4. Efficient Facilitation of Major Infrastructure Projects

© C. F. Duffield, F. K. P. Hui, and V. Behal, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0189.04

4.0 Background and Context

Indonesia is currently experiencing a “major infrastructure deficit” brought on by decades of neglect and poor asset management (Ray and Ing 2016; Barker, 2017). Although the Government of Indonesia (GoI) is working towards a reform by diverting the focus of the state budget to this area, a substantial amount of private investment is necessary to fill the gap in funding that is required to meet the targets of efficiency in infrastructure (Ray and Ing 2016). It seems that the GoI has devised a plan to overcome this issue through privatisation of existing State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and delivering funds from the state budget to them to realise their goals of infrastructure development (Abednego and Ogunlana 2006). In addition to this, Atmo, Duffield and Wilson (2015) suggest that whilst local investment from private entities may substantially contribute to some of the smaller projects, the larger infrastructure projects that are vital for national social and economic growth require a considerable amount of investment that may only be provided by foreign parties. Moreover, the current system for risk allocation and lack of transparency in the system have managed to deter foreign investors from Public Private Partnership (PPP) schemes in Indonesia (Atmo et al. 2015; Ray and Ing 2016; Olken 2007; Abednego and Ogunlana 2006). Risks of extensive delays in the project’s implementation timelines and the government’s tendency to be “stronger on announcements than implementation” have led to the cautious response from foreign markets despite the various reforms in regulation that have been brought upon by the Jokowi government (Ray and Ing 2016, p. 2; Manning 2015).

Whilst several writers have attributed a lack of quality infrastructure as the primary contributor towards a decrease in economic and social development (Negara 2016; Barker 2017); Sandee (2016) highlights the importance of soft issues such as regulations and policy coordination in addition to the hard issues like infrastructure for the economic and social development of a nation, and Basri (2016) validates this point. Furthermore, Flyvbjer (2005) discusses the need for reform in policy regulations and planning for large infrastructure projects. This specifically focuses on the issues of misrepresentation of data to win stakeholder support, as well as the issues with cost estimations and planning that lead to the overall cost of project exceeding the projected costs by a large sum, contributing to a lack of trust between the parties, and hence a lower likelihood of future investment (Flyvbjerg 2005).

The Jokowi government has recently been working to overcome these issues in their release of ten new economic policy packages, released between the period of September 2015 to February 2016, in an attempt to support investment in key areas of focus, infrastructure being one of them (Manning 2015; Ray and Ing 2016). Nevertheless, the President’s attempt to attract and welcome foreign investors to Indonesia has been met with scepticism on whether the new policy packages will deliver (Ray and Ing 2016). Several occurrences in the past, where the projects have been bottlenecked due to systematic errors, not only serve as a deterring factor for future foreign investors, the unclear boundaries on risk allocation, opaqueness within the system and the lack of state support to carry out the implementation seem to have established a reputation for Indonesia (Pangeran et al. 2012).

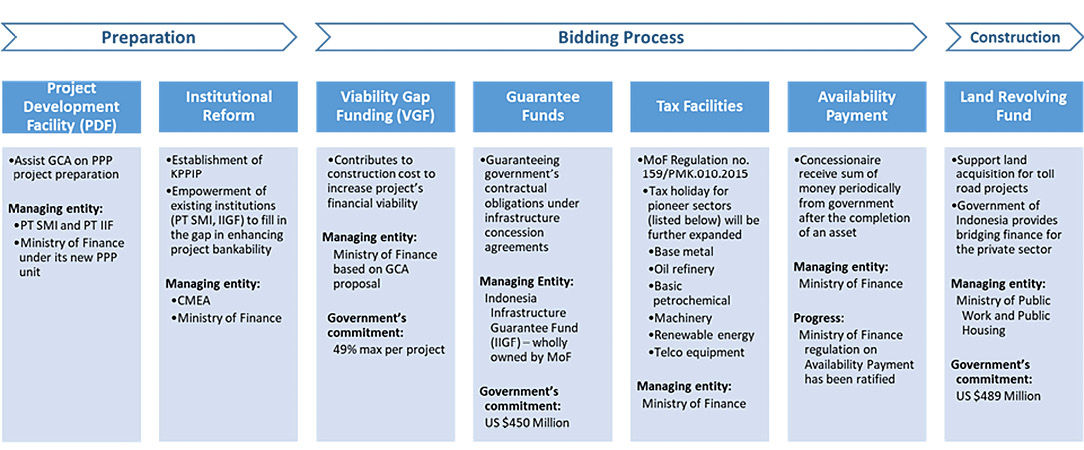

Foreign investment in Indonesian infrastructure is imperative to improve its attractiveness, stability and functionality for other trades, making Public Private Partnerships (PPP) a viable option for procurement of infrastructure projects (Pangeran et al. 2012). Taking into account, the current failures in the system, the Jokowi government has established a web of supporting government organisations to support the investors and planners in implementation of PPP infrastructure projects through the various stages in the process for procurement (Haryanto 2015), (Ray and Ing 2016); this has been summarised in Fig. 4.1 Project support system. This Figure also highlights the several changes in the Presidential Regulations that have been made to support the implementation process through each stage, addressing the various factors that have acted to deter foreign investors in this area (Haryanto 2015). Furthermore, Committee for Acceleration of Priority Infrastructure Delivery (KPPIP) has been created as a government organisation to review the progress of priority infrastructure projects in Indonesia and accelerate their delivery (KPPIP 2016; Haryanto 2015).

Fig. 4.1 Project support system (Figure by the authors based on data. Source: Haryanto 2015)

Other notable regulatory reforms include the establishment of the Indonesian Infrastructure Guarantee Fund (IIGF), supported by the World Bank, that provides a government guarantee for political and legal risks pertaining to the project (Ministry of Finance 2012) and (Atmo et al. 2015). Not only does this increase the investor’s confidence in the system by increasing the government’s accountability towards the project; the establishment of the IIGF also encourages transparency in the system, hence increasing the chances of the project’s successful implementation (Atmo et al. 2015). In addition to this, PPP institutions have also been set up and clear guidelines on the PPP implementation process have been established to maximise the benefits for potential future PPP partnerships (Indra 2011).

This chapter looks at the processes involved in implementation of major infrastructure projects. It identifies the theoretical processes to instigate projects and compares them to the real-world practices that are being implemented in Indonesia and Australia by looking at case study examples. This chapter primarily focuses on PPP procurement of projects, although projects using other procurement strategies may be used as case examples.

4.1 Risk Allocation and Management

Private investment is necessary to overcome the financial obstacles in procurement of infrastructure projects in Indonesia (Duffield et al. unpublished). Whilst PPP arrangements are a viable option for attracting private investment in infrastructure projects (Pangeran et al. 2012; Atmo et al. 2015), there are several risks associated with such schemes, especially when international parties are involved (Pangeran et al. 2012). The large capital investment requirements and the lack of flexibility in contractual agreements increase the level of risk involved with the project, making effective risk management and a clear system of risk allocation critical factors for the overall project success (Dixon, Pottinger and Jordan 2005; Hardcastle, Edwards, Akintoye and Li 2005; Pangeran et al. 2012; Abednego and Ogunlana 2006). However, as Abednego and Ogunlana (2006) clearly highlight, different perspectives may exist on proper risk allocation between parties in PPP schemes, often creating conflict that must be managed through effective project management to ensure successful project implementation.

In addition to this, Pangeran et al. (2012) emphasises the importance of correct risk identification and management as there is a danger in underestimation of risks and their allocation to parties that do not have the necessary expertise or resources to manage them to the level of adequacy required. Furthermore, the quality of the decision-making process throughout the development of the project is also reliant on an effective risk management system (Dixon et al. 2005; Li et al. 2005); providing an overall benefit to the project in the following ways, as highlighted in the Public Private Partnerships report by the Department of Finance and Administration, Australian Government (2006):

- Improving the project’s performance by early risk identification.

- Improving the planning process by taking the risks into account.

- Supporting robust decision making.

Furthermore, inadequate risk assessment and management has the potential to result in increased project costs, substantial delays in project delivery and an inability to achieve the full potential of benefits received from the project’s implementation (Ng and Loosemore 2006; Dixon et al. 2005). Additionally, it must be acknowledged that risk management must continue from the project planning, through to the execution and construction stages, as stated by Pangeran et al. (2012). The exposure to risk for the private entity throughout the project’s lifetime has been addressed by the Presidential Regulation 67/2005 that was later amended by Presidential Regulation 13/2010, Presidential Regulation 78/2010 (Indra 2011; Atmo et al. 2015; Ministry of Finance 2012). These address the provision of government support and guarantees to the private entity engaged in a PPP agreement to effectively reduce the risks that the investors may be exposed to throughout the planning and implementation stages of the project (Ministry of Finance 2012).

4.2 Delivery of Infrastructure Projects: Indonesia

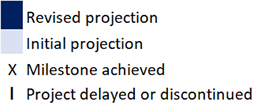

Several case studies have been analysed to identify the factors which cause delays in major project implementation. The projected schedule dates for major processes for these projects have been researched and summarised using Gantt charts shown in this section. The scheduled dates and expected timelines have been sourced from media releases and the government department report published for priority infrastructure projects (KPPIP 2016). The legend used for these charts is shown in Fig. 4.2 Legend used for project schedule charts below.

Fig. 4.2 Legend used for project schedule charts (Figure by the authors)

The following cases have been studied for this study:

- Jakarta Sewerage System.

- West Semarang Drinking Water Supply System.

- National Capital Integrated Coastal Development Phase A.

- Bontang Oil Refinery.

- Umbulan Springs Water Supply Project.

The location of these case studies has been overlaid on the map shown below.

Fig. 4.3 Case study locations (map source: Amin (2015))

4.2.1 Jakarta Sewerage System (JSS)

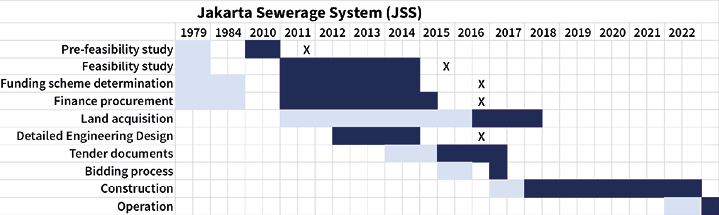

The project to improve Jakarta’s Sewerage System has been ongoing since it was first initiated in the early 1970s (Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) 2012). However, due to funding constraints and a lack of knowledge and expertise in this area, only a pilot phase of this project was delivered in 1991 (The World Bank 2017). Further phases have been initiated several times but failed to deliver due to a lack of funding availability (Smith, Wiryawan and Ray 2017). Table 4.1 Jakarta Sewerage System summarises the key aspects of this project and Fig. 4.4 shows the project implementation timeline for the various processes in this project.

Table 4.1 Jakarta Sewerage System

Project owner | Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta |

Location | DKI Jakarta |

Investment value (Zone 1) | IDR 8 trillion |

Funding scheme | Potential for state budget with foreign loan (Japan) for Zone 1, funding scheme for other zones is yet to be determined, potential for Public Private Partnership (PPP) |

Construction commencement (Zone 1) | 2018 |

Commercial Operation (Zone 1) | 2021 |

DKI Jakarta is now ranked as the second lowest capital city in South East Asia for sanitation, with the current coverage ratio only being 4% of the total area (Basu 2016; KPPIP 2016). The city is the Indonesian capital for government, business and industry; however, the quality of water and sanitation has worsened over the years despite the recent development of the city (KPPIP 2016).

This project is especially necessary for effective implementation of the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development project, listing the Jakarta Sewerage System project as a priority project for implementation (KPPIP 2016).

Fig. 4.4 highlights the major delays in completion of the processes involved with this project. The expected date projections for the processes seem to not have been met and the project is currently experiencing extensive delays due to issues associated with land acquisition.

Fig. 4.4 Jakarta Sewerage System project implementation schedule (Figure by the authors)

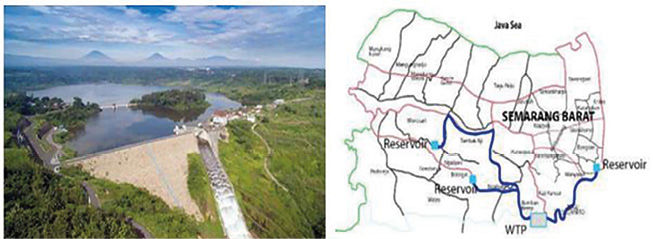

4.2.2 West Semarang Drinking Water Supply

The West Semarang Drinking Water Supply (SPAM) project is expected to resolve the current shortage of raw drinking water supply in Semarang (KPPIP 2016). There are currently over 60,000 families in thirty-one sub-districts that have no access to drinking water (Puspa 2016). Table 4.2 West Semarang Drinking Water Supply summarises the key information for this project; Fig. 4.5 shows the coverage area and location of the SPAM for this project. This project is expected to supply these families with water and aid in reduction of ground water usage, which is currently being extracted to extreme levels (Puspa 2016; KPPIP 2016).

Table 4.2 West Semarang Drinking Water Supply

Project owner | Municipal Government of Semarang |

Location | Semarang, Central Java |

Investment value | IDR 1,170 billion |

Funding | State Budget (APBN), Local government budget (APBD) and Tirta Moedal PDAM of Semarang City |

Construction commencement (planned) | 2018 |

Commercial Operation | 2022 |

Fig. 4.5 West Semarang SPAM (left), supply map (right) (image source: Amin (2015)).

Viability Gap Funding (VGF) has been approved for this project in 2015, assisting prospective private investors to meet funding requirements (Investor Daily 2015). A Public Private Partnership (PPP) scheme was initially proposed for this; however, it was revised when a change in direction was recommended by the Vice President (Sulistyoningrum 2016). This was to revise the funding option from a PPP to a State Owned Enterprise (SOE) to accelerate the implementation of this project.

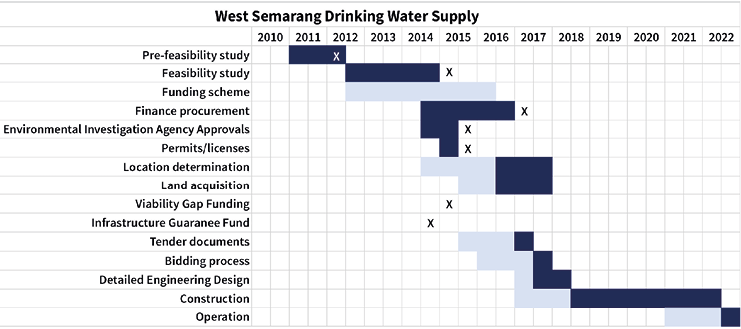

Recent developments include division of the project funding to three sources: State Budget (APBN), Local Government Budget (APBD) and Tirta Moedal PDAM of Semarang City (Puspa 2016). The project was initially expected to commence construction in July 2015; however, funding availability and land acquisition have been a source of delay to its implementation (Investor Daily 2015). Although the funding has now been finalised, the land issue has been deemed to be ‘complicated’ and the project is awaiting land acquisition. If land is finalised within 2017, the construction may commence in 2018 (Puspa 2016). However, this seems unlikely at this stage, judging by the current progress. Fig. 4.6 West Semarang Drinking Water Supply project implementation schedule shows the timeline for its implementation.

Fig. 4.6 West Semarang Drinking Water Supply project implementation schedule (Figure by the authors)

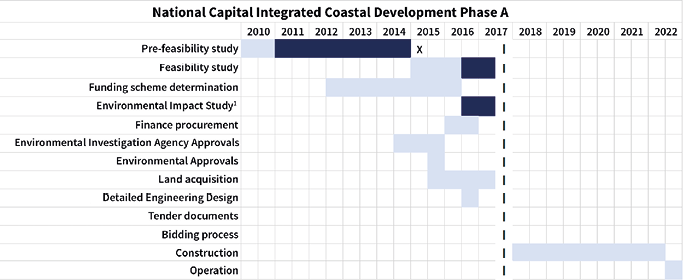

4.2.3 National Capital Integrated Coastal Development

More than 50% of Jakarta’s population currently lives in the coastal area, with a significant proportion of the city’s economic activities taking place here (KPPIP 2016). Jakarta is home to thirteen rivers and 40% of the city’s coastal low land area is lower than the tidal surface (KPPIP 2016). Furthermore, excessive ground water extraction due to drinking water supply shortage has led to land subsidence, exacerbating the impact of floods (Sherwell 2016). This makes National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) project necessary for long-term sustainability of the area. Table 4.3 highlights some of the key information for this project.

Table 4.3 National Capital Integrated Coastal Development

Project owner | Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta, Ministry of Public Works and Public Housing (MOPWandPH) |

Location | DKI Jakarta |

Investment value | IDR 26 trillion (Phase A), IDR 600 trillion (all phases) |

Funding scheme | State and Regional budget (Phase A), potential for PPP for other phases |

Construction commencement (planned) | 2016 (initial plan) |

Commercial Operation | 2018 (initial plan) |

There are three phases to the completion of this project (KPPIP 2016):

- Improving the existing coastal protection

- Further development of the west outer giant seawall to be constructed 2018–2022

- Construction of the east outer giant seawall (planned for after 2023)

The NCICD is supported by the Royal Dutch Embassy with the total investment amounting up to USD 40 billion (Sherwell 2016). However, the project was halted in December 2016 due to stakeholder concerns of the immediate negative impact of this project on the livelihood and welfare of the Jakarta Bay residents (Transnational Institute 2016). Interference from local groups had initially led to halting of the project to conduct further environmental impact studies and discussions with the local groups to come to a sustainable solution to solve the water problems for the residents of Jakarta Bay (Transnational Institute 2016). Some key information regarding the project has been highlighted in Table 4.3 National Capital Integrated Coastal Development, while Fig. 4.7 National Capital Integrated Coastal Development project implementation schedule gives timeline projections of the implementation process.

Fig. 4.7 National Capital Integrated Coastal Development project implementation schedule (Figure by the authors)

In July 2017, it was announced that this project will be terminated and the Indonesian capital will be relocated, as reported in the Jakarta Post (2017).

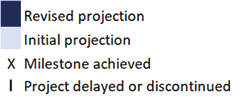

4.2.4 Bontang Refinery

The Bontang Refinery construction project, located in East Kalimantan, aims to produce 235,000 barrels of oil per day to satisfy the domestic demand for fuel. Some of the key information for this project, as sourced from the report for priority infrastructure projects, has been summarised in Table 4.4 Bontang Oil Refinery. Indonesia’s increasing need for fuel and vision to achieve energy security require a significant growth in the domestic refinery industry, as will be facilitated by several refinery projects that are currently in the pipeline for implementation (KPPIP 2016).

Table 4.4 Bontang Oil Refinery

|

Project owner |

PT Pertamina (awaiting determination) |

|

Location |

Bontang, East Kalimantan |

|

Investment value |

IDR 75–140 trillion |

|

Funding scheme |

Potential for PPP scheme (awaiting determination) |

|

Construction commencement (planned) |

2018 |

|

Commercial Operation |

2022 |

The Bontang Refinery project has attracted the interest of several foreign investors and global refinery companies were invited to participate in the tender process in February 2017, with the business partners expected to be named by April 2017 (Tempo.co 2017). However, no alliances have yet been announced, as of October 2017.

Although the KPPIP report (2016) did not expect any significant issues with its timeline due to land already being allocated and the presence of supporting infrastructure (road access, jetty, etc), the project has recently been met with major delays due to issues with the financial capacity of the project’s major shareholder, PT Pertamina (Singgih 2017). Whilst the ground-breaking for this project was previously projected to begin in 2017 (Indonesia Investments 2016); it was later revised to 2019 due to low interest from foreign investors (Asmarini and Tan 2017). The projected operational date for the project has recently been revised to 2025 due to Pertamina’s financial obligations (Singgih 2017). Fig. 4.8 Bontang Oil Refinery project implementation schedule aims to illustrate some of these date projections and the project’s process timeline.

Fig. 4.8 Bontang Oil Refinery project implementation schedule (Figure by the authors)

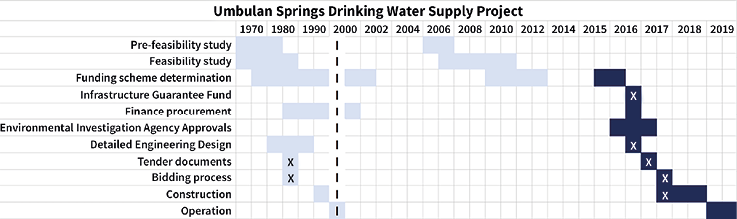

4.2.5 Umbulan Springs Drinking Water Supply Project

The Umbulan Springs Drinking Water Supply (SPAM) project has been in the planning stage since 1973 (Syarizka 2016), making it well over forty years before the construction was able to recently begin in July 2017 (PwC 2017). Table 4.5 Umbulan Springs Drinking Water Supply Project summarises the key information for this project and Fig. 4.9 shows an approximate timeline of the processes involved in the implementation of this project.

Table 4.5 Umbulan Springs Drinking Water Supply Project

|

Project owner |

PT Medco Energi Internasional, Tbk. and PT Bangun Cipta Kontraktor |

|

Location |

East Java Province |

|

Investment value |

IDR 2050 Billion |

|

Funding scheme |

Public Private Partnership (PPP) |

|

Construction commencement (planned) |

2017 |

|

Commercial Operation |

2019 |

Fig. 4.9 Umbulan Springs project implementation schedule (Figure by the authors)

This is the first regional water supply project that will be implemented under a Public Private Partnership (PPP), managed by the central and regional governments (Susanty 2016). After experiencing extensive delays for over forty years, the Infrastructure Guarantee Funding (IGF) was allocated in 2006 as a risk sharing mechanism for this project (Susanty 2016). This, along with the government subsidy Viability Gap Funding (VGF), has led to an increase in its bankability for private investors, attracting them to invest in the Umbulan Springs Drinking Water Supply project (Syarizka 2016).

The bidder for this project was chosen in 1989; however, negotiations between the GoI and the selected bidder failed when it was determined that no guarantee funding would be allocated to the project, leading to a termination of the contract (Chemonics International, Resource Management International, Sheladia Associates 1994). Recently, the government support of the project with the Infrastructure Guarantee Fund has worked as a risk sharing mechanism, attracting the private investors to carry out this project.

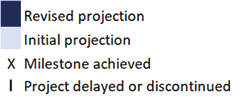

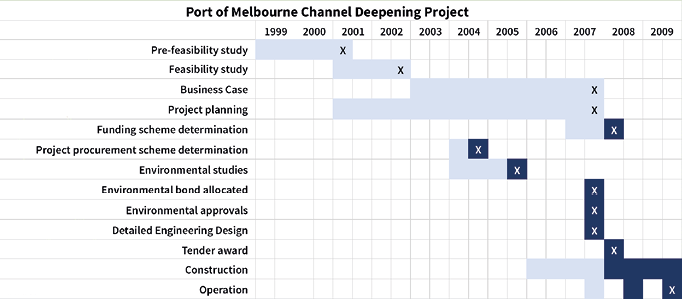

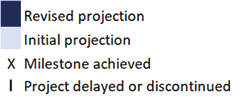

4.3 Delivery of Infrastructure Projects: Australia

This chapter looks at two case studies from Australia: the Channel Deepening Project for the Port of Melbourne in Victoria; and the M7 Motorway in Sydney, New South Wales. The Australian cases have been analysed similarly to the Indonesian case study analysis earlier in this chapter. Official reports, news and media releases were closely followed to be able to draw a Gantt chart of the Australian case studies to show their projected timelines and the processes implemented for a successful project commencement.

4.3.1 Channel Deepening Project, Victoria

The Channel Deepening Project for the Port of Melbourne in Victoria involved dredging into the Port Phillip Bay, removing approximately twenty-two million cubic metres of sand and silt, to enable passage of the larger shipping vessels into the port (Department of Infrastructure and Transport 2010). Moreover, dredging is necessary to avoid Melbourne from becoming a backwater and limiting further access to the shipping vessels (Millar 2008). The Table below summarises the key features of this project.

Table 4.6 Channel Deepening Project, Victoria

|

Project owner |

Port of Melbourne |

|

Location |

Port Phillip Bay |

|

Investment value |

AUD 969 million |

|

Procurement scheme |

Alliance |

|

Construction commencement (planned) |

2008 |

|

Commercial Operation |

2010 |

Source: Department of Infrastructure and Transport (2010).

The Channel Deepening Project was announced in 2000. Thereafter, the project development and planning took more than six years (Department of Infrastructure and Transport 2010). The economic viability and the environmental safety were thoroughly investigated to ensure limited impact on the surrounding economy and ecology. The overall project was completed on time and within budget of AUD 969 million under an Alliance contract.

The project has involved some of the most stringent environmental requirements to date, including 150 environmental control measures and 60 project delivery standards (Department of Infrastructure and Transport 2010). These were continuously monitored during the timeline of the project’s implementation and after beginning the commercial operation by independent experts (Cooke 2007). These are a result of extensive environmental impact studies and community protests against the dredging activities due to possible social and environmental impacts (unknown author 2008; Lucas 2007). Furthermore, as a risk contingency program, an environmental protection bond has been paid to the government by the Port of Melbourne (Lucas and Murphy 2007). Some delays were experienced in the final stages of the project due to stakeholder action in the form of public protests.

Fig. 4.10 Channel Deepening Project implementation schedule outlines the timeline for the implementation processes of this project. This figure shows the projected durations for each of the processes in the shadings, with the lighter colour signifying the earliest projections and the darker shading highlights any changes that may have been made to these projections as a result of circumstances surrounding the project. The dates when the processes were finally completed have been marked by the ‘X’. Overall, the Port of Melbourne’s projected dates seem to have been met successfully with the project reaching operation stage within time and budget constraints.

Fig. 4.10 Channel Deepening Project implementation schedule (Figure by the authors)

4.3.2 M7 Motorway, New South Wales

The M7 Motorway is a substantial part of the New South Wales (NSW) government’s orbital strategy to dramatically reduce travel time across western Sydney (Roads and Maritime Services 2015). The motorway spans 40 km and consists of four lanes. It has reduced approximately 60,000 vehicles per day from the existing western Sydney road network, reducing the congestion and delays in this area.

Table 4.7 below summarises the key attributes of the project.

Table 4.7 M7 Motorway, New South Wales

|

Project owner |

NSW Roads and Traffic Authority (RTA) |

|

Location |

Sydney, New South Wales |

|

Investment value |

AUD 1.65 billion |

|

Procurement scheme |

PPP |

|

Construction commencement (planned) |

February 2003 |

|

Commercial Operation |

December 2005 |

The initial concept for this project was introduced in the 1960s by the NSW Department of Main Roads (Department of Infrastructure and Transport 2010). The Sydney Area Transportation Study in 1974 suggested the need for the highway and a possible corridor for this route to address the future residential and industrial growth areas. A Build Own Operate Transfer (BOOT) Public Private Partnership was selected as the procurement model to accelerate the delivery of this project. Benchmark practices, as outlined by the Gateway Review Process were followed in the implementation of this project.

This motorway project had invited the largest private funding of AUD 2.23 billion into public infrastructure with only AUD 360 million being provided by the federal government to support the replacement of the Cumberland Highway in the National Highway Network (Department of Infrastructure and Transport 2010). Furthermore, the preliminary design and the features of the motorway invited community consultation to ensure their cooperation and satisfaction with the new motorway. In fact, some changes to the route were made as a result of this to minimise the environmental impact of the new motorway. In addition to this, all levels of the government (local, state and federal) were engaged throughout the duration of the project to ensure their cooperation and a high level of stakeholder management. This has proven to be beneficial for the project in the long term, ensuring that it meets the needs and expectations of stakeholders.

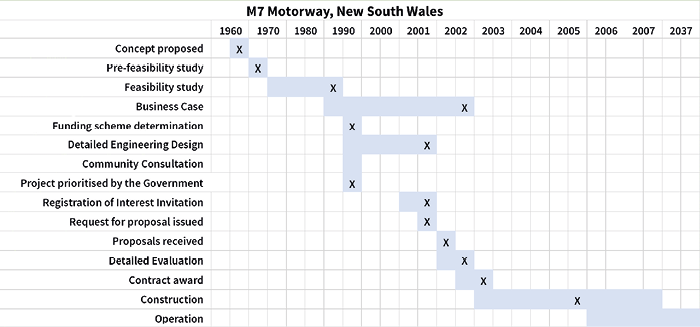

Fig. 4.11 M7 Motorway project implementation schedule outlines the timeline for the implementation processes of this project. This figure shows the projected durations for each of the processes in the shadings. The dates when the processes were finally completed have been marked by the ‘X’. Overall, the projected dates seem to have been met successfully with the project completing construction well before the required date set in 2007. This may be attributed to the PPP procurement model that incentivises early completion (Department of Infrastructure and Transport 2010).

Fig. 4.11 M7 Motorway project implementation schedule (Figure by the authors based on Department of Treasury and Finance n.d.)

4.4 Benchmark Practices

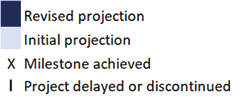

Fig. 4.12 Gateway Review Process (left) in comparison to Indonesian case studies (right) shows the benchmark process for implementation of major infrastructure projects in Australia, the Gateway Review System. This system requires a thorough review to be conducted at each of the major milestones in the implementation of projects that are classified as high value, high risk (HVHR) projects (Department of Treasury and Finance n.d.). Projects may be assigned to be a high value, high risk project if they have a value greater than AUD 5 million or may be vulnerable to a significant risk.

Fig. 4.12 Gateway Review Process (left) in comparison to Indonesian case studies (right) highlights the points at which the review is undertaken and the processes that may need to be completed in the lead up to the review of a typical project. The review is conducted by a panel of field experts that are independent to the project owner, service provider and the government.

Fig. 4.12 Gateway Review Process (left) in comparison to Indonesian case studies (right) (Figure by the authors based on Department of Treasury and Finance, n.d.)

This system aims to identify any errors with the business case or in other stages of the project as they occur to mitigate their effect on the project’s value and the timeline of the project’s implementation. Strengthening the business case through an external review system in its early stages may potentially be value-adding over the entire lifecycle of the project.

4.4.1 Comparative Analysis

The case studies discussed in this chapter show a comparison of high value, high risk infrastructure project implementation in Australia and Indonesia. A common trend gathered from these is that a delay or an interruption during a project’s initial stages often leads to extensive delays or interruptions to its overall completion. Inadequate pre-feasibility studies, poor stakeholder management, policy or regulation bottlenecks and financial constraints are the key underlying factors that lead to these delays.

Over the time that it takes for a project to be implemented, the needs of the public magnify and modify. This is especially true for the Umbulan Springs, where it was initially announced in the 1960s and was in its planning stage since 1973; it is now projected to be delivered by 2019. By the time it is delivered, the needs of the residents would have multiplied due to population growth and climate change. Therefore, even after the project will be delivered, the capacity of the system will still not be adequate to meet its needs. Furthermore, the overall quality of the infrastructure, which has been attributed as an important factor for social and economic growth, would not have improved to the level expected as a result of this project. Jakarta Sewage System is a similar project that was expected to have been completed based on its initial pre-feasibility studies in 1979; however, these feasibility studies were again undertaken in 2010 and the project was expected to be delivered by 2021.

For infrastructure development to result in a nation’s social and economic growth, it must meet the pre-defined needs. However, needs change over time and projects must be delivered as early as possible (within time constraints) to ensure the needs are still relevant.

Furthermore, since a project does not begin to deliver on its value until it is implemented, and since the financial costs of a project increase for each unit of time it is delayed or stagnant, any delay in the project can cause a significant financial dent to its overall budget. As so many projects in Indonesia and Australia are already competing for financial support and funding allocation, it is imperative that each project is delivered on time and within budget. This can lead to more projects being supported for implementation, over time leading to an overall increase in the quality of infrastructure and therefore, social and economic growth.

One of the key differences between Australia and Indonesia in terms of large infrastructure project implementation is forecasting and incorporating future needs in the initial stages of the project. The M7 Motorway in New South Wales is a prime example where the pre-feasibility studies began in 1966, and finally delivered decades later, much like the Umbulan Springs Project in Indonesia. A key point of difference between these is that the M7 Motorway project was developed based on predictions of population growth along that corridor, recognising the need for a high capacity motorway. Furthermore, while the studies for the project began in 1966, it was ensured that the design and funding remained up to date as they were only completed leading up to the project’s implementation. Having done this, it may be asserted that the project and the current needs of the city were considered and served by the project.

Another key difference is that the date projections for different major milestone phases include a risk contingency period in Australia. This was highlighted by the Port of Melbourne Case Study, Channel Deepening Project in Victoria. As interruption or factors causing delay are mostly external to the project, it can be difficult to predict when they may arise. Allowing a contingency period to accommodate such factors can be highly useful in stakeholder management; which, if not managed adequately, may lead to further delays. In addition to this, the dates for smaller milestone achievement are not widely published to public sources in the Australian case studies, as opposed to the case studies in Indonesia. Taking this into account, and the additional risk contingency period, delays caused by stakeholders are reduced, allowing the project to meet the date of final completion within time (as publicised). The Channel Deepening Project is a great case study for this, as it was subjected to significant stakeholder caused interruption and yet was able to make the deadline for final completion, end of 2009.

Here, it must be highlighted that this section does not compare between projects in Australia and Indonesia due to their geographical differences, rather between projects that followed the benchmark processes as opposed to not. The M7 Motorway in Sydney and the Channel Deepening project for the Port of Melbourne both followed the Gateway Review Process as a benchmark process guideline for their implementation. The Gateway Review process supports the importance of a linear, logical process, milestones to be met and a major review by an external party taking place after each major milestone. This aims to identify any problem areas through external consultation and ensure all pre-requisites are met as progress is made towards the next milestone. This allows for any discrepancies to be picked up and magnified through progress into the project. Furthermore, the project plan is reviewed and developed accordingly and maintained regularly to ensure it is up to date.

Through study of the Indonesian case studies mentioned in this chapter, it was identified that the project progress is done in a non-linear model where several tasks towards key goals are in the pipeline at any one time, as also highlighted in Fig. 4.12. While this is an attempt to fast track the project due to regulatory and legislative bottlenecks, it often tends to lead to other delays where slight discrepancies may be overlooked and cause major consequences at a later stage. Furthermore, this has contributed to a lack of transparency and a loss of confidence for financial investors.

4.4.2 Findings

A key point of difference between the two systems, and a factor causing delay for projects in Indonesia, is the absence of an external expert review mechanism for major projects. As highlighted by the literature, one of the major contributory factors for project delays is improper planning mechanisms (Department of Treasury and Finance, n.d.). Therefore, a robust business case is key for the successful implementation of a project, and an expert review panel for the project and each of its processes may be able to identify any factors lacking from the initial study that may be a later cause of concern and result in the ultimate delay or termination of the project.

Furthermore, a third-party review mechanism increases the confidence for a prospective investor, increasing the bankability of the project and hence attracting private investors.

References

Abednego, MP and Ogunlana, SO 2006. ‘Good project governance for proper risk allocation in public-private partnerships in Indonesia’, International Journal of Project Management, 24:7, pp. 622–34.

Amin, TM 2015. PPP opportunities of water supply projects in Indonesia, Ministry of Public Works and Housing, Republic of Indonesia, National Supporting Agency for Water Supply System Development.

Asmarini, W, Tan, F and Heavens, L 2017. Pertamina looks for partner to take majority stake in Bontang refinery project, Hydrocarbon Processing, www.hydrocarbonprocessing.com/news/2017/02/pertamina-looks-for-partner-to-take-majority-stake-in-bontang-refinery-project

Atmo, G, Duffield, C and Wilson, D 2015. ‘Attaining value from private investment in power generation projects in Indonesia: An empirical study’, CSID Journal of Sustainable Infrastructure Development, 1:1, pp. 65–79.

Australian Government, Department of Finance and Administration 2006. Public Private Partnerships: Risk management, www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/FMG_Business_Case_Development.pdf

Barker, J 2017. ‘STS, governmentality, and the politics of infrastructure in Indonesia’, East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal, 11:1, pp. 91–9, www.doi.org/10.1215/18752160-3783565

Basri, MC 2016. ‘Comment on “Improving connectivity in Indonesia: the challenges of better infrastructure, better regulations, and better coordination”’, Asian Economic Policy Review, 11, pp. 239–40, www.doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12139

Basu, M 2016. ‘96% of Jakarta has no sewage system’, Government Insider, www.govinsider.asia/inclusive-gov/96-of-jakarta-has-no-sewage-system/

Chemonics International, Resource Management International, Sheladia Associates 1994. Description of existing private sector participation projects and Public Private Partnership projects in Indonesia — and an analysis of lessons learned, United States Agency for International Development, www.pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACB657.pdf

CIMIC n.d. WESTLINK M7, CIMIC, https://www.cimic.com.au/our-business/projects/completed-projects/westlink-m7

Cooke, D 2007. ‘Bay dredge to go ahead’, The Age, 1 November, www.theage.com.au/news/national/bay-dredge-to-go-ahead/2007/10/31/1193618943809.html

Department of Infrastructure and Transport 2010. Infrastructure planning and delivery: Best practice case studies, Commonwealth of Australia, www.infrastructure.gov.au/infrastructure/publications/files/Best_Practice_Guide.pdf

Department of Treasury and Finance n.d. Gateway — overview, www.dtf.vic.gov.au/Publications/Investment-planning-and-evaluation-publications/Gateway/Gateway-review-process-Guidance-materials

Flyvbjerg, B 2005. Policy and planning for large infrastructure projects: Problems, causes, cures, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, www.doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-3781

Jakarta Post 2017. ‘Government to prepare capital’s relocation’, The Jakarta Post, 4 July, www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/07/04/government-to-prepare-capitals-relocation.html

Haryanto, R 2015. Getting into infrastructure game: Regulatory framework in the procurement process for funding schemes, KPPIP, www.austrade.gov.au/.../1418/IABW_Infra_Rainier-Haryanto.pdf.aspx

Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) 2012. Sewerage and sanitation: Jakarta and Manila, The World Bank Group, www.lnweb90.worldbank.org/oed/oeddoclib.nsf/DocUNIDViewForJavaSearch/4BE7A12A7DD3B01A852567F5005D897C

Indonesia Investments 2016. Indonesian Government seeks investors for Bontang Oil Refinery, www.indonesia-investments.com/news/todays-headlines/Indonesian-government-seeks-investors-for-bontang-oil-refinery/item6485?

Indra, BP 2011. PPP policy and regulation in Indonesia, Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS), http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/47377646.pdf

Investor Daily 2015. ‘Government reviews West Semarang SPAM’, Investor Daily, www.indii.co.id/index.php/en/news-publication/weekly-infrastructure-news/government-reviews-west-semarang-spam

KPPIP 2016. KPPIP’s Report for August-December 2015, KPPIP, www.kppip.go.id/en/publication/kppip-semester-reports/

Lucas, C 2007. ‘Dredge may raise water level in bay’, The Age, www.theage.com.au/news/national/dredge-may-raise-water-level-in-bay/2007/10/31/1193618976026.html

Lucas, C and Murphy, M 2007. ‘Ready, set - start dredging’, The Age, www.theage.com.au/news/national/ready-set--start-dredging/2007/10/31/1193618975646.html

Manning, C 2015. ‘Jokowi takes his first shot at economic reform’, East Asia Forum, www.eastasiaforum.org/2015/09/13/jokowi-takes-his-first-shot-at-economic-reform/

Millar, R 2008. ‘Options abound but easy choices are few’, The Age, www.theage.com.au/news/national/options-abound-but-easy-choices-are-few/2008/02/01/1201801037863.html

Ministry of Finance 2012. Government fiscal and financial support on infrastructure project, Republic of Indonesia, Fiscal Policy Office, World Export Development Forum.

Negara, SD 2016. ‘Indonesia’s infrastructure development under the Jokowi administration’, Southeast Asian Affairs, pp. 145–65.

Olken, BA 2007. ‘Monitoring corruption: Evidence from a field experiment in Indonesia’, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 115, no. 2, pp. 200–49.

Pangeran, M, Pribadi, K, Wirahadikusumah, R and Notodarmojo, S 2012. ‘Assessing risk management capability of public sector organizations related to PPP scheme development for water supply in Indonesia’, Civil Engineering Dimension, 14:1, pp. 26–35, www.doi.org/10.9744/ced.14.1.26-35

Puspa, A W 2016. ‘Drinking water supply: Land for West SEMARANG SPAM prepared’, Bisnis Indonesia.

PwC 2017. Vice President inaugurates construction of Umbulan SPAM, PwC.

Ray, D and Ing, LY 2016. ‘Addressing Indonesia’s infrastructure deficit’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 52:1, pp. 1–25, www.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2016.1162266

Roads and Maritime Services 2015. ‘M7’, Roads and Maritime Services, NSW Transport, www.rms.nsw.gov.au/projects/key-build-program/building-sydney-motorways/m7.html

Sandee, H 2016. ‘Improving connectivity in Indonesia: The challenges of better infrastructure, better egulations, and better coordination’, Asian Economic Policy Review, 11, pp. 222–38, www.doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12138.

Sherwell, P 2016. ‘$40bn to save Jakarta: the story of the great Garuda’, The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/nov/22/jakarta-great-garuda-seawall-sinking

Singgih, VP 2017. ‘Finances halt Pertamina projects’, The Jakarta Post, www.pressreader.com/indonesia/the-jakarta-post/20170608/281539405928906

Smith, J, Wiryawan, A and Ray, D 2017. Kemen PUPR collaborates with Japan to provide IPALs up to face detection device, PwC, www.pwc.com/id/en/media-centre/infrastructure-news/june-2017/kemenpupr-collaborates-with-japan-to-provide-ipals-up-to-face-de.html

Sulistyoningrum, Y 2016. Infrastructure projects tender for West Semarang SPAM postponed, Bisnis Indonesia, http://indii.co.id/index.php/en/news-publication/weekly-infrastructure-news/infrastructure-projects-tender-for-west-semarang-spam-postponed

Susanty, F 2016. Drinking water project contract signed after 43-year delay, The Jakarta Post, www.pressreader.com/indonesia/the-jakarta-post/20160722/282029031582155

Syarizka, D 2016. Drinking water supply: Certainty for Umbulan Project, Bisnis Indonesia, www.indii.co.id/index.php/en/news-publication/weekly-infrastructure-news/drinking-water-supply-certainty-for-umbulan-project

Tempo.co. 2017. ‘Pertamina to name partner on Bontang Refinery Project in April’, Tempo.co., www.en.tempo.co/read/news/2017/02/14/056846281/Pertamina-to-Name-Partner-on-Bontang-Refinery-Project-in-April

The World Bank 2017. Jakarta sewerage and sanitation project (JSSP), The World Bank, www.worldbank.org/P003827/jakarta-sewerage-sanitation-project-jssp?lang=en

Transnational Institute 2016. National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) project in Jakarta Bay, TNI, www.tni.org/es/node/23337

The Age 2008. ‘Protest buzz as Queen steams in’, The Age, www.theage.com.au/news/national/protest-buzz-as-queen-steams-in/2008/01/29/1201369136015.html

1 Professor of Engineering Project Management, Deputy Head of Department (Academic), Dept. of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne.

2 Senior Lecturer and Academic Specialist, Dept. of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne.

3 Research Assistant, Dept. of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne.