6. Before an Image Was Worth a Thousand Words: Ben-Hur and Copyright’s Right of Derivatives

© 2021 Oren Bracha, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0247.06

In 1834 Justice Joseph Story wrote that in the law of copyright one could get the closest to ‘the metaphysics of the law’.1 Nowhere was this observation truer than with respect to the rules pertaining to the scope of copyright and its infringement. The puzzles strewn across this area of the law went to the core of the modern concept of intellectual property. What does it mean to own an intellectual work of authorship? What are the metes and bounds of this peculiar object of property? And how can one tell when these were transgressed in the absence of ‘natural’ physical boundaries? The metaphysics involved, however, were of a peculiar kind. Deep theoretical questions about the nature of expressive works of the intellect — and the meaning of ownership of such works — were closely intertwined with the nitty-gritty aspects of commercial practices, and with the ideology of the market embedded in them.

Half a century after Story made his observation, the world of commerce in which intellectual works were immersed transformed considerably, and so did the ‘metaphysics’ of copyright. The last quarter of the nineteenth century saw the appearance of what soon became the entertainment industry: new expressive technologies with vast commercial potential, new business models for organizing the production and exploitation of creative works (both traditional and in new formats), and the perfection of techniques for creating and capturing markets for such works. As part of this process, creative works were increasingly commodified. The creation of expressive works came to be supported chiefly by commercial market exchange, existing markets grew dramatically, and new markets for new media opened up. Most importantly, however: each work gradually came to represent multiple streams of value in multiple markets. A novel was no longer merely a prospect for commercial success in the book market. A commercially successful novel represented potential profits in the secondary markets of translations, serializations, abridgments and, soon enough, dramatizations, pictorial-representations, and motion pictures. This was reflected in the logic of property rights in creative works known as ‘copyright’: if a work, as a commodity, represented multiple sources of exchange value from many markets, the property right had to be extended to enable exchange in these markets and capture their value. Market practices and the ideology of copyrighted ‘works’ as commodities were mutually constitutive. Commercial pushes to capture new markets led to novel assertions about the scope and nature of the property right as extending to all secondary markets. At the same time, an expanding understanding of the object of property legitimized and naturalized ventures to control new markets. At the heart of this ideology was a new and peculiar concept of the intellectual work that was wrapped in a powerfully circular logic: the intellectual work extends to all the concrete forms it might take in any potential market, and all secondary markets are ones for the work itself, owing to its enduring intellectual essence in the face of changing form.

Caught in this process of ideological transformation was the relationship between text and image. The traditional domain of copyright was text, although some recognition of images as a possible object of proprietary control existed even during the early origins of copyright. By the late nineteenth century, visual subject matter in various forms was already officially recognized as falling within the domain of copyright. The transition from text to image, however, was a different matter. Text and image were generally seen as distinct domains. To claim that a visual representation was a copy of a text and therefore interfered with its ownership was to brush copyright against the grain. Yet in a climate of growing commodification of works, visual ‘translations’ represented another market to be brought within the fold of copyright, and therefore a new territory to be conquered by the malleable coverage of the ‘work’. Pressure to reconceive the relationship between text and image and extend the property right in texts into the domain of images was sure to come.

The novel Ben-Hur by Lew Wallace was the perfect site for this process to unfold. Published in 1880, Ben-Hur created an unprecedented cultural and economic phenomenon. Moreover, it arrived at a precise transitionary moment: one in which publishers were newly poised to squeeze every drop of value from this new caliber of a bestseller, and when the boundaries of copyright were being pushed to encompass new markets. One legal case, Wallace v. Riley, acted as a lightning rod that captured these forces at work.2 The lawsuit at issue was brought by Wallace and his publishers against the Riley Brothers for creating and selling a set of magic-lantern slides based on the novel Ben-Hur. It was not a ‘great case’ in its time and it has been mostly forgotten since. It is, however, an invaluable specimen for studying the changing ideology of copyright. The case is the equivalent of the geologist’s stratigraphic column, juxtaposing the different strata of copyright and conveying a clear image of the process of change. It represents a moment in which two conceptions of the relationship between text and image coexisted in copyright. The traditional text-bound and domain-specific conception was already in decline, but the modern logic that extends copyright to all ‘derivative’ forms and markets did not yet naturalize the transition from text to image.

Exploring this forgotten case allows a glimpse at how the ‘metaphysical’ assumptions of copyright arose from below through human agency. In Wallace v. Riley publishers, creators and jurists all took part in a conversation about the nature of creative works and the relationship between text and image. Even as they were making technical legal claims, they were also articulating arguments and making assumptions about the underlying fundamental questions, all in the service of their interests as they understood them against the background of changing market practices and ideology. As they were doing so, they were shaping the modern copyright ideology of the ‘work’ as a commodity, within which the bridge of market exchange value spans the chasm between text and image.

All the Profits of Publication Which the Book Can, in Any Form, Produce

By 1880 copyright had traveled a long way. Originating more than three centuries earlier in the trade privileges of publishers, this area of the law retained much of the features of the book trade’s unique regulation even after statutes creating general regimes of authors’ rights were enacted in 1710 in Britain and in 1790 in the US.3 Two of these features were a print-bound understanding of the domain of copyright and a narrow concept of its scope centered on the paradigm of literal reproduction of printed text.

Emerging from the regulation of the printing press, early copyright was not seen as based on an abstract principle of authorship, nor as extending to every form of creative expression. While some early printing privileges were given for pictorial prints, the traditional domain of copyright had been that of printed texts, known as ‘books’.4 Adding pictorial subject matter to the sweep of copyright followed, more or less, on the heels of general statutory regimes with the 1735 British Engravers’ Act and the US inclusion of prints in 1802.5 These extensions, while pushing the boundaries of copyright beyond texts and the book trade, did not venture far from the traditional universe of print. As late as 1884, one old-fashioned definition of copyright still referred to it as limited to the ‘arts of printing in any of its branches’.6 By this time, however, a series of incremental extensions applied copyright to a variety of subject matters, including dramatic compositions, photographs, paintings, drawings, sculptures, and more.7 This did not yet entail a crisp and fully developed understanding of the field as based on an overarching principle of property in expressive works of authorship. Copyright now applied to multiple media, but these were generally seen as distinct domains, each loosely connected and governed by similar sets of internal rules. There was copyright in books and copyright in paintings, but it was unclear that the two ever crossed paths.

This fragmentation was apparent in the rules that governed intermedia copying. Here too copyright as the publisher’s privilege historically started with a narrow concept of the right’s scope. To own a ‘copy’ literally meant a ‘copy-right’, meaning an exclusive right to reproduce in print nearly identical as well as ‘colorable’ or ‘evasive’ versions of a protected text.8 An upshot of this understanding was a generally permissive approach toward various secondary uses of copyrighted works even within the textual realm, such as abridgments or translations.9 That copyright in texts could go beyond textual reproduction was at first hardly contemplated. There was a steadily growing push against these assumptions and in favor of increasing copyright’s scope, going at least as far back as the eighteenth century.10 By the second half of the nineteenth century, with increased commodification of texts and a gradually rising consciousness of ownership to match it, copyright’s scope was in a state of flux in the US.

There was still a strong foothold to the traditional narrow understanding of copyright’s ambit, the epitome of which was Stowe v. Thomas.11 Often considered to be the first bestseller, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was prone to attract attempts to develop new markets and control them through copyright, which is precisely what happened when Stowe’s and her publisher John P. Jewett’s plans for a German translation were disrupted by an unauthorized version that was published by F. W. Thomas.12 In the ensuing litigation Stowe expressed a broad understanding of copyright ownership, asserting that she ‘ever had, and still hath the sole and exclusive right, to translate, print, publish and sell the same, for her own private benefit and advantage’ and that she will be ‘greatly injured and damnified in respect of and deprived of the receipt of large profits which she reasonably expects to receive from the sale’ of the authorized translation.13 The sentiment also found considerable support in the press with one report asserting the following: ‘As for the absolute moral right, we see nothing in the nature of things to limit the ownership of the author. It is his work, and it ought to be for him to say on what terms others shall enjoy it, in whatsoever time, place, or tongue’.14 Thomas’s defense, in turn, was that ‘[i]n no parlance-either ordinary or legal-does “copy” mean “translation”’ and that ‘the prohibition is only against printing, publishing or importing “any copy of such book”’.15 Justice Robert Grier of the US Supreme Court sided with the defendant and with the traditional, narrow understanding of copyright’s scope. ‘[T]he only property’ conferred by copyright, he wrote, ‘is the exclusive right to multiply the copies of that particular combination of characters which exhibits to the eyes of another the ideas intended to be conveyed. This is what the law terms copy, or copyright’. It followed that a ‘copy’ of a book must be ‘a transcript of the language in which the conceptions of the author are clothed; of something printed and embodied in a tangible shape’, something which a translation clearly was not.16

The old orthodoxy of ‘copy-right’ embodied in Stowe v. Thomas was clearly beleaguered by the time the case was decided in 1853. Commentators directed a hail of criticism at the decision.17 In 1870 Congress overturned its rule by amending the statute to include rights of dramatization and translation.18 The parallel rule favoring abridgments of copyrighted works was accepted only begrudgingly in American case law, and while never formally rejected, it was well on its way to dissolving.19 An important landmark was the 1856 creation of a public performance right in dramatic works.20 Playwrights, motivated by the changing economic organization of American theater and a developing self-consciousness as an authorial class, had been lobbying for such a right for decades.21 The conceptual significance of the new right was in extending the scope of copyright into the sphere of intermedia reproduction. Plays could traditionally be protected as texts, but with the newly minted public performance right, their copyright could be infringed by a form of non-textual use. In the context of dramatic works, courts, that were faced with the challenge of conceptualizing drama as a form of non-textual expression, began to apply copyright in the interface between text and this different expressive form on a routine basis.22 Music, whose traditional copyright protection was similarly limited to reprinting, would undergo a similar process, with the statutory creation of a public performance right only in 1897.23

By 1880 the traditional understanding of the legal field as ‘copy-right’ was under significant pressure. Doctrinal and conceptual incursions had been made, but no general principle extending copyright to intermedia reproduction had appeared. Specifically, images and texts remained distinct. The early treatise writers, however, were busily erecting the intellectual infrastructure that would support such a principle and eventually bring down the barrier dividing image and text. There were three foundations to this new conceptual structure: a market-oriented understanding of the right, a matching concept of the expressive work as an intellectual essence that transcends varying forms, and a sharp distinction between an original creation and derivatives. George Ticknor Curtis launched the attack on the rules that limited copyright to close textual reproductions and shielded secondary uses in his mid-century treatise. Curtis’ starting point was defining the authorial entitlement over a work in terms of market profits from all its possible forms: ‘to the author belongs the exclusive right to take all the profits of publication which the book can, in any form, produce’.24 The author’s copyright, he argued, ‘must be held to have secured to him the right to avail himself of the profits to be reaped from all classes of readers’.25 An abridgment, for example, is ‘a valuable part of the copyright’, and ‘[i]f, during the existence of the copyright, the work is abridged by a stranger, the copyright is shorn of an incident, the loss of which may greatly affect its value as property’.26 The assumption that copyright covers all ‘incidents’ of profits led to a rejection of the ‘copy’ and its replacement with a broader and elusive object of property. Thus, with respect to translations:

The property of the original author embraces something more than the words in which his sentiments are conveyed… In such cases his right may be invaded, in whatever form his own property may be reproduced. The new language in which his composition is clothed by translation affords only a different medium of communicating that in which he has an exclusive property.27

In his influential 1879 treatise, Eaton Drone perfected this vision of copyright’s object of property that tied together profits from multiple markets and a manifold of forms. Drone insisted that ‘It is no defence of piracy that the work entitled to protection has not been copied literally; that it has been translated into another language; that it has been dramatized; that the whole has not been taken; that it has been abridged; that it is reproduced in a new and more useful form’. Rather, ‘[t]he controlling question always is, whether the substance of the work is taken without authority’.28 The ‘substance of the work’ became the linchpin solidifying the control of the owner over all secondary markets for his work. Moreover, the principle of controlling all secondary markets replaced the old concept of the ‘copy’ with that of ‘the substance of the work’ as an intellectual essence that persists notwithstanding changes of form. Secondary markets constituted the metaphysics of the ‘work’, and the ‘work’ defined these markets as ones to whose value the author was entitled. ‘The definition that a copy is a literal transcript of the language of the original finds no place in the jurisprudence with which we are concerned’, wrote Drone. ‘Literary property’, he argued,

is not in the language alone; but in the matter of which language is merely a means of communication. It is in the substance and not in the form alone. That which constitutes the essence and value of literary composition… may be capable of expression in more than one form of language different than the original.29

The logic of reducing all secondary works to mere forms manifesting the same substance — and of subjecting all secondary markets to the property right in the work — also entailed a sharp hierarchy between original and derivative. While earlier views often emphasized the value and merit of secondary works, Drone asserted with confidence that ‘the translator creates nothing’ but rather ‘takes the entire creation of another, and simply clothes it in new dress’.30 Similarly, he stated that

the dramatist invents nothing, creates nothing. He simply arranges the parts, or changes the from, of what which already exists… in making this use of a work of which he is not the author, he avails himself of the fruits of genius and industry which are not his own, and takes to himself profits which belong to another.31

This was a fully developed version of the modern logic of ‘derivative’ works: an original intellectual work is a polymorphic intellectual essence that extends to all secondary creation based on it, no matter how different in form; such secondary creation is merely derivative; from which it naturally follows that the author of the original is entitled to all profits generated by such derivative markets. All of this was an ideological reflection in consciousness of changing market realities. As expressive works were increasingly commodified and right owners sought to squeeze out each drop of market value in every available secondary market, the legal arguments and the metaphysics of the ‘work’ to support and legitimize extending the reach of property into such markets were accordingly developed. In Drone’s version, the main examples of secondary works and markets were still largely text-oriented: translations, abridgments, and (beginning to reach beyond text) dramatizations. With market players ever on the look for new sources of value and image-oriented uses promising exploitable markets, it was only a matter of time before the emerging logic of derivative works would be extended to challenge the division between text and image.

Ben-Hur: My God, Did I Set All of This in Motion?

A recent comprehensive study described ‘the Ben-Hur property’ as ‘an avatar of American popular, artistic commercialism’.32 The foundation of what became a cultural and commercial empire was the immensely successful novel. Despite a slow start and a cold reception by literary critics, Ben-Hur’s sales gradually picked up, eventually making it an unprecedented bestseller.33 There were many reasons related to the content of the novel that account for its vast success. The story had all the right ingredients to appeal to the sensibilities of the era: an epic tale of a Jewish nobleman, betrayed by his friend and enslaved by the Romans, his adventure-packed quest for revenge turned into religious redemption, all intersecting with the life and death of Christ. Literary and cultural historians have explored the many ways in which these elements touched the right nerves at the right time: offering a way of embracing modernity without rejecting religion through the personification of Christ; telling a Gilded-Age-apt story of rags to riches achieved through piety and virtue; offering the thrill of action and vengeance combined with the elation of spiritual redemption, and even, as some speculate, helping to reunite the nation in the post-Reconstruction years.34 Whatever the reasons for its sweeping cultural success, when it came to the world of commerce Ben-Hur created a new phenomenon. It was much more than a popular novel sold in many copies. In the two decades following its publication it grew to be a powerhouse, feeding an elaborate network that connected artistic creation, popular culture, and commerce. In this respect Ben-Hur was different from bestsellers that preceded it, and was a harbinger of the modern business franchise: one that builds a comprehensive structure of economic exploitation around a successful expressive commodity through complex commercial and legal arrangements in numerous markets.

Following the success of the novel, its publishers, Harper Brothers — in cooperation with Lew Wallace and later his son Henry Wallace — worked to cultivate and exploit demand in various book submarkets. In doing so they employed and perfected techniques that had been developed by book publishers since the mid-nineteenth-century. Harper commissioned a prequel to the book (The Boyhood of Christ), released an extended and illustrated version for the gift book market in 1889, published or licensed a variety of excerpted shorter versions such as The First Christmas and The Chariot Race, and licensed a short Christmas gift-book called Seekers After ‘The Light’.35 A special two-volume, extravagant and expansive Garfield edition was issued following the assassination of President Garfield.36 There was also a Wallace Memorial Edition published after his death. In 1913, in a deal of an unprecedented scale, the mail-order giant Sears, Roebuck & Co. bought the rights to reprint, and sell in an affordable format, one million copies of this edition: a sales operation that it supported with a massive advertisement campaign.37

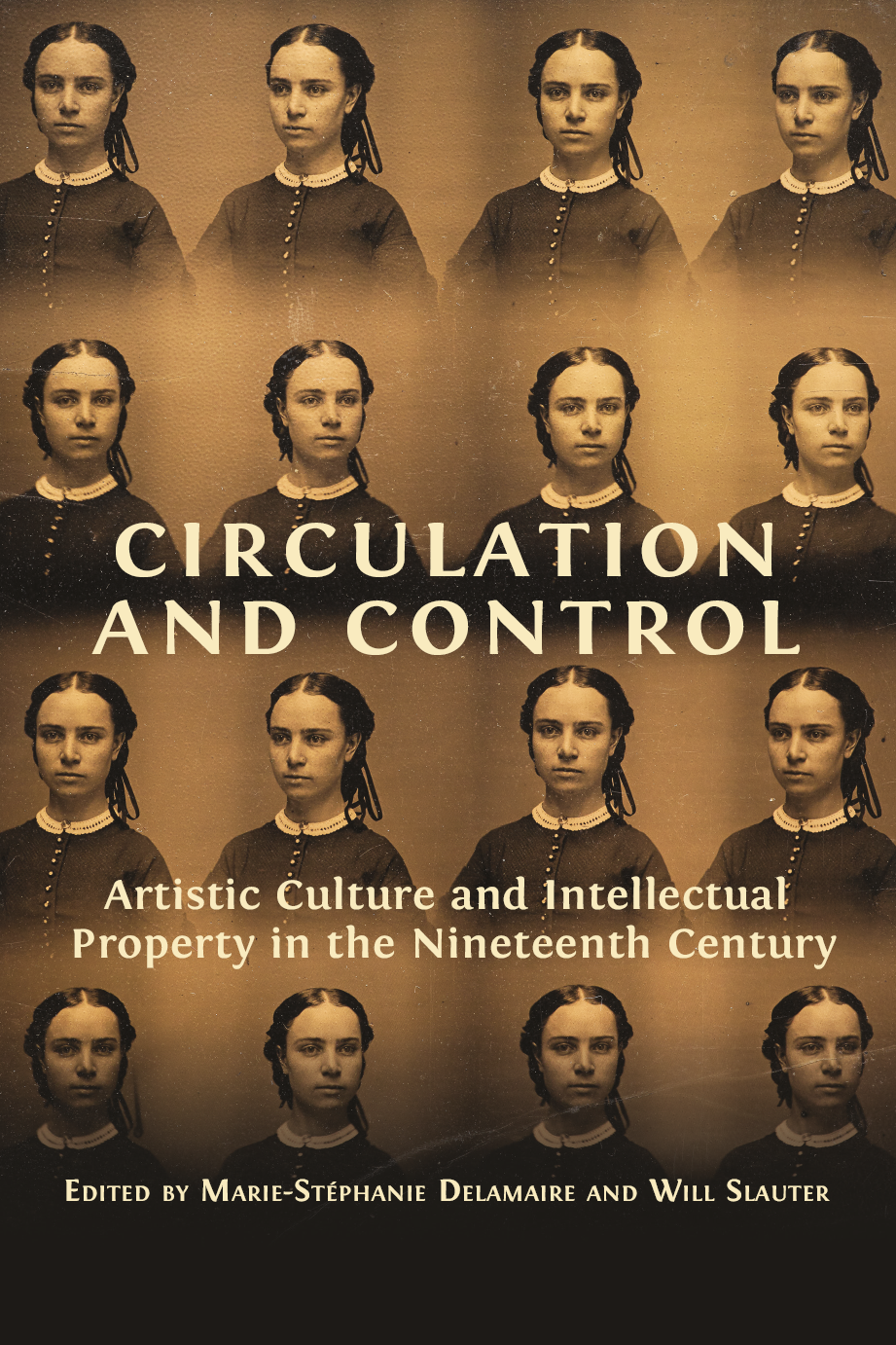

The commercial and cultural power of Ben-Hur emanated, however, well beyond print markets. By the early decades of the twentieth century the novel’s name and imagery could be found in many corners of the interface between American popular culture and commerce. There were Ben-Hur spices, coffee, flour, cigars, oranges, bicycles, and many more products.38 Ben-Hur elements appeared in a plethora of advertisements for anything from cars to fences. Chapters of Ben-Hur fraternal organizations appeared.39 One of them — The Tribe of Ben-Hur — had an insurance scheme for members and eventually became an insurance company.40 There were chariot races Ben-Hur style, river boats named Ben-Hur, and even various towns bearing the name (see Figure 1).41 With American trademark law in its infancy and no broad concept of brand ownership as means for allowing brand owners to fully commodify their commercial insignia, most of these activities were beyond the legal reach of Wallace and his publishers. With the exception of some arrangements for cooperation and endorsement, the brand value of Ben-Hur was thus mostly free for all to exploit with little ability by its originator to capture its vast commercial value.

Fig. 1 Ben-Hur Flour, advertisement by unknown creator (item held by the author).

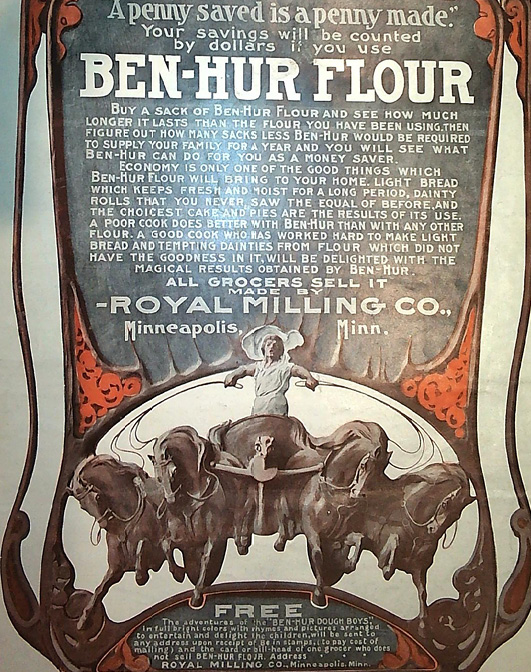

In between the book market and the, still largely un-commodified, brand market, there was a wide variety of expressive activities that drew on Ben-Hur’s repository of expressions and meanings. Many of those started as spontaneous cultural activities that were neither coordinated nor controlled by the owner of Ben-Hur. Some were quasi or fully commercial. And many would eventually become of interest to Wallace’s publishers and licensees, who tried to monetize them as sources of market value or protect adjacent markets they exploited. Beginning in the late 1880s, public recitations and live readings of the novel were becoming a widespread phenomenon. These appeared in many formats and ranged over a spectrum of social, charitable, and commercial events, as well as everything in between. One instance out of countless similar reading events demonstrates both that Ben-Hur’s copyright owner was aware of the phenomenon and that it began to elicit thoughts of proprietary control. In 1894, Virginia Saffel Mercer from Salem, Ohio launched a show named ‘The Healing of The Lepers’ (see Figure 2). It was advertised as ‘An Entire Evening from Ben Hur’ and offered to ‘Church and College Societies, Lecture Committees and Cemetery Associations’.42 In a December 1896 letter to Wallace, Mercer described her show as embracing ‘the quieter scenes’ (hence no chariot race) and remarked that ‘For obvious reasons, the impersonation of the lepers is not close’. She then informed Wallace that she ‘should be pleased’ to present her act to him ‘for charitable purposes or even in your private study’ and asked for his endorsement.43 Wallace, perhaps moved by Mercer’s report that she was about ‘to secure an agent and make a tour of the cities in this and surrounding states’, promptly forwarded the letter to Harper, alerting the publisher to a possible infringement of the novel’s copyright.44

Fig. 2 An Advertisement Poster for Virginia Saffel Mercer’s Ben-Hur’s Show (author unknown), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington Indiana.

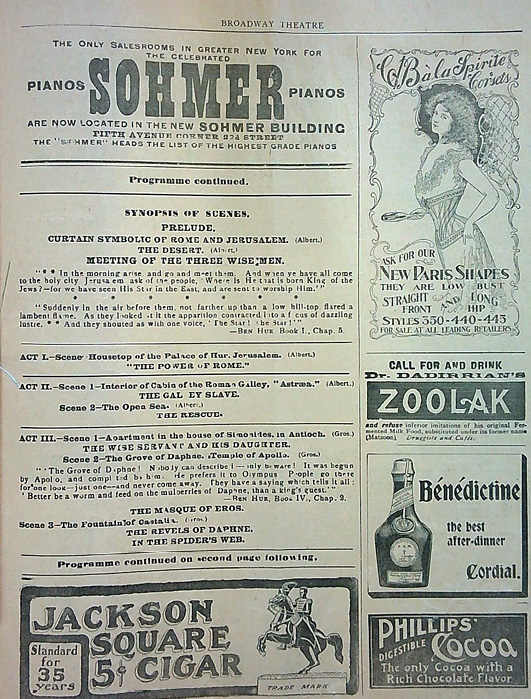

In addition to public readings, there was a plethora of Ben-Hur public lectures and sermons as well as various local dramatizations. In light of the dramatization right created in 1870, a full-scale stage production unambiguously required permission from the copyright owner. Requests for licensing started to flow to Wallace as early as 1882.45 He adamantly refused all such requests, citing as his main ground the fear that a dramatic adaptation would lack the ‘proper spirit of reverence’.46 Even as late as 1898, Wallace wrote one suitor that in his view ‘the subject ought not be put on the stage; that would be a profanation, not of the book but the most sacred of characters to which it must be considered dedicated’.47 The following year, however, Wallace and Harper were engaged in negotiations with Klaw and Erlanger for a grand theater production, with Wallace shrewdly haggling over his royalties.48 When an agreement was finally reached the new licensees promised ‘to endeavor to give America the greatest production it had ever had’.49 The play, which opened on Broadway in November 1899 and ran for twenty-one years, marked a new stage in the commercial exploitation of Ben-Hur derivatives (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3 Ben-Hur Klaw & Erlanger’s Stupendous Production, advertisement Poster (1901), Strobridge Lith. Co., Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014635366/.

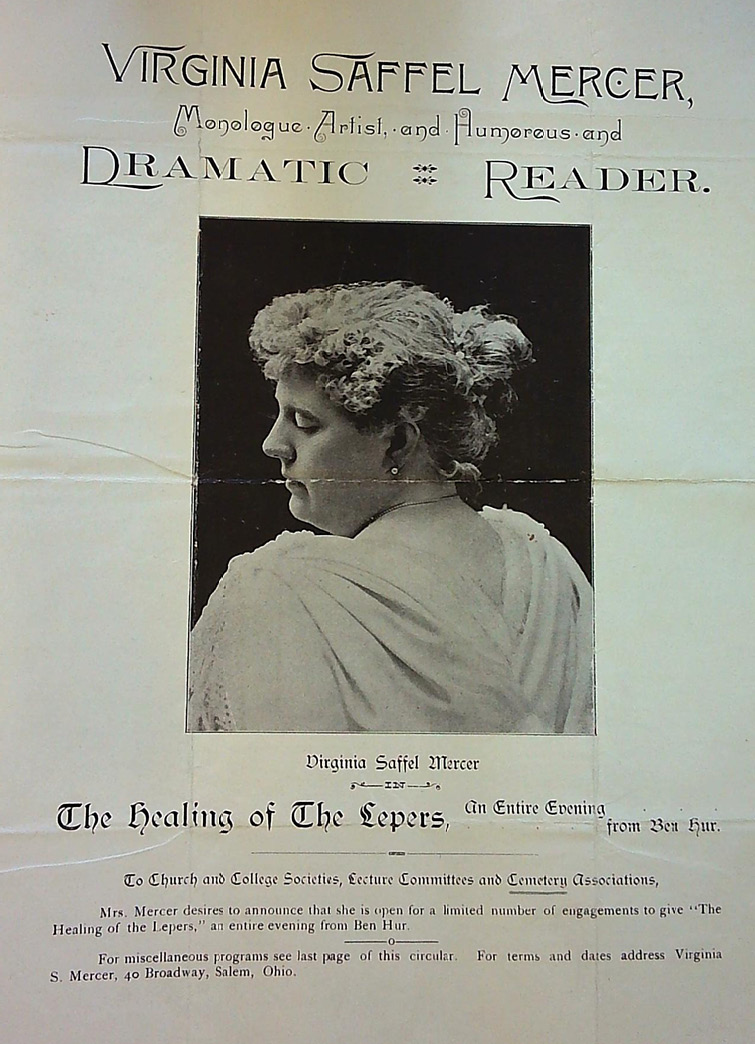

Being a hefty source of royalties, the play also gave rise to many cross-markets synergies. A quick look at one of the many Ben-Hur theatrical programs, in which a list of the characters and scenes is nestled between advertisements for corsets and cigars, demonstrates what a valuable commercial asset the work had become (see Figure 4).

Fig. 4 Ben-Hur’s Play Program (author unknown), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

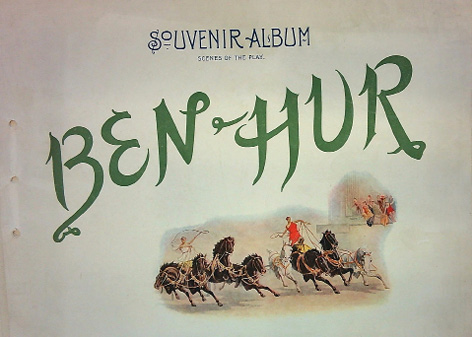

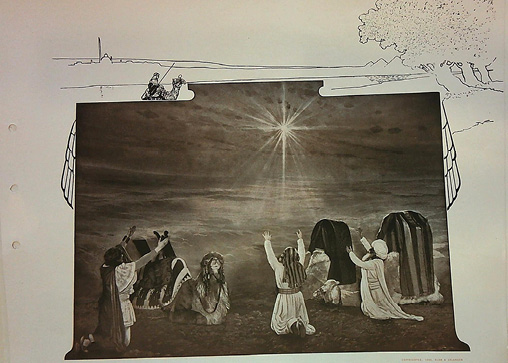

There were also various multimedia products that monetized the combined power of the novel and the play, such as the Ben-Hur Souvenir Album that featured photographs of scenes from the play, short quotations from the novel and matching art work (see Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 5 Ben-Hur Souvenir Album (author unknown), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Fig. 6 Ben-Hur Souvenir Album (author unknown), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

It was with respect to the play that Wallace famously remarked ‘My God, did I set all of this in motion?’50 But the comment had a much broader application.

The Klaw and Erlanger production was not, however, the first extension of the Ben-Hur licensing network beyond print markets. This had already happened earlier, in 1892 with the authorized show Ben Hur in Tableaux and Pantomime.51 Tableaux-vivant, a brand of performance art consisting of portrayal of silent scenes often accompanied by narration, was a highly popular form of entertainment in the nineteenth century. As the name that translates into ‘living pictures’ implies, it is an expressive form halfway between drama and visual arts. Tableaux performances of Ben-Hur started to appear in the mid-1880s and proliferated in the following years.52 Like other Ben-Hur performances, they span a broad spectrum, from social or amateur events to quasi-commercial productions. A conspicuous example of the latter was the tableaux version by Ellen Knight Bradford. It started in 1887 as a charitable event in Washington D.C., but grew more ambitious in nature. Bradford registered with the Copyright Office Selections from Ben Hur Adapted for Readings with Tableaux and toured multiple cities with her successful show, which featured local amateur casts.53 Wallace learned of the Bradford enterprise and attended an Indianapolis performance. He responded with vitriolic remarks but also acknowledged the possibilities for exploiting the novel.54

Wallace also alerted Harper to the possibility of copyright infringement. Harper’s belated response was telling. The legal advice Harper received was that it was unclear whether the unauthorized tableaux infringed copyright. If there was such an infringement it was ‘only as a violation of the right to dramatize the work’.55 One uncertainty related to the fact that the 1870 statutory amendment allowed or perhaps required an author to ‘reserve’ the right of dramatization.56 More fundamentally, it was an open question whether ‘reading from a book and at the same time representing in sight of the audience tableaux composed of figures mentioned and described in the book’ was such a dramatization of the work.57 This was solid legal advice. In a context in which cross-media copyright was not recognized as a general principle, trying to fit the case into the only relevant statutory category was natural. At the same time, the hybrid visual and performative subject matter of tableaux was not a frictionless fit for the category of drama. Given the less-than-ironclad legal case, Harper suggested that making some arrangements ‘by which Mrs. Bradford would acknowledge our rights and take a license from us at even a nominal royalty’ was preferable to an expensive litigation of an uncertain outcome. Despite Harper contacting Bradford’s attorney and her show persisting, there is no indication that such an agreement was ever reached.58

By the time Harper sent this response in late January 1889, Wallace had already agreed to another licensing arrangement of Ben-Hur for tableaux. The origin of this arrangement was a Crawfordsville charitable production endorsed by Wallace, who advised on costumes and scenery.59 This local initiative grew into a full-scale traveling company show officially licensed by Wallace. The contract signed between Wallace and the licensees, later to be known as ‘Clark and Cox’ embodied a calculated and detailed business arrangement.60 Wallace granted a forty-year exclusive license to produce a tableaux based on the novel and undertook to write a libretto for it — all for royalties of five percent of the revenue from charitable shows and six percent from commercial ones, backed by an accounting duty.61 There were also a host of other conditions, including the following: making the license unassignable, the licensees refraining from presenting themselves as agents of Wallace ‘in the business growing out of the rights’, a duty not to exhibit ‘the Lord Jesus Christ as a character or person or make any personal representation of Him in any manner’, and ample opportunities for Wallace to terminate the contract for various causes.62 There was also an auxiliary contract with Harper designed to protect their various print interests in Ben-Hur.63

The Clark and Cox tableaux deal was an important landmark. It extended the commercial exploitation of Ben-Hur derivatives under copyright beyond print markets. It also installed a vigilant licensee with a vested interest in protecting this new market, as was evidenced by the legal warnings that Clark and Cox started issuing before long.64 The turf controlled and protected by the licensee laid on the borderline between performative and visual expression, and thus pictorial uses of the work — at least those that chafed against this market — were now more likely to attract attempts to further extend copyright in this direction. There was also a foreshadowing of the legal tactic that could be used for such an extension: fitting the square peg of an image into the round hole of dramatic copyright.

The Masterpiece of the Nineteenth-Century Illustrated

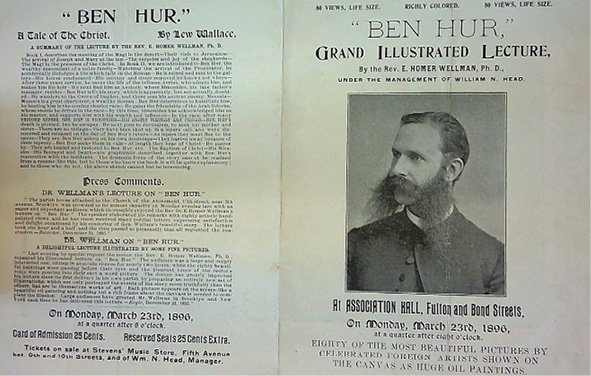

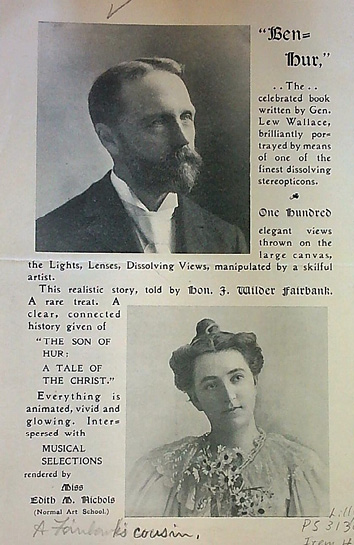

In the mid-1890s, a new market for Ben-Hur derivatives was emerging with the proliferation of magic-lantern slides presentations. The Reverend E. Homer Wellman enticed his potential audience with ‘Eighty of the Most Beautiful Pictures by Celebrated Foreign Artists’ (see Figure 7).65 Another advertisement promised ‘A rare treat’ in the form of ‘The celebrated book written by Gen. Lew Wallace brilliantly portrayed by means of one of the finest dissolving stereopticons’ accompanied by ‘a realistic story’ and ‘MUSICAL SELECTIONS’ with everything ‘animated, vivid and glowing’ (see Figure 8).66

Fig. 7 An Advertisement for a Ben-Hur Magic-Lantern Slides Lecture (1896, author unknown), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Fig. 8 An Advertisement for a Ben-Hur Magic-Lantern Slides (author unknown), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

While these popular magic-lantern presentations varied somewhat, many of them were technologically altered versions of tableaux vivants, combining narration and visual effects, with the images no longer being living ones. This was bound to create friction with the tableaux market, regarded by its licensees as their own.

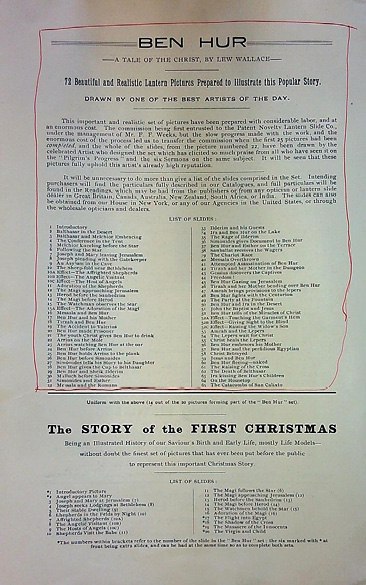

On 11 January 1896, Herbert Riley registered with the Library of Congress ‘The Stereopticon Illustrator of “Ben-Hur”: A Tale of the Christ by General Lew Wallace’.67 It did not take long for a warning blip to appear on Wallace’s radar. On 8 February he wrote to Harper and alerted the company that he had encountered an advertisement flyer for ‘pictures designed to illustrate lectures on Ben Hur’. The enclosed advertisement, he said, should be enough to inform them of the enterprise so they could ‘consider its effect on the book’. ‘For my own part’, he concluded, ‘I cannot avoid a feeling that, while they advertise, they cheapen the work’ (see Figure 10).68

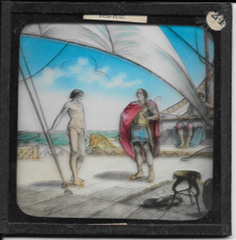

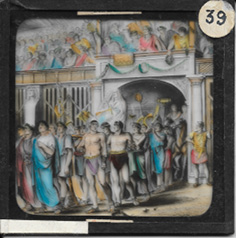

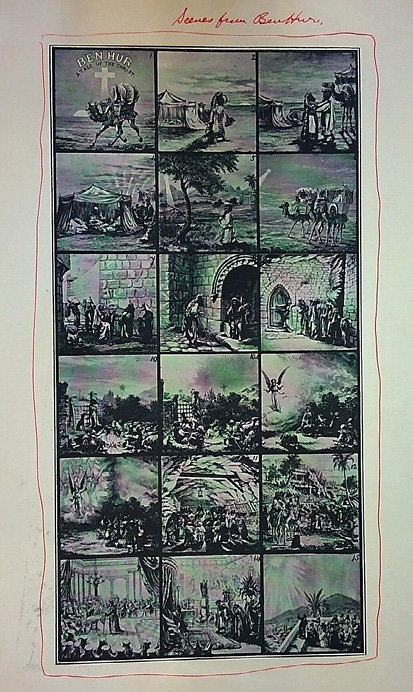

The Riley Brothers, from Bradford, England, had an established magic-lantern business founded in 1884 by Joseph Riley.69 The enterprise had a New York branch run by Joseph’s son, Herbert, who moved there in 1894. Riley, which sometimes claimed to be the ‘Largest Lantern Outfitters in the World,’ had a broad catalog of slides.70 Among its most popular were religious and biblically themed sets. Ben-Hur, already a cultural phenomenon at the time, promised to be a hit, and Riley treated it accordingly. Riley heavily advertised the set, which it heralded as ‘The Masterpiece of the Nineteenth Century Illustrated with Lantern Slides’.71 The seventy-two slides depicted various scenes from the novel. The set was prepared, according to another Riley advertisement, ‘with considerable labor and an enormous cost’.72 The first twenty-five slides were made by the leading slide artist Frank F. Weeks.73 In a promotional published in the Optical Magic Lantern Journal, Weeks was described as having ‘erected studios’ at Leytonstone equipped with a ‘large stock of costumes, models, scenes, etc.’ where he produced the Ben-Hur slides ‘from living Jewish models’.74 Weeks used a unique technique that combined photographing his human models and then heavily reworking the image by painting.75 It may have been this technique that led to ‘the slow progress made with the work, and the enormous cost of the process’, resulting in the transfer of the project to ‘the celebrated Artist’ Nannie Preston and a marked change in style beginning with the twenty-sixth slide (see Figure 9).76

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 9 Frank Weeks and Nannie Preston, Six Slides from Riley Brothers’ Ben-Hur Set (1896), Museum of PRECINEMA — Minici Zotti Collection, Padua, Italy.

Riley sold the slides together with a ‘Reading’, a forty-page text meant to be read as part of the lantern slides presentation. The text devoted a paragraph to each slide and consisted of condensed versions — and sometimes close paraphrases — of Wallace’s own descriptions in the novel. Unsurprisingly, the Ben-Hur slides were a big success. They were sold directly from Riley or through dealers and other companies. If Riley’s promotion is to be believed, they were sold not only in numerous U.S. locations but also in Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India.77 When Walter Clark, Wallace’s licensee, went on a snooping mission he was told by the sellers that ‘the demand is so high they cannot supply it.’78

Fig. 10 An Advertisement for the Riley Brothers’ Ben-Hur Slides, in Lew Wallace’s Papers with the Slide List Marked in Red (author unknown, 1896), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington Indiana.

The Riley Brothers’ prospering enterprise set off loud alarm bells at Wallace’s licensees who identified a potential business threat. Harper referred Wallace’s note to Walter Clark, the licensees of the authorized Ben-Hur tableaux. On 21 March Augustus T. Gurlitz — a seasoned copyright lawyer representing Clark — wrote Wallace a detailed and concerned letter. He reported that ‘Mr. Clark bought a set of the pictures’ and warned that ‘an examination has disclosed an enterprise which will probably destroy the pantomime and tableaux exhibitions of “Ben-Hur”’.79 Riley, he said, is ‘a large concern’; ‘they advertise world-wide’ and ‘sell lantern out-fits to ministers on the installment system in scholastic institutions’.80 Gurlitz enclosed a copy of the text that was circulated together with the slides and suggested that Wallace consider, in consultation with Harper, whether it infringed his book copyright. As for his immediate interest — the ‘dramatic’ rights exploited by his client — he admitted that whether these were infringed by Riley’s actions was ‘not entirely free from doubt’ but expressed his hope that the performance of the slides together with their sale would be found to be such an infringement of dramatic copyright.81 Warning that unless ‘some steps are taken to suppress Riley brothers the country will be overrun with these performances’, he suggested initiating a legal action, half of whose cost would be borne by Clark.82

Whether Wallace was primarily concerned with preventing the ‘cheapening’ of his work or also interested in protecting his profits mattered little. He was now connected to a network of business alliances, and his allies were determined to maximize their profits in the markets they controlled. Clark was the main motivating force. His interest was not in entering the magic-lantern market, and the performances of the Riley Brothers’ slides were, as Gurlitz admitted in his letter, ‘neither tableaux nor pantomimes’. Clark’s concern was that magic-lantern slides might divert demand from the market he commanded, or in Gurlitz’s words: the slide shows ‘interfere with and have a tendency to take the place of tableaux and pantomime performances’.83 The concern was factually plausible in light of the nature of tableaux performances as ‘living pictures’, halfway between drama and still imagery. Clark aimed at protecting a stream of profit in a derivative market and pushing the frontiers of copyright outward was the obvious vehicle of choice for achieving this aim.

Parallel to his correspondence with Gurlitz, Wallace updated Harper, reminded them of their contractual obligation ‘to defend that book against all piracies’ and encouraged them to file a lawsuit against the Riley Brothers.84 It took Gurlitz three more weeks to initiate legal proceedings in Equity against the Riley Brothers on behalf of Wallace, Harper and Clark in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.85

It Is a Very Valuable Property

Gurlitz’s legal strategy was focused and persistent. Its aim was to cast the defendants’ activities as dramatization of the novel. This was perhaps motivated by Clark’s interest in protecting the tableaux market. The main logic of the strategy, however, was the same as that of the legal advice Harper received years earlier with respect to unauthorized tableaux. In the context of copyright jurisprudence that did not recognize a general principle of intermedia infringement, fitting the defendant’s acts within the statutorily-recognized category of dramatization was the most promising route. This was achieved by presenting the entire set of activities comprising the lantern slide show as the equivalent of a dramatic performance of the novel, and portraying the images as merely an element of this integrated whole.

Clark’s affidavit, which used various inflections of the word ‘drama’ dozens of times, was clearly built around this strategy. Clark described the lantern shows as ‘public Dramatic Representation by Tableaux and Recitation of the work’.86 His verbal gymnastics drew on the flexible meaning of ‘tableaux’ when he explained that the work was ‘represented by tableaux thrown upon a screen upon the stage, by means of stereopticon or similar lanterns, and the person giving such Dramatic Representations then recited with such tableaux the portions of the said work “BEN HUR” appropriate to convey to the audience the dramatic situation represented by each tableaux’.87 Based on his snooping mission — that included attending one of the lantern shows in Brooklyn — Clark described the setup of the show in great detail, while studiously referring to the narrator as the ‘reciting performer’ and to the magic-lantern operator as ‘the other performer’. The two-hour show, he said, was ‘a dramatization and dramatic performance of the entire work of “BEN HUR” as invented, composed and written by General Wallace’.88 Describing himself as being ‘familiar with the business of giving dramatic performances of “BEN HUR” throughout the United States’, he warned that ‘unless the defendant is at once enjoined and prevented from further infringing on the rights of the deponent and the other complaints, the damage to his said business will be very large, and almost impossible to calculate’.89

In his affidavit, James Thorne Harper adapted a stunt from the publishing market: he referred and attached President Garfield’s letter of praise for Ben-Hur to Wallace (the same one that was reproduced in the Garfield Edition of the book). His two foci, however, were market effects and a theory of dramatization. As for the former, Harper observed that Ben-Hur is ‘a very valuable property, which, if protected, will give the author ample compensation’.90 He predicted, however, that if lantern shows continue unchecked, profits would be adversely affected both in the book market and from the authorized tableaux. Harper’s argument was that lantern slides ‘of character to give most unsatisfactory impression of the genuine work’ might dissuade the public from attending the tableaux or purchasing the book.91 He also offered an elaborate theory to explain why the lantern shows constituted ‘dramatizations and dramatic representations of the genuine works of General Wallace’.92 The argument was that the defendants ‘copied, imitated, represented and set in order, by means of living models, the portions of “BEN HUR” containing the most striking dramatic situations and events’, and that these live representations were ‘photographed and colored’ and then presented on the screen, accompanied by narration.93 Harper likened the slide projection to the use of the ekkylema in ancient Greek theater where, he also observed, ‘the dramatic effect was evidently produced largely by narration, in which, of course, the voice was the main instrument, especially as cumbersome painted masks were then worn by the actor’.94 According to Harper, dramatization was constituted by the following: dividing the novel into scenes (including the most dramatic events), creating representations of those scenes by live models, photographing the representations, and presenting the images successively on stage in life-sized formats and accompanied by narration. The clever invocations of the special technique of photographing live subjects in creating the slides and of the apparatus, narration and masks used in Greek theater were designed to conceal the main weakness of the dramatization theory: the fact that magic-lantern shows involved no acting by live actors.

The heart of the argument in the Bill of Complaint was twofold. First, the general principle was argued that ‘all property of every kind and nature’ was held by the plaintiffs.95 Here Gurlitz emphasized that the plaintiffs ‘receive a substantial profit and benefit’ from the licensed tableaux, that Clark ‘has a large capital invested’ in the enterprise, and that ‘the said works constitute a most valuable property, and your orators believe that the value of the said property can only be preserved and maintained by preventing any use of said works without the consent and supervision of your orators’.96 This was a version of the new understanding of copyright’s property as protecting the extraction of profit from all possible markets. Since legal doctrine did not yet reflect this principle, however, Gurlitz was astute enough not to stop the argument there, and proceeded to try to squeeze the use into the category of dramatization. On this issue his argument repeated, in cumbersome legalese, the theories developed by Clark and Harper. The effect of the lantern slide projection, he argued,

is to represent upon the stage before the audience in life size, one of such dramatic situations or events, and these devices are arranged and intended to be used, and are used, commencing with the beginning of your orators’ work ‘BEN HUR’ and carried forward in succession in the order in which, and as your orator the said Wallace, has invented and devised his said works, until the whole of his said works has so been represented before the audience.97

In the plea for remedy at the end of the bill it became clear that the dramatization argument was merely a strategy for capturing pictorial representation. In addition to accounting and disgorgement of profits, Gurlitz asked for an injunction — both preliminary and permanent — to restrain the defendants from engaging in a broad range of activities, including ‘importing, manufacturing, advertising, selling, loaning, or otherwise disposing of any outfits or parts of outfits designed for or capable of being used in giving dramatic representations and recitations’ of Ben-Hur and from ‘copying, printing, reprinting, completing or imitating pictorially or otherwise the work’.98 In other words, the dramatization right was being used as a means for prohibiting all derivatives of the text, including in the form of images such as the Riley Brothers’ slides (see Figure 11).

The Rileys and their attorney William O. Campbell offered a different story.99 The snide answer and affidavits — the latter kept referring to Ben-Hur as ‘purporting to have been written by Lewis Wallace’ — made two main arguments. The first was that the Riley slides, perhaps with the exception of the first in the set (proudly presenting the title ‘Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ’), are not illustrations of Ben-Hur at all, but rather ‘original works of art’ depicting ‘scenes in the Orient illustrative of Biblical history and the history of ancient Eastern people’.100 Herbert Riley went as far as asserting in his affidavit that Wallace did not ‘devise and design all of the scenes, events, situations and incidents in the play or story of Ben Hur’ and that if all the elements ‘which have been published for centuries in the Bible, in the Histories of Greece, Rome Palestine, Arabia, Egypt and the Ancients’ were removed from the novel ‘there would remain neither plot nor story’.101 This was a stretch, given not only the title of the slides but also their highly detailed depictions of specific scenes from the novel. The argument precipitated angry refutations from plaintiffs in the form of further affidavits by two literary experts, who testified that Ben-Hur, while drawing on biblical and historical themes, is a highly original and imaginative work.102

Fig. 11 A Reproduction of the Riley Brothers’ Ben-Hur Slides Set as it Appeared in an Advertisement Submitted to the Court (author unknown, 1896), Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

The second defense argument was more plausible. The affidavits by both Joseph and Herbert contained an identical paragraph designed ‘to deny once for all [sic] that the words drama, dramatic or dramatically, dramatize or dramatization are correctly used’ by the plaintiffs. In other words: ‘A Stereoptican illustration is in no sense a drama, and a stereoptican lecture is not a dramatic entertainment’. The passage ends by referring the reader ‘to any and all of the standard dictionaries to the English language extant’.103 In a published letter, the Rileys further explained the definition of drama as ‘a representation made by living actors, etc. and must have living voices and movements, etc.’104 Laying aside the possibility that the slides constituted dramatization, Joseph’s affidavit went on to assert that the production of lantern slides could not infringe copyright because ‘they are neither copies nor imitations of any cut, print, picture, portrait or drawing in said books’.105 This was a restatement of the traditional view: an image can only infringe copyright in another image.

In early September 1896 Judge Emile Henry Lacombe issued a preliminary injunction enjoining the Riley Brothers from selling, advertising or distributing copies of their text.106 Some observers assessed that the injunction ‘will put an end to “Ben Hur” stereopticon lectures’.107 This was a misreading of the situation, since the injunction applied to the text only and not to the lantern slides. When the decision was issued later that month, it became clear that the plaintiffs had suffered a defeat.108 That Riley was enjoined with respect to the text was no surprise. Half a century earlier an infringement by textual condensation of the entire novel might have been a close question, but not in 1896. Moreover, the argument that Riley drew only on general biblical themes rather than the specific expression of the novel Ben-Hur was disingenuous at best. In fact, according to one report, during the lawsuit Riley proposed to withdraw the text.109 With respect to the images, Lacombe was not unsympathetic to the plaintiffs. In a comment that would prove prophetic, he reportedly said that had the issue been a Vitascope presentation ‘he could have understood’ the argument.110 But seeing still images as containing the same expressive content as a text was too much for him. He rejected the premise that no one ‘might produce and sell copies of drawings, the motif of which was suggested in the book’, deeming it something that no one would contend.111 The Riley Brothers were free to go on distributing their slides, which they apparently did.112

The borderline separating text and image was not crossed in Wallace v. Riley. Learned treatise writers developed a new legal theory of copyright’s property right as extending to every expressive form and market. Ben-Hur introduced a new economic model of exploiting a successful novel through licensing in multiple media markets, and produced the pressure for extending copyright to capture the exchange value of these derivatives. A clever legal strategy that attempted to squeeze images into the recognized category of dramatization had been devised, and various matching theories of dramatization had been woven. But the courts, still held back by remnants of the traditional understanding of copyright, refused to see images as copies of texts. For a time.

Aftermath: Harper v. Kalem and the Logic of Derivative Works

Images soon came back to haunt American copyright law, this time as moving images. And Ben-Hur was again in the thick of it. In 1907 the Kalem Company released a motion picture it advertised as ‘A Roman Spectacle Pictures adapted from Gen. Lew Wallace’s Famous Book Ben Hur’.113 What followed was a reenactment of the Riley Brothers’ slides events, only with higher stakes. The main interested party was now Klaw and Erlanger, the licensee and producer of the Ben-Hur grand theatrical production. Regarding the motion picture as a threat to its market, it rapidly filed a lawsuit together with Harper and Henry Wallace who following the death of his father took over the management of the commercial empire that Ben-Hur had become.114 The motion picture itself, while being one of the first to have a written script, was nevertheless still a close cousin of the tableaux-vivant and magic-lantern shows. It consisted of a visual presentation of several scenes out of the novel connected by short textual intertitles. This was a pictorial spectacle, literally a ‘motion picture’ in the original sense of a sequence of images with the added incident of movement.115 Thus, in light of Wallace v. Riley and traditional copyright principles, Kalem had reasons to be cautiously optimistic.

Presiding over the trial in the Southern District of New York was none other than Jude Emile Henry Lacomb. Making good on his comment eleven years earlier, he ruled in a cryptic opinion that the movie infringed the copyright in the novel and issued a broad injunction including a prohibition on Kalem to produce, play, exhibit, copy or advertise the dramatic composition ‘Ben Hur’ or ‘any of its characters, scenes, incidents, plot or story’.116 Kalem appealed the decision to the U.S. Circuit Court for the Second Circuit and then, after another loss, to the U.S. Supreme Court where it suffered a final defeat. The legal strategies of the opposing parties closely followed those employed in the Riley Brothers litigation. Kalem’s lawyers argued that text and image were two different forms of expression and that one could not infringe copyright in the other. Their Supreme Court brief contained a long section entitled ‘Book and Picture Are Essentially Different’, that led to the conclusion that an image could not be a ‘copy’ of a copyrighted text.117 The plaintiffs’ lawyers, for their part, used the exact same strategy introduced in Wallace v. Riley: bringing the images within the scope of copyright in texts through the category of dramatization. Their Supreme Court brief argued that ‘What the Kalem Company did was to dramatize “Ben Hur”’.118

Ruling in favor of plaintiffs, both the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court found that the exhibitors of the motion picture were copyright infringers and that Kalem was contributorily liable by facilitating their actions.119 Indeed, today Kalem is often cited as a precedent with respect to secondary liability.120 Modern lawyers usually find this reasoning puzzling or even backwards: surely, by adapting Ben-Hur into a motion picture, Kalem was the primary infringer whose infringement facilitated the further activities of the exhibitors? This anachronistic puzzle fails to understand the reasoning of the decisions and the extent to which recognizing moving images as an infringement of a book copyright was a revolutionary and challenging step for the judges who took it. On neither of the appeals did a court rule that the motion picture adaptation was dramatization or copyright infringement. In fact, the Court of Appeals explicitly ruled that it was not. ‘The series of photographs taken by the defendant constitutes a single picture, capable of copyright as such’, Circuit Judge Ward wrote, ‘and as pictures only represent the artist’s idea of what the author has expressed in words […] they do not infringe a copyrighted book or drama, and should not as a photograph be enjoined’.121 In other words, on this point the court agreed with the defendant: an image is neither a copy nor dramatization of a text. Dramatization does occur, however, ‘[w]hen the film is put on an exhibiting machine, which reproduces the action of the actors and animals’.122 The Supreme Court opinion written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. further elaborated this reasoning:

[D]rama may be achieved by action as well as by speech. Action can tell a story, display all the most vivid relations between men, and depict every kind of human emotion, without the aid of a word […] But if a pantomime of Ben Hur would be a dramatizing of Ben Hur, it would be none the less so that it was exhibited to the audience by reflection from a glass and not by direct vision of the figures — as sometimes has been done in order to produce ghostly or inexplicable effects. The essence of the matter in the case last supposed is not the mechanism employed but that we see the event or story lived.123

Since it was only the exhibition of the film rather than the pictorial adaptation by its maker that constituted dramatization and copyright infringement, the courts had to resort to the secondary liability construct.

This reasoning was complex and cumbersome. Moreover, as critics were quick to point out, the theory that exhibition of a motion picture constituted dramatization under the 1870 statute was highly dubious.124 Laying aside the technical legal maneuvers, when understood in context, what happened in Kalem is clear: the judges had already internalized copyright’s new ideology as broad control over exchange value in all secondary markets. Yet, still constrained by the old doctrines and categories, they did not feel free to simply rule that a motion-picture adaptation was an infringing reproduction of a text. Instead they relied on the dramatization strategy first introduced in Wallace v. Riley, and the secondary liability construct. Notwithstanding these remnants of traditional copyright thinking, the Kalem courts did cross the text-image Rubicon. Within a few years, the idea that a motion-picture adaptation is an infringement of a novel’s copyright was normalized. Future courts simply proceeded on the basis of that assumption and let the dramatization and contributory liability crutches drop.125 Today, modern copyright lawyers are likely to find the idea that a motion-picture adaptation is not infringement of a copyright in a book alien. And while modern text-to-still-images cases are hard to find, if you asked an American copyright lawyer, her answer is likely to be that images that embody enough concrete and detailed expression derived from a copyrighted text are infringing.

Recognizing text-to-image copyright infringement had broader implications. The Supreme Court’s step in Kalem marked the beginning of the acceptance of the logic of derivative works: the deeply-seated assumption that copyright’s property stretches across media and fields of expression as a means for allowing the owner to internalize profits from all available markets. American copyright law thus shifted from physicalism to meta-physicalism. In its early days, copyright’s limited scope, traceable to its origin as a publisher’s privilege, was embodied in the legal concept of the copy. The copy functioned as a quasi-physicalist object, somewhere between the physical book and the intangible work.126 Understood as encompassing the specific language used by the author, it seemed to supply clear boundaries to the property right, objectively dictated by natural facts. By the dawn of the twentieth century the increased commodification of expressive works, epitomized by Ben-Hur, reshaped copyright. It came to be reflected in a new concept of the work as transcending specific expressive forms and spanning all possible markets. These metaphysics of derivative works-cum-markets would make the new logic of copyright seem as inevitable and natural as that of the copy.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

i. Archival Material

Kalem Company v. Harper Bros. Transcript of Record.

Lew Wallace (1827–1905) Miscellaneous Uncataloged Materials, at Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington.

Lew Wallace collection 1799–1972, Indiana Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

Stowe v. Thomas Case File, National Archives and Records Administration.

Wallace Mss. II, Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington.

Wallace v. Riley Case File, National Archives and Records Administration.

ii. Legislation

1790 Copyright Act (Act of May 31, 1790), ch. 15, 1 Stat. 124.

1802 Copyright Act (Act of Apr. 29, 1802), ch. 36, 2 Stat. 171.

1856 Copyright Act Amendment (Act of Aug. 18, 1856), 11 Stat. 138.

1865 Copyright Act (Act of Mar. 3, 1865), 13 Stat. 540,

1870 Copyright Act (Act of July 8, 1870), ch. 230, 16 Stat. 198.

1897 Copyright Act Amendment (Act of Mar. 3, 1897), ch. 392, 29 Stat. 694

Statute of Anne 1710 (8 Anne c. 19).

Engravers’ Copyright Act 1735 (8 Geo. II c.13).

iii. Cases

Gyles v. Wilcox (1740) 26 Eng. Rep. 489.

Folsom v. Marsh, 9 F. Cas. 342, 344 (C.C.D. Mass. 1841).

Harper & Bros. v. Kalem Co., 169 F. 61 (2d Cir. N.Y. 1909).

Kalem Co. v. Harper Bros., 222 U.S. 55 (1911).

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005).

Millar v. Taylor (1769) 95 Eng. Rep. 201.

Story v. Holocombe, 23 F. Cas. 171 (C.C.D.Oh. 1847).

Stowe v. Thomas, 23 F. Cas. 201 (C.C.E.D.Pa. 1853).

Secondary Sources

Bracha, Oren, ‘Commentary on Stowe v. Thomas (1853)’, in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer (2008), http://www.copyrighthistory.org/commentary/us_1853b.

——, ‘Commentary on the U.S. Copyright Act Amendment 1856’, in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer (2008), http://www.copyrighthistory.org/commentary/us_1856.

——, ‘How Did Film Become Property? Copyright and the Early American Film Industry’, in Copyright and the Challenge of the New, ed. by Brad Sherman and Leanne Wiseman (New York: Wolters Kluwer Law & Business, 2012) pp. 141–177.

——, Owning Ideas: The Intellectual Origins of American Intellectual Property, 1709–1909 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1017/9780511843235.

Curtis, George Ticknor, A Treatise on the Law of Copyright (Boston: C. C. Little and J. Brown, 1847).

Deazley, Ronan, ‘The Statute of Anne and the Great Abridgment Swindle’, Houston Law Review, 47 (2010), 793–818.

Decherney, Peter, Hollywood’s Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet (New-York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

Drone, Eaton S., A Treatise on the Law of Property in Intellectual Productions in Great Britain and the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, 1879).

Gordon, Colin, By Gaslight in Winter: A Victorian Family History through the Magic Lantern (London: Elm Tree Books, 1980).

Henry, David, ‘Ben-Hur: Francis Fredric Theophilus Weeks and Patent No. 8615 of 1894’, The New Magic Lantern Journal, 5 (1987), 2–5.

Homestead, Melissa J., ‘“When I can Read my Title Clear”: Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Stowe v. Thomas Copyright Infringement Case’, Prospects, 27 (2002), 201–245, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0361233300001198.

Hunter, David, ‘Copyright Protection for Engravings and Maps in Eighteenth Centaury Britain’, The Library, 6th Ser., 9 (1987), 128–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/library/s6-IX.2.128.

Miller, Derek, Copyright and the Value of Performance, 1770–1911 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349284.

Miller, Howard, ‘The charioteer and the Christ: Ben-Hur in America from the Gilded Age to the Culture Wars’, Indiana Magazine of History, 104 (2008), 153–175.

Morsberger, Robert E. and Morsberger, Katherine M., Lew Wallace: Militant Romantic (New York: McGraw-Hill 1980).

Pon, Lisa, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004).

Rose, Mark, ‘The Author in Court: Pope v. Curll (1741)’, Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal, 10 (1992), 475–493.

Ryan, Barbara, Chronicling Ben-Hur’s Climb, 1880–1924 (London and New York: Routledge 2019), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315572000.

Sag, Mathew, ‘The Prehistory of Fair Use’, Brooklyn Law Review, 76 (2011), 1371–1412.

Solomon, Jon, Ben-Hur: The Original Blockbuster (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

Swansburg, John, ‘The Passion of Lew Wallace: The Incredible Story of How a Disgraced Civil War General Became One of the Best-Selling Novelists in American history’, Slate, 26 March 2013, http://www.slate.com/articles/life/history/2013/03/ben_hur_and_lew_wallace_how_the_scapegoat_of_shiloh_became_one_of_the_best.html.

Theisen, Lee Scott, ‘“My God, Did I set all of this in Motion?” General Lew Wallace and Ben‐Hur’, Journal of Popular Culture, 18 (1984), 33–41.

1 Folsom v. Marsh, 9 F. Cas. 342, 344 (C.C.D. Mass. 1841).

2 The case was not reported. The discussion here is based on the case’s record and press reports.

3 Statute of Anne 1710 (8 Anne c. 19); 1790 Copyright Act (Act of May 31, 1790), ch. 15, 1 Stat. 124.

4 For examples of early printing privileges in prints see David Hunter, ‘Copyright Protection for Engravings and Maps in Eighteenth Centaury Britain’, The Library, 6th Ser., 9 (1987), 128–147 (p. 146), https://doi.org/10.1093/library/s6-IX.2.128; For a discussion of continental printing privileges in prints see Lisa Pon, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004). The Statute of Anne covered ‘Book or Books’ (8 Ann., c. 19, § 1). The American 1790 Act covered ‘map, chart, book or books’ (1 Stat. 124 § 2). Obviously, the latter already extended copyright beyond texts and into the realm of the printed image with its inclusion of maps and charts.

5 Engravers’ Copyright Act 1735 (8 Geo. II, c.13); 1802 Copyright Act (Act of Apr. 29, 1802), ch. 36, 2 Stat. 171, § 2.

6 John Bouvier, Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, 2 vols. (Boston: Boston Book Co., 1897), I, 436.

7 In the American context see 1865 Copyright Act (Act of Mar. 3, 1865), 13 Stat. 540, §1 (adding photographs); 1870 Copyright Act (Act of July 8, 1870), ch. 230, 16 Stat. 198, § 86 (adding ‘painting, drawing, chromo, statue’ and other subject matter).

8 See e.g. the entry for ‘Copy-right’ in William Nicholson, American Edition of The British Encyclopedia: Or, Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, Comprising An Accurate and Popular View of the Present Improved State of Human Knowledge, 12 vols. (Philadelphia: Mitchell, Ames and White, 1819), IV.; Oren Bracha, Owning Ideas: The Intellectual Origins of American Intellectual Property, 1709–1909 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), pp. 147–148, https://doi.org/10.1017/9780511843235.

9 See Gyles v. Wilcox (1740) 26 Eng. Rep. 489; Millar v. Taylor (1769) 95 Eng. Rep. 201, 205. In the American context see Story v. Holocombe, 23 F. Cas. 171 (C.C.D.Oh. 1847); Stowe v. Thomas, 23 F. Cas. 201 (C.C.E.D.Pa. 1853).

10 See Ronan Deazley, ‘The Statute of Anne and the Great Abridgment Swindle’, Houston Law Review, 47 (2010), 793–818; Mathew Sag, ‘The Prehistory of Fair Use’, Brooklyn Law Review 76 (2011), 1371–1412.

11 Stowe v. Thomas, 23 F. Cas. 201 (C.C.E.D.Pa. 1853).

12 See Melissa J. Homestead, ‘”When I can Read my Title Clear”: Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Stowe v. Thomas Copyright Infringement Case’, Prospects, 27 (2002), 201–45; Oren Bracha, ‘Commentary on Stowe v. Thomas (1853)’, in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer (2008), http://www.copyrighthistory.org/commentary/us_1853b.

13 National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Stowe v. Thomas Case File, Complainant’s Bill; Stowe v. Thomas Case File, Affidavit of Harriet Beecher Stowe.

14 ‘“Uncle Tom” at Law’, New York Weekly Tribune, 16 April 1853, p. 10.

15 Stowe, 23 F. Cas. at 205.

16 Id. at 207.

17 Eaton S. Drone, A Treatise on the Law of Property in Intellectual Productions in Great Britain and the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, 1879), pp. 454–455; James O Pierce, ’Anomalies in the Law of Copyright’, Southern Law Review, 5 (1879), 420–36 (pp. 433–434).

18 1870 Copyright Act, § 86.

19 Bracha, Owning Ideas, p. 158.

20 1856 Copyright Act Amendment (Act of August 18, 1856), 11 Stat. 138, 139, §1.

21 See Oren Bracha, ‘Commentary on the U.S. Copyright Act Amendment 1856’, in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), ed. by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer (2008), http://www.copyrighthistory.org/commentary/us_1856.

22 See Derek Miller, Copyright and the Value of Performance, 1770–1911 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 122–74, https://doi.org/10.1017/978110834 9284.

23 1897 Copyright Act Amendment (Act of Mar. 3, 1897), ch. 392, 29 Stat. 694.

24 George Ticknor Curtis, A Treatise on the Law of Copyright (Boston: C. C. Little and J. Brown 1847), pp. 237–238.

25 Ibid., p. 278.

26 Ibid., p. 279.

27 Ibid., p. 293.

28 Drone, A Treatise on the Law of Property in Intellectual Productions, p. 385.

29 Ibid., p. 451.

30 Bracha, Owning Ideas, pp. 148–149; Drone, A Treatise on the Law of Property in Intellectual Productions, p. 451.

31 Ibid., p. 464.

32 Jon Solomon, Ben Hur: The Original Blockbuster (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), p. 14.

33 See Robert E. Morsberger and Katharine M. Morsberger, Lew Wallace: Militant Romantic (New York: McGraw-Hill 1980), pp. 309–331.

34 See Solomon, Ben Hur, pp. 188–217; Howard Miller, ‘The charioteer and the Christ: Ben Hur in America from the Gilded Age to the Culture Wars’, Indiana Magazine of History, 104 (2008), 153–75; Barbara Ryan, Chronicling Ben-Hur’s Climb, 1880–1924 (London and New York: Routledge, 2019); John Swansburg, ‘The Passion of Lew Wallace: The Incredible Story of How a Disgraced Civil War General Became One of the Best-Selling Novelists in American history’, Slate, 26 March 2013, http://www.slate.com/articles/life/history/2013/03/ben_hur_and_lew_wallace_how_the_scapegoat_of_shiloh_became_one_of_the_best.html.

35 Solomon, Ben Hur, pp. 149–151; Ibid., p. 5; Ibid., p. 13; Ibid., pp. 141–142.

36 Ibid., pp. 151–156.

37 Ibid., pp. 174–180.

38 Ibid., pp. 408–490.

39 Ibid., pp. 410–412.

40 Ibid., pp. 412–423.

41 Ibid., pp. 488–489.

42 Advertisement Pamphlet, in Lew Wallace (1827–1905) Miscellaneous Uncataloged Materials, Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington (hereinafter ‘Wallace Miscellaneous’).

43 Letter from Virginia Mercer to Lew Wallace, 20 December 1896, in Wallace Mss. II, Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington (hereinafter ‘Wallace Mss. II’).

44 Letter from Susan Wallace to Harper & Bros., 26 December 1896, Wallace Mss. II.

45 Morsberger and Morsberger, Lew Wallace, pp. 453–454.

46 Ibid.

47 Letter from Lew Wallace to W.W. Allen, 15 November 1898, Wallace Mss. II.

48 Solomon, Ben Hur, p. 315.

49 Letter from Klaw & Erlanger to Lew Wallace, 25 May 1899, Wallace Mss. II.

50 Lee Scott Theisen, ‘“My God, Did I set all of this in Motion?” General Lew Wallace and Ben‐Hur’, Journal of Popular Culture, 18 (1984), 33–41 (p. 38).

51 This was the title of the libretto that Wallace wrote for the show which went under different names.

52 Solomon, Ben Hur, pp. 220–231.

53 Ibid., pp. 220–226.

54 Ibid., pp. 226–227.

55 Harper & Bros. to Lew Wallace, 29 January 1889, Wallace Mss. II.

56 1870 Copyright Act, § 86.

57 Harper & Bros. to Lew Wallace, 29 January 1889, Wallace Mss. II.

58 Indeed, Harper estimated that in the absence of a license Bradford would take the risk and continue her shows. Ibid.

59 Solomon, Ben Hur, pp. 235–237.

60 The original licensees were David W. Cox, William S. Brown and Albert S. Miller. Walter Clark joined in later but ended up buying up a full share of the enterprise in 1894.

61 Harper was able to propose granting a tableaux license to Bradford despite the exclusivity of the license to Cox and Clark because the latter agreement contained an exception that reserved for Wallace the right to authorize or prevent shows by churches and congregations in their own towns. This meant that Bradford’s license would have had to be limited to such local, church-affiliated performances.

62 Wallace Mss. II.

63 Ibid.

64 Solomon, Ben Hur, p. 239.

65 Advertisement Pamphlet, Wallace Miscellaneous.

66 Advertisement Pamphlet, Wallace Miscellaneous.

67 Certificate of deposit of 11 January 1896, Wallace Mss. II. Riley deposited a copy of the work as a ‘Book’. He was, however, probably trying to obtain copyright protection for the slides. The subtitle of the work was ‘72 Lantern Pictures by Eminent Artists’ and the deposit was of a pamphlet that included a small version of all the images on two pages. The most plausible explanation is that Riley was trying to copyright all 72 slides — but register, deposit, and pay fees only once.

68 Letter from Lew Wallace to Harper Bros., 8 February 1896, Lew Wallace Collection 1799–1972, Indiana Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

69 See Colin Gordon, By Gaslight in Winter: A Victorian Family History through the Magic Lantern (London: Elm Tree Books, 1980).

70 This was an occasional boast in the Riley Brothers advertisements. See e.g. Dominion Medical Monthly and Ontario Medical Journal, 6 (January-June 1896), 471.

71 Advertisement pamphlet, Wallace Miscellaneous.

72 Advertisement pamphlet, Wallace Miscellaneous.

73 See David Henry, ‘Ben-Hur: Francis Fredric Theophilus Weeks and Patent No. 8615 of 1894’, The New Magic Lantern Journal, 5 (1987), 2–5.

74 ‘Photique Art’, The Optical Magic Lantern Journal and Photographic Enlarger, 7 (1896), 175.

75 Henry, ‘Ben-Hur’, p. 3.

76 Cincinnati Enquirer, 27 April 1896, p. 9.

77 Advertisement pamphlet. Wallace Miscellaneous.

78 Letter from Augustus Gurlitz to Lew Wallace, 21 March 1896, Wallace Mss. II.

79 Ibid.

80 Ibid.

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid.

83 Ibid.

84 Letter from Lew Wallace to Harper Bros., 21 March 1896, Wallace Mss. II.

85 NARA, Wallace v. Riley Case File (hereinafter ‘Wallace v. Riley’).

86 Affidavit of Walter C. Clark, Wallace v. Riley, p. 2.

87 Ibid., p.3.

88 Ibid., p. 8.

89 Ibid., pp. 10–11.

90 Affidavit of James Thorne Harper, Wallace v. Riley, p. 1.

91 Ibid., p. 2.

92 Ibid., p. 5.

93 Ibid., p. 3.

94 Ibid., pp. 4–5.

95 Bill of Complaint, Wallace v. Riley, p. 10.

96 Ibid., p. 11.

97 Ibid., p. 12.

98 Ibid., pp. 16–17.

99 This is the attorney of record in the court’s documents. The Rileys later referred to ‘Mr. Wilber’ as their attorney. See ‘Letter to the Editor’ from Riley Brothers, The Optical Magic Lantern Journal and Photographic Enlarger, 7 (1896), 135–136 (p. 136).

100 Answer, Wallace v. Riley, p. 1.

101 Ibid., p. 2.

102 Affidavit of Charlton T. Lewis and Affidavit of Laurence Hutton, Wallace v. Riley.

103 Affidavit of Herbert Jowett Riley, Wallace v. Riley, p. 1. Affidavit of Joseph Riley, Wallace v. Riley, p. 1.

104 Letter to the Editor from Riley Brothers, The Optical Magic Lantern Journal and Photographic Enlarger, 7 (1896), 135–136 (p. 136).

105 Affidavit of Joseph Riley, Wallace v. Riley, p. 4.

106 ‘A “Ben Hur” Injunction’, The New York Times, 3 September 1896, p. 9.

107 Ibid., p. 12.

108 The last document in the case file is a decision by Judge Lacombe whose transcript is truncated. It appears that this was the written decision of the motion for a preliminary injunction. There is no indication that the case ever advanced beyond this stage, either in the trial court or as an appeal. See Order for Preliminary Injunction, Wallace v. Riley.

109 ‘Wallace and Others v. Riley Brothers, New York’, The Optical Magic Lantern Journal and Photographic Enlarger, 7 (1896), 166. See also ‘Wallace and Others v. Riley Bros.’, Photography, September 24, 1896, p. 632; ‘Infringement of Copyright’, The Photographic News, 25 September 1896, p. 618; ‘Illustrative Slides’, The American Amateur Photographer, 8 (1896), 483–484.

110 Letter to the Editor from Riley Brothers, The Optical Magic Lantern Journal and Photographic Enlarger, 7 (1896), 135, p. 136.

111 ‘Wallace and Others v. Riley Brothers, New York’, p. 167.

112 Solomon, Ben-Hur, p. 525.

113 The Billboard, 7 December 1907, p. 100.

114 See Oren Bracha, ‘How Did Film Become Property? Copyright and the Early American Film Industry’, in Copyright and the Challenge of the New, ed. by Brad Sherman and Leanne Wiseman (New York: Wolters Kluwer Law & Business, 2012), pp. 141–77; Peter Decherney, Hollywood’s Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet (New-York: Columbia University Press, 2012), pp. 45–54; Solomon, Ben-Hur, pp. 543–552.

115 See Bracha, ‘How Did Film Become Property?’, p. 171.

116 Permanent Injunction Decision, Kalem Company v. Harper Bros, Transcript of Record, p. 24 (hereinafter ‘Kalem v. Harper Bros’).

117 Brief for Appellant. Kalem v. Harper Bros., p. 12.

118 Brief for Appellees. Kalem v. Harper Bros., p. 28.

119 Kalem Co. v. Harper Bros., 222 U.S. 55 (1911); Harper & Bros. v. Kalem Co., 169 F. 61 (2d Cir. N.Y. 1909).

120 See e.g. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913, 935 (2005).

121 Kalem, 169 F. at 63.

122 Ibid.

123 Kalem, 222 U.S. at 61–62.

124 See e.g. ‘Copyright — Moving Pictures as Dramatization’, Central. Law. Journal, 73 (1911), 442–443.

125 Bracha, Owning Ideas, 186–187. For a discussion of the effect of the new regal framework on the film industry see Decherney, Hollywood’s Copyright Wars, pp. 54–57.

126 Bracha, Owning Ideas, pp. 143–145. See also Mark Rose, ‘The Author in Court: Pope v. Curll (1741)’, Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal, 10 (1992), 475–493 (p. 492).