10. Introduction to the Simplified Sign System

© Bonvillian, Kissane Lee, Dooley & Loncke, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0220.01

Many children and adults experience considerable difficulty producing or understanding a spoken language despite having adequate hearing levels. Some of these persons may benefit from learning a full and genuine sign language, such as one of the sign languages used by members of a Deaf1 community. They may acquire a substantial vocabulary of signs and learn to combine them into complex sign utterances. Unfortunately, many other individuals make only very minimal progress in acquiring sign language skills. More specifically, a number of children with autism, an intellectual disability, or cerebral palsy fail to attain the signing skills necessary for effective communication through a full sign language.

Because of the difficulties many of these children experience learning a spoken language or a full and genuine sign language, we developed a sign-communication system that would be easier for them (and members of their families) to learn and to produce. For manual signs to be relatively easily learned and remembered, previous research had shown that the signs needed to have clear ties to what they stood for (their referents). That is, signs would need to resemble or have readily discernible ties to the objects, actions, or properties they represented. For manual signs to be formed accurately, they would need to be composed of handshapes, locations, and movements that were relatively easy to produce. These two principles — selecting or developing signs with largely transparent meanings and that were also easy to form or produce — guided our decisions as to which signs to include in our simplified sign-communication system.

In addition to children who never acquire facility in a spoken language or a full and genuine sign language, there are many other individuals who we hope will benefit from the use of our simplified manual signs. One such group consists of adults who have experienced a loss in their abilities to produce or understand speech (a condition known as aphasia), often after suffering a stroke. Other groups may also wish to learn and use our Simplified Signs. Persons traveling overseas, parents planning an international adoption, preschool teachers, language therapists, and persons trying to acquire a foreign language vocabulary may find our system beneficial as well. Regardless of the particular reasons why someone may wish to learn and use our Simplified Signs, we hope that our system will serve to enhance their abilities to communicate effectively with others.

After some discussion, we decided that the best way to present our Simplified Sign System to teachers, parents, scholars, and interested members of the public was through the publication of two volumes. In the first volume, we focus primarily on research findings on the acquisition of manual signs by typically developing children and by individuals with disabilities. These findings showed that many persons with disabilities have the potential to acquire communication skills through the use of manual signs. In the second volume, the Lexicon, we present the signs that make up the first 1000 signs of our Simplified Sign System. Included in the lexicon are drawings and written descriptions of how the signs are formed. In the future, we hope to publish a third volume with an additional 840 signs.

Tips for Using the Sign Lexicon and Sign Index

In this lexicon, we present the first 1000 manual signs that make up the Simplified Sign System. Many of the signs in our communication system have readily transparent meanings; that is, they clearly resemble the objects, actions, or properties they represent. Such signs are considered to be highly iconic. Adults who encounter highly iconic signs for the first time often are successful at accurately guessing their meanings. In addition, highly iconic signs typically are easily learned and remembered.

Unfortunately, it did not prove possible either to find or to create highly iconic signs for all of the concepts that we wished to include in our sign system. For many of our signs, the relationship between a sign and its meaning becomes apparent only after an explanation of this relationship has been provided. The extent of this relationship between a sign and what it stands for once its meaning has been given is known as its translucency. Many people report that it is easier to remember a sign once the relationship between that sign and its meaning has been explained.

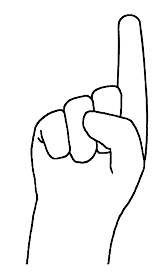

Another large group of easily understood signs included in the present system are those signs that clearly indicate a part of the body or draw attention to something. This indicating action typically is conveyed by the signer’s extended index finger. In most instances, the signer simply points to the intended body part, location, object, or person. These pointing actions often prove to be a successful communication approach. Taken together, the inclusion of highly iconic or transparent signs, translucent signs with explanations of the ties to their meanings, and indicating signs should make the Simplified Sign System relatively easy to learn and remember for many persons.

Signs in the lexicon are listed in alphabetical order under what we perceive to be their most useful or appropriate English translation (or sign gloss). At 1000 signs, however, these Simplified Signs hardly constitute an attempt to render the complete English language in the manual mode. To increase the usefulness of the system, one will often need to use the same sign to convey related concepts that typically would be expressed by different words in English. For this reason, we have also listed closely related words under the principal vocabulary entries in the lexicon; for example, apartment, home, and residence are all listed under the sign HOUSE. Both the principal English vocabulary entries and the many closely related words or synonyms are listed alphabetically in the lexicon’s Sign Index. This Sign Index will help guide the reader from a specific English word to the more general concept under which it is listed in our lexicon. Keep in mind, however, that some English words may have more than one meaning, and that these meanings may or may not be related to each other. Therefore, certain words may be listed in the lexicon or Sign Index under more than one sign. In this case, choose the sign concept that most closely matches the desired meaning.

In addition to including various synonyms under the principal vocabulary entries of most signs, we sometimes list words or concepts that become appropriate if a small change is made in the physical production of that sign. For example, if the sign for TREE is repeated while moving the hands to the side, this slightly modified sign conveys a notion of plurality — multiple trees. With this small change in the way that the main sign TREE is formed or produced, the revised sign can convey the meanings copse, forest, grove, jungle, thicket, trees, and woods. All of these related synonyms are also listed under the main lexicon entry TREE. The information on how to modify the sign and the new meanings indicated by that modification are specifically noted in that sign’s written description.

About 10% of the signs in the initial lexicon can be modified to convey additional meanings. The most common modifications of a sign are repetition (an indication of plurality), adjusting the location of a sign by adding a pointing action (often to indicate the involvement of another part of the body), and reversing the action or movement of a sign (to indicate the opposite meaning or an antonym). We have already provided an example of how a sign can be modified through repetition (TREE). As for adjusting the location of a sign, the sign CAST (MEDICAL) is usually made on the upper leg. However, this sign can be modified to indicate a cast on another part of the body (e.g., the arm) by making the sign as usual and then pointing to one arm. The sign ARRIVE provides an example of how to modify a sign to indicate the opposite meaning (i.e., depart). ARRIVE is made by having the upright pointing-hand (the index finger is extended from an otherwise closed hand) move about six inches to the side to contact the palm of the flat-hand (the hand is flat with fingers together and extended). To indicate the opposite concept, depart, one simply reverses the movement of the active hand. In other words, one starts with the hands touching and then moves the pointing-hand about six inches away from the flat-hand. These slight modifications to certain signs help to increase the number of concepts that can be conveyed using the Simplified Sign System. However, since these modifications may be too complicated for some users of our system, teachers and caregivers will need to exercise discretion as to whether or not a particular user can benefit from these finer conceptual distinctions.

Understanding the Sign Drawings, Written Descriptions, and Memory Aids of the Signs

In the drawings of the signs, we followed several conventions that we anticipated would clarify the movement parameter of the signs. We often drew the initial (and intermediate) positions with dashes or dotted lines and the final positions with solid lines. When we felt it was necessary, we numbered the initial, intermediate, and final locations of a sign’s movement. Occasionally, we drew and numbered separate drawings for each position within a particular sign; this was done so that the handshapes, locations, and movements would be as clear as possible. If the shape of the hand(s) changes from the beginning of a sign to the end of a sign, both the initial handshape and the final handshape were depicted.

Most illustrations were drawn from a frontal (or straight forward) view. Sometimes, however, the sign was better depicted from a side or partial side view, a top-down or partial top-down view, or a rear view (rarely). In these instances, the sign was drawn from a non-standard viewpoint merely to help the sign learner to clearly see and understand how that sign is made (oftentimes, to help clarify that sign’s movement or direction of movement). It does not indicate that the signer should position his or her body in that way when communicating with someone else. Instead, the signer should still face the person(s) with whom he or she is communicating. That way, the signer’s facial expression is clearly visible and the signer can maintain eye contact with the communication partner(s).

For signs with repeated actions, forceful movements, or actions that were hard to portray two-dimensionally, we added arrows or other markings to identify and clarify the movement of those signs. In general, the shape of the arrow is an indicator of the action or movement of the sign. Straight arrows represent movements that occur along straight lines. Arrows with humps indicate hopping movements. Circular arrows denote circular movements. Other curved, wavy, twisting, or arcing arrows denote non-linear or arcing movements. Where the arrow begins and ends indicates or mimics the location of where the movement begins and ends. For sign illustrations with multiple drawings, the arrow(s) are usually added to the intermediate and/or final drawings instead of the first drawing. In addition, the size of an arrow is an indicator of the size of the movement. Smaller or shorter arrows denote smaller movements; larger or longer arrows denote bigger movements. Sometimes the arrows are single-headed; in these cases, the main movement is in one direction — the direction of the arrowhead. In illustrations with double-headed arrows, the movement is in both directions depicted. Finally, an illustration with one arrow usually means that the sign action is performed only once. More than one copy of an arrow denotes that the same action is performed multiple times. For example, two identical arrows would indicate that the sign action typically is performed twice. Three identical arrows would indicate that the sign action is performed three or more times.

Quote marks or small lines in an illustration usually indicate that the hand, fingers, or relevant body parts wiggle or shake slightly from side-to-side or back-and-forth (e.g., ANGRY, FRUSTRATED, PIANO). On rare occasions they denote a sucking action (e.g., STRAW (DRINKING)) or another small movement. Short lines where two body parts make contact denote that the contact is forceful in nature (e.g., APPLAUD, NOW, SLAP) or serve to clarify that contact is actually made. Straight lines drawn near the mouth indicate the blowing of air (e.g., EASY, HORN (MUSICAL), NEW). Occasionally, we drew dashes from the signer’s eyes that converge on another part of the drawing. In these instances, the dashes represent that the signer should gaze intently at the indicated location (e.g., LATE, STUDY).

Although many sign illustrations are drawn with a neutral facial expression, some are drawn with a facial expression that is consistent with the meaning of the sign. For example, an angry or irate facial expression is used for the sign ANGRY, an unhappy facial expression for the sign FROWN, and a happy facial expression for the sign SMILE. Other signs are produced with facial movements that serve to clarify the meaning of the sign; for example, puffy cheeks for the sign SQUIRREL or an open mouth for the sign SURPRISE. We encourage parents, caregivers, teachers, and other professionals to produce relevant facial expressions and movements when making such signs. The main user or sign learner, however, may not be able to successfully control or produce such facial expressions or movements and should not be required to do so.

Written Sign Descriptions

Each written sign description provides information on the sign’s principal formational parameters — the handshape, the location on or near the body where the sign is made, the movement or action of the signer’s hand(s) or arm(s), the palm orientation of the hand(s), and the orientation of the fingers or knuckles relative to the signer. In a small number of signs (e.g., RESPECT), the movements of other parts of the body are specified as well.

In some sign descriptions, information also is provided on the signer’s accompanying facial expressions or movements. In these instances, the facial expressions or movements should match the emotional content of the concepts being conveyed. For example, if one were making the sign for ANGRY or SAD, it would be confusing to make each sign with an accompanying smile. Rather, a frown or an expression of anger or unhappiness would be consistent with that sign’s meaning and should be included, if possible. For those individuals who have difficulty making facial expressions, however, the meaning of the sign can still be conveyed accurately with a neutral facial expression.

Handshapes

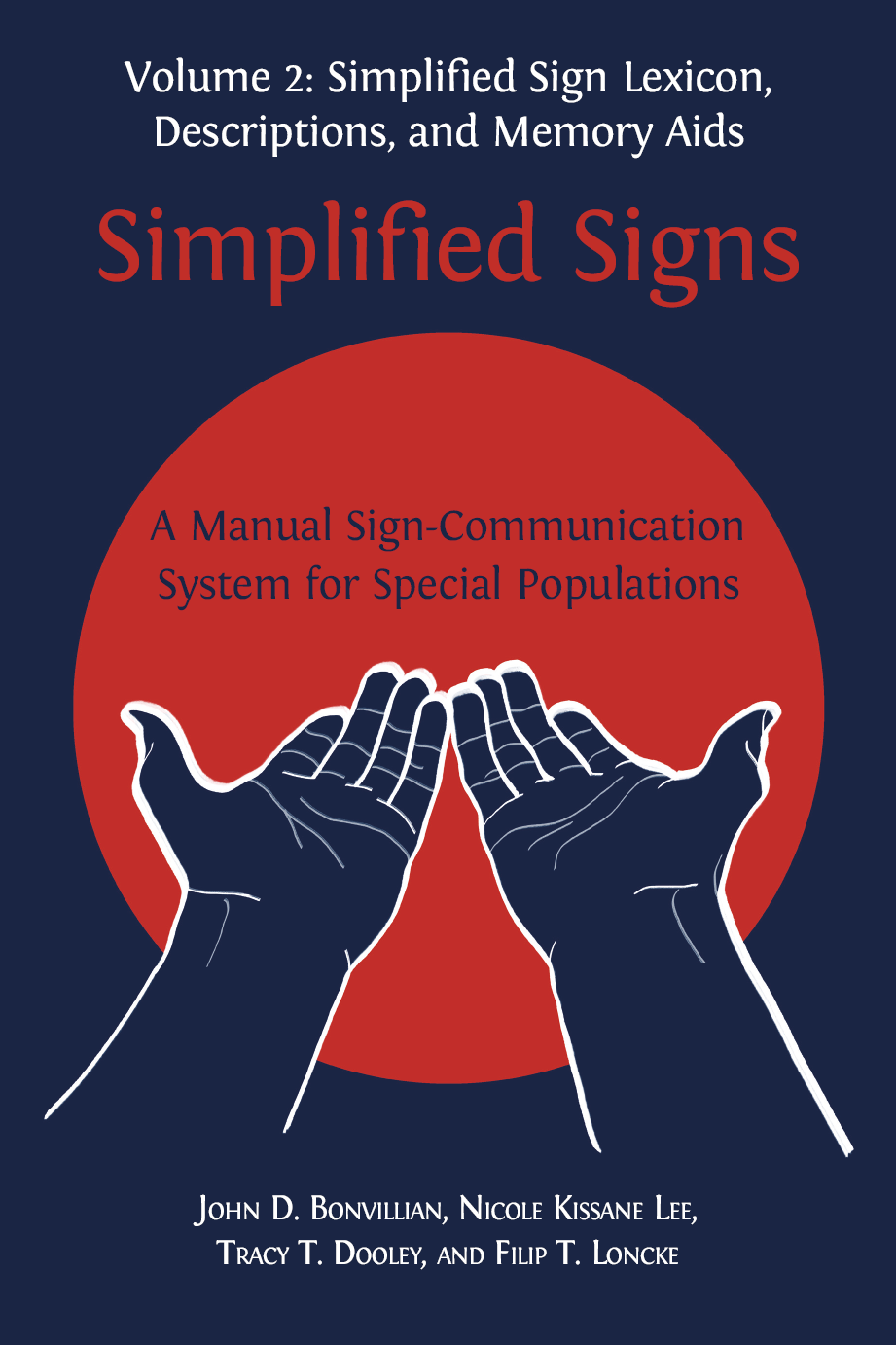

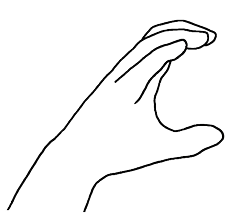

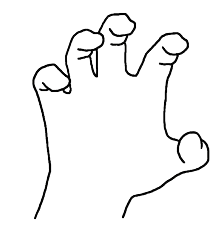

In describing sign handshapes, we rely to a considerable extent on the manual alphabet and numeration system used by Deaf persons in much of continental Europe and the Americas. Because the letters of the manual alphabet, manual numbers, and gesture names will not be familiar to many Simplified Sign users, we provide a brief explanation of how the hands are shaped in each written description. Slightly more expanded descriptions of these handshapes and drawings of them (from the viewer’s perspective) are provided on the following pages (see also Appendix B, Volume 1).

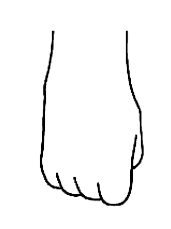

Also included with the drawings in this chapter is information on how each handshape is used and the various meanings that each handshape may indicate. This information is provided so that learners can begin to associate the iconic or representative form, shape, or configuration of the hand(s) with their underlying linguistic meanings. This, in turn, should greatly help certain individuals to learn those signs and to remember how to form them. Understanding these common designations or representations may also help caregivers to develop signs for needed concepts that do not currently exist in the Simplified Sign System lexicon. For example, the flat-hand is often used to represent flat, even, or smooth surfaces in one’s environment or to indicate or highlight the flat nature of a given object. This handshape is also frequently used as a stationary base or foundation for the production of two-handed asymmetrical signs (signs whose handshapes are different; one hand typically performs the action of the sign, while the other hand does not move). In many instances, the flat-hand conceptually represents the floor, ground, or the surface on which one is standing or sitting. It also frequently represents a higher-level, smooth surface (such as a desk, countertop, or table). If one is trying to create a sign to represent an object that has one or more of these characteristics, the use of the flat-hand is encouraged. In fact, the easily formed flat-hand is the most frequently used handshape in the Simplified Sign System, comprising about 25% of the total handshape usage in the initial lexicon.

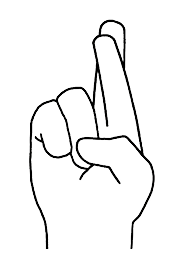

In addition, we have noted how common or prevalent each handshape is within the main lexicon of 1000 Simplified Signs. The handshapes are divided into four basic categories: very common (occurs over l50 times in the lexicon), common (used from 50–149 times), occasional (used 10–49 times), and rare (occurs fewer than 10 times). When creating new signs for inclusion in the system, we emphasized using the very common or common handshapes, as they are typically the easiest to form and to remember. This is an important principle, especially considering that certain Simplified Sign users may have motor or memory impairments. The descriptions of all of the handshapes, as well as the supporting information on their use and prevalence within the Simplified Sign System, are found below:

It should be noted that in the written descriptions of the formation of some two-handed asymmetrical signs (signs where one hand typically is the active, dominant hand and the other hand is stationary and serves as a base), no handshape is specified for the stationary hand. In these instances, the handshape is not relevant and the signer should simply keep the hand in a natural, comfortable position.

Palm Orientation

Because the concept of palm orientation of the hand(s) may not be familiar to many users of the Simplified Sign System, we have provided expanded descriptions and drawings of them below (see also Appendix C, Volume 1). A flat-hand is used in the illustrations, which are drawn from the viewer’s perspective.

Finger/Knuckle Orientation

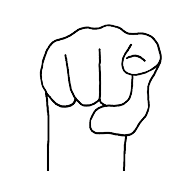

Please note that in most written descriptions of the sign formations, we specify the orientation of the finger(s) or knuckles of the hand(s) as well. This is because palm orientation alone may not be specific enough. The convention for describing finger/knuckle orientation (see also Appendix C, Volume 1) is similar to that for palm orientation. Descriptions and drawings of finger/knuckle orientations are provided below. A pointing-hand is used to illustrate the finger orientations, and a fist (the hand forms a fist) is used to illustrate the knuckle orientations. They are drawn from the viewer’s perspective.

In many sign descriptions, we note that the signer’s finger(s) or knuckles are pointing diagonally forward. This is generally the most natural hand orientation when a sign is made in front of the body. A flat-hand and a pointing-hand are used to illustrate the finger orientations, and a fist is used to illustrate the knuckle orientations. They are drawn from the viewer’s perspective.

One-handed Versions of Two-handed Signs

It should be noted that some Simplified Sign System signers may have very limited use of or no use of one arm or hand. Whether this is a temporary condition or a chronic impairment, this should not significantly inhibit or affect their use of Simplified Signs. It is not a problem at all for the many signs made with a single hand — simply use the available hand (it does not matter whether a person uses the right hand or the left hand as this does not affect the meaning of the sign.) Nor is it typically a problem with two-handed symmetrical signs; that is, those signs with mirror image handshapes, locations, and movements. For these signs, one should use the available hand and the communication partner simply imagines the mirror image component. Two-handed asymmetrical signs, however, represent more of a challenge. For many of these two-handed signs, it should be possible to substitute the immobile arm or a convenient surface for the stationary hand. That is, make the sign directly on the impaired arm or a nearby surface in lieu of using a stationary hand in front of one’s body. If this approach proves too difficult or cumbersome, then one may modify the sign to accommodate an individual user’s particular motor limitations.

Natural Variations in Sign Formation and Production

In our written descriptions, we often denote the level at which a sign is made (both in initial position and final position), the distances between the hands (when both hands are involved in the production of a sign), and the length of the sign’s action or movement. We provided this information to be as specific as possible about how each sign is made. But just as an individual’s motor abilities will influence how that person makes a particular sign, that person’s physical size and body type also impact the production of a sign. For example, a taller person’s sign movements will often be larger and longer than those of a smaller or shorter person’s sign movements. The height at which a sign begins or ends and how close together a signer’s hands are may also vary according to the shape and proportions of the signer’s body. Individuals have different musculature and flexibility that will affect how they sign. Just as each person has his or her own unique voice while producing speech or spoken language, each person has a unique way of producing signs and gestures.

The overarching goal for forming a sign is to clearly and accurately produce a concept while maintaining the signer’s comfort. Small adjustments in sign production are perfectly normal and should be considered within an acceptable range of formation given the characteristics of an individual signer. In fact, we (the authors) often vary our sign productions slightly. Also, while testing the signs for inclusion in our system, we did not score a sign as incorrect if the palm, finger, or knuckle orientation was slightly off the accepted standard (for example, if the palm was slightly diagonally out rather than straight to the side, or if the fingers or knuckles were diagonally up rather than straight up). Most such variations have no impact on the sign’s meaning and thus should be considered satisfactory.

Another factor that impacts sign production is whether a person is sitting or standing while producing a sign. If a person is seated, then many signs formed by that person may start and end at a different level, the movement of the sign may be smaller, and/or the hands may be closer together. In other words, the height, length, and size of signs varies not only according to one’s physical abilities or one’s physical size or body type, but also according to whether one is standing or seated. A person who is standing generally has a wider range of movement and thus his or her signs may be “bigger” than those formed while seated. This is perfectly normal and should not be considered an error.

Other factors that may affect sign formation include fatigue, speed at which the sign is made, and whether the signer is distracted by the surrounding environment. If these particular factors negatively impact a person’s sign production or a communication partner’s understanding of those signs, then it is important to re-establish eye contact, slow down sign production, or take a break. Just as with spoken language, sign communication involves more than one person, each of whom needs to pay attention to the other in order for the interaction to be successful. Our written descriptions of the signs should be considered general guidelines for production that may be adjusted on the basis of multiple factors. To optimize the use of Simplified Signs, adjustments must be made according to a person’s physical abilities, body type, and various situational factors.

Memory Aids

In addition to the sign drawings and written descriptions, we have also provided the sign learner with both a short memory aid and a longer memory aid for each concept depicted. The longer memory aids often detail the direct relationship between a sign’s formation (its handshape, location, and movement) and the sign’s underlying meaning. We find that these memory aids reflect how we think about and remember a sign’s formation. It should be noted that these memory aids do not necessarily reflect the historic origins of the signs in the many native sign languages of the world. We feel that these more explicit memory aids will be of particular help to people with typical cognitive abilities but who have not been previously exposed to a sign language. Until one becomes more adept at recognizing the visual links between a sign’s formation and its meaning, the longer memory aids help to clarify this information. As many potential users of our system may not be native speakers of English (particularly, those people learning English as a second or additional language), we also often provide the sign learner with a basic definition of the main English gloss or concept. As one English word may represent multiple different or unrelated concepts, we provide a definition that helps to clarify (or disambiguate) which concept is being referenced. Once a person is familiar enough with signing (in general) and our Simplified Signs (in particular), his or her use of the longer memory aids may decline. In this case, the shorter or briefer memory aid that we have provided with each sign will serve as a quick reminder of that sign’s formation.

Concluding Remarks

In this chapter, we began by explaining the reasoning behind our selection and development of signs for the Simplified Sign System. Most of the present chapter, however, was devoted to providing information on sign formation that we believe will aid sign learners and teachers in their sign production and in their understanding of the written descriptions of how Simplified Signs are formed. In the following chapter, we provide the initial lexicon of 1000 manual signs of the Simplified Sign System. We hope that our system will be helpful in improving the communicative interactions of many different non-speaking or minimally verbal individuals and the teachers, caregivers, family members, and friends who are so important to them. We also hope that this system will prove of assistance to many other persons trying to communicate more effectively, including travelers in a foreign country, students learning a new language, and parents interacting with their young children.

1 The spelling of Deaf with a capital D has emerged as a convention for indicating those deaf persons who communicate primarily through a sign language and who interact frequently with other signers. Such persons often self-identify with Deaf culture. The spelling of deaf with a lowercase d is used to refer to any person with a substantial hearing loss. It is also used to indicate the medical condition of deafness or when focusing on the physical aspects of hearing loss.

.png)

.png)