5. The ‘Death of Chatterton’ Case: Reproductive Engraving, Stereoscopic Photography, and Copyright for Paintings ca. 1860

© 2021 Will Slauter, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0247.05

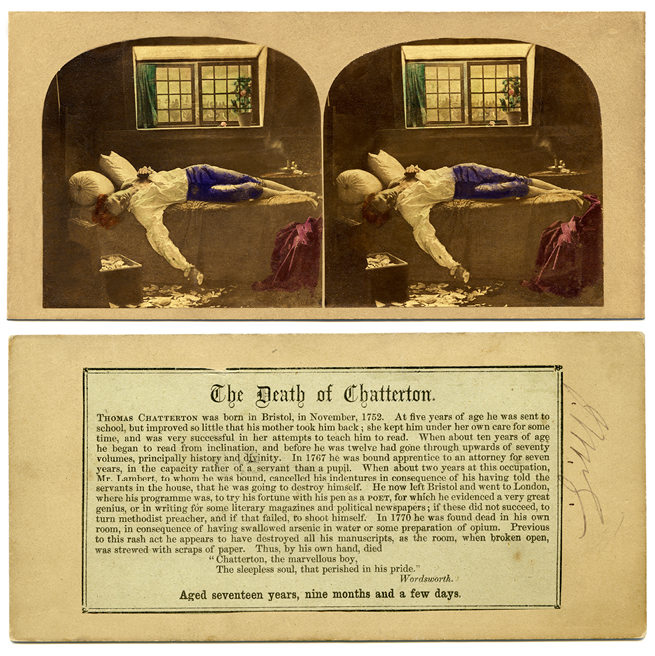

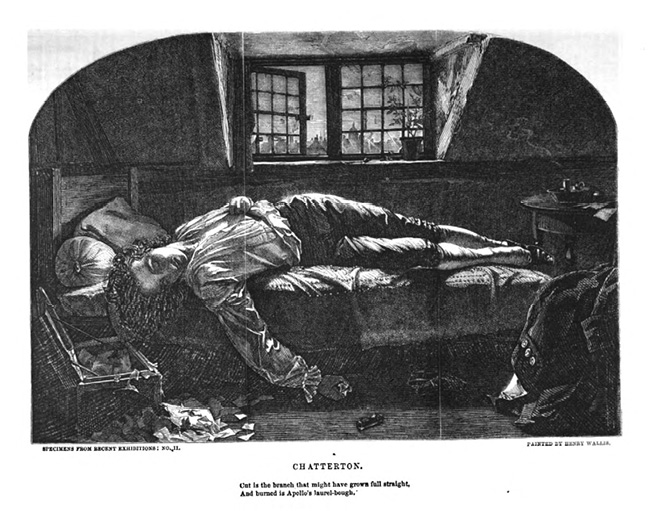

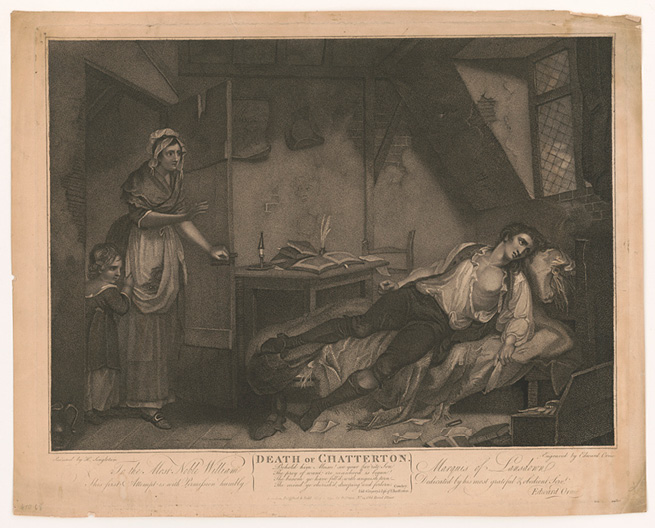

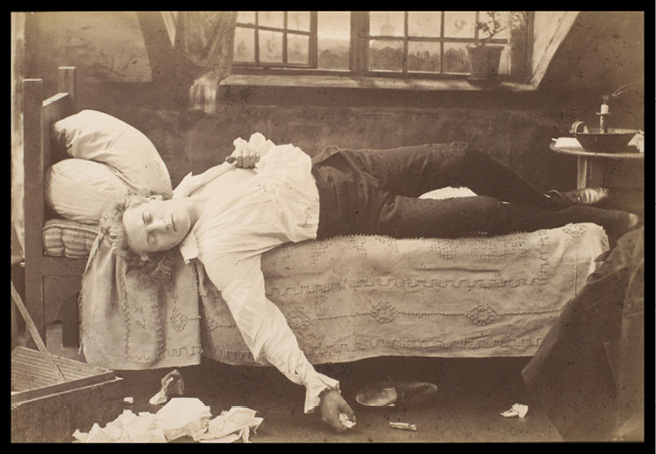

In 1859, a Dublin photographer named James Robinson visited Thomas Cranfield’s gallery on Grafton Street, just a short walk from his own studio. On temporary display at the gallery was Henry Wallis’s stunning portrayal of the death of the eighteenth-century poet Thomas Chatterton (see Figure 1). Upon viewing this painting, Robinson thought that the scene would make the perfect subject for a stereoscopic view. By taking two photographs of the same object from vantage points several centimeters apart (to account for the distance between the human eyes) and mounting these photographs side-by-side on a card so that they could be viewed through a stereoscope, it was possible to create the illusion of a three-dimensional experience. Robinson knew that a stereoscopic view could not be produced by photographing the flat surface of a painting. His idea was to recreate the scene as a tableau vivant in his own studio, using a live model, furniture, and a painted backdrop, and then take photographs of this scene. He found the idea so compelling that he began running newspaper advertisements announcing that stereo cards depicting ‘the Death of Chatterton’ would soon be available for purchase (see Figure 2).1

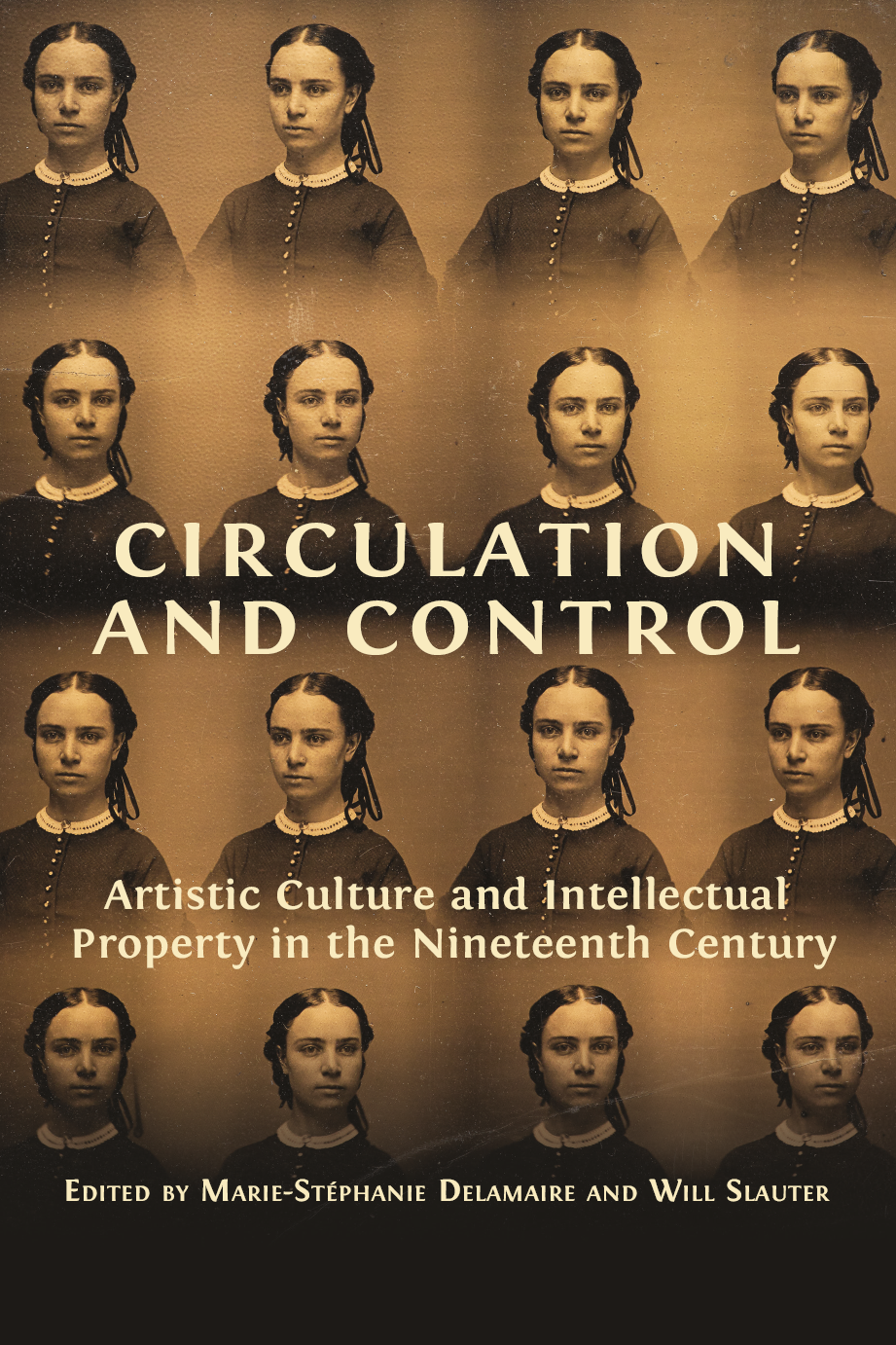

Fig. 1 Henry Wallis, Chatterton (1856), Tate, image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_Wallis_-_Chatterton_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.

Fig. 2 James Robinson, The Death of Chatterton, 1859, two hand-tinted albumen prints on paper, mounted on a stereograph card (front and back). Collection of Dr. Brian May, reproduced by kind permission.

Robinson’s advertisements infuriated Robert Turner, a print publisher based in Newcastle who claimed to have the exclusive right to make and sell reproductions of Wallis’s painting. At the time, there was no statutory copyright for paintings; along with original drawings and photographs, paintings would be protected by the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862.2 However, for decades prior to the enactment of that law, print publishers had been willing to pay the artist or owner of a painting (if the artist no longer owned the canvas) for the exclusive right to produce an engraving based on it. The resulting engraving could then be protected by copyright thanks to statutes passed in the eighteenth century.3 But Turner’s engraving did not exist yet, and Robinson insisted that the print publisher did not have the right to stop him (or anyone else) from producing his own reproduction of a painting that had been exhibited publicly. The resulting court case, Turner v. Robinson (1860), considered several important questions: did the owners of paintings enjoy a common law ‘copyright’ or other cause of legal action (such as breach of confidence) that they could use to stop others from reproducing an artwork? If a common law ‘copyright’ did exist, would it be lost when a painting was exhibited in a public gallery or published as an engraving?4

In the years before and after 1862, photographers struggled to obtain recognition as ‘authors’ whose works were worthy of copyright protection, rather than as operators of a ‘mechanical’ process. But Turner v. Robinson is a reminder that photographers were also defendants in suits brought by print publishers who claimed exclusive rights over a particular painting.5 The case exposed growing tensions within the market for reproductions of fine art, and it led the court to inquire into prevailing commercial arrangements and institutional norms, such as the rules related to copying in public galleries. The dispute raised the thorny question of what constituted a ‘copy’ of a visual work — especially if it were rendered in a new medium — at a crucial transition period in the history of photography and its relationship to the other arts. It was a hinge moment not only in the development of photography as a business and a generator of new forms of visual culture (such as stereoscopic views) but also in the use of photography to document artworks and make reproductions available to a wider public.

This chapter takes a closer look at Turner v. Robinson, not so much for its importance as a legal precedent, but for what the dispute reveals about the shifting artistic and commercial landscape in which photographers like Robinson and print publishers like Turner were operating. The chapter draws on contemporary reports of court proceedings — as well as more obscure newspaper accounts, advertisements, and exhibition catalogues — to reconstruct the story of the litigation and its protagonists. It also draws on detailed research by collectors and curators of stereographs and specialists of the history of painting, printmaking, and photography. In doing so, the chapter seeks to situate Robinson’s actions and Turner’s response in relation to wider cultural and technological trends. It ends by considering the significance of the case and what effects the judgment may have had on contemporary artistic and commercial practices.

The Poet and the Painting

By the time Wallis exhibited his painting in 1856, accounts of Thomas Chatterton’s short life and tragic death had made him something of a cult figure for writers and artists, from William Wordsworth and John Keats to the Pre-Raphaelite circle of painters with which Wallis was associated. The usual story is that Chatterton committed suicide in a London garret in 1770. He was seventeen, poor, and largely unknown, despite having published some of his work in newspapers. His unique literary imagination and immense desire for recognition had ended in tragedy. As a boy growing up in Bristol, Chatterton collected remnants of old manuscripts from St. Mary Redcliffe Church and devoured collections of medieval English verse. He was also inspired by the Scottish poet James MacPherson, who in the 1760s published a series of epics that he claimed to be translations from ancient Gaelic works by the legendary Irish poet Ossian. For his part, Chatterton composed a series of mock-medieval writings that he presented as the work of a fifteenth-century figure named Thomas Rowley. After testing out his forged manuscripts on some local antiquarians, Chatterton sought out patronage at the highest levels of the British literary world, writing first to the publisher James Dodsley and then to the writer Horace Walpole, whose own Castle of Otranto (1764) Chatterton admired. Walpole initially expressed interest, but after discovering Chatterton’s low social status he suspected a trap. Walpole showed the manuscripts to others who concurred that they were forgeries. Disappointed and angry at Walpole, Chatterton moved to London, where he began to eke out a living contributing political essays and satires to local newspapers. Things were looking up until another potential patron — William Beckford, the lord mayor and supporter of the radical John Wilkes — died suddenly. Chatterton desperately took his own life.6 In line with this story, Wallis inscribed a quotation from Christopher Marlowe’s Elizabethan tragedy Doctor Faustus on the frame of his painting of Chatterton: ‘Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight,/ And burned is Apollo’s laurel bough’.7

The literary scholar Nick Groom has challenged the assumption that Chatterton committed suicide, suggesting instead that he died of an accidental drug overdose. In Groom’s words, ‘despite the juggernaut of myth that began almost immediately to roll, obliterating history, this was no proto-Romantic suicide of a starving poet in a friendless garret, his genius cruelly unrecognized’.8 Yet there is no denying that Chatterton became a hero of the English romantics. A ‘Monody on the Death of Chatterton’ was one of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s earliest poems, and one he reworked several times over the course of his career. William Wordsworth, in ‘Resolution and Independence’(1807), described Chatterton as ‘the marvellous Boy,/ The sleepless Soul that perished in his pride’.9 John Keats, who dedicated his long poem Endymion (1818) to Chatterton, went so far as to claim that the fallen poet was ‘the purest writer in the English language’.10 Further admirers included Robert Browning and Dante Gabriel Rosetti. The writer George Meredith actually posed as Chatterton for Wallis’s painting. Unfortunately, Wallis soon ran off with Meredith’s wife, inspiring Meredith to write a series of fifty sonnets that was published under the title Modern Love in 1862.11

Chatterton is now one of Wallis’s best-known works, and it was already somewhat famous when James Robinson saw it in Dublin in 1859. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856, the painting was then featured in the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857, a huge event that drew unprecedented crowds. The critic John Ruskin declared Wallis’s painting ‘faultless and wonderful’ and invited viewers to ‘examine it inch by inch: it is one of the pictures which intend, and accomplish, the entire placing before your eyes of an actual fact — and that a solemn one’.12 Whether he read Ruskin’s review or not, Robinson certainly examined the painting ‘inch by inch’, and he spied an opportunity to profit from the fast-growing demand for stereoscopic views.

The Rise of Stereography

After stereograph cards and viewers mesmerized visitors to the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851, opticians tinkered with devices and burgeoning photography firms began to develop products within the reach of middle-class consumers.13 Meanwhile, uncertainty about the patent claims of William Fox Talbot was resolved at the end of 1854, enabling the widespread use of the wet plate collodion process.14 Since it could be used to create multiple positive prints on paper, the collodion process is what made possible the mass commercialization of photographs in the form of stereograph cards and the small-format photographs known as cartes de visite. Numerous photography studios were started in the late 1850s. In London alone, it has been estimated that the number grew from sixty-six in 1855 to 284 in 1864.15 The London Stereoscopic Company, founded in 1854, had the ambition (according to the company’s own slogan) to place ‘a Stereoscope in Every Home’. By 1856, the same year that Wallis first exhibited Chatterton, the London Stereoscopic Company claimed to have sold more than 500,000 viewers and have a catalog of over 10,000 stereograph cards. Two years later, they boasted 100,000 different stereo views.16 Stereography transformed the visual landscape: suddenly a dazzling range of images were available in a format that was both exciting and affordable to middle-class families. Purchasing, exchanging, and viewing stereographs became a craze (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3 An example of a Brewster-style stereoscope from around 1870, Museo della scienza e della tecnologia, Milano, CC-BY-SA-4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IGB_006055_Visore_stereoscopico_portatile_Museo_scienza_e_tecnologia_Milano.jpg.

Robinson’s business was tiny compared to the London Stereoscopic Company, but he had a good eye: the scene depicted in Wallis’s painting was well-suited to the new medium. Viewers of the painting were invited to peer into the bedroom of the young Chatterton, and even to assume the perspective of the landlady who in 1770 opened the door to discover his body. Why not offer spectators the titillating illusion of entering the arch-ceilinged room? Robinson had been familiar with stereoscopy since at least 1853, when the catalogue for the Dublin International Exhibition listed him exhibiting ‘stereoscopes of various forms, with diagrams and proofs; cameras for the calotype, daguerreotype and collodion processes; various specimens of photography on paper and on glass’.17 That Robinson exhibited photographic apparatuses alongside specimens produced using a range of materials was not unusual for international exhibitions meant to showcase technical innovations. Although relatively little is known about Robinson, it should not be assumed that he was just a shady figure trying to make an easy profit by ‘copying’ Wallis’s painting (and ‘copy’ was a word that Robinson found problematic, as we shall see).18 Scattered evidence from contemporary newspaper notices and exhibition catalogues as well as extant portraits by him in major collections reveal that over time Robinson built a successful business that combined studio photography and the manufacture and sale of cameras, lenses, and related materials.19 The lengths he was willing to go to defend himself against Turner, and the legal expenses that would have been involved in the initial trial and the appeal, also suggest that he considered it important to take a public stand at a moment when copyright reform, and the competing interests of engravers and photographers, were being actively discussed.20

By the mid-1840s Robinson was advertising that his ‘Polytechnic Museum’ on Grafton Street stocked a range of chemicals and scientific apparatuses, including microscopes and telescopes, opera and racing glasses, magic lanterns, and ‘an extraordinary collection of rational and Amusing Toys, Novelties in Mechanism, Drawing-room Recreations, &c’.21 As photography developed, Robinson changed the name of his establishment to ‘Polytechnic Museum and Photographic Galleries’ and sometime in the late 1850s he began to operate a portrait studio. An ambrotype print of a group portrait that has been attributed to Robinson and dated to approximately 1858 was included in a 2010 exhibition at the Gallery of Photography, Ireland.22 The National Portrait Gallery in London has several carte-de-visite portraits by Robinson that curators date to the 1860s; the cards are stamped J. Robinson, Dublin.23 Appropriately enough, after the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862 extended copyright to photographs, Robinson registered some of his portraits. Sometime in the 1870s his sons joined him in the business, and by 1884 they added a London location in Regent Street, while retaining the Dublin address (where James Robinson seems to have remained).24

In any case, newspaper reports indicate that by 1859 Robinson was an active member of the Dublin Photographic Society, where he showed some of his own work in addition to showcasing the achievements of more well-known photographers. In March 1859, just before the dispute with Turner, he exhibited magic lantern slides of some of Francis Frith’s famous views of Egyptian monuments.25 By this time such slides were being marketed by the London firm of Negretti and Zambra, and it seems likely that Robinson did not think he was doing anything wrong by showing them to fellow members of the Dublin Photographic Society.26 He was clearly a practitioner who was up to date with the latest technology, practices, and subject matter of various photographic processes.

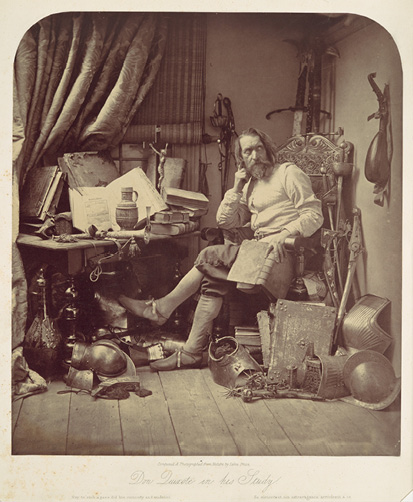

Photography and tableaux vivants

Robinson’s idea to stage Chatterton’s death scene as a tableau vivant and then photograph it did not occur to him suddenly, nor was it some sort of clever subterfuge to avoid directly photographing the canvas. Robinson would have known that writers and scenes from literary and dramatic works were popular subjects for staged photographs, not least among practitioners who had trained as painters and sought to elevate photography to an art form. A prominent example was William Frederick Lake Price’s Don Quixote in his Study, which was shown at several exhibitions in the late 1850s and made available as a stereo card (see Figure 4).27 As evidenced by this and other contemporary stereographs, cluttered interiors enhanced the pleasure of the optical illusion by allowing viewers to inspect each object in turn. Denis Pellerin, a curator and historian of photography, put it this way: ‘stereoscopy loves clutter and photographers, who knew their customers well, made the most of it in their compositions’.28 Working with Brian May, who has a unique collection of Victorian stereographs, Pellerin has shown that the phenomenon of restaging paintings to produce stereoscopic views was quite common in the 1850s and 1860s. Pellerin and May have suggested that much of the appeal came from the idea of making works of art more accessible to the public and allowing individuals to spend time intensely looking at all the details.29 In the case of Wallis’s painting, there was much to work with: Chatterton’s partly undressed body stretched out on the bed in a Pietà-like position, his arm dangling down to the floor, his hand still gripping a crumpled manuscript, the vial of poison a few inches away, the chest full of disorderly papers, the recently extinguished candle on the table, the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral and the London cityscape visible through the window — all of these objects could be inspected as viewers took a virtual tour of the room. Those who looked closely at the painting could even see the name of the newspaper on the floor — the Middlesex Journal; or Chronicle of Liberty — to which Chatterton had contributed.30

As a member of a local photographic society and dealer in all things related to the art, Robinson was almost certainly aware of a cultural trend among both professionals and amateurs in which people would recreate scenes from paintings as tableaux vivants for the camera.31 Robinson may have spied a business opportunity, but he was also up for a technical challenge in line with contemporary aesthetic trends. In his affidavit, Robinson stated that he hired a scene painter to create a backdrop simulating the garret with its window. He placed the bed, table, chest, and other objects as he remembered seeing them in Wallis’s painting, and had his own assistant pose as Chatterton.32 However, given how closely Robinson’s stereoscopic view reproduced numerous details from the painting, the court would not be satisfied by Robinson’s claim that he worked entirely from memory, and it may well be that he relied in part on an existing wood engraving (discussed later in this chapter).

Fig. 4 William Frederick Lake Price, Don Quixote in his Study, 1857, albumen silver print from glass negative, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, CC0 1.0, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/271528.

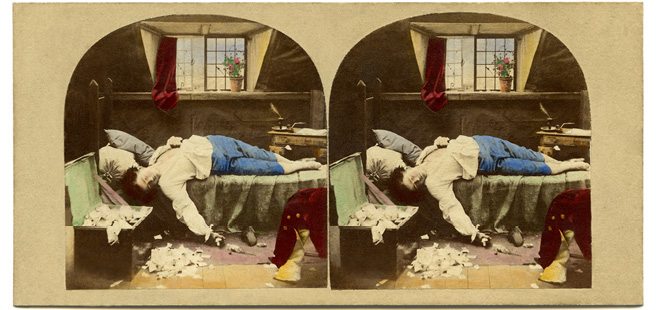

Reproductive Engravings and the Threat of Photography

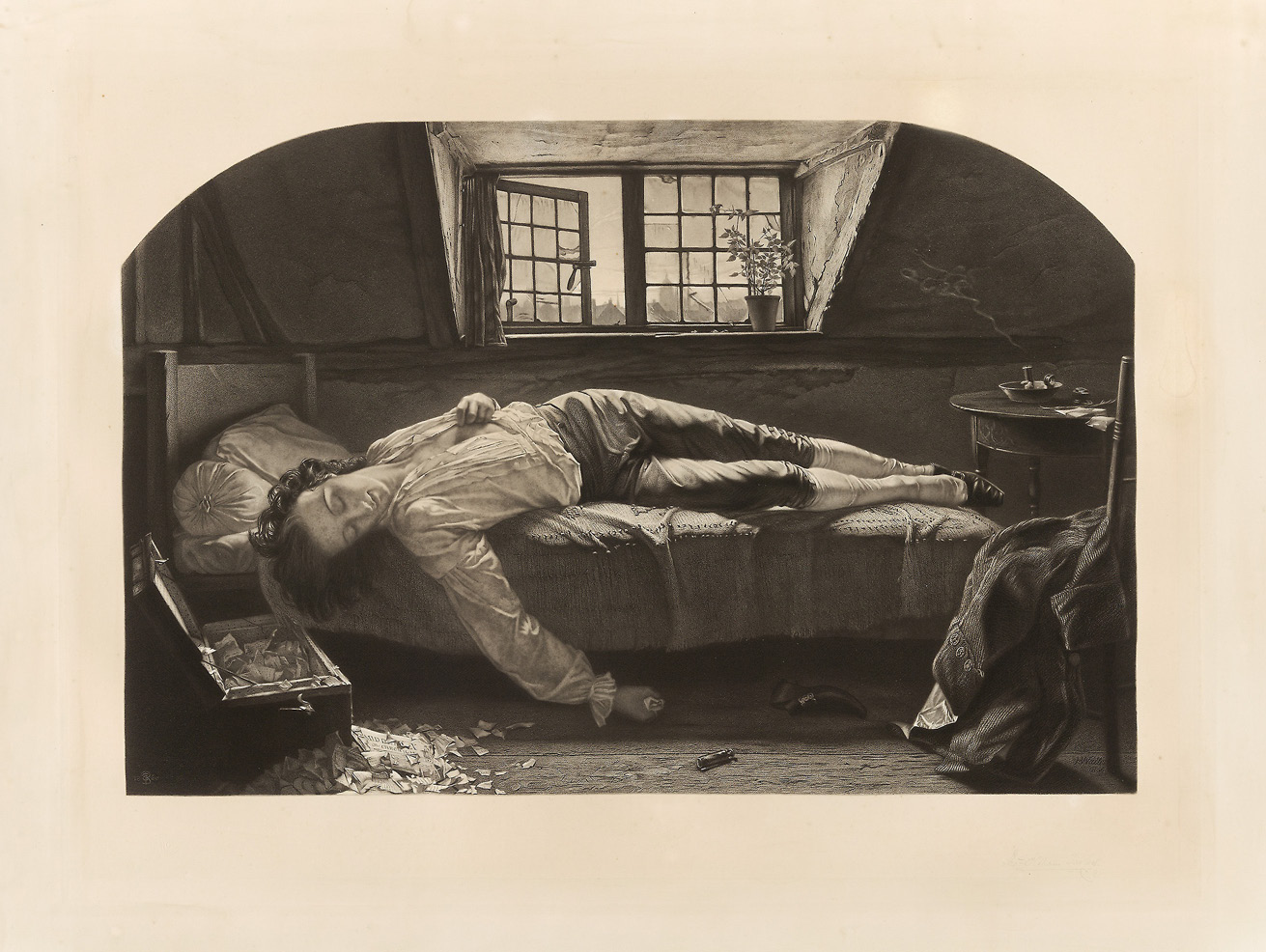

Wallis’s painting was on display at Cranfield’s Gallery for approximately three weeks in April 1859. The exhibition had been arranged by Turner, who was following what was by then a common business model among print sellers: charging a small admission price to see the original painting, then using these viewings to solicit subscribers to the engraved reproduction. Turner had commissioned the highly-respected engraver Thomas Oldham Barlow to carry out the work. But on 22 April, Robinson announced in Saunders’s News-Letter, a major Dublin newspaper, that his stereo cards of The Death of Chatterton would be ready for sale the following Monday; plain copies would cost 1s. 6d. and hand-colored cards 2s. 6d.33 For Turner, the advertisements must have seemed like a deliberate provocation. Print publishers were growing increasingly concerned about how photography could harm the market for engravings, and here was a photographer who worked in the same street where the painting was being displayed, openly advertising his own version in the local newspaper. Because the purpose of the Dublin exhibition was to attract subscribers (and it was the first such showing), Barlow had not yet begun the time-consuming and painstaking process of producing his plate. Not only were Robinson’s photographs first to market, but they were also significantly cheaper than a quality print of the sort Turner was planning. Barlow’s engraving was a mezzotint, with additional tonal effects produced through stipple engraving and etching, a process often referred to as ‘mixed-method engraving’(see Figure 5).34 Although Barlow inserted the year 1860 next to his monogram in the engraving, he did not actually deliver the finished plate to Turner until 1862, a delay that led Turner to sue him (unsuccessfully, it turned out) for violating their contract.35 In any case, when the engraving was advertised for sale in the spring of 1862, standard prints cost 2 guineas, almost thirty times as much as Robinson’s uncolored stereo cards and roughly seventeen times as much as the colored ones (artist’s proofs of the engraving cost much more — 8 guineas).36

Given this disparity in price, the potential clientele for the engraving was more limited than that of Robinson’s stereoscopic view, and one could argue that they were two different products aimed at two different markets. Indeed, evidence presented to the court stated that Turner had circulated prospectuses for the engraving ‘among the nobility and gentry of Ireland’, and that the admission price of 6d. for viewing the painting at Cranfield’s Gallery had been designed to avoid the kinds of crowds that might deter potential subscribers from entering the gallery in the first place.37 But print publishers like Turner were concerned with how photographic reproductions of works of art could cut into the sales of quality engravings, and there is some evidence that this threat was beginning to reduce the amounts they were willing to pay painters for so-called ‘engraving rights’.38

Fig. 5 Thomas Oldham Barlow (after Henry Wallis), The Death of Chatterton, 1860, Art Institute of Chicago, CCO Public Domain, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/148404/the-death-of-chatterton.

Turner had in fact anticipated that photographers might be tempted by Wallis’s painting, and on 2 April he had the following notice published in Saunders’s News-Letter:

CAUTION TO PHOTOGRAPHERS. –Mr. Turner hereby intimates to Photographic Artists and others, that proceedings at law will be immediately instituted against anyone infringing upon his copyright by means of Photography or otherwise. 32, Grey-street, Newcastle, April 1st, 1859.39

A short editorial in the same newspaper sympathized with ‘the eminent Robert Turner’ and other print publishers who had ‘very properly taken alarm at the extent to which copies of the finest engravings are multiplied by means of photography’.40 But since Barlow’s engraving did not exist yet, Robinson could not have used photography to create copies of it. Still, Turner saw Robinson’s advertisements for The Death of Chatterton as proof that the photographer was infringing his right to sell reproductions of the painting. Turner’s solicitors wrote to Robinson requesting that he desist from producing or selling any more copies of The Death of Chatterton, and threatening legal proceedings ‘for pirating said work, and publishing the same’.41 Turner also complained about Robinson’s use of the title The Death of Chatterton, which Turner had been using to advertise Wallis’s painting and his forthcoming print.42 Turner’s counsel argued that Robinson had ‘increased the interest and value of the photograph by representing that it was a copy of the original picture, which he clearly led the public to understand’.43

Robinson insisted that his stereoscopic views were not copied directly from the painting and that Turner had no right to interfere in his business. In response to the letter from Turner’s solicitors, he published a new advertisement defending himself against the allegations of ‘piracy’:

THE DEATH OF CHATTERTON. —

JAMES ROBINSON begs to announce that he has now ready for Sale the most wonderfully effective and beautiful Stereoscopic Pictures ever yet produced, Photographed by him from the living model, representing

THE LAST MOMENT AND DEATH OF THE POET CHATTERTON.

1s. 6d. each plain, 2s. 6d. coloured.

J.R. begs most emphatically to deny having copied or pirated his Stereoscopic Slides from any Picture exhibited in Dublin; and it must be obvious to any one that has the slightest knowledge of the principles of the stereoscope that pictures such as he has produced could not be obtained from the flat surface of any painting or engraving. Polytechnic Museum and Photographic Galleries.

65 GRAFTON-STREET44

This notice appeared in Saunders’s News-Letter, immediately underneath an advertisement announcing the public’s final opportunity to view Wallis’s painting at Cranfield’s Gallery. Such dueling newspaper notices no doubt increased interest in Wallis’s painting and demand for reproductions of it. The initial trial and the appeal were thoroughly covered in the newspapers and included several days of hearings spread over many months from May 1859 through June 1860 — generating publicity for both Turner and Robinson. In fact, the day after Turner’s solicitors wrote to Robinson, Cranfield informed the public that Wallis’s painting might be needed in court as a result of Turner having commenced legal proceedings against Robinson ‘for infringement on his copyright of the Picture of ‘THE DEATH OF CHATTERTON’; consequently, the painting would remain on view for a few additional days at Cranfield’s.45 Once hearings began, Turner was able to enjoy newspaper reports that referred to him as ‘the celebrated publisher of engravings’; newspaper readers also learned that ‘the beautiful painting was exhibited in court, and was greatly admired by the bar and a very crowded audience’.46

Robinson sought support from local photographers. Conveniently for him, the Dublin Photographic Society was scheduled to meet the same evening that he ran the newspaper notice quoted earlier in which he denied the allegation of ‘piracy’. After displaying his stereograph of The Death of Chatterton, Robinson announced to the Photographic Society that he was being sued for the ‘alleged piracy of a celebrated picture of this name’, but that his work was ‘no copy’; he asserted that he would defend his rights in court, to the apparent approbation of those present.47 Turner would not give up either. His petition to the Irish Court of Chancery claimed that Robinson’s stereographs were ‘piratical imitations and copies of the design and subject’ of Wallis’s painting, and requested that the court issue an injunction to stop Robinson from exhibiting, publishing, or selling his photographs ‘or any other picture, print or engraving, being an imitation of, or a copy from the design of the said picture’.48

Turner’s Stand on Behalf of Engraving Rights

The case came before the Master of the Rolls in Ireland, the second-highest ranking judge in the Court of Chancery after the Lord Chancellor. The current Master of the Rolls was Thomas Berry Cusack Smith, who was known as a learned and conscientious judge but also for his blunt and colorful courtroom demeaner. In a previous role as Attorney-General for Ireland, Smith led the prosecution of Daniel O’Connell and his followers in 1843–1844, and O’Connell gave him the nicknames ‘Alphabet Smith’ and ‘the Vinegar Cruet’.49 Smith’s personality also seems to have been a factor in Turner v. Robinson: as we shall see, the defense objected to the strong language that the judge used to characterize Robinson’s actions, and to the way Smith personally gathered evidence that he thought would support Turner’s case.

On what basis did Turner claim a right to stop Robinson or anyone else from reproducing Wallis’s painting? In an arrangement that was common by this time, Turner had contracted with the owner of the painting for the right to produce an engraving, as well as the right to publicly display the painting to attract subscribers.50 Wallis was no longer the owner, as he had sold the painting to Augustus Leopold Egg, a fellow painter and the organizer of the 1857 Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition. Turner purchased from Egg ‘the copyright, or the sole right to engrave and publish an engraving’ of Wallis’s painting.51 Although there was no statutory copyright for paintings, for decades artists (and, as in the case of Egg, owners of paintings) had nonetheless sold the exclusive right to produce engravings of their paintings under the so-called Engravers’ Copyright Acts passed in the eighteenth century. Also, purchasers of paintings tended to insist that the right to authorize engravings passed to them as part and parcel of their ownership of the physical canvas; moreover, since they controlled physical access to the canvas, they were effectively able to decide whether to allow engravings and on what terms. For certain well-known painters, payments for engraving rights could represent a significant portion of their income, sometimes as much as half.52

At trial Turner’s counsel gave the example of Sir Edwin Henry Landseer’s pair of paintings entitled Time of Peace and Time of War (1846). Counsel claimed that while Landseer’s paintings sold for £1,000, the engraving rights went for £2,500.53 In the present case, it was reported that Egg had purchased Wallis’s painting for 100 guineas (the equivalent of £105) and that Turner had paid Egg £150 for the engraving rights.54 The contract also provided other benefits for Egg as the owner of the painting. He was to receive twelve artist’s proofs of Barlow’s engraving for his own use, and in the event that Barlow died or was unable to finish the work, Egg had the right to approve Turner’s choice for a new engraver. The engraving plate also had to be delivered to Egg, which would effectively give him control over subsequent prints from that plate.55 Although not specified in the written agreement, Turner also included a prominent dedication to Egg on the print itself.56

Controlling access to the physical painting had long been crucial to securing a print publisher’s investments, especially before the print was put on sale. Once an engraving of the painting was published, it could be protected by the Engravers’ Copyright Acts. These statutes could be used to stop others from copying directly from an existing engraving, but the situation was more problematic in cases where a second engraver made an independent engraving from the original painting. The judgment in De Berenger v. Wheble (1819) suggested that a print publisher did not have a legally enforceable monopoly on all reproductions of a painting. In that case, a print publisher had purchased the sole right to make engravings of two paintings by Philip Reinagle. He hired an engraver to carry out the work, but the engraver made a sketch of the original painting and used this sketch to reproduce further engravings beyond the one the publisher had commissioned. These additional prints were then published in a periodical called the Sporting Magazine. The print publisher sued the engraver for copyright infringement, but the court refused the injunction on the grounds that these prints were copies of the painting rather than the first set of engravings. The court was keen to ensure that the copyright on the first reproduction did not impede further reproductions, because, in the words of Lord Chief Justice Abbott ‘it would destroy all competition in the art [of engraving] to extend the monopoly to the painting itself’.57

This decision suggested the importance of strictly controlling access to the painting, and over time the law related to breach of trust or confidence provided a means of restricting the activity of individuals who were given temporary access to an artwork. If their access was understood to preclude making copies or even publishing a written description of the artwork (in cases where the creator wanted the very existence of the work to remain unknown), then they could be restrained from doing so, as was decided in the case of Prince Albert v. Strange (1849). Prince Albert had produced a series of etchings and entrusted the copper plates to a printer to make copies for the royal household’s private enjoyment. Unfortunately, an employee of the printer made unauthorized copies and sold them to another individual who announced a public exhibition of the etchings and prepared a printed catalogue with descriptions of each work. Prince Albert sued to prevent the exhibition and the publication of the catalogue. At first instance the court held that the creator of an artwork, like the author of a letter or other unpublished manuscript, had a common law property right that enabled them to decide when and how to publish the work or make its existence known to the public. The court determined that this right enabled Prince Albert to prohibit not only the exhibition, but also the publication of written descriptions of the etchings. Prince Albert v. Strange thus confirmed that common law ‘copyright’ existed for unpublished works of art just as it did for unpublished writings. But on appeal the Lord Chancellor added a second grounds for the injunction: since the defendant must have obtained the copies surreptitiously, he was in breach of trust or confidence as well as in violation of Prince Albert’s common law property right in the etchings.58

For print publishers who sought to stop others from producing an independent engraving from the same painting, it was important to seek an exclusive contract with the owner of the painting, just as Turner had done with Egg. But what was Turner to do about members of the public (such as Robinson) who walked into a gallery and saw the painting on display? One solution would have been to wait until the engraving was completed before exhibiting the painting. A quality engraving took many months to produce. If by the time a major painting was exhibited a print was already on sale and protected by its own copyright (which covered the ‘design’ that had been engraved, and thus indirectly provided some protection for the painting), then rival publishers would be much less likely to invest in making a competing version even if they had access to the painting.59 In an 1853 treatise on the current state of copyright law for artistic works, the barrister D. Roberton Blaine advised print publishers to proceed cautiously. He warned that if a painting or drawing were exhibited — either privately or publicly — before the engraving was published, ‘then it would seem that the design is public property; and that the work of the engraver, exclusive of the design, is alone entitled to copyright; in other words, that any one may engrave the subject [i.e. the original painting or drawing] provided they do not copy it from the engraving’.60

Although Turner could have waited for Barlow to finish his work before exhibiting Wallis’s painting in Dublin, proceeding in this way would have entailed significantly more risk, because exhibitions aimed at attracting subscribers were a means of gauging interest in the engraving.61 Moreover, in this case Wallis’s painting had already been featured in two major public exhibitions. Complicating matters still further, Wallis had already authorized the publication of a wood engraving illustration of his painting in the National Magazine in 1856 (see Figure 6).62 The public exhibitions and the authorized engraving meant that the outcome of the case was uncertain. Turner’s counsel had to persuade the court that, contrary to what Blaine had written in his 1853 treatise, and contrary to what Robinson’s counsel argued, the design of Wallis’s painting was not ‘public property’ just because it had already been exhibited and reproduced in a magazine.

Fig. 6 Wood engraving of Wallis’s Chatterton, in The National Magazine, edited by John Saunders and Westland Marston, 1 (1857), p. 33, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112109516473&view=1up&seq=49.

The fact that there was no statutory copyright for paintings meant that Turner’s counsel had to argue the case on the grounds of common law property rights in unpublished works and/or breach of confidence. With respect to the first grounds, Robinson’s counsel conceded that Wallis might have enjoyed a common law property right in his painting that would enable him to restrict copying before publication, but not after. Therefore, it became crucial for the court to determine whether the wood engraving or the public exhibitions constituted the sort of ‘publication’ that would terminate the artist’s common law rights. Meanwhile, protection against breach of confidence would require showing that Robinson’s viewing of the painting was subject to conditions. The case of Prince Albert v. Strange confirmed that it was a breach of confidence to make unauthorized copies of a work when the creator wanted them to remain private, but could the same rule apply to a painting that was reproduced in a magazine, shown in major public exhibitions, and described in published reviews?

Robinson’s Defense

Just as Turner could be seen as taking a stand on behalf of the interests of the engraving trade, Robinson seems to have seen himself as defending the rights of photographers to co-exist with print publishers and offer their own reproductions of works of art. As his counsel reminded the court, Robinson did not sell his stereographs in secret. He advertised them openly, and when accused of piracy was confident enough to publish a new advertisement explaining that his photographs were not taken from the painting but from a living model.63 Robinson also defended what he saw as the added value that stereoscopic photography brought to the viewer’s experience of an artwork. As he explained in an affidavit, ‘the Stereoscopic Pictures were only designed for the instrument, the Stereoscope, and when seen through it, produced an effect, which is not produced by the painting, and which cannot be produced by any painting’.64 Similarly, some of Robinson’s newspaper advertisements highlighted the fact that his photographs ‘when seen in the Stereoscope stand out in bold relief, producing the most extraordinary effect’.65

Robinson’s counsel developed several arguments in his defense. First, they questioned Turner’s standing to sue. Turner was neither the artist nor the owner of the canvas, so he had to prove that he had acquired exclusive rights from one or the other. The final judgment suggests that Smith, the Master of the Rolls, took it for granted that the purchaser of an artwork automatically obtained any common law rights to exclude others from making copies.66 But newspaper reports of proceedings suggest that Smith expressed doubts about whether Wallis had in fact transferred the ‘copyright’ to Egg as part of the initial sale. As a precaution, Turner had asked Egg to write to Wallis to make sure he did not oppose the engraving. Wallis replied that ‘the sum that is to be given for the copyright appears to me to be very mild’, but that if Turner thought it was reasonable then he agreed to the engraving.67 Interestingly, Wallis also asked Egg to ‘request that the picture, in being advertised, may not be called The Death of Chatterton but Chatterton Dead’.68 Why Wallis objected to The Death of Chatterton is not known, but when the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856 the title listed in the catalogue was simply Chatterton.69 Smith interpreted Wallis’s request concerning the title and his explicit assent to the engraving in this letter to indicate that Wallis ‘had not previously sold the copyright’.70 Smith was also troubled by the fact that £50 out of the £150 that Turner promised to Egg were in fact delivered to Wallis. According to newspaper reports of the case, Smith stated several times that this payment seemed to be for the engraving right, suggesting that Egg had not automatically acquired this right when he took possession of the painting.71 Turner was examined in court and his testimony, as reported by a Dublin newspaper, explained why he felt the need to ask Wallis for permission:

I swore before, and I swear again, that Mr. Wallis sold the copyright when he sold the picture, and the exclusive right to print, engrave and publish same; that is the custom of the trade, the copyright goes with the picture unless it is reserved; Mr. Egg sold me the copyright; I applied for Mr. Wallis’s consent merely to strengthen my case; I wanted his consent to the sale of the copyright by Egg to me; my reason for seeking the artist’s consent was that the point has never been decided in our courts.72

Turner’s testimony confirms that the litigation was prompted by a desire to clarify the state of common law protection for paintings in an art market that was evolving as a result of the advent of photography. Although engraving rights were recognized as a ‘custom of the trade’ and it was generally understood that they were transferred upon sale of the painting, the way photography threatened to disrupt the trade made judicial recognition of common law copyright in paintings urgent. In the final judgement, Smith mentioned that Wallis assented in writing to Egg’s contract with Turner; however, he did not state that this consent was necessary for Egg to be able to transfer the rights to Turner. Ultimately, the court found that Turner had legitimate title and standing to sue for piracy as a ‘bailee for hire’ who enjoyed property in the painting for the duration and the purpose specified in his contract with Egg.73

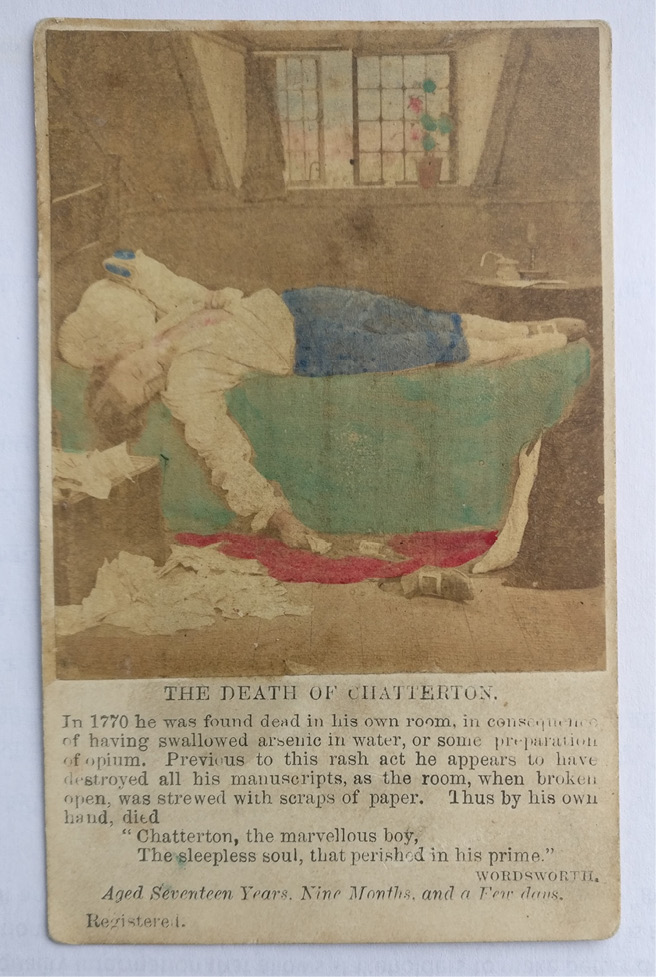

The second argument for the defense was that Wallis’s work was not original and therefore could not be protected against copying. Robinson drew the court’s attention to an engraving produced in 1794 by Edward Orme after a painting (now lost) by Henry Singleton (see Figure 7). In an affidavit, Robinson argued that Wallis took ‘the idea and design of his picture’ from Orme’s engraving. He pointed to the similar attic setting with a window above the bed, ‘the body in the same costume, and nearly in the same position, the poison bottle on the floor, the box of torn papers, the table, and all the minor details observable in Mr. Wallis’ picture’.74 Turner responded with an affidavit by Wallis stating that his painting was his ‘original design and conception’ and that he had never previously seen or heard of any picture by another artist representing the same subject.75 The Orme engraving was produced in court, but from the bench Smith asserted that ‘it was absurd to say that this engraving suggested to Mr. Wallis the idea of the picture’.76

Fig. 7 Edward Orme, after Henry Singleton, Death of Chatterton, 1794. Library of Congress. Public Domain, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003674219/.

The defense’s third argument was that Wallis’s work had already been published; therefore, any common law property rights in the work had been terminated. During the preliminary hearings in the Rolls Court, Smith stated that irrespective of the question of an artist’s property rights at common law, he was fairly certain that the court had a duty to intervene because Robinson’s actions constituted fraud. Robinson was given the privilege of viewing the painting at Cranfield’s Gallery and took advantage of that privilege to produce unauthorized copies of the painting.77 If Smith had issued an injunction solely on the grounds of breach of confidence, as the Court of Appeal would later do, he could have avoided the whole question of what constituted publication in the case of paintings. But he seems to have been genuinely interested in the question and aware of its importance for painters, print publishers, and photographers. He warned Robinson that he was leaning heavily toward issuing an injunction, but allowing the case to go forward so that both sides could present evidence.78 The legal definition of publication for a painting thus became a central aspect of the case. In the case of literary works, the law was clear: unpublished works were protected by the common law whereas published works could only be protected by the copyright statutes. Since there was no statutory copyright for paintings, the question of what constituted ‘publication’ was paramount.

What Constitutes ‘Publication’ of a Painting?

Robinson’s lead counsel, a Mr. Sullivan, contended that Wallis’s painting had been ‘published’ at least four times: in the National Magazine, at the Royal Academy, at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, and at Cranfield’s Gallery.79 He said that the magazine had given wide circulation to the design of Wallis’s painting, and insisted that ‘it had been held over and over again, that when an engraving was published and printed anybody could publish an engraving after the same subject if it were taken from the picture itself’.80 With respect to the exhibitions, he argued that these were open to the public upon payment of a fee, without any restrictions attached. Referring to the exhibition of Wallis’s painting at the Royal Academy, Sullivan proposed that anyone ‘could go to the Academy and copy, and, if clever enough, carry away in his recollection the features of the picture, so as to enable him to copy it’.81

Turner’s counsel argued that Wallis’s painting had never been published in an unqualified way. Wallis had given permission to the editors of the National Magazine to publish a wood engraving, but his consent in this one instance could not be seen as a dedication to the public. In addition, the engraving in the magazine could not be considered a publication of the painting itself. Turner’s counsel noted that many major paintings were now being reproduced in periodicals such as the Art Journal, and it would be a serious detriment to the owners of paintings if these illustrations were held to be publications of the paintings.82 Although this point does not seem to have been elaborated in court, wood engravings were produced with a different process (relief rather than intaglio) and using different techniques and materials (wood rather than copper or steel), creating very different products. The relief process enabled the main features of an artwork to be reproduced as a series of intricate lines, but the carved-out areas of the woodblock would simply appear as white in the finished print. By contrast, the addition of hatchings and other techniques on a metal plate allowed the engraver to approximate effects of light and texture to a much greater extent. In that sense, specialists of nineteenth-century prints have distinguished between ‘illustrations’ (such as might be found in a periodical) and ‘reproductive engravings’ of the sort that Turner published.83 In addition, wood engravings involved the use of several blocks, which were carved individually (often by several people working simultaneously) and then bolted together before being sent through the press. The borders between the individual wood blocks can often be seen in the printed image (note the clear vertical lines in Figure 6). Such block lines were characteristic of wood-engravings in the illustrated press. They were cheaper to produce and not as finely detailed as intaglio prints of the sort that Barlow produced for Turner.

The Master of the Rolls was receptive to the argument that a wood engraving in a magazine should not be considered a publication of the painting. Unlike a printed book, which Smith said could be considered the publication of the author’s manuscript, a wood engraving could not be considered the publication of the painting itself. In the present case, Smith found the difference all the more striking because the illustration in the magazine was uncolored.84 As he put it in the written judgment, ‘a painting and a wood engraving, as imperfect as that published in the National Magazine, have but little resemblance to each other’.85

As for the exhibitions, Turner’s counsel argued that they did not constitute publication because they were restricted: members of the public were allowed to view but not to copy the paintings. Counsel raised the analogy of a theater performance. Courts had held that the performance of a stage play did not terminate the author’s right to decide whether and when to sell printed copies of the play. Similarly, an exhibition of a painting did not terminate the artist’s right to restrict copying. According to Turner’s counsel, Robinson had committed fraud and breach of confidence, ‘for he availed himself of a privilege granted to him, to carry away surreptitiously in his mind the details of the picture’.86 On this point counsel cited not only Prince Albert v. Strange, but also Abernethy v. Hutchinson (1825), in which a student had transcribed a lecture by a surgeon, which was then published in the medical journal The Lancet. The court granted an injunction on the grounds of breach of trust or contract after it was shown that students were admitted to such lectures on the understanding that they could take notes solely for their own information.87 The point of similarity was that Robinson had been admitted to view the painting on the understanding that he was not to make and sell copies of it.

Robinson claimed that the exhibition at Cranfield’s was not subject to clear conditions and pointed out that the newspaper advertisements for the showing did not mention any engraving.88 However, Turner’s testimony and supporting affidavits showed that the goal of obtaining subscribers was widely known: 1,500 copies of a prospectus had been printed and distributed, and there was a subscription book in the room where the painting was on view.89 During a hearing Smith described such exhibitions as an established and well-known practice among print publishers. He cited Henry Nelson O’Neill’s Eastward Ho! (1857) as a recent example of a famous painting exhibited in Dublin to attract subscribers to an engraving. If counsel for Robinson were correct, Smith said, then anyone who saw Eastward Ho! on display might make and distribute copies for their own profit. On behalf of Robinson, Sullivan responded that ‘such pictures might stand upon a different ground from that of a painting at the Royal Academy’.90 His point seems to have been that even if the viewing at Cranfield’s would not have constituted a publication of Wallis’s painting, surely works exhibited at the Royal Academy could not be said to be ‘unpublished’.

Gallery Rules Related to Copying

Unfortunately for Robinson, Smith thought it was important to inquire into the rules governing copying at the Royal Academy. According to Smith, the existence of such regulations would destroy the argument that public exhibition of an artwork constituted dedication to the public. And since neither Turner nor Robinson presented evidence on this subject, Smith announced that before committing his judgment to writing he would make inquiries of the Royal Academy and the organizers of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition to determine what regulations were in place when Wallis’s painting was displayed.91 When he delivered his final judgment in January 1860, Smith presented the results of his research and took the opportunity to chastise the opposing parties. Smith suggested that his own reputation, and that of the Irish court system, was at stake:

In a case of so much public importance, the inquiries which the Court had been obliged to make should have been made instead of giving the Court the trouble of making them; but he did not wish it to be said in England that he had given a judgment without inquiring into the practice, which was well-known, indeed notorious, that permission was not given to copy pictures in the Royal Academy.92

Smith’s son happened to know the painter and arts administrator Richard Redgrave, who wrote to John Prescott Knight, Secretary of the Royal Academy, for policy details. Knight’s reply, which was quoted in court, referred to an 1847 resolution that read: ‘[A]s much property in copyright is annually entrusted to the guardianship of the Royal Academy, the Council is compelled to disallow all copying within the walls from pictures sent for exhibition’.93 Knight also cited a more recent resolution prohibiting copying during exhibitions, and gave the telling example of an artist who was refused permission to copy his own picture while it was on display. In addition, Knight confirmed that the Academy employed a guard to prevent anyone from copying surreptitiously. Smith obtained a further letter from Sir Charles Eastlake, President of the Royal Academy and director of the National Gallery. With respect to the Royal Academy, Eastlake confirmed Knight’s statements. As for the National Gallery, he reported, ‘there is no prohibition to copy pictures which are the property of the nation’.94 Interestingly, Eastlake was also the first president of the Photographic Society, founded in London in 1853, though the excerpts from his letter quoted by the Master of the Rolls do not allude to photographic reproductions at all.

As Eastlake and Redgrave both knew, the policies of public art galleries with respect to photography were varied and evolving at this time. What is not mentioned in any of the published reports of Turner v. Robinson is that at this very moment the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria & Albert Museum) was launching a new program that would make low-cost photographic reproductions of artworks in its collection available to the public. In an initiative that was approved by the Privy Council on Education, the museum’s own photography department produced these prints and sold them to the public at cost, a fact that vexed professional photographers who wanted to profit from demand for reproductions of artworks.95 Redgrave, as the Inspector General for Art in the government’s Department of Science and Art and the first Keeper of Paintings at the South Kensington Museum, was one of the initiators of this program. He would have been aware that his own institution’s policies with respect to photography differed from those of other museums, which at this point gave much less thought to photography.96 It is not known if the letters from Redgrave or Eastlake alluded to the work taking place at the South Kensington Museum, but even if they had Smith would have avoided the topic in his judgment. The court was interested in the practices of the Royal Academy with respect to the exhibition of paintings by living artists, not older works that Eastlake referred to confidently as the ‘property of the nation’. Any discussion of authorized photographic reproductions would have muddied the waters. For Smith, the letters from Eastlake and Knight confirmed that the exhibition of Wallis’s painting at the Royal Academy was ‘no publication, as it would have been a breach of trust and a breach of an implied contract to have allowed the painting to be copied’.97

With respect to the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, Smith obtained similar evidence, with Redgrave once again acting as intermediary. The president of the committee that organized the Manchester exhibition confirmed that copying had not been allowed. The secretary of the same exhibition admitted that the art dealers and print publishers Paul and Dominic Colnaghi had published a series of photographic reproductions featuring ‘gems’ of the Art Treasures Exhibition, but that they had obtained written permission from all of the owners whose paintings they photographed.98 Interestingly, one of the photographers that contributed to the Colnaghi project, Leonida Caldesi, actually produced a photograph of Wallis’s Chatterton during the Manchester exhibition, though this one was not published by the Colnaghis. The existence of this photograph was mentioned at trial; Turner explained that Caldesi had provided Egg with some copies of it for his personal use.99 A different photograph of Wallis’s painting had been taken by Charles Wright around the time of the Royal Academy exhibition in 1856. Wright actually exhibited this photograph at the February 1857 exhibition of the Photographic Society of London.100 This fact was apparently not mentioned at trial. Had Robinson known about the public exhibition of a photograph of Wallis’s Chatterton, he most likely would have tried to use the example to reinforce his argument that the painting had already been ‘published’ in multiple ways.

For the Master of the Rolls, all that mattered was that during the exhibitions of Wallis’s painting at the Royal Academy and the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition rules against copying were being enforced. Consequently, these exhibitions could not be considered publications of Wallis’s painting. On behalf of Robinson, Sullivan objected to the way Smith had solicited these letters and relied on them to support his ruling. The letters had not been properly entered as evidence or made available for examination by opposing counsel. After a heated exchange with Sullivan, Smith decided to order a Master (a judicial official) to make an independent investigation of the rules observed at the Royal Academy and at the Manchester exhibition. Smith said that Robinson could appeal, and suspected that he would, since ‘there is no species of litigation in which your client is not prepared to embark’.101 Sullivan objected to Smith’s language as prejudicial to his client and found his personal inquiry into gallery practices to be highly irregular. One newspaper reporter understood Sullivan to say, ‘no court of justice should take the conduct of any case into its own hands for the purpose of punishing a suitor’.102

What Constitutes an Illegal Copy?

Robinson appealed both the injunction and the order for the Master’s formal inquiry into gallery rules. The Court of Appeal determined that the inquiry was not necessary because the case could be decided on the basis of breach of confidence. Robinson did not deny having imitated the composition and details of Wallis’s painting. For the Lord Chancellor, it was clear that Robinson did not have the right to do this, and that he knew as much. Turner had published a warning to photographers and Robinson never denied having seen this warning. Robinson’s own advertisement, which responded to the allegation of piracy by insisting that he had photographed from a living model, also suggested to the court that Robinson knew that copying the painting was forbidden.103 The Lord Justice of Appeal also found that Robinson had acted surreptitiously and was in breach of confidence. He cited the fact that Robinson had not copied the painting in Cranfield’s Gallery, but reproduced the scene in his own studio, as further proof that he knew that he was not allowed to copy it.104

It will be recalled that Robinson denied having copied the painting at all. His goal was not to produce a single-image photograph but a stereoscopic view. Since the photographs that appeared on his stereo cards were taken from a live model and props in his studio, he did not see how they could be considered copies of the painting. His counsel added that the resulting stereo cards could not be said to harm the sale of the engraving because they were produced in a different manner and for a different purpose.105

That argument echoed the judge’s decision in the case of Martin v. Wright (1833), which is fully discussed in Simon Stern’s chapter in this volume.106 Briefly, the court held that the public exhibition of a diorama reproducing the design of the well-known painting and print of Belshezzar’s Feast by John Martin did not constitute infringement because ‘exhibiting for profit is in no way analogous to selling a copy of the Plaintiff’s print, but is dealing with it in a very different manner’.107 In other words, charging admission to view a representation of Martin’s design was not the same as selling copies of the print. But counsel for Turner insisted that in the present case Robinson’s stereo cards were in fact copies of Wallis’s painting, and that these copies would necessarily harm the sale of Turner’s projected engraving.

Martin v. Wright was decided on the basis of statutory copyright, whereas in the Irish Rolls Court Turner v. Robinson was being discussed in terms of common law protection for unpublished works. The scope of protection (what constituted infringement) was understood to be different in these two areas of law. Statutory copyright developed a number of exceptions that made it somewhat more flexible than common law protection for unpublished works, which was generally held to be quite broad.108 In this context it is not surprising that counsel for Turner made the following argument: ‘if persons could pirate the idea of a painting, and publish it as they pleased, the rights of engravers would be very seriously invaded’.109 Robinson objected to such a broad right in the ‘idea of a painting’. He claimed that his stereo cards, though indeed based on the idea of Wallis’s painting, were not copies of the painting itself.

In the Rolls Court, Smith found the fact that Robinson had copied to be obvious, though he insisted that it was highly unlikely that Robinson had worked from memory alone. In newspaper reports of the hearings, Smith is quoted saying that he thought Robinson must have worked from the engraving in the National Magazine; how else would he have been able to reconstruct even minor details? His choice of colors, however, indicated to the judge that Robinson had also benefited from his access to the painting at Cranfield’s Gallery.110 Wallis’s color choices were indeed distinctive — note the red hair, violet breeches, and red coat in Figure 1 — and like other artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite style, Wallis painted on a white ground, which heightened the vibrancy of the colors. Although Robinson’s hand-colored stereo cards (Figure 2) could not possibly reproduce the vividness of the original, the fact that he used similar colors clearly worked against him in court. Smith acknowledged that it was reasonable to doubt whether Robinson’s stereo cards would represent ‘a serious injury to the owner of this valuable painting’, but he insisted that photographic reproductions posed a clear threat, evoking a sort of slippery slope that had to be avoided: ‘The photograph might by a very easy process be enlarged to the size of the original, and thus an unimportant piracy might be followed up by the adoption of another mode of piracy which would be most injurious to the owner of the painting’.111 It will be noticed that the judge consistently referred to the rights of the owner of the painting (in this case Egg, and by extension Turner as ‘bailee’) rather than to the artist himself.

The Court of Appeal was similarly unreceptive to the idea that Robinson’s stereographs should not be considered copies of the painting. The Lord Justice of Appeal stated that Robinson’s stereograph ‘does not, in my opinion, lose the character of a copy because it has been effected, not in the usual mode, but by an exercise of memory, and by ingenious scientific operations, which, by rendering the likeness more accurate, must or may diminish the demand for engravings, which constitutes so large a proportion of [the painting’s] value’.112 The fact that Robinson did not take the photographs directly from the painting but from a living model and props in his studio did not mean that they were not copies. On the contrary, the Lord Justice of the Appeal stated, ‘it is through this medium [i.e. the restaging of the painting as a tableau] that the photograph has been made a perfect representation of the painting’.113 Thus the Court of Appeal held that Robinson’s stereographs were copies of the painting, and that it was illegal for him to make these copies regardless of the process or medium involved.

The surviving record of proceedings suggests that there was no discussion of the contemporary cultural practice of creating tableaux vivants, or of whether it would have been lawful to restage Wallis’s painting as a ‘living picture’ if no photographic prints had been offered for sale. Did the tableau in his studio already constitute an illegal copy of the painting, or would it have been too ephemeral to rise to the level of infringement? The fact that Robinson had produced photographic prints that closely resembled the painting may have made such a question moot. But British courts did face this question in the 1890s, when major commercial theaters popularized the staging of ‘living pictures’ for large paying audiences. The owners of some of the paintings being imitated on stage sued for copyright infringement under the 1862 act. In one case that went all the way to the House of Lords, it was held that a tableau vivant performed as part of a stage play and newspaper illustrations of the same tableau did not infringe the copyright in the painting itself. The Lord Chancellor acknowledged that an infringing copy could be made from an intermediate work such as a tableau vivant, but in the case at hand he found that the newspaper illustrations were not sufficiently similar to the painting. As for the ‘living picture’ itself, it had already been decided at first instance and affirmed by the Court of Appeal that the live staging of the painting was not infringing because it was only temporary and did not result in any material ‘copy’ that could be forfeited under the 1862 act. In other words, a painting could be infringed by a drawing, photograph, or another painting, but not by the tableau vivant itself.114 The facts in Robinson v. Turner were different because the defendant had imitated Wallis’s painting so closely, and because he was offering physical copies for sale.

Legal Significance v. Commercial and Cultural Effects

What is the significance of Turner v. Robinson for the history of artistic copyright? As Elena Cooper has explained, the Master of the Rolls offered an expansive interpretation of common law protection for paintings. The scope of this right was held to be quite broad, since the process by which Robinson made his reproductions did not matter to the courts, nor did the fact that stereoscopic views were different media than mezzotint engravings. When copyright protection was extended to paintings in 1862, the statute prohibited unauthorized copies of the painting ‘and the design thereof’ produced ‘by any means and of any size’.115 In some ways, Smith’s judgment anticipated this broad ownership right, though of course he decided the case based on the common law rather than the copyright statute. The common law protection for paintings that Smith recognized was quite durable, since it could not be terminated by the publication of an engraving or by the exhibition of the painting in cases where the display was for a specific purpose (such as to attract subscribers) or subject to restrictions against copying (as at the Royal Academy). Theoretically, this common law protection in paintings could subsist alongside the protection offered by the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862. Because the statute protected artworks from the moment of creation rather than ‘publication’ (as had long been the case with literary works), as long as an artwork was deemed ‘unpublished’, it could be protected by both common law and statutory copyright.116 And yet, according to Cooper, the decision in Turner v. Robinson was not looked to by artists or collectors, in part because its principles were not subsequently endorsed by a higher court, and in part because of uncertainty about who would own the common law copyright. The case law with respect to unpublished writings had clearly established that the author of a letter retained the common law copyright. The recipient owned the physical letter, but did not have the right to publish it without the author’s consent. By contrast, Smith held — despite the hesitations he voiced in court — that the common law copyright passed automatically to the purchaser of a painting. Artists did not generally like this principle.117

On the question of whether public exhibition of an artwork divested an artist of their rights, Turner v. Robinson was cited in the United States as well as in the United Kingdom.118 From the perspective of print publishers like Turner, such a ruling had become urgent because of the increased frequency and scale of public exhibitions. In the case of works by well-known artists, it was rarely practical to wait for an engraving to be finished before displaying the work, and photographic reproductions seemed much more threatening than rival engravings. Engravings like Barlow’s took a significant amount of time and resources to produce, and major print publishes protected their investments further by making formal or informal agreements not to compete directly on a particular subject or in a given territory.119 Photography was disruptive not only because it could be used to facilitate the engraving process — significantly reducing the amount of time an engraver needed access to the physical painting — but also because photographic reproductions could compete directly with engravings, as Turner claimed Robinson’s stereographs would do. Unauthorized photographic reproductions of the engraving itself constituted another threat, and these were the subject of significant litigation in the 1860s, when major print publishers, especially Ernest Gambart and Henry Graves, turned to the courts to protect their prints against piracy by photographers.120

Cooper has suggested that one practical consequence of Turner v. Robinson is that explicit rules prohibiting copying of works by living artists became more common in major galleries in the British Isles.121 But did the decision alter the practices of photographers, particularly those inclined to stage scenes from famous paintings? Pellerin and May have shown that stereoscopic photographs of tableaux vivants constituted an important but hitherto neglected genre in Victorian photography, and this genre continued to flourish after Turner v. Robinson and the adoption of the Fine Arts Copyright Act in 1862. So far, no subsequent lawsuit against a photographer for restaging a painting as a tableau vivant has been found.122 One explanation for this might be that Robinson’s Death of Chatterton was a rather extreme example: he imitated Wallis’s painting very closely, whereas most photographers who restaged scenes from paintings introduced variations of one sort or another.123

In his study of the symbiotic relationship between Pre-Raphaelite painting and photography, Michael Bartram remarked that the result of Robinson’s attention to detail was ‘at once bizarre and tawdry, though doubtless photography had been encouraged to turn in this direction by the obsessive literalism of painting at this time. Painting and photography could go no further than this in their exchange of identities’.124 But as Martin Meisel has explained in his study of the complex relationship between painting and theater during this period, for contemporary audiences much of the appeal of tableaux vivants depended upon the spectator being able to recognize a specific painting and judge how closely its details had been recreated.125 The same could be said for Robinson’s remediation of Wallis’s painting.

In any case, Robinson’s The Death of Chatterton clearly inspired other photographers to treat the same subject following the same method. The Birmingham photographer Michael Burr produced at least two versions of a stereograph of the same scene (see Figures 8 and 9). Although it seems likely that Burr got the idea from Robinson’s stereographs — or perhaps from newspaper accounts of Turner v. Robinson? — he did not necessarily work directly from Robinson’s cards to recreate the scene. Wallis’s painting was exhibited in Birmingham in the spring of 1860 (again as part of Turner’s campaign to advertise Barlow’s engraving), and Burr may have seen the canvas at that time.126 Burr does not seem to have been sued (at least no record of a case has been found), but according to Pellerin one of his stereographs was in turn pirated by an unknown photographer.127 In addition to these stereographs, a carte-de-visite version of The Death of Chatterton was produced by an unknown photographer in the early 1860s (see Figure 10). The text on the bottom of the card is from a biography of Chatterton published in 1810, but that text was almost certainly copied directly from the back of Robinson’s stereo card, which contains a longer extract from the same biography (see Figure 2).128 We thus know of at least four unauthorized versions of The Death of Chatterton that seem to have been directly inspired by Robinson’s, though it is quite possible that there were additional versions that have not survived.

Fig. 8 Michael Burr, The Death of Chatterton, ca. 1860, Collection of Dr. Brian May, reproduced with kind permission.

Fig. 9 A second version of The Death of Chatterton by Michael Burr, ca. 1860, Collection of Dr. Brian May, reproduced with kind permission.

Fig. 10 An anonymous and undated carte de visite that closely resembles the Burr photograph in Figure 9, but which uses part of the text printed on the back of Robinson’s card (Figure 2). Collection of Anthony Hamber, CC BY.

The extent to which Wallis’s painting shaped subsequent representations of Chatterton could be the subject of a fascinating study of its own. Only a couple of examples can be mentioned here. In the mid-1880s, the actor Wilson Barrett portrayed Chatterton in a popular one-act play. A series of cabinet-sized photographs of Barrett in this role include one that closely imitates Wallis’s painting (see Figure 11). The photographer, Herbert Rose Barraud, was not the one who had the idea to restage Wallis’s painting, since that was part of the mise-en-scène of the one-act play. But Barraud was unknowingly following in Robinson’s footsteps. And though Robinson has been largely forgotten today, recreations of Wallis’s painting in the form of photographs from tableaux vivants continue to be produced. In 2011, the British Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare restaged the painting, but substituted the likeness of Admiral Lord Nelson for that of Chatterton.129 And it will perhaps come as little surprise that among the countless photographs of tableaux vivants based on classic paintings that circulated on social media during the Covid-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020 (often using the hashtag #GettyChallenge), there were some personalized recreations of Wallis’s Chatterton.130

Fig. 11 Herbert Rose Barraud, photograph of Wilson Barrett as Chatterton at the Princess’s Theater, 1884, Guy Little Theatrical Photograph Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O227561/guy-little-theatrical-photograph-photograph-barraud-herbert-rose/.

Conclusion

What explains the fact that Burr and other photographers who restaged paintings were not sued by copyright owners? Should the case against Robinson be seen as an outlier? Insofar as there are many factors explaining why an individual such as Turner would decide to pursue litigation, it may not be possible to provide definitive answers to these questions, but I will offer what I think is a plausible explanation based on the legal and commercial contexts. Turner sued in 1859 because Robinson’s actions were provocative and because he wanted to take a stand on behalf of print publishers against photographers at a moment when there was no statutory copyright for paintings. After the Fine Arts Copyright Act was adopted in 1862, print publishers continued to worry about photography, but most of their attention turned to the problem of photographs taken directly from engravings, rather than the more complex case of photographs of tableaux vivants based on paintings.131 It could be that within a few years the extent to which stereoscopic views actually harmed the sale of quality engravings was understood to be less than what Turner and others feared in the late 1850s. The actions of both Robinson and Turner made sense given the legal, cultural, and economic contexts. But the fact that stereoscopic views based on tableaux vivants of famous paintings continued to be produced after 1860 should caution us against assuming that Turner v. Robinson had any direct effect on artistic and commercial practices.

Though decided on the grounds of common law property rights and breach of confidence rather than on the grounds of statutory copyright, the decisions in the Rolls Court and in the Court of Appeal reflected a fairly widespread perception that the lack of statutory protection for paintings represented a gap in the law. Indeed, in the course of his opinion, Smith cited speeches and legal opinions that he thought could be employed effectively to lobby for statutory copyright in paintings.132 The rulings of the Rolls Court and the Court of Appeal also pointed toward a more expansive view of what constituted an infringing ‘copy’. Both courts found that Robinson’s stereo cards were illegal ‘copies’ of Wallis’s painting, regardless of the process he used, let alone the very different viewing experience enabled by stereography. Robinson did not have the right to reproduce the ‘design’ or the ‘idea’ of Wallis’s painting. The fact that the copying was indirect and transposed the subject of Chatterton into a new medium was deemed irrelevant by the courts. In that sense, Turner v. Robinson confirmed an ongoing expansion in the scope of property rights in visual works.

Bibliography

Bajac, Quentin, Tableaux vivants: Fantaisies photographiques victoriennes (1840–1880) (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1999).

Bartram, Michael, The Pre-Raphaelite Camera: Aspects of Victorian Photography (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1985).

Bently, Lionel, ‘Art and the Making of Modern Copyright Law’, in Dear Images: Art, Copyright, and Culture, ed. by Daniel McClean and Karsten Schubert (London: Ridinghouse/ICA, 2002), pp. 331–351.

——, ‘Prince Albert v. Strange (1849)’, in Landmark Cases in Equity, ed. by Charles Mitchell and Paul Mitchell (London: Hart Publishing, 2012), pp. 235–268, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474200790.ch-008.

Bently, Lionel, and Martin Kretschmer, eds., Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), http://www.copyrighthistory.org.

Blaine, D. Roberton, On the Laws of Artistic Copyright and their Defects (London: John Murray, 1853).

Chalmers, Alexander, ‘Life of Chatterton’, in Alexander Chalmers, The Works of the English Poets, from Chaucer to Cowper. 21 vols. (London: J. Johnson and others, 1810), vol. 15: 375.

Claudet, Laura, ‘Stereoscopy’, in Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, ed. by John Hannavy. 2 vols. (New York and London: Routledge, 2008), vol. 2: 1338–1341, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203941782.

Clayton, Zoe, ‘Stereographs’, V&A Blog, 29 January 2013, https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/caring-for-our-collections/stereographs.

Cooper, Elena, Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316840993.

——, ‘How Art was Different: Researching the History of Artistic Copyright’, in Research Handbook on the History of Copyright Law, ed. by Isabella Alexander and H. Tomás Gómez-Arostegui (Cheltenham, UK: Elgar, 2016), pp. 158–173, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783472406.00015.

Deazley, Ronan, ‘Commentary on Fine Arts Copyright Act 1862’(2008), in Primary Sources on Copyright, ed. by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer, http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord?id=commentary_uk_1862.

——, ‘Commentary on Publication of Lectures Act 1835’ (2008), in Primary Sources on Copyright, ed. by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer, http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord?id=commentary_uk_1835.