12. New or Improved? American Photography and Patents ca. 1840s to 1860s

© 2021 Shannon Perich, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0247.12

Fig. 1 Howland Brothers, United States Patent Office, Washington (1840), engraving included in Titian Ramsay Peale Album, Washington, DC, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Photographic History Collection, catalog number PG.66.25A.24, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800&id=NMAH-ET2017-14021-000001.1

Photography was not, and is not, the brainchild of one person. It emerged after curious and persistent individuals tinkering with known facts about chemistry and optics — alongside new discoveries — were able to stabilize images created by rays of light on sensitized surfaces. In the nineteenth century, individuals endeavoring to produce processes we now describe as photographic were dependent on combinations of chemical, scientific, and manufacturing achievements; some of these were common practice, some were shared without patent infringements, and some patents were held tightly with hopes of financial renumeration. As such, the medium of photography, before an image is even produced, is shaped by a variety of factors, including whether certain aspects of the apparatus and processes are controlled by patent claims.

Although most histories of photography hold 1839 as a benchmark year owing to Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s demonstration of the daguerreotype process, successful and not-so-successful experiments had been produced and shared privately and publicly prior to that date, as would be the case for several subsequent photographic processes. In late 1839, the naturalist Hercule Florence, a Frenchman working in Brazil, posted a press release in a São Paulo newspaper, A Phenix, in response to the announcement of Daguerre’s process. Asserting that he had been making paper-based photographs for nine years as a means to print and distribute his work, he nevertheless wrote, ‘I will not dispute anyone’s discoveries, because one same idea can come to two persons and because I always considered my findings precarious’.2

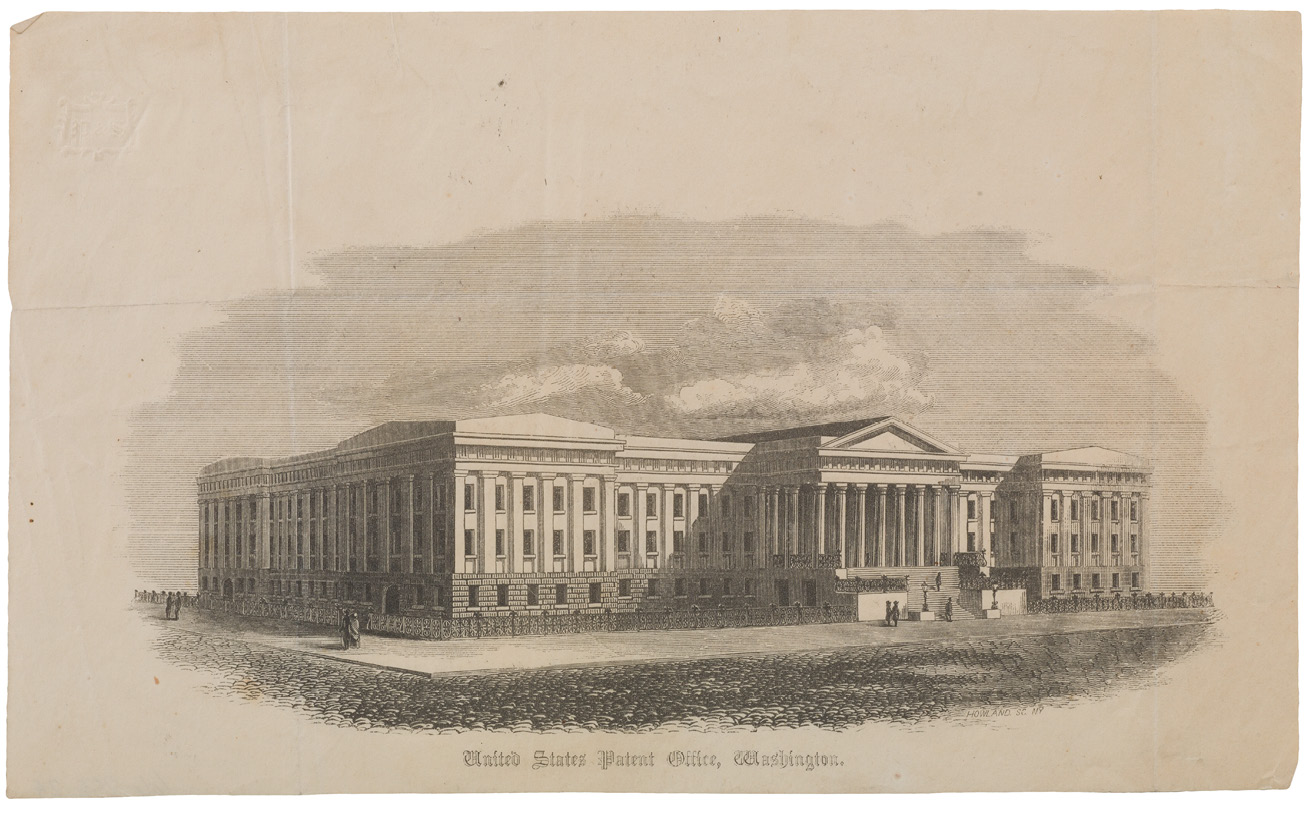

Meanwhile, the international rivalry between France’s Daguerre (see Figure 3) and the United Kingdom’s William Henry Fox Talbot (see Figure 4), who both claimed to be the first inventor of a photographic process, is storied and well-documented.3 One of the ways in which primacy and legitimacy were debated, and perceived as validated, was through the receipt of patents. For Daguerre, retaining the patent to the photographic equipment offered him the possibility of additional financial benefits and international recognition. Daguerre’s agent was awarded a patent in the UK for his process. The terms for licenses were restrictive, thus becoming the first example in the history of photography in which a patent prevented the production of a certain type of photography to thrive because of scientific and international competition.4 Talbot, was not issued a patent until 1841 and spent years chasing perceived patent infringements. His own process, once patented, also restricted who could use his patent and thereby potentially hindered the development of photography as a process and business. Across the Atlantic in the United States, patents would play their own role in shaping early American photography.

This chapter explores a group of photographic processes and patent claims in the US, beginning with the calotype in the 1840s. It then turns to examine ambrotypes in the 1850s, ending with the tintype in the 1860s. The early history of photography, especially from 1839 and through 1865, is significantly shaped by the materiality of the medium. Contemporary written histories of early photography privilege art historical pedagogies, without fully acknowledging how processes and practices — which created historical photographs as images and objects — were shaped by patents. Patent application approvals were made based on government-imposed processes and policies, patent examiner decisions, the nascent state of the photography as a medium, and individual decisions about whether to apply for or claim patent rights. The resulting processes and materials that were used to create, form, and hold photographic images embody a host of underpinning histories that might shape how we understand photographic possibility, creativity, and control.

As Karen Lemmey’s chapter in this volume points out, not all arts and artists benefited equally from the award of patents. The usefulness of a patent may vary depending on the creative endeavor and legal effectiveness of the patent. In the emerging field of photography, shrewd business skills, scientific knowledge, and technological abilities were more important than artistic prowess. Patents afforded some photographers a level of prestige, serving as a stamp of legitimacy from which they could benefit financially through improved reputation. This resulted in more studio sales, the licensing of the patent rights, and maintaining control over a line of products. However, the road to acquiring a photography-related patent and reaping its benefits was neither straightforward nor always beneficial.

The Smithsonian Institution, the Patent Office and Innovation History

The history of the Smithsonian Institution (SI) and the United States Patent Office (USPO) are intertwined as federal government agencies and collectors of knowledge. The Patent Act of 1836 established the USPO as a standalone agency with a Commissioner, afforded grantees fourteen years of protection with the possibility of an extension of seven years, insisted copies of patents would be made available through libraries to improve the quality of the patent applications, allowed foreigners to file, and began a renumbering system starting with the number ‘1’. As a submission requirement, the applicant included a model of the patent so the examiner might better understand the proposed invention and prove its utility or improvement upon an existing patent.5

The Smithsonian Institution, founded in 1846, is now a repository for many historical patent models that provides researchers with opportunities to see physical manifestations of designs, apparatuses, and processes to complement the written portion of a patent application. As early as 1858, Smithsonian curators selected some patent models to become part of the Smithsonian’s collection.6 The keeping of USPO history, along with selected artifacts and documents held at the USPO, uniquely documents the shaping of national culture, federal policy, and intellectual endeavors.7 Studying the patent model collection reveals that not all patents granted were viable or unique products or processes.

Today, of the 810 photography patents issued by the USPO between 1840 and 1880, the patent models for some 230 photography-related patents now reside in the Photographic History Collection (PHC) at the NMAH.8

The Patents

The first patent issued by the USPO for photographic apparatus went to Alexander Walcott on 8 May 1840: patent number 1582, awarded for his camera using a concave reflector (see Figure 2). However, it would be several years before there was an abundance of applications for photography apparatus and processes. From 1840 to 1854, there were between one and six photography patents per year. In 1844, 1845, and 1848, there were none. The awarded patents were for improvements in daguerreotype apparatus for preparing and developing plates, as well as adding color to enliven photographs. 1847 marks the beginning of patents for non-daguerreotype photography.9 This modest number of patents belies the number of innovations, published and unpublished common practices, and experimentation that took place during that period. However, the patent model collection helps us understand how photographers, case makers, doctors, dentists, opticians, machinists, cabinet makers, painters and colorists, framers, and many others understood how they might contribute to, benefit from, and imagine an impact on the visual culture of their era.

Fig. 2 Alexander Walcott patent model camera (1840) and photographer John Paul Caponigro’s iPhone (about 2009), catalog numbers PG.000697 and 2012.0049.13, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800 &id=NMAH-ET2012-14187.

Fig. 3 Meade Brothers, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1848), daguerreotype, catalog number PG.000953, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800&id=NMAH-2009-10914-000001.

Fig. 4 John Moffat, William Henry Fox Talbot (1864), carte-de-visite, catalog number PG.000227, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800 &id=NMAH-AHB2020q046154.

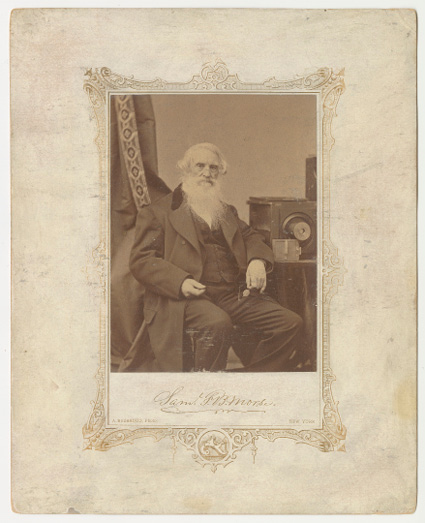

Among the multi-disciplinary personalities that engaged with photography was the inventor of the telegraph key, Samuel F. B. Morse (see Figure 5). While in Paris demonstrating his own invention, he met with Daguerre and famously wrote about the meeting in a published letter. Morse’s brother, Sidney Morse, published it in the New York Observer. It was there, on 20 April 1839, that Americans first learned about the daguerreotype.10 Morse ends the letter indicating that ‘the French Government did act most generously toward Daguerre’.11 With support from François Arago at the French National Academy of Sciences, Daguerre surrendered the rights to his process, in which a highly polished silver plate is sensitized with bromine and exposed in camera, to the French government in exchange for an annuity. Morse’s note about the French government’s involvement gave photography legitimacy. In the US, scientists, dentists, professors, tinkerers and others did not wait for instructions, demonstrations or licenses to arrive before beginning their own experiments and making photographs12

The hubris that some American innovators held regarding the work of others was not necessarily attributed solely to individual curiosity or disdain for European inventions. In his essay, ‘Patent Models: Symbols of an Era’, historian Robert C. Post, describes ‘Yankee Ingenuity’, a phenomenon of American national pride that spurred entrepreneurial and technological innovation.13 In early 1833, Morse writes to the American author James Fenimore Cooper about the state of art and science in the US and notes that ‘[i]mprovement is all the rage’.14 Demonstrating this himself, Morse brought a daguerreotype lens with him when he returned from France in 1839. There were no camera manufacturers yet, so he hired a cabinet maker to construct the body of the camera (see Figure 6). Morse exemplified the American attitude around invention and innovation to just ‘go ahead’ and do it.15 In fact, ‘doing things better’ or making ‘improvements’ was a sufficient standard for the award of new patents granted by the US government. Between 1836 and 1880, the Patent Office described the threshold for award as ‘novelty, originality, and utility’.16 However, as the following examples demonstrate, these terms were not clearly defined or evenly applied, resulting in the granting of patents that caused confusion and anger among photographers, and shaped photographic products. In some cases, rights to photographic processes stifled or perpetuated the making and introduction of some types of photographs. Some patents incorporated or were aligned with existing patents. And still in other cases, crafty language and slightly altered approaches allowed for creative work arounds.

Fig. 5 Abraham Bogardus, Samuel F. B. Morse (1871), mounted photograph on cardstock, catalog number PG.000006. Note, Morse is depicted with the camera (turned on its side) seen in Fig. 6, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800&id=NMAH-AHB2020q046158.

Fig. 6 George W. Prosch, Morse’s Daguerreotype Camera (1839), catalog number PG.000004, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800&id=NMAH-2003-36149.

The Calotype in America

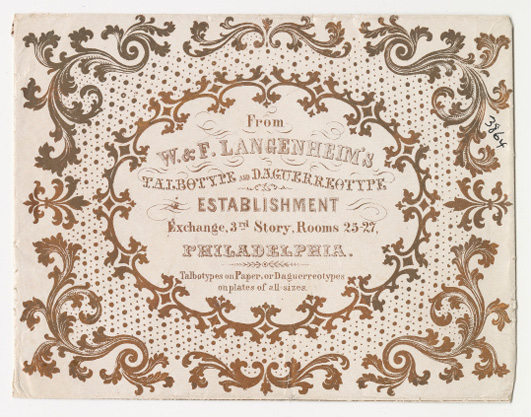

Brothers William and Frederick Langenheim, German immigrants working and living in Philadelphia, experimented in photography by exploring processes and various business models from the 1840s until their deaths in the 1870s. Their enthusiasm was evident in their advertising texts, but also in the way they succeeded in producing quality daguerreotypes while investing in emerging paper processes and inventing their own forms of photography. As such, they highlight the trial and error that was needed to find commercial success and the ways in which patents might have worked against them.

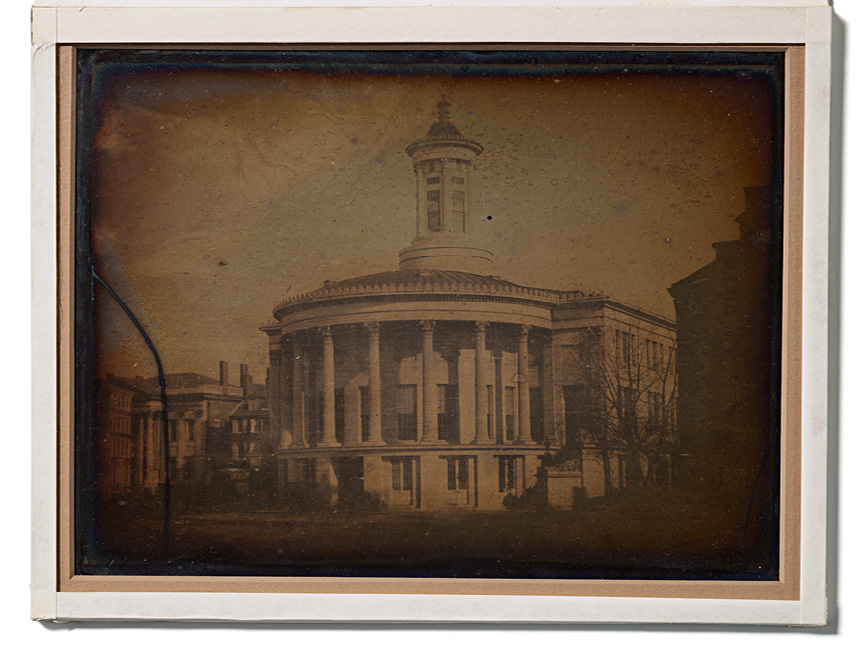

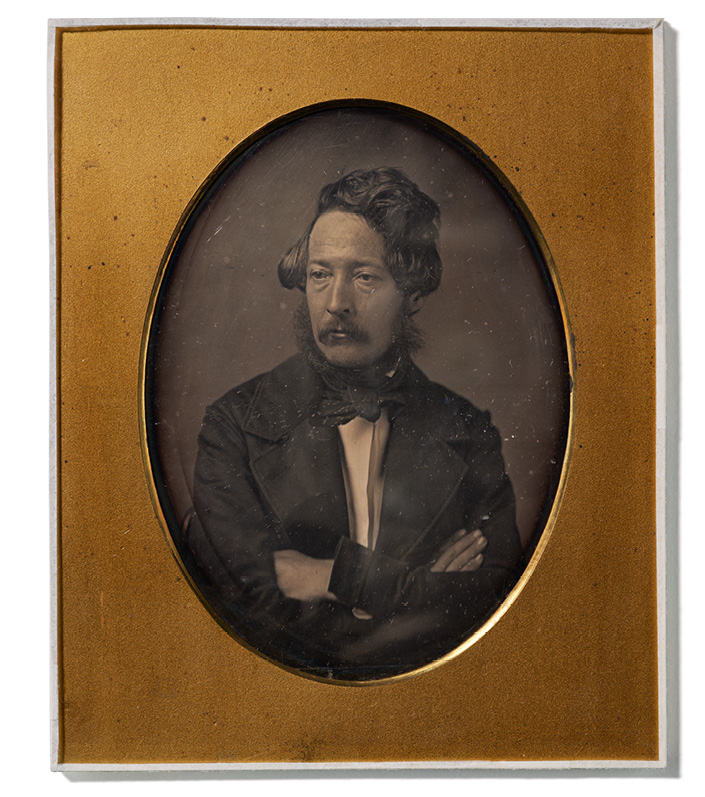

The Langenheims began their lives in the United States as journalists for a German-language newspaper, Die Alte und Neue Welt. They began experimenting, and quickly perfecting, the daguerreotype process in 1842, opening a studio in the Merchants’ Exchange Building (see Figure 7).17 William (see Figure 8) oversaw the business while Frederick (see Figure 9) was the primary image-maker. In his article ‘Prospects of Enterprise: The Calotype Venture of the Langenheim Brothers’, David R. Hanlon notes that the brothers earned an average of about $95 a week in late summer to early fall 1844. Following an aggressive advertising campaign, they increased earnings to $232 a week from 1 May to 7 June 1845. In 1845, Frederick opened a studio in New York City with Alexander Beckers.18

Fig. 7 Walter Johnson, Philadelphia Exchange (1840), daguerreotype, catalog number PG.000167, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800 &id=NMAH-JN2020-00034-000001.

Fig. 8 Frederick Langenheim, William Langenheim (1840s), calotype, catalog number PG.003864.12, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800 &id=NMAH-JN2020-00037-000001.

Fig. 9 Unidentified maker, Frederick Langenheim (1840s), daguerreotype, catalog number PG.000203, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?max=800 &id=NMAH-JN2020-00037-000001.

Frederick Langenheim and Beckers began garnering individual patents. Between 1849 and 1877, Beckers would be granted eleven patents, including a block to hold daguerreotype plates while polishing them and an improvement in stereoscopes. Langenheim would be granted three patents, including one for pictures on glass. In 1850, he invented the hyalotype, a transparent positive on an albumen-coated piece of glass (see Figure 10).19 While the hyalotype was somewhat successful when made on a larger piece of glass for store window decorations, it was extremely short-lived as a viable commercial medium, as collodion on glass would prove to be a somewhat more practical process.20 Note that Langenheim’s patent model depicts the very building in which the patent examiner reviewing his application would have been sitting.

Fig. 10 Frederick Langenheim, Photographic Pictures on glass, patent number 7754 (19 November 1850), wooden frame with attached Patent Office tag and albumen photograph on glass, catalog number PG.000887, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1022700.

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s in the United States, the daguerreotype was deeply entrenched as the favored form of photography. In the UK, William Henry Fox Talbot was busy clamoring for recognition and renumeration with his paper-based photography, the Talbotype, or calotype.21 His efforts in the UK to litigate were often perceived as wasteful, excessive, and too far-reaching. An article from the London Art Journal wryly critiqued his approach: ‘he appears to imagine [he] secures to himself a complete monopoly of the sunshine’. The article complains that as a man of wealth Talbot ‘can play with the law’, and feels free to assert claims that were actually ‘the discoveries of earlier laborers than himself’ in an effort to protect what he perceived within his patent rights.22 The question as to how far Talbot’s rights extended would be settled when he lost an 1854 lawsuit, Talbot v. Laroche. The verdict did not dismiss his claim to the rights as inventor of the calotype patent; but it did find that Laroche had not infringed on Talbot’s right, thereby confirming other photographers had the right to use collodion processes.23

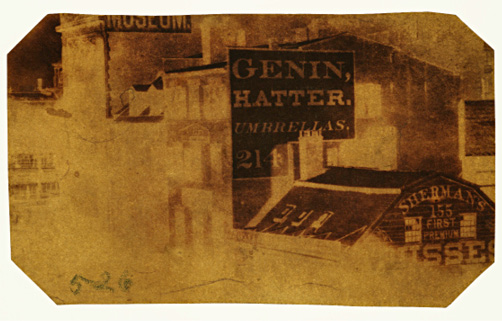

In 1845, William Langenheim may have seen some of Talbot’s calotypes from The Pencil of Nature (considered the first book with photographic illustrations and published in installments between 1844 and 1846) as they circulated in Philadelphia, as well as examples of a paper process by a Mr. Tilghman, that in turn, inspired Frederick to experiment. As early as 1844, the brothers advertised that their studio carried chemical supplies to produce calotypes, should customers desire them.24 As newspaper men, it must have occurred to the Langenheims that images produced on paper could be less expensive to make, purchase, and distribute. Having multiple copies could be appealing for customers, and paper photography produced in numbers would not require bulky cases. With his New York partner, Beckers, Langenheim experimented with waxed paper negatives from their studio window to make some of the first paper photography views of Manhattan in 1848 (see Figure 11). The studio was in close proximity to Phineas T. Barnum’s American Museum, and just two doors away from Mathew Brady’s and Edward Anthony’s respective businesses at 205 and 207 Broadway.25

Fig. 11 Frederick Langenheim and Alexander Beckers, Buildings on the East Side of Broadway (1848–1849), waxed paper negative, catalog number PG.000526, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1399434.

Edward Anthony, an American photographic materials supplier and well-established member of the photographic community in New York City, spent nearly a year beginning in 1846 negotiating with Talbot, trying to buy the patent rights for the United States.26 Meanwhile, Talbot was granted patent number 5171 by the USPO on June 26, 1847, the only photographic patent for that year (see Figure 12).27 Anthony, still eager to be at the vanguard of a new wave of paper-based photography, persisted, inquiring about acting as Talbot’s agent for the ‘sale of licenses, Talbotype views’, and more. Talbot declined.28 Hanlon makes the case that Talbot, whose litigation efforts in the UK centered around attempts to recover his financial investments, missed an opportunity with Anthony as one of the most successful and savvy photography suppliers in the United States. William Welling in, Photography In America: The Formative Years, 1839–1900, asserts that in 1847, American photographers had little interest in paper negatives, suggesting that even if Anthony, a supplier to most photographers had garnered the Talbot calotype license, it might have been a wasted effort.

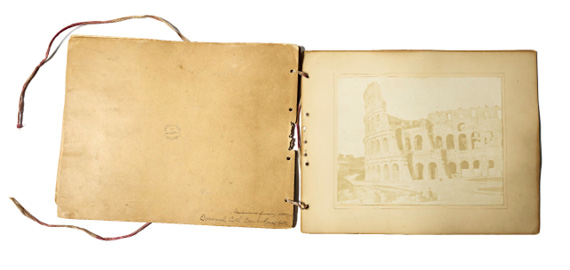

Fig. 12 William Henry Fox Talbot, Patent 5171 for Improvement in Photographic Pictures (26 June 1847), calotype catalog number PG.000890. Note the stamp on left, https://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=PG.000890.

Fig. 13 William and Frederick Langenheim, Envelope (1849), catalog number PG.003864.33, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1971477?q=PG.003864.33&record=1&hlterm=PG.003864.33.

The forward-looking Langenheim brothers were also eager to strike a deal with Talbot for the US rights to the calotype process. They configured several offers and suggested financial arrangements beginning in February 1849. One proposal included selling licenses to individuals in the range of $50-$100 and retaining a twenty-five percent commission. They claimed:

We know that a great many of the numerous Daguerreotype operators here would embrace your art with the enthusiasm of true Yankees if they could learn the art in a short time to a reasonable degree of perfection and if the expense for tuition and the right to exercise it was moderate.29

William went to Lacock Abbey, Talbot’s home near Bath, England, to negotiate with Talbot while Frederick stayed in the US to promote and build excitement for the new process in which they were about to be heavily invested. In May 1849, for a sum of 1,000 pounds sterling ($6000), Talbot sold them the US rights (see Figure 13). With at least 150 daguerreotypists in the United States, if they sold sixty licenses, they would be able to cover the biannual payments of £200.30 However, by September they had not sold a single license. They worked hard and advertised widely, as they always had, banking in part on their reputations as well-respected gentlemen, deeply knowledgeable photographers, and savvy businessmen. Unfortunately, the Langenheims’ calotype endeavor failed. They attempted to use profits from their daguerreotype business to pay the debt to Talbot, but it was not enough. By the end of 1851, the brothers dissolved their business. Hanlon cites a number of reasons why the calotype failed at that particular moment in the United States, including bad timing as the US was just coming out of a war with Mexico, and a number of urban areas were struggling with a cholera epidemic. But perhaps most pointedly, ‘studio owners were not interested in paying to use an unproven process, especially when the populace continued to endorse a method [the daguerreotype] that had no patent restrictions’.31 Despite the fact that the Langenheim brothers anticipated the rise of paper-based photography and could see its popularity in Europe, there was no incentive to move to a process that was less detailed and more restricted than the daguerreotype. Even with their expertise in the field, they did not see clearly how committed photographers and consumers were to daguerreotypes.32

The brothers were not alone in their frustration about the state of photography being held back by patents, especially when some patent claims were perceived as questionable. In 1852, the author of an article entitled ‘Photography-Its Origin, Progress, and Present State’ complained about the quality of evaluation of Talbot’s patents, noting: ‘Several of these patents would never have been granted had there been a scientific board to examine the merits of them and test their originality’.33 Others shared his concern for how patents were issued without thorough research from patent examiners.

While one might think that a government issued patent would come with a certain level of scrutiny, in fact in the United States, that very process was muddied by USPO itself. US patent examiners were given the daunting task of deciding which patent applications offered utility and novelty, though applications did not have to demonstrate both. The attitude among the examiners at the USPO towards innovation was cultural and political. In her introduction to The Early American Daguerreotype: Cross-currents in Art and Technology, Sarah Kate Gillespie argues that ‘[i]n the middle of the nineteenth century, the idea that certain knowledge would become accessible only to the specialized few went against American ideals’.34 Welling writes, ‘It appears that the thought of using collodion for photography may have occurred to a number of people at the same time’.35 Taken together, Gillespie and Welling describe the gap between intellectual generosity and a cultural propensity described earlier as ‘Yankee Ingenuity’ that perhaps shaped risk assessment when deciding whether to infringe upon patent rights. We can see this in the controversies surrounding the ambrotype patents awarded to James Ambrose Cutting.

Two key processes that spurred photography were shared freely by their creators. Sir John Hershel and Frederick Scott Archer shared or published key formulas without financial compensation or stated protection of those ideas. Sir John Hershel shared the benefits of sodium thiosulfate, or hypo, which halts the reaction of light on silver halides that ensured the success of Daguerre’s and Talbot’s processes.36 Frederick Scott Archer published his recipe for collodion in 1850, then, more widely with some improvement of the formula, as a manual in 1854.37

Archer’s collodion process, in which gun-cotton is dissolved in ether with additional silver nitrate to make a clear sticky substance that is spread on to a variety of substrates, became a base recipe in which photographers could experiment and adapt as they saw fit.38 Archer did not patent his process. By openly publishing the recipe, it was widely adapted with modifications and sometimes by others who then patented an ‘improvement’. Sadly, Archer died penniless while others financially profited from his generosity.

Two of these collodion-based processes would take different trajectories because one restricted the actions of photographers and the other restricted the actions of manufacturers. The ambrotype required makers to create a hand-coated, photographic negative made by following a light-sensitive collodion recipe that was then assembled with other elements to complete the presentation of the photograph. The ambrotype was debated and contested for fourteen years in part because individual photographers were singled out for infringement of the process. Mass manufactured tintype plates, in which the light-sensitive emulsion was applied at the factory, relieved photographers from possible infringements. The patent was for the manufacture of the tintype plate and there were no restrictions that prevented a photographer from making his own tintype plates if they wished. In the case of ambrotypes, patents associated with the process would create significant confusion and frustration. Even as they rejected calotypes, photographers’ insistence on producing ambrotypes despite the challenges were explained in part by a reminiscence by A. R. Gould: ‘…how we hailed with joy the advent of the ambrotype as a Godsend to relieve us from the fumes of mercury and bromine [while making daguerreotypes]…’. A less chemically toxic environment, in addition to a quicker and less expensive process, was appealing. Gould went on to say that tintypes were even better: ‘…but excellence and beauty were easier reached when the ferrotype [tintype] plate was found in our sanctum’.39 Not only were tintypes rapidly adopted; they also inspired additional successful patents that applied to manufacturers rather than to individual photographers.

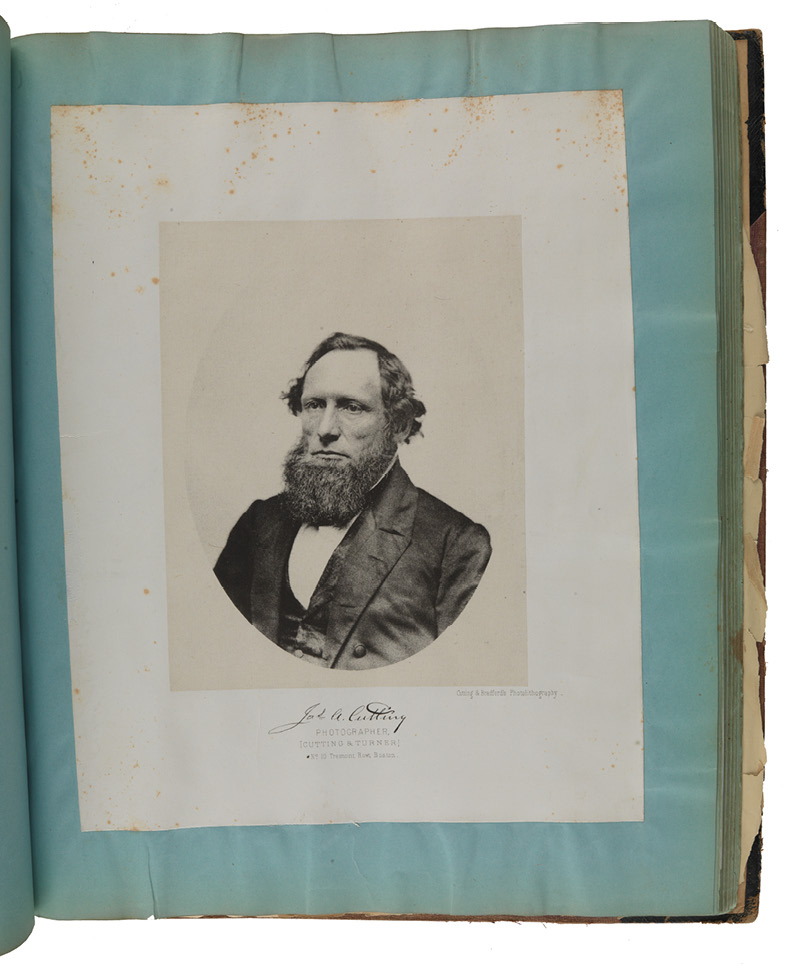

The Ambrotype

An ambrotype is a unique cased image in which a photographic negative on glass is backed by a dark cloth, varnish, or paper (see Figure 14) to make it appear as a positive image (see Figure 15).40 The contest between ambrotype patentee Cutting and patent examiner Titian Ramsay Peale, illuminates how Cutting’s patents were awarded with an eye toward bureaucracy rather than integrity, and how those faulty patents shaped the business of photography for specific photographers (see Figure 16).

Cutting was awarded three ambrotype related patents on 11 July 1854 (patents 11213, 11266, 11267), two of which caused controversy for the photographic community from 1854 to 1868. The first was for the addition of camphor to collodion. While qualifying as ‘novel’, it had no actual utility; therefore, although it was awarded, the patent was worthless. The second patent was for the use of balsam of fir, a common adhesive of the era, to secure a second piece of glass to the image side of a negative.41 The third patent was for Cutting’s formula for collodion, in which bromide was added to decrease exposure time, making portraiture on glass more viable.

Fig. 14 Unidentified maker (possibly Mathew Brady), Negative of Unidentified sitters, late 1850s to early 1860s, ambrotype, catalog number PG.75.17.892, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1971422.

Fig. 15 Unidentified maker (possibly Mathew Brady), Positive of Unidentified sitters, late 1850s to early 1860s, ambrotype, catalog number PG.75.17.892, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1971422.

Fig. 16 Cutting and Bradford, James Ambrose Cutting (about 1858), photolithograph, included in Peale’s album, catalog number PG.66.21.55, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1403396?q=PG.66.21.55&record=1&hlterm=PG.66.21.55.

Cutting had a practice of acquiring patents, then selling them. Prior to his photographic patents, Cutting had experience with the patent application process, and was awarded a patent for a new kind of beehive that he sold in the 1830s. Later, in the 1840s, he patented railroad switches and sold those patents as well.42 When he applied for the three ambrotype patents, it was during a period in which the Patent Office Commissioner often awarded patent claims with more leniency than previous administrations.43 The late stages of a patent application review might ask for clarification, a partial rejection that allowed the applicant to revise, or an outright rejection with the possibility of appealing to the Commissioner. During the review of Cutting’s patent assignment request, one of his applications needed only to add the words ‘for photography’ to be accepted as novel. However, the other two were initially rejected for their lack of originality by patent examiner Titian Ramsay Peale. Despite Peale’s rejection based on his research and strong understanding of common photographic image production practices, Commissioner Charles Mason approved the patents under a questionable presumption that more patent awards ensured the United States appeared as innovative and productive, thus making Cutting’s weak patent claims legally binding.44

In her doctoral dissertation and in the exhibition catalogue Paper Promises, photography historian and curator Mazie Harris illuminates the patent request process, particularly as it relates to Peale.45 Peale, known as stringent and tough, often annoyed commissioners, solicitors, potential patentees, and his own fellow examiners when he double-checked their approvals. Peale refused bribes and wrote long responses to submissions. Harris notes that Peale’s rejection letters often provided detailed and specific references to period literature from a wide range of subjects.46

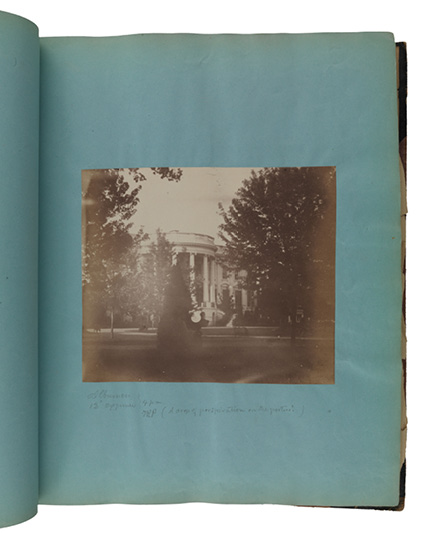

Peale rejected Cutting’s applications with an abundance of proof and an exchange of letters asserting that his patent submissions were derivatives of common and previously published processes. Peale had deep knowledge in the field and was an amateur photographer who tested photographic formulas and processes. He kept records of his experiments, associated with practicing photographers, and came from a long line of erudite, patriotic artists all of which rounded out his breadth of knowledge and experience (see Figures 17 and 18).47

Fig. 17 John Wood, The US Capitol Under Construction (July 1860), salted paper print, included in Peale’s album, catalog number PG.66.21.58, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1403399.

Fig. 18 Titian Ramsay Peale, White House Portico, Albumen, 12’ exposure 4pm TRP (A drop of perspiration on the portico!) (1850s) salted paper print, included in included in Peale’s album, catalog number PG.66.21.23, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1403377?q=number+PG+66.21.23&record=1&hlterm=number%2BPG%2B66.21.23.

Peale and other photographers had been adding bromide or bromine to photo sensitive surfaces since the Daguerreian era to speed exposure time. Cutting’s bromide-related patent, however, created a situation in which any practitioner adding bromide to his collodion — as was common practice — might suddenly find himself infringing on Cutting’s patent.

In 1854, many photographers were incensed that Cutting’s patent had been approved. Humphrey’s Journal declared, ‘As regards the claim of Bromide of Potassium, it is wholly worthless, having been published and used long before Mr. Cutting’s application was filed’.48 Photographer and photography manual publisher Marcus Aurelius Root, who gave the name ‘ambrotype’ to the process and format, initially supported Cutting, but after conducting his own patent research at the USPO he withdrew his support.49

To further complicate the landscape, in addition to selling individual licenses himself, Cutting sold shares of the patent to individuals who could then set their own licensing fees and pursue patent infringement lawsuits. Acquiring a portion of Cutting’s shares of the patents required a hefty sum. In 1868, lawyers from Howson & Son went to court to seek an annulment of the Cutting ambrotype patent and prevent its renewal. At that time, it was revealed how much Cutting had made from selling shares of the patent. In the Arguments Before the US Patent Office and Justices of the Supreme Court (the validity of awarded patents could be brought to federal court for resolution) it was reported that Jesse Briggs paid $10,000 to Cutting for the right to license Cutting’s process, and Asa Millet paid $1,100 for the same rights in Maine and New Hampshire. Some rights holders were reported to have paid up to $20,000.50 William A. Tomlinson purchased rights to license the process in New York, a potentially lucrative locale with a high concentration of photographers, manufacturers, and supply distributers. The high sums paid gave some a grand sense of control over the ambrotype process. Tomlinson took Virginia photographer M. P. Simons to court for using the word ‘ambrotype’ in his advertisements. A US District Court judge did not issue an injunction and explained to Tomlinson that the name of the process and format, even if included in the patent, was not an infringement; the judge added that Tomlinson needed to learn the definition of trademark.51

With an improved understanding of the patent and how it might be held up in court, Tomlinson targeted New York City photographer Abraham Bogardus in 1858.52 Bogardus had enough evidence to go to court to fight the patent, but he opted to settle out of court and pay the $100 licensing fee to make ambrotypes, instead of losing business during the height of the photography season. He later regretted the decision, as did others, since by default, Tomlinson was considered to have won the case thus making it possible to sue other photographers.53 The outcome was wide-reaching and benefitted Cutting and his assignees, as most published formulas contained bromide; furthermore, it seemed that he could expand the legal scope of patent infringement beyond photographers to include manufacturers.54 This left photographers with one of four options. They could choose not to make ambrotypes, thus avoiding the issue altogether. They could take the risk of making ambrotypes and hope not to be sued; this choice may explain, in part, why so many ambrotypes are not stamped with a specific maker’s name. Photographers could purchase the license because they believed it was the right thing to do, or they could purchase the license even if they disagreed with the principle, because it was the financially expedient choice. Well-known photographers who had been holding out, such as Mathew Brady and Jeremiah Gurney, recognized they would be legal targets like Bogardus and therefore paid for the license, even though they believed it to be a poorly awarded patent.55

Charles D. Fredericks, another New York City photographer, was itching to take Tomlinson to court to debunk the patents; he was scheduled for a hearing on 18 May 1859.56 Tomlinson delayed the court date, indicating that he needed more time to gather evidence. Photographers and photography journal editors gathered and began building a defense fund to support Fredericks’ legal battle. But after a year and a half, only about $750 of the $5,000 needed had been raised, according to treasurer Edward Anthony. Some photographers did not contribute to the campaign as they felt that only those photographers of sufficient means could afford the license, therefore those making only a modest income from ambrotypes might be priced out of the market. The lawsuit was delayed during the Civil War, leaving photographers in possible legal limbo for five years.57

By March 1865, just before the end of the war, Cutting signed all but one-eighth of his rights over to his lawyer, WEP Smyth, and to a former Daguerreian named Timothy Hubbard. They both believed that if they pursued infringements that occurred during the war years, it would be lucrative. Their threat of lawsuits and efforts to chase several years’ worth of retroactive compensation put a number of rural New England photographers out of business. The lawsuit between Tomlinson and Fredricks that had been on hold during the war was settled for $900, leading the way for others to do the same, including manufacturers. ‘It is very humiliating to acknowledge defeat, but it may be better than to fight when there is no chance of success’, wrote Charles Seely in The American Journal of Photography.58 After a meeting to restart the unified resistance that had existed before the Civil War, he lamented, ‘half our army has gone to the enemy… the proprietors of the patents have so perfected their plans that they consider their position impregnable’.59 Despite legal threats by Tomlinson, and other rights holders, only one case went to court. The judgment was in favor of the ambrotype patent holders, and ruled against Maine photographer Enoch H. McKinney in August 1867.60

When it was learned that Smyth and Hubbard were going to attempt to renew the patents for another seven years, Edward L. Wilson, founder, editor and publisher of the Philadelphia Photographer, led the charge to prevent the renewal of Cuttings’ patents. A three-month process with Philadelphia lawyers Furman Sheppard and Henry Howson, from Howson & Son, included seventeen witnesses and a preponderance of evidence thanks to a Detroit photographer who retained a trove of American and European journals and books, each marked with pages that showed the use of collodion with bromides before 1853. The Acting Commissioner A. M. Stout denied the extension and pronounced the patent dead one day before it was due to expire on 11 July 1868.61 The legal victory was anticlimactic for the photography community after much money, time, and debate had been invested. The ambrotype process was rapidly waning commercially in favor of other types of photography, such as the tintype and carte-de-visite. These latter forms of photography were faster, less expensive, and physically lighter; they could also be placed in albums and collected. Cartes-de-visite were mounted paper prints made in multiples from glass plate negatives. Tintypes could be made outside of the studio, offering new types of images and targeting a wider consumer market.

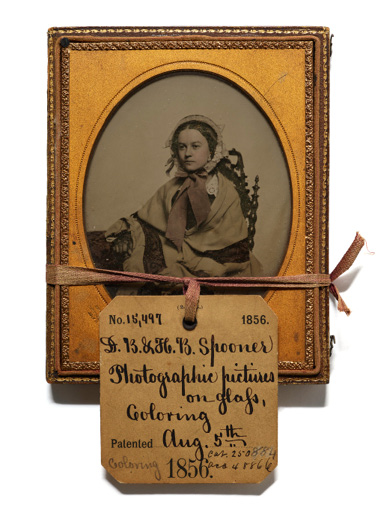

While the ambrotype patent shares and licenses may have been lucrative for a few holders, others piggybacked on existing patents including those secured by the Spooner Brothers of Springfield, Massachusetts. They were awarded a patent for adding color to ambrotypes (see Figure 19). The Spooner Brothers noted the Cutting’s license on the ambrotype of their own patent submission to the USPO (see Figure 20). Note how the girl’s bow and the tablecloth are subtly tinted red in a modest and tasteful style.

Fig. 19 Spooner Brothers, Patent model for 15497 for Photographic Pictures on Glass, Coloring (5 August 1856), ambrotype, catalog number PG.000817, http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=PG.000817.

Fig. 20 Spooner Brothers, Patent model for number 15497, Detail of Cutting patent notification (5 August 1856), brass mat over ambrotype glass plate negative, catalog number PG.000817, http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=PG.000817.

Tintypes

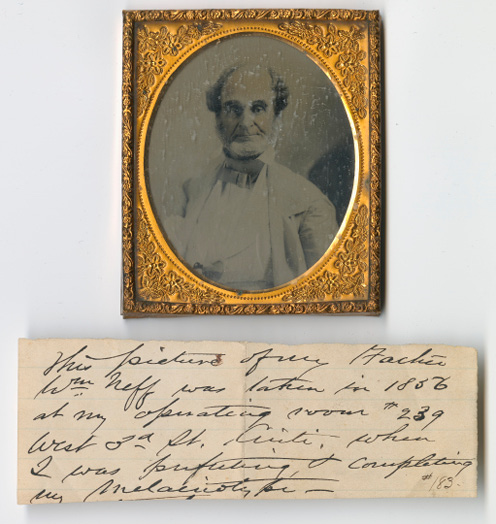

Archer’s collodion formula was modified and adjusted by many, or ‘improved’, to use the USPO’s nomenclature. Among the processes that built on Archer’s formulas were tintypes. Known in their era by several names, but generally known as tintypes today, their history demonstrates how photographic processes could be moved from individual and small-scale production to mass manufacturing. Tintypes are unique images printed on thin iron sheets coated with collodion-based emulsions. When the image is developed, it appears as a positive and requires no additional printing and only modest packaging though it can be found cased like daguerreotypes and ambrotypes. Hamilton Smith’s melainotype patent, his name for a tintype, was assigned to Peter Neff, Jr. Competition with Victor M. Griswold forced him to improve his own product, making it more affordable to consumers.62 Ultimately, Neff sold his plates to the Waterbury Button Company, which began mass producing photographic images.63

Smith, a professor of natural sciences at Kenyon College in Ohio, developed a process of applying a collodion emulsion to a thin iron plate coated prepared with a black varnish, often called a japanned surface, that renders the image as a positive. It was quick, inexpensive, and less cumbersome than other processes, enabling photographers to take the camera outside of the studio.

Smith was granted patent number 14300 on 19 February 1856 for the ‘production of pictures on japanned surfaces’. His former student and darkroom assistant, Peter Neff, and his father bought the patent and began manufacturing plates in Cincinnati, Ohio (see Figure 21). By October 1856, Neff was advertising plates, sending out representatives to teach and demonstrate the process, and distributing an instruction manual, The Melainotype Manual, Complete. He also secured four agents, including Edward Anthony, to sell his product. Henry H. Snelling, the editor of Photographic and Fine Art Journal, would declare, ‘This style of picture [tintypes] we have spoken of in a former number, and we can only add here, that our prediction as to the capability of superceding [sic] the Ambrotype [his emphasis], is fast becoming realized’.64 Some photographers specialized in making just ambrotypes or tintypes. Yet others, produced both and offered customers a choice.65 Today, tintypes are perhaps the most abundant of the non-paper processes found in archives and collections.

Fig. 21 Peter Neff, William Neff (1856), melainotype (tintype), catalog number PG.000183.66 https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_7 51624.

On 21 October 1856, Victor M. Griswold, also one of Smith’s students, was granted patent number 15924 for ‘bituminous ground for photographic pictures’, a modification to an earlier patent. He enameled his plates differently and called the format ‘ferrotype’. Neff’s patent was for the process of making the images on the surfaced plates, while Griswold’s was for the surfacing of the plates.67 Neither was legally stepping on the other’s toes, so the competition for the favored product had to take place in the marketplace rather than in a court of law.

Both men undertook the manufacturing of plates amid several challenges. Photographic innovation and invention held an east-coast bias whereas both Neff and Griswold were from Ohio. News from the east was more easily gathered and distributed than when it came from the reverse direction. Consequently, Neff moved his production to Middletown, Connecticut in 1857 to be in closer proximity to New York City. With additional experts in manufacturing in proximity, he made lighter plates on a larger scale. In summer 1859, Griswold substantially cut the prices of his plates to try to counter Neff’s improvements.68

But Neff need not have worried, as another Connecticut business, the Waterbury Button Company that would become part of Scovill Manufacturing, was beginning to mass-manufacture photographic buttons and political medals. Humphrey’s Journal wrote, ‘Politics will help our friend Neff…There is no knowing who will be President until after the election. Therefore, the admirers of “Old Uncle Abe” [Abraham Lincoln], Breckenridge, Douglas and all the other candidates… want pictures of their leaders’.69 The company produced hundreds of thousands of button images in 1860 using Neff’s plates.

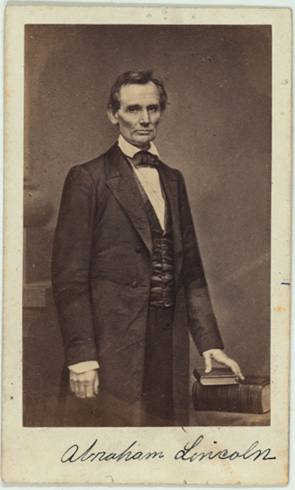

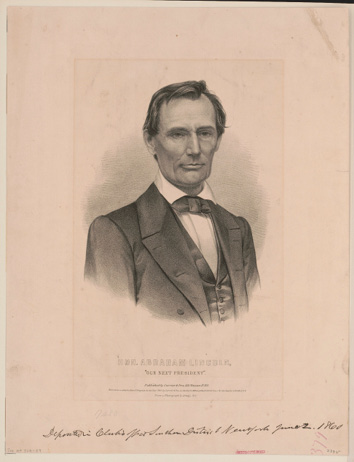

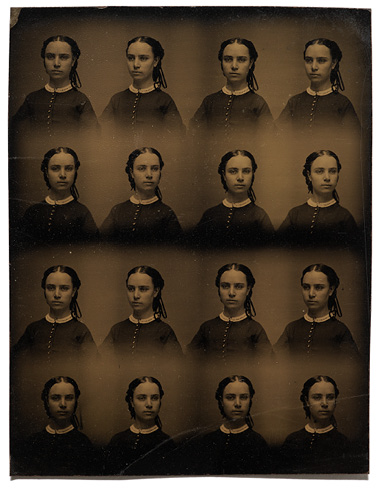

Abraham Lincoln’s campaign buttons bring together an interesting example of mass manufacturing and questions about copyright, or at least the reuse of images. The image of Lincoln takes on a series of iterations that begins with one of the poses from his famous session with Mathew Brady after the Cooper-Union address on 27 February 1860.70 Brady made numerous paper copies in the form of cartes-de-visite that were easily produced and readily sold by his studio, his distributors, and Lincoln’s campaign (see Figure 22).71 Currier and Ives used Brady’s photograph as the basis for their lithograph, Abraham Lincoln…Our Next President (see Figure 23). The Waterbury Button Company used a multi-lens camera, such as one like Thomas Barbour’s, with a repeating back to photograph a detail from the lithograph (see Figure 24). Depending on the camera and the size of the plate between sixteen and seventy-two very small images could be produced (see Figure 25). The gem tintypes, the name for the small coin-sized image, were cut and placed in the button or medal. Photographing the lithographic prints eliminated the cost of making a small engraving or requiring a person to pose for multiple exposures. It also necessarily reduced the size of the image on the plate to fit the button’s size. This rapid process meant that hundreds of small portraits of Lincoln could be made within just a few hours (see Figure 26).

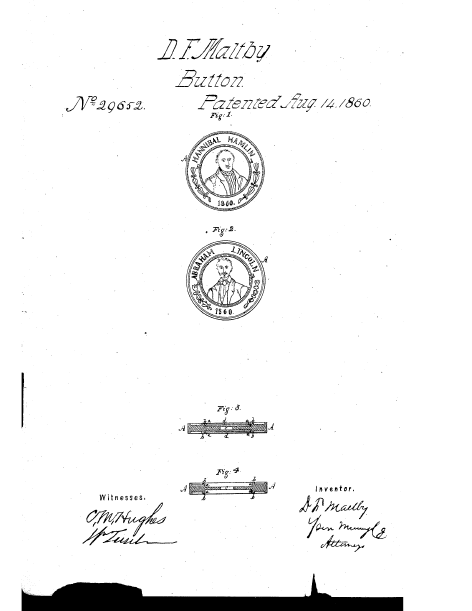

Notice how the highlight in Lincoln’s bowtie matches the print, and that the flick of hair over his ear and lock on his forehead are the same across all the images. In Douglass F. Maltby’s designs for his patent specifications, he included the portrait of Hannibal Hamlin (whose image is on the obverse of the actual button) and Lincoln, both of whom are rendered in reverse from the original source material (see Figure 27). Lincoln won the Presidency and led the country and the Union Army during the Civil War.

Fig. 22 Mathew Brady, Abraham Lincoln (1860), carte-de-visite, Washington, DC, Library of Congress, LC-MSS-44297-33-001, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss4429700001/.

Fig. 23 Currier & Ives, Hon. Abraham Lincoln, Our Next President (1860), lithograph, Washington, DC, Library of Congress, LC-USZC2-2593, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002695894/.

Fig. 24 Thomas Barbour, Patent model 61,139, Four Lens Tintype Camera (15 January 1867), catalog number PG.001041, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmah_1101428.

Fig. 25 Thomas Barbour, Multiple images of portrait of girl made with Barbour’s four lens tintype camera (1866–1867), tintype, catalog number PG.001041A, http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=PG.001041A.

Fig. 26 Scovill Manufacturing Co. Abraham Lincoln/Hannibal Hamlin (1860), tintype political campaign pin, Washington, DC, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Division of Work & Industry, catalog number 1981.0296.1295, http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=1981.0296.1295.

Fig. 27 Douglass F. Maltby, Specifications for Patent Number 29652 Button (14 August 1860), patent drawing specifications, Washington, DC, United States Patent and Trademark Office, https://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?docid=00029652.

The beginning of the Civil War was good for the tintype business. The durability of the plates and the ease of production increased. The number of newly enlisted soldiers increased, as did their desire to be photographed lest they not return. Photographers made tintypes in studios but were also able to take the studio to the battlefield.72 Neff’s and Griswold’s businesses were joined by four other manufacturers. The competition drove down prices and improved quality; however the late stages of the war itself diminished trade, amid a national economic downturn and fewer troop deployments. With fortuitous timing, Neff sold his business to his Connecticut manufacturing partner James O. Smith in 1863. Griswold produced plates until 1867, when he sold the company to John Dean & Company. Paper-based photography and the introduction of the dry plate negative in the 1870s would supersede the tintype. Griswold’s legacy would be remembered as the name of his plates, ferrotype, became the preferred term for the remainder of the nineteenth century.

Keeping and Embellishing Photographs

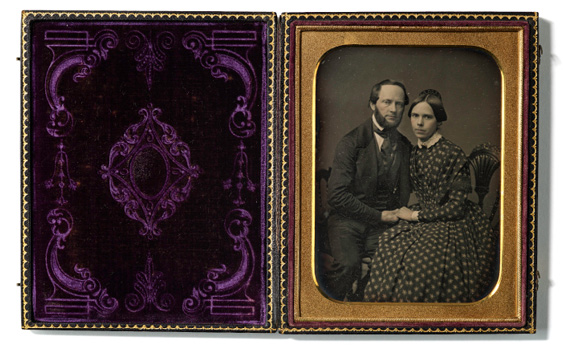

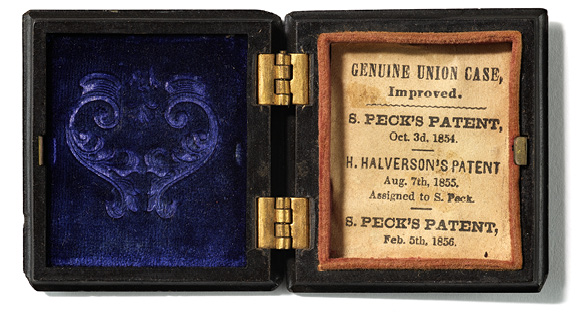

Designs and methods for the preservation and presentation of images in frames, cases, albums, viewers, and more were also within the purview of the USPO.73 Here, we see that not only function and process was protected by patents, but also some aesthetics. Maltby’s housings for portraits of those running for office sat at the intersection of a long history of campaign buttons and medals, and the need to house and protect photographic images.74 The circa 1861 photograph showing the interior of frame maker James S. Earle’s shop (see Chapter 7, Figure 1) showcases the importance of frames as aesthetic objects. They reflect the style and fashion of the day through their designs, materials, and hanging or mounting structures, some of which received patents. The artistic attributes of these objects situate the photograph as part of the practice of collecting, displaying and incorporating visual culture into everyday life as one could ‘afford a beautiful parlor ornament’.75 Samuel Peck was one such person who patented and sold frames, mats, and cases for photographs (see Figure 28).76 Usually hidden under an image, the listed patents indicate Peck’s contribution to shaping aesthetics found in homes of the era. These patents are for the design and construction of the case that is both functional and aesthetic (see Figure 29).77 As one considers material culture of the nineteenth century, some artifacts are comprised of patents that may or may not be visible.

Fig. 28 Unidentified maker, Samuel Peck and his second wife (about 1847), daguerreotype, catalog number PG.75.17.931, http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=PG.75.17.931.

Fig. 29 Samuel Peck, Case interior showing list of Peck’s case patents (late 1860s), interior of open case, catalog number PG.75.17.798, http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=PG.75.17.798.

Conclusion

Though not always obvious or visible because they are outshined by the aesthetics, use, and ideas of the pictures they support, the calotype, the tintype, the ambrotype and other image-making processes transmit and embody a host of nineteenth-century national policies, photographic practices, and manufacturing and intellectual histories that shaped the material and physical aspects of the picture. In 1889, F. V. Butterfield read his widely republished paper to the Chemists’ Assistants’ Association in London, expressing his understanding of the state of photography. In it he notes: ‘Boasting of barely half a century’s existence, photography has made such rapid and gigantic strides that the position it holds to-day [sic] is one of the highest importance’.78 His commentary is not one of the great strides in the democratization of images, but rather conveys an amazement with human ingenuity and the ability to harness science for art and usefulness: one that was often reflected in the tensions that surrounded patents. As we study images, their meanings, circulation, and consumption, the very format of their existence also transmits a series of controlled choices made by innovators, national policies, and commercial interests. These histories that envelope images can serve to deepen our understanding of the complicated ways in which people living in the nineteenth century created and experienced visual culture.

Bibliography

‘The Ambrotype Patent Case’, The Photographic and Fine Art Journal, X, II (February 1857), p. 56, https://archive.org/embed/photographicfine1018newy.

American Journal of Photography, 15 November 1865, pp. 239–240.

‘Art & Architecture Thesaurus Full Record Display (Getty Research)’, http://www.getty.edu/vow/AATFullDisplay?find=ambrotype&logic=AND¬e=&english=N&prev_page=1&subjectid=300127186.

Berg, Paul, Nineteenth Century Photographic Cases and Wall Frame (United States, Berg, 2003).

Bogardus, Abraham, ‘The Experiences of a Photographer’, Lippincott’s Magazine (May 1891).

Brizuela, Natalia, ‘Light Writing in the Tropics’, Aperture, 215 (2014), pp. 32–37, https://aperture.org/editorial/light-writing-tropics/.

Butterfield, F. V., ‘Photography’, American Journal of Pharmacy, 61 (Jan 1889), p. 45.

‘Civil War Photography| Bibliographies of Selected Sources| Articles and Essays| Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints| Digital Collections| Library of Congress’, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-war-glass-negatives/articles-and-essays/bibliographies-of-selected-sources/civil-war-photography/.

‘Correspondence upon Cutting’s Patents’, Humphrey’s Journal, VIII, 21 (1 March 1857), p. 326.

‘The Cutting Patents Denounced! New York Photographers assemble for defence [sic]!’, American Journal of Photography, 2, 19 (1 March 1860), pp. 289–292.

Encyclopedia of Photography, ed. by International Center of Photography, 1st ed (New York: Crown, 1984), p. 285.

Fessenden, Marissa, ‘This Is the First Known Photo of the Smithsonian Castle’, Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/smithsonian-celebrates-169th-birthday-image-castles-construction-180956212/.

‘Frederick Scott Archer’, The British Journal of Photography, XXII (28 February 1873), p. 102, https://archive.org/embed/britishjournalof22unse.

Gillespie, Sarah Kate, The Early American Daguerreotype: Cross-Currents in Art and Technology, Lemelson Center Studies in Invention and Innovation (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2016).

Gould, A. R., ‘A Few Leaves From My Diary’, The Philadelphia Photographer, XIX (January 1882) 217, pp. 13–14, http://archive.org/details/philadelphiaphot1882phil.

‘The Great Photographic Lawsuit of 1854’, British Journal of Photography 52:15 (December 1905) p. 985.

Gurney, Jeremiah, Etchings on Photograph (New York, 1856), pp. 1–27.

Hanlon, David Prospects of Enterprise: The Calotype Venture of the Langenheim Brothers’, History of Photography, 35:4 (2011), 339–354, https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2011.606729.

——, Illuminated Shadows: The Calotype in Nineteenth Century America, 1st Ed (Nevada City, CA: Carl Mautz Pub, 2013).

Harris, Mazie McKenna, ‘Inventors and Manipulators: Photography as Intellectual Property in Nineteenth-Century New York’ (doctoral thesis, Brown University, 2014), available through History of Art and Architecture Theses and Dissertations, Brown Digital Repository, Brown University Library, https://doi.org/10.7301/Z0CF9NF2.

Harris, Mazie, Matthew Fox-Amato, and Christine Hult-Lewis, Paper Promises: Early American Photography (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018).

Honeyman, AVD, ‘Matters of the Month’, The Photographic Times and American Photographer, V, 58 (1875), p. 241.

How Was It Made? Calotypes| V&A, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jCWQTNWgyM.

‘James Smithson, Founding Donor’, Smithsonian Institution Archives, 2011, https://siarchives.si.edu/history/james-smithson.

Janssen, Barbara Suit, Patent Models Index: Guide to the Collections of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution: Listings by Patent Number and Invention Name, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2010), https://doi.org/10.5479/si.19486006.54-1.

Jensen, James S., ‘Cutting’s Edge’, The Collodion Journal, 5:19 (Summer 1999) pp. 5–9.

Krainik, Clifford, Michele Krainik, and Carl Walvoord, Union Cases: A Collector’s Guide to the Art of America’s First Plastics (Grantsburg, WI: Centennial Photo Service, 1988).

Levy, Marie Cordié, ‘Matthew [sic] Brady’s Abraham Lincoln’, http://www.asjournal.org/60-2016/matthew-bradys-abraham-lincoln/#.

Lind, Edward, Samuel F.B. Morse, His Letters and Journals. (United States: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914).

‘The Melainotype’, The Photographic and Fine Art Journal, X, II (February 1857), p. 64.

Morse, Samuel F. B., ‘The Daguerreotype’, New York Observer, 17:16 (20 April 1839), http://www.daguerreotypearchive.org/texts/N8390002_MORSE_NY_OBSERVER_1839-04-20.pdf.

Morse, Samuel Finely Breese and Edward Lind Morse, Samuel F.B. Morse, His Letters and Journals. (United States: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), pp. 128–130.

‘The Niépce Heliograph’, https://www.hrc.utexas.edu/niepce-heliograph/.

Peale-Sellers families, ‘Peale-Sellers Family Collection, 1686–1963’, https://search.amphilsoc.org/collections/view?docId=ead/Mss.B.P31-ead.xml#bioghist.

‘The Photographic Patents’, The Photographic and Fine Art Journal, VII, IX (1854), p. 277, https://archive.org/embed/photographicfine12185newy.

‘Photography — Its Origin, Progress, And Present State’, The National Magazine; Devoted to Literature, Art, and Religion, 1, 6 (Dec 1852), p. 510.

Post, Robert C., ‘Patent Models: Symbols of an Era’, American Enterprise: Nineteenth-Century Patent Models. (United States: Smithsonian Institution, 1984), pp. 8–13.

Price List. Samuel Peck and Co.’s Union Goods, advertisement. The Photographic Times and American Photographer, II, 16 (1872), p. 57.

Rosenblum, Naomi, ‘The Early Years: Technology, Vision, Users 1839–1875’, A World History of Photography (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984) (2007, Fourth ed.).

Schaaf, Larry J. and William Henry Fox Talbot, Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge [England]; New York, USA: Cambridge University Press in cooperation with the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, 1996).

Schimmelman, Janice G., American Photographic Patents, The Daguerreotype & Wet Plate Era 1840–1880 (Nevada City, NV: Carl Mautz Publishing, 2002).

——, The Tintype in America 1856–1880 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2007).

Sheppard, Furman and Henry Howson, ‘Opposition to and Refusal of James A. Cutting’s Patent,’ Arguments Before the U.S. Patent Office and Justices of the Supreme Court, D.C.: With Decisions, Comments, &c. (United States, Philadelphia, 1871), pp. 343–365.

Simmons, MP, ‘The Early Days of Daguerreotyping’, Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, V, 21 (September 1874), 309–11. Reprint, Scientific American (14 November 1874), pp. 311–312.

Singleton’s Nashville Business Directory, p 5. Polk’s Nashville (Davidson County, Tenn.) City Directory… 1865 ([Nashville] R. L. Polk & co., 1865), http://archive.org/details/polksnashvilleda00nash.

Suit Janssen, Barbara, Patent Models Index: Guide to the Collections of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution: Listings by Patent Number and Invention Name, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2010), https://doi.org/10.5479/si.19486006.54-1.

Sullivan, Edmund B., American Political Badges and Medals 1789–1892 (Massachusetts: Quarterman Publications, 1981).

Taft, Robert, ‘The Tintype’, Photography and the American Scene (New York: MacMillan Company, 1938), pp. 153–157.

True, Frederick, ‘An Account of the United State National Museum’, Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895) p. 290.

USA House of Representatives, House Documents (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1866).

US Congress, Page: United States Statutes at Large Volume 1.djvu/443 (wikisource.org, 1793), https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page%3AUnited_States_Statutes_at_Large_Volume_1.djvu/443.

Weatherwax, Sarah, ‘Part 1: A Philadelphia Snapshot from When Daguerreotypes Were New’, National Museum of American History, 2015, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/part-1-philadelphia-snapshot-when-daguerreotypes-were-new.

Welling, William, Photography in America: The Formative Years, 1839–1900 (New York: Crowell, 1978).

The Wet Collodion Process, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiAhPIUno1o.

Wikisource contributors, ‘United States Statutes at Large/ Volume 1/2nd Congress/ 2nd Session/Chapter 11’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia (1845, last rev. 18 March 2021), https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/United_States_Statutes_at_Large/Volume_1/2nd_Congress/2nd_Session/Chapter_11.

1 All images in this chapter are from the Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian’s National History Museum of American History, Washington, DC unless otherwise noted. Most images can be found at https://collections.si.edu.

2 ‘The Niépce Heliograph’, https://www.hrc.utexas.edu/niepce-heliograph/; Natalia Brizuela, ‘Light Writing in the Tropics’, Aperture no. 215 (2014), pp. 32–37 (p. 35), https://aperture.org/editorial/light-writing-tropics/.

3 Sarah Kate Gillespie, The Early American Daguerreotype: Cross-Currents in Art and Technology, Lemelson Center Studies in Invention and Innovation (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2016), pp. 26–27.

4 Naomi Rosenblum, ‘The Early Years: Technology, Vision, Users 1839–1875’, in Naomi Rosenblum, A World History of Photography (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984) (2007, Fourth ed.), pp. 14–37 (pp. 17–18).

5 United States Congress, ‘United States Statutes at Large, Volume 1’, Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/United_States_Statutes_at_Large/Volume_1/2nd_Congress/2nd_Session/Chapter_11.

6 Frederick True, ‘An Account of the United State National Museum’, Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895), p. 290.

7 ‘James Smithson, Founding Donor’, Smithsonian Institution Archives, 2011, https://siarchives.si.edu/history/james-smithson.

8 NMAH accession 48866; Barbara Suit Janssen, Patent Models Index: Guide to the Collections of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution: Listings by Patent Number and Invention Name, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2010), https://doi.org/10.5479/si.19486006.54-1.

9 Janice Schimmelman, The Tintype in America 1856–1880 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2007), pp. 4–6.

10 Samuel F. B. Morse, ‘The Daguerreotype’, New York Observer 17:16 (20 April 1839), p. 62, http://www.daguerreotypearchive.org/texts/N8390002_MORSE_NY_OBSERVER_1839-04-20.pdf.

11 Samuel Finely Breese Morse, and Edward Lind Morse, Samuel F.B. Morse, His Letters and Journals (United States: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), pp. 128–130.

12 MP Simmons, ‘The Early Days of Daguerreotyping’, Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, V, 21 (September 1874), pp. 309–311. (Reprinted in Scientific American (14 November 1874) pp. 311–312).

13 Robert C. Post, ‘Patent Models: Symbols of an Era’, American Enterprise: Nineteenth-Century Patent Models (United States: Smithsonian Institution, 1984), pp. 8–13 (p. 10).

14 Morse, His Letters, p. 22.

15 Gillespie, The Early American Daguerreotype, p. 135.

16 Post, ‘Patent Models’, p. 11.

17 Sarah Weatherwax, ‘Part 1: A Philadelphia Snapshot from When Daguerreotypes Were New’, National Museum of American History, 2015, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/part-1-philadelphia-snapshot-when-daguerreotypes-were-new.

18 David R. Hanlon, Prospects of Enterprise: The Calotype Venture of the Langenheim Brothers’, History of Photography, 35:4 (2011) pp. 339–354, https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2011.606729.

19 Janice G. Schimmelman, American Photographic Patents, The Daguerreotype & Wet Plate Era 1840–1880 (Nevada City, NV: Carl Mautz Publishing, 2002) pp. 4–5, 12, 30, 32, 49.

20 ‘Hyalotype’, Encyclopedia of Photography, ed. by International Center of Photography, 1st ed (New York: Crown, 1984) p. 285; Marissa Fessenden, ‘This Is the First Known Photo of the Smithsonian Castle’, Smithsonian Magazine https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/smithsonian-celebrates-169th-birthday-image-castles-construction-180956212/. The first known image of the Smithsonian’s first building, the Castle, is a Langenheim hyalotype.

21 How Was It Made? Calotypes| V&A, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jCWQT NWgyM.

22 ‘The Photographic Patents’, The Photographic and Fine Art Journal VII, IX (1854), p. 277.

23 ‘The Great Photographic Lawsuit of 1854’, British Journal of Photography, 52 (15 December 1905), p. 985.

24 David R. Hanlon, Illuminated Shadows: The Calotype in Nineteenth Century America, 1st Ed (Nevada City, CA: Carl Mautz Pub, 2013) p. 64.; ‘The Pencil of Nature| Home Page’, https://www.thepencilofnature.com/.

25 Hanlon, Shadows, p. 67.

26 Ibid., p. 61.

27 Schimmelman, American Photographic Patents, p. 5.

28 Hanlon, Shadows, p. 61. Quoted from letter from Anthony to Talbot, 12 July 1847, London, British Library, Fox Talbot Collection, LA-47-066; Talbot Correspondence Project, document #5977.

29 Hanlon, Shadows, p. 65. Hanlon quotes from Letter from W&F Langenheim to Talbot, 5 February 1849, National Media Museum Bradford, 1937–4971; Talbot Correspondence Project, document #6210.

30 Ibid., p. 88.

31 Ibid., p. 97.

32 Jeremiah Gurney, Etchings on Photograph (New York, 1856), pp. 1–27 (p. 8). In his pamphlet, Gurney asserts that there were 4,000 daguerreotypists and a $10,000,000 business that included the studio, manufacturers, and other associated business.

33 ‘Photography — Its Origin, Progress, And Present State’, The National Magazine; Devoted to Literature, Art, and Religion, 1, 6 (Dec 1852), p. 510.

34 Gillespie, Early American Daguerreotype, p. 5.

35 William Welling, Photography in America: The Formative Years, 1839–1900 (New York: Crowell, 1978), p. 59.

36 Larry J. Schaff, ‘To Fix or Not to Fix? — Sir John Herschel’s Question’, https://talbot.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/2016/01/22/to-fix-or-not-to-fix-sir-john-herschels-question/.

37 ‘Frederick Scott Archer’, The British Journal of Photography, XXII (28 February 1873), p. 102, https://archive.org/embed/britishjournalof22unse.

38 The Wet Collodion Process, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiAhPIUno1o.

39 A. R. Gould, ‘A Few Leaves From My Diary’, The Philadelphia Photographer, XIX, 217 (January 1882), pp. 13–14, http://archive.org/details/philadelphiaphot1882phil.

40 ‘Art & Architecture Thesaurus Full Record Display (Getty Research)’, http://www.getty.edu/vow/AATFullDisplay?find=ambrotype&logic=AND¬e=&english=N&prev_page=1&subjectid=300127186. The term ‘ambrotype’ is used predominately in the US. Cutting attempted to trademark ‘ambrotype’ in the UK where the process is usually called collodion glass positives.

41 Larry J. Schaaf and William Henry Fox Talbot, Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge [England]; New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, in cooperation with the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, 1996), p. 396.

42 USA House of Representatives, House Documents (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1866). Patent 8077 for spark arresters 1851.

43 Mazie McKenna Harris, ‘Inventors and Manipulators: Photography as Intellectual Property in Nineteenth-Century New York’ (doctoral thesis, Brown University, 2014), p. 125, available through History of Art and Architecture Theses and Dissertations, Brown Digital Repository, Brown University Library, https://doi.org/10.7301/Z0CF9NF2.

44 Harris, ‘Inventors and Manipulators’, p. 124.

45 Harris, ‘Inventors and Manipulators’; Mazie M. Harris, Matthew Fox-Amato, and Christine Hult-Lewis, Paper Promises: Early American Photography (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018).

46 Harris, ‘Inventors and Manipulators’, p. 116.

47 Peale-Sellers families, ‘Peale-Sellers Family Collection, 1686–1963’, https://search.amphilsoc.org/collections/view?docId=ead/Mss.B.P31-ead.xml#bioghist. Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) was an influential painter and socialite who helped set a national iconography related to American culture, politics, and science. His ten children, most named after well-known artists, continued his legacy in the worlds of museums, art, and commerce. Titian Ramsay Peale (1799–1885) was the youngest, making a name early in life for his scientific illustrations of butterflies; he also worked with Charles Darwin on the latter’s second expedition. Peale joined the US Patent Office seeking a regular income to support his family; NMAH accession 263090, gift of Jacqueline Hoffmire, 11 October 1965.

48 ‘Correspondence upon Cutting’s Patents’, Humphrey’s Journal, VIII, 21 (1 March 1857) p. 326. Some of the correspondence between Peale and Cutting was published.

49 James S. Jensen, ‘Cutting’s Edge’ in The Collodion Journal, 5, 19 (Summer 1999), p. 5. Quoted by Jensen.

50 Arguments Before the U.S. Patent Office and Justices of the Supreme Court, D.C.: With Decisions, Comments, &c (Howson & Son, 1871) pp 343–365 (p. 347). The sums of money and the tangled distribution of rights and shares were revealed by the Philadelphia lawyers Howson & Son, who opposed (on behalf of Edward Wilson) the reissue of Cutting’s patent.

51 ‘The Ambrotype Patent Case’, The Photographic and Fine Art Journal, X, II (1857) p. 56.

52 Note that Abraham Bogardus photographed Samuel F. B. Morse (see Figure 5 in this chapter).

53 ‘The Cutting Patents Denounced! New York Photographers assemble for defence [sic]!’ in American Journal of Photography, 2, 19 (1 March 1860), 289–292 (p. 291); Abraham Bogardus, The Experiences of a Photographer, Lippincott’s Magazine (May 1891).

54 ‘The Cutting Patents Denounced!’, p. 292.

55 Mathew Brady’s ambrotypes were often seen in publications and identified as such as engraved likenesses after his portraits of his celebrity and well-known sitters, including Ballou’s Drawing Room Pictorial Companion between 1857 and 1858; ‘The Cutting Patents Denounced!’, p. 292.

56 ‘The Cutting Patents Denounced!’, p. 291.

57 Jensen, ‘Cutting’s Edge’, p. 5.

58 American Journal of Photography, 15 November 1865, 239–240.

59 Ibid.

60 Jensen, ‘Cutting’s Edge’, p. 7.

61 Sheppard, Furman and Henry Howson, ‘Opposition to and Refusal of James A. Cutting’s Patent,’ Arguments Before the U.S. Patent Office and Justices of the Supreme Court, D.C.: With Decisions, Comments, &c. (United States, Philadelphia, 1871), pp. 343–365 (p. 360), https://www.google.com/books/edition/Arguments_Before_the_U_S_Patent_Office_a/UZZBAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

62 The name ‘tintype’ is a misnomer as there is no tin involved; however, tinsnips (a variety of scissors) are used to trim the metal plates.

63 Schimmelman, Tintype in America, p. 46.

64 ‘The Melainotype’ in The Photographic and Fine Art Journal, X, II (February 1857) 64.

65 Singleton’s Nashville Business Directory, p 5. Polk’s Nashville (Davidson County, Tenn.) City Directory… 1865 ([Nashville] R. L. Polk & co., 1865), http://archive.org/details/polksnashvilleda00nash; NMAH, PHC. Ephemera collections (advertisements, business cards, broadsides, etc.) reveal the scope of a photographer’s business.

66 NMAH, PHC, Accession number 24366. Handwritten note, ‘This picture of my father Wm. Neff was taken in 1856 at my operating room #239 West 3d St. Cinti [Cincinnati, Ohio] when I was perfecting and completing my melainotype — ’. This is one of several dozen tintypes acquired from Neff in 1891.

67 Robert Taft, ‘The Tintype’, Photography and the American Scene (New York: MacMillan Company, 1938), pp. 153–157.

68 Schimmelman, Tintype in America, pp. 37–52.

69 Taft, Photography and the American Scene, p. 158. Quoted by Taft from Humphrey’s Journal, September 1860.

70 Abraham Lincoln won the nomination to be the Republican Party in May 18, 1860. The election was held on November 6, 1860, and he was inaugurated on March 4, 1861. It is interesting to note the patent awarded on August 14, 1860 using Abraham Lincoln’s and Hannibal Hamlin’s images. The buttons were likely manufactured before the patent was awarded.

71 Marie Cordié Levy, ‘Matthew [sic] Brady’s Abraham Lincoln’, http://www.asjournal.org/60-2016/matthew-bradys-abraham-lincoln/#.

72 ‘Civil War Photography| Bibliographies of Selected Sources| Articles and Essays| Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints| Digital Collections| Library of Congress’, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-war-glass-negatives/articles-and-essays/bibliographies-of-selected-sources/civil-war-photography/. Photographers who made wet-plate collodion negatives tended to photographed landscapes and battlefields. Tintypes were predominately used for portraiture.

73 Schimmelman, American Photographic Patents, pp. 115–116. There were no less than thirty-eight photographic-related patents that include frames, cases, levelers for making picture frames, mats, and more. There was a separate category at the USPO for frames and such that were not listed as photography specific.

74 Edmund B. Sullivan, American Political Badges and Medals 1789–1892 (Massachusetts: Quarterman Publications, 1981).

75 AVD Honeyman, ‘Matters of the Month’ in The Photographic Times and American Photographer, V, 58, 1875, p. 241.

76 Price List. Samuel Peck and Co.’s Union Goods, advertisement. The Photographic Times and American Photographer, II, 16 (1872), p. 57.

77 Paul Berg, Nineteenth Century Photographic Cases and Wall Frame (United States, Berg, 2003); Clifford Krainik, Michele Krainik, and Carl Walvoord, Union Cases: A Collector’s Guide to the Art of America’s First Plastics (Grantsburg, WI, USA: Centennial Photo Service, 1988).

78 F. V. Butterfield, ‘Photography’ American Journal of Pharmacy, 61 (Jan 1889), 45.