4. Photography, Heimat, Ideology

© Ulrich Hägele, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202.04

Heimat is an idyll, Heimat is the earth, Heimat is tradition — and Heimat is work. But the term is problematic. Heimat is historically a difficult notion to decode as its meaning has shifted significantly over the years. Heimat is a ‘chameleon,’ according to Hermann Bausinger: the idea of Heimat links to ‘the idea of an emotional relationship that is constant; but this constancy could only ever be a reflection of specific times, because the notion of Heimat itself changed its hue, indeed its character and its meaning again and again.’1 The Grimm dictionary defines Heimat as ‘land or just the land in which one is born or has permanent residence.’2 Heimat was thus linked to a geographical area and to the agricultural structure of a rural world characterized by agriculture. Heimat also had a traditional social custom in this context. Because the link to the rights of Heimat were acquired through birth, marriage, or through an official position for life: if one went into the world and became impoverished, the extended Heimat community was notionally obliged to welcome one’s return. Heimat became synonymous with rootedness, family, home, and farm. In contrast, the notion of an urban Heimat has long remained outside of such imaginings. The cities represented the opposite of Heimat: anonymity and mass concentration, mobility and rapid change, poverty and misery — the rootlessness of a life beholden to the capitalist system.

Heimat as a term is typically German. In most other languages there is no specific equivalent. Since its origination in the early nineteenth century, the understanding of Heimat changed, particularly in the period after 1871 when the German Empire prospered politically, economically, socially, and culturally. These changes were self-evident across the new notion of German nationhood. In view of the topographical patchwork on the map, which was now to be woven into a whole, Heimat in the national context remained a utopia that one could dream of, which was, however, a long way off. Moreover, Heimat was diametrically opposed to modernity. Above all, the bourgeois circles in the metropolitan centres and industrial regions now raised the notion of Heimat to an ideal, which was to stand in opposition to the ever-advancing modern age and the associated loss of values from the past.

Heimat and the Foundation of National Meaning

Starting from the traditional concept of Heimat based on one’s place of birth, Heimat was stylized as a contrasting model to modernity, that is, to the industrialized world. Hermann Bausinger characterised this as a ‘Kompensationsraum’, the notion of Heimat for (specifically) the bourgeoisie, as being above all a complex reflex reaction to a nostalgic feeling of loss as well as the foundation of an emergent identity. Heimat was linked to a timeless and mostly romantically presented set of ethical and moral standards of value, all forming part of a strategy to seek to neutralise elements of anything considered ‘foreign’ and ‘modern’.3

The broader notion of Heimat served as part of a bourgeois-intellectual resistance against a general deracination — against the ‘specifically metropolitan extravagances of social division, whims, affectations’ , as the sociologist Georg Simmel opined in a study on the metropolis of Berlin in 1903.4 To this end, around the turn of the century, several platforms were formed, such as the Lebensreformbewegung (Life Reform Movement) and the Naturschutzbewegung (Conservation Movement). And the aim of early Heimatfotografie (Homeland photography) can be explained by these common denominators: the visual preservation of traditional culture as well as the desire to form an identity for the politically new.

This identification of Heimat and rural folk culture also presented an image of national unity to the outside world. A prerequisite to form this overarching conceptual representation of a unified whole was a broad familiarity with the respective costumes, representations, and iconography of the nation. For the dissemination of images, photography was considered the predestined medium. With this tool, a large number of significant and relevant subjects could be documented in a short space of time. Above all, the Heimatschutzbewegung5 (Homeland Protection Movement) enthusiastically adopted the photographic form to spread the notion of Heimat.

Oscar Schwindrazheim summarised his thoughts on the potential role of photography in this context in a text written in 1905. In this essay, he criticised the influence of metropolitan culture on art and folk art alike, as a detrimental ‘alien influence’, and stated that treasures that had survived from ‘the central Germanic culture, from ancient times to the present in the farmhouse, smaller town house, peasant art and petty bourgeois art’ were now, ‘defenceless, abandoned and left to ruin’. This, he continued, was countered by the Heimatschutzbewegung, which had used photography as a means of capturing an encounter with the ‘ancient variety of folk traditions’ in villages and thus reach an ever-growing number of Germans. Photography’s role in enthusing these ‘supporters of the folk’ therefore remedied past shortcomings in representation. Schwindrazheim’s vision was conservative. His interest was the representation of a pure, beautiful, and authentic rural world.6

Whilst Schwindrazheim’s interpretation of the potential of photography was very much one that favoured an aesthetic focussed on ethereal and purely idyllic images of the Heimat, Paul Schultze-Naumburg developed a visual process in which ‘the poetry of our villages’ of the Heimat might be identified in relation to progressive urbanization. Chairman of the Deutschen Bundes Heimatschutz (German Federation for Heimat Protection) and founding member of the Deutschen Werkbundes (German Work Federation), he intended to divorce the ‘good’ from the ‘bad’, the old from the new, via the path of visual confrontation between example and counterexample, presented under the mantle of quality craftsmanship. With regard to cosmopolitan art and its effect on an indigenous way of life, he spoke of a ‘threatening disease’ that had seized ‘all parts of our culture’. Schultze-Naumburg, in his polarizing view, used a terminology that classified modernism as reprehensible and, accordingly, as something that was in opposition to traditional, ethnic values. He wrote of a ‘dreary poverty and desolation’, of ‘degeneration’ and an urban ‘avarice, which manifests as a dreadful blind greed’. On the other hand, he set the ‘characterful and true beauty’ of the rural, which had ‘proven itself through the centuries as the standard’.

Fig. 4.1a and 4.1b Eine ‘gute’ und eine ‘schlechte’ Bank als visuelle Gradmesser (A ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ Bench as Visual Indicators), reproduced in Heinrich Sohnrey, Kunst auf dem Lande (Art of the Countryside) (Bielefeld/Leipzig/Berlin: Velhagen & Klasen, 1905), p. 182. Public domain.

Figures 4.1a and 4.1b are an example of this comparative process. It is the ‘good bench’ and the ‘ugly bench’: on the one hand, a traditional seating arrangement nestles around a gnarled linden tree whilst echoing the undulations of the landscape; it is contrasted with an industrially manufactured piece of furniture, with cast-iron stand and board-like seat.7 Schultze-Naumburg objected in particular to the choice of building materials: for him, iron and steel were the epitome of industrial mass-production: a mirror image of the growing metropolises and industrial areas in direct opposition to a rural ‘naturalness’. Ultimately, the Heimatschutzbewegung was very much up to date in terms of the contemporary propaganda that it employed. Two very modern media were used to document, disseminate, and popularize the ideas of the movement: the camera, as a recording device, and the magazine, for reproduction. In this sense, the self-proclaimed guardians of this endangered cultural heritage were trying to motivate broader sections of the population to cooperate in a kind of collective visual rescue operation.

During the 1920s, a discourse emerged that was focussed on the evolution of German society and this gathered momentum, not least because of the lost war. The question of the origins and capacities of the people themselves became a central theme of this inquiry in order to determine how an individual’s provenance affected their contribution to the modern era. August Sander’s large-scale photographic project ‘People of the 20th Century’ was very much a manifestation of this era’s search for new interpretations. About forty-five portfolios were planned, each of which was to be accompanied by twelve photographs, beginning with ‘the peasant, the earth-bound man […], all the strata and occupations up to the representatives of the highest civilization and down to the idiot’.8 Sander, as a creative photographer, carefully directed each image, often setting the protagonists against striking backgrounds or including conspicuous paraphernalia or objects, which often had a function relevant to their occupation. His principle motivation was the observation of milieus.

Sander began his project with the peasant and was thus, as Karl Jaspers observed, working at the height of the anthropologically dominated zeitgeist, which was ideologically overlaid by the notion of a special connectivity to the soil. However, Sander’s photographs present the costume as a relic, something that was, in the main, only cherished by old women in the countryside. Above all, his juxtapositions bring to light the stark social differences that were commonplace in rural areas. Sander’s work can be interpreted from two points of view. On the one hand, his unmistakably social-documentary portraits convince with their use of a modern and transformative approach to image making, traceable to Dadaist approaches of the early twenties. His pictures are social frescoes,9 which certainly hint at nineteenth-century genre painting. At the same time, he expanded the range of motifs by including aspects of urban culture. His objective approach to image-making relates Sander’s work to the New Vision and New Objectivity. On the other hand, the social-documentary aspect should not be overstated, because Sander proceeded, as did most other artistically ambitious ethnographic photographers, from a peasant archetype by which the interpretation of his sitters was constrained.10 Accordingly, his photographs reflect a ‘medieval hierarchy of stances,’11 a somewhat cloying conception of society: Sander does not show his workers in the Marxist sense, as proletarians who can be exploited through alienating assembly line work, but as people who accord to a somewhat romanticised ethos of skilled artisans. The photographer’s work was produced, as Ulrich Keller noted, ‘forcibly, in an ideologically charged field’.12 August Sander’s pictures move in an intermediate domain of traditional and modern Heimat photography. Some of them are clearly socially critical — one reason why the National Socialists proscribed Sander from practicing as a photographer.

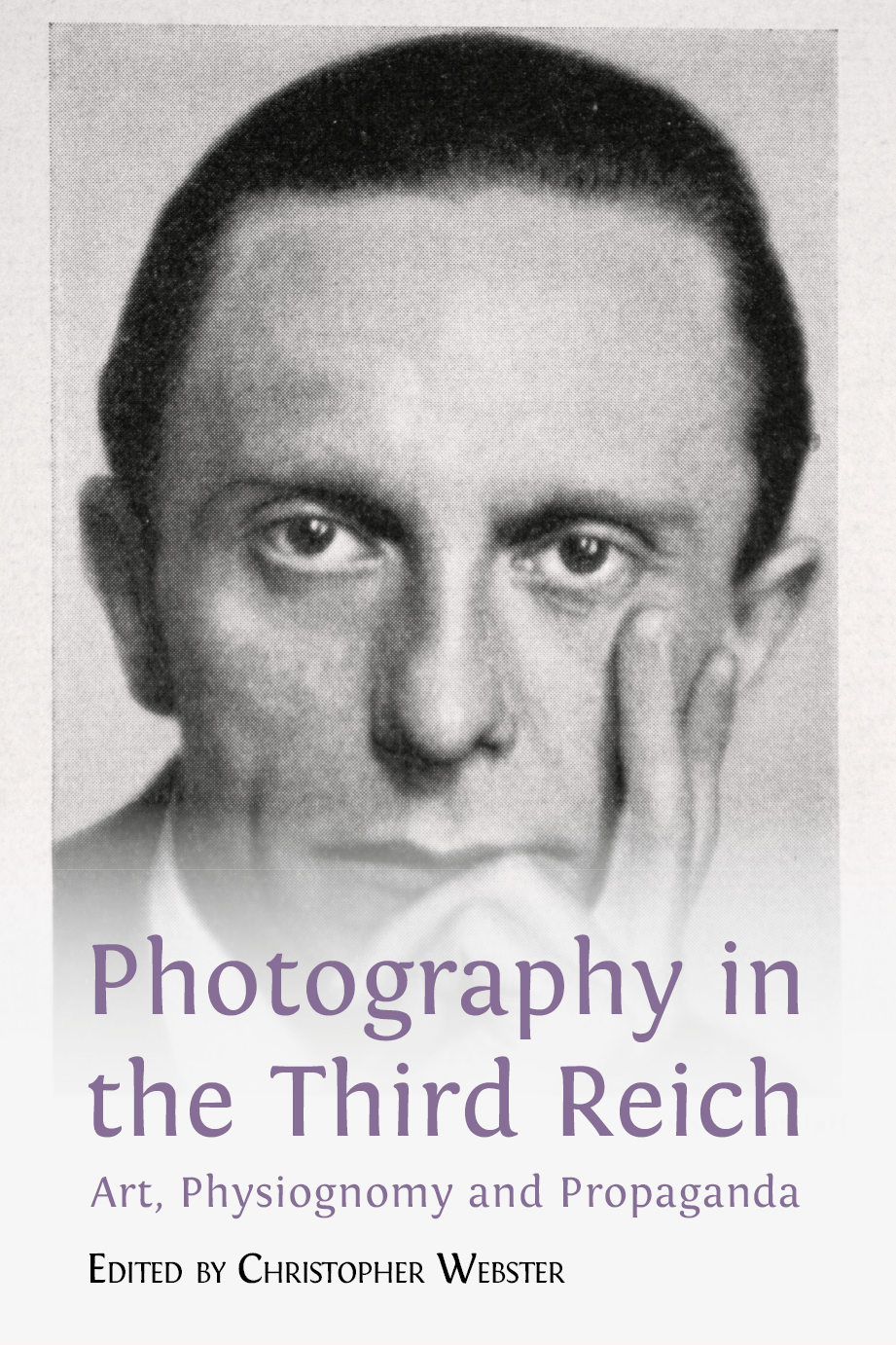

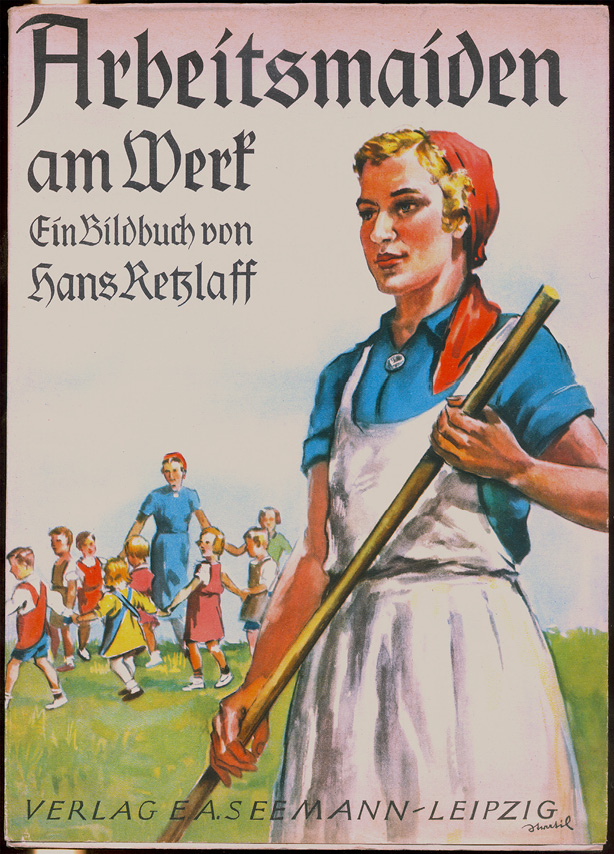

The National Socialists fully understood the significance of photography and film as carriers of a message to popularise their policies — as early as 1933, Joseph Goebbels had demonstrated his grasp of the power of photography, suggesting that the photograph should be given priority over the word, especially in propaganda.13 Between 1933 and 1945, images such as Willy Römer’s presentation of a precarious Heimat before the First World War were considered undesirable. Indeed, most of the practitioners of the New Photography chose, or were forced, to emigrate. The photographers who stayed remained committed to the regime and divided the visual-journalistic ‘cake’ among themselves: Heinrich Hoffmann was responsible for the Führerbild and the visualization of the NSDAP. Erna Lendvai-Dircksen continued to publish illustrated books about the people’s Heimat across various regions of the German Reich, as well as images of children and the dramatic construction of the autobahns. Hans Retzlaff concentrated on depicting traditional rural costumes, which had already disappeared almost completely from everyday life by the 1930s, and published a picture book about the Arbeitsmaiden am werk (Labour Service Women at Work). Finally, Paul Wolff and his ‘Leica Photography’ mimicked the modernist ‘fig leaf’ of the new colour technology (see Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.2 Cover image from Hans Retzlaff, Arbeitsmaiden am Werk (Labour Service Women at Work) (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann, 1940). Public domain.

Völkische Heimat

The main photographic protagonist of the so-called völkischen Heimat was Erna Lendvai-Dircksen. Her seminal work was the volume Das deutsche Volksgesicht (The Face of the German Race) published in 1932. Besides an introductory text by the author and some descriptions relating to photography, the book contained 140 photographs, beautifully reproduced as copper plate photogravures. Her work focused in particular on the portrait of the individual — group shots, pictures of families, or a mother with her children are not featured in the volume, and there are few people from urban areas: ‘The urban man has abandoned the mother soil and a natural life’.14 Accordingly, Lendvai-Dircksen focused on depicting a rural world whose people are the epitome of the Volkskörper15 or body of the nation, and she is one of the few contemporary Heimat photographers who tried to substantiate her working method in theoretical terms. The ethnic German Volk were positioned as the antithesis of those merely of the state or city dwellers: ‘One talks of the “people of the land” in contrast to the “city dweller” and that is to say what is meant. To talk of the Volk is to speak of a unified natural community, with its roots anchored in the soil of the landscape. It is a one-of-a-kind entity that, being as simple as it is organic, is not accessible to a quick, superficial understanding.’16 In a contribution to the 1931 volume Das Deutsche Lichtbild (The German Photograph) she struck a blow for the national-conservative Heimatfotografie, which had been popularised at the turn of the century by Paul Schulze-Naumburg and Oscar Schwindrazheim as part of the Heimatschutzbewegung. The narrative is concerned with notions of worthiness, harmony, beauty and culture, as elements intrinsically bound to the ‘Ur-landscape’.17 Participating in the 1928 Pressa exhibition in Cologne, Lendvai-Dircksen had already outlined these notions in the context of a presentation of her work to her colleagues from the GDL or Gesellschaft Deutscher Lichtbildner (Society of German Photographers).18

The Stuttgart film and photo exhibition the following year, which acted as a gathering for the entire European photographic elite, was either given the cold shoulder by Lendvai-Dircksen or she was not invited to participate, perhaps because she had defined her photography as outside of a cohesive internationalist vision: ‘In exhibitions, the best achievements clearly show what photography has to say for a people; English, German and French photography, as far as they are ethnically based, can be easily distinguished’.19 In contrast to this approach to an ethnic photography of the Volk, Lendvai-Dircksen suggested archly, the photographers of the New Objectivity and advertising were firmly positioned as representatives of the cosmopolitan, urban centres: ‘These premature miscarriages of a one-sided intelligence must be confronted by the rooted, vital nature of true originality, which knows how to present a true view of things and is able to counter the creeping pessimism in a detoxifying way’.20 Two years before Hitler came to power, this derogatory remark was to presage the path that photography would take in the National Socialist state.21

Erna Lendvai-Dircksen came from a rural farming background and grew up in Wetterburg, Hessen. Her career as a photographer was typical of the time: first she studied painting (1903–1905 in Kassel), then she pursued an apprenticeship as a photographer in Berlin that she never completed. In 1916, she opened her own portrait studio in Charlottenburg. At first, in terms of geography, the structure of her book Das deutsche Volksgesicht seems somewhat strange. Starting with Frisia and the Frisians, Lendvai-Dircksen moves on, seemingly at random, through the book to Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg, Masuria, Spreewald, Bückeburg, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden. The sequence of works concludes with Hessen. In this dramaturgy there are aspects that may in fact refer to the biography of the author — one part of her heritage had its origins just where the book begins: ‘I did not discover the German farmer when he became the “fashion”. The Dircksens are of the oldest Frisian blood, and every hike between the Elbe and the Weser estuary is like a homecoming for me’.22

Furthermore, the photographer seems to claim a connection between this portrayal of human types (for instance, the photograph of a junge Bäuerin aus dem hessischen Hinterland (Young Farmer’s Wife from the Hessian Hinterland) and the established artistic tradition of Holbein, Cranach, and Dürer, presenting comparisons on a double page (the technique of visual doubling): young and old, daughter and mother, husband and wife. The only objectivation, which Lendvai-Dircksen partially thematises in detail, is the representation of clothing, which in turn brings an ambivalent attitude to light: on the one hand, she presents many portraits that include traditional costumes, the symmetrical composition of which seems to coincide with the criterion of photographic New Objectivity. At the same time, the portrait of the Jungmädchen aus den Hagendörfern (Young Girls from the Hagen Villages) conforms to a more stringent compositional expression. The dark hues and blurred, unidentifiable background are two major pictorial features in Lendvai-Dircksen’s illustrated books, as well as the juxtaposition of figures over a double page (see Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3 Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Zwei Generationen gegenübergestellt (Two Generations Compared), 1932, reproduced in Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (Face of the German Race) (Berlin: Drei Masken Verlag, 1934), pp. 140–41. Public domain.

An almost perfect symmetry is also evident in the picture of the Spreewalderin im Brautputz (Woman from the Spreewald in Bridal Dress). In this motif, another characteristic of her publication technique is also recognizable: Lendvai-Dircksen often juxtaposed a page of text with a picture, in which she sometimes emotively responded to the picture’s theme:

Even if the folk costume traditions do inevitably decline and fade from urban fashion trends, there is still much to be understood about the ceremonial character of this ancient aesthetic. […] One has to admit it about these daughters of the Spreewald: They know how to move the body beautifully. There is nothing slack or synthetic, only the absolute dependability of the natural.23

The description did not attempt to hide the fact that traditional costumes had already largely begun to disappear from the countryside by the 1920s, but it addressed this development openly, albeit with an unmistakeable undertone of regret. In contrast, her contemporary, the Heimat photographer Hans Retzlaff, tended to carefully eliminate any reference to modern life in his pictures and captions relating to these costumes. He thus focused on a stylized image of the past, which he also sought to suggest was the model approach of modern living: a life lived close to the ancestral soil.

In her accompanying texts, Lendvai-Dircksen sometimes treads a fine line between a commentary and a waspish critique — this is clearly evident in the example she presents of an older farming couple from Hessen.

Fig. 4.4 Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Kranke Frau (Sick Woman), 1932, reproduced in Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (Face of the German Race) (Berlin: Drei Masken Verlag, 1934), p. 91. Public domain.

Apparently, the farmer had, in earlier years, demanded too much physical work of his delicate wife. The woman became ill, partially paralysed, and ultimately lived in continuous agony. As the photographer stated about the husband: ‘Is he innocent or guilty for his wife’s broken life?’24 When discussing the image of the woman, Lendvai-Dircksen states:

For 30 years she has been sitting on a low stool, growing ever lamer. This terrible wasteland of years has worn down both her mind and her soul. She did not even notice me photographing her. A woman’s fate! One of many! She had a robust, almost overpowering man; what did he know about the amount of hard work a young woman’s body can withstand when the children come one after the other… The tender woman was broken, […] an obstacle, waiting for death to deliver her.25

The text is highly moralising, sometimes even accusatory. This form of critical presentation thus relates to the approach and published practice of contemporary anthropological-medical racial hygienists. In magazines such as Volk und Rasse (People and Race, etc., images of mentally ill people or of Sinti, Roma, and Jews, for example, were visually staged and provided with captions that rejected and often demeaned the subjects. These ignominious commentaries were accompanied by the visual separation of the groups concerned from representations of the bodies of the ‘healthy’. Certainly, for Lendvai-Dircksen, the Volkskörper consisted of her rural contemporaries: ‘Here is the world, here is life and growth. The soil is really Mother Earth’.26 By accusing the farmer in visual and textual terms of mistreating his wife, a stigmatisation occurs where the man is seen to fall outside of the (moral) ‘norm’ of the Volkskörper.

Lendvai-Dircksen’s approach follows a certain pattern. Significantly, the protagonists are represented as inevitable ‘victims of fate’27 and not as autonomous individuals. In most of the pictures, the models don’t look into the camera; their gaze is rather out of the frame, as if they have something to hide. The older people, thematically the largest group of her photo portraits, mostly appear to be careworn and marked by their years. With the minor exception of a few images of the elderly, it is the photographs of children who are the only ones arranged to look directly into the camera. Lendvai-Dircksen photographed the young females in a manner that was straightforward and slightly from above, this tended to emphasise a passive and expectant role. When photographing the younger males, she set the tripod somewhat below the face, which in turn suggested a self-confidence and mental strength in her subjects. The pictures often show a close-up view of (German) faces furrowed by life, of delicate female youth, and a plethora of traditional costumes (see Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.5 Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Junge Schwälmer Bäuerin (Young Swabian Peasant Woman), 1932, reproduced in Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (The Face of the German Race) (Berlin: Drei Masken Verlag, 1934), p. 235. Public domain.

The foreign and ‘the other’ have no place. The photographer thus framed a traditional interpretation of the ethnic Heimat, which she herself described as a quest to reconstruct an archetypal image, an Urbild,28 a picture that in turn refers to the Romantic period or to the painterly-figurative peasant painting of artists like Hans Thoma (1839–1924). In this context it is hardly surprising that Lendvai-Dircksen relied on the elderly as the main subject matter for her book. Of the one-hundred-and-forty portraits, fifty-five are older men and women, twenty are young women, and only ten are young men. In the concluding sentence of the book, Erna Lendvai-Dircksen wrote: ‘Only in the perfect circle of a whole life do we witness its whole sum; and as an old tree shows most clearly the individual peculiarities of its kind, so does the old man who becomes the most distinctive type, the visual biography of his ethnicity.’29 In Lendvai-Dirksen’s work, as in the work of the other protagonists of this ethno-cultural Heimatfotografie, a significant aspect becomes clear in the dramatic construction of these staged photographs: men, women, and children are either shown as individuals of a type or separated according to gender. After the outbreak of war, save for the elderly, there are few men represented in this photographic milieu.

In an excellent essay, Claudia Gabriele Philipp describes Lendvai-Dircksen’s photographs as ‘Nazi ideology in its purest form’.30 However, when reflecting on the photographer’s early response to her own work, as well as the photographs themselves, one would be doing the photographer an injustice to categorise her entire working portfolio within the category of racial photography. Her way of taking photographs was initially multi-layered and was by no means entirely counter-propositional to the ‘overarching utilitarian approach’ of photographic New Objectivity. Her ‘great love for monumentality’31 does not necessarily contradict this ‘modern’ photography either.32 Some of her portraits and images of plants from the 1920s, but also her later landscape and architectural photographs, undoubtedly fulfil the criteria of the New Vision: an extreme close-up approach, full image detail and optical clarity, as well as the use of an axially symmetrical image composition.33 Nevertheless, Lendvai-Dircksen was an opportunistic photographer who willingly placed her art at the service of the National Socialist regime. As Hannah Marquardt’s research revealed, the photographer received financial support for her extensive travels from the Reichsschrifttumskammer (Reich Chamber of Literature), a sub-department of Dr Joseph Goebbels’ Reichskulturkammer (Reich Chamber of Culture). Lendvai-Dircksen proceeded to develop her work in series and produced a broader overview of her leitmotifs, including corresponding landscape pictures of the region encompassed by each specific publication. Finally, she was able to assemble her own publications from a large pool of visual material and also to contribute to other publications — for example, the article ‘Volksgesicht’ in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung34 in 1930 contained variations of those photographic illustrations that were shown in her later monograph Das deutsche Volksgesicht. She also worked with well-known figures in the National Socialist establishment, such as Fritz Todt and Franz Riedweg. Riedweg, who was primarily responsible for recruiting volunteers for the pan-European and anti-Bolshevik Germanic SS, wrote an epilogue for her volume of photography entitled Das deutsche Volksgesicht. Flandern that was centred on the ‘Germanic’ look of the Flemish.35

In terms of her own methodology, Lendvai-Dircksen was initially critical of the approaches of photographers and researchers whose work proceeded specifically from the work of the race scientist Hans F. K. Günther, asserting: ‘It is not achieved with race-psychological comparisons or with cranial measurements alone; life is something vibrant, and its meaning emerges from this context’.36 Elsewhere, she noted, ‘the emergence of national and ethnic folk traditions as part of a living community’ had ‘nothing to do with the racial form’.37 By association, Lendvai-Dircksen’s studies of the human face with a so-called search for the psychological soul, suggests a certain closeness to the work of Ludwig Ferdinand Clauss. Accordingly, her photographs were regarded as suitable illustrations for magazines relevant to the field of racial studies38—Günther also published some of her pictures.39 In addition, her publications also presented National Socialism with a ‘liberal’ veneer, and a range of illustrated books were published in the run-up to the 1936 Olympics.40

The Heimat Front

After 1933, völkisch photography or Heimat photography41 was not intended to be an overt depiction of documentary reality, but rather it represented a construction of reality that accorded to the ideals of National Socialist ideology. Accordingly, when looking through the illustrated books, the impression received is that agricultural and manual labour in the German Reich was carried out exclusively by striking-looking peasant types and blonds in traditional costumes in large families with many children — all doing humble work that knew no technical aids. But the reality of life in the countryside was in obvious contradiction to this, for the National Socialist regime intensified the mechanization and motorization of the agricultural economy. The policy of land consolidation was used to increase production so that, in the event of war, food supplies could be secured in an autarkical manner. Where there were once relatively untouched landscapes, four-lane motorways now appeared; initially this did not much benefit the stated aim of increasing the mobility of individual families, but was, it has been argued, linked to aspects of the strategic considerations of the war planners.42

Hans Retzlaff made a considerable contribution to this ideologisation of documentary photography with his photographs of traditional costumes.43 Despite — or precisely because of — the discrepancy between everyday reality and photographically staged reality, his photographs were not only published in large numbers in illustrated books and in magazine articles. They also served — when sold to schools, universities and other educational institutions in the form of slides and paper prints — as teaching objects to illustrate and convey a representation of rural life. The images of ‘folk’ photographers were thus the starting point for more scientific interpretations in the spirit of National Socialist ideology. For example, the headdress of the ‘Spreewaldkindes aus Burg in Sonntagstracht’, taken by Hans Retzlaff in 1934 and acquired by the Tübingen Institute for German Folklore, according to one contemporary, represents the ‘living essence’ through which ‘the rural German, yes, even a sense of Germanic tribal consciousness’ is particularly well expressed.44

Fig. 4.6 Hans Retzlaff, Spreewaldkind aus Burg in Sonntagstracht (Spreewald Child from Burg in Sunday Costume), vintage silver gelatin print, 1934, courtesy of Archiv Ludwig-Uhland-Institut für Empirische Kulturwissenschaft, Universität Tübingen. Inv.-Nr. 5a383.

By disseminating the photographs in illustrated books in the mass media, they ‘served the so-called folk traditions and thus became a political instrument’.45 Reichsarbeitsführer (Reich Labour Leader) Konstantin Hierl apparently appreciated Retzlaff’s style of working and commissioned him in 1939 to compile an illustrated book about the Arbeitsmaiden.46 It was to be his last before the end of the war and at the same time the only one without an ethnographic or folkloristic theme.

Hans Retzlaff’s illustrated book Arbeitsmaiden am Werk (Labour Service Women at Work (see Fig. 4.2) was published in 1940, soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. The ninety-six high-quality intaglio copperplate plates, mostly as full-page images, were intended to provide a more eloquent insight than mere words into ‘the first state school of education for female youth as a sign of faith of a new era,’ as the book’s introduction states.47 The volume thus assumed a political function within the framework of the war planning of the National Socialist regime and the racial ideology of blood and soil. Despite the visual nature of this book, illustrated as it was with the help of professionally crafted photographs as the central feature, the editors were not, apparently, confident enough to rely fully on the power of the pictures alone. This is evidenced by the fact that the illustrations were preceded by a thirty-page introduction by the RAD’s Generalarbeitsführer (General Work Leader) Wilhelm ‘Will’ Decker. Decker’s text is divided into several sections, namely: ‘the idea’, ‘the way’, ‘the form’, ‘the substance’, ‘the service’, ‘the work’, ‘recreation and leisure time’, and ‘the flag’. The last section marks a link to the first plate ‘Raising the flag before the start of the day’s work’. It shows two women in RAD uniform, the so-called ‘working maidens’48 of the book’s title, raising a large swastika flag on a wooden flagpole. In the background are other women giving the Hitlergruß (the Hitler salute).

Hans Retzlaff’s Arbeitsmaiden am Werk is divided into five main topics without this being obvious to the reader at first glance, for example, in the form of the subheadings: ‘daily routine’, ‘agricultural work’, ‘childcare’, ‘camp activities’, and ‘leisure activities’. The series of pictures on agricultural work is interrupted twice by pictures on the subject of childcare, resulting in three series on work and two series of children’s pictures. With only a few exceptions, these are all outdoor shots. In addition, the illustrated book contains three chronological levels, some of which are intertwined: firstly, the six-month service of the young women in training during their stay in the Arbeitsdienst camps,49 learning domestic activities, political education, and excursions, then the daily routine of the morning flag-raising through to early exercise, rollcall, the journey to work, activities at the workplace, as well as leisure, and the activities in and around the camp. Finally, all the rural and agricultural activities of the women were related to the course of the seasons, starting with planting in spring and continuing through the hay harvest in late summer to giving Advent wreaths to farming families as gifts during the Christmas season. The (mostly) portrait-format illustrations are presented in the style of a photo album, with short captions, provided by Else Stein, Stabsführerin (Staff Leader) in the RAD.

The opening sequence already conveys in visualized form the five main characteristics of the Reich Labour Service of the Female Youth (RAD/wJ) within the regime. The images demonstrated that the organization: had a political-propagandistic function (raising the flag); had a strict hierarchy based on the Führerprinzip or leader principle (camp leader versus private); was subject to military drill (standing in rank and file); emphasized the disciplinary strengthening of the body; and each individual was mindful of her feminine role, serving as a part of the supposedly racially homogeneous and cohesive Volksgemeinschaft or ‘the people’s community’.50

Fig. 4.7 Hans Retzlaff, Militärischer Drill (Military Drill), reproduced in Hans Retzlaff, Arbeitsmaiden am Werk (Labour Service Women at Work) (E. A. Seemann, Leipzig 1940), p. 44. Public domain.

The three pictorial chronological levels are partly interwoven. The first section, which begins with three women engaged with early-morning sports, comprises six shots on three double pages. The pictures show the young women alone or in a group and on their way to work by bicycle. This is followed by a sequence of fourteen photographs depicting individual agricultural activities. The picture of a young woman leading a team of oxen onto the field serves to catch the eye: one of the few examples in the illustrated book in which movement is recorded, as the cheerfully laughing young woman walks between the two oxen towards the camera; a farmhouse can be seen in the background.

‘The Image of Baking Bread’ leads into the third chapter: the Arbeitsmaiden with the farm children. The woman sits at the table at lunch with the children; Retzlaff apparently arranged that the table be taken out of the kitchen into the open air for the photographs. The RAD girl gives the infants, or rather, small children, ‘Klaus and Peter’, milk from the bottle and helps ‘Bärbel’ with her schoolwork. The atypical mention of the children by name here contradicts the usual practice of anonymous titles, an approach that is otherwise intended to underline the deindividuation of the individual within the RADwJ.

The following section continues the activities of the Arbeitsmaiden, who are now shown out working in the fields (hoeing beets, planting salads, vegetable harvesting, and so on). The visual leitmotif in this series is the three-quarter portrait ‘Time of Haymaking’ taken from below, on which a young woman carries a load of hay. She smiles and looks out of the picture to the right towards the low sun. Again, light and shadow areas fall on her face and body. A working tool — probably a hay fork — sticks diagonally in the hay, dividing the image field diagonally into a triangle and an irregular square.

Through twenty-eight images on fourteen double pages, the next section visualizes the third and last part of the rural work. An outstanding example with a leitmotif function here is the illustration with the signature ‘In the labour service, the working girl gets to know her beautiful German home’ (see Fig. 4.8).

Fig. 4.8 Hans Retzlaff, Patriarchale Rollenverteilung: ‘Im Arbeitsdienst lernt die Arbeitsmaid ihre schöne deutsche Heimat kennen’ (A Patriarchal Distribution of Roles: ‘In the work service, the young working woman gets to know her beautiful German Homeland’), reproduced in Hans Retzlaff, Arbeitsmaiden am Werk (Labour Service Women at Work) (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann, 1940), p. 87. Public domain.

A woman stands on a mountain meadow with a young mountain farmer. The terrain drops steeply at their feet. The man in the shirt has shouldered a scythe. With a sweeping gesture he points out of the frame of the picture, the woman in front of him standing slightly outside the frame of the image. The background of the scene is marked by a valley that extends to the horizon in the low, mountainous, partly wooded landscape.

The illustration is one of only thirteen examples in Arbeitsmaiden am Werk in which Retzlaff’s image features a man. Whereas most of these representations of men are of older farmers who are seen to be giving these women careful instruction in their work, this specific image does not represent the father-daughter configuration, but rather a young, heterosexual couple that reproduces a traditional and timeless structure in its presentation of gender roles. With his outstretched arm pointing the way, the man is assigned an active role, whereas the woman following him attentively is portrayed as reacting.51 Furthermore, photography is used in a symbolically multi-layered manner in its integration in the overall context of the book. The placement of the man and woman, after the series of pictures about childcare, suggests the reproductive function of the young woman, for whom a future as a wife and mother in an agrarian ideal was clearly intimated through the photographic context. In addition, the mountain landscape crossed by a river not only serves as a grandiose backdrop. The water, flowing through the depths of the valley, remains invisible to the observer. As one of the basic elements of nature, it represents the natural world in contrast to the tamed environment shaped by man. Symbolically, water functions as a sign of life, fertility, and sexuality. In this context, images representing water suggest a small and largely hidden metaphorical reference to the idea of the Volkskörper. At the same time, the (concealed) visualization of fluid, as Uli Linke explains, results in an equally metaphorical connotation: a collective appropriation of the female body.52 In this sense, the picture motif could have remained interesting in journalistic terms up until more recent times — the magazine Heimat 2010 published the photograph of a young woman from Eltville sitting in a dirndl over the Rhine looking down into the valley.53

Fig. 4.9 Dirndl-Heimat in einer Illustrierten (An Illustration of Traditional Heimat Costume), Heimat, September 2010, Heft 9, p. 15. Fair use.

Another potential interpretation is suggested by the iconographic tradition of the picture motif itself. In the person of the mountain farmer we have before us none other than the Grim Reaper, who has personified death since the medieval depictions of the Dance of Death — an assumption that gains added plausibility through the title of the picture on the left side as ‘harvest work’ and the intrinsic theme of cutting inherent to this title. However, a more far-reaching interpretation, where there was a concealed, even subversive reference to the everyday casualties of war in 1940, would be in stark contrast to Retzlaff’s usual photographic image practice. More likely, the photographer wanted to imply the death of the enemy in the war. According to the rhetoric of the pictures, the reaper, represented by the German man, mows down the enemy, whilst the German woman gives new life to the land thus conquered.

Arbeitsmaiden am Werk ends with two sequences of pictures about domestic work in the camp and leisure activities, the latter presented in the form of song recitals, ball games, and excursions. The seasonal chronology ends with the photograph ‘Christmas in the camp’, in which the women are gathered in front of a Christmas tree by the fireplace. The conclusion of the book — and thus also the end of the chronology of the period of service — is marked by one of the young women saying farewell to a farmer’s wife and the entire village: a polite distance is maintained whilst shaking hands and handing over flowers.

The overall concept of Retzlaff’s Arbeitsmaiden am Werk is based on Gustav von Estorff’s volume Daß die Arbeit Freude werde! (When Work Becomes a Joy) from 1938, which was also a political text and included a preface by Reichsarbeitsführer Hierl.54 With fifty-nine illustrations printed in offset, this publication was considerably narrower, but the originators had already conceived of a chronological division of thirds through the various activities (the six-month period of service, the work during the day, and the overall cycle of the year). Although the volume does not end with Christmas singing, it does conclude with a night-time record of a solstice celebration.

Some of Retzlaff’s illustrations correspond to this model down to the last detail. Estorff had already had the RAD women presented standing with their bicycles in an honour-guard formation, with the camp leader sending them off to their working day with a handshake. Estorff’s image is a close-up, whilst Retzlaff chose a slightly more distanced camera position. The press photographer Liselotte Purper also represented the young women in a rather lively light in her reports.55 Her protagonists are shown on a dusty village road.

Fig. 4.10 Liselotte Purper, Arbeitsmaiden auf dem Weg durchs Dorf (Labour Service Women on their Way through the Village), vintage silver gelatin print, 1942, courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

They laugh, wear their hair open and have fashionably rolled their socks over their ankles. There is a pavement in the foreground and, on the left, two village children are perched on a wall. Purper’s picture was created in the tradition of modern photo reportage, which began in the 1920s and aimed to present everyday life as authentically as possible in the media, while at the same time meeting artistic demands — even when working with topics from the rural environment, which otherwise aroused ethnological or folkloristic interest at best.

On the other hand, the photo illustrations in Retzlaff’s ‘Arbeitsmaiden’ appear both thoughtfully constructed and politically compliant, and this is confirmed by the text’s two extensive essay contributions. He focuses on the reproductive factors in the lives of these young women as soon-to-be housewives and mothers, whereby domestic tasks, other work, and physical training form the framework of camp life. However, until the final fulfilment of her duty, the woman is presented as largely asexual; someone who, along with all the other likeminded girls, had to stand by her husband and otherwise had no other needs to express — especially not the desire for male closeness.

As can be seen from Retzlaff’s, Estorff’s, and Purpers’ different approaches, National Socialist photography ultimately cannot be assigned clear and homogeneous design features. In National Socialism, photography might most easily be explained by the question of what it does not show: socially critical themes and day-to-day life, industrialization, and armaments production are as absent as intercultural coexistence in the city and in the countryside. Sinti and Roma, Jews, homosexuals, and people with physical and mental disabilities are at best presented in a stigmatizing, racial-ideological context, such as in the SS’s openly anti-Semitic work Der Untermensch.56 In contrast, the visual language in the context of industrial photography and advertising is often aesthetically up to date, even when measured against international trends of the time. The illustrated books in particular represented a visual niche within the controlled and censored media and publishing apparatus, which stood out from other printed products of that time not least due to their modern typographic design. In the context of the various manifestations of modernism, the National Socialists used progressive methods in media visualization and also in communication, engineering, and armaments, where they were able to present their policies in the right light.

The pictorial tendencies of National Socialist photography can best be characterized under the sign of ‘modernity with a view to a closeness with nature’.57 In concrete terms this resulted in a monumentalization and heroization of people and objects; a typification and idealisation of man and nature; the use of a visual argument through juxtapositions, simplifications, and repetitions. In addition, there were distortions of history in the interplay of image and text.58 While the aspects of monumentalization and heroization, as well as the juxtaposition of images of man in the sense of racial ideology, were reserved for forthright propagandistic illustrations in specific inflammatory writings and for the National Socialist press, the other characteristics are present in Retzlaff’s work Arbeitsmaiden am Werk. In a subtle way, however, this volume also deals with the subject of race: the introduction talks about the ‘Arbeitsmaiden’ embodying ‘the blood values of the Nordic race’. Accordingly, some of the images include stereotypical blonde women and children that might allude to the homogeneous ‘Aryan folk body’ from which everything that was foreign and different had been purged. The women, for their part, according to the text, performed an educational ‘honourable service for their people’ and in the Reichsarbeitsdienst ‘little talk was needed about National Socialism, because the Reichsarbeitsdienst itself was the practical application of National Socialism’.59

The political-propagandistic function and the associated ambiguity or concealment of everyday reality is expressed in the photographs — for instance, by idyllising and idealising the service and its protagonists, by situating them in a supposedly untouched world that nourishes an unbroken tradition and thus maintains the illusion of being able to establish ‘pre-industrial social relations within an industrial system’.60 The reality was different. During the course of the war — in the summer of 1941, compulsory military service under the newly created Kriegshilfsdienst or KHD (War Auxiliary Service) was extended from six to twelve months — the young women were no longer used only in agriculture, but increasingly in administration, in war production, and finally also in the Wehrmacht itself, for example in air defence.61 The allocation of work within the RADwJ and KHD also did not run as smoothly as the illustrated books portrayed. Due to a high level of labour turnover, there were considerable problems in the recruitment of female management personnel. The women in the camps were also often disturbed by a lack of privacy. More problematically, the farmers found the young helpers’ activities to be ineffective and too expensive, as their regular working hours of six hours a day, six days a week, especially during harvest time, did not correspond to the actual need of at least eleven hours a day.62

With the Arbeitsmaiden am Werk project, Hans Retzlaff had left his traditional ‘folkloristic’ terrain for the first time in favour of a topical theme grounded in contemporary reality. His pictorial language, however, continued to be oriented towards a backward-looking view of ‘folkish’ Heimat photograph. As a result, the propagandised features, ‘led even deeper into timelessness, into the impasse of mythologization’, which, in a time of upheaval, helped to assert ‘a detached, transcendent being’.63 The recurring public image for the home front was that of an illusory world with stereotypically recurring, strongly symbolically charged images of the individual female leader and her young workers, who mastered every job with flying colours and who were also the potential bride for the young farmer on the alpine pasture or a caring surrogate mother in the extended family of farmers. Retzlaff’s official illustrated book was thus directed against the literary culture of the Weimar Republic by supporting the propaganda strategists’ demand for images to take precedence over words. Photography was assigned the function of a supposedly truthful communicator and cultural carrier of ideology, and it was given a firm place in racial-ideological propaganda.

The Heimat in Colour

The fact that the technique of colour photography is largely obscured as part of its propaganda function becomes understandable when the political application of the new medium is taken into account. In 1939, the National Socialists celebrated the centenary of photography. Initially, the new technology was seen as a patriotic way of highlighting the achievements of German industry internationally. ‘Agfacolor’ was to be marketed as a leading export within the aspirational economic framework of autarky, which focused to a considerable extent on the chemical industry. The propaganda role is, however, equally relevant. Colour photography, for example, was ‘involved in fundamental considerations of mass psychological influence, especially with regard to the creation of positive images of memories’.64 These ‘positive memories’ could not be created with ordinary photographs of everyday life and work, but rather with ‘beautiful photographs’65 from a propositional notion of a healthy and wholesome homeland. Accordingly, the picture themes were strongly oriented towards a pastoral past. The integration of colour photography into National Socialist propaganda became more and more important during the war. Photographers such as Hans Retzlaff marketed postcard series of rural scenes under the label ‘Banater Schwaben’ and ‘Reichsarbeitsdienst’. These colour pictures were popular with soldiers, and relatives and friends would readily send postcards into the field or to military bases, wherever the soldier was stationed. For example, in August 1941, a group of Hitler Youth girls (Jungmädel) sent the postcard ‘Bei der Heuernte in Norddeutschland’ to their schoolmate Heini Kühl, a lance corporal who was serving in Paris: ‘We send our best wishes to you at the muster. In autumn ‘41 you go. Unfortunately, all too soon’66 (see Fig. 4.11).

Fig. 4.11 Hans Retzlaff, Bei der Heuernte in Norddeutschland (Haymaking in Northern Germany), picture postcard, 1941, Archiv Ulrich Hägele). Public domain.

The colour picture shows a blonde young woman raking hay in a meadow. She wears a white apron, a blue blouse, and a red headscarf — the work uniform of the Reichsarbeitsdienst. However, the role of colour photography as a medium of direct propaganda during the National Socialist era must not be underestimated. With this long-term effect, the all-pervasive propaganda of the National Socialist regime, in the sense of presenting a positive world view and in light of the subsequent horrors of war, appear as a kind of visual virus that can, in retrospect, distort a rational reading of the past even for future generations.

Amateur photographers and photographic literature played a fundamental role in the success of colour photography. From 1938, the Photoblätter (Photo News), Agfa’s in-house magazine, massively promoted the new films and gave amateurs practical advice on using the materials. Paul Wolff, one of the more prominent of the National Socialist propaganda photographers, played a decisive role in making colour photography popular with amateurs during the war. Even the title of his 1942 illustrated book Meine Erfahrungen … farbig (My Experiences … in Colour) closely followed a corresponding 1930s publication67 by the author on 35mm photography with the Leica camera and reads in large part like an advertising brochure for I. G. Farben, under whose supervision the development of the colour-reversal process had been driven forward. Wolff had invited Heiner Kurzbein, head of the picture-press department at the Reich Ministry for Propaganda and Popular Enlightenment to write the forward to the first edition.68 The fifty-four photographs were made by Paul Wolff, Alfred Tritschler, and Rudolf Hermann, although the photographers are not mentioned in the captions. Instead, Wolff provides detailed explanations of some of the pictures. The emotional Heimat paradigm of a Germanic-dominated history, still apparent in the 1939 colour photography book Die deutsche Donau (The German Danube),69 had by this point almost completely disappeared. Image composition and visual staging are here orientated towards a more objective, commercial style of photography. Technical equipment, the workplace (whether it is a hospital ward or in front of a blazing blast furnace) and holidays on the beach have now become the focus. The women photographed radiate the self-confident elegance of well-paid, professional models and the photographs seem more akin to those of a fashion magazine. The National Socialist visual stratagem has, it seems, been shaken: a young woman with loose blonde hair lights a cigarette from a candle in a lascivious manner; another, seated behind the steering wheel of her car, flirts through the open sunroof with the filling-station attendant. Atmospheric landscape pictures of the Alps, flower studies, architectural and art photographs are also present. However, this time they do not come from the Reich itself. The architectural images are all exclusively Italian — Assisi, Siena, Perugia, and Florence. In addition, the few remaining representations of traditional costume do not originate from Germany. Wolff presents a ‘Little Girl from the Sarentino Valley’ (see Fig. 4.12).

Fig. 4.12 Paul Wolff, Kleines Mädchen aus dem Sarntal (A Little Girl from the Sarentino Valley), 1942, reproduced in Meine Erfahrungen… farbig (My Experiences… in Colour) (Frankfurt am Main: Breidenstein, 1942), Plate 18. Public domain.

The photographic image of the pastoral, which had played a central role in the illustrated books since the 1920s, was visually moving south and eastwards, beyond the cultural sphere of Central Europe. The women portrayed wear headscarves and seem to have gathered in the field to pray. If one reads the possible symbolic components in the publication — the picture is placed on the right side, the contextual information printed on the left — the gaze of the women is to the right, out of the picture frame, a suggestion that, geographically at least, the image might be read as a turning-away from the Reich towards the East. Nevertheless, the question arises why Wolff broke with the usual pictorial conventions of analogous publications. Was this done to visually de-ideologize the publication in anticipation of a possible defeat? Was the author considering future marketing for a new edition of the book after the war, or were there simply no equivalent images from Germany? Why does the staged, ethnically orientated colour Heimat photography of the rural milieu suddenly no longer play a role? The second and third editions of this volume Meine Erfahrungen … farbig were published — without the foreword by Kurzbein, but still with the illustrations of the first edition — in 1948 by the Frankfurter Umschau Verlag.70 In terms of its photographs, at least, the work was able to survive the end of the National Socialist era without major changes. This suggests that Paul Wolff and his co-author Alfred Tritschler had a certain foresight about the sales of the book beyond the end of the war. In this sense, the visual removal of ideology in the publication can be explained. Certainly, it was not due to any lack of corresponding colour photographs from the Reich. For example, Eduard von Pagenhardt’s 1938 publication — an anthology of colour illustrations by various photographers — had already touched on ‘modern life’, idyllic landscapes and the folkloristic genre of Heimat photography.71 Besides night shots of the world exhibition in Paris and atmospheric illuminated swastika flags, naked, ball-playing women were also presented, as well as pictures of the tranquil and technology-free life in the countryside. The latter was represented by the work of Erich Retzlaff with his Agfacolor portraits, but also by photojournalist Emil Grimm — in the image entitled ‘Schwere Arbeit,’ two workers standing in the water on the banks of a river try to move a boulder with the help of a horse and cart. By contrast, Meine Erfahrungen … farbig presents a cross section of innocuous topics; pictures with National Socialist symbols are looked for in vain.

Conclusion

At the beginning of the 1930s, the notion of Heimat was already no longer solely related to the region one came from. As with the first wave of enthusiasm for the notion of Heimat at the turn of the century, a photographic visualisation played a decisive role in this transformation. For example, Lendvai-Dircksen had reinterpreted the Heimat and the folkloristic component of traditional costume as a specific characteristic of an ethnic-Germanic way of life. Her photographs thus mutated into an instrument to exclude those parts of the German population that fell through the grid of racial ideology: Jews, Sinti, and Roma, the mentally ill, the physically and mentally disabled as well as critics of the regime; all were robbed of their place in the Heimat. Persecution, expulsion, emigration, and murder were to follow. What mattered now was no longer so much a demonstration of the achievements of technology, but rather a representation of a pristine rural utopia as evidenced by the eternal splendour of traditional costumes. This media-propagandistic construction of the visual gaze contradicted the reality of a hegemonic National Socialism striving towards a society that embraced state-of-the-art technologies. This technological reality does not appear in these picture series. The other pictorial aspects: gender roles, the visualisation of different generations, or the racial presentation of blonde girls, mostly dressed in traditional costume, is certainly evident. Hans Retzlaff’s visual approach — the frontality of the subjects, the concentration on historical vestments, the de-individualization in favour of types — fosters this stylistic reduction in the documentation of traditional costume. His photographs ignore current social and societal circumstances and instead suggest the timelessness of an ancient, homogeneous rural culture. Another decisive factor for the propagandistic potential of this völkisch photography is the fact that it was commissioned as part of an educational and didactic tool by scientific disciplines such as Ethnology that employed a scientific method. No objective verification of sources took place. In this respect, Hans Retzlaff’s works could also visualise ideology — in the form of a kind of visual rhetorical objectivation, in which a traditional utensil, a custom, or a farmer’s cottage could indicate its ‘Germanic’ roots.

Hans Retzlaff’s illustrated books, like the corresponding examples by Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, remained focussed on the idealisation of the rural world during the 1930s. Any reference to the present was, at best, demonstrated by the continuity of tradition through National Socialism. The viewer is spared an encounter with technical achievements as well as armaments, industrialisation, mobility, social problems, and life in the big city. Nor did they address those groups of the population that increasingly suffered from racial ideology. Certainly, the title of Retzlaff’s book, Arbeitsmaiden am Werk, had explicitly confirmed that the author had primarily directed his camera at young women. However, implicitly this expressed a propagandistic element, vis-à-vis the people on the home front who would have to come to terms with the absence of men during the war. By 1940, National Socialist society already largely consisted of women, children, and older men working primarily in agriculture — just as Retzlaff had recorded it. Last but not least, the visual constructions crafted in these illustrated books still defined the collective memory of National Socialism long after 1945. Up until the present day, these euphemistic images served to compensate for an individual’s involvement with the regime. Indeed, using these often-innocuous images as evidence, these individual encounters and experiences during the period of National Socialism have been presented in a somewhat different light.

The ideologization of colour photography was somewhat different. Initial responses were determined by the primarily technically motivated tendencies of segmented modernism: as long as it did not disturb the ideology of ‘Blood and Soil’, then National Socialism recognised the successes of technology as part of an overall Germanic cultural achievement. Agfacolor’s colour process was regarded as one of those achievements, not least because it was a reasonable competitor to the American Kodachrome process; the prospect of the economic benefits to the state of bringing in foreign capital cannot be ignored either. In the mid-1930s, however, colour photography with the new 35mm technique was still in an experimental stage. Heimat photography was part of it, but not the only element. The focus was also on technology, transport, fashion, and leisure. The fact that Wolff and his partner had recognised the sign of the times at an early stage can be seen from the fact that the illustrated books of colour photography could later be reprinted with almost no major changes. At the end of the war and in the years that followed, the notion of Heimat, and indeed Heimat photography, continued to play a role as part of a nostalgic and backwards-looking milieu, even if only from the point of view of those who were part of the millions of displaced Germans who had fled or been forcibly expelled from former German territories.

1 Hermann Bausinger, ‘Chamäleon Heimat — eine feste Beziehung in Wandel’, Schwäbische Heimat 4 (2009), p. 396.

2 Jakob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch, Vol. 10 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1975), pp. 864–66.

3 Hermann Bausinger and Konrad Köstlin, eds, Heimat und Identität. Probleme regionaler Kultur. Studien zur Volkskunde und Kulturgeschichte Schleswig-Holsteins (Neumünster: Waxmann, 1980), p. 25.

4 Georg Simmel, ‘Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben’, in Theodor Petermann, ed., Die Großstadt. Vorträge und Aufsätze zur Städteausstellung. Jahrbuch der Gehe-Stiftung zu Dresden (Dresden: Gehe Stiftung, 1903), p. 187.

5 Heimatschutzbewegung literally translates as the Heimat protection movement. This movement emerged in the late nineteenth century as a reaction to rapid demographic changes and increasing industrialisation. The Heimatschutzbewegung or Heimatbewegung rejected modernity and extolled instead a return to traditional values, an appreciation of the virtues of agrarian life, the romanticisation of nature, and regional and national Germanic identity, amongst other things.

6 Oscar Schwindrazheim, ‘Heimatliche Kunstentdeckungsreisen mit der Camera,’ Deutscher Kamera-Almanach 1 (1905), 150–51.

7 Paul Schultze-Naumburg, ‘Der Garten auf dem Lande’, in Heinrich Sohnrey, ed., Kunst auf dem Lande (Bielefeld/Leipzig/Berlin: Velhagen & Klasing, 1905), p. 183.

8 August Sander, Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts with a text by Ulrich Keller (München: Schirmer & Mosel, 1980), p. 33. Sander’s project remained unfinished. The printing plates and the remaining copies of his 1929 book, Antlitz der Zeit (‘Face of Our Time’) were seized and destroyed by the National Socialists in 1936.

9 Sylvain Maresca, La photographie. Un miroir des sciences sociales (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996), p. 19.

10 Martina Mettner, Die Autonomie der Fotografie. Fotografie als Mittel des Ausdrucks und der Realitätserfassung am Beispiel ausgewählter Fotografenkarrieren (Marburg: Jonas, 1987), pp. 72–75.

11 Sander, Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (1980), p. 11.

12 Ibid., p. 21.

13 Joseph Goebbels in his opening speech to the exhibition ‘Die Kamera’ in Berlin 1933, reproduced in Druck und Reproduktion, Betriebsausstellung auf der ‘Kamera’, 1 (1933), pp. 3–6.

14 Quoted here from the 1934 edition: Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (Berlin: Drei Masken Verlag, 1934), p. 5.

15 Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, ‘Zur Psychologie des Sehens’ (1931) reproduced in Wolfgang Kemp, ed., Theorie der Fotografie, Vol. 2 (München: Schirmer-Mosel, 1979), p. 160.

16 Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (1934), p. 6.

17 Lendvai-Dircksen, ‘Zur Psychologie des Sehens’ (1931), p. 158.

18 See for example Willi Warstat, review of the exhibition of the GDL (Gesellschaft Deutscher Lichtbildner) International Press Exhibition (Pressa) in Cologne in 1928 in Das Atelier des Photographen 35 (1928), 126–28 and also Claudia Gabriele Philipp, ‘Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (1883–1962). Verschiedene Möglichkeiten, eine Fotografin zu rezipieren’, Fotogeschichte 9 (1983), 56.

19 Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, ‘Ohne Titel’, in Wilhelm Schöppe, ed., Meister der Kamera erzählen. Wie sie wurden und wie sie arbeiten (Halle an der Saale: Wilhelm Knapp, 1935), p. 35.

20 Lendvai-Dircksen, ‘Zur Psychologie des Sehens’ (1931), p. 162.

21 For more detail on this subject see, Falk Blask and Thomas Friedrich, eds, Menschenbild und Volksgesicht. Positionen zur Porträtfotografie im Nationalsozialismus (Münster: LIT Verlag, 2005).

22 Lendvai-Dircksen, ‘Ohne Titel’ (1935), p. 37.

23 Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (1934), p. 106.

24 Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (1934), p. 224.

25 Ibid., p. 226.

26 Ibid., p. 7.

27 Rolf Sachsse, Die Erziehung zum Wegsehen. Fotografie im NS-Staat (Berlin: Philo Fine Arts, 2003), p. 156.

28 Lendvai-Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (1934), p. 138.

29 Ibid., p. 13.

30 Philipp, ‘Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (1883–1962). Verschiedene Möglichkeiten, eine Fotografin zu rezipieren’ (1983), 48.

31 Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Nordsee-Menschen. Deutsche Meisteraufnahmen (München: F. Bruckmann, 1937).

32 See Sachsse, Die Erziehung zum Wegsehen (2003), p. 57. Also, Jeanine Fiedler, ed., Fotografie am Bauhaus (Berlin: Dirk Nishen, 1990).

33 See Philipp, ‘Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (1883–1962). Verschiedene Möglichkeiten, eine Fotografin zu rezipieren’ (1983), 40.

34 Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung 39:11 (1930), 467–68.

35 Erna Lendvai Dircksen, Das deutsche Volksgesicht. Flandern (Bayreuth: Gauverlag, 1942). Riedweg was a highly influential figure in the SS and close associate of Reichsführer SS, Heinrich Himmler (1900–1945).

36 Lendvai-Dircksen, ‘Ohne Titel’ (1935), 38.

37 Lendvai-Dircksen , Das deutsche Volksgesicht (1934), p. 8.

38 See Friedrich Merkenschlager, Rassensonderung, Rassenmischung, Rassenwandlung (Berlin: Waldemar Hoffmann, 1933); also, Arthur Gewehr, ‘Bildniskunst und Rassenkunde’, Gebrauchs-Photographie und das Atelier des Photographen 41:12 (1934), 88; also see for example Volk und Rasse 4 (April 1942); and Volk und Rasse 6 (June 1942).

39 See Hans F. K. Günther, Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes. Mit 29 Karten und 564 Abbildungen (München: Lehmann, 1930), figure 113, ‘Spicka-Neufeld bei Cuxhaven, Friesland, Nordisch.’ The photograph also appeared uncropped in Das deutsche Volksgesicht, on page 57 as ‘Friesischer Fischer aus dem Marschland Wursten’.

40 See Deutschland. Olympia-Jahr 1936 (Berlin: Volk und Reich, 1936).

41 Völkisch or Heimat photography as used in the terminology of the National Socialist state, see Paul Lüking, ‘Richtlinien des VDAV für fotografische Arbeiten,’ Fotofreund 13 (1933), 207.

42 See Götz Aly, Hitlers Volksstaat. Raub, Rassenkrieg und nationaler Sozialismus (Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 2005), and also J. Adam Tooze, Ökonomie der Zerstörung. Die Geschichte der Wirtschaft im Nationalsozialismus (München: Siedler, 2007). [Editor’s note — The notion that the autobahns were designed to facilitate military ends has long been debunked, see for example Thomas Zeller’s Driving Germany: The Landscape of the German Autobahn, 1930–1970 (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010).]

43 See Gudrun König and Ulrich Hägele, eds, Völkische Posen, volkskundliche Dokumente. Hans Retzlaffs Fotografien 1930 bis 1945 (Marburg: Jonas, 1999).

44 Ferdinand Herrmann and Wolfgang Treutlein, eds, Brauch und Sinnbild. Eugen Fehrle zum 60. Geburtstag (Karlsruhe: Südwestdeutsche Druck und Verlagsgesellschaft, 1940), p. 229.

45 Margit Haatz, Agnes Matthias and Ute Schulz, ‘Retzlaff-Portraits im ikonographischen Vergleich,’ in Völkische Posen, volkskundliche Dokumente (1999), p. 53.

46 A photographic study of women serving in the Reichsarbeitsdienst or RAD.

47 Will Decker, in the ‘Introduction’ of Hans Retzlaff, Arbeitsmaiden am Werk (Leipzig: E.A. Seemann, 1940), p. 10.

48 ‘Working maid’ or Arbeitsmaid was the women’s labour service (RADwj) equivalent to the rank of private.

49 The Arbeitsdienst camps were part of the Reich Labour Service for young men and women; originally intended as a means of alleviating unemployment, it became in effect a form of national service. See for example Thompson, Paul W. “Reichsarbeitsdienst.” The Military Engineer, 28.160 (1936) 291–92.

50 See for example, Ulrich Herrmann, ‘Formationserziehung — Zur Theorie und Praxis edukativ-formativer Manipulation von jungen Menschen’ in Ulrich Hermann and Ulrich Nassen, eds, Formative Ästhetik im Nationalsozialismus. Intentionen. Medien und Praxisformen totalitärer ästhetischer Herrschaft und Beherrschung (Weinheim/Basel: Beltz, 1993), pp. 101–12. Also see Jill Stephenson, ‘Der Arbeitsdienst für die weibliche Jugend,’ in Dagmar Reese, ed., Die BDM-Generation. Weibliche Jugendliche in Deutschland und Österreich im Nationalsozialismus (Berlin: Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, 2007), pp. 255–88.

51 See Marianne Wex, ‘Weibliche’ und ‘männliche’ Körpersprache als Folge patriarchalischer Machtverhältnisse (Frankfurt: Verlag Marianne Wex, 1980). Also, Helmut Maier, ‘Der heitere Ernst körperlicher Herrschaftsstrategien. Über “weibliche” und “männliche” Posen auf privaten Urlaubsfotografien,’ Fotogeschichte 41 (1991), 47–59.

52 See Uli Linke, German Bodies. Race and Representation after Hitler (New York/London: Routledge, 1999).

53 See Heimat, 5 (November/December 2010). The headline reads: ‘Vertrautheit, Geborgenheit und der Duft von frischem Hefekuchen bei meiner Oma an einem Samstagmorgen,’ (Familiarity, security and the smell of fresh yeast cake at my grandma’s on a Saturday morning).

54 See Gustav von Estorff, Daß die Arbeit Freude werde! Ein Bildbericht von den Arbeitsmaiden. Mit einem Geleitwort von Reichsarbeitsführer Konstantin Hierl und einem Vorwort von Generalarbeitsführer Dr. Norbert Schmeidler (Berlin: Zeitgeschichte-Verlag Wilhelm Andermann, 1938). Another illustrated book on the subject is Hildruth Schmidt-Vanderheyden, ed., Arbeitsmaiden in Ostpommern. Ein Bildbuch für Führerinnen und Arbeitsmaiden, von der Bezirksleitung XIV, Pommern-Ost (Berlin: Klinghammer, 1943).

55 Purper worked repeatedly and, apparently with great success, on the theme of these ‘Arbeitsmaiden’. A photo book, first published in 1939, had by 1942 reached a circulation of 24,000 copies. See Gertrud Schwerdtfeger-Zypries, Liselotte Purper: Das ist der weibliche Arbeitsdienst! (Berlin: Junge Generation, 1940). The photography discussed here is not included in the book.

56 Reichsführer SS, SS Hauptamt, Der Untermensch (Berlin: Nordland, 1942).

57 Detlef Hoffmann, ‘“Auch in der Nazizeit war zwölfmal Spargelzeit”. Die Vielfalt der Bilder und der Primat der Rassenpolitik,’ Fotogeschichte 63 (1997), 61.

58 Rolf Sachsse, ‘Probleme der Annäherung. Thesen zu einem diffusen Thema: NS-Fotografie,’ Fotogeschichte 5 (1982), 59–65 and Sachsse, Die Erziehung zum Wegsehen (2003), p. 15.

59 Decker, Arbeitsmaiden am Werk (1940), p. 10.

60 Stefan Bajor, ‘Weiblicher Arbeitsdienst im “Dritten Reich”. Ein Konflikt zwischen Ideologie und Ökonomie,’ Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 28:4 (1980), 341.

61 Stephenson, ‘Der Arbeitsdienst für die weibliche Jugend’ (2007), 265

62 Ibid., 271–76.

63 Gunther Waibl, ‘Photographie in Südtirol während des Faschismus,’ in Reinhard Johler, Ludwig Paulmichl and Barbara Plankensteiner, eds, Südtirol. Im Auge der Ethnographen (Vienna: Edition per procura, 1991), p. 146.

64 Sachsse, Die Erziehung zum Wegsehen. Fotografie im NS-Staat (2003), p. 148.

65 Martin Hürlimann, Frankreich. Baukunst, Landschaft und Volksleben (Berlin/Zürich: Atlantis, 1927), XXVIII.

66 Colour photographic postcard by Hans Retzlaff, ‘Reichsarbeitsdienst für die weibliche Jugend. Bei der Heuernte in Norddeutschland,’ Series II, No. 2.

67 See Paul Wolff, Meine Erfahrungen mit der Leica (Frankfurt am Main: H. Bechhold, 1934). The book with 192 gravure illustrations had sold over 50,000 copies by 1939.

68 Paul Wolff, Meine Erfahrungen … farbig (Frankfurt am Main: Breidenstein, 1942).

69 See Kurt Peter Karfeld and Artur Kuhnert, Die deutsche Donau. Ein Farbbild-Buch (Leipzig: Paul List, 1939).

70 The total circulation was 35,000 copies.

71 Eduard von Pagenhardt, ed., Agfacolor, das farbige Lichtbild. Grundlagen und Aufnahmetechnik für den Liebhaberfotografen (München: Knorr & Hirth, 1938).