3. Who Owns Washington? Gilbert Stuart and the Battle for Artistic Property in the Early American Republic

© 2021 Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0247.03

‘Meaningless, inconsistent, and inadequate’: this is how Eaton Drone evaluated the legal provisions that emerged from US-American and British intellectual property law and jurisprudence in 1879.1 Published a few years after the 1870 statute that granted copyright protection to paintings for the first time in the United States, Drone’s innovative treatise on intellectual property regarded past British and US-American judicial decisions as ambiguous at best, and more often incompatible with the general principles of property in intellectual production that he formulated in this volume. Founded on the notion that property was a natural right fundamentally connected to labor — ’what a man creates by his own labor, out of his own materials, is his to enjoy to the exclusion of all others’ — Drone defined intellectual property as the product of intellectual labor, no matter the medium; he argued that it was found in various travails of the mind, from literary production to drama, music, sculpture and painting.2 Grounded in Enlightenment philosophy, Drone’s definition of intellectual property has been understood as a result of the broadening of the notion of authorship beyond the written word, which has been seen as the driving force behind the belated integration of the fine arts in American copyright law in the act of 1870.3

The equivalence between painting and literary creation was not new; it was a concept fundamental to European and American cultures, rooted in Horace’s famous phrase ‘Ut pictura poesis’, literally meaning ‘as is painting, so is poetry’. Since the Renaissance, numerous treatises on art and literature have repeatedly remarked on the close relationship between ‘the sister arts’, as they were called.4 Artists, writers, and patrons alike invoked Horace’s phrase to raise the status of painting as a liberal art, and that of their creator above the status of a craftsman. This argument had become particularly influential in eighteenth-century British art. Furthermore, it found a fertile ground in the early nineteenth-century United States, where the trope of the self-taught artistic genius asserted national authority, not only over Britain, but also over European culture at large.5

In spite of a broad consensus on the kinship between literature and painting in artistic and literary circles, the equivalence between painting and literary creation posed certain difficulties when presented as an argument to legislators, or when used as legal evidence in court, even after the United States Congress extended copyright protection to paintings.6 When, in 1801 and 1802, Congress considered the inclusion of visual works in the revisions of the copyright statute of 1790, painters did not lobby en masse to request the addition of paintings to the list of images that could benefit from protection under the new statute.7 The US Copyright Act of 1802, specifically aimed at encouraging the visual arts, did not include them, limiting itself instead to the ‘arts of designing, engraving and etching historical and other prints’.8 In spite of this limitation, the famous painter Gilbert Stuart went to court against a sea captain who had commissioned unauthorized copies of one of his portraits of George Washington only a couple of weeks after the publication of the new statute, and won his case in court — seemingly substantiating Drone’s statement that, by and large, US-American law was marked by a series of erroneous or conflicting decisions.

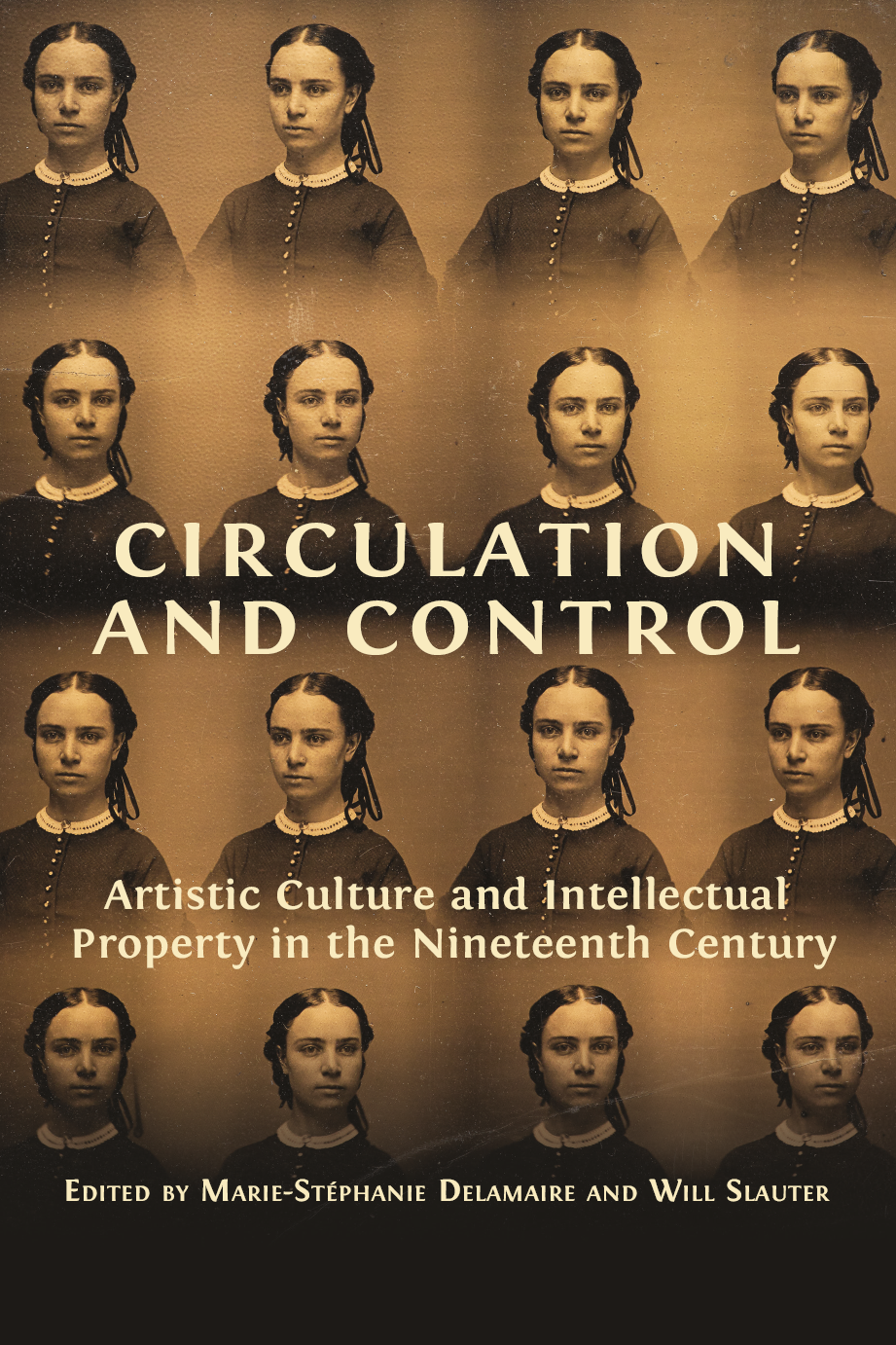

Fig. 1 Anonymous artist after Gilbert Stuart, Portrait of George Washington (1801), reverse painting on glass, 1960.0569 A, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

Court cases relating to intellectual property and the visual arts were the exception rather than the norm in the nineteenth-century United States. The Stuart v. Sword case is the first among a handful for the entire period covered in this book. It registers a moment of uncertainty: one when an artist asked the court for clarification about an object that was not addressed in the statute, and a moment when other artists and print publishers asserted intangible property rights on visual works, whether these could be backed by statute and jurisprudence, or not. Starting with Stuart v. Sword, this chapter examines how various constituencies in the early decades of the American Republic envisioned the nature of artistic property in a painting, even as it remained outside the realm of statutory protection. I investigate how painters and their patrons, publishers, and dealers came to conceptualize a notion of intellectual property in a painting, and how they, together with their lawyers and judges, articulated this notion either in court or in artistic and trade practices. What kind of property did various constituents think they had when they created or owned a picture? What happened to this property when the artwork was sold or given? Under what conditions could it be copied or reproduced in various media? The notion that painters owned artistic property in the product of their creative genius, separate from its physical utterance in the painting, was, I argue, fundamental to Stuart’s decision to seek legal advice and go to court. The concept emerged from the synergy between artistic discourse and practices in the print trade that developed in the art world of London, where Stuart first became a successful and highly regarded artist.

Nevertheless, it did not open a clear legal path for painters’ claims to control that property, as it was transformed by reproduction and circulated away from their studio. Neither did it facilitate the enactment of statutory protection for paintings in the United States. The present essay examines these apparent contradictions to understand how, in the absence of statutory protection, American artists reconciled an intellectual conception of artistic property — formulated through academic art theory and practices that flourished in Europe in the eighteenth century — with the new visual media landscape and transnational art market that emerged in the United States during the early decades of the nineteenth century.

Stuart v. Sword: Controlling Copying in Early Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia

Gilbert Stuart, born in 1755 in Newport, Rhode Island and the son of a snuff maker, showed an early talent for drawing. After working for a few years as a portrait painter in Rhode Island and other American colonies, the aspiring artist moved to London in 1775, where he entered the studio of American-born painter Benjamin West. West was a rising star in the London art world, a founding member of the Royal Academy, and historical painter to the court. Stuart was soon immersed in some of West’s artistic projects that connected him to John Boydell (1719–1804), the foremost London art publisher. Boydell and West’s recent collaboration in the publication of an engraving after the painter’s The Death of General Wolfe (1776) has been credited with inaugurating a new era of patronage and popularity for English historical pictures9 (see Figure 5). After Stuart exhibited his first full-length portrait, representing William Grant and titled Portrait of a Gentleman Skating at the Royal Academy in 1782 — a painting that brought him widespread recognition — Boydell commissioned Stuart with fifteen portraits of prominent living artists, including that of William Woollett, the engraver of The Death of General Wolfe (see Figure 2).10

Fig. 2 Gilbert Stuart, Portrait of William Woollett (1783), oil on canvas, Tate Britain. Image by The Athenaeum, Wikimedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Woollett_by_Gilbert_Stuart_1783.jpeg.

Three portraits from the series were also integrated into Boydell’s exhibition of John Singleton Copley’s enormously popular picture, The Death of Major Peirson (also a Boydell commission), when the painting was on public view at No. 28, Haymarket, and later in the publisher’s skylighted gallery: ‘Three ovals on the top of the frame, in the center of which is Mr. Copley’s portrait, painted by that able artist Mr. Stuart. The portrait of Mr. Heath, who is to engrave the subject on one side, and that of Mr. Joshua Boydell, who is to make the drawing [to be used as model for the engraving] on the other.’11

In London, Stuart maintained an extravagant lifestyle, which put him into an increasingly serious amount of debt. Threatened by the dismal state of his financial affairs, the artist fled first for Ireland and later for America, where he arrived in 1794 with the explicit goal of regaining financial stability by painting George Washington. ‘There [in America] I expect to make a fortune by Washington alone. I calculate upon making a plurality of his portraits […]; and if I should be fortunate, I will repay my English and Irish creditors.’12 Known for his provocative personality, Stuart openly professed to dislike anything else than portraiture: an attitude that won him broad support and patronage in the United States. With numerous commissions for the anticipated portrait, and a letter of introduction from lawyer, statesman, and writer John Jay, Stuart arrived in Philadelphia in November of 1795 to paint the first president. This first sitting resulted in the Vaughan portrait type (after Samuel Vaughan, one of the artist’s patrons who had commissioned a copy in anticipation of its completion): a waist-length portrait showing the right side of Washington’s face (see Figure 3).

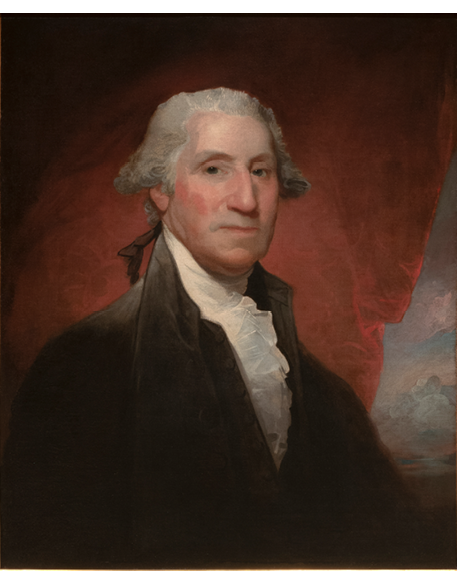

Fig. 3 Gilbert Stuart, Portrait of George Washington (1795–1796), oil on canvas, 1957.0857, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

Washington sat for the artist a second time the following year. The portrait that resulted from this April 12, 1796 sitting, also waist-length, was left unfinished, but served as a model for about one hundred subsequent likenesses of Washington painted by Stuart over the next two decades. The second composition is called the Athenaeum type because the original unfinished portrait made during Washington’s sitting was purchased by the Boston Athenaeum soon after the painter’s death in 1828. All of the Athenaeum-type portraits of the first president were painted on a standard English canvas size of about 25 by 30 inches, known as ‘three-quarter length’. Finally, Stuart painted a third type, the portrait of Washington in full length, called the Lansdowne portrait. It was commissioned for Lord Lansdowne by William Bingham, a Philadelphia merchant, in 1796. This portrait was also based on the April 1796 sitting and shows the left side of the president’s face13 (see Figure 4).

Painting Washington’s portrait proved to be the very successful business Stuart had hoped for: In 1795, he wrote a list of thirty-nine patrons for his Washington portraits, and we know that he was selling the smaller portraits of the Athenaeum type for about $150 a piece, a significant sum for the period.14 For the commission of the large full-length type, he received $1,000 from William Bingham, who intended it as a gift to the Marquis of Lansdowne, Britain’s Prime Minister during the final months of the American Revolutionary War, who had secured peace with the United States. It is no wonder that the landing of the Connecticut in Philadelphia on April 3, 1802, with ‘above one hundred’ full-size Athenaeum-type portraits painted on glass in China, felt like a major threat to the painter’s flourishing business. The captain of the Connecticut, John Sword, had purchased a portrait of Washington directly from Stuart a year earlier. Active in the Atlantic and the China Sea since the 1780s, Sword had taken the painting to Guangzhou where he commissioned the 100 copies. Returning from East Asia, he imported the Chinese copies among the three trunks of personal property listed in the manifest of the Connecticut on his arrival.15

These copies of Stuart’s Washington were made using the popular Chinese technique of reverse paintings on glass. Such paintings were prize Chinese export artifacts that had been circulating throughout the British Empire since the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Even though such imports represented a small percentage of the US-China trade, they were popular between the 1780s and the first decade of the nineteenth century, just as a new trend in this type of painting emerged: the copying of European and American prints. Large reverse paintings on glass were luxury goods. Likely one of the portraits that survived the Stuart v. Sword lawsuit, the beautifully crafted Chinese replica of Stuart’s painting currently in the Winterthur Museum collection, is a full-size copy of the original work painted on a 25 by 30 sheet of glass (see Figure 1). Considering its fragile medium, it is in remarkable condition. Such large-size paintings would have cost Captain Sword at least $15 to $20 a piece, and represented a significant investment on Sword’s part (if he acted alone in this enterprise).16 Since the portraits on glass were never advertised, we do not know how much Sword intended to sell them in Philadelphia. His investment, however, was certainly calculated to bring a handsome return. Although it is unlikely that they would have reached the price of one of Stuart’s own Athenaeum copies, they would nevertheless have not come close to the price of an engraving. At that time, the painter was also investing into the engraved reproduction of his painted portraits of Washington. He advertised plans to produce his own engraving of the full-length portrait, which he intended to sell for $20: quite an expensive price for a reproductive print in the United States.17 The medium of Chinese reverse painting on glass associated Sword’s unauthorized copies with sumptuous exotic goods. Their materiality would have prevented any collector from mistaking them for Stuart’s original paintings. Yet, their size and association with luxury goods would have made them a much closer equivalent to Stuart’s paintings than the large (unauthorized) print of the Lansdowne portrait engraved by James Heath, also offered for sale in Philadelphia at the time. The Chinese copies of Stuart’s painting on glass were bound to become direct competitors of Stuart’s own paintings, on the expansive market of painted likenesses of the American Republic’s founding father.

On May 14, 1802, Stuart filed a lawsuit against Captain Sword in the District Court of Pennsylvania. The artist was still a British citizen in 1802, and he filed the lawsuit in the Federal District Court rather than in the State Court.18 The bill explained that the portrait had been sold to the buyer with specific restrictions regarding the buyer’s right to have the painting copied. Stuart explained the conditions of the sale, and its restrictions on copying without giving details as to the medium in which the painting might or might not be copied:

Your orator thereupon refused to sell the same [the portrait of George Washington] unless the said John E. Sword would promise your orator that no copies should be taken thereof, whereupon the said John E. Sword did promise and assure your orator that no copies thereof should be taken and the better to prevail on your orator to sell him the same, the said John E. Sword alleged and pretended to your orator that he wanted the same for a gentleman in Virginia, whereupon your orator giving faith to his said promise and assurance did sell and deliver to him the said portrait of General Washington.19

Stuart filed his suit barely a couple of weeks after President Jefferson signed the supplementary act that expanded the reach of copyright statutory protection to printed images, but not to paintings. Nevertheless, Stuart went to court and requested that Sword not only ‘be enjoined and restrained from vending or […] disposing of any of the said copies’ but also that he ‘may be ordered to deliver us all that remain unsold or otherwise dispose of them’. The Court’s injunction, issued the same day against the defendants, went beyond the remedies available at common law, demanding not only that Sword cease selling the unauthorized copies, but that he also have them ready for the Court’s further instructions — suggesting forthcoming seizure or destruction. While the lawsuit is a relatively obscure case of jurisprudence, it is well-known among historians of US-American art, for whom it largely represents an example of early art fraud. The case is also seen as evidence of Stuart’s preoccupation with profiting from the market in reproductions of his paintings.20

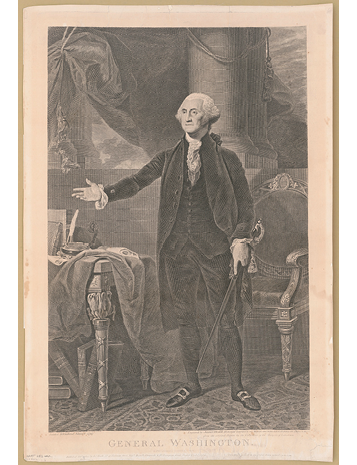

It was not the first time Stuart asserted a right to control the production and circulation of images copied after his paintings. Before his dispute with Sword, Stuart had publicly claimed an intangible property in his full-length portrait of George Washington commissioned by William Bingham for Lord Lansdowne. This property gave the painter — Stuart insisted — the authority to control the publication of the painting long after its delivery to Bingham in Philadelphia, and to its final recipient, Lord Lansdowne in Britain. Unfortunately for the artist, however, Stuart discovered that a stipple engraving after his portrait, made by the well-known British engraver James Heath, was offered for sale in Philadelphia (see Figure 4).

Fig. 4 James Heath after Gilbert Stuart, Portrait of George Washington (1800), engraving, Library of Congress, Photographs and Prints Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004667280/.

In order to defend what he articulated as an intangible property in his own artistic creation, Stuart stated in a letter to the press that Heath’s engraving had not been authorized. In a breach of trust, Bingham had not obeyed the painter’s specific instructions, that — when delivering the painting — Bingham was to reserve for the painter the right to publish the portrait in print. Dismayed to see an English print after his work for sale in Philadelphia, the artist mounted a public campaign against this unauthorized print:

Mr. Stuart has the mortification to observe, that without any regard to his property, or feelings, as an Artist, an engraving had recently been published in England; and is now offered for sale in America, copied from one of his Portraits of Gen. Washington. Though Mr. Stuart cannot but complain of this invasion of his Copy-right (a right always held sacred to the Artist, and expressly reserved on this occasion, as a provision for a numerous family) he derives some consolation from remarking, that the manner of executing Mr. Heath’s engraving, cannot satisfy or supercede [sic.] the public claim, for a correct representation of the American patriot.21

In claiming his right to reserve publication for the painter, Stuart was following well-established practices in Britain. The painter’s preoccupations with controlling copying, and with reaping the benefits of adapting one’s painting in print tied him to the London art world where he trained, and where his peers Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley developed strategies and formed alliances with engravers and the leading publisher John Boydell to control the publication and circulation of their paintings in print. His use of the term ‘property’ and ‘copy-right’ in association with a painting, however, was atypical.

Painting as Intellectual Property in Eighteenth-Century London: Art Theory and its Intersection with Artistic and Trade Practices

Through exhibitions, artist-dealer contracts, and in their relationships with patrons, leading British painters asserted an entitlement to oversee the afterlife of their compositions in print, in spite of the lack of statutory law on painting in England. Such a claim was not only based on art theory, which defended the intellectual nature of the painter’s art. It also depended on the British print trade’s capacity to produce fine reproductive prints that painters would accept as proper expression of their creations. By and large, British printmakers reached this degree of excellence in the second half of the eighteenth century, as result of John Boydell’s patronage and business practice in the London print trade.

John Boydell, an engraver by training, would become one of the leading figures of the British art world by the end of the eighteenth century. He not only worked as a publisher and print seller, but also promoted contemporary British painting in various ways. As a publisher, he commissioned, exhibited, and published paintings by living artists. He donated works of art to public institutions, developed a large network of patrons within elite circles, and published several aristocratic collections in print. He also held several public offices, which he used to promote contemporary painting commissions, and fund public building renovations with ambitious painting programs.22

Following a regular apprenticeship in engraving, Boydell started as an engraver and print seller in the late 1740s London. In 1751, he purchased a membership in the Stationer’s Company and moved to large quarters on the West corner of Queen Street and Cheapside. There, he opened a full-scale shop and decided to distinguish himself from his peers by almost exclusively focusing on selling fine reproductive prints. These high-end commodities had to be imported from France. According to later recollections, the hard cash Boydell had to pay for the prints — no print publisher on the other side of the Channel at that time would accept British prints in exchange — led him to invest in the most promising young English engravers to raise the quality of British reproductive art. He considerably increased premiums paid to engravers — paying amounts for a single plate that had never before been seen in England — to secure the best artists’ work for his projects, and to encourage engravers to dedicate their time to the adaptation of celebrated paintings into print.23 This successful strategy set new standards both in the print trade and the art world at the same time. Boydell was soon able to offer quality engravings on par with foreign imports, which put him in a position to contract with major painters and engravers for the reproduction of famous works by contemporary artists such as Benjamin West (for instance, The Death of General Wolfe — see Figure 5). In time, these engravings found a market both in England and on the European continent.24 More importantly, the growing role of reproductive engravings in contemporary British culture — a role that Boydell strategically brought about and emphasized in high-profile publications, exhibitions, and public works — converged with influential art theory to clear a path for British painters’ demand for authorial control in reproduction.

The concept of painting as a liberal art certainly was critical to the emergence of artists’ claims of authorship in the eighteenth century.25 However, it is in the relationship drawn between a painting and its publication in print that the seeds of an abstract notion of intellectual property in a painting were sowed. Several authors, in particular Charles Alphonse du Fresnoy (De Arte Grafica, translated into English by John Dryden in 1695), Roger de Piles, and Jonathan Richardson were responsible for popularizing the liberal-art status of painting in the British Empire.26 Their influence expressed itself in the language of the 1735 petition that called for new copyright legislation protecting images. The pamphlet called attention to the ‘genius’ of the artist and complained about the difficulty of exerting one’s ‘invention’ in the conditions of artistic creation created by the print trade: ‘seeing how vain it is to attempt any thing [sic] New and Improving, […] [the artist] bids farewel [sic] to Accuracy, Expression, Invention, and every thing [sic] that sets one Artist above another, and for bare Subsistence enters himself into the Lists of Drudgery under these Monopolies [of the printsellers].’27

Invention and genius are typical critical terms associated with the language of the liberal arts. They were also keywords used in the teachings of the Royal Academy (RA) founded in 1768. Its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, was an admirer of Richardson’s work, and one of the major proponents of the concept of painting as a liberal art, alongside that of the artist as intellectual genius. Richardson argued that painting’s ‘business [was] above all to communicate ideas’. Bainbrigg Buckeridge, another influential author who translated Roger de Piles in 1706 and whose writings were published in several editions through 1754, re-introduced Horace’s ut pictura poesis to argue for the superior mental qualities of the art:

Painting is sister to Poetry, the muse’s darling; and though the latter is more talkative, and consequently more able to push her fortune; yet Painting, by the language of the eyes and the beauty of a more sensible imitation of nature, makes as strong an impression on the soul, and deserves, as well as poetry, immortal honours.28

Reynolds expressed his belief in the intellectual nature of artistic creation in the academy’s curriculum and in his Discourses, which formulated what became the dominant theory of art in England: ‘This is the ambition I could wish to excite in your minds,’ Reynolds instructed his students, ‘and the object I have had in my view, throughout this discourse, is that one great idea which gives to painting its true dignity, that entitles it to the name of a Liberal Art, and ranks it as a sister of poetry’.29 If painting was a liberal art, it meant that the artist’s genius was the true source of a higher realm of artistic creation:

Neatness and high finishing: a light, bold pencil; gay and vivid colours, warm and sombrous; force and tenderness; all these are […] beauties of an inferior kind, even when so employed; they are the mechanical parts of painting, and require no more genius or capacity, than is necessary to, and frequently seen in ordinary workmen.30

The greater priority given to artists’ genius had profound implications for their status as intellectual authors: genius was not nurtured in a workshop; rather than a learned skill, it was a fundamentally innate and abstract quality, and one specific to individuals. Consequently, as Richardson explained, it would not reveal itself in the material handling of the paint, but would be detected in one particular quality: the artist’s capacity for invention.

Giving priority to intangible elements at the expense of material ones, the theory of painting as a liberal art contributed to the detachment of the artist’s authorship from the material utterance of the painted work. As will be discussed below, the same writers who advocated for the liberal-art status of painting also encouraged connoisseurs and amateurs of the visual arts to find and contemplate similar abstract features both in the art of painting and in that of engraving. Instead of considering the work of the engraver in its own terms, viewers were to revel in the way prints conveyed the painter’s genius and invention. Art theory thus contributed to the mental transfer of the painter’s authorship from the painted surface onto the reproductive print. Such notions found a direct translation into the language of the 1735 Copyright Act, which not only offered protection to visual works produced by artists who made their own compositions — what we today consider ‘original prints’ — but also offered copyright protection to ‘every person who […] from his own works and invention, shall cause to be designed and engraved, etched, or worked in Mezzotinto or Chiaro Oscuro, any historical or other print or prints’.31 In other words, the 1735 act, although primarily designed to protect the work of artists like William Hogarth, also opened the door for painters to claim proprietorship on their own painted compositions.32 There is enough evidence in the archive to show that at least some painters did just that.33 But it was only in the second half of the eighteenth century that reproductive prints — that is, prints after another work of art (usually a drawing or a painting) — became a dominant force in the British print trade.34 This turn of events, largely due to John Boydell’s strategic business decisions and his patronage of contemporary British painters, had an impact on legislation: it drove the expansion of copyright protection to reproductive prints specifically — including prints after old masters, and those made outside of Britain — and opened that protection to publishers as well as artists.35 Additionally, it affected the way British painters were able to claim intellectual ownership over their paintings, and the privileges that such claims conferred on them: a right to authorize an engraving (or not), irrespective of whether the original painting had been sold and left the painter’s studio.

Because of Boydell’s intervention in the reproductive print trade — and the financial success of his enterprise — the leading engravers working after 1750 turned their attention to the adaptation of existing compositions, often paintings, by old masters and living artists, rather than creating their own compositions. Reproductive prints had a long tradition in the history of art since the Renaissance: they had played a critical role in the circulation of artistic designs beyond painters, sculptors, and engravers’ restricted circles of patronage.36 Intaglio engravings, or engravings on metal, had come to be considered the highest form in which a painting could be reproduced. As a result, the preeminent engravers’ task was the reproduction of an artist’s design on the copper plate.37 At the same time, the quality of an engraving was measured in terms of the competence and creativity of the engraver’s imitation: ‘Engraving, which only imitates Nature, must follow her in every way’, explained Abraham Bosse, in what was the most influential treatise in Europe until the end of the eighteenth century.38 In other words, the critical vocabulary and intellectual framework through which engravings were evaluated did not fundamentally differ from those of the other visual arts (painting and sculpture) which it reproduced and conveyed in a new medium. In England, however, as the print trade turned to the adaptation of old masters and contemporary paintings into prints, the fame of engravers increasingly rested on the status of the living painters whose work they successfully adapted to the copper plate. As commissions to represent contemporary paintings in print became publicized through large single picture exhibitions in London, the significance of the collaboration between painter and engraver took on an increased importance.

The success of the alliance between painter and engraver was evaluated by comparison with a powerful antecedent in the Renaissance: the relationship between Raphael and his contemporary, the printmaker Marcantonio Raimondi. Although ‘Marc Antonio’s engravings come far short of what Raphael himself did,’ admitted Richardson, ‘all others that have made prints after Raphael come vastly short of him, because he [Marcantonio] has better imitated what is most excellent in that beloved, wonderful man [Raphael] than any other has done.’39 The market and aesthetic values of a print depended on the close relationship between painter, engraver, and draftsman involved in its production. Archival evidence, in particular contracts between artists and publishers, support the view that Boydell’s publications of paintings by the most important contemporary artists were highly collaborative enterprises, through which the painter not only gained financial return but also fully partnered in the project.40

Gilbert Stuart’s early career was profoundly affected by such artistic partnerships (which included the print publisher as well). His portrait of the engraver William Woollett (see Figure 2) belonged to a large commission of portraits of living artists by Boydell who intended to use them as promotional material. Woollett was an early collaborator of Boydell’s, and one of the most sought-after engravers in London. His plate after Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe (1776) had become the most celebrated engraving of the time.

Fig. 5 William Woollett after Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe (1776), engraving, 1966.0260 A, B, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Museum purchase, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Photo funded by NEA.

Stuart called attention to the significance of the collaborative partnership between painter and printmaker in his portrait of Woollett: the picture shows the engraver working on his plate directly with West’s painting in the background to emphasize the intimate relationship between the painter’s work and the engraver — even though Woollett more likely worked from a drawing after the painting as was customary practice (an intermediary drawing would not only bring the composition to the size of the plate but would also adapt it to a grayscale).

Boydell’s public exhibitions of Stuart’s portraits also highlighted the close relationship between painter and graphic interpreters. He displayed John Singleton Copley’s Death of Major Peirson topped with Stuart’s portrait of Copley, the painter, at the center, flanked by those of James Heath (the engraver), and Joshua Boydell (the draftsman who made an intermediary drawing after the painting). The exhibit served to promote both Copley and the engraving — subscription papers were available at the gallery. It not only attested to the collaborative nature of the work that presided over the creation of the engraving, but also implied the painter’s endorsement of the printed image. Highlighting the alliance between the genius of the painter and the talent of its interpreters, Boydell’s public displays of paintings like Copley’s Death of Major Peirson anticipated the reference status of the engraving, similar to what Marcantonio’s engravings were to Raphael’s paintings. This was of critical importance since, as Richardson declared, it was not the painting but the graphic work that would ultimately convey the painter’s ‘last, […] utmost thoughts on [a] subject, whatever it be’.41 Richardson and other theoreticians of art created habits of viewing and appreciating an engraving that was tied to the way the graphic image conveyed the work of the painter-author of the composition. In other words, art theory converged with Boydell and artists’ partnerships in publishing and exhibition to facilitate the painters’ insistence that they should control when, how, and by whom their work of art would be adapted into print. Benjamin West collaborated with Boydell and with engravers William Woollett and John Hall for the publication of several of his history paintings in print, including The Death of General Wolfe, and Penn’s Treaty with the Indians.42 John Singleton Copley painted some of his greatest historical paintings for publication. Although he remarked later that ‘the difficulties of a Painter began when his picture was finished, if an engraving from it should be his object’, the artist was deeply invested in the appearance of his paintings in print, and in their quality.43 The catalogue of the Sotheby’s Copley print sale, held five years after the painter’s death in 1815, listed a large number of copper plates after his own works. The quality of a print after a painting was so important to Copley that he was ready to go to court to defend the need for the highest quality in a reproductive engraving. Dissatisfied with the plate after his Death of Earl Chatham, the painter refused to pay the engraver’s premium. The disagreement between the two artists led to a famous court case that opposed Copley to his engraver Jean Marie Delattre in 1801.44 In other words, art theory converged with Boydell’s trade practices and with painters and engravers’ partnerships to facilitate the painters’ aspirations to control when, how, and by whom their work of art would be adapted into print.

At the same time, artistic and trade practices expressed something more than what Ronan Deazley has called a painter’s ‘engraving rights.’45 They showed that a painter was the author of an intellectual work, manifest both in the painting and in the print. Boydell’s exhibition and publication practices promised subscribers an image that not only communicated the painter’s approved authorial presence in the engraving, but also prepared the viewer to experience artistic authorship in the most abstract terms. As Richardson explained, the painter’s creation could only be conveyed through the work’s most intellectual elements: ‘invention, composition, manner of designing, grace and greatness’.46 The physical ink marks transferred from the copper plate to paper during the printing process were of secondary importance. They attested to another artist’s hand, an interpreter whose talent lay in an ability to accurately translate another creator’s thoughts in the visual language of lines and dots of printed ink on paper.47

When subscribers received their engraving or when spectators looked at the engraving through a shop window, what they saw was not the engraver’s talent, but the painter’s genius. Benjamin West recalled an anecdote from a conversation with the naval hero Horatio Nelson that stresses the importance of this point: ‘I never pass a print-shop with your “Death of Wolfe” in the window’, West reported Nelson saying, ‘without being stopped by it’. Nelson’s (and West’s) use of the possessive adjective for The Death of General Wolfe clearly identifies the painter as the intellectual author (and would-be legitimate proprietor) of the engraved image.48

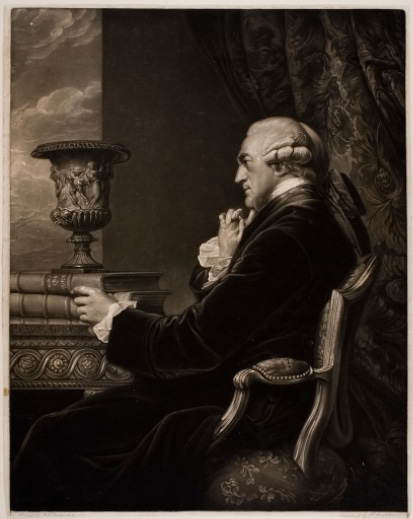

The cultural predominance of the artist-author that this conversation articulates had extensive applications — especially in the relationships between artists and their patrons. While British painters learned to rely on their relationship with publishers, as well as the 1735 and 1766 statutes to exert some control over the afterlife of their painting in print, the absence of legislation on paintings themselves presented potential difficulty when they left the studio before plans for engravings had been made.49 A dispute that arose between Copley and the owners of one of his portraits, however, sheds light on the extensive power that art theory and trade practices had come to exert over British art patronage at the turn of the nineteenth century. The quarrel never became public. It arose after the death of Anglo-Irish nobleman William Ponsonby, 2nd Earl of Bessborough.

Fig. 6 Robert Dunkarton, after John Singleton Copley, Portrait of William Ponsonby, Earl of Bessborough (1794), mezzotint, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Transfer from Harvard University, Gift of Gardiner Greene. © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

His heirs desired to pay tribute to Ponsonby’s lifelong devotion to art patronage by commissioning a print after a portrait of the earl, painted by Copley in 1790. The deceased’s family and friends contacted the best art publisher of the time, John Boydell, to contract for the publication of the mezzotint. The arrangement was to use Admiral Caldwell’s copy of Copley’s portrait and have it adapted into print by one of Boydell’s engravers. Possibly hearing of the project from Boydell himself, Copley wrote to Caldwell to stop what he felt was an unauthorized reproduction of his work, expressing outrage at the owner’s lack of awareness of customary practices: ‘It is extremely uncommon for an engraving to be made from a picture without first consulting with the Artist who has painted it’.50 Copley continued, ‘I did not make any express agreement to secure myself from that inconvenience because I did not suppose it necessary. […] I certainly however expected that both the Copy which I painted for Lord Clanbrassel and that which I painted for Admiral Caldwell would be considered as delivered from my possession with the implied condition of their not being published.’51

Copley, as we know, was deeply preoccupied with the publication of his paintings, whether portraits or grand manner historical works; according to the same letter, he had already contracted Robert Dunkarton for the work. As Copley’s phrasing indicates, his expectations did not rely on legal texts but rather on usage and conventions. The painter would likely not have had any recourse in the law. Yet, in spite of Caldwell’s indignant response, the painter’s point of view prevailed, thanks at least in part to the printseller’s intervention. Boydell recommended that Caldwell and the family’s publication project be abandoned, and Copley published a mezzotint of his portrait, made after the copy Copley had painted for the Earl of Clanbrassel. As with several other of his paintings, Copley was the owner of the copyright for the print, Portrait of William Ponsonby, Earl of Bessborough (see Figure 6).52

Building on the critical art theory that defined painting as a liberal art, and that envisioned engraving’s primary purpose in its ability to convey a painter’s invention, artistic and publishing practices in eighteenth-century London created a climate in which the predominant relationship that defined the art of engraving was its ability to communicate the essence of an original work of art. Critical discourse and visual experiences of paintings and reproductive engravings redirected viewers’ attention away from the contemplation of the object itself to consider the artist’s power of invention independent of the medium in which it was expressed. Painters and beholders learned to privilege an intellectual response to a picture and the evocative power of formal elements, including composition and harmony of line and forms. Artists worked with an eye to the appearance of their paintings in print to ensure their posterity. It was not only critical that a painting be published in engraved form: it was equally important that the painter vetted the engraver commissioned for the job, since painters and beholders were expected to see the painter’s extended authorship in the print. In addition to the dominant theory of art and many an artist’s experience studying the old masters in print — the most common vehicle that ultimately conveyed their invention in visual form — trade practices and the copyright statute of 1766, all reinforced the painter’s authorial presence in reproductive engravings. Many painters thus claimed it in the reproduction. Intellectual ownership of one’s painting in the form of an engraving entitled painters to assert a right to limit copying, and the right to authorize a painting’s publication as an engraving. In the expanding art world and reproductive print trade of eighteenth-century England, British painters found fertile ground for claims of intellectual ownership over their compositions, and of the right to oversee the conditions of their publication — all elements that Gilbert Stuart would later claim for himself in the less- favorable environment of the new American Republic.

Stuart and the Visual Economy of the Young Republic

The relationship between a painting and its reproduction in an intaglio print, and the painter’s customary power to authorize a reproduction, was thus fundamental to the artistic culture in which Gilbert Stuart became an artist. When Stuart demanded that William Bingham not cede his publication right together with the portrait of Washington commissioned for the Marquis of Lansdowne, he was following the established practices that Copley described in his letter to the 2nd Earl of Bessborough’s friend. The artist’s request to his patron was therefore far from extraordinary. What was new in the case of Stuart was that he expressed his claim in property and copyright terms. He was not, moreover, the only one to do so.

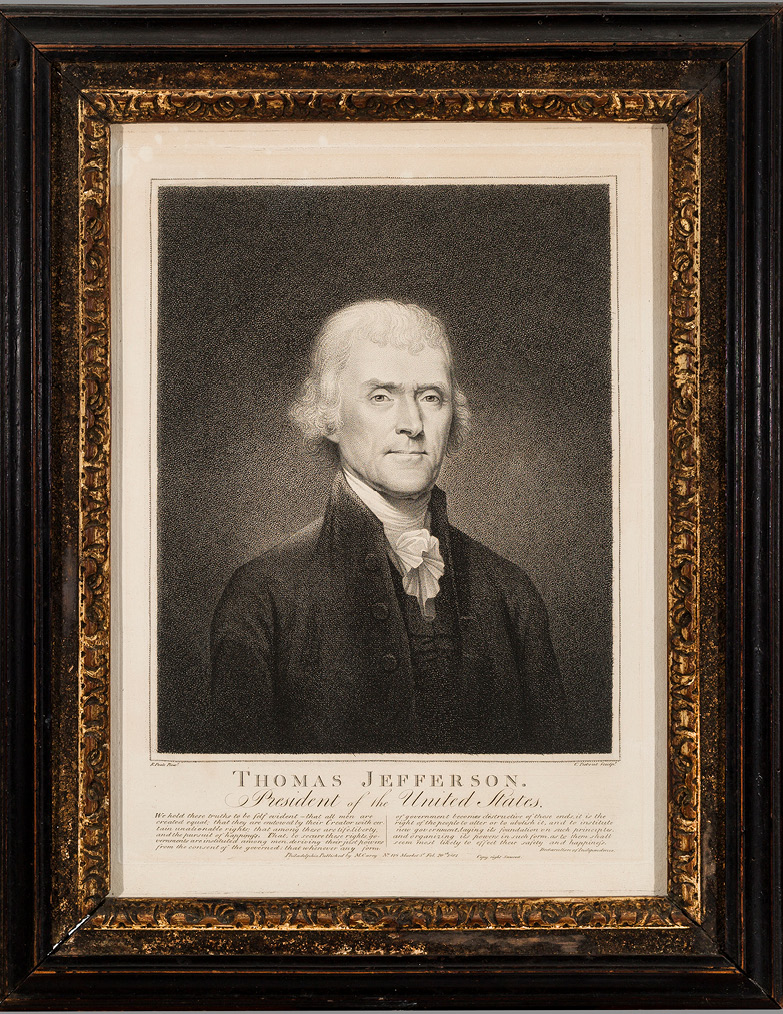

Fig. 7 Cornelius Tiebout after Rembrandt Peale, Portrait of Thomas Jefferson (1800), stipple engraving, 1963.0060, Winterthur Museum Garden & Library, Museum purchase, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Photo funded by NEA.

In 1800, Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860), the son of Charles Willson Peale and a young, ambitious artist who twenty years later would petition Congress for statutory protection of paintings, monetized the copying of his portrait of Thomas Jefferson as a right to its publication. Although he could not claim prices as high as Stuart for portraying his sitters, he followed similar practices. When Thomas Jefferson rose to the presidency in 1800, Rembrandt Peale collaborated with the enterprising Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey to create the best printed image of the president elect (see Figure 7).53 Working in concert with the painter on this enterprise, Carey bought from the artist the right to publish the painted portrait of Jefferson as a print for $50. Following in Boydell’s steps, the publisher also paid a premium of $150 to the best available Philadelphia engraver, Cornelius Tiebout, to engrave the plate.54 The sum Peale received for letting Tiebout draw a copy of his work for the engraving was significantly higher than what Peale asked for an ordinary copy he would paint himself ($30). This indicates that the money received from Carey was a payment for the right to copy and publish the original work of art in printed form, in addition to the repeated composition.55 Carey made this explicit when marketing the print: in order to attract attention to the forthcoming plate, he circulated a limited number of unfinished proofs of Tiebout’s engraving, together with subscription papers. Carey inscribed the plate with the mention ‘Copy Right Secured’ in the lower right margin, and gave strict instructions to his agents to not let anyone borrow the print so as to prevent any unauthorized copying.56 At that time, there was no legislation on copyright for images in the United States. Peale and Carey not only followed what they considered proper trade practices — the purchase of the artist’s authorization to copy before publishing. Carey also claimed a monopoly on Peale’s depiction of Jefferson, a privilege that he did not legally control in the unregulated context of the early Republic. The risk of piracy was not negligible, making it necessary for the publisher to spell out a claim which asserted an exclusive right in the publication of Peale’s image of the newly elected president. This also revealed what the artists and publishers regarded to be the conceptual essence of the long-established trade and artistic practices that had developed in England over the past fifty years.57 A painter’s authorization to have his work copied had monetary value. For Stuart, Peale and Carey, this was a copyright in the painter’s image.

Gilbert Stuart, Rembrandt Peale, and Mathew Carey were not only trying to set public standards and rules for the trade in the highly competitive and unregulated engraving market in the United States in the first decade of the nineteenth century.58 They also claimed ownership of an intangible property rooted in a painting, and one not circumscribed by the materials used, nor by the physical traces of an artist’s work on its surface. This property was originally tied to the painter’s publication of the work in print. At the same time, Stuart’s difficulty with Captain Sword makes clear that — in the eye of the artist at least — it applied to any medium, whether they mechanically reproduced an image or not.

Examined in both its local American and its transatlantic contexts, Stuart’s bill against Captain Sword indicates that the portraitist fully discerned the conceptual implications of the artistic theory and trade practices that had nurtured his career in London. In the United States, Stuart had to assert what they meant, owing to the absence of well-established rules of trade, art institutions, and the uncertain legal framework that might otherwise defend them in America. For his litigation against Sword, Stuart received legal advice from well-established members of the Philadelphia Bar, who were all among his patrons. Alexander James Dallas (1759–1817), whose portrait Stuart painted in 1800, was the United States Attorney for the District of Pennsylvania where Gilbert Stuart filed his bill. William Lewis (1751–1819), whose portrait by Stuart is known through John Neagle’s copy, was a Quaker, and a lawyer involved in the drafting of the act for the gradual abolition of slavery that passed in Pennsylvania in 1780. William Tilghman (1756–1827) was a lawyer and plantation owner from Maryland, who had moved to Philadelphia in 1793, and briefly served as a federal judge of the US Circuit Court in 1801. Last but not least, William Rawle (1759–1836), also a Quaker and another of Stuart’s patrons, was a lawyer involved in numerous learned societies and cultural circles. He would contribute to the foundation of the Pennsylvania Academy for the Fine Arts in 1805. Dallas, Lewis, Rawle, and Tilghman were all known for their sympathy for the rights of British citizens. They commissioned and purchased works of art from Stuart. At least one of them, William Rawle, had more than a casual interest in the role of the visual arts in the United States.

In light of the scant archival record, it is unclear under what terms Stuart won his case at court. Nothing in his bill indicates that his lawyers or the presiding judge recognized the legal weight of an artist’s claim of intellectual property over a painting in the context of US-American law. Dallas, Lewis, Rawle, and Tilghman more likely saw possibilities in the breach of contract between Stuart and Sword. The remedies Stuart asked for do not, however, shed much light on this question. The bill Stuart presented to the court expressed a concern that his claim would not find sufficient remedies at common law: ‘Your orator hath no plain, adequate, and complete relief in the premises at Common Law’. Common law remedies gave the complainant the possibility to recover costs equivalent to damages that could be proven — there are no records of how many of the portrait Sword did sell — but they did not permit the confiscation of fraudulent copies. By the time Sword landed in Philadelphia with the copies of the Athenaeum type, we know that Stuart had secured about forty commissions for Washington’s portraits. The painter was therefore stretching the well-established practice of repeating one’s work of art for several patrons further than anyone has done before him. Scholars have estimated the total output of Stuart’s Washington portraits slightly above one hundred, a quantity exactly corresponding to the number of Sword’s Chinese copies. Over the course of just a few months, Sword was throwing on the market an equivalent of the painter’s life work. The sheer quantity of paintings imported by Sword was a major threat to the artist’s livelihood, and their forfeiture was clearly the painter’s goal. Stuart therefore requested remedies that the court of Chancery in England could issue — an injunction ordering the delivery and destruction of the fraudulent goods. Stuart’s case was solved in favor of the painter, showing that the court likely accepted the validity of the painting’s contractual sale, together with its limitations on copying.

The case of Stuart v. Sword, together with Stuart’s public campaign against James Heath’s unauthorized engraving and Rembrandt Peale’s contract with Mathew Carey for the reproduction of his portrait of Jefferson, shows the importance that artists and publishers gave to an abstract concept of artistic property as well as proper trade practices — practices clearly inherited from British antecedents, but that had also not been broadly accepted in the US-American context. Chinese reverse painting on glass, the medium of Sword’s unauthorized copies of Stuart’s Washington portrait, was not a new type of artwork in the early 1800s Philadelphia. Such paintings — often copies after printed images — had been circulating in Europe and America since the seventeenth century. Nevertheless, the industrial scale of Captain Sword’s order of one hundred copies — which likened the final product to luxurious but utilitarian objects like Chinese export porcelain plates — combined with its unique life-size format, made the reverse paintings after Stuart’s Athenaeum portrait an utterly new kind of object on the American market. Captain Sword’s portraits of Washington, ‘made in China’ and offered for sale in Philadelphia, were also a direct consequence of the expanded trade routes open to US-American shipping after the country’s independence. These exotic objects did not bring an entirely new set of questions to the fore; the right that a painter had to restrict copying of a painting after a painting’s sale had its roots in the London art world and could obviously be enforced under certain conditions. However, the new medium in which the copies were executed brought a new and broader set of answers to these questions.

Unlike Heath’s engravings, the paintings on glass could not be considered a publication of the original work. Just like Carey’s purchase of a right to publish Rembrandt Peale’s portrait of Thomas Jefferson, Stuart’s approach to stop the sale of about one hundred unauthorized copies of a likeness of Washington, and his press campaign addressing the unauthorized publication of his Lansdowne portrait demonstrate that artists and publishers shared in the opinion that the creator of a work of art had the right to control copying of his original work. They believed that this right should be respected no matter the medium in which a work of art might be reproduced: whether a painted full-size copy made on another continent, or an engraving commissioned in London by the new owner of the work. As Sword and Bingham’s undertakings show, not all collectors or purchasers of art agreed with this opinion. Equally important, Stuart’s legal and public attempts to control the reproduction of his portraits after sale also reveals the difficulty that artists, print sellers and publishers faced in exerting their prerogative in a new nation, trading far and wide without long-established public advocates or art institutions like the Royal Academy. American independence had opened new channels of direct trade with Asia, and this new pattern of trade had suggested to Captain Sword untried avenues of profit through the multiplication of a portrait of George Washington in a luxurious, exotic format. This represented both a high point in the demand for images of the country’s founding father — Washington had died less than two years earlier — and a time of uncertainty with regards to how Congress intended to provide legislation that would protect American artists and their creations.

Stuart, Carey, and Peale’s practices expanded on what Ronan Deazley has called a painter’s ‘engraving rights’, expressed through art publishers’ contracts with painters like Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley.59 Stuart’s advertisement against the Heath’s unauthorized British engraving, Carey’s requested inscription below Tiebout’s proof engraving, and the Stuart v. Sword litigation demonstrate that American artists and publishers did not defend an ‘engraving right’ per se, but a broader intangible ownership in a work of art, which meant a right in controlling copying and publication in all media available, prior to and following the sale of the artwork, within and outside the boundaries of the nation state. In the unregulated marketplace of the young American Republic, Stuart, Peale, and Carey claimed that this was properly a ‘copy-right’ and one that was directly connected to the original work, not just a printed image. This broad claim of authority over copying — in contracts, in the press, and in Stuart v. Sword — was founded on the dematerialization of the painter’s authorship over the image, which had been advanced in theoretical discourses on art, and in the relationships between intaglio engravings and paintings: ones that took pride of place decades earlier in exhibitions and high-profile commissions in Britain. Separate from the ownership of the material work, this intellectual property, the creative genius’s expression in the painting or in the print, could not be transferred without either a purchase from the painter, or at the very least an official endorsement.

Ultimately, however, the intangible nature of the work of art would not entirely hold in the US-American legal context. One could not simply discard the material and visual dimensions of a picture. This issue became the center of a court case in 1821: Binns v. Woodruff, which concluded that the artistic property in a picture was both intangible and material.60 John Binns, an Irish-born Philadelphia publisher, had commissioned several artists to draw and engrave the elements of a composition that presented a copy of the Declaration of Independence with facsimiles-signatures framed into an oval made of decorative medallions representing the arms of the thirteen States of the United States, and the portraits of three founding fathers: John Hancock, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson, capped by the great seal of the United States. He had deposited an incomplete state of the print for copyright in November of 1818, accompanied by a prospectus. In February 1819, a similar design was engraved by William Woodruff, and Binns sued for infringement on his copyright.61 Binns lost his case at court on the account that he had not drawn the design himself, but only given verbal directions to others; in the end, five artists (Bridport, Valance, Bird, Murray, and Sully) had given the printed image its composition and visual form, not Binns himself. Although the engraving act of 1802 followed the British Engraving act relatively closely, as Robert Brauneis has shown, the language of the American law limited those who could claim copyright protection: the proprietor of an image could be either ‘every person […] who shall invent and design, engrave, etch, or work’, or everyone who ‘from his own works and inventions, shall cause to be designed and engraved, etched or worked, any historical or other print or prints’.62 The language of the law indicated the importance of being either the maker or the inventor of a picture in order to claim copyright protection. However, Judge Bushrod Washington interpreted the statute further, explaining that the language of the law indicated without doubt that the person ‘intended and described as the proprietor of a copyright’ must either be the engraver of the print (‘in other words, the entire work, or subject of the copyright is executed by the same person’) or the author of the original design in another medium: ‘the invention is designed or embodied by the person in whom the right is vested, and the form and completion of the work are executed by another’.63 The court was clear that the commissioner of a painting could not claim the copyright for a picture since he had not given it visible form on a material support. Calling on the British antecedent of Blackwell v. Harper, Judge Washington remarked that the plaintiff ‘not only conceived the idea of making a representation of the medicinal plants, but she also engraved them herself, and the combination of the two afforded the evidence of genius and art which the law intended to encourage’.64 In the absence of a contract of sale of the image’s copyright, the commissioner of the print could not claim property in the print. The use of the terms ‘genius’ and ‘art’ in Judge Washington’s decision are direct references to a combination of intellectual labor and technical knowledge. Intellectual property in the visual arts was not considered entirely immaterial. Conceiving the idea of a design was no ground for copyright unless one transformed this idea into a visible design. A picture could not entirely be separated from its material form.

Eighteenth-century artistic practices and art theory built the foundation for a broad concept of intellectual property in painting, and its expression in early American trade practices. In spite of the lack of legislation on painting in the United States at that time, the notion that an intangible property in a painting existed outside of statutory law did find traction in the cultural landscape of early nineteenth-century Philadelphia. Even though Stuart v. Sword was not reported in the legal literature at the time, there is little doubt that the conception of painting as intellectual property that painters and publishers like Stuart and Carey envisioned had a profound impact on the next generation of artists to which Rembrandt Peale belonged. Stuart never returned to Britain, but in the United States, he became a founding figure for young painters who sought him out for advice and instruction. One of them, John Neagle, who would become a director of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, recalled discussing these events with the master. Neagle later reported to William Dunlap the Philadelphia merchant’s inappropriate conduct vis-à-vis Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait, and how Stuart had been deprived of his property in the painting. Dunlap made it an important story in his chapter on Stuart in his 1834 History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States. In 1848, at a time when there was still no legislation on the copyright of paintings, William Sidney Mount, the celebrated genre painter, privately commented on being compensated for the copyright of The Power of Music when the newly established French art dealer and publisher Goupil & Co. contracted him for the painting’s publication.

The notion of artistic property in a painting did not find expression in the 1802 statute, which limited copyright protection to printed images. However, Stuart’s disputes over his portraits of Washington also anticipated key questions that would be debated in England in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, namely whether one could hold an intellectual property right for an unpublished painting, and if so, under what condition(s) that property might be secured, forfeited, or transferred together with the material work.65 In the United States, while the 1802 act restrained protection to printed images, the text still offered protection to the author or ‘inventor’ of a picture, even if she/he did not actually work on the print itself. American jurisprudence reinforced this view with Binns v. Woodruff: painters who necessarily produced material works expressing their intellectual inventions could become proprietors of their own pictures. Expectedly, Stuart took advantage of the law and copyrighted (together with the engraver David Edwin) several of his pictures, including a portrait of Thomas M’Kean, governor of Pennsylvania, and a portrait of Washington in 1803. Stuart’s copyright deposits also represent the first scant archival evidence of a painter’s interest in using the legal system to protect an intellectual property originating in a painting in the United States. What is surprising, in fact, is how few well-known painters followed in Stuart’s steps. The importance of printed images in US-American visual culture only grew in the next decade, and some of the nation’s most innovative artists, such as the recent German immigrant John Lewis Krimmel, Thomas Sully, and Asher B. Durand, cultivated close relationships with the publishing industry, not only using reproductive prints as sources for inspiration but also entering into collaborations with local printmakers, publishers, and magazine editors with whom they explored the possibilities offered by the expanding print culture of the Republic. More research on the early American publishing industry and its relationship with artists might yield further insight into the reasons why US-American painters (with the exception of Rembrandt Peale) did not pursue legal means of protecting what many privately considered a copyright in their paintings.66

Bibliography

8 Geo II, c. 13: An Act for the encouragement of the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints, by vesting the properties thereof in the inventors and engravers, during the time therein mentioned (1735) digitized in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by Lionel Bently & Martin Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org: http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_uk_1735.

7 Geo. III, c.38: An act to amend and render more effectual an act made in the eighth year of the reign of King George the Second, for encouragement of the arts of designing, engraving, and etching, historical and other prints; and for vesting in, and securing to, Jane Hogarth widow, the property in certain prints, 1766 — digitized in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org: http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_uk_1766.

Barratt, Carrie Rebora and Ellen G. Miles, eds., Gilbert Stuart (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004).

Bently, Lionel, ‘Art and the Making of Modern Copyright Law’, in Dear Images: Art, Copyright and Culture, ed. by Daniel McClean and Karsten Schubert (London and Manchester: Ridinghouse and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, 2002), pp. 330–351.

Bosse, Abraham, Traicté des Manières de Graver en Taille Douce sur l’Airin, Par le Moyen des Eaux Fortes, et des Vernix Durs & Mols (Paris: 1645).

Bracha, Oren, Owning Ideas. The Intellectual Origins of American Intellectual Property, 1790–1909 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016) https://doi.org/10.1017/9780511843235.

Brauneis, Robert, ‘Understanding Copyright’s First Encounter with the Fine Arts: A Look at the Legislative History of the Copyright Act of 1870’, Case Western Reserve Law Review, 71 (2020), 585-625.

Bruntjen, Sven H. A., John Boydell, 1719–1804: A Study of Art Patronage and Publishing (New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc., 1985).

Buckeridge, Bainbrigg, The art of painting, with the lives and characters of above 300 of the most eminent painters (London Printed for T. Payne, 1754).

Cao, Maggie, ‘Washington in China: A Media History of Reverse Painting on Glass’, Common-Place, 15:4 (Summer 2015)/Object Lessons, http://commonplace.online/article/washington-in-china-a-media-history-of-reverse-painting-on-glass/.

Carey Papers, Account Books, no. 5995, American Antiquarian Society.

Chadwick, D., E. P. Richardson, Claude Flory and Edward R. Black, eds., ‘“Notes and Documents,” Gilbert Stuart, D.’, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 14:1 (January 1970), 95–103.

Chan, Libby Lai-Pik and Nina Lai-Na Wan, eds., The Dragon and the Eagle: American Traders in China, A Century of Trade from 1784 to 1900, Hong Kong Maritime Museum (2018).

Clayton, Tim, The English Print (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

Copyright Records, Pennsylvania, Eastern Circuit Court, Library of Congress, microfilm reel 61, vol. 262, 1790–1804.

Cooper, Elena, Art and Modern Copyright. The Contested Image (Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316840993.

Crossman, Carl, The Decorative Arts of the China Trade (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1991).

Cunningham, Noble E., The Image of Thomas Jefferson in the Public Eye: Portraits for the People, 1800–1809 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1981).

Deazley, Ronan, ‘Commentary on the Models and Busts Act 1798’, in Primary Sources on Copyright, ed. by Bently and Kretschmer, http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord?id=commentary_uk_1798.

Drone, Eaton S., A Treatise on the Law of Property in Intellectual Productions in Great Britain and the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1879).

Du Fresnoy, Charles Alphonse, and John Dryden, trans., De arte graphica. The art of painting, by C. A. Du Fresnoy. With remarks. Translated into English, together with an original preface containing a parallel betwixt painting and poetry. By Mr. Dryden (London: W. Rogers, 1695).

Finnegan, Rachel, ‘“An Extreme Cunning Fellow”: Copley’s Memorial Engraving to the 2nd Earl of Bessborough’, Print Quarterly, 24:1 (March 2007), 3–11.

Faithorne, William, The Art of Graveing and Etching, wherein is expressed the true Way of Graveing in Copper; also the Manner of that famous Callot, and M. Bosse, in their several ways of Etching (London: A. Roper, 1702).

Gómez-Arostegui, Tomás, ‘Copyright at Common Law in 1774,’ Connecticut Law Review, 47:1 (2014), 1–57.

Griffiths, Anthony, ‘Two Contracts for British Prints’, Print Quarterly, 9:2 (June 1992), 184–187.

Landau, David and Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

MacMillan, Fiona, ‘Is copyright blind to the visual?’ Visual Communication, 7:1 (2008), 97–118 (pp. 97–98), https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357207084868.

Michel, Christian, ‘Les débats sur la notion de graveur/traducteur en France au XVIIIème siècle,’ in Marie-Félicie Perez-Pivot and François Fossier eds., Delineavit et Sculpsit: dix-neuf contributions sur les rapports dessin-gravure du XVIe au XXe siècle (Lyon: Presses Universitaires de Lyon, 2003).

Neff, Emily Ballew, and Kaylin H. Weber eds., American Adversaries: West and Copley and a Transatlantic World (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2013).

Park, Lawrence, Gilbert Stuart: An Illustrated Descriptive List of His Works Compiled by Lawrence Park (New York: William Edwin Rudge, 1926).

Oberg, Barbara B. ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 33, 17 February-30 April 1801 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006).

Pon, Lisa, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Renaissance Italian Print (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

Prown, Jules D., John Singleton Copley, vol. 2: Copley in England (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1966).

Rather, Susan, The American School (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

——, ‘Benjamin West’s Professional Endgame and the Historical Conundrum of William Williams’, William and Mary Quarterly, 59:4 (Oct. 2002), 821–864, https://doi.org/10.2307/3491572.

Reynolds, Sir Joshua, Seven Discourses on Art (New York: Cassell and Company, 1901), transcribed and open access on Gutenberg.org: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2176/2176-h/2176-h.htm.

Richards, Rhys, ‘United States Trade with China, 1784–1814’, The American Neptune, 54: Special Supplement (1994).

Richardson, Jonathan, The works of Mr. Jonathan Richardson … all corrected and prepared for the press by his son Mr. J. Richardson (London: Printed for T. Davis, in Russel-Street, 1773).

Roncerel, Michel, ‘Traités de gravure,’ Nouvelles de l’estampe, no. 194 (May-June 2004): 19–27.

Rose, Mark, ‘Technology and Copyright in 1735: The Engraver’s Act,’ The Information Society, 21:1 (2005), 63–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/0197224059 0895928.

Scott, Katie, Becoming Property: Art, Theory and Law in Early Modern France (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018).

Stuart v. Swords [sic] Bill, filed 14, May 1802. Records of the District Court of the United States for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (National Archives and Records Administration, RG21.40.2 (1790–1804).

The Case of Designers, Engravers, Etchers, &c., London (1735), digitized in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org: http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_uk_1735a.

US Congress, An Act supplementary to an act, intituled ‘An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned’ and extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints (1802), digitized in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org: http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_us_1802.

Watelet, Claude-Henri. ‘Print (engraving)’, in The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project (Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2018), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0003.391. Originally published as ‘Estampe (Gravure),’ Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 5: 999–1000 (Paris, 1755).

Zorach, Rebecca, and Elizabeth Rodini, eds., Paper Museums: The Reproductive Print in Europe, 1500–1800 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

1 Eaton S. Drone, A Treatise on the Law of Property in Intellectual Productions in Great Britain and the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1879), p. v. Research for this chapter was supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities Post-doctoral Fellowship at the Library Company of Philadelphia. The author would like to thank Georgia Barnhill, Oren Bracha, Robert Brauneis, Elena Cooper, Jim Green, Peter Jaszi, Will Slauter, and Simon Stern for their comments. I am also grateful to the late Linda Eaton for her support to this project.

2 Ibid., p. 4.

3 Lionel Bently, ‘Art and the Making of Modern Copyright Law’, in Dear Images: Art, Copyright and Culture, ed. by Daniel McClean and Karsten Schubert (London and Manchester: Ridinghouse and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, 2002), pp. 331–351 (pp. 332–334); Fiona MacMillan, ‘Is Copyright Blind to the Visual?’ in Visual Communication, 7 (2008), 97–118 (pp. 97–98); Oren Bracha, Owning Ideas: The Intellectual Origins of American Intellectual Property, 1790–1909 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 376; Elena Cooper, Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 15–16. Drone’s treatise is discussed further in Bracha’s contribution to this volume, in relation to broader transformations affecting US-American literature and visual culture in the late-nineteenth century.

4 For an extensive discussion of the significance of this metaphor in Ancien Régime France, see Katie Scott, Becoming Property: Art, Theory and Law in Early Modern France (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018), pp. 37–90.

5 Susan Rather, The American School (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

6 For more on the legislative history of the 1870 Act, which extended copyright to drawings, paintings and sculpture, see Robert Brauneis, ‘Understanding Copyright’s First Encounter with the Fine Arts: A Look at the Legislative History of the Copyright Act of 1870’, Case Western Reserve Law Review, 71 (2020), 585-625. In the United States, the first case that debated the affinity between the written word and the visual language of painting in legal terms took place two years later: Parton v. Prang (1872).

7 In February of 1802, the Carlisle Gazette (PA) reported that George Helmbold Jr., a Philadelphia printer, publisher and print seller, presented a memorial asking for the extension of copyright protection to several types of images, including paintings. In contrast, the artist writing to ‘Mr. Editor’ in The Philadelphia Repository and Weekly Register a few months earlier only requested the legislative protection of the fine arts by way of engraved images, not paintings. (To ‘Mr. Editor’ by ‘A Young Artist’, The Philadelphia Repository and Weekly Register, 3 October 1801).

8 1802 Amendment (1802), Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer, http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_us_1802.

9 Sven H. A. Bruntjen, John Boydell, 1719–1804: A Study of Art Patronage and Publishing (New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc., 1985), p. 35, and pp. 61–62.

10 Carrie Rebora Barratt and Ellen G. Miles, eds., Gilbert Stuart (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), pp. 51–52.

11 Quoted by Bruntjen, John Boydell, p. 210.

12 Quoted by John Hill Morgan, ‘A Sketch of the life of Gilbert Stuart 1755–1828’, in Gilbert Stuart: An Illustrated Descriptive List of His Works Compiled by Lawrence Park (New York: William Edwin Rudge, 1926), pp. 9–70 (p. 44).

13 Barratt and Miles, Gilbert Stuart, p. 130. All the then-known portraits of Washington by Gilbert Stuart are listed in Gilbert Stuart: An Illustrated Descriptive List of His Works. Today, we know of four copies of the Lansdowne portrait: two in Washington DC (one at the National Portrait Gallery, one at the White House), one in New York at the Brooklyn Museum, and another at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

14 Barratt and Miles, Gilbert Stuart, p. 164. By the end of his life, Stuart would paint almost a hundred and twenty-five portraits of the Athenaeum type alone according to Lawrence Park, Gilbert Stuart: An Illustrated Descriptive List of His Works, although it is likely that this number is inflated. Later scholars think that the painter’s daughter, Jane Stuart, painted some of them.

15 The US-China trade was characterized by smaller ships that heavily relied on consignment, smuggling, and special orders. The Connecticut was a ship owned by James Barclay and George Simson of Philadelphia. With an estimated tonnage of 360, the Connecticut is on the list of confirmed American ships that traded legally with China, arriving at Whampoa on August 10, 1801. It was recorded back in Philadelphia in early April of 1802. None of the portraits, however, are itemized on the ship’s manifest. See Rhys Richards, ‘United States Trade with China, 1784–1814’, The American Neptune, 54: Special Supplement (1994); Libby Lai-Pik Chan with Nina Lai-Na Wan, eds., The Dragon and the Eagle: American Traders in China, A Century of Trade from 1784 to 1900 (Hong Kong: Maritime Museum, 2018).

16 Carl Crossman discusses the cost of Chinese reverse paintings to American traders, but not the American market: Carl Crossman, The Decorative Arts of the China Trade (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1991), pp. 206–216. Advertisements for Chinese paintings on glass appear in numerous newspapers at the time, unfortunately without individual prices. See the Columbian Centinel (Mass.), 14 May 1800; the New England Palladium (Mass.), 7 June 1803; the Morning Chronicle (New York), 15 April 1803. According to Crossman, another series of 10 copies of Gilbert Stuart’s Athenaeum portraits made in China were commissioned by Rhode Island merchant Edward Carrington, who was billed by the Chinese artist Foeiqua in 1805 (Crossman, p. 215).