2. Non-Communicable Diseases, NCD Program Managers and the Politics of Progress

© S. Reddiar and J. B. Bump, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0195.02

2.1 Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are a defining problem of the twenty-first century,1 with an estimated economic loss of 7 trillion US dollars (USD) and counting to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) between 2011 and 2025.2 By 2020, NCDs are expected to cause seven out of every ten deaths in developing countries.3 This challenge raises many questions, including how to raise the priority of NCDs on national policy agendas, augment capacities and identify resources to overcome it. Over the last decade, international agreements and three high-level meetings on NCDs held by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly (in 2011, 2014 and 2018)4 have outlined the tolls NCDs take on individual and collective health outcomes and affirmed that preventing and controlling NCDs is essential to national, regional and global development. These political actions have been supported and reinforced by substantive technical guidance. For example, following the UN’s Political Declaration on NCDs in 2011, WHO developed a global monitoring framework5 and identified sixteen Best Buy interventions as part of the 2013 Global Action Plan for Prevention and Control of NCDs.6 UN Member States now also receive support to collect and analyze surveillance data on NCDs.7

However, the continued rise of NCDs shows that increased political attention and knowledge of prevention strategies has yet to translate into effective policy implementation at national and local levels. For example, the cost-effectiveness of prevention has been demonstrated broadly, including in the WHO 2018 ‘Saving lives, spending less’ report.8 The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), in collaboration with WHO, has also developed briefs on how multiple sectors can engage in the prevention of NCDs.9 Yet, NCDs receive less than 2% of all health funding globally,10 and less than 1% in LMICs.11 Additionally, as we explore in this chapter and has been shown in the Caribbean region,12 NCD funding has been concentrated on ensuring political commitment, as opposed to implementation activities. In part, this gap reflects the challenge of the many contextual factors that affect NCDs. Universally applicable solutions for NCDs are in short supply because these diseases and their related risk factors are strongly influenced by cultures, habits, lifestyles and other circumstances, which have an impact on the distribution of NCDs observed at local level. Implementing global recommendations also requires investment in data capture and management, governance structures, political buy-in and other capacities that may not be present in many settings. These contextual challenges impede efforts to advance NCD policy and action at national levels. Understanding the constellation of activities required to address NCDs, and then adapting them appropriately to address local circumstances, requires deft political and technical negotiation as well as action.

In this chapter, we identify reasons why global policy recommendations to address NCDs have not translated easily into effective programs and action. We focus our research on the experiences of national NCD managers and their reflections on local capacity and challenges. NCD managers are typically located in a Ministry of Health and responsible for an NCD unit, with a mandate focused on NCDs. We reasoned that their position within ministries of health would give them insights into the institutional arrangements, interests and ideas involved in advancing or challenging NCD action. The chapter begins by presenting our methods, followed by an explanation of NCD units and the NCD manager position. We used the ‘Three-I’s’ framework (institutions, ideas and interests), to structure our findings and concluded with recommendations for NCD program managers and others for advancing progress against NCDs.

2.2 Methods for Interviews and Analysis

We gathered data by conducting semi-structured interviews with national NCD managers, representatives from WHO and civil society organizations and urban-level implementers. The interview guide (available in the Online Appendix 2)13 was organized around three themes: priority-setting, work patterns and context. First, we asked about prioritization and allocation of resources for NCDs (including staffing, money and political attention). Second, we elicited descriptions of how NCD managers and others in related positions work, including how they organized their own work and engaged other stakeholders within the Ministry of Health and other ministries, as well as patient groups and civil society groups. Third, we asked about successes achieved and challenges faced in order to gather information about factors and conditions that had influenced their outcomes. Throughout, we sought to understand how and why actions by NCD managers and units were (or were not) translated into NCD prevention and control.

Informants were identified by several means. We consulted NCD experts at the Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) of the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand. In connection with Chapter 4, HITAP had solicited case studies from NCD managers on Best Buys, Wasted Buys and Contestable Buys; we issued interview invitations to the authors of approximately one-quarter of the cases. We also networked with contacts at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and WHO to reach other possible interviewees.

In total, seventeen NCD experts agreed to an interview. We began each interview with an explanation of the project and pledged not to report personally identifying information without obtaining express permission. Of the interviewees, five were women and twelve were men. Eight were from the Asia/Pacific region (Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, Philippines (x2), Sri Lanka and Thailand); three from the Americas (Ecuador, Mexico and the Pan-American Health Organization regional office); three from Europe (Finland, Georgia and the WHO European Regional Office); and three from Africa (Ethiopia, Guinea and Kenya). Among our respondents were one NCD program implementer (Asia/Pacific region) and two who commented on regional considerations. A large majority (fourteen) of the interviewees were physicians. The others had backgrounds in health-related academia, consulting, or research positions. Fourteen interviews were carried out in English and three in Spanish. The interviews lasted for approximately twenty to forty minutes and were conducted via the internet and telephone.

To structure our findings, we chose the 3-I’s framework: Institutions, Interests and Ideas. This analytical framework from the field of political science uses the 3-I’s to describe processes involved in public policy development14. According to the framework, ‘Institutions’ represent the structures and norms that influence political behavior. These include issues of governance, mandates, mechanisms of accountability and hierarchical structures. We use the ‘Institutions’ category to describe and analyze the NCD unit structure, its position within national ministries of health and its relationships with other ministries and relevant stakeholders. The ‘Interests’ component represents stakeholders affected by the policies in question and their respective agendas. Taking account of interests also requires sensitivity to power dynamics among and between stakeholders, and the successes and failures the stakeholders may experience. For the purposes of this chapter, we interpret interests as incorporating the various sectors involved in NCD action, including those that are not formal health services, with their own particular influences and preoccupations. ‘Ideas’, lastly, represents evidence, knowledge and the values of all policy makers, stakeholders and the public. ‘Ideas’ also includes ways to represent NCD policies and global recommendations for the advancement of NCDs at national level.

2.3 Institutions: NCD Managers, NCD Units and Ministries of Health

We were told that NCD units (and also NCD Divisions or NCD Programs) are recent bodies in national ministries of health.15 Over 50% of the NCD units and programs whose managers and representatives we interviewed had been established in the early 2010s,16 and all informants reported that attention to NCDs had increased in the past five to ten years in their countries. They cited various reasons for this, beginning with the rising NCD burdens brought on by aging populations and increased exposure to risk factors, noting that ‘risk factors are easier to identify and target [with vertical mechanisms]’.17 Tools, guidelines and frameworks produced over this period such as the Package of Essential NCD interventions (WHO PEN)18 and the STEPswise approach to surveillance (STEPs) surveys19 by WHO were also referenced as influential in increasing the attention paid to NCDs. On average, NCD managers had worked in their positions for close to nine years, with many having been appointed when the unit was established or shortly thereafter. The average number of employees in the NCD units or related programs in our sample was seventeen, with a range of nine to fifty (excluding front-line providers and implementers). All respondents reported having between one and three people working on NCDs at a managerial level. We were not able to learn exactly how this compares with the number of staff dedicated to communicable diseases, although our interviewees indicated that it was higher than for NCDs.

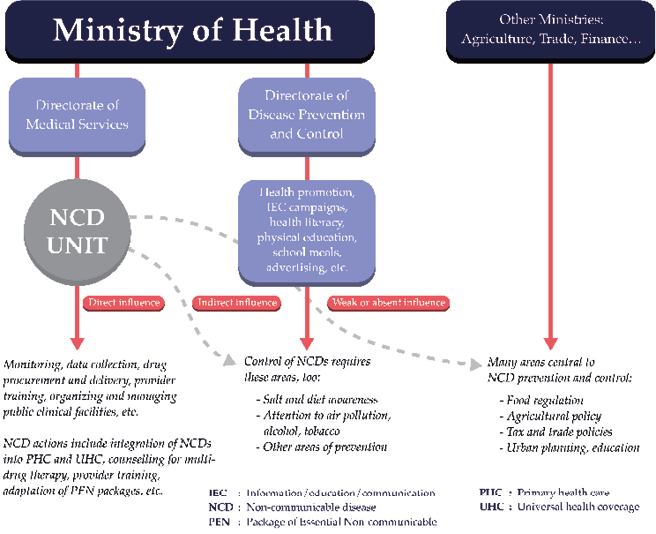

Fig. 2.1 Ministry of Health Organization and consequences for NCD Units.

Interviewees reported that ministries of health were generally organized in two broad divisions: one was responsible for public health and health promotion, and the other had a mandate for service delivery and disease control. In over 40% of our cases, the NCD units (inclusive of two NCD divisions, one national and one regional)20 were located in the service delivery and disease control division or directorates. In these cases, respondents explicitly noted that the NCD units did not oversee the management of risk factors, such as tobacco smoking, alcohol use and dietary improvement; these were instead addressed either in the Ministry’s health promotion or public health directorates, or in separate units. Two countries21 in our sample had no specific NCD units or program, three had NCD units or programs that sat in the disease prevention and control directorates,22 two sat in public health or prevention and promotion directorates23 and one division sat under direct regional administration.24 As shown in Figure 2.1, the placement of the NCD unit inside a larger directorate has consequences for its influence — strong within the directorate but relatively limited in other directorates, which was also mentioned by interviewees in relation to authority over NCD risk factors and preventive action.

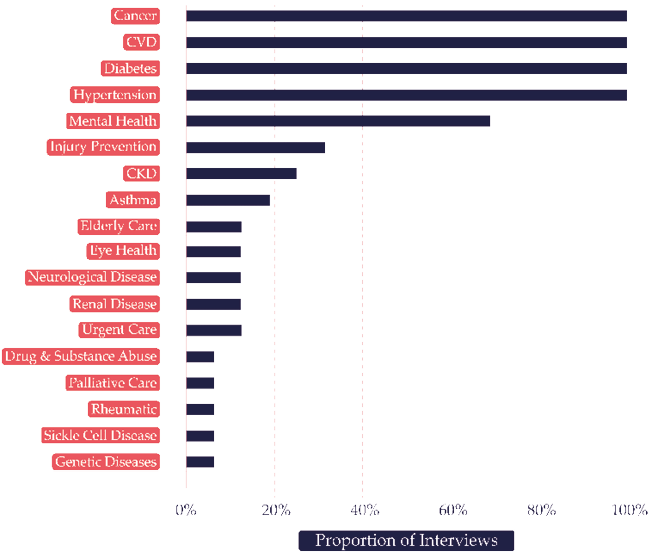

We were told that the mandates of the NCD units were reflected in national NCD policies and action plans. These task NCD units with responsibility for diseases that vary according to the country that was reporting. Some NCDs were common to all countries, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension and cancers. Others, for example, rheumatic disease,25 sickle cell disease26 and eye health,27 were mentioned in only one or two countries. Other cited NCDs addressed by the NCD units and national plans included chronic kidney disease,28 mental health,29 neurological diseases,30 asthma,31 genetic diseases32 and renal diseases.33 Interviewees also mentioned NCD policies encompassing elderly care,34 injury prevention,35 urgent care,36 palliative care37 and drug and substance abuse.38 Commenting on the breadth of NCDs covered, one manager suggested that ‘even the concept of “NCDs” is a problem […] it is not easy to understand […] it seems too large’.39 In turn, because of this large scope ‘the challenges [NCD managers] have [are] on coordination’.40 Figure 2.2 below summarizes the frequency with which particular NCDs were mentioned as a proportion of interviews in which they were cited.

Fig. 2.2 NCDs ranked by proportion of interviews in which they were mentioned.

Nearly 40% of respondents reported that cancers were dealt with differently from other NCDs.41 Reasons included the high funding demands for cancer and the need for stronger health system capacity to address cancer incidence. Respondents also noted that cancer management requires control over risk factors, such as air pollution, that cannot be addressed by NCD units or ministries of health alone, requiring the engagement and support of other ministries and stakeholders — the Ministry of Environment and polluting industries were cited, among others.

The NCD units included in our sample were engaged in a broad set of activities, ranging from raising awareness about NCDs to designing NCD policies and programs. In nearly 90% of the country cases in our sample, NCD units were responsible for technical coordination, capacity building and training of health personnel, advocacy and awareness-raising. Most respondents also described undertaking activities such as the creation of tools and recommendations for training front-line providers in provincial centers and integrating NCD screening into health services. Data collection and monitoring, through STEPS surveys, Burden of Disease Studies42 and Disease Control Priorities Project43 (DCP3), were also cited as key responsibilities of nearly all NCD units in our sample. However, no national or regional NCD units were directly involved in implementation efforts, as these were responsibilities carried out by other stakeholders, including other ministries, local health officers and civil society organizations.44 Additionally, in most of the sampled countries, legislative processes precede the implementation of NCD efforts operationally and in priority.

2.4 Interests: Stakeholders and Power

The complex multiple causal pathways of NCDs are influenced by many sectors beyond health care,45 including trade, agriculture and education, making multisectoral coordination especially important. All of our respondents recognized that, for NCD prevention in particular, approaches often fall outside the scope of ministries of health, with one interviewee reflecting that tobacco and alcohol industries ‘are tackled with the muscle of other institutions.’46 All respondents similarly emphasized the importance of multisectoral engagement and political buy-in for implementation efforts. Examples of stakeholders with whom NCD managers and units work, particularly for the implementation of NCD policy, include other national ministries, the private sector and civil society. Respondents also acknowledged receiving funding and technical support from international organizations such as WHO, NCD Alliance, Partners in Health, PATH (the global health nonprofit), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the World Bank. WHO was cited by all respondents as an active contributor to the advancement of NCDs in national policy agendas and as helping to raise awareness of NCD burdens. More than one-third of interviewees reported that their countries had adopted the WHO PEN47 and had begun at least partial implementation. The WHO’s recommendations on restrictions on tobacco and alcohol through the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)48 and the Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol49 had also been considered, with nearly 60% of the countries in the sample having enacted legislation in at least one of these areas50 and the remaining countries working to do so.

NCD managers and units engaged with vested stakeholders in several different ways across our sample countries, and no two countries reported having the same multi-stakeholder engagement model. Some respondents used roundtable discussions, focus groups and research collaborations. Nearly one-quarter of the respondents reported that NCD action in their countries was overseen by multisectoral committees in which authority and decision-making was rotated and shared among members;51 this structure was specifically cited for the oversight of key risk factors such as unhealthy diets and tobacco use. Two interviewees reported participating in parliamentary procedures including voting and proposing policy motions, with the Ministry of Health holding ultimate authority.52 Other examples of multi-stakeholder collaborations included working with the Road Safety Ministry to introduce alcohol breathalyzers,53 the introduction of food labeling requirements with the Ministry of Agriculture,54 the promotion of physical activity and healthier diets with and in schools,55 and engaging with the media for mass health promotion campaigns.56

In terms of institutional arrangements for action on NCDs, our respondents reported that decision-making authority usually sat with Ministers of Health or political leaders, stipulating that their role and units ‘[have] little authority’,57 ‘are weak’58 and ‘are not in [a] strong position’.59 Almost all of our interviewees suggested that political leaders were in charge of both funding allocation and priority-setting in national agendas; in these cases, NCDs were competing with other health priorities, and the Ministry of Health was competing with other ministries for attention and resources. As a result, NCD managers reported resorting to knowledge-building and awareness-raising about NCDs, specifically targeted at politicians and Ministers of Health. Ultimately, NCD managers reported that the NCD units alone hold little authority or oversight over setting priorities or making decisions at a national level.

While our respondents recognized the importance of multi-stakeholder engagement, it was cited as a challenge by nearly half of them. About 30% (five out of seventeen respondents) mentioned a lack of coordination of multi-stakeholder meetings and strategies,60 and three managers suggested that NCD action appears daunting and/or confusing to non-experts.61 Some respondents suggested that further guidance and models could help improve multi-stakeholder engagement.

2.5 Ideas: Evidence, Knowledge and Values

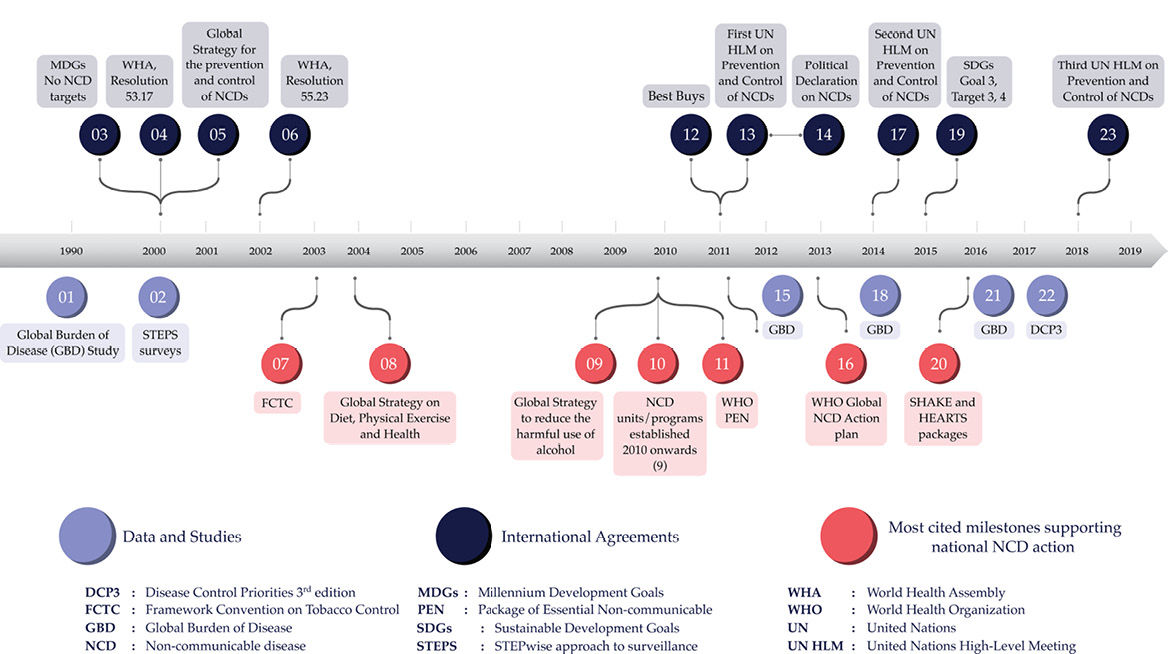

How countries engage in NCD action arguably reflects how NCDs are perceived in that setting. Some NCD managers noted that ‘ten years ago, we [at the national level] did not have any official interest in NCDs,’62 and that attention to risk factors preceded attention to the burden of NCDs, as evidenced by historical efforts. To illustrate the changes in attention to NCDs over the last few decades, we developed a timeline (Fig. 2.3) which highlights international agreements, data and monitoring methods and key milestones that were cited as particularly important by interviewees in achieving national NCD action from legislation to implementation.

Fig. 2.3 Timeline of milestones in NCD action from 1990–2019.

The decade of 2000–2010 was ‘marked by a rebellion against the neglect of the NCDs in the MDGs’,63 and our interviewees held a mixed assessment of how NCDs were currently being prioritized in their countries. Five respondents judged that NCDs were considered a low priority64 with one reporting that ‘NCDs don’t get the attention they deserve considering [the] deaths and morbidity they cause’.65 In contrast, six believed that their countries gave them high priority.66 Across our sample, prioritization among NCDs also varied; cardiovascular disease was cited as the top priority NCD by six interviewees.67 Within the NCD agenda, mental health,68 injury prevention,69 palliative care70 and kidney issues71 were reportedly gaining increasing attention. Some respondents underscored the poor attention given to chronic respiratory diseases.72 In dealing with NCDs at a broader level, seven respondents reported that service provision was, or should be, a higher priority than prevention.73 Service provision examples mentioned included coverage at district level, capacity building and training of service providers, drug procurement, early detection and integration of NCD services with primary care and universal health coverage and, as already reported, service provision received larger budget allocations than prevention in nearly half the units in our sample.

Regarding the prioritization of risk factors, all interviewees highlighted the importance of interventions to promote healthy diets and exercise. Efforts to promote diet and exercise included advertising,74 taxation,75 and educational campaigns.76 One interviewee described an effort to establish outdoor gyms.77 Actions against tobacco and/or alcohol use were cited in nearly 65% of interviews,78 typically in relation to legislation and surveillance. Other risk factors mentioned were air pollution,79 chewing tobacco80 and salt consumption.81 Generally, action for salt reduction lags behind the more common measures for addressing alcohol and tobacco use.

Interviewees described the importance of perception of NCDs in relation to the implementation and uptake of interventions. Factors affecting public perception cited by managers included the influence of politicians in two decision-making settings,82 social networks in five,83 and media in four.84 These factors reportedly influenced attitudes towards screening, healthier diets and health literacy.

In nearly 60% of our interviews, concerns were expressed that the implementation of NCD action lacked buy-in from politicians and stakeholders,85 with some respondents suggesting that NCDs were ‘not a real priority, only a priority on paper’.86 For example, seven interviewees mentioned problems in enforcing legislation.87 Although all countries in our sample had cited the adoption of legislation for controlling tobacco and most other risk factors, four respondents88 noted that there had been limited follow-through, little or no enforcement and few dedicated human or financial resources. Other challenges that were mentioned as impeding action on NCDs included the inability to control the inflow and outflow of potentially harmful substances,89 and weak advocacy efforts.90 Six interviewees cited cultural and behavioral inertia as a challenge.91 This inertia was related in some cases to links between religious practices and carbohydrate consumption,92 perceptions of junk-food consumption as a sign of modernization and prosperity,93 or reliance on neighbors and family members for health information.94 It was also suggested that the delegation of responsibilities outside the NCD unit and Ministry of Health created challenges.

Reflections from respondents were mixed in terms of effective and successful implementation of Best Buys. This finding is relevant because Best Buy recommendations are predominantly focused on risk factor action, which underscores the focus on service delivery by NCD units and the challenges in relation to multisectoral coordination that have already been highlighted. While all respondents reported that the recommended alcohol and tobacco legislation was in place, only five respondents95 mentioned implementation of the salt consumption recommendation and a mere two96 mentioned vaccination against human papillomavirus. In one country, drug therapy and counselling services were reported to be available for individuals with diabetes, hypertension, or a history of heart attack or stroke.97 Smoke-free public spaces were cited by four interviewees,98 health information and warnings about tobacco by five,99 and bans on alcohol advertising and restricted access to retail alcohol by two.100 Trans fats were cited by three respondents,101 but with no implementation. Mass-media campaigns relating to diet and physical activity were reported by six interviewees.102 Some suggested that the implementation of Best Buys would benefit from detailed recommendations for implementation at the local level.103 Five respondents also suggested that the Best Buys need to be more sensitive to context.104 Noting that ‘Best Buys are useful to define national priorities, but are not automatic’,105 some interviewees felt that Best Buys are too ‘broad’106 and should consider context-specific capacity and needs, especially as ‘what works in one country is not transferable’.107 Respondents also cited other policies as Best Buys, such as the PEN108 and HEARTS109 (technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care) packages, as well as school meals, though these are not officially designated as Best Buys by the WHO.110

2.6 Discussion

Why have global recommendations and guidance on how to advance action on NCDs not been easily translated into improvements in local health outcomes? Understanding the reasons behind the generally reported difficulties involves examining institutional arrangements of NCD units within ministries, the varied interests of relevant stakeholders and the diverse ideas shaping perceptions of NCDs. Overall, our findings highlight many positive improvements in the recognition of NCDs in national agendas. The informants attributed this development to the combination of emphasis placed on NCDs by global bodies and advocates, changes in population profiles and growing epidemiological evidence of the burden of NCDs. National developments, such as the establishment of NCD units, the adoption of frameworks and policies based on internationally determined good practices, and expanding efforts to collect data on NCDs, were increasingly evident. Furthermore, the types of NCD policies adopted by national governments were largely guided by global-level leadership from WHO. We see these developments as positive examples of global recommendations and stakeholders influencing local agendas and action on NCDs. However, according to NCD managers, many challenges remain, which expose the need for increasing the adaptability of global recommendations to local levels.

The institutional arrangements of NCD units, like service provision divisions of ministries of health, may not be adequate for the adaptation and adoption of global recommendations. For example, many of these recommendations and guidelines, including Best Buy recommendations, address both service delivery and prevention, some aspects of which are outside the mandate of service providers. Moreover, NCDs tend not to have single-cause origins or etiologies and thus cannot be interrupted directly, as is possible with many infectious diseases.111 In some instances, the distinction between prevention and service delivery is not clear, as when addressing diabetes incidence and prevalence by promoting exercise,112 or cases in which chemotherapy is used preventively for certain cancers.113 Some institutional arrangements further limit how global recommendations can support the coordination of prevention efforts. Locating NCD units in service provision strengthens the service delivery components of NCD action. While useful, this structure can, however, separate NCD managers from the overall scope of multisectoral preventive efforts in their own views and the views of other stakeholders.

The institutional mandates of NCD units often require engaging with a broad range of risk factors and activities. Global recommendations do not fully recognize the multitude of tasks that fall to NCD units. For example, the HEARTS114 and SHAKE technical package for salt reduction115 target individual diseases and risk factors; they do not include activities that address the overall mandates of NCD units. The heterogeneity (among countries) and diversity (within countries) of the challenges that contribute to NCDs make it difficult for global actors to promote consistently compelling messages and effective policies.

Grouping all NCDs in one unit within a ministry contrasts starkly with the prevailing practice for addressing infectious diseases. A ministry generally comprises many units, some responsible for a single disease (such as malaria or tuberculosis) and some presiding over a group of related diseases (such as sexually transmitted infections). The breadth of diseases designated for the NCD unit creates operational challenges. One of our informants mentioned that ‘there’s a lot of debate about what NCDs are’,116 which we interpret to underscore the difficulty of developing technical competence and strategic partnerships across a large portfolio of NCDs, which vary from country to country. Furthermore, it generates challenges in the ways in which NCDs are perceived by stakeholders, potentially exacerbating confusion and frustration in the time-frame required to see results. Political influence and buy-in to address the full range of NCDs is also especially difficult, given the complexities involved and the inherent competing priorities. A similar challenge arises from trying to address an array of diseases without duplicating efforts, which could be particularly difficult for NCDs located within disease-prevention-and-control directorates. Finally, the funding and staffing allocations for NCD units were generally low, especially when compared with communicable disease units.

The difficulties engendered by the institutional arrangements and mandates of NCD units are underscored by a lack of evidence on best practices for coordinating the interests of multiple stakeholders. Although we found it encouraging that all interviewees reported that NCD units work with various stakeholders on implementation, prevention and risk reduction, among other activities, the effectiveness of such engagements has not been well documented. One manager suggested that ‘the NCD community […] are not yet embracing health systems components’117 and others expressed a need for frameworks or other guidance on how to engage stakeholders successfully for coordinated action. Existing efforts, including available tools118 and documents,119 have not yet been widely mainstreamed nor have they been especially relevant in national settings.

The diversity of stakeholders with whom NCD units sought to engage reflects the breadth of concerns and risk factors connected with NCDs. For a unit with just one, two, or three managerial positions, coordination across the full range of stakeholders for NCDs represents a monumental task. We identified a need for further research to develop guidance on organizing a bureaucracy for effective NCD action. This also highlights a gap in the existing global recommendations: identifying best practices for multi-stakeholder action to mainstream NCD action in recognition of the multiple demands NCD unit mandates have.

Respondents also stated that there was nearly always a strong focus on upstream action, such as legislative efforts or the development of national strategies. Relatively little focus was placed on downstream activities such as multisectoral coordination, with one interviewee noting that ‘the solution is there, we just need to do it’.120 An emphasis on upstream action could possibly be interpreted as a weak commitment to NCDs—after all, implementation is typically more resource-intensive than policy making. It could also indicate that the international guidelines and frameworks have focused too much on securing mandates rather than on supporting operational activities, which is underscored by one of our respondents reflecting that ‘the time is now for implementation, not further standards and norm-setting’.121 This is also reflected in our interviewees frequently discussing Best Buy recommendations in relation to legislative efforts with relatively low enforcement capacity. Poor enforcement of policies may result from a lack of focus on operational aspects or capacity, resulting in a lack of designated responsibility and corresponding accountability for implementation and enforcement. If the consequences of not enforcing a policy, including a lack of clarity about who is responsible, have not been clearly outlined, policies will not be effectively implemented. Ultimately, NCD managers might, in addition to their current roles, also be forced to take on responsibility for enforcement. Alternatively, they could develop strong liaisons with those delegated to implement in order to ensure buy-in and attention to NCD action. Incidentally, these interviewees reminded us that beyond the FCTC,122 global action against commercial and environmental determinants of health has, as of yet, been modest.

Finally, the interviews revealed clearly that, while international advocacy and recommendations have successfully raised the level of attention given to NCDs in at least some countries, ‘the challenge has now reduced itself to implementation, [requiring] a different set of skills’123 to assist countries in contextualizing recommended approaches and adapting priorities to their specific needs. A major obstacle to such downstream actions was the limited knowledge and engagement that national political leaders demonstrated in relation to NCDs, as well as general ideas and perceptions of NCDs among government and population as a whole. To a large extent, global movements, rather than domestic advocacy, promoted NCDs within national policy agendas. Limited implementation of NCD policies at national level could also be interpreted as an indication of a disconnect between global and local perceptions of NCDs. NCD units and other advocates for NCD action need to build domestic support more systematically, including by educating national and local politicians. Additionally, the WHO should consider developing regionally contextualized recommendations that are easier for countries to use and adapt.

2.7 Limitations

The research that informed this chapter had several limitations. First, despite extensive efforts over eight months to recruit interviewees, we received fewer positive responses than we wanted. A larger sample could have generated more, and more generalizable, conclusions. Second, although the interviewees represented a variety of countries and regions, the sample was skewed towards Asia, which made regional comparisons difficult. Third, the breadth and diversity of NCDs and settings encompassed in the interviews made it hard to investigate specific themes consistently. Fourth, the interview guide and the time allocated for interviews allowed for a high-level exploratory approach, as distinct from an exhaustive study of NCD efforts in the countries in our sample. Fifth, our interviews were not always conducted in the interviewees’ first languages. This may have resulted in some confusion and limited the nuances of some responses. Finally, low-quality internet connections made some interviews especially difficult.

2.8 Conclusions and Recommendations

NCDs remain a key health-system challenge for virtually every country in the world.124 Global NCD recommendations are rarely directly relevant and applicable to local settings. NCD units in national ministries of health face challenges in adopting and adapting global best practices to advance NCD action. These challenges arise from the mandates given to and institutional arrangements made for the units, the necessity of engaging with relevant stakeholders with diverse ideas and the difficulties inherent in prioritizing NCDs in relation to other national health and development plans. Nevertheless, encouraging developments are evident, particularly in the form of national legislation and other upstream actions. The WHO also has an important presence in local settings.

In our interviews with national NCD managers and similar actors, two needs were clearly revealed: first, support for stronger action downstream from the NCD unit; and second, improved frameworks for multi-stakeholder engagement and multisector coordination efforts. The implementation challenges reported by NCD managers revealed that additional leadership, resources and innovation were required. Meeting some of these needs lies beyond the remit and authority of either the NCD managers or ministries of health, outlining the ongoing role of global institutions and non-governmental organizations.

We propose three action points, based on our findings and analysis, that could support the translation of global NCD recommendations into better NCD outcomes at the local level:

- Expand global support for engaging political leadership in NCD agendas. NCD managers reported that the limited knowledge and engagement among senior political leaders was a major obstacle to prioritizing action on NCDs. We recommend developing advocacy guidance and materials for use by NCD managers. Technical experts, such as NCD managers, need simplified tools for educating and discussing key NCDs and related policies with potential advocacy partners (such as professional associations, patient groups and influential individuals who have personal experience with an NCD). Additionally, global institutions should use their access to senior politicians to create opportunities to conduct joint outreach and advocacy efforts. We recommend that global NCD advocates and experts collaborate with health ministers and NCD managers to identify one or more NCDs to emphasize and generate interest and action for relevant policies and programs.

- Expand the managerial and institutional structures responsible for NCDs to reflect operational requirements and realities. Most NCD units are not fully equipped or resourced to take on the complete range of NCDs and relevant activities. The placement of NCD units in either the public health or the service delivery division of the Ministry of Health represents a serious limitation. Even the attempt to narrow the programmatic approaches to pragmatic dimensions by identifying Best Buys still leaves NCD units with an extraordinarily wide range of activities to oversee. We recommend that NCD units, ministries and global institutions consider expanding or creating parallel managerial structures aligned with the capacities needed to execute NCD programs. Alternatively, a simplification of the mandates of NCD units to target country-specific needs could facilitate managerial structures.

- Generate effective guidance and support to stimulate multisectoral coordination, collaboration and action. The NCD unit has little control or authority over the causes of and contributors to the vast majority of NCD risk factors. Although ‘multisectoral action’ has become a prominent buzzword of late, our interviews revealed that NCD managers neither had guidance on how to do it nor knew with precision what it was. However, NCD units are a natural focal point for discussing many multisectoral issues, such as tax policies for discouraging tobacco, alcohol and other harmful substances, and environmental protections to improve nutrition and food security. We recommend that NCD managers immediately begin pursuing informal relationships to foster such discussions, while global institutions develop specific, actionable and context-sensitive guidance for NCD managers on this topic.

1 Sara Glasgow and Ted Schrecker, ‘The Double Burden of Neoliberalism? Non-communicable Disease Policies and the Global Political Economy of Risk’, Health and Place, 39 (2016), 204–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.003

2 World Health Organization and United Nations Development Programme, What Legislators Need to Know: Non-communicable Diseases, 2018, https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/HIV-AIDS/NCDs/Legislators%20English.pdf

3 Samira Humaira Habib and Soma Saha, ‘Burden of Non-Communicable Disease: Global Overview’, Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews, 4.1 (2010), 41–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2008.04.005

4 World Health Organization, ‘United Nations High-Level Meeting on Non-communicable Disease Prevention and Control’, 2011, https://www.who.int/nmh/events/un_ncd_summit2011/en/; World Health Organization, ‘High-Level Meeting of the UN General Assembly to Undertake the Comprehensive Review and Assessment of the 2011 Political Declaration on NCDs’, 2014, https://www.who.int/nmh/events/2014/high-level-unga/en/; World Health Organization, ‘Third United Nations High-Level Meeting on NCDs’, 2018, https://www.who.int/ncds/governance/third-un-meeting/en/

5 World Health Organization, NCD Global Monitoring Framework, 2017, https://www.who.int/nmh/global_monitoring_framework/en/

6 World Health Organization, Tackling NCDs: Best Buys, 2017, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf?sequence=1

7 World Health Organization, STEPwise Approach to Surveillance (STEPS), 2019, https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/en/

8 World Health Organization, Saving Lives, Spending Less: A Strategic Response to Non-communicable Diseases, 2018, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272534/WHO-NMH-NVI-18.8-eng.pdf?ua=1

9 United Nations Development Programme, What Government Ministries Need to Know about Non-Communicable Diseases, 2019, https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/hiv-aids/what-government-ministries-need-to-know-about-non-communicable-diseases.html

10 World Health Organization, Non-communicable Diseases and Their Risk Factors, 2019, https://www.who.int/ncds/management/ncds-strategic-response/en/

11 World Health Organization, Saving Lives, Spending Less: A Strategic Response to Non-communicable Diseases.

12 W. Andy Knight and Dinah Hippolyte, Keeping NCDs as a Political Priority in the Caribbean: A Political Economy Analysis of Non-Communicable Disease Policy-Making, 2005, https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=forum-key-stakeholders-on-ncd-advancing-ncd-agenda-caribbean-8-9-june-2015-7994&alias=36065-keeping-ncds-as-a-political-priority-caribbean-andy-knight-065&Itemid=270&lang=en

13 Available at https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/09617d51

14 National Collaborating Centre for Health Public Policy, Understanding Policy Developments and Choices Through the ‘3-i’ Framework: Interests, Ideas, and Institutions, 2014, http://www.ncchpp.ca/docs/2014_procpp_3iframework_en.pdf; N. Bashir and W. Ungar, The 3-I Framework: A Framework for Developing Policies Regarding Pharmacogenomics (PGx) Testing in Canada. Genome., 2015, https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/70678/1/gen-2015-0100.pdf

15 Interview 1, ‘Consultant, Ministry of Health, Asia-Pacific Region,’ Skype interview, 29 November 2018; Interview 2, ‘Advisor, Ministry of Health, European Region,’ WhatsApp interview, 20 December 2018; Interview 3, ‘NCD Manager, Ministry of Health, African Region,’ WhatsApp interview, 18 December 2018; Interview 4, ‘NCDs Program Advisor, Ministry of Health, African Region,’ Skype interview, 18 December 2018; Interview 5, ‘NCD Program Manager, Ministry of Health, African Region,’ WhatsApp interview, 18 December 2018; Interview 6, ‘Former Director of Technical Support Body, Ministry of Health, Asia-Pacific Region,’ Skype interview, 24 January 2019; Interview 7, ‘Program Officer, Ministry of Health, Asia-Pacific,’ Skype interview, 8 March 2019; Interview 8, ‘Advisor for NCDs, Regional Organization,’ Skype interview, 12 March 2019; Interview 9, ‘Senior Official, Ministry of Health, Americas Region,’ Skype interview, 18 February 2019; Interview 10, ‘Senior Official, Ministry of Health, Americas Region,’ Skype interview, 12 April 2019; Interview 11, ‘Officer, Multilateral Organization, Asia-Pacific Region,’ in-person interview, 1 February 2019; Interview 12, ‘Former Officer, Multilateral Organization, Asia-Pacific Region,’ in-person interview, 1 February 2019; Interview 13, ‘NCD Department Head, Ministry of Health, European Region,’ Skype interview, 12 April 2019; Interview 14, ‘Country Representative, Multilateral Organization, Asia-Pacific Region,’ Skype interview, 15 March 2019; Interview 15, ‘NCD Division Director, Regional Organization,’ Skype interview, 15 March 2019; Interview 16, ‘NCD Program Coordinator, City-Level, Ministry of Health, Asia-Pacific Region,’ Skype interview, 28 March 2019; Interview 17, ‘Senior Official, Ministry of Health, Asia-Pacific Region,’ Facebook Messenger interview, 8 May 2019.

16 Interview 1; Interview 3; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 7; Interview 8; Interview 9; Interview 10; Interview 15.

17 Interview 15.

18 World Health Organization, Tools for Implementing WHO PEN (Package of Essential Non-communicable Disease Interventions), 2019, https://www.who.int/ncds/management/pen_tools/en/

19 World Health Organization, STEPwise Approach to Surveillance (STEPS).

20 Interview 3; Interview 5; Interview 6; Interview 8; Interview 11; Interview 12; Interview 14.

21 Interview 2; Interview 10.

22 Interview 4; Interview 9; Interview 16; Interview 17.

23 Interview 7; Interview 13.

24 Interview 15.

25 Interview 4.

26 Interview 5.

27 Interview 4; Interview 17.

28 Interview 1; Interview 4; Interview 7; Interview 8.

29 Interview 2; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 6; Interview 8; Interview 12; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 16; Interview 17.

30 Interview 4; Interview 14.

31 Interview 4; Interview 9; Interview 16.

32 Interview 15.

33 Interview 1; Interview 16.

34 Interview 3; Interview 16.

35 Interview 8; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 16.

36 Interview 14; Interview 15.

37 Interview 7.

38 Interview 17.

39 Interview 5.

40 Interview 5.

41 Interview 3; Interview 7; Interview 9; Interview 10; Interview 14; Interview 17.

42 Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2019), http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

43 Disease Control Priorities: Economic evaluation for health, DCP3, 2019, http://dcp-3.org/

44 Interview 1; Interview 2; Interview 3; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 6; Interview 7; Interview 8; Interview 9; Interview 10; Interview 11; Interview 12; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 17.

45 World Health Organization; Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Non-communicable Diseases, 2019, http://www.emro.who.int/noncommunicable-diseases/publications/questions-and-answers-on-the-multisectoral-action-plan-to-prevent-and-control-noncommunicable-diseases-in-the-region.html

46 Interview 3.

47 Interview 5; Interview 7; Interview 11; Interview 12; Interview 16; Interview 17; World Health Organization, Tools for Implementing WHO PEN (Package of Essential Non-communicable Disease Interventions).

48 World Health Organization, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, 2003, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42811/9241591013.pdf?sequence=1

49 World Health Organization, Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol. World Health Organization, 2010, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44395

50 Interview 1; Interview 2; Interview 4; Interview 6; Interview 11; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 16, Interview 17.

51 Interview 2; Interview 6; Interview 10; Interview 13.

52 Interview 2; Interview 13.

53 Interview 7.

54 Interview 7; Interview 10; Interview 17.

55 Interview 1; Interview 2; Interview 5; Interview 9.

56 Interview 1; Interview 6; Interview 10; Interview 13.

57 Interview 6.

58 Interview 5.

59 Ibid.

60 Interview 1; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 14; Interview 17.

61 Interview 3; Interview 5; Interview 15.

62 Interview 5.

63 Interview 15.

64 Interview 3; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 13; Interview 16.

65 Interview 3.

66 Interview 1; Interview 2; Interview 7; Interview 9; Interview 10; Interview 17.

67 Interview 4; Interview 8; Interview 12; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15.

68 Interview 2; Interview 4; Interview 6; Interview 8; Interview 12; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 16; Interview 17.

69 Interview 8; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 16.

70 Interview 7.

71 Interview 1; Interview 4; Interview 6; Interview 7; Interview 8.

72 Interview 9; Interview 14; Interview 15.

73 Interview 1; Interview 3; Interview 5; Interview 6; Interview 13; Interview 16; Interview 17.

74 Interview 1; Interview 3; Interview 5; Interview 13; Interview 16; Interview 17.

75 Interview 2; Interview 6; Interview 9; Interview 10; Interview 11; Interview 17.

76 Interview 1; Interview 2; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 10.

77 Interview 7.

78 Interview 1; Interview 2; Interview 4; Interview 6; Interview 8; Interview 10; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 16; Interview 17.

79 Interview 2; Interview 4; Interview 9; Interview 13; Interview 14.

80 Interview 4; Interview 11.

81 Interview 4; Interview 6; Interview 7; Interview 8; Interview 11; Interview 13; Interview 14; Interview 16.

82 Interview 3; Interview 4.

83 Interview 1; Interview 2; Interview 5; Interview 7; Interview 13.

84 Interview 1; Interview 6; Interview 10; Interview 13.

85 Interview 2; Interview 3; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 6; Interview 9; Interview 14; Interview 15; Interview 16; Interview 17.

86 Interview 6.

87 Interview 3; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 6; Interview 12; Interview 15; Interview 17.

88 Interview 3; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 6.

89 Interview 2.

90 Interview 5; Interview 13.

91 Interview 1; Interview 4; Interview 5; Interview 9; Interview 13; Interview 14.

92 Interview 1.

93 Interview 5.

94 Interview 13.

95 Interview 4; Interview 6; Interview 7; Interview 11; Interview 17.

96 Interview 13; Interview 16.

97 Interview 16; Interview 17.

98 Interview 6; Interview 10; Interview 16; Interview 17.

99 Interview 6; Interview 10; Interview 12; Interview 16; Interview 17.

100 Interview 6; Interview 13.

101 Interview 7; Interview 9; Interview 16.

102 Interview 1; Interview 5; Interview 6; Interview 10; Interview 13; Interview 16.

103 Interview 2; Interview 4; Interview 9; Interview 14; Interview 15.

104 Ibid.

105 Interview 9.

106 Ibid.

107 Interview 2.

108 World Health Organization, Tools for Implementing WHO PEN (Package of Essential Non-communicable Disease Interventions).

109 World Health Organization, Hearts: Technical Package for Cardiovascular Disease Management in Primary Health Care, 2016, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/252661/9789241511377-eng.pdf?sequence=1

110 Interview 7; Interview 10; Interview 16; Interview 17.

111 Center for Disease Control, Overview of Non-communicable Diseases and Related Risk Factors, 2013, https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fetp/training_modules/new-8/Overview-of-NCDs_PPT_QA-RevCom_09112013.pdf

112 Igor P. Briazgounov, ‘The Role of Physical Activity in the Prevention and Treatment of Noncommunicable Diseases’, World Health Statistics Quarterly, 41.3–4 (1988), 242–50.

113 Science Direct, Adjuvant Chemotherapy, 2017, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/adjuvant-chemotherapy

114 World Health Organization, Hearts: Technical Package for Cardiovascular Disease Management in Primary Health Care.

115 World Health Organization, The SHAKE Technical Package for Salt Reduction, 2016, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250135/9789241511346-eng.pdf?sequence=1

116 Interview 14.

117 Interview 14.

118 World Health Organization, Toolkit for Developing, Implementing and Evaluation the National Multisectoral Action Plan (MAP) for NCD Prevention and Control, 2019, http://apps.who.int/nmh/ncd-map-toolkit/index.html

119 World Health Organization, Approaches to Establishing Country-Level Multisectoral Coordination Mechanisms for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases’, 2015.

120 Interview 1.

121 Interview 15.

122 World Health Organization, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

123 Interview 14.

124 Ala Alawan, The NCD Challenge: Progress in Responding to the Global NCD Challenge and the Way Forward, 2017, https://www.who.int/nmh/events/2017/discussion-paper-for-the-ncd-who-meeting-final.pdf