘Aion’, MOMA, 2013, https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2013/soundings/artists/6/works

Knight, Catherine, Ravaged Beauty: An Environmental History of the Manawatu (Ashhhurst: Totara Press, 2014).

Licht, Alan, ‘Sound Art: Origins, Development and Ambiguities’, Organised Sound, 14.1 (2009), 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355771809000028

Merwin, W. S., ‘Learning a Dead Language’, in Migration: New and Selected Poems, W. S. Merwin (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2005), p. 41.

Norman, Geoff, Bird Stories: A History of the Birds of New Zealand (Nelson: Potton and Burton, 2018).

Orbell, Margaret, The Natural World of the Māori (Auckland: Collins, 1985).

Phillips, W. J., The Book of the Huia (Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd, 1963).

— ‘Huia Research: 1927–1954, (MU000235)’, Dominion Museum (creating agency) (Wellington: Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa, [n.d.]).

Rika, Maisey, ‘Reconnect’, in Maisey Rika (Auckland: Moonlight Sounds, 2009).

Riley, Murdoch, Māori Bird Lore (Paraparaumu, NZ: Viking Sevenseas, NZ Ltd, 2001).

Salmond, Anne, Tears of Rangi: Experiments across Worlds (Auckland: University of Auckland Press, 2017).

Schafer, R. Murray, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Destiny Books, 1993).

Selby, Rachel, Malcolm Mulholland, and Pataka Moore, eds, Maori and the Environment (Wellington: Huia Publishers, 2010);

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai, Decolonizing Methodologies (London: Zed Books, 2012).

Szabo, Michael, ‘Huia, The Sacred Bird’, New Zealand Geographic, 20, October-December (1993), https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/huia-the-sacred-bird

Lower Tanana Athabaskan Dictionary, compiled and edited by James Kari, Alaska Native Language Center, First Preliminary Draft, 1994, https://uafanlc.alaska.edu/Online/TNMN981K1994b/kari-1994-lower_tanana_dictionaryf.2.pdf

Tennyson, Alan, and Paul Martinson, Extinct Birds of New Zealand (Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2007).

Trummer, Thomas, ed., Voice and Void (Ridgefield, CT: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2007).

Warren, Julianne, ‘Hopes Echo’, The Poetry Lab, The Merwin Conservancy, 2 November 2015, https://merwinconservancy.org/2015/11/the-poetry-lab-hopes-echo-by-author-julianne-warren-center-for-humans-and-nature

Warren, Julianne, and Daazhraii Johnson, ‘To Hope to Become Ancestors’, in What Kind of Ancestor Do You Want to Be?, ed. by John Hausdoerffer, Brooke Hecht, Kate Cummings, and Melissa Nelson (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, in press).

Whatahoro, H. T., The Lore of the Whare-Wānaga: Or Teachings of the Māori College on Religion, Cosmogony, and History Vol. 1: Te Kauwae-Runga, or ‘Things Celestial’, trans. by S. Percy Smith (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139109277

1 R. A. L. Batley, Archives, Box 2011.117.1 MS 177, Whanganui Regional Museum. The original recording can be heard here: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/16209

2 Michael Szabo, ‘Huia, The Sacred Bird’, New Zealand Geographic, 20 October-December 1993, https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/huia-the-sacred-bird

3 The Māori-language term for a white person, typically of European descent.

4 For discussions of extinctions in the wake of both Māori and Pākehā arrival, see, for example: Alan Tennyson and Paul Martinson, Extinct Birds of New Zealand (Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2007) and Atholl Anderson, ‘A Fragile Plenty: Pre-European Māori and the New Zealand Environment’, in Environmental Histories of New Zealand , ed. by Eric Pawson and Tom Brooking (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 35–51; see also Catherine Knight, Ravaged Beauty: An Environmental History of the Manawatu (Ashhhurst: Totara Press, 2014).

5 In te reo Māori — English translations of ‘whenua’ include, land, country, ground, and placenta. Margaret E. Forster, ‘Recognising Indigenous Environmental Interests: Lessons form Aotearoa New Zealand,’ Presented at International Political Science Association, Research Committee 14: Politics and Ethnicity. The Politics of Indigenous Identity: National and International Perspectives. Dunmore Lang College, Macquarie University, Sydney (July, 2013). Rachel Selby, Malcolm Mulholland, and Pataka Moore, eds, Maori and the Environment (Wellington: Huia Publishers, 2010); Trudie Cain, Ella Kahu, and Richard Shaw, eds, Turangawaewae: Identity and Belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand (Auckland: Massey University Press, 2017).

6 English translations of ‘tapu’ include ‘set apart’ or ‘under restriction’.

7 Szabo, ‘Huia, The Sacred Bird.’

8 For discussion of huia-human interrelations, see: W. J. Phillips, The Book of the Huia (Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd, 1963); W. J. Phillips, ‘Huia Research: 1927–1954, (MU000235)’, Dominion Museum (creating agency) (Wellington: Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa, [n.d.]); H. T. Whatahoro, The Lore of the Whare-Wānaga: Or Teachings of the Māori College on Religion, Cosmogony, and History Vol. 1: Te Kauwae-Runga, or ‘Things Celestial’, trans. by S. Percy Smith (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139109277; Margaret Orbell, The Natural World of the Māori (Auckland: Collins, 1985); Murdoch Riley, Māori Bird Lore (Paraparaumu, NZ: Viking Sevenseas, NZ Ltd, 2001); Walter L. Buller, A History of the Birds of New Zealand, Vol. 1 (London: self-published, 1888), pp. 9–17; Geoff Norman, Bird Stories: A History of the Birds of New Zealand (Nelson: Potton and Burton, 2018).

9 Under the Crown government most of this forested area was in blocks collectively-owned by Māori, in particular, by members of Hamana’s Iwi.

10 Phillips, The Book of the Huia and ‘Huia Research’; Dean Andrew Baigent-Mercer, ‘Brief of Evidence,’ In the Waitangi Tribunal Wai 1040 Te Paparahi o Te Raki Inquiry District Wai 1661, 31 October 2016, 25.

11 W. S. Merwin, ‘Learning a Dead Language’, in Migration: New and Selected Poems (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2005), p. 41. See also, Julianne Warren, ‘Hopes Echo’, The Poetry Lab, The Merwin Conservancy, 2 November 2015, https://merwinconservancy.org/2015/11/the-poetry-lab-hopes-echo-by-author-julianne-warren-center-for-humans-and-nature

12 For example, Derrick Jensen deems hope a ‘bane’ in ‘Beyond Hope’, Orion Magazine, 2 May 2006, https://orionmagazine.org/article/beyond-hope

13 E. E. Campbell, Central District Times, Letter to the Editor, 3 December 1974 in RAL Batley, Archives Box 16, 2011.117.1, Whanganui Museum, NZ.

14 According to BirdLife International, 40% of Earth’s birds are in decline. See: https://e360.yale.edu/digest/forty-percent-of-the-worlds-bird-populations-are-in-decline-new-study-finds and UNESCO predicts, in current circumstances, that 50%–90% of Indigenous languages (approximately 3000) will be replaced by English, Madarin or Spanish by 2100. See https://www.iwgia.org/en/focus/international-year-of-indigenous-languages.html

15 Alan Licht, ‘Sound Art: Origins, Development and Ambiguities’, Organised Sound, 14.1 (2009), 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355771809000028. I use the word ‘companion’ in the same sense as Licht (7). Also, I acknowledge the influence of David Abram, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology (New York, NY: Vintage, 2011), whose work has informed my understanding of relationality.

16 R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Destiny Books, 1993). See also Voice and Void, ed. by Thomas Trummer (Ridgefield, CT: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2007); Jacob Kirkegaard, ‘Aion’, MOMA, 2013, https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2013/soundings/artists/6/works; and Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, ‘The Murder of Crows’, Armory, 2012, http://www.armoryonpark.org/programs_events/detail/janet_cardiff_george_miller_murder_of_crows

17 Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies (London: Zed Books, 2012). All remaining mistakes and lacks in my own understanding remain my own responsibility.

18 For example, see Marilyn Strathern, Jade S. Sasser, Adele Clarke, Ruha Benjamin, Kim Tallbear, Michelle Murphy, Donna Haraway, Yu-Ling Huang, and Chia-Ling Wu, ‘Forum on Making Kin Not Population: Reconceiving Generations,’ Feminist Studies, 45.1 (2019), 159–72. I deeply thank Native Movement, the Gwich’in Steering Committee, and Fairbanks Climate Action Coalition for arrays of workshops, camps, and trainings. Throughout, I am thinking of this definition of ‘decolonization’: ‘The conscious — intelligent, calculated, and active — unlearning and resistance to the forces of colonization that perpetuate the subjugation and exploitation of our minds, bodies, and lands. And it is engaged for the ultimate purpose of overturning the colonial structure and realizing Indigenous liberation.’ — Native Movement Training Slide, Summer 2018, https://fairbanksclimateaction.org/events/2018/3/24/decolonize-your-mind-untangle-history-building-liberation

19 Together, we have a co-authored a forthcoming chapter entitled ‘To Hope to Become Ancestors’, in What Kind of Ancestor Do You Want to Be?, ed. by John Hausdoerffer, Brooke Hecht, Kate Cummings, and Melissa Nelson (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, in press).

20 The Salmon family invited me to return for another visit in February 2020, after this piece went to press. Ngā mihi to Jane and Toby Salmon and Karen and Dave Salmon, on repeat!, for their incredibly generous hosting as we share in such an amazing journey together. It was an all-too brief stay on my part. And, so much remains unsaid here or now that could be said better.

21 Hinemoana Baker, ‘Huia, 1950s’, in Matuhi/Needle (Wellington: Perceval Press/Victoria University Press, 2004), p. 38. I especially thank John Luther Adams, not only for his profound work, but also, as partners — him and Cindy Adams — for good conversations when their lives and those of mine and my partner’s have intersected.

22 John Luther Adams, The Place Where You Go to Listen: In Search of an Ecology of Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2009). The title of the work is a literal translation of the Inupiaq place name ‘Naalagiagvik’. Listening samples are available here: https://www.uaf.edu/museum/exhibits/galleries/the-place-where-you-go-to/

23 In various interactions, this essay also has taken forms as a sound art piece with great thanks to Mickey Houlihan (curveblue.com) for audio editing and mixing and to Joe Shepard for audio restoration and editing..

24 The final ‘l’ is a voiceless fricative. Lower Tanana Athabaskan Dictionary, compiled and edited by James Kari, Alaska Native Language Center, First Preliminary Draft, 1994, https://uafanlc.alaska.edu/Online/TNMN981K1994b/kari-1994-lower_tanana_dictionaryf.2.pdf

25 From ‘creation chant’ quoted in Anne Salmond, Tears of Rangi: Experiments across Worlds (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2017), pp. 11, 14.

26 Pae (threshold, middle ground) in Salmond, Tears of Rangi, p. 3.

27 The looped recording can be heard here: https://merwinconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/HuiaEchoesLoopCornellTrack_1.wav (part of my earlier essay https://merwinconservancy.org/2015/11/the-poetry-lab-hopes-echo-by-author-julianne-warren-center-for-humans-and-nature/).

28 A recording of Swainson’s Thurshes can be heard here: https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=swathr&mediaType=a&q=Swainson%27s%20Thrush%20-%20Catharus%20ustulatus

29 In Gwich’in, another Arctic Athabascan language.

30 This song offers a beautiful tribute to Huia and relations: Maisey Rika, ‘Reconnect,’ on Maisey Rika (Moonlight Sounds, 2009). Kia ora (Special thanks), Toby and Jane Salmon — ‘Ko matou nga Kaitiaki mo apopo.’