13. Writing a Dissertation with Images, Sounds and Movements: Cinematic Bricolage

© 2021 Lena Redman, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0239.13

Backdrop to the Study

In presenting the overview of my doctoral thesis, in this chapter, I focus on cinematic bricolage as methodology for the generation, analysis and making meaning of research data. Cinematic bricolage methodology is characterized by the employment of heterogeneous tools and materials that are at hand, as well as by a multimodal system of representing the development of meaning.

In this chapter, I outline the methodology of cinematic bricolage with the use of alphabetic text and infographics. My point here is not to demonstrate my skills as a graphic artist that perhaps give me some advantage in presenting knowledge in an attractive way, and which might be deemed as nonessential. The infographics that I use here are not created to illustrate what is already articulated with words. Their presence here is my argument about the thought embodied in a particular form also being shaped by this form. The infographics—or any other digital mode(s) of expression chosen by the individual—and alphabetic text are two concentric rings of the same ripple, so to speak, that push at and are pushed by each other, resulting in the production of meaning through a continuous expansion of thought.

Fig. 1 Writing with infographics and alphabetic text as the concentric rings of a ripple, Lena Redman (August, 2019).

In this view, this chapter can be characterized as writing with infographics and alphabetic text.

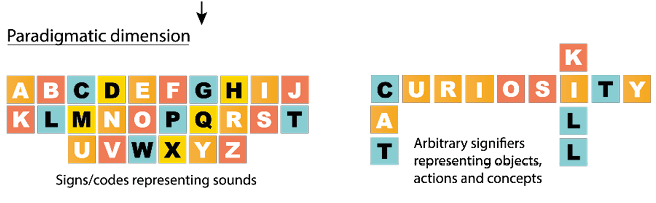

The correlation between the syntagmatic and paradigmatic dimensions in the production of meaning within Michael Halliday’s framework of systemic-functional linguistics (SFL), served as a departure platform for the study.1 The paradigmatic dimension is conceptualized as a system of signs and signifiers.

Fig. 2 Paradigmatic organization of linguistic signs, Lena Redman (October, 2020).

The paradigmatic dimension is a set of variables that is composed in ‘systemic patterns of choice’—syntagmatic structure, produces meaning.2 The encrypted interplay between the paradigmatic and syntagmatic dimensions constitutes a semiotic system which allows the content of mind to be transferred into an embodied form.

Fig. 3 Syntagmatic organization of linguistic signs, Lena Redman (October, 2020).

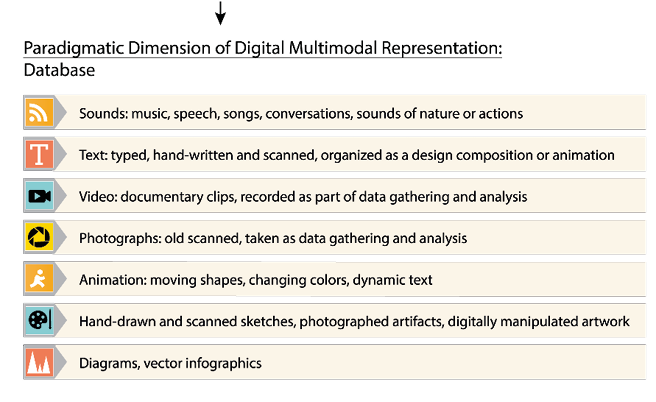

‘Any set of alternatives, together with its conditions of entry, constitutes a system in this technical sense’, Halliday maintains.3 In translating the semiotic system of language as conceptualized by Halliday into a semiotics of digital multimodality, the paradigmatic ‘set of alternatives’ is associated with database elements.

Fig. 4 Paradigmatic dimension of multimodal representation: database, Lena Redman (October, 2020).

‘Syntagmatic ordering in language’—that is, ‘conditions of entry’ in Halliday’s words—in digital multimodality is correlated with the cultural phenomenon of deep remixability.4 This is a ‘condition in which everything (not just the content of different media but also languages, techniques, metaphors, interfaces, etc.) can be remixed with everything’.5

Deep remixability is achieved with the new affordances of digital media among which modularity plays one of the central roles in representational practices. In the context of digital dissertations, modularity undoubtedly deserves more attention as a facilitator of a wide scope of possibilities. Modularity is identified as the ‘fractal structure of new media’.6 It allows for an independence of the parts within digital objects in assemblages. This means that the textual composition, when split into fractal elements and reconstructed as multimodal assemblages, may represent a new segment in the process of codifying systems of transferring an abstract idea into material form.

Fig. 5 Fractal structure of new media allows ‘deep remixability’ of syntagmatic and paradigmatic dimensions in making meaning, Lena Redman (October, 2020).

At the moment, the affordances of digital media permit little more than theorizing about the possibilities of writing with images, sounds and movements in the production of digital dissertations and for general knowledge-construction practices. Thus far, there is no suitable platform that could facilitate user-friendly, widespread engagement of intuitive remixing of text with other representational modalities without prior training in design and the use of specialized creative software. Coming as I do from the field of professional design, the recognition of the sharp dissonance between the possibilities that digital media offer for production of knowledge and their downright limited use in scholarly practice became the main point of concern for my dissertation.

To this end, the rationale for establishing an intuitive digital space where the dynamic embodiment of the contents of a mind with the involvement of signifying multimodal strategies by a scholar or student has first to be justified. In other words, do we really need such a thing as multimodality in writing doctoral or any other scholarly papers? Or is it just the sheer availability of new affordances that encourages trendy tendencies to experiment with the cutting-edge technology?

In the present chapter I would like to give a few examples where I felt I would not have arrived at certain insights without the employment of multimodal semiotics. But I can’t do this without briefly discussing three theoretical aspects which, in interplay with digital media, establish the merit of multimodal methodologies in generating, analyzing and presenting research data. These aspects are: privatized knowledge tools, cinematic writing and cinematic bricolage.

Privatized Knowledge Tools

It is sensible to assume that all contemporary dissertations are digital. To gain access to the global knowledge emporium—that is, to achieve an internationally affirmative evaluation of produced scholarship and thereby acquire an endorsement for its academic circulation—a modern dissertation cannot be anything but digital. As a rule, it should be written in Microsoft Word, presented with PowerPoint, Keynote or Prezi. Its literature review, for the most part, is based on articles retrieved from the internet and eBooks. The discussions and negotiations around the dissertation are often conducted online. This system can be termed a mainstream digital approach.

Even though said system makes a solid basis for a modern dissertation to be considered digital, the ontological potential of representational modes and the production of knowledge afforded by digital media remain widely unexplored. As Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore wrote: ‘We approach the new with the psychological conditioning and sensory responses to the old’.7 In the overwhelming ‘totality’ of digital environments, ‘we attach ourselves to the objects, to the flavor of the most recent past’ that is, to word-based methodologies, time-approved by traditional academic conventions.8

By virtue of inheriting a digital environment—even though many of us are labelled by Marc Pensky’s catchphrase as being not ‘natives’ but ‘digital immigrants’9—we ‘pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps’ to become one with the environment.10 One of the strings in this ‘pulling up by the bootstraps’ mode of living is striving for the existing media, using McLuhanese, to become ‘an extension of man’. Media, as McLuhan and Fiore wrote, ‘are so pervasive […] that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered’.11

Having the privatized knowledge tools literally in their hands, pockets, bags or in front of their eyes and on their desks, the knower is no longer limited by the knowledge collected and prescribed to them by someone else. The privatization of knowledge tools enables the knower to create their own path in the quest for intellectual expansion in accordance with their individual interests, capacities and personal experiences.

Reaching out for the construction of individualized forms of knowledge, the knower, for the first time in history, is afforded an opportunity to reconnect his/her interests with their immediate natural–sociocultural environments, expand and explore this reconnection through a diverse network of cultural resources, and distill the essence of their findings through the expressions of individually and endlessly hybridized variations.

Fig. 6 Extension of self-presence in the world by means of digital media, Lena Redman (May, 2016).

Cinematic Writing

The emerging genre, as I saw it, writing with images, sounds and movements, has a direct link to the term ‘cinematography’, as explained by Ed Sikov.12 Cinematography originates from two Greek words ‘kinesis (the root of cinema), meaning movement, and grapho, which means to write or record’. Therefore, Sikov suggested, ‘Writing with movement and light—[is] a great way to begin to think about the cinematographic content of motion pictures’.13 In the same vein, writing with images, sounds and movements can be termed cinematic writing.

In this I find a parallel between the call for an innovative use of the affordances of contemporary digital media—and, in particular, cinematic writing as one of the possible systemic manifestations for knowledge-production—and the invitation to see cinema as an avant-garde means of expression, as suggested by Alexandre Astruc in 1948. ‘I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of camera-stylo (camera-pen)’, wrote Astruc in his persuasive essay ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo’.14

‘A Descartes of today’, Astruc went on, ‘would already have shut himself up in his bedroom with a 16mm camera and some film, and would be writing his philosophy on film […] of such a kind that only the cinema could express it satisfactorily.’ Cinema, according to Astruc, was progressively transforming into a language by which a producer could externalize a meaning ‘as he does in the contemporary essay or novel’.15 Astruc’s article was a celebration of the technological potential of cinema to become an expression of an individual mind’s most private thoughts—shutting yourself up in your bedroom and responding to the fleeting moments of reality—something that could be conveyed only through the clusters of moving light and shapes entangled in the ever-present intricacy of sounds. Astruc rejoiced in the discovery of a new system of signification, where, as I see it, one mode of expression is just an uttered note, but the cluster of them is a philosophical poem of revealed consciousness.

The process of ‘revealing consciousness’ by means of merging logic and aesthetics, that is, transitioning from ‘mind-cinema’ by framing the abstract-implicit into the digital-explicit, became a core point of my study. In that regard, it was important to determine the boundary between the abstract thought and its material manifestation. What exactly is this space through which the transition takes place?

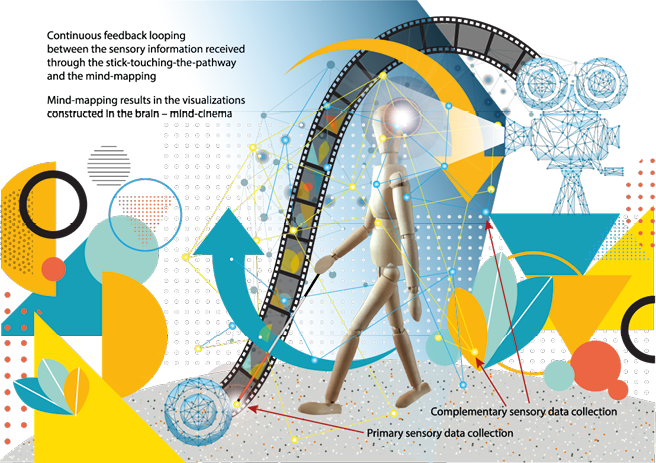

In searching for answers, the analogy of a blind man with a stick, suggested by Gregory Bateson, galvanized my imagination. ‘Where does the blind man’s self begin?’ asked Bateson. ‘At the tip of the stick? At the handle of the stick? Or at some point halfway up the stick?’16 The stick, Bateson decided, is a transmitter through which information about the pathway is being continuously broadcast into the man’s mind. The man’s touching the pathway with the tip of the stick is the primary channel for collecting and transmitting data. The sound that the touch produces, and the sounds, smells and general feelings coming from the surroundings, constitute complementary data-gathering. The senses are engaged in an ongoing collaboration, resulting in a ‘systemic circuit’ that runs through the stick, maps the pathway in the man’s mind, like a movie projector, and reveals new cinema frames associated with each new step that ‘determines the blind man’s locomotion’.17

Fig. 7 A looping feedback produced by the blind man’s walking stick touching a pathway and his ‘mind-cinema’, determining his locomotion, Lena Redman (April, 2019).

The man, the stick and the pathway, together, are ‘a self-corrective unit’.18 The man’s every next step is the result of continuous feedback looping between the information received through the sensory circuit and the mind-cinema playing in his head. This network is not confined by the contours of the head or the body but includes the pathway and the stick through which the information travels, as well as the surroundings, and that is what determines the next move.

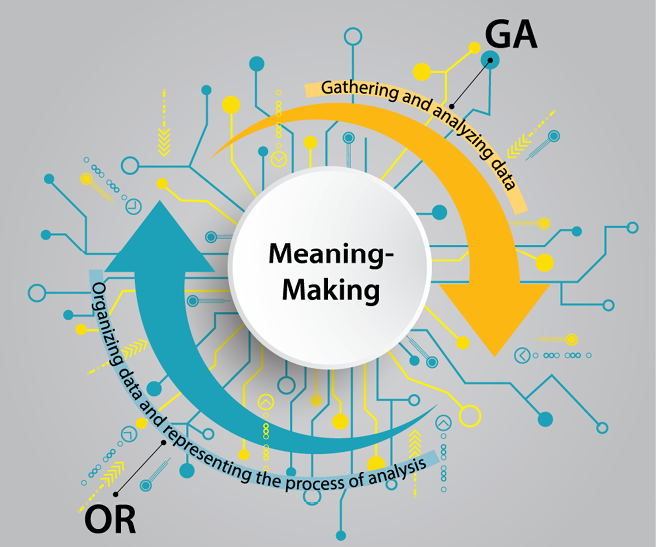

Translating this into a meaning-making activity, we can say that every data-organizational and representational move of gathered and analyzed data creates a circuit towards meaning-clarification; and every cleared segment of meaning affects the next step in the organization and representation of data. In other words, the process of ideation is achieved by step-by-step progressive unfolding—a circuit of gathered and analyzed data and self-correcting/self-organizing feedback loops.

Fig. 8 Continuous feedback looping between gathering/analyzing data and organizing and representing the process of analysis, Lena Redman (April, 2019).

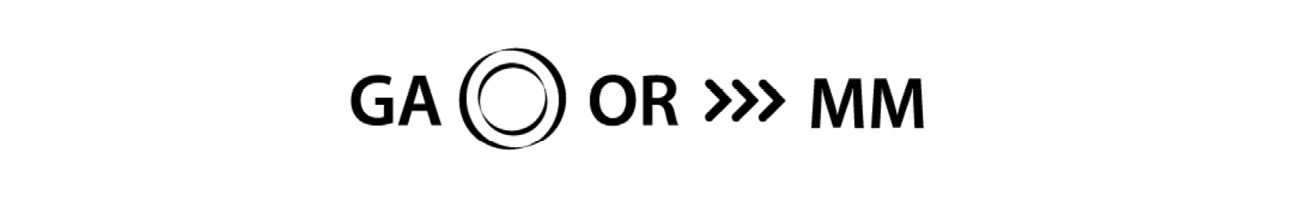

This can be reduced to a formula where gathering and analyzing data, positioned in feedback circuits with organizing data and representing the processes of analysis, leads to meaning-making:

Fig. 9 Symbolic representation of the feedback loops between gathering/analyzing data and its organizing/representing that leads to construction of meaning, Lena Redman (April, 2019).

So, in what ways has this equation affected my epistemological quest?

Cinematic Bricolage

The equation GA < > OR >>> MM—that is, the Gathering and Analyzing < > Organizing and Representing circuit resulting in the step-by-step production of Meaning-Making—gave rise to a question: to what degree does such an approach allow the exploration of the metacognitive function of mind that results in the construction of new knowledge?

The complexity and number of theoretical underpinnings—the structural functionality of semiotics, cinematic writing, the privatization of the means of knowledge production, media as extension of man, and deep remixability—necessitated the imposition of structural clarity, which I found in the adoption of Lévi-Strauss’s research methodology that ‘is commonly called “bricolage” in French’.19 The bricoleur, Lévi-Strauss notes, ‘has no precise equivalent in English’. She/he is ‘a kind of professional do-it-yourself’ person who ‘uses devious means compared to those of a craftsman’.20

The bricoleur mode of operation differs from the engineer’s practice. The engineer establishes a question and finds a solution in a planned sequence.

The bricoleur, according to Lévi-Strauss, explores ‘the heterogeneous objects of which his treasury is composed to discover what each of them could “signify” and so contribute to the definition of a set which has yet to materialize’.21 In the context of my dissertation, the ‘set that has yet to materialize’ was an anticipated cluster of insights as to how multimodal semiotics can affect an epistemological progression.

Fig. 10 Seeing hetero-geneous objects as ‘op-erators’ in constructing meaning with diverse means, Lena Redman (December, 2016).

To this end, I decided to explore the representational process of my childhood memories of growing up in Soviet Russia. How do the reorganization of old photographs, objects of personal sentimental value, memories, songs, music, movies from childhood, old video clips from YouTube and other fragments of data organized in a deep remixability technique influence knowledge-related discoveries?

Using multimodality as a ‘blind man’s walking stick’ what would I find that I didn’t know before and perhaps wouldn’t have found if I didn’t use multimodal tools?

Fig. 11 ‘Discovering’ my own past by representing it with the existing objects and memories, Lena Redman (February, 2016).

Bricolage is an activity that is subject to the given context and a ‘universe of instruments [that] is closed’. The game is ‘always to make do with “whatever is at hand”’. Accordingly, the bricoleur’s toolbox and the availability of materials are limited. At the same time, the scope of the tools and materials is heterogeneous in the sense that it is ‘the contingent result of all the occasions’. In other words, in examining the use of digital media to write a dissertation, my digital toolbox—mobile phone, iPad, computer and the internet—was limited in the sense that these tools were not specifically designed for my exact area of study, but their utility was based on the principle that ‘they may always come in handy’.22 At the same time, my set of tools enabled a wide scope of representational heterogeneity.

Fig. 12 A slide-show of some pages from the thesis written with images, sounds and movements in an ePub format, Lena Redman (February, 2019).

Each page was a composition of multimodal components. Objects appeared and moved in the spaces allocated for them—across the page, behind the text or between the lines; sounds came out, video elements emerged and new text boxes materialized. The focus of analysis was adjusted not so much according to the reception of multimodal compositions by the reader, but rather according to how the engagement with various modes of representation affected the knowledge-producer’s cognitive activity.

To avoid communicational complexity, I categorized photographs, scans and other images, music, songs and other database elements, as bricoles. Each of the bricoles, borrowing from Lévi-Strauss, ‘represent[s] a set of actual and possible relations: they are “operators”’.23

What should I expect of the operational functionality of the bricoles in conditions of deep remixability where they are deconstructed and reconstructed in the interplay with other fragments of other bricoles in completely new assemblages?

Gathering / Analyzing < > Organizing / Representing >>> Meaning-Making

Looking for Crows

The implementation of multimodal remixes allowed me to notice things that, I believe, would usually be ignored. These were fleeting sensorial moments of a suddenly remembered smell or taste; movements or feelings that my mind produced in response to the awakening of memories. The question emerged: why, when remembering different episodes from my Soviet childhood, did sensorial manifestations—images of crow(s), creeping movements of pipe or cigarette smoke, smells of heavy coats wet from thawing snow—make their sometimes clear, sometimes vague, but nevertheless persistent appearances on the ‘screen’ of my ‘mind-cinema’, as if the whole fabric of the screen was woven out of their meaningful relevance?

What if I integrate an animated crow flying behind the typed text and apply the sound of its cawing, mimicking its presence interwoven into my thoughts? How would the conversion of the implicit into the visible and auditory affect the process of meaning-making? Why does it make me ‘hear’ the Beatles singing:

Blackbird singing in the dead of night

Take these broken wings and learn to fly…?

I observed very attentively my mind-cinema responding to my activity working with the multimodal bricoles. I used my mobile phone for taking pictures, and at this stage of the project, crows became my models. I recorded various sounds, and crows’ cawing caught my interest. Integrating recorded bits into the pages of writing, I thought that the fact that one of the sound recordings also contained the sound of a random car braking was interesting. I didn’t discard it but instead added an image of a car and also incorporated The Beatles’ ‘Blackbird’ song in the background. I tried to avoid elitist thoughts, attempting to block nothing that appeared important even if it seemed nonsensical.

Fig. 13 Connecting the dots of associations, memories and newly collected information, Lena Redman (August, 2016).

A ‘whirl of catching and being caught’, Tim Ingold wrote in his philosophically-poetical The Life of Lines.24 In trying to catch meaning, the meaning ‘catches you in your own mind’—that’s how I felt in allowing my thoughts taking digital form.

I observed the dynamic circuit as working on the written text inspired the generation of certain images, movements and sounds, and the generation, categorization, curation, and their manipulation influenced alterations in the written text which, in turn, resulted in gaining insights. It allowed me to immerse myself in the depth of memory where some floating fragments were clipped back into their right places, like disembodied bits of jigsaw puzzles.

Catching the meaning of the profound sadness of the crow’s presence, I understood that it had a deep-rooted cultural significance. The ‘black crow’ was the term for a vehicle (GAZ M-1) that, during Stalin’s time, took people to places of no return. Although the ‘black crow’ van ceased to exist in the time of my childhood, the term was prominently embedded into cultural representations in movies, books and stories. In my child-mind, the term acquired the literal representation of a bird—a crow.

Smoke Screen

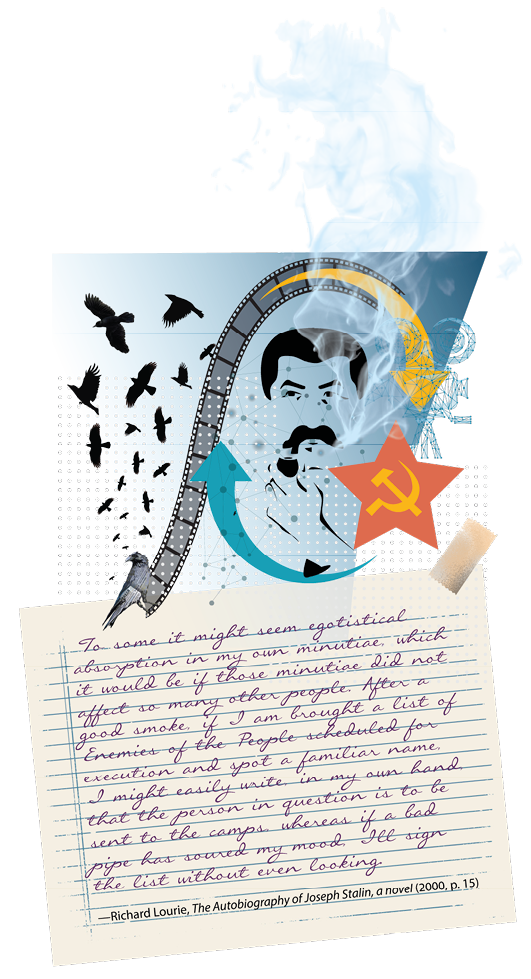

Fig. 14 Making connections between the crows and pipe smoke, Lena Redman (May, 2016).

Not less revealing and equally gloomy was the revelation of cultural symbolism in the image of pipe smoke. The sluggishly moving streams spreading behind the layer of typed text were ‘catching’ something obscure but exceedingly disturbing. ‘Being caught’ in looking for images of Stalin’s ‘black crow’ van, I became intrigued by the images of Stalin himself and especially by the fact that he was quite often photographed smoking a pipe. There was such an air of significance around the whole thing that it made me even more curious. I started looking for more images and information on the topic.

In Graeme Gill, I read about Victor Deni’s illustration that was reproduced in the central Soviet newspaper Pravda (1939), where the generals of the White Guard are shown ‘being blown away by the smoke of Stalin’s pipe’.25

I was bewildered by the doctrinal incongruousness of the image. The whole country was heavily conditioned by the Marxist ideology of radical materialism. And here we had the ‘Father of the Nation’ being portrayed as a magician blowing out some sort of spell on the generals.

But the more images I saw and the more I read about Stalin, the more I came to understand that despite Soviet ideology never tolerating anything supernatural, Stalin himself was portrayed as having superhuman abilities.

It came into focus that Stalin’s pipe was actually one of the visual symbols endowing him with ‘supernatural power’ as he kept brutal control of the country with a population of more than one hundred million at the time. In his historical novel about Stalin, Richard Lourie depicts him as an egocentric dictator for whom the quality of a taste of smoke on his tongue would determine the destinies of thousands of people and their families.26

The movement in this case, as a mode of representation, was that functional aspect that Lévi-Strauss described as an operator that carried in itself possible relations in recognition of meaning. The pipe smoke mediated Stalin’s personality, shrouded in secrecy and ultimate distrust of anyone, and his stealthily well-calculated actions. Not the smoke itself, but its spreading, its continuous thickening, represented heavy oppression and lack of air to breathe for anyone who found themselves under that stealthily moving cloud. Stalin’s style of moving and speaking was slow, like his pipe’s smoke spreading far away around the whole country, screening the truth and making the cruel lie appear to be a necessity for survival. Like a spider who catches its victims with a hidden web, Stalin dispersed his manipulative smoky nets all over Russia and kept it tight in those nets for years.

Bringing Forth the World Together with Others

The most heartfelt discovery that my multimodal probe provided me with was the epistemological aspect which Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela described as ‘the world that we bring forth with others’. In other words, every act of knowing ‘is a structural dance in the choreography of coexistence’ with others.27 To discuss this, I use an ongoing incorporation of—what I felt was the ‘appropriate’ representation—Beatles songs into the bricolage of probes. While assembling animations to represent my imaginary meeting with ‘the fathers of communism’, and in particular with Lenin, I felt that juxtaposing the ‘Internationale’ performed in German and The Beatles’ ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ was an absolutely right choice in depicting the contrast.

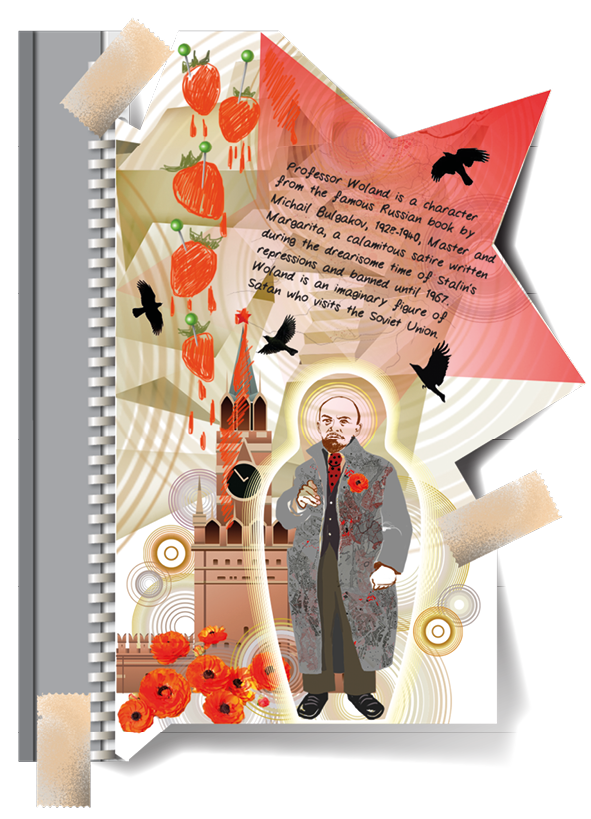

Fig. 15 Imaginary meeting with the fathers of communism, Lena Redman (May, 2015).

Fig. 16 Sanctification of Lenin by the use of fear and oppression, Lena Redman (April, 2016).

My intention was to create the sense of a collision by using my childhood’s most innocent and happiest moments that, in my particular case, can be metaphorically expressed with the digital ‘strokes’ portraying a garden, a clear sky, the buzzing of bees and fluttering of butterflies, the fragrance of strawberries ripening in the sun. On the other hand was the harsh austerity and hidden cruelty of Soviet reality. The ‘Internationale’ sung in German is a reflection of Lenin’s ‘specific admiration for Germany that was enormous’.28 Lenin was raised by a mother who was of German and Swedish ancestry and who stayed loyal to German cultural traditions.29 Lenin also lived for a long period of time in Germany and liked the culture. ‘He wanted the West too to change. There had to be a European socialist revolution that would sweep away the whole capitalist order’.30 Lenin appears not to have been very fond of Russians, who in his opinion, are talented people but ‘have a lazy mentality’.31 The ‘Internationale’ performed in German sounds to me like the reverberation of Lenin’s ultimate goal, in which Russians ‘were sorry specimens that populated the corrupt world’32 and were used as disposable material for the first trial of a larger and more important world scheme.

The images of smashed strawberries, sounds of a battle, and together with them the song ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ from the movie Across the Universe,33 which is based on The Beatles’ songs, came to my mind as a concrete thread to patch together fragments of simple naiveness and corrupt barbarity. The question that I asked myself was, why did the choice of something to mediate my feelings so often fall on The Beatles’ songs?

Fig. 17 ‘Cut-outs’ from the pages of the thesis, Lena Redman (May, 2016).

In the early 1970s my older brother bought on the black market a self-produced Abbey Road tape-cassette, paying more than the equivalent of half the average monthly salary. We played it quietly, not to annoy mum and taking care that a censorious ear would not catch the tune.

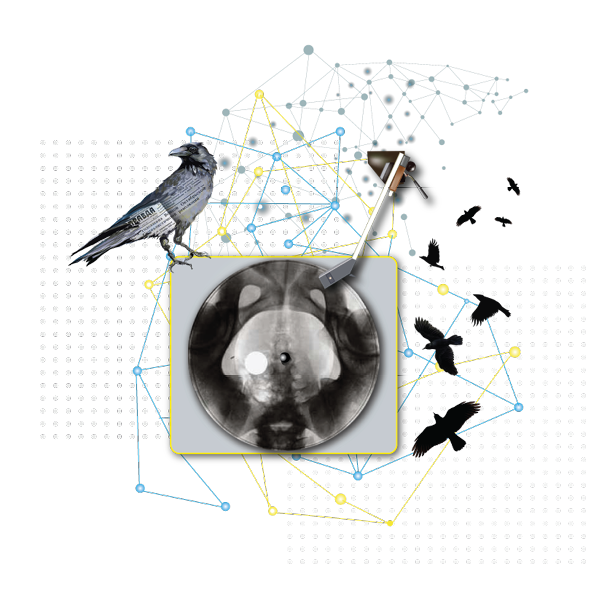

Earlier still, and under much more dangerous circumstances, I remember the black-market circulation of discarded medical X-ray films with Beatles songs etched on them. Pity I never had one. It could cost you not just two weeks’ wages but also your studentship or job, or even worse, depending on the circumstances. A very helpful thing was that those ‘bones’ records were easy to bend and hide in the sleeve of your coat.

The more information I found on the topic and the more I retrieved facts and events from my own memory, the more I was astounded with the widespread and compelling Beatles subculture in Soviet Russia that I always knew I was part of, but never realized its tremendous cultural significance.

I always knew that my answer to a run-of-the-mill question about what music album I would take with myself to a deserted island would be an immediate Abbey Road. The choice, however, is not based purely on aesthetic preferences.

Fig. 18 A record ‘on bones’, Lena Redman (April, 2016).

During my study, not without surprise and excitement, I came across Leslie Woodhead’s book, How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin. Bewildered, I read about the parallel universe where my own generation grew up. Many of Woodhead’s characters call the Beatles fans (us!) the Soviet Beatles Kids. It was only through my multimodal probing that I came to realize how great a contribution our souls and minds, rocked by The Beatles’ music, added to rocking the Kremlin and shaking Soviet Potemkin villages’ walls. In the case of the Berlin Wall—literally. We did not even realise that when we (secretly from our parents) were tuning in to the waves of Radio Liberty, catching familiar tunes with poorly recognised English words, and nevertheless recognised ‘Hey Jude, don’t be afraid…’, we were joining the vibration of another world, free from smothering ideological coercion. We were getting less and less afraid to stand against the fake façades of Soviet constructions. When our boys were growing their hair like The Beatles, and were very badly treated for this, along with their hair their defiance was growing as well. As one of the Woodhead’s characters, Kolya Vasin, recalls:

‘The policeman said, “You are not Soviet man! You are living like a Western man!” And he grabbed my hair.’ The memory of how the cop dragged him along the platform by his hair while dozens of people stared and laughed was branded into him. ‘I was almost crying from the pain, but I had to keep silent. I was afraid the man would drag me off to prison’.34

Unfortunately, as far as I know, people of that Soviet Beatles Kids subculture never managed to stay back in their home country. Every one among those whom I personally know and would identify as one of the Soviet Beatles Kids, lives at the moment somewhere outside contemporary Russia. As Woodhead observes: ‘Millions of kids across the Soviet Union must have shared something of Vasin’s despair about their society, strangers in their own country’.35

Fig. 19 The Beatles shook the Kremlin’s walls, Lena Redman (May, 2016).

It feels as if the Beatles were that voice that made us open our eyes and look critically around. They made us test the ground under our feet and realise that there was no solid substance underneath the artificially constructed surface. It was all just a Potemkin village. This realisation has pushed us out of the country.

Fig. 20 Inspired by The Beatles, running the Soviet Union, Lena Redman (September, 2016).

So we sailed up to the sun

Till we found a sea of green

And we lived beneath the waves

In our yellow submarine…

This is an example of how technology has facilitated the penetration of the Iron Curtain, as Kolya Vasin in Woodhead’s book says: ‘After the Beatles, the Iron Curtain was like a fence with holes. That was our secret. We breathed through those holes’.36 The radio played a massive role in this process. Searching for our favourite music on Radio Liberty, we were also given a chance to hear about things in our own country that were hidden from us. These two aspects—the information disclosed about our society and our emotional response to The Beatles’ music—were tightly intertwined in our mental schemata. They eventually became inseparable.

The invention of the ‘records on bones’ was one of the manifestations of growing resistance to the regime. Its symbolical implication, as if we were recording ‘the spirit of freedom on people’s bones’, is an indication of the rigor of the subcultural movement. Medical images recorded on film using electromagnetic radiation, together with the technology of etching sounds onto them, made it possible to disseminate the songs.

Conclusion

In those circumstances, with the Beatles’ music influencing the young generation of Soviet Russia in the seventies, the technology was a conduit that enabled the flow of independent thought into oppressed reality. Comparing the technological possibilities that were available for the Soviet Beatles Kids with those that are easily accessible for young people today, I think of the great possibilities that education has at its disposal. Maybe the modern system of teaching and learning, designed to guide young people in the ‘right’ direction and screen them from the troubled world, is in reality the Iron Curtain that prevents them from breathing fresh air, a Potemkin village façade that keeps people from finding out and constructing their own truth about themselves and the world they live in.

In the area of knowledge generation, I see digital media—and cinematic bricolage, as one of its by-products—as an emancipating force available for scholars and students alike to use in their exploration of reality. In addressing this, I join my voice with those of Joe Kincheloe and Shirley Steinberg,37 Kincheloe (2003)38 and Kincheloe and Kathleen Berry (2004),39 who see teachers and students as producers of their own knowledge. Kincheloe and Steinberg argue that self-produced knowledge makes people:

[…] pursue a reflective relationship to their everyday experiences, they gain the ability to explore the hidden forces that have shaped their lives […] to awaken themselves from a mainstream dream with unexamined landscape of knowledge and consciousness construction […]40

Examining beliefs, social practices, dominant standpoints, using materials and tools they have at hand in their given context, and mediating meaning with digital media, cinematic bricoleurs may produce alternative bodies of knowledge. Cinematic bricoleurs may expose the correspondence between the phenomenon they are looking at and the social structures it is embedded in. Throughout this process, they may learn to form their own critical view and find strategies for its advocacy. Speaking metaphorically, they may invent their own ‘records on bones’ by expressing what previously was obscured from view, using whatever is in their repertoire. This results in the formation of holes in the existing Potemkin villages, making reality easier to see, access, understand and alter when necessary.

The methodology of cinematic bricolage, with its feedback loops of ‘catching and being caught’, provokes contingent situations and engenders conditions that allow one to take advantage of what was invisible at the start of the project. Such logic was expressed by one of the architects of the Social Study of Information Systems Research, Claudio Cibbora:

Curiously enough, successful information systems that are developed stem not from formal theories and structured methodologies, or from deliberate designs, but rather from chance events and improvised, serendipitous applications, which are not planned ex ante, and are often introduced by the users themselves through reinvention and bricolage; indeed, innovation happens by taking unanticipated paths and timing and assuming a local, apparently inconspicuous character at the outset.41

Embracing the process of epistemological innovation with its principle of a self-organizing feedback circuitry, the quotation above can be considered as describing a kinetic force that takes us to the notion of ‘churning ripplework’, where the circularities push at and pull against each other, causing shape bending and curving, producing multiple overlapping, and thus creating individually hybridized patterns of knowledge.

My train of logic in writing this chapter is tightly intertwined with visualizations and graphic representations and may appear interesting to some and perhaps incongruous to others, on the grounds that such an approach is incompatible with traditional dissertation writing. Returning to the discussion of the paradigmatic and syntagmatic system of meaning-making, I have to argue that the logic of my approach lies in adding images and graphic elements to a set of traditional signifiers (words), and organizing them in a spatial relation that helps to proceed with very individual way of gaining insights. My argument is not for a professional artistic use of images, sounds and movements—they can be replaced with stick figures, simple shapes, humming and basic moves of the objects within a digital space—but for an analysis of the metacognition that the engagement with multimodality evokes.

My personal ‘professionalism’ in the use of images and infographics was helpful because it gave me confidence in their employment and, consequently, allowed me to explore the merger of multisystemic signification, where linguistic and visual elements (audio and movements that I used in my dissertation) enabled me to reach, as I believe, the deeper levels of metacognitive processes.

Such knowledge production methodology is oriented towards forging a uniquely personalized repertoire in reaching an intended goal. The cinematic knower/bricoleur starts with retrospection,42 examining how ‘to make do’43 with the accessible tools and obtainable materials within the given context and according to personal competencies. The knower then works towards the expansion of his/her competencies and skills by connecting fragments of knowledge and their intuitive interpretation, the data from disparate domains, and pulling them into a unique and coherent narrative.

The bricoleur’s improvisations are prompted by his/her individual agentic skills in finding resourceful means—or, as Lévi-Strauss puts it, ‘devious means’44—of negotiating between his/her intention, the availability of resources and skills and the affordances of tools. From this perspective, the methodology of cinematic bricolage emerges not from the professionalism of a craftsman but from a DIY process of organization of fragments from diverse theoretical and practical fields, and by means of the utilization of a uniquely personal range of skills and strategies.

Bibliography

Astruc, Alexandre, ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: Le Caméra-Stylo’, New Wave Film.com, http://www.newwavefilm.com/about/camera-stylo-astruc.shtml

Avgerou, Chrisanthi, Giovan F. Lanzara and Leslie P. Willcocks, Bricolage, Care and Information: Claudio Ciborra’s Leagcy in Information Systems Research (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Bateson, Gregory, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972).

Campanelli, Vito, ‘Toward a Remix Culture: An Existential Perspective’, in The Routledge Companion to Remix Studies, ed. by Eduardo Navas et al. (New York: Taylor & Frances Group, 2015), pp. 68–82.

Gill, Graeme, Symbols and Legitimacy in Soviet Politics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Halliday, Michael A. K., Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014).

Ingold, Tim, The Life of Lines (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2015).

Kincheloe, Joe L., Teachers as Researchers: Qualitative Inquiry as a Path to Empowerment (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2003).

Kincheloe, Joe, L., and Kathleen S. Berry, Rigor and Complexity in Educational Research: Conceptualising the Bricolage (London: Open University Press, 2004).

Kincheloe, Joe L., and Shirley R. Steinberg, Students as Researchers: Creating Classrooms that Matter (New York: Taylor & Francis e-Library, 1998).

Lévi-Strauss, Claude, The Savage Mind, trans. by George Weidenfield (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

Lourie, Richard, The Autobiography of Joseph Stalin: A Novel (Boston, MA: Da Capo Press, 2000).

Manovich, Lev, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002).

Maturana, Humberto R., and Francisco J. Varela, The Tree of Knowledge (Boston: Shambhala, 1998).

McLuhan, Marshall, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Corte Madera: Gingko Press, 1964).

McLuhan, Marshall, and Quentin Fiore, The Medium is the Message (Corte Madera: Gingko Press, 1967).

Pensky, Marc, ‘Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants’, On the Horizon, 9.5 (2001), 1–6, https://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Pipes, Richard, Communism: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2003).

Service, Robert, Lenin: A Biography (London: Pan Macmillan, 2002).

Sikov, Ed, Film Studies: An Introduction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

Taymor, Julie, dir., Across the Universe (Sony Pictures Releasing, 2007).

Woodhead, Lesley, How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin: The Untold Story of a Noisy Revolution (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013).

Young, Cathy, ‘Stalin’s Allied Atrocities’ (March 12, 1990), Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/03/12/stalins-allied-atrocities/3855ede8-597f-45fd-84b3-e32d1dba59ad/

1 Michael A. K. Halliday, Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014).

2 Ibid., loc. 897.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Vito Campanelli, ‘Toward a Remix Culture: An Existential Perspective’, in The Routledge Companion to Remix Studies, ed. by Eduardo Navas et al. (New York: Taylor & Frances Group, 2015), pp. 68–82 (p. 73).

6 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002), p. 30.

7 Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, The Medium is the Message (Corte Madera: Gingko Press, 1967), p. 94.

8 Ibid., p. 74.

9 Marc Pensky, ‘Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants’, On the Horizon, 9.5 (2001), 1–6, https://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

10 Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela, The Tree of Knowledge (Boston: Shambhala, 1998), pp. 46–47.

11 McLuhan and Fiore, The Medium is the Message, p. 26.

12 Ed Sikov, Film Studies: An Introduction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

13 Ibid., loc. 953.

14 Alexandre Astruc, ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: Le Caméra-Stylo’, New Wave Film.com, http://www.newwavefilm.com/about/camera-stylo-astruc.shtml

15 Ibid.

16 Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972), p. 318.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid., p. 319.

19 Claude Lévi Strauss, The Savage Mind, trans. by George Weidenfield (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), p. 16.

20 Ibid., p. 17.

21 Ibid., p. 18.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Tim Ingold, The Life of Lines (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2015), p. 7.

25 Graeme Gill, Symbols and Legitimacy in Soviet Politics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 301.

26 Richard Lourie, The Autobiography of Joseph Stalin: A Novel (Boston, MA: Da Capo Press, 2000).

27 Maturana and Varela, The Tree of Knowledge, p. 248.

28 Robert Service, Lenin: A Biography (London: Pan Macmillan, 2002), loc. 252.

29 Ibid., loc. 496.

30 Ibid., loc. 252.

31 Ibid., loc. 694.

32 Richard Pipes, Communism: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2003), p. 69.

33 Julie Taymor, dir., Across the Universe (Sony Pictures Releasing, 2007).

34 Lesley Woodhead, How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin: The Untold Story of a Noisy Revolution (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), loc. 1886.

35 Ibid., loc. 1052.

36 Ibid.

37 Joe L. Kincheloe and Shirley R. Steinberg, Students as Researchers: Creating Classrooms that Matter (New York: Taylor & Francis e-Library, 1998).

38 Joe L. Kincheloe, Teachers as Researchers: Qualitative Inquiry as a Path to Empowerment (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2003).

39 Joe L. Kincheloe and Kathleen Berry, Rigour and Complexity in Educational Research: Conceptualising the Bricolage (London: Open University Press, 2004).

40 Ibid., p. 3.

41 As cited in Chrisanthi Avgerou, Giovan F. Lanzara and Leslie P. Willcocks, Bricolage, Care and Information: Claudio Ciborra’s Leagcy in Information Systems Research (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), p. 8.

42 Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind, p. 18.

43 Ibid., p. 17.

44 Ibid., p. 16.