13. King Tāwhiao’s Photograph: Copyright, Celebrity, and the Commercial Image in Nineteenth-Century New Zealand

© 2021 Jill Haley, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0247.13

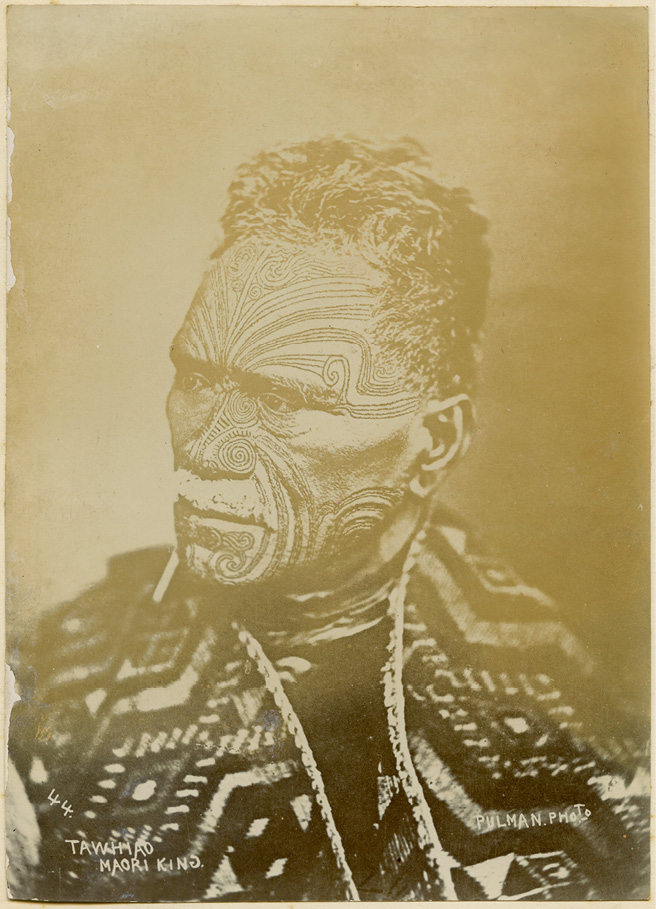

On 19 January 1882, the Māori king Tūkāroto Pōtatau Matutaera Tāwhiao arrived in Auckland for a two-week sojourn.1 His visit had been eagerly awaited, and an enormous, animated crowd turned out to the wharf to greet the King and his party. As a Māori celebrity and guest to the city, a reception committee had been organized to entertain Tāwhiao, escorting him to various locations around town. That first afternoon, he visited the Supreme Court building, a cabinetmaker’s premises, and Elizabeth Pulman’s photographic studio where he inspected photographs of Māori chiefs.2 Tāwhiao went back to the Pulman studio several days later to select some of the photographs he had seen, and on a third trip, he sat for his portrait. One of the images from that session was selected and produced for commercial sale (see Figure 1).3 Little did Tāwhiao or the Pulman studio know that seven months later, this image would be the center of New Zealand’s first photographic copyright lawsuit.

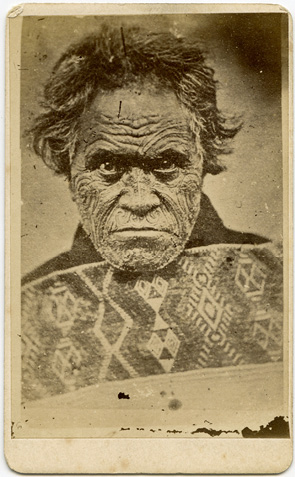

Fig. 1 E. Pulman studio, Tūkāroto Pōtatau Matutaera Tāwhiao (1882), Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand, 1968.209.5.

Modelled on Britain’s Fine Arts Copyright Act 1862, the New Zealand Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 protected original works of art, defined as paintings, drawings, engravings, useful and ornamental designs, sculptures, photographs, and negatives made by New Zealand residents.4 Despite the fact that the colony of New Zealand was not covered by Britain’s Act, it had taken the colonial government fifteen years to produce its own protective legislation for artworks.5 Rumours about an impending imperial copyright act in the mid-1870s were partly to blame for the delay.6 Mounting pressure, some from photographers who had concerns about photographic piracy, finally motivated the New Zealand government to act. Member of Parliament and amateur photographer William Travers drafted the Bill, and in November 1877 the Act was passed.7 It was not legally tested for photographs until August 1882 when the studio of Elizabeth Pulman, owned by Elizabeth and her second husband John Blackman, sued Charles Henry Monkton for unlawfully copying the portrait of Tāwhiao.

This chapter explores the case of Blackman v. Monkton. In the first instance, it was a test for the new copyright legislation, finding flaws and weaknesses that would be rectified several years later with a new act. However, an examination of its context highlights a number of factors related to image production and circulation in nineteenth-century New Zealand beyond copyright law. Commercial photography during the period was closely tied to the rise of celebrity images and the public’s demand for them. Māori chiefs were New Zealand’s homegrown celebrities, and there was intense competition among photography studios for a piece of the lucrative Māori celebrity image market. Tāwhiao and other Māori were active and collaborative participants in their own image-making, and their agency is clearly evident in their dealings with studios.

Blackman v. Monkton

During the 1860s, photography was a burgeoning business in the recently established colony of New Zealand. English immigrant George Pulman, who trained as a draughtsman, turned his hand to the trade and established a commercial studio in Auckland in 1867. After his death in 1871, his widow Elizabeth retained control of the business and ran it under her own name.8 When she married John Blackman in 1875, he managed the studio with her, but it continued to operate under the name E. Pulman (later Pulman and Son). The studio developed a brisk trade in photographs of Māori — images that were in high demand in New Zealand, and therefore highly profitable. In the 1880s, the Pulman studio registered many images of Māori chiefs, legally securing their copyright. Although the records no longer exist, we know that the studio registered the image of Tāwhiao because a case for its copyright infringement appeared in court in 1882.9 This was not the first time that Elizbeth Pulman had encountered piracy. Shortly after George’s death in 1871, she wrote to Auckland’s Daily Southern Cross newspaper about a photograph of a map produced by her husband that was being copied and sold by a third person without her permission. While an unethical act, it pre-dated New Zealand’s photographic copyright legislation and was not illegal. Pulman’s only recourse was the court of public opinion. In her letter to the newspaper, she begged the public not to buy the photograph of the map, which was her principal source of income for supporting herself and her seven young children.10 Newspapers such as the Auckland Star supported her, threatening that if the sale of the ‘pirated maps’ continued, it would publish the name of the man ‘who has committed such a dastardly act’.11

When Elizabeth and John Blackman discovered that Charles Henry Monkton, operating as the London Photographic Company, had been copying and selling their studio’s copyrighted photograph of Tāwhiao, they acted.12 On 23 August 1882, Monkton was charged with a breach of the Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 which, according to the prosecutor Mr. Cotter, was the first case in New Zealand brought under the Act with regard to photographs.13 The complaint was with regard to a ‘certain work of art, to wit, a photograph of an aboriginal native, called King Tawhiao’.14 The prosecution claimed that Monkton had violated Section 6 of the Act by ‘unlawfully, and without the consent of John Blackman, the proprietor of such copyright, copy for sale the said work, on the 16th August, 1882’.15 Monkton’s lawyer, Edward Cooper, entered a plea of ‘not guilty’ for his client.16

The evidence from the prosecution was voluminous, and a number of witnesses testified.17 George Steel, the manager of the Pulman studio, deposed that he had taken the photograph on 28 January 1882.18 The distinctive cloak around the King’s shoulders, he pointed out, was a prop owned by the studio. John Blackman confirmed that the image of Tāwhiao was taken by Steel and had been duly registered with the government in April. Frederick Pulman, Elizabeth’s son and partner in the business, stated that he had purchased a portrait of King Tāwhiao from Monkton’s wife on 11 August. Mortimer Fairs, a friend of Blackman’s, testified that he had visited Monkton’s studio on 16 August and purchased nine photographs for four shillings and six pence.19 He was adamant that Monkton himself had sold them. Several witnesses agreed that from the quality of the photographs purchased from Monkton, they were clearly copies. When examined by Blackman’s lawyer, Monkton testified that he did not sell any photographs belonging to other studios. However, when presented with a cabinet card of the King produced by the Pulman studio and smaller cartes de visite marked with his studio’s name, he agreed that the smaller ones were copies.20 In his defense, he attested to the fact that he often signed his cards before the photographs were mounted onto them but could not account for the photograph appearing on his signed cards. He implied that an incompetent photographer he had employed for a brief period might have produced them while he was away from Auckland.

The judge dismissed the case, finding that although there was ample evidence that Monkton sold the photographs of Tāwhiao, it had not been proven that he had made the copies. Even if he had, it had not been shown that they were made after the image was registered. Section 5 of the Act made it clear that it was not illegal to copy a work of art that had not been registered for copyright, stating that ‘no proprietor of any such copyright shall be entitled to the benefit of this Act until such registration, and no action shall be sustainable, nor any penalty recoverable, in respect of anything done before registration’.21 The Pulman studio was unable to prove when Monkton had made the copies, and the judge surmised that it was possible that he had lawfully made them between the end of January when the photograph was taken and early April when it was formally registered.22 It was a test case for photographs under the New Zealand Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 and a setback for the Pulman studio. If it had won, the studio stood to receive an immediate financial settlement. According to the Act, upon conviction the offender was to pay the copyright holder a sum not exceeding ten pounds and surrender to them all illegal copies of the work of art. In addition, the copyright holder was entitled to recover damages. It is not known whether Monkton continued selling the photograph.

Why did Monkton risk breaking the law and copy the Pulman studio’s image of Tāwhiao? It might have been a simple matter of ignorance, but it seems unlikely that he was unfamiliar with the Act. During late 1877 and early 1878, its passing was reported on widely in the newspapers. In February 1880, shortly after an amendment in late 1879 that added dramatic works to protection under the Act, the first of several court cases for its infringement reached the press.23 In Gillon v. Lumsden, E. T. Gillon, the New Zealand agent for the English Dramatic Authors Society, took the Invercargill Garrick Club to court for staging the copyrighted play Hunting a Turtle without paying the licensing fee.24 J. T. Lumsden, the secretary for the club, admitted liability and paid the minimum penalty of forty shillings. In the months following, Gillon went on a litigious rampage, successfully bringing cases against several other dramatic groups under the Act.25 If he read the papers, Monkton would have been aware of this flurry of cases, and if he were illiterate, he no doubt would have heard the news through community gossip. Even though no photographic copyright cases had been brought to court yet, he would have had fair warning that the new Act was being exercised successfully.

In all likelihood, Monkton was simply engaging in the widespread practice of copying the work of other photographers, especially images of Māori. There was no requirement under the 1877 Act to mark photographs as having been registered for copyright, so Monkton would have had difficulty knowing that the Tāwhiao image was protected. In fact, a very low percentage of photographs were registered, making most copying legal. And if a copyrighted image had been unlawfully copied, the onus was on the owner of the copyright to discover this and take action as the Pulman studio had. The situation was rectified in 1896 with the passing of the Photographic Copyright Bill, a piece of legislation that addressed the shortcomings of the 1877 Act with regard to photographs.26 Section 2 of the 1896 Act stipulated that in order to be covered, the word ‘Protected’, the name of the photographer or studio, and the date the photograph was taken had to be inscribed on the original negative and appear clearly on the photographic print.

In taking Monkton to court, the Pulman studio was attempting to use the Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 to protect its commercial interests. Kathy Bowrey and Elena Cooper have likewise found in the United Kingdom that the Fine Arts Copyright Act 1862 was often used to protect commercial rather than creator rights with regards to images.27 Pulman had invested financially in the Tāwhiao image in several ways that Monkton had not. Similar to the British system, in order to secure copyright, the studio had to register the image with the government.28 In New Zealand, this entailed completing a form and paying a fee. The application form cost one shilling, and submitting the form and having it registered was an additional two and a half shillings (equivalent to about twenty dollars in today’s money). Many photographic studios found the registration fee expensive and the application process cumbersome. Commercial photographers who produced landscape or celebrity photographs could have hundreds of images to register, and the registration fees on poorly-selling photographs could exceed profits. The Burton Brothers studio was one of the most prolific and successful landscape photography businesses in New Zealand, and the studio photographed some of the most remote places in New Zealand, spending large sums of money doing so. Surprisingly, of the hundreds of photographs Burton Brothers produced in the period between 1887 and 1911, only fifty-two were registered.29 Such a low number suggests that only images that were expected to have commercial success were registered. Copyright registration, it seems, was the exception rather than the rule. However, when they registered their images, studios expected to own the exclusive right to produce them, reap all profits from their sale, and have the courts protect their commercial interests. The advertising of Tāwhiao’s portrait in the Auckland Star and New Zealand Herald newspapers was another outlay the Pulman studio made.30 The first advertisement appeared on the same day that Tāwhiao sat for his portrait and would have been placed and paid for in anticipation of the sitting and before the photograph was actually taken.31 The studio clearly expected the image would be a profitable one worth promoting immediately.

Celebrity, Consumers, and the Circulation of Images

Modern celebrity became established as a part of cultural life during the nineteenth century.32 According to Tom Mole, who traces the origins of celebrity to the late eighteenth century, it required three components — an individual, an industry, and an audience — which combine to ‘render an individual person fascinating’.33 Sharon Marcus notes that these three must work in collaboration for celebrity to exist.34 The phenomenon of the celebrity image that emerged in the 1860s was the result of a convergence of the famous (and infamous), the industry of photography (especially the development of cheap cartes de visite), and consumer demand for these photographs. As print and visual media grew, the access to and circulation of information, gossip, and images of famous people increased, fuelling a popular desire to see and know more about them. The celebrity image became big business.35 An article published in the British weekly magazine Once a Week commented on the ‘commercial value of the human face’ and that sudden fame could send up the value of one’s image ‘to a degree they never dreamed of’.36 In the trade at the time, celebrity images were referred to as ‘sure cards’ because their high demand guaranteed their commercial success.37 Marion & Co. in England was the major wholesale supply point for celebrity cartes de visite in that country, and in 1862 they claimed that they dealt with 50,000 every month.38 In the week after Prince Albert’s death, 70,000 of his photographs were ordered from them, and a portrait taken in 1868 of his daughter-in-law Princess Alexandra carrying her daughter Louise on her back sold 300,000 copies.39 In the United States in 1863, Anthony and Company produced up to 3,600 celebrity photographs daily and had 4,000 subjects available.40 These weren’t just celebrities — they were profitable commodities.

In New Zealand, Māori represented home-grown celebrities, and many studios marketed them as such: John McGarrigle, J. Low, Monkton and the Pulman studio all advertised that they sold photographs of ‘Maori Celebrities’.41 Photographers were not inventing the idea of the Māori celebrity as a marketing tactic; they were tapping into the general attitude holding that important Māori, particularly chiefs, were celebrities. New Zealand newspapers abound with reports about ‘Māori celebrities’ and their activities. The events of the New Zealand Wars between Māori and the colonial government during the 1860s drew attention to the exploits of many individuals such as Tāwhiao and made them household names.42 In 1879, the New Zealand Herald claimed that the ‘most famous man in New Zealand’ was chief Rewi Maniapoto for his role in helping to bring peace to the country at the end of the war period.43 There was great consumer demand for putting a face to the name, and portraits of these celebrities were eagerly purchased.

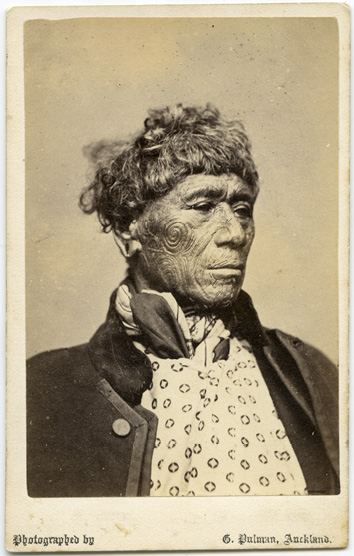

Portraits of Māori were one of the Pulman studio’s specialties. In 1864, a few years before setting up his own studio, George Pulman sold photographs of Māori taken by the Auckland studio of Fairs and Steel alongside European celebrities such as Shakespeare and Macauley.44 George established the Pulman studio in 1867 and continued selling portraits of Māori. One example marked ‘G. Pulman’ shows an elderly Māori chief with intricate moko (facial tattooing) (see Figure 2).45

Fig. 2 George Pulman, Māori Chief (ca. 1870), Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand, 19xx.2.3826.

In an 1879 advertisement, the Pulman studio boasted that it had on hand 2,000 ‘portraits of natives’ but listed only eighty views of Auckland, suggesting that the sale of Māori images was a particularly profitable aspect of the business.46 The studio was not alone in investing in a large stock of Māori images; in an insurance claim John McGarrigle placed for a fire that destroyed his studio in 1876, he claimed to have had 200 negatives and 31,000 mounted and unmounted Māori prints, which he supplied wholesale to shopkeepers at an average rate of 1,000 a month.47 During the 1880s when Tāwhiao’s portrait was taken, the Māori celebrity image market was fiercely competitive. In 1881 and 1882, the Pulman studio boldly asserted that it had the ‘greatest variety of Original Portraits of Maori Celebrities in New Zealand’.48 Thomas Price made a similar claim, advertising that he had the ‘Largest and Best Assortment of Maori Photographs in New Zealand’, while the Foy Brothers studio likewise asserted that it sold the ‘Best Collection of Maori Photos in New Zealand’.49

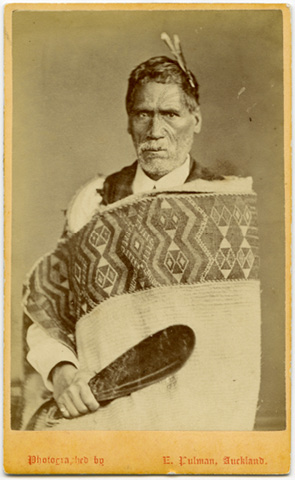

Monkton also advertised and sold photographs of Māori. In May 1881, he photographed Tāwhiao, his wife Hera, and other members of the royal family at a meeting of Māori at Whatiwhatihoe (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3 Charles Henry Monkton, Tāwhiao and his Wife Hera (1881), Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, Auckland, New Zealand, 589–4.

Four days after Monkton was charged with copyright infringement in 1882, he advertised that he was selling photographs from the Whatiwhatihoe meeting and stressed that they were ‘taken by me, and no other photographer’.50 His newspaper advertisement implied his innocence in the accusation by the Pulman studio and attempted to minimize the impact of the bad publicity he was receiving. However, a few weeks earlier, on August 11, he advertised ‘Photographs of King Tawhio and all the Maori Royal Family, from 3/ per dozen’, but there was no specific mention of the Whatiwhatihoe meeting.51 This likely alerted the Pulman studio to the possibility that Monkton was selling their image. On that day, Elizabeth’s son Frederick visited Monkton’s studio and purchased a copy of the portrait from Monkton’s wife, confirming the Pulman studio’s suspicion.52 On August 16, Monkton placed the advertisement a second time, prompting Blackman’s friend Mortimer Fairs to immediately visit the studio where he purchased more copies of Pulman’s photograph directly from Monkton.53

Photographs of Māori were not always regarded as celebrity images and, in fact, defy such neat classification. Ultimately, the viewer defined the image, and individual images could have multiple meanings depending on what viewers wanted to see. Teresa Zackodnik argues that with photographs of American abolitionist and activist Sojourner Truth, there is a discrepancy between Truth’s intentions with her image and the ‘uses and assumed meanings’ of her photographs by consumers.54 In her study of Eugéne Appert’s photographs of the French Communards of 1871, Jeannene M. Przyblyski points out the variety of interpretations possible from a single photograph of one of the men: a mother saw evidence of her son’s survival, police saw a suspect, and Parisians saw an infamous celebrity.55 Māori photographs also had many meanings and were simultaneously images of local celebrities, anonymous ethnographic type specimens, and everything in between. In his investigation of representations of Māori in photography and art, Roger Blackley argues that these images represent a variant of European orientalism and embodied a form of colonial fantasy.56 They were also, he points out, images that both celebrated colonialism and served as memorials for a dying Māori culture. Images of Māori in customary clothing were sought by some collectors as visual trophies and assembled into albums of ethnographic specimens. An album in the collection of Canterbury Museum compiled during the 1870s holds over two dozen of these portraits.57 Each has been carefully catalogued on the back with information such as ‘Te Mamaku a rebel native of Taranaki’ or more salacious details such as ‘The two native women who ate the heart and drank the blood of Revd Volkner missionary of Opotiki’.58A leather-bound example from the 1860s in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa features the title ‘New Zealand Chiefs’ in tooled gold lettering on the front cover.59 In addition to photographs of Māori, its compiler John Henry Eaton added images of Aboriginal Australians, Fijians, and views of Auckland. The desire for Māori photographs as examples of ethnographic types extended beyond New Zealand. In a letter to Canterbury Museum Director Julius Haast in 1873, Italian anthropologist Enrico Giglioni asks him to send some ‘good typical photographs of the New Zealand natives’ that he could use for ‘ethnological studies’.60 Recognizing this overseas demand, photography studios like George Hoby’s marketed Māori images for sending ‘home’, the term commonly used in New Zealand to refer to Great Britain.61 But people overseas did not have to wait for New Zealanders to send them photographs of Māori; celebrity image publishers in England such as Marion & Co. also stocked ‘New Zealand Chiefs’.62

Collecting images of Māori strictly as ethnographic specimens seems to have been a limited practice in New Zealand. Images of Māori are usually encountered in Victorian photograph albums alongside the compiler’s family and friends, suggesting that their meaning was more about curiosity and whimsy — and closer to celebrity — than scientific specimen. Priscilla Smith, daughter of a New Zealand businessman and wife of a sheep station owner, included four photographs of Māori in her family album among her visual menagerie that included Hawai’ian royalty, Peruvian veiled women, the dwarf couple General Tom Thumb and Lavinia Warren, and a portrait of Abraham Lincoln.63 Still others used photographs of Māori as sources of humor. In a letter written in 1877 from Tannie Fidler in New Zealand to her friend Georgy in Scotland, Tannie describes a joke she was planning to make at her sister’s expense with a photograph of Māori women: ‘There was a carte of four Maori ladies which I told Fanny I was going to send Robt as my young sister and three friends. She took it from me and crushed it all but I just put it in’.64

King Tāwhiao

During the case of Blackman v. Monkton, neither side called Tāwhiao as a witness, and missing from the court case was any consideration of him other than as the passive subject of the contested photograph. What was his standpoint on the making and circulation of his image? According to the New Zealand Fine Arts Copyright Act, the copyright of any work of art made for another person for ‘valuable consideration’ was not retained by the artist unless the commissioner agreed to it in writing to cede the copyright to the artist.65 If Tāwhiao had paid for his sitting and not transferred copyright to the studio, he would have been the one entitled to register his image under the Act. However, if this had been the case, Tāwhiao might not have been aware of his right to his image. Artists and others who stood to gain from copyright would have been familiar with the Act’s content but Tāwhiao, who lived in a remote, isolated Māori community and spoke te reo Māori as his first language, would have been less connected to European legal matters. It is possible that the studio took advantage of his ignorance and fraudulently registered itself as the copyright holder. Rather than commissioning their photographs, some nineteenth-century celebrities were instead paid by the studio for their visit, thus giving the photographer copyright and control of the image. Depending on their marketability, some notable sitters in the United States were paid between 25 and 1,000 dollars.66 Tāwhiao appears to have sat for his portrait for free. During the hearing, it was mentioned that it was common practice to take photographs of Māori celebrities without ‘pecuniary consideration’, suggesting that this had been the case with the King.67 If so, the Pulman studio, not Tāwhiao, was entitled to the copyright.

While Māori engaged with photography and visited studios to have their portraits taken, this was not the type of portrait that Tāwhiao would have commissioned for himself. It has all the hallmarks of one staged by a studio for the commercial market. Tāwhiao wears a finely woven flax cloak known as a kaitaka, but visible beneath it is his everyday clothing — the European-style shirt and cravat-like tie that he wore to the studio. By the 1880s when this photograph was taken, most Māori wore European-style clothing in their everyday life, and hundreds of studio portraits ordered by Māori show that they preferred everyday clothing rather than customary garments for their portraits. In fact, the cloak is not Tāwhiao’s but a prop owned by the Pulman studio that features in several other portraits it produced of Māori chiefs. Items such as cloaks and traditional weapons were standard items in studios that produced commercial images of Māori. Adorning a sitter with these accoutrements accentuated his or her ‘Māori-ness’ and created a more interesting, saleable image. Kaitaka like the one Tāwhiao wears have chiefly associations, and posing the King in it emphasized his royal status to viewers. However, he wears it incorrectly upside down so that the decorative, geometric-patterned taniko hem is visible in the frame and becomes a feature in the composition. Tāwhiao’s elaborate moko (facial tattooing) further increased the marketability of his image. Not only did it signify his chiefly status, this exotic cultural practice was also a great curiosity to Europeans. The wet plate collodion process that produced this photograph had difficulty picking up the blue and green shades of Māori tattoos, and as a result, photographers had to re-touch negatives to bring out the intricate designs chiselled into the sitter’s skin.68 The lines on Tāwhiao’s face have been re-drawn by the Pulman studio to make them visible.

Portraits of Māori staged in customary clothing similar to Tāwhiao’s were produced for a European market, but Māori were also consumers, and these images circulated in their world. For them, such photographs signified personal connections and cultural affiliation. On one of his visits to the Pulman studio, Tāwhiao viewed photographs of Māori chiefs and expressed his pleasure at seeing some old familiar faces such as Rewi Maniapoto, whom the studio had photographed in 1879, and he selected several photographs to take away.69 He also felt some nostalgia at seeing many of the chiefs he had known in his earlier days who had since died. Like the Europeans who collected ethnographic type images of Māori and other indigenous people as records of a dying race, late nineteenth-century Māori also recognized the period as one of twilight for their culture in the face of European modernization.70 Portraits such as Maniapoto’s and Tāwhiao’s captured and preserved their rapidly disappearing world.

Scholarship on photography of Māori has pointed to a degree of exploitation perpetrated by photographers. Michael Graham-Stewart and John Gow maintain that Māori were unable to control how they were depicted and photographers acted in their own commercial self-interest, and William Main describes Māori as being ‘commercially exploited’ by photographers such as John Nicol Crombie.71 While not denying the spectre of exploitation that would have been present in some situations, collaboration and agency marked the creation of much Māori visual representation. Unlike indigenous people in other colonial societies who lacked control over their image production, Māori had engaged with the European world since the early nineteenth century and had an understanding of photography.72 As clients and consumers, they were familiar with the production and distribution of images.73 They would also have been familiar with the commercial photographs that were displayed in studio windows as a form of advertising and public portrait gallery amusement.74 Literate Māori would have read newspaper advertisements for Māori photographs like Pulman’s and Monkton’s. One photography session was reported in detail in the Wellington Independent newspaper in 1866. High-ranking chief Wiremu Tāmihana Tarapīpipi Te Waharoa (known as the Kingmaker for his role in having Tāwhiao’s father declared the first Māori king) and his retinue visited Wellington to speak to the New Zealand Parliament and stopped at the Swan and Wrigglesworth studio for a sitting. In addition to having their portraits taken for personal use, the newspaper reported that ‘These Maoris have doffed the European costume, for the sake of effect, and shew themselves in “fighting trim” and “eager for the fray”’.75 For the commercial images the studio wanted to produce, the men posed as New Zealand warriors with traditional weapons and in clothing described as ‘purely Maori’. These images were added to the studio’s range of other local celebrities such as members of parliament who had recently honoured the studio with sittings. In 1879, chief Rewi Maniapoto had his portrait taken by the Pulman studio (see Figure 4), and he took away 50 copies to distribute, paid for by the government Native Office.76

Fig. 4 E. Pulman studio, Rewi Maniapoto (1879), Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand, 19xx.2.3828.

At a meeting later that year, he showed other chiefs his photograph. They offered their admiration at the image that was so lifelike, compliments that pleased Maniapoto.77 By the time Tāwhiao visited the Pulman studio in 1882, New Zealand photographers had been selling images of Māori celebrities commercially for nearly twenty years.78

Tāwhiao was no stranger to photographic studios, having had his portrait taken several times before visiting Pulman in 1882. He went to the studio twice in the days before his sitting, inspecting the photographs it stocked of Māori. In return, Elizabeth Pulman presented him with several photographs of chiefs, and he promised to return to the studio for a session, which he did on January 28. Having acquainted himself with the studio’s range of Māori photographs on his previous visits, it is clear that Tāwhiao co-operated in the production of his portrait. This is not to say that he had full agency with its composition; it is likely that George Steel, the photographer, staged the scene to produce a marketable commercial image. However, Tāwhiao had voluntarily come to the studio, and it was in the studio’s best interest to work collaboratively with him. In lieu of being paid for his sitting, it is likely that he was given copies of his photograph as Maniapoto had been.79

It was not just the studio that gained by this arrangement; Tāwhiao and other Māori sitters benefitted from the commercialisation of their images in several ways. Recent scholarship on the use of photography by African Americans during the nineteenth century has shown not only their agency but also their use of images to serve their cultural and political needs.80 Frederick Douglass was possibly the most photographed American in the nineteenth century, and he used the production and distribution of his image to craft his own public identity and change white perceptions of African Americans.81 It was a similar situation in New Zealand. The circulation of portraits of Māori chiefs helped to promote, enhance, and legitimize their chiefly status to European settlers and other Māori. This also helped strengthen their mana, the Māori concept of personal power and prestige that is an integral part of their culture. No doubt while looking at photographs of other chiefs at the Pulman studio, Tāwhiao envisaged his own photograph joining this respected group and bolstering his own mana. Such images could also be used for identity creation. Māori historian Michael Belgrave has described Tāwhiao’s own attempts at self-promotion, noting that his physical appearance was deliberately choreographed to reflect his ‘cultural and political objectives’.82 When Tāwhiao visited the Pulman studio in 1882, he had political motivation for crafting and disseminating his image. As the Māori King, he had been at the centre of the New Zealand Wars between Māori and the Crown in the 1860s and was declared a rebel by the New Zealand Colonial Government. In 1881, he and his followers capitulated, and Tāwhiao embarked on a public relations offensive to promote his new identity as a king willing to work with, rather than against, the Crown. His successful tour of Auckland had been to promote his leadership and demonstrate that war was in the past.83 Through the photographs it took of him, the Pulman studio facilitated Tāwhiao’s attempts at this personal reinvention. With his eyes averted from the camera, he is depicted as a peaceful, non-threatening man as opposed to other portraits of archetypal Māori warriors such as chief Tomika Te Mutu whose direct and defiant stare at the camera invites confrontation with the viewer (see Figure 5).

Fig. 5 John Nicol Crombie (attributed), Chief Tomika Te Mutu (ca. 1860), Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand, E161.50.

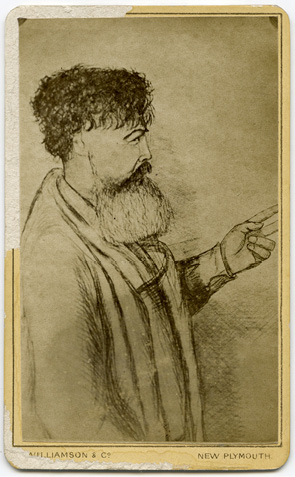

With regard to circulation, it is true that Māori celebrities lost control of their images, but this was not necessarily due to exploitation. Such loss of control was, in fact, a common situation for all celebrities. By the 1860s, photographs were infinitely reproducible, and market factors such as high demand and potential profit compelled photographers and others who sold photographs to capitalize on this. While many artists, actresses, politicians, and other celebrities found the widespread circulation of their images of professional benefit, not all were pleased at becoming a commodity that could be owned and gazed at by strangers. British artist Elizabeth Thomson, who skyrocketed to fame through her 1874 painting The Roll Call, was reticent about having her portrait taken and appalled when her aunt saw it in a costermonger’s barrow.84 For Māori, losing control of their image had deeper concerns. In Māori culture, the head is tapu (sacred) and its treatment follows strict cultural protocols. For some, seeing Queen Victoria’s head minted on coins was a dangerous practice, and having their own photograph taken for distribution was equally distressing.85 The pacifist prophet Te Whiti-o-Rongomai resisted having his photograph taken for many years, remarking once, ‘you never know how a photo may be treated; it may be reproduced on paper, and that paper may be put to most ignoble uses’.86 Artist William F. Gordon found a way around Te Whiti’s refusal. During a speech in 1880, he surreptitiously sketched the prophet on his shirt cuff and later re-drew the sketch and had it photographed (see Figure 6).87

Fig. 6 William F. Gordon (artist) and Williamson & Co. (photographer), Te Whiti-o-Rongomai (1880), Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand, E161.50.

It quickly made it into circulation. In 1875, Chief Rewi Maniapoto purchased photographs of chiefs from the studio of J. Low but refused to have his taken because he thought it improper for a chief’s image to be sold. He relented a few years later and posed for the Pulman studio, among others.88 Tāwhiao, as discussed above, found personal advantage in having his photograph taken and in 1884 even put his own image into circulation when he passed it on for presentation to the Belgian King.89 Reconciling traditional attitudes with the advantages of photography had been a gradual but inevitable process for Māori during the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

The case of Blackman v. Monkton tested the ability of the New Zealand Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 to protect registered photographs from pirating, and revealed loopholes that left the legislation weak and ineffective. These were partly rectified by the Photographic Copyright Bill 1896 with its stronger means of demonstrating copyright through inscription. However, there was more to the case than testing the law. An examination of the context surrounding it reveals factors relating to image production and circulation in New Zealand that drove the Pulman studio to register their photographs and take Monkton to court. Commercial interests were at the heart of the case with both sides trying to capitalize on the profits from the portrait of Tāwhiao. Māori were New Zealand celebrities whose faces had commercial value, and photography studios were in fierce competition with each other for a piece of that market. Although not included in the courtroom proceedings, Tāwhiao was a key player in the matter. The creation of his image required his collaboration, as was the case with many commercial portraits of Māori in New Zealand. However, his involvement was more than simply co-operation with the studio to produce a commercial photograph for them. He recognized the value of his portrait for serving his own cultural and political interests.

Bibliography

Archives and Museums

Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand.

Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Primary Sources

All the Year Round (London).

Auckland Star.

Daily Southern Cross (Auckland).

New Zealand Herald (Auckland).

New Zealand Mail (Wellington).

New Zealand Times (Wellington).

Otago Daily Times.

Taranaki Herald.

Thames Advertiser.

The Photographic News (London).

Waikato Times.

Wairarapa Daily Times.

Wellington Independent.

Legislation

New Zealand Copyright Act 1842 (5 Victoriae No 18), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/ca18425v1842n18253/.

New Zealand Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 (41 Victoriae 1877 No 17), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/faca187741v1877n17337/.

New Zealand Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 Amendment Act 1879 (43 Victoriae No.35), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/faca1877aa187943v1879n35438/.

New Zealand Photographic Copyright Bill 1896 (89–3), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_bill/pcb1896893267/.

Secondary Sources

Belgrave, Michael, Dancing with the King: The Rise and Fall of the King Country, 1864–1885 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2017).

Biddle, Donna-Lee, ‘Wet-plate Photography and the Resurgence of Tā Moko’, https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/106652213/wetplate-photography-and-the-resurgence-of-t-moko.

Blackley, Roger, Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880–1910 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2018).

Bowrey, Kathy, ‘“The World Daguerreotyped — What a Spectacle!” Copyright Law, Photography and Commodification Project of Empire’, conference paper presented at the Third International Society for the History and Theory of Intellectual Property (ISHTIP) Workshop, Griffith University, 5–6 July 2011.

Cobb, Jasmine Nichole, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

Cooper, Elena, Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Deazley, Ronan, ‘Breaking the Mould? The Radical Nature of the Fine Arts Copyright Bill 1862’, in Privilege and Property: Essays on the History of Copyright, ed. by Ronan Deazley, et al. (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2010), pp. 289–320, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0007.

——, ‘Struggling with Authority: The Photograph in British Legal History’, History of Photography, 27 (2003), 236–246, https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2003.10441249.

Di Bello, Patrizia, ‘Elizabeth Thompson and “Patsy” Cornwallis West as Carte-de-visite Celebrities’, History of Photography, 35 (2011), 240–249, https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2011.592406.

Giles, Keith, ‘Fairs and Steel: Their Impact on Auckland Photography’, New Zealand Legacy, 19 (2007), 8–12.

——, ‘The Problematic Portraits of Pomare II’, New Zealand Memories, 26 (2014), 20–21.

Goldberg, Vicki, The Power of Photography: How Photographs Changed our Lives (New York: Abbeville Press, 1991).

Graham-Stewart, Michael and John Gow, Negative Kept: Maori and the Carte de Visite (Auckland: John Leech Gallery, 2013).

Hearn, Alison, ‘”Sentimental Greenbacks of Civilization”: Cartes de Visite and the Pre-History of Self-Branding’, in The Routledge Companion to Advertising and Promotional Culture, ed. by Matthew P. McAlister and Emily West (New York: Routledge, 2013), pp. 24–38, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203071434.

Marcus, Sharon, The Drama of Celebrity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc772z0.

McLay, Geoff, ‘New Zealand and the Imperial Copyright Tradition’, in A Shifting Empire: 100 Years of the Copyright Act 1911, ed. by Uma Suthersanen and Ysolde Gendreau (Cheltenham: Edward Edgar, 2013), pp. 30–51, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781003091.00007.

McCauley, Elizabeth Anne, A. A. E. Disdéri and the Carte de Visite Portrait Photograph (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985).

——, Industrial Madness: Commercial Photography in Paris, 1848–1871 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

Main, William, Maori in Focus: A Selection of Photographs of the Maori from 1850–1914 (Wellington: Millwood Press, 1976).

Mole, Tom, Byron’s Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutic of Intimacy (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230288386.

Murray, Hannah-Rose, ‘A “Negro Hercules”: Frederick Douglass’ Celebrity in Britain’, Celebrity Studies, 7 (2016), 264–79, https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1098551.

New Zealand History, ‘Carl Völkner’, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/carl-volkner.

Plunkett, John, ‘Celebrity and Community: The Poetics of the Carte de Visite’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 8 (2003), 55–79.

——, ‘Celebrity Culture’, in The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Literary Culture, ed. by Juliet John (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 539–60, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199593736.013.21.

——, Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Poole, Debra, Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

Pōtiki, Megan, ‘Me Tā Tāua Mokopuna: The Te Reo Māori Writings of H. K. Taiaroa and Tame Parata’, New Zealand Journal of History, 49 (2015), 31–49.

Pritchard, Michael, ‘Edward Anthony and Henry Tiebout’, in Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, ed. by John Hannavy (New York: Routledge, 2008), pp. 48–50, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203941782.

Przyblyski, Jeannene M, ‘Loss of Light: The Long Shadow of Photography in the Digital Age’, in The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies, ed. by Robert Kolker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 158–186, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195175967.013.0006.

Stauffer, John, et al., Picturing Frederick Douglass (New York: Liveright, 2015).

Wallace, Maurice O. and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds., Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394563.

Whybrew, Christine, ‘The Burton Brothers Studio: Commerce in Photography and the Marketing of New Zealand, 1866–1898’ (unpublished Doctoral thesis, University of Otago, 2010).

Zackodnik, Teresa, ‘The “Green-Backs of Civilization”: Sojourner Truth and Portrait Photography’, American Studies, 46 (2005), 117–143.

1 Māori are the indigenous people of New Zealand. Historically tribal, most prefer to identify themselves with their iwi (tribal) name rather than the generic term ‘Māori’. Not all tribes recognized Tāwhiao as king, and his influence was limited to a region of New Zealand’s North Island.

2 New Zealand Herald (Auckland), 20 January 1882, p. 6.

3 The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa holds the original glass plate negative as well as several copies of the photograph.

4 Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 (41 Victoriae 1877 No 17), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/faca187741v1877n17337/. For a discussion of the British Fine Arts Copyright Act, see Ronan Deazley, ‘Breaking the Mould? The Radical Nature of the Fine Arts Copyright Bill 1862’, in Privilege and Property: Essays on the History of Copyright, ed. by Ronan Deazley et al. (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2010), pp. 289–320, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0007. For a discussion of photography and copyright in Britain, see also Ronan Deazley, ‘Struggling with Authority: The Photograph in British Legal History’, History of Photography, 27 (2003), 236–246 (p. 236), https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2003.10441249. For more on the background of New Zealand’s Fine Art Copyright Act 1877, see Geoff McLay, ‘New Zealand and the Imperial Copyright Tradition’, in A Shifting Empire: 100 Years of the Copyright Act 1911, ed. by Uma Suthersanen and Ysolde Gendreau (Cheltenham: Edward Edgar, 2013), pp. 30–51, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781003091.00007.

5 Books were protected by copyright in New Zealand through an ordinance passed in 1842. Copyright Act 1842 (5 Victoriae No 18), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/ca18425v1842n18253/.

6 Evening Post (Wellington), 5 July 1875, p. 2.

7 Christine Whybrew, ‘The Burton Brothers Studio: Commerce in Photography and the Marketing of New Zealand, 1866–1898’ (Doctoral thesis, University of Otago, 2010), p. 81.

8 It is not known whether Elizabeth Pulman was a photographer. It is likely that she, like many wives of photographers during the period, assisted in the studio. Keith Giles posits that when Elizabeth’s husband died, family friend and professional photographer George Steel stepped in to assist her. It is possible that Elizabeth owned the business while Steel operated the camera. Keith Giles, ‘Fairs and Steel: Their Impact on Auckland Photography’, New Zealand Legacy, 19 (2007), 8–12.

9 The registrations for the years 1877 to 1886 were lost in a fire in 1952 that destroyed numerous public records.

10 Daily Southern Cross (Auckland), 9 June 1871, p. 2.

11 Auckland Star, 10 June 1871, p. 2.

12 No examples of Monkton’s version of the portrait of Tāwhiao have been located. This is not surprising given the short amount of time that he was pirating it and the small number that would probably have made it into circulation.

13 Cotter’s first name was never mentioned in any of the news reports. New Zealand Herald, 11 September 1882, p. 5.

14 New Zealand Herald, 21 August 1882, p. 3.

15 Auckland Star, 16 September 1882, p. 2; New Zealand Herald, 7 September 1882, p. 3.

16 Auckland Star, 9 September 1882, p. 2. Although not expressly stated, Monkton was also in breach of Section 7 which outlined the actions considered fraudulent with regards to copyrighted works.

17 Taranaki Herald, 11 September 1882, p. 2. For newspaper summaries of the case, see Auckland Star, 9 September 1882, p. 2; New Zealand Herald, 11 September 1882, p. 5.

18 The report in the Auckland Star incorrectly states that it was February 28. Auckland Star, 9 September 1882, p. 2.

19 New Zealand Herald, 11 September 1882, p. 2. Fairs was the son of Thomas Armstrong Fairs, a photographer and associate of George Pulman in the 1860s.

20 Cartes de visite are paper photographs mounted on card backings measuring approximately 60 mm by 90 mm, roughly the size of a Victorian visiting card. They became the standard form for photographic portraiture throughout the 1860s. Larger format cabinet cards measuring approximately 110 mm by 165 mm appeared after 1870. Both formats were used during the 1870s and 1880s, but cabinet cards had largely replaced cartes de visite by 1890.

21 Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877, s. 5.

22 Auckland Star, 16 September 1882, p. 2.

23 Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877 Amendment Act 1879 (43 Victoriae No. 35), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/faca1877aa187943v1879n35438/.

24 New Zealand Times (Wellington), 19 March 1880, p. 2.

25 Gillon v. De Lias, New Zealand Mail (Wellington), 8 May 1880, p. 18; Gillon v. Lucas, Evening Post, 20 May 1880, p. 2; Gillon v. Geddes, New Zealand Herald, 31 August 1880, p. 5.

26 Photographic Copyright Bill 1896 (89–3), http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_bill/pcb1896893267/.

27 Kathy Bowrey, ‘”The World Daguerreotyped — What a Spectacle!” Copyright Law, Photography and Commodification Project of Empire’, conference paper presented at the Third International Society for the History and Theory of Intellectual Property (ISHTIP) Workshop, Griffith University, 5–6 July 2011; Elena Cooper, Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

28 For a discussion of the British system of registrations, see John Plunkett, ‘Celebrity and Community: The Poetics of the Carte de Visite’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 8 (2003), 55–79 (p. 63), https://doi.org/10.3366/jvc.2003.8.1.55.

29 Whybrew, p. 83.

30 Auckland Star, 28 January 1882, p. 3; New Zealand Herald, 30 January 1882, p. 1.

31 Auckland Star, 28 January 1882, p. 3.

32 John Plunkett, ‘Celebrity Culture’, in The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Literary Culture, ed. by Juliet John (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 539–560, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199593736.013.21.

33 Tom Mole, Byron’s Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutic of Intimacy (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), p. 1, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230288386. See also Plunkett, ‘Celebrity Culture’, p. 540; Hannah-Rose Murray, ‘A “Negro Hercules”: Frederick Douglass’ Celebrity in Britain’, Celebrity Studies, 7 (2106), 264–279 (p. 265), https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1098551.

34 Sharon Marcus, The Drama of Celebrity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), p. 4, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc772z0.

35 For classic works on the development of commercial photography and the emergence of celebrity images, see Elizabeth Anne McCauley, A. A. E. Disdéri and the Carte de Visite Portrait Photograph (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985); Elizabeth Anne McCauley, Industrial Madness: Commercial Photography in Paris, 1848–1871 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

36 ‘Cartes de Visite’, reprinted in Otago Daily Times, 22 April 1862, p. 5.

37 Ibid.

38 John Plunkett, Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 153.

39 Otago Daily Times, 22 April 1862, p. 5; The Photographic News, 29 (1885), 136.

40 Vicki Goldberg, The Power of Photography: How Photographs Changed our Lives (New York: Abbeville Press, 1991), p. 105; Michael Pritchard, ‘Edward Anthony and Henry Tiebout’, in Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, ed. by John Hannavy (New York: Routledge, 2008), pp. 48–50 (p. 50), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203941782.

41 Auckland Star, 19 February 1873, p. 2; Waikato Times, 17 May 1877, p. 1; Taranaki Herald, 24 April 1883, p. 3; Auckland Star, 26 July 1881, p. 3.

42 The New Zealand Wars were a series of armed conflicts between some Māori tribes and the New Zealand government over land rights and sovereignty from 1845 to 1872, peaking in the 1860s.

43 New Zealand Herald, 28 May 1879, p. 5; 30 May 1879, p. 5.

44 Daily Southern Cross, 13 January 1864, p. 2. Macauley was Thomas Babbington Macauley, First Baron Macauley, a well-known nineteenth-century British historian and politician.

45 This portrait has been incorrectly identified as Ngāti Manu leader Whētoi Pōmare (Whiria). However, Pomare died in 1850 before Pulman could have taken his portrait. For a fuller discussion, see Keith Giles, ‘The Problematic Portraits of Pomare II’, New Zealand Memories, 26 (2014), 20–21.

46 Auckland Star, 2 January 1879, p. 4.

47 New Zealand Herald, 17 January 1877, p. 3.

48 Auckland Star, 27 July 1881, p. 3.

49 Wairarapa Daily Times, 8 June 1881, p. 3; Thames Advertiser, 21 December 1883, p. 2.

50 Auckland Star, 28 August 1882, p. 3.

51 Auckland Star, 11 August 1882, p. 3.

52 Auckland Star, 9 September 1882, p. 2.

53 Auckland Star, 16 August 1882, p. 3; Auckland Star, 9 September 1882, p. 2.

54 Teresa Zackodnik, ‘The “Green-Backs of Civilization”: Sojourner Truth and Portrait Photography’, American Studies, 46 (2005), 117–143 (p. 119).

55 Jeannene M. Przyblyski, ‘Loss of Light: The Long Shadow of Photography in the Digital Age’, in The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies, ed. by Robert Kolker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 158–186 (p. 166), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195175967.013.0006.

56 Roger Blackley, Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880–1910 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2018).

57 Canterbury Museum, Album 213, E161.50.

58 In 1865, during the New Zealand Wars, German missionary Carl Sylvius Völkner was executed by the Te Whakatōhea tribe for acting as a spy for the British government. New Zealand History, ‘Carl Völkner’, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/carl-volkner.

59 Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, AL000208, https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/575310.

60 Canterbury Museum, related documents, EA1988.

61 Taranaki Herald, 21 July 1866, p. 2.

62 Michael Graham-Stewart and John Gow, Negative Kept: Maori and the Carte de Visite (Auckland: John Leech Gallery, 2013), p. 189.

63 Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, Album 8, 1959/20/43.

64 Tannie Fidler to Georgy, 1877, Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, AG-305.

65 According to Section 2 of the Fine Arts Copyright Act 1877, works of art ‘made or executed for or on behalf of any other person for a good or valuable consideration, the person so selling or disposing of or making or executing the same, shall not retain the copyright thereof, unless it be expressly reserved to him by agreement in writing, signed at or before the time of such sale or disposition by the vendee or assignee thereof’.

66 Alison Hearn, ‘”Sentimental Greenbacks of Civilization”: Cartes de Visite and the Pre-History of Self-Branding’, in The Routledge Companion to Advertising and Promotional Culture, ed. by Matthew P. McAlister and Emily West (New York: Routledge, 2013), pp. 24–38 (p. 33), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203071434.

67 New Zealand Times, 11 September 1882, p. 2.

68 Donna-Lee Biddle, ‘Wet-plate Photography and the Resurgence of Tā Moko’, https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/106652213/wetplate-photography-and-the-resurgence-of-t-moko.

69 Auckland Star, 20 January 1882, p. 3.

70 See Blackley for further information.

71 Graham-Stewart and Gow, p. 190; William Main, Maori in Focus: A Selection of Photographs of the Maori from 1850–1914 (Wellington: Millwood Press, 1976), p. 5.

72 Debra Poole’s work on photography in Peru is one study that examines the unequal power relations between photography studios and their indigenous sitters. Debra Poole, Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997). For a discussion of Māori and modernity, see Megan Pōtiki, ‘Me Tā Tāua Mokopuna: The Te Reo Māori Writings of H. K. Taiaroa and Tame Parata’, New Zealand Journal of History, 49 (2015), 31–49.

73 Museum and archival collections in New Zealand hold hundreds of privately commissioned studio portraits of Māori that attest to their engagement with photography.

74 ‘Looking in at Shop Windows’, All the Year Round, 12 June 1869, pp. 42–43.

75 Wellington Independent, 28 August 1866, p. 5.

76 Auckland Star, 21 June 1879, p. 2; New Zealand Herald, 11 December 1879, p. 6.

77 Auckland Star, 26 June 1879, p. 2.

78 The first newspaper advertisement found for Māori photographs is George Pulman’s from 1864, a few years after cartes de visite were introduced in New Zealand and around the time that celebrity cartes became popular. Daily Southern Cross, 13 January 1864, p. 2.

79 Some Māori were paid models for commercial portraits by painters. Pātara Te Tuhi was reportedly paid eight shillings a day by artist Charles Goldie in 1901 for his sitting. Blackley, p. 100.

80 Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2015); Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds., Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394563.

81 John Stauffer et al., Picturing Frederick Douglass (New York: Liveright, 2015); Murray, 264–279.

82 Michael Belgrave, Dancing with the King: The Rise and Fall of the King Country, 1864–1885 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2017), p. 431.

83 Belgrave, p. 198.

84 Patrizia di Bellow, ‘Elizabeth Thompson and “Patsy” Cornwallis West as Carte-de-visite Celebrities’, History of Photography, 35 (2011), 240–249, https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2011.592406.

85 Blackley, p. 163.

86 Quoted in Blackley, p. 164.

87 New Zealand Herald, 16 July 1928, p. 14.

88 Blackley, p. 172; Taranaki Herald, 11 September 1875, p. 2.

89 New Zealand Herald, 17 September 1884, p. 5.