6. Master and Manxman: Reciprocal Plagiarism in Tolstoy and Hall Caine1

© 2021 Muireann Maguire, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0241.06

In the winter of 1906, a reception was held in a Westminster flat for Mr and Mrs Maksim Gor’kii on their return from an exhausting and scandalous American tour (the title of “Mrs” was tactfully bestowed on Gor’kii’s mistress Maria Andreeva, whose presence had triggered the American scandal). Gor’kii had personally requested each guest; collectively, they represented a ‘galaxy of genius’, according to journalist Robert Ross.2 They included H. G. Wells, Bernard Shaw, Henry James, Thomas Hardy, the historical novelist Maurice Hewlett, the radical journalist Henry Nevinson, and A. W. Clarke, whose Jaspar Tristram (1899) was a fictionalized memoir of English boarding-school life. Ross himself was present as the editor of his friend Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis (1905), which would appear in Russian translation in 1909. Every guest was promised fifteen minutes’ audience with Gor’kii, described as ‘an astonishing shaggy figure in a blue sweater, who seemed a cross between a penwiper and an Eskimo’;3 however, as Bernard Shaw monopolized the great man for a full two hours, it was not until four in the morning that Gor’kii and Andreeva ultimately departed. As their host walked Gor’kii to his cab, the other guests lingered anxiously to hear his verdict on the evening.

We waited like boys waiting to hear the result of a scholarship examination; it was an awe-inspiring moment. Each man felt that no common evening had closed. ‘Gorky wants me to tell you that he has spent an evening he will never forget; that to-night he met almost everyone he admired in England; everyone he wanted to meet.’ There was a murmur of gratuitous deprecation. ‘There are only two other writers he wanted to see,’ our host went on. The coats and mufflers were adjusted; there was an awkward pause. I knew what was coming; but we pressed him to be more explicit. ‘The only others Gorky hoped to have seen here… were Hall Caine and Marie Corelli!!’4

An alternative version of this party describes Gor’kii ‘search[ing] the room in vain for a looked-for face. At last, he could keep these feelings to himself no longer. “But the Great Man,” he asked, “is he not here? Is he not coming?” … He could see no sign of Hall Caine.’5

Both these writers, whom Gor’kii was so disappointed to miss, have now disappeared into a possibly deserved obscurity. Although Caine and Corelli were best-selling, influential authors in their late-Victorian heyday, we remember them now, if at all, as a footnote to others’ work. Corelli is the prototype for the title character in her friend E. F. Benson’s Lucia novels (1920–1939); Caine, as ‘my dear friend Hommy-Beg’, is the dedicatee of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).6 Caine shares with Corelli an additional, if rather doubtful, honour: both were regarded with contempt by Lev Tolstoy. Tolstoy often excoriated popular icons (famously, Shakespeare) and bestowed praise on obscure or unexpected writers (regular reading of the Tauchnitz collection of British novels introduced him to the romances of Mrs Henry Wood and Mary Elizabeth Braddon).7 He did admire Dickens, Trollope, and George Eliot, but he could be caustic about other popular authors.8

Ironically, Tolstoy’s novels often had more in common with the kind of romantic melodrama which he deplored than he chose to acknowledge. The case of Hall Caine (1853–1931) is particularly illuminating. Not only was Caine’s immense (if transient) popularity as a fiction writer equal to Tolstoy’s, the British novelist strenuously aspired throughout his career to achieve professional and reputational parity with Tolstoy, disregarding the latter’s disdain. By exploring the narrative themes and humanitarian concerns shared by Caine and Tolstoy, this essay will reveal considerable common ground between the novel of ideas and the novel of sensation at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The great Russian author’s scorn must have stung Caine, who had spent years establishing himself in British circles as an authority on Russia (particularly on Russian Jews) while intermittently courting Tolstoy’s favour. Journalists frequently compared Caine to famous European writers: as early as 1890, following the success of his early novels, the popular weekly Sunday Words ran a cover feature on ‘Hall Caine, The English Victor Hugo’.9 Several of Caine’s books, including an edition of his collected works in 1915, were translated into Russian; The Eternal City (1901) was even translated (as Vechnyi gorod, in 1902) by Konstantin Konstantinovich Tolstoy, a doctor and writer, and a distant relation of Lev Nikolaevich.

It was galling for a famous author, hailed by some reviewers as ‘the English Tolstoy’ and fond of emphasizing his own moral and imaginative sympathy with the Russian author, to be unable to provoke more than the faintest praise from his idol.10 Caine, or his publishers, swiftly recycled any appearance of encouragement from Tolstoy as a selling point for his own novels. One editor’s introduction to Caine’s The Bondman (1890) assured readers that ‘Leo Tolstoy read the book with “deep interest”’.11 The original phrase was ‘great interest’, and this formulaic politeness was relayed by Tolstoy’s daughter Tatiana in a note acknowledging receipt of a gift copy of The Bondman.12 Despite the flimsiness of this connection, Hall Caine was not above exploiting it again in a preface to a later novel, referring to information received from Tolstoy ‘through his daughter’.13 The jacket of the 1927 reprint of one of Caine’s bestsellers avers that ‘The Christian provoked world-wide discussion, in which Tolstoy took part’14—which was, as we shall see, a remarkably neutral description of Tolstoy’s actual contribution. More subtle tokens of respect can be found in Caine’s epigraph to The Bondman, ‘Vengeance is mine—I will repay’, which is of course also the epigraph to Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1878; first English translation, 1886). Even the title of Caine’s last major novel, The Master of Man: The Story of a Sin (1921), seems to echo the various English translations of Tolstoy’s frequently anthologized short story, ‘Master and Man’ (‘Khoziain i rabotnik’, 1895).15

Thanks to Pierre Bayard’s concept of anticipatory plagiarism, we can now regard Caine’s unrequited admiration for Tolstoy from a new and illuminating perspective. Bayard cites multiple cases where chronologically precedent writers have borrowed, or plagiarized, specific contraintes (sets of literary rules) from their posterity. As an example, he cites Voltaire’s novella Zadig (1749), which includes an episode of deductive reasoning by the title character which could well have been pilfered from Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series, despite preceding the deerstalker-wearing detective by almost one hundred and forty years.16 It is extremely doubtful that Conan Doyle plagiarized Zadig in the traditional direction, since as Bayard admits, Voltaire’s novella in no other way resembles a detective story, nor does its titular hero indulge in other flights of deduction.17 The existence of two markedly similar passages in otherwise completely unrelated and temporally distant texts is sheer coincidence—or, in Bayardian terms, a vindication of non-chronological literary cross-pollination.

In other cases of anticipatory plagiarism, however, it is impossible to deny a relationship between the texts: the later text has been influenced by, and has even borrowed from, the earlier one, compounding as if condoning the earlier text’s theft.18 Bayard gives the examples of the twelfth-century legend of Tristan and Iseult and nineteenth-century Romanticism, which he claims share the contrainte of depicting romantic passion as self-destructive (even when it is reciprocated). In other words, while the core theft (the contrainte of self-destructive love) was perpetrated by medieval troubadours against the French Romantic poets and novelists, the latter group subsequently read and admired the medieval lyric poems and thus (however paradoxically) borrowed back their own ideas, which duly informed the Romantic movement. Bayard calls this phenomenon reciprocal plagiarism: an instance ‘where two authors, separated by time, inspire each other’.19 It is my main contention in this essay that Caine and Tolstoy formed just such a pair of chronologically separate, yet mutually influential, reciprocal plagiarists. Their literary careers overlap between Caine’s debut as a novelist in 1885 and Tolstoy’s death in 1910; Caine was already popular in the late 1880s, when the first English translations of Tolstoy’s fiction were appearing. Caine was thus the first of the pair to establish an anglophone reputation, and so, to coin an oxymoron, the original plagiarist.

I argue that Caine’s admiration for Tolstoy was so extreme that he plagiarized the latter’s novel Resurrection (Voskresenie, 1899) five years before it was actually published; that Tolstoy returned the favour by plagiarizing, in Resurrection, Caine’s 1921 novel The Master of Man; and that Caine continued to plagiarize Tolstoy in the standard chronological direction until the end of his career. Moreover, Caine plagiarized in advance not only the Russian writer’s literary themes, but also Tolstoy’s internationally praised statements of protest against the persecution of religious minorities through his own publicity networks. I begin this essay by reviewing Hall Caine’s reputation and literary career, including those novels which plagiarize Tolstoy either proleptically or analeptically; secondly, I use new archival research to study Caine’s fascination with Russia and Russian Jews, which peaked with his journey to Russia in 1892; and in the last section, I look at the history of Caine’s relations with Tolstoy. In conclusion, I suggest that Caine’s facility in plagiarizing Tolstoy’s last major novel suggests that these two authors had more in common—creatively and ideologically—than the living Lev Tolstoy would ever have conceded.

Caine, The Manxman, and Mutual Plagiarism

Fig. 1. Hall Caine, Self-portrait (caricature) (1892), MS 09542, from the papers of Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (1853–1931), Manx National Heritage Museum, Douglas, Isle of Man. Used with permission of the Manx National Heritage Museum.

Thomas Henry Hall Caine (known as Tom to his intimates), although born and educated in Liverpool, came of Manx stock on his father’s side; in 1870, aged seventeen, after a brief apprenticeship to an architect, he moved to the Isle of Man to assist his uncle as a village schoolteacher. Two years later, influenced by Ruskin’s political and aesthetic writings, he returned to Liverpool where he became known as a journalist. A positive impression upon the ailing Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who later invited him to London as his assistant, secured Caine’s entrée into the British literary elite. In 1885 he published his first novel, The Shadow of a Crime, a historical melodrama set in rural Cumberland. The Deemster (1887), a historical novel set on the Isle of Man, and The Bondman (1890), a melodrama set between Man and Iceland, established Caine’s archetypal plot: an intrigue affecting humble individuals in remote, primitive communities, portrayed realistically in the manner of Pierre Loti, Knut Hamsun and Gor’kii himself. Caine owed his rapid popularity to the complex love triangles, extramarital sex, and melodramatic cliff-hangers in his fiction. Yet his authorial intentions were invariably modern and humanitarian. He carefully researched the exotic locations of works like The Bondman, The Scapegoat (1891; set in Morocco), and The White Prophet (1909; set in Egypt), while his ambitious treatment of Vatican politics in The Eternal City (1901) and of urban poverty and prostitution in his blockbuster romance The Christian (1897) were openly morally didactic (even if their appeal derived from the descriptions of immorality which they condemned).

Modern readers may marvel that, at a reception including Wells, James, Shaw and Hardy, Gor’kii was chagrined by the absence of two merely popular novelists. But this view underestimates Hall Caine’s colossal fame on both sides of the Atlantic from around 1890, until at least the start of the First World War. His greatest triumph, The Christian, appeared serially in The Windsor Magazine; when published in book form, it sold 150,000 copies within six months, later becoming the first British novel to sell a print run greater than one million.20 Like most of Caine’s fiction it was successfully adapted for the theatre and toured internationally. It was also widely translated (the first Russian version, Khristianin, by Aleksandra Lindegren, appeared in 1901). Caine was talented and prolific; he was, as we shall see, genuinely troubled by humanitarian questions, principally child poverty, the persecution of Jews, and the fate of unmarried mothers; and he was a consummate self-publicist and networker. The combination was unbeatable, though not unmockable. Oscar Wilde said of him: ‘Mr. Hall Caine, it is true, aims at the grandiose, but then he writes at the top of his voice. He is so loud that one cannot hear what he says’.21 The relentlessly noble profile which both Caine and Tolstoy projected to their public was easy to lampoon: since Caine owed his success to the facility rather than the originality of his prose, he made a softer target than Tolstoy for both journalists and unsympathetic peers.

The literary contrainte which Caine plagiarized by anticipation from Tolstoy—and which he would later borrow back—was a version of the theme of the ingenuous young woman abandoned by her inconstant lover. This contrainte differentiates Tolstoy’s and Caine’s stories from myriad similar scenarios in contemporary literature (to name just two examples, Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) and Chekhov’s The Seagull (Chaika, 1896)) by stipulating two specific, obligatory narrative steps: (a) the man sits in judgement over his beloved in a court of law, and (b) he subsequently decides to rescue her and redeem himself. Both Caine and Tolstoy’s narratives unite legal with moral awakening: after the unexpected courtroom encounter with his former mistress, each male protagonist realizes that even if society is prepared to ignore his previous behaviour, he must undertake public confession, renunciation of wealth and position, and restitution (by marrying or otherwise supporting the wronged woman). To study this contrainte and to fully expose the multidirectional plagiarism at work here, I will begin by summarizing the best-known narrative example—Tolstoy’s 1899 Resurrection—before contrasting the plots of two novels by Caine which respectively anticipate and recapitulate it, The Manxman (1894) and The Master of Man (1921).

As Tolstoy’s final novel, Resurrection was perhaps his fullest condemnation of the far-reaching consequences of casual sex. It was based on a real-life melodrama Tolstoy learned of in 1887 from his friend, the reform-minded judge Anatolii Federovich Koni, and which probably took place in the early 1870s. The individuals concerned were a wealthy St Petersburg nobleman, later vice-governor of a Siberian province; and a young Finnish peasant girl, Rozaliia, who became a prostitute after their affair. She was arraigned for theft, and thus the nobleman saw her again in a courtroom. Events resembled the first part of Resurrection closely, but in real life, Rozaliia’s death from typhus in prison terminated their relationship.22 This was the story that Tolstoy fictionalized. Rozaliia became Katiusha (Katerina) Maslova, an illegitimate peasant raised ‘half servant, half young lady’ as the ward of two elderly aunts on a small country estate.23 At the age of seventeen, she is seduced by their nephew, Prince Dmitrii Nekhliudov, who insensitively pays her off with a hundred roubles. Maslova, although abandoned and pregnant, does not acknowledge the hopelessness of her situation until a chance sighting of Nekhliudov departing on a train convinces her of his indifference.

Losing faith ‘in God and in goodness’,24 Maslova gives her newborn to a nurse who sends it to a foundlings’ home; after an unsuccessful spell as a servant, she becomes a prostitute in the capital, St Petersburg. There, eight years after their fateful affair, Nekhliudov recognizes Maslova among the defendants on trial for robbery and conspiracy to murder. As a juror, Nekhliudov has no difficulty in steering the sympathetic jury towards a verdict of ‘“Guilty, but without intent”’, which carries a mild sentence; unfortunately, in their ignorance and confusion, they fail to use the necessary formula ‘“Guilty, but without intent to cause death”’.25 Because of this technical error, Maslova is condemned to four years’ exile in Siberia. Horrified by the baleful effect he has twice had on this woman—first by ruining her, and secondly by unintentionally exacerbating her sentence—Nekhliudov alters his entire way of life. He strives to get her sentence annulled (an appeal to the Senate and a petition to the Tsar both fail); he breaks off an advantageous engagement as well as an affair with a married woman, in order to become engaged to Maslova; he deeds his lands to the peasants who work them; finally, he accompanies Maslova to Siberia, as her fiancé. The theme of private awakening and public confession recurs throughout Resurrection.

I have lived a double life. Beneath the life that you have seen there has been another—God only knows how full of wrongdoing and disgrace and shame. […] Let it be enough that my career has been built on falsehood and robbery, that I have deceived the woman who loved me with her heart of hearts […]. The moment came when I had to sit in judgement on my own sin, the moment when she who had lost her honour in trusting to mine stood in the dock before me. I, who had been the first cause of her misfortune, stood on the bench as her judge. She is now in prison and I am here. The same law which has punished her failing with infamy has advanced me to power. […] When I asked myself what there was left for me to do, I could see but one thing. It was impossible to go on administering justice, being myself unjust […]. I could not surrender myself to any earthly court, because I was guilty of no crime against earthly law. The law cannot take a man into the court of his own conscience. He must take himself there.26

The citation above, however, is not from Resurrection. It comes from Caine’s The Manxman, published in 1894 before Resurrection existed even in draft form; it was alluded to in Tolstoy’s notes only as ‘the Koni story’ (‘Konevskii rasskaz’).27 From the records of Tolstoy’s private library at Iasnaia Poliana, we know that he possessed copies of The Bondman, The Christian and The Eternal City, at least one of which was a gift from the author; there is no evidence that Tolstoy ever read The Manxman. Yet it is hard to deny correspondences between the passage cited above and Nekhliudov’s private reflections after hearing Maslova’s sentence:

[Nekhliudov had undergone …] defilement so complete that he despaired of the possibility of getting cleansed. […] But the free spiritual being, which alone is true, alone powerful, alone eternal, had already awakened in Nekhludoff, and he could not but believe it. Enormous though the distance was between what he wished to be and what he was, nothing appeared insurmountable to the newly-awakened spiritual being. ‘At any cost I will break this lie which binds me and confess everything, and will tell everybody the truth, and act the truth,’ he said resolutely, aloud. […] ‘I shall dispose of [my] inheritance in such a way as to acknowledge the truth. I shall tell her, Katusha, that I am a scoundrel and have sinned towards her, and will do all I can to ease her lot. Yes, I will see her, and will ask her to forgive me. Yes, I will beg her pardon, as children do.’ ... He stopped—‘will marry her if necessary.’ He stopped again, folded his hands in front of his breast as he used to do when a little child, lifted his eyes, and said, addressing some one: ‘Lord, help me, teach me, come enter within me and purify me of all this abomination.’ He prayed, asking God to help him, to enter into him and cleanse him; and what he was praying for had happened already: the God within him had awakened his consciousness.28

For both Caine and Tolstoy, these fictional travails—and their moral underpinnings—were greeted by controversy. In 1894, the year Heinemann published Caine’s The Manxman, they also brought out Tolstoy’s influential treatise The Kingdom of God Is Within You (Tsarstvo Bozhie vnutri vas, 1894) in Constance Garnett’s English translation. Tolstoy insisted in this work that every human being has ‘rational conscience’ as his ‘sole certain guide’ to moral justice. He stirred public outrage by implying that reasoning Christians can choose to ignore the laws of Church and state.29 These arguments, followed by Resurrection’s cruel critique of Orthodox clergy, eventually led to Tolstoy’s 1901 excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church.30 Caine would have his own brush with religious controversy twenty years later thanks to his novel The Woman Thou Gavest Me (1913), when the unhappily married heroine yields her virginity to her childhood sweetheart rather than her husband. But, as a stringent Catholic, she refuses to remarry even after her husband divorces her, since while ‘[t]he Church may [give] a wrong interpretation’ of sexual freedom, the marriage vow itself remains ‘divine and irrevocable’.31 This exercise in Christian self-determination almost ruined both Heinemann’s finances and Caine’s reputation, when the circulating libraries of the United Kingdom decided to ban the book after a print run of five thousand copies had already been produced. Fortunately, Caine’s influential contacts prevailed over trade scruples, and the ban was relaxed.32 In the year 1894, however, Tolstoy appeared to have plagiarized the appeal for independent ethical thinking made in The Kingdom of God from The Manxman, where Caine’s hero realizes ‘[t]he law cannot take a man into the court of his own conscience. He must take himself there.’33 Similarly, the sense of moral and physical suffocation experienced by Caine’s characters immediately prior to their spiritual awakening seems to prefigure Tolstoy’s claustrophobic evocation of an immature conscience:

Every man of the present day with the Christian principles assimilated involuntarily in his conscience, finds himself in precisely the position of a man asleep, who dreams that he is obliged to do something which even in his dream he knows he ought not to do. He knows this in the depths of his conscience, and all the same he seems unable to change his position; he cannot stop and cease doing what he ought not to do. And just as in a dream, his position becoming more and more painful, at last reaches such a pitch of intensity that he begins sometimes to doubt the reality of what is passing and makes a moral effort to shake off the nightmare which is oppressing him.

This is just the condition of the average man of our Christian society. He feels that all that he does himself and that is done around him is something absurd, hideous, impossible, and opposed to his conscience; he feels that his position is becoming more and more unendurable and reaching a crisis of intensity.34

The plot of The Manxman establishes just such a crisis of intensity. Like most Caine novels, it involves a love triangle between childhood friends—Philip Christian, grandson of the Deemster (or chief Judge) of the Isle of Man; his illegitimate cousin, Pete Quilliam; and the local miller’s daughter, Kate Cregeen. Pete and Kate become engaged; but while Pete is seeking his fortune abroad, Philip and Kate fall in love and sleep together. Philip breaks off with Kate, ostensibly from belated loyalty to Pete but primarily because he knows that Kate’s inferior education and social class would stymie his legal career. When Pete returns as a wealthy man, he persuades Kate to marry him; but shortly after the wedding, Kate realizes she is pregnant with Philip’s child. No public scandal materializes, since Pete, who is apparently deficient in either arithmetic or biology, happily accepts the infant as his own. Kate, unable to bear the hypocrisy of living with a husband she cannot love, deserts her family. Philip is appointed Deemster. Kate, now suicidal, is arrested for self-harm. Her unexpected appearance in the Deemster’s court triggers Philip’s repentance and spiritual awakening. He renounces both the office of Deemster and the newly offered position of Governor of the entire island; he publicly confesses his part in Kate’s disgrace; and he embarks on a new life with her. The all-condoning Pete divorces Kate and sails conveniently away.

Vivid characterization and local colour redeem The Manxman’s improbably fraught plot. From this outline, we can see that Caine plagiarized from Resurrection the following tropes: an unequal, short-lived sexual liaison; a fortuitous pregnancy; the heroine’s arrest and court appearance; the hero’s repentance and confession. In 1921, having already outlived his heyday, Caine plagiarized Resurrection—or perhaps his own Manxman—all over again in his new novel, The Master of Man. In his ‘Author’s Note’, he thanks two sources for inspiring Chapter Forty-four of the novel (in which the hero commits increasingly illegal manoeuvres to restore justice). The first is his old friend, the Galician Jewish author Karl Emil Franzos (1848–1904), whose novel The Chief Justice (Der Präsident, 1884) was another Heinemann acquisition admired by Caine for its realistic treatment of the lives of Russian Jews.35 As for the second source, Caine writes, ‘I wish to say that Tolstoy told me, through his daughter, that similar incidents occurring in Russia (although he altered them materially) had suggested the theme of his great novel, “Resurrection”’.36 While some borrowings are explicit (the use of ‘Resurrection’ as the title for the final section and one of the final chapters of Master of Man), others are more subtle. Caine’s narrative features a love rectangle rather than a triangle, set once again on the Isle of Man around the turn of the nineteenth century. The Deemster’s son Victor Stowell, and Fenella Stanley, the Governor’s daughter, appear destined to marry. He is a rising lawyer; she is a passionate and expensively educated Christian feminist. Inspired by Fenella, Victor persuades juries to acquit abused wives who have murdered their husbands in self-defence. Yet Victor commits two deeply dishonourable acts: he sleeps with a lower-class local girl, Bessie Collister; and he allows his best friend Alick Gell to become engaged to her, without revealing his own prior liaison.

Naturally, as a good Edwardian heroine, Bessie becomes pregnant after sleeping with Victor once. Having concealed her condition, she accidentally suffocates her newborn. Police apprehend her trying to conceal its body. Meanwhile, Victor has been appointed Deemster; Bessie’s trial for infant murder takes place in his court. From this point onwards, The Master of Man retraces the plot of The Manxman, now complicated by Fenella’s fervent espousal of Bessie’s cause. Victor, caught between public disgrace and the loss of Fenella if he confesses his own involvement, and moral ruin if he allows Bessie to hang, tries to recuse himself from the latter’s trial. When Bessie is sentenced to death, he abuses his authority as Deemster to free her from prison, sending her to safety under the protection of Alick Gell. Eventually, Victor confesses and is forgiven by both Fenella and Alick; the former Deemster is sentenced to two years in a Manx gaol for abusing his office; and Fenella, in a neat reversal of Nekhliudov’s vow to follow Maslova into Siberian exile, becomes a prison warder in order to be near him. They even get married in prison (in Tolstoy’s Resurrection, Nekhliudov and Maslova never marry, because Maslova develops an affection for another convict). It falls to Fenella to dramatize Victor’s spiritual resurrection in the final paragraph of The Master of Man:

But well she knew that the victory had been won, that the resurrection of his soul had already begun, that he would rise again on that same soil on which he had so sadly fallen, that shining like a star before his brightening eyes was the vision of a far greater and nobler life than the one that lay in ruins behind him, and that she, she herself, would be always by his side to ‘ring the morning bell for him’.37

The final lines of Resurrection read like a more concise and equivocal description of a similar mental state:

And a perfectly new life dawned that night for Nekhludoff, not because he had entered into new conditions of life, but because everything he did after that night had a new and quite different significance. How this new period of his life will end, time alone will prove.38

Who is copying from whom? Was Caine’s Manxman plagiarizing Tolstoy’s Resurrection in advance, or did his The Master of Man retroactively steal from Tolstoy’s novel? Or was Tolstoy copying The Manxman while effecting an anterior plagiarism from The Master of Man? If we accept Resurrection as an intermediate text simultaneously provoking and pillaging the novels Caine wrote at opposite ends of his career, our next question must be the motivation behind Caine’s and Tolstoy’s shared and enduring fascination with this particular contrainte of illicit passion, legal consequence, and repentance.

Unlike Tolstoy, who carefully documented his premarital liaisons with serfs, prostitutes and women of his own class,39 Caine had no reason to feel personally guilty for the exploitation of women or the neglect of illegitimate offspring. While his own wife, Mary Chandler, was under-age at the time of their liaison (she was thirteen when they began living together in 1882), Caine married her in 1886. Their first son, Ralph, was born technically illegitimate, but his father later legally adopted him. Numerous letters home attest that Caine was a loving husband and an attentive father to both his sons (Derwent was born in 1891). Yet neither writer allowed domestic content to blind them to the adverse social consequences of sexual exploitation and social hypocrisy upon the lives of women and children. We know that Tolstoy contemplated the anecdote that would become Resurrection for more than a decade preceding the book’s 1899 publication; during this period, he wrote other influential and highly melodramatic fictions about the pernicious effects of socially condoned fornication: The Kreutzer Sonata (Kreitserova sonata, 1889); The Devil (D’iavol, 1889); and Father Sergei (Otets Sergei, completed in 1898). In 1888, Tolstoy told W. T. Stead that he was planning The Kreutzer Sonata as ‘a romance exposing the conventional illusion of romantic love’.40 In an 1890 interview, Caine claimed:

I agree very largely with Tolstoi in his ‘Kreutzer Sonata’, and hold that the love passion, both on its spiritual and its sensual sides, is exalted by modern writers to such undue importance that it seems to consume the best energies of man. If we believe the novels and plays of the time there is next to nothing in life but love, and next to nothing in love but lust. Love is a part, not the whole of life. But it so dominates literature now that if it was forbidden to dramatists and novelists to touch upon the illicit side of love early all the theatres would be closed, and not a hundredth part of the novels would be written.41

In other words, while rejecting lust as a negative force, both writers were resigned (Caine openly so) to writing about it, if only to draw attention to its deleterious moral effects.

Presumably this was how Caine justified his decision to revisit, between 1885 and 1897, his preferred plotline of illicit lust. The motif of two brothers or close friends competing for one woman appears in his very first novel, The Shadow of a Crime (1885); a year later, in A Son of Hagar (1886), three brothers are vying for the same inheritance and the same heiress, with the added sub-plot of one brother’s cast-off peasant mistress and their illegitimate child. In The Christian, the two main characters—the passionate Christian socialist preacher, John Storm, and the aspiring actress, Glory Quayle—lead turbulent but ultimately moral lives, despite exchanging the peaceful Isle of Man for London’s fleshpots. But one of Glory’s aristocratic admirers has an illegitimate child, whose mother commits suicide at her faithless lover’s wedding to an heiress. Unlike Resurrection, there is no evidence that these books were inspired by real-life events. Archetypal fallen women, short-lived babies, unnatural mothers, and irresponsible fathers were recycled and recombined in almost all of Caine’s works; Tolstoy, by contrast, was unlikely to blatantly re-use a plot motif or duplicate a character, even if some of his characters experience similar traumas and exigencies.42

After prostitution and unmarried pregnancy, a third and less well-known consequence of sexual inequality which both writers denounced was the practice of baby farming. In baby farms, usually private homes, unscrupulous nurses accepted payment from unwed mothers to feed and house their infants. In an impassioned 1890 essay on the notorious Skublinskaia baby farm in Warsaw, where over a hundred infants were thought to have died of malnutrition and neglect, Tolstoy rejected the moral hypocrisy of denouncing the matron Skublinskaia and her ilk as ‘beasts’ (‘zveri’), when the Russian government practised comparable acts of murder and imprisonment against its own population.43 Tolstoy’s initial, outspoken horror at the atrocity of murdered and abused children shades into an early version of the call for empathy and rational moral autonomy which he would reassert in The Kingdom of God Is Within You.

Baby farms also feature in Caine’s novels The Christian and The Woman Thou Gavest Me; in the first of these, Glory Quayle and John Storm are instrumental in exposing and closing down one such organization.44 In 1909, Caine wrote to the Lord Mayor of London offering financial support to a charitable organization for ‘fallen women’, the Sisterhood of the West London Mission. Caine praised the Sisterhood’s policy of extending charity and shelter without requiring the women to leave the streets, adding,

The great problem of the fallen woman is not to be easily solved, but it is the plain and urgent duty of Society to lessen as far as lies within its power the perils under which so many of the frailest of our fellow creatures spend their lives.45

Clearly, both Caine and Tolstoy blamed society, rather than individual women, for the degraded and occasionally criminal lives led by unmarried mothers and by prostitutes; and they both used their fiction, their media presence, and their status as household names to bring questions of gender injustice to the forefront of public debate.

Caine, Russia, Jews and Doukhobors

The second contrainte shared by Caine and Tolstoy is the mobilization of literary capital (and, to differing degrees, the financial capital gained from one’s literary production) to assist a persecuted religious minority. This section will show how Caine’s widely publicized support for persecuted Russian Jews, pursued on the back of a new novel with a Jewish protagonist, plagiarized elements from Tolstoy’s world-famous advocacy for Russia’s threatened Doukhobors. In 1891, Caine published The Scapegoat, whose Jewish hero successively overcomes the negative stereotypes associated with his co-religionists—greed, pride, enmity, persecution, poverty—to attain a happy ending. As Anne Connor suggests, The Scapegoat was Caine’s response to a question he would pose rhetorically in a later speech: how literature could be used to defeat anti-Jewish prejudice in the UK and Europe.46 In May 1892, Caine’s lecture ‘The Jew in Literature’ (given at a dinner hosted by a Jewish club, the Maccabees) decried Jewish stereotypes in fiction, praised Jews as ‘notoriously assimilable and clubbable’, and, while drawing attention to ‘dark and distressful’ developments in some parts of Europe, urged Jews to fight back against cultural misconceptions and political mistreatment by writing more fiction. He concluded:

The Jew is now a great figure in literature, both as creator and subject of it. No base tyranny can be perpetrated on the Jews in any nation with the old impunity. Let the lowest of nations turn the Jews out of their country, and the pen in effect turns that nation out of Europe and out of the world of civilized man.47

This and similar speeches, combined with sales of The Scapegoat, gained Caine the reputation of a sincere and unprejudiced advocate for Jewish culture. It led to a friendship with Israel Zangwill, an emerging British-Jewish novelist, and an invitation to join the newly formed Russo-Jewish Committee, which reported on pogroms and other anti-Semitic behaviour in Russia while attempting to manage the heavily politicized issue of the immigration of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe to the UK and US.48 In 1891, Caine’s emergence as a literary spokesperson for assimilationist Jews led the British Chief Rabbi, Hermann Adler, to suggest he visit Russia to report on the condition of Jews in the western borderlands. The Russo-Jewish Committee would provide an interpreter, and Caine could carry out abundant fieldwork for the Russo-Jewish romance he was contemplating.49

Caine’s support of the Jewish community in the UK was, of course, anticipatory plagiarism of Tolstoy’s celebrated patronage of the Russian Doukhobor sect. In the 1890s, the pacifist Doukhobors’ civil disobedience, including abstention from military service, had provoked increasingly punitive measures against them, such as internal exile. Nor were they permitted to emigrate in order to pursue their way of life in a more tolerant milieu. In 1895, Tolstoy published his first public request (in the London Times) for the Doukhobors to be allowed to leave Russia, followed by a second appeal a year later and in 1898, a successful petition to Tsar Nicholas II.50 Meanwhile, the need to raise money for the Doukhobors’ travel stimulated Tolstoy to complete Resurrection in 1899. Its ‘phenomenal and unprecedented’ overseas success was orchestrated by Tolstoy’s international network of followers, notably Vladimir Chertkov, whose ‘Free Age Press’ in Essex was founded in 1900 to distribute translations of Tolstoy’s writings, particularly those banned or censored in Russia.51 Resurrection was immediately and widely translated; it ran to multiple editions within a year; and the sale of the French and British rights, accompanied by generous gifts from private donors, allowed Chertkov and his network, assisted by Tolstoy’s son Sergei, to charter ships for the Dukhobors and ultimately to help over 7,500 of them travel to sanctuary in Canada by mid-1899.

Although the logistics were on a much smaller scale for Caine’s trip to Russia undertaken seven years earlier in the summer of 1892, both journeys required diplomatic delicacy. Caine was supposed to travel discreetly, in order to avoid provoking the Russian government, who might decide to impede his trip. Unwisely, in 1891 Caine mentioned his forthcoming journey to a journalist, provoking a media flurry about his so-called ‘Russian mission’,52 reproaches from the Russo-Jewish Committee, and a clarification from Caine himself:

My object is a simple and, I trust, a harmless one. It is that of studying on the spot the life of the Russian Jews. I shall go, if I am allowed to do so, with an open mind, easily touched to sympathy with terrible sufferings, but primed with no apocryphal horrors; indignant at injustice, but holding no wild and mischievous notion of the cruelty of the Russian people; resolved to find the truth and equity of the question, as far as my powers of observation and judgement will permit; but determined to say exactly what I feel, even if that should be partly a warning to the Jews themselves to avoid those dangers which are said to have helped bring these evils upon them.53

Caine’s insistence on his status as an independent author did not fully convince journalists: as demonstrated by this comparatively measured commentary from The British Weekly (printed a few days after Caine’s statement above), most felt that he must have, at the very least, a literary agenda. Note the facile reference to Tolstoy.

It hardly needed Mr Caine’s letter to the Times to dispose of the absurd statement that he was going to Russia with a brief from a Jewish society, pledged to denounce Russia and to be blind to any faults on the other side. […] The other day, when Count Tolstoi was consulted on the subject of the famine in Russia, he had no very immediate remedy to suggest; but he thought the hearts of the rich might be effectively appealed to were someone to write a book. So did the Russo-Jewish Committee; and they have asked Mr Caine to write one. It is not a very speedy method, but that it can be successful, ‘Uncle Tom’—which, however, was not written by suggestion—can testify.54

Not every report was as forgiving:

The popular novelist and the Czar of All the Russias being the only two omnipotent persons left, it is very right and proper that they should try conclusions with one another […]. We do not know whether it is more immoral for a novelist to hold a brief than for a barrister to do so; but, in accepting this commission from the London Jews, Mr. Hall Caine is at least consenting to hold their brief, is he not? But Holy Russia can look after herself. Let Mr. Hall Caine see to it that, after being duly tried, he is not sent off to Siberia.55

When after several postponements, Caine reached the Continent in midsummer 1892, he travelled on to the Russian borderlands via Brussels and Berlin. In Berlin, awaiting his interpreter, Caine spent time with his friend Emil Franzos, who had moved from the territory of modern Ukraine to Germany in the hope of avoiding persecution. Caine had not learned his lesson about unwanted self-publicity: Heinemann warned him again against advertising his whereabouts lest ‘the enemy’ (presumably Russian government agents) take action against him, while insisting:

I am strongly of opinion [sic] that you see a great deal more of the persecution of the Jews in Berlin than you will ever see in Russia. What Franzos tells you I consider worth nothing at all. It is not people of his calibre who conquer the world, but the English who go out unafraid, as you did, until you met him.56

In keeping with his opinion of English courage, Heinemann recommended an ambitious route into Russia: ‘south right through Hungary, and get in from the Black Sea through the Crimea’.57 Rumours of cholera in the borderlands compelled Caine to abandon his plans to see St Petersburg and Moscow after visiting only a few cities such as Krakow, Warsaw and Breslau; the fact that his Jewish interpreter was not permitted to enter Russian territory was an added complication. On his return to Britain, Caine delivered a detailed, deeply felt report about the poverty and deprivation he had witnessed to the Jewish Working Men’s Club, subsequently published in the Jewish Chronicle.58 Caine supported Zionism; and as late as 1921, he was still raising funds to alleviate famine in Russia.59 While not on the same scale as Tolstoy’s support for the Doukhobors, Caine’s advocacy of Jewish culture was a lifetime commitment, and certainly not a mere publicity stunt for The Scapegoat or for his projected, never-written Russo-Jewish novel.

Given that Caine was unable to refrain from advertising his journey to Russia, he clearly used his status as a goodwill ambassador for Jews to promote his own work. However, even Tolstoy’s high-profile advocacy of the Doukhobors was not without a smidgeon of self-publicity. While by the 1890s, Tolstoy was seen as the leader of international pacifism, the various pacifist factions were divided and ineffective. Tolstoy was frustrated by the lack of political reform following his argument, cogently expressed in The Kingdom of God and elsewhere, that individual enlightenment prefigures enlightened societies. The Doukhobor Rebellion of 1895, instigated by the sectarians’ spiritual leader Petr Vasil’evich Verigin, provided a timely opportunity to re-energize Tolstoy’s message. Although the Doukhobors were not Tolstoyans, Verigin’s personal philosophy coincided conveniently with Tolstoy’s principles.60 Hence, while neither Resurrection nor the Doukhobors’ resistance were publicity stunts, they display Tolstoy’s and Verigin’s ability to adroitly manipulate audiences and harness public sympathy.61 The fact that both Hall Caine and Tolstoy could be savvy media operators detracts neither from their pacifism, nor from their impartial faith in the power of imaginative literature to unite disparate cultures. As Caine wrote in 1908:

In the progress of the nations from the barbarity of statecraft I see no force that is so surely making for the peace of the world as the force of education whereby the great national literatures are becoming one literature. I may hate and loathe the Russian government, and in any difference it may have with the government of England I may be a rabid Englishman, but when I open the books of Tolstoy and enter with him into the houses of the moujiks, and live their lives and share their joys and sorrows, I love the Russian people and hate the thought that my country can ever go to war with them.62

Caine and Tolstoy

As Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s personal secretary in the last year of the artist’s life, the young Hall Caine met or corresponded with many luminaries. He notes in a memoir that ‘Tourgenieff’ [sic], on a visit to London, attempted to call on Rossetti after the latter had recovered from a seizure.63 Caine’s biographer comments that ‘[t]here were few men Caine would have liked to meet more but he had to put him off along with the rest. Turgenev […] died in 1883 and Caine never again had a chance to meet him’.64 It was Tolstoy, however, who quickly became Caine’s lodestar among Russian writers and indeed among all authors. On tour in America to promote The Christian, Caine praised Anna Karenina’s successful combination of realism and idealism: ‘I claim for Victor Hugo and Count Tolstoi that, with Walter Scott, they will in the time to come be recognized at [sic] the three greatest novelists of the nineteenth century’.65 Although Shakespeare had been (with Ruskin) Caine’s earliest and most enduring idol, Caine even defended Tolstoy’s critique of the bard. Caine wrote to a friend: ‘At present the spectacle of utter idolatry, as though every word in Shakespeare were divinely inspired, is, as Tolstoi says, a great evil and a great untruth’.66

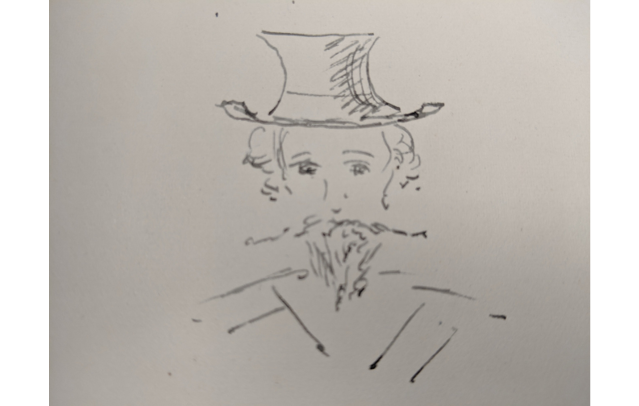

Fig. 2. Hall Caine looking Tolstoyan. Hall Caine at Tynwald Fair, unknown photographer (1930). PG/0203, from the archive of Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (1853–1931), Manx National Heritage Museum, Douglas, Isle of Man. Used with permission of the Manx National Heritage Museum, https://www.imuseum.im/search/collections/archive/mnh-museum-114514.html.

Caine’s attempts to meet or correspond with Tolstoy were, as we have seen, frustrated first by the cholera epidemic of 1892 and secondly by the Russian author’s refusal even to reply directly. An 1890 note from Tolstoy’s daughter Tat’iana, assures Caine blandly that her father ‘is much moved by your high opinion of the direction in which he labours and by your sympathy to his aims’.67 It must have galled Caine that Tolstoy followed up his anodyne response to the gift of The Bondman with consistently negative assessments of The Christian, whose titular hero, the radical preacher John Storm, was the most consciously Tolstoyan of all Caine’s characters. Caine probably read the report by Harold Williams, a Manchester Guardian correspondent who visited Tolstoy at his Iasnaia Poliana estate in 1905, that ‘[Tolstoy’s] estimate of Miss Marie Corelli and of Mr. Hall Caine, particularly of the latter, was extremely unfavourable’.68 It was fortunate, however, that Tolstoy’s introductory essay to the Russian translation of Der Büttnerbauer (1895) by the German realist novelist Wilhelm von Polenz (1861–1903) has never been translated into English. Ironically enough, the novel’s Russian title was The Peasant (Krest’ianin), not to be confused with its near-homophone Khristianin (The Christian). In this essay, Tolstoy singled out Caine’s Christian for unfavourable comparison with von Polenz’s ‘indubitably beautiful’ (‘nesomnennoe prekrasnoe’) work:

Books, journals, and especially newspapers have become in our times immense monetary undertakings, requiring the maximum number of customers for their success. The interests and tastes of the majority of customers are always low and crude, and therefore for the success of a printed work it is necessary for that work to respond to the requirements of the greater number of customers, i.e. to touch on low interests and correspond with crude tastes.

[…]

Moreover, thanks to chance or excellent advertising, several bad books, such as Hall Caine’s The Christian, a novel which is false in content and not literary, which has sold a million copies, receives, like eau-de-cologne or Pears soap, vast fame which is not justified by its virtues.69

Still worse than this (but also mercifully unknown to Caine during his lifetime) was the verdict Tolstoy scribbled to his daughter Tat’iana, who had formerly corresponded with Caine. Tatiana’s letter to her father has not been preserved, but she must have mentioned The Christian. Perhaps she was noting receipt of a gift copy (possibly the volume still in the Iasnaia Poliana library today). Tolstoy responded: ‘Hall Caine is a publicist (‘reklamist’) and his “Christian” is a dreadful book (‘preskvernoe sochinenie’)’.70

It was a poor return for decades of mutual theft.

Conclusion

As Bayard reminds us, the benefit of anticipatory plagiarism as an approach to literary criticism lies in the way it reveals how ‘each text enriches the other, and even transforms it’. In the special case of reciprocal plagiarism, ‘each text is doubled under the influence of the text [which it has] plagiarized, which plagiarizes certain points from it in its turn’.71 Taking Hall Caine and Tolstoy’s interactions as an example not only of plagiarism, but of reciprocal plagiarism, we have identified two major shared contraintes. The first is an unusual twist on the tired convention of the fallen woman: the trial of said woman by her former lover, followed by his sincere repentance. The second common contrainte is the metaliterary use of fictional melodrama to benefit a religious group threatened by persecution—for Tolstoy, the Doukhobors; for Caine, the Russian Jews. Our approach reveals that, all Bayardian conceits aside, Hall Caine did actually anticipate one of Tolstoy’s major literary themes; and that Caine, from his stronghold ‘Greeba Castle’ on the Isle of Man, did in fact precede the sage of Iasnaia Poliana’s defence of the Doukhobors by effectively combining self-promotion and humanitarian advocacy to help the vulnerable Jewish community. In fact, the criticisms Tolstoy levelled against Caine (indulgence in melodrama; self-advertisement) appear intrinsic to his own aesthetic and professional practice. By studying these two writers as a mutually influential dyad, we realize how much they shared thematically and philosophically—and how, for almost three decades, they enjoyed arguably equal fame.

Moreover, since Caine outlived Tolstoy yet continued to plagiarize him (as both the epigraph and ruling metaphor of The Master of Man demonstrate), we can apply the Bayardian term revenant to Tolstoy’s role in mentoring his fellow author: ‘a writer from the past with whom a [later] writer holds a dialogue’.72 In life, Tolstoy viewed Caine’s work with contempt: in death, ‘separated by the illusory barrier of time, [authors] found a means of working together’.73 Bayard envisaged the latter-day reciprocal plagiarist enjoying what he called ‘a privileged connection’ with his predecessors, ‘as with benevolent ghosts from whom he occasionally asks, despite the intervening years and because he knows them to be located beyond time, advice and protection’.74 In the spirit of Flann O’Brien, who wrote a series of comic vignettes picturing John Keats (born in 1795) and George Chapman (who died in 1634) jovially if anachronistically sharing a bachelor existence,75 I like to imagine Lev Tolstoy and Hall Caine reconciled as literary chums in the ahistorical space of reciprocal plagiarism, setting the world to rights with a winning combination of spiritual rhetoric and titillating melodrama.

Fig. 3. Hall Caine’s tombstone in Maughold Churchyard, Isle of Man, sculpted by Archibald Knox. Photograph by author (2019). Copyright author’s own.

1 The author thanks Dr Richard Storer (Leeds Trinity University), Dr Cathy McAteer (University of Exeter), Professor Jacob Emery (Indiana University Bloomington) and Professor Timothy Langen (University of Missouri) for their invaluable feedback on this chapter. I also greatly appreciate the help and resources generously shared with me by the staff of the Manx National Heritage Museum, especially Ms Wendy Thirkettle, without whose assistance I would never have discovered Hall Caine’s views on Tolstoy.

2 Robert Ross, ‘The Literary Log’, The Bystander, 19 October 1910, pp. 144–45 (p. 144). Although Ross never reveals the name of the host on this occasion, his coy description of ‘a distinguished man of letters’ and ‘a fluent Russian scholar’ suggests none other than Maurice Baring, whose monograph Landmarks in Russian Literature was published by Methuen & Co. in 1910; and who is known to have shared a house in Westminster with his friend Auberon Herbert, the ninth Baron Lucas, before the outbreak of the First World War. See Richard Davenport-Hines, ‘Baring’s Religious Faith’, Chesterton Review, 34:1/2 (2008), 311–14 (pp. 312–13), https://doi.org/10.5840/chesterton2008341/2122.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Frederick Whyte, William Heinemann: A Memoir (London: Jonathan Cape, 1928), pp. 52–53.

6 On Corelli’s reincarnation as Lucia, see Teresa Ransom, The Mysterious Miss Marie Corelli: Queen of Victorian Bestsellers (Stroud: Sutton, 1999). On her extreme popularity and its complete eclipse following the First World War, see Richard L Kowalczyk, ‘In Vanished Summertime: Marie Corelli and Popular Culture’, Journal of Popular Culture, 7:4 (Spring 1974), 850–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1974.0704_850.x. On Stoker’s dedication, ‘Hommy-Beg’, literally ‘small Tommy’, was an affectionate Manx-vernacular nickname for the diminutive Caine. For more on this moniker and on the Stoker-Caine relationship, see Richard Storer, ‘Beyond “Hommy-Beg”: Hall Caine’s Place in Dracula’, in Bram Stoker and the Gothic: Formations to Transformations, ed. by Catherine Wynne (London: Palgrave, 2016), pp. 172–84, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137465047_12.

7 For more on Tolstoy’s Tauchnitz readings and his opinions about Wood and Braddon, see Edwina Cruise, ‘Tracking the English Novel in Anna Karenina: who wrote the English novel that Anna reads?’, in Anniversary Essays on Tolstoy, ed. by Donna Tussing Orwin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 159–82, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511676246.009.

8 See Galina Alekseeva, ‘Dickens in Leo Tolstoy’s Universe’, in The Reception of Charles Dickens in Europe, ed. by Michael Hollington (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), pp. 86–93.

9 Anon., ‘Hall Caine, The English Victor Hugo’, Sunday Words, 8 June 1890.

10 For example, when Caine’s The Master of Man (1921) appeared, the Daily Graphic critic was confident that it would ‘stand as the English “Anna Karenina”’; the Leeds Mercury claimed that ‘it places him [Caine] to the same rank, as a great world novelist, with Zola, Hugo and Tolstoy’; and the critic J. Cuming Walters, writing in the Manchester City News, wrote that ‘Sir Hall Caine in “The Master of Man” has shown himself to be the English Tolstoy’.

11 Uncredited introduction to The Bondman, in Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine, Complete Works of Hall Caine (Hastings: Delphi Editions, 2016), online edition [n.p.].

12 T. L. Tolstaia, letter to Hall Caine, 3 August 1890. The papers of Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (1853–1931), MNH MS 2306, held in the Manx National Heritage Library and Archives. Quoted courtesy of Manx National Heritage.

13 Hall Caine, ‘Author’s Note’, in The Master of Man: The Story of a Sin (Philadelphia, PA and London: J. P. Lippincott, 1921), online edition, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/61865/61865-h/61865-h.htm. This later correspondence has not been preserved.

14 Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine, anonymous blurb for The Christian (London: Cassell & Co., 1927).

15 As ‘Master and Man’ was first translated into English in 1895 by S. Rapapert and J. C. Kenworthy, and subsequently re-translated by Constance Garnett and by Louise and Aylmer Maude, Caine would have had no difficulty in reading a copy.

16 Holmes first appeared in print in A Study in Scarlet (1887).

17 Pierre Bayard, Le Plagiat par anticipation (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2009), p. 38. My translation.

18 Ibid., p. 53.

19 Ibid., p. 154.

20 See Whyte, William Heinemann, p. 174; and Vivien Allen, entry on Sir Hall Caine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://www.oxforddnb.com.

21 Oscar Wilde, The Decay of Lying [1889] (New York: Brentano, 1905), page unknown.

22 See V. A. Zhdanov’s detailed reconstruction of Koni’s anecdote in Tvorcheskaia istoriia romana L. N. Tolstogo “Voskresenie” (Moscow: Sovetskii pisatel’, 1959), pp. 3–6.

23 Lyof N. Tolstoi, Resurrection, trans. by Louise Maude, in The Complete Works of Lyof N. Tolstoi (New York: Thomas Crowell & Co, 1898–1911), XXIII-XXIV (1900), p. 6, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1938/1938-h/1938-h.htm.

24 Ibid., p. 157.

25 Ibid., pp. 95–99.

26 Hall Caine, The Manxman (Part IV, Chapter XXII), in Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine, Complete Works of Hall Caine (Hastings: Delphi Editions, 2016), online edition [n.p.].

27 For a detailed timeline of Tolstoy’s composition of Resurrection, see Zhdanov, Tvorcheskaia istoriia romana L. N. Tolstogo “Voskresenie”, esp. pp. 9–49.

28 Tolstoi, Resurrection, pp. 121–22.

29 Count Leo Tolstoy, The Kingdom of God Is Within You, trans. by Constance Garnett, 2 vols (London: William Heinemann, 1894), II (1894), p. 265.

30 See Rosamund Bartlett, Tolstoy: A Russian Life, pp. 387–94, for the background and aftermath of Tolstoy’s excommunication, which was widely perceived at home and abroad as an act of petty political vengeance.

31 Hall Caine, The Woman Thou Gavest Me, Chapter 68, online edition, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14597/14597-h/14597-h.htm.

32 Whyte, Heinemann, pp. 284–85.

33 Hall Caine, The Manxman (Part IV, Chapter XXII), online edition [n.p.].

34 Count Leo Tolstoy, The Kingdom of God Is Within You, II, pp. 237–38.

35 Hall Caine, ‘The Jew in Literature’, speech to the Maccabeans, printed in The Literary World, 20 May 1892, 482–84, p. 482.

36 Hall Caine, ‘Author’s Note’, in The Master of Man, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/61865/61865-h/61865-h.htm#chap0102.

37 Hall Caine, The Master of Man, online edition.

38 Tolstoi, Resurrection, p. 270.

39 For more on Tolstoy’s diaries, and how his wife Sofiia Andreevna reacted to reading them, see Bartlett, Tolstoy, p. 154 and pp. 157–58.

40 See W. T. Stead, ‘Count Tolstoi’s New Tale: With a Condensation of the Novel [The Kreutzer Sonata]’, Review of Reviews, 1 (April, 1890), 330.

41 Interview with Hall Caine, ‘Unmanliness in Modern Literature’, Pall Mall Gazette, 24 June 1890. British Library Newspapers, link.gale.com/apps/doc/Y3200423930/BNCN?u=exeter&sid=BNCN&xid=400309fa. Accessed 22 Mar. 2021.

42 For example, in Resurrection (pp. 156–57), the pregnant and despairing Maslova almost emulates Anna Karenina by throwing herself under a train, but she changes her mind after feeling her unborn child move.

43 L. N. Tolstoi, ‘Po povodu dela Skublinskoi’, 18 February 1890, http://tolstoy-lit.ru/tolstoy/chernoviki/po-povodu-dela-skublinskoj.htm. For more on baby farms in late Imperial Russia, see ChaeRan Y. Freeze, ‘Lilith’s Midwives: Jewish Newborn Child Murder in Nineteenth-Century Vilna’, Jewish Social Studies, 16:2 (Winter 2010), 1–27, https://doi.org/10.2979/jss.2010.16.2.1.

44 Caine was not alone among authors of his generation in attacking baby farms: George Moore’s bestselling Esther Waters (1894) excoriates a similar institution.

45 Hall Caine, personal letter to the Lord Mayor of London, 25 October 1909. The papers of Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (1853–1931), MNH Box 63, held in the Manx National Heritage Library and Archives. Quoted courtesy of Manx National Heritage.

46 For more substantive discussion of Caine’s relationship with the Jewish community and his literary representation of Jewish characters, see Anne Connor, ‘The Spiritual Brotherhood of Mankind: Religion in the Novels of Hall Caine’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Liverpool, 2017), pp. 154–96, https://search.proquest.com/docview/2500014798.

47 Hall Caine, ‘The Jew in Literature’, 483–84.

48 On this important transitional period in British Jewish affairs, see Sam Johnson, ‘Confronting the East: Darkest Russia, British Opinion and Tsarism’s “Jewish question,” 1890–1914’, East European Jewish Affairs, 36:2 (2006), 199–211, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501670601026781; and David Cesarani, The Jewish Chronicle and Anglo-Jewry, 1841–1991 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), esp. pp. 32–102.

49 Anne Connor, ‘Spiritual Brotherhood of Mankind’, pp. 180–81.

50 On Tolstoy’s early advocacy of the Doukhobors, see Nina and James Kolesnikoff, ‘Leo Tolstoy and the Doukhobors’, Canadian Slavonic Papers, 20:1 (1978), 37–44 (pp. 37–38), https://doi.org/10.1080/00085006.1978.11091554; and Josh Sanborn, ‘Pacifist Politics and Peasant Politics: Tolstoy and the Doukhobors, 1895–1899’, Canadian Ethic Studies, 27:3 (1995), 52–71, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/pacifist-politics-peasant-tolstoy-doukhobors-1895/docview/1293167948/se-2?accountid=10792.

51 Bartlett, Tolstoy, p. 378. On the history of the Free Age Press, see Michael J. De K. Holman, ‘Translating Tolstoy for the Free Age Press: Vladimir Chertkov and His English Manager Arthur Fifield’, The Slavonic and East European Review, 66:2 (1988), 184–97, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4209734.

52 Anon., ‘Mr. Hall Caine’s Russian Mission’, The British Weekly, 15 October 1891.

53 Hall Caine, ‘Mr Hall Caine and the Russian Jews’, Letters to the Editor, The Times, 12 October 1891.

54 Anon., ‘Mr. Hall Caine’s Russian Mission’, The British Weekly, 15 October 1891.

55 Anon., The Birmingham Daily Gazette, 6 October 1891.

56 William Heinemann, letter to Hall Caine, n.d. The papers of Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (1853–1931), MNH Box 63, held in the Manx National Heritage Library and Archives. Quoted courtesy of Manx National Heritage.

57 Ibid.

58 Hall Caine, ‘Scenes on the Russian Frontier’, Jewish Chronicle, 16 December 1892.

59 Vivien Allen, Hall Caine: Portrait of a Victorian Romancer (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997), p. 385.

60 See April Bumgardner, ‘The Doukhobors: History, Ideology, and the Tolstoy-Verigin Relationship’ (unpublished MPhil thesis, University of Glasgow, 2001), esp. pp. 94–97, http://theses.gla.ac.uk/76168/1/13818981.pdf.

61 See Sanborn, ‘Pacifist Politics and Peasant Politics’, 52–71.

62 Hall Caine, My Story (London: William Heinemann, 1908), p. 387.

63 Ibid., p. 215.

64 Allen, Hall Caine, p. 136.

65 Hall Caine, drafts for American speeches; draft address to the Pen and Pencil Club in Philadelphia, n.d., pp. 25–26. The papers of Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (1853–1931), MNH MS 09542, held in the Manx National Heritage Library and Archives. Quoted courtesy of Manx National Heritage.

66 Hall Caine, personal letter (addressee unknown), 27 November 1906. The papers of Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (1853–1931), MNH MS 09542, held in the Manx National Heritage Library and Archives. Quoted courtesy of Manx National Heritage.

67 T. L. Tolstaia, letter to Hall Caine, 3 August 1890.

68 Harold Williams, ‘A Visit to Count Tolstoy’, Manchester Guardian, 5 February 1905.

69 L. N. Tolstoi, ‘Predislovie k romanu V. Fon-Polentsa « Krest’ianin »’, in L. N. Tolstoi, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii i pisem v devianosto tomakh, ed. by V. G. Chertkov, 90 vols (Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo khudozhestvennoi literatury, 1928–58), XXXIV (1952), pp. 270–78 (p. 278).

70 L. N. Tolstoi, letter to T. L. Sukhotina, 8 March 1901, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii, LXXIII (1954), pp. 47–48 (p. 48).

71 Bayard, Le Plagiat, p. 54.

72 Ibid., p. 154.

73 Ibid., p. 55.

74 Ibid.

75 Myles na Gopaleen (Flann O’Brien), The Various Lives of Keats and Chapman (London: Hart-Davis MacGibbon, 1976).