2. Native Song and Dance Affect in Seventeenth-Century Christian Festivals in New Spain1

© Ireri E. Chávez Bárcenas, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0226.02

Introduction

Ceremonial song and dance traditions were essential for Nahua cultures at the time of European contact.2 A wide variety of chronicles contain descriptions of Nahua dancing rituals written by clerics, conquerors, natives, and travelers. Although the terminology is not always consistent, the emphasis on the participants’ elegant attire, the sophisticated coordination between drummers, singers, and dancers, and the mesmeric collective effect that could last for hours reveal the most impressive aspects of such performances for viewers and readers alike during the first hundred years after the Conquest.3 But this is also the period in which the Catholic Church pondered the use of the senses for the promotion of Christian devotion, and the preservation of native uses and customs were considered essential for a wholehearted engagement with the Catholic faith, especially for certain members of the religious orders in charge of the evangelization of the native population.4 Throughout the sixteenth century, trained drummers, singers, and dancers were encouraged to participate in religious ceremonies organized by the mendicant orders in Indian settlements, although the content had to be adapted for the new Christian context. Efforts to combine the local idiosyncrasy, language, and song and dance traditions with doctrinal instruction were led by Bernardino de Sahagún and a selected group of Nahua scholars who collected, translated, adapted, and transcribed hundreds of song texts.5

This practice was gradually incorporated into the main public festivals in most urban centers in New Spain. In the early seventeenth century the Nahua song and dance tradition was emulated in other devotional genres to represent the native population, including villancicos and sacred dramas. Only a few written examples survive, but the distinctive depiction of Indian characters as devout neophytes and humble workers — especially compared to other characters in similar genres — is particularly meaningful considering the intense debate over the abusive practices of Indian labor, which called into question the legitimacy of the Iberian oversees expansion.

This essay explores a specific poetic and song tradition that survives in early seventeenth-century villancicos and other literary genres. These works arguably draw on Nahua song and dance ritual practices as well as the century long tradition of repurposing them for the major festivals of the Catholic Church. To establish the relationship between Nahua performative rituals and these musico–poetic renderings I revise the various records written by chroniclers, ministers, and travelers describing ceremonial songs and dances in the Nahua region, and analyze the Catholic Church’s interest in using Nahua’s expressive culture as a tool for conversion.

I focus on four villancicos written in Nahuatl for the feast of Christmas in Puebla de los Ángeles from 1610 to 1614 by the Cathedral’s chapelmaster Gaspar Fernández. These songs survive with their music, and together with two Marian songs found in Códice Valdés, constitute the principal source of devotional music written in Nahuatl.6 In Fernández’s villancicos, Indians are represented as humble biblical shepherds in the Nativity scene — an image rooted in a post–Tridentine pastoral tradition that promoted the spiritual values of humility, innocence, and servitude, especially during the Christmas season. I demonstrate, however, that the emphasis on poverty and suffering became an emblem of sorts for the native population in the Novohispanic Christian song.

Studies of early music in Spanish America have interpreted the use of dialects in ethnic villancicos as an instrument of power solely designed to impose a hierarchical social order. Thus the learned elite, who arguably wrote and spoke the hegemonic version of Spanish, is perceived as superior to those who spoke a ‘deficient’ or ‘deformed’ Spanish.7 The villancicos analyzed in this essay, however, provide a new perspective, because they show that the Spanish elite could also be portrayed negatively. Similarly, a broader examination about the use of Nahuatl in devotional songs show theological motivations that have not been accounted for in previous studies. Specifically, this research demonstrates that the religious clergy used native languages to provide familiar sounds to the native population and used images of peasants, workers, and the downtrodden that could better sympathize with the humility and suffering of Christ. From this perspective, Indian workers served as better models for Christian piety than did the Spanish elite.

Nahua Song and Dance Rituals

Detailed descriptions of Nahua song and dance rituals survive in the written record from the early period after the conquest. An early example is included in a chapter of the monumental Historia General de las Indias (1552) by the armchair traveler Francisco López de Gómara. Although he never crossed the Atlantic, he describes in great detail the type of dances with which the Emperor Moctezuma entertained the people of the city in the courtyard of his own palace. According to López de Gómara — or to his informants — participants formed concentric circles in strict hierarchical order and sang and danced to the beat of the teponaztli and the huéhuetl.8 These wooden cylindrical drums were essential to ritual ceremonies. Each drum produced two distinct pitches that, combined with orally learned rhythmic patterns, dictated dance movements as well as the intonation, pitch, and rhythm of the text. They were performed by trained celebrants who were strategically placed at the center, so that dancers could replicate the drum beat with a gourd rattle called ayacachtli. The circular arrangement also facilitated the participation of hundreds and sometimes thousands of people, who followed the instructions of two trained singers/dancers who coordinated the rhythm, style, and character of every performance. Their essential role is explained in López de Gómara’s narrative:

[…] because if they sing, everyone responds, sometimes frequently, sometimes not so often, depending on what the song or the romance requires; which is similar here [in Castile] as it is elsewhere. Everyone follows their rhythm [and] they all raise or lower the arms, or the body, or only the head at the same time, and everything is done so graciously, with so much coordination and skill that no difference is perceived from one another, so much so that men are left dazzled. They begin with slow romances playing, singing, and dancing very quietly, which seems very solemn, but when they lighten up they sing villancicos and other joyful songs and the dance is enlivened with more vigorous and faster movements.9

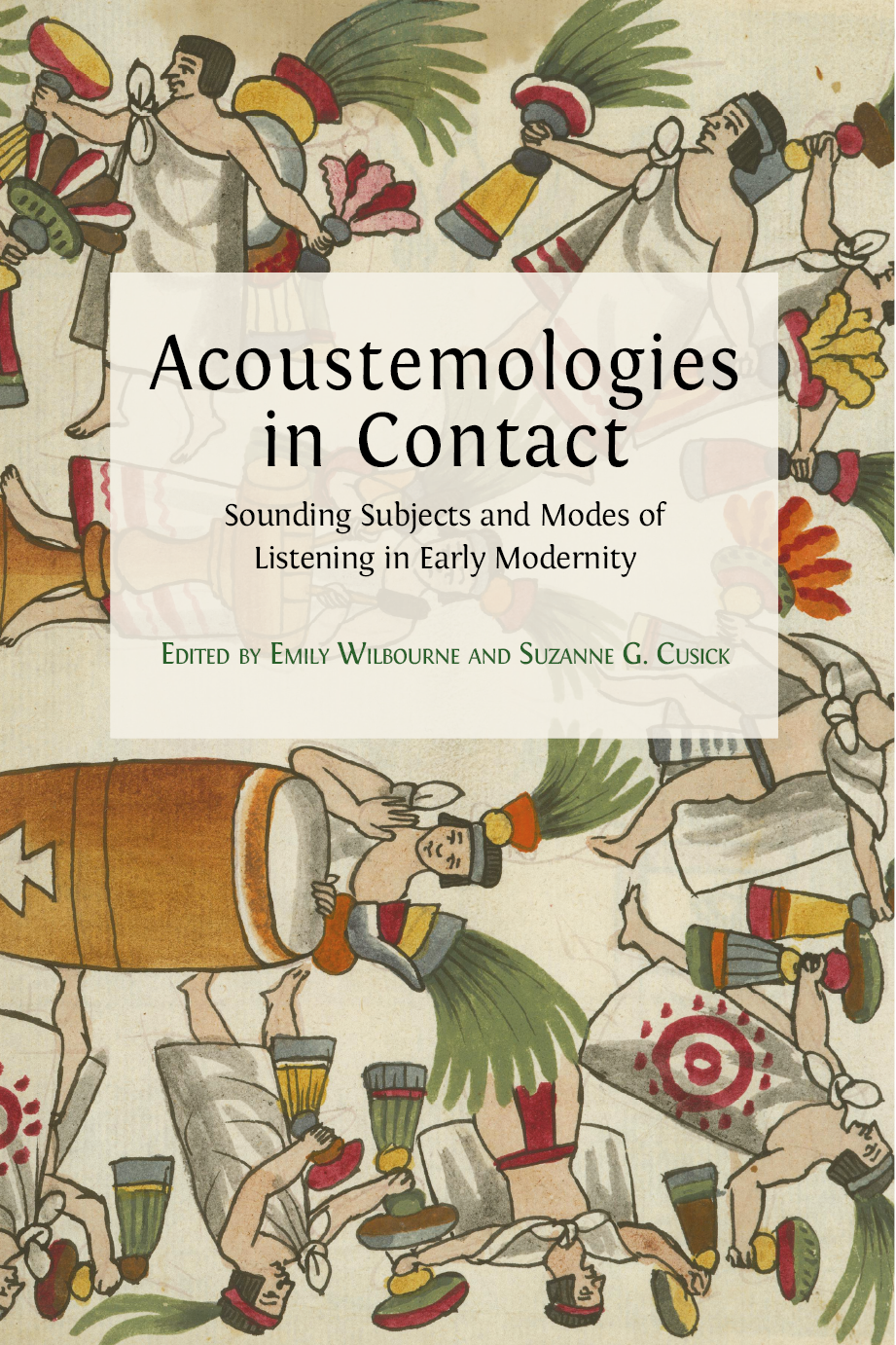

Details in this record are consistent with other descriptions of Nahua dancing rituals written by both local and foreign eyewitnesses. Juan de Tovar, for instance, a Jesuit priest born in New Spain, mentions that the elder elite danced and sang from the first circle around the ceremonial drums ‘with great authority and soft rhythm’; all the while young dancers taking turns by pairs entered the circle and improvised with lighter movements and greater jumps.10 Tovar’s chronicle is accompanied by dozens of watercolors, one of which reproduces this very scene, showing the two drummers at the center, and the first row of participants made up of members of the ruling elite dancing in precise coordination, wearing rich dresses and elaborate feathered ornaments. The image also shows dancers shaking ayacachtlis, which according to the Spanish Jesuit Andrés Pérez de Ribas echoed the rhythm of the teponaztli.11

The rich descriptive materials provided in these chronicles are crucial for the analysis of poetic and musical attributes of devotional songs and religious lyric poetry that evoke aspects of Nahua music-making. These descriptions typically focus on the central role of ceremonial instruments and the close relationship between musical rhythm, dance steps, and other movements. These details, I argue, prevailed in the imaginary of seventeenth-century poets and musicians and informed evocative representations of the native population participating in Christian festivals in sacred songs and other dramatic genres.

Fig. 2.1 ‘The manner in which the Mexicans dance’. Juan de Tovar, Historia de la venida de los indios (Ms., c. 1585), f. 58r. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Language and Expressive Culture as Tools for Conversion

Nahuatl was the most spoken language in Central Mesoamerica in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It was the dominant language before the conquest and continued to function as a lingua franca among native peoples long afterwards, which is significant considering the extensive linguistic diversity of the area.12 The importance that friars gave to language for religious conversion also contributed to the rapid systematization of Nahuatl and other native languages into Latin characters and the publication of grammars, dictionaries, doctrines, and other language manuals in the sixteenth century. Linguist Claudia Parodi has shown that Nahuatl was used with greater or lesser proficiency in everyday life by non–native speakers (i.e. mestizos, criollos, Blacks, and Spaniards) and by native and non–native writers in a wide variety of literary genres, including printed doctrines, catechisms, confessional manuals, sermon collections, natural and philosophical treatises, and many other manuscript materials such as chronicles, notaries records, and poetic collections.13 In short, the society living in New Spain is presented to us as primarily multilingual and with ample opportunities to experience the Mexica language in oral and written forms. This is confirmed by the Spanish Franciscan missionary Gerónimo de Mendieta, who describes the high fluency in Nahuatl in New Spain in the late sixteenth century, without missing the opportunity to compare the language to Latin in order to justify its use in erudite treatises:

This Mexican language [Nahuatl] is the main [language] that runs through all the New Spanish provinces since here there are many different languages. […] But there are interpreters everywhere who understand and speak Mexican [Nahuatl] because this is the one that runs everywhere, just like Latin does in all the European kingdoms. And I can truthfully confirm that the Mexican one is no less elegant and curious than Latin, and I dare to say that the former is even more accurate for the composition and derivation of terms and metaphors.14

As shown by Mendieta, Nahuatl was also prevalent among bilingual and trilingual speakers in New Spanish provinces and thus became optimal to provide religious instruction in Indian settlements. In the early seventeenth century, for instance, the bishop of Tlaxcala, Alonso de la Mota y Escobar — whose episcopal seat was located in the city of Puebla — was a fluent Nahuatl speaker, and every time he visited an Indian parish he insisted in administering the sacraments in Nahuatl.15 His concern for the language in which Indians received the sacraments is explicit in the records of his pastoral inspections where he consistently includes information about the primary language spoken in every settlement and complains about the poor quality of the doctrine when ministers are unable to communicate with locals in their own language. Likewise, when the native language spoken in a given locality is not Nahuatl, he specifies whether listeners understand Nahuatl or if there are local interpreters who can translate his preaching.16 What is interesting for this study, however, is not so much the use of Nahuatl during the administration of the sacraments in pueblos de indios, but its use in other paraliturgical genres that transcended the marginal confines of Indian settlements and Indian parishes to be introduced at the center of public festivals in most urban centers in New Spain. Such is the case of the Nahua song and dance tradition, which was actively promoted by Franciscan and Jesuit ministers during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Missionaries indicated a strong interest in supporting the local expressive culture not so much for the possibility to fully communicate the principles of the church with native-speakers, but for the potential they saw in the cultivation of the Christian faith. The admiration for local performative customs is repeatedly expressed — if ever so cautiously — in chronicles written by the Franciscan friars Toribio de Benavente (better known as Motolinía) and Sahagún. Both were particularly attracted by the similarities they found — at least to their eyes and ears — with certain Christian rituals, and wanted to find adequate methods for the appropriation of these practices.

Motolinía’s close interaction with the native population and his profound knowledge of Nahuatl gave him a broader perspective compared to other writers who described these performances. He is seemingly the only chronicler able to articulate the difference between the two main dancing genres, a recreational one called netotiliztli (baile de regocijo) enjoyed by the people and the nobility alike in public or private gatherings, and a more virtuous one called macehualiztli (danza meritoria) reserved for more solemn occasions. According to Motolinía the macehualiztli was one of the main ways in which locals ‘solemnized the feast of their demons, honoring them as gods’.17 The performance included songs of praise for gods and past rulers, which recounted their intervention in wars, victories, and other deeds. Such activities reinforced the collective memory with texts that were learned by heart and reenacted in public performances. Motolinía’s impression of the intense bodily experience that participants had during day-long rituals is recorded in the following passage:

In these [festivals] they not only called, honored, or praised their gods with canticles from the mouth, but also from the heart and from the senses of the body, for which they made and used many mementos (memorativas), such as the movements of the head, legs, and feet, or the use of the whole body to call and to serve the gods. And for all of the laborious care they took in lifting their hearts and their senses to their demons, for serving them with all the qualities of the body, and for all the effort in maintaining it for a full day and part of the night they called it macehualiztli, which means penance and merit.18

This testimony shows that while opposing the local belief system, Motolinía is empathetic to these ritual practices, especially when he compares them to Christian singing traditions — in fact, the terminology Motolinía uses to describe the songs’ form and function or the social structures around these performances clearly reflects his formative experience with court and church music making in Castile.

But macehualiztli also posed a threat for church and royal authorities, not only for the evident remembrance of a non-Christian past inherent in the genre, but because its ‘obscure figurative language’ made it impossible to understand or to control, even for Nahuatl specialists such as Sahagún or Dominican friar Diego Durán.19 As a result, the performance of native dances and cantares was prohibited unless they were taught by friars, especially those in honor of ‘old gods’ or ‘devils’.20

Although friars were generally more interested in using Nahua’s expressive culture than proscribing it, they had to understand the local customs first. Motolinía, for instance, insists that if Nahuas were already familiar with the tradition of composing new canticles for their gods, the provision of new Christian hymns and songs for the one true God and for ‘the many victories and wonders on Heaven and Earth and Sea’ was essential, but he considered himself unprepared to take on such a specialized task.21

Sahagún, also impressed by the ‘mystical’ effect of pre-Hispanic ritual dances, tries to acknowledge the influence of the evangelization process in his own description, stating that, although Indians essentially continued doing the same activities that they had engaged in during pre-conversion performances, they had ‘corrected [enderezado] their movements and customs according to what they are singing’. In the same paragraph however, he added an anxious note to the margin that reads: ‘[i]t is the forest of idolatry that is not yet logged’, which explains his resolute attempt to continue reforming such practice.22

For Sahagún, a close collaboration with native scribes and painters was fundamental in order to document details about local traditions which were not entirely transparent to Western missionaries. He led collective projects dedicated to the compilation and transcription of Nahua song-texts from central New Spain resulting in two important collections: Cantares mexicanos and Romances de los señores de la Nueva España. Although these poems were primarily conceived to be sung — and sometimes danced — no musical notation or other choreographic information is included, which leaves performing details to the imagination of readers and researchers.23 Similar to contemporary Iberian song-text collections, these anthologies represent a deliberate attempt to preserve a song and dance tradition that until then had been transmitted orally, although in the Spanish American case this effort only represented the first step of a much longer intervention into the genre, since the ultimate goal was to understand, control, and replace its content and meaning.24

The second step of this reformative process was the creation of a new repertoire of song-text materials for the ceremonial dances performed in Christian festivals, exemplified by Sahagún’s ambitious collection of song-texts in Nahuatl, published in Mexico City in 1583 under the title Psalmodia Christiana. Sahagún describes the volume as ‘Christian doctrine in the Mexican language ordered in songs or psalms so that Indians can sing in the areitos they perform at churches’.25 The volume itself contains 333 texts for the main festivals of the liturgical calendar.

Many questions remain about the ways in which these changes were implemented in different communities or how local traditions were specifically affected. The scarce surviving information reveals that Sahagún obtained permission from the highest viceregal authorities to distribute his printed collection among Indian settlements, although it is hard to estimate its effect because no further documentation survives. Spanish Jesuit José de Acosta explains that members of the Society of Jesus ‘tried to put things of our faith into their way of singing [… and] translated compositions and tunes, such as octosyllabic verses and songs from romances and redondillas […] which is truly a great [medium], and a very necessary one to teach this people’.26 A chronicle written by Pedro Morales about a procession organized by the Company of Jesus in Mexico City in 1578 offers a clearer illustration of some of the mechanisms followed for the Christianization of Nahua ceremonial practices. According to Morales, a group of children garbed in elegant ceremonial attire sang and danced the song ‘Tocniuane touian’, which was written by a member of the local Jesuit colegio.27 Morales explains that (1) ‘the music for the dance consisted of a four-voice polyphonic setting harmonized in the Spanish style’; (2) the voices were accompanied by an ensemble of flutes and a teponaztli; (3) the text was written to praise St. Hippolytus and other saints; (4) and clarifies that although the children sung in their own language, the text ‘followed the Castilian meter and rhyming style’.28

Morales’s description offers a glimpse into the visual and sounding effects created by combined Nahua and Spanish ritual practices. It is possible that the teponaztli provided not only the sound and affect that was traditionally associated with ceremonial performative practices, but also the necessary metric patterns or rhythmic structures that guided the dancers’ movements. The four-voice polyphonic texture and regular phrasing structure might have offered the familiar sound of devotional singing genres in the vernacular, not only for those who had recently immigrated from the Iberian Peninsula but for locals who were already immersed in the varied musical practices of the post-Tridentine Catholic Church. And perhaps most importantly, the new host of Christian characters offered alternative ontological narratives to older beliefs. In fact, Morales’s emphasis on the panegyrics to St. Hippolytus is particularly striking because the saint had not only become the patron of Mexico City but also the very emblem of the Spanish Conquest since Hernán Cortés took control over Tenochtitlan (the capital of the Mexica empire) on the saint’s feast day.29 This narrative offers the perfect example of the new type of hybrid native tradition embedded with a Spanish Christian message: according to Motolinía’s perception of the two distinct song and dance genres, the children’s performance fall into the macehualiztli tradition as a song of praise that celebrated the divine intervention of St. Hippolytus given to Hernán Cortés in a battle against the Mexica leader, Cuauhtémoc, which enforced a concise and belligerent testimony of Christian righteousness and power, one that was reenacted and remembered publicly.

Villancicos en Indio

An important aspect for these hybrid practices was the preservation of specific performative elements that audiences could immediately associate with Nahua traditions. These points of reference appear in devotional songs and other lyric narratives that dramatize the participation of the native community in Christian religious rituals. The large collection of villancicos by Gaspar Fernández shows that elements of Nahua musicality discernible in sixteenth-century chronicles were absorbed into a subgenre of villancicos with texts in Nahuatl, identified by the author as ‘villancicos en indio’. In these songs, Nahuas are portrayed as humble workers sympathizing with the poverty and suffering of Christ. I argue that this narrative served to present the native population as Christian models for the Novohispanic society because their situation was more closely related with that of Christ, which casts a new light on the assumed negative representation of people from distinct regional or ethnic origins in the villancico genre.

Fernández’s villancicos also show that the elements that shaped the Nahua-Christian song described by Morales in 1578 were current in other parts of the viceroyalty at the turn of the century, however unlike the processional piece arranged by the Society of Jesus for native singers and dancers, these songs were prepared and performed by the members of the music chapel of a major cathedral institution.30 Fernández was the chapelmaster of the Cathedral of Puebla, so he occupied the most prestigious music position in Puebla and the second most important in the viceroyalty.31 Among the most important duties of chapel masters in Hispanic cathedrals was the provision of new sets of villancicos for the major liturgical festivals of the year, such as Christmas or Corpus Christi. Fernández is also the author of the Cancionero Musical de Gaspar Fernández, one of the largest collections of villancicos that survive from seventeenth-century Spanish territories.32

Villancicos, essentially devotional songs in the vernacular, were crucial to religious and civic festivals in the early modern Hispanic world. They were integrated into the customaries of Hispanic cathedrals, court chapels, and other religious institutions for the major feasts of the year, replacing or adding musico-poetic material to antiphons or responsories during the Mass, the Office Hours, or during processions.33 The villancico was the only music genre performed during the liturgy where people could hear newly composed texts in the vernacular glossing the biblical narrative. The vast majority of villancicos were written in Spanish, but a significant number were also in conventional dialects to represent characters from diverse regional or ethnic origins, such as Basques, Portuguese, or Blacks, and occasionally included the use of native dialects to represent Indian natives in the New World.34

Gaspar Fernández’s collection includes four villancicos for Christmas written in Nahuatl and mestizo, a mixed dialect that imitates the way in which Nahuatl speakers pronounced Spanish. It would be speculative to propose possible conventions for the ‘villancico en indio’ subgenre with this limited number of pieces, however there are certain poetic and musical elements that relate suggestively to descriptions documenting the appropriation of Nahua performative rituals by the Novohispanic Catholic Church. The versification, for instance, shows the same procedure described by Jesuits Acosta and Morales where the texts are written in Nahuatl but follow the Castilian style of eight-syllable lines, in this case using assonant rhyme with enclosed or alternate rhyme schemes (i.e. abba and abab).35 In three cases the text closes the first stanza with the octosyllabic elocution of two ‘alleluias’ in its mestizo form ‘aleloya, aleloya’.

Table 1 Meter and rhyme schemes in Fernández’s ‘villancicos en indio’. The coplas are not included in this table.36

|

Text |

M |

R |

Translation |

|

Jesós de mi gorazón, |

8 |

a |

Jesus of my heart, |

|

no lloréis, mi bantasía. |

8 |

b |

do not cry, my fantasy. |

|

tleycan timochoquilia |

8 |

b |

Why are you crying? |

|

mis prasedes, mi apission. |

8 |

a |

My pleasure, my affection. |

|

Aleloya, aleloya |

8 |

x |

Alleluia, alleluia. |

|

Ximoyolali, siñola, |

8 |

a |

Rejoice, my lady, |

|

tlaticpan o quisa Dios, |

8 |

b |

because on earth God has been born |

|

bobre y egual bobre vos, |

8 |

b |

poor and equally poor like you, |

|

no gomo el gente española. |

8 |

a |

not like Spanish people, |

|

Aleloya, aleloya |

8 |

x |

Alleluia, alleluia. |

|

Tios mío, mi gorazón. |

8 |

a |

My God, my heart, |

|

Mopanpa nipaqui negual; |

8 |

b |

because of you I am happy, |

|

amo xichoca abición |

8 |

a |

do not cry my affection. |

|

que lloraréis, el macegual. |

8 |

b |

because you will make the humble Indian cry. |

|

Xicochi, xicochi, conetzintle, |

11 |

a |

Sleep, sweet baby, |

|

ca omizhuihuijoco in angelosme. |

11 |

a |

because the angels have come to lull you, |

|

Aleloya, aleloya. |

8 |

x |

The songs also share certain narrative and thematic qualities. All of them are monologues written in the first person singular and each one presents the main character taking part in the biblical passage of the Adoration of the Shepherds, although the shepherds in this Nativity scene are Indian natives. The central subject of ‘Jesós de mi gorazón’ and ‘Tios mío, mi gorazón’ is the weeping Child. Both refer to the child as ‘mi gorazón’ (my heart), a term that is paired with mestizo variants of ‘afición’ (or affection). In the coplas of ‘Jesós de mi gorazón’ the shepherd tries to distract the Child showing him the mule and the ox in the stable, and seemingly ignoring divine providence he asks, ‘What is your affliction, my love? / Why are you crying?’ or insists ‘I do not know why you suffer’. Then the shepherd expresses deeper fondness for the Child comparing him to a beautiful rose (rosa), a pearl (noepiholloczin), with jade (nochalchiula), and a lily flower (noasossena). The symbolism of these objects seems obvious, especially if compared to Nativity paintings from the same period that interpret the Child’s tears as an anticipation of his pain and suffering on the Cross: lilies, which were traditionally associated with the Virgin, function as an emblem of chastity and purity, but also of Christ’s resurrection; pearls were used to symbolize the Virgin’s milk from her breast as well as her tears at the Crucifixion; and roses were prominently displayed to represent Christ’s blood in the Passion.37 In the same context it is possible that jade — which was a fundamental component in Mexica burial artifacts and sacrificial offerings — could have been associated with the sacrifice of Christ.

The music of Fernández’s villancicos reflect the current stylistic procedures of the genre, which is somewhat hinted in Morales’ description. Villancicos are typically scored for four, five, or more voices, offering bold contrasting sonorities between the estribillo (refrain) written for all voice-parts, and the solo or duo texture for the coplas (verses). The cathedral’s minstrels joined the vocal ensemble for the performance of villancicos. Upper voices were typically doubled by shawms and sackbuts, the lower voice was doubled with the bajón, or dulcian, and the continuo ensemble could include organ, harp, and vihuela. There is no evidence for the use of native percussion instruments by church musicians in seventeenth-century New Spain.

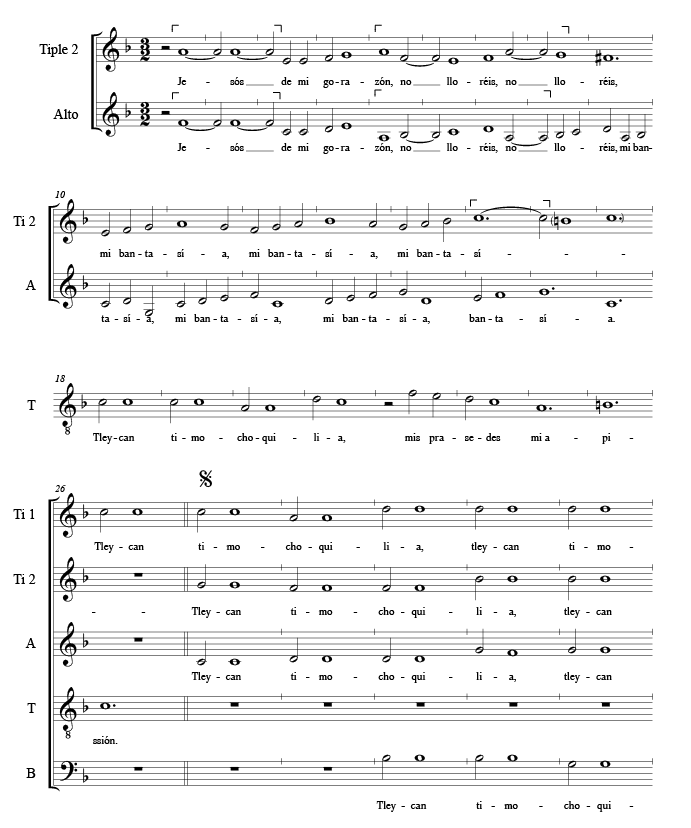

Fernández used various compositional devices to enhance the narrative, such as the selection of meters or modes, the use of syncopations, hemiolas, dance-like rhythms, as well as alternate polyphonic and homophonic textures. ‘Jesós de mi gorazón’ is set for five voices in triple meter with a final on F. It opens with a melodious duet for the Tiple 2 (second treble) and Alto parts. The clear and sustained enunciation of the name ‘Jesós’ — to whom the Indian speaks directly — and the soothing effect of parallel thirds and sixths is interrupted by a sharp sonority for the closing phrase ‘no llorés’ (do not cry), providing a distinctive effect for the Indian’s plea. Then, a brief ascending sequence by step for the reiteration of the words ‘mi bantasía’ suggests the improvisatorial character of the Spanish instrumental fantasía. But the most prominent element in the context of this essay is the insistent short-long rhythmic pattern and the static melodic contour built around the note c which dominate the second part of the estribillo; this section is developed in imitative polyphony and repeats after each copla. The sudden shift to a homorhythmic pattern sung by all voices provides a sonorous contrast for the only verse that is fully written in Nahuatl, and it is quite possible that here Fernández tried to emulate the rhythms associated with ceremonial dancing patterns, the intervallic possibilities of the teponaztli, and the effect of a collective performance through the successive expansion of the initial phrase, as sung by the Tenor, to all voices in imitation.

The image of an Indian moved by the tears of the Child appears again in ‘Tios mio, mi gorazón’. The main character is described as a macehual, which in Nahuatl means a humble Indian laborer. In this scene, listeners can imagine a poor Indian contemplating the Child in the manger and trying to soothe him with his words. The Indian tells the Child that, although he is full of joy at the infant’s birth, the child’s tears will make him cry. In this case the central verse (‘do not cry my affection’) is set with a distinctive descending chromatic tetrachord in the minor mode, a musical gesture associated with the lament. This motive is successively imitated by each voice in the polyphonic section, suggesting not only the movement of tears rolling down from the child’s eyes, but also the character’s impossibility to restrain himself from feeling such a tender sorrow.38

Example 2.1 ‘Jesós de mi gorazón’, mm. 1–31. [Villancico en] mestizo e indio a 4 [1610], AHAAO, CMGF, ff. 58v–59. Although the original text was written in chiavette clefs, this excerpt was not transposed down a fourth in consideration to conventional vocal registers.

Christ’s tears in the manger were symbolically associated with his suffering in the passion in order to encourage a deeper reflection about the liturgical meaning of the Nativity. This theology is clearly reflected in the characters’ compassionate attitudes shown in ‘villancicos en indio’, which contrast radically with the rustic or popularizing portrayals of other characters from diverse regional or ethnic origins, also known as ‘villancicos de personajes’. The disparity between Indians and Blacks is particularly notorious since ‘villancicos en negro’ or negrillas are characterized by humorous depictions of African subjects celebrating the birth of Christ with much noise and vigor and a limited dominion over their language, their voice, or their body.39 It should be said that other subgenres of ‘villancicos de personajes’ also make use of literary conventions for the creation of comic stereotypes, representing Gypsies or Muslims as dishonest, Basques or Galicians as ingenious and rustic, or Portuguese as treacherous or narcissistic. Nonetheless, the intimate and contemplative nature of ‘villancicos en indio’ allowed for the portrayal of Indians as melancholic neophytes, recognized for their empathy, innocence, and poverty.

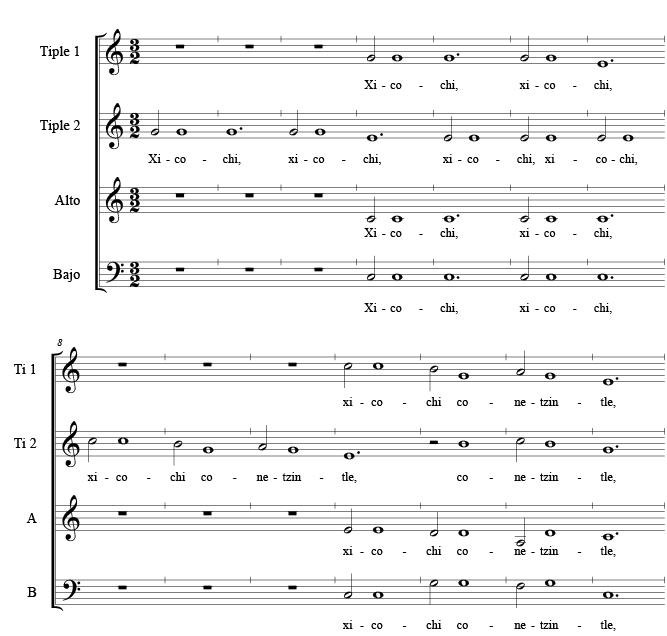

This is evident as well in the lullaby ‘Xicochi conetzintle’ set to a text in Nahuatl that translates ‘Sleep, sweet baby / because the angels have come to lull you, / Alleluia, alleluia’. This exceptional text does not conform with the octosyllabic verse-line that was identified in early-modern Spanish poetry as ‘verses of lesser art’. Instead, as noted by linguist Berenice Alcántara Rojas, the text follows the structure and syntax of ‘classical Nahuatl’ as used by friars and erudite Indians for the composition of Christian texts.40 Such treatment of the language provides yet another element to distance Indian shepherds from the typical comic or rustic character of ‘villancicos de personajes’.

In setting the text, Fernández maintained the distinctive short-long rhythmic pattern noted earlier, here sung homorhythmically from the beginning to the end. The setting for four voices opens with the Tiple 2 introducing the word ‘xicochi’ (sleep) with a half note, a whole note, and a dotted whole note in triple meter (C3). The other three voices repeat this pattern in elision creating a soothing effect that results from the combined sounds of ‘chi’ and ‘xi-co’ and vice versa (mm. 4–7). This is particularly effective with the pronunciation of the fricative consonant ‘xi’ as ‘shi’ every downbeat which together with the short-long rhythmic pattern evoke the comforting shushing sound of someone who tries to calm an infant while patting him or her on the back. This euphonious effect is carried over the static harmonic sound of a C major chord, which is sustained for the whole passage through the constant repetition of single notes creating an almost hypnotic state while the text insistently repeats “sleep, sleep, sleep”.

One element that is significantly different from descriptions of Nahua performative rituals, however, is that the principal characters in these villancicos are not the elegant elite portrayed in traditional Nahua dances, but marginalized Indians of lower social rank — perhaps because these characters were more compatible with the Christian image of the humble shepherd promoted by post-Tridentine theologians. This is especially evident in ‘Ximoyolali siñola’, which provides an exceptional image of these characters by associating the humble conditions of Christ’s birth with the poverty of Indian natives, only to be contrasted with Spanish wealth.

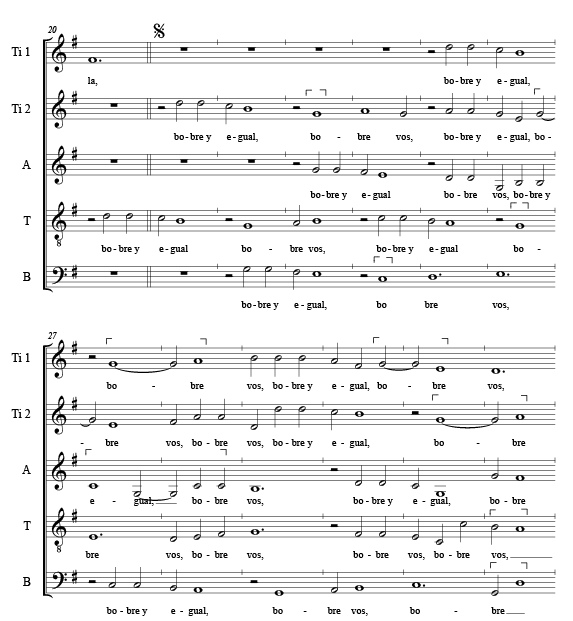

This final villancico portrays an Indian shepherd inviting the Virgin to celebrate the feast of Christmas with a larger group of natives, which includes singing and dancing in the traditional Nahua style. The text opens with the Indian’s exhortation ‘Rejoice, my Lady, / because on earth God has been born’ (‘Ximoyolali, siñola, / tlaticpan o quisa Dios’). The Indian describes Jesus as ‘bobre y egual pobre vos, / no gomo el gente española’, or ‘poor, and equally poor like you, not like Spanish people’, underlining the evident disparity between Christ and the Spanish population, while privileging Indian poverty for its similarity to that of the child and his mother. It is significant that these verse-lines are the only ones written in mestizo, so it is the only section that non-Nahuatl speakers would be able to understand. They also constitute the core of the villancico, as this section elaborates in imitative polyphony and repeats after each copla. In other words, the intense contrast between Spanish wealth and Indian poverty becomes the central theme in a villancico written in Nahuatl, though executed in a way that is perfectly discernible by all listeners.

Example 2.2 ‘Xicochi conetzinle’, mm. 1–14. Otro [villancico] en indio [a 4, 1614], AHAAO, CMGF, ff. 217v–218r.

‘Ximoyolali, siñola’ is set for five voices in triple meter with final on D. The second part of the estribillo is based on a descending melodic gesture D-D-C-B (bobre y egual) arranged in symmetry with the ascending one G-A-B (bobre vos). This brief descending and ascending formula is repeated by other voices in imitative polyphony and the phrase ‘bobre y egual, bobre vos’ is heard twelve times. Perhaps the most effective aspect of this imitation is that the word ‘bobre’ is sung on the second and third beats for a lengthy duration of sixteen bars until the tonal motion dips heavily towards a cadential gesture in B major. The reiteration of Indian poverty is only released by the words ‘not like Spanish people’ (‘no gomo el gente española’) in an almost homophonic section that eventually leads to a plagal cadence to D for the final Alleluia (the cadence is not included in Example 2.3).

Example 2.3 ‘Ximoyolali, siñola’, mm. 20–40. [Villancico] en indio [a 5, 1611], AHAAO, CMGF, ff. 99v–100r.

Such emphatic attention towards Indian poverty recalls Loyola’s exaltation of humility and poverty as necessary conditions for eternal salvation, especially as they relate to Christ’s birth. As thoroughly explained in his Spiritual Exercises, ‘in order to imitate Christ our Lord better and to be more like him here and now’, one ought to lower and humble oneself and ‘choose poverty with Christ poor rather than wealth’.41 From this perspective, the Indian shepherd serves as a better role model for society than the Spanish or the Mexica elite, because his marginal condition allows him to experience Christ’s humility and suffering with greater empathy. But this startling analogy also reflects the conflictive theological and economic interest of the Spanish imperial regime with regard to the native population. The sympathetic image of Indian laborers displayed in the most popular feast of the year must have been particularly significant in a city like Puebla that kept an ever-increasing number of Indians and Africans working in exploitative conditions in order to support local industries.

Allegories of Nahua Song and Dance

Other literary sources relate closely to the novel portrayals of native characters in ‘villancicos en indio’, especially two poetic renditions associated with celebrations promoted by the Society of Jesus. These are dramatized Nahua song and dance numbers — which from this time on are consistently identified by authors as tocotines — incorporated into larger literary works to allegorize the participation of the native population in major Christian festivals in the New World. The first is Los Silgueros de la Virgen, a pastoral novel published in 1620 by Francisco Bramón, a Jesuit priest born in New Spain; the latter, Vida de San Ignacio, an anonymous sacred drama written for the entrance of Archbishop Francisco Manso y Zúñiga to Mexico City in October 1627. The poetic attributes of these works are clearly inspired by sixteenth-century chronicles of Nahua rituals and therefore relate to certain musical features found in Fernández’s villancicos, especially those that evoke the drumming sound of the teponaztli and the huéhuetl.

Bramón, for instance, dramatizes the preparation and celebration of the feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin using a great variety of poetic, literary, and dramatic genres around the Marian theme, including apologetic dialogue, emblem poetry, the narrative of triumphal arch designs, religious drama, as well as references to song, dance, and instrumental music. The third section of this work consists of a sacramental play that honors the Virgin’s triumph by showing the heartfelt acceptance of the Christian faith by the Mexica people.42 This play is attributed to the shepherd Anfriso, one of the main characters of Los Silgueros and whose name functions as an anagram of Francisco, allowing thus for the complete projection of Bramón not only as a humble shepherd in the Marian feast but as the dramatist of the play within a play.43

Anfriso’s play concludes with a final dance or fin de fiesta to represent the Mexicas celebrating both the triumph of the Virgin and her arrival in the New World. The figure of a young and gallant character wearing lavish garments made of gold and feathers serves as an allegory for the Reino Mexicano (Mexican Kingdom). The Nahua elite is represented by six principal caciques of noble lineage dancing together with the Reino Mexicano and its vassals; they all wear rich Mexica vestments with flowers and instruments on their hands.44 Bramón then provides a detailed description of the teponaztli and the huehuetl that includes aspects about their physical appearance and the materials they are made of; he also clarifies whether they are played with bare hands or with mallets and mentions their tuning possibilities, which together serve to reconstruct the sonority of ceremonial drumming. Only after the attributes of these instruments have been presented do the Reino Mexicano and the Nahua elite enter to express their plural entity by way of dance. At this point Anfriso warns the reader that the dance cannot be fully grasped in writing because it is only communicated with ‘pleasant rounds, reverential gestures, entrances, intersecting motions, and promenades’, which were marvelously displayed by the Mexica dancers ‘who excelled and left behind the art, and gave enough evidence that they were moved and animated by the zeal of the sacred enjoyment and triumph of the one who was conceived without original sin’.45 Suddenly a group of skilled musicians sung the verses: ‘Mexicas, dance! / Let the tocotín sound! / Because Mary triumphs / With joyous happiness!’46

In this allegorical ceremonial dance, the entire Mexica people is seen joyfully converted and moved by the arrival of Catholicism, as represented by the triumphant Virgin. The Marian dance is no stranger to the hybrid character of past Nahua-Christian performances, which attempted to soften the effects of the Conquest with the display of Indian converts joyfully celebrating the intervention of divine and historical characters.

The tocotín that appears at the end of the first act of Vida de San Ignacio, however, delivers an entirely different message. In the Jesuit play, before the dance begins, an angel expresses his desire to reverence the humble tocotín because he now knows how much Heaven appraises the poor and humble Indians ‘since in the end, for Indians too / the wings that eclipsed the beautiful light / of the Divine Seraphim / were closed [lit. crossed]’ or, to put it simply, because Christ also sacrificed himself for the sake of the Indians.47

The contrasting character of this tocotín is fully appreciated in the text that exhorts the Indians to dance. The opening stanza reads, ‘Moan, Mexicas, / caciques moan, / under the heavy burdens / that so meekly you suffer’, elevating the suffering condition of Indian workers and setting the tone of the long lament that follows.48 The subsequent stanzas critically expose the labor crisis that caused the staggering decline of the native population in the late sixteenth century. In the past, the text continues, ‘forty thousand Indians came out to dance’, but in the future people will have to ask what Indians looked like because none of them will survive.49 The image of Mexicas dancing while carrying heavy loads is compared again with an ideal better past, when the burdens were not excessive and were distributed among more people. Today, however, ‘an Indian is like a camel, / he is loaded until he dies / and he dies dancing / like the warrior dancer [matachin]’.50

The contemptuous and undeniably subversive tone of this tocotín exposes a clear political intention that performances like these could have, especially when witnessed by church and royal authorities during a public festival. This time, the main purpose in allegorizing native ceremonial practices does not seem so much to engage the native population themselves, but to heighten awareness about the exploitative conditions endured by natives, especially for the new appointed archbishop who had just arrived. The text of the tocotín continues a tradition inherent in Ignatian theology and echoed in ‘villancicos en indio’ that exalts the Christian virtues of poverty and suffering by associating the impoverished conditions of Indian workers with that of Christ. This dramatic panegyric to honor the life of Saint Ignatius asks participants to experience in their flesh the unpleasant consequences of the Conquest as mirrored in the suffering of Christ.

Conclusion

The interest in the preservation and appropriation of Nahua song and dance practices as a tool for conversion was motivated by the idea that the strong collective effect of singers, dancers, and percussionists could be rechanneled for the promotion of Christian devotion. The chronicles that document these efforts show the emergence of novel musico-poetic genres that take roots in early modern Spanish lyric poetry and devotional singing traditions of the Hispanic Catholic Church. A close reading of these narratives allows a richer understanding of the effect of hybridized sacred music in colonial contexts.

The extremely scarce musical sources restrict the possibility of further establishing connections with Nahua ceremonial practices. Nonetheless, Fernández’s ‘villancicos en indio’ show a deliberate attempt to create an Indian affect, aided by specific musical devices that suggest the sonority of native performative practices. Audible Nahua influences must have triggered the imagination of attentive listeners during the liturgy, casting a new light on the post–Tridentine desire to harness the affective power of music and reaffirm the place of the sensuous in religious rituals.

The persistent representation of Nahuas as poor or humble suffering workers in villancicos and sacred dramas alike shows that while the main purpose of such representations was to appeal to the native population, they also served as a political tool to talk back to the exploitative practices toward workers and enslaved labor and to critique the stunning demographic decline of the native population. These texts emphasized the humanity of Indian characters, which was originally shaped after the figure of biblical shepherds, so that poverty and humility could give voice — a Christian voice, that is — to the native people.

1 I have presented versions of this chapter at various conferences, including ‘Atlantic Crossings: Music from 1492 through the Long 18th-Century’ (Boston University Center for Early Music Studies, 2019) and the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Meeting (University of Pittsburgh, 2019). A modified version of this essay will appear as ‘Voz, afecto y representación nahua en la canción vernácula del siglo XVII’ for the history journal Historia Mexicana edited by El Colegio de México. I want to thank the personnel of the Archivo Municipal de Puebla, especially historian Arturo Córdova Durana, who generously guided me through the local archival sources. Preparations for this chapter were supported by grants from the Princeton Program in Latin American Studies and the Yale Institute of Sacred Music.

2 The Nahuas ‘were the most populous of Mesoamerica’s cultural linguistic groups at the time of the Spanish conquest’ and were historically present in diverse regions of today’s Mexico and central Latin America. Mexicas, who were the Nahuas that inhabited the imperial capital, Tenochtitlan, are often misleadingly called Aztecs. See James Lockhart, Nahuas and Spaniards: Postconquest Central Mexican History and Philology (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991), p. 2.

3 The terms used by chroniclers to describe the Nahua song and dance rituals are netotiliztli, macehualiztli, mitote, baile, areito, and tocotín.

4 In the aftermath of the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church reinforced the practice of religious rituals that involved the use of the body to enhance the religious experience. Although some decrees attempted to regulate expressions of popular piety and certain paraliturgical traditions, reformists also strengthened public forms of religious performance and external devotional practices to stimulate a corporeal understanding of the sacred. These forms of religious expression were highly influential for Franciscans and Jesuits around the globe. The Jesuit José de Acosta, for instance, sustained that Indians should be allowed to maintain these uses and customs because they could channel their joy and celebration ‘towards the honor of God and the Saints in their feast days’. Acosta, Historia natural y moral de las indias…, ed. by Edmundo O’Gorman (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2006), pp. 356.

5 The custom of preparing Christian texts in Nahuatl in the native style was presumably introduced in New Spain by the Franciscan missionary Pedro de Gante, who arrived only two years after the conquest. See John Bierhorst, Cantares Mexicanos: Songs of the Aztecs (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985), pp. 110–111. The accommodation of native forms and customs such as song, dance, and drama in the local vernacular had been already in use by Hernando de Talavera for the conversion of Muslims and Jews after the Reconquista of Southern Spain. See Mina García Soormally, ‘La conversión como experimento de colonización: de Fray Hernando de Talavera a “La conquista de Jerusalén”’, MLN, 128.2 (2013), 225–244 (at 226–28), https://doi.org/10.1353/mln.2013.0013; and Barbara Fuchs, Mimesis and Empire: The New World, Islam, and European Identities (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 105, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511486173

6 For more on the Marian songs in Códice Valdés see Gabriel Saldívar, Historia de la música en México (México: Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1934), pp. 101–107; Robert Stevenson, Music in Mexico. A historical survey (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1952), pp. 119–122; Eloy Cruz, ‘De cómo una letra hace la diferencia: las obras en náhuatl atribuidas a Don Hernando Franco’, Estudios de Cultural Náhuatl, 32 (2001), 258–295.

7 Geoffrey Baker, for instance, describes ethnic villancicos as written messages intended to impose an idealized Hispanic order over chaotic local realities. As such, the aim of incorporating popular speech is to mock the deficient use of language of people from diverse regional or ethnic origins. See Baker, ‘The Resounding City’, in Music and Urban Society in Colonial Latin America, ed. by Geoffrey Baker and Tess Knighton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 10–12.

8 The teponaztli is a horizontal slit drum with two tongues made of hollow hardwood logs and is played with mallets. Each of its two tongues produces a different tone. The huehuétl is a single-headed standing drum played with bare hands. The huéhuetl can also produce two distinct tones by striking either the center of the drumhead or near the outer rim.

9 Francisco López de Gómara, Historia de la Conquista de México, ed. by Jorge Gerria Lacroix (Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho, 2007), pp. 139–140. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are by the author.

10 Juan de Tovar, Historia de la venida de los indios (c. 1585), f. 58r (MS held by The John Carter Brown Library).

11 Andrés Pérez de Ribas, Historia de los triumphos de nuestra santa fe… (Madrid: Alonso de Paredes, 1645), p. 639–640.

12 Claudia Parodi, ‘Multiglosia virreinal novohispana: el náhuatl’, Cuadernos de la Asociación de Lingüística y Filología de la América Latina, 2 (2011), 89–101 (at 98).

13 Parodi, ‘Multiglosia virreinal’ (at 93–98). NB the term criollo referred to a person of Spanish descent born in the New World and ‘mestizo’ to a person of combined European and Native American descent.

14 Gerónimo de Mendieta, Historia eclesiástica Indiana, ed. by Joaquín García Icazbalceta (México: Antigua Librería, 1870), p. 552.

15 The episcopal see of the diocese of Tlaxcala was transferred to Puebla in 1543. The term of Mota y Escobar as bishop of Tlaxcala (1607–1625) coincides for the most part with Gaspar Fernández’s tenure as chapelmaster of Puebla Cathedral (1606–1629).

16 See Alonso de la Mota y Escobar, Memoriales del Obispo de Tlaxcala: Un recorrido por el centro de México a principios del siglo XVII (Mexico: Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1987).

17 Toribio de Benavente [Motolinía], Memoriales o Libro de las cosas de la Nueva España… ed. by Luis García Pimentel (Mexico: Casa del editor, 1903), pp. 339–340.

18 Motolinía, Memoriales, p. 344.

19 Opinions regarding the use of native dances varied even among members of the same religious order. This is evident in the contrasting attitudes of the two most vocal Franciscans during the first period of the evangelization project, Motolonía and Juan de Zumárraga, the latter a Spanish Franciscan prelate and first bishop of New Spain who prohibited native dances in New Spain in 1539. Dances were promptly reinstituted immediately after the bishop’s death.

20 The performance of native songs and dances were proscribed by ecclesiastical writ in 1539 and again in the penal code issued in 1546. See John Bierhorst, ‘Introduction’, in Ballads of the Lords of New Spain: The Codex Romances de los Señores de la Nueva España, trans. by John Bierhorst (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), p. 16.

21 Motolinía understood that the creation of a new repertory of Christian songs in Nahuatl required a specific set of musico-poetic skills he did not have. Hence he asks: ‘[B]ut who will do it? I confess myself unskilled and unmerited because to compose a new canticle or praise requires a good instrument, a good throat, and a good tongue, all of which I very much lack’ (Motolinía, Memoriales, p. 356).

22 Sahagún uses the term ‘mystical’ when describing the powerful collective effect that resulted from the coordination of sound and movement of large groups of singers and dancers. Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España… ed. by Carlos María de Bustamante (México: Alejandro Valdés, 1829), p. 25.

23 A few songs in ‘Cantares’ and ‘Romances’ include drumming-pattern indications with different combinations of the syllables ti, to, qui, and co, but no further instructions for musical interpretation are provided for performers. The lack of music notation has limited the attention of musicologists and ethnomusicologists — with a few notable exceptions — especially when compared to the long scholarly tradition generated from other disciplines, such as philology, linguistics, anthropology, and history. This issue is discussed in Gary Tomlinson, The Singing of the New World: Indigenous Voice in the Era of European Contact (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 3–5, 42–49; Lorenzo Candelaria, ‘Bernardino de Sahagún’s Psalmodia Christiana: A Catholic Songbook from Sixteenth-Century New Spain’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 67.3 (2014), 623–633; Emilio Ros-Fábregas, ‘“Imagine all the people…” Polyphonic Flowers in the Hands and Voices of Indians in 16th-Century Mexico’, Early Music, 40.2 (2012), 177–189 (at 177), https://doi.org/10.1093/em/cas043

24 The collaborative process between native intellectuals and Christian missionaries also meant the ‘active destruction and replacement’ of pre-existing cultural traditions. Hilary Wyss reminds us that the product of this collaboration ‘was never intended for Native use, but rather to educate Spanish missionaries about Native practices and beliefs, the better to eradicate them’. Wyss, ‘Missionaries in the Classroom: Bernardino de Sahagun, John Eliot, and the Teaching of Colonial Indigenous Texts from New Spain and New England’, Early American Literature, 38.3 (2003), 505–520 (at 510), https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2003.0049

25 Bernardino de Sahagún, Psalmodia christiana y sermonario de los sanctos del año en lengua mexicano (México: Casa de Pedro Ocharte, 1583), ff. 1r–1v, http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000085282&page=1. The first part of the volume consists of a brief catechism with the main precepts and prayers of the Catholic Church translated into Nahuatl.

26 Acosta, Historia natural y moral de las indias…, p. 354.

27 The text was composed by another member of the Jesuit Colegio de San Pedro y de San Pablo in Mexico City. Morales’ description includes the Nahuatl version and the Spanish translation provided by the same priest. Mariana Masera observes that while the poem in Nahuatl is organized in heptasyllabic lines, the Spanish translation is octosyllabic. See Mariana Masera, ‘Cinco textos en náhuatl del “Cancionero de Gaspar Fernández”: ¿una muestra de mestizaje cultural?’, Anuario de Letras: Lingüística y filología, 39 (2001): 291–312 (at 297–300).

28 Pedro Morales, Carta del padre Pedro Morales de la Compañía de Iesús. Para el muy reverendo padre Everardo Mercuriano, General de la misma compañía…, ed. by Beatriz Mariscal Hay (Mexico: El Colegio de México, 2000), pp. 32–33.

29 For more about the patronage of St. Hippolytus in Mexico City after the Conquest of Mexico see Lorenzo Candelaria, ‘Music and Pageantry in the Formation of Hispano-Christian Identity: The Feast of St. Hippolytus in Sixteenth-Century Mexico City’, in Music and Culture in the Middle Ages and Beyond: Liturgy, Sources, Symbolism, ed. by Benjamin Brand and David J. Rothenberg (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016), pp. 89–108, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781316663837.006

30 Fernández only rarely indicates when a villancico is intended for an institution other than the cathedral (as he also composed for female and male religious orders), but as the chapelmaster of the cathedral it would be fair to assume that the vast majority of villancicos correspond with his duties at this institution.

31 Although biographical details about Fernández’s life are still under debate, Omar Morales Abril has demonstrated that he is not the Portuguese singer and organist listed in Evora Cathedral in the 1590s, but a much younger musician born in the Guatemalan province. See Morales Abril, ‘Gaspar Fernández: su vida y obras como testimonio de la cultura musical novohispana a principios del siglo XVII’, in Ejercicio y enseñanza de la música, ed. by Arturo Camacho Becerra (Oaxaca: CIESAS, 2013), pp. 71–125.

32 Fernández’s Cancionero consists of roughly 270 villancicos annotated in an autograph manuscript between 1609 and 1616. This document is held at the Archivo Histórico de la Arquidiócesis de Antequera Oaxaca (AHAAO). For more on Fernández’s Cancionero, see Aurelio Tello, Cancionero Musical de Gaspar Fernandes, Tomo primero, Tesoro de la Música Polifónica en México 10 (México: CENIDIM, 2001); Tello, El Archivo Musical de la Catedral de Oaxaca: Catálogo (México: CENIDIM, 1990); Margit Frenk, ‘El Cancionero de Gaspar Fernández (Puebla-Oaxaca)’, in Literatura y cultura populares, ed. by Mariana Masera (Barcelona: Azul and UNAM, 2004), pp. 19–35; and Morales Abril, ‘Gaspar Fernández: su vida y obras’.

33 For the liturgical function of the sacred villancico see Álvaro Torrente, ‘Functional and liturgical context of the villancico in Salamanca Cathedral’, in Devotional music in the Iberian World, 1450–1800: The Villancico and Related Genres, ed. by Tess Knighton and Álvaro Torrente (Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate, 2007), pp. 99–148.

34 For more on the characteristics and taxonomies of ‘villancicos de personajes’ (also described as ‘villancicos de remedo’ or ‘ethnic villancicos’), see Omar Morales Abril, ‘Villancicos de remedo en la Nueva España’, in Humor, pericia y devoción: villancicos en la Nueva España, ed. by Aurelio Tello (México: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2013), pp. 11–38; and Esther Borrego Gutiérrez, ‘Personajes del villancico religioso barroco: hacia una taxonomía’, in El villancico en la encrucijada: nuevas perspectivas en torno a un género literario-musical (siglos XV–XIX), ed. by Esther Borrego Gutiérrez and Javier Marín López (Kassel: Reichenberger, 2019), pp. 58–96.

35 In early modern Iberian poetry, the two main types of rhyme are perfect rhyme, when vowels and consonants are identical, and assonant rhyme, when only the vowels but not the consonants are identical.

36 All English translations of the texts in Nahuatl are drawn from Berenice Alcántara Roja’s study and Spanish translation of Fernández’s ‘villancicos en indio’, where she also discusses their meter and rhyme schemes. See Alcántara Rojas, ‘“En mestizo y indio”: Las obras con textos en lengua náhuatl del Cancionero de Gaspar Fernández’, in Conformación y retórica de los repertorios catedralicios, ed. by Drew Edward Davies and Lucero Enríquez (México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2016), pp. 53–84 (at 59–77); this article is followed by a detailed paleographic analysis of the music of Fernández’s ‘villancicos en indio’. See, Drew Edward Davis ‘Las obras con textos en lengua náhuatl’, pp. 85–98.

37 Pearls were also associated with wealth, especially after maritime jewels harvested in the Spanish Caribbean entered the global market, transforming their role in the imperial economy. For more about pearls in the aftermath of Spanish imperial expansion see Molly A. Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492–1700 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2018), pp. 1–13, https://doi.org/10.5149/northcarolina/9781469638973.001.0001

38 For more about the intimate character of this villancico see Chávez Bárcenas, ‘Villancicos de Navidad y espiritualidad postridentina en Puebla de los Ángeles a inicios del siglo XVII’, in El villancico en la encrucijada: nuevas perspectivas en torno a un género literario-musical (siglos XV–XIX), ed. by Esther Borrego Gutiérrez and Javier Marín-López (Kassel: Reichenberger, 2019), pp. 233–258 (at 255–256).

39 As I have demonstrated elsewhere, however, despite the stereotypical comic representation of African slaves in ‘villancicos de negros’, they also include subversive messages that challenged early modern assumptions of racial difference and gave voice to free and enslaved workers of African descent in seventeenth century New Spain. The recent study by Nicholas R. Jones also demonstrates that African characters portrayed in Spanish literary works very often act and speak with agency, destabilizing the cultural, linguistic, and power relations of the Spanish elite, which offers a compelling revised perspective about the use of the Afro-Hispanic pidgin in early modern Spanish literature. See Chávez Bárcenas, ‘Singing in the City of Angels: Race, Identity, and Devotion in Early Modern Puebla de los Ángeles’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Princeton University, 2018), pp. 163–200; and Nicholas R. Jones, Staging Habla de Negros: Radical Performances of the African Diaspora in Early Modern Spain (University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2019), pp. 4–26.

40 Alcántara Rojas, ‘“En mestizo y indio”’, pp. 59.

41 Ignatius of Loyola, Spiritual Exercises and Selected Works, ed. by George E. Ganss (New York: Paulist Press, 1991), pp. 160.

42 Francisco Bramón, Auto del triunfo de la Virgen (México: [n.p.], 1620), ff. 130r–161r.

43 Metadrama was a popular dramaturgical device in Spanish Golden-Age comedia to blur the boundaries between fiction and reality.

44 Bramón, Auto, f. 157r.

45 Ibid., ff. 157v–158r.

46 Ibid., f. 158r.

47 Vida de San Ignacio de Loyola. Comedia Primera (c. 1627), cited in Edith Padilla Zimbrón, ‘El tocotín como fuente de dates históricos’, Destiempos, 14 (2008), 235–249 (at 238).

48 Vida de San Ignacio in Padilla Zimbrón, ‘El tocotín’, 239–240. The opening verses of this tocotín were clearly molded after the tocotín included in Los Silgueros by Bramón, not only for the imitation of the hexasyllabic romancillo form but also for the opening exhortation of the Indian population identified as ‘mexicanos’. The romancillo form consists on hexasyllabic or heptasyllabic verses with assonant rhyme in the even lines.

49 Vida de San Ignacio in Padilla Zimbrón, ‘El tocotín’, p. 244.

50 Ibid., p. 246.