Conditional Patterns in the Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Zakho

© Eran Cohen, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0209.05

A full picture of the conditional subsystem within a grammatical system is hard to come by and the issue is often given very limited space in grammatical descriptions. The case of the Christian dialect of Barwar (Khan 2008) is exceptional, since a relatively large chapter is devoted to conditional constructions (ibid., 1004–25). In this paper I intend to study conditionals in the Jewish dialect of Zakho (henceforth JZ) as well as discuss some general issues that come up during this investigation.

Although not always clearly stated, conditionals belong semantically to the domain of modality. This is sometimes overlooked because conditionals are traditionally classified, in grammatical descriptions, with other clause types such as different adverbial or subordinate clauses. This notwithstanding, they are a syntactic expression of modality, very similar semantically to other expressions which reflect different degrees of certainty, as the particle perhaps.

The objectives of this paper are: first, to explain the place of conditional constructions within epistemic modality; second, to provide a survey of conditional expressions in JZ; third, to discuss the relationships of the conditionals with other clause-types (concessive, temporal, relative); and fourth, to show the effect of the combination of conditional expressions and other epistemic expressions.

1. Modality in General

Although linguistic modality has been defined with respect to several parameters (e.g., subjectivity, or ‘speaker’s attitude’). The following definition summarises the conclusion of a paper that attempts a definition of modality (Narrog 2005), viz. that only the parameter of factuality is actually useful in distinguishing between what is modal and what is not:

Modality is a linguistic category referring to the factual status of a state of affairs. The expression of a state of affairs is modalized if it is marked for being undetermined with respect to its factual status, i.e. is neither positively nor negatively factual. (ibid., 184)

Modality is subdivided in different ways, but it is enough, in this framework, to keep the old division between deontic and epistemic modality.

1.1. Deontic Modality

Deontic modality is the type of modality covering will and obligation in non-factual utterances. The imperative form is the deontic expression par excellence. It always has this function, expressing different levels of the speaker’s will.

1.2. Epistemic Modality

The definitions for epistemic modality are less complicated and seem to cover the domain quite well. Nuyts (2006, 6, emphasis mine), for example, offers the following definition:

The core definition of this category is relatively noncontroversial: it concerns an indication of the estimation, typically, but not necessarily, by the speaker, of the chances that the state of affairs expressed in the clause applies in the world. In other words, it expresses the degree of probability of the state of affairs.

1.3. The Epistemic Scale

Ordinary conditionals are constructions that denote epistemic modality. As such, they reflect various points on the epistemic scale, representing different degrees of reality ascribed to the situation or event. As Akatsuka (1985, 636–37) points out:

The two conceptual domains, realis and irrealis, do not stand in clear-cut opposition, but rather are on a continuum, in terms of the speaker’s subjective evaluation of the ontological reality of a given situation. In conditionals, the S1 of if S1 can express the speaker’s attitude at any point within the irrealis division of the scale. In short, this epistemic scale reflects the speaker’s evaluation of S1’s realizability, ranging in value from zero (i.e. counterfactuals) to one (i.e. realis)

The definition is given higher resolution some twenty years later by Nuyts (2006,6):

As in deontic modality, this dimension can be construed as a scale—from absolute certainty via probability to fairly neutral possibility that the state of affairs is real. Moreover, if one assumes that the category also involves polarity, the scale even continues further on to the negative side, via improbability of the state of affairs to absolute certainty that it is not real.

The dimension of polarity (as presented in Taylor 1996) includes anything on the scale between affirmative and negative, namely, it is very similar conceptually.

Conditional expressions are semantically analogous to epistemic particles such as perhaps, or similar epistemic expressions like ‘he must be home now.’ They are all found on that same scale, which stretches between real and unreal, or between affirmative and negative. Dancygier (1998, 72, 82) explains that if marks the protasis clause as unassertable and consequently the apodosis is unassertable as well, both may be regarded as assumptions.1 In other words, neither the protasis nor the apodosis are a statement of fact. This issue seems important given the generally held view that a conditional protasis is analogous to various adverbial clauses and, accordingly, the conditional apodosis is equivalent to the main clause in these adverbial clauses. Note, however, that, unlike the latter, the apodosis of ordinary conditionals cannot exist without its protasis, otherwise it would not be conditioned.

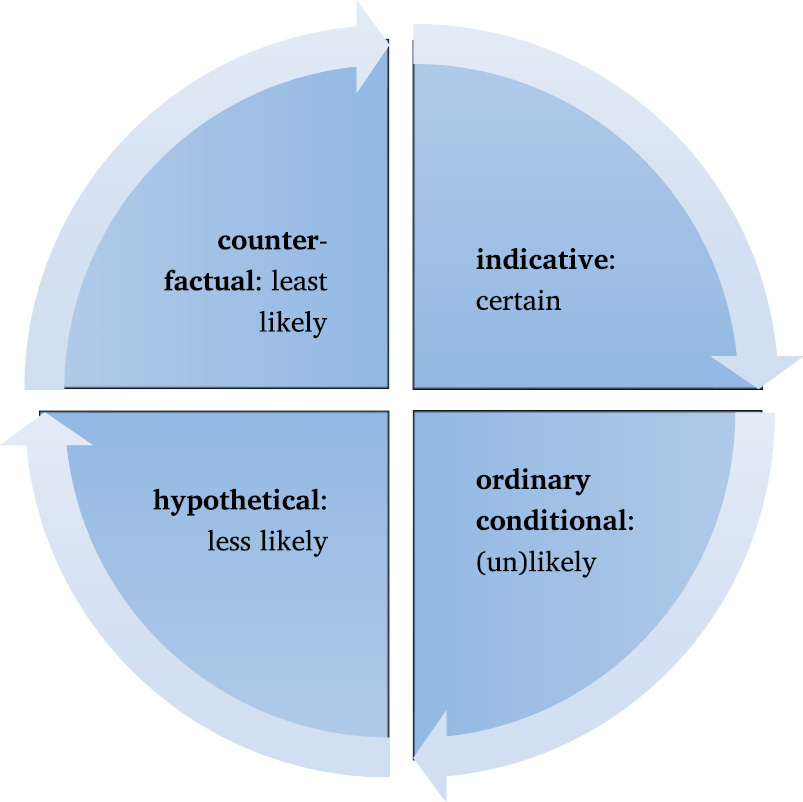

Illustration 1 of the modal paradigm shows where conditionals are located with regard to other expressions of modality:

Illustration 1: The modal paradigm (Cohen 2012a, 174)

|

1 indicative |

||

|

ordinary conditionals |

||

|

hypothetical conditionals |

||

|

counter-factual conditionals |

||

|

judgements |

||

|

interrogative |

||

The modality conveyed by ordinary conditionals is in fact one type of epistemic modality, and, therefore, fully comparable with other expressions of likelihood—probably, perhaps, surely, etc.

The scale relating to conditional structures, which also has to do with degrees of likelihood, is also represented in Illustration 2, where it is presented as a round scale in which both extremes virtually meet. This is because an expression of unreal conditional is very close to a negative factual statement.

Illustration 2: The hypotheticality scale within conditionals (Cohen 2012a, 174)

1.4. Technical Information

The following table serves as a legend for the different verbal forms in JZ:

Table 1: Legend for verbal forms

|

Simple verbal forms |

+ Backshift |

Function |

|

|

šqəl-le |

šqəl-wa-le |

plupreterite |

|

|

qam-šāqəl-le |

qam-šāqəl-wa-le |

plupreterite |

|

|

k-šāqəl |

general present |

k-šāqəl-wa |

|

|

p-šāqəl |

future |

p-šāqəl-wa |

counterfactual |

|

šāqəl |

šāqəl-wa |

||

The suffix -wa (glossed b) termed ‘backshift’ moves the predication back—mostly in time (when suffixed to present and past-denoting forms), but occasionally in modality, as happens with future-denoting forms and sometimes with subjunctive forms. The former denote counter-factuality, the latter has subtle functions and occasionally is an agreement to a past-denoting matrix verb.

1.5. Relation between Conditionals and other Epistemic Particles and Expressions

The particle balki ~ balkin ~ balkət meaning ‘maybe/perhaps’ is one of the carriers of epistemic modality. The link between a conditional notion and ‘maybe’ may not seem natural at first glance. Example (1) shows this link:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The initial condition is generic or habitual (see §3). The specifications (whether it is a boy or a girl) are in privative relations and hence similar to a real condition. Note that whereas in the first specification balkin ‘maybe’ is used, in the second the particle used is hakan ‘if.’ The co-occurrence of conditional and balki is further discussed under §4.

2. A survey of Conditional Expressions in Jewish Zakho

2.1. Apodosis

Conditional structures are in general complex modal expressions, that is, the likelihood of one state of affairs to take place is contingent upon the realisation chances of the other. They are an expression of likelihood, a point on the epistemic scale and this likelihood relates to the entire structure. The semantic essence of an ordinary condition is illustrated in (2):

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

There are two directive syntagms, i.e., two expressions of will in the example: ‘let my money be with you’ and ‘let the money be for you.’ However, it is easy to see that their semantic status is different. While the former is merely an expression of the speaker’s will, the latter is more of a permissive nature and, in addition, it is conditioned by external circumstances. That is, it depends on whether the speaker returns or not.

2.2. Conditional Forms and Values

There are two types of conditional form: patterns with an introductory particle and paratactic patterns. It is important to state that they are only partially related and the paratactic pattern is probably not derived from the other type.

‘‘Form’ refers to what the pattern consists of, namely, if one starts with the pattern headed by an introductory particle, one needs to specify the introductory particle as well as the forms occurring in the protasis and in the apodosis.

Several introductory particles occur in free variation, all consisting of the core element kan (< Arab. kān ‘he was’), often with some addition: ənkan, hakan, (i)zakan, īskan, without any apparent difference.

The forms commonly occurring in the protasis of ordinary conditionals are the subjunctive šāqəl and the preterite forms šqəlle and qam-šāqəlle. There are no temporal differences between the forms:

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

This is the essential profile of kan protases. The important point is that the forms šqəlle and qam-šāqəlle, although referring to the past in other constructions, do not do so here. In fact, they do not point at any time in particular, because temporal opposition does not exist in the protasis. The majority of conditional cases are predictive and consequently refer to the future (see (2)).

The conditional expression may occur in a subordinate environment, namely, the protasis may be associated with a subordinate apodosis (e.g. (11)).

The relationship of conditional clauses to modality is apparent from several angles. One of these is the relationship obtaining between a full protasis and a minimal or elliptic negative protasis following a directive or other expressions of obligation such as:

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

The lexical content of the protasis could either be expressed explicitly inside it (example[4], ‘if it is not ready…’) or, alternatively, be expressed outside it, as a command or obligation followed by an ‘empty’ protasis containing merely an indication of the possibility that something may not happen (example [5], the ‘if not’ strategy).

Present forms are rare in the protasis and refer to a persistent state of affairs. The apodosis is basically made up of either future pšāqəl or subjunctive (šud) šāqəl ~ imperative šqōl. That is, the normal opposition between the forms is modal, rather than aspectual or temporal. Rare present-like forms occur here with the present copula (e.g. īle ‘He is’), the predicative possessor (e.g. ətle ‘He has’) and the non-verbal expression of ability (ībe ‘He is able’).

2.3. Conditional Types

The predominant conditional type is the ordinary condition, which answers to the definition given above in §2.1.

Another type is the speech-act conditional, where the apodosis is not conditioned, but rather reflects a fact:

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

The factual apodosis substantially weakens the modality of these examples. The protasis merely serves as the background or explanation of the utterance in the apodosis. In example (6) it is an unconditioned fact that the sword of the giant woman (who is the speaker) is the only sword that would kill her. The protasis merely specifies in what circumstances it is important.

A concessive conditional is yet another type where the apodosis is factual:

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

The snake (who is the source of the utterance) is more or less making a vow not to move from his place for the man’s sake. This vow is unconditioned, not being contingent upon the protasis. Despite this difference, concessive conditionals still share a pattern with ordinary conditionals, as is shown below, §2.4.

In inferential conditionals, the protasis is the premise from which the conclusion in the apodosis is drawn, as illustrated in example . The particle xō~xū is used here to signal this inferential relationship.

2.4. Paratactic Conditional or Concessive Conditional Pattern

This pattern is a sequence whose basic functional value is conditional or concessive conditional (see Cohen 2007). Unlike the protasis with kan, this type of protasis only occurs with the subjunctive form šāqəl:2

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

These examples are representative of the construction in question in form and in content. Example (8)–(9) contain a subjunctive form that cannot be interpreted as a negative imperative (which is a common function of the 2nd person subjunctive). The only way it could be interpreted is as a conditional protasis ‘should you not….’ The negative form lak-šāqəl in the apodosis is the negative of both the forms k-šāqəl and p-šāqəl (and is thus glossed neg.npst).

The relationship with the pattern marked by kan is exemplified in the following pair of examples. The character is asked by strangers whether he is a believer or a heretic:

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Recall that the protasis with kan may consist of a preterite form as well, while in the paratactic pattern only the subjunctive form šāqəl is attested. Examples (10) and (11), however, have the same value here. Note that the conditional state of affairs in both examples is a expressed by a complement clause of ṣadli ‘I am afraid.’

Whereas the pattern with kan is essentially conditional, the paratactic pattern may be either conditional or concessive-conditional (table 2). The two values are differentiated based upon a particle, which occasionally precedes them: hama. The particle hama is otherwise a focus particle meaning ‘just.’ Here it has an entirely different function—it identifies the pattern #šāqəl—p-šāqəl# as conditional, that is, when hama precedes the pattern (i.e., #hama šāqəl—p-šāqəl), it marks it as a conditional.

On the other hand, when the particle šud precedes šāqəl, the pattern is positively identified as a concessive conditional. (Otherwise šud identifies the subjunctive form as syntactically independent.) The details of the pattern of the paratactic conditional are as follows:

Table 2: Conditional Patterns

|

Conditional |

Protasis |

Apodosis |

|

|

paratactic |

(hama) |

±future: (p-šāqəl~lak-šāqəl) |

|

|

kan |

±future: (p-šāqəl~lak-šāqəl) |

||

Note that the order protasis—apodosis is strictly kept with the paratactic pattern but not with the construction with the conditional particle. Another point is that in view of the obvious differences between both patterns, the paratactic pattern does not seem to have been derived from the pattern with an explicit conditional marker.

2.5. Counter-factual Conditional Patterns

Counter-factual expressions are located at the far end of the modal scale, very close in fact to the point of negative factuality (see Illustration 2). They cover events (or states) that did (or will) not happen, but which are still not reported as factual but rather through some modal filter:

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

A virtually similar clause is ‘I didn’t know and therefore I came.’ This latter clause is, however, factual and does not impart the regrets and wishes of the speaker implied in the counterfactual expression in example (12). The opposite order, apodosis—protasis, is also attested:

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

In (13) two apodoses are conjoined in a complement clause of not-knowing (which is often very similar to the expression of an indirect question). One is factual (‘what happened’) and the other is a counterfactual conditional (‘what would have happened if…’). The latter conveys an alternative universe.

The pattern of the counterfactual conditional, which is common in NENA, is presented in Table 3:

Table 3: Counterfactual Conditional Pattern

|

Protasis |

Apodosis |

|

|

kan |

±šāqəl-wa |

±p-šāqəl-wa~lak-šāqəl-wa (backshifted future) |

The form p-šāqəl-wa is used in general to express counterfactuality, also outside the domain of conditionals—for instance, in circumstantial expressions (see Cohen 2015, 269–70).

Unlike ordinary condition, the protasis of counterfactual conditionals may interchange with a simpler expression:

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Such ‘adverbial’ substitutes (underlined) are hinted at by the form of the apodosis. The form p-šāqəl-wa is a rare form outside the counterfactual apodosis. JZ has the following paradigm for the counterfactual protasis:

Table 4: The Counterfactual Protasis Paradigm

|

Protasis |

Gloss |

Apodosis |

|

kan šāqəl-wa |

‘if he had taken’ |

p-šāqəl-wa ‘he would have taken’ |

|

laxwa |

‘otherwise’ |

|

|

pqəṭli |

‘(even) for my death’ |

The ultimate significance of this interchangeability is that, unlike the protasis of the ordinary conditional, deemed as sui generis, the counterfactual protasis is comparable with smaller entities (as are, for instance, many subordinate clauses).

More common is the asyndetic counterfactual conditional pattern:

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

The expression šxēra uxudēra does not seem to be part of the construction. Note that it is actually connected by ū to the conditional pattern. The pattern in this case consists of five clauses in the protasis and one in the apodosis.

3. Relationships of the Conditionals with other Clause-Types

In §2.3 above, several types of conditionals were explained and exemplified. In certain cases one finds a structure similar to a conditional pattern, but the function is different. For instance, conditional-like dependencies sometimes occur within a descriptive narrative passage:

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Example (17) is a conditional-like structure. It is, however, different. It is clear that the structure shows neither modality, nor counterfactuality, but only an interdependency between two states of affairs, which are in fact two factual, regularly recurring states or events. What makes this clear is the form kšāqəlwa in the apodosis (whereas in the standard counterfactual conditional pattern one would expect a šāqəlwa—pšāqəlwa sequence, as in Table 5, with the backshifted future).

The next example is similar; although it does have the right apodosis form (pšāqəlwa), the so called protasis is introduced by dammət ‘when’:

|

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Note that conditionals are not typical of narrative. They are common in dialogue, and possibly also in narratorial comments, but not in the stream of events. Another similar example is worth considering:

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

All three examples (17)-(19) refer to generic a state of affairs. Note that in these cases conditional, temporal and relative clauses converge and are almost interchangeable in this context.

Table 5: The Structure of Narrative Conditionals

|

Example |

Protasis |

Apodosis |

Formal type |

Type |

|

|

(12), (13) |

(ha)kan |

šāqəlwa |

pšāqəlwa |

counterfactual |

|

|

(16) |

šāqəlwa |

pšāqəlwa |

patterns |

||

|

hakan |

šāqəlwa |

kšāqəlwa |

generic |

||

|

dammət |

šāqəlwa |

pšāqəlwa |

temporal |

||

|

(dīd) |

šāqəlwa |

kšāqəlwa |

relative |

||

Where conditional, temporal and relative forms functionally converge, the result is a non-modal, generic dependency. This genericity goes hand in hand with character description—not an individual occurrence, but rather a permanent feature, as in example (19), describing the sheikh.

4. The Combination of Conditional Expressions and Epistemic Expressions

Lastly, in the following example two similar expressions of possibility—conditional and the expression of epistemic possibility—co-occur:

|

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

The explanation for this is that these expressions do not have the same function. The particle balki has its own function in the example. The conditional particle possibly signals two things: first, that both events or states of affairs are merely possible; and second, the relationship between them:

The only assertion that is made in a conditional construction is about the relation between the protasis and the apodosis (Dancygier 1998, 72, emphasis mine)

This assertion is best felt when its existence is shaken by a modal particle which has the entire construction in its scope or by a question. The modal particle in our case refers specifically to the relation between the protasis and the apodosis, namely, it shakes the dependency between the protasis and the apodosis, expressing doubt about this relationship.

5. Conclusions

This paper provides a description, classification and discussion of the various conditional phenomena in the Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialect of Zakho.

- The different conditional types are explained and exemplified:

- Ordinary conditionals, which denote different degrees of epistemic modality (these constitute the bulk of the examples);

- Inferential conditionals, where the conclusion in the apodosis is drawn from the premise expressed in the protasis. The inferential relationship is marked by the particle xō~xū.

- Speech-act conditionals, which rather than expressions of modality, are in fact a structure where the protasis serves as the background for the utterance in the (non-conditioned) apodosis.

- Concessive-conditionals (‘even if...’), where the protasis expresses epistemic modality, but the apodosis, on the other hand, is not conditioned.

- Two patterns expressing ordinary conditionals are presented; one with a conditional particle at the head of the protasis, and another where no conditional particle is involved (which we termed paratactic) are presented. Each pattern is formulated based on the forms which appear in the protasis and the apodosis. They are different in their semantic scope—the paratactic pattern can express either a conditional or a concessive conditional.

- Counterfactual conditional patterns are similarly characterised. In addition, a special trait of this conditional type is discussed, namely the fact that a couple of expressions can take the place of the counterfactual protasis without changing the function of the entire pattern.

- A special function of similar constructions termed ‘narrative conditionals’ is examined and compared with counterfactuals. Their function is explained vis-à-vis other clause types. It is concluded that they are generic expressions.

- Finally, the co-occurrence of ordinary conditionals, which express epistemic modality, with seemingly synonymous epistemic particles (e.g., ‘perhaps’) is analysed and the different functions of each are distinguished functionally.

References

Akatsuka, Noriko. 1985. ‘Conditionals and the Epistemic Scale’. Language 61: 625–39.

Cohen, Eran. 2007. ‘Zakho Neo-Aramaic and Old Babylonian Akkadian: The (Concessive-)Conditional Pattern’. In Studies in Semitic and General Linguistics in Honor of Gideon Goldenberg, edited by Tali Bar and Eran Cohen, 159–77. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 334. Münster: Ugarit.

———. 2010. ‘Marking Nucleus and Attribute in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic’. In Proceeding of the VIII Afro-Asiatic Congress (September 2008, Naples), Studi Maghrebini (Nuova Serie), VI: 79–94.

———. 2012a. Conditional Structures in Mesopotamian Old Babylonian. Languages of the Ancient Near East 4. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

———. 2012b. The Syntax of Neo-Aramaic: The Jewish Dialect of Zakho. Gorgias Neo-Aramaic Studies 13. Piscataway: Gorgias.

———. 2015. ‘Circumstantial Clause Combining in the Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Zakho’. In Clause Combining in Semitic: The Circumstantial Clause and Beyond, edited by Bo Isaksson and Maria Persson, 271–93. Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes. Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden.

Dancygier, Barbara. 1998. Conditionals and Prediction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Khan, Geoffrey. 2008. The Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Barwar. Handbook of Oriental Studies I-96. Leiden: Brill.

Narrog, Heiko. 2005. ‘On Defining Modality Again.’ Language Sciences 27 (2): 165–92.

Nuyts, Jan. 2006. ‘Modality: Overview and Linguistic Issues’. In The Expression of Modality, edited by William Frawley, 1–26. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Palmer, Frank. 1986. Mood and Modality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, John. 1997. ‘Conditionals and Polarity’. In On Conditionals Again, edited by Angeliki Athanasiadou and René Dirven, 289–306. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Corpus

[bare numbers] = Polotsky, Hans J. 1944–1947. Unpublished Zakho Texts. Jerusalem.

MA= Meehan, Charles and Jaqueline Alon. 1979. ‘The Boy Whose Tunic Stuck to Him: A Folktale in the Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Zakho (Iraqi Kurdistan)’. Israel Oriental Studies 9: 174–203.

SAG= Sabar, Yona. 2007. ‘Agonies of Childbearing and Child Rearing in Iraqi Kurdistan: A Narrative in Jewish Neo-Aramaic and its English Translation’. In Studies in Semitic and General Linguistics in Honor of Gideon Goldenberg, edited by Tali Bar and Eran Cohen, 107–45. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 334. Münster: Ugarit.

1 For a similar view, see Palmer (1986, 189): ‘Conditional sentences are unlike all others in that both the subordinate clause (the protasis) and the main clause (the apodosis) are non-factual. Neither indicates that an event has occurred (or is occurring or will occur); the sentence merely indicates the dependence of the truth of one proposition upon the truth of another.’

2 The subjunctive form in the first part occasionaly denotes temporality. For instance:

|

āwa |

ṭāweʾ |

b-ẓabḥ-an-ne |

|

nom.3ms |

sbjv.fall.asleep-3ms |

fut-slaughter-1fs-3ms |

|

‘(when) he falls asleep, I shall slaughter him’ (MA 12.2) |

||

3 The full form is b-yāw-ən-nox.

4 The form dīlu ‘they are’ (as well as any other copulas which are prefixed by d-, i.e., dīwın vs. wın ‘I am’) are copula forms that occur after any element in the construct state (glossed cst). It is for this reason that they are referred to as attributes (which is the basic function of the second part of a genitive construction) and are glossed accordingly (attr). See Cohen (2010, 90–93) and (2012b, 119–21).