1. Introduction

© Ignasi Ribó, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0187.01

In one form or another, stories are part of everyone’s lives. We are constantly telling each other stories, usually about events that happen to us or to people we know. These are usually not invented stories, but they are stories nonetheless. And we would not be able to make sense of our world and our lives without them.

We also enjoy reading, watching, or listening to stories that we know are not true, but whose characters, places, and events spark our imagination and allow us to experience different worlds as if they were our own. These are the kind of stories we call ‘fiction.’ Many people like to watch series or soap operas on TV. And even more people like to watch movies, whether in the cinema or streamed to their laptop or smartphone. Video games, comics and manga, songs and musicals, stage plays, and YouTube blogs, they all tell stories in their own ways. But if there is one medium that has shown itself particularly well-suited to tell engaging and lasting stories throughout the ages, it is written language. It is fair to say, then, that stories, and most particularly fictions, in their various forms and genres, constitute the backbone of literature.

In this chapter, we will introduce some basic ideas about storytelling, and in particular about the narrative forms of literature and the ways in which they create meaning. We will also present the main genres into which literary narratives have been divided historically, and how these genres have evolved from their origins until today. We will then try to define and frame the two genres of prose fiction that are more common nowadays and from which we will draw the examples in this textbook: short stories and novels.

Not everyone approaches these genres in the same way. Here, we will follow a semiotic model to study and interpret narrative structure and meaning. In order to understand this model, it is essential to grasp the distinction between story and discourse, which will guide our discussions throughout the book. To conclude this chapter, we will consider how short stories and novels spread beyond the written word and become interconnected with other media in contemporary culture.

1.1 What Is Narrative?

Narrative is notoriously difficult to define with precision. But even before we attempt a working definition of the concept, we already know that it refers to storytelling. The term itself comes from the Latin word narro, which means ‘to tell.’ In English, to narrate means to tell a story. According to many anthropologists, this ability is universal amongst human beings.1 All peoples, everywhere and throughout history, tell each other stories, or, as they are technically called, narratives. As the semiotician and literary critic Roland Barthes once wrote,

The narratives of the world are numberless. Narrative is first and foremost a prodigious variety of genres, themselves distributed amongst different substances — as though any material were fit to receive man’s stories. Able to be carried by articulated language, spoken or written, fixed or moving images, gestures, and the ordered mixture of all these substances; narrative is present in myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama, comedy, mime, painting, stained-glass windows, cinema, comics, news items, conversation. Moreover, under this almost infinite diversity of forms, narrative is present in every age, in every place, in every society; it begins with the very history of mankind and there has never been a people without narrative. All classes, all human groups, have their narratives, enjoyment of which is very often shared by men with different, even opposing, cultural backgrounds. Caring nothing for the division between good and bad literature, narrative is international, transhistorical, transcultural: it is simply there, like life itself.2

For the purpose of this book, we will define narrative as the semiotic representation of a sequence of events, meaningfully connected by time and cause.3 This definition highlights certain key elements shared by all forms of narrative:

- Narratives are semiotic representations, that is, they are made of material signs (written or spoken words, moving or still images, etc.) which convey or stand for meanings that need to be decoded or interpreted by the receiver.

- Narratives present a sequence of events, that is, they connect at least two events (actions, happenings, incidents, etc.) in a common structure or organised whole.

- Narratives connect events by time and cause, that is, they organise the sequence of events based on their relationship in time (‘Hear the sweet cuckoo. Through the big-bamboo thicket, the full moon filters.’4), as cause and effect (‘Into the old pond, a frog suddenly plunges. The sound of water.’5), or, in most narratives, by both temporal and causal relationships.

- Narratives are meaningful, that is, they have meaning for both senders and receivers, although these meanings do not need to be the same.

As this definition suggests, narrative is the fundamental way in which we humans make sense of our existence. Without effort, we connect everything that happens in our lifeworld (events) as a temporal or causal sequence, and most often as both. In order to understand our lives and the world around us, we need to tell ourselves and each other meaningful stories. Even our perception of things that appear to be static inevitably involves making up stories.6 Are you able to look at the picture in Figure 1.1 below without seeing a connected sequence of events, a narrative, in it?

Fig. 1.1 Collision of Costa Concordia, cropped (2012). By Roberto Vongher, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Collision_of_Costa_Concordia_5_crop.jpg

1.2 Genres

Genres are conventional groupings of texts (or other semiotic representations) based on certain shared features. These groupings, which have been used since ancient times by writers, readers, and critics, serve a variety of functions:

- Classification: By identifying the features that are worthy of attention, genres help us to place a particular text among similar texts and distinguish it from most other texts.

- Prescription: Genres institute standards and rules that guide writers in their work. Sometimes these rules are actively enforced (normative genres), while at other times they act simply as established customs.

- Interpretation: These same standards and rules help readers to interpret texts, by providing them with shared conventions and expectations about the different texts they might encounter.

- Evaluation: Critics also use these standards and rules when they set about judging the artistic quality of a text, by comparing it with other texts in the same genre.

Already in Ancient Greece and Rome, narrative was a major literary genre (epic), distinct from poetic song (lyric) and stage performance (drama). Other generic classifications, particularly those related to the content of the story (tragedy, comedy, pastoral, satire, etc.), were also commonly used. But the basic classification of poetic forms at the time, established by Plato and Aristotle, was based on whether the poet told the story (diegesis) or the story was represented or imitated by actors (mimesis).

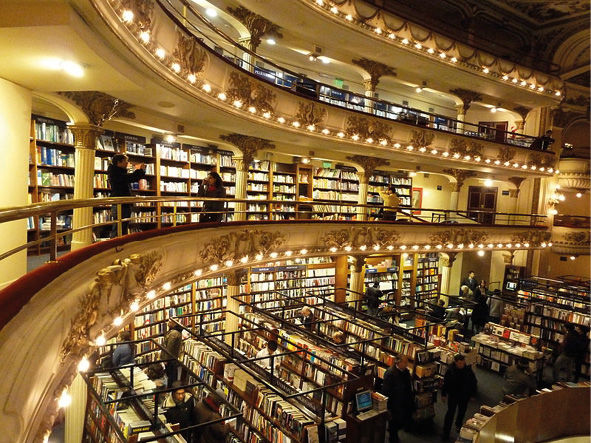

While Classical and Neoclassical poetics thought of genres as fixed and preordained forms that poets needed to abide by, modern literary theory, starting with the Romantic period, has come to see genres as dynamic and loosely defined conventions. Genres change and evolve through time. Different cultures define and institute different genres. In fact, modern literature has seen a significant expansion of genres, as a visit to any bookstore or online bookseller will attest (see Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2 El Ateneo Gran Splendid. A theatre converted into a bookshop. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Photo by Galio, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Buenos_Aires_-_Recoleta_-_El_Ateneo_ex_Grand_Splendid_2.JPG

Genres are continuously evolving across many different dimensions, such as content, style, form, etc. They are often organised at different levels of subordination, in hierarchies or taxonomies of genres and subgenres. Nowadays, for example, the following generic distinctions are commonly used to classify stories:

- Fiction vs. nonfiction (based on whether the events and the characters of the story are invented or taken from reality).

- Prose vs. verse (based on the literary technique used to tell the story).

- Narrative vs. drama (based on whether the story is told or shown).

- Novel, novella, or short story (based on the length of the story).

- Adventure, fantasy, romance, humour, science-fiction, crime, etc. (based on the content of the story).

These and many other generic classifications allow us to impose some order on the vast number of stories that are published every year. But they are not set in stone and are certainly not eternal. Following the disposition of writers, readers, and critics, new genres appear and disappear, often combining the characteristics of previous texts or developing from the ambiguous boundaries of existing genres, as with the blending of ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ into ‘faction’ (or nonfiction novel).7 There is little doubt that novels and short stories are the most popular narrative fiction genres in contemporary literature. Like all genres, however, they appeared at some point in history and will only last as long as people are interested in writing and reading them.

1.3 Prose Fiction

Prose is text written or spoken with the pattern of ordinary or everyday language, without a metrical structure. Verse, on the other hand, is written or spoken with an arranged metrical rhythm, and often a rhyme. While narrative fiction composed in verse was very common in the past, modern writers overwhelmingly tell their stories in prose, to the point that most readers today would be baffled if they encountered fiction written in verse.

By far, the most popular genres of prose fiction nowadays are novels and short stories. The distinction between the two is fairly simple and straightforward: short stories are short, novels are long. Any other difference that we might be able to find between these two genres of narrative is derived in one way or another from this simple fact.

But before identifying certain key differences, it is important to understand that both short stories and novels are modern narrative genres, which only emerged in their current forms during the European Renaissance.8 Of course, people had been telling each other fictional stories in other forms since much earlier and in many other places. Perhaps the two forms that had the strongest influence on the emergence of these modern genres of prose fiction were the Classical epic poems, most particularly Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and the Hebrew Bible, which is filled with a wide variety of short stories.

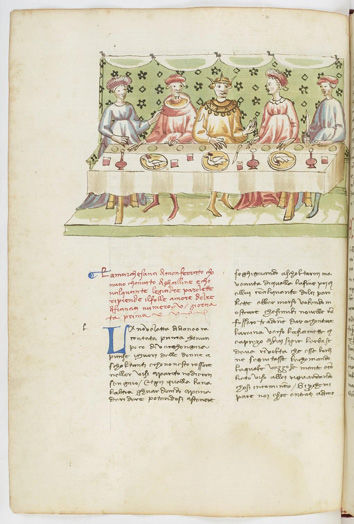

During the European Renaissance, these and other influences stimulated many writers to produce fictional narratives in prose using vernacular languages (instead of Latin), so that they could reach a growing audience of readers. These narratives were not intended to be read aloud, like epic poems or other forms of poetry and drama, but silently, as part of an intimate experience between the reader and the text.9 Initially, these new narratives, inspired in Middle Eastern and Indian storytelling, tended to be short and were often published as a collection, like Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353, Fig. 1.3). Contemporaries referred to them as novelle (singular, novella), which means ‘new’ in Italian and is a term still in use today to refer to short novels. From the perspective of Western culture, these early novelle are the first modern forms of prose fiction.

Fig. 1.3 Boccaccio, Decameron: ‘The Story of the Marchioness of Montferrat,’ 15th century. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Decameron_BNF_MS_Italien_63_f_22v.jpeg

A little later in the Renaissance, some authors began to extend these novelle into longer stories that occupied the whole book with the adventures of a single protagonist. In this way, what we now call the novel was born. The first modern novel, according to most, is Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605, Fig. 1.4), the tragicomic story of a deluded country squire who tries to revive the heroic lifestyle depicted in fictional books of chivalry. We should not forget, however, that long narratives, similar in many ways to modern novels, had already been written and read in different cultures throughout history. For example, Lucius Apuleius’ The Golden Ass (ca. 170), Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe (2nd century), Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji (1010), Ramon Llull’s Blanquerna (1283), or Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms (ca. 1321), amongst many others.

Fig. 1.4. Title page of the first edition of Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605). Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Quixote#/media/File:El_ingenioso_hidalgo_don_Quijote_de_la_Mancha.jpg

Due to their difference in length, short stories and novels also tend to differ from each other in certain respects:

- Short stories need to focus on a few characters, a limited number of environments, and just one sequence of events. They cannot afford to digress or add unnecessary complications to the plot. Density, concentration, and precision are essential elements of good short-story writing.

- Novels, on the other hand, can explore many different characters, environments, and events. The story can be enriched with subplots and complications that add perspective, dynamism, and interest to the novel. Characters have room to evolve and the author can introduce digressions and commentary without undermining the form. Scope, breadth, and sweep are essential elements of good novel writing.

This does not mean that the novel is better or worse than the short story. They are simply different forms of narrative, both well adapted to achieve their own purposes. While the novel can recreate a fictional world in all its complexity and vastness, the short story is able to shine a sharper light on a particular character or situation.

1.4 Story and Discourse

The systematic study of narratives in order to understand their structure (how they work) and function (what they are for) is called narratology.10 This field has developed a set of conceptual tools that allow us to discern with more clarity and precision the process through which narratives are meaningful for writers and readers. Narratology is closely linked with semiotics, the study of meaning-making processes, and in particular the use of signs and signifying systems to communicate meanings. In this sense, it is important to realise that narratological models are not so much concerned with explaining individual narratives, but rather they attempt to identify the underlying semiotic system that makes narrative production and reception possible.11

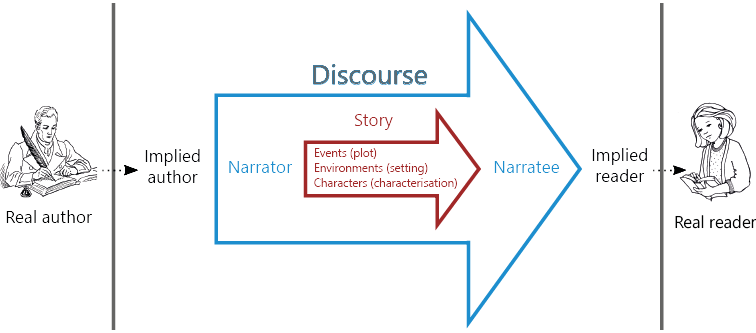

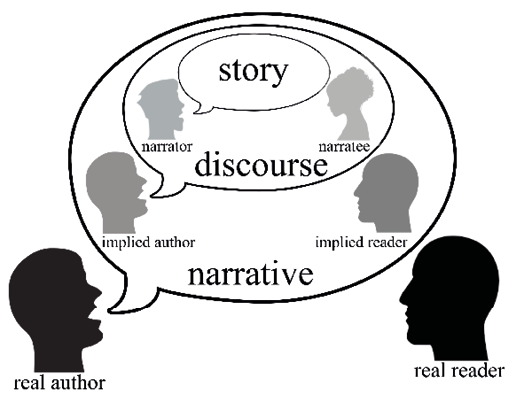

Fig. 1.5 Semiotic model of narrative. By Ignasi Ribó, CC BY.

The semiotic or communicative model of narrative that will be developed in this textbook (see Fig. 1.5) begins by distinguishing the real people who participate in the communicative act of writing and reading (the real author and the real reader) from their textual or implied counterparts.

Thus, the ‘implied author’12 is not the actual individual who wrote the book, but a projection of that individual in the book itself. For instance, Ernest Hemingway (Fig. 1.6) was born in 1899, wrote novels like The Old Man and the Sea and short stories like ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro,’ and died in 1961. When we read one of his narratives, we are not listening to him telling us a story (how could we?), but to a virtual persona to whom we can attribute a style, attitudes, and values, based on what we find in the text itself.

Similarly, although we are the actual readers, the text does not address us as particular individuals. Otherwise, every book could only have a single intended receiver and the rest of us would be eavesdroppers. But books, unlike letters, are generally addressed to an abstract or generic receiver. We can define the notion of ‘implied reader’13 as the virtual persona to whom the implied author is addressing the narrative, as can be deduced from the text itself. When anyone of us, at any time, picks up a Hemingway novel or short story and starts to read it, we are effectively stepping into the shoes of its implied reader.

Fig. 1.6 Ernest Hemingway posing for a dust-jacket photo by Lloyd Arnold for the first edition of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), at Sun Valley Lodge, Idaho, 1939. By Lloyd Arnold, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:ErnestHemingway.jpg

Once we move into the narrative text itself, which already contains an implied author and an implied reader, both only circumstantially related to human beings in the real world, we need to distinguish two different levels of communication: discourse and story.14

At one level, there is the message that the implied author sends to the implied reader. We will call this message ‘discourse.’ Narrative discourse is the means through which the narrative is communicated by the implied author to the implied reader. It includes elements like:

- Narration (narrator and narratee, point of view, etc.)

- Language

- Theme

Fig. 1.7 Semiotic model of narrative shown in speech bubbles. By Ignasi Ribó, CC BY.

The content of narrative discourse is a ‘story.’ But the story is not told directly by the implied author to the implied reader. It is the narrator (a figure of discourse) who tells the story to a narratee (another figure of discourse). Sometimes, narrators and narratees are also characters in the story, but at other times they are not. Therefore, we cannot say that narrators or narratees are people, nor even characters. Both exist only in narrative discourse. The story, then, is simply what the narrator communicates to the narratee (see Fig. 1.7). It includes elements like:

- Events (plot)

- Environments (setting)

- Characters (characterisation)

In the next chapters, we will examine all these elements in more detail. First, we will look at the key elements of story: plot, setting, and characterisation. Then, we will examine the key elements of discourse: narration, language, and theme. While reading these chapters it is important to keep in mind the fundamental distinction between story and discourse, without which many aspects of narrative fiction cannot be properly understood.

1.5 Beyond Literature

As we have seen, narratives are not confined to literary works. Certainly, novels and short stories have been the privileged vehicles of storytelling since the European Renaissance until the present day. But the invention of other media, such as cinema, television, or the Internet, has been rapidly changing the way people produce and consume narratives.

During the twentieth century, cinema developed into an alternative medium to tell the kind of stories that previously were the domain of novels or plays. Like novels, movies are narratives that present a sequence of events connected by time and cause. Unlike novels, however, movies are not meant to be read, but to be watched. In this sense, movies are like theatre plays: they show a performance of the events, environments, and characters of the story, rather than having a narrator convey those events, environments, and characters through words. Of course, cinema is not completely like drama, because the camera, by selecting and framing the events presented in the narrative, acts in some ways like a narrator. In fact, we may well consider cinema a new narrative form, one that draws both from the epic (prose fiction) and dramatic (stage play) genres.15

The intimate relationship between literary and cinematographic narratives is clearly shown by the fact that many movies have tried to retell the stories found in prose fiction. In general, a narrative based on a story previously presented in a different medium is called an adaptation. In some cases, prose fictions are also adaptations, for example when they take their stories from journalistic accounts, history books, or even movies. Much more common, however, is for movies to attempt to bring successful novels and short stories to the screen. For example, J. K. Rowling’s series of novels about the adventures of the young wizard Harry Potter and his friends has been adapted into popular movies by Hollywood (see Fig. 1.8). Television has also drawn many of its fictions from literary narratives. One example is the adaptation of George R. R. Martin’s series of medieval fantasy novels A Song of Ice and Fire into a successful television show, Game of Thrones.

.png)

Fig. 1.8 Warner Bros. Studio Tour London: The Making of Harry Potter. Photo by Karen Roe, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Making_of_Harry_Potter_29-05-2012_(7528990230).jpg

Adaptations are always the subject of passionate debate and controversy. Many attempts to adapt great novels to cinema or television have been negatively received by spectators, who decry the lack of respect for the original story or find the movie less engaging and pleasing than the novel. Less frequently, film adaptations are acclaimed by spectators and critics as superior to the novels or short stories that inspired them.

What most people tend to forget is that adaptations are not translations of the original works. Rather, an adaptation is always an interpretation. In the same way that two readers will never read the same novel, because their interpretation of the events, environments, and characters represented in the story will be different, an adaptation is necessarily a subjective reading of the original text. Moreover, adaptations are creative interpretations, because they produce new texts or semiotic representations (cinema, television, comic, videoclip, etc.) driven by their own artistic motivations and structural constraints.

The fact is that stories cannot be contained in any particular medium or restricted to any predetermined set of rules. Once they have been told, in whatever form or shape, and as long as people pay attention to them, they become part of our cultural makeup. People are free to read them and use them as they like, whether it is for their own private enjoyment, or to adapt, transform, and share them with others. These adaptations may try to be as faithful as possible to what the adapter thinks is the original intention of the author or the true meaning of the text. But they can also subvert those meanings through irony, humour, and commentary, like the memes that proliferate in the Internet era. At the end of the day, stories are not there to be revered and conserved in a state of purity. They constitute the fundamental means by which we humans give meaning to our world. And as such, they are always open to new interpretations.16

Summary

- Narrative is the semiotic representation of a sequence of events, meaningfully connected by time and cause. Literary narratives use written language to represent the connected sequence of events.

- There are many ways to classify literary narratives into different genres, according, for example, to the truthfulness of the events (fiction and nonfiction), to the way the story is told (prose and verse), to the length of the story (novel and short story), or to the content of the story (adventure, science-fiction, fantasy, romance, etc.).

- Prose fiction is narrative written without a metrical pattern that tells an imaginary or invented story. The most common genres of prose fiction in modern literature are novels and short stories. Novels tend to be much longer than short stories.

- The semiotic model of narrative, developed in the field of narratology, makes a key distinction between discourse (how the narrative is conveyed from the implied author to the implied reader) and story (what the narrator tells the narratee).

- Prose fictions are part of the manifold narratives that we humans use to communicate relevant meanings to each other through a wide variety of media, such as film, television, comics, etc.

References

Abbott, H. Porter, The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511816932

Bal, Mieke, Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative (Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press, 2017).

Barthes, Roland, ‘Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative,’ in A Roland Barthes Reader, ed. by Susan Sontag, trans. by Stephen Heath (London, UK: Vintage, 1994), pp. 251–95.

Bascom, William, ‘The Forms of Folklore: Prose Narratives,’ The Journal of American Folklore, 78:307 (1965), 3–20.

Booth, Wayne C., The Rhetoric of Fiction (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

Buchanan, Daniel Crump, One Hundred Famous Haiku (Tokyo: Japan Publications, 1973).

Burroway, Janet, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226616728.001.0001

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin, Reading Narrative Fiction (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1993).

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

Cobley, Paul, Narrative (London, UK: Routledge, 2014).

Eco, Umberto, The Open Work (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989).

Herman, David, Basic Elements of Narrative (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444305920

Iser, Wolfgang, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

Johansen, Jørgen Dines, Literary Discourse: A Semiotic-Pragmatic Approach to Literature (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442676725

Lodge, David, The Art of Fiction: Illustrated from Classic and Modern Texts (New York, NY: Viking, 1993).

Manguel, Alberto, A History of Reading (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2014).

Onega Jaén, Susana, and José Angel García Landa, eds., Narratology: An Introduction (London, UK: Routledge, 1996), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315843018

Stam, Robert, Film Theory: An Introduction (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000).

1 See, for example, William Bascom, ‘The Forms of Folklore: Prose Narratives,’ The Journal of American Folklore, 78:307 (1965), 3–20.

2 Roland Barthes, ‘Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative,’ in A Roland Barthes Reader, ed. by Susan Sontag, trans. by Stephen Heath (London: Vintage, 1994), pp. 251–52.

3 Based on Narratology: An Introduction, ed. by Susana Onega Jaén and José Angel García Landa (London: Routledge, 1996), p. 3, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315843018

4 Haiku by Matsuo Bashō, in Daniel Crump Buchanan, One Hundred Famous Haiku (Tokyo: Japan Publications, 1973), p. 87.

5 Haiku by Matsuo Bashō, in Buchanan, p. 88.

6 H. Porter Abbott, The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511816932

7 See David Lodge, The Art of Fiction: Illustrated from Classic and Modern Texts (New York, NY: Viking, 1993), p. 203.

8 For a detailed history, see Paul Cobley, Narrative (London, UK: Routledge, 2014).

9 Alberto Manguel, A History of Reading (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2014).

10 See Mieke Bal, Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017).

11 David Herman, Basic Elements of Narrative (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444305920; Jørgen Dines Johansen, Literary Discourse: A Semiotic-Pragmatic Approach to Literature (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442676725

12 Wayne C. Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

13 Wolfgang Iser, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

14 See Seymour Benjamin Chatman, Reading Narrative Fiction (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1993); Seymour Benjamin Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

15 See Robert Stam, Film Theory: An Introduction (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000).

16 Umberto Eco, The Open Work (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989).