Conclusion

© Christopher Webster, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202.07

In a collapsed and burned-out building, two boys sift through a mountain of rubble, charred beams, and twisted metal; their quest is to find whole bricks.

Fig 7.1 Hans Saebens, ‘Untitled’, silver gelatin print, 1945. Courtesy of Aberystwyth University’s School of Art Museum and Galleries.

The all-pervasive and almost overpowering smell of corruption drifts through the air but the once black skies are now clear of both bombers and smoke. Today, the sun is shining and even here, on the edge of ruin, these children find a purpose; mature beyond their years, they are focused on their task. The Stunde Null, the zero hour, has passed, and with the men either dead, far away, or imprisoned, the children too must work alongside the thousands of Trümmerfrauen, or rubble women, to clear the way for a future that few foresaw, and none can now predict. This is what remains after nearly six years of war — ashes and ruins, the final symbol of the cataclysm that has been visited on Europe and indeed the world. Somewhere too, amongst the apocalyptic miles of crushed and crumbling wreckage that was once the city of Berlin, lie the ashes of the photographic archives of many of the photographers discussed in this text. Literally and symbolically, the fires of defeat have consumed the ideological work that had become their métier for the previous two decades.

But this was not the end of the careers of these photographers who had been ‘for the Reich’. Indeed, an examination of many of their post-war activities reveals that, although often not without some personal difficulty, they nevertheless adapted quickly and successfully to the dramatic change in circumstances. In addition to the destruction wrought by allied bombing, many of them embarked on

…selective cleansing actions of private as well as commercial archives, when potentially compromising material was destroyed. As a result of this self-inflicted ‘denazification,’ the preponderance of photos from this period consists of images that are ideologically ‘clean’.1

Even those who no longer remained committed to working with ‘folksy’ images of the German Heimat and its people saw their surviving pre-1945 work continue to be used in publications that were now attuned to a tourist market, and one that chimed with earlier, less ideological, conceptions of a gemütlich (cosy) and nostalgic image of German life.2 Images of women in traditional costume were reconceptualised as ‘quaint’ and representative of ‘warm traditions’. For example, Hans Retzlaff’s photograph of the Bückeburg Bäuerin is reproduced in the 1961 book Niedersachsen3 and presented for the new tourist market with its title in German, English and French4 (see Fig. 7.2).

Fig 7.2 Hans Retzlaff, Bückeburg. Bäuerin in festlicher Tracht mit goldbesticktem Kopfputz (Peasant woman wearing traditional costume), c.1935, reproduced in Niedersachsen: Bilder eines deutschen Landes, introduction by Heinrich Mersmann (Frankfurt: Verlag Weidlich, 1961), (unpaginated). Public domain.

Similarly, Hans Retzlaff’s namesake, Erich Retzlaff, resumed his successful photographic career following the war’s end and, besides developing a lucrative career as a commercial photographer, continued his photographic portrait project to capture the ‘great spirit’ of the German mind, which became his book Das Geistige Gesicht Deutschlands (The Spiritual Face of Germany) published in 1952. This book was indeed a direct extension of his 1944 colour project Das Gesicht des Geistes (The Face of the Spirit). However, as in the recontextualization of Hans Retzlaff’s photographs of the Heimat and its people, Erich Retzlaff’s focus was also now realigned. Instead of an emphasis on a racial-physiognomic elite, the portraits he presented were framed as part of a cold war strategy to present the democratic intellectual cultural force that was the new capitalist West Germany (in ideological opposition to the Marxist totalitarianism of East Germany and the Soviet Bloc).

If any of these former practitioners were still convinced by National Socialism or harboured positive memories of their careers before the end of the war, then they tempered their feelings for the new dispensation, for this was their ‘new’ Selbstgleichschaltung or ‘self-co-ordination’. Unsurprisingly though, there is certainly something strikingly different about the photographic output and re-presentation of these photographers works in the post-war period. The downfall of the Third Reich produced, in the main, a palpable difference in the creative output of these prodigious photographers. The visual mutation of their post-war work, and the changes in the biographical narratives that they formed around themselves, are certainly attributable to the general calumny and forced psychological shift that many Germans were experiencing in that most uncertain of periods following the disaster of the war and the collapse of National Socialism. In a general sense, their photography was less dynamic than the work they made in the 1930s and 1940s. The subject matter, without the structure of a National Socialist Weltanschauung, now tended to be rather clichéd and rudderless, lacking the punch and bite of its earlier manifestations, or else it was driven by commercial imperatives. This shift tells its own story of trauma and a conscious effort to leave behind the new stigma of the past in the period of Entnazifizierung or ‘denazification’.

Each of the chapters in this book has explored the relationship between specific trends that were influential in Germany during the period of the Third Reich (such as physiognomy) and the relationship to an aesthetic and Nationalist photography. As Andrés Zervigón pointed out in chapter three, there was a conscious combining of past traditions with modern visions, a neo-traditionalism manifest in the photographic form that was ‘aesthetically pioneering’. Each chapter finds that a highly creative and inventive manifestation of modernist photographic practices persisted (through a nationalist lens at least) after 1933. Therefore, the notion that an innovative and modernist-influenced photography ceased to exist in Germany after 1933 can thus be readily dismissed. As one American reviewer wrote in 1937, ‘German art photography is the last word in both technical expertness and human sympathy’.5

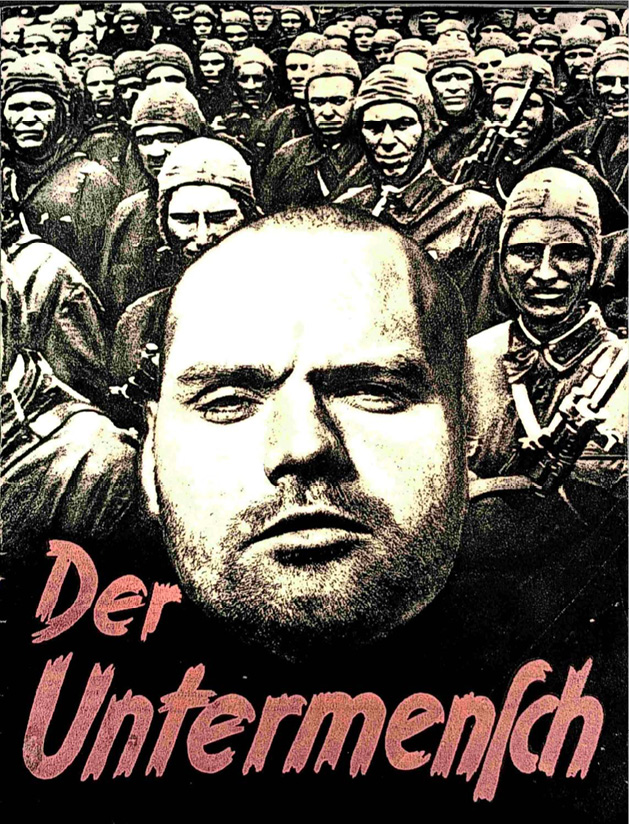

Of course, the application of these photographic portfolios for political ends is beyond dispute. Sometimes the association was overtly political, as in the use of these photographic works in ideologically radical publications such as the notorious 1942 publication Der Untermensch6 (the subhuman).

Fig. 7.3 Cover image of the SS pamphlet ‘Der Untermensch’ (The Subhuman), Reichsführer SS, SS Hauptamt, Der Untermensch (Berlin: Nordland, 1942).Public domain.

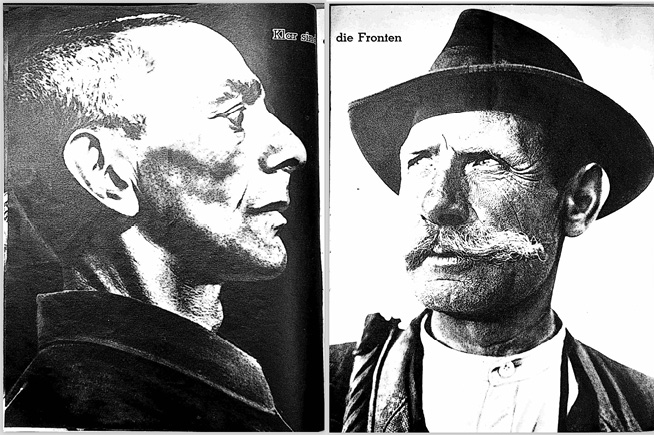

Produced by the SS as a ‘training brochure’, it used portrait and landscape images by Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, Hans Retzlaff, F. F. Bauer, and Ilse Steinhoff amongst others. These were all photographers who had engaged with an aesthetic vision of the German Volk, all who had artistically explored physiognomy in their working practices. The Untermensch document used photo-doubling techniques and polemical language to draw comparisons between ‘good’ German stock and a parodic and negative representation of (particularly) Slavic and Jewish types.

Fig. 7.4 Double-page comparison of two racial types entitled ‘Klar sind die Fronten’ (the battlelines are clear) from the SS pamphlet ‘Der Untermensch’ (The Subhuman), Reichsführer SS, SS Hauptamt, Der Untermensch (Berlin: Nordland, 1942). Public domain.

The unpaginated illustrated text opens with a statement by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler from 1935, where he is quoted as saying:

As long as there are people on earth, the battle between humans and subhumans will be the historical rule, this struggle against our folk, led by the Jew, belongs, as far as we can look back into the past, to the natural course of life on our planet. One can calmly come to the conclusion that this struggle to the death is certainly as much a law of nature as the attack of the plague bacillus on a healthy human body.7

As Jennifer Evans has recently pointed out, ‘Along its various pathways of production, consumption and display, a photograph trains the eye to identify what it sees while provoking the mind to judge’.8 The creative and staged photography of Ethnos made and used within the sphere of National Socialism (along with its many other manifestations) was streamlined to intervene between the viewers’ encounter with daily life and the larger world surrounding them. It was intended to guide the viewer to assess, to formulate opinions, to identify with, and to educate. It was also intended, as Rolf Sachsse has elucidated in chapter one, to provide a positive feeling and ‘warm’ memory whilst the viewer is ‘looking away’ into the constructed space of the photograph.

An example of this type of pedagogical approach for the broader public was the Volk und Rasse touring exhibition (1934–1937)9 organized by the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum and the Rassenpolitische Amt der NSDAP (Office of Racial Policy). This exhibition featured a large number of these artistically stylised portraits of the German ‘type’10 (see Fig. 7.5).

Fig. 7.5 Volk und Rasse, a touring exhibition (1934–1937) arranged by the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum and the Rassenpolitische Amt der NSDAP (Office of Racial Policy). Image courtesy of the Stiftung Deutsches Hygiene-Museum.

The accompanying brochure advised: ‘Every German man and every German woman must go into this exhibition and allow this display to have its effect on them. An hour of such an instructional lesson is more effective than the spoken or read word’.

Reinforcing the notion of tradition and modernity, in 1937 the Reichsgesetzblatt wrote enthusiastically about the exhibition:

Thus, this exhibition reveals the great inner connections between blood and soil and race and ethnicity. It teaches that every one of us is a member of a great chain of ancestors, and that our fate is defined by those who preceded us just as our people’s future will be a reflection of us. There is probably no more vivid a reminder of the great responsibility that each one of us bears for his people than this exhibition ‘People and Race’.11

Yet, it might also be argued that the more extreme and politicised applications (and the example of Der Untermensch cited above is a crude enough specimen) were a by-product rather than an intended outcome of the genre of work that these photographers had developed. Its political use might have been an obvious outcome and one of which they would or should have been aware. However, the photographers’ idealised, romantic-nationalist approach to framing their subjects should, it could be argued, be considered outside of the (often) crude ends to which the political ideologues used their work. Theirs was a kind of ‘rightist New Objectivity’, or at least one that mirrored the conservative and traditionalist values of the photographers whilst employing modern photographic techniques. Does this exonerate them from any guilt by association with politics? A Soviet contemporary of these German photographers provides a useful comparison.

Boris Ignatovich enjoyed the patronage of the Soviet state as a photographer whose work was regarded as quintessentially Socialist Realist and was widely used in Soviet propaganda, but he was also regarded as part of that avant-garde in photography that emerged during the interwar years. Ignatovich was selected for that seminal exhibition, Film und Foto, which opened in Stuttgart in 1929. So, whilst being regarded as an avant-garde creator, Ignatovich was also used as a ‘political’ photographer of the Soviet system, a system whose own use of visual media was equal to that of National Socialism in its ruthless ambition to eradicate the state’s perceived enemies (amongst other applications). The Soviet propaganda machine utilised the work of artists, writers and photographers (like Ignatovich) in much the same way as National Socialism did in Germany. The ends were often equally destructive, if not, it could legitimately be argued, much more so given the brutal extended legacy of Communism.

As the writer Maksim Gorky opined when discussing the aims of propaganda:

Class hatred should be cultivated by an organic revulsion as far as the enemy is concerned. Enemies must be seen as inferior. I believe quite profoundly that the enemy is our inferior and is a degenerate not only in the physical plane but also in the moral sense.12

Gorky’s words might have been lifted from Der Untermensch itself.

Although some might regard the comparison as problematic,13 it is relevant when comparing the post-regime treatment of the two groups of practitioners. Photographers of the Soviet Union are now regarded as laudable additions to the canon of the history of photography. They are widely exhibited and discussed positively without the political caveats that inevitably accompany any discussion of their National Socialist German contemporaries. For example, in 2004 the Nailya Alexander Gallery in New York staged an exhibition entitled Staging Happiness: The Formation of Socialist Realist Photography. The gallery wrote:

Photography became the most important artistic tool in shaping the collective consciousness with the purpose to create a New Soviet Man. This resulted in a multitude of commissioned works featuring beautified images of heroic men and women, cheerful pioneers, abundant produce as well as glorified depictions of the Soviet military might and achievements of new economic policies that led to [a] prosperous future under the leadership of the Great Stalin. Photographers became the creators of new icons, and the subjects of their photographs were hailed as the stars of Soviet publications — state-sanctioned role models for the general population.14

Photography certainly became an integral tool in delineating the notion of a unified German identity during the National Socialist era. Like their Soviet contemporaries, many of these photographers had no opportunity to leave Germany even if they desired to do so, and of course, many interpreted the new dispensation as a positive transformation, whether in terms of increased patronage (because of their existing reputations) or in terms of new opportunities (as other practitioners fell afoul of National Socialism). What was certain was that, in order to continue practising their craft, photographers needed to be aware of, and in line with, the expectations of the new National Socialist state. This was applicable to cinematographers, sculptors, painters, or indeed anybody working in the arts at the time. Should anyone be in any doubt about these requirements, Joseph Goebbels, the minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, stated in 1938:

Art […] must feel itself closely connected with the elemental laws of national life. Art and civilisation are implanted in the mother soil of the nation. They are, consequently, forever dependent upon the moral, social, and national principles of the state.15

The requirement of photography was ‘to promote photography in a racial sense’.16 It was essential that photography must include ‘a vital link between the work and national customs and traditions’.17 Such directions disallowed photographers like August Sander entry, and it certainly excluded others of the wrong political or racial background.

Unlike August Sander’s socially structured physiognomic study of Germans, these photographers of a physiognomic Ethnos tended to plough a straight furrow, with the work fixed on those fundamentals that comprised the idealised elements of the National Socialist community and a National Socialist mythos.

As in Socialist Realism, these German counterparts are both real and ideal. They do indeed extol the virtues of simplicity, unity, identity, and purity that formed part of the propaganda notions of the ‘National Community’. There is no doubt that many of these photographers had a pronounced feeling of national sentiment. Theirs was a photography concerned with the ‘poetics of nationhood’.18 These images can be seen to fit into a crafted demonstration of what was posited as ‘national culture’.

Was it simply the presence of ideological concerns that might be said to define a National Socialist photographic aesthetic, Sontag’s so-called ‘Fascist aesthetic’? When examining a documentary photograph, the viewer is confronted with different questions than in an encounter with the art photograph. However, like the photography that was produced for Roosevelt’s Farm Security Administration in the United States, these images of Ethnos are cloaked in the language of the document yet resonate with the aesthetic language of the art photograph and, as a result, function as both fact and fiction; they point to a myth through the veil of the photographic ‘becoming in time’.19 Yet the suggestion of this myth is not intended to undermine the plausibility of the image; rather, it reinforces the ideological mythos embedded in the picture and thus, when the viewer engaged with those images, they might confirm the place of the viewer of the time in relation to this national myth. As stories of the ‘real’, that is, as representations of people encountered in the field, these photographs, to quote the important British documentary filmmaker John Grierson, apply ‘a creative treatment of actuality’ (my italics).20

Similarly, as David Bate pointed out in an insightful article:

[…] documentary images are those that create an allegorical sense, a picture with a non-literal significance, a meaning and point beyond literal content […] All good documentary photographs generate this implicit commentary, where the content and form are combined, harnessed together to make a ‘bigger picture’ and meaning.21

These German photographs are a visual manifestation of a grappling with modernity during a revolutionary and culturally challenging time. Working with this allegorical sense, using Ethnos as the thread that united them, they created an alternative but modern form for a representation of a traditional idea, namely the notion of ‘Blood and Soil’. However, as a traditional hypothesis, ‘Blood and Soil’ became unacceptable after 1945 because of the association of this idea with National Socialism.

In his equally polemical and brilliant 1990 critique of modern intellectual life in Germany, post-war German art, and the deleterious effect of the ‘anti-aesthetic’ on that art, the innovative German film-maker Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, discussed how the historic notion of ‘Blood and Soil’ had become tainted, a taboo. As Syberberg explains, ‘Blood and Soil’,

[…] means the aesthetics grown from an agrarian culture such as had determined European art through aristocratic principles of hierarchies of good and bad until the beginning of Modernism […] Hitler’s attempt to put his ideology into practice appears as a caricature of these traditions and was doomed to failure, as we know today. And yet it is a cultural historical epoch of European art from the Heimatfilm to the new classicism of a frightful ‘Strength-through-Joy’ gesture in sculpture, architecture and painting. It corresponds to a longing, however trivial, of men become a mass of people and to the intellectual isolation at the height of the industrial epoch and it is the other side of Modernism.22

Effectively, Syberberg argues for the recognition of its place not as a reactionary measure but as an essential, healthy, and necessary facet of modernity.

In the period before 1945, the German photographers whose work focussed on a framing of Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil), and on the Heimat, this photography of Ethnos, were part of a broader conservative milieu that used their photography to assert a counter-propositional position to aspects of modernity, and to reject political liberalism and the shifting social and cultural situation that struggled to emerge in the chaotic atmosphere of post-Versailles Germany. Like their contemporaries Ernst Jünger, Martin Heidegger, and Oswald Spengler, they were, very often, revolutionary conservatives and formed their photographic aesthetic as a counter-propositional bulwark to a zeitgeist that was perceived as alien and destructive to their own concept of German (and European) tradition. It can be no surprise then that the National Socialists seized upon it as a propaganda trope.

These photographs attempt to visually ‘cement’ the notion of the nation as one that is unified and typified by untainted landscapes, where relations with Nature are harmonious in an ecotopia interspersed with traditional hamlets, villages, and towns, and above all where the apogee of this national community is the representation of the German Bauer himself, situated eternally on the earth of his homeland. The individual is framed as an archetype of a rarefied and noble type. Young and old, the people are framed as linked by a common physicality and common activity. Their rootedness to the landscape, their Ethnos, is the substance upon which this ‘portrait’ is constructed. For even when this photography is not expressly a ‘portrait’, the works still portray unchanging core values: order, history, ancestral legacies (including race), and unity. These images are presented as the corrective to cosmopolitanism, deracination, and degeneracy — all factors cast as eternal threats to the German ‘racial soul’.

It is clear that photography, like other modern inventions and ideas, was readily utilised in the promulgation of National Socialist thinking. Certainly, in terms of the definition of the ideal racial type, it was seen as indispensable. Often these studies would not be produced under the direct auspices of the Reich Ministry for Propaganda, but rather they were made in an ostensibly independent mode and thus appeared to have a greater degree of creative freedom.23 Images such as those reproduced in journals such as Volk und Rasse, in which these photographers were regularly featured, focussed on using the photographic image as a tool to overtly highlight the ‘ideal’ racial type as part of the corporate national identity.24 However, unlike the scientific anthropological approach, with its frontal and lateral viewpoints forming an analytical archive, the photographers of the autochthonous Bauer presented their subjects in a single summary frame. They had, as Remco Ensel has pointed out, ‘emphasized the penetration of a nation’s inner life, which was equivalent to a people’s character, by means of a two-dimensional photo. Here, the photo acted as the medium that established the connection between body and mind. One photo was enough.’25

The photography explored in this book was constructed to render an image of the face, the body, and even geography and the landscape in a context of Ethnos, a physical and metaphysical ethno-physiognomy of Germany. In addition, this photography was made by highly skilled practitioners whose approach reflected international trends in avant-garde photography. They often adapted and applied the aesthetics of the ‘New Vision’ that resulted in a more direct, sharply focused and sometimes documentary approach to the medium. The work of these German photographers echoed the direct straight approach of many of the modernist photographers in America at that time. Indeed, some of the similarities are striking. With straight, sharp, close-cropped images, their German counterparts were also pioneers in using state-of-the-art early-twentieth-century photographic technologies like the 35mm Leica camera, and new film advances such as the Agfacolor Neu film introduced in 1936.

The fact that this photography was also created with, or applied to, an ideological current means that the work should be understood. Yet their closeness to National Socialism has ensured that in mainstream histories and museology these photographers have been critically marginalised, pushed into an art-historical closet. It appears that when discussing these works there has been (and often still is) an expectation that one must always proceed pejoratively. It has been, in the main, a continuation of that censorious art historical assumption that:

[…] all art under National Socialism was repellent and barbaric, even to the point of being too repellent and barbaric to analyse; and that aesthetic interest attaches only to that art which National Socialism set out to crush and destroy. 26

Such subjective ‘framing’ as originally partially challenged in Taylor and van der Will’s The Nazification of Art is inevitably counter-productive, and merely reveals the prejudices of the examiner rather than leading to any fresh understanding or positioning of the works in question. Such an attitude, as described in the quote above, is no longer valid nor relevant. Like music, literature, painting, and other artistic forms made in the Third Reich, creative photography that celebrated Ethnos cannot be regarded as an anomaly that is best forgotten, glossed over, or ignored. Nor can we simply regard these photographs as tainted objects to be reviled because of some of the applications during the period of the Third Reich. Beyond this usage, they stand as manifestations of a radical tradition that transcends the era in which they were made. Today, these images have become atavistic memory-shadows still haunting the fringes of our digital information highways (reappearing on the internet through social media and file-sharing sites, for example). This photographic work remains, a continuing manifestation of a political, ideological, esoteric, and Romantic mélange unique to its time. As such, these artefacts require a reading and a positioning in the aesthetic history of the modern era. That is the process that this book has set out to begin.

1 Ute Tellini, review of, Petra Rösgen, ed., frauenobjektiv: Fotograffinen 1940 bis 1950, in Woman’s Art Journal 23:2 (Autumn 2002–Winter 2003), 40.

2 For more on the peasant motif in German art and photography see Christian Weikop, ‘August Sander’s Der Bauer and the Pervasiveness of the Peasant Tradition’, Tate Papers 19 (Spring 2013), https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/19/august-sanders-der-bauer-and-the-pervasiveness-of-the-peasant-tradition

3 Niedersachsen: Bilder eines deutschen Landes, introduction by Heinrich Mersmann (Frankfurt:Verlag Weidlich, 1961), (unpaginated).

4 With his negatives destroyed, Hans Retzlaff travelled to the Institute of Folklore at Tübingen University after the war in order to make copy negatives of their extensive holdings of his prints.

5 R.T.H, ‘Menschen am Wasser,’ Review of Heinz Kuhbier, ed., Menschen am Wasser, in Books Abroad 11:1 (1937), 75. Hans Saebens’ images of Niederdeutschland were represented in this text.

6 Reichsführer SS, SS Hauptamt, Der Untermensch (Berlin: Nordland, 1942).

7 SS Hauptamt, Der Untermensch (1942).

8 Paul Betts, Jennifer Evans and Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, eds, The Ethics of Seeing: Photography and Twentieth Century German History (New York: Berghahn Books, 2018), p. 2.

9 The exhibition Volk und Rasse (1934–1937) came from the exhibition Deutsche Arbeit — Deutsches Volk (Berlin, 1934). In 1936, the exhibition was completely revised and, in 1937, it was integrated into the collection of the Deutsche Hygiene Museum (information courtesy Marion Schneider, DHM, e-mail correspondence 14 August 2017).

10 When I examined press images and related publications from this exhibition, I was able to identify (on behalf of the contemporary Deutsches Hygiene-Museum) some of the works as those by Hans Retzlaff, Erna Lendvai-Dircksen and Erich Retzlaff.

11 Reichsgesetzblatt, 2 (1937), 27.

12 Quoted in Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski and Stéphane Courtois, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 751.

13 Unlike National Socialism, Communism, its ideological nemesis, is still openly espoused in some quarters as politically viable or simply desirable. Despite the far longer and indisputably bloodier international legacy of applied Marxism, it is not uncommon in western countries to see the hammer and sickle flag waved enthusiastically at protest marches, for example.

14 See: http://www.nailyaalexandergallery.com/exhibitions/staging-happiness-the-formation-of-socialist-realist-photography

15 Joseph Goebbels quoted in Claudia Koonz, Mothers in the Fatherland: Women, the Family and Nazi Politics (London: Methuen, 1987), p. 56.

16 Klaus Honnef, Rolf Sachsse and Karin Thomas, eds, German Photography 1870–1970: Power of a Medium (Cologne: Dumont Bucherverlag, 1997), p. 8.

17 Honnef, et al, German Photography 1870–1970 (1997), p. 88.

18 Ian Jeffrey, German Photography of the 1930s (London: Royal Festival Hall, 1995), p. 10.

19 Jae Emerling, Photography History and Theory (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), p. 167.

20 In 1933 Grierson wrote, ‘Documentary, or the creative treatment of actuality, is a new art with no such background in the story and the stage as the studio product so glibly possesses.’ John Grierson, ‘The Documentary Producer,’ Cinema Quarterly 2:1 (1933), 8.

21 David Bate, ‘The Real Aesthetic: Documentary Noise,’ Portfolio: Contemporary Photography in Britain 5 (2010), 7.

22 Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, On the Fortunes and Misfortunes of Art in Post-War Germany (translated and annotated by Alexander Jacob), (London: Arktos, 2017), pp. 11–12 (originally Vom Unglück und Glück der Kunst in Deutschland nach dem letzten Kriege (München: Matthes und Seitz, 1990)).

23 See for example, Matthias Weiss, ‘Vermessen — fotografische ‘Menscheninventare’ vor und aus Zeit des Nationalsozialismus,’ in Maßlose Bilder: Visual Ästhetik der Transgression (München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2009), p. 359.

24 Gemeinschaft (community) as opposed to Gesellschaft (society) was an integral paradigm of National Socialist philosophy in the form of Volksgemeinschaft (the people’s community). The individual was regarded as part of a whole national organism subsumed into a single organic being. Thus, each ‘cell’ (person) must be of the best quality and, in this ideology, racially echo the whole.

25 Remco Ensel, ‘Photography, Race and Nationalism in the Netherlands,’ in Paul Puschmann and Tim Riswick, eds, Building Bridges. Scholars, History and Historical Demography. A Festschrift in Honor of Professor Theo Engelen (Nijmegen: Valkhof Pers, 2018), p. 253.

26 Brandon Taylor and Wilfried van der Will, The Nazification of Art: Art, Design, Music, Architecture and Film in the Third Reich (Winchester: The Winchester Press 1990), p. 4.