3. The Digital Monograph? Key Issues in Evaluation

© 2021 Virginia Kuhn, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0239.03

Faculty members who work in digital media or digital humanities should be prepared to make explicit the results, theoretical underpinnings, and intellectual rigor of their work.

MLA Guidelines for Tenure and Promotion, 2012.1

‘This is a hobby. Don’t let it distract you from the real work’. This well-intentioned warning issued by one of my graduate advisors came at the end of a workshop we’d just finished on digitizing video from tape. It was 2004 and YouTube did not yet exist but I was determined to get images into my work, sensing it would enrich my doctoral research significantly, even if I couldn’t articulate exactly how and why at the time: on the one hand, my research was (and remains) engaged with issues of power and privilege. I investigate structural issues around race and gender—both very visual concerns—and the ways that they inform and are informed by the technologies used for communication and expression. This made it vital to actuate my argument with images. On the other hand, power differentials and structural inequities function best, and sometimes only, when they are invisible. In this light, any attempt to uncover power via the presumed literality or indexicality of visual media, by its very nature, undermines the complexities of power structures; the camera is not objective, nor are its photographic outputs comprehensive, and so the use of images must be carefully considered.

Ultimately, since my larger argument hinged on the premise that digital technologies are nearly as amenable to images as they are to words, it was compulsory to use image-based evidence and actually deploy this emergent visual language. And of course, nearly two decades later, images and video are so numerous online as to make the notion of their manipulation in a critical text an imperative.

Still, my advisor’s warning reveals a key concern: how do graduate students—and academics more generally—decide how and where to focus their energy in a competitive environment that is built upon its members feeling they are never doing enough? How much time can we really afford to spend on learning a coding language, for instance, knowing we’ll never become a developer even if we become a semi-decent programmer? And which programming languages or software applications are worth learning? Will the time spent translate into more insightful scholarship and how do we make that calculation? These decisions have real career implications, particularly since such an endeavor will likely not be seen as analogous to visiting an archive or spending time learning another natural language, the ‘real work’ of the humanities.

Perhaps more profoundly, however, my advisor’s warning reveals the stubborn boundary between formal and conceptual elements in academic work: as such, the workshop we had completed which focused on manipulating the formal qualities of film via its digitization was seen as extraneous to its actual study and scholarship—the ‘real’ work of writing about film, not with it. Indeed, the form/content divide has held its own for hundreds of years, and to traverse it requires an explicit justification.

When creating a natively digital dissertation, this rationale is especially vital since there is little consensus on how to properly assess this work; as such, the chances of being penalized for these efforts are quite high. The digital text that carries the same intellectual heft of a traditional dissertation has not been identified with any precision, nor are even its general contours widely agreed upon. As the epigraph with which I opened suggests, and more than a decade of supervising dissertations confirms, more often than not, it continues to be the responsibility of the student to explain the ‘results, theoretical underpinnings and the intellectual rigor’ of their digital work. In what follows then, I suggest a rubric for evaluating born-digital scholarship—that which could not be done on paper—to help dissertation students articulate the merits of their work and, in the process, potentially educate their faculty advisors, or, at the very least, help advisors to at least ask the right questions of a student who wishes to pursue a full digital dissertation.

The Digital Dissertation: Archive?

Researching, planning and producing a dissertation is difficult enough, and adding a digital component increases the difficulty considerably since the author must not only make a conceptual contribution but must also reckon with the formal considerations of the text. In fact, these formal elements are vitally important since they are challenged anytime one breaks away from the traditional dissertation format. That said, these unconventional formats have few if any models: while born-digital dissertations are becoming more numerous, they are often inaccessible and typically archived in analogue apparatuses rather than in their native format.2 For example, a dissertation created in the web-based multimedia-authoring platform Scalar, is now archived in my university’s library as a vast series of static images (JPGs), which are mere screenshots of each ‘page’ of the dissertation. Obviously, this renders much of the work inaccessible—there can be no dynamic text, no audio, no moving images, no roll-over displays, no working links, nor any real sense of the linking structure. In short, this archiving actually works in direct opposition to the very form of the dissertation which, if done well, is key to its conceptual framework.

The lack of access to completed, natively digital dissertations presents difficulties for graduate students as well as their advisors who seek guidance in the construction and defense of these unconventional texts. This includes my own digital dissertation, which is barely archived and was completed in a client-based program that is not browser based.3 Indeed, my nine-month struggle to retain my doctorate when I refused to offer a print-based, image-cleared version acceptable to ProQuest’s archival policies ended only when I was able to convince all parties that the key arguments of the work would not hold up in an analogue environment. Quite frankly, the pressure to create some sort of print version was intense, but I had the luxury of being able to hold out and, as such, felt I could not back down, if only to establish a precedent for others whose fate was more precarious than my own.

After a brief overview of my path to establish context, I focus here on a rubric that has proven useful in evaluating digital scholarship for more than a decade.4 Its parameters have been reviewed and streamlined slightly over the years and as a result, it offers just enough structure to ensure academic rigor, but is flexible enough to allow for fresh thinking and invention. In discussing these evaluation strategies, I hope to help make this work legible to the institutional parties involved in the granting of doctorates, and specifically to those involved in the dissertation process itself.

Visual Literacy in the Digital Age: My Case

In August of 2005, I successfully defended a media-rich digital dissertation in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, after having justified its natively digital format to my dissertation committee.5 A few days later, I began a postdoctoral appointment at the Institute for Multimedia Literacy (IML) in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California (USC), where I remain, joining the faculty in 2007. In the intervening years, I have confronted the need for assessment and validation of digital work on a regular basis. Indeed, I joined the IML as it was transitioning from a grant-funded research unit into an academic division, the sixth in the USC School of Cinematic Arts. As faculty in a professional school, albeit a top-ranked one, I have frequently had to explain the merits of my own work as well as that of my students to the more traditional constituencies of the University.

I direct a multimedia honors program, an interdisciplinary undergraduate curriculum that culminates in a media-rich senior thesis project anchored in the student’s major. It is the first academic program created and housed at the IML and I began overseeing it just as the first cohort became seniors, ready to create their thesis projects in 2007. Despite curricular scaffolding and institutional support, guiding the construction of these projects was no easy task given the variety of disciplines represented, which ranged from Aerospace Engineering to Classics, from Biology to Theatre, Physics to Journalism. A good rubric was key and fortunately, we had one. Its parameters were established during my early days at the IML in collaboration with another postdoc, with input from faculty and staff. Originally, there were four areas with three sub-categories in each. After many years of trying to update and hone the rubric, in 2015, I worked with a particularly lively and intelligent cohort of seniors to revise it: we removed repetition and shifted emphasis slightly to reflect cultural and technological shifts that had occurred in the years since the document’s creation. There are now three broad areas—Conceptual Core, Research Component, Form + Content—with three features articulated within each. Although this rubric was originally created for undergraduate theses, it has been used widely for born-digital scholarship of all types.6

I discuss the parameters separately, giving a salient example of the actuation of each in a digital text. This conceptual and formal overview has been quite productive in the many production-based classes I teach as well as in the workshops I have done with faculty at several institutions in addition to my own. Obviously, it is more difficult to effect this overview on the printed page with only words and static images, but it is a useful exercise in translation that digital scholars will need to become practiced in, at least until these born-digital texts become more widespread and better understood: the more dynamic facets and the more subtle aspects of a digital text are difficult to describe and are better experienced, or at least witnessed during navigation.

I. CONCEPTUAL CORE

- The project’s controlling idea must be apparent and be productively aligned with one or more multimedia genres.

- The project must approach the subject matter in a creative or innovative manner.

- The project’s efficacy must be unencumbered by technical problems (which typically involves having a back-up plan).

Thesis driven prose is not the only, nor often the best option for digital texts so, in lieu of a thesis statement, a controlling idea is helpful to keep in mind, especially as one gets into the weeds of producing a large and complex text. A sense of a conceptual core keeps one anchored, especially when the myriad formal possibilities arise. Staying grounded in a controlling idea offers some constraints, while it also requires one to recognize and avoid formal elements which are rhetorically crude. These include functions like blink tags in HTML, gratuitous animation in PowerPoint, overuse of the zooming function in Prezi, and incoherent use of transitions (like the infamous star wipe) in video editing tools. Including these features may show some technical know-how, but they will not demonstrate rhetorical prowess. In other words, their presence would merely constitute ‘bells and whistles’, unless the point is to show the range of possibilities available for expression, in which case, the justification would be the pivotal aspect. Indeed, the ways in which the controlling idea is served by the container in which it is presented should be explicitly discussed in an FAQ, or instructions for access, or a ‘how to read this text’ section, in all digital texts. In fact, I occasionally still find myself explaining how to navigate digital work that was published years ago, much of which pushed back against the sort of spoon feeding (e.g., ‘click here!’) that characterized many of these webtexts early on.

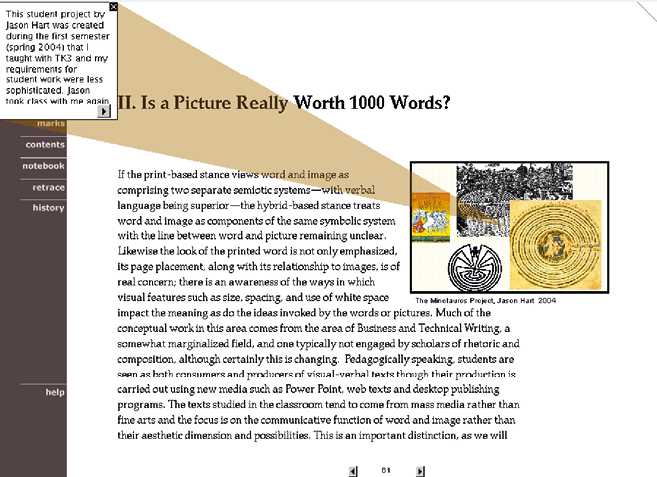

In addition to reckoning with the native functionality of a digital platform, one must also account for design issues such as color, font type and ‘page’ or screen layout. For instance, in a workshop on digital scholarship, a graduate student produced a hot pink screen that functioned as the landing page of her digital text. The screaming pink, which many in the workshop saw as ‘gaudy’ was, as the author explained, meant to express a feminist scream, a sort of primal anguish at having been left out of so much history. This was an excellent rationale and I use it here as a way of highlighting the fact that the ‘productive alignment’ referred to in this area does not necessarily mean imitating a genre, rather it means an awareness of one, whether one retains its conventions or subverts them. In the case of my dissertation, I sensed that a book-based metaphor was important to maintain in order to give readers a sense of its coherency with conventional formats, seeing the work as an extension of the standard, and this was key to my larger argument about an emergent language of images (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Screenshot of my dissertation showing its book-based metaphor, as well as an ‘annobeam’, a function native to the platform which helps readers stay anchored in the main text, while giving the additional information the way a footnote does.

The efficacy issue mentioned in this area is obvious since a controlling idea must be legible and this means the container must be reliable or an alternative must be offered. We might think of this as the equivalent of grammar and typos in a word-based text; those formal elements, which work against the controlling idea, take us out of the conceptual space that the text should carve out and draw us into. On a trivial level, this was a problem for me because there was no spell check function in the software I used. In the larger scheme of things, however, this can mean offering video documentation of a particular function, such as projection mapping, which is notoriously tricky to use in situ. While theses and dissertations should offer new knowledge, some of which comes by formal means, the message is utterly lost if it cannot be accessed. Indeed, access issues (whether technological or human in nature) contribute to the multiple versions of a dissertation that many doctoral students, including several authors in this collection, have felt the need to create as a safety net.

II. RESEARCH COMPONENT

- The project must display evidence of substantive research and thoughtful engagement with its subject matter.

- The project must use a variety of credible sources, which are cited appropriately.

- The project must effectively engage with the primary issue(s) of the subject area into which it is intervening.

Obviously, all aspects of this area are important since conducting research is what distinguishes a doctorate from other terminal degrees. Still, the ways that research is expressed in digital texts can sometimes remain implicit, making its explication useful and sometimes necessary. The reference to ‘substantive’ research is tough to quantify and yet a comparison with the number of sources in a traditional dissertation could provide a solid roadmap. The ‘credibility’ of the source should not be an issue at this stage.7 As for the ‘variety’ of sources, while this verbiage was meant to remind undergraduates of the need to use some books rather than web-based sources exclusively, these days I often have to remind graduate students to use extratextual media sources in addition to books. If a digital dissertation is a valid text (and not simply a word-based text put online), then the author must also take other digital sources seriously even as these sources remain difficult to cite in conventional terms.8 Indeed, it is important to cite not only word-based sources that are mainly conceptual in nature, but also media-rich ones that are invoked, or added directly to the digital dissertation. For instance, in my dissertation, I was pushing back against the convention of citing words but clearing images, often paying for this clearance but always asking permission, something I refused to do. I see this as a matter of free speech; if we fail to employ the language of images, then Hollywood effectively dictates who may speak and who is silenced. As such, using these media elements is crucial since the ‘excess’ of meaning encoded in non-textual media elements cannot be fully captured in words. Leaving them out, in my case, would have constituted incomplete scholarship.

This does not mean that anything goes with regard to the use of these media elements: we should exercise the same conventions as those we use for analogue media, and this means using only as much of the media element as is necessary to make a point, using the piece of media as an object of analysis rather than as decoration, and citing all sources. A discussion of sources and formats used is the sort of meta-level commentary that perhaps we ought to be having around all dissertations—if digital technologies allow the use of images and sound in addition to words, perhaps all dissertations should include a rationale for those registers that are deployed. In effect, this would find doctoral students justifying the use of only one register of meaning—the alphabetic. This is not to understate, in any way, the importance of verbal or ‘natural’ language in communication but it is to suggest that it is no longer the only game in town, as it were.

III. FORM + CONTENT

- The project’s structural or formal elements must serve the conceptual core.

- The project’s design decisions must be deliberate, controlled and defensible.

- The project must achieve significant goals that could not be realized on paper.

In many ways, this area’s focus on the relationship between form and content is the most straightforward one for a media-rich digital dissertation, since the format is the site of deviation and intervention. In terms of the reference to achieving goals that would be unrealized on paper, this was almost the default state of affairs in the late 1990s and early 2000s—simply putting a thesis in a form other than writing on a page made it innovative, and simply including the extra-textual registers of sound and moving image solidified this argument. And yet, this issue is far more complex than simply explaining the particular tool or platform used. There are very few platforms that allow the integration of media formats in a nuanced and sophisticated manner; nearly all digital authoring tools are either word-friendly or media-friendly but seldom both.

Creating tools is not really a viable option in the current state of late capitalism, at least in the US. While foundation money has been used to create tools like Sophie, an early version of which I used to create my dissertation, this sort of funding often dries up once the tool is created or the terms of the grant expire. Having worked at the forefront of tool creation for many years—in academia over the last two decades, as well as in the private sector from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s—I can attest to the fact that few accommodations are made for user testing and code debugging, never mind the increasingly short lifespan of any robust tool which requires nearly constant maintenance, all of which renders these tool creation projects problematic at best. The real issue, however, is the vast difference in scale of resources between such academic efforts and those of the tech giants today; stable software requires the multiple millions of dollars that tech companies are able to spend as well as the vast user base to whom they are able to feed updates. This means that awareness of the ideology around formal elements is key to any dissertation since nearly all scholarship is relayed through tools and platforms created with a free market, neoliberal ideology baked in.

Within the constraints of a particular platform however, there are also rhetorical approaches to its affordances, and the more explicit an author is about these choices, the better. An example of this comes by way of a webtext published in 2010 titled ‘Speaking with Students: Profiles in Digital Pedagogy,’ in Kairos. This particular webtext is quite germane to this discussion on many levels: it features overview videos of the students discussing their born-digital, media-rich thesis projects, as well as contextual information including the rubric under consideration here. The ‘pages’ of the webtext (which was created in the now obsolete program Adobe Flash), were carefully crafted to be semi-opaque, resulting in the presence of ‘ghost’ images—those of the other pages behind it (see Fig. 2). The journal’s editors were initially concerned about this bleed-through, which they read as a mistake, and asked us to fix it. But we explained that this was done with great intentionality as a visual indication of the sort of ‘thickness’ of the more spatially-oriented texts that we felt were just on the horizon, via more accessible 3D modeling programs, Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality gear, and consumer-grade depth cameras which can render 3D images from mobile phones. The journal editors were very supportive and simply asked us to add this information to the webtext, and we placed it at the end of the introduction.

Fig. 2 Screenshot of a webtext published in 2010 in Kairos (‘Speaking with Students’), in which the opacity has been carefully controlled to show the ghost of other pages in order to indicate the third dimension.

***

In retrospect, overseeing those inaugural thesis projects without a definitive template or archiving scheme was opportune, because it allowed experimentation with form when the stakes were not so high for either myself or the students. Indeed, when the first cohort of thesis students was graduating, I had met with university librarians in order to figure out how best to archive these projects. There was no viable plan and since this was undergraduate work, there was no mandate to ‘publish’ these in the University’s library system. As a solution, we moved toward project documentation, and since the IML had enough resources at that time to create the five-minute documentation videos published in the webtext, we were free to experiment and explore. The rubric allowed us to speak to projects across a range of topics and disciplines, crafting these videos with some uniformity.

I have directed these multimodal, interdisciplinary undergraduate theses for more than a decade and have served on numerous doctoral committees in multiple disciplines, with dissertations that are either fully word-based (aka traditional) or are hybrid in nature and include a media object accompanied by a monograph that lends theoretical grounding and interpretation. These hybrid dissertations are quite similar to the sort of arts-based research that has thrived in Europe for many years; in this scenario, the critique or explanation or interpretation is done outside of the object, and the object is sometimes included as supplementary material. In other words, the written portion could ostensibly stand on its own, given an adequate description of the object of analysis. In the humanities, however, one of the most traditional academic areas, this seems like a far less acceptable solution.

My focus is on this particular rubric because I have employed it for many years and can attest to both its theoretical and practical use. That said, there have been some really promising assessment schemas for digital scholarship formulated and gathered by prominent scholars such as Todd Presner, Cheryl Ball and Anke Finger. These efforts are extremely important in terms of moving digital scholarship from the margins to the center and removing the remaining stigma around its authorship as well as its value as a scholarly object, rather than mere curiosities that seem compelling or interesting to note, but not engage with any depth. But perhaps more vitally, they are absolutely essential to helping move the humanities away from the fetishization of the single-authored (word-based) monograph as the only and most valuable form of artistic and critical scholarly work.

A Final Note

In closing, I want to briefly mention that while rubrics are helpful in terms of assessing a finished product, and of course they should be kept in mind at the planning stages of a dissertation, they are not as helpful when guiding revisions of a work in progress. Giving notes on digital texts is not only a conceptual difficulty, but it is also a logistical one when we cannot simply pick up a pen and add notes or even type digital comments into a word processing program. The conceptual difficulties will surely become less pronounced once more senior scholars are conversant with these texts, but in a practical sense, how do we handle giving notes on the extra-textual registers—video, audio, linking structures and the like—without either spending an inordinate amount of time explaining notes in words, or by conducting the review in real time with the student author present? Having responded to hundreds of video essays over the last fifteen years, I have spent an exorbitant amount of effort making detailed notes, marking time codes for each, and then trying to describe the sorts of complex media revisions I am suggesting using words alone, so I have a vested interest in finding better methods.9

The raw truth is that as digital scholarship becomes more sophisticated and more ubiquitous, so too will its editing and revision processes. The extremely time-consuming act of commenting on texts that work across the registers of word, images, sound and interactivity will certainly not be lessened, and will likely be far more involved. As a starting place for thinking about a robust revision process that does not prove overly onerous for either party, we might look to peer-reviewed digital journals and their submission process. I have served as a reviewer for a number of digital journals over the years, but I have experienced both sides of the review process with work published in Kairos: Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy. Conceptually, the review notes I have been given on digital work from Kairos reviewers have been extremely influential for my own peer reviews, as well as for my notes on students’ digital work. Logistically, I find promise in a plug-in developed for the Journal for Artistic Research (JAR) which allows a reviewer to comment directly into the text. This plugin is accompanied by an excellent review form that resists a stable set of criteria but, like Kairos, asks instead about the text on its own terms. Such questions include: Which aspects of the submission are of interest/relevant and why? and Does the submission live up to its potential? These questions allow for inventive texts while also recognizing they can almost always be improved upon. But perhaps more importantly, by linking student work to professional work we remember the ecosystem of institutions of higher education and remind ourselves of the value of our work with students.

Bibliography

Ball, Cheryl E., ‘Assessing Scholarly Multimedia: A Rhetorical Genre Studies Approach’, Technical Communication Quarterly, 21.1 (2012), 61–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2012.626390

Editorial Board and the Review Process, Kairos: Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/board.html

Finger, Anke, Digital Scholarship Evaluation, https://dsevaluation.com/

Journal of Artistic Research, ‘Peer Review Form’ (2019), https://jar-online.net/sites/default/files/2019-12/JAR_Peer-Review_Form%202019.pdf

Virginia Kuhn, ‘The Components of Scholarly Multimedia’, Kairos: Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 12.3 (2008), https://www.academia.edu/859541/The_Components_of_Scholarly_Multimedia

Kuhn, Virginia, et al., ‘Speaking with Students: Profiles in Digital Pedagogy’, Kairos: Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 14.2 (2010), https://cinema.usc.edu/images/iml/SpeakingWithStudents_Webtext1.pdf

Presner, Todd, ‘How to Evaluate Digital Scholarship’, Digital Humanities Quarterly, 1.4 (2012), http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-4/how-to-evaluate-digital-scholarship-by-todd-presner/

1 See https://www.mla.org/About-Us/Governance/Committees/Committee-Listings/Professional-Issues/Committee-on-Information-Technology/Guidelines-for-Evaluating-Work-in-Digital-Humanities-and-Digital-Media

2 Archiving dissertations in their native format is preferable but technologically problematic given platform obsolescence and the use of emulators that can run old software is cost prohibitive. See Chapter 4 of this collection for an overview of Gossett and Potts’ efforts in this area. As it stands, unless students commit to hosting their own domains and keeping their dissertation updated, the work will become inaccessible. ProQuest, the main archive for dissertations in the United States, after blocking my own dissertation as well as a few others I know of, is now endeavoring to archive media-rich work in a compatible environment. I remain hopeful but skeptical. For more on archival projects, again please see Chapter 4 of this book.

3 My dissertation was created in TK3, a software program written in Smalltalk, a coding language that is no longer widely used. See below for a discussion of this choice.

4 See Virginia Kuhn, ‘The Components of Scholarly Multimedia’, Kairos: Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 12.3 (2008), https://www.academia.edu/859541/The_Components_of_Scholarly_Multimedia and Virginia Kuhn et al., ‘Speaking with Students: Profiles in Digital Pedagogy’, Kairos: Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 14.2 (2010), https://cinema.usc.edu/images/iml/SpeakingWithStudents_Webtext1.pdf

5 My committee was supportive after some initial skepticism and I intentionally chose a Chair who was the least tech savvy, figuring that if I could convince her, I could convince anyone. My committee included: Alice Gillam as Chair, Gregory Jay, Vicki Callahan, Charles Schuster and Victor Vitanza. I also had invaluable support from Bob Stein and his staff at the Institute for the Future of the Book.

6 Perhaps the best example of this rubric’s adoption can be found in Cheryl E. Ball, ‘Assessing Scholarly Multimedia: A Rhetorical Genre Studies Approach’, Technical Communication Quarterly, 21.1 (2012), 61–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2012.626390

7 Indeed, in my doctoral program, once students pass their preliminary or qualifying exams and become ABD, they receive a letter from the University stating that they are now considered to be a researcher.

8 Typically, these dynamic texts are difficult to reference not only because they move but, more importantly, since it is difficult to direct a reader to a particular ‘page’ or screen. For instance, in Adobe Flash, once the standard for dynamic webtexts, there is only a single URL for the entire text. With HTML5 this is less problematic and on platforms such as Scalar, for instance, most of the Flash elements have been rewritten in HTML5, allowing multiple URLs.

9 I must give credit to Cheryl Ball, and her feedback on the first video-heavy collection I published in Kairos in 2008. Working with the fifteen pages of notes which she assembled to help in my revision of each video in the collection taught me how to give effective notes myself. Although it took me years of practice to become really good at giving these notes, it would have been impossible without that early model.