10. Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Racial Injustice in the Classical Music Professions: A Call to Action

© Susan Feder and Anthony McGill, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0242.10

Introduction

I grew up on the South Side of Chicago with a wonderful family of parents, Demarre and Ira, and an older brother, Demarre. My earliest experiences with music came from my parents’ love of music and art. We had music playing all the time at home. We also had an art room, as my parents were both visual artists and art teachers in the Chicago Public Schools. They believed music was an important part of a well-rounded education and just one piece of the puzzle to raise successful children. My brother, now Principal Flutist of the Seattle Symphony, fell in love with music and started practicing hours and hours a day before I ever played an instrument. I wanted to be just like him, so when it was time to pick up an instrument, I jumped at the chance to play a wind instrument. The saxophone was my first choice, but it was too big for me, so I eventually settled on the clarinet.

My early years were well supported by a community of mentors, parents, and teachers who gave me the base I needed to thrive as a young musician. One of my earliest musical experiences was as a member of an ensemble of young Black classical musicians from Chicago called the Chicago Teen Ensemble. This ensemble was led by my first music teacher, Barry Elmore. We toured around a lot of the churches on the South Side of Chicago and performed arrangements of famous classical works. These early experiences of having older musician peers and friends that looked like me made me feel welcome in music and contributed to my self-confidence as a young clarinet player. I also attended the Merit School of Music, where I was surrounded by a diverse group of young people who were also interested in music. This community gave me a sense of pride that encouraged my love of music and growth as a person. Merit gave me scholarships to music camps and introduced me to famous teachers. Eventually, I joined the Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra and continued on this serious musical path. A few years later, I left home to attend the Interlochen School of the Arts. From there I went on to the Curtis Institute of Music, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, and then to my current seat as the Principal Clarinetist of the New York Philharmonic.

I had plenty of love and support throughout my career, but I also had huge obstacles to overcome. Being Black and from the South Side of Chicago came with its share of preconceived notions about who I was, and I frequently felt like I had to prove myself in order to survive. There were many times I had to put blinders on and pretend that comments didn’t hurt, or that I didn’t understand the underlying message behind certain statements. I had to ignore many racially charged words from peers and adults in order to stay focused on my goals. These issues have not disappeared as I’ve achieved higher levels of success. They’ve continued to occur throughout my career and at every stage of my life. I’ve had to deal with being asked why I was attempting to enter music buildings because I didn’t look like I belonged there. I had a person tell me after a Carnegie Hall solo appearance that I sounded as though I were playing jazz in a lounge bar and that it was inappropriate for the style of the composer. I’ve had people ask me why I chose classical music, as if it were a field that is not designed for people like me. I’ve heard board members tell jokes that are insensitive at best and racist at worst.

In addition to these few examples, there is the feeling that one cannot speak up about these issues lest people think you are angry or disgruntled for made-up reasons. The burden people of color have to deal with while trying to achieve the greatest heights in the field, under intense pressure, is a heavy one to bear.

We must do better in order for there to be progress. We need to have transparent discussions and training surrounding issues of bias, racism, and exclusion in classical music. In addition, we need to examine the history of racism in our country in order to understand how this has contributed to the current state of the field. After this work, we should continue to strategize about what actions to take in order to move the needle regarding representation onstage, backstage, in boardrooms, and in administrations. Without proper knowledge and support, all of the necessary attention to pathways, mentorship, education, etc., will not allow all participants to thrive and engage in an inclusive, welcoming industry. I hope that with honest, immediate action, we will begin to see necessary change in our industry.

A Call to Action

The conversation of diversity in classical music is still relatively new, but it’s one in which more organizations have been engaging for the past several years. The conversation of racism in classical music is a little different, though. Not only does it require us to take a second look at ourselves, but also so much of the music that’s become ubiquitous to the genre.

—Garrett McQueen, bassoonist and radio host (2020)

The absence of Black and Latinx musicians in the classical music professions in the United States is deeply rooted in intertwined issues of access and structural racism. Regarding access, the challenges center on how to level the playing field so that talented young musicians of color, from an early age, have the same opportunities in instruction and mentorship as white and East Asian students who often come from more comfortable socio-economic circumstances. These are issues that can be addressed with financial resources. The second issue is far harder to solve. Once students pass through the formidable hoops of formal training, what will it take for arts institutions to overcome the structural racism, microaggressions, and unconscious bias that in combination have made it overwhelmingly difficult for most musicians of color2 to win auditions, feel welcome, achieve tenure, or be cast, hired, and programmed at the institutions in which they seek to work?

This chapter will take a brief look at the historical circumstances that have amplified racial injustice, current attempts to create systemic and scalable training pathways for BIPOC musicians, and the ongoing barriers to improving levels of participation. Evidently, it has taken the dual challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and the national outrage following the May 2020 murder of George Floyd to unleash a long overdue reckoning towards implementing positive change. Chafing against pandemic shelter-in-place orders, and with the ascendency of social media as a dominant form of communication, the structures that have upheld racism and systemic oppression in the United States have come under greater scrutiny than at any time since the Civil Rights era.3 Even as classical music institutions remain physically shuttered, they cannot ignore the zeitgeist without risk of descending into irrelevance. While arts and culture organizations have overwhelmingly responded with statements of support for Black Lives Matter, now is the time to put actions in place to accelerate the pace of change.

As the largest employer of classically trained musicians in the United States, American orchestras bear a particular responsibility, and will be the focus of this chapter.4 A disturbing review of discriminatory practices in the summer 2020 issue of the League of American Orchestras’ Symphony magazine, by the arts administrator, educator, and trumpeter Dr. Aaron A. Flagg, reminds us that “the history of discrimination in America’s classical music field, particularly in orchestras, is not discussed or studied or commonly known, because it is painful, embarrassing, and contrary to how we want to view ourselves” (Flagg, 2020: 36). Flagg cites an “ignored and uncelebrated history of minority artistry in classical music (by composers, conductors, performers, and managers); ignorance of the history of discrimination and racism against classical musicians of African-American and Latinx heritage by the field; and a culture in the field that is indifferent to the inequity, racial bias, and micro-aggressions within it” (30). He also reflects on the role of musicians’ unions, providing a history of their segregation, which “like that of other industries in the late nineteenth century, came with the social prejudices of the time, which discouraged solidarity among racially diverse musicians. Black musicians generally could not join white unions and were treated as competitors in the marketplace” (33). Instead, they formed their own unions, but in the process were largely disenfranchised from job notices, rehearsal facilities in union halls, and job protections until the 1970s, when they were fully integrated into the American Federation of Musicians. Flagg observes that Black musicians only began to be hired in major orchestras beginning in the late 1940s, and even into the 1960s only in rare instances.

Today, although the US Census Bureau estimates that Black and Latinx people make up nearly 32% of the US population, the percentage of them in US orchestras stubbornly hovers below 4% (although it is somewhat higher in smaller budget orchestras than the larger ones; see League of American Orchestras, 2016). This rate has not improved significantly in more than a generation, despite the rise of important organizations and initiatives devoted to intensive pre-professional training for BIPOC musicians5 and prominent performing ensembles.6

Equally concerning has been the minimal impact of fellowship programs. Since 1976, some twenty-three US orchestras have hosted such programs for BIPOC musicians. As an enduring strategy for the individuals they served, orchestral fellowships have been demonstrably effective. But they have been insufficient in scope to achieve a critical mass of professional BIPOC musicians. Even more discouraging, those orchestras that hosted fellowship programs over this forty-plus year period evince little evidence that they are any more diverse today than those that did not (League of American Orchestras, 2016). The culture of orchestras has not changed, whether with regard to the consistency of BIPOC conductors and soloists onstage, more regular programming of music by Black and Latinx composers, or more BIPOC leaders in all levels of administrative roles and on orchestra boards. Taken together, such changes would help reassure BIPOC musicians that they indeed belong in this profession. Moreover, all too often, those who have achieved positions are expected to function in the uncomfortable, unreasonable, and untenable positions of being spokespeople for their race when engaging with communities of color, at donor events, during educational activities, or in internal discussions regarding diversity, equity, inclusion (DEI), and racism.

Why then encourage BIPOC musicians toward careers in orchestras, one might well ask? There are many compelling reasons:

- As noted above, up until the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, orchestras offered stable employment with salaries and benefits to large numbers of artists and will presumably do so again in the coming years;

- For well over a decade, orchestras have begun to reframe their missions as serving their communities through the power of great music in addition to aspiring to perform concerts at the highest levels of excellence. They need diverse perspectives to do so effectively, especially in light of demographic shifts across US urban centers;

- As they elevate community service, orchestras will need to hire more entrepreneurial musicians. Already, some orchestras are considering skills such as teaching artistry, curatorial curiosity, chamber ensemble playing, and public speaking as crucial criteria for employment, after an audition is won but before a job is offered. Such orchestral positions should be more attractive to a generation of musicians who seek variety in their careers;

- Those orchestras that have diversified their programming (both in terms of repertoire and concert formats) and moved away from a tradition of fixed subscription models, have successfully attracted younger, more diverse audiences, countering the commonly held perceptions of orchestras that they are exclusively by, for, and about white people; serve an aging and elite audience that can afford expensive tickets, or have a “broken business model”;

- In recent years, and in unprecedented numbers, orchestras have begun to regard DEI as core values across their institutions. Many are now making intentional efforts to come to grips with racist pasts, improve BIPOC participation in their staffs, boards, and programming, and cultivate more inclusive and nurturing environments, even as the diversification of musician hiring remains complicated by the “blind audition” process (see Tommasini, 2020);

- Amplifying Voices, an initiative by New Music USA in partnership with the Sphinx Organization launched in January 2020, is fostering transformation of the classical canon through co-commissions and collective action toward more equitable representation of composers in classical music. To date, twenty-four orchestras have committed to increased programming of works by composers of color during forthcoming seasons.

All this notwithstanding, the fact remains that attaining permanent orchestral employment is a challenge for all musicians, regardless of race or ethnicity: the supply of talent far exceeds demand. And although there are more than 1,200 professional orchestras in the US, with rosters as large as 100 musicians, players tend to receive tenure within a year or two of joining an orchestra. Openings thus remain rare and extremely competitive. Still, in the years just prior to the pandemic, many of the orchestras that had reduced the size of their permanent rosters after the 2008 recession through retirement and attrition had stabilized their financial positions sufficiently to begin replenishing their permanent musician ranks. Even now, in the wake of pandemic-related furloughs and layoffs, some long-tenured musicians may opt to retire and claim their pensions, creating opportunities for generational turnover once orchestras resume performing. The pace of hiring may slow temporarily, but pick up again in the next few years.

Another less visible factor regarding employment opportunities: at any given performance, the number of musicians substituting for permanent players can be upwards of 10% of the roster. More intentional recruitment of BIPOC musicians as subs would provide them with intensive professional orchestral experience. Even if temporary employment is less attractive than more traditional forms of job security, musicians at all levels of achievement are accustomed to operating in a “gig economy,” combining teaching, administration, and orchestral, solo, and chamber performances as synergistic elements of their careers.

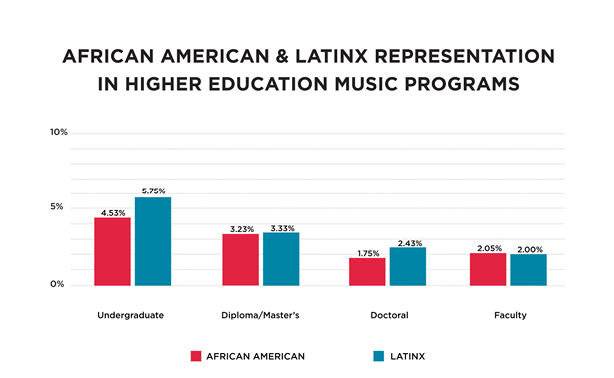

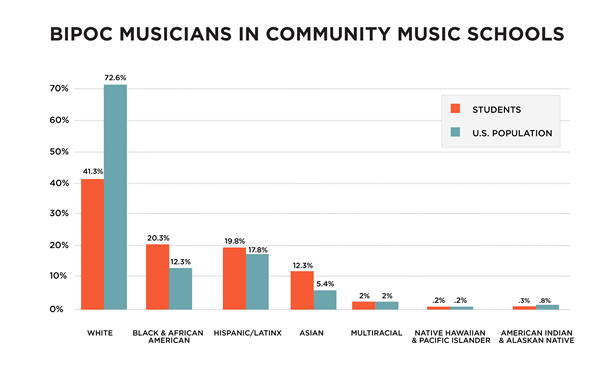

Skeptics might ask if there is a sufficient pipeline of BIPOC musicians to populate American orchestras? And if not, what are the pathways to opening the spigots? While statistics on BIPOC enrollment in higher education are sobering (see Fig. 1), the racial/ethnic breakdown of younger students enrolled in early-access programs at community music schools is startlingly different. Indeed, as a result of the missions and locations of community schools—often in urban centers and in neighborhoods close to their targeted populations—enrollment percentages for African-American, Latinx, and Asian-American students actually exceed those of the US population overall (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 African American and Latinx representation in higher education music programs. Data drawn from National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) 2015-16 Heads Report. © NYU Global Institute for Advanced Study. CC-BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 2 BIPOC musicians in community music schools. Data drawn from US Census Bureau, 2011 American Community Survey; National Guild for Community Arts Education Racial/Ethnic Percentages of Students Within Membership Organizations. © NYU Global Institute for Advanced Study. CC-BY-NC-ND.

Thus, a strong foundation grounds the prospects for creating more effective pathways for BIPOC musicians. Despite formidable social and economic barriers, academic pressures, and competition from sports and other extracurricular activities as students enter middle and high school, might attrition rates be staunched by earlier and more intentional interventions? A supportive ecology would include such elements as access to private instruction, ensemble playing, fine instruments, college counselling for students and their families, and strong mentoring.

Effectuating systemic change requires collaboration to build, scale, and sustain pathways to careers in classical music. Beyond early access, steps along the pathways include: intensive pre-college preparatory training; scholarships to leading summer programs and music schools, especially those with proximate orchestras willing to offer mentorship; access to concert tickets; mock-audition preparation; and, as greater numbers of BIPOC musicians graduate from college or conservatory, an expansion of early-career fellowship programs and substitute opportunities at orchestras. Systemic change would also require a large and long-term philanthropic investment in young musicians who hail from lower socio-economic backgrounds and cannot afford the considerable expense of such preparation. Given that training must commence at an early age, and continue for years thereafter, it may take a full generation to see significant and sustained impact. But that cannot be an excuse not to make more concerted efforts to improve the status quo. And, progress should be evident relatively quickly by intentionally tracking the career paths of BIPOC musicians who are already in conservatories and fellowship programs through such aggregators as the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP), a national arts data and research organization.

What would success look like? Anthony McGill’s own career path, described in the introduction to this chapter, is instructive. Other African-American and Latinx musicians have attained prominence, holding tenured positions at major American orchestras: Judy Dines, flutist with the Houston Symphony; Rafael Figueroa, Principal Cello, Metropolitan Opera Orchestra; Alexander Laing, Principal Clarinet, Phoenix Symphony; Demarre McGill, Principal Flute at the Seattle Symphony; Sonora Slocum, Principal Flute, Milwaukee Symphony; Weston Sprott, trombonist at the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra; and Titus Underwood, Principal Oboe, Nashville Symphony. Still others are making their way as soloists and chamber artists, among them flutist and composer Valerie Coleman, violinists Kelly Hall-Tompkins and Elena Urioste, composer-violinist Daniel Bernard Roumain, and cellists Gabriel Cabezas and Christine Lamprea. Many of these artists are also active teachers, mentors, and leaders in field conversations around DEI, justice, and racism. Music directors of American orchestras now include Giancarlo Guerrero (Nashville Symphony), Miguel Harth-Bedoya (Fort Worth Symphony), Michael Morgan (Oakland Symphony), Andres Orozco-Strada (Houston Symphony), Carlos Miguel Prieto (Louisiana Philharmonic), Thomas Wilkins (Omaha Symphony, outgoing), and, most prominently, Gustavo Dudamel (Los Angeles Philharmonic). But the fact that these musician leaders can still be named in a single paragraph speaks volumes about how far the field has to go.

Even if the career path of a musician of color does not end up at the New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera or comparable institution, one could nonetheless track some early indicators of success:

- retention in precollege programs;

- acceptance into music programs at institutions of higher education;

- numbers of applicants for auditions;

- numbers of fellowships and job placements; and

- setting of recruitment targets of racially diverse pools of applicants.

And while the primary goal of more intentional pathways training would be to increase the numbers of musicians onstage at American orchestras and other professional music institutions, success can take many forms. Secondary goals include building future audiences of diverse communities of adults who have received intensive exposure to music as children, and increasing the number of BIPOC musicians who might seek careers in arts administration or music education, or who might themselves become future patrons or board members of arts organizations. Intensive training and support from committed adult advocates also teaches skills of self-discipline and persistence in supportive environments, attributes that make young people highly attractive college candidates regardless of the major they eventually choose. Finally, there is a social benefit for all music students, regardless of race or economic status, in learning to perform as members of ensembles with a diverse group of peers.

There are some encouraging signs of progress. In December 2015, the League of American Orchestras and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation co-hosted a convening of administrative leaders in professional and youth orchestras, higher education, and community music schools, alongside a number of BIPOC artists. The meeting was designed to lay the groundwork for action to improve pathways for BIPOC musicians. Arising from those initial discussions, a number of interventions have commenced. These include:

- the National Alliance for Audition Support (NAAS), an unprecedented national collaboration administered by the Sphinx Organization in partnership with the New World Symphony and the League of American Orchestras, and with the financial support of nearly eighty orchestras. In its first two years NAAS has provided customized mentoring, audition preparation, audition previews, and travel support to more than nearly 150 artists, 24 of whom have won orchestral positions and another 12 substitute roles;

- collaborative “pathways” programs administered by arts organizations in Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Los Angeles, Nashville, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC;

- fellowships serving multiple musicians at the Cincinnati Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, LA Chamber Orchestra, Detroit Symphony, Houston Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, and Orpheus Chamber Orchestra among others;

- participation by some thirty-five orchestras in the League of American Orchestras’ Catalyst Fund, which provides support for orchestras committed to taking the time necessary to undertake comprehensive DEI assessment, training, and action to change organizational culture within their institutions;

- Intentional recruitment of BIPOC musicians at leading colleges and conservatories of music;

- Active involvement of union representatives from the American Federation of Musicians, the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians, and the Regional Orchestra Players Association at the annual conferences of Sphinx and the League of American Orchestras;

- Cultivation of Black and Latinx representation among C-Suite and other administrative leadership roles. Since 2018, Sphinx’s LEAD (Leaders in Excellence Arts and Diversity) has enrolled nineteen Black and Latinx administrative leaders, six of whom quickly attained promotion or senior level placement in performing arts institutions, where they can help effectuate change. A number of orchestras, including the Minnesota Orchestra, New Jersey, and New World Symphonies, serve as partners by hosting learning retreats and co-curating the curricular aspects of the program, while also creating direct networking and recruitment mechanisms.

- For orchestras or any other entity interested in gaining access to qualified musicians to engage, NAAS maintains a national network of sought-after Black and Latinx orchestral musicians, many of whom have experience working with orchestras of the highest level. And for ensembles wishing to broaden their programming, there are a number of databases, including: Music by Black Composers; Institute for Composer Diversity; Chamber Music America (2018); Harth-Bedoya and Jaime (2015); and CelloBello (2017).

But to what extent are our cultural institutions themselves willing to be more proactive? Mentorship programs work. What if every major orchestra committed to taking a group of talented early-career musicians under their wings? Would their boards, which are still predominantly white, endorse this financial obligation? How soon will the board makeups become more diverse and inclusive? Are musicians and their unions prepared to alter their collective bargaining agreements to reimagine the circumstances surrounding auditions, tenure, and promotion, to make the processes more transparent, objective, and inclusive of considerations beyond sublime artistry? To what extent do the internal cultures of classical music organizations allow for mistreatment to be acknowledged and acted upon? Are opera administrators willing to cast singers in leading roles, without regard to their race, as has been the case for many years in theater? And when will these artists be conducted or directed by people of color? What will it take for cultural organizations to commit to programming music by BIPOC composers outside of Black History month, Cinco de Mayo, and Chinese New Year celebrations, as well as commissioning BIPOC composers with regularity?

BIPOC musicians have other viable career options, including in popular music, and may find decades of hostile behavior increasingly difficult to overlook. Unless performing arts organizations first diversify onstage and through their programming of diverse repertoire, and commit to a more inclusive internal culture, it will be harder to attract BIPOC musicians to career and volunteer choices as administrators and board members than at other types of institutions with demonstrated commitments to DEI.

Intentionality matters. Take the example of the service organization Chamber Music America (CMA). In 2017, recognizing that African/Black, Latinx, Asian/South Asian, Arab/Middle Eastern, and Native American (ALAANA), women, and gender non-conforming composers had historically been under-represented in its Classical Commissioning Program, CMA altered the program’s goals. Through intentional recruitment and the panel review process CMA aimed going forward to award a majority of its grants to applicants who apply with ALAANA, women, and gender non-conforming composers. Within three years it had achieved the goal. Or consider the Cleveland Institute of Music. Each year it publicly shares a report card on its progress in improving diversity. From 2015 to 2020 it aggressively recruited BIPOC musicians and increased representation within the student body from 2% to 15%.

The challenges for improving pathways for BIPOC musicians remain formidable, and exponentially more so since the COVID-19 pandemic has halted in-person training and employment opportunities. But with the epidemic of racism also foregrounded in 2020, and with such strong unprecedented momentum among orchestras and educational institutions, the forward-facing efforts simply must continue unabated. To be effective, however, efforts will need to go well beyond the numerous well-intentioned statements of solidarity against racial injustice and in support of Black Lives Matter, which have flooded from arts and cultural institutions across the sector in the weeks since Floyd’s death. As the US population continues inexorably to become more diverse, the need for orchestras and other music institutions to overcome their own complacency, understand the extent of systemic racial inequities in the classical music field, acknowledge their complicity in past practices, and improve the stagnant participation rates of BIPOC musicians has become more than a generally recognized moral imperative. It is an existential crisis. Our cultural institutions simply must do so if they wish to survive, thrive, serve, and engage with their communities further into the twenty-first century.

References

Barone, Joshua. 2020. “Opera Can No Longer Ignore Its Race Problem”, The New York Times, 16 July, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/16/arts/music/opera-race-representation.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

Brodeur, Michael Andor. 2020. “That Sound You’re Hearing is Classical Music’s Long Overdue Reckoning with Racism”, The Washington Post, 16 July, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/that-sound-youre-hearing-is-classical-musics-long-overdue-reckoning-with-racism/2020/07/15/1b883e76-c49c-11ea-b037-f9711f89ee46_story.html

Chamber Music America. 2018. The Composers Equity Project. A Database of ALAANA, Women, and Gender Non-Conforming Composers, https://www.chamber-music.org/pdf/2018-Composers-Equity-Project.pdf

CelloBello. 2017. The Sphinx Catalog of Latin American Cello Works, https://www.cellobello.org/latin-american-cello-works/

Flagg, Aaron. 2020. “Anti-Black Discrimination in American Orchestras”, League of American Orchestras Symphony Magazine, Summer, pp. 30–37, https://americanorchestras.org/images/stories/symphony_magazine/summer_2020/Anti-Black-Discrimination-in-American-Orchestras.pdf

Harth-Bedoya, Miguel, and Andrés F. Jaime. 2015. Latin Orchestral Music: An Online Catalog, http://www.latinorchestralmusic.com/

Institute for Composer Diversity (ICD), https://www.composerdiversity.com/

League of American Orchestras, with Nick Rabkin and Monica Hairston O’Connell. 2016. Forty Years of Fellowships: A Study of Orchestras’ Efforts to Include African American and Latino Musicians (New York: League of American Orchestras), https://www.issuelab.org/resources/25841/25841.pdf

McQueen, Garrett. 2020. “The Power (and Complicity) of Classical Music”, Classical MPR, 5 June, https://www.classicalmpr.org/story/2020/06/05/the-power-and-complicity-of-classical-music

Music by Black Composers (MBC). Living Composers Directory, https://www.musicbyblackcomposers.org/resources/living-composers-directory/

Tommasini, Anthony. 2020. “To Make Orchestras More Diverse, End Blind Auditions”, The New York Times, 16 July, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/16/arts/music/blind-auditions-orchestras-race.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

1 The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this chapter belong solely to the author, and not to the author’s employer, organization, committee, or other group or individual. The author wishes to express appreciation to Liz S. Alsina, Afa S. Dworkin, Dr. Aaron Flagg, and Jesse Rosen for their input into various versions of this chapter.

2 For purposes of convenience, this paper will henceforth refer to people of color collectively using the acronym BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color), but will focus on Black and Latinx people.

3 As just one marker, books on race comprised eight of the top ten nonfiction books on the 19 July 2020 The New York Times Book Review. Articles pertinent to racism and concert music include Brodeur (2020), Tommasini (2020), and Flagg (2020).

4 This is not to say that opera fares significantly better. While some singers of color have achieved the highest levels of success onstage in so-called “color-blind” casting, creative teams, administrators, and board members remain overwhelmingly white (Barone, 2020). Barone’s Times article links to a gut-wrenching conversation among six leading American Black opera singers: https://www.facebook.com/LAOpera/videos/396366341279710

5 These include the Sphinx Organization (founded in 1996), Boston’s Project Step (founded by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1982), the Music Advancement Program at The Juilliard School (1991), and the Atlanta Symphony’s Talent Development Program (1994).

6 Among them are the Gateways Music Festival (1993), a biennial gathering of professional musicians of African descent now held in collaboration with the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY; Sphinx’s Symphony Orchestra (1998) and Virtuosi (2008); the Harlem Chamber Players (2008); the Black Pearl Chamber Orchestra (2008); the Colour of Music Festival (2013); and, in the UK, Chineke! Orchestra (2015).