3. Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

© Michael Yao Wodui Serwornoo, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0227.03

This chapter is divided into three main parts: the introduction, the theoretical review and the frameworks of the study. It discusses the linkage of the three theoretical approaches beginning with an overview of the theories and how they have been deployed in previous research, with emphasis on strengths, weaknesses, limits and recommendations that will eventually form the basis for this study’s theoretical and conceptual design.

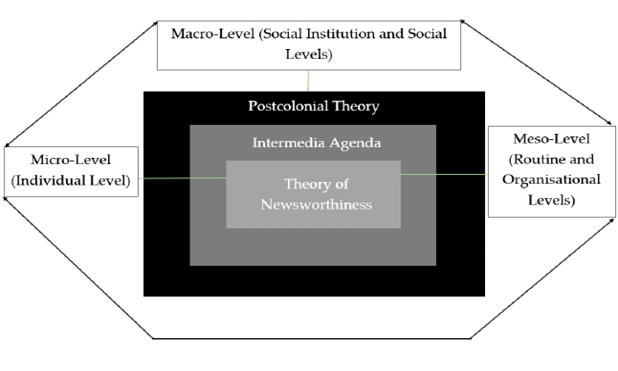

The superimposition of the postcolonial theory on the theories of newsworthiness and intermedia agenda-setting is categorical in nature. This does not mean that the postcolonial theory is more useful than the two other theories; it only signifies the overarching critical impulse of it. The positioning of these theories in the model only represents the way the study conceives of their analytical application. What is new about this approach is that the weaknesses of the theory of newsworthiness, for example, to explicate meso- and macro-level influences on news selection decisions are minimised because other theories within the integrated framework can be used.

Firstly, it is argued that any model predicting news selection decision must incorporate intermedia influences, because they are real both in intra-nation and inter-nation agenda-settings (Du, 2013; Golan, 2006; Vliegenthart and Walgrave, 2008; McCombs, 2005). Lei Guo and Chris Vargo (2017) have further solidified the place of intermedia agenda-setting in international news flow debate through a theoretical mapping (using big data) of how news media in different countries influence each other in covering international news.

Secondly, arguments in this regard tend to claim that news factors and intermedia agenda-setting have not been developed to explain macro-level ideological influences that disrupt the innocence of Eurocentric knowledge around journalism and that question what is broadly described as globalisation, which also is imperial in nature (Paterson, 2017).

Thirdly, the question of why some countries are more newsworthy than others, and the similarities and differences in the scope of international news presented in different languages and cultures, has been theoretically tackled using the current global communication order, Internet and online media. Elad Segev (2016) argues that international news affects our perception of the world; in his new book, he explores international news flow on the Internet by addressing those key questions in a manner that combines both theories of newsworthiness and international news flow.

The review of Vincent Anfara and Norma Mertz (2006) demonstrates that the theoretical framework does not have a clear and consistent definition among qualitative researchers. However, the study adopted the idea that the “theoretical frameworks are any empirical or quasi-empirical theory of social and/or psychological processes, at a variety of levels (e.g., grand, mid-range, and explanatory) that can be applied to the understanding of phenomena” (p. 27). A conceptual framework, on the other hand, is not very different from a theoretical framework. According to Matthew Miles, Michael Huberman and Johnny Saldaña (2014), “a conceptual framework explains, either graphically or in narrative form, main things to be studied — the key factors, variables, construct — and the presumed interrelationships among them” (p. 20). It could be argued that conceptual frameworks are founded on theory/theories and as such represent the specific direction by which the research will be undertaken by identifying “who, what will, and will not be studied” (Miles et al., 2014, p. 21). The conceptual framework in this present study is deduced from the theoretical framework with more focus on the specifics of the study’s arguments.

Theoretical Overview

In this section, the theory of newsworthiness, intermedia agenda-setting and the postcolonial theory are comprehensively reviewed as theoretical concepts. In turn, it is outlined how their application to this study offers new ways to understand them. The complimentary appreciation of these theories is to demonstrate that theoretical innovation is not to say that previous theories do not exist but to strengthen their weaknesses in their new applications especially to areas where they have not been significantly combined.

Guo and Vargo (2017) argued that the practice of measuring a country’s salience in foreign news coverage as a measure of its newsworthiness does not provide a good understanding of how news flows around the world because it lacks the ability to predict a country’s capacity to set the agenda for other countries. To capture both phenomena — being newsworthy and setting the news agenda for other countries — emerging studies must investigate the role of different countries in the international news flow from “different theoretical standpoints, including the intermedia agenda-setting theory” (Guo and Vargo, 2017, p. 518). To deal with these dynamics, intermedia agenda-setting theory is applied critically, in this study, to unveil how such journalistic co-orientations and reuse practices occur. Beyond this analysis is also a sublime but evident ideological element related particularly to the coverage of Africa: postcolonial relationships, which require a critique because of the very imbalanced nature within which it contributes to the coverage of Africa in Ghana.

Theory of Newsworthiness

Newsworthiness is one of the most utilised theories to explain how and why journalists select news. While some scholars rely heavily on psychology and perceptions of journalists in terms of both what makes news and what their audience’s interests are, others concentrate on the organisational and professional routines rooted within the journalistic practice. But, at its basic level, the theory uses the concept of news factors to trace news selection back to the specific qualities of events, which are suspected as the determinant of the news value of an event and hence the decision of journalists regarding whether or not that event is newsworthy. According to J. F. Staab (1990, p. 424), most scholars trace the “rudimentary form of this concept to Walter Lippmann” while in a few exceptional cases, the authors refused to mention Lippmann’s work.

The myth surrounding news is defined by Pamela Shoemaker (2006, p. 105) as a “primitive construct whose existence is not questioned”; it is also “passed down to the new generation of journalists through a process of socialisation” (Harrison, 2006, p. 118). Jerry Palmer (2000) describes the workings of news values as “a system of criteria which are used to make decisions about the inclusion and exclusion of materials and transcends individual judgements, although they are, of course, to be found embodied in every news judgement made by a particular journalist” (p. 45). Arguing for the useful place of the theory of newsworthiness even until today, Jürgen Wilke, Christine Heimprecht and Akiba Cohen (2012, p. 304) state that:

Scholars who have studied international news have typically looked to global factors to explain the variability in coverage and much of these research assume that international news coverage reflects the power structure among nations. However, the crafting of media messages, including those focused on international events, is also subject to local influences. Such influences include organisational factors, the local community’s power and corporate characteristics (p. 304).

Staab’s (1990) explication of the theory challenges the assumption that “several news factors determine the news value of an event and therefore the selection decision of journalists” (p. 424). Christiane Eilders (2006); Shoemaker (2006); Staab (1990) and Rüdiger Schulz (1976) have all argued, in the sense of these frameworks, that the concept of new factors cannot be said to explain the actual process of news selection and “its validity is rather restricted to the questions of how far news factors determine size, placement and layout of news stories” (Staab, 1990, p. 246). The use of causal explication for news selection becomes even more contested within this area of research. Most studies on news factors have employed the causal models, which argue that news is selected or published because of its particular qualities (news factors) and an existing objectivity consensus about these qualities. Shoemaker (2006), however, cautioned that this causal model is weak because “news is a social construct, a thing, a commodity, whereas newsworthiness is a cognitive construct and a mental judgment. Newsworthiness is not a good predictor of which events get into the newspaper and how they are covered. Newsworthiness is only one of a vast array of factors that influence what becomes the news and how prominently events are covered” (p. 105).

As Stuart Hall (1997) argues, representation does not entail a straightforward presentation of the world and the relationships in it. For Hall, representation is a very different notion from that of reflection. By selecting news, in the first place, the media represents the world rather than reflects it. These social processes are difficult to causally predict because they are iterative and unconscious, except that some of those causal predictions make several underlying assumptions that basically defeat its potency to produce an accurate account of the prediction.

The definition of events within the concept of news factors has faced both ontological and epistemological difficulties related to the subject-object relationship. Staab (1990, p. 439) clarified these difficulties when he argued against the exclusive power allotted to events which makes it look like events in themselves are capable of determining news selection:

Events do not exist per se but are the result of subjective perceptions and definitions. However, scholars have assumed, at least implicitly, a congruency of events and corresponding news stories. However, this does not fit the structure of news coverage especially in the political area because most events do not exist in isolation, they are interrelated and annexed to larger sequences. Employing different definitions of an event and placing it in a different context, news stories in different media dealing with the same event are likely to cover different aspects of the event and therefore put emphasis on different news factors (ibid.).

The object-based approach to news selection argues that events have some specific characteristics that are attractive to journalists; the more of these characteristics an event seems to possess, the more likely it is that journalists will select it. The argument that the nature of an event itself is the biggest predictor of newsworthiness to journalists ignores the subject-object relationship (Staab, 1990). A subject-based approach to the debate argues, on the other hand, that factors beyond the nature of events are responsible for news selection decisions, and they are quite independent of the events in general (Gans, 2004; Herman and Chomsky, 2008; Van Djik, 2009). For this study, I examine how subject-object based relationships blend together to determine news selection.

Andreas Schwarz (2006), in search of validation of these ideas, tested the theory of newsworthiness by Johan Galtung and Mari Ruge (1965) in Mexico, a non-Western country. Even though he confirmed all the hypotheses he had tested, as a replication of the Galtung and Ruge study, he cautioned that the “relationship between news factors and editorial emphasis that have been found do not necessarily prove that news factors are relevant criteria for the initial selection of news for publication” (p. 59). Deirdre O’Neill and Tony Harcup (2009) maintain that news values can help us understand how some occurrences are marked as “events”, a label which eventually gets them selected as “news”. This theory can also help us explore how some aspects of the selected event get emphasised, while other aspects are downplayed or excluded. To O’Neill and Harcup, in addition to these insights, “news values sometimes blur the distinction between news selection and news treatment” (p. 171). This lead us to the meso-level of the theoretical discussion, where the attention of the analysis shifts from journalistic behaviour to how organisational needs and culture influence the selection process.

Intermedia Agenda-Setting

Apart from the events themselves informing us about their selection or external factors influencing their selection, there is also an inter-organisational borrowing which is also the result of a lifelong socialisation process within the journalistic industry. Much of the research considering this phenomenon has described it as an aspect of agenda-setting theory. In fact, Maxwell McCombs (2005) labels intermedia agenda-setting as the fourth phase of agenda-setting theory, which explores the origins of the media agenda. He further argues that this phase and all other preceding phases of the agenda-setting theory need to “continue together as active sites of inquiry” (p. 118). According to McCombs (2005), agenda-setting theory progressed a little further than the original focus when researchers began asking: “If the press sets the public agenda, who sets the media agenda?” He further explains that the patterns of news coverage that shape the media agenda result from “the norms and traditions of journalism, the daily interactions among news organisations themselves, and the continuous interactions of news organisations with numerous sources and their agendas” (p. 548). He adds that journalists routinely seek to validate their sense of news by observing the work of their colleagues from elite media and this practice has ushered us into what he calls the “intermedia agenda-setting era”, which comprises “the influences of the news media on each other” (p. 549). To assess the intermedia agenda-setting, Guy Golan (2006) and Joe Foote and Michael Steele (1986) compare the similarities in stories’ leads by different media organisations. They argue that “two of the three networks had the same lead 91% of the time, and all three had the same lead 43% of the time” (p. 19).

Rens Vliegenthart and Stefaan Walgrave (2008) offer a comprehensive explanation to intra-nation intermedia agenda-setting by arguing that the process of intermedia agenda-setting is moderated by five factors, namely, lag length, medium type, language/institutional barriers and election or non- election context. Ying Roselyn Du (2013) explores the mass media’s agenda-setting function in a context of increased globalisation to see if the theory of agenda-setting works within the global setting. She finds that “inter-nation intermedia influences” provide a new approach to move the journalistic co-orientation phenomenon to cross-national intermedia comparisons (p. 19). She holds a sceptical position towards the idea that national journalists will reduce negative coverage of the developing nations by international wire services because “Western news organizations have, in some occasions, found some of the reports by national media inaccurate” (p. 142). Yie Xie and Anne Cooper-Chen (2009) argue, in support of Daniel Riffe (1984), that in the case of international news, “borrowing or shortcuts can save enormous amounts of time and money” but that comes with a risk of inaccuracies in national accounts (p. 92). The global nature of news selection leads us to the next theoretical approach in this study, which is the application of postcolonial theory.

Postcolonial Theory

According to Shrikant Sawant (2012, p. 120) “postcolonial theory investigates what happens when two cultures clash and one of them with accompanying ideology empowers and deems itself superior to the other.” To A. Prasad (2003), postcolonial theory is a critique that “investigates the complex and deeply fraught dynamics of modern Western colonialism and anti-colonialism resistance and the on-going significance of the colonial encounter for people’s lives both in the West and in the non-West” (p. 5). These definitions comport with the ideas of Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin (1995), who argue that the way to reconsider Eurocentric and Western representations of non-Western worlds is to unsettle and disrupt the canonical text and theories and their implicit binary operations of “us” and “them”.

Like all paradigms of knowledge, postcolonial theory has its fair share of criticisms and contestations within and outside the milieu. Firstly, the very name postcolonial attracted the attention of some scholars, who considered that as a premature celebration of the end of colonialism, a phenomenon the world is centrally imbricated in (Sawant, 2012). Secondly, the diverse, open-door approach of postcolonial studies to many fields of inquiry presents a serious challenge to an accurate conceptualisation of the field (Shome and Hegde, 2002). Thirdly, postcolonialism, also referred to as postcolonial studies, due to its vastness, runs the risk of unwittingly assuming that all colonial experiences were alike and, by so doing, falls prey to the binary scheme of colonial and postcolonial.

The growth of further binary conceptualisations within the colonised, for instance, depending on race and gender, are crucial for analysis as well. A binary mode would not improve this area of knowledge, however, the unlimited vastness in its conceptualisation is equally constraining. Examples of discursive practices already in use include slavery, dispossession, settlement, migration, resistance, representation, difference, race, gender, class, otherness, place, diaspora, subaltern, sexuality, hybridity, mimicry, ethnicity and many others, all of which have been discussed as part of the wider area (Goldberg and Quayson, 2002; Ashcroft et al. 2001). With these contestations come the clarification for communication scholars put forward by Raka Shome and Radha Hegde (2002), who discuss the integration of postcolonial studies and communication studies. They see postcolonial studies as an interdisciplinary field that theorises the problematics of colonisation and decolonisation. They, however, caution that a mere chronicling of the facts of colonialism would not qualify as a postcolonial study. This is because postcolonial theory within the critical theory tradition is interventionist and a political approach by nature. They argue, “Postcolonial theory does not only theorise colonial conditions but also why those conditions are what they are, and how they can be undone and redone” (p. 250). To Shome and Hegde, a postcolonial study must offer “an emancipatory political stance or interventionist theoretical perspective” in examining issues as a mark of the theory’s critical impulse (p. 250). Shome and Hegde sum up the uniqueness of the milieu of postcolonial theory within the critical scholarship tradition in these words (p. 252):

… Postcolonial theory provides a historical and international depth to the understanding of cultural power. It studies issues of race, class, gender, sexuality, and nationality, that are of concern to contemporary critical scholarship by situating these phenomena within geopolitical arrangements, and relations of nations and their inter/national histories.

In the study presented in this book, it is demonstrated whether or not the journalists are aware of the complexities behind the use of sources and how they have either ignored or resisted this phenomenon. Two concepts within the terminologies of postcolonial studies have been crucial for my analysis: internalised oppression and hybridity.

Fanonian Internalised Oppression

Frantz Fanon (2008) argues that in an attempt of the coloured peeople to escape the association of blackness with evil, they don a white mask, or think of themselves as a universal subject equally participating in a society that advocates an equality supposedly abstracted from personal appearance. This is done through internalising, or “epidermalising”, cultural values into consciousness, which results in a fundamental disconnection between the black man’s consciousness and his body. Under these conditions, the black man is necessarily alienated from himself. Paul Gilroy argues that the concept of epidermalisation emanates from a complex combination of philosopher-psychologist’s phenomenological ambitions, that privilege a certain way of seeing and understanding of sight. Gilroy (2000) argues that the concept suggests a perceptual regime in which the racialised body is bounded and protected by its enclosing skin. He then critiques it by stating that the “idea of epidermalisation points towards one intermediate stage in a critical theory of body scales in the making of race. Today skin is no longer privileged as the threshold of either identity or particularity” (p. 47). Dilan Mahendran (2007) refutes Gilroy’s notion, stating that he has confused the lived experience of race for its representation. Mahendran argues (p. 193),

It is the representation of blackness and its commoditisation in popular culture that Gilroy sees as shifting in the history of ‘raciology’ and not the lived experience of showing up black which has been durable in the long history of racism in the West..

Epidermalisation represented for Fanon a pathological metaphor to describe colonial conditions which would cover both perceptual and physical anti-black racism and the primacy of sight that the black-skinned man can never escape. In Black Skin, White Mask, Fanon says “I am overdetermined from without. I am the slave not of the idea that others have of me but of my own appearance” (p. 87). By this, he provides a notion of internalised oppression known generally as epidermalisation of inferiority (Fanon, 2008) and this has caused some people of colour to accept their subjected position as being the natural order of things. Fanon did not stop articulating this point. In Wretched of the Earth, he makes a refreshing appeal:

Come, then, comrades, the European game is finally ended; we must find something different. We today can do everything, so long as we do not imitate Europe, so long as we are not obsessed by the desire to catch up with Europe (Fanon, 2001, p. 251).

Fanon saw imitation as a major hurdle for the newly independent states not because he wanted a complete divorce, but because he feared that imitation could play into the disruption of the psychic realm that had already taken place during the colonial encounter.

Bhabha’s Hybridity and Third Space Intervention

It is clear from the works of Homi K. Bhabha (1994) and Ashis Nandy (1988), how the psychic realm of the colonised operates. The sublime nature of globalisation of speech to the advantage of the Western world, and the cravings of the colonised to legitimise their quality through imitation of the coloniser, is further exacerbated by the lingering influences of Western education, training and ownership of knowledge. Bhabha (1994) argues that changes in the psychic realm that were inflicted on the colonised during the colonial experience are very active even in postcolonial times. According to Bhabha (1994), in this era, the ruling is predominantly through capital flows rather than through force of military. Bhabha, however, acknowledged (p. 38):

The historical connectedness between the subject and object of critique […] shows that there can be no simplistic, essentialist opposition between ideological misrecognition and revolutionary truth. The progressive reading is crucially determined by the adversarial or agonistic situation itself; it is effective because it uses the subversive, messy mask of camouflage and does not come like a pure avenging angel speaking the truth of radical historicity and pure oppositionality.

The concept of the psychic realm in the work of Fanon represents a concept of submissive imitation, which assumes that the colonised is a passive alienated subject living on the edges of two worlds and constantly seeking legitimisation. But the necessary legitimisation by the coloniser in the postcolonial space — even in the era of globalisation — is still categorised and operated with a binary framework, such as “developed and developing”; “East and West”; “poor nations and rich nations”. Fanon describes this concept fully using the term mimicry.

Bhabha, a staunch reader of Fanon, however, digresses from this essentialist conceptualisation of the colonised, arguing instead that the imitation practised by the colonised is not homogenous, but rather metonymic resemblance, repetition and difference. To encapsulate this idea, he coined the description of “almost the same but not quite” (p. 86). Bhabha (1994) then introduced the term third space as a place of hybrid identity that emerges from the fact that the colonised had to live on the edges of two worlds after being psychologically persuaded to imitate their ruler in language, attitude and worldviews. The changes in the way the psychic realm of the colonised works are more permanent than the structural elements that colonisation enforces (Bhabha, 1994 and Fanon, 2008).

Apart from these, Bhabha sees the performative practices of the postcolonial relationship as a subversive imitation, rather than submissive, which is characterised by fragmentations, contradictions, cracks and inconsistencies rather than binary oppositions. To him, the significant racial and cultural differences that exist between the world of the coloniser and the colonised is beyond binary categorisation and opposition. There are, in Bhabha’s observation, “disabling contradictions within the colonial relationship” that expose the vulnerability of coloniser’s discourse and allows the emergence of “subversive performative practices” (Ashcroft et al. 2007, p. 37). Bhabha (1994) tackled what shall constitute a hybrid performance as well.

However, his definition of hybridity is highly nuanced. He states that “hybridity is a camouflage” (p. 193), and that hybridity is the way “newness enters the world” (p. 227). He adds that, in his conceptualisation, the space of the postcolonial relationship is an ambivalent one “where cultural signs and meaning-making have no primordial unity or fixity” (pp. 28–37). Though these descriptions are difficult to empirically set out, for Bhabha, small differences, slight alterations and displacements — whether conscious or unconscious — are crucial for the agenda of subversion. He further offers a conceptualisation of how this hybrid resistance is performed to allow one to recognise it:

Resistance is not necessarily an oppositional act of political intention, nor is it the simple negation or exclusion of the “content” of another culture, as a difference once perceived. It is the effect of an ambivalence produced within the rules of recognition of dominating discourses as they articulate the signs of cultural difference and reimplicate them within the deferential relations of colonial power-hierarchy, normalization, marginalization and so forth (Bhabha, 1985, p. 82).

Zehra Sayed (2016) offers an empirical description, focusing specifically on India, by arguing that the hybridity conditions described by Bhabha have led to a simultaneously “in-ward and out-ward looking dialectic, a symptom of the postcolonial identity” which is exhibited by the Indian media industry, and especially by actors within foreign-owned news agencies (p. 20). Marwan Kraidy (2002) brings Bhabha’s debate more closely into the realm of communication when he explains that even though the concept of hybridity has been applied variously to describe mixed genres and identity, it is still rare to see the conceptualisation of it at the heart of communication theory. He argues that because hybridity is a widely used concept, “the recent importation of it to areas such as intercultural and international communication, risks using the concept as a merely descriptive device, that is, describing the local reception of global media texts as a site of cultural mixture” (p. 317). Kraidy also argues that the use of hybridity as a descriptive device presents ontological and political quandaries. Ontologically, Kraidy (2002) sees hybridity not “as a clear product of global and local interactions but as a communicative practice constitutive of, and constituted by, socio-political and economic arrangements” (p. 317).

While the pursuit of this present study is no different, my research is unique in the sense that it provides an approach which can be used productively to discuss new debates over how the resistance of the colonised should be described. When will an act suffice as resistance and how do we judge this? Bhabha (1995) answers with a framework to gauge the resistance element in the imitation of the colonised by arguing that the whole postcolonial relationship involves a “process of translating and transvaluing cultural difference” (p. 252), thereby establishing that — whether in the world of the colonised or the coloniser — no monolithic or essential cultural features exist. This disruption on both sides, no matter how small, constitutes a resistance of sorts.

Essentialism versus Agency

The definition of essentialism offered by Diana Fuss (1989) introduces the concept from the perspective of its critiques (p. xii):

Essentialism is typically defined in opposition to difference; the doctrine of essence is viewed as precisely that which seeks to deny or to annul the very radicality of difference. The opposition is a helpful one in that it reminds us that a complex system of cultural, social, psychical, and historical differences, and not a set of pre-existent human essences, position and constitute the subject. However, the binary articulation of essentialism and difference can also be restrictive, even obfuscating, in that it allows us to ignore or deny the differences within essentialism.

Bhabha highlights the contradictions inherent in colonial discourse in order to underscore the coloniser’s ambivalence with respect to his position toward the colonised Other. The simple presence of the colonised Other within the textual structure is enough evidence of the ambivalence of the colonial text, an ambivalence that destabilises its claim for absolute authority or unquestionable authenticity. This is a basic response to Fanon’s perspective, in which the colonised is robbed of all agency and, consequently, he/she pursues an imitation of the master. In addition to the fact that the role of the colonised in his/her imitation of the coloniser is completely ignored in the dominant literature, in postcolonial studies, the locus of agency is located in the postcolonial relationship which involves the colonised.

Hierarchical Influences Model

Studies analysing media content must make explicit the symbolic environment within which the content is situated, in order to delimit the two blurring areas of research — what shapes the content and what impact it has (Reese and Lee, 2012). The Hierarchical Influences Model of Shoemaker and Reese becomes significantly useful for organising the theoretical concepts in this study. This hierarchical model has philosophical underpinnings that ought to be clarified early enough to situate its use in this study. The media as a mirror hypothesis, which argues that media reflects social reality with little distortion, is attractive to journalists because of its power to render content neutral. Shoemaker and Reese (2014) make a categorical statement about media content when they assert that media content is “fundamentally a social construction, and as such can never find its analogue in some external benchmark, a mirror or reality” (p. 4). What is crucial for studies on media content is the negotiation of this philosophical premise in an organised manner.

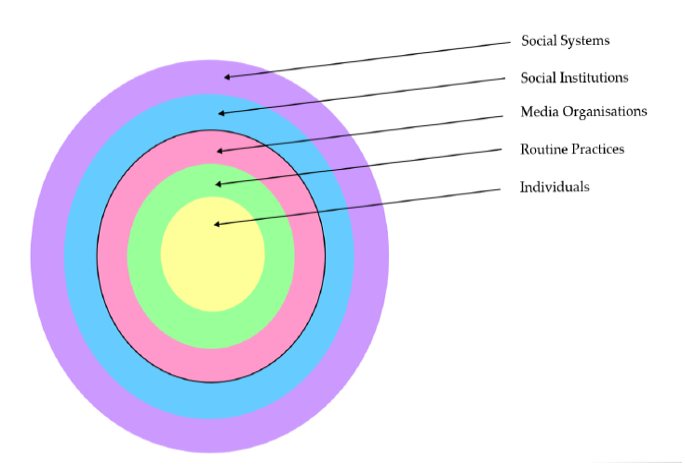

Due to the multi-faceted nature of influences shaping media content, it is crucial to organise this study’s theoretical framework with a broadly acceptable hierarchy. Just like Shoemaker and Reese (2014), this study argues that exercising a hierarchical organisation offers “more clarifications, definitions, assumptions and empirical indicators and relationships for the theoretical groundings of any research work” (p. 5). As such, locating the theoretical framework proposed in Figure 3.2 within the Hierarchical Influences Model requires contextual adjustments and re-modelling that is useful for this research.

The Shoemaker and Reese Hierarchical Influences Model is made up of five layers of influence. The theoretical perspectives that provide the basis for factors shaping media content have been laid bare by Todd Gitlin (2003) and Herbert Gans (1979) as follows:

- Content is influenced by media workers’ socialisation and attitudes. This is a communicator-centered approach, emphasising the psychological factors impinging on an individual’s work: professional, personal and political.

- Content is influenced by media organisations and routines. This approach argues that content emerges directly from the nature of how media work is organised. The organisational routines within which an individual operates from a structure, constraining action while also enabling it.

- Content is influenced by other social institutions and forces. This approach finds that the major impact on content is external to organisations and the communicator: i.e., economic, political and cultural forces. Audience pressures can be found in the “market” explanation of “giving the public what it wants.”

- Content is a function of ideological positions and maintains the status quo. The so-called hegemony approach identifies the major influence on media content as the pressures to support the status quo, to support the interests of those in power in society (Shoemaker and Reese, 2014, p. 7).

The latest model of Shoemaker and Reese (2014, p. 9) has five levels of analysis: individual, routine, organisation, social institutions and social system as shown in Figure 3.1.

Fig. 3.1 The Hierarchy of Influences Model (Shoemaker and Reese, 2014, p. 9). Figure created by author (2020).

Individual Level

The individual level seeks to describe the creators of media content and how individual character traits provide a context within which they appreciate their professional roles. This level recognises the agency of individual journalists or media workers as actors under a larger professional constraint which eventually determines their actions. According to Shoemaker and Reese (2014), the power of media creators includes personal traits and idiosyncrasies that have been exhibited mainly through professional and occupational channels. The issue of digital communication and its appeal to individualism as an influential determinant of identity is clearer now than before. Located within the ideas of Manuel Castells (1996), the emerging networked relationship limits the workings of institutional analysis and rather draws attention to the relationship between the self and the net.

As a conceptual guide, the Hierarchical Influences Model considers the individual level as a constituent of personal demographic characteristics, background factors, roles and experiences of the communicator within his/her domain of profession. Shoemaker and Reese propose an interrelation of these factors by arguing that “the communicator’s personal background and experiences are logically prior to their specific attitudes, values, belief” and they also precede “professional roles and ethical norms” (p. 209). One such element, according to them, is education. Education, particularly journalism education, has influencing roles that both as a general background factor and as a preparation of communicators for their career (p. 214). The interaction of the elements in this level alone require significant attention by itself so as to determine its composite influence on the entire hierarchical model.

Routine Level

“It is clear that routine and organisational levels overlap conceptually” (Shoemaker and Reese, 2014, p. 167). Shoemaker and Reese argues that “content emerges directly from the nature of how media work is organised” (p. 7). These routines and organisational arrangements that are recurring in nature over time, tend to form seemingly visible structures to which content must adhere. This defining structure could either be constraining or enabling or both at the same time. According to Shoemaker and Reese (2014), the routine level represents the immediate constraining or enabling structure of the individual, and the authors distinguish these from organisational level influences, which they argue are just larger patterns of the routine level influences that are more remote to the individual journalist. According to Shoemaker and Reese (2014), “ultimately routines are most important because they affect the social reality portrayed in media content” (p. 168). Shoemaker and Reese contend that routines are the practical response of journalists to difficulties, considering that they and their organisations continue to have very limited resources.

Organisational Level

Influences at the organisational level are similar to those at the routine level, but are more distinct from those at the individual level. Shoemaker and Reese (2014), where this level is concerned, highlight variables such as “ownership, policies, organisational roles, membership, inter-organisational interactions, bureaucratic structures, economic viability and stability” (p. 130). Distinguishing the organisational level of analysis from the routine level is not necessarily indicative of them being independent domains, however, there are “sufficiently unique attributes of each level” (p. 134) that could qualify them to be studied separately. The phenomena where modern organisational management has had members ultimately answering to owners and top management is significantly highlighted. This is where content and staff sharing within convergence platforms have become interlinked. The question that remains unanswered is how the structure of organisations reflect their allocation of resources, especially as a response to their environment. The practice that has so far been observed has signalled the danger of diminishing media autonomy, especially since the media must cohabit with those who finance it, or those who wield beneficial influence. As such, the power relations as they exists at this level relate closely to the influences these interconnections have exerted on content.

Social Institution Level

The distinguishing feature of this level from the three other levels is the fact that its factors lie outside both individuals and formal organisations themselves. According to Shoemaker and Reese (2014), this level illustrates that the media exist and operate within the inextricably connected power centres of society, which may either coercively or collectively shape content in many ways. The pertinent questions referred to at this level relate to ideology, inter-organisational field and outcomes of institutional forces.

There are proposals for considering media as a homogeneous political actor with counter influences on and from other actors and democracy in general. The field theory perspective speaks of how economic and cultural capital as a form of power has shaped specialised services into fields with peculiar internal homogeneity resulting from contingent historical path dependency.

Under this level, Shoemaker and Reese (2014) analyse sources as actors that shape power dynamics within the news selection decision. They argue that intermedia agenda-setting at some levels is a social institutional phenomenon. Shoemaker and Reese first discuss the blurring lines between the routine levels and social institution level when it comes to sources. They establish strongly that “sources of content wield important influence” (p. 108) on media content. When sources are routinised, they can be treated at the routine level. They justify the treatment of sources at social institutions level by emphasising the systemic influence they wield. Journalists are largely influenced by their sources in creating messages and this is quite clearly outlined by Gans (1979, p. 80) when he defines sources as “actors whom journalists observe or interview, including interviewees who appear on air or who are quoted in magazine articles and those who only supply background information or story suggestions.” When these sources become institutionalised then they take on systemic attributes and their influences fall squarely within the institutional level of analysis.

Social System Level

The social system level according to Shoemaker and Reese (2014) represents the base upon which the other levels rest because of its focus on the social structure and its cohesive tendencies. Grounded in Marxist thinking, the analysis at this stage relates strongly to the notion that society is inextricably linked to its social and historical context, a comprehensive appreciation of which is required to be able to establish in whose interest individuals, routines and social institutions eventually work. These are embedded within the question of value, interest and power. Media content portrays how social actors impose their will over other actors in society. However, the symbols created by these power relationships are not neutral forces because news is essentially about the powerful, either about their ideas or their interpretation of events.

The debate about globalisation occupies this level of analysis. While some scholars argue that globalisation is just an idea of increased emphasis on the general awareness of other places (Nohrstedt and Ottosen, 2000), others have taken a more critical look at the phenomenon of diffusion and reception of Western ideas from political, economic and cultural systems, broadly under the bracket of cultural imperialism (Paterson, 2017, 2011). For Michael Elasmer and Kathryn Bennett (2003), the major preoccupation about this area of research, so far, is the use of conspiracy theory as the prelude to discovering how “contemporary international intentions and behaviours of states have amounted to various forms of imperialism” (p. 2).

The complexities in the description of globalisation were clearly marked out by how different scholars perceived the increasing international social relations.

Anthony Giddens (2003) describes the phenomenon using the term “local transformation”, with which he explains the process of interaction between foreign media products and ideas from the world’s urban centres with other parts of the world. He argues that these relationships might be causally related, through a complex mechanism of global ties in the world markets. Diana Crane (2002) argues that these diffusions and receptions could be better delimited as “cultural globalisation”, which is the “transmission of various forms of media across national borders without necessarily impacting any homogeneous attributes because the parts” in the first place do not finely fit into the national context (p. 1). A more gradual approach to this conceptualisation of globalisation argues that the concept is happening but within and among “regional power centres” (Hawkins, 1997, p. 178). Therefore, globalisation represents a relationship between regions rather than nations. Crane (2002) further contends that these cultural regions are not necessarily dependent on geographical, linguistic and cultural proximity. Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini (2004) offer a rather basic rendition of globalisation by describing it as a term which helps scholars to avoid stating the obvious, which is the “expanding and imposing of single social imagery” (p. 27). Due to these complexities, Shoemaker and Reese (2014) discussed this level of analysis using four sub-systems: ideology, culture, economics and politics.

Towards a Theoretical Synergy

In this section, the theoretical and conceptual frameworks of the study are presented with diagrams detailing which theoretical lens provides which insights for a particular aspect of the study and how these individual insights could be linked together to provide the necessary answers for the research questions.

According to Miles et al. (2014), the framework could be “simple or elaborate, commonsensical or theory-driven, descriptive or causal” (p. 20). The study presented in this book adopts a simple theory-driven and descriptive framework. That is, the position of a theory within the framework shows which level of approach will be adopted in its analysis: descriptive, predictive or explanatory. The models employed incorporate both theoretical and conceptual ideas. They specify very important ideas, identify which relationships are likely to be meaningful, and pinpoint what data is required to deal with such meanings.

Conceptual Outlooks of Actors and Questions

Like Eilders (2006), Schwarz (2006), Johnson (1997), and Staab (1990), this study proposes that news selection research should be comprehensively approached at the micro-, meso- and macro-levels of analysis. The theory of newsworthiness is applied in this study to the behaviour of journalists in selecting the news. These are represented as micro-level investigations, which correspond with individual level analysis in the Shoemaker and Reese (2014) model. It is, however, crucial to note that the assumptions in this study differ in some ways in comparison with the entire argument of Shoemaker and Reese because the theory of newsworthiness was conceptualised significantly at the routine level in the Shoemaker and Reese model. However, Shoemaker and Reese argue that the day’s news is influenced by many factors and therefore “influences from all levels of analysis determine the day’s news; they are not as visible a target” (p. 172). The basic rationalisation in this study is that news factors and values are individual behaviour and attributes that most journalists gained through education, either in school or on the job. Even though most news organisation have compelling styles to which all newly employed journalists must adapt, the bottom line is that each journalist learns differently, and applies and interprets these values and styles differently. Due to this agency of cultural reception, I argue that news values and newsworthiness are significant at the individual level analysis, first and foremost. It does not imply that others could not use it at the routine and institutional levels since any individual behaviours routinised or institutionalised become routine and institutional level analysis respectively. The analysis here could be descriptive (percentages, means and correlations) or predictive (Golan, 2008; Wu, 2000).

In this study’s framework, the theory investigates organisational arrangements of these influences as the basis for news selection in Ghanaian media organisations. Even though in foreign news selection one can even at this point propose socio-cultural elements, this study considers these influences at the meso-level. The meso-level in this study corresponds to two levels of analysis in the Shoemaker and Reese Hierarchical Influences Model: routine and organisational levels. Elizabeth Skewes (2007), relying on the accounts of Richard Benedetto of USA Today, states that journalists especially on campaign press planes (p. 97):

don’t think in terms of what the public wants to know, how can I help them know. They think of it in terms of […] what does my colleague want to know? What can I show my colleagues that I know that they don’t know?

Intermedia agenda-setting has therefore become a real theoretical consideration for every news selection decision, and this is even further determined by a complex economic and ideological reasoning. Postcolonial theory is employed as a macro-level analytical tool in this study. It seeks to affirm that foreign news selection in Ghana has something to do with economic and political relationships; political ideology and social structure as well as several elements in the micro- and meso-levels which are consciously and inadvertently influenced by these vast and complex historical relationships. Thus, this ideological function is considered an overarching element in the theoretical framework which actually explains the superstructure of power and its dynamics when it comes to foreign news.

Frameworks of the Study

The study presented in this book considers the politics of communication as central to the understanding of our modern globalised society and calls for a more socially responsible problematisation of international communication. Figure 3.2 presents the theoretical framework, which blends the three different theories and levels of analysis.

Fig. 3.2 The study’s theoretical framework. Figure created by author (2020).

The three theories represented in the framework are the theory of newsworthiness as a micro-level analysis, which corresponds to individual level analysis in the Shoemaker and Reese hierarchical model. The theory is used to investigate the journalist’s behaviours and understanding of what makes news. The intermedia agenda-setting theory is used to explain all organisational arrangements that affected the news selection process at the meso-level, which is conceptualised to involve both routine and organisational level analysis in Shoemaker and Reese’s hierarchical model. The major questions of business and relationships have caused media organisations to depend on each other and these are interrogated at this level. Finally, the postcolonial theory provides an explication of how the other two levels are influenced by ideological elements at the super-structure level. The superimposition of the postcolonial theory is due to its nature as a critique and its use in this study as an explanatory level theory. The social institution and social system levels of analysis in Shoemaker and Reese model were collapsed together and embedded in the critical impulse of the postcolonial theory.

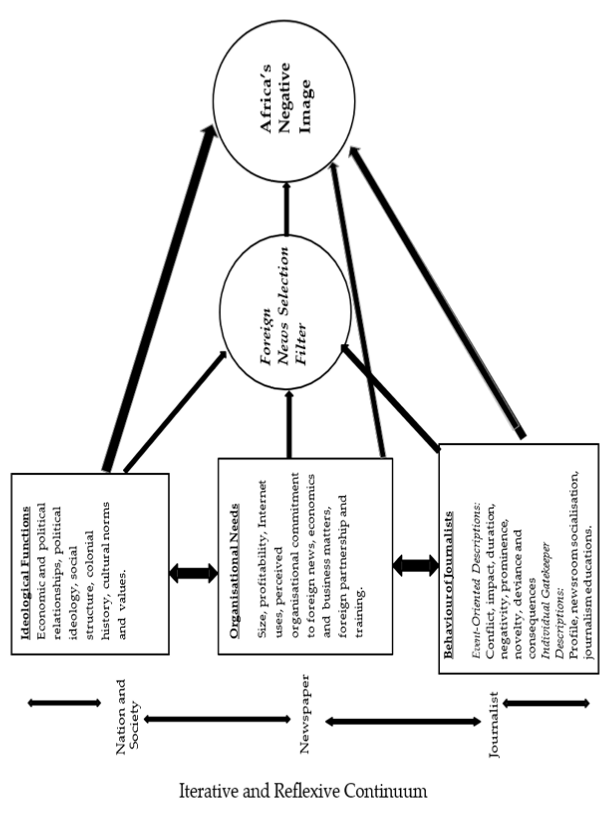

Figure 3.3 represents the conceptual framework of this study and it provides a cogent approach to tackle the data collection and analysis by showing subjects of interest, processes and the interrelationships between them. The framework proposes that three levels of factors do influence foreign news selection: journalist’s behaviour, organisational arrangements and ideological functions. Even though there is an assumption that the process begins from the micro-level to organisational level upwards, this continuum can be equally iterative and reflexive. This means the process can begin from an ideological or organisational level or one can move up and down along the continuum to seek illumination. In this framework, there is no clear way of measuring the potency of each stage of the process against the others since the path is fluid and construed in human choices. But the fundamental understanding is that no matter where the process begins in the continuum or whichever stage wields more power along the fluid path, the resultant effect is that foreign news selection decisions are determined by all these interdependent and interrelated mechanisms, which eventually affect Africa’s media image in the Ghanaian press.

The conceptual framework in Figure 3.3 is open to the assumption that the constituents of influence — individual journalists, organisational and ideological functions — can each independently contribute to the way Africa is covered in the Ghanaian press. As a result, the direction of influence from these three rectangular boxes is indicated in thick black, showing maximum influence. However, based on sociological dimensions of the framework, it is suggested that the influence of these three levels could either be measured jointly at the foreign news selection filter domain of the figure (where the influence of each level is dependent on the special circumstances of a particular day) or measured individually.

The individual measurement of these influences, in Figure 3.3, reflects subject-oriented and object-oriented debates, in which some scholars argue that news selection is a practice that ought to be investigated at the level of the journalists and their personal traits because there are sound criteria for objective news selections that journalists know well (micro-level). Others argue that news organisations significantly shape the journalists when they arrive at their premises and, as such, researchers must rather be concerned with how this socialisation takes place. The last argument hinges on the ideological elements that societal influences carry and that are exerted on the news institutions in general. In this study, all these ideas are incorporated in Figure 3.3, but with a new possibility where the news selection decision could be comprehensively described as the result of these three elements (influences), which meet at the foreign news selection filter stage.

Fig. 3.3 Conceptual framework. Figure created by author (2020).