2. ‘The Deepest Well of German Life’1: Hierarchy, Physiognomy and the Imperative of Leadership in Erich Retzlaff’s Portraits of the National Socialist Elite

© Christopher Webster, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202.02

The Führerprinzip (The Leader Principle)

Since the end of the Second World War, historians have variously characterised the leadership of the National Socialist state as ‘a rationally organised and highly perfected system of terrorist rule’;2 or as necessarily chaotic, with Adolf Hitler ultimately holding the key to power as the ultimate arbiter of a polycratic structure of leadership;3 or even as an ‘authoritarian anarchy’.4

Whatever the historical reality — order or chaos, irrationality or well-oiled bureaucracy — the visual manifestation of the National Socialist leadership at least, was artfully manufactured to present an unambiguous hierarchy of representatives of the Führerprinzip). Such a hierarchy and its legitimacy during and following the years of struggle was, unsurprisingly, reiterated regularly in visual terms by National Socialist publications and, of course, in the writings of the political leaders themselves. The principle permeated the state from Hitler, as Führer, down through to the most basic elements such as a Hitlerjugendführer of the Hitler Youth.

Although predating National Socialism as an idea, the leadership notion, the Führerprinzip, certainly emerged as a core structural element of the National Socialist state in a new form. After Thomas Carlyle and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s notion of the ‘Great Man’, the desire for a ‘ruler-sage’ became more pronounced in the milieu of the post-war republic in Germany. However, many conservative thinkers were suspicious of the National Socialists as being too similar to the communists. For example, thinkers such as Count Hermann Keyserling — widely associated with coining the phrase Führerprinzip) — believed that the ‘ruler-sage’ could only emerge when an ‘aristocracy of the truly best’5 had emerged and not through a rule of the masses.

In his 1974 book Notes on the Third Reich,6 that exponent of Integral Traditionalism, the philosopher Julius Evola, argued that the interpretation and application of the Führerprinzip by National Socialism had been a new (but flawed) elucidation of an ancient tradition. Evola objected to a biologically reductionist interpretation that regarded race as the foundation of the state; for Evola, such an interpretation missed the ‘soul and spirit’ of man.7

He remarked:

First, at that time this bond [the Führerprinzip] was established only in an emergency or in view of definite military ends and, like the dictatorship in the early Roman period, the character of the Führer (dux or heretigo) did not have a permanent character. Second, the ‘followers’ were the heads of the various tribes, not a mass, the Volk. Third, in the ancient German constitution, in addition to the exceptional instances in which, in certain circumstances as we have mentioned, the chief could demand an unconditional obedience — in addition to the dux or heretigo — there was the rex, possessed of a superior dignity based on his origin.8

Evola’s summary of Hitler’s interpretation of the notion of the Führerprinzip is certainly accurate:

For Hitler, the Volk alone was the principle of legitimacy. He was established as its direct representative and guide, without intermediaries, and it was to follow him unconditionally. No higher principle existed or was tolerated by him.9

For his part, Hitler had stated in Mein Kampf:

… the natural development, though after a struggle enduring centuries, finally brought the best man to the place where he belonged. This will always be so and will eternally remain so, as it has always been so. Therefore, it must not be lamented if so many men set out on the road to arrive at the same goal: the most powerful and swiftest will in this way be recognised, and will be the victor.10

Influential conservative German cultural figures, who cautiously (or enthusiastically) moved into the orbit of the party after its election victory of 1933, also (often enthusiastically) gave legitimacy to the National Socialist version of the idea. The following three examples are of leading German cultural figures from three different disciplines — jurisprudence, science and the arts — who each lauded the new dispensation and the central role of the Führerprinzip to National Socialism.

According to the political scientist and jurist Carl Schmitt:

The strength of the National Socialist state resides in the fact that it is dominated and imbued from top to bottom and in every atom of its being by the idea of leadership. This principle, by means of which the movement has grown great, must be applied both to the state administration and to the various spheres of auto-administration, naturally taking into account the modifications required by the specificity of the matter. It would not be permissible, though, to exclude from the idea of leadership any important sphere of public life.11

The poet, writer and dramatist Heinar (Heinrich) Schilling wrote a series of essays for the SS (reproduced in the SS journal Das Schwarze Korps) where he outlined certain ideological principles including the Führerprinzip. In his 1936 Weltanschauliche Betrachtungen (Reflections on a Worldview) he outlined the notion of the Führerprinzip as the cornerstone of the new state, with its incorporation into the political and public realm being a significant departure from earlier political and social norms. It was, he declared, a new era, when, ‘the nonsense of voting was removed by the introduction of an authoritarian form of government, re-establishing the Führerprinzip in a completely new form consistent with current political conditions…’. This, according to Schilling meant the ‘restoration of the dominance of an autochthonous blood…’ and ‘… a return to the roots of the historical conditions of our nationhood’.12 Schilling emphasised, therefore, what he interpreted as National Socialism’s unique merger of ‘natural law’, leadership, and heredity, as each being synchronous and symbiotic elements of this new polity.

Similarly, in his 1938 text Heredity and Race; An Introduction to Heredity Teaching, Racial Hygiene and Race Studies, Dr Gustav Franke firmly positioned biological hierarchy in the political realm. Franke asserted a social Darwinist interpretation of biology, in which ‘… there can hardly be any doubt that man’s hereditary endowment, having been examined in diverse areas of human genetic predispositions, has been subject to well-established regulations for the rest of living nature.’ As a result, according to Franke, this acceptance of self-evident biological differences ensured that the only conclusion was that some races were ‘superior’ to others, and such an ‘irrefutable’ conclusion had resulted in a situation in which ‘… Marxists of all colours cling to the hopeless equality dogma as their last straw of hope. Certainly, they cannot seriously dismiss the overwhelming abundance of Mendel’s previously examined case studies on the effectiveness of the laws of inheritance.’13

The three figures discussed above were each asserting their acceptance of the recognition of an ‘iron logic of nature’, as Hitler had called it in Mein Kampf. This was a logic that allowed for no other possibility: to attempt to reject such an immutable force, according to Hitler, would only lead man ‘to his own doom’. 14

With the arrival of a National Socialist government in 1933, the ‘iron logic of Nature’ became a firm part of political, social, and cultural thinking. It was seemingly supported by science (an interpretation of a Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’ had already been popularised in Germany by Charles Darwin’s friend and disciple, the German scientist Ernst Haeckel) as well as being popularised by a complex mix of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century esoteric and religious interpretations ranging from Theosophy to Ariosophy.15

The Führerprinzip) was based both on a biological imperative of an elite destined for leadership, as well as a parapsychological current that ensured ‘natural magicians’ (like Hitler) ‘also had strong characters and leadership capabilities, which is why ‘the Magician is in all earlier times identical with “Ruler”’.16 These two currents of biological imperative and parapsychological need (Eric Kurlander’s ‘Supernatural Imaginary’), represent two powerful streams that mingled to form the National Socialist German state. The exoteric current relates to the German state that is familiar in historical narratives about this period. Germany became a militaristic state that looked to remove the shame of the Versailles Treaty and reunify historical and mythic aspects of a greater ‘Germania’. National Socialist Germany was a state that aspired to be autarkical, modern, and simultaneously cognisant of blood and tradition.

The second stream was esoteric, sometimes tenuous, still partly hidden, often darkly controversial. This influence is less widely known; it also played a significant part in defining what Germany would become under National Socialism. This was a subterranean river, a Germanic Acheron, that flowed with ideas of the irrational, the metaphysical, the notions that acted upon ‘the Will’. It sprang from a Germany that looked to reject the curse of Nietzsche’s ‘Last Man’ and inculcate the superman or Ubermensch. The combination of these two currents fed the belief in a ‘palingenesis’ where a new world would rise, phoenix-like, from the ashes of the old.17

As the National Socialists began to embrace the image enthusiastically as part of their efforts to achieve a supremely effective style of visual propaganda, it became the task of the artist and the photographer to frame, in Evola’s words, this ‘principle of legitimacy’ in a visually powerful and enduring manner during the Third Reich itself.

The visual representation of the Führerprinzip) is examined here through an examination of the creative and aesthetically guided lens of Erich Retzlaff, where, as will be seen, aesthetics and physiognomy (science and esoterica) merged in an imaging (and imagining) of power and leadership in the photographic image beyond the image of the Führer himself.

Physiognomy

As both a social and scientific fad, physiognomy had, by the 1920s, achieved enormous cultural popularity. Examinations of people and society were predicated on the belief that the face and body could be read like a book to reveal nature and character. An example of the (often complex) broad engagement with, and interpretation of, physiognomy in the Weimar era is provided by the Jewish writer, critic, and associate of the Frankfurt School, Walter Benjamin. Reflecting on August Sander’s physiognomic studies in his essay a ‘Little History of Photography’ (1931) Benjamin discussed the inevitability of a physiognomic regime of the future: ‘Whether one is of the right or the left, one will have to get used to being seen in terms of one’s provenance. And in turn, one will see others in this way too. Sander’s work is more than a picture-book, it is an atlas of instruction.’18 In the same essay, Benjamin contextualises Sander’s physiognomic achievement in relation to that of avant-garde Soviet filmmakers: ‘August Sander put together a series of faces that in no way stand beneath the powerful physiognomic galleries that an Eisenstein or a Pudovkin revealed, and he did so from a scientific standpoint’.19 Not only was this physiognomy paramount, but considerations of nurture and nature were believed to play a part. For example, in his introduction to Sander’s Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), the writer Alfred Döblin reflected: ‘… they were moulded by their race and the development of their personal ability — and through the environment and society which promoted and hindered their development.’20

The reading of the face was supposed to rely on the ‘indexical and iconic functions’ of the photographic form. However, according to Matthias Uecker, such endeavours were ultimately, ‘subsumed under a discourse that — despite its declarations to the contrary — valorizes “reading” over “seeing” and ultimately reduces all images to examples or illustrations of a pre-ordained discursive knowledge’.21

As explored by Claudia Schmölders in her book Hitler’s Face, photography and physiognomy played an important role in visually defining the leadership credentials of the Führer himself, both prior to and after his accession to power.

No face bears more eloquent witness to the desire for… [a] physiognomic interpretation than this face, in which half a nation between 1919 and 1938 wanted to recognize pure, undiluted futurity, among them the most educated Germans… Since the eighteenth century there prevailed in Germany a tradition of reading physiques, in science and in art, in literature and in politics — a tradition that existed so emphatically only in Germany. Around the same time that Hitler came to Munich, this tradition was modernized for the beginning of the “short century” … as the physiognomic gaze on the “great man” and the “German Volk” …22

This tradition was especially evident in the photographic depictions of Hitler’s face-as-biography through the work of his ‘court photographer’ Heinrich Hoffmann. Hoffmann first met Hitler in 1919 and he became a fixed member of Hitler’s inner circle, accompanying him constantly until the end in 1945. Hoffmann’s practical monopoly of the image of Hitler made him a wealthy man.23 In his photographic publications such as Hitler wie ihn keiner kennt (Hitler as No-One Knows Him, 1933) and Das Antlitz des Führers (The Face of the Leader, 1939), and even the image of Hitler on postage stamps, it was Hoffmann’s work that defined (and helped direct) the formation of Hitler’s image from his early days as the messianic figure of the struggle in marches and speeches, to Hitler the ‘ordinary’ man relaxing in private, through to the statesman on his appointment as Chancellor of the Reich in 1933. For example, in a set of early images from around 1925,

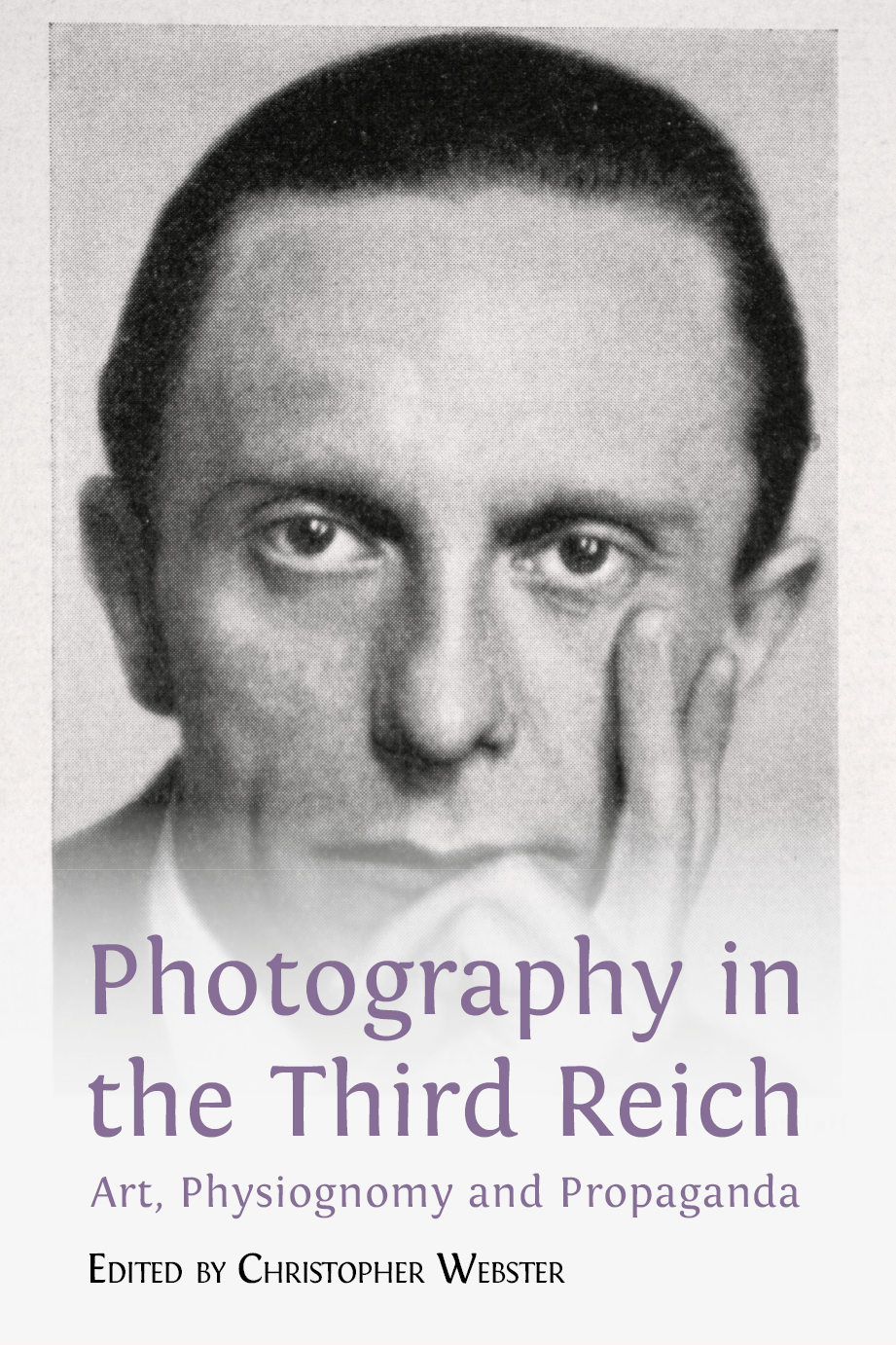

Fig. 2.1 Heinrich Hoffmann, Adolf Hitler, 1927, reproduced in Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler Was My Friend (London: Burke, 1955), pp. 72–73. Fair use.

Hitler, miming to his own recorded speeches, adopts a series of dramatic poses in front of a mirror with Hoffmann’s camera recording the process. These private images were clearly designed to assess the effectiveness of a gesture or a look and, after Hitler looked them over, he instructed Hoffmann to destroy them (Hoffmann, having disobeyed his Führer’s instructions, later published these images in his 1955 book Hitler Was My Friend). What these images reveal is how crafted and rehearsed, almost operatic, Hitler’s public performances were and how much Hitler understood that posture, gesture and facial expression could be used as powerful messages in their own right. By 1933, Hoffmann’s portrayals of the Führer reveal a man seemingly assured and powerful in his role as autocrat of a National Socialist Germany.

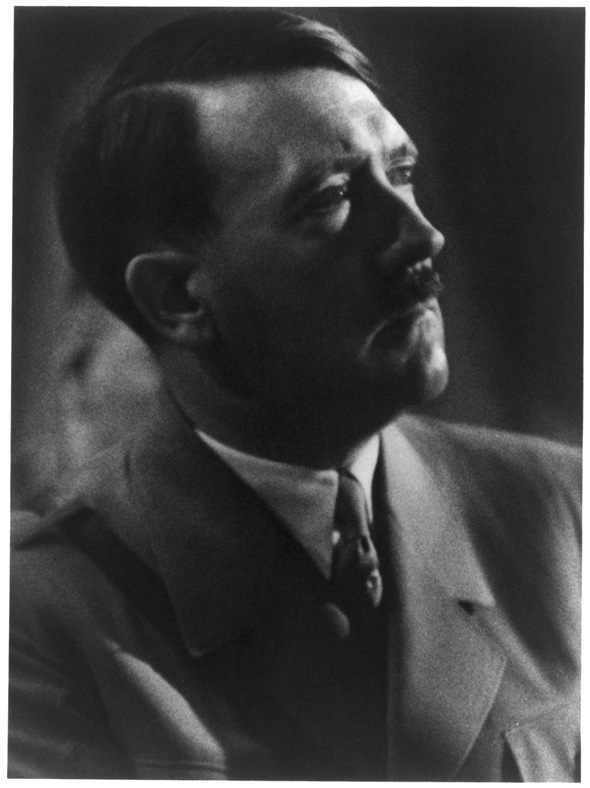

Fig. 2.2 Heinrich Hoffmann, Adolf Hitler [no date recorded on caption card], vintage silver gelatin print, retrieved from the Library of Congress. Public domain, www.loc.gov/item/2004672089/

Despite this visual domination in terms of the image of the Führer,24 Reichs-bildberichterslatter (the Reich photojournalist) Hoffmann was not the sole photographic arbiter of the National Socialist physiognomic leadership.

Erich Retzlaff’s career commenced during the nadir of the Weimar republic, and he became particularly well known for his photobooks in an era when the picture album was a popular carrier of ideas and influential cultural mores.25 Retzlaff produced intense, close-up photographs of his subjects, primarily German peasants and workers, influenced by the New Vision style and with an almost visceral visual presence. As will become apparent here, he also played a significant role in the photographic staging of the Führerprinzip.

This approach certainly came to employ ideological paradigms that would play a role in defining a specific and important facet of the iconography of National Socialist propaganda. However, the aesthetics employed also place his work firmly in the canon of early twentieth-century modernist photography. As well as being related to the physiognomic practices of his contemporaries, Retzlaff’s photographs of rural workers are also reminiscent of the work of American Depression-era photographers such as Dorothea Lange or Margaret Bourke-White.

Retzlaff was a technical innovator too. He was significant to the history of photography in relation to his early experimentation with the innovative Agfacolor Neu colour film process in Germany. His contribution to a 1938 book, Agfacolor, das farbige Lichtbild (Agfacolor, the Colour Photograph) included an essay entitled Farbige Bildnisphotographie (Colour Portrait Photography),26 centred on how to use the new materials in portraiture, and a series of Retzlaff’s own striking colour portraits. Retzlaff remarked:

With colour film we have, for the first time, been given a material that puts us in a position to explore fields that formerly had been outside the capabilities of black and white photography. Everything is still virgin soil, but the possibilities for this medium of colour photography within all areas of life, art and science are evident… Within race-theory and studies of national tradition, there will be entirely new areas to be conquered by aesthetically creative photographers as well as scientists; colour photography will be indispensable to the fields of physiognomy and ethnology. There is no doubt that colour photography will enable us to broaden our knowledge of the world.27

As the above quote demonstrates, Retzlaff was thinking in terms of both science and artistic expression, an amalgam of photography, ethnography, and aesthetics.

This complex ‘modern’ made photographs until 1945 that also conformed very much to a traditionalistic völkisch ideology. Retzlaff’s photographs present the worker-peasant as part of a racial collective, a German ‘type’, inextricably bound to the soil of his homeland. This approach employed aesthetics with an ostensibly documentary approach, much as his US contemporaries were doing, albeit towards different political ends.

Retzlaff came to photography as a means to engage with the post-war artistic milieu of Weimar, to express himself artistically and simultaneously make a living. He had worked in a succession of commercial jobs after his demobilisation at the end of the First World War, but his interest in, and social contact with, the emergent Weimar art scene convinced him that he too might become an artist. But Retzlaff could not easily paint; he had a badly damaged right hand, a legacy of his time as a soldier on the front during the war.28 Instead, he set up a small photographic studio on the Königsallee in Düsseldorf. With the enthusiasm of an amateur and no formal training, Retzlaff set out to learn his craft. His early studio portraits were flattering, competent, and conventional. The business thrived and he was soon able to move to larger premises on the Kaiserstrasse. But this commercial work was not enough for the young Retzlaff who, like so many of his generation, was restless and disenchanted by the post-war Versailles settlement and the prospect of being submerged into an ‘ordinary’ life.29

In the late 1920s, Retzlaff became intensely interested in the kind of modern photography he was seeing in exhibitions, journals, and the new picture magazines — portraiture in particular. It is likely that Retzlaff had seen the work of August Sander, whose first exhibition had been reviewed in the Rheinische Post in 1928.30 Certainly, it was during this period that Retzlaff began to explore physiognomy in his portrait practice.

As Retzlaff’s studio style changed and aligned itself more and more to an objective and broadly modern approach with a physiognomic premise, the flattering soft-focus work he had employed in his early commissions was replaced by a sharp-focus style, as evident in his portrait of the Düsseldorf gallerist and art dealer Alexander Vömel.31

Fig. 2.3 Erich Retzlaff, Kunsthändler Alexander Vömel (Art Dealer Alexander Vömel) c.1933, Aberystwyth University, School of Art Museum and Galleries. Courtesy of the Estate of Erich Retzlaff.

Retzlaff’s new interest in physiognomic photography and in particular working on location was certainly influenced by the photographer Erna Lendvai-Dircksen. Lendvai-Dircksen was, like Retzlaff, herself influenced by the new style of ‘straight’ photography and photographed in a manner that was direct and dramatically cropped.32 In particular, Lendvai-Dircksen, a studio photographer of some note, was focussing more and more on the physiognomic portrait of the autochthonous peasant.33

Already by the Weimar period, physiognomy had become inextricably bound up with race. This new momentum was epitomised by the books of comparative race and physiognomy produced by populist racial ideologues such as Hans F. K. Günther.34 For those sympathetically nationalist photographers like Retzlaff35 and Lendvai-Dircksen, their interpretation of physiognomy was coloured by a völkisch interpretation of race, particularly in their photographs of the Bauer or peasant. These portrayals attempted to point to something beyond classification, something numinous, whilst employing the supposedly objective eye of the camera to produce the racial-physiognomic photograph.

When Germany became a National Socialist state in 1933, Retzlaff had already published three books of portrait photographs of the physiognomic German proletariat. His first publication, Das Antlitz Des Alters (The Face of Age, 1930), was very well-received and had a number of positive critical reviews. There was even a review in the USA, where the anonymous reviewer for the Quarterly Review of Biology found that ‘the viewpoint and the purpose of this beautiful volume are literary and artistic rather than scientific…’ with its, ‘… superb portraits of some 35 old men and women…’36

The succeeding two volumes echoed the format of the first, with an emphasis on the face, the drama of the closeness to the subject and the large-scale format of their reproduction. As with Das Antlitz Des Alters, his dual volume Deutsche Menschen37 (volume one, Die von der Scholle, concerned with rural people and volume two, Menschen am Werk, concerned with industrial workers) presented anonymous subjects. It is not the individual who is important, but rather their presentation as a type from a collective. The people are described by their occupation, whether it is a farmer or a blast furnace worker or a railwayman (for example, Figure 2.4).

Fig. 2.4 Erich Retzlaff, Hochofenarbeiter (Blast Furnace Worker), 1931, reproduced in Menschen am Werk (Göttingen: Verlag der Deuerlichschen Buchhandlung o.J., 1931), p. 9. Public domain.

These volumes set the standard that Retzlaff would follow for the next fifteen years, including his forays into colour photography after 1936. Retzlaff had become recognised as an influential creative practitioner in National Socialist Germany. In addition to his work appearing in numerous books,38 it was also widely reproduced in the press and popular magazines as well as in National Socialist journals such as Odal, Volk und Rasse, NS-Frauen-Warte and, during the war, Signal. As in his studio portraits, his work continued to extend beyond the image of the peasant. Covers for Volk und Rasse included portraits of the military leader type, the hero, the Führerprinzip) as expressed on the battlefield. For example, Retzlaff’s portrait of a decorated paratrooper from the cover of a 1941 edition of Volk und Rasse is, like his peasant portraits, anonymous and presented as an example of a (victorious) ‘Nordic type’ (see Fig. 2.5).

Fig. 2.5 Erich Retzlaff, kompagnieführer und Anführer der fallschirmjäger bei Dombas in Norwegen. Nordische führergestalt (Company Leader and Leader of the Paratroopers at Dombas in Norway. Nordic Leader) reproduced on the cover of Volk und Rasse, 1941. Public domain.

The characteristics of the portrait are typical. As artfully lit as that of a film star, this profile image describes the rugged features in the context of the dashing hero figure, with a powerful focussed gaze and framed tightly, contextualised by the sartorial elegance of the uniform and accompanying military decorations. The unnamed Luftwaffe officer is described in the title as an example of a ‘Nordic leader figure’.

Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (Pioneers and Champions of the New Germany)

The establishment of Retzlaff’s oeuvre in his successful photographic volumes, in addition to his pre-1933 membership of the party, resulted in his commission to photograph a cross-section of the new German political elite. This commission became the text Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (1933)39 that was produced to celebrate the electoral victory of the NSDAP and the establishment of a ‘rightist’ coalition government.40 Produced by the Thule Society member and influential nationalist publisher Julius Friedrich Lehmann, this 64-page illustrated paperback opens with a foreword from Wilhelm Freiherr von Müffling:

With this great change in German history, a fountain of new forces has been unleashed. This people’s movement, created by the leader Adolf Hitler, has given to the German people men who, with an ardent love of their Fatherland and the highest sense of responsibility, have begun the task of building the nation.41

The opening pages present a double page spread with two images, one on each page.

Fig. 2.6 Frontispiece from Wilhelm Freiherr von Müffling, ed., Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (Pioneers and Champions of the New Germany) (Munich: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1933). Public domain.

The first is of Paul von Hindenburg and the second a Hoffmann image of Adolf Hitler. These foundational images use the doubling technique to create a relationship between the pair, to demonstrate their connectedness and thus the premise of the ‘revolution’. In the left-hand image, Reichspräsident (Reich’s president Hindenburg fixes the reader with his gaze. Hindenburg is photographed in three-quarter profile, a grand patriarchal figure poised between what has been and what will come. This elderly but firm figure represents the past, the era before the war, the martial tradition of the war itself and what must be preserved from that historical tradition. On the opposite page, Hitler looks to his right, the viewer’s left, symbolically towards Hindenburg. Shown in profile, his physiognomy is presented clearly. Younger and fresher, the new Chancellor is established as someone looking to the past respectfully whilst simultaneously representing the new order, his body positioned as if he is looking backwards whilst moving forwards. As the viewer reads from left to right, Hitler’s position on the right-hand side clearly represents the future. Thus, the volume’s theme is established. A new beginning built upon the firm foundations of tradition and custom. The intended message is clear: this revolution is no ‘Bolshevik insurgency’, rather it is presented as a resuscitation of the old by the new, a rebirth of Germany itself through modern forms.

Retzlaff had been commissioned to provide fifty-five of the one hundred and sixty-eight portraits and is specifically named on the title page as follows: ‘Mit 168 Bildnissen von E. Retzlaff (Düsseldorf) und Anderen’. As well as being the single largest provider of photographic portraits for this publication, Retzlaff’s contribution also included some of the most important figures in both the broader conservative movement and in particular the NSDAP. His NSDAP portraits included Heinrich Himmler, Ernst Röhm, Gregor Strasser, Wilhelm Frick, Richard Walther Darré, Robert Ley, Rudolf Hess, Julius Streicher, and Joseph Goebbels, to name but a few.42 Just as in his studies of the peasants of Germany, Retzlaff’s studies of the leadership also employed a physiognomic approach. Rather than simply providing a professionally executed studio photograph, it is apparent from their staging that he was concerned with attempting to capture the essence of the sitter, their physiognomic ‘signature’ and thus the signs of their leadership potential. Retzlaff demonstrated his skills, posing his sitters to best advantage.

Heinrich Himmler’s portrait is a three-quarter profile in chiaroscuro with a key light from above (see Fig. 2.7).

Fig. 2.7 Erich Retzlaff, Heinrich Himmler, 1933, reproduced in Wilhelm Freiherr von Müffling, ed., Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (Pioneers and Champions of the New Germany) (Munich: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1933, p. 56. Public domain.

This provided a suitably imposing and perhaps sinister presence to the portrait of the Reichsführer-SS, accentuating the oval of his face and piercing stare behind his trademark pince-nez. With equally piercing stare, Joseph Goebbels looks back at the camera but in a full-face portrait with a lighter, softer illumination and with Goebbels’ large eyes fixed on the viewer (see Fig. 2.8).

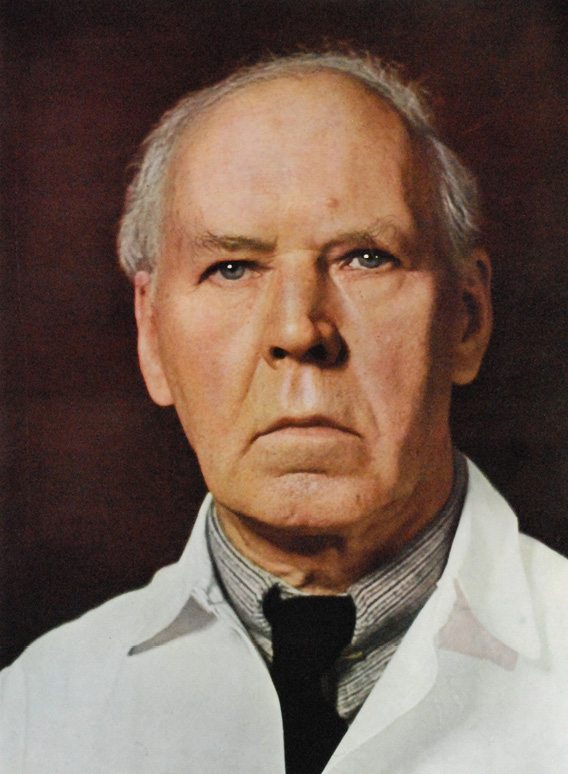

Fig. 2.8 Erich Retzlaff, Joseph Goebbels, 1933, reproduced in Wilhelm Freiherr von Müffling, ed., Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (Pioneers and Champions of the New Germany) (Munich: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1933), p. 11. Public domain.

The doctor is presented as an intellectual and the inclusion of his left hand, supporting his face, reinforces this notion of the thinker. Of Rudolf Hess on the other hand, Retzlaff, always considering the physiognomic aspect, stated: ‘… a very nice person. Not good-looking, and not photogenic, but I had taken him from the right angle’.43

Das Gesicht des Geistes (The Face of the Spirit)

Despite the deprivations of war and an increasingly desperate social, economic, and military situation, Retzlaff continued to be represented in expensive print editions during the 1940s. In 1943, for example, the Alfred Metzner Verlag (Berlin) published his colour studies of childhood Komm Spiel mit mir (Come Play with Me).44 A year later, when the war situation had become even graver, Retzlaff’s work was in print again with both the Metzner Verlag and the Andermann Verlag (Vienna). These publications were respectively, Das Gesicht des Geistes (The Face of the Spirit, 1944) 45 and a volume of his photographs of the people and landscapes of the Balkans, Länder und Völker an der Donau: Rumänien, Bulgarien, Ungarn, Kroatien (Land and Peoples of the Danube: Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Croatia, 1944).46 Both editions were lavishly illustrated with full-colour photo-lithographic images, a clear indication that, for the authorities, Retzlaff’s work was, despite the advent of ‘Total War’,47 considered important enough to have expensive processes and increasingly rare materials and labour made available.48 These publications, Retzlaff’s last made during the National Socialist period, contained Retzlaff’s trademark application of physiognomy — where Länder und Völker explored both geographic and human physiognomy.49 Das Gesicht des Geistes was centred on the face of the German intellectual leadership.

Das Gesicht des Geistes might be considered to be Retzlaff’s physiognomic ‘magnum opus’, although in its final form it was unfinished. A note inserted in the folio reads:

For war-related reasons, the portfolio ‘Das Gesicht des Geistes’ will be produced in two parts. The second set of images will follow as quickly as circumstances allow. The portfolio is offered as a whole: by purchasing this portfolio, the buyer agrees to take the second portfolio.50

The work was the culmination of over fifteen years of developing a physiognomic approach to his photography since his beginnings with the studio work in Düsseldorf. In this new project, Retzlaff brought together nationally celebrated representatives of intellectual leadership, vibrant colour, and his trademark close-up, large-format reproduction. This monumental though incomplete body of work demonstrates that Susan Sontag’s uncompromising assertion that all ‘Fascist’ art was the ‘repudiation of the intellect’51 was in fact far from the truth. After 1945, Retzlaff would continue this dramatic portrait work with a black-and-white volume Das Geistige Gesicht Deutschlands (The Spiritual Face of Germany) published in 1952. But this second volume was a post-war reconceptualization. Das Geistige Gesichts Deutschlands was a subtle repositioning of German ‘genius’ as part of Cold War strategies to demonstrate the creative force of the ‘free’ west in juxtaposition to the Soviet Bloc. The introduction to Das Geistige Gesichts Deutschlands is by Hans-Erich Haack, a former news correspondent, NSDAP apparatchik and West Germany’s first post-war director of the Political Archive. Haack tellingly quotes Goethe: ‘“Man muß die Courage haben”, sagt Goethe, “das zu sein, wozu die Natur uns gemacht hat.”’ (“One must have the courage,” says Goethe, “to be as nature has made us.”)52 The emphasis had shifted by the time of this 1952 publication (if not completely) from the political focus of race and nation to one of political stance and national achievement. Certainly, Retzlaff’s aim in the 1944 volume, Das Gesicht des Geistes, was a representation and recognition of genius and German bearing. The writer Gerhart Hauptmann (himself a subject of the series) introduced the folio in somewhat purple prose, by stating: ‘Should we be proud of the German mind? Well, to think of his achievements makes one almost dizzy. Would a non-German person be able to grasp his universal nature?… Everywhere, in all educated nations, they have embraced his genius with passionate love’.53

The large colour photolithographs of Das Gesicht des Geistes were typical of Retzlaff’s style with their almost uncomfortable cinematic proximity, the very kind of closeness that had been both praised and criticised by critics in the past.54 Their full colour accentuated their presence. The scale at 27 x 37 cm made them life-size or larger. They were unavoidable (see Fig. 2.9).

Fig. 2.9 Erich Retzlaff, Georg Kolbe, 1944, reproduced in Erich Retzlaff, Das Gesicht des Geistes (The Face of the Spirit), (Berlin: Alfred Metzner Verlag, 1944). Public domain.

The significance of the publication Das Gesicht des Geistes was intended to be its presentation of elite individuals as the very apogee of (National Socialist) intellectual and cultural achievement. Their presentation was as a readable face designed to demonstrate a physiognomic reading of their greatness.

Inside, the loose prints were enfolded in a paper text that contained the title and the short introduction by Hauptmann. Each sitter is listed and described briefly in terms of their academic and publication achievements. In total, the selection named twenty poets, novelists, musicians, dramatists, visual artists, historians, scientists, and one industrialist. The subjects included or to be included were (those appearing in the extant folio are marked here with an asterisk):

Emil Abderhalden, biochemist and physiologist*;

Hans Fischer, organic chemist;

Nicolai Hartmann, philosopher*;

Gerhart Hauptmann, dramatist and novelist*;

Ricarda Huch, historian, novelist and dramatist;

Ludwig Klages, philosopher, psychologist and handwriting analysis theoretician;

Börries von Münchhausen, writer and poet*;

Hermann Oncken, political writer and historian*;

Wilhelm Pinder, art historian*;

Max Planck, theoretical physicist*;

Ferdinand Sauerbruch, surgeon;

Heinrich Ritter von Srbik, historian*;

In this eminent company there was only one woman, Ricarda Huch. Some on the list were certainly sympathetic to the regime,55 others were decidedly not but were tolerated (and therefore included) because of their standing. Some of the artistic and literary figures were on the Gottbegnadeten-Liste (Important Artist Exempt List) or the Führerliste (The Leader’s list of exempt artists working for the war effort) such as Gerhart Hauptmann, Richard Strauss, and Börries Freiherr von Münchhausen. These reserved-occupation lists of important artists had been created by the regime in order to protect and exempt these individuals from military service in any form.56

Echoing his work eleven years previously from Wegbereiter, the extant portraits are carefully constructed so that the sitters are posed in one of three classic portrait poses: full-face view looking towards the viewer (four of these); three-quarter profiles with eyes either to the viewer or looking beyond the viewer (three of these); and profile (three of these).

For example, the portrait of Emil Abderhalden is presented in three-quarter profile and, like many of the other portraits, he emerges from darkness (see Fig. 2.10).

Fig. 2.10 Erich Retzlaff, Emil Abderhalden, 1944, reproduced in Erich Retzlaff, Das Gesicht des Geistes (The Face of Spirit), (Berlin: Alfred Metzner Verlag, 1944). Public domain.

His head is illuminated by dramatic directional light that picks out his features from above and to the left. Detail and scale are significant. The presence of the sitter is reinforced by its larger-than-life reproduction; the image almost looms from the frame. Abderhalden’s features are presented to the viewer for a racial-physiognomic reading. With furrowed brow, iron-grey close-cropped hair, long face and square jaw, his hard, blue-eyed gaze is directed out of the right-hand quarter of the rectangle and thus into the distance. In addition to the physiognomic notion of a projection of inner being or character, in National Socialist terms, race is significant too. Race is readable and considered indicative of character and potential. Abderhalden is an elder statesman of ‘Aryan’ stock. According to Günther’s principles, Abderhalden’s racial qualities might be regarded as predominantly Nordic and they are here accentuated alongside the fact of his intellectual significance. Colour photography was able to convey eye colour, hair colour. and skin tone. According to Richard T. Gray, this kind of photography demonstrates,

… just how important the photograph became in Nazi culture as an instrument for training a disciplinary gaze, for developing a form of technologized seeing whose purpose was to strip away the visible veneer of human beings and expose or interpolate an otherwise ‘invisible’ racial foundation that purportedly undergirded it.57

Das Gesicht des Geistes, had it been completed, might have fulfilled Retzlaff’s ambition to achieve a full reckoning of the range of ‘face’ of the National Socialist Volksgemeinschaft (people’s community). Retzlaff had photographed the child, the peasant, the worker, the hero, the leadership, and, in this project, the cerebral engine-room at the start of the ‘thousand-year Reich’. This final racial-physiognomic folio presented the intellectual legacy of the new (National Socialist) dawn. These great-minds-as-image were evidence of a new epoch. As Hermann Burte — an artist, writer and poet himself — emotionally characterised it: ‘A new man has emerged from the depth of the people. He has forged new theses and set forth new Tables and he has created a new people, and raised it up from the same depths out of which the great poems rise — from the mothers, from blood and soil’.58

The portfolio presented to its audience an intellectual nobility (whether that nobility agreed with the regime or not). Their race and their character that was so clearly ‘demonstrated’ physiognomically, photographically, was ‘evidence’ of the advanced nature and continued potential of the (predominantly) Nordic German in particular. It was, according to the race scientist Hans F. K. Günther (writing in 1927), ‘…not to be wondered at […] that it is this Nordic race that has produced so many creative men, that a quite preponderating proportion of the distinguished men […] show mainly Nordic features…’59

The volume Das Gesicht des Geistes was prefaced with a note from the editors stating:

The editor and publisher wish, by selecting these portraits of leaders from the older generation of art and science, to offer a valuable inspiration; they retain the right to bring a selection of the younger generation in another series.60

If, as the editor’s note would suggest, further studies had ever been produced, then the next stage would be a celebration of the new man, the emergent generation of intellectual leaders who had been born during the Third Reich and who would be maturing in the years following the successful conclusion of the war.

Conclusion

During the 1930s and into the war years, Retzlaff aimed to represent the German as the racial acme, a radical and traditional alternative to what was seen by many conservatives as the post-First-World-War economic, ethnic, and spiritual decline of Germany as epitomised by Spengler’s ‘Faustian man’, or the nihilism of the modern world and the dawn of the era of Nietzsche’s ‘Last Man’. Over the course of the twelve years of National Socialism, the work of photographers like Retzlaff became the standard image of a National Socialist aesthetic, reproduced widely in populist, political, and art publications. Retzlaff’s work never featured the racial other as a counterpoint to his visual acclamation of the ‘Aryan’ type. Yet, the ubiquitous presence of his work in journals, magazines, and books provided a powerful reinforcement of National Socialist racial policies and ideology by underlining the state’s desired visual norms and aspirations. These were images that were made to be consumed, enjoyed, and identified with. The fact that they are usually not explicitly ideological (often no banners, flags, insignia, or uniforms) but were implicitly so, is key here. These racial-physiognomic photographs became a form of associative conditioning. The German viewer could examine these ‘readable’ photographs and identify their place in the National Socialist people’s community, the Volksgemeinschaft, with its objective of racial homogeneity and a leadership hierarchy of ability, whilst simultaneously learning to identify (through systems such as physiognomy) those racial elements alien to that body.

Race, and the legacy of the Weimar obsession with physiognomy, became a combined motif in National Socialist propaganda and in the work of the photographers contributing to it. The influence of the racial-physiognomic still photography of Retzlaff and others can be strongly detected in various propaganda applications that followed into the 1940s. For example, a physiognomic approach is clearly evident in a Zeit im Bild (Image of Our Time) propaganda film made in 1942 of the German conductor and composer Wilhelm Furtwängler61 conducting the overture to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger62 before an audience of workers in a factory in Berlin. The camera pans around the audience during the concert and focusses on their faces, creating dramatic stills that might have come directly from a Retzlaff book. Here are enraptured faces, intent on the cultural event.

Fig 2.11. Still from Zeit im Bild (Image of Our Time), 1942, a Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) production. Courtesy of the Bundesarchiv, Film: B 126144-1.

The film cuts to Furtwängler conducting frenetically, the ‘genius’ at his station, then back to the Volk who watch. The youth, rugged workers, combat soldiers, women, the elderly; are all linked by the intensity of their gaze, their ‘Aryan’ credentials clear. Here is the racial-physiognomic study as film, moments seen, carefully framed and lit to accentuate the drama of their faces, these anonymous spectators are united across divisions of class, gender, and occupation; they are united by their immersion in a particularly German moment, immersed in the music of the master, Wagner. The situation is carefully stage-managed, conjoining the lowest proletarian members of the Volksgemeinschaft with the intellectual masters of the past (Wagner) and the cultural leaders of the present (Furtwängler). Moreover, it employs a ‘still’ frame approach that is derived from the legacy and the popularisation of racial-physiognomic photography by photographers like Retzlaff.

If Retzlaff’s early studio portraits provided the overture of this Gesamtkunstwerk63 of photograph, race, and physiognomy, the books of peasant portraits developed the leitmotif, Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer was the chorus of the work, then Das Gesicht des Geistes was the incomplete finale and the post-war Das Geistige Gesicht Deutschlands, was a drawn-out coda. Like the lavish contemporaneous Ufa colour film epics such as Kolberg,64 Das Gesicht des Geistes was most likely intended as an uplifting propaganda fantasy of German resistance and resurgence where the value of the message was considered to outweigh the enormous material cost. Retzlaff’s folio was certainly an expensive visual statement, combining colour and scale with an ideological image of the Führerprinzip in action. Constructed and presented as it was, the intention would have been to encourage resistance, to demonstrate the achievement of the leadership elite, to show what was at stake should the Reich fall, and what could be resumed, once the war was over and National Socialism had triumphed.

1 Jacob Grimm’s ‘Schiller Memorial address,’ 1859. Quoted in Hermann Glaser, The Cultural Roots of National Socialism (London: Croom Helm, 1978), p. 60.

2 Hans Mommsen, ‘Nationalsozialismus,’ in Sowjetsystem und demokratische Gesellschaft. Eine vergleichende Enzyklopädie, Vol. 4 (Freiberg: Herder, 1971), p. 702.

3 Klaus Hildebrand, The Third Reich (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 137.

4 Ibid.

5 Hermann Keyserling, Politik, Wirtschaft, Weisheit (Darmstad: O. Reichl, 1922), pp. 103–04.

6 Originally published as Il fascismo visto dalla destra; Note sul terzo Reich (Rome: Gianni Volpe, 1974).

7 Julius Evola, Notes on the Third Reich, John Morgan, ed., E. Christian Kopf, translator (London: Arktos, 2013), p. 8.

8 Ibid., p. 34.

9 Ibid., p. 35.

10 Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf. ‘Jubiläumsausgabe anläßlich der 50. Lebensjahres des Führers’ (München: Zentralverlag der NSDAP, 1939), p. 505 (English translation from: Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (My Struggle). Ralph Manheim, translator (London: Pimlico, 1992), p. 466.)

11 Carl Schmitt, State, Movement, People, Part IV: ‘Leadership and Ethnic Identity as Basic Concepts of National Socialist Law,’ Simona Draghici, translator. Posted on 24 July 2017 in North American New Right, philosophy, politics, translations, https://www.countercurrents.com

12 Heinar Schilling, Weltanschauliche Betrachtungen (Braunschweig: Vieweg Verlag, 1936), pp. 10–16.

13 Dr Gustav Franke, Vererbung und Rasse: eine Einführung in Vererbungslehre, Rassenhygiene und Rassenkunde (München: Deutscher Volksverlag, 1938), p. 97 (translation courtesy of Dr Tomislav Sunić).

14 Hitler, Mein Kampf (1939), p. 287.

15 Ariosophy was, in its various manifestations, a combination of völkisch ideology, occultism, and a specifically Germanic interpretation of Theosophical currents.

16 Eric Kurlander, Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), p. 69.

17 In his 2007 book Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a New Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), historian and political theorist Roger Griffin posited the idea that ‘palingenesis’ was a core facet of fascist and ultranationalist political movements.

18 Walter Benjamin, Walter Benjamin Selected Writings Volume 2 Part 2 1931–1934, Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith, eds, Rodney Livingstone and others, translators (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), p. 520.

19 Ibid.

20 August Sander and Alfred Döblin, Antlitz der Zeit. Sechzig Aufnahmen Deutscher Menschen Des 20. Jahrhunderts (Munich: Transmare Verlag, 1929), quoted in David Mellor, ed., Germany the New Photography 1927–1933 (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978), p. 56.

21 Matthias Uecker, ‘The Face of the Weimar Republic: Photography, Physiognomy and Propaganda in Weimar Germany’, Monatshefte 99:4 (Winter 2007), 481.

22 Claudia Schmölders, Hitler’s Face: The Biography of an Image (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), pp. 3–4.

23 Christian Zentner and Friedemann Bedürftig, eds, The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (New York: Da Capo Press, 1997), p. 437.

24 Besides Hoffmann, only a limited number of photographers were allowed access to ‘officially’ photograph Hitler; these included Hugo Jäger (1900–1970) and Walter Frentz (1907–2004).

25 Wolfgang Brückle, ‘Face-Off in Weimar Culture: The Physiognomic Paradigm, Competing Portrait Anthologies, and August Sander’s Face of Our Time’, Tate Papers 19 (Spring 2013), http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/19/face-off-in-weimar-culture-the-physiognomic-paradigm-competing-portrait-anthologies-and-august-sanders-face-of-our-time

26 Erich Retzlaff, ‘Farbige Bildnisphotographie’, in Eduard von Pagenhardt, ed., Agfacolor das farbige Lichtbild. Grundlagen und Aufnahmetechnik für den Liebhaberphotographen (München: Verlag Knorr und Hirth, 1938), pp. 20–23.

27 Ibid., pp. 20–21 (author’s translation).

28 Retzlaff served on the Western Front from 1917–1918 as a machine gunner and was shot through the hand during action. He received the Iron Cross (second class) for bravery under fire.

29 These biographical details are drawn from an interview with Erich Retzlaff. ‘Erich Retzlaff to Rolf Sachsse’, 8 December 1979, interview, Diessen/Ammersee, Bavaria, Germany (courtesy Rolf Sachsse).

30 Rolf Sachsse, ‘Traditional Sculpture in Modern Media’, in Christopher Webster van Tonder, Erich Retzlaff: volksfotograf (Aberystwyth: Aberystwyth University School of Art Press, 2013), 15–17.

31 Vömel ran Galerie Flechtheim on the Königsallee nearby Retzlaff’s first studio. After 1933, Alfred Flechtheim, who was a Jew, left Germany. Vömel took the gallery over and it was re-named Galerie Vömel. After Flechtheim arrived in London, Vömel continued to communicate with him and supply him with art for his new gallery in England.

32 Lendvai-Dircksen was awarded a prize following an exhibition of her photographs of peasants in Frankfurt in 1926. This enthusiasm for her peasant studies stimulated her increasing focus on this aspect of her practice. See Anne Maxwell, Picture Imperfect: Photography and Eugenics, 1879–1940 (Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2008), p. 194.

33 Lendvai-Dircksen’s first published images of peasants appeared in an article titled ‘Volksgesicht’ in the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, 39:11 (1930), pp. 467–68. Interestingly, the commercial work of Retzlaff and Lendvai-Dircksen appeared together in an article entitled ‘Eine Fundgrube für deutsche Modeschöpfer’ — Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung 42:30 (1933), 1084. During the Third Reich, their racial-physiognomic work would be reproduced together many times in a variety of books and magazines. Retzlaff claimed he had once travelled to Lendvai-Dircksen’s studio to meet her, but she had been away at the time and the meeting had never taken place (Erich Retzlaff to Rolf Sachsse, interview).

34 Hans Friedrich Karl Günther (1891–1968) was a race scientist whose publications on the racial makeup of the German and European races earned him the nickname Rassengünther (race Günther). Adolf Hitler was certainly influenced by his work, owning six of his books in his personal collection. See Timothy Ryback, Hitler’s Private Library: The Books that Shaped His Life (New York: Knopf, 2008), p. 110.

35 Retzlaff was a pre-1933 member of the NSDAP. His membership card (number 1014457) is dated 1.3.1932 and it is clear from this card that he maintained his membership throughout the war, with the last renewal being on 8 June 1944 (Bundesarchiv, document reference R1–2013/A-3208).

36 Anon., The Quarterly Review of Biology 6:4 (December 1931), 476.

37 Erich Retzlaff, Die von der Scholle and Menschen am Werk (Göttingen: Verlag der Deuerlichschen Buchhandlung o.J., 1931).

38 For example, Retzlaff’s work was used extensively in the Blauen Bücher series by the Karl Langewiesche Verlag. These books were photographically illustrated texts on a variety of German subjects such as traditional costumes, churches, and architecture.

39 Wilhelm Freiherr von Müffling, ed., Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (Munich: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1933).

40 This coalition was intended to ‘temper’ Hitler’s power and the NSDAP influence. Appointments to the cabinet included non-NSDAP representatives such as Franz von Papen as Vice-Chancellor and Alfred Hugenberg (DNVP — the Deutschnationale Volkspartei or German People’s Party) as Minister of Economics. In 1933, von Papen allegedly quipped to a political colleague; ‘No danger at all. We have hired him for our act. In two months’ time we’ll have pushed Hitler so far into a corner, he’ll be squeaking.’

41 Foreword, Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (1933).

42 Others included (but were not limited to) Philipp Bouhler, Wilhelm Brückner, Otto Dietrich, Hans Frank, Hans Hinkel, Adolf Wagner, and Franz Xaver Schwarz.

43 Erich Retzlaff to Rolf Sachsse, interview.

44 Erich Retzlaff and Barbara Lüders, Komm spiel mit mir. Ein Bilderbuch nach farb. Aufnahmen (Berlin: Metzner Verlag, 1943).

45 Erich Retzlaff, Das Gesicht des Geistes (Berlin: Alfred Metzner Verlag, 1944).

46 Erich Retzlaff, Länder und Völker an der Donau: Rumänien, Bulgarien, Ungarn, Kroatien (Vienna: Andermann Verlag, 1944).

47 In a speech at the Sportpalast Berlin on the 18 February 1943 and with Germany deeply affected by the catastrophe of Stalingrad, the firebrand propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (1897–1945) famously called for ‘Totalen Krieg’, i.e., total war, in which all resources of the state would be committed to the war effort.

48 Retzlaff had been a useful photographer for the regime. As noted here, his work had been reproduced widely in propaganda contexts in political journals and popular magazines throughout the 1930s and 1940s. He had almost certainly received commissions from the Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda). Unfortunately, the Bundesarchiv file (R 56-I/257 — Reichskulturkammer — Zentrale einschließlich Büro Hinkel, Korrespondenz mit Fotograf Erich Retzlaff) is currently misfiled/lost.

49 See for example, Christopher Webster van Tonder, ‘Colonising Visions: A Physiognomy of Face and Race in Erich Retzlaff’s book “Länder und Völker an der Donau: Rumänien, Bulgarien, Ungarn, Kroatien”’, PhotoResearcher 23 (Spring 2015), 66–77.

50 Slip note inserted into Das Gesicht des Geistes (author’s translation).

51 Susan Sontag, Under the Sign of Saturn (New York: Straus & Giroux, 1980), p. 96.

52 Erich Retzlaff, Das Geistige Gesicht Deutschlands (Stuttgart: Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1952), p. 27 (author’s translation).

53 Gerhart Hauptmann, introduction, Das Gesicht des Geistes (author’s translation).

54 See for example Wolfgang Brückle, ‘Erich Retzlaff’s Photographic Galleries of Portraits and the Contemporary Response’, in Webster van Tonder, Erich Retzlaff: volksfotograf (2013), pp. 18–33.

55 Of the twenty names listed, three would commit suicide at the end of the war in despair or in order to avoid capture.

56 For information on the artist lists and so-called ‘Führer’ lists see for example: Maximilian Haas, ‘Die Gottbegnadeten-Liste’ in Juri Giannini, Maximilian Haas and Erwin Strouhal, eds, Eine Institution zwischen Repräsentation und Macht. Die Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien im Kulturleben des Nationalsozialismus (Vienna: Mille Tre Verlag, 2014).

57 Richard T. Gray, About Face: German Physiognomic Thought from Lavater to Auschwitz (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004), p. 368.

58 Hermann Burte, ‘Intellectuals Must Belong to the People’, a speech delivered in 1940 at the meeting of the poets of the Greater German Reich. Quoted in George L. Mosse, Nazi Culture: Intellectual, Cultural and Social Life in the Third Reich (London: W. H. Allen, 1966), p. 143.

59 Hans F. K. Günther, The Racial Elements of European History (London: Methuen, 1927), p. 54.

60 Editor’s note from Das Gesicht des Geistes (author’s translation).

61 Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886–1954). The film was made at the AEG plant in Berlin on 20 February 1942, and featured Furtwängler conducting the Reichsorchester in a Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) concert for ordinary working-class people. Jonathan Brown, Great Wagner Conductors: A Listener’s Companion (Oxford: Parrot Press, 2012), p. 664.

62 Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (the Master-Singers of Nuremberg) was the Wagner opera most carefully exploited by the National Socialist state, presented as it was as the symbolic dramatisation of a German renewal.

63 The term Gesamtkunstwerk refers to a ‘total work of art’ and was used by Wagner to signify the aspiration of a theatrical drama that brings together all forms of art.

64 Veit Harlan (director), Kolberg, Ufa Filmkunst GmbH, Herstellungsgruppe Veit Harlan, running time 110 minutes, release date 30 January 1945.