9. Rabbis in Southern Italian Jewish Inscriptions from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages

© Giancarlo Lacerenza, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0219.09

1.0. Premise

Many questions inherent in the wide catalogue of the so-called epigraphical rabbis in the ancient Mediterranean were already been directly posed more than thirty years ago in an important article by Shaye J. D. Cohen. The very same questions have more recently been reconsidered by Hayim Lapin, building on Cohen’s work, within the framework of a debate that has interested a number of scholars for many years.1

In the following pages, I shall not reopen the discussion of earlier conclusions, which are presumed to be well-known to all specialists. Our goal, starting from the preliminary conclusions drawn up by Cohen and Lapin, shall be to focus more closely on the epigraphs of southern Italy where, more than in any other place, the epigraphic evidence shows how, between the fifth and ninth centuries, the title rabbi gradually lost its vagueness and became connected, at least in official (funerary) epigraphs, only with people arguably related to rabbinic Judaism.

2.0. The Rome Anomaly

In the list of epigraphical rabbis drawn up by Cohen, limited to the period between the third and seventh centuries CE, there can be found just five inscriptions covering the Mediterranean, from the Aegean area to the Iberian Peninsula. Among them, one text belongs to Cyprus (Lapethos/Karavas), one to North Africa (Volubilis), one to Spain (Emerita), and two to southern Italy (Naples and Venosa). Lapin’s list, slightly more precise, rightly includes in the same entry not only the Western Diaspora, but also the Eastern and collects as a whole a total of ten inscriptions (double Cohen’s tally). The tituli for southern Italy increase from two to three (Naples, Venosa, Brusciano). An increase to two is also recorded in the case of North Africa (a text from Cyrenaica has been added), while counts of one each persist for Cyprus and Spain (but from Tortosa; indeed, the example from Emerita given by Cohen is excluded as too late). Finally, there is one record in Egypt (a papyrus of unknown provenance); one in Syria (Nawa); and one in Mesopotamia (from Borsippa, on a magic bowl).2

In the map resulting from these place-names, it appears that, in the period considered, it is southern Italy—more precisely, the Regio Prima et Secunda—which holds the greatest number of attestations. This fact may well be, of course, totally insignificant in itself: following new discoveries, the picture could be completely different in ten years’ time, and so it is better not to attribute any particular significance to this circumstance. On the other hand, we can only speculate on the data we have at our disposal and, among these, there is also a negative circumstance, which is worthy of reflection.

In southern Italy alone, about two-hundred Judaic inscriptions have been found. Among these, as we have seen above, three attestations of rabbi/rebbi have been found. In the Jewish catacombs of Rome, which have yielded no fewer than six-hundred epigraphs, no such attestations are extant. Indeed, as already stressed by Cohen, in this vast assemblage of inscriptions, there are “references to archisynagogues, archons, gerousiarchs, grammateis, patres synagogae, matres synagogae, exarchons, hyperetai, phrontistai, prostatai, priests, teachers, and students, but not one with a reference to a rabbi.”3

Hundreds of inscriptions are found in a homogeneous context and over a period of several centuries, by no means an insignificant sample. This circumstance, however, does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that in Ancient and Late Antique Rome there were no rabbis. If we look at the epigraphs as bearers of archaeological indications (positive or negative) and not only textual ones, it can be suggested that, for example, in the Eternal City, rabbis—if some people there were designated in this way as bearers of a rabbinic title—were not buried in this type of common sepulchral structure, but were buried elsewhere.

The rabbi Mattiah ben Heresh, the founder of a school, lived in second-century Rome. We do not have his epitaph, but various sources deal with his teaching both in Judaea and in Rome.4 As for the subsequent period, considering the eleven or more different synagogues attested by the Judaic inscriptions of Rome, each bearing a specific designation and possibly suggesting the existence of a plurality of Judaisms practiced there, we should admit that, at least as a realistic possibility, rabbinic Judaism was also represented there.5 Moreover, the existence of a quarrel between the Palestinian Sages and the Diaspora religious leaders already in the first century CE can be inferred from the rabbinic criticism of the main Roman Jewish authority, Theudas/Thodos or Theodosius, for a Passover custom not in agreement with that of the Land of Israel. According to the sources dealing with this Theudas, it appears that he was a wealthy man and, at the same time, a renowned scholar: an outstanding personality, whose authority in religious matters relied on something we are not able to discern.6 A couple of centuries later, a certain Mnaseas, who was buried in Rome in a sumptuous marble sarcophagus, possibly held a similar position. In his Greek epitaph, he flaunted his high status within his Jewish community, both in the social scale, as pater synagogion ‘father of the synagogues’ (with a significant plural form) and also, and rather surprisingly, as mathetes sofon ‘student of the Sages’.7 This latter is a precise calque of the Hebrew title talmid hakhamim and, perhaps, this qualification was intended to stress his alleged proximity to members of the rabbinic movement.

A similar title, nomodidaskalos ‘teacher of the Law’, appears just once in Rome, in Vigna Randanini.8 Unfortunately, while a rabbi might be, among other things, a nomodidaskalos, it is impossible to postulate a rabbi behind every teacher of the Law: this explains why the term is still controversial, even considering that, in the New Testament, nomodidaskalos almost always appears in connection with the Pharisees (e.g., Luke 5.17; Acts 5.34; but not in 1 Tim. 1.7).9 It could be added that nomodidaskalos is an equivalent to the Latin doctor legis (or legis doctor, as in the Vulgate rendition of Acts).10 The use of nomodidaskalos seems, at any rate, somewhat more specific than the more common adjective nomomathes ‘student of the Law’, found on three epitaphs from, once again, the catacombs of Vigna Randanini and in a funerary inscription from Monteverde, where the term was apparently used to praise the deceased’s skill in letters or his knowledge of the Law in general.11

In summary, while the existence of rabbinic contacts between Galilee/Palestine and the Jewish communities of Rome (as well as a rabbinic presence in Rome) can be taken for granted, the anomaly of the absence of the title rabbi in the epigraphs remains.

3.0. Campania Felix

The area of the Regio I once called Campania, is the one Italic region where the Jewish presence is attested epigraphically before Rome itself. Rather than the dubious testimony from Pompeii, the evidence comes from ancient Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) and its territory. In a funerary area along the road to Naples, the epitaph of Claudia Aster, Hierosolymitana captiva ‘prisoner from Jerusalem’, was found, dating back to the last quarter of first century CE.12 It is the same period in which the above-mentioned R. Mattiah ben Heresh is said to have spent some time in Puteoli, before establishing himself in Rome (Sifre Deut. 80). Up to the fourth/fifth centuries, Jewish attestations in Campania are limited to scarce epigraphs and various literary sources. Later on, they grew in number—not, however, around the ports, but rather in areas protected from Vandal incursions: well-fortified areas such as Naples or inland places such as Fondi, Terracina, Minturno, Capua, Benevento, and Nola. Here, economies were based not on trade but rather on large-scale agricultural production, in a network of rustic villas and farms scattered over a wide territory, characterized by just a few urban centres with a relatively high population density.

3.1. The Epitaph of Rebbi Abba Maris

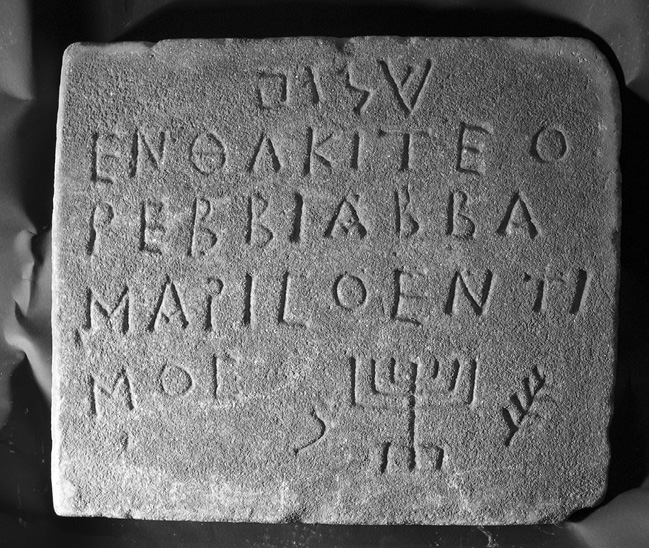

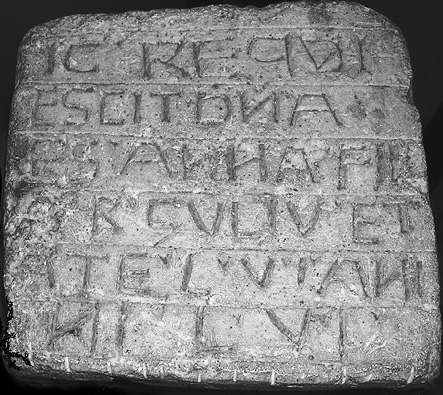

The first epigraphical attestation of rabbi (here spelled, as elsewhere, rebbi) emerges from such a context, in the agricultural area surrounding Nola. It is the Greek epitaph of Abba Maris (Fig. 1), which runs as follows:

שלום ἔνϑα κῖτε ὁ ῥεββὶ Ἀββᾶ Μάρις ὁ ἔντιμος

Shalom! Here lies the rebbi Abba Maris, the revered one

Fig. 1: Epitaph of Rebbi Abba Maris (Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Photograph by Giancarlo Lacerenza. © All rights reserved.

In its concision, the epitaph is quite noteworthy, and in modern syntax we should read: “Shalom! Here lies the revered rebbi Abba Maris.” The epitaph was found in Brusciano and, being written in Greek, it dates, like other inscriptions in the area, to no later than the fourth century. The inscription is a completely isolated finding in Brusciano, and it seems likely that it originates from the nearby territory of Nola, an important Roman city, where, however, the use of Greek in epigraphs was rather rare.13 It probably belonged to an extra-urban burial area, probably exclusively Jewish, as also suggested by the notable distance of Brusciano from the city (c. 10 km). This recalls the similar collocation of the catacombs of Venosa, well outside the town centre (c. 2 km), and the suburban location of the unique Jewish burial site in Naples, far from the centre and even from the most frequented burial places around the city (on which, see below). Finally, the titulus of Abba Maris falls in a district, though rural, with other attestations of Jewish presence, both literary and archaeological. Not far from there, near the ancient town of Nuceria, two other Jewish funerary inscriptions have been found and, again, both in Greek: one belonging to a certain Pedonius, who is called a scribe (grammateus), the other one to his wife, Myrina, who holds the title of priestess, presbytera.14 As is known, various hypotheses have been expressed about the meaning of these as well as other terms. My intuition is that they should be accepted literally but, unfortunately, I cannot deal with such a question here.

The title rebbi in the epitaph of Abba Maris has until now been considered merely an appellative, i.e., an honorary title, not indicative of a real function (so Cohen and Lapin). On this point I have some doubts. The distinction between appellative and noun cannot be established through reference to the placement of the term rebbi. Examining the list of attestations of epigraphical rabbis in the Diaspora, in practice the term rebbi has been understood as an honorific whenever it precedes a name or patronym, as for example in Benus filia rebbitis Abundanti from Naples (on which see more details below). Also, when the title follows the name, it was considered an appellative, as in the funerary inscription on a fourth century sarcophagus from Nawa (Syria) where it is written simply Ἀρβιάδες ὁ ῥαββί ‘Arbiades the rabbi’, with the definite article, which also appears in the inscription of Abba Maris.15 In isolated cases, most of which lack anthroponyms, rabbi/rebbi was considered a noun and an actual rabbinic title.

The expression ὁ ἔντιμος, unique in this type of documentation, seems to indicate public rather than private recognition,16 but we do not know the precise meaning the writers of the epigraph, relatives or disciples of Abba Maris, intended. Should they have had the liturgical (biblical) vocabulary in mind, ἔντιμος in the Septuagint usually indicates a person held in special consideration, esteemed by his people. Indeed, it is by no means rare to find ἔντιμος translating Hebrew yaqar (e.g., 1 Sam. 26.21; Isa. 13.12; 43.4). In this case, however, a private connotation of the adjective cannot be excluded and then it would not be inappropriate to translate ἔντιμος as ‘revered’ or even ‘dear, beloved’, very appropriate in a funerary context and semantically connected with ‘precious’.17 The final point to consider is Abba Maris’s name. In western Jewish inscriptions it appears only here. In general terms, Jewish or Semitic anthroponyms in this kind of document are rare. In some contexts, they are simply non-existent, demonstrating a clear preference for Greek and, to a lesser extent, Latin names. The name Abba Maris can be explained by admitting that its bearer came from abroad, arguably from Palestine.18

3.2. The Epitaphs of Binyamin from Caesarea and Venus, Daughter of Rebbi Abundantius

Besides the instance of R. Abba Maris, there is additional evidence that at least some of the Jewish elite of Late Antique Campania came from abroad, from both Palestine and also North Africa. This emerges from a small collection of Jewish funerary epigraphs found at the beginning of the twentieth century in Naples, in an ancient burial area outside the city (presently within its eastern suburbs).19

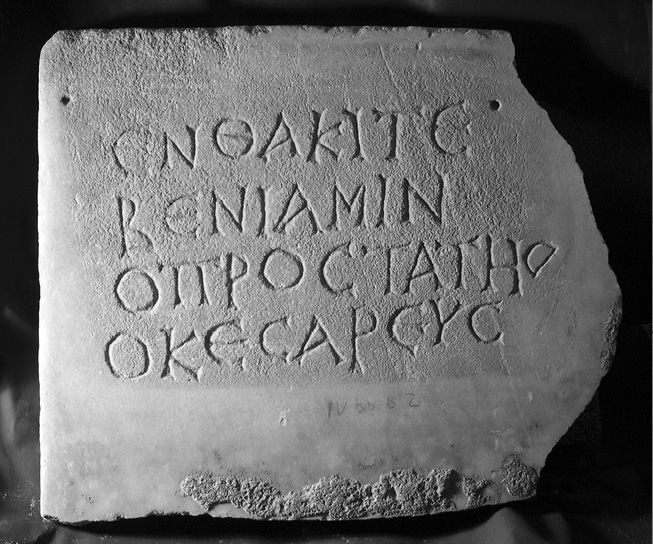

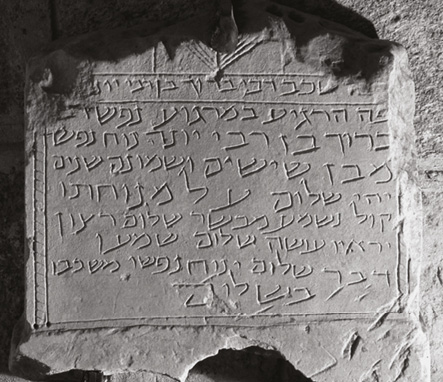

These inscriptions have no date, but it is reasonable to assume that they all belong to the same period, around the fifth or sixth century. The texts are all in Latin, with appearance and formulae similar to that of contemporary Christian epitaphs. Their Jewishness is marked by the addition of some typical epigraphic Hebrew expressions, such as שלום, שלום על מנוחתך, אמן, סלה. Moreover, three out of ten of the individuals mentioned in the epitaphs are qualified as Jews or, more precisely, as “Hebrews.” They are: Numerius, ebreus (JIWE I, no. 33); Criscentia, ebrea (JIWE I, no. 35); Flaes, ebreus (JIWE I, no. 37). Like all the deceased in this cemetery, the three bear Latin names. In the case of Numerius, his name is also transcribed in square Jewish characters. In this handful of Latin inscriptions commemorating both “Hebrews” and Jews,20 there is one that differs considerably from the others because it is the only one in Greek and the only one where the deceased individual bears a typically Jewish name, Binyamin (Fig. 2; JIWE I, no. 30). The text is very short, if not laconic, and reads:

ἔνϑα κῖτε Βενιαμὶν ὁ προστάτες ὁ Κεσαρεύς

Here lies Binyamin the prostates, the Caesarean.

Fig. 2: Epitaph of the prostates Binyamin (Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Photograph by Giancarlo Lacerenza. © All rights reserved.

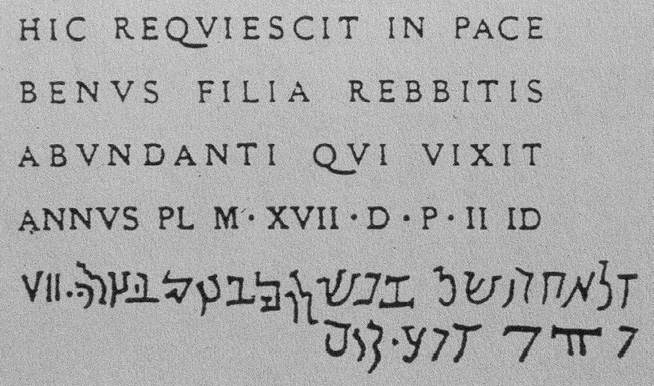

The only title present here is prostates, and it is possible that this refers to the head or president of the community. It has been suggested that the city of Caesarea mentioned here could be the one in Mauretania, because there is another inscription in the same cemetery where a civis Mauritaniae (JIWE I, no. 31) is commemorated; however, for various reasons—not least of all the use of Greek—I am more inclined to see here Caesarea Maritima.21 Among these inscriptions the title rabbi does not appear, but it is possible, if not probable, that another epitaph mentioning a rebbi, found long before the other epigraphs, pertains to the same burial area. It is the Latin epitaph of a young girl, Venus (spelled Benus, with betacism), daughter of a rebbi Abundantius (Fig. 3; JIWE I, no. 36):22

Hic requiescit in pace Benus filia rebbitis Abundanti qu<a> vixit annis pl(us) m(inus) XVII d(e)p(osita) II Id(us) Iun(ias)

Here lies in peace Venus, daughter of rebbi Abundantius, who lived about seventeen years. Buried on the 12th day of June.

Fig. 3: Epitaph of Venus, daughter of Rabbi Abundantius (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X 3303). Public Domain.

There are also two lines in Hebrew following the Latin text, difficult to reconstruct precisely from the old apographs. It is probably just an abridgment of the main text and it is perhaps to be read:

הנה תשכב בשלום בנוס בנוחה / יהי <ה>שלום

Here lies in peace Venus. In her repose / be peace.

The rebbi mentioned in this inscription (the term in this case is the singular genitive rebbitis) has been considered solely as an appellative based on the doubtful criteria mentioned above. The name does not help much, since Abundantius (probably the form behind the genitive Abundanti) is common in Christian contexts, but not at all in Jewish inscriptions. Maybe our rebbi converted his original name to a Latin form: if the name was Yosef, an adjective or a predicate related to ‘addition’ appears to be a good choice. As an aside, the coincidence between the adjective abundans—whose Greek equivalent is πολὺς or περισσόν—and the Hebrew rav is noteworthy.23 The name Abundantius and the presumed title rebbi are, in this perspective, substantially equivalent, but it would be hazardous to venture further.24 Finally, the name of the deceased daughter, Venus, is of interest. Although apparently pagan, it is also an ancient adaptation of the name Esther, through its more common Greek equivalent Ἀστήρ.25

3.3. Evidence of Synagogues and Jewish Liturgies in Late Antique Naples

As we have seen, the search for rabbis among the Jews of southern Italy has mainly led to some attestations in funerary epitaphs. These are not, however, the only ones that provide direct information on the religious life of the Jewish communities in the south, particularly in Naples.

Thanks to Procopius of Caesarea, we know that in the first decades of the sixth century the Neapolitan Jewish community was demographically strong and politically influential. They had an important economic role and were able to guarantee provisions to the city during sieges. This is exactly what happened in May 536, when the Byzantine army came to take the city from the Goths. The Jews played an important role on the eve of the Byzantine victory: Procopius writes that when the town authorities met to decide if the city should surrender immediately to the imperial army or resist and support the Goths, it was the Jewish community that tipped the scales in favour of resistance. Thereafter, the Jews guaranteed grain supplies to the city during the siege and offered to man the most dangerous stretch of the walls, the one facing the sea.26 As was demonstrated elsewhere, this is probably the same area where their main synagogue was situated.27 For some decades after this, no further information is available, but at the beginning of the seventh century, the letters of Pope Gregory the Great (591–604) again shed light on the Jews of Naples. In spite of the feared Byzantine domination, the community still had members who were active in foreign trade, especially in the importation of slaves, whom they purchased from merchants in Gaul.28

Among the various references in the epistles of Gregory to the Neapolitan Jews—who, in that period, appear to have already suffered from pressure to convert—it is worth mentioning Gregory’s last letter, from November 602, also known as Qui sincera. Unlike the numerous occasions of conflict between Jews and Christians mentioned in the letters, in this case it was the Neapolitan Jews themselves who turned to the pope, complaining that several citizens, encouraged by Paschasius, the bishop of Naples, regularly interrupted Jewish rites observed during the Christian holidays, sometimes violently. Unexpectedly, Gregory intervened in defence of the Jews, and he wrote directly to the bishop to remind him that for a long time (longis retro temporibus) Neapolitan Jews had been granted the right to observe their religious holidays (quibusdam feriarum suarum sollemnibus) even on Christian feast days.29

Who had guaranteed until then, indeed, “for a very long time,” the regular observance of synagogue services in Naples? The letters of Pope Gregory give no answer but, at the very least, their contents lead us to reject a recurrent commonplace, namely, that the Jewish communities at that time in this part of southern Italy were isolated. We know from these letters and various other sources that they were in continual contact—commercial, social, and cultural contact—with the whole of the Mediterranean, from Marseilles to the Balkans, Syria, and Egypt.

4.0. The Epitaph of Faustina: Apostuli and Rebbites in Sixth-Century Venosa

To avoid excessively broadening this survey, I shall not extend it into the Calabria and Puglia regions, but limit my observations to a single location: the city of Venosa, a town with a high concentration of Jews, at least from Late Antiquity onwards, who perhaps flourished in connection with the spread of local textile manufacturing.30 Venosa is known for its Jewish catacombs, which stood next to the Christian catacombs. At the time of their discovery, the tombs were still undisturbed, and there were probably hundreds of epitaphs, but only seventy have reached us, painted or scratched on the plaster sealing the tombs (JIWE I, nos. 42–112). The inscriptions are dated from the third/fourth centuries onward. The last epitaphs probably do not go beyond the sixth century, as indicated by the epitaph of Augusta, the only text with a certain date, from the year 521 (JIWE I, no. 107).

Epitaphs show that the Venosian Jews were well-integrated into local society, and some of them even enjoyed high social status. The Jews also had a degree of religious influence on local society, as indicated by the burials of proselytes in a separate cemetery, not far from the catacombs, the so-called “Lauridia hypogeum” (JIWE I, nos. 113–16). The titular functions attested at Venosa are the same as in Rome and elsewhere in the West, and the community included presbyters, gerusiarchs, archisynagogoi, and patres synagogae. It seems that also the Venosian Jews preferred non-specifically Jewish names, with some notable exceptions, as in the bilingual (Greek-Hebrew) epitaph remembering a teacher called Jacob (Iakob didaskalos; JIWE I, no. 48).

Besides teachers, scribes, and other people connected with communal duties, two rabbis appear in the particularly long Latin epitaph of Faustina, the young daughter of Faustinus: duo apostuli et duo rebbites ‘two apostles and two rabbis’ are portrayed as reciting dirges for the deceased girl. The text (Fig. 4; JIWE I, no. 86) runs as follows:

Hic cisqued Faustina filia Faustini pat(ris), annorum quattuordeci<m>, mηnsurum quinque, que fuet unica pare[n]turum. Quei dixerunt trηnus duo apostuli e[t] duo rebbites. Et satis grande(m) dolurem fecet parentebus, et lagremas cibitati(s).

משכ<ב>ה ש[ל] פווסטינה נוח נפש שלום

Que fuet pronepus Faustini pat(ris), nepus Biti et Acelli, qui fuerunt maiures cibitatis.

‘Here rests Faustina daughter of Faustinus, father (of the community), aged fourteen (years and) five months, who was her parents’ only child. Two apostles and two rabbis said the dirges for her, and she had great grief from her parents and tears from the community.

[Hebrew:] Resting place of Faustina, may her soul rest, peace.31

She was the great-granddaughter of Faustinus, father (of the community), granddaughter of Vitus and Asellus, who were notables of the city.’

.jpg)

Fig. 4: Epitaph of Faustina, daughter of Faustinus (Venosa, Jewish Catacombs). Photograph by Cesare Colafemmina. The University of Naples “L’Orientale” Archive. © All rights reserved.

Written in a mixture of late Latin, Greek, and some Hebrew, this text has been the subject of many attempts at dating and interpretation, all instigated by the intriguing phrase duo apostuli et duo rebbites, known only in this inscription, which I shall return to later. Before continuing the analysis of the epitaph, I would like to discuss its context. The inscription, currently missing, was almost hidden in a small space between other tombs and epitaphs in a specific arcosolium (D7) within the catacomb. As foreseen already in the nineteenth century by Raffaele Garrucci, and then more recently demonstrated by Margaret H. Williams,32 this arcosolium belonged to members of a single family, the Faustinii, who also owned a second arcosolium (D2) nearby. In arcosolium D7 there are numerous tombs, some on the pavement and some on the walls; all were originally accompanied by an inscription, but most of the epitaphs have been lost over the course of various attempts to rob the loculi. Therefore, today we have a rather distorted picture of the original appearance of this burial place, which—like the whole catacomb—must have once been very different: with the walls covered in light stucco where the inscriptions would stand out, painted or finished in red, often accompanied by Hebrew terms and the symbol of the menorah. The Faustinii family was not an ordinary one. It is said of the two relatives mentioned in Faustina’s epitaph, Vitus and Asellus (or Asella), that they were maiores civitatis—a title which does not correspond to any specific public office known in the sources, but which denotes the high status enjoyed by the family a few generations prior to Faustina and so, presumably, in the Gothic period. In any case, there is no doubt that, at the beginning of the sixth century, the Jews in Venosa could have access to public office. In the above-mentioned epitaph of Augusta, from 521, the deceased woman is named as the wife of a certain Bonus, whose name is followed by the abbreviation for vir laudabilis: He belonged to the rank of decurions.33 Over time and, above all, with the transition to Byzantine domination, the Faustini family must have progressively suffered from a social point of view, probably accompanied by an economic decline. However, it does not seem that it lost its prestige within the Jewish sphere, if young Faustina’s funeral was accompanied by a following that has no parallel in any other inscription, whether in Venosa or elsewhere.

The declared participation of two “apostles” and two rabbis at the girl’s funeral can be read in several ways. There is no other testimony for comparison or other sources, so these are, of course, hypotheses. First of all, since the presence of four officiates for the funerary dirges does not correspond to any ritual need, it seems evident that this was perhaps a show of public importance—not for the girl herself, but for her family—even if the days of its greatest splendour had passed.34 On the other hand, parallel to this general decline one can trace a growing awareness of cultural Jewishness, if the increasing use of Hebrew exhibited in the catacomb can be used as an indicator. This evolution has been also recognized in the two arcosolia of the Faustinii, where Williams has revealed a progressive change in the composition of the epitaphs: first, an early phase, with very simple epitaphs in Greek, then an increasing use of Latin, with self-identifying symbols, such as the menorah and, progressively, the use of Hebrew. This passes from the simple use of the word shalom to more elaborate texts (see JIWE I, nos. 80–82a, 84). Such a cultural ‘Hebraization’ of these prestigious Jews of Venosa in the mid-sixth century implies a small, though not secondary, cultural revolution. It is reasonable to assume that this development came from outside.

I would like to return to the four guests at Faustina’s funeral. The whole passage mentioning them is unique in shape and content, considering the general economy not only of the epitaph in question, but of all the tituli in the catacomb of Venosa. This fact alone indicates the exceptional nature of the event, and it is clear that the presence of four officiates at a funeral was by no means a daily occurrence. It is undisputed that the rebbites were rabbis, but rabbis from where? Probably from elsewhere, and this impression is reinforced by the presence of the two “apostles,” whose identification has always been problematic. Many scholars identified them as envoys of the Palestinian patriarchate in Italy who were passing by Venosa at the time of Faustina’s death. The patriarchate was abolished within the first half of the fifth century, and the text appears to be later (in my opinion, it is not earlier than the second half of the sixth century). Trying to resolve this incongruity, I once proposed that the term apostuli here could refer simply to representatives of the local assembly (שליחי ציבור).35 I am no longer convinced by this hypothesis, and I am inclined to consider the apostuli to be strangers no less than the rebbites. The fact that they were emissaries from outside and not members of the local community is indicated, as well, by the very use of the term apostuli or rather apostoli: this calque from the Greek ἀπόστολοι appears in late and medieval Latin directly from the Vulgate, while its epigraphic use is recorded only in this case. Semantically speaking, it is hard to think that the term was not used for emissaries originating from elsewhere: Byzantium? Palestine? Mesopotamia?

Finally, it can be no coincidence that Faustina’s epitaph, which records the presence of rabbis and apostles in southern Italy in the mid-sixth century, falls precisely within the period of dispute regarding Greek and Hebrew in the synagogue liturgy, over which the Jewish communities in both the East and the West would split, and indeed someone would decide—most inopportunely—to turn to the emperor to resolve the question. This led, as is known, to the promulgation of the famous Novella 146 in 553, whereby Hebrew was allowed in the synagogues on condition that the officiates did not profit from the occasion to alter the text. It is not without significance that, according to the prologus, Justinian issued the Novella as a response to petitions by Jews and not by the praefectus Areobindus, the formal recipient of the text. On the meaning and objectives of the Novella, there are already various and authoritative analyses.36 Nevertheless, it has perhaps not been sufficiently stressed that rabbis as such are not mentioned at all. The only Jewish authorities who could commute punishments or issue anathema, according to the text, are the archipherecita, the presbyterus, and the magister.37 The reason why the legislator ignored rabbis can be understood in various ways;38 but it may also be a strong argumentum ex silentio that the representatives of the rabbinic movement were not considered, at least in that period, interlocutors with the imperial power.

5.0. Emerging Rabbis: From Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages

The examination of the above-mentioned inscriptions seems to support the impression that, although we cannot prove that these rebbites were actually in possession of a rabbinic title (whatever this would imply in that period), it must be accepted that, as suggested by Fergus Millar, these texts confirm the importance of the study of the Law, the gradual revival of Hebrew, and the coming into currency of the term rabbi—or rather rebbi, now treated as a declinable Latin word with both genitive (rebbitis) and plural (rebbites) forms.39

After the last inscriptions in the Venosa catacombs, there is a gap of nearly two centuries. When Jewish dated texts reappear in Venosa at the beginning of the ninth century, they are no longer paintings or graffiti hidden underground, but epitaphs carefully carved on stones and fixed in the ground, en plein air. Most importantly, there are no longer any traces of Greek and Latin: Hebrew appears to be the only language. What happened in the meanwhile? This was, without any doubt, a significant cultural change that can be understood in several ways. Undoubtedly, the fact that the Jews in their inscriptions dropped the use of the common epigraphic languages, Latin and Greek, possibly indicates that they no longer wanted or needed to represent themselves as integrated into the surrounding social context: their cultural identity was felt to be irreversibly different. Who was responsible for this change? It would be tempting to say this happened thanks to a strong rabbinic presence or influence, which could well explain a funerary inscription such as that of Put ben Yovianu of Lavello (near Venosa; undated, possibly late eighth century), which is entirely in Hebrew, full of biblical and midrashic echoes, and following the taste of the times, in rhymed prose. Moreover, it contains the earliest quotations of the Babylonian Talmud (b. Ber. 17a and 58b)—or, at least, the first allusions to it—in the Latin West.40 This inscription, as well many others from Venosa, cannot be absolutely considered as standardized or formulaic.41 They are, among other things, clearly aligned with the poetic and literary productions of that time.

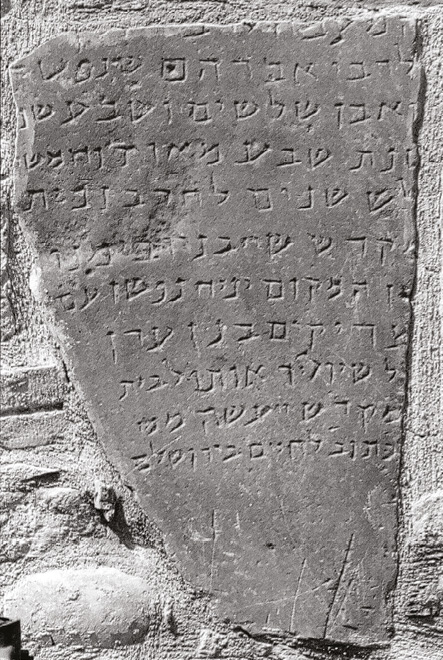

The growth of the rabbinic presence in southern Italy is perhaps supported by some epigraphs of the seventh to ninth centuries from Basilicata and Salento, where three tombstones of individuals bear the title rabbi. The most ancient is the bilingual epitaph of Anna, daughter of Rabbi Julius, in Latin and Hebrew (undated and probably belonging to the seventh century). The title rabbi appears abbreviated as R. in the Latin text; the Hebrew version of the epitaph is longer and rhymed, but it lacks the patronym (Fig. 5).42

Fig. 5: Memorial stone of Anna, daughter of Rabbi Julius (Oria, Biblioteca Comunale). Photograph by Giancarlo Lacerenza. © All rights reserved.

Then in Brindisi, not far from Oria, there is the epitaph of a certain Rabbi Barukh ben Rabbi Yonah, in Hebrew, undated but belonging to the first half of the ninth century (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Epitaph of Rabbi Barukh ben Rabbi Yonah (Brindisi, Museo Archeologico Provinciale). Photograph of the University of Naples “L’Orientale” Archive. © All rights reserved.

The second part of the epitaph includes a series of biblical verses (from Isa. 52.7; Nah. 2.1; Ps. 145.19; Job 25.2; Est. 10.3) also known from a Tziduk Hadin burial hymn written by Amittay of Oria (grandfather of the more celebrated paytan Amittay ben Shefatyah), and this hymn is still present in the ancient minhag bene Roma.43 Finally, back in Venosa, we find the epitaph of a certain Rabbi Abraham. It is also in Hebrew and bears a year, 821 or 822 (Fig. 7).44 The title rabbi appears four times in this epitaph. The renowned scholar and Italian rabbi, Umberto (Mosheh David) Cassuto, once wrote:

In later times [i.e., from the High Middle Ages onwards], it was common in Italy to call all men by the title ‘Rabbi’, as we say today ‘signore’. Here, however, since in this early period they did not preface the proper names of people with any descriptive title, it appears that the word ‘Rabbi’ is indeed descriptive of a Rabbi, in the sense of a scholar.45

Fig. 7: Epitaph of Rabbi Abraham (Venosa, Abbey of the Most Holy Trinity). Photograph by Giancarlo Lacerenza. © All rights reserved.

Regardless of this conclusion, a stable rabbinic presence in southern Italy can be detected from the tenth century onwards, if not earlier. The progressive rabbinization of Judaism in this territory can therefore be situated between the late sixth and the early ninth centuries. This process accompanied the dominance of Hebrew in every part of written culture, from funerary epigraphy to the emergence of a significant literary production in halakhah, hymnography, secular poetry, historiography, and medicine.46

Does this mean that the rabbis in the tenth century triumphed everywhere? On this point wisdom dictates caution. Besides the impact and consequences of the Karaite movement, the episode of Silano, a Venosian scholar, is suggestive. According to a tradition preserved in Megillat Ahimaʿaz (c. 1054) referenceing events that took place in the first half of the ninth century, Silano set a trap for an unnamed foreign rabbi during his visit to Venosa by changing the text of his synagogue homily. Consequently, Silano was excommunicated. He was later rehabilitated after changing a verse in another text to condemn the minim—probably the Karaites. If Silano was one of the last representatives of the traditions of southern Italian Jews,47 it seems that the price of his rehabilitation was the recognition of rabbinic Judaism as imported from the East.

Bibliography

Ameling, Walter, et al., Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae, Volume 3: South Coast, 2161–2648 (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2014), http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110337679.

Bradbury, Scott, ed., Severus of Minorca: Letter on the Conversion of the Jews (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996).

Cassuto, Moshe David (Umberto), ‘The Hebrew Inscriptions of Ninth-Century Venosa’, Qedem 2 (1945): 99–120. [Hebrew]

Cassuto, Umberto, ‘Nuove iscrizioni ebraiche di Venosa’, Archivio Storico per la Calabria e la Lucania 4 (1934): 1–9.

Chester, Andrew, ‘The Relevance of Jewish Inscriptions for New Testament Ethics’, in Early Christian Ethics in Interaction with Jewish and Greco-Roman Contexts, ed. by Jan Willem van Henten and Joseph Verheyden (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 107–45, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004242159_007.

Cohen, Shaye J. D., ‘Epigraphical Rabbis’, Jewish Quarterly Review 72 (1981): 1–17, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1454161.

Colafemmina, Cesare, ‘Iscrizioni ebraiche a Brindisi’, Brundisii res 5 (1973): 91–106.

———, ‘L’iscrizione brindisina di Baruch ben Yonah e Amittai da Oria’, Brundisii res 7 (1975): 295–300.

———, ‘Una nuova epigrafe ebraica altomedievale a Lavello’, Vetera Christianorum 29 (1992): 411–21.

———, ‘Hebrew Inscriptions of the Early Medieval Period in Southern Italy’, in The Jews of Italy: Memory and Identity, ed. by Barbara Garvin and Bernard Cooperman (Bethesda: University Press of Maryland, 2000), 10–26.

Collar, Anna, Religious Networks in the Roman Empire: The Spread of New Ideas (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781107338364.

Colorni, Vittore, ‘L’uso del greco nella liturgia del giudaismo ellenistico e la Novella 146 di Giustiniano’, in Judaica Minora: Saggi sulla storia dell’ebraismo italiano dall’antichità all’età moderna (Milan: Giuffrè, 1983), 1–66.

Conticello de’ Spagnolis, Maria, ‘Una testimonianza giudaica a Nuceria Alfaterna’, in Ercolano 1738–1988: 250 anni di ricerca archeologica. Atti del convegno internazionale, Ravello-Ercolano-Napoli-Pompei (30 ottobre–5 novembre 1988), ed. by Luisa Franchi dell’Orto (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1993), 243–52.

Ego, Beate, Targum scheni zu Ester: Übersetzung, Kommentar und theologische Deutung (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1996).

Frey, Jean-Baptiste, Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum, Volume 1: Europe (Vatican City: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1936).

Garrucci, Raffaele, ‘Cimitero ebraico di Venosa in Puglia’, Civiltà Cattolica 12 (1883): 707–20.

Grelle, Francesco, ‘Patroni ebrei in città tardoantiche’, in Epigrafia e territorio, politica e società: Temi di antichità romane, ed. by Mario Pani (Bari: Edipuglia, 1994), 139–58.

Horst, Pieter Willem van der, Ancient Jewish Epitaphs: An Introductory Survey of a Millennium of Jewish Funerary Epigraphy (300 BCE–700 CE) (Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1991).

Lacerenza, Giancarlo, ‘L’iscrizione di Claudia Aster Hierosolymitana’, in Biblica et semitica: Studi in memoria di Francesco Vattioni, ed. by Luigi Cagni (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 1999), 303–13.

———, ‘Ebraiche liturgie e peregrini apostuli nell’Italia bizantina’, in Una manna buona per Mantova: Studi in onore di Vittore Colorni per il suo 92° compleanno, ed. by Mauro Perani (Florence: L. S. Olschki, 2004), 61–72.

———, ‘La topografia storica delle giudecche di Napoli nei secoli X–XVI’, Materia Giudaica 11 (2006): 113–42.

———, ‘Attività ebraiche nella Napoli medievale: Un excursus’, in Tra storia e urbanistica: Colonie mercantili e minoranze etniche in Campania tra Medioevo ed Età moderna, ed. by Teresa Colletta (Rome: Kappa, 2008), 33–40.

———, ‘L’epigrafia ebraica in Basilicata e Puglia dal IV secolo all’alto Medioevo’, in Ketav, Sefer, Miktav: La cultura ebraica scritta tra Basilicata e Puglia, ed. by Mauro Perani and Mariapina Mascolo (Bari: Edizioni di Pagina, 2014), 189–252.

de Lange, Nicholas, ‘The Hebrew Language in the European Diaspora’, in Studies on the Jewish Diaspora in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, ed. by Benjamin Isaac and Aharon Oppenheimer (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press, 1996), 111–38.

Lapin, Hayim, ‘Epigraphical Rabbis: A Reconsideration’, Jewish Quarterly Review 101 (2011): 311–46, http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jqr.2011.0020.

———, Rabbis as Romans: The Rabbinic Movement in Palestine, 100–400 CE (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179309.001.0001.

Mancuso, Piergabriele, ed., Shabbatai Donnolo’s Sefer Hakhmoni (Leiden: Brill, 2010), https://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004167629.i-416.

Millar, Fergus, ‘The Jews of the Graeco-Roman Diaspora between Paganism and Christianity, AD 312–438’, in Jews among Pagans and Christians, ed. by Judith Lieu, John North, and Tessa Rajak (London: Routledge, 1992), 97–123, http://dx.doi.org/10.5149/9780807876657_millar.23.

Mowat, Robert, ‘De l’élément africain dans l’onomastique Latine’, Revue Archéologique 19 (1869): 233–56.

Mussies, Gerard, ‘Jewish Personal Names in Some Non-Literary Sources’, in Studies in Early Jewish Epigraphy, ed. by Jan Willem van Henten and Pieter Willem van der Horst (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 242–76, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004332744_01.

Noy, David, ‘The Jewish Communities of Leontopolis and Venosa’, in Studies in Early Jewish Epigraphy, ed. by Jan Willem van Henten and Pieter Willem van der Horst (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 162–82, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004332744_010.

———, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, Volume 1: Italy (Excluding the City of Rome), Spain and Gaul (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511520631.

———, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, Volume 2: The City of Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511520631.

———, ‘Letters Out of Judaea: Echoes of Israel in Jewish Inscriptions from Europe’, in Jewish Local Patriotism and Self-Identification in the Graeco-Roman Period, ed. by Siân Jones and Sarah Pearce (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 106–17.

———, ‘Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe: Addenda and Corrigenda’, in Hebraica Hereditas: Studi in onore di Cesare Colafemmina, ed. by Giancarlo Lacerenza (Naples: Università “L’Orientale”, 2005), 123–42.

Noy, David, and Hanswulf Bloedhorn, eds., Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis, Volume 3: Syria and Cyprus (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2004).

Noy, David, and Susan Sorek, ‘Claudia Aster and Curtia Euodia: Two Jewish Women in Roman Italy’, Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary e-Journal 5 (2007), http://wjudaism.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/wjudaism/article/view/3177.

Perani, Mauro, ‘A proposito dell’iscrizione sepolcrale ebraico-latina di Anna figlia di Rabbi Giuliu da Oria’, Sefer Yuhasin 2 (2014): 65–91.

Richardson, Peter, ‘Augustan-Era Synagogues in Rome’, in Judaism and Christianity in First-Century Rome, ed. by Karl P. Donfried and Peter Richardson (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 17–29.

Rutgers, Leonard V., The Jews in Late Ancient Rome: Evidence of Cultural Interaction in the Roman Diaspora (Leiden: Brill, 1995), http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004283473.

———, ‘Justinian’s Novella 146 between Jews and Christians’, in Jewish Culture and Society under the Christian Roman Empire, ed. by Richard Kalmin and Seth Schwartz (Leuven: Peeters, 2003), 385–407.

Schwartz, Seth, ‘Rabbinization in the Sixth Century’, in The Talmud Yerushalmi and Graeco-Roman Culture III, ed. by Peter Schäfer (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2002), 55–69.

Segal, Lester A., ‘R. Matiah ben Heresh of Rome on Religious Duties and Redemption: Reaction to Sectarian Teaching’, Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 58 (1992): 221–41, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3622634.

Simonsohn, Shlomo, ‘The Hebrew Revival among Early Medieval European Jews’, in Salo Wittmayer Baron Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, ed. by Saul Lieberman and Arthur Hyman, 3 vols. (Jerusalem: American Academy for Jewish Research, 1974), II, 831–58.

Smelik, Willem, ‘Justinian’s Novella 146 and Contemporary Judaism’, in The Greek Scriptures and the Rabbis: Studies from the European Association of Jewish Studies Seminar, ed. by Timothy Michael Law and Alison Salvesen (Leuven: Peeters, 2012), 141–63.

Veltri, Giuseppe, ‘Die Novelle 146 Perì Hebraion. Das Verbot des Targumvortrags in Justinians Politik’, in Die Septuaginta zwischen Judentum und Christentum, ed. by Martin Hengel and Anna Maria Schwemer (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1994), 116–30.

Williams, Margaret H., ‘The Structure of Roman Jewry Re-Considered: Were the Synagogues of Ancient Rome Entirely Homogeneous?’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 104 (1994): 129–41.

———, ‘The Jews of Early Byzantine Venusia: The Family of Faustinus I, the Father’, Journal of Jewish Studies 50 (1999): 38–52, http://dx.doi.org/10.18647/2165/jjs-1999.

1 Shaye J. D. Cohen, ‘Epigraphical Rabbis’, Jewish Quarterly Review 72 (1981): 1–17; Hayim Lapin, ‘Epigraphical Rabbis: A Reconsideration’, Jewish Quarterly Review 101 (2011): 311–46.

2 Lapin, ‘Epigraphical Rabbis’, 333–34.

3 Cohen, ‘Epigraphical Rabbis’, 15.

4 Lester A. Segal, ‘R. Mattiah ben Heresh of Rome on Religious Duties and Redemption: Reaction to Sectarian Teaching’, Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 58 (1992): 221–41; Leonard V. Rutgers, The Jews in Late Ancient Rome: Evidence of Cultural Interaction in the Roman Diaspora (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 203–04.

5 On the many synagogues (buildings and/or communities) attested in the epitaphs from the Jewish catacombs of Rome, see Jean-Baptiste Frey, Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum, Volume 1: Europe (Vatican City: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1936), lxx–lxxxi; Margaret H. Williams, ‘The Structure of Roman Jewry Reconsidered: Were the Synagogues of Ancient Rome Entirely Homogeneous?’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 104 (1994): 129–41; Peter Richardson, ‘Augustan-Era Synagogues in Rome’, in Judaism and Christianity in First-Century Rome, ed. by Karl P. Donfried and Peter Richardson (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 17–29.

6 Rutgers, The Jews in Late Ancient Rome, 204 and 207. For a recent overview on the rabbinic interest in Italy, see the work of Anna Collar, Religious Networks in the Roman Empire: The Spread of New Ideas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 146–223.

7 David Noy, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, Volume 2: The City of Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995; hereafter, JIWE II), no. 544, dated to third–fourth century.

8 JIWE II, no. 307, dated again to the third or fourth century (?).

9 Note also, in the above mentioned JIWE II, no. 68, Eusebius: both didaskalos and nomomathes.

10 A third example of a double titulary with a possible rabbinical flavour can be detected elsewhere in the Western Mediterranean, particularly in the figure of Theodorus, head of the synagogue of Magona (Mahon, Minorca), mentioned in the epistle of the bishop Severus on the conversion of the Jews of Minorca, written in 418: see Severus of Minorca, Letter on the Conversion of the Jews, ed. by Scott Bradbury (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 30–32. Like our Roman Jews Mnaseas and probably Theudas, this Theodorus also had a double title: as a religious leader he was called, in Latin, legis doctor, but as leader of the community he was called (this time in Greek) pater pateron ‘father of the fathers’. According to Bradbury, this linguistic shift may suggest the persistence of Greek as the liturgical language of Magonian Jewry. The connection does not seem certain, however, since the expression pater pateron, also attested in Italy (Venosa), had a civic and not a religious significance.

11 JIWE II, no. 68 (Monteverde); JIWE II, nos. 270, 374 and 390 (Vigna Randanini).

12 Giancarlo Lacerenza, ‘L’iscrizione di Claudia Aster Hierosolymitana’, in Biblica et semitica: Studi in memoria di Francesco Vattioni, ed. by Luigi Cagni (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 1999), 303–13; David Noy, Susan Sorek, ‘Claudia Aster and Curtia Euodia: Two Jewish Women in Roman Italy’, Women in Judaism 5 (2007), 2–14.

13 David Noy, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, Volume 1: Italy (excluding the City of Rome), Spain and Gaul (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993; hereafter JIWE I), no. 22.

14 Maria Conticello de’ Spagnolis, ‘Una testimonianza giudaica a Nuceria Alfaterna’, in Ercolano 1738–1988: 250 anni di ricerca archeologica, ed. by Luisa Franchi dell’Orto (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1993), 243–52; Noy, ‘Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe: Addenda and Corrigenda’, in Hebraica Hereditas: Studi in onore di Cesare Colafemmina, ed. by Giancarlo Lacerenza (Naples: Università “L’Orientale”, 2005), 123–42 (128, New 41a–b).

15 David Noy and Hanswulf Bloedhorn, Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis, Volume 3: Syria and Cyprus (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2004), 55–57 (Syr36).

16 On the adjective ἔντιμος here, see also Andrew Chester, ‘The Relevance of Jewish Inscriptions for New Testament Ethics’, in Early Christian Ethics in Interaction with Jewish and Greco-Roman Contexts, ed. by Jan Willem van Henten and Joseph Verheyden (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 107–45 (114).

17 See, particularly, the use of ἔντιμος in Isa. 43.4 and Luke 7.2.

18 It can be noted that, up to this day, in Western Diaspora epigraphy, the name Abba Maris appears just here. Elsewhere, just to give some examples, we find it three times in Jaffa, according to the Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palestinae, Volume 3: South Coast, 2161–2648, ed. by Walter Ameling et al. (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2014): (Ἀββομαρι, 2182; Ἀμβωμαρη, 2187; and Ἀββομαρης, 2230), not to mention the various titles Abba and Mari appearing individually.

19 Of the various tombs, inscriptions, and other artifacts found there, only about ten texts survived and are known today. See JIWE I, nos. 27–35.

20 Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the distinction between iudaeus and ebraeus in ancient Jewish epitaphs as well as in various literary sources. The only positive conclusion achieved up to this day is that a substantial difference existed between the two terms. See the detailed discussion in David Noy, ‘Letters out of Judaea: Echoes of Israel in Jewish Inscriptions from Europe’, in Jewish Local Patriotism and Self-Identification in the Graeco-Roman Period, ed. by Siân Jones and Sarah Pearce (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 106–17 (111–15).

21 Other people from Caesarea and other Palestinian locales attested in western Jewish inscriptions are mentioned in Noy, ‘Letters’, passim.

22 The epitaph, often and erroneously referred to the city of Salerno, is lost and it is known only from eighteenth-century copies: see Giancarlo Lacerenza, ‘Frustula iudaica neapolitana’, Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli 58 (1998): 334–46.

23 See Est. 1.7: וְיֵין מַלְכוּת רָב כְּיַד הַמֶּלֶךְ; Vulgate: vinum quoque ut magnificentia regia dignum erat abundans et praecipuum.

24 On Abundantius as a possible translation of rebbi, see the ingenious but problematic suggestion of Robert Mowat, ‘L’élément africain dans l’onomastique latine’, Revue Archéologique 19 (1869): 233–56 (247–48).

25 Gerard Mussies, ‘Jewish Personal Names in Some Non-Literary Sources’, in Studies in Early Jewish Epigraphy, ed. by Jan Willem van Henten and Pieter Willem van der Horst (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 242–76 (247–48). See also Beate Ego, Targum scheni zu Ester (Tübingen: Siebeck, 1996), 221.

26 Procopius, Bellum Gothicum, I.8.41 and I.10.24–26.

27 Giancarlo Lacerenza, ‘La topografia storica delle giudecche di Napoli nei secoli X-XVI’, Materia giudaica 11 (2006): 113–42 (115–18).

28 Gregory the Great, Epistulae 4.9 (596 CE), on which see Giancarlo Lacerenza, ‘Attività ebraiche nella Napoli medievale: Un excursus’, in Tra storia e urbanistica: Colonie mercantili e minoranze etniche in Campania tra Medioevo ed Età moderna, ed. by Teresa Colletta (Rome: Kappa, 2008), 33–40.

29 Gregory the Great, Epistulae, 13.13 (602 CE).

30 David Noy, ‘The Jewish Communities of Leontopolis and Venosa’, in Studies in Early Jewish Epigraphy, ed. by Jan Willem van Henten and Pieter Willem van der Horst (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 162–82.

31 My translation, slightly different from Noy’s in JIWE I.

32 Raffaele Garrucci, ‘Cimitero ebraico di Venosa in Puglia’, Civiltà Cattolica 12 (1883): 707–20; Margaret Williams, ‘The Jews of Early Byzantine Venusia: The Family of Faustinus I, the Father’, Journal of Jewish Studies 50 (1999): 38–52.

33 Francesco Grelle, ‘Patroni ebrei in città tardoantiche’, in Epigrafia e territorio, politica e società: Temi di antichità romane, ed. by Mario Pani (Bari: Edipuglia, 1994), 139–58 (reprinted in idem, Diritto e società nel mondo romano, Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2005, 394–95).

34 Pieter Willem van der Horst, Ancient Jewish Epitaphs: An Introductory Survey of a Millennium of Jewish Funerary Epigraphy (300 BCE–700 CE) (Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1991), 100; JIWE I, 119; Grelle, ‘Patroni ebrei’, 152; Williams, ‘The Jews’.

35 Giancarlo Lacerenza, ‘Ebraiche liturgie e peregrini apostuli nell’Italia bizantina’, in Una manna buona per Mantova: Studi in onore di Vittore Colorni per il suo 92° compleanno, ed. by Mauro Perani (Florence: Olschki, 2004), 61–72.

36 See Vittore Colorni, ‘L’uso del greco nella liturgia del giudaismo ellenistico e la Novella 146 di Giustiniano’, in Judaica Minora: Saggi sulla storia dell’ebraismo italiano dall’antichità all’età moderna (Milan: Giuffrè, 1983), 1–66; Giuseppe Veltri, ‘Die Novelle 146 Perì Hebraion: Das Verbot des Targumvortrags in Justinians Politik’, in Die Septuaginta zwischen Judentum und Christentum, ed. by Martin Hengel and Anna Maria Schwemer (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1994), 116–30; Leonard V. Rutgers, ‘Justinian’s Novella 146 between Jews and Christians’, in Jewish Culture and Society under the Christian Roman Empire, ed. by Richard Kalmin and Seth Schwartz (Leuven: Peeters, 2003), 385–407; Willem F. Smelik, ‘Justinian’s Novella 146 and Contemporary Judaism’, in Greek Scripture and the Rabbis, ed. by Timothy Michael Law and Alison Salvesen (Leuven: Peeters, 2012), 141–63.

37 Neque licentiam habebunt hi qui ab eis maiores omnibus archipherecitae aut presbyteri forsitan aut magistri appellati perinoeis aliquibus aut anathematismis hoc prohibere nisi velint propter eos castigati corporis poenis et insuper haec privationem facultatum nolentes sustinere, meliora vero et deo amabiliora volentibus nobis et iubentibus (Novella 146.1.2).

38 See, for instance, the acute examination of Seth Schwartz, ‘Rabbinization in the Sixth Century’, in The Talmud Yerushalmi and Graeco-Roman Culture III, ed. by Peter Schäfer (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2002), 55–69 (59–61).

39 Fergus Millar, ‘The Jews of the Graeco-Roman Diaspora between Paganism and Christianity, A.D. 312–438’, in The Jews among Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire, ed. by Judith Lieu, John North, and Tessa Rajak (London: Routledge, 1992), 97–123 (111), reprinted in Rome, the Greek World, and the East, Volume 3: The Greek World, the Jews, and the East, ed. by Hannah M. Cotton and Guy M. Rogers (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 432–56. A similar and reasonable conclusion can be found in Rutgers, The Jews, 205.

40 Cesare Colafemmina, ‘Una nuova epigrafe ebraica altomedievale a Lavello’, Vetera Christianorum 29 (1992): 411–21; idem, ‘Hebrew Inscriptions of the Early Medieval Period in Southern Italy’, in The Jews of Italy: Memory and Identity, ed. by Barbara Garvin and Bernard Cooperman (Bethesda: University Press of Maryland, 2000), 65–81 (71–77).

41 As they are described (strangely enough, given the rigour and general soundness of the volume) by Hayim Lapin, Rabbis as Romans: The Rabbinic Movement in Palestine, 100–400 CE (Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 259, n. 45.

42 JIWE I, no. 195. Latin text: Hic requi/scit d(omi)na / Anna fili/a R(abbi) Guliu et/ate LVI ani / {LVI}. Hebrew: שוכבת פה \ אישה נבונה \ מוכנות בכל \ מצוות אמנה \ ותמצא פני \ אל חנינה \ ליקיצת מי \ מנה זו( ?) שנפ{ט}רה \ חנה בת \ נו שנה. A recent re-examination of the epitaph and its dating can be found in Mauro Perani, ‘A proposito dell’iscrizione sepolcrale ebraico-latina di Anna figlia di Rabbi Giuliu da Oria’, Sefer Yuhasin 2 (2014): 65–91. For a complete presentation of all the late ancient and medieval Jewish epigraphs in southern Italy, see Giancarlo Lacerenza, ‘L’epigrafia ebraica in Basilicata e Puglia dal IV secolo all’alto Medioevo’, in Ketav, Sefer, Miktav: La cultura ebraica scritta tra Basilicata e Puglia, ed. by Mauro Perani and Mariapina Mascolo (Bari: Edizioni di Pagina, 2014), 189–252.

43 Cesare Colafemmina, ‘Iscrizioni ebraiche a Brindisi’, Brundisii res 5 (1973): 91–106, no. II; idem, ‘L’iscrizione brindisina di Baruch ben Yonah e Amittai da Oria’, Brundisii res 7 (1975): 295–300. The text of the epitaph runs as follows (line 1 is just a header): מ]שכב רבי ברוך בן רבי יונ[ה] \ פה הרגיע במרגוע נפש ר[בי] \ ברוך בן רבי יונה נוח נפש \ מבן שישים ושמונה שנים \ יהי שלום על מנוחתו \ קול נשמע מבשר שלום רצון \ יראיו עושה שלום שמעו \ דבר שלום ינוח נפשו משכבו \ בשלום.

44 Umberto Cassuto, ‘Nuove iscrizioni ebraiche di Venosa’, Archivio Storico per la Calabria e la Lucania 4 (1934): 1–9 (5 no. 2); idem (as Moshe David Cassuto), ‘The Hebrew Inscriptions of Ninth-Century Venosa’, Qedem 2 (1945): 99–120 (107–8, no. 6; Hebrew): [ זה(?)] המצבה [שהוצב על] \ [קבר(?)] לרבי אברהם שנפט[ר] \ [וה]וא בן שלשים ושבע שנ]ים[\ [בש]נת שבע מאות וחמש[ים] \ [ושל]ש שנים לחרבן בית \ [ה]מקדש שייבנה בימנו \ [אמ]ן המקום יניח נפשו עם \ [ה]צדיקים בגן עדן \ [וכ]ל שיוליך אותו לבית \ [ה]מקדש ויעשה ממי(?) \ [ש]כתוב לחיים בירושלם.

45 Cassuto, ‘Nuove iscrizioni’ (translated from the Italian).

46 In the absence of any complete overview on this literature, see the introductory essay in Shabbatai Donnolo’s Sefer Hakhmoni: Introduction, Critical Text, and Annotated English Translation, ed. by Piergabriele Mancuso (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 3–40, including a good bibliography.

47 On the continuity of this tradition, see already Nicholas de Lange, ‘The Hebrew Language in the European Diaspora’, in Studies on the Jewish Diaspora in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, ed. by Benjamin Isaac and Aharon Oppenheimer (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 1996), 111–38 (114) and, in more general terms, Shlomo Simonsohn, ‘The Hebrew Revival among Early Medieval European Jews’, in Salo Wittmayer Baron Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, ed. by Saul Lieberman and Arthur Hyman, 3 vols. (Jerusalem: American Academy for Jewish Research, 1974), II, 831–58.