8. Matriarch (1945–1956)

© Lucy Pollard, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0215.08

In the spring of 1942, the composer Benjamin Britten and his partner, the tenor Peter Pears, had returned from the United States where they had spent the first years of the war. Britten already owned the Old Mill in Snape, and, until 1948, was to spend around half of his time living and composing there.

Music had always been one of Margery’s passions, as it had been Stephen’s also: in the last few months of the war, raising the initial funding from family and friends and with local authority administrative help, she set up the Suffolk Rural Music School in Stephen’s memory.1 The Rural Music Schools movement had arisen out of the adult education movement of the nineteenth century: the first such school, in Hertfordshire, was founded in the late 1920s by Mary Ibberson and had a close link with the Settlement in Letchworth Garden City.2 It not only matched up pupils with peripatetic music teachers, but also made instruments available.

In June 1945, in the cause of the Suffolk school, which would be the seventh, Margery wrote to Britten, a staunch advocate of amateur music-making, to ask him to become honorary music advisor to the school. He agreed to do so and, together with Pears, gave a number of benefit concerts in aid of the school. It was not long before Britten and Margery were addressing each other in affectionate terms. Musically, Margery was determined not to settle for second best: after one ‘atrocious’ concert (artists unrecorded), she wrote to Britten: ‘I just don[’]t believe that it is any good gett[i]ng less than the very BEST’. She would have liked to be able to call on Casals, Arrau and Toscanini!

According to the fragmentary memoirs Margery wrote in her old age,3 it was she who suggested that one of the Britten/Pears concerts should take place in Aldeburgh’s Jubilee Hall, an idea that initially caused hilarity from Britten and Pears, who said that Aldeburgh would never provide an audience for a concert of classical music. It went ahead, however, and was a great success. Margery and Britten, and Fidelity Countess of Cranbrook4 who became president of the Suffolk Rural Music School, shared a conviction that amateur musicians should aim for the highest musical standards of which they were capable. When Britten’s cantata Saint Nicolas received its first London performance in June 1949, the choir included pupils from the Suffolk school.

The contact between Britten and Margery led to a long friendship, although eventually Margery became, to her distress, one of his many ‘corpses’, as the friends he dropped came to be known. However, for some years it remained a fruitful and affectionate relationship, and Margery retained her admiration for him and his music until the end of her life. The sentiment she expressed in a letter of 24 January 1947, ‘[w]hat a tragic muck mankind can make of its civilisation and knowledge and power, and with what thankfulness one thinks of you and Peter [Pears] who are making a constructive and abiding contribution’, never changed on her side.5 On 1 June 1962, the day after hearing the first performance of his War Requiem, which spoke to Margery’s deepest humanitarian values, she wrote to Britten:

That is a sublime work, exquisitely performed. It brought back all the heart-aches and yearnings of two wars, — and revivified the dwindling hopes for the future. I haven’t been so deeply moved for many many years.

In the autumn of that year, she went to London to hear it again in Westminster Abbey.

Margery remained as Vice-President of the Suffolk Rural Music School for some years, but in 1947, a new possibility was coming over the horizon, a long-term plan that was to engage much of her energy into the 1960s. Britten and Pears, returning from performing at the Holland Festival, conceived the idea of holding their own festival in Aldeburgh — a project that must have begun to seem possible partly as a result of the success of the Jubilee Hall benefit concert the previous year. On 4 September Britten wrote to Pears:

I saw Marjorie yesterday afternoon — she isn’t well, bad lumbago — but I think the ‘Festival Idea’ has cheered her — she thinks it the idea of the century, & is full of plans & schemes. We haven’t been over the Jubilee Hall, but I’m full of hopes. Do you know she got 390 in for our concert last year?.

At the first meeting of the committee that was formed to take the idea further, which took place in October 1947 with Fidelity Cranbrook in the chair, Margery made a personal gift of £100 to be used to cover minor expenses. This is not only a measure of her gratitude to Britten for his support of the Rural Music School, but also an indication of her enthusiasm for the idea of a local festival.

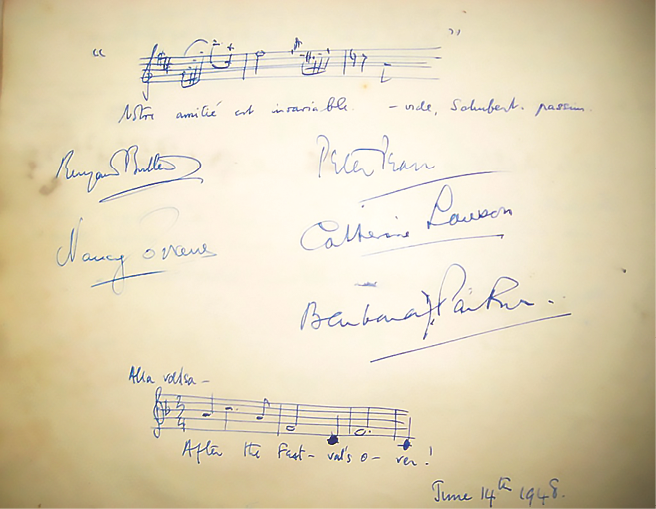

Her contribution was practical as well as financial: when the first Aldeburgh Festival took place in June 1948, in addition to buying three tickets for every performance, she sorted out a green room for the artists in a local care home, organised refreshments, put up posters in local shops and arranged stewards for the festival club (a single room in one of Aldeburgh’s hotels). In her Iken Hall visitors’ book, there is a page signed by Britten, Pears, the singer Nancy Evans and others to celebrate the first festival, with a musical quotation in Britten’s hand and the words ‘Notre amitié est invariable — vide Schubert, passim’. It was sad for Margery that his friendship did not remain ‘invariable’, though she was by no means his only friend to be dropped: in her case, the later coolness may have been a result not only of Britten’s psychological need to keep his composing space absolutely sacrosanct, but also of the fact that Imogen Holst, who became his right-hand person, found Margery tiresome. But while Margery and Britten were still close, he made the big dining room chimney of Iken Hall the setting for one of his first works for children, Let’s Make an Opera.

Fig. 20. Page from the Iken visitors’ book. Photograph: the author (2016).

Margery remained on the festival committee for sixteen years, through some difficult times: in 1953, for example, there was a question mark over whether there would be a festival at all, because the pressures put on Britten by his commission to compose an opera for the coronation were so great.6 After the first year, the committee itself was, to some extent, side-lined by the establishment of a separate executive council, which took the more important decisions. In spite of this, Margery continued to worry like a terrier over the festival’s financial viability, making various suggestions over the next year or two about how to lure subscribers with the bait of priority booking, and how to find more guarantors, since the festival ‘did not exactly make a profit’.7 It was felt that ticket buyers and potential ticket buyers did not understand that ticket sales did not cover the costs of putting on performances.8

With her strong sense of her family inheritance, Margery was deeply rooted in Aldeburgh and its hinterland, which soon provided another cause for her activism. In the mid-1940s, the old rectory (at some stage renamed The Anchorage) was bought by Gabriel Clark. There had traditionally been a footpath from Snape along the south bank of the Alde to Iken church but Clark closed the last section of the path so that walkers had to detour via the road to reach the church. Margery, outraged, fought a long but unsuccessful battle to reopen it. The case went to the County Court; Margery’s solicitor, her brother Douglas’s son Roderick, believed (though there is no independent corroboration of this) that one local inhabitant, the river pilot Jumbo Ward, had been bribed to give false evidence.

Whatever the facts, there were several acrimonious encounters between Clark and Margery or her family and friends. On 30 January 1946, Margery wrote to Brenda Gillingham, wife of Stephen’s old school friend Anthony:

Ben Britten, Ursula Nettleship9 & I did the ‘grind’ again last Sunday! Clarke [sic]10 met us at the fallen tree & after the usual sort of ding-dong argument backwards & forwards he became extremely rude to me, saying it was well known that I ought to be in trousers, & that he sympathised with my husband having left me etc. etc. Ben was so angry that there was nearly a fight. Clarke threatened to use violence if we went on, — but I ignored him & we went on, & he merely followed us hurling abuse at us, of the above sort.

She goes on to say that the County Council had appointed a sub-committee to settle the dispute, but ‘as Ben said it is extraordinarily depressing to think of Clarke as my only neighbour’. Many years later, Britten’s niece remembered —

that horrible Clarke, and the fight to keep the path along the river to the church open. We were walking along it one day with my mother and Margery, when he came towards us with large and frightening dogs. My mother wasn’t as tough as Margery, and she said we should go back, so we did. It was a long battle and I remember the disappointment when ‘we’ lost. I was only a child but I remember it very clearly.11

Margery was not the only person to fall out with Clark. In 1948, he was elected to the Parish Council, on which Margery also sat, but when he arrived for a meeting, according to her account, the chair walked out in protest. Furthermore, when she went out to try to persuade him back in, he said

‘Do you want to see murder committed, ma’am?’ I said I wouldn’t mind but I did not think that the Parish Council held in Jumbo Ward’s house was a very good place. So he said ‘Well let me find my gun, and I’ll take the man outside and do it there. He is like a snake in the grass to me, and I won’t sit in the same room with him’.12

There was evidently a pro-Clark faction as well, since shortly after this, he became chair of the Parish Council and stood for the Rural District Council. Margery thought she should probably resign from the PC but ‘can’t make up my mind to hand the whole caboodle over to the enemy’.13 It is not clear how long she stayed.

Footpaths continued to cause local ructions long after Margery had left Iken. In 1961, her son Charles wrote that he had walked through Tunstall Forest and across the Iken estate —

where we were stopped by the new owner, Gill, down by his new irrigation reservoir […] in the dip of the land where there used to be an old well. He evidently kept a watch (with field glasses) on that side while his wife watched the cliff side (she stopped Stella14 at the top of the cliff). Gill came down to stop us […] After some cool feelers on either side I introduced myself and asked him his name — I had forgotten that Mann had even sold the estate. Then we became friends, he pointing out what footpaths he has purposely left open (not nearly enough, of course) and I telling him the old route of the sailors’ path. We found some common ground in slating Clarke’s attitude and the action of the previous owner in destroying hedges and woods; Gill has planted some new ones as wind-breaks. He is not a bad sort I think.15

A couple of years later, Margery was writing to one of her grandchildren that —

The whole business is a farce, because there is a tr[i]ennial enquiry into which paths are public and during the three years that the footpath committee are considering the matter farmers plough up the paths & ‘commons’ & put barbed wire around them! As the Iken farmer has done.16

It is certainly true that from the late 1950s, much of the land around Iken Hall that had been open heath, covered with bracken, was ploughed up and turned over to agricultural land. A big gravel pit across the road opposite the house also disappeared. Perhaps from the agricultural point of view this was justified, although it changed the character of the countryside. As early as 1945, when the battle area was still in place, Charles had written:

I still feel that the place would be more beautiful if its natural beauty were supplemented by a modern agricultural community. That would give it a richer and more varied character altogether, without in any way marring your bit of heath or the marshes or the river itself.17

He hoped that even if the battle area was retained, the boundaries could be redrawn so as to give a clear route to the Slaughden ferry.18

Margery engaged more positively with local government when, in the light of her North Kensington experience, she was co-opted to the County Council’s health committee,19 on which she sat for many years. She also remained active on the committee of the North Kensington clinic until 1956, making frequent trips to London to attend meetings.

She had not lost her taste for foreign travel, and in 1948, she made a trip to Italy and Malta where she visited Stephen’s friend Tina Price and her parents, whom she had entertained at Iken in 1946. In the winter of 1952–1953, she took advantage of the fact that Charles, now a malariologist, was working for the World Health Organisation and living with his family in Lebanon. It was a good opportunity to escape from Christmas too, which usually meant a large family party at Iken but inevitably reminded her that Stephen was no longer among them. On 6 November 1952, she wrote to Britten describing how she loved visiting —

Aleppo, Crusader castles, Phoenician ports, & the magnificent memorials of the centuries of the great Roman peace in this land. It is all incredibly beautiful. The landscape itself, with high mountains, - the sea & the rich fertility of the plains, - on the very edge of the desert, makes the setting of the buildings quite breath-taking. And through it all this great antiquity & space & depth.

She had been bowled over by the beauty of Syria and its rich history. In contrast, she was having a ‘nightmare puzzle’ trying to arrange a visit to Israel (via Cyprus), for which she had deliberately acquired a second passport to avoid the problem of showing that she had been in an Arab country.

How absurd it is, — but at the same time how insoluble. I shall probably end up in some Jordanian dungeon for trying to smuggle myself & small suitcase across the border.

She was quite capable of mischievously producing the wrong passport just to see what might happen, but in fact the only hitch seems to have occurred in Egypt at the end of her tour, when she had —

an exciting and rather dangerous encounter with the Egyptian police, […] who had been opening my letters to the P. and O office in Port Said, and thereby discovered that I had visited an enemy country immediately before coming to Egypt to catch my P. and O boat home. However we finally parted on the best of terms, and the impressive Major Achmed Hassan, chief of the Security police expressed the hope that I would look upon him as my Egyptian son! a quick jump from the role of gaoler which he had been playing for two so[li]d hours beforehand.20

One small perk of visiting the Middle East was her discovery that an Arab headband was just the thing for keeping her hair in order: she used the one she acquired on her Lebanon trip for the rest of her life. From her girlhood into her old age, she had beautiful waist-length hair, of which she was justly proud, and which Dick Mitchison had specially loved. Although sometimes an eccentric dresser, she cared very much about her appearance. Rather surprisingly, given her feminism — but perhaps partly because of being very overweight — she never gave up wearing a corset.

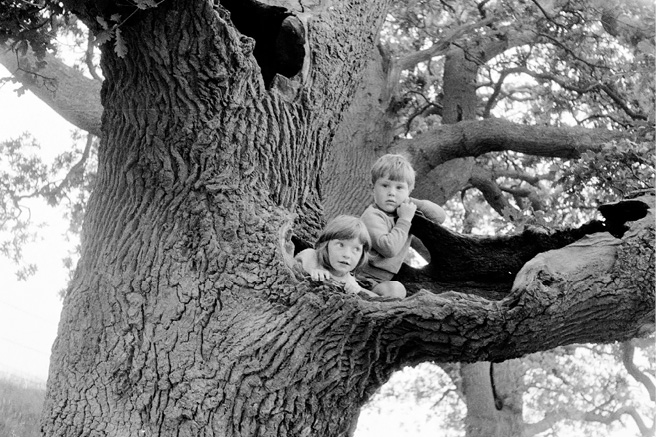

One of the most important aspects of Margery’s life in the post-war years was being a grandmother, friend and hostess. Having ended the war with three grandchildren, by 1958 she had thirteen. In 1953, she had written that she could ‘rest with honour on my oars, and take a little timely grandmotherly birth control’, but she was not to be allowed to do so quite yet. Charles had two by his second marriage, Ronald had three, and Cecil eventually had six. If Margery had had a lot of failings as a mother, she was the best of grandmothers, and Iken was an almost perfect setting. In the 1950s, children spent a great deal more time outdoors, and with more freedom, than their counterparts in the early twenty-first century. Iken offered the river for sailing, mudlarking and swimming, trees for climbing, sheds for messing about in and quiet country roads for cycling. There was an area in the corner of the garden where visiting families, for whom there was no room in the house, could pitch their tents and, at some stage, Margery acquired an old gypsy caravan which children could use as a play house or to sleep in on summer nights.

Fig. 21. Iken oak with grandchildren. Photograph: Ronald Garrett-Jones (late 1950s).

Indoors, the big double drawing room was divided by curtains, making a perfect stage for grandchildren to put on plays, music being provided by a magnificent musical box or live on the piano by Margery, and interval drinks consisting of water mixed with drops of red or green colouring for ‘wine’. In this room, too, Margery regularly set up a party-piece called ‘the Prince of Crim Tartary’, which enchanted all the children who saw it. A table was put in front of the closed curtains, covered with a rug, and with a stool on it. The Prince was created by two adults standing one behind the other, behind the table. The front adult made the head, body and legs of the Prince, wearing his boots on his or her hands, while the back one put his or her arms through under the armpits of the front one to make the Prince’s arms. He wore a turban and, on his ‘feet’, a pair of beautiful embroidered children’s boots brought back from China and given to Margery by Eileen Power.21 This small, dumpy but magical personage would answer questions, give out presents, do a stately dance, and demonstrate that he could remain sitting cross-legged in the air if his stool was removed from under him. At the end of his appearance, his audience were told they must close their eyes while he flew away on his magic carpet. His spell was such that one grandchild recorded in adulthood ‘I fully believed in him […] I remember looking out of the window [when he left] […] there was a moon and scudding clouds, and we definitely caught a glimpse of him as he sped away’.22

Fig. 22. Margery with her Land Rover. Photograph: Francis Minns (1953). Courtesy of Julian Minns.

Fig. 23. The Prince of Crim Tartary’s boots (now in the Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood, Bethnal Green). Photograph: the author (2011).

Friends, family and acquaintances flocked to Iken and Margery kept up with many of her children’s friends as well as her own. Any breach with her Jones in-laws had long been healed, so Gil and Hilda in particular came from time to time, the latter sharing a passion for gardening with Margery. Many German and Austrian names crop up in the Iken visitors’ books, as do the names of friends from all periods of her life. She was always willing to offer sanctuary to friends in trouble: an example is her kindness to two other divorced friends, Betty Waddington and Angela Wheeler.23 Although she had domestic and some gardening help, she did virtually all the cooking herself, which cannot have been easy when food was rationed, as it continued to be until 1954. Everyone was excited one Christmas when a big sack of tinned food arrived from the Rothschilds, who had settled in New York. But even during the war years, the visitors’ books sometimes record the names of thirty or forty people a year, excluding her extended family. In 1946, the number topped fifty. There were always musicians among them: Annie Newson (who lived in the village and did domestic work for Margery) later remembered her delight at hearing Kathleen Ferrier sing, although Ferrier’s name does not appear in the visitors’ book as she probably came in a day with Britten and Pears and did not stay. Some of the musicians were performers at the Aldeburgh Festival, like the boys from a Danish choir who contrived to go mudlarking in their singing clothes and had to be laundered in a hurry— just the kind of challenge relished by Margery.

In 1942, the year in which he and Margery’s daughter Cecil married, Martin Robertson had written an acrostic poem in the Iken visitors’ book on the words ‘Spring Rice of Iken Hall’. It ends with these lines, to be amply fulfilled in the years to come:

Here kindness does not fail

At this or any pass:

Long live this house into the thaw of peace;

Long live the name ‘Spring Rice of Iken Hall’.

Margery could be an autocratic host as well as a generous one. On one occasion, Ursula Nettleship and her cat Humpy were guests and Margery had cooked halibut for dinner. When handed her plate, Ursula immediately divided her portion of fish in half and made to give one half to Humpy — at which an outraged Margery said she had not cooked an expensive fish like halibut in order for cats to eat it, and if Ursula didn’t want all of her helping she could give it back. However, she also loved Ursula for her disregard of convention: once, when Ursula wanted to go for a swim in the river but had not brought a costume, Margery offered to lend her one. Ursula dismissed that idea, saying that her knickers would be quite good enough (though she generally regarded even knickers as unnecessary, since she was happy to swim naked).

If friends were of huge importance to her, there is a gap in the evidence when it comes to her sex life after her return to Suffolk in 1936 in her late forties. Whether this is because it was over and she fulfilled her emotional needs through her friendships, her family relationships and her many activities, or whether it has simply vanished from the record, we will probably never know.

When the east coast of the United Kingdom was struck by terrible floods in early 1953, Margery was anxious to help. However, she learned that all the homeless families had been found accommodation and she recognised that Iken was impracticable for anyone without a car. Like others, she was deeply shocked at the devastation and loss of life. She described the situation in the village:

Even this village is flooded in its low lying parts, and the whole of the marshes between here and Aldeburgh on both sides of the river and right down to Orford are still deep in water. It is not true that the river made a new mouth for itself. There are 14 large breaches in the mud wall on the Aldeburgh side between Slaughden and the brick kiln dock. The river poured through these, and the sea came over the road between the end of the town and Slaughden quay and with each tide brought of course thousands of tons of shingle, as it always does, so it did not dig a new [mouth] for the river, but merely joined the river over the road and the marshes. Bull dozers and low tides have done their work since last week-end, and at present the sea is not coming over any more. The water [i]n the marshes is lower, because of the lower river tides, but it is still all a [huge] lake coming right up to the wall at the bottom of the old kitchen garden of Gower house!24

It was not the first bad winter experience. In March 1947, during the worst winter of the century up till then, she recorded terrible blizzards and blocked roads, snow two-feet-deep in her garden and no water supply or coke for the stove (but she had very much enjoyed getting a lift back from London in Britten’s Rolls Royce). In February 1949, Cecil was at Iken expecting her third child. The second had been born there without any problems,25 but this time she haemorrhaged very badly and had to be rushed first to Ipswich Hospital and then to Colchester because Ipswich had no supply of blood for her blood group. The following day there was a dreadful storm, and Margery struggled with awful driving conditions to take her son-in-law to see Cecil. She was an audacious driver, though not a good one. She had driven her nursery children around in an open-topped car, but in about 1950, she acquired a Land Rover, which meant she could (and did) drive on rough farm tracks as well as roads. From the nursery days, she had used her car to tow a trailer: if she had lots of children in the house, she delighted them by ferrying them about in the trailer.

In the early fifties, she was beginning to get tired. She was very overweight and suffered badly from rheumatism and back pain, although it did not stop her cooking or gardening or undertaking any of her other activities. On 8 October 1951, when she was sixty-four, she wrote to Brenda Gillingham that Cecil was expecting her fifth child (as Brenda too would soon be) and ‘I am a little daunted at the thought of yet another, when the holiday season comes round again’. The following autumn, again to the Gillinghams, she confessed that Cecil and her children ‘have first call on my accommodation and personal energy, which does not increase with the years’.26 She wondered about letting one end of the house to a young couple to provide help, since ‘the time has nearly come when I can’t cope with 12–14 people at a time as I have been doing for this summer for about three months’. And yet, she suggested that if some children were willing to camp, she could have Cecil’s family and the Gillingham family to stay at the same time — in the summer of 1953, this would have meant ten children in total.

Margery continued to take an active interest in the work of the North Kensington clinic, wholeheartedly encouraging and supporting the liberal attitude prevalent among its staff which is illustrated by the trajectory of the careers of several of them. Margaret Pyke, clinic secretary who succeeded Trudie Denman as chair of the Family Planning Association in 1954, became, in 1966, a director of the Brook Advisory Centres which gave advice to unmarried people. Helena Wright, who in her earlier life had been a medical missionary, did not disapprove of pre-marital or extra-marital relationships (of which she had more than one herself). Joan Malleson campaigned for abortion law reform.

A turning-point in the respectability of contraception, if only for married couples, came in 1955 when the Minister of Health, Ian Macleod,27 bravely (in the context of the time) visited the clinic. This came about because Lady Monckton, a member of the executive committee of the Family Planning Association (FPA), was a family friend of Macleod’s and introduced him to Margaret Pyke. The press turned out in force for the occasion, and the audience included mothers and children, as one of Margery’s letters refers to babies crowing during his speech. On the same evening, Pyke appeared in a television programme,28 and the following day, a Times leader celebrated the existence of a family planning service ‘as a voluntary movement, used by the public health services within defined limits, but remaining free of control or direction by the state’.29 The leader-writer also recognised that family planning services were concerned with many different factors that contribute to ‘wise and happy parenthood’ including infertility as well as contraception.

Fig. 24. Ian Macleod, Minister of Health, visits the North Kensington clinic in 1955. Margery is on the right and the mayor of Hammersmith in the centre. Photograph: Wellcome Collection SA/FPA/NK 237 (1955).

A file of North Kensington correspondence dating between 1954 and 1956 shows Margery as chair of the committee interested in every aspect of the clinic’s work. The many subjects covered include publicity, a proposed special clinic for the treatment of vaginismus, discussions about women unsuited to using the cap, the annual report, funding, international links, a project on the history of the movement and research into new methods of contraception. Here and there personal issues are mentioned, making it clear how busy she was in other ways too. In June 1954, she reports having four Aldeburgh Festival guests staying, with seven more due to arrive. On 20 June, she mentions that earlier in the week she had nineteen people sleeping in the house. That autumn, she looked after one grandchild who had had scarlatina and another who was recovering from a serious illness; in the following year, she cared for a third grandchild who was in quarantine for measles. At one point in July, there were six small children in the house, in this case, presumably, with one or more parents.

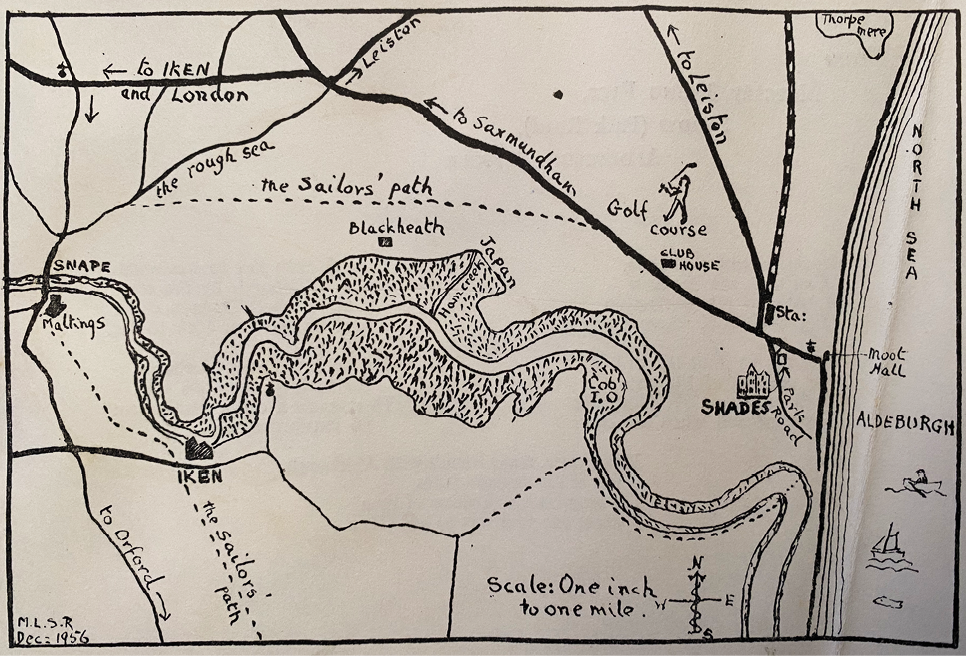

During this time, Margery was also worrying about whether she would be able to stay at Iken: her landlord was anxious to get her out, though he could not legally do so, so ‘unless the ideal house, slightly smaller and equally well placed, comes into the market, there I stay I hope till my coffin is [taken] out of it’.30 Nevertheless, she was beginning to find it difficult to manage house and garden; in 1956, with the help of a loan from her landlord, she bought a house on Park Road in Aldeburgh (in the same road as her parents’ old house, Gower House) that had also, very appropriately, been built by her grandfather Newson. On a beautiful October day, when the river looked golden, Cecil and some of her family came from London to help her with a move that — after twenty years — was a sad occasion, though they accepted that it was the right thing to do. In honour of the ghosts of her ancestors, Margery named the new house ‘Shades’.

Fig. 25. The map made by Margery when she moved from Iken to Shades in 1956. Photograph: the author (2020).

1 Mary Ibberson, For Joy that We are Here: Rural Music Schools 1929–50 (London: Bedford Square Press, 1977). The Suffolk school no longer exists as an independent entity, but much of its work is carried on by Snape Maltings.

2 The Settlement was (and is) an adult education organisation founded in 1920. Ibberson was the sub-warden and ran a music course there before founding the Rural Music School.

3 Margery Spring Rice, fragmentary memoirs, recorded 24 November 1968 by Sam Garrett-Jones, transcribed 12 January 2006 by Sam Garrett-Jones.

4 Fidelity’s father, Hugh Seebohm, a banker, had been treasurer of the first Rural Music School. Margery introduced her to Britten. The Seebohms were a Quaker family in Hitchin, and Hugh’s father Frederic had been involved in adult education.

5 The correspondence between Britten and Margery is owned by Britten Pears Arts and is housed with the archives at the Red House in Aldeburgh, Britten’s final residence.

6 At the time of writing, the Aldeburgh Festival has been going for seventy years without a break, though very sadly, owing to the coronavirus pandemic, it will not take place in 2020. Britten wrote his coronation opera, Gloriana.

7 Festival Committee, meeting minutes, 22 October 1949 (Britten Pears Arts Archive, MSC10/1 [Aldeburgh Festival Executive Committee minute book]).

8 The same could also be said of today’s audiences.

9 Trainer of the Aldeburgh festival choir. Margery had known her since at least 1944. She was the sister of Augustus John’s first wife, Ida.

10 Clark’s name is consistently misspelt by Margery and her friends.

11 Sally Schweitzer, private correspondence to the author, 24 March 2016.

12 Margery Spring Rice, letter to Ronald Garrett Jones, 24 March 1948.

13 Margery Spring Rice, letter to Ronald Garrett Jones, 25 April 1948.

14 Margery’s daughter-in-law, Ronald’s wife.

15 Charles Garrett Jones, letter to Margery Spring Rice, 17 August 1961.

16 Margery Spring Rice, letter to Stephen Robertson, 13 June 1963.

17 Charles Garrett Jones, letter to Margery Spring Rice, 20 May 1945.

18 At that time, there was a foot ferry across the Alde from the Iken side to Slaughden, the area at the southern end of the town of Aldeburgh, where the river makes a right-angle turn to run south for several miles to its mouth at Shingle Street.

19 She had stood unsuccessfully for the County Council, probably as an independent.

20 Margery Spring Rice, letter to Brenda & Anthony Gillingham, 8 February 1953.

21 The boots are now in the V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green, London.

22 Matthew Robertson, recollections of Iken, 2014.

23 Divorce was still less common at that time than it is now, and less socially acceptable. Some divorced women felt they had to leave the country and live abroad, for a time at least, to escape the scandal. Margery and Angela tried sharing Iken for a period, but they were both strong and self-willed women, and the arrangement came to a mutually agreed end.

24 Margery Spring Rice, letter to Brenda & Anthony Gillingham, 8 February 1953.

25 Both were delivered by Dr Robin Acheson, for many years a much-loved Aldeburgh GP.

26 Margery Spring Rice, letter to Brenda & Anthony Gillingham, 25 September 1952.

27 Even in 1950, the BBC had refused to allow a broadcast appeal on behalf of the Family Planning Association: Evans, Freedom to Choose, p. 162.

28 Lella S. Florence, Progress Report on Birth Control (London: Heinemann, 1956), p. 22–23.

29 The Times, 30 November 1955. The clinic visit was on 29 November. There was also an item on the BBC Woman’s Hour programme.

30 Margery Spring Rice, letter to Brenda & Anthony Gillingham, 25 September 1952.