10. The Contribution of European Cohesion Policy to Public Investment

© Chapter authors, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0222.10

Introduction

Cohesion Policy (known also as Regional Policy) is the European Union’s main development policy (Viesti and Prota 2008; Viesti 2019). It has evolved over time: from a tool to counterbalance the regional disparities inevitably emerging from the Single Market, and, subsequently, from the Monetary Union, to the investment pillar of the new economic policy coordination (Berkowitz et al. 2015). In the period 2007–2013, as result of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, Cohesion Policy has been the major source of finance for public investment for many Member States of the European Union, representing up to 57% of government capital investment.

The aim of this chapter is twofold: first, to provide an overview of the expenditures of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Cohesion Fund (CF) at national and regional levels over the last decades, and second, to discuss the impact of the investments co-financed through these two funds mainly in terms of physical achievements. We focus on the ERDF and the CF (which represent about 75% of Cohesion Policy funding in the 2014–2020 programming period), since the bulk of their expenditure provides support to public investment.4

Our analysis covers three programming periods: 1994–1999, 2000–2006, 2007–2013, though we focus mainly on 2000–2006 and 2007–2013 in order to take into account the Eastern enlargement of the European Union and the effects of 2008 crisis.

We use two datasets made available by the European Commission. The first one provides, in a single source, historic long-term regionalised annual EU expenditure data covering four programming periods, but it does not contain thematic information.5 The second one shows allocations and expenditures from 2000 to 2013 broken down by expenditure categories. Moreover, the study on “Geography of Expenditures”, one of the Work Packages of the ex post evaluation of Cohesion Policy programmes 2007–2013, has produced a consolidated database covering the regional ERDF and CF investments from 2000 to year 2014 at NUTS2 level (WIIW and ISMERI Europa 2015).6

The chapter is structured as follows. Section 10.1. describes the main features of the Cohesion Policy and its evolution across time. Section 10.2. focuses on the total levels of the European Regional Development Fund and Cohesion Fund expenditure in the Member States and looks at the trends observed in the last years. Section 10.3. examines the weight of European investments within the total public expenditure and describes some of the main “tangible” results generated by the implementation of both the ERDF and the CF measures, as far as public physical investments are concerned. Section 10.4. focuses on the regional level and discusses the economic spillovers produced by the Cohesion Policy in favour of the more advanced regions and countries in the EU. Section 10.5. summarizes the main messages of our analysis.

10.1. European Cohesion Policy: An Overview7

The evolution of Cohesion Policy has been extensively described in the literature (Viesti and Prota 2008; Molle 2015; Piattoni and Polverari 2016; Viesti 2019). One of the main drivers of this evolution has been the necessity to face the challenges arising from enlargement of the European Union to integrate regions with different levels of development; in particular, those of the countries of Southern Europe in 1981 and 1986 and those of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in 2004, 2007 and 2013.

The Cohesion Policy emerged in the second half of the 1980s. The Single European Act (1986) added the Title V (Economic and Social Cohesion) to the Treaty of Rome, with the aim of providing a comprehensive reform of the instruments for regional development, namely the Structural Funds (ERDF and ESF). With the Delors package of 1987–1988, €63 bn were allocated to this policy for the period 1989–1993, accounting for a growing share of the total Community budget: from 18%, in 1987, to 29%, in 1993. Moreover, the fundamental principles underpinning Cohesion Policy were set out as follows:

- Concentration: the greater part of Structural Funds resources are concentrated on the poorest regions and countries, namely those having a GDP per capita lower than 75% of the EU average, at purchasing power parity;

- Programming: multi-annual national programmes aligned on EU objectives and priorities, with the same time span of the EU overall budget;

- Partnership: each programme is developed through a collective process involving authorities at European, regional and local level, social partners and organisations from civil society;

- Additionality: financing from the European Structural Funds may not replace national spending by a member country.

With the Treaty of Maastricht, Structural Funds assumed an even more important role: they became the principal, if not the unique, Community instrument aimed at guaranteeing that the processes of economic growth would benefit all the territories (and thus all the citizens) of the Union. In 1994, with a controversial decision, a new fund, the Cohesion Fund, was set up with the aim of assisting the poorest EU Member States whose gross national income per capita totalled less than 90% of the EU average. Cohesion Fund resources were allocated to infrastructural measures in the field of transport and environment. With the so-called Delors II package, the action of the Structural Funds was further reinforced: €167 bn were allocated for the period 1994–1999 (in the last year, they came to represent 36% of the total Community budget). The main beneficiaries were Spain, Italy and Germany (because of the reunification), followed by Portugal, Greece, France and the United Kingdom.

In 1997, the Commission published the document Agenda 2000 which reconfirmed the centrality of the Cohesion Policy. The European Council of Berlin of 24–25 March 1999 approved the Commission proposals, but with a smaller amount of financing. This was a decision with a very important political meaning in light of the then imminent enlargement of the Union, planned for 2004. The era of broad consensus on Cohesion Policy ended, and for the first time the resources were to be reduced during the programming period: from €32 bn in 2000 to €29 bn in 2006.

In 2004, ten new Member States joined the EU (Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Hungary), a major milestone in the Union’s development. With the accession of these countries, the regional disparities within the Union become considerably more intense. The resources of the Cohesion Policy represented about three quarters of the disbursements of the Community budget toward the new Member States, and played a fundamental role in accompanying the restructuring processes of those economies.

At that time, the political climate made the discussion on the programming period 2007–2013 particularly long and complex. The budget negotiation was resolved by restricting the size of the budget (despite having to accommodate both the “old” and the “new” Member States to which Romania and Bulgaria would be added in 2007 and Croatia in 2013) and by introducing new compensations for the net-contributing States. As in the past, resources were earmarked in substantial measure (€177 bn) to the regions with a per capita income lower than 75% of the Community average, now included in a Convergence Objective.8 The Cohesion Fund had a budget of almost €62 bn. A fundamental aspect of the Cohesion Policy for 2007–2013 was the strong reduction of aid in the EU15. More than half of the €308 bn was allocated to the new Member States.

The construction of the European Cohesion Policy for 2014–2020 was influenced by the publication in 2009 of an authoritative report by an independent Italian expert, Fabrizio Barca (Manzella 2011). The Barca report reiterated the importance of developing integrated intervention programmes built on the basis of the special characteristics of the various regions (“place-based” approach) (Barca 2009). These suggestions were partially put into action. The policy for 2014–2020 in many respects mimics that of the previous period, but it also presents several innovations. Regional allocation criterion changes with respect to the long previous tradition. There is still the category of less developed regions, which correspond as in the past to those with a per capita income in terms of purchasing power below the 75% of the Community average and to which the greatest part of the resources is earmarked. The novelties are represented by the category of “transition” regions (per capita income between 75% and 90%) and by the category of the most developed regions (per capita income above 90%). The Cohesion Fund group now includes the new Member States, Portugal and Greece. The geography of the beneficiaries shifts ever farther towards the East: the new Member States absorb about 55% of the total resources. The significance of these figures is obviously much greater if they are expressed as a percentage of GDP or per inhabitant. Among the old Member States the biggest beneficiary is Italy, followed by Spain; the expenditure diminishes significantly in Germany, while it remains substantially unchanged in Portugal and Greece.

10.2. The Geography of ERDF and CF Expenditures

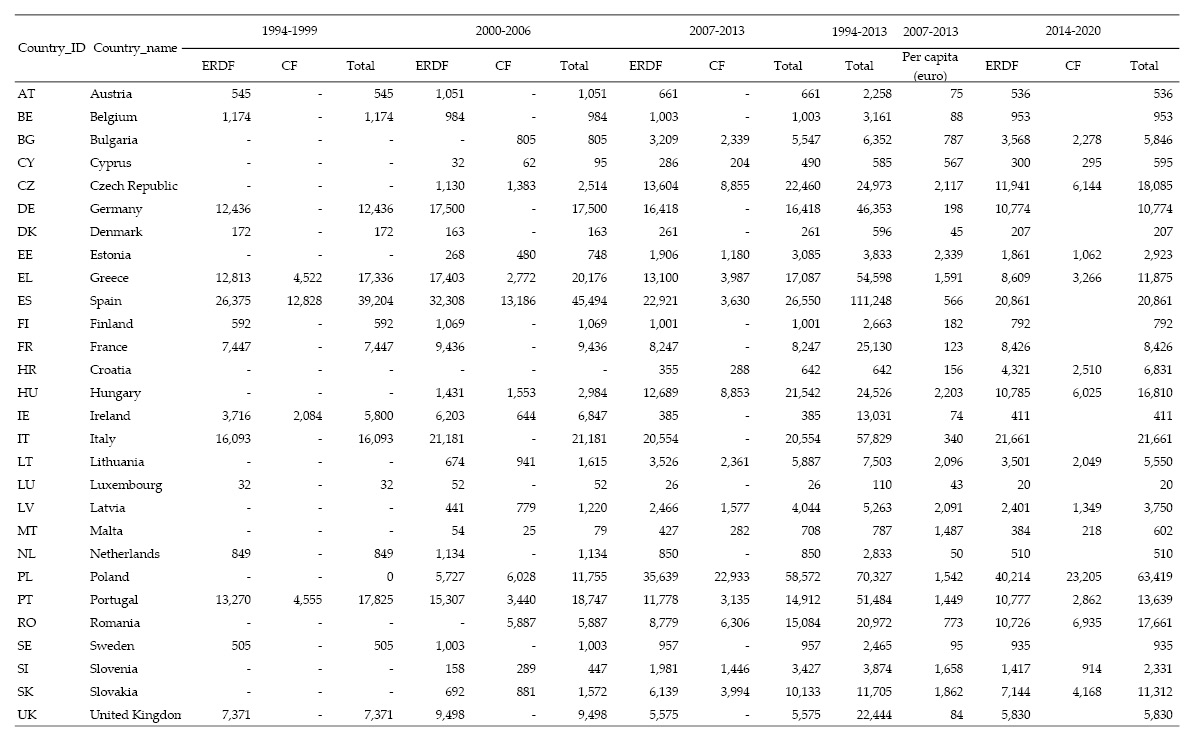

The first question we aim to answer is: “How much have European countries/regions received under the European Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund?”. Table 1 shows the expenditures of the two funds in each Member State from 1994 to 2013, in constant euros; it shows allocations for the period 2014–2020, in current prices, too. It is not possible to add all the periods (current vs. constant euros; expenditures vs. allocations) but the overall picture is still important for understanding the “geography” of the Cohesion Policy. Obviously, in looking at the three programming periods as a whole, it is necessary to keep in mind that the Central and Eastern Europe countries have become members only in 2004 and, therefore, have started to benefit from the Cohesion Policy later than the old Member States.9 Moreover, initially, the Cohesion Fund covered Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland. Later the group incorporated all the new Member States together with Greece and Portugal, while Ireland and Spain — due to the growth of their GDP per capita — became no longer eligible (although the latter retained the right to receive aids in accordance with the transition rules).

Table 1 ERDF and CF expenditures by country, 1995–2013 (constant 2015 prices) and ERDF and CF allocations 2014–2020 (current prices), in million euros

Source of data: European Commission (https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/Other/Historic-EU-payments-regionalised-and-modelled/tc55-7ysv; https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/dataset/ESIF-Regional-Policy-budget-by-country-2014-2020/fift-a67j).

Looking at the period 1994–2013, the Iberian countries clearly emerge as the main beneficiaries: ERDF and CF provided €111 bn to Spain and €51 bn to Portugal. However, notwithstanding its later accession, Poland is the second beneficiary country with €70 bn (2004–2013), ahead of Italy (€58 bn), Greece (€55 bn) and Germany (€46 bn). Another group of countries, including both old (France and United Kingdom) and new (Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania) Member States, received more than €20 bn in the whole period. The Cohesion Policy is definitely of minor importance for a group of Centre-North European countries such as Austria, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden.

It is clear that the expansion of the EU to include the post-socialist CEE countries changed the “geography” of the Cohesion Policy, drawing substantial investment away from Southern Europe: funds for Ireland drastically declined, and Spain, after peaking in 2007–2013 with more than €45 bn, declines subsequently; other Member States, especially the larger ones, kept the same amount of funding, with a decline in 2007–2013 only for the UK. The role of new Member States became crucial: expenditures in Slovakia became larger than in France; in Poland they became almost three times those in Italy.

The eastward shift is even more clear if one looks at allocations for 2014–2020, with the amounts declining in Germany, Greece and Spain, and being confirmed in their magnitude (except for Hungary) in the new Member States. In 2020 Poland will be the country that has received, overall, the most ERDF and CF expenditures, overcoming Spain. In brief, what is evident is that the centre of gravity in Structural Funds allocation has shifted from the Southern regions to the Eastern regions of Europe.

However, absolute figures must be matched by per capita amounts. Table 1 shows the ERDF and CF expenditures per capita for the period of 2007–2013. The three Baltic countries, Hungary and the Czech Republic received more than €2,000 per person; the figure is around €1,500 for Greece and Portugal, as well as for Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia; it goes down to €750 for Bulgaria and Romania, and to €550 for Spain, €350 for Italy, less than €200 for Germany and Finland, around €100 for France and the UK. It is clear how varied the impact of the Cohesion Policy is in the different Member States.

10.3. The Impact of Cohesion Policy on Public Investment

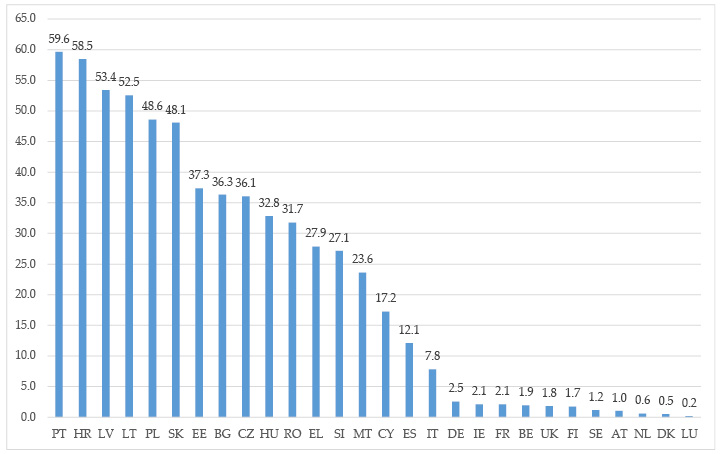

Cohesion Policy plays a key role in financing public investment in Europe. According to the European Commission, its allocations in 2014–2016 are expected to represent 14% of total public investment in the EU. However, its weight is very different across Member States. In some European countries, Cohesion Policy plays a key role; in others, it is significant, even if to a lesser extent; in others, it is negligible. This difference is due to three factors: (i) the size of cohesion expenditures per country compared to the magnitude of the different European economies, (ii) the geography of the crisis that hit Europe, (iii) the use of European Structural and Investment (ESI) expenditures in different typologies of regions.

WIIW and ISMERI Europa (2015) show the proportion of actual Cohesion Policy expenditures to total government capital expenditures (the sum of fixed investments and capital transfers) for the 2007–2013 programming period: this figure is larger than 50% in some small Central and Eastern European countries (including Hungary), larger than 40% in Poland, larger than 30% in most of the other Central and Eastern European countries. In Hungary 94% of railways and 54% of road investment have been financed by the EU Cohesion Policy. In the EU15, the figure is higher in Portugal and Greece, much lower in most Member States (7% for Spain, 4.4 % for Italy and 2.5 % for Germany). However, WIIW and ISMERI Europa (2015) estimate that Cohesion Policy expenditures may have reached 20% of total capital expenditures in Convergence regions in Spain, 15% in Italy and 10% in Germany.

Fig. 1 ERDF and Cohesion Fund allocations, 2015–2017 (percentage of general government capital expenditure)

Source of data: Open data platform, Eurostat — Government statistics. Figure created by authors.

Figure 1 updates and confirms the figures for 2015–2017, using allocations data. The role of ERDF and the Cohesion Fund seems even higher in some countries, namely Portugal (a country in which the burden of servicing the debt is relevant) and Poland. It is reasonable to state that most countries would not have had the financial capacity to carry out such investments otherwise.

Indeed, it is well known that in a number of Member States public investments are still below the pre-crisis period level (Prota 2016); these persistent low levels of public investment (as a share of the GDP) are a cause for concern, because of their possible effect on socio-economic disparities between Member States and regions in the EU. In many countries, therefore, EU funding played a major counter-cyclical role in preventing an even larger reduction in public investment, as confirmed by the increase in EU co-financing rates for Cohesion Policy in the period 2007–2013.10 The EU co-financing rate was raised to different extents in 16 Member States in which the effects of the crisis of 2008 were most severe and the reduction in public investment expenditure (part of budget consolidation measures) was substantial: in Greece the EU co-financing rate went up to 100%.11 Obviously, the final effect of the increase in EU co-financing rates, aimed at reducing the amount of national funding, was to cut the overall amount of funding going into Cohesion Policy programmes.

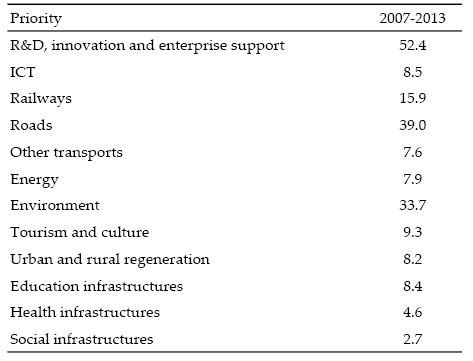

The relative allocation of funding across expenditure items is not identical in all countries and regions. The EU funding is particularly crucial in some key investment areas (Table 2). For 2007–2013 a detailed breakdown of expenditures in eighty-six items is available (WIIW and ISMERI Europa 2015). By aggregating the eight-six intervention priorities to twelve broad policy areas, it emerges that the largest policy area (mainly capital transfers), with about €52 bn, is R&D, innovation and enterprise support. Roads accounts for €39 bn, including €18 bn in motorways in the Trans-European Networks (Ten-T); railways for €15.9 bn (including €12 bn in Ten-T corridors); other transport (urban, multimodal, airports and ports) for €7.6 bn. Environment investment totalled €33.7 bn: main areas of expenditures are water (€16 bn) together with waste, risk prevention and promotion of clean urban transport. Other crucial investment priorities are ICT, energy, tourism and culture, urban and rural regeneration, education, health and social infrastructures.

Table 2 Expenditures of ERDF and CF by priorities, 2007–2013 (constant 2015 euros)

Source of data: European Commission (https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/)

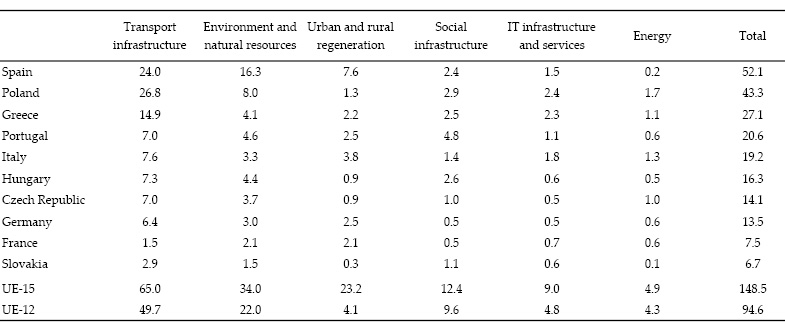

The study “Geography of Expenditures” (WIIW and ISMERI Europa 2015) has produced a consolidated database covering the regional ERDF and CF investments from 2000 to 2013. Using this database, Table 3 shows the breakdown of the overall cumulative expenditure by selected countries in the six policy areas more relevant for public investment, covering more than half of total ERDF and CF expenditures: transport, environment, urban and rural regeneration, social infrastructures, IT infrastructures and services, and energy.12

Table 3 ERDF and Cohesion Fund cumulative 2000–2013 expenditures by selected countries and policy area, in billion euros (constant 2015 prices)

Source of data: European Commission (https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/Other/Historic-EU-payments-regionalised-and-modelled/tc55-7ysv)

Transport infrastructures are clearly the most important policy area, with more than €100 bn in 2000–2013. This expenditure category is extremely relevant in Spain and Poland (around €25 bn) and in general in Central and Eastern European countries. This is particularly important since, as shown by Di Comite et al. (2018), investment in transport infrastructure financed by the Cohesion Policy is changing the accessibility of EU regions. In particular, many regions in Eastern Europe have significantly benefitted from improved accessibility as a result of the Cohesion Policy financing transport infrastructure investments. This has favoured intra-European trade and the organization of manufacturing value chains in Central Europe. As shown by Stöllinger (2016), manufacturing activity in the EU is increasingly concentrated in a Central European manufacturing core, implying divergent paths of structural change across Member States. In the rest of the EU regions accessibility has also increased, though less significantly (see Figure 22 in Di Comite et al. 2018). However, in Portugal and Spain ERDF and CF investments were crucial for the improvement, since the mid-1990s, of the road and railway network; the same has happened in Greece (consider the motorway from Igoumenitsa to Athens).

Investment for environment and natural resources, the second policy area in order of importance, totalled €56 bn, followed by urban and rural regeneration (€27 bn), social infrastructures, IT infrastructures and energy. However, priorities for expenditures are different among countries. In EU12, transport and environment are extremely relevant, also as a consequence of the Cohesion Funds rules. On the contrary, in EU15, territorial regeneration and social infrastructures are relatively more important. Some national patterns also emerge: in Spain expenditures for the environment and urban regeneration are particularly high; in Portugal social infrastructures play a key role. Comparing 2000–2006 with 2007–2013 confirms the importance of transport, while public investments in the energy sector increase.

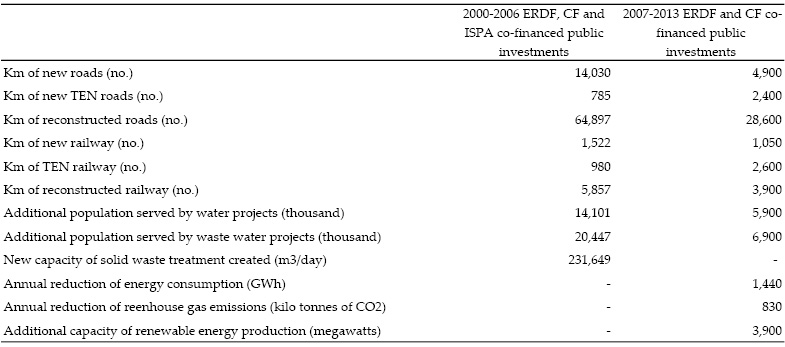

What are the results of the Cohesion Policy as far as public physical investments are concerned? Table 4 shows the main achievements.13 For 2000–2006, it is useful to consider also the Structural Pre-Accession Instrument (ISPA) fund, alongside the ERDF and CF.

Table 4 Main achievements of the Cohesion Policy co-financed public investments (2000–2006; 2006–2013)

Source of data: European Commission (https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/it/policy/evaluations/ec/2000-2006; https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/it/policy/evaluations/ec/2007-2013)

In 2000–2006 more than 14,000 km of new roads were built, plus almost 800 km related to Trans-European Network projects. Additionally, almost 65,000 km of reconstructed road were financed. As regards railways, more than 1,500 km of new railways were constructed, as well as almost 1,000 km of TEN-related railways, and more than 5,800 km of railways were reconstructed. Railway projects were mainly concentrated in the areas of Andalusia and Galicia (Spain), Lisbon and Vale do Tejo (Portugal), Mazowieckie (Poland), Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Germany) and Puglia (Italy). These regions all experienced forms of improvements directly resulting from the policies at hand, in particular with reference to pre-existing critical aspects such as poor quality of road/rail network, congestion, bottlenecks, missing or poor intermodal links, ports/airports’ lack of capacity (Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy and Steer Davies Gleave 2010).

The environmental investments mainly referred to the facilities and distribution network needed to provide clean drinking water to households, the plant and pipelines required for the collection and treatment of wastewater and the facilities needed to collect, recycle and manage solid waste (Applica 2012). In these fields the EU invested in more than 165,000 projects; they were quite effective, given that more than 14 million additional people were served. In addition, more than 6,000 projects on wastewater were financed, which resulted in more than 20 million new people being served.14 Finally, almost 3,000 solid waste treatment projects were also financed, mainly located in Germany, Spain, France and Italy, resulting in a considerable improvement of total capacity of more than 230,000 m3/day (ADE 2009). Importantly, from 2000 to 2009, the shares of landfilled waste dropped from 51% to 32% in the EU15 and from 96% to 85% in the EU12. At the same time, the share of recycled waste rose from 31% to 44% in the EU15 and from 2% to 12% in the EU12, with peaks in Slovenia (35%), Estonia (25%) and Poland (20%).

In 2007–2013 both the ERDF and the CF, as already mentioned, focused greatly on transport expenditures. A considerable share was utilized for the constructions of new roads or the upgrading of existing ones. For example, in Poland and Romania this share is higher than 60%, and in none of the Member States is it less than 40%. In terms of actual achievements, this resulted in more than 4,800 km of new roads, of which over 70% were built in the EU12, with a substantial amount in Poland. Almost 28,000 km of existing roads were upgraded (70% in theEU10).15

More than 1,000 km of new railways were built, almost exclusively in EU15 Member States. The upgrade of existing railways covered almost 4,000 km, of which 60% were in EU15 countries, and the rest in EU12 countries. Trans-European Networks increased by more than 2,400 km of new roads (mainly in the EU12) and by more than 2,600 km of railways (mainly in the EU15). Once again, Poland was one of the countries that benefitted the most from this policy: the completion of the A1 motorway connecting Torun to Strykow, which represented a strategic link between the port of Gdansk, central Poland and the Czech border, is a good example.16

Almost 6 million additional people were served by new water projects (more than 60% in the four countries of Southern Europe). Almost 7 million additional people were served by wastewater projects (70% in Southern Europe). It is estimated that an annual reduction of energy consumption of almost 1,440 GWh and an annual reduction of greenhouse gas emission of around 830 kilotonnes of CO2 in public and residential buildings can be directly attributed to energy efficiency investments co-financed by ESI funds. Urban development and social infrastructure investments were diffused all over Europe. Examples of these projects are: the modernization of schools and colleges in Portugal (benefitting over 300 thousand youngsters); upgrading of training facilities in Spain, Poland, the Czech Republic and Lithuania; improvements in the healthcare system in Hungary; and construction and upgrading of schools in Poland (benefitting almost 2 million people).17

As for the programming period 2014–2020, the online European Commission portal provides some information on the most important public investments financed via the ERDF and CF.18 There are several “major projects” of transport, mainly in CEE countries. The largest is the rehabilitation of the railway line HU Border-Brasov, in Romania (more than €1.3 bn); while the works on the railway line No. 7 Warszawa Wschodnia Osobowa-Dorohusk, in Poland, amount to more than €750 mn. The first non-Eastern country to benefit from large EU financial means for transport investment is Greece, with the completion of the Metro Thessaloniki Main Line and the acquisition of trains for its use. All of these projects have the objective of promoting sustainable transport and removing bottlenecks. Major projects are underway also for the environment, such as the protection and rehabilitation of the coastal zone in Romania (€600 mn). Finally, other major projects are in the field of urban transport, such as the construction of the second metro line in Warsaw (€450 mn), the extension of the metro in Sofia (€370 mn), and the Metropolitan line of the Circumetnea railway in Sicily (€360 mn).

10.4. Regional Convergence and Spillovers

The European Cohesion Policy benefits all European regions in order to improve their competitiveness, with a strong focus on less developed areas. The effectiveness of the Cohesion Policy and its impact on growth has been widely analyzed in the literature (for instance, see the surveys by Fratesi 2016, and Pieńkowski and Berkowitz 2016). While the results of the papers using regional growth regressions are largely inconclusive regarding the impact of the Cohesion Policy on growth, the studies adopting a counterfactual impact evaluations technique show a clear positive impact of the Cohesion Policy on growth and other economic indicators (Pellegrini et al. 2013; Giua 2017; Becker et al. 2018).19

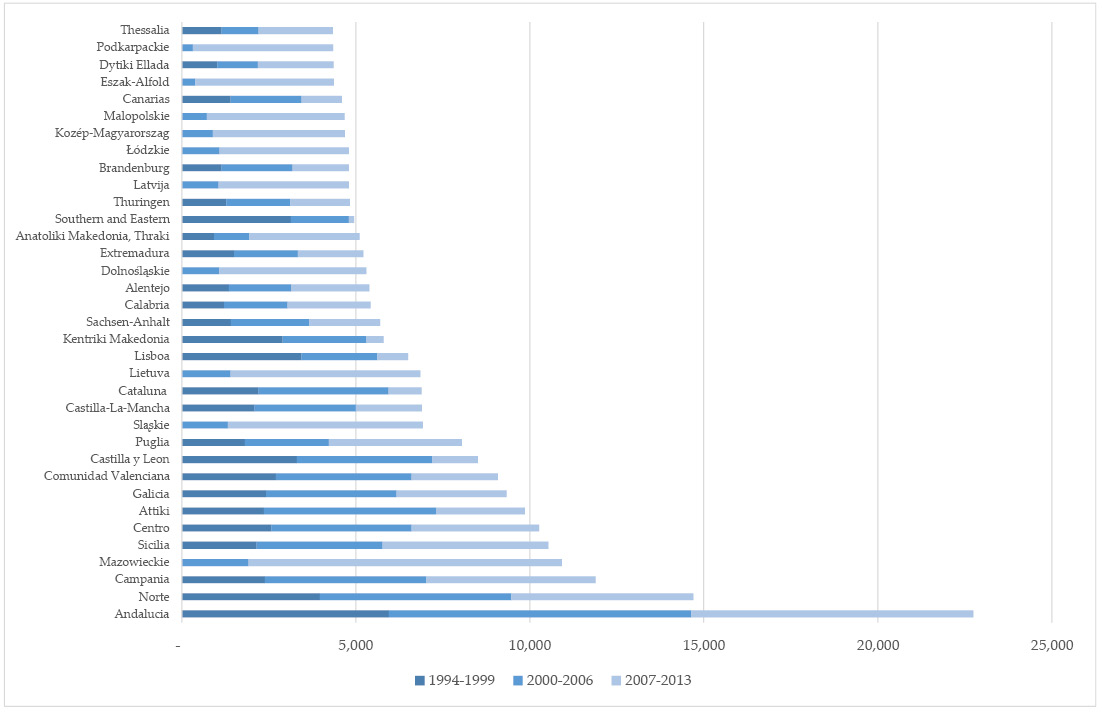

Fig. 2 Historic EU payments by NUTS-2 region and programming period (current euro prices)

Source of data: European Commission (https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/stories/s/Historio-EU-payment-data-by-region-NUTS-2-/47md-x4nq). Figure created by authors.

Figure 2 shows the European regions receiving most of the expenditure of the two funds between 1994 and 2013.20 Andalusia (Spain), Norte (Portugal), Campania (Italy), Mazowieckie (Poland) and Sicilia (Italy) are by far the main beneficiaries. Looking at the first thirty-five regions with higher expenditures, we find eight regions in Spain, seven in Poland, four in Greece, Portugal and Italy, three in Germany and two in Hungary. As already stressed, Eastern enlargement was crucial: investment in the region of Warsaw (Mazowieckie) in 2004–2013 is as large as investment between 1994 and 2013 in some large Southern European regions such as Campania and Sicilia (Italy), larger than in the region of Athens (Attiki). Several European regions including the capital city are large beneficiaries: together with Warsaw, Athens, Dublin, Lisbon, Madrid and Berlin in EU15, Budapest, Tallinn, Prague and Bucharest in EU12. In some regions, investments financed by ERDF and CF are quite large: twenty Central and Eastern European regions received more than €2 bn in 2004–2013. In Andalusia, between 2000 and 2013 investment in transport amounted to €5.1 bn and in urban and rural regeneration to €3.3 bn. In Portugal €2.1 bn were invested in social infrastructures in the Norte region, and €1.2 bn in the Centro. Investments in transport were larger than €2 bn in fifteen European regions: €5 bn in Spain and Poland, €2 bn in Greece, and €1 bn in Portugal, Italy and Latvia.

In large European countries with substantial economic internal divides (such as Germany, Italy and Spain) territorial concentration is important: in Germany the role of the Cohesion Policy increased, after reunification, in Eastern Landers; in Italy internal divides remained as such since the beginning of the Cohesion Policy; in Spain, regions in the northeast of the country, together with Madrid, improved their GDP per capita substantially compared to the EU average, exiting the rank of less developed regions and therefore seeing a strong decline of cohesion expenditures. Territorial concentration is also significant in countries such as Portugal, Greece and the United Kingdom. As far as Central and Eastern European Member States are concerned, the Cohesion Policy started covering the whole country; however, due to both their strong growth and the increase of internal divides, some important regions moved, and are moving, away from the group of less developed regions to intermediate or developed ones, with a decrease of cohesion expenditures: this is the case with all the regions containing capital cities.

10.5. Summary and Conclusions

In this final section, we want to briefly summarize the main findings of our analysis.

- The Cohesion policy is the European Union’s main investment policy, covering one third of EU budget. All regions and Member States are affected, but its action is substantially stronger in less developed ones.

- Until the big Eastern enlargement, main beneficiaries were in Southern Europe. Since 2004, most of the funds have been allocated in Central and Eastern European regions and countries that now receive substantially larger amounts.

- ERDF and CF expenditures finance around one sixth of European public investment. Their role increased in the last decade. In more recent years they finance 40% or more of total public capital expenditures in most Central and Eastern European countries, but their role is also significant in some Southern European countries, namely Greece and Portugal. They were able to mitigate the steep decline of public investment in the Member States that were hit by the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

- ERDF and CF expenditures are particularly important for transport infrastructures, both roads and rails, especially in Central and Eastern European countries. The investments in transport infrastructure financed by the Cohesion Policy are changing the accessibility of EU regions. In particular, many regions in Eastern Europe have significantly benefitted from improved accessibility as a result of the Cohesion Policy’s financing of transport infrastructure investments. Major investments are under way with the Cohesion Policy for 2014–2020.

- Environmental investments are important as well, even in Southern Europe; ERDF and CF also contribute to social (education, health, social services) and economic (IT, energy) infrastructures.

- The expenditures for the Cohesion Policy produce significant economic spillovers in favour of more advanced regions and countries in the EU.

- Implications of this analysis could be the following. If the low levels of public investment persist for a prolonged period, this will lead to a deterioration of public capital and negatively affect longer-term output. Many economists and research institutions advocate public investment spending to boost both internal demand and the potential output of the EU economy. It is, therefore, fundamental to pursue policies to encourage the growth-enhancing, long-term investments. There is little doubt that more public investment in the EU’s infrastructure is needed, especially in less developed regions and Member States.

- The Cohesion Policy has played and is still playing a major role in this framework. Its role within EU policies should be preserved and enhanced. In particular, it is important that the Cohesion Policy for 2021–2027 is funded with an adequate budget, for both Southern and Eastern less developed regions.

- The EU fiscal framework appears unable to foster public investment, even as a counter-cyclical fiscal stabilization tool. The issue of the incorporation of an appropriate “Golden Rule” in the EU fiscal framework — that is, the provision to exclude selected public investment from the budget deficit requirements — should be at the forefront of discussion about the EU’s future. A hypothesis could be to exclude investment co-financed by the Cohesion Policy from the Stability and Growth Pact deficit requirement.

References

ADE (2009) “Ex-Post Evaluation of Cohesion Policy Programmes 2000–2006 Co-Financed by the European Fund for Regional Development (Objectives 1 and 2) — Work Package 5b: Environment and Climate Change”, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/pdf/expost2006/wp5b_final_report_1.pdf

Applica (2012) “Ex Post Evaluation of the Cohesion Fund (Including Former ISPA) in the 2000–2006 Period — Work Package E”, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/pdf/expost2006/wpe_synth_rep.pdf

Barca, F. (2009) An Agenda for the Reformed Cohesion Policy: A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations: Independent Report Prepared at the Request of Commissioner for Regional Policy. Brussels: European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/policy/future/pdf/report_barca_v0306.pdf

Becker, S. O., P. H. Egger and M. von Ehrlich (2018) “Effects of EU Regional Policy: 1989–2013”, Regional Science and Urban Economics 69: 143–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.12.001

Berkowitz, P., E. Von Breska, J. Pieńkowski and A. Catalina Rubianes (2015) The Impact of the Economic and Financial Crisis on the Reform of Cohesion Policy 2008–2013, Regional Working Paper 03/2015. Brussels: European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/work/2015_03_impact_crisis.pdf

Di Comite, F., P. Lecca, P. Monfort, D. Persyn and V. Piculescu (2018) “The Impact of Cohesion Policy 2007–2015 in EU Regions: Simulations with the RHOMOLO Interregional Dynamic General Equilibrium Model”, JRC Working Papers on Territorial Modelling and Analysis 03/2018, https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/jrcsh/files/jrc114044.pdf

Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy (European Commission), Steer Davies Gleave (2010) “Ex Post Evaluation of Cohesion Policy Programmes 2000–2006 Co-Financed by the European Fund for Regional Development (Objectives 1 & 2) — Work Package 5a: Transport, Final Report”, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/expost2006/wp5a_en.htm

European Commission (2017), “Communication from the Commission. Ex-Post Verification of Additionality 2007–2013”, COM(2017) 138 final, Brussels, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/docs_autres_institutions/commission_europeenne/com/2017/0138/COM_COM(2017)0138_EN.pdf

Fratesi, U. (2016) “Impact Assessment of EU Cohesion Policy: Theoretical and Empirical Issues”, in Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU, ed. by S. Piattoni and L. Polverari (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), pp. 443–60, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715670.00045

Giua, M. (2017) “Spatial Discontinuity for the Impact Assessment of the EU Regional Policy: The Case of Italian Objective 1 Regions”, Journal of Regional Science 57: 109–31, https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12300

Immarino, S., A. Rodriguez-Pose and M. Storper (2017) Why Regional Development Matters for Europe’s Economic Future, Working Paper 07/2017. Brussels: European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/work/201707_regional_development_matters.pdf

Manzella, G. P. (2011) Una politica influente. Vicende, dinamiche e prospettive dell’intervento regionale europeo. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Molle, W. (2015) Cohesion and Growth, the Theory and Practice of European Policy Making. Abingdon: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315727332

Naldini, A., A. Daraio, G. Vella, E. Wolleb and R. Römisch (2018) “Research for REGI Committee — Externalities of Cohesion Policy”, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/617491/IPOL_STU(2018)617491_EN.pdf

Panetta, F. (2019) “Lo sviluppo del Mezzogiorno: una priorità nazionale”, Intervento del Direttore Generale della Banca d’Italia, Foggia, 21.9.2019, https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/interventi-direttorio/int-dir-2019/Panetta_21_settembre_2019_Foggia.pdf

Pellegrini, G., F. Terribile, O. Tarola, T. Muccigrosso and F. Busillo (2013) “Measuring the Effects of European Regional Policy on Economic Growth: A Regression Discontinuity Approach”, Papers in Regional Science 92: 217–33, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5957.2012.00459.x

Piattoni, S. and L. Polverari (eds.) (2016) Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715670

Pieńkowski, J. and P. Berkowitz (2016) “Econometric Assessments of Cohesion Policy Growth Effects: How to Make Them More Relevant for Policymakers?”, in EU Cohesion Policy: Reassessing Performance and Direction (Regions and Cities), ed. by J. Bachtler, P. Berkowitz, S. Hardy and T. Muravska (Abingdon: Routledge), pp. 55–68.

Prota, F. (2016) “L’effetto dell’austerity sulle politiche di sviluppo nei Paesi dell’Unione europea”, in Le politiche di coesione in Europa tra austerità e nuove sfide, ed. by M. Carabba, R. Padovani and L. Polverari (Rome: Quaderni SVIMEZ), pp. 57–70, http://lnx.svimez.info/svimez/wp-content/uploads/quaderni_pdf/quaderno_47.pdf

Rodrik, D. (2012) “Why We Learn Nothing from Regressing Economic Growth on Policies”, Seoul Journal of Economics 25: 137–51.

Stöllinger, R. (2016) “Structural Change and Global Value Chains in the EU”, Empirica 43(4): 801–29, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9349-z

Viesti, G. (2019) “The European Regional Development Policies”, in The History of the European Union: Constructing Utopia, ed. by G. Amato, E. Moavero-Milanesi, G. Pasquino and L. Reichlin (Oxford: Hart Publishing), pp. 385–97.

Viesti, G. and F. Prota (2008) Le nuove politiche regionali dell’Unione Europea. Bologna: Il Mulino.

WIIW and ISMERI Europa (2015) “Ex Post Evaluation of Cohesion Policy Programmes 2007–2013, Focusing on the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Cohesion Fund (CF) — Work Package 13, Geography of Expenditures’, http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/pl/policy/evaluations/ec/2007-2013/

1 Dipartimento di Economia e Finanza, Università di Bari “Aldo Moro”.

2 Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, Università di Bari “Aldo Moro”.

3 Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche, Università del Salento.

4 Regional Policy is delivered through three main funds: the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund (ESF) and the Cohesion Fund. Together with the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF), they make up the European Structural and Investment (ESI) Funds. The ERDF provides financial support for the development and structural adjustment of regional economies: public investments, R&D and contributions to private investments; the ESF is the main tool for promoting education, employment and social inclusion in Europe; the Cohesion Fund contributes to environmental and transport investments.

5 The dataset is available in the ESIF Open Data platform (https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/Other/Historic-EU-payments-regionalised-and-modelled/tc55-7ysv).

6 The dataset is available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/evaluations/data-for-research/

7 This paragraph is largely based on Viesti (2019).

8 All the other European regions were included in a new Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective, for which €39 bn were allocated. The decision to go beyond the old logic of “zones” in Objective 2 had a very important political significance. Regional Policy was no longer merely a policy to facilitate the growth and convergence of the weak regions, but rather a development policy for the entire European Union.

9 Indeed, the Central and Eastern Europe countries benefited also from the EU’s pre-accession structural support.

10 The verification of additionality for the 2007–2013 programming period shows that the average annual “structural” spending was on average some 1% lower than initially estimated (European Commission 2017). There are however significant differences across Member States. For example, the actual structural spending for 2007–2013 was 35% lower than the ex-ante baseline in Greece. The variation is over 25% in Italy and between 10 and 20% in Hungary, Lithuania and Portugal.

11 Substantial increases also occurred in Italy (from 48% to 65%), from 50% to 72% in the less developed regions, and in Portugal (from 63% to 74%).

12 The different disaggregation in policy areas shown in the Tables 2 and 3 is due to the different classification adopted in the studies from which the data have been collected.

13 The statistics herein rather underestimate the actual outputs in terms of new or renovated infrastructure, due to some features of the reporting mechanism that asked Member States to keep track of the progress to the EU Commission. However, this data is the most reliable since it comes from official publications and documents of the EU.

14 The Portuguese region of Norte started with around 40% of population served by wastewater treatment plants in 2000, and ended up with more than 55% in 2006. Also in the Italian region of Lazio, a considerable improvement occurred, as the percentage of population served by secondary and tertiary treatment rose from around 22% in 1999 to around 30% in 2006. On average, the share of population connected to wastewater treatment rose in the period 2000–2009 from 85 to 88 in the EU15 (although with significant lower percentages for countries like Ireland, Greece and Portugal) and from 46 to 55 in the EU12.

15 One example is the Bulgarian Trakia motorway project, linking the southeastern cities of Stara Zagora and Karnobat: finalized in 2013, it completed the route from Sofia to the Black Sea port of Burgas.

16 See the reports available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/evaluations/ec/2007-2013/#6

17 See the reports available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/evaluations/ec/2007-2013/#10

18 See the dataset available at https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/2014-2020/ESIF-2014-2020-ERDF-CF-Major-Projects/sjs4-8wgj/data

19 Doubts over the conclusions that are frequently inferred from the results obtained from growth regressions have been formulated by Rodrik (2012).

20 Totals must be read with caution because the figures for the different programming periods are in current euros.