7. The Judaism of the Ancient Kingdom of Ḥimyar in Arabia: A Discreet Conversion

© Christian Julien Robin, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0219.07

1.0. Introduction

Yemenite Judaism can be described as ‘rabbinic’ from the moment sufficient sources are available in the later Middle Ages.1 It had probably been so for many centuries. One notes, for example, the epistolary links between Yemen’s Jewish communities and Moses Maimonides (d. 1204 CE), who sent them his celebrated Epistle to Yemen.

By contrast, the Judaism of Ḥimyar, the kingdom gradually extending its domination to the whole of ancient Yemen and even, between 350 and 570 CE, over a large proportion of the deserts of Arabia, seems to be different. That is what I shall attempt to demonstrate in this paper. I suggest a reappraisal of the entire file on Ḥimyarite Judaism in order to answer as fully as possible the two main questions: is it possible to claim that Ḥimyar converted to Judaism, and, if so, which type of Judaism was adopted by the Ḥimyarites?

Knowledge of the history of the kingdom of Ḥimyar (whose capital was located at Ẓafār, 125 km south of Ṣanʿāʾ) is relatively recent. Information is derived mainly from the inscriptions discovered following the opening of both Yemeni states to archaeological research at the beginning of the 1970s. A comparison between Hermann von Wissmann’s seminal 1964 article and Iwona Gajda’s 2009 book illustrates this complete change of perspective, which has resumed at a fast pace in recent years despite the war in Yemen.2

In the political field, it appears that Ḥimyar was the leading power in Arabia between approximately 350 and 570 CE, imposing its rule on the entire Peninsula (or at least a large part of it), except during the crisis years of 523–552 CE. In the religious field, the inscriptions illustrate in increasingly clear manner that Judaism was dominant in the kingdom of Ḥimyar from the fourth century CE until around 500–530 CE; they then show that Christianity became predominant, remaining the official religion for some forty years (530–570 CE). These discoveries do not agree with the data from the Arab-Muslim tradition, which emphasizes pre-Islamic Arabia’s isolation, polytheism, anarchy, and intellectual and material poverty.

Dealing with Ḥimyarite Judaism is no easy matter because religious identities are still fluid and difficult to distinguish in the fourth and fifth centuries CE. Furthermore, documentation is scarce and consists essentially of monumental inscriptions that only make the vaguest of allusions to religion. The archaeological remains cannot compensate for the laconic aspect of epigraphic material. One could even say that they are of no assistance at all, since no assuredly Jewish monument has been identified to this day. As for manuscripts, their utility is marginal.

My approach will necessarily be empirical. I will not attempt to answer the many questions that can be asked, but only to outline what is known today. As I already published all the available data on the nature of Ḥimyar’s Judaism in 2015,3 I will recall only the most significant facts here. I will then complete the discussion by examining to what extent the kingdom of Ḥimyar can be described as ‘Jewish’.

2.0. Sources on Religious Practices in the Kingdom of Ḥimyar

Shortly before the end of the fourth century, between 380 and 384 CE, a religious change of considerable importance took place in the kingdom of Ḥimyar. In January 384, the ruling kings, who had just built two palaces, commemorated these events in two inscriptions. The invocation formula concluding these two texts is, in itself, a break with the past: it no longer mentions the support of ancestral deities, as was previously the case, but of a new God: “With the support of the Lord, the Lord of the Sky.”

At first glance, the formula may seem banal and of no great consequence. Several polytheistic deities have a similar name. In South Arabia the great god of Najrān is called ‘The one of the Heavens’ (dhu-Samāwī or dhu ʾl-Samāwī).4 In Eastern Arabia a goddess is called ‘She who is in the Heavens’ (dhāt bi-[ʾl]-Samāwī),5 and in Syria an important god is ‘Master of the Heavens’ (Baʿal-Shamîn, with various orthographical variants of this name in different languages). By looking a little closer, one finds that the break with previous religious practices was a radical one, particularly evident in the evolution of terminology. One is assuredly dealing here with the establishment of a new religion.

Before highlighting this break with previous periods, it is quite useful to recall the nature of the available sources for Arabia’s religious history during the 250 years preceding the formation of Islam.6 These sources belong to three heterogeneous categories: Ḥimyarite inscriptions, external manuscript sources (mainly in the Greek and Syriac languages), and the ‘Arab-Muslim Tradition’ collected during the eighth and ninth centuries CE (second and third centuries of the Hijra).

2.1. Ḥimyarite Inscriptions

Ḥimyarite inscriptions do not inform us beyond 559–560 CE, the date of the most recent text. For the period between 380 and 560 CE, a total of some 150 texts are available, often fragmentary. Some three-fifths of these have a more or less precise chronology, with a date or reference to a known person or event. If one focuses on religious changes, relevant texts are only a few dozen in number. Most often these commemorate building activities.

One can infer the religious orientation of the inscriptions both through their invocations of celestial powers at the end (and, once, at the beginning) of texts and through their petitions. The formulation, which is always concise and stereotyped, and the onomastics are also illuminating.

2.2. External Sources

External sources are of real assistance only in the case of one episode of Arabian history: the long period of political and religious disorder that shook the kingdom of Ḥimyar in the first decades of the sixth century and led to its demise (c. 500–570 CE). Around 500 CE, the kingdom of Ḥimyar, where Jews enjoyed a dominant position, was placed under the tutelage of the Ethiopian kingdom of Aksūm. From then on, it was the (Christian) Negus who designated the ruler. When the Ḥimyarite Christian king died in 522 CE, the Negus nominated a successor. This prince, called Joseph (Masrūq in Syriac and Zurʿa dhū Nuwās in Arabic) soon rebelled. He massacred the Aksūmite garrison sent to Ẓafār by the Negus and then began to spread terror in the regions favourable to the Aksūmite party. He enjoyed the support of the Jewish party, but also of some Christians (apparently those of the Church of the East, called ‘Nestorian’).

Joseph’s vengeful policy provoked the dissidence of Miaphysite (or ‘Monophysite’) Christians in Najrān, who had refused to provide troops. Joseph repressed their rebellion through cunning and deceit and eventually exterminated them, no doubt reckoning that they were a threat on account of the close links they had established with Syria’s Byzantine provinces. Syria and Egypt’s ecclesiastical authorities seized the opportunity to make these victims martyrs of the faith and demanded a rapid response. With their assistance, Aksūm’s Negus gathered ships to carry his army across the Red Sea. Upon their arrival (sometime after Pentecost Day, 525 CE), Joseph was killed. Ḥimyar’s conquest, completed around 530 CE, brought the Negus as far as Najrān. It was followed by the systematic massacre of Jews. The country then became officially Christian. Churches were built and an ecclesiastical hierarchy was established. The conflict, which (at least in the beginning) seems to have been political in nature, is presented in ecclesiastical sources as a war of religion. This account is often quoted uncritically in historical works, especially since historical reports of the Arab-Muslim Tradition have adopted it.

The only documents contemporary with the events—some ten inscriptions written in June and July of 523 CE by the general and officers of the army sent by Joseph to repress the Najrān revolt—make no clear mention of religion. They do not explicitly claim to be Jewish; they do not quote the Bible; they do not boast that the army was invested with a sacred mission by religious authorities. To detect the Judaism of their authors, one can rely only on a small number of terms and turns of phrases meaningful only to specialists.7 Focusing largely on military operations, these documents are mainly aimed at terrorizing insurgents. It is clear that their purpose is political and not religious.

External sources mentioning Late Antique Arabia include above all the historical chronicles in Greek (particularly those of Procopius, Malalas, and Theophanes), and Syriac (like those of the Zuqnin monastery and of Michael the Syrian). One of the Greek chronicles, written by the Egyptian John of Nikiû, is known only in a Geʿez (classical Ethiopian) translation. Another, in Syriac, whose author remains unknown, has reached us only in its Arabic version (the Seert Chronicle). The summary of a Byzantine diplomatic report written by ambassador Nonnosus is also available. Emperor Justinian (527–565 CE) sent Nonnosus to Arabia and Ethiopia at an unknown date, probably in the early 540s. This summary appears in the Bibliotheca of Patriarch Photius (who died in 891 or 897 CE).8

The Ḥimyarite crisis is also known via Greek and Syriac texts produced by churches to celebrate the martyrs of South Arabia and to establish their cults: these are stories in the form of letters (the Guidi Letter, attributed to Simeon of Beth Arsham,9 and the Shahîd Letter in Syriac10), homilies, hymns, and hagiography (the Book of the Ḥimyarites in Syriac11 and the Martyrdom of Arethas in Greek12). Two documents refer to events prior to the crisis of 523 CE: a hagiographical text in Geʿez, probably translated from Arabic, celebrating a priest of Najrān who was persecuted by the king of Ḥimyar Shuriḥbiʾīl Yakkuf (c. 468-480) (the Martyrdom of Azqīr),13 and the consolation letter written by Jacob of Serugh (who died in 521 CE) in honour of the Ḥimyarite martyrs.14

Apart from this Ḥimyarite crisis, the only significant event known to us is the dispatch of an embassy by the Byzantine Emperor Constantius II (337–361 CE) to convert the king of Ḥimyar. The account of this embassy can be found in Philostorgius’s fragments of the Ecclesiastical History transmitted by Photius: Philostorgius, an Arian ecclesiastical historian, was interested in this embassy because one of its leaders, Theophilus the Indian, was himself an Arian Christian.

As a general rule, external sources dealing with Late Antiquity do not focus on South Arabia at all. At most, Byzantine chroniclers make a passing note of desert Arabs when they launch forays into the Empire’s eastern provinces (which make up the Diocese of the Orient) or when the Empire asks them to join an alliance against Sāsānid Persia.

Since Eastern Arabia was conquered by Ḥimyar on two occasions—in 474 CE and 552 CE—one can incidentally mention that the proceedings of the Nestorian Church’s synods, known under the name Synodicon Orientale, and the correspondence of the heads of this church in the Syriac language, include precious information on the bishoprics of the Arab-Persian Gulf until the year 677 CE (i.e., some fifty years after the Islamic conquest).15

In sum, Greek and Syriac sources emphasize that Jews already exerted influence on the kingdom of Ḥimyar around the mid-fourth century CE and then enjoyed a dominant position until approximately the early sixth century CE, at the time of king Joseph.16

2.3. The Arab-Muslim Tradition

In order to reconstruct the history of pre-Islamic Arabia, other data is available from the ‘Arab-Muslim Tradition’, a convenient appellation for the set of texts recorded or written during Islam’s first centuries. These are not really internal sources; rather, they are diverse traditions collected and assembled in the schools of the Islamic Empire located mainly outside Arabia more than two centuries after the events. This tradition is particularly precious for the tribal geography and the study of place names. It has also preserved multiple individual testimonies of the events as experienced by Muḥammad’s companions or their immediate ancestors. This collective memory, however, is flimsy with regard to questions of general import, such as chronology, the pre-Islamic religions, or even the beginning of Arabic writing.

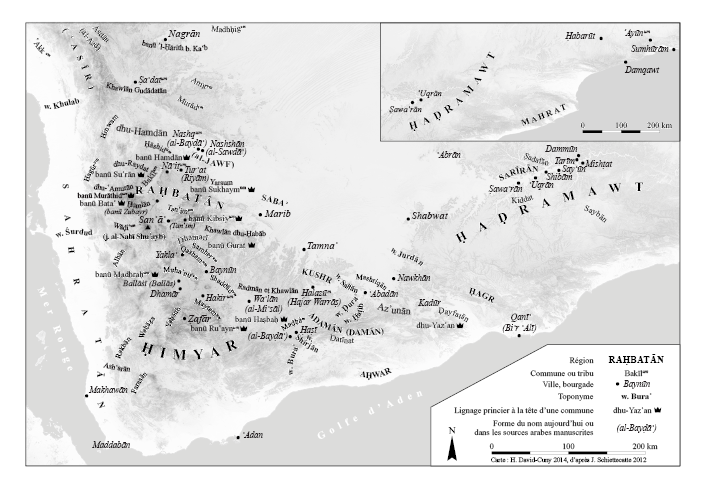

As concerns the Judaism of Ḥimyar, the Tradition retained that a king, Abū Karib Asʿad the Perfect (al-Kāmil), had introduced this religion into Yemen, and that another, Yūsuf Zurʿa dhū Nuwās, had become a Jew and had forced the Christians of Najrān to choose between conversion to Judaism or death. It incidentally signals that various other characters were also Jewish. Finally, four scholars of the Tradition give lists of the regions in which Jews could be encountered. These are: Ibn Qutayba (d. 889 CE),17 al-Yaʿqūbī (d. 897 CE),18 Ibn Ḥazm (d. 1064 CE),19 and Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr (d. 1071 CE).20 Unsurprisingly, it appears that Judaism was solidly rooted in northwestern Arabia (the north of the Ḥijāz) and in the southwest of the Peninsula (in Yemen). More precisely, there were apparently Jews in Ḥimyar (or in Yemen), Kinda, banū ʾl-Ḥārith b. Kaʿb, Kināna, Ghassān, Judhām, al-Aws, al-Khazraj, and Khaybar. Sometimes one of these scholars considers that such-and-such a tribe included Jews in large numbers, while another gives a lower estimate, and a third says nothing on the matter. One should moreover note that the Jewish tribes of Yathrib (today al-Madīna)—al-Naḍīr, Qurayẓa, and Qaynuqāʿ—are not mentioned. This is undoubtedly due to the fact that these tribes were not included in the Great Genealogy of the Arabs, written in the second and third centuries after the Hijra.21

It bears emphasising that the sources just listed were first produced in a Christian environment and then in a Muslim one. None is of Jewish origin.

3.0. The Institution of an Official Religion as Revealed by Inscriptions

For a precise perception of the nature of the new religion established by Ḥimyar’s rulers—I shall come back later to the points proving we are effectively dealing with a new religion—only inscriptions are available, and these are not very many.

3.1. Four Categories of Monotheistic Inscriptions

The corpus on which we rely comprises all the texts later than the official establishment of the new religion and earlier than the final conquest of Ḥimyar by Christian Aksūmites. These are therefore the texts of the period 380–530 CE, whose number is roughly 140.

These inscriptions can be classified into four sets, corresponding to the institutional position of their authors: (1) official inscriptions, whose author is the king; (2) inscriptions whose author is a high official in the king’s service; (3) inscriptions whose author is a prince, ruling a territorial principality; and, finally, (4) inscriptions whose author is a private individual. It seems necessary to distinguish these diverse categories to appreciate as precisely as possible these documents’ meaning and exact scope. Only royal inscriptions define the official orientation used as a model in the entire country. The others provide complementary glimpses that are all the more precious since their composition was not subjected to the same constraints.

3.1.1. Royal Inscriptions

For the period 380–530 CE, sixteen royal inscriptions are available,22 a number that can be reduced to twelve if one discards four fragments that are too small to contribute any substantial information.23 Four texts out of these twelve are particularly significant because they are long and complete, though they make no reference to religion at all. They share two remarkable traits. First of all, they do not originate from Yemen, but from the deserts of Arabia.24 Moreover, they commemorate victorious military campaigns in these deserts. Two others celebrate the building of a place of worship without an invocation to God, either securely in one inscription (Ja 856 = Fa 60) or hypothetically in the other (YM 1200, which is fragmentary). A last text merely lists the ruler and his co-regents with their official title (Garb BSE). Royal texts that contain a religious invocation are five in number:

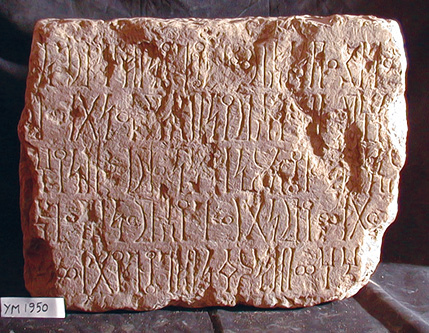

Garb Bayt al-Ashwal 2 (Ẓafār, capital of Ḥimyar), January 384 CE, dhu-diʾwān 493 ḥim. (Fig. 1): a commemoration of the construction of a palace in the capital by king Malkīkarib Yuha ʾmin and his co-regents,25 these being his sons Abīkarib Asʿad and Dhara ʾʾamar Ayman:

...b-mqm mrʾ-hmw mrʾ s1m(4)yn

With the support of their lord, the Lord of the Sk(4)y

RES 3383 (Ẓafār), January 384 CE, dhu-diʾwān 493 ḥim.: a commemoration, with the same date, of the construction of a second palace in the capital by these same rulers, king Malkīkarib Yuha ʾmin and his co-regents, his sons Abīkarib Asʿad and Dhara ʾʾamar Ayman:

...b-mqm m(4)rʾ-hmw mrʾ (s1my)[n]

With the support of (4) their lord, the Lord of the Sky

YM 327 = Ja 520 (Ḍahr, 10 km northwest of Ṣanʿāʾ): a commemoration at an uncertain date of a building several stories high by king Abīkarib Asʿad, then in co-regency with his brother Dhara ʾʾamar Ayman and his sons Ḥaśśān Yuʾmin, Maʿdīkarib Yunʿim, and Ḥugr Ayfaʿ:

[…](5)(n) l-ḏt ẖmr-hmw rḥ[mnn ...]

[…](5) so that Raḥ[mānān] may grant them […]

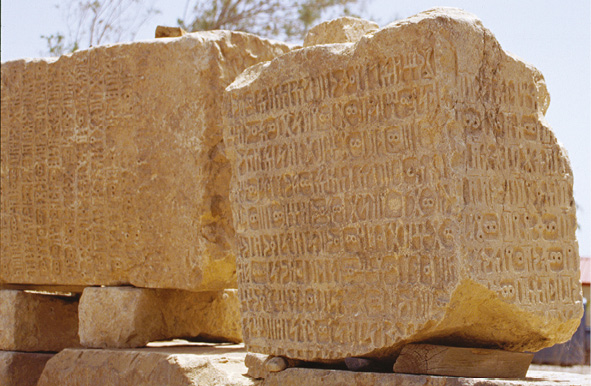

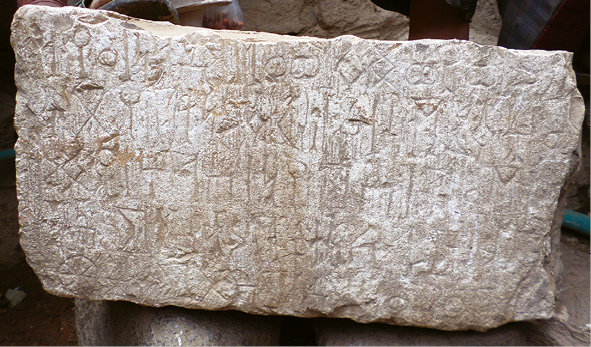

CIH 540 (Ma ʾrib , 120 km east of Ṣanʿāʾ), January 456 CE, dhu-diʾw 565 ḥim. (Fig. 2): the commemoration of an important restoration of the Marib Dam26 by king Shuriḥbiʾīl Yaʿfur:

...b-nṣr w-rdʾ ʾlhn b(82)ʿl s1myn w-ʾrḍn

With the aid and help of God (Ilāhān), ow(82)ner of the Sky and the Earth

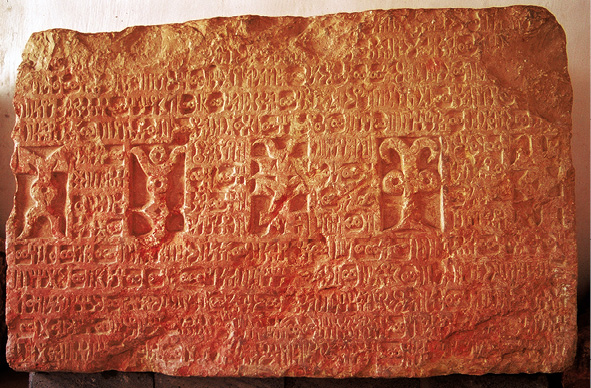

ẒM 1 = Garb Shuriḥbiʾīl Yaʿfur (Ẓafār), December 462 CE, dhu-ālān 572 ḥim. (Fig. 3): a commemoration of the construction of a palace in the capital by the same king, Shuriḥbiʾīl Yaʿfur:

...b-nṣr w-rdʾ w-mqm mrʾ-hmw rḥmnn bʿl (13) s1myn (w-ʾ)rḍ(n)

With the help, aid, and support of their lord Raḥmānān, owner (13) of the Sky and the Earth27

It is remarkable that these five texts contain no dogmatic formulation indicating a precise religious affiliation. From this viewpoint, they are quite different from royal inscriptions later than 530 CE, which begin with an invocation to the Holy Trinity.28

3.1.2. Inscriptions by High Officials in the King’s Service

Several texts of the period 380–530 CE are more explicit regarding their authors’ beliefs. Of these, the most important are the inscriptions written by high officials in the service of the king.

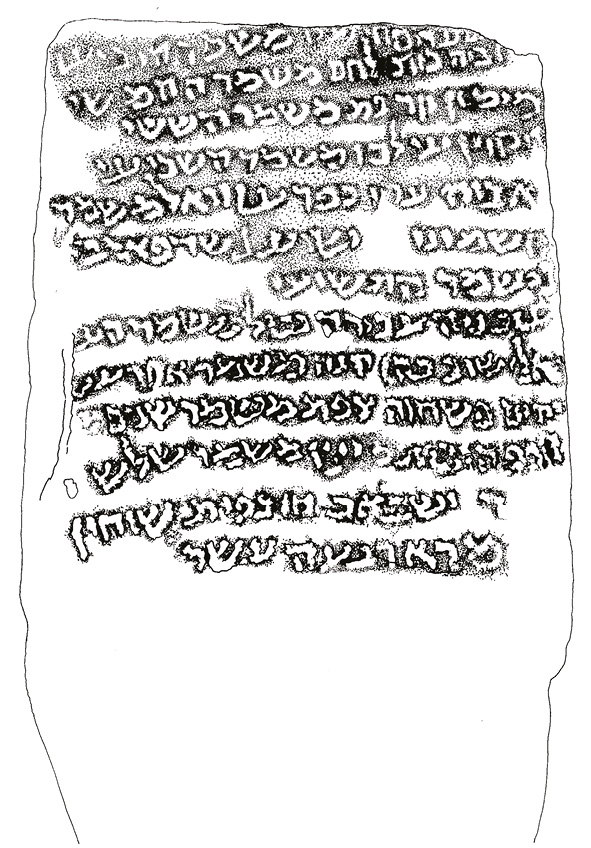

Garb Bayt al-Ashwal 1 (Zafār), undated, whose author does not invoke the ruling king (Abīkarib Asʿad), but only a co-regent, Dhara ʾʾamar Ayman (around 380–420 CE), which makes one think that he is in the service of the latter. The author, Yehuda Yakkuf, is a Jew, as proven by a small graffito in Hebrew incised in the central monogram. As the language bears the imprint of Aramaic,29 he might be of foreign origin (Fig. 4 and 5):

...b-rdʾ w-b-zkt mrʾ-hw ḏ-brʾ nfs1-hw mrʾ ḥyn w-mwtn mrʾ s1(3)myn w-ʾrḍn ḏ-brʾ klm w-b-ṣlt s2ʿb-hw ys3rʾl

With the assistance and the grace of his Lord who created him, the Lord of life and of death, the Lord of the Sk(3)y and the Earth, who created everything, with the prayer of his commune Israel

Ry 508 (Ḥimà, 100 km northeast of Najrān), June 523 CE, dhu-qiyāẓān 633 ḥim. (Fig. 6): a proclamation by the army general whom the Jewish king Joseph (mentioned in the text) has sent to crush the Najrān revolt. The text, which recalls the miltary events of the previous year, implicitly incites the insurgents to submit:

...w-ʾʾlhn ḏ-l-hw s1myn w-ʾrḍn l-yṣrn mlkn ys1f b-ʿly kl ʾs2nʾ-hw w-b-(11)ẖfr rḥmnn *ḏ*n ms1ndn bn kl ẖs1s1{s1}m w-mẖdʿm w-trḥm ʿly kl ʿlm rḥmnn rḥm-k mrʾ ʾt

May God (Aʾlāhān = Elôhîm), to whom the Sky and the Earth belong, grant king Joseph (Yūsuf) victory over all of his enemies. With (11) the protection of Raḥmānān, that this inscription [may be protected] against any author of damage and degradation. Extend over the entire universe, Raḥmānān, your mercifulness. Lord you are indeed

Ry 515 (Ḥimà), undated, but assuredly contemporary with Ry 508, because it is carved to the left of the latter and is written by officers of its author (Fig. 7):

...rb-hwd b-rḥmnn

Lord of the Jews, with Raḥmānān

Ja 1028 (Ḥimà), July 523 CE, dhu-madhra ʾān 633 ḥim.: a new proclamation by the author of Ry 508, but written a month later (Fig. 8 and 9):

(1) l-ybrkn ʾln ḏ-l-hw s1myn w-ʾrḍn mlkn yws1f ʾs1ʾ (vac.) r yṯʾr mlk kl ʾs2ʿbn

May God (Īlān), to whom the Sky and the Earth belong, bless the king Joseph (Yūsuf) Asʾar Yathʾar, king of all the communes

...w-l-ybrkn rḥmnn bny-hw (line 9)

...w-k-b-ẖfrt s1myn w-ʾrḍn w-ʾʾḏn ʾs1dn ḏn ms1ndn bn kl ẖs1s1m w-mẖdʿm w-rḥmnn ʿlyn b(12)n kl mẖd(ʿ)m bn m(ṣ).. wtf w-s1ṭr w-qdm ʿly s1m rḥmnn wtf tmmm ḏ-ḥḍyt rb-hd b-mḥmd

With the protection of the Sky and the Earth and the capacities of men, may this inscription [be protected] against any author of damage or degradation, and Raḥmānān Most-High, ag(12)ainst any author of degradation [... …] The narration of Tamīm dhu-Ḥaḍyat was composed, written, and carried out in the name of Raḥmānān, Lord of the Jews, with the Praised One

Ry 507 (Ḥimà), the same date as Ja 1028, July 523 CE, dhu-madhra ʾān 633 ḥim.: another proclamation by the author of Ry 508 and Ja 1028:

(1)l-ybr(kn ʾl)hn( ḏ-)l-h(w s1)[myn w-ʾrḍn mlkn ys1f ʾs1ʾr Yṯʾr mlk kl ]ʾs2ʿb(n)

May God (Ilāhān), to whom the S[ky and the Earth] belong, [bless the king Joseph (Yūsuf) Asʾar Yathʾar, king of all the] communes

...w-b-ẖfrt (11) [mrʾ s1]myn w-ʾrḍn

With the protection of [the Lord of the S]ky and the Earth

3.1.3. Inscriptions by Princes at the Head of Territorial Principalities

Inscriptions written by princes ruling a principality also yield useful information on the topic. Two examples will suffice here:

Ry 534 + Rayda 1 (Rayda, 55 km north of Ṣanʿāʾ), August 433 CE, dhu-khirāfān 543 ḥim. (Fig. 10): text commemorating the construction of a mikrāb by a Hamdānid, prince of the Ḥāshidum and Bakīlum (dhu-Raydat fraction) communes, under the reign of Abīkarib Asʿad with his four sons as co-regents:

...(brʾ)w w-hs2qr mkrbn brk l-ʾl (2) mrʾ s1myn w-ʾrḍn l-wfy ʾmrʾ-hmw … (3) … w-l-ẖmr-hm ʾln mrʾ s1myn w-ʾrḍn (4) ṣbs1 s1m-hw w-wfy ʾfs1-hmw w-nẓr-hmw w-s2w[f-h]mw b-ḍrm w-s1lm

(The author) has built and completed the synagogue Barīk for God (Īl),(2) Lord of the Sky and the Earth, for the salvation of their lords … (3) … so that God (Īlān), Lord of the Sky and the Earth, may grant them (4) the fear of his name and the salvation of their selves, their companions and of their subj[ects,] in times of war and peace

Ry 520 (according to the text, from Ḍulaʿ a few kilometres northwest of Ṣanʿāʾ), January 465 CE, dhu-diʾwān 574 ḥim.: commemorating the construction of a mikrāb by a Kibsiyide prince of the Tanʿimum commune, 25 km east of Ṣanʿāʾ, probably at the time of king Shuriḥbiʾīl Yaʿfur (who is not mentioned):

...hqs2b(4)w mkrbn yʿq b-hgr-hmw ḍlʿm l-mrʾ-hm(5)w rḥmnn bʿl s1myn l-ẖmr-hw w-ʾḥs2kt-(6)hw w-wld-hw rḥmnn ḥyy ḥyw ṣdqm w-(7)mwt mwt ṣdqm w-l-ẖmr-hw rḥmnn wld(8)m ṣlḥm s1bʾm l-s1m-rḥmnn

(The author) has built from ne(4)w the synagogue Yaʿūq in their city of Ḍulaʿum for his lor(5)d Raḥmānān, owner of the Sky, so that Raḥmānān may grant him, as well as to his wi(6)fe and to his sons, to live a just life and to (7) die a worthy death, and so that Raḥmānān may grant them virtuous (8) children, in the service for the name of Raḥmānān

3.1.4. Inscriptions by Private Individuals

The file also contains a few texts whose authors are private individuals or officials who do not mention their responsibilities or their duties.

ẒM 5 + 8 + 10 (Ẓafār), February 432 CE, dhu-ḥillatān [5]42 ḥim. (Fig. 11): a commemoration of the construction of two palaces under the reign of Abīkarib Asʿad (who is not mentioned):

...b-zkt rḥ[mnn w-b-rdʾ w-...] (5) ʾmlkn ʾbʿl byt[n] rydn w-mrʾ s1my(n)[... ] (6) ḥyw b-ʿml-hmw ʾks3ḥ ṭwʿ ʾfs1-h(m)[w ... ... mrʾ] (7)s1myn bn kl bʾs1tm w-l-yẖmrn-hmw mw[t …] (8) w-ʾmn

With the grace of Raḥ[mānān and the help and ... ] (5) of kings, owners of the palace Raydān, and the Lord of the Sky [ ... ... ...] (6) a life with their works, exemplary(?) of the submission of their selves [... ... the Lord] (7) of the Sky against all evil, and that he may grant a deat[h ... ... ...] (8) and āmēn

ẒM 2000 (Ẓafār), April 470 CE, dhu-thābatān 580 ḥim. (Fig. 12): a commemoration of the construction of a palace under the reign of king Shuriḥbiʾīl (Yakkuf):

...w-b (6) rdʾ w-ẖyl mrʾ-hmw ʾln (7) bʿl s1myn w-ʾrḍn w-b-rdʾ (8) (s2)ʿb-hmw ys3rʾl w-b-rdʾ mrʾ-hmw s2rḥ(b)(9)ʾl mlk sbʾ w-ḏ-rydn w-ḥḍrmwt w-l-(ẖ)(10)mr-hmw b-hw rḥmnn ḥywm ks3ḥ[m]

With (6) the assistance and the power of their lord God (Īlān) (7) owner of the Sky and the Earth, with the assistance (8) of their commune Israel and with the assistance of their lord Shuriḥbi(9)ʾīl king of Saba ʾ, dhu-Raydān and of Ḥaḍramawt. May (10) Raḥmānān give them here (in this house) an exemplary life

CIH 543 = ẒM 772 A + B (Ẓafār), undated; the purpose of this text is unknown:

[b]rk w-tbrk s1m rḥmnn ḏ-b-s1myn w-ys3rʾl w-(2)’lh-hmw rb-yhd ḏ-hrdʾ ʿbd-hmw…

[May it bl]ess and be blessed, the name of Raḥmānān, who is in the Sky, Israel and (2) their God, the Lord of the Jews, who has helped their servant…

Garb Framm. 7, of unknown provenance and date: a fragment of an inscription commemorating the final stage of a construction under the reign of Abīkarib Asʿad, ruling in co-regency with his brother Dhara ʾʾamar Ayman and his son Ḥaśśān Yuha ʾmin:

...b-(r)[dʾ mrʾ-hw mrʾ s1myn w-b] (2) [rdʾ s2ʿb-](h)w Ys3rʾl

With the he[lp of his lord, the Lord of the Sky, with] (2) [the help of his commu]ne Israel

3.2. A Radical Reform

The religious reform that took place around the year 380 CE reveals a radical aspect. From this date, all royal inscriptions became monotheistic. What is even more remarkable is that polytheistic inscriptions disappeared almost immediately.30 Only two such texts are known from the two decades following the reform. However, they are not from the capital, where the power structure controlled public expression, but from the countryside.31

Even if the corpus of documents is not very substantial, the break with the past is radical in terms of both lexicon and phraseology. The most prominent change is the manner of designating God and places of worship, as we shall see later.32 One also notes the radical change in the lexicon relating to the human self. Traditionally, inscriptions mentioned various components, mainly the ‘capacities’ (ʾʾḏn) and the ‘means’ (mqymt), as in Ir 12 / 9 (Ma ʾrib, text going back to the reign of Shaʿrum Awtar, early third century CE):

...w-l-ẖmr-hw ʾlmqh bry ʾʾḏnm w-mqymtm

And may (the god) Almaqah grant them capacities and means to the fullest

This vocabulary also appears in a single monotheistic inscription, CIH 152 + 151 (Najr, near ʿAmrān, 45 km northwest of Ṣanʿāʾ):

[...].t ʾ(ḥṣ)n w-bn-hw s2rḥʾl bnw mrṯdm w-qyḥn br(ʾ)[w w-] (2) [.....] mkrbn l-wfy-hmw w-ẖmr-hmw ʾln bry ʾʾḏnm w-mqymtm [...]

[...].. Aḥsan and his son Shuriḥbiʾīl banū Murāthidum and Qayḥān have bu[ilt ... ... (2) ... ...] the synagogue so that God (Īlān) may save them and grant them capacities and means to the fullest [...]

The inscription is undated and relates to the new religion, since it commemorates the construction of a mikrāb and addresses a prayer to the One God, called Īlān here. It still makes use of the vocabulary of the traditional religion, particularly the substantive nouns ʾʾḏn and mqymt and the verb ẖmr. Later on, only the verb ẖmr (‘to grant’) is still employed. One might suppose that the inscription CIH 152 + 151 goes back to a transitional period between the old and new practices, perhaps around the mid-fourth century CE.

In addition to the change in terminology, one should also note the appearance of some twenty terms and proper nouns borrowed from Aramaic and Hebrew.33

While the inscriptions employ new religious terminology after the religious reform, one nevertheless notices a certain continuity in their structure. Traditionally, inscriptions first mention their authors; they then recall, in the third person, the deeds they accomplished; lastly, they invoke the celestial and terrestrial powers who favoured or supported the operations mentioned. The inscriptions of the period 380–500 CE preserve the same structure. It is only after 500 CE that one observes a radical transformation, illustrated by the invocation to God occasionally placed at the beginning of the text. During the period 500–530 CE, one finds it in a dated Jewish inscription (Ja 1028, Ḥimà, July 523 CE, dhu-madhra ʾān 633 ḥim.):

l-ybrkn ʾln ḏ-l-hw s1myn w-ʾrḍn mlkn yws1f ʾs1ʾ (vac.) r yṯʾr mlk kl ʾs2ʿbn w-l-ybrkn ʾqwln/(2) lḥyʿt yrẖm w-s1myfʿ ʾs2wʿ w-s2rḥʾl yqbl w-s2rḥbʾl ʾs1ʿ (vac.) d bny s2rḥbʾl ykml ʾlht yzʾn w-gdnm

May God (Īlān), to whom the Sky and the Earth belong, bless the king Joseph (Yūsuf) Asʾar Yathʾar, king of all the communes, and may He bless the princes (2) Laḥayʿat Yarkham, Sumūyafaʿ Ashwaʿ, Sharaḥʾīl Yaqbul and Shuriḥbiʾīl Asʿad, sons of Shuriḥbiʾīl Yakmul, (of the lineage) of Yazʾan and Gadanum

The same change can be noticed in a dated inscription where no explicit sign of religious orientation is apparent (Garb Antichità 9 d, Ẓafār, March 509 CE, dhu-maʿūn 619 ḥim.):

[b-nṣr w-](b-)ḥmd rḥmnn bʿl s1myn w-b (2) [rdʾ ](mr)ʾ-hmw mlkn mrṯdʾln ynwf

[With the help and] the praise of Raḥmānān, owner of the Sky, and with (2) [the aid] of their lord king Marthadʾīlān Yanūf

Lastly, one notes this change in two undated inscriptions, one of them Jewish (CIH 543 = ZM 772 A + B, already quoted),34 and the other devoid of any explicit religious orientation (RES 4109 = M. 60.1277 = Ja 117 = Ghul-YU 35, of unknown provenance):

l-ys1mʿn rḥmnn (2) ḥmdm ks1dyn

May Raḥmānān answer the prayers of (2) Ḥamīdum the Kasdite

Changing the location of the invocation to God in the text becomes systematic in Christian inscriptions, all of which are later than 530 CE. This change no doubt emphasizes that God is now conceived of as the main player in earthly matters and that nothing can be accomplished against His will.35

If the religious break with the past around 380 CE is both radical and systematic, it is also the final stage of an evolution observable over several decades. Only half of the inscriptions from the fourth century prior to 380 CE continue to celebrate or invoke ancient deities, which was previously the norm for all inscriptions. The others have already adopted the One God or abstain from making any reference to religion Those postdating 380 CE invoke no divinity other than the One God, with the possible exception of a single text whose precise date is uncertain.36

Most temples were already deserted during the third and fourth centuries CE.37 More precisely, one ceases to find in these places of worship inscriptions commemorating offerings, which implies that the wealthiest worshippers no longer entered them. The only temple that still received offerings after the mid-fourth century CE was Marib’s Great Temple, dedicated to the great Sabaean god Almaqah. In this temple, excavators have uncovered some eight-hundred inscriptions for the period between the first and fourth centuries CE. The last dated inscription comes from 379–380 CE.38 It is likely that the authorities closed the temple immediately after this date, since official policy from then on was clearly unfavourable to polytheism. But it cannot be excluded that the closure was a little later and that the temple had been visited discreetly by worshippers for some time. One can moreover notice that the entrance hall was refurbished around this period, as attested by the inscribed stelae reused in the paving.39 This redevelopment is probably related to a new use of the monument.

Of course, inscriptions, whose conception and carving were costly and whose authors belonged to the elite class, do not reflect exactly the religious practices of the entire society. One may even suspect that they do not even reflect these elites’ real religious practices, but only those the authorities encouraged. It is indeed quite difficult to believe that the entire group of princely lineages unanimously and simultaneously rejected polytheism in order to convert to a new religion. Inscriptions teach us above all that in public space, from 380 CE, only the new religion could be mentioned.

The date of the break can be pinpointed with a certain measure of precision. It occurred for certain before January 384 CE and probably a little before. Since the last polytheistic inscription in Marib’s great polytheist temple bears the date of 379–380 CE,40 I shall retain the interval 380–384 CE. It is not impossible, however, that the official establishment of the new religion took place a little earlier, if indeed one supposes that it did not immediately entail the abandonment and closure of polytheistic temples.41

An external source—and an imprecise one, at that—nevertheless agrees quite well with the data from the inscriptions. The already-mentioned Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius recalls that the Byzantine Emperor Constantius II (337–361 CE) sent an embassy to Ḥimyar’s king to invite him to convert to the Christian faith.42 One can therefore surmise that Constantius II had been informed that Ḥimyar was favourable to such as invitation. The embassy’s date is not known for certain, but it can probably be dated to the early 340s CE. One of the embassy’s leaders, the Arian Christian Theophilus the Indian, recalls that the embassy did not achieve its aims because of the Jews in the king’s entourage, but that the king (whose name is not given) agreed to build with his own funds three churches in the capital and in two of the country’s ports (implicitly for the Romans residing there).43

3.3. Problems the Change of Religion Solved

The adoption of a new religion is not a trivial or insignificant act. This was the antique equivalent of a modern revolution. The fourth century CE was a period where radical change of religion became a surprising trend in the manner of the nineteenth century liberal revolutions. Armenia paved the way, followed by Caucasian Iberia (Georgia), the Roman Empire, Ethiopia, the Arabs (of the Syrian desert and the Sinai), and then Ḥimyar.

The reasons why the king of Ḥimyar established a new religion are a matter of guesswork. The authorities’ main ambition was to reinforce the cohesion of the empire and ensure the regime’s stability. Prior to Ḥimyar’s conquests, religious diversity was great. Each kingdom had its own great god and its own pantheon (that is to say, a small number of deities that were the focus of official worship practiced collectively). The great god had his great temple in the capital and an additional temple in each of the kingdom’s major regions, with the exception of those where a local god could be worshipped in place of the great god, this being a more or less formally declared assimilation.

In Saba ʾ, the great god was Almaqah, who had his great temple in Marib; in Qatabān, it was ʿAmm, with his great temple in Tamnaʿ; and in Ḥaḍramawt, it was Sayīn, whose great temple was in Shabwat. In these kingdoms founded in remote antiquity (before 700 BCE), the distribution of rites could be completely superimposed on the political map. In other words, in any kingdom, only the subjects of this kingdom would participate in official rites; reciprocally, belonging to a kingdom (particularly following an annexation) implied participating in the rites in honour of the kingdom’s great god.

In the kingdom of Ḥimyar, founded in the first century BCE, matters were different. Political unity did not (apparently) entail the establishment of official collective rites. Each of the kingdom’s regions preserved its traditional rites, with the god ʿAthtar in the north and the god ʿAmm in the southeast.

Ḥimyarite expansionism, which had resulted in the annexation of Qatabān, Saba ʾ, and Ḥaḍramawt (between 175 and 300 CE), did not immediately affect religion. Pilgrimages to Almaqah and Sayīn continued to be held as normal for a certain time. Religious diversity nevertheless did not go without posing some practical issues. As a result of the redistribution of territories, princedoms often united communes worshipping different deities. The Ḥimyarite ruler was obviously fearful of ancient cults being used by political competitors to organize hostile forces.

Despite not having been very interventionist in religious matters, the Ḥimyarite ruling class decided to change policy radically around 380 CE. This was perhaps because new problems had then arisen. Three of these can be recognized.

First of all, the rejection of ancient religious practices seems to have been a general phenomenon, at least in the princely lineages of the mountains. Reform could therefore be a response to the demand for a more personal and spiritual religion.

Secondly, the king of Ḥimyar was firmly requested by both Sāsānid Persia and Byzantium to choose his camp at a moment when these two powers were fighting over control of the Peninsula. As early as the 340s CE, as already mentioned, Byzantium had sent an embassy with sumptuous gifts to convince the Ḥimyarite ruler to accept baptism; moreover, the Christian mission was beginning to gain followers in the Arab-Persian Gulf. Ḥimyar finally refused to join Byzantium’s alliance because its hereditary enemy, the Ethiopian kingdom of Aksūm—a traditional ally of the Romans—was already well on its way to conversion to Christianity. In such a context, the choice of a new religion could be a way of resisting Byzantine pressure precisely at a moment when the Byzantine throne was weakened.44

One should also take financial aspects into account. In ancient Arabian society, authorities benefitted from three available sources of revenue. Of these, the most important consisted of taxing a certain proportion of harvests and the natural growth of herds. Temples were responsible for this form of taxation, which went back to very ancient times, even as ancient as the very development of agriculture, perhaps as early as the third millennium BCE. Inscriptions distinguish two types of taxes, called ʿs2r45 and frʿ, whose nature and amount are unknown.46

In South Arabian temples, archaeologists have discovered a large number of inscriptions commemorating offerings. It would appear that a large fraction of these offerings were not spontaneous gifts thanking the deity for a favour or the accomplishment of a promise, but an ostentatious means of paying taxes. Indeed, one should note that offerings were habitually placed on a stone base on which the donor had carved an inscription; for the donor, this inscription, theoretically commemorating the rite, was an occasion to flaunt his status.

Temples possessed not only an immense treasury, consisting of innumerable accumulated offerings, but also property (no doubt in the form of landed estates, livestock, and financial means). It is therefore likely that they played an important part in economic life. Many monetary emissions show a divine symbol. These symbols appear particularly on the coinage of Saba ʾ (where all minted coins carry the symbol of the great Sabaean god Almaqah) and of Ḥaḍramawt (where many series bear the name of Sayīn). We are not yet, however, in a position to assess how the part played by the temple in coinage was reconciled with that of the king.

The second source of revenue consisted of custom duties on trade, mainly taxes on markets and passports, to which one can add the benefits of services (accommodation, food, water, storage, security). Apparently, this source of income, which only became substantial in the first millenium BCE, was a prerogative of political power. Trade was a matter for the king only, as he controlled markets and the circulation of goods. A few inscriptions in temples, however, indicate that the offering being commemorated was financed with the benefits of trade. It is not known in this case whether the authors of inscriptions paid a tax to the deity or whether they were showing their gratitude for returning safe and sound from a perilous journey after making comfortable profits.47

The third source of income was the seizure of war booty. This booty was habitually destined for political rulers, but sometimes also for the temple. Thus, a handful of inscriptions, all dating from a brief period of the early third century CE, commemorate offerings made in the great temple of the god Almaqah in Marib with the booty taken from Shabwat and Qaryatum. The meaning of this exception is unknown. Did the king at the time dedicate his share of the booty to the god to thank him for an exceptional favour?

This brief reminder shows that taxes deposited in the temples played an important part in economic life. Most temples ceased receiving offerings commemorated by inscriptions—no doubt those that had the greatest value—sometime during the third or fourth century CE. In tandem with the crisis of polytheism, they also lost part of their financial resources and could not play the same important role in the economy.

As for the landowners of estates and herds who rejected ancestral religious practices, they were, by the same act, freeing themselves of taxes they owed the temple. State intervention was therefore necessary to reorganize public finances. Nothing is known, unfortunately, of this reorganization. One can only notice that no South Arabian emission of coins postdates the religious reform.

In summary, this religious reform had several aims. The first was to re-establish the old correspondence between political groups and the distribution of religious rites. The second was to resist Byzantine pressure. The third consisted in replacing the temple as the beneficiary of taxation. One can undoubtedly add a last goal: the conversion to a new religion, which transformed the past into a tabula rasa and obliterated past times, enabled the monarchy and principalities to seize treasures accumulated in polytheist sanctuaries.

4.0. The New Religion’s Main Traits

The most noteworthy novelties brought by the new religion were threefold: the appearance of a single God with multiple appellations, clearly distinguishable from the innumerable deities of the past; the institution of a new place of worship; and, finally, the appearance of a new social entity called ‘Israel’.

4.1. One God

A single God replaced the old polytheistic deities of South Arabia: Almaqah, ʿAthtar, Ta ʾlab, Wadd, Sayīn, dhāt-Ḥimyam, dhāt-Ẓahrān, al-ʿUzzà, Manāt, al-Lāh, al-Lāt and many others. This single God was designated in multiple ways. The earliest attestations called him ‘Owner of the Sky’ (bʿl s1myn), ‘Lord of the Sky’ (mrʾ s1myn), ‘God’ (īlān, ʾln), or ‘God, Lord of the Sky’ (ʾln mrʾ s1myn). This new God was fundamentally a celestial power. However, very quickly, it was specified that this God of the Sky also ruled the Earth: He was “the Lord of the Sky and the Earth, who has created all things” (mrʾ s1myn w-ʾrḍn ḏ-brʾ klm).

All these denominations are interchangeable because they are evenly distributed in the various inscription categories I have determined.48 The name Īlān includes the root ʾl, which means ‘god’, and the suffix definite article -ān. It deserves a few words of explanation. In the Near East of the second millennium BCE, a supreme god named Ēl or Īl was worshipped; from his name the appellation īl ‘god’ was derived (if indeed the derivation did not occur in the opposite way).

In South Arabia, this Near Eastern heritage took two forms. In Sabaʾ, a god Īl was worshipped in very ancient times, from around the eighth to sixth centuries BCE. Nevertheless, to designate a divine being, a derivative ʾlh (vocalized probably as ilāh) was used. It is found, for instance, in the very common syntagm “dhu-Samāwī god of Amīrum” (ḏ-s1mwy ʾlh ʾmrm). This appellative ʾlh preserves the same spelling when a suffix is added. See, for example, “his god dhu-Samāw(4)ī owner of Baqarum” (ʾlh-hw ḏ-s1mw(4)y bʿl bqrm)49 or “his god Qaynān owner of Awtan” (ʾl(4)h-hw qynn bʿl (5) ʾwtn).50 With the definite article, ʾlhn (ilāhān) means ‘the god’ in a polytheist context. See, for instance, “the sanctuary of the god dhu-Samāwī, god of Amīrum” (mḥrm ʾlhn (3) [ḏ-s1mw]y ʾlh ʾmrm).51 ʾlhn is also attested as one of the names of the monotheist god already mentioned in CIH 540 as “God (Ilāhān), ow(82)ner of the Sky and the Earth” (ʾlhn b(82)ʿl s1myn w-ʾrḍn). The noun ʾlh is assuredly a derivative of ʾl with a consonant added to fit the triliteral mould, as indicated by the unusual form of its plural: ʾlʾlt, which was formed by the doubling of the root ʾl.

In Qatabān, where the god Īl is not attested, one notices a substantive noun ʾl meaning ‘god’, often designating the tutelary god (called s2ym in Sabaic):

…s1qnyw l-ʾl-s1m w-mrʾ-(3)s1m ḥwkm nbṭ w-ʾlh-s1ww ʾlhy bytn (4) s2bʿn

[the authors] have offered to their god and to their (3) lord Ḥawkam Nabaṭ and to his deities, the deities of the temple Shabʿān52

The noun ʾl can also be used for the god of a region: “with (the god) ʿAmm, with (the god) Ḥawkam and with Ḥbr god of Shukaʿum” (b-ʿm w-b-ḥwkm w-b-ḥbr ʾl s2kʿm).53 Finally, it can refer to any god whom it is not necessary to name if the context is clear: “[the authors] carried out the restoration of the basin belonging to the treasury of the god at Bana ʾ” (…s1ḥdṯ ṣʾrtn bn mbʿl ʾln b-bnʾ).54 The plural of ʾl, attested only in the construct state, is ʾlhw or ʾlhy.

In polytheistic Ḥimyarite inscriptions, written in a Sabaic showing certain peculiarities, the usual term for ‘god’ is the substantive noun ʾl, without /h/, as in Qatabānic. See, for example, “(the author) has offered to his god and his lord Rgbn mistress of Ḥaẓīrān…” (hqny ʾl-h(4)w w-mrʾ-hw rgbn bʿlt ḥ(5)ẓrn).55

The One God of the Ḥimyarites, sometimes called Īlān ‘the God’ in the earliest inscriptions, soon received a new name derived from Aramaic, Raḥmānān ‘the Merciful’. Its oldest attestation dates from approximately 420 CE. Between 420 and 450 CE, Raḥmānān became increasingly frequent, but would freely alternate with six other names. Among these, the most significant was ʾʾlhn, for which only one attestation is known (Ry 508). One can analyse ʾʾlhn as a noun of the ʾfʿl scheme, which expresses a plural. God is therefore designated here by a plural of ʾlh, which is not the usual plural (in general, ʾlʾlt, and twice ʾhlht).56 The term ʾʾlhn (perhaps to be vocalized as Aʾlāhān) is therefore particularly interesting, since it is an innovation that apparently closely copies Hebrew ʾĕlōhīm.

The name Raḥmānān, which one can find in Qurʾānic Arabic under the form al-Raḥmān, refers to the quality of mercy.57 This quality, which in Judaism is initially less commonly associated with the idea of God,58 became common in Late Antiquity.59 As a name for God, it is frequent in the Babylonian Talmud, but less so in the Jerusalem Talmud. It is attested in the Targum; one can also find it in Christian Palestinian Aramaic and in Syriac.60 The fact that one of the names for God in the Qurʾān refers to the idea of mercy (or, rather, of beneficence61) appears to be significant. Muḥammad began his mission with apocalyptic overtones by announcing the End of Time and the Last Judgment. In such a context, the qualities of God are rather anger and intractable justice. The adoption of al-Raḥmān as a name of God (or as one of His names) no doubt reflects a shift that can be associated with the foundation in 622 CE of the theocratic principality of al-Madīna. From then on, the End of Time is not as close as previously believed, because God has shown himself to be compassionate. Muḥammad now prepares for the long term and worries more about the functioning of his community.

The name Raḥmānān is sometimes rendered more explicit by a qualifier. In a clearly Jewish text dating to July 523, he is described as “Most-High” (rḥmnn ʿlyn in Ja 1028 / 11). Elsewhere, it is the adjective ‘merciful’ that one can find in a text whose religious orientation is unclear (rḥmnn mtrḥmn, in Fa 74 / 3, Ma ʾrib, July 504). Finally, in a text with Jewish undertones, but dating to the Christian period, one finds “Raḥmānān the King” (rḥmnn mlkn, Ja 547 + 546 + 544 + 545 = Sadd Ma ʾrib 6, November 558 CE). Only once the reference to Raḥmānān is made explicit by a second term, bhṯ (Robin-Viallard 1 = Ja 3205, Ẓafār, May 519 CE, dhu-mabkarān 629 ḥim.). Unfortunately, the meaning of the latter is uncertain:

...w-l-ys1mʿn-h(5)mw rḥmnn w-kl bhṯ-hw w-ʾẖw(6)t-hmw

May (5) Raḥmānān with all His powers (?) listen to them, and to their bro(5)thers

It is quite remarkable that the names of the one God evolved in comparable ways in both the kingdoms of Ḥimyar and Aksūm. In the inscriptions written by king ʿEzānā following his official conversion to Christianity towards the beginning of the 360s CE,62 one notes the use of neutral names appealing to many different religious orientations. In particular, one finds the reference to God as a celestial power: “the Lord of the Sky who, in the Sky and on the Earth, is victorious for me” (ʾɘgzīʾa samāy [za-ba] samāy wa-mədr mawāʾī līta); then shortened as “the Lord of the Sky” (ʾɘgzīʾa samāy); “the Lord of the Universe” (ʾɘgzīʾa kwelū); “the Lord of the Earth” (ʾɘgzīʾa bəḥēr) (RIÉth 189 in vocalized Geʿez and RIÉth 190 in the South Arabian script). By contrast, in the sixth century CE, the Trinitarian faith appears to have become strongly rooted when one looks at RIÉth 191 (king Kālēb, around 500 CE); RIÉth 195 ([king Kālēb], around 530 CE); and RIÉth 192 (king Waʿzeb, in the years 540 or 550 CE). It is sufficient to quote here the beginning of the first inscription:

God is power and strength, God is powerful (2) in battle.63 With the power of God and the grace of Jesus Christ, (3) son of God, the Victor in whom I believe, He who gave me a kingdom (4) of power with which I subjected my enemies and trampled the heads of those who hated me, he who watched (5) over me since my childhood and placed me on the throne of my forefathers, who has saved me. I have sought protection (6) from Him, Christ, so I succeed in all my endeavours and live in the One who pleases (7) my soul. With the help of the Trinity, that of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit (RIÉth 191 / 1–7).

4.2. A New Place of Worship Called the mikrāb

The new religion had its own place of worship, an expression I shall return to shortly. In polytheistic inscriptions, places of worship were described by a whole series of terms, the most common being maḥram (mḥrm) ‘sanctuary’ and bayt (byt) ‘temple’. After 380 CE and until approximately 500 CE, the place of worship was systematically called mikrāb (mkrb). After 500 CE, two new terms appeared: bīʿat (bʿt) and qalīs (qls1), both meaning ‘church’, the first a loan from Syriac, bîʿotô ‘dome’ (from the word for ‘egg’), and the second from the Greek ekklêsia.

The term ‘place of worship’ must be understood as a generic name for all consecrated monuments and spaces where individual or collective religious rituals (oracular consultations, offerings, sacrifices, prayers, atonement) were performed at determined moments or at any time of the year. Many places of worship had other functions, especially for studying, teaching, or hosting travelers; some played the part of a banking institution for the faithful or the local economy. These secondary functions are difficult to pinpoint. In the case of the mikrāb, they are never explicitly mentioned in sources. They cannot even be confirmed by archaeological observation, because no mikrāb has yet been identified. The hypothesis suggesting that a building in Qanīʾ is a synagogue rests on meager evidence that does not appear to be decisive.64

The vocalization of mkrb is certainly mikrāb. This can be deduced from attestations of the word in Yemen’s dialects (as noted by two nineteenth-century travelers) and in Geʿez. According to Eduard Glaser,65 in eastern Yemen (Mashriq), the noun mikrāb was used (but also mawkab and muqāma) to designate a polytheistic temple. As for Ḥayyīm Ḥabshūsh, he noted that in Haram (in the Jawf), mikrab was the term used to describe the portico of an ancient temple.66 Though the two travelers indeed recorded the same word, they differ on the length of the vowel /a/. The most likely vocalization is that given by Glaser, who had a robust philological background; moreover, Glaser took notes in the field, while Ḥabshūsh wrote from memory more than twenty years after his journey. The noun mikrāb is also attested in Geʿez under the form məkwrāb, which designates a synagogue or the Temple of Jerusalem.67

The meaning of the root KRB, to which the noun mkrb and other South Arabian words are related—in particular, the title of mkrb (traditionally vocalized as mukarrib) borne by rulers enjoying a dominant position in South Arabia—has been a matter of discussion for quite some time. That KRB expresses the notion of blessing68 is a reasonable assumption, both in monotheistic texts and in earlier polytheistic written sources. Clearer attestations can be found in the greetings at the beginning of correspondence, some of which have survived as copies on wooden sticks. See as polytheistic examples YM 11738 = X TYA 15 / 1-2 or YM 11733 = X TYA 9 / 2:

...w-s2ymn (2) l-krbn-k

May the divine Chief (i.e., the god Aranyadaʿ of Nashshān) (2) bless you

or

...w-s2ymn l-krbn-kmw

May the divine Chief bless you

For a monotheist example, see X.SBS 141 = Mon.script.sab 6 / 3:

... w-rḥmnn ḏ-b-s1myn l-ykrbn (4) tḥrg-kmw b-nʿmtm w-wfym

May Raḥmānān, who is in the Sky, bless (4) your Lordship with good fortune and well-being69

The noun mkrb can therefore mean ‘place of blessing’.

The root KRB of Sabaic is apparently related to the Hebrew and Arabic root BRK, which also expresses the notion of ‘blessing’. This is one of the most secure instances of a metathesis in a Semitic root. Sabaic is the only language where the two roots are attested at the same time, both the local root KRB and the root borrowed from the Jewish-Aramaic BRK in the times of monotheism.

Attestations of the noun mikrāb number ten. The mikrāb is on six occasions built by well-known figures, the king or the prince.70 A text details that a mikrāb called Yaʿūq included an assembly room (ms3wd) and porticoes (ʾs1qf).71 A second document, which is unfortunately fragmentary, suggests that another mikrāb included a kneset, apparently another type of assembly room.72

Of the five mikrāb whose names have come down to us, three of them bear a name borrowed from Hebrew or Judaeo-Aramaic. They are (once) Ṣwryʾl,73 from Hebrew ṣūrīʾēl, ‘God is my rock’, the name of a person in Num. 3.35; and (twice) Brk (or Bryk), from Aramaic barīk, ‘blessed’.74 The mikrāb are the only South Arabian buildings for which names of foreign origin are attested.

One of the mikrāb is located in a cemetery meant exclusively for Jews. The inscription of Ḥaṣī (220 km southeast of Ṣanʿāʾ, MAFRAY-Ḥaṣī 1, Fig. 13) mentions the transformation of four plots to create a cemetery only for Jews. It details that a fourth plot was added to the three plots and the well already conceded to the mikrāb Ṣūrīʾel. The mikrāb, which is entrusted to a custodian (ḥazzān), drawing its subsistence from the revenues of a well, owns landed estates.

The name mikrāb is not merely the transposition of one of the Greek terms used to name a synagogue, the proseuchê, literally ‘prayer’, or sunagogê, literally ‘meeting’. The mikrāb would therefore be an original institution and not just a copy of an institution of the Mediterranean Jewish Diaspora.

4.3. A New Social Entity Called ‘Israel’

Together with the new religion, a new social entity called ‘Israel’ appeared for the first time in South Arabia. The authors of three inscriptions mention “their commune Israel.”75 One is Ḥimyarite and one is apparently of foreign origin. In the third (fragmentary) text, the author’s name is lost. In these inscriptions, the invocation of Israel seems to replace the old invocations of the commune of origin. Thus, one can hypothesize that the Jews—Jews of Judaean origin as well as converts (or proselytes) and perhaps ‘sympathizers’—were reunited in a new social entity called ‘the commune Israel’.

It is probable that this commune Israel was conceived as a way of unifying tribal society and replacing the old communes. However, as Jérémie Schiettecatte has pointed out to me, it is only attested in the capital’s cosmopolitan environment. In the provinces, local power was always held by princes, who never failed to mention the communes over which these princes exerted authority (communes which, indeed, appear to have still been in existence).

The new entity, whose name suggests it was based on religion, was not a simple copy of the ancient communes. It had a quasi-supernatural dimension since, in the blessing formula introducing a text, it appears between two names for God (CIH 543 = ẒM 772 A + B):

[May it bl]ess and be blessed, the name of Raḥmānān, who is in the Sky, Israel and (2) their god, the Lord of the Jews, who has helped their servant…

The name Israel is quite significant. It undoubtedly betrays the hope of a restoration of the historical Israel. One also notices that Israel is a name that can only come from Jews of Judaean origin, since this is how Judaean Jews designate themselves. Logically, in these invocations, the commune Israel is invoked before the king himself.

4.4. A New Monotheistic Religion Shared by All?

Having examined the main aspects of the new religion, how do we know we are speaking of a single religious creed and not of several?

At first glance, the variety of the names given to God suggests diversity rather than unity. It quickly appears, however, that these names are interchangeable, since two or more are often mentioned together.76 One can thus find in the same text:

Raḥmānān and ‘Lord of the Sky’: ẒM 5 + 8 + 10; Ry 520; CIH 537 + RES 4919 = Louvre 121; Garb Antichità 9, d

Raḥmānān and ‘Lord of the Jews’: Ry 515; Ja 1028; CIH 543 = ẒM 772 A + B

Raḥmānān and ‘God (Īlān) master of the Sky and the Earth’: ẒM 2000

Raḥmānān and ‘God (Īlān) to whom the Sky and the Earth belong’: Ja 1028

Raḥmānān and ‘God (Aʾlāhān) who owns the Sky and the Earth’: Ry 508

The unity of this corpus is moreover founded on the fact that it presents notable differences not only with respect to the inscriptions that precede it, but also with respect to those that follow, i.e., Christian inscriptions of the period 530–560 CE. These Christian inscriptions can be distinguished by a new way of designating God, a new name for places of worship, and a new place in the inscription for invocations.

One still notices that the faithful of various tendencies visit the mikrāb. This building was intended for observant Jews, since one was located in the Jewish cemetery of Ḥaṣī. It is probable, however, that the mikrāb was also open to others, this conclusion deriving from the fact that kings and princes intended to build them everywhere.

Unfortunately, there is no doctrinal term that allows one to isolate a group of inscriptions and contrast it with another, apart from the fact that some royal inscriptions are more laconic than others, an observation to which I shall return. It is true that the corpus is too restricted to make this point imperative.

On these grounds, there is no reason to surmise that the inscriptions of the period 380–530 CE do not form a homogeneous group. In all likelihood, they refer to a single religion.

5.0. A Variety of Judaism

If one asks about the nature of this religion, there is no doubt that it is a form of Judaism. Among lexical, onomastic, and doctrinal indexes allowing one to place the new religion within the religious panorama of the Near East (polytheistic, Jewish, Christian, Manichaean, Gnostic, or Zoroastrian), many emphasize proximity with Judaism only; some point towards both Judaism and Christianity; but none suggest a link with Christianity only or with another type of religious worship.

5.1. Proofs of Judaism

The most decisive proofs of the proximity to Judaism are the four attestations of the name Israel (ys3rʾl) and the three attestations of the syntagm ‘Lord of the Jews’, a matter on which I wish to return. One can add to these the discovery of two texts in Hebrew: the already-mentioned Hebrew graffito in the monogram of Yehuda’s inscription and the list of priestly families in charge of the divine service in the Temple of Jerusalem (mishmarōt) (Fig. 14 ).77

The ritual exclamations amen (ʾmn) and shalom (s1lwm) provide another argument in favour of Judaism. Amen (ʾmn) and salām (s1lm), however, can also be found in Christian inscriptions. It is therefore only the spelling s1lwm with the mater lectionis /w/ that securely points to Judaism.78

Most of the lexical borrowings from Aramaic could originate from either Jewish-Aramaic or Syriac and Christian Palestinian Aramaic. Two loanwords, expressing the notions of ‘prayer’ (ṣlt) and ‘favour, (divine) grace’ (zkt), are particularly interesting because they are also found in the Qurʾān some two hundred years later with the meanings ‘prayer’ (in Arabic, ṣalāt) and ‘legal alms’ (in Arabic, zakāt), names of two of the five pillars of Islam.79 This does not mean these Aramaic terms were borrowed by Ḥimyar and, from there, passed into Arabic.80 Patterns of transmission were no doubt diverse. It is remarkable nevertheless that some Qurʾānic loan-words were already rooted in Yemen well before Islam.

The Ḥimyarite anthroponymy has three names that come from the Hebrew Bible. Among them, one, Yehuda (yhwdʾ, ywdh), is always Jewish,81 but two others, Joseph (Yūsuf, ys1wf or ys1f) and Isaac (Yiṣḥaq and Isḥāq, yṣḥq and ʾsḥq), can also be Christian. The spelling of Isaac varies by language: in Sabaic, it is yṣḥq, exactly like ancient Hebrew; but in pre-Islamic Arabic, like in Aramaic, it is ʾsḥq.82 The most conservative spelling, yṣḥq, is probably evidence of an affiliation with Judaism.

On this matter, one notices that the conservation of the initial /y/ (replaced by a vocalic glottal stop in Aramaic and Arabic) can also be seen in the spelling of the name Israel as ys3rʾl.

Mention should lastly be made of epigraphic texts proving people traveled between Ḥimyar and Palestine, and some Ḥimyarites expressed a strong bond with the Land of Israel. First of all, a passing reference should be made to the grave owned by the Ḥimyarites in a collective tomb at Bet Sheʿarim in the Galilee.83 Another example is a funerary stele written in Aramaic, probably originating from a necropolis close to the Dead Sea, whose author is Yoseh son of Awfà, who

passed away in the city of Ṭafar (= Ẓafār) (3) in the Land of the Ḥimyarites, left (4) for the Land of Israel and was buried on the day (5) of the eve of the Sabbath, on the 29th (6) day of the month of tammûz, the first (7) year of the week [of years], equivalent (8) to the year [400] of the Temple’s destruction’ (Naveh-Epitaph of Yoseh = Naveh-Ṣuʿar 24).

Ḥimyar’s conversion to Judaism was not a simple parenthesis in time before its very brief conversion to Christianity and then to Islam. It left a durable mark on Yemen. A first proof of this is the importance and influence of Yemen’s Jewish community until modern times.84 A second indication (obviously indirect) is provided by the works of the greatest of Yemeni scholars, al-Ḥasan al-Hamdānī, who lived in the tenth century CE: as opposed to what all of Arab literary production says, he expresses an astonishing religious neutrality when speaking of Yemen and of Arabia, as if he wanted to emphasize that in Yemeni history, Muḥammad and Islam were but one episode following many others.

5.2. A Non-Rabbinic Form of Judaism

If indeed inscriptions reveal that Ḥimyar converted to Judaism, it is relevant to ask what type of Judaism Yemenis were following. For quite some time, the prevailing opinion was that the various orientations of the Second Temple period (Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, Zealots), well-known thanks to Flavius Josephus, did not survive the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. In recent decades, however, a hypothesis stressing that some older currents survived has become dominant; as a consequence, ‘rabbinization’ would not be an immediate consequence of the Second Temple’s destruction but a long process that concluded only at the very end of Late Antiquity or even in Islam’s early years.

If indeed the existence of several currents of Judaism after 70 CE is generally accepted, opinions differ strongly as to their number, their definition, and their names (rabbinic, scriptural, priestly, Hellenistic, synagogal, etc…). This is not surprising since they diverged on a whole series of central questions relating to Judaism’s history, beginning with the date and composition of the Torah and the origins of the synagogue.

Since I am not a specialist on these matters, I will not give a definite opinion on post-70 Judaism but shall restrict my scope to writing an inventory of characteristics Ḥimyar’s Judaism shared with such-and-such a current.

On at least one point of doctrine (the issue of resurrection after death), Ḥimyar’s Judaism seems to differ from that of rabbis. Five inscriptions conclude with petitions concerning the end of their authors’ lives. And yet none of them mention resurrection.

In one text, certain nobles, who are otherwise unknown and who are commemorating the construction of their palace in Ḥimyar’s capital, conclude their inscription with the following invocation (Garb Nuove icrizioni 4, Bayt al-Ashwal [Ẓafār]):

...b-(7)rdʾ rḥmnn bʿl s1myn l-ẖmr-(8)hmw qdmm w-ʿḏ(r)m ks3ḥ(m ʾ)mn

With the help of Raḥmānān, owner of the Sky, so that He may grant (8) a pure beginning and a pure end, amen

The authors ask God to guard their lives on Earth, particularly their end, but they ask for nothing in the afterlife, which leads to the thought that they do not believe in an existence after death. The same conclusion can be drawn from two other documents cited above. The first of these commemorates the construction of a mikrāb by a princely family of the region of Ṣanʿāʾ. The prince provides detailed reasons for his patronage (Ry 520, from the vicinity of Ṣanʿāʾ):

...l-ẖmr-hw w-ʾḥs1kt-(6)hw w-wld-hw rḥmnn ḥyy ḥyw ṣdqm w-(7)mwt mwt ṣdqm w-l-ẖmr-hw rḥmnn wld(8)m ṣlḥm s1bʾm l-s1m-rḥmnn

In order that Raḥmānān may grant him, as well as to his wi(6)fe and his children, to live a just life and to (7) die a just death, and that Raḥmānān may grant him virtuous childre(8)n in the service for the name of Raḥmānān85

The second document’s author was a Jew called Yehuda Yakkuf, already mentioned, who appears to not have been from Ḥimyar. He commemorates the construction of a palace in the capital. In his invocations, Yehuda seeks to give details on the main traits of his God (Garb Bayt al-Ashwal 1 [Ẓafār]):

...b-rdʾ w-b-zkt mrʾ-hw ḏ-brʾ nfs1-hw mrʾ ḥyn w-mwtn mrʾ s1(3)myn w-ʾrḍn ḏ-brʾ klm

With the assistance and grace of his Lord who has created him, the Lord of life and death, the Lord of the S(3)ky and the Earth, who has created all86

Once more, the afterlife is not mentioned. This is, no doubt, an argument from silence, but it cannot be dismissed since, in principle, the afterlife is a constant preoccupation of those who believe in it.

A third document is more ambiguous. It is a bilingual grave stele, of unknown provenance, written in Aramaic and Sabaic. The fact that the Jewish-Aramaic text is written first (before the one in Sabaic carved underneath) suggests that the stele comes from a Jewish necropolis of the Near East and not from Yemen.87 The document is ambiguous, because the first text explicitly mentions resurrection, while the second one does not (Naveh-Epitaph of Leah):

...nšmt-h l-ḥyy ʿwlm (3) w-tnwḥ w-tʿmwd l-gwrl ḥyym lqṣ (4) h-ymyn ʾmn w-ʾmn šlwm

May her soul (rest) for eternal life, (3) and it will rest and become [ready] for resurrection at the en(4)d of days. Amen and amen, shalom

...l-nḥn-hw rḥmnn (7) ʾmn s1lwm

May Raḥmānān grant her rest. Amen, shalom

Among the various scenarios that one could contrive to explain this difference in formulation, the most likely is that the stonecutter was content to copy the standard formulae on hand or those provided by Leah’s family. This could mean that Ḥimyarite Jews did not believe in an afterlife (or were not in the habit of mentioning it in their grave inscriptions), while the Jews of the Levant did believe in it. We cannot dismiss that one of the two formulae was written or chosen by Leah’s family, but if one accepts such a hypothesis, nothing allows favouring one version over the other.

One must set aside the Aramaic grave stele in the name of Yoseh son of Awfà, which has already been mentioned (Naveh-Epitaph of Yoseh = Naveh-Ṣuʿar 24):

...ttnyḥ nfšh d-ywsh br (2) ʾwfy d-gz b-ṭfr mdynth (3) b-ʾrʿhwn d-ḥmyrʾy w-nfq (4) l-ʾrʿh d-yśrʾl

May the soul of Yoseh son (2) of Awfà, who passed away in the city of Ṭafar (3) in the Land of the Ḥimyarites and left (4) for the Land of Israel, rest in peace88

The deceased passed away in the Land of the Ḥimyarites, yet nothing certifies that he is himself a Ḥimyarite. At most one notes that he bears an Arab patronym. Noteworthy, however, is the fact that no allusion is made to resurrection.

The fifth inscription, Ja 547 + 546 + 544 + 545 = Sadd Ma ʾrib 6 (Ma ʾrib, November 558 CE, dhu-muhlatān 668), mentioned above, also poses problems of interpretation. Dating from the reign of the Christian king Abraha, it can be considered Christian; in fact, a small cross is carved at the end of lines 10, 13, and 14. One suspects that the authors introduced themselves as Christians without really belonging to the faith. The crosses are very discreet and placed in such manner that they can be thought of as letters. Moreover, the invocations to God make no reference to the Holy Trinity (“In the name of Raḥmānān, Lord of the Sky and the Earth” [w-ʿl-s1m rḥmnn mrʾ s1my(n) w-ʾrḍ(8)n] and “In the name of Raḥmānān, the King” [ʿl-s1m rḥmnn mlkn], line 10). Finally, the authors come from a commune very strongly marked by Judaism. The text ends with the petition:

...l-ẖmr-hmw ḥywm ks3ḥm (14) w-mrḍytm l-rḥmnn (cross)

May [Raḥmānān] grant them a life of dignity (14) and the satisfaction of Raḥmānān

Once more, life after death is omitted. If the authors are Jews rather than Christians, this silence is not surprising. If the authors are true Christians, however, this could mean that the afterlife is not a topic that one mentions in inscriptions, whatever one’s religious orientation.89

In short, all the texts available seem to show that the afterlife was not a matter of concern for Ḥimyarite Jews, who probably did not believe in the resurrection of the dead. According to the Mishnah, those who denied resurrection belong to the three groups excluded from the world to come: “[Here are] those who have no part in the world to come: the one who says there is no resurrection of the dead, [the one who says] that the Torah does not come from heaven, and the Epicurean” (m. Sanh. 10.1).90 According to the rabbis, the most severe punishment in the world to come will be meted to:

Those belonging to sects (minim), apostates (meshummadim), traitors (mesorot), Epicureans, those who have denied [the divine origin of] the Torah, who have gone astray from the community’s ways, who have doubted the resurrection of the dead, who have sinned and have made the community (ha-rabbim) sin like Jeroboam, Ahab, and those who established a reign of terror over the land of the living and have extended their hand over the House [i.e., the Temple] (t. Sanh. 13.5).

This is therefore a first clue that Ḥimyar’s Judaism was not rabbinic. On this matter, it should be recalled that one of the main reasons Muḥammad, the founder of Islam, reproached his opponents was their disbelief in Judgment Day and in the resurrection. One supposes that these opponents were followers of the old religion of Makka; the example of the Jews of Ḥimyar, however, shows that his opponents were plausibly followers of other religious currents. After Arabia’s conversion to Islam, the change was immediate: in the oldest Islamic inscriptions in Arabic, the author frequently “demands paradise”.

A second point of doctrine that would distinguish Ḥimyar’s Judaism from that of the rabbis is the issue of ‘binitarianism’. This is more problematic, because it mainly rests on a single inscription of somewhat enigmatic meaning (CIH 543 = ẒM 772 A + B, Ẓafār):

[b]rk w-tbrk s1m rḥmnn ḏ-b-s1myn w-ys3rʾl w-(2)ʾlh-hmw rb-yhd ḏ-hrdʾ ʿbd-hmw s2hrm w-(3)ʾm-hw bdm w-ḥs2kt-hw s2ms1m w-ʾl(4)wd-hmy ḍmm w-ʾbs2ʿr w-mṣr(5)m...

[May it bl]ess and be blessed, the name of Raḥmānān, who is in the Sky, Israel and (2) their God,91 the Lord of the Jews, who has helped their servant Shahrum,(3) his mother Bdm, his wife Shamsum, their chil(4)dren [from them both] Ḍmm, ʾbs2ʿr and Mṣr(5)m...92

The blessing in the introduction associates God (“Raḥmānān, who is in the Sky”) with Israel and the Lord of the Jews (two divine entities and Israel). It is legitimate to ask whether one finds here an instance of deviance denounced by the rabbis, the one that states there are “two powers in heaven”.93

This blessing is, therefore, a call to question the relationship between Raḥmānān and the “Lord of the Jews”, who is found in two other invocations:

rb-hd b-mḥmd

Lord of the Jews, with the Praised One (Ja 1028 / 12, Ḥimà, Fig. 7 )94

rb-hwd b-rḥmnn

Lord of the Jews, with Raḥmānān (Ry 515, Ḥimà)95

One should first of all notice that the authors of these three texts, who use the title ‘Lord of the Jews’ (Rabb-Yahūd, written rb-yhd, rb-hd, and rb-hwd),96 are proven or plausible Ḥimyarites, successively invoking the deity under two different names, as if dealing with two gods: the ‘Lord of the Jews’ and Raḥmānān or the ‘Lord of the Jews’ and Mḥmd. It is quite unlikely that a title like ‘Lord of the Jews’ would be used by Jews of Judaean ancestry, since they prefer the self-designation ‘Israel’ to Yahūd. The term ‘Jew’ is above all used by Gentiles; when Jews use it, it is in exchanges with people outside the community.

Incidentally, the term Mḥmd given to God is intriguing. It perhaps echoes a text invoking “Raḥmānān and Ḥmd-Rḥb” since, in the second name (unfortunately, also enigmatic), one finds the same root ḤMD.97 The spelling of the deity’s name Mḥmd seems identical to that of Islam’s prophet. One cannot be sure this identity is significant because the vocalization of these two names may differ (for example, Maḥmūd and Muḥammad). We know that some reformers were nicknamed after the deity they claimed to worship; this could also have been the case with Muḥammad (whom the Qurʾān also calls Aḥmad).98

A second observation is that the name ‘Lord of the Jews’ probably refers to the Jewish Adonai, reflected from the outside. The ‘Lord of the Jews’ would therefore be YHWH, the God of the Hebrew Bible, the God who dictated the Law to Moses.

If Raḥmānān is different from the ‘Lord of the Jews’, the first could be the God of those not considered fully Jewish, i.e., the ‘candidates’ who aspire to become Jews and the ‘sympathizers’.99 Or, more doubtfully, the first could be the God of converts—or proselytes—as opposed to the God of Jews of Judaean origin.

To identify which current of ancient Judaism was practiced in Ḥimyar, we can once more draw attention to the fact that some traits are shared by various kinds of Judaism of the Mediterranean world, while others are not. Ḥimyar’s Judaism, like other forms of Judaism in the Mediterranean world, uses the local language and script but not Hebrew, which is strictly confined to symbolic texts.100 By contrast, Ḥimyar lacks the menorah and other symbols found in the synagogues of Galilee and elsewhere in the Mediterranean world.101

Another singular trait of Ḥimyar’s Judaism is the famous list of mishmarot (or ‘guards’) of Bayt Ḥāḍir, mentioned above.102 It enumerates the twenty-four families of the priesthood in charge of the divine service in the Temple of Jerusalem following the Babylonian Exile, and it associates these family names with residences in Galilee. The fact that it originates from social backgrounds vouching for the Temple’s restoration is not doubtful; just as secure is the fact that its function was to legitimate the priestly pretentions of lineages then settled in Galilee. Yemen is the only country outside of Palestine where such a list was carved in stone. This is not banal, since the making of such a beautiful inscription was very expensive.

We can only hypothesize as to why such a document was copied and carved in Yemen. It may have had symbolic meaning, like the public statement of an indefectible attachment to the Temple, or the claim that only priests are legitimate to manage the community. It could have also been propaganda benefitting families of the priesthood who were effectively present in Yemen. The list of the Bayt Ḥāḍir mishmarot, which is not explicitly dated, certainly goes back to a time when the power stakes were high; it is therefore very likely that it is from the period 380–530 CE.

Finally, Ḥimyar’s Jews transcribe proper nouns according to Biblical Hebrew (and not according to later texts, notably in Aramaic). The impression is that one is dealing with a conservative form of Judaism, attached not only to the Temple but also to a literal interpretation of the Holy Scriptures. Since Ḥimyarite Jews, like the Sadducees (the priestly party at the end of the Second Temple period), apparently rejected belief in the resurrection, one has good grounds to characterize Ḥimyar’s Judaism as ‘priestly’, all the more so since nothing recalls rabbinic Judaism.

The case of Yathrib—the future al-Madīna—in the seventh century is entirely different. Haggai Mazuz has recently demonstrated in quite convincing fashion that the Judaism of the Yathrib Jews had much in common with that of the rabbis.103 One could therefore surmise the existence of different orientations in South Arabia and the Peninsula’s northwest. Due to the difference in dates, however, this is not the most likely hypothesis.