1. Diversity in the Ancient Synagogue of Roman-Byzantine Palestine: Historical Implications

© Lee I. Levine, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0219.01

Synagogue remains from Roman-Byzantine Palestine far exceed those from the early Roman period. Of the more than one hundred sites with such remains, almost 90 percent date to Late Antiquity and display a remarkable diversity relating to almost every facet of the institution. Some structures were monumental and imposing (e.g., Capernaum), while others were modest and unassuming (e.g., Khirbet Shema‘); some had a basilical plan with the focus on the short wall at one end of the hall (e.g., Meiron), while others, having a broadhouse plan, were more compact, with the focus on the long wall (e.g., Susiya); some faced Jerusalem, as evidenced by their façades and main entrances (the Galilean type), and others were oriented in this direction via their apses, niches, or podiums, with their main entrances located at the opposite end of the hall (e.g., Bet Alpha); some were very ornate (e.g., Hammat Tiberias), while others were far more modestly decorated (e.g., Jericho). No matter how close to one another geographically or chronologically, no two synagogues were identical in their plan, size, or decoration.

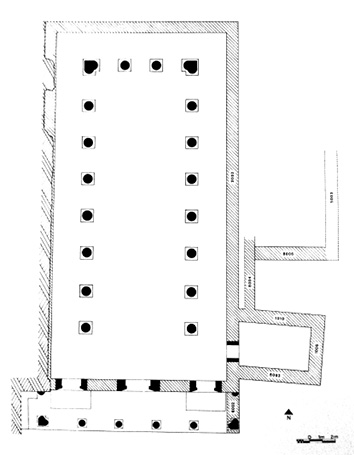

1.0. The Once-Regnant Architectural Theory

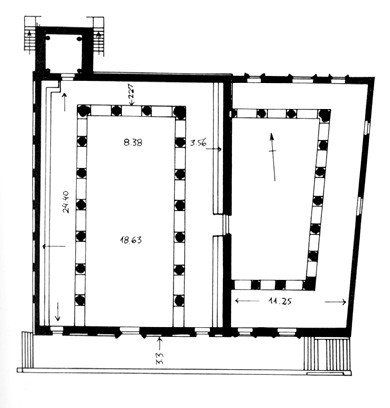

This recognition of widespread diversity among synagogues is at odds with the once widely accepted theory regarding the development of the Palestinian synagogue in Late Antiquity. For generations, archaeologists had accepted as axiomatic a twofold, and later threefold, typological classification of synagogue buildings based upon chronological and architectural considerations: the Galilean-type synagogue (e.g., Chorazim and Capernaum) was generally dated to the late second or early third centuries; the transitional, broadhouse, type (e.g., Eshtemoa and Khirbet Shema‘) to the late third and fourth centuries; and the later, basilical, type (e.g., Bet Alpha) to the fifth and sixth centuries (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Three-stage chronological development of Palestinian synagogues: Top: Capernaum. Lee I. Levine, ed., Ancient Synagogues Revealed, 13. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved. Middle: Eshtemoa. Lee I. Levine, ed., Ancient Synagogues Revealed, 120. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved. Bottom: Bet Alpha. Eleazar Lipa Sukenik, The Ancient Synagogue of Beth Alpha (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1931). Courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. © All rights reserved.

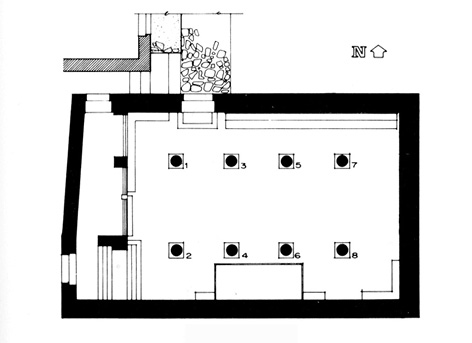

However, a plethora of archaeological discoveries since the last third of the twentieth century has seriously undermined this neat division that coupled typology with chronology. First and foremost, the findings of the Franciscan excavations at Capernaum redated what had been considered the classic ‘early’ synagogue from the second–third centuries to the late fourth or fifth century. Soon thereafter, excavation results from the synagogues at Khirbet Shema‘ and nearby Meiron dated both of these structures to the latter half of the third century, even though each typifies a very different architectural style according to the regnant theory (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Plans of two neighbouring third-century synagogues: Meiron (top); Khirbet Shema‘ (bottom). Courtesy of Eric Meyers. © All rights reserved.

Nahman Avigad’s decipherment of the previously enigmatic Nevoraya (or Nabratein) synagogue inscriptions indicates clearly that the building was constructed in the sixth century (564 CE), while the evidence from the Meiron synagogue attests to a late third- or early fourth-century date. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, other ‘Galilean’-type synagogues (Horvat Ammudim, Gush Halav, and Chorazim) were similarly dated to the late third or early fourth century. Finally, excavations conducted in the Golan date all the local synagogues (now numbering around thirty, Gamla excepted) to the fifth and sixth centuries.1

Thus, the earlier linear approach linking each type of building to a specific historical period can clearly be put to rest. Diversity in synagogue architecture indeed reigned throughout this era, as it did in other aspects of synagogue life. The social implications of this phenomenon will be addressed below.2

2.0. Orientation

Synagogues constructed throughout Late Antiquity were oriented almost universally toward Jerusalem. The relatively few entrances oriented eastward seem to preserve an early tradition (t. Meg. 3.22, ed. Lieberman, 360) derived from the memory of the Jerusalem Temple’s entrance gates. Presumably based on several scriptural references (1 Kgs 8.29–30; Isa. 56.7; Dan. 6.11), such an orientation was widely followed in Jewish communities: while Galilean synagogues in Roman-Byzantine Palestine faced south, those in the southern part of the country faced north, and those in the southern Judaean foothills (the Shephelah) faced northeast. There are also some interesting and enigmatic deviations from this norm; for example, all the Late Roman-Byzantine synagogues in the Golan faced either south or west, but none (except Gamla) was oriented to the southwest, i.e., directly toward Jerusalem.

|

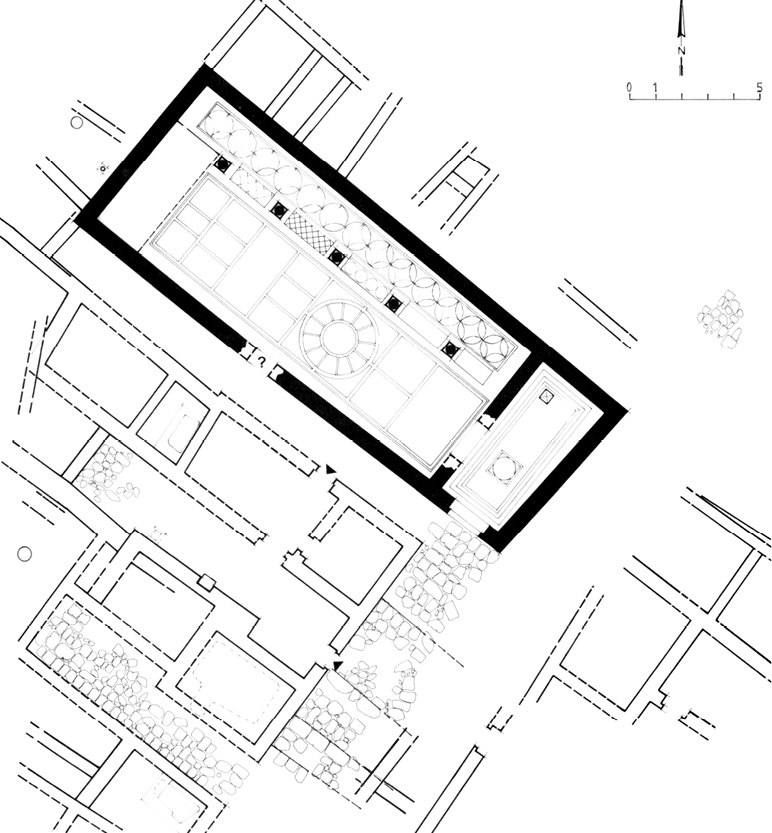

|

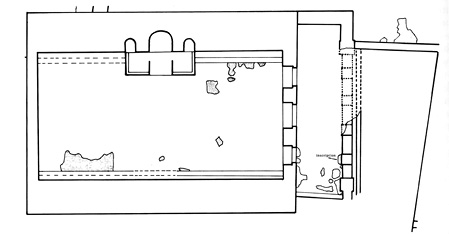

Fig. 3: Two synagogues facing northwest, away from Jerusalem: Left: Bet Shean A. Nehemiah Zori, ‘The Ancient Synagogue at Beth-Shean’, Eretz-Israel 8 (1967): 149–67 (155). Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved. Right: Sepphoris. Courtesy of Zeev Weiss. Drawing by Rachel Laureys. © All rights reserved.

A number of synagogues, such as the Horvat Sumaqa building on the Carmel range, which was built along a largely east-west axis, may have exhibited a somewhat ‘deviant‘ orientation, although one might claim that it may have been intended to face southeast, toward Jerusalem. The Lower Galilean synagogue of Japhia also lies on an east-west axis, and its excavators assume that it was probably oriented to the east. Moreover, the Sepphoris and Bet Shean synagogues, the latter located just north of the Byzantine city wall (Fig. 3), had a northwesterly orientation, decidedly away from Jerusalem. Even if one were to assume that the Bet Shean building was Samaritan (as has been suggested by some), we would encounter the same problem, for Samaritans built their synagogues oriented toward Mount Gerizim, which would have dictated a southern orientation. At present, we have no way of determining why these particular synagogues faced northwest. Such an explanation, in fact, may not have been based on halakhic or ideological considerations, but rather on much more mundane ones, such as ignorance (however unlikely), indifference, convenience (topographical or otherwise), or the need to conform to an as-yet-unidentified local factor. Nevertheless, despite these instances of diversity, the overwhelming majority of synagogues discovered in Roman-Byzantine Palestine display the accepted practice of orientation toward Jerusalem.

Such an orientation is clearly an expression of Jewish particularism. The façades of sacred buildings in antiquity, be they pagan temples or Christian churches, regularly faced east, toward the rising sun, as did the Desert Tabernacle and the two Jerusalem Temples. In the Second Temple period, however, such obvious parallels with pagan worship became problematic, and a ceremony was reportedly introduced on the festival of Sukkot to underscore the difference between pagan and Jewish orientation; as a result, it is claimed that Jews demonstratively abandoned this practice and faced west inside the Temple precincts (m. Suk. 5.4).

Diversity is clearly evident in many other architectural components of the Roman-Byzantine synagogue, including atriums, water installations, entrances, columns, benches, partitions, balconies, bimot, tables, platforms, special seats, as well as the Torah shrine, eternal light, and menorah.

3.0. Art

3.1. The Local Factor

Diversity is likewise a distinct feature of ancient synagogue art. For instance, despite geographical and chronological propinquity, Capernaum is worlds apart from Hammat Tiberias, as Rehov is from Bet Alpha and as Jericho is from Naʿaran.

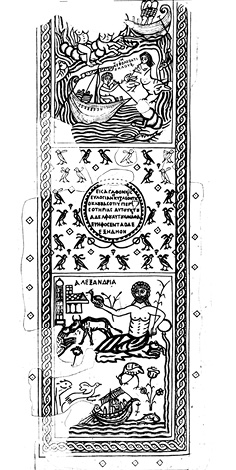

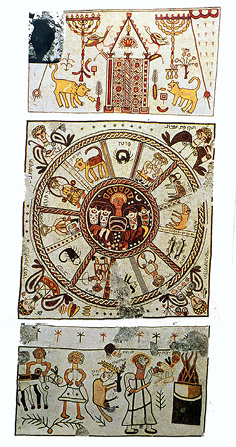

The cluster of five synagogue buildings that functioned simultaneously in sixth-century Bet Shean and its environs is a striking case in point, as they differ from each other in the languages used, building plans, and architecture. These include Bet Shean A, just north of the city wall, Bet Shean B near the southwestern city gate, Bet Alpha to the west, Maʿoz Hayyim to the east, and Rehov to the south. The artistic representations in these synagogues are about as disparate as one could imagine, ranging from the strictly conservative to the markedly liberal. At the former end of the spectrum stands the Rehov building, with its geometric mosaics. However, the mosaic floor in the prayer room of the Bet Shean B synagogue features inhabited scrolls and figural representations of animals alongside an elaborate floral motif. The mosaic floor in a large adjacent room containing panels with scenes from Homer’s Odyssey is most unusual, depicting the partially clad god of the Nile together with Nilotic motifs (a series of animals and fish) and a symbolic representation of Alexandria with its customary Nilometer.

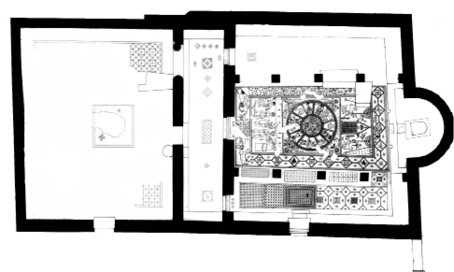

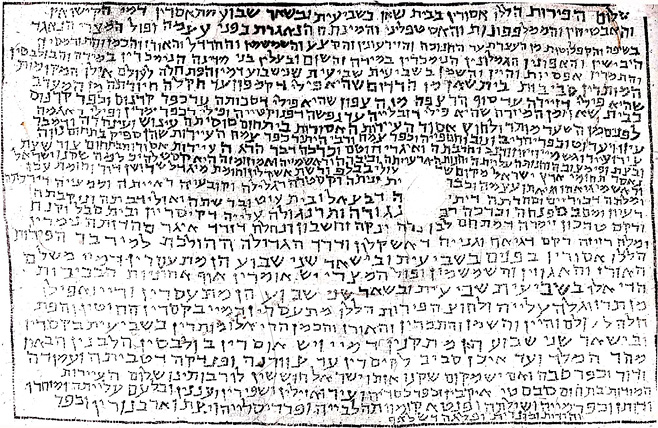

Fig. 4: Mosaic floors from three sixth-century synagogues in the Bet Shean area. Top: halakhic inscription from Rehov. Lee I. Levine, Ancient Synagogues Revealed, 147. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved. Bottom left: Nilotic themes from Bet Shean B. Nehemiah Zori, ‘The House of Kyrios Leontis at Beth Shean’, Israel Exploration Journal 16 (1966): 123–34. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved. Bottom right: zodiac from Bet Alpha. Nahman Avigad, ‘Beth Alpha’, in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. by Ephraim Stern, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1993), I, 190–92. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved.

No-less-extensive artistic representations were found in the Bet Alpha synagogue, which incorporates Jewish and pagan motifs that are expressed through Jewish symbols, the zodiac signs, and the Aqedah scene. Although the same artisans, Marianos and his son Hanina, laid the mosaic floors in both the Bet Alpha and Bet Shean A synagogues, the style and content at each site are strikingly different. This is a clear example of two neighbouring communities choosing contrasting floor designs (possibly from pattern books or oral reports then in circulation) (Fig. 4).

Clearly, then, the floors of these Bet Shean synagogues, ranging from strictly aniconic patterns to elaborate representations of Jewish and non-Jewish figural motifs, allow us to safely posit that the local context of the synagogue in Late Antiquity is the key to understanding this diversity in Jewish art. However, while this factor is the most crucial component, several additional considerations had an impact on the choices made by the local communities.

3.2. The Regional Factor

3.2.1. The Galilee

While diversity is well attested in all regions of Palestine, Galilean regionalism is particularly evident when distinguishing between characteristics of the Upper and Lower Galilee. The Upper Galilee is more mountainous, has more rainfall and poorer roads, and is therefore dotted with villages and small towns, but no cities. As a result, the synagogues in this region, with but a few exceptions, adopted a culturally more conservative and insular bent expressed by a more limited use of Greek, fewer figural representations, and only a smattering of Jewish symbols. The Upper Galilee produced many of the so-called Galilean-type synagogues, which are characterized by monumental entranceways oriented toward Jerusalem, large hewn stones, flagstone floors, stone benches along two or three sides of the main hall, several rows of large columns, and stone carvings appearing primarily on the buildings’ exterior (door and window areas, capitals, lintels, doorposts, friezes, pilasters, gables, and arches) and to a lesser extent on their interior (Fig. 5). However, for all the similarities between these synagogues, they also displayed many differences. Gideon Foerster has summed up his study of the Galilean-type buildings as follows: “Studying the art and architecture of the Galilean synagogues leads one to conclude that these synagogues are a local, original, and eclectic Jewish creation.”3

Fig. 5: The Capernaum synagogue. Top: Façade reconstruction. Heinrich Kohl and Carl Watzinger, Antike Synagogen in Galilaea (Leipzig: Heinrichs, 1916). Public Domain. Bottom: aerial view. Courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. © All rights reserved.

In contrast, the Jewish communities in the Lower Galilee present a very different cultural panorama. Flanked by the two urban centres, Sepphoris on the west and Tiberias on the east, the region’s more navigable terrain contained better roads and, consequently, allowed for closer ties with the neighbouring non-Jewish cities and regions. Thus, the prominence of Greek across the Lower Galilee—from the synagogues in Tiberias (where ten of the eleven dedicatory inscriptions are in Greek) and Sepphoris (where thirteen of twenty-four inscriptions are in Greek), and further west to the Bet Sheʿarim necropolis (where over 80 percent of approximately three-hundred inscriptions are in Greek)—reflects a cosmopolitan dimension very different from the more provincial Upper Galilee (Fig. 6). Rare is the site that does not have some sort of artistic representation, be it the zodiac, a cluster of Jewish symbols (Tiberias and Sepphoris), biblical scenes (Sepphoris, Khirbet Wadi Hamam, and Huqoq), or what might be animal representations of the tribes of Israel (Japhia). Thus, the varied topographical, geographical, and climatic elements in the Upper and Lower Galilee created dramatically different demographic, cultural, and artistic milieux.

Fig. 6: Eight Greek dedicatory inscriptions on the mosaic floor of the Hammat Tiberias synagogue. Moshe Dothan, Hammath Tiberias (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1983), plates 10/11. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved.

3.2.2. The Golan

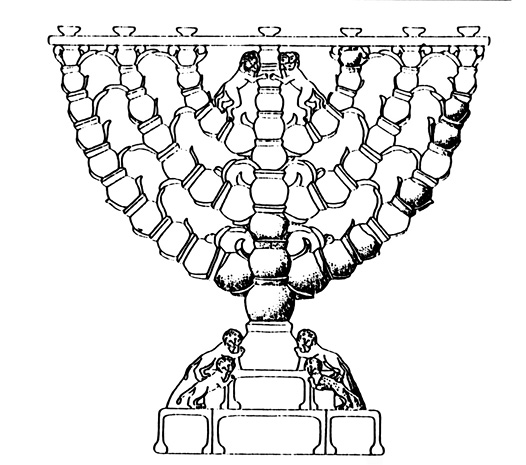

About thirty known Golan-type synagogues from Late Antiquity are in many respects similar to the Galilean-type buildings, as both utilized much the same architectural features and building techniques. Nevertheless, the differences between them are not inconsequential.4 The Golan-type buildings were constructed of local basalt (unlike the limestone used in a number of Galilean-type synagogues), and all—with the exception of e-Dikke—had a single entrance oriented in different directions. In contrast to the Galilean-type building, in which its usual three entrances almost invariably faced south, the interior of the Golan-type synagogues was oriented either to the south or west, as noted above. Column pedestals and heart-shaped corner columns, ubiquitous in the Galilee, are absent from the Golan. The artistic differences between the synagogues of the Upper Galilee (Capernaum and Chorazim aside) and the Golan are also quite blatant, the latter displaying a wider range of figural art, including animal, human, and mythological representations. Moreover, the widespread use of religious symbols in the Golan, first and foremost the menorah (often accompanied by the shofar, lulav, ethrog, and incense shovel), stands in striking contrast to their limited appearance in the Upper Galilee (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: Menorah carved on a decorated capital from the ʿEn Neshut synagogue. Zvi U. Ma‘oz, ‘‘En Neshut’, in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. by Ephraim Stern, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1993), II, 412–14. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved.

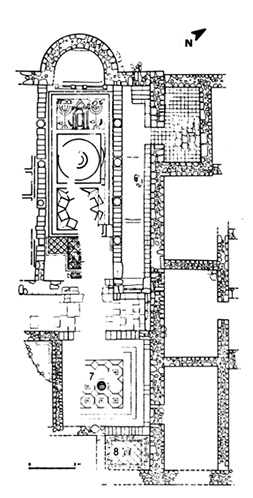

3.2.3. The Southern Judaean Foothills

Four synagogues discovered in the twentieth century—Eshtemoa, Susiya, Maʿon, and Anim—can be characterized as a distinct architectural group on the basis of their entrances facing east, the absence of columns, and the presence of a bima, niche, or combination thereof. Despite this unusual commonality, these buildings also exhibit a large degree of diversity—two are broadhouse-type buildings (Eshtemoa and Susiya) and two are basilica-type structures (Anim and Maʿon). Interestingly, while this eastward orientation was scrupulously followed in the southern Judaean foothills, it was generally ignored elsewhere in Palestine.5

The relative prominence of priests in the southern Judaean synagogues is likewise noteworthy. Priests are mentioned in dedicatory inscriptions at both Eshtemoa and Susiya; while these numbers are not large, they become more significant in light of the fact that priests are noted in inscriptions from only two other synagogues elsewhere in Palestine. The prominence of the menorah in these synagogues is also notable. Three of the four southern Judaean synagogue buildings (Eshtemoa, Susiya, and Maʿon) had three-dimensional menorot, each made of marble imported from Asia Minor, while those in Eshtemoa and Maʿon reached the height of a human being and may have been used, inter alia, for illuminating the sanctuary (Fig. 8). Three-dimensional menorot were found at only four other sites throughout Palestine—Horvat Rimmon, En Gedi, Hammat Tiberias, and possibly a fragment of one at Merot.6

Fig. 8: Reconstruction of a marble menorah from the Ma‘on synagogue. N. Slouschz, ‘Concerning the Excavations and/or the Synagogue at Hamat–Tiberias’, Journal of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society 1 (1921): 5–36 (32). Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved.

The above features distinguishing the communities of southern Judaea may indicate that the Jews there, being quite distant from the centres of contemporary Jewish settlement in the north, clung to local traditions, revealing a priestly orientation associated with the memory of the Jerusalem Temple.

The synagogues south of the Upper Galilee and Golan tended to be quite ornate, owing primarily to the ubiquitous use of mosaic floors throughout the Galilee and Bet Shean areas, the Jordan Valley, the coastal region, and even parts of Judaea. The earliest traces of mosaic floors in a synagogue, from relatively simple geometric patterns to more sophisticated motifs and figural scenes, date to late antiquity, but figural representations became widespread only from the fourth century on. The archaeological finds reflect this development and neatly dovetail with one rabbinic tradition: “In the days of Rabbi Abun [fourth century], they began depicting [figural images] on mosaic floors, and he did not object” (y. Avod. Zar. 3.3, 42d, together with the Genizah fragment of this tradition published by Jacob N. Epstein, ‘Yerushalmi Fragments’, Tarbiz 3 [1932]: 15–26, [p. 20] [Hebrew]).

Fig. 9: Part of the mosaic floor in the Jericho synagogue. Photo by Gilead Peli. © All rights reserved.

Beginning with the late fourth-century synagogue at Hammat Tiberias, most mosaic floors were divided into a unique three-panel arrangement, although some synagogues featured an overall carpet with no internal division. The mosaic floor at Jericho, for example, depicts geometric and floral designs as well as a stylized Torah chest in the centre (Fig. 9), while the En Gedi mosaic displays four birds in its centre surrounded by a carpet of geometric designs. The floors of three synagogues—Gaza, nearby Maʿon (Judaea), and Bet Shean B—are decorated with carpets featuring inhabited scroll patterns and vine tendrils issuing from an amphora creating a series of medallions. The latter contained, inter alia, baskets of bread and fruit, cornucopiae, grape clusters, flowers, animals, and birds, as well as a row in the centre of the mosaic depicting a variety of bowls, vases, baskets with fruit, and cages with birds.7

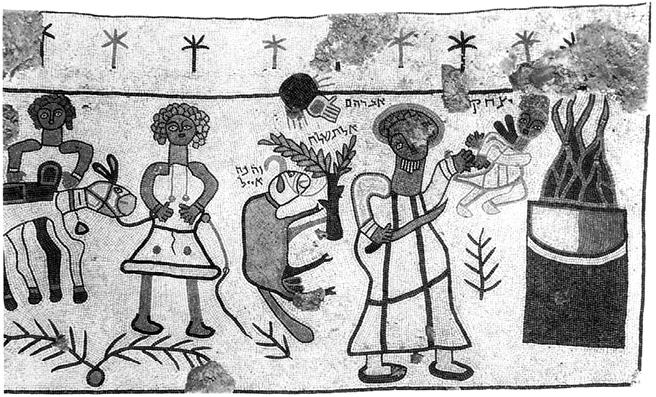

Fig. 10: The Aqedah (Binding of Isaac) scene in the Bet Alpha synagogue. Eleazar Lipa Sukenik, The Ancient Synagogue of Beth Alpha (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1931). Courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. © All rights reserved.

Fig. 11: Figure of David from the Gaza synagogue. Courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. © All rights reserved.

Fig. 12: Figure of Samson from the Huqoq synagogue. Courtesy of Jodi Magness. Photograph by Jim Haberman. © All rights reserved.

The depiction of biblical scenes on the mosaic floors of Palestinian synagogues is quite striking. Although these are less common than the clusters of Jewish symbols, they appear, nonetheless, in disparate regions of the country and include the Aqedah (Bet Alpha, Sepphoris; Fig. 10), David (Gaza and probably Merot; Fig. 11), Daniel (Susiya, Naʿaran, and perhaps En Semsem in the Golan), the crossing of the Red Sea (Khirbet Wadi Hamam, Huqoq), Aaron and the Tabernacle-Temple appurtenances and offerings (Sepphoris), Samson (Khirbet Wadi Hamam, Huqoq; Fig. 12), and possibly symbols of the tribes (Japhia).8

4.0. Languages

The use of Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic in a variety of combinations is revealing with regard to the cultural orientation of a given community. Inscriptions were written in the languages spoken by the Jews in a given area; Greek and Aramaic generally predominated in Palestine, while Hebrew was a less significant component that seems to have occupied a central role at several sites in the Upper Galilee and southern Judaea. Broadly speaking, Hebrew and Aramaic were used in areas having a dense Jewish population, particularly in the rural areas of Palestine, while Greek was more dominant on the coast and in the big cities. Synagogue inscriptions are invariably short, usually no more than ten to twenty words. While some five-hundred inscriptions indeed relate to the ancient synagogue and its officials, some 60 percent of them come from the Diaspora.

Fig. 13: Inscription on a mosaic floor in the En Gedi synagogue. Lee I. Levine, Ancient Synagogues Revealed, 141. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved.

Inscriptions served several purposes. At times they were used as legends (tituli) for identifying specific artistic depictions, such as those in Hebrew that invariably accompany the representations of the zodiac signs and seasons (e.g., Hammat Tiberias, Bet Alpha, Sepphoris, and Naʿaran) or biblical figures and scenes. Moreover, the Jericho synagogue inscription contains a biblical phrase (שלום על ישראל—Ps. 125.5) and the Merot synagogue inscription quotes a complete verse (Deut. 28.6). Inscriptions may also have been instrumental in fostering memories of the past and hopes for the future. This is particularly true of the lists of the twenty-four priestly courses that have been found in both Palestine and the Diaspora. Their presence seems to have been intended to maintain and bolster national-religious memories and aspirations.9

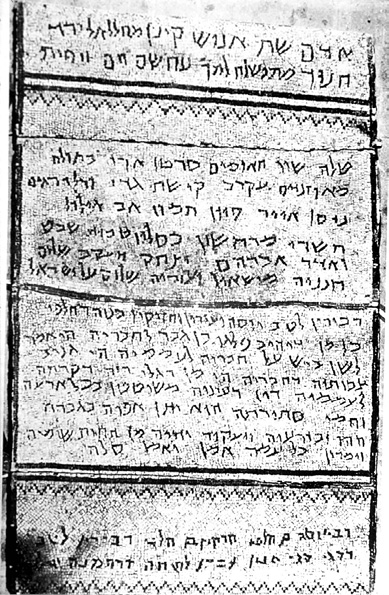

One inscription from En Gedi lists in its opening paragraph the Fathers of the World according to 1 Chron. 1, the names of the zodiac signs, the months of the year, the three biblical patriarchs, the three friends of Daniel, and three donors to the synagogue. The main section of the inscription instructs the members of the community on how to relate to each other as well as to the outside world, particularly with regard to the “secret of the community,” warning them of the dire consequences of not acting according to its guidelines (Fig. 13).10

Most synagogue inscriptions are dedicatory in nature; a benefactor would commemorate his or her gift to the synagogue, thereby gaining prestige and fulfilling a religious vow to serve the common good.11 Occasionally, the names of the artisans, such as Marianos, Hanina, and Yosi Halevi, are recorded in inscriptions; the first two, as noted above, laid the mosaic floors of the synagogues at Bet Alpha and Bet Shean, while the third “made the lintel” in the synagogues at Alma and Barʿam in the Upper Galilee.12

Inscriptions mentioning the date of a building’s construction or renovation are historically invaluable, though unfortunately rare. The various dates invoked might include the reign of an emperor (Bet Alpha), a municipal era (Gaza, Ashkelon), the creation of the world (Susiya, Bet Alpha), sabbatical years (Susiya), or the Jerusalem Temple’s destruction (Nabratein). The unique halakhic inscription from Rehov, south of Bet Shean, features laws relating to the sabbatical year, listing the areas in Palestine to be included in its observance and the fruits and vegetables prohibited to Jews during that year.13 Another inscription, from the synagogue in Jericho, acknowledges donations by its congregants in poetic language reminiscent of later Jewish prayers that offer a blessing to an entire congregation.14

5.0. The Liturgical Evidence

The liturgy adopted by a given synagogue was likewise a local decision. The implementation of the Palestinian triennial Torah-reading cycle, for example, varied from one locale to the next; sources from Late Antiquity indicate that these readings might have been divided into 141, 154, 155, 167, and possibly 175 portions over a three- to three-and-a-half-year cycle.15 The Babylonian Torah-reading practice, concluded in just one year, is evidenced in Palestine as well. This diversity is noted in the Differences in Customs, a composition that compares religious practices in Palestine and Babylonia of Late Antiquity and perhaps the Geonic period.16

The readings from the Prophets (haftarot) that accompanied the Torah recitation also varied from place to place, some synagogues requiring twenty-one verses to be read (three for each of the seven portions read from the Torah; b. Meg. 23a). The Talmud Yerushalmi explains that in places where the Targum was also recited only three verses of the Prophets were to be read; otherwise, twenty-one verses were required (y. Meg. 4.3, 75a). Tractate Soferim (13.15, ed. Higger, 250–51) mentions at least four different practices in this regard: When are these rules [i.e., reading twenty-one verses] applicable? When there is no translation [targum] or homily. But if there is a translator or a preacher, then the maftir [one who reads the haftarah] reads three, five, or seven verses in the Prophets, and this is sufficient.” Moreover, given its lesser sanctity, the haftarah recitation was a much more flexible component than the Torah reading; verses on assorted subjects could be drawn from different sections of a book, or even from several different books, of the Bible (m. Meg. 4.4; b. Meg. 24a). Here, too, the local congregation (or its representatives) decided on their preferred liturgical practice.

The same probably held true for other components of the liturgy. Although the evidence for Late Antiquity is negligible, synagogue prayer was most likely in a fluid state; there is no way of determining the parameters of fixed prayer at this time since the earliest prayer book (siddur) dates from the ninth or tenth century. Piyyut (liturgical poetry) also seems to have made its first appearance in the synagogue of Late Antiquity, yet we have no idea how many congregations might have incorporated these poetic recitations into their service, how they were chosen, or how frequently they were recited. The sophisticated Hebrew often employed in piyyut may well have been a deterrent to congregations comprising primarily Aramaic or Greek speakers.

6.0. Communal Infrastructure

In attempting to understand the synagogue of Late Antiquity, it is of paramount importance to clarify who made the decisions regarding its operation. As noted, the literary, epigraphic, and artistic evidence points to the local community as the ultimate arbitrator of the synagogue’s physical and programmatic aspects; there is no evidence of any other institution, group, or office that might have been so authorized. Since diversity among synagogues was ubiquitous, it was the local community’s prerogative to decide what kind of building would be erected and where, and how it would be decorated, maintained, and administered.17

The synagogue functioned as the local Jewish communal institution par excellence. It served a range of purposes that might include meeting place, educational, social, and charity-oriented activities, communal meals, a local court, and a place for lodging. The tendency of some (many?) second-century Jews to refer to the synagogue as a bet ʿam (‘house of [the] people’)—to the chagrin of certain rabbis (b. Shabb. 32a)—clearly indicates the importance of this dimension of the institution. Indeed, the synagogue belonged to the community, and the Mishnah (m. Ned. 5.5) clearly associates the synagogue and some of its features with a communal context: “And what things belong to the (entire) town itself? For example, the plaza, the bath, the synagogue, the Torah chest, and [holy] books”. Synagogue officials were thus beholden to their respective communities and not to any single outside authority.

Local loyalties often ran high, particularly in matters relating to the synagogue building or its functionaries, and such issues might have become a source of rivalry among neighbouring communities: “[Regarding] a small town in Israel, they [the townspeople] built for themselves a synagogue and academy and hired a sage and instructors for their children. When a nearby town saw [this], it [also] built a synagogue and academy, and likewise hired teachers for their children” (Seder Eliyahu Rabbah 11, ed. Friedmann, 54–55).

However, there were also some synagogues, such as the first-century Theodotos synagogue in Jerusalem, that operated under the patronage of a wealthy family. Indeed, a number of synagogues in Late Antiquity were led by a coterie of wealthy and acculturated members who shouldered the major financial burden of their synagogues, as was the case at Hammat Tiberias.18

The local community was responsible for the synagogue’s maintenance, including salaries that were at times covered by wealthy laymen or officials, such as the archisynagogue, presbyter, or archon. Prayer leaders, Torah readers, liturgical poets, and preachers may have received remuneration for their services, but of this we cannot be certain. Other functionaries—the teacher (sofer), hazzan, shamash, and meturgeman—received compensation, however minimal.19

Thus, local communities exercised control over the hiring and firing of their synagogue functionaries, and in one instance the synagogue community of Tarbanat (in the Jezreel Valley) dismissed one Rabbi Simeon who was unwilling to comply with its request. The villagers appealed to him:

[The villagers said:] “Pause between your words [when either reading the Torah or rendering the Targum], so that we may relate this to our children.” He [Rabbi Simeon] went and asked [the advice of] Rabbi Hanina, who said to him: “Even if they [threaten to—L. L.] cut off your head, do not listen to them.” And he [Rabbi Simeon] did not take heed [of the congregants’ request], and they dismissed him from his position as sofer. (y. Meg. 4.5, 75b)

A community’s search for competent personnel was not uncommon. Around the turn of the third century, the residents of Simonias (in the Galilee) solicited the help of Rabbi Judah I in finding someone who could preach, judge, serve as a hazzan and teach children, and “fulfill all our needs” (y. Yevam. 12.6, 13a; Gen. Rab. 81.2, ed. Theodor and Albeck, 969–72). He recommended one Levi bar Sisi, who was interviewed for the position, but apparently made an unfavorable first impression. A similar request was made of Rabbi Simeon ben Laqish in the mid-third century when visiting Bostra in Transjordan (y. Shev. 6.1, 36d; Deut. Rab., Vaʾethanan, ed. Lieberman, 60).

The construction or repair of a synagogue building was also a communal responsibility and a binding obligation: “Members of a town [can] force one another to build a synagogue for themselves and to purchase a Torah scroll and [books of the] Prophets” (t. B. Metzia 11.23, ed. Zuckermandel, 125).

Several epigraphic sources from Byzantine Palestine highlight the centrality of the synagogue’s communal dimension. Note, for example, the following inscription from Jericho:

May they be remembered for good. May their memory be for good, the entire holy congregation, the old and the young, whom the King of the Universe has helped, for they have contributed to and made this mosaic. May He who knows their names, [as well as] their children and members of their households, write them in the Book of Life together with all the righteous. All the people of Israel are brethren. Peace. Amen.20

Synagogue inscriptions at times focus on matters of prime concern to the entire congregation. The monumental inscription at the entrance to the Rehov synagogue’s main hall reflects this community’s halakhic orientation,21 while an Aramaic inscription located in the western aisle of the En Gedi synagogue addresses a number of important local concerns:

He who causes dissension within the community, or speaks slanderously about his friend to the gentiles, or steals something from his friend, or reveals the secret of the community to the gentiles—He, whose eyes observe the entire world and who sees hidden things, will turn His face against this fellow and his offspring and will uproot them from under the heavens. And all the people said: “Amen, Amen, Selah.”22

Communal responsibility might also extend to the synagogue’s liturgical components, as is vividly borne out by an account regarding a Caesarean synagogue whose members decided to recite a central prayer of the Jewish liturgy, the Shema, in Greek and not in Hebrew. Clearly, the use of Greek met local needs, but what makes this account especially fascinating, and the reason it appears in a rabbinic source at all, is the fact that two sages reacted to this phenomenon in totally different ways—one condemning this practice, the other supporting it:

Rabbi Levi bar Hiyta came to Caesarea. He heard voices reciting the Shema in Greek [and] wished to stop them. Rabbi Yosi heard [of this] and became angry [at Rabbi Levi’s reaction]. He said, “Thus I would say: ‘Whoever does not know how to read it [the Shema] in Hebrew should not recite it at all? Rather, he can fulfill the commandment in any language he knows’” (y. Sotah 7.1, 21b).

It is therefore clear that the opinions of these two sages (or any others, for that matter) were never solicited by the congregation beforehand and, once expressed, probably played no role whatsoever in the synagogue’s policy. Besides the specific case of the Shema, there can be little question that synagogues such as this one—which would include virtually all Roman Diaspora congregations and not a few in Palestine—did, in fact, render their sermons, expound the Scriptures, and pray in Greek.23

Fig. 14: Zodiac motif and figure of Helios on the mosaic floor of the fourth-century Hammat Tiberias synagogue. Moshe Dothan, Hammath Tiberias (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1983), plates 10/11. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society. © All rights reserved.

7.0. Epilogue

Archaeological finds (architecture, art, and epigraphy) have alerted us to the resilience and remarkable self-confidence of Jewish communities in antiquity. The very existence of so many synagogues in Palestine and the Diaspora—often in prominent locations, of monumental size, and exhibiting cultural vibrancy—refutes the once normative claim that this was a period characterized only (or primarily) by persecution, discrimination, and suffering. The apparent economic, social, and political stability of these communities well into the Byzantine era has revealed a far more complex reality than heretofore imagined and, along with it, a far greater range of identities fashioned by Jews throughout the empire (Fig. 14).

When viewed in this perspective, Late Antiquity thus emerges as an era in which Jews were actively engaged in a diverse and multifaceted range of cultural and religious realms, often in tandem with the surrounding culture. If the term ‘Late Antiquity’ points to processes of renewal, vitality, and creativity in Byzantine-Christian society, as suggested by Peter Brown,24 then it is indeed not difficult to identify similar phenomena within the contemporaneous Jewish sphere as well.25

Bibliography

Amir, Roni, ‘Style as a Chronological Indicator: On the Relative Dating of the Golan Synagogues’, in Jews in Byzantium: Dialectics of Minority and Majority Cultures, ed. by Robert Bonfil, Oded Irshai, Guy G. Stroumsa, and Rina Talgam (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 339–71, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004203556.i-1010.42.

Avigad, Nahman, ‘Beth Alpha’, in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. by Ephraim Stern, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1993), I, 190–92.

Brown, Peter R.L., The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150–750 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1971).

Brown, Peter R.L. et al., ‘The World of Late Antiquity Revisited’, Symbolae Osloenses 72 (1997): 5–90.

Collins, John J., and Gregory E. Sterling, eds., Hellenism in the Land of Israel (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2001).

Dothan, Moshe, Hammath Tiberias (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1983).

Epstein, Jacob N., ‘Yerushalmi Fragments’, Tarbiz 3 (1932): 237–48.

Foerster, Gideon, ‘Synagogue Inscriptions and Their Relation to Liturgical Versions’, Cathedra 19 (1981): 12–40. [Hebrew]

———, ‘The Art and Architecture of the Synagogue in Its Late Roman Setting’, in The Synagogue in Late Antiquity, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Philadelphia: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1987), 139–46.

Friedmann, Meir, ed., Seder Eliyahu Rabbah and Seder Eliyahu Zuta (Warsaw: Achiasaf, 1904).

Hachlili, Rachel, Ancient Mosaic Pavements: Themes, Issues, and Trends: Selected Studies (Leiden: Brill, 2009), http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004167544.i-420.

Higger, Michael, ed., Tractate Soferim (New York: Debe Rabbanan, 1937).

Horst, Pieter Willem van der, Jews and Christians in Their Graeco-Roman Context: Selected Essays on Early Judaism, Samaritanism, Hellenism, and Christianity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006).

Kohl, Heinrich, and Watzinger, Carl, Antike Synagogen in Galilaea (Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1916).

Levine, Lee I., ‘The Inscription in the ‘En-Gedi Synagogue’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 140–45.

———, Judaism and Hellenism in Antiquity: Conflict or Confluence? (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998).

———, The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years, 2nd ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005).

———, Visual Judaism in Late Antiquity: Historical Contexts of Jewish Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012).

———, ‘Palaestina Secunda: The Setting for Jewish Resilience and Creativity in Late Antiquity’, in Strength to Strength: Essays in Honor of Shaye J. D. Cohen, ed. by Michael L. Satlow (Providence, RI: Brown University, 2018), 511–35.

Lieberman, Saul, ed., The Tosefta, 5 vols. (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1955–1988). [Hebrew]

———, Midrash Debarim Rabbah (Jerusalem: Wahrmann Books, 1974). [Hebrew]

Magness, Jodi, ‘The En-Gedi Synagogue Inscription Reconsidered’, Eretz-Israel 31 (2015): 123*–31*.

Ma‘oz, Zvi U., ‘The Art and Architecture of the Synagogues of the Golan’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 98–115.

———, ‘‘En Neshut’, in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. by Ephraim Stern, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1993), II, 412–14.

———, ‘Golan’, in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. by Ephraim Stern, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1993), II, 539–45.

Margalioth, Mordechai, ed., Differences in Customs between the People of the East and the People of Eretz-Israel (Jerusalem: Mass, 1938). [Hebrew]

Meir, Dafna, and Eran Meir, Ancient Synagogues of the Golan (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 2015). [Hebrew]

Naveh, Joseph, On Stone and Mosaic: The Aramaic and Hebrew Inscriptions from Ancient Synagogues (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1978). [Hebrew]

———, ‘Ancient Synagogue Inscriptions’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 133–39.

Rajak, Tessa, ‘Jews as Benefactors’, in Studies on the Jewish Diaspora in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, ed. by Benjamin Isaac and Aharon Oppenheimer (Teʿuda 12; Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing, 1996), 17–38.

Roth-Gerson, Leah, The Greek Inscriptions from the Synagogues in Eretz-Israel (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1987). [Hebrew]

Slouschz, N., ‘Concerning the Excavations and/or the Synagogue at Hamat–Tiberias’, Journal of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society 1 (1921): 5–36.

Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa, The Ancient Synagogue of Beth Alpha: An Account of the Excavations Conducted on Behalf of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem (Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Press, 1931).

Sussmann, Jacob, ‘The Inscription in the Synagogue at Rehob’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 146–53.

Theodor, J. and Ch. Albeck, Midrash Bereshit Rabba: Critical Edition with Notes and Commentary, 3 vols. (Jerusalem: Wahrmann Books, 1965). [Hebrew]

Vitto, Fanny, ‘Rehob’, in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. by Ephraim Stern, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1993), IV, 1272–74.

Werlin, Steven H., Ancient Synagogues of Southern Palestine, 300–800 C.E.: Living on the Edge (Leiden: Brill, 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004298408.

Zori, Nehemiah, ‘The House of Kyrios Leontis at Beth Shean’, Israel Exploration Journal 16 (1966): 123–34.

———, ‘The Ancient Synagogue at Beth-Shean’, Eretz-Israel 8 (1967): 149–67.

Zuckermandel, Moses Samuel, ed., Tosephta (Trier, 1882). [Hebrew]

1 Zvi U. Ma‘oz, ‘Golan’, in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. by Ephraim Stern, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1993), II, 539–45; Zvi U. Ma‘oz, ‘The Art and Architecture of the Synagogues of the Golan’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 98–115; Roni Amir, ‘Style as a Chronological Indicator: On the Relative Dating of the Golan Synagogues’, in Jews in Byzantium, ed. by Robert Bonfil (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 339–71; Dafna Meir and Eran Meir, Ancient Synagogues of the Golan (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 2015), 27–29 (Hebrew).

2 Lee I. Levine, The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years, 2nd ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 319–24; idem, Visual Judaism in Late Antiquity: Historical Contexts of Jewish Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 394–402.

3 Gideon Foerster, ‘The Art and Architecture of the Synagogue in Its Late Roman Setting’, in The Synagogue in Late Antiquity, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Philadelphia: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1987), 139–46 (144).

4 Ma‘oz, ‘Art and Architecture of the Synagogues of the Golan’, 98–115; Meir and Meir, Ancient Synagogues; Amir, ‘Style as a Chronological Indicator’, 339–71.

5 Steven H. Werlin, Ancient Synagogues of Southern Palestine, 300–800 C.E.: Living on the Edge (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 135–221.

6 Ibid., 291–319.

7 Rachel Hachlili, Ancient Mosaic Pavements: Themes, Issues, and Trends—Selected Studies (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 111–47.

8 Levine, Visual Judaism, 348–54; and below.

9 Levine, Ancient Synagogue, 239, 520–21.

10 Lee I. Levine, ‘The Inscription in the ‘En-Gedi Synagogue’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 140–45; see also Jodi Magness, ‘The En-Gedi Synagogue Inscription Reconsidered’, in Eretz-Israel 31 (2015): 123*–31*. A line-by-line translation of the inscription reads as follows: (1) Adam, Seth, Enosh, Kenan, Mahalalel, Jared, (2) Enoch, Methuselah, Lamech, Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth (3) Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, (4) Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces. (5) Nisan, Iyar, Sivan, Tammuz, Av, Elul, (6) Tishrei, Marheshvan, Kislev, Tevet, Shevat, (7) and Adar. Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Peace. (8) Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah. Peace unto Israel. (9) May they be remembered for good: Yose and Ezron and Hiziqiyu the sons of Hilfi. (10) He who causes dissension within the community, or (11) speaks slanderously about his friend to the gentiles, or steals (12) something from his friend, or reveals the secret of the community (13) to the gentiles—He, whose eyes observe the entire world (14) and who sees hidden things, will turn His face against that (15) fellow and his offspring and will uproot them from under the heavens. (16) And all the people said: “Amen, Amen, Selah.” (17) Rabbi Yose the son of Hilfi, Hiziqiyu the son of Hilfi, may they be remembered for good, (18) for they did a great deal in the name of the Merciful, Peace.

11 Tessa Rajak, ‘Jews as Benefactors’, in Studies on the Jewish Diaspora in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, ed. by Benjamin Isaac and Aharon Oppenheimer (Teʿuda 12; Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing, 1996), 17–38.

12 Joseph Naveh, On Stone and Mosaic: The Aramaic and Hebrew Inscriptions from Ancient Synagogues (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Carta, 1978), nos. 1, 3, and 4 (Hebrew); Leah Roth-Gerson, The Greek Inscriptions from the Synagogues in Eretz-Israel (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1987), nos. 4 and 5 (Bet Alpha and Bet Shean) (Hebrew); Joseph Naveh, ‘Ancient Synagogue Inscriptions’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 133–39 (137) (Alma and Barʿam).

13 Jacob Sussmann, ‘The Inscription in the Synagogue at Rehob’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), 146–53.

14 Naveh, ‘Ancient Synagogue Inscriptions’, 138–39; Gideon Foerster, ‘Synagogue Inscriptions and Their Relation to Liturgical Versions’, Cathedra 19 (1981): 12–40 (23–26) (Hebrew).

15 Levine, Ancient Synagogue, 536.

16 For example: “The people of the East celebrate Simhat Torah every year, and the people of Eretz-Israel every three-and-a-half years” (and sixteenth-century Rabbi Shlomo Luria, the Maharshal, adds: “And on the day [the holiday] is completed, the portion [of the Torah] read in one area [of Palestine] is not read in another”); see Differences in Customs between the People of the East and the People of Eretz-Israel, ed. by Mordechai Margalioth (Jerusalem: Mass, 1938), 88, no. 48, lines 125–26 and notes there, as well as 172–73 (Hebrew).

17 Levine, Ancient Synagogue, 381–411.

18 Ibid., 57–59; Levine, Visual Judaism, 244–51.

19 Levine, Ancient Synagogue, 435–46.

20 Ibid., 238, 386; see also above, n. 14.

21 Fanny Vitto, ‘Rehob’, in Ephraim Stern, New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations, IV, 1272–74.

22 Levine, ‘Inscription in the ‘En-Gedi Synagogue’, 140–45; Levine, Ancient Synagogue, 386–87.

23 Hellenism in the Land of Israel, ed. by John J. Collins and Gregory E. Sterling (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame, 2001); Pieter W. van der Horst, Jews and Christians in Their Graeco-Roman Context: Selected Essays on Early Judaism, Samaritanism, Hellenism, and Christianity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006), 41–50; Lee I. Levine, Judaism and Hellenism in Antiquity: Conflict or Confluence? (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998), 160–67.

24 See Peter R.L. Brown, The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150–750 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1971), and a retrospective on this work some twenty-six years later: Peter R.L. Brown et al., ‘The World of Late Antiquity Revisited’, Symbolae Osloenses 72 (1997): 5–90.

25 See Levine, Visual Judaism, 468–75; idem, ‘Palaestina Secunda: The Setting for Jewish Resilience and Creativity in Late Antiquity’, in Strength to Strength: Essays in Honor of Shaye J. D. Cohen, ed. by Michael L. Satlow (Providence, RI: Brown University, 2018), 511–35.