2. Infrastructure Planning, Challenges and Risks

© C. F. Duffield, R. Duffield, and S. Wilson, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0189.02

2.0 Introduction

As already mentioned in the previous chapter, there is an evident need for improved infrastructure in Indonesia. The Government of Indonesia (GoI) has recognised this, incorporating targets and strategies into a number of national plans which aim to address the issues. The development of infrastructure in Indonesia is also likely to be affected by other large-scale plans, initiatives or doctrines in the region. This chapter briefly outlines relevant national and international plans and initiatives to assist with infrastructure investment and development in Indonesia, and then presents and discusses the challenges, risks and issues associated with delivering the required infrastructure necessary to underpin the economic growth and reform strategies for Indonesia. It details the context for focusing on the development of waterways and ports.

2.1 Infrastructure Plans

2.1.1 National Plans, Agencies and Institutions

Several government agencies, organisations and institutions have been established in Indonesia to help facilitate, drive, coordinate or assist with project preparation. These agencies and institutions further provide guidance on infrastructure development and project planning and delivery within the country.

The National plans set an agenda for national development, economic growth and infrastructure development.

2.1.1.1 Bappenas and Bappenda

Bappenas, the National Development Planning Agency, is a central government organisation responsible for national development planning and budgeting (annual, five-year and long-term) and works with Ministries and local government and agencies so that development planning is more structured, strategic and comprehensive. Bappenas now sits as a Ministry under the President Joko Widodo (KementerianPPN/Bappenas 2017). It is also in charge of planning, evaluation and implementation of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) and coordinates the PPP program. Bappenas releases a PPP Book annually aimed at presenting “reliable information to prospective investors on national PPP projects in the pipeline” (Bappenas 2015a; ERIA 2014). The projects fall under two categories based on readiness: ready to offer projects and projects under preparation. Projects that have been tendered are also listed (Bappenas 2017).

Bappenas coordinates the planning process of projects funded by external loans. It compiles several external loan planning documents including the List of Medium-Term Planned External Loans or Daftar Rencana Pinjaman Luar Negeri Jangka Menengah (DRPLN-JM)/Blue Book and the List of Planned Priority External Loans or Daftar Rencana Prioritas Pinjaman Luar Negeri (DRPPLN)/Green Book.

The Blue Book contains the planned programs and projects which are appropriate to be funded by external loans for the medium-term period, while the Green Book lists planned projects that have a funding indication and are ready to be negotiated within the yearly effective period (Bappenas 2015b; Kementerian PPN/Bappenas 2016a, 2016b). The projects detailed in these books are based primarily on identified needs but do not fully consider the resource implications required to implement the projects described. This has led to few of the projects being deemed “bankable”.

Bappenda is the regional co-ordinator for developments. It has responsibility for implementing projects in the region through the application of Bappenas’s policies. Bappenda seeks to ensure projects are undertaken sustainably and that the financial governance is appropriate. It also manages local approvals, property and local tax revenue (http://bappenda.ntbprov.go.id/).

2.1.1.2 Master Plan for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesian Economic Development 2011–2025 (MP3EI)

In May 2011, the Government of Indonesia released its master plan aimed at transforming Indonesia into a developed nation with an even distribution of wealth and living standards across its regions and an economy within the global top ten by 2025. This ambitious target will involve boosting GDP per capita from approximately USD 3,500 (International Monetary Fund 2015) to USD 14,250–15,500 and nominal GDP from approximately USD 880 billion (International Monetary Fund 2015) to USD 4–4.5 trillion (KP3EI 2012a; Bappenas 2011b; Bappenas 2011a).

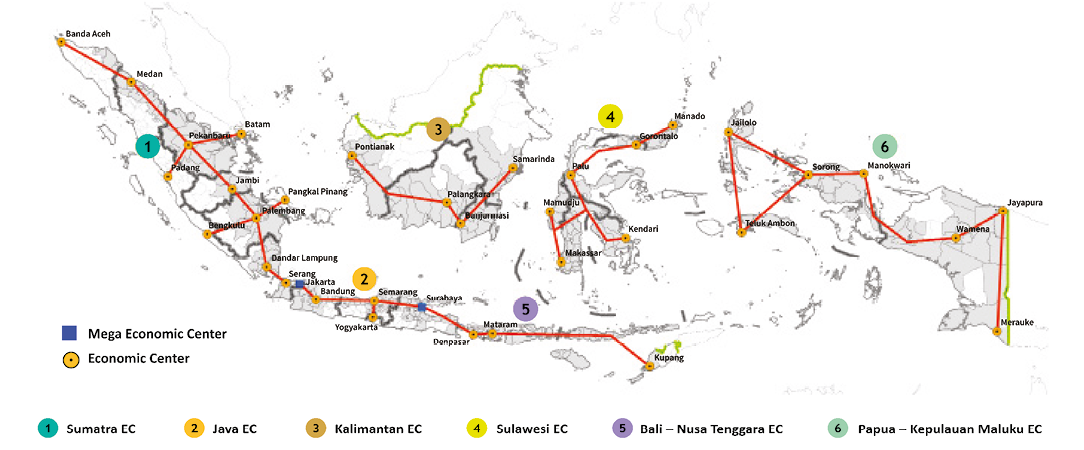

MP3EI outlines three main strategies in order to achieve this rapid economic growth: the establishment of six geographically defined economic corridors (Sumatra Economic Corridor, Java Economic Corridor, Kalimantan Economic Corridor, Sulawesi Economic Corridor, Bali-Nusa Tenggara Economic Corridor, and Papua-Kepulauan Maluku Economic Corridor (Fig. 2.1));4 the improvement of national and international connectivity; and the strengthening of human resource capacity, science and technology (Bappenas 2011b; Bappenas 2011a; KP3EI 2012b).

Fig. 2.1 Indonesian Six Economic Corridors identified for the MP3EI. Source: Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency, 2011 (Bappenas 2011a), Masterplan Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011–25. Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs.

Realisation of these plans will rely heavily upon improved infrastructure and hence this is a major focus of the MP3EI. Of the total IDR 4012 trillion of investment needed across the six corridors, approximately IDR (Indonesian Rupiah) 1725 trillion (or 43%) is expected to go towards infrastructure development (Strategic Asia 2012), with approximately 24% earmarked for power and energy, 23% for roads and toll roads, 13% for railways, 10% for ICT, 8% for ports, 2% for airports and 2% for water and utilities (Oxford Business Group 2014). The majority of this funding will need to be sourced from State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and private companies, largely through PPP arrangements.

The government claims to have made decent progress within the first three years of the plan, with 197 projects being launched by the end of June 2014. This is around 20% of the total 1048 infrastructure projects committed to between 2011 and 2025 and the head of the National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) is optimistic that the planned projects will go ahead (Sipahutar 2014). However, others have criticised the plan for moving at a slow pace (Sambhi 2015) and so far the majority of funding has come from SOEs and government funding (Sipahutar 2014). Private participation has been disappointing and very few projects have been successfully implemented through the PPP scheme. It is hoped that further advancements will be made in the coming years as regulatory and institutional reforms help to stimulate the interest of private and foreign investors (Gustely 2015).

2.1.1.3 National Long-term Development Plan 2015–2025 (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Panjang Nasional abbreviated to RPJPN)

The National Long-term Development Plan (RPJPN) 2005–2025 for Indonesia includes a broad range of targets regarding social, environmental and macroeconomic development, with an overarching objective to improve quality of life, equality and progression in an environmentally sustainable fashion (Government of the Republic of Indonesia and United Nations in Indonesia 2015).

Specific goals of the RPJPN are to:

- Achieve per capita income for residents’ equivalent to middle income countries

- Reduce unemployment to less than 5%

- Reduce the number of poor people to less than 5%

- Increase both the human development index (HDI) and the Gender Development Index (GDI) scores

The RPJPN is divided into four stages. The first two stages of reform have largely been achieved with the country now progressing to stage three of the plan, refer below.

RPJPN 1 — 2005–2009 Reform the Republic of Indonesia such that the country is secure, peaceful, just and democratic, with enhanced prosperity.

RPJPN 2 — 2010–2014 Increase the quality and capacity of human resources in science, technology and strengthen economic competitiveness.

RPJPN 3 — 2015–2019 Enhance economic competitive advantage based on available natural resources, quality human resources and capability in science and technology.

RPJPN 4 — 2020–2025 Realize self-sufficiency through accelerated development in all fields with an economic structure that is based on competitive advantage.

In line with the general focus of the Jokowi government appointed in October 2014, the 2015–2019 medium term plan places a strong emphasis on infrastructure development. The government has set ambitious targets to improve basic infrastructure and connectivity involving a predicted total of IDR 5,519 trillion in investments (Smith et al. 2015a). Approximately 20% of these funds are to be directed towards road and toll road projects; a further 20% will go towards connectivity programs involving railways, urban transportation, sea transportation and aviation; and the final 60% is planned for basic services such as electricity, energy, gas, clean water, waste management, housing and information technology (Priatna 2014).

The state budget was originally expected to fund about 22% of the planned infrastructure projects, with an additional 6% to come from State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and a 50% financing gap to be filled by the private sector (Priatna 2014). However, in January 2015 the Widodo Government abolished generous fuel subsidies, which were set to consume more than 10% of the state budget. This contributed significantly to their ability to increase the infrastructure spending target by 63% in 2015 (IDR 290 trillion) and a further 12% in 2016 (IDR 312 trillion) compared to 2014 (IDR 178 trillion). National and regional government funding is now estimated to account for 50% (IDR 2,761 trillion) of total infrastructure investment from 2015–2019. SOEs are expected to finance 19%, leaving 31% to be covered by private companies (Smith et al. 2015a; Hutapea 2015).

However, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) Indonesia predicts a shortfall of approximately 19% in government infrastructure spending between 2015 and 2019 due largely to systemic issues which are likely to continue causing project bottlenecks (Smith et al. 2015a). The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has also suggested that annual infrastructure spending will need to reach 6.2% of GDP by 2020 in order to meet Indonesia’s needs (Sipahutar 2015). The 2015–2019 capital infrastructure budget allocation represents only around 2.9% of GDP per year, which is below the approximate average of 5.5% of GDP for developing countries (Sukaesih 2014). That said, PwC Indonesia believes sufficient domestic and international funding is available, so long as Indonesia can provide a conducive environment to attract the required amount of private investment (Smith et al. 2015a).

2.1.1.4 Committee for Acceleration of Priority Infrastructure Delivery

By way of the Presidential Regulation no. 75 of 2014, the Committee for Acceleration of Priority Infrastructure Delivery (KPPIP) was established to co-ordinate and facilitate the development of National Strategic Projects and Priority Projects. Whilst the committee reports directly to the President and the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs, it included representation from the Ministries of Finance and National Development along with representatives from Bappenas and the Minister of Agrarian Affairs. The Committee (KPPIP) was established to become a coordinating unit in the decision-making process to address issues related to lack of coordination between stakeholders, to facilitate ‘debottlenecking’ (removal of bottlenecks) efforts, to provide support for priority projects and to provide incentives and disincentives schemes to accelerate project realisation (KPPIP 2016).

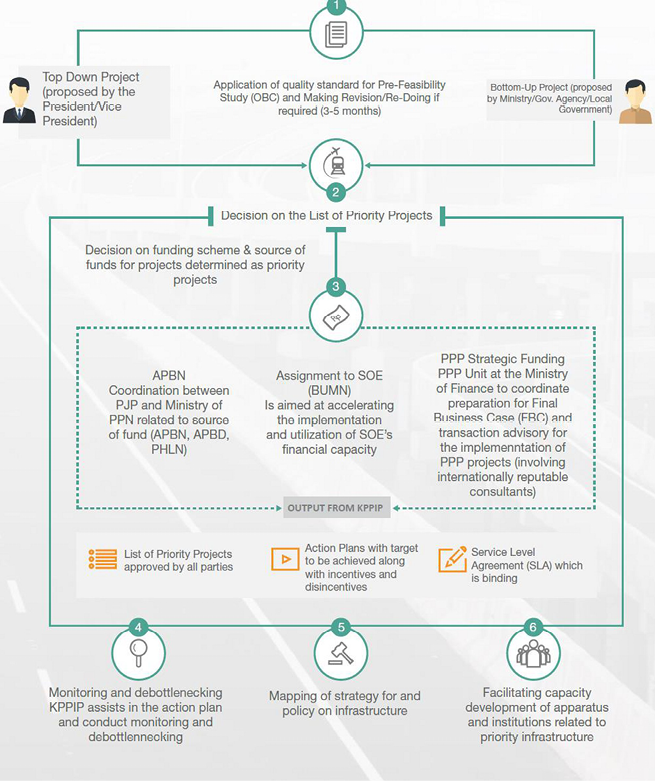

In February 2016, the KPPIP released thirty priority projects for the country based on consideration of top down priorities as proposed by the President/Vice President, and on bottom up projects as proposed by the Ministries, Institutions and Regional governments.

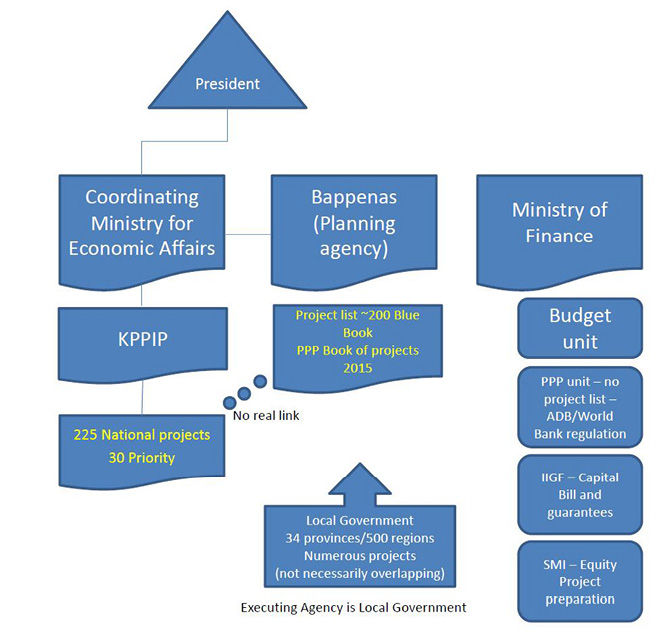

There was little overlap between the thirty KPPIP priority projects with the blue book recommended projects from Bappenas, the MP3EI projects or specific projects as nominated by Institutions and Agencies, referred to in Fig. 2.2.

Fig. 2.2 Relationships between various Indonesian project planning agencies and authorities (figure by the authors)

Specific projects have historically been put forward by Bappenas and Local Governments yet as Indonesia has sought to address the pressures of rapid development, projects may emerge from KPPIP, Bappenas, Local Government or via the numerous mechanism available to attract international finance and/or funds. The Public Private Partnership unit may prioritise projects likely to attract international finance, the World Bank (and or the Asian Development Bank) may provide funds for priority initiatives, the Indonesia Infrastructure Guarantee Fund (IIGF) seeks to identify projects worthy of underwriting, while PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (SMI) — a governmental infrastructure financing company — seeks to raise finance for projects. Once financed, projects gather pace as priorities.

Since its inception in 2014, KPPIP has set about to achieve co-ordination and project prioritisation as detailed in Fig. 2.3 KPPIP process for coordinating project outcomes (Source: KPPIP, 2016).

Fig. 2.3 KPPIP process for coordinating project outcomes. Source: KPPIP, 2016.

In addition to setting priority projects in 2016, KPPIP also assisted in improved project preparation for the following projects:

- Panimbang-Serang Toll Road

- Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Railway

- Bontang Oil Refinery

- Synchronization between the PPP unit in the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of National Development Planning/Bappenas

They also clarified project funding schemes for a range of projects and assisted to improve regulations and overcome bottlenecks.

Even though synergies exist between Central Government Agencies, the provinces and Local Government still have a level of autonomy with respect to the prioritisation of projects.

2.1.1.5 Indonesian Maritime Doctrine 2014

President Joko Widodo (‘Jokowi’) has highlighted maritime development as a key focus of his five-year term. The country currently suffers from a severe lack of inter-connectivity and inefficient port facilities hinder both national and international maritime commerce. The average dwell time of Indonesia’s main port in Jakarta is 6.4 days, much higher than the dwell times of 1.5 and 3 days in nearby Singapore and Malaysia, respectively (Piesse 2015). In his maritime doctrine, Jokowi outlined plans to upgrade or construct twenty-four seaports and deep seaports over five years as a part of the ‘sea toll road’ program. The resulting increase in domestic connectivity and reduced transportation costs are expected to boost economic development through enhanced trade and competitiveness.

Furthermore, it is hoped that the improved infrastructure and bigger ports will provide a platform for increased international shipping traffic. By expanding diplomatic attention beyond the Pacific and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) regions and into the Indian Ocean, Jokowi intends to establish Indonesia as a ‘global maritime axis’, acting as a powerful international hub for sea trade. The policy also outlines plans to improve national security and expand the fishing and shipbuilding industries (Shekhar and Liow 2014; Piesse 2015).

As a part of the National Medium Term Development Plan 2015–2019, the majority of funding for Jokowi’s maritime vision is being sought from private and foreign direct investment. In December 2014 the government stated that approximately USD 7 billion was needed from foreign investors for the planned sea toll road project, “a coordinated network of ports designed to better handle international traffic and streamline more local trade” (Dodd 2015). Investment interest is strong and there are already a number of companies, development banks and foreign governments taking part, with upgrades to some of the ports now underway (Sambhi 2015; Dodd 2015). In November 2015 the government also launched a subsidised freight service program along its ‘sea toll road’, linking major ports between Java, Papua, Maluku and Riau Islands (The Jakarta Post 11 November 2015, editorial). While the government certainly faces challenges ahead, the maritime doctrine has largely been received with support and positivity.

2.1.2 International Plans

There are several plans from bodies, other than the Indonesian government, with relevance to the development of infrastructure in Indonesia.

2.1.2.1 ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Connectivity Agenda

The 2011–2015 Master Plan on ASEAN connectivity included strategies for the development of roads, railways, ports, aviation facilities, ICT and electricity (ASEAN 2010). Discussions on a post-2015 ASEAN Connectivity agenda were held at the 6th ASEAN Connectivity Symposium in October 2015 (ASEAN 2015).

2.1.2.2 APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Connectivity Blueprint 2015–2025

Initiated in 2013 by Indonesia, the APEC connectivity blueprint outlines targets and strategies for the strengthening of physical, institutional and people-to-people connectivity within the Asia-Pacific region. Included in this blueprint are plans to improve both regional and domestic infrastructure in the sectors of maritime, air, roads, railways, ICT and energy. A key focus will be to improve the investment climate and encourage private sector participation through PPP arrangements. To this end, an APEC PPP Experts Advisory Panel was created, which will support a pilot PPP centre established within Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance (APEC 2014, Andres 2015). The role of this PPP centre will be to provide technical expertise, assist in the development and reviewing of project structures, remove bottlenecks and identify problems with the aim of increasing coordination and overall delivery of infrastructure projects (APEC 2013). The APEC connectivity blueprint also contains methods for increasing infrastructure quality through improved project assessment and evaluation practices (APEC 2014).

2.1.2.3 Master Plan of ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC) 2025

The MPAC 2025 was ratified in 2016 with a focus on five strategic areas: sustainable infrastructure, digital innovation, seamless logistics, regulatory excellence and people mobility. The strategic objective of sustainable infrastructure is to increase public and private infrastructure investment in each ASEAN Member State, as required; and to significantly enhance evaluation and sharing of best practices on infrastructure productivity in ASEAN. This would include project preparation, improving infrastructure productivity and capability building. Another objective of sustainable infrastructure would be to increase deployment of smart urbanisation models across ASEAN. A strategic objective related to seamless logistics is to lower supply chain costs and improve speed and reliability of supply chains in each ASEAN member state (ASEAN 2016).

The MPAC noted a projected undersupply of skilled and semi-skilled workers in Indonesia by 2030.

2.1.2.4 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative

In 2013, the President of China announced his vision to build a trade network or ‘Maritime Silk Road’ running from China through Indonesia, into the Indian Ocean and beyond. Upgrades to Indonesian maritime infrastructure will have clear benefits for Chinese trade and indeed the Chinese foreign minister has expressed that the Chinese government is willing to contribute to Indonesian infrastructure projects (Piesse 2015). Both President Widodo and the Indonesian presidential advisor for foreign policy, Rizal Sukma, have indicated that Indonesia’s Maritime Doctrine and China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative are highly complementary and contain overlapping aims (Piesse 2015). According to the Chinese Ambassador to ASEAN, Xu Bu, ASEAN is a key starting point for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative and China intends to increase China-ASEAN maritime cooperation (Bu 2015). The Maritime Silk Road complements the Silk Road Economic Belt (which is focused on infrastructure development across Central Asia) and together these make up the One Belt One Road initiative (Szechenyi 2018).

2.1.2.5 Indonesia-Malaysia-Thailand Growth Triangle Implementation Blueprint 2012–2016

The Indonesia-Malaysia-Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT) is a subregional economic cooperation program that was established in 1993. Following the 2007–2011 Roadmap for Development, which delivered modest results, the cooperation has established more solid frameworks and strategies for delivering projects in the 2012–2016 implementation blueprint. One of the aims of the program is to strengthen infrastructure linkages, connectivity and transport in the region, with a focus on five specific land and maritime connectivity corridors. Included in the Blueprint are six priority infrastructure projects within Indonesia, amounting to a total estimated cost of USD 4545 million to be covered by the Indonesian government, Asian Development Bank and the private sector (Asian Development Bank 2012). The mid-term review found that project implementation in transport and infrastructure was encouraging (Asian Development Bank 2015). However, the review also noted that “most major (transport) projects in the priority corridors (in the IMT-GT) were still in the feasibility, design or pre-construction stage”. The IMT-GT implementation blueprint for 2017–2021 has now been adopted.

2.2 Challenges, Risks and Issues Affecting Infrastructure Processes and Development in Indonesia

The Indonesian Government has set ambitious targets for improvements to infrastructure, but many challenges and issues stand in the way of meeting these targets. The main challenge is funding.

The Indonesian Government needs funding from the private sector and while there is great potential for investing in the Indonesian economy, investment remains below the targets set by the Indonesian Investment Co-ordinating Board (BKPM). The Indonesian Government has estimated that it will only be able to provide approximately 35% of funds required and that local and international finance is being sought to participate in infrastructure investments via the use of PPPs as alternative sources of development financing (Duffield 2014).

There are several in-country issues and risk factors that are responsible for reducing the interest of foreign investors. Many of these factors, such as problems with regulations and processes, are a common cause of project bottlenecks. Such delays not only deter investors but are a direct hindrance to the progression of infrastructure development.

The next section explores these issues and risk factors. It discusses the challenges that must be addressed by researchers to address some of these infrastructure system barriers and examines what has been done to date.

2.2.1 Issues and Risks

As already mentioned, lack of infrastructure in Indonesia, in particular in transportation, logistics and water treatment, is impeding economic, business and social development in Indonesia (OECD 2016). This discourages competitiveness and foreign investment as well as international trade (OECD 2016).

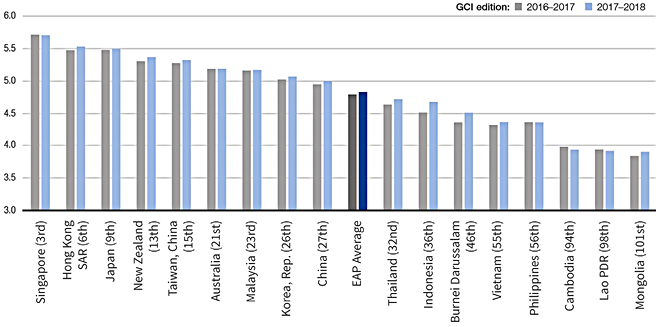

The World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report presents information and data related to competitiveness on 137 countries around the world. Competitiveness is defined as “the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of an economy, which in turn sets the level of prosperity that the economy can achieve” (World Economic Forum 2017).

In 2017/18 in the Global Competitiveness Index, Indonesia ranked 36 out of 137 countries (score 4.68) an improvement from 2016/17 when it was ranked 41 (score 4.52) (Fig. 2.4).

Fig. 2.4 Global Competitiveness Index* scores for East Asia and Pacific countries. Source: World Economic Forum 2017, The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018.

*The GCI measures all indicators on a 1–7 scale and aggregates the scores to find a final overall GCI score. The higher the score the better the measure being assessed.

The 2017/18 Global Competitiveness Report notes that Indonesia (amongst major emerging markets) is becoming a centre for innovation. However, there is a need for the country to increase the readiness of its people and firms to adopt new technology. In terms of technological readiness, Indonesia is ranked 80th despite progress in the last decade (World Economic Forum 2017).

Labour market efficiency is reported as 96th, with the ranking attributed to “excessive redundancy costs, limited flexibility of wage determination, and a limited representation of women in the labour force”.

In terms of Infrastructure, Indonesia ranked 52 out of 137 countries with quality of port infrastructure ranked 72 (World Economic Forum 2017).

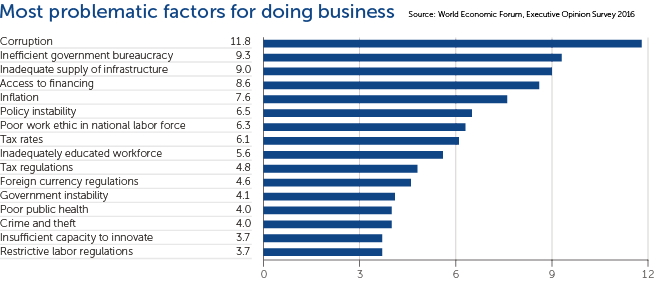

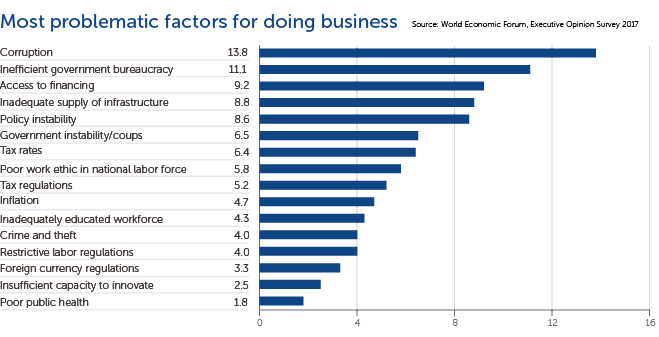

Numerous issues have been identified as problematic to doing business in Indonesia (World Economic Forum 2016). The most problematic factors for doing business in Indonesia, as identified by business executives in a survey from the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey 2016 and again in 2017, are shown in Fig. 2.5 and 2.6 respectively. A comparison between the two figures highlights the shift in problematic factors over this period. Corruption, inefficient government bureaucracy remained number 1 and 2 as most problematic in 2017, but access to financing rose in rank replacing inadequate supply of infrastructure as number 3. Policy instability also rose to 5th position as most problematic to doing business in Indonesia.

Fig. 2.5 The most problematic factors for doing business in Indonesia 2016. Source: World Economic Forum 2016, Global Competitiveness Report 2016–2017.*

*This chart summarizes those factors seen by business executives as the most problematic for doing business in their economy. The information is drawn from the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey (the Survey). Note: From the list of sixteen factors, respondents to the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey were asked to select the five most problematic factors for doing business in their country and to rank them between 1 (most problematic) and 5. The score corresponds to the responses weighted according to their rankings.

Fig. 2.6 The most problematic factors for doing business in Indonesia 2017. Source: World Economic Forum 2017, The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018.

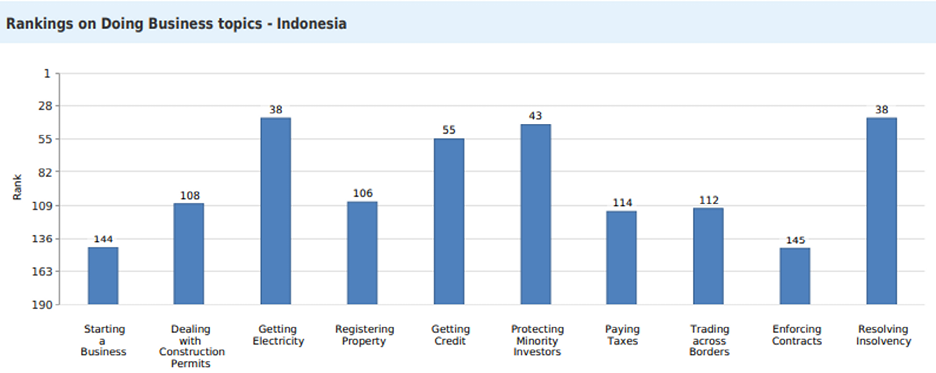

Separate to the World Economic Forum (WEF) survey which examines factors problematic for doing business in the country, the World Bank also conducts research into the “ease of doing business” to provide an economy profile for 190 economies in the world (World Bank 2018). These items provide an objective measure of business regulations and their enforcement across 190 economies and selected cities.

In 2017, Doing Business (DB) Rankings were conducted on ten topics (Figs. 2.7 and 2.8):

- Starting a business: Procedures, time, cost and paid-in minimum capital to start a limited liability company

- Dealing with construction permits: Procedures, time and cost to complete all formalities to build a warehouse and the quality control and safety mechanisms in the construction permitting system

- Getting electricity: Procedures, time and cost to get connected to the electrical grid, the reliability of the electricity supply and the transparency of tariffs

- Registering property: Procedures, time and cost to transfer a property and the quality of the land administration system

- Getting credit: Movable collateral laws and credit information systems

- Protecting minority investors: Minority shareholders’ rights in related-party transactions and in corporate governance

- Paying taxes: Payments, time and total tax rate for a firm to comply with all tax regulations as well as post-filing processes

- Trading across borders: Time and cost to export the product of comparative advantage and import auto parts

- Enforcing contracts: Time and cost to resolve a commercial dispute and the quality of judicial processes

- Resolving insolvency: Time, cost, outcome and recovery rate for commercial insolvency and the strength of the legal framework for insolvency

In 2018, Labour market regulation — flexibility in employment regulation and aspects of job quality — was added as an indicator.

Fig. 2.7 World Bank Rankings on Doing Business topics — Indonesia. Source: World Bank 2018. Doing Business 2018 — Indonesia. World Bank Group.

Fig. 2.8 Distance to Frontier (DFT) on Doing Business topics — Indonesia. Source: World Bank 2018. Doing Business 2018 — Indonesia.

The ease of doing business rank for Indonesia is 72 (out of 190) and the Doing Business 2018 distance to frontier (DTF) is 66.47 (out of 100).5

2.2.1.1 Corruption

Corruption throughout the political, judicial and corporate domains has been an ongoing problem within Indonesia. Corruption continues to feature as the most problematic factor for doing business in Indonesia as seen in The World Economic Forum’s executive opinion survey (Figs. 2.5 and 2.6).

In the Corruption Perceptions Index in 2014, Indonesia was ranked 107th out of 175 countries, tracking alongside Albania, Ecuador and Ethiopia (Transparency International, 2014). In 2017 Indonesia was ranked 96 out of 180 countries with a score of 37 out of 100 (where 0= highly corrupt and 100=very clean) (Salas 2018) (https://www.transparency.org/country/IDN).

A lack of trust in the system can be a major deterrent for investors and corrupt practices may curb the development of a sound infrastructure investment framework. However, approaches taken to tackle corruption (outlined below) appear to be improving the situation.

What Is Being Done?

In March 2012, the Indonesian Government issued the National Strategy of Corruption Prevention and Eradication which has medium and long-term plans to achieve the vision of an anti-corruption nation.

The corruption eradication commission — Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK) — was established in 2002/3 (Indonesian investments 2017). This is the main public anti-corruption institution. The Commission is a government agency envisaged to free Indonesia from corruption by investigating and prosecuting cases of corruption as well as monitoring the governance of the state. The KPK is required to:

- “Coordinate with, and supervise, other institutions authorised to fight corruption.

- Conduct preliminary investigations, investigations and prosecutions of corruption.

- Seek to prevent corrupt activity.

- Monitor state governance” (Centre for Public Impact 2016).

Opinions are divided regarding the success of this agency, but there are indications that corruption is improving — for instance, the 2015 global competitiveness report indicated that ‘Indonesia improve[ed] on almost all measures related to bribery and ethics’ (World Economic Forum 2015). Transparency International notes that the slight improvement in the corruption index for Indonesia may be from the work of Indonesia’s leading anticorruption agency acting against corrupt individuals (Salas 2018).

President Jokowi is committed to combatting corruption (Indonesian Investments 2016, 2017). Media reports indicate that the President is encouraging the Police, the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) and the prosecution office to strengthen their commitment and cooperation in fighting corruption (Antaranews.com 2015).

2.2.1.2 Environmental Risks

Indonesia is situated on the Pacific Ring of Fire and hence is at an extremely high risk of experiencing floods, tsunamis, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The resulting damage to infrastructure comes at a high cost and given the choice, investors may be inclined to support less risky projects.

Poor quality of build is also a concern in areas prone to natural disasters or extreme weather phenomena.

2.2.1.3 Land Acquisition

The process of acquiring land for the implementation of infrastructure projects has been a common cause of project delays and cancellations. Lack of clear regulations regarding land rights, such as land acquisition for public use and the provision of compensation to land owners, has often led to lengthy and complicated disputes.

Issues, such as informal land ownership in Indonesia, have resulted in increased ‘rights to land’ claims during land acquisition processes, with some land owners holding onto their land as long as possible as a project progresses, so as to benefit from land appreciation during that time (KPMG Indonesia 2015).

According to the Indonesia Infrastructure Initiative, it takes a minimum of 4–5 years to identify and acquire land for a major project in Indonesia (Lee 2015). The government has taken a number of steps to try and establish a clear administrative process and legal framework to deal with this issue.

A 2015 report from PwC (Smith et al. 2015a) lists land acquisition as one of several economy wide factors for success, stating that: “Land acquisition has historically delayed many projects. The new law is welcome, but it is too soon to tell whether this will solve the problem. The lack of clear, nationwide land tenure recognised by the national and subnational government agencies as well as the courts will remain an ongoing challenge.”

What Is Being Done?

In 2012, a new law on Land Procurement for Public Interest (UU no. 2/2012) was introduced to try and speed up the process of land acquisition. It addressed the revocation of land rights to serve public interest, introduced procedural time limits and ensured safeguards for land-right holders (KPMG 2015; Indonesian investments 2016).

Since then, the new Government has released Presidential Regulation no. 30 of 2015 on Land Acquisition for Public Projects. This regulation facilitates private investment during the land acquisition process which can be “refunded from the state budget based on the calculated projected return on investment” (GBG Indonesia 2015).

National Land Agency (BPN)

In addition, Presidential Regulation no. 63 of 2013 on National Land Agency (BPN) is expected to facilitate land acquisition through organisational changes to BPN, such as the establishment of regional BPN offices and a deputy office for land procurement.

A 2015, a PwC report with research by Oxford Economics (and a subsequent 2016 report) notes that “Land acquisition bill: Law no. 2/2012 and Presidential Regulation no. 71/2012 regarding Land Acquisition for Public Interest, effective as of 2015, limit the land acquisition procedure to 583 days and allows for revocation of land rights in the public interest. This is crucial as many projects have been held up by extended land acquisition disputes” (Smith et al. 2015a, 2016).

2.2.1.4 Transaction Law

In 2015, a new Rupiah Transactions Regulation (Bank Indonesia Regulation no. 17/3/PBI/2015) was introduced, which mandates the use of Indonesian currency for all transactions on some projects. This is likely to make such projects less attractive to foreign investors (Smith et al. 2015a). New regulations continue to be released.

2.2.1.5 Public Private Partnership (PPP) Process

Sourcing private funding for infrastructure projects is expected to be predominantly achieved through PPP arrangements. However, there are problems with the current PPP framework in Indonesia: the current framework discourages private investors from entering into such agreements, while a lack of project success stories weakens confidence in the system.

Unclear regulations; unclear or complicated/inefficient processes; problems of excessive bureaucracy within government institutions; lack of coordination among central, provincial and regional governments all result in bottlenecks in PPP procurement. All projects currently listed as ‘ready for tender’ in the 2013 PPP book are stalled (Smith et al. 2015a). This remains the case in 2016 (Smith et al. 2016).

Many projects are not designed, documented and structured in line with international best practices (Smith et al. 2015a). There is a need for new risk management tools to avoid infrastructure project development, delivery and financial risks falling to the private sector, when they were traditionally the responsibility of the Government.

According to a 2014 McKinsey report (Lin 2014), “Most PPP projects are stuck in the preparation and transaction stages.”

What Is Being Done?

Improvements to regulatory framework

Presidential Regulation no. 38 of 2015 on Cooperation between Government and Business Entity in Infrastructure, as a replacement of Presidential Regulation 67/2005 and its amendments, established clearer and more detailed stipulations about unsolicited proposals, cooperation agreements and Government’s support and guarantees to projects, among other points (Bappenas, 2015). This allows for performance-based annuity schemes which are a more appropriate risk model for many of the proposed PPP projects in Indonesia.

Improvements to institutional framework

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the Committee for Acceleration of Priority Infrastructure Delivery (KPPIP) was established to co-ordinate and facilitate the development of National Strategic Projects and Priority Projects. Since its inception in 2014, KPPIP has set about to achieve co-ordination and project prioritisation. The establishment of KPPIP should help with coordination among governments.

Currently the organisation is chaired by the Minister of the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs (CMEA) and the head of BAPPENAS. It was formed at the initiative of BAPPENAS, the Ministry of Finance and the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs, in recognition of the need to create an effective coordination framework with strong political leadership to reinforce its infrastructure program in general, and that of PPPs in particular.

KPPIP has a “crucial role in priority projects development and implementation, starting from project selection up to ground-breaking — positioned as the Project Management Office (PMO) for priority projects. It also has a central role in coordinating related stakeholders in priority projects implementation through the action plan development facilitation, monitoring and debottlenecking as well as providing incentives and disincentives schemes to accelerate the project realization” (KPPIP 2016).

The Indonesia Infrastructure Guarantee Fund (IIGF) (see Chapter 3) provides guarantees against infrastructure risks for projects under the PPP scheme and reduces risk for private investors (Indonesian investments 2016).

A 2015 PwC report noted that “Presidential Regulation no. 67/2005 has just been superseded by Presidential Regulation no. 38/2015 to stimulate investment in Public Private Partnership projects by expanding eligible sectors and offering a more favourable legal framework” (Smith et al. 2015a; Smith et al. 2018).

Several public finance institutions such as the Indonesia Infrastructure Guarantee Fund (IIGF), Indonesia Infrastructure Finance Company (PT SMI) and PT Indonesia Infrastructure Finance (IIF) have been set up to support measures/reforms introduced by the Indonesian Government to aid private sector participation (Smith et al. 2015a; Smith et al. 2018). These are briefly outlined in Chapter 3.

2.2.1.6 Political Instability

There is always a certain level of political risk involved when investing in a project — for example, a change in government or regulation may lead to project delays or cessations. Given the election of a new and popular government in 2014, this risk is currently quite low. However, there is a lack of united Parliamentary support for President Jokowi. Disagreements within his own party and a disruptive opposition may hinder reforms relevant to the implementation of the infrastructure program.

2.2.1.7 Regulatory and Legal Uncertainty

Unclear, conflicting laws and regulations contribute to uncertainty — for example, uncertainty on the right of the private sector to participate in a specific project. A lack of coordination exists between the central, provincial, and regional governments (Smith et al. 2015a). Infrastructure sector specific laws are inconsistent and there is wide variation between sectors. A strong, centralised strategy for infrastructure and PPPs, with clearly defined roles for different levels of government would help address this (Smith et al. 2015a).

Coordination is essential for infrastructure development to be effective. Regional autonomy contributes to regional regulations conflicting with central government law. Lack of clarity and alignment increases risk for the private sector. This may lead to double taxation.

Government policy must be streamlined to allow for a bigger participation from the private sector. Regulations must be clear and without any possibility for misinterpretation in order to encourage trust and maximize participation from investors to build much-needed industries and infrastructure. In order to achieve the above objectives, all existing regulatory frameworks must be evaluated, and strategic steps must be taken to revise and change regulations

2.2.1.8 Lack of Projects

Despite an infrastructure deficit, there is a lack of projects in the pipeline. According to Gustely, this is due to a general lack of institutional capacity and capability. Contracting government agencies fail to efficiently develop, prepare and execute projects (Gustely 2015).

However, total projects in the 2015 PPP Book increased to 38, compared to 27 projects in the 2014 book due to new proposals submitted by ministries and local government.

2.2.1.9 Insufficient Human Capital

Rapid economic growth and deficiencies in education have led to a demand for skilled professionals and technicians greater than available supply. This is despite there being a large potential workforce in Indonesia.

There is a problem with workers falling short of employer expectations, and skills not being “up to scratch” — the minimum wage may not match low productivity. Lack of skills leads to bottlenecks and project delays. Indonesian labour laws are intended to safeguard employees. Minimum wages can vary across regions and industries (KPMG 2015).

The employers’ ability to terminate underperforming workers is heavily restricted under labour laws, and high severance and termination benefits are payable. This is particularly relevant once a project reaches the phase of construction as it may result in decreased efficiency and increased times to complete projects, leading to increased costs — a risk factor that may deter investors.

Shortages of skilled labour are not helped by tightening immigration regulations.

The quality of human resources is a big challenge for Indonesia. Currently only about 50% of workers in Indonesia have enjoyed primary school education, and only 8% have a formal diploma. Quality of human resources is affected by access to quality education and health facilities, as well as access to basic infrastructure.

2.2.1.10 Bureaucracy

Inefficient government bureaucracy features second on the list of most problematic factors for doing business in Indonesia from the World Economic Forum, Executive opinion survey (World Economic Forum 2016; World Economic Forum 2017; Figs. 5 and 6). A 2015 KPMG report mentions that “excessive bureaucracy and a lack of coordination at the ministerial level was considered to be undermining the country’s business environment” (KPMG 2015).

What Is Being Done?

Investment coordinating Board BKPM

A 2015 PwC report noted that “the Investment Coordinating Board, BKPM One Stop Service now provides a centralised licensing point for certain sectors, which should increase the efficiency of the investment approval process” (Smith et al. 2015a). It acts as the primary interface between business and government and is authorized to “boost domestic and foreign direct investment through creating a conducive investment climate” (BKPM 2015). The BKPM serves as a ‘front office’ for investor relations through packaging information on show-case projects or the marketing of projects.

As mentioned earlier, the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified the need for a unified voice to identify and support priority projects, and to provide guidance on best practice for the delivery of projects. The Indonesian government has responded through the establishment of the Public Private Partnership (PPP) centralised unit within the Ministry of Finance that works closely with BAPPENAS, the KKPPI for policy formulation and the State Infrastructure Guarantee Company for PPP projects.

Public Private Partnership Central unit (P3CU)

The Public Private Partnership Central Unit (P3CU) is seen as an independent, centralized organization dedicated to a wide range of PPP related functions, such as policy formulation, provision of guidance and dissemination of information. It will have access to fiscal budget allocation decisions. “This dedicated unit will be placed under a high-level political leadership and decision-making institution that has the authority to:

- coordinate across planning and fiscal agencies;

- decide on cross-ministerial conflict resolution;

- drive legislative improvements.” (Parikesit and Laksmi 2015).

The P3CU will be responsible for ensuring policy consistency, quality control and transparency, establishing standards and principles that all transactions must follow, and monitoring the execution for compliance. The unit was formed due to the devolution of planning, preparation and transaction to ministries and contracting agencies — P3CU will assist line ministries and local governments in identifying, preparing, and implementing PPP projects. The unit will prioritize PPP projects according to their development impact and their readiness toward implementation.

The roles for P3CU include: reviewing project evaluation carried out by the PPP nodes, assessing requests for Government support to PPP projects and coordinating such support with the Ministry of Finance, publishing status reports on PPP projects and disseminating relevant information, preparing guidelines and manuals for PPP projects, and building capacity in the PPP nodes (Bappenas 2015).

2.2.1.11 Economic Outlook

While the long-term economic outlook for Indonesia is positive, there is a risk that projected growth targets will not be reached. Success relies upon a enough investment to boost growth and provide employment for the rapidly growing population. If the estimated growth of 8–9% that is required to support the fifteen million people entering the workforce by 2020 (World Bank 2014a) is not achieved, an increasing number of unemployed will place a strain on society and stunt economic performance. Some may also fear the impact of unequal wealth distribution and a growing number of people living below the poverty line.

2.2.1.12 Foreign Currency

Currency exchange rates present a risk to investment in any foreign economy. Since early 2014 the Indonesian Rupiah has been experiencing significant depreciation, putting potential investors at risk of exchange losses.

2.2.1.13 Dispute Resolution

The Judicial system in Indonesia needs significant reform — Indonesian courts are not the preferred method for investors enforcing contractual rights. “There are frequent reports that Indonesia’s judiciary institutions are not free from corruption and are not fully independent from the other political branches. Litigation can be unpredictable in terms of outcomes, protracted and time consuming.” (Indonesia Investments, ‘General Political Outline of Indonesia’).

2.2.2 Research into Barriers to Doing Business in Indonesia and Australia

A research project into the Efficient Facilitation of Major Infrastructure Projects was undertaken between 2016–2018 to enhance our understanding of which investment strategies and options facilitate project initiation that attracts international engagement for major infrastructure development in Indonesia and Australia, with a focus on ports.

This research project is a collaboration between The University of Melbourne and The Universitas Indonesia, Universitas Gadjah Mada and Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember as part of the work from the Australian-Indonesia Centre Infrastructure Cluster Research Group research project.

As part of the study, an online questionnaire was developed for key stakeholders associated with ports in both Indonesia and Australia. The focus of the survey was Port Planning and Development and sought to investigate:

- Which investment strategies and options facilitate project initiation that attracts international engagement?

- How to effectively plan and develop existing ports and new ports to increase regional and national productivity?

- What related infrastructure development is necessary to support the port and port development?

The full research methodology is outlined in Appendix 1.

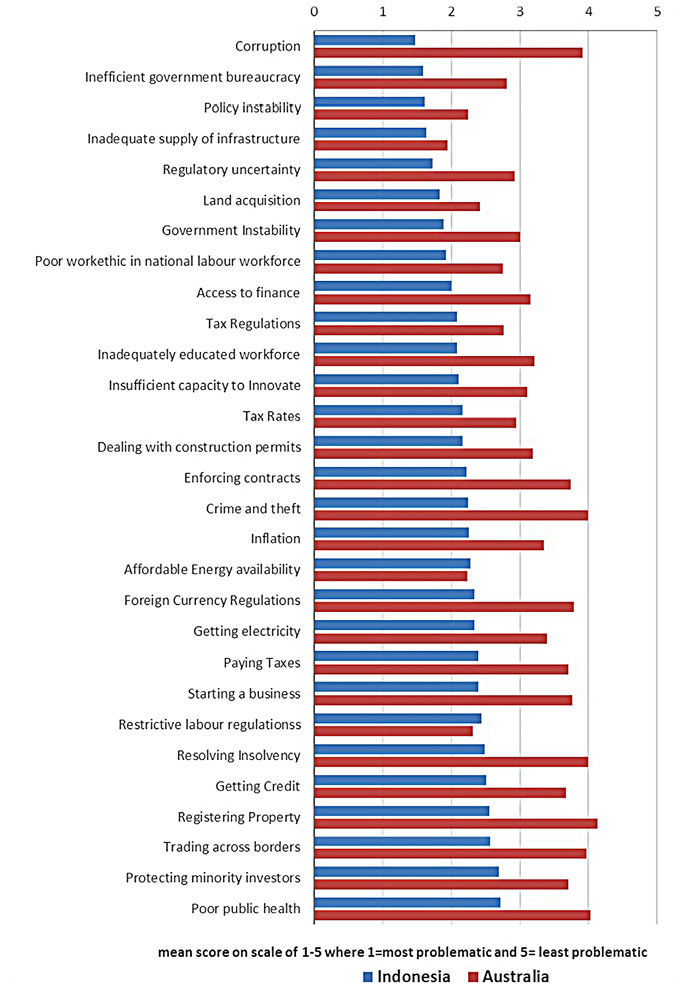

A question related to Investment decisions — Barriers to doing business was incorporated into both the Australian and Indonesian surveys. Twenty-nine factors were listed.

The factors listed in the ‘barriers’ question incorporated:

- The sixteen factors that the World Economic Forum (WEF) uses in their Executive Opinion Survey;

- The ten indicators used by the World Bank (WB); and

- Three additional factors included in the questionnaires: affordable energy availability, land acquisition and regulatory uncertainty which were identified as issues in Indonesia and already highlighted above (KPMG 2015, Smith et al. 2015a) and which were therefore added as potential barriers to doing business. These factors are also of concern and interest in Australia.

Survey participants were asked to indicate on a scale of 1–5 which of the twenty-nine factors listed were most problematic for doing business in their respective countries, when 1 is most problematic and 5 least problematic. Their mean scores are shown in Fig. 2.9. Even though this scoring method was not consistent with how the World Bank determine their “ease of Doing Business” rankings6 and no weighting was applied to the mean scores (as is the case for the WEF Executive Opinion Survey), the responses received to this question gave a valuable perspective from key stakeholders associated with ports in both countries. The results also aligned with concerns reported in the literature and findings from the WEF survey.

Based only on the factors used in the WEF survey, results from the online port planning and development survey show that corruption, inefficient government bureaucracy, policy instability, inadequate supply of infrastructure and government instability were the 5 most problematic for doing business in Indonesia (Fig. 2.9).

In Australia, based on the WEF factors, inadequate supply of infrastructure, policy instability, restrictive labour regulations, poor work ethic in the national labour workforce and tax regulations were the top five most problematic factors for doing business. This is further illustrated in Figs. 2.9 and 2.10.

If we examine all twenty-nine factors ranked, according to how problematic they are, by key port stakeholders in Indonesia and Australia, the most problematic issues identified in this survey for Indonesia were corruption, inefficient government bureaucracy, policy instability, inadequate supply of infrastructure, regulatory uncertainty and land acquisition. In Australia, based on the full twenty-nine factors, inadequate supply of infrastructure, policy instability, affordable energy availability, restrictive labour regulations, and land acquisition were identified as key barriers from the perspective of the port stakeholders surveyed.

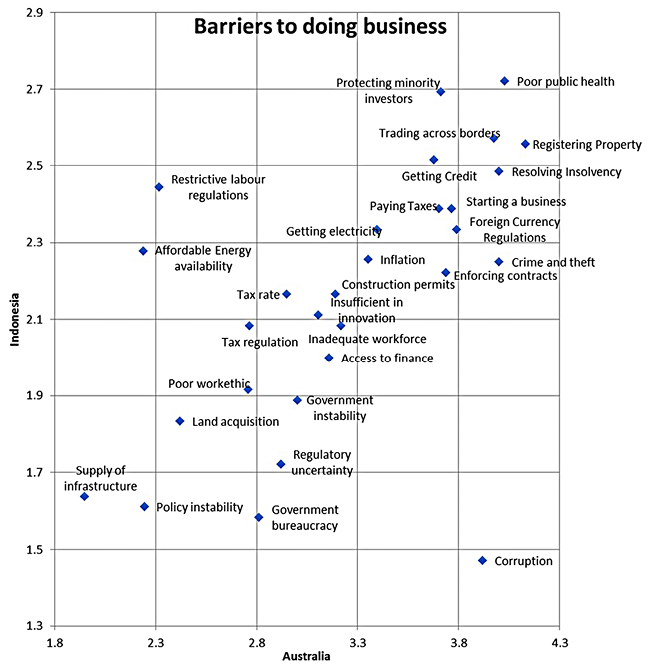

Fig. 2.9 Barriers to doing business in Indonesia and Australia (sorted by mean score — most problematic to least for Indonesia) (Figure by the authors)

Fig. 2.10 Barriers to doing business — a comparison of Indonesia and Australia* (Figure by the authors)

*Lower values correspond to the factor shown being more problematic (1=most problematic, 5=least problematic)

Fig. 2.10 schematically shows the spread of factors, and the degree to which these factors are problematic in Indonesia and Australia. The figure clearly shows that many of the challenges and risks raised earlier in this chapter are relevant to key port stakeholders in Indonesia. Corruption is a much bigger issue from the perspective of respondents from Indonesia than from the perspective of Australian port stakeholders. Policy instability and inadequate supply of infrastructure are considered problematic for both countries.

The next chapter in this research monograph will focus on funding and mechanisms to finance infrastructure investment in Indonesia.

References

APEC 2013. Annex A — An APEC PPP experts advisory panel and pilot PPP centre, paper presented at the APEC Finance Ministerial Meeting, www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Sectoral-Ministerial-Meetings/Finance/2013_finance/annexa

APEC 2014. Annex D — APEC connectivity blueprint for 2015–2025, Leaders’ Declaration, www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Leaders-Declarations/2014/2014_aelm/2014_aelm_annexd.aspx

ASEAN 2010. ‘Master plan on ASEAN connectivity’, ASEAN Secretariat, www.asean.org/storage/images/ASEAN_RTK_2014/4_Master_Plan_on_ASEAN_Connectivity.pdf

ASEAN 2015. ‘ASEAN convenes the sixth connectivity symposium’, ASEAN Secretariat, www.asean.org/asean-convenes-the-sixth-connectivity-symposium

ASEAN 2016. ‘Master plan on ASEAN connectivity 2025’, ASEAN Secretariat, www.asean.org/storage/2016/09/Master-Plan-on-ASEAN-Connectivity-20251.pdf

Asian Development Bank 2012. IMT-GT implementation blueprint 2012–2016, www.adb.org/sites/default/files/page/34235/imt-gt-implementation-blueprint-2012-2016-july-2012.pdf

Asian Development Bank 2015. IMT-GT implementation blueprint 2012–2016 Mid-term Review, www.jpp.moi.go.th/media/files/02_02_59_DOC_8_-_MTR__FINAL_web_4Apr2015_1.pdf

Bappenas (Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency) 2011b. Masterplan for acceleration and expansion of Indonesia economic development 2011–2025, Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs, ASEAN_Indonesia_Master Plan Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011-2025 (3).pdf

Bappenas (Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency) 2011a. Masterplan for acceleration and expansion of Indonesia economic development 2011–2025, Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs, in ASEAN Briefing Dezan Shira and Associates, ASEAN_Indonesia_Master Plan Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011-2025 (9).pdf

Bappenas (Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency) 2015a. Public Private Partnerships (PPP) 2015. Infrastructure projects plan in Indonesia, www.bappenas.go.id/files/1514/4041/0522/ppp_book_2015.pdf

Bappenas (Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency) 2015b. List of planned priority external loans www.bappenas.go.id/files/2814/4524/3464/drppln-2015.pdf

Bappenas (Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency) 2017. Public Private Partnerships. Infrastructure projects plan in Indonesia, www.bappenas.go.id/files/9314/8767/3599/PPP_BOOK_2017.pdf

BKPM (Indonesian Investment Coordinating Board) 2015. About BKPM — Profile of institution, www.bkpm.go.id/en/about-bkpm/profile-of-institution

Bu, X 2015. ‘Maritime Silk Road can bridge China-ASEAN cooperation’, The Jakarta Post, www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/08/05/maritime-silk-road-can-bridge-china-asean-cooperation.html

Centre for Public Impact 2016. Indonesia’s anti-corruption commission: the KPK, Centre for Public Impact, www.centreforpublicimpact.org/case-study/indonesias-anti-corruption-commission-the-kpk/

Dodd, C 2015. ‘Indonesia launches massive port expansion’, FinanceAsia, www.financeasia.com/News/394905,indonesia-launches-massive-port-expansion.aspx

Duffield, CF 2014. Discussion paper for the Australia-Indonesian research centre research summit: infrastructure, Working Paper, The University of Melbourne.

ERIA 2014. PPP country profile. Indonesia, EAIC Advisory-Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), PPP_in_Indonesia_ERIAsummary_March_2014.pdf

Global Business Guide (GBG) Indonesia 2015. Indonesia’s land acquisition laws: On paper only?, www.gbgindonesia.com/en/property/article/2016/indonesia_s_land_acquisition_laws_on_paper_only_11365.php>

Government of the Republic of Indonesia and United Nations in Indonesia 2015. Government-United Nations Partnership for Development Framework (UNPDF) 2016–2020: Fostering sustainable and inclusive development, Republic of Indonesia and The United Nations System in Indonesia, pp. 1–60, www.unicef.org/about/execboard/files/Indonesia-UNPDF_2016_-_2020_final.pdf

Gustely, E 2015. ‘How do foreign investors perceive opportunities in Indonesian infrastructure?’, Journal of the Indonesia Infrastructure Initiative Prakarsa, 22, October, pp. 4–6.

Hutapea, TP 2015. Overview of Indonesia’s infrastructure landscape, presentation at Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM), www.iesingapore.gov.sg/~/media/IE%20Singapore/Files/ASIR/Workshop1_Tamba_Hutapea.pdf

Indonesian Investments. ‘General political outline of Indonesia’, Indonesia Investments, https://www.indonesia-investments.com/culture/politics/general-political-outline/item385

Indonesian Investments 2016. ‘Infrastructure development in Indonesia’, Indonesia Investments, www.indonesia-investments.com/business/risks/infrastructure/item381

Indonesian Investments 2017. ‘Corruption in Indonesia’, Indonesia Investments, www.indonesia-investments.com/business/risks/corruption/item235>

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2015. World economic outlook database, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/weodata/weoselgr.aspx

Kementerian PPN/Bappenas 2016a. Revised list of planned priority external loans (DRPPLN) 2016 Green Book, www.bappenas.go.id/id/data-dan-informasi-utama/publikasi/drpln-jm-dan-drpphln/

Kementerian PPN/Bappenas 2016b. Blue Book (DRPLN-JM) 2015–2019. List of medium-term planned external loans 2015–2019 Book 1 and 2, 2016 Revision., www.bappenas.go.id/id/data-dan-informasi-utama/publikasi/drpln-jm-dan-drpphln/

Kementerian PPN/Bappenas 2017. Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional/Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional, www.bappenas.go.id/en/profil-bappenas/sejarah/

KPPIP 2016. About KPPIP, Komite Percepatan Penyediaan Infrastruktur Prioritas (Committee for Accelleration of Priority Infrastructure Delivery), www.kppip.go.id/en/about-kppip/

KP3EI 2012a. MP3EI — Background, www.kp3ei.go.id/en/main/content2/69/68

KP3EI 2012b. MP3EI — Main Strategy,www.kp3ei.go.id/en/main/content2/69/83

KPMG Indonesia 2015. Investing in Indonesia — 2015, www.assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/07/id-ksa-investing-in-indonesia-2015.pdf

Lee, J 2015. ‘Indonesia’s road infrastructure: Accelerating the private sector contribution’, Journal of the Indonesia Infrastructure Initiative: Prakarsa, 22, pp. 22–7.

Lin DY, 2014. Can public private partnerships solve Indonesia’s infrastructure needs?, McKinsey and Company, www.mckinsey.com/indonesia/our-insights/can-ppps-solve-indonesias-infrastructure-needs

OECD 2016. OECD Economic surveys: Indonesia, OECD Publishing, www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/indonesia-2016-OECD-economic-survey-overview-english.pdf

Oxford Business Group 2014. The report: Indonesia 2014, www.oxford businessgroup.com/indonesia-2014

Parikesit, D and Laksmi, IN 2015. Research report. Critical review of Indonesia PPP regulations and frameworks. Challenges and ways forward, 1st ed, PT Penjaminan Infrastruktur Indonesia (Persero), www.iigf.co.id/institute/media/kcfinder/docs/iigf-ppp-regulatory-frameworks.pdf

Piesse, M 2015. Strategic analysis paper: The Indonesian maritime doctrine: Realising the potential of the ocean, Future Directions International, www.futuredirections.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/FDI_Strategic_Analysis_Paper_-_The_Indonesian_Maritime_Doctrine.pdf

Priatna, I D S 2014. Workshop on the establishment of an Indonesia institute for infrastructure development effectiveness, presentation at BAPPENAS.

Priyambodo, RH 2015. ‘President Jokowi wants synergy in fight corruption’, Antara News, www.antaranews.com/en/news/99005/president-jokowi-wants-synergy-in-fight-corruption

Salas, A 2018. ‘Slow, imperfect progress across Asia Pacific’, Transparency, www.transparency.org/news/feature/slow_imperfect_progress_across_asia_pacific

Sambhi, N 2015. ‘Jokowi’s ‘Global maritime axis’: Smooth sailing or rocky seas ahead?’, Security Challenges, 11:2, pp. 39–55.

San Andres, EA 2015. APEC connectivity blueprint: Objectives, targets, and strategies. National Seminar on Integrated Intermodal Transport Connectivity, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Session%204%20APEC%20Connectivity%20Blueprint.pdf

Schwab, K 2016. The global competitiveness report 2016–2017, World Economic Forum, www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2016-2017/05FullReport/TheGlobal CompetitivenessReport2016-2017_FINAL.pdf

Schwab, K 2017. The global competitiveness report 2017–2018, World Economic Forum, www.cdn.indonesia-investments.com/documents/Global-Competitiveness-Report-2017-2018-Indonesia-Investments.pdf

Shekhar, V and Liow, JC 2014. ‘Indonesia as a maritime power: Jokowi’s vision, strategies, and obstacles ahead’, The Brookings Institution, www.brookings.edu/articles/indonesia-as-a-maritime-power-jokowis-vision-strategies-and-obstacles-ahead/

Sipahutar, T 2014. ‘Govt claims MP3EI progress, financing remains a key issue’, The Jakarta Post, www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/09/05/govt-claims-mp3ei-progress-financing-remains-a-key-issue.html

Sipahutar, T 2015. ‘Fiscal reform continues with capex boost’, The Jakarta Post, www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/12/11/fiscal-reform-continues-with-capex-boost.html

Smith, J, Satar, R, Boothman, T and Harrison, G 2015a. Building Indonesia’s future: Unblocking the pipeline of infrastructure projects, PwC, www.pwc.com/id/en/capital-projects-infrastructure/Building%20Indonesia’s%20future.pdf

Smith, J, et al. 2016. Indonesian infrastructure: Stable foundations for growth, PwC, www.pwc.com.au/publications/asia-practice-indonesian-infrastructure-stable-foundations-for-growth.html

Smith, J, Wiryawan, A, Irawan, M, and Ray, D, 2018. Public Private Partnerships, PwC, www.pwc.com/id/en/industry-sectors/cpi/public-private-partnerships.html

Strategic Asia 2012. ‘Implementing Indonesia’s economic master plan (MP3EI): Challenges, limitations and corridor specific differences’, presentation available at www.scribd.com/document/129770011/Implementing-the-MP3EI-Paper-pdf

Szechenyi N (ed.) 2018. China’s Maritime Silk Road. Strategic and economic implications for the Indo-Pacific region, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, www.csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/180404_Szechenyi_ChinaMaritimeSilkRoad.pdf?yZSpudmFyARwcHuJnNx3metxXnEksVX3

Sukaesih, M 2014. ‘Analysis: Alternative sources of funding for infrastructure development’, The Jakarta Post, p. 14, www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/09/24/analysis-alternative-sources-funding-infrastructure-development.html

Transparency International 2014. Corruption Perceptions Index 2014: Results, www.transparency.org/cpi2014/results

World Bank 2018. Doing business 2018: Indonesia, World Bank Group, www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/i/indonesia/IDN.pdf

World Economic Forum 2015. The global competitiveness report 2015–2016 Country profiles — Indonesia, http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-report-2015-2016/economies/#economy=IDN

1 Professor of Engineering Project Management, Deputy Head of Department (Academic), Dept. of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne.

2 Research Assistant, Dept. of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne.

3 Research Fellow, Dept. of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne.

4 The development themes for the six economic corridors identified are: Sumatra EC-centre for production and processing of natural resources as nation’s energy reserves; Java-driver for national industry and service provision; Kalimantan-centre for production and processing of national mining and energy reserves; Sulawesi-centre for production and processing of national agricultural, plantation, fishery, oil and gas and mining; Bali-Nusa Tenggara gateway for tourism and national food support; Papua-Kepulauan Maluku centre for development of food, fisheries, energy, and national mining.

5 The distance to frontier (DTF) measure shows the distance of each economy to the “frontier,” which represents the best performance observed on each of the indicators across all economies in the Doing Business sample since 2005. An economy’s distance to frontier is reflected on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 represents the lowest performance and 100 represents the frontier. The ease of doing business ranking ranges from 1 to 190.

6 The World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index covers 11 areas of business regulation across 190 economies although only 11 areas are reported in rankings and DTF score. Results are based on standardised case scenarios and usually located in the largest business city of each economy.